North Carolina Eugenics Board on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Eugenics Board of North Carolina (EBNC) was a State Board of the state of

At the time of the Board's formation there was a body of thought that viewed the practice of eugenics as both necessary for the public good and for the private citizen. Following ''Buck v. Bell'', the Supreme Court was often cited both domestically and internationally as a foundation for eugenics policies.

In ''Buck v. Bell'' Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, in support of eugenics policy, that

Despite the Supreme Court rulings in support of eugenics as constitutionally permitted, even as late as 1950 some physicians in North Carolina were still concerned about the legality of sterilization. Efforts were made to reassure the medical community that the laws were both constitutionally sound and specifically exempting physicians from liability.

At the time of the Board's formation there was a body of thought that viewed the practice of eugenics as both necessary for the public good and for the private citizen. Following ''Buck v. Bell'', the Supreme Court was often cited both domestically and internationally as a foundation for eugenics policies.

In ''Buck v. Bell'' Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, in support of eugenics policy, that

Despite the Supreme Court rulings in support of eugenics as constitutionally permitted, even as late as 1950 some physicians in North Carolina were still concerned about the legality of sterilization. Efforts were made to reassure the medical community that the laws were both constitutionally sound and specifically exempting physicians from liability.

While it is not known exactly how many people were sterilized during the lifetime of the law, the Task Force established by Governor Beverly Perdue estimated the total at around 7,500. They provided a summary of the estimated number of operations broken down by time period. This does not include sterilizations that may have occurred at a local level by doctors and hospitals.

The report went on to provide a breakdown by county. There were no counties in North Carolina that performed no operations, though the spread was marked, going from as few as 4 in Tyrrell county, to 485 in

While it is not known exactly how many people were sterilized during the lifetime of the law, the Task Force established by Governor Beverly Perdue estimated the total at around 7,500. They provided a summary of the estimated number of operations broken down by time period. This does not include sterilizations that may have occurred at a local level by doctors and hospitals.

The report went on to provide a breakdown by county. There were no counties in North Carolina that performed no operations, though the spread was marked, going from as few as 4 in Tyrrell county, to 485 in

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

formed in July 1933 by the North Carolina State Legislature

The North Carolina General Assembly is the bicameral legislature of the State government of North Carolina. The legislature consists of two chambers: the Senate and the House of Representatives. The General Assembly meets in the North Carolina ...

by the passage of House Bill 1013, entitled "An Act to Amend Chapter 34 of the Public Laws of 1929 of North Carolina Relating to the Sterilization of Persons Mentally Defective". This Bill formally repealed a 1929 law, which had been ruled as unconstitutional by the North Carolina Supreme Court earlier in the year.

Over time, the Board shifted their focus to include sterilizations. Their original purpose was to oversee the practice of sterilization as it pertained to inmates or patients of public-funded institutions that were judged to be 'mentally defective or feeble-minded' by authorities. The majority of these sterilizations were coerced. Academic sources have observed that this was not only an ableist and classist project but also a racist one, as Blacks were disproportionately targeted. Of the 7,686 people who were sterilized in North Carolina after 1933, 5,000 were Black. American Civil Liberties Union attorney Brenda Feign Fasteau said of the situation, "As far as I can determine, the statistics reveal that since 1964, approximately 65 percent of the women sterilized in North Carolina were Black and approximately 35 percent were White."

In contrast to other eugenics programs across the United States, the North Carolina Board enabled county departments of public welfare to petition for the sterilization of their clients. The Board remained in operation until 1977. During its existence thousands of individuals were sterilized. In 1977 the N.C. General Assembly repealed the laws authorizing its existence, though it would not be until 2003 that the involuntary sterilization laws that underpinned the Board's operations were repealed.

Today the Board's work is repudiated by people across the political, scientific and private spectrum. In 2013, North Carolina passed legislation to compensate those sterilized under the Board's jurisdiction.

Structure

The board was made up of five members: * The Commissioner of Public Welfare of North Carolina. * The Secretary of the State Board of Health of North Carolina. * The Chief Medical Officer of "An institute for the feebleminded or insane" of the State of North Carolina not located in Raleigh. * The Chief Medical Officer of the State Hospital at Raleigh. * The Attorney General of the State of North Carolina.History of the Board

1919

The State of North Carolina first enacted sterilization legislation in 1919. The 1919 law was the first foray for North Carolina into eugenics; this law, entitled "An Act to Benefit the Moral, Mental, or Physical Conditions of Inmates of Penal and Charitable Institutions" was quite brief, encompassing only four sections. Provision was made for creation of a Board of Consultation, made up of a member of the medical staff of any of the penal or charitable State institutions, and a representative of the State Board of Health, to oversee sterilization that was to be undertaken when "in the judgement of the board hereby created, said operation would be for the improvement of the mental, moral or physical conditions of any inmate of any of the said institutions". The Board of Consultation would have reported to both the Governor and the Secretary of the State Board of Health. No sterilizations were performed under the provisions of this law, though its structure was to guide following legislation.1929

In 1929, two years after the landmark US Supreme Court ruling of ''Buck v. Bell

''Buck v. Bell'', 274 U.S. 200 (1927), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., in which the Court ruled that a state statute permitting compulsory sterilization of the unfit, including th ...

'' in which sterilization was ruled permissible under the U.S. Constitution, North Carolina passed an updated law that formally laid down rules for the sterilization of citizens. This law, entitled "An Act to Provide For the Sterilization of the Mentally Defective and Feeble-Minded Inmates of Charitable and Penal Institutions of the State of North Carolina", was similar to the law which preceded it, although this new Act contained several new provisions.

In contrast to the 1919 law, which had mandated sterilization for the "improvement of the mental, moral or physical condition of any inmate", the new law added a new and far-reaching condition: "Or for the public good." This condition, expanding beyond the individual to greater considerations of society, would be built on in the ensuing years.

The 1929 law also expanded the review process to four reviewers, namely: The Commissioner of Charities and Public Welfare of North Carolina, The Secretary of the State Board of Health of North Carolina, and the Chief Medical Officers of any two institutions for the "feeble-minded or insane" for the State of North Carolina.

Lastly, the new law also explicitly stated that sterilization, where performed under the Act's guidelines, would be lawful and that any persons who requested, authorized or directed proceedings would not be held criminally or civilly liable for actions taken. Under the 1929 law, 49 recorded cases took place in which sterilization was performed.

1933–1971

In 1933, the North Carolina State Supreme Court heard ''Brewer v. Valk'', an appeal from Forsyth County Superior Court, in which the Supreme Court upheld that the 1929 law violated both the U.S. Constitution's 14th Amendment and Article 1, Section 17 of the 1868 North Carolina State Constitution. The Supreme Court noted that property rights required due process, specifically a mechanism by which notice of action could be given, and hearing rights established so that somebody subject to the sterilization law had the opportunity to appeal their case. Under both the U.S. Constitution and the N.C. State Constitution in place at the time, the Supreme Court ruled that the 1929 law was unconstitutional as no such provisions existed in the law as written. The North Carolina General Assembly went on in the wake of ''Brewer v. Valk'' to enact House Bill 1013, removing the constitutional objections to the law, thereby forming the Eugenics Board and creating the framework which would remain in force for over thirty years. The Board was granted authority over all sterilization proceedings undertaken in the State, which had previously been devolved to various governing bodies or heads of penal and charitable institutions supported in whole or in part by the State. A study from Gregory N. Price, William Darity Jr., and Rhonda V. Sharpe argues that from 1958 to 1968, sterilization in North Carolina was specifically targeted towards Black Americans, with the intended effect of racial eugenics. Sharpe, of the Women's Institute for Science, Equity, and Race, argues that this is an example of the need to disaggregate data that might otherwise overlook the experiences of Black women.1971–1977

In the 1970s the Eugenics Board was moved around from department to department, as sterilization operations declined in the state. In 1971, an act of the legislature transferred the EBNC to the then newly created Department of Human Resources (DHR), and the secretary of that department was given managerial and executive authority over the board. Under a 1973 law, the Eugenics Board was transformed into the Eugenics Commission. Members of the commission were appointed by the governor, and included the director of the Division of Social and Rehabilitative Services of the DHR, the director of Health Services, the chief medical officer of a state institution for the feeble-minded or insane, the chief medical officer of the DHR in the area of mental health services, and the state attorney general. In 1974 the legislature transferred to the judicial system the responsibility for any proceedings. 1976 brought a new challenge to the law with the case of In re Sterilization of Joseph Lee Moore in which an appeal was heard by the North Carolina Supreme Court. The petitioner's case was that the court had not appointed counsel at State expense to advise him of his rights prior to sterilization being performed. While the court noted that there was discretion within the law to approve a fee for the service of an expert, it was not constitutionally required. The court went on to declare that the involuntary sterilization of citizens for the public good was a legitimate use of the police power of the state, further noting that "The people of North Carolina have a right to prevent the procreation of children who will become a burden on the state." The ruling upholding the constitutionality was notable in both its relatively late date (many other States had ceased performing sterilization operations shortly after WWII) and its language justifying state intervention on the grounds of children being a potential burden to the public. The Eugenics Commission was formally abolished by the legislature in 1977.2000-present

In 2003, the N.C. General Assembly formally repealed the last involuntary sterilization law, replacing it with one that authorizes sterilization of individuals unable to give informed consent only in the case of medical necessity. The law explicitly ruled out sterilizations "solely for the purpose of sterilization or for hygiene or convenience."Justification of Eugenics Policy

Legal

At the time of the Board's formation there was a body of thought that viewed the practice of eugenics as both necessary for the public good and for the private citizen. Following ''Buck v. Bell'', the Supreme Court was often cited both domestically and internationally as a foundation for eugenics policies.

In ''Buck v. Bell'' Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, in support of eugenics policy, that

Despite the Supreme Court rulings in support of eugenics as constitutionally permitted, even as late as 1950 some physicians in North Carolina were still concerned about the legality of sterilization. Efforts were made to reassure the medical community that the laws were both constitutionally sound and specifically exempting physicians from liability.

At the time of the Board's formation there was a body of thought that viewed the practice of eugenics as both necessary for the public good and for the private citizen. Following ''Buck v. Bell'', the Supreme Court was often cited both domestically and internationally as a foundation for eugenics policies.

In ''Buck v. Bell'' Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, in support of eugenics policy, that

Despite the Supreme Court rulings in support of eugenics as constitutionally permitted, even as late as 1950 some physicians in North Carolina were still concerned about the legality of sterilization. Efforts were made to reassure the medical community that the laws were both constitutionally sound and specifically exempting physicians from liability.

Public good

Framing eugenics as supporting the public good was fundamental to how the law was written. It was argued that both for the benefit of the private citizen, and for the costs to society of future possible childbirths, eugenics were a sound and moral way to proceed. This was stated in the Board's manual of policies and procedures, in which the practice was justified: * Sterilization has one effect only—it prevents parenthood. * It is not a punishment; it is a protection; and therefore carries no stigma or humiliation. * It in no way unsexes the party sterilized. * Sterilization is approved by the families and friends of the sterilized. * It is approved by medical staffs, probation officers, and social workers generally wherever they have come in contact with patients who have been sterilized. * It permits patients, who would otherwise be confined to institutions during the fertile period of life, to return to their homes and friends. * The records show that many moron girls paroled from institutions after sterilization have married and are happy and succeeding fairly well. They could never have managed and cared for children, to say nothing of the possible inheritance and fate of such children. * Homes are kept together by sterilization of husband or wife in many mild cases of mental disease, thus removing the dread by the normal spouse of the procreation of a defective child and permitting normal marital companionship. * There is no discovery Vitally affecting the life, happiness and well-being of the human race in the last quarter of a century about which intelligent people know less than they know about modern sterilization. The operation is simple; it removes no organ or tissue of the body. It has no effect on the patient except to prevent parenthood. Under conservative laws, sanely and equitably administered, these discoveries developed by the medical profession now offer to the mentally ill, feeble-minded, and epileptic the protection of sterilization. In the press, opinion articles were published arguing for a greater use of eugenics, in which many of the reasons above were cited as justification. Even the ''Winston-Salem Journal

The ''Winston-Salem Journal'' is an American, English language daily newspaper primarily serving Winston-Salem and Forsyth County, North Carolina. It also covers Northwestern North Carolina.

The paper is owned by Lee Enterprises. ''The Journa ...

'', which would be a significant force in illuminating North Carolina's past eugenics abuses in the modern era, was not immune. In 1948 the newspaper published an editorial entitled "The Case for Sterilization - Quantity vs. Quality" that went into great detail extolling the virtues of 'breeding' for the general public good.

Proponents of eugenics did not restrict its use to the 'feeble-minded'. In many cases, more ardent authors included the blind, deaf-mutes, and people with diseases like heart disease or cancer in the general category of those who should be sterilized. The argument was twofold; that parents likely to give birth to 'defective' children should not allow it, and that healthy children borne to 'defective' parents would be doomed to an 'undesirable environment'.

Wallace Kuralt, Mecklenburg County's welfare director from 1945 to 1972, was a leader in transitioning the work of state eugenics from looking only at medical conditions to considering poverty as a justification for state sterilization. Under Kuralt's tenure, Mecklenburg county became far and away the largest source of sterilizations in the state. He supported this throughout his life in his writings and interviews, where he made plain his conviction that sterilization was a force for good in fighting poverty. In a 1964 interview with the ''Charlotte Observer'', Kuralt said:

Among public and private groups that published articles advocating for eugenics, the Human Betterment League was a significant advocate for the procedure within North Carolina. This organization, founded by Procter & Gamble heir Clarence Gamble, provided experts, written material and monetary support to the eugenics movement. Many pamphlets and publications were created by the league advocating the group's position which were then distributed throughout the state. One pamphlet entitled "You Wouldn't Expect ..." laid out a series of rhetorical questions to argue the point that those considered 'defective' were unable to be good parents.

Legacy

Number of operations

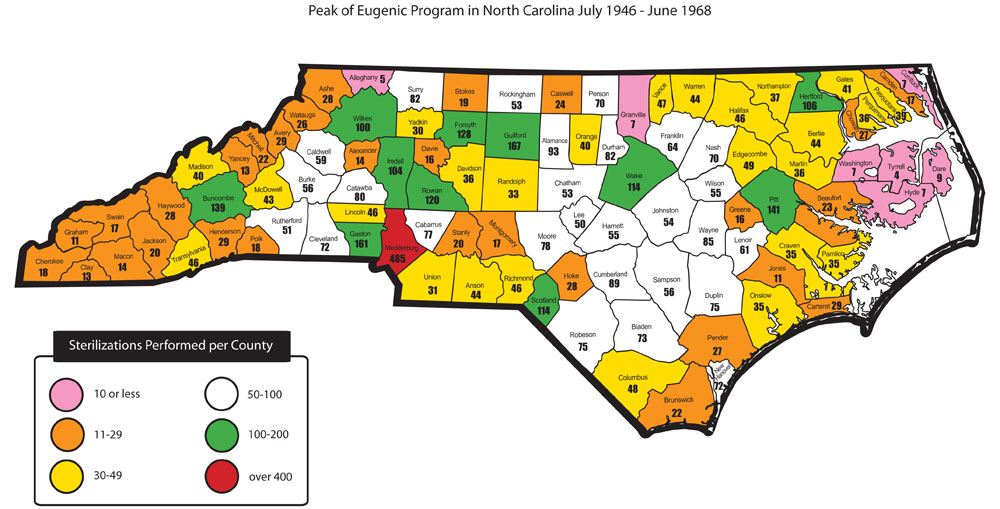

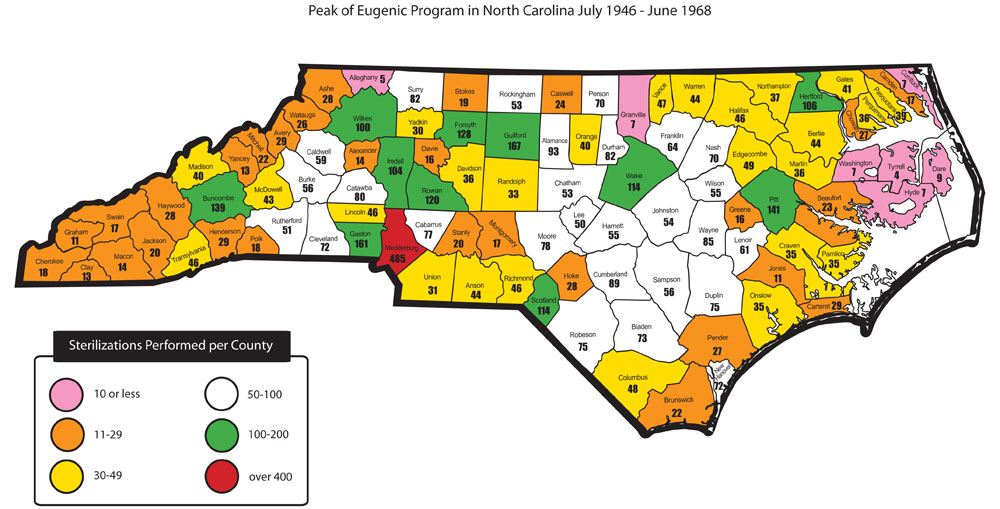

While it is not known exactly how many people were sterilized during the lifetime of the law, the Task Force established by Governor Beverly Perdue estimated the total at around 7,500. They provided a summary of the estimated number of operations broken down by time period. This does not include sterilizations that may have occurred at a local level by doctors and hospitals.

The report went on to provide a breakdown by county. There were no counties in North Carolina that performed no operations, though the spread was marked, going from as few as 4 in Tyrrell county, to 485 in

While it is not known exactly how many people were sterilized during the lifetime of the law, the Task Force established by Governor Beverly Perdue estimated the total at around 7,500. They provided a summary of the estimated number of operations broken down by time period. This does not include sterilizations that may have occurred at a local level by doctors and hospitals.

The report went on to provide a breakdown by county. There were no counties in North Carolina that performed no operations, though the spread was marked, going from as few as 4 in Tyrrell county, to 485 in Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label= Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schweri ...

county.

Some research into the historical data in North Carolina has drawn links between race and sterilization rates. One study performed in 2010 by Gregory Price and William Darity Jr described the practice as "racially biased and genocidal". In the study, the researchers showed that as the black population of a county increased, the number of sterilizations increased disproportionately; that black citizens were more likely, all things being equal, to being recommended for sterilization than whites.

Poverty and sterilization were also closely bound. Since social workers concerned themselves with those accepting welfare and other public assistance, there was a strong impetus to recommending sterilization to families as a means of controlling their economic situation. This was sometimes done under duress, when benefits were threatened as a condition of undergoing the surgery.

What made the picture more complicated was the fact that in some cases, individuals sought out sterilization. Since those in poverty had fewer choices for birth control, having a state-funded procedure to guarantee no further children was attractive to some mothers. Given the structure of the process however, women found themselves needing to be described as unfit mothers or welfare burdens in order to qualify for the program, rather than simply asserting reproductive control.

Personal stories

Many stories from those directly affected by the Board's work have come to light over the past several years. During the hearings from the NC Justice for Sterilization Victims Foundation many family members and individuals personally testified to the impact that the procedures had had on them.Elaine Riddick Jessie

Elaine Riddick was born inPerquimans County

Perquimans County ()

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the