Norse exploration of North America on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Norse exploration of North America began in the late 10th century, when

According to the

According to the  Norse Greenland consisted of two settlements. The

Norse Greenland consisted of two settlements. The

The settlements began to decline in the 14th century. The Western Settlement was abandoned around 1350, and the last bishop at Garðar died in 1377. After a marriage was recorded in 1408, no written records mention the settlers. It is probable that the Eastern Settlement was defunct by the late 15th century. The most recent

The settlements began to decline in the 14th century. The Western Settlement was abandoned around 1350, and the last bishop at Garðar died in 1377. After a marriage was recorded in 1408, no written records mention the settlers. It is probable that the Eastern Settlement was defunct by the late 15th century. The most recent

According to the

According to the

Using the routes, landmarks,

Using the routes, landmarks,

here

Leif's brother

For centuries it remained unclear whether the Icelandic stories represented real voyages by the Norse to North America. Although the idea of Norse voyages to, and a colony in, North America was discussed by Swiss scholar Paul Henri Mallet in his book ''Northern Antiquities'' (English translation 1770), the sagas first gained widespread attention in 1837 when the Danish antiquarian

For centuries it remained unclear whether the Icelandic stories represented real voyages by the Norse to North America. Although the idea of Norse voyages to, and a colony in, North America was discussed by Swiss scholar Paul Henri Mallet in his book ''Northern Antiquities'' (English translation 1770), the sagas first gained widespread attention in 1837 when the Danish antiquarian  Evidence of the Norse west of Greenland came in the 1960s when archaeologist

Evidence of the Norse west of Greenland came in the 1960s when archaeologist  In 2021 some wood from L'Anse aux Meadows was dated to 1021, reinforcing the archaeological evidence that the settlement was built by Norsemen. The same year, Yale acknowledged that the Vinland Map is a forgery and

In 2021 some wood from L'Anse aux Meadows was dated to 1021, reinforcing the archaeological evidence that the settlement was built by Norsemen. The same year, Yale acknowledged that the Vinland Map is a forgery and

L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada website

Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage website

Freda Harold Research Papers

at Dartmouth College Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Norse Colonization Of The Americas Norse colonization of North America, Populated places established in the 10th century 10th century in North America 15th century in North America

Norsemen

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the pre ...

explored areas of the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

colonizing Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

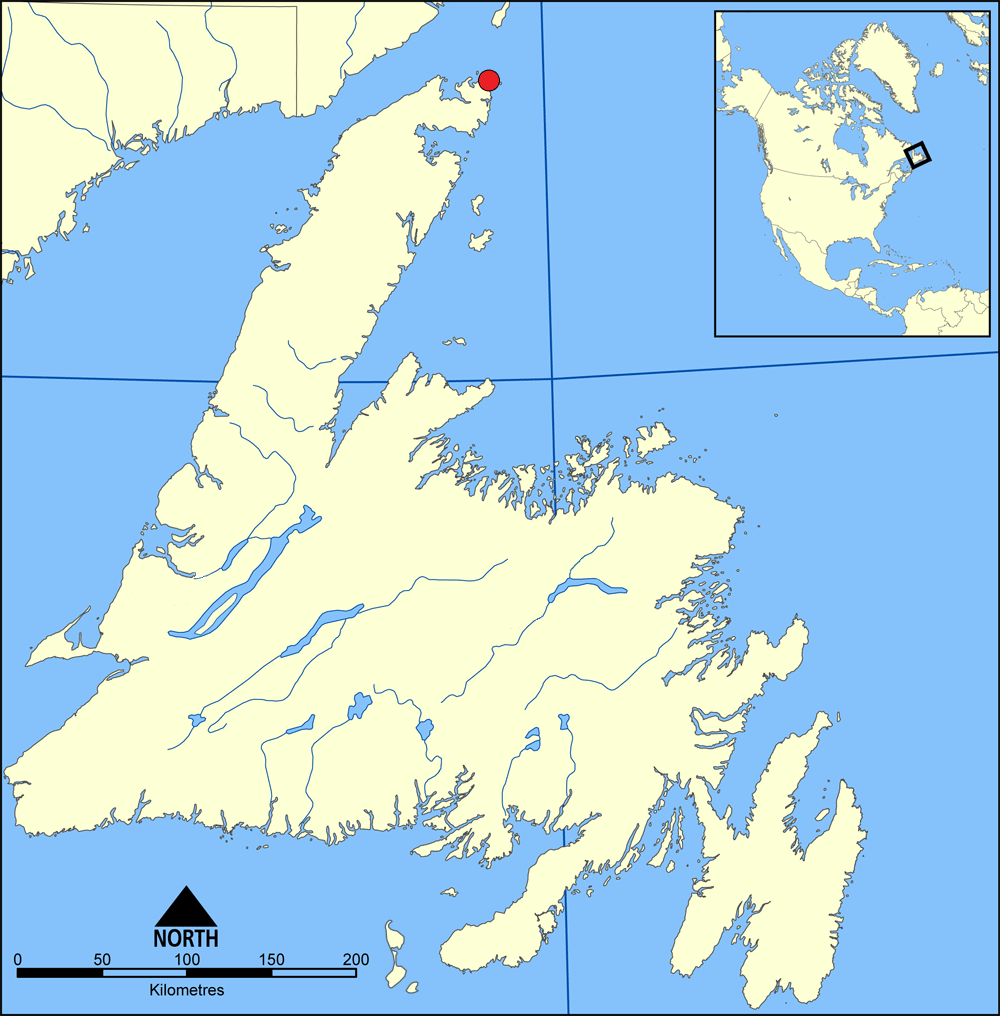

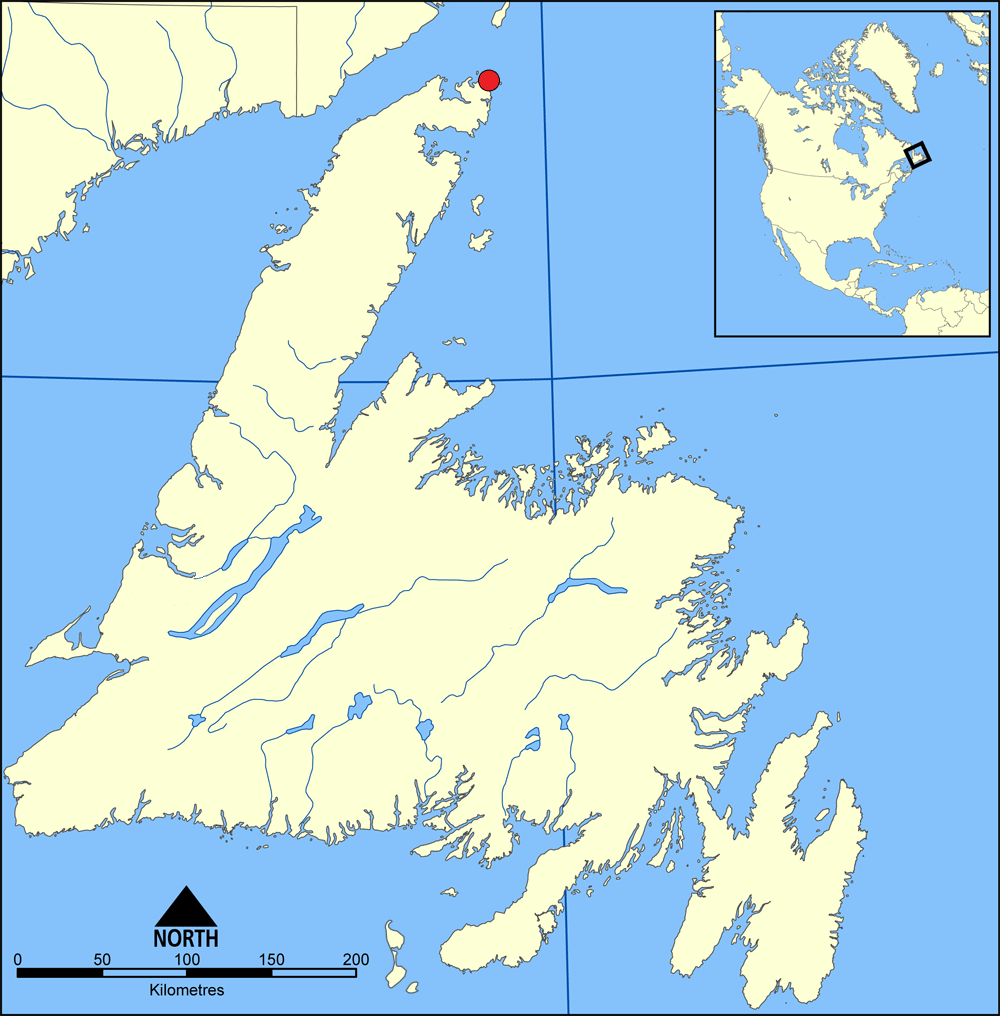

and creating a short term settlement near the northern tip of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

. This is known now as L'Anse aux Meadows

L'Anse aux Meadows ( lit. Meadows Cove) is an archaeological site, first excavated in the 1960s, of a Norse settlement dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. The site is located on the northernmost tip of the island of Newfoundland in the Ca ...

where the remains of buildings were found in 1960 dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. This discovery helped reignite archaeological exploration for the Norse in the North Atlantic. This single settlement, located on the island of Newfoundland and not on the North American mainland, was abruptly abandoned.

The Norse settlements on Greenland lasted for almost 500 years. L'Anse aux Meadows, the only confirmed Norse site in present-day Canada, was small and did not last as long. Other such Norse voyages are likely to have occurred for some time, but there is no evidence of any Norse settlement on mainland North America lasting beyond the 11th century.

The Norse exploration of North America has been subject to numerous controversies concerning the European exploration and Settlement of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

. Pseudoscientific and pseudo-historical theories have emerged since the public acknowledgment of these Norse expeditions and settlements.

Norse Greenland

According to the

According to the Sagas of Icelanders

The sagas of Icelanders ( is, Íslendingasögur, ), also known as family sagas, are one genre of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives mostly based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early el ...

, Norsemen from Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

first settled Greenland in the 980s. There is no special reason to doubt the authority of the information that the sagas supply regarding the very beginning of the settlement, but they cannot be treated as primary evidence for the history of Norse Greenland because they embody the literary preoccupations of writers and audiences in medieval Iceland that are not always reliable.

Erik the Red

Erik Thorvaldsson (), known as Erik the Red, was a Norse explorer, described in medieval and Icelandic saga sources as having founded the first settlement in Greenland. He most likely earned the epithet "the Red" due to the color of his hair a ...

(Old Norse: Eiríkr rauði), having been banished from Iceland for manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

, explored the uninhabited southwestern coast of Greenland during the three years of his banishment. He made plans to entice settlers to the area, naming it Greenland on the assumption that "people would be more eager to go there because the land had a good name". The inner reaches of one long fjord

In physical geography, a fjord or fiord () is a long, narrow inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created by a glacier. Fjords exist on the coasts of Alaska, Antarctica, British Columbia, Chile, Denmark, Germany, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Ice ...

, named ''Eiriksfjord'' after him, was where he eventually established his estate '' Brattahlid''. He issued tracts of land to his followers.Wernick, Robert; ''The Seafarers: The Vikings,'' (1979), 176 pages, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia: .

Norse Greenland consisted of two settlements. The

Norse Greenland consisted of two settlements. The Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

was at the southwestern tip of Greenland, while the Western Settlement

The Western Settlement ( non, Vestribygð ) was a group of farms and communities established by Norsemen from Iceland around 985 in medieval Greenland. Despite its name, the Western Settlement was more north than west of its companion Eastern Sett ...

was about 500 km up the west coast, inland from present-day Nuuk

Nuuk (; da, Nuuk, formerly ) is the capital and largest city of Greenland, a constituent country of the Kingdom of Denmark. Nuuk is the seat of government and the country's largest cultural and economic centre. The major cities from other co ...

. A smaller settlement near the Eastern Settlement is sometimes considered the Middle Settlement

Ivittuut (formerly, Ivigtût) ( Kalaallisut: "Grassy Place") is an abandoned mining town near Cape Desolation in southwestern Greenland, in the modern Sermersooq municipality on the ruins of the former Norse Middle Settlement.

Ivittuut is one o ...

. The combined population was around 2,000–3,000. At least 400 farms have been identified by archaeologists. Norse Greenland had a bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

(at Garðar) and exported walrus ivory

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in the fami ...

, furs, rope, sheep, whale and seal blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians.

Description

Lipid-rich, collagen fiber-laced blubber comprises the hypodermis and covers the whole body, except for pa ...

, live animals such as polar bear

The polar bear (''Ursus maritimus'') is a hypercarnivorous bear whose native range lies largely within the Arctic Circle, encompassing the Arctic Ocean, its surrounding seas and surrounding land masses. It is the largest extant bear specie ...

s, supposed "unicorn horns" (in reality narwhal tusks), and cattle hides. In 1126, the population requested a bishop (headquartered at Garðar), and in 1261, they accepted the overlordship of the Norwegian king. They continued to have their own law and became almost completely politically independent after 1349, the time of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

. In 1380, the Kingdom of Norway entered into a personal union with the Kingdom of Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

.

Western trade and decline

There is evidence of Norse trade with the natives (called the by the Norse). The Norse would have encountered both Native Americans (theBeothuk

The Beothuk ( or ; also spelled Beothuck) were a group of indigenous people who lived on the island of Newfoundland.

Beginning around AD 1500, the Beothuk culture formed. This appeared to be the most recent cultural manifestation of peoples w ...

, related to the Algonquin) and the Thule

Thule ( grc-gre, Θούλη, Thoúlē; la, Thūlē) is the most northerly location mentioned in ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek and Latin literature, Roman literature and cartography. Modern interpretations have included Orkney, Shet ...

, the ancestors of the Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

. The Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

had withdrawn from Greenland before the Norse settlement of the island. Items such as comb fragments, pieces of iron cooking utensils and chisels, chess pieces, ship rivets

A rivet is a permanent mechanical fastener. Before being installed, a rivet consists of a smooth cylindrical shaft with a head on one end. The end opposite to the head is called the ''tail''. On installation, the rivet is placed in a punched o ...

, carpenter's planes, and oaken ship fragments used in Inuit boats have been found far beyond the traditional range of Norse colonization. A small ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is ...

statue that appears to represent a European

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

has also been found among the ruins of an Inuit community house.

radiocarbon

Carbon-14, C-14, or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic materials is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and coll ...

date found in Norse settlements as of 2002 was 1430 (±15 years). Several theories have been advanced to explain the decline.

The Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

of this period would have made travel between Greenland and Europe, as well as farming, more difficult; although seal and other hunting provided a healthy diet, there was more prestige in cattle farming, and there was increased availability of farms in Scandinavian countries depopulated by famine and plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

epidemics. In addition, Greenlandic ivory may have been supplanted in European markets by cheaper ivory from Africa. Despite the loss of contact with the Greenlanders, the Norwegian-Danish crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

continued to consider Greenland a possession.

Not knowing whether the old Norse civilization remained in Greenland or not—and worried that if it did, it would still be Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

200 years after the Scandinavian homelands had experienced the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

—a joint merchant-clerical expedition led by the Nowegian missionary Hans Egede

Hans Poulsen Egede (31 January 1686 – 5 November 1758) was a Dano-Norwegian Lutheran missionary who launched mission efforts to Greenland, which led him to be styled the Apostle of Greenland. He established a successful mission among the Inui ...

was sent to Greenland in 1721. Though this expedition found no surviving Europeans, it marked the beginning of Denmark's re-assertion of sovereignty over the island.

Climate and Norse Greenland

Norse Greenlanders were limited to scattered fjords on the island that provided a spot for their animals (such as cattle, sheep, goats, dogs, and cats) to be kept and farms to be established. In these fjords, the farms depended upon stables (''byre

A stable is a building in which livestock, especially horses, are kept. It most commonly means a building that is divided into separate stalls for individual animals and livestock. There are many different types of stables in use today; th ...

s'') to host their livestock in the winter, and routinely culled their herds so that they could survive the season. The coming warmer seasons meant that livestock were taken from their byres to pasture, the most fertile being controlled by the most powerful farms and the church. What was produced by livestock and farming was supplemented with subsistence hunting of mainly seal and caribou as well as walrus for trade. The Norse mainly relied on the ''Nordrsetur'' hunt, a communal hunt of migratory harp seals that would take place during spring.

Trade was highly important to the Greenland Norse and they relied on imports of lumber due to the barrenness of Greenland. In turn they exported goods such as walrus ivory and hide, live polar bears, and narwhal tusks. Ultimately these setups were vulnerable as they relied on migratory patterns created by climate as well as the viability of the few fjords on the island. A portion of the time the Greenland settlements existed was during the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

and the climate was, overall, becoming cooler and more humid. As climate began to cool and humidity began to increase, this brought more storms, longer winters and shorter springs, and affected the migratory patterns of the harp seal. Pasture space began to dwindle and fodder yields for the winter became much smaller. This combined with regular herd culling made it hard to maintain livestock, especially for the poorest of the Greenland Norse. Closer to the Eastern Settlement, temperatures remained stable but a prolonged drought reduced fodder production. In spring, the voyages to where migratory harp seal

The harp seal (''Pagophilus groenlandicus''), also known as Saddleback Seal or Greenland Seal, is a species of earless seal, or true seal, native to the northernmost Atlantic Ocean and Arctic Ocean. Originally in the genus ''Phoca'' with a number ...

s could be found became more dangerous due to more frequent storms, and the lower population of harp seals meant that ''Nordrsetur'' hunts became less successful, making subsistence hunting extremely difficult. The strain on resources made trade difficult, and as time went on, Greenland exports lost value in the European market due to competing countries and the lack of interest in what was being traded. Trade in elephant ivory began competing with the trade in walrus tusks that provided income to Greenland, and there is evidence that walrus over-hunting, particularly of the males with larger tusks, led to walrus population declines.

In addition, it seemed that the Norse were unwilling to integrate with the Thule people

The Thule (, , ) or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by the year 1000 and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people ...

of Greenland, either through marriage or culture. There is evidence of contact as seen through the Thule archaeological record including ivory depictions of the Norse as well as bronze and steel artifacts. However, there is essentially no material evidence of the Thule among Norse artifacts. In older research it was posited that it was not climate change alone that led to Norse decline, but also their unwillingness to adapt. For example, if the Norse had decided to focus their subsistence hunting on the ringed seal

The ringed seal (''Pusa hispida'') is an earless seal inhabiting the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. The ringed seal is a relatively small seal, rarely greater than 1.5 m in length, with a distinctive patterning of dark spots surrounded by light g ...

(which could be hunted year round, though individually), and decided to reduce or do away with their communal hunts, food would have been much less scarce during the winter season. Also, had Norse individuals used skin instead of wool to produce their clothing, they would have been able to fare better nearer to the coast, and wouldn't have been as confined to the fjords.

However, more recent research has shown that the Norse did try to adapt in their own ways. Some of these attempts included increased subsistence hunting. A significant number of bones of marine animals can be found at the settlements, suggesting increased hunting with the absence of farmed food. In addition, pollen records show that the Norse didn't always devastate the small forests and foliage as previously thought. Instead the Norse ensured that overgrazed or overused sections were given time to regrow and moved to other areas. Norse farmers also attempted to adapt. With the increased need for winter fodder and smaller pastures, they would self-fertilize their lands in an attempt to keep up with the new demands caused by the changing climate. However, even with these attempts, climate change was not the only thing putting pressure on the Greenland Norse. The economy was changing, and the exports they relied on were losing value. Current research suggests that the Norse were unable to maintain their settlements because of economic and climatic change happening at the same time.

Vinland

According to the

According to the Icelandic sagas

The sagas of Icelanders ( is, Íslendingasögur, ), also known as family sagas, are one genre of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives mostly based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early el ...

''Eirik the Red's Saga

The ''Saga of Erik the Red'', in non, Eiríks saga rauða (), is an Icelandic saga on the Norse exploration of North America. The original saga is thought to have been written in the 13th century. It is preserved in somewhat different versions ...

'', ''Saga of the Greenlanders

''Grœnlendinga saga'' () (spelled ''Grænlendinga saga'' in modern Icelandic and translated into English as the Saga of the Greenlanders) is one of the sagas of Icelanders. Like the ''Saga of Erik the Red'', it is one of the two main sources on t ...

'', plus chapters of the ''Hauksbók

Hauksbók (; 'Book of Haukr'), Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar AM 371 4to, AM 544 4to and AM 675 4to, is an Icelandic manuscript, now in three parts but originally one, dating from the 14th century. It was created by the Icelander Haukr E ...

'' and the ''Flatey Book ''Flatey'' may refer to either of two islands in Iceland:

*Flatey, Breiðafjörður

* Flatey, Skjálfandi

See also

* ''Flateyjarbók

''Flateyjarbók'' (; "Book of Flatey") is an important medieval Icelandic manuscript. It is also known as GkS ...

''the Norse started to explore lands to the west of Greenland only a few years after the Greenland settlements were established. In 985, while sailing from Iceland to Greenland with a migration fleet consisting of 400–700 settlers and 25 other ships (14 of which completed the journey), a merchant named Bjarni Herjólfsson

Bjarni Herjólfsson ( 10th century) was a Norse- Icelandic explorer who is believed to be the first known European discoverer of the mainland of the Americas, which he sighted in 986.

Life

Bjarni was born to Herjólfr, son of Bárdi Herjólfsso ...

was blown off course, and after three days' sailing he sighted land west of the fleet. Bjarni was only interested in finding his father's farm, but he described his findings to Leif Erikson

Leif Erikson, Leiv Eiriksson, or Leif Ericson, ; Modern Icelandic: ; Norwegian: ''Leiv Eiriksson'' also known as Leif the Lucky (), was a Norse explorer who is thought to have been the first European to have set foot on continental North ...

who explored the area in more detail and planted a small settlement fifteen years later.

The sagas describe three separate areas that were explored: Helluland

Helluland () is the name given to one of the three lands, the others being Vinland and Markland, seen by Bjarni Herjólfsson, encountered by Leif Erikson and further explored by Thorfinn Karlsefni Thórdarson around AD 1000 on the North Atlantic c ...

, which means "land of the flat stones"; Markland

Markland () is the name given to one of three lands on North America's Atlantic shore discovered by Leif Eriksson around 1000 AD. It was located south of Helluland and north of Vinland.

Although it was never recorded to be settled by Norsemen, ...

, "the land of forests", definitely of interest to settlers in Greenland where there were few trees; and Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland ( non, Vínland ᚠᛁᚾᛚᛅᚾᛏ) was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John ...

, "the land of wine", found somewhere south of Markland. It was in Vinland that the settlement described in the sagas was founded.

Markland was first mentioned in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

area in 1345 by the Milanese friar Galvaneus Flamma

Galvano Fiamma (1283–1344) was an Italian Dominican and chronicler of Milan. He appears to have been the first European in the Mediterranean area to describe the New World. His numerous historical writings include the ''Chronica Galvagnana'', ...

. He probably derived it from oral sources in Genoa.

Leif's winter camp

* Land of the '' Risi'' (a mythical location) *Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

* Helluland

Helluland () is the name given to one of the three lands, the others being Vinland and Markland, seen by Bjarni Herjólfsson, encountered by Leif Erikson and further explored by Thorfinn Karlsefni Thórdarson around AD 1000 on the North Atlantic c ...

(Baffin Island

Baffin Island (formerly Baffin Land), in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is , slightly larger than Spain; its population was 13,039 as of the 2021 Canadia ...

)

* Markland

Markland () is the name given to one of three lands on North America's Atlantic shore discovered by Leif Eriksson around 1000 AD. It was located south of Helluland and north of Vinland.

Although it was never recorded to be settled by Norsemen, ...

(the Labrador Peninsula

The Labrador Peninsula, or Quebec-Labrador Peninsula, is a large peninsula in eastern Canada. It is bounded by the Hudson Bay to the west, the Hudson Strait to the north, the Labrador Sea to the east, and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the southe ...

)

* Land of the ''Skræling

''Skræling'' (Old Norse and Icelandic: ''skrælingi'', plural ''skrælingjar'') is the name the Norse Greenlanders used for the peoples they encountered in North America (Canada and Greenland). In surviving sources, it is first applied to the ...

'' (location undetermined)

* Promontory of Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland ( non, Vínland ᚠᛁᚾᛚᛅᚾᛏ) was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John ...

(the Great Northern Peninsula

The Great Northern Peninsula (Inuttitut: ''Ikkarumiklua'') is the largest and longest peninsula of Newfoundland, Canada, approximately 270 km long and 90 km wide at its widest point and encompassing an area of 17,483 km2. It is de ...

)

Using the routes, landmarks,

Using the routes, landmarks, currents

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (stre ...

, rocks, and winds that Bjarni had described to him, Leif sailed from Greenland westward across the Labrador Sea, with a crew of 35—sailing the same knarr

A knarr is a type of Norse merchant ship used by the Vikings. The knarr ( non, knǫrr, plural ) was constructed using the same clinker-built method as longships, karves, and faerings.

History

''Knarr'' is the Old Norse term for a type of shi ...

Bjarni had used to make the voyage. He described Helluland as "level and wooded, with broad white beaches wherever they went and a gently sloping shoreline." Leif and others had wanted his father, Erik the Red, to lead this expedition and talked him into it. However, as Erik attempted to join his son Leif on the voyage towards these new lands, he fell off his horse as it slipped on the wet rocks near the shore; thus he was injured and stayed behind.

Sometime around AD 1000, Leif spent the winter, probably near Cape Bauld

Cape Bauld is a headland located at the northernmost point of Quirpon Island, an island just northeast of the Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Cape Bauld, slightly north and east of C ...

on the northern tip of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, where one day his foster father Tyrker

Tyrker (or Tyrkir) is a character mentioned in the Norsemen, Norse Saga of the Greenlanders. He accompanied Leif on his voyage of discovery around the year 1000, and is portrayed as an older male servant. He is referred to as “foster father” b ...

was found drunk, on what the saga describes as "wine-berries." Squashberries, gooseberries

Gooseberry ( or (American and northern British) or (southern British)) is a common name for many species of ''Ribes'' (which also includes currants), as well as a large number of plants of similar appearance. The berries of those in the genu ...

, and cranberries

Cranberries are a group of evergreen dwarf shrubs or trailing vines in the subgenus ''Oxycoccus'' of the genus ''Vaccinium''. In Britain, cranberry may refer to the native species ''Vaccinium oxycoccos'', while in North America, cranberry m ...

all grew wild in the area. There are varying explanations for Leif apparently describing fermented berries as "wine."

Leif spent another winter at "Leifsbúðir" without conflict, and sailed back to Brattahlíð

Brattahlíð (), often anglicised as Brattahlid, was Erik the Red's estate in the Eastern Settlement Viking colony he established in south-western Greenland toward the end of the 10th century. The present settlement of Qassiarsuk, approximately ...

in Greenland to assume filial duties to his father.

Thorvald's voyage

A couple years later,See chronologhere

Leif's brother

Thorvald Eiriksson

Thorvald Eiriksson ( non, Þórvaldr Eiríksson ; Modern Icelandic: ) was the son of Erik the Red and brother of Leif Erikson.

The only Medieval Period source material available regarding Thorvald Eiriksson are the two '' Vinland sagas''; the ...

sailed with a crew of 30 men to Vinland and spent the following winter at Leif's camp. In the spring, Thorvald attacked nine of the native people who were sleeping under three skin-covered canoe

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the term ...

s. The ninth victim escaped and soon came back to the Norse camp with a force. Thorvald was killed by an arrow that succeeded in passing through the barricade

Barricade (from the French ''barrique'' - 'barrel') is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction. Adopted as a military term, a barricade denot ...

. Although brief hostilities ensued, the Norse explorers stayed another winter and left the following spring. Subsequently, another of Leif's brothers, Thorstein, sailed to the New World to retrieve his dead brother's body, but he died before leaving Greenland.

Karlsefni's expedition

A few years later,Thorfinn Karlsefni

Thorfinn Karlsefni Thórdarson was an Icelandic explorer. Around the year 1010, he followed Leif Eriksson's route to Vinland in a short-lived attempt to establish a permanent settlement there with his wife Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir and their fol ...

, also known as "Thorfinn the Valiant", supplied three ships

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished ...

with livestock and 160 men and women (although another source sets the number of settlers at 250). After a cruel winter, he headed south and landed at ''Straumfjord''. He later moved to ''Straumsöy'', possibly because the current was stronger there. A sign of peaceful relations between the indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

and the Norsemen is noted here. The two sides barter

In trade, barter (derived from ''baretor'') is a system of exchange in which participants in a transaction directly exchange goods or services for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money. Economists distingu ...

ed with furs and gray squirrel Gray squirrel or grey squirrel may refer to several species of squirrel indigenous to North America:

*The eastern gray squirrel (''Sciurus carolinensis''), from the eastern United States and southeastern Canada; introduced into the United Kingdom, I ...

skins for milk and red cloth, which the natives tied around their heads as a sort of headdress

Headgear, headwear, or headdress is the name given to any element of clothing which is worn on one's head, including hats, helmets, turbans and many other types. Headgear is worn for many purposes, including protection against the elements, de ...

.

There are conflicting stories but one account states that a bull belonging to Karlsefni came storming out of the wood, so frightening the natives that they ran to their skin-boats and rowed away. They returned three days later, in force. The natives used catapults, hoisting "a large sphere on a pole; it was dark blue in color" and about "the size of a sheep's stomach", which flew over the heads of the men and "made an ugly din when it struck the ground".

The Norsemen retreated. Leif Erikson's half-sister Freydís Eiríksdóttir

Freydís Eiríksdóttir (born 970) was a Icelandic woman said to be the daughter of Erik the Red (as in her patronym), who figured prominently in the Norse exploration of North America as an early colonist of Vinland, while her brother, Leif E ...

was pregnant and unable to keep up with the retreating Norsemen. She called out to them to stop fleeing from "such pitiful wretches", adding that if she had weapons, she could do better than that. Freydís seized the sword belonging to a man who had been killed by the natives. She pulled one of her breasts out of her bodice and slapped it with the sword, frightening the natives, who fled.

Historiography

For centuries it remained unclear whether the Icelandic stories represented real voyages by the Norse to North America. Although the idea of Norse voyages to, and a colony in, North America was discussed by Swiss scholar Paul Henri Mallet in his book ''Northern Antiquities'' (English translation 1770), the sagas first gained widespread attention in 1837 when the Danish antiquarian

For centuries it remained unclear whether the Icelandic stories represented real voyages by the Norse to North America. Although the idea of Norse voyages to, and a colony in, North America was discussed by Swiss scholar Paul Henri Mallet in his book ''Northern Antiquities'' (English translation 1770), the sagas first gained widespread attention in 1837 when the Danish antiquarian Carl Christian Rafn

Carl Christian Rafn (January 16, 1795 – October 20, 1864) was a Danish historian, translator and antiquarian. His scholarship to a large extent focused on translation of Old Norse literature and related Northern European ancient history. He wa ...

revived the idea of a Viking presence in North America. North America, by the name Winland, first appeared in written sources in a work by Adam of Bremen

Adam of Bremen ( la, Adamus Bremensis; german: Adam von Bremen) (before 1050 – 12 October 1081/1085) was a German medieval chronicler. He lived and worked in the second half of the eleventh century. Adam is most famous for his chronicle ''Gesta ...

from approximately 1075. The most important works about North America and the early Norse activities there, namely the Sagas of Icelanders

The sagas of Icelanders ( is, Íslendingasögur, ), also known as family sagas, are one genre of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives mostly based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early el ...

, were recorded in the 13th and 14th centuries. In 1420, some Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

captives and their kayaks were taken to Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

. The Norse sites were depicted in the Skálholt Map

Skálholt (Modern Icelandic: ; non, Skálaholt ) is a historical site in the south of Iceland, at the river Hvítá.

History

Skálholt was, through eight centuries, one of the most important places in Iceland. A bishopric was established in Sk� ...

, made by an Icelandic teacher in 1570 and depicting part of northeastern North America and mentioning Helluland, Markland and Vinland.

Evidence of the Norse west of Greenland came in the 1960s when archaeologist

Evidence of the Norse west of Greenland came in the 1960s when archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad

Anne Stine Ingstad (11 February 1918 – 6 November 1997) was a Norwegian archaeologist who, along with her husband explorer Helge Ingstad, discovered the remains of a Norse settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows in the Canadian province of Newfo ...

and her husband, outdoorsman and author Helge Ingstad

Helge Marcus Ingstad (30 December 1899 – 29 March 2001) was a Norwegian explorer. In 1960, after mapping some Norse settlements, Ingstad and his wife archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad found remnants of a Viking settlement in L'Anse aux Meadows ...

, excavated a Norse site at L'Anse aux Meadows

L'Anse aux Meadows ( lit. Meadows Cove) is an archaeological site, first excavated in the 1960s, of a Norse settlement dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. The site is located on the northernmost tip of the island of Newfoundland in the Ca ...

in Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

. They found a bronze, ring-headed pin like those the Norse used to fasten their cloaks inside the cooking pit of one of the larger dwellings. A stone oil lamp and a small spindle whorl

A spindle whorl is a disc or spherical object fitted onto the spindle to increase and maintain the speed of the spin. Historically, whorls have been made of materials like amber, antler, bone, ceramic, coral, glass, stone, metal (iron, lead, lead ...

, used as the flywheel of a handheld spindle, were found inside another building. A fragment of a bone needle believed to have been used for knitting was discovered in the firepit of a third dwelling. A small, decorated brass fragment, once gilded

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

, was also discovered. Much slag

Slag is a by-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/base metals (by-prod ...

formed as a by-product from the smelting and working of iron was found on the site along with many iron boat nails or rivets.

In 2012 Canadian researchers identified possible signs of Norse outposts in Nanook

In Inuit religion, Nanook (; iu, ᓇᓄᖅ , lit. "polar bear") was the master of bears, meaning he decided if hunters deserved success in finding and hunting bears and punished violations of taboos. The word was popularized by ''Nanook of the ...

at Tanfield Valley

Tanfield Valley, also referred to as Nanook, is an archaeological site located on the southernmost projection of Baffin Island in the Canada, Canadian territory of Nunavut. It is possible that the site was known to Pre-Columbian Norsemen, Norse e ...

on Baffin Island

Baffin Island (formerly Baffin Land), in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is , slightly larger than Spain; its population was 13,039 as of the 2021 Canadia ...

, as well as on Nunguvik, Willows Island, and Avayalik Avayalik is an island at the far north of the Labrador Peninsula in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is a possible site of early Norse colonization of North America.

See also

*L'Anse aux Meadows

L'Anse aux Meadows ( lit ...

. Unusual fabric cordage found on Baffin Island in the 1980s and stored at the Canadian Museum of Civilization

The Canadian Museum of History (french: Musée canadien de l’histoire) is a national museum on anthropology, Canadian history, cultural studies, and ethnology in Gatineau, Quebec, Canada. The purpose of the museum is to promote the heritage of C ...

was identified in 1999 as possibly of Norse manufacture; that discovery led to more comprehensive exploration of the Tanfield Valley archaeological site for points of contact between Norse Greenlanders and the indigenous Dorset people

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from to between and , that followed the Pre-Dorset and preceded the Thule people (proto-Inuit) in the North American Arctic. The culture and people are named after Cape Dorset (now Kinngait) in N ...

.

In 2021 some wood from L'Anse aux Meadows was dated to 1021, reinforcing the archaeological evidence that the settlement was built by Norsemen. The same year, Yale acknowledged that the Vinland Map is a forgery and

In 2021 some wood from L'Anse aux Meadows was dated to 1021, reinforcing the archaeological evidence that the settlement was built by Norsemen. The same year, Yale acknowledged that the Vinland Map is a forgery and Gordon Campbell

Gordon Muir Campbell, (born January 12, 1948) is a retired Canadian diplomat and politician who was the 35th mayor of Vancouver from 1986 to 1993 and the 34th premier of British Columbia from 2001 to 2011.

He was the leader of the British Co ...

's book ''Norse America'' was published. The book develops his thesis that the "fleeting and ill-documented" idea that Vikings "discovered America" quickly seduced Americans of northern European Protestant descent, some of whom went on to deliberately manufacture evidence to support it.

Pseudohistory

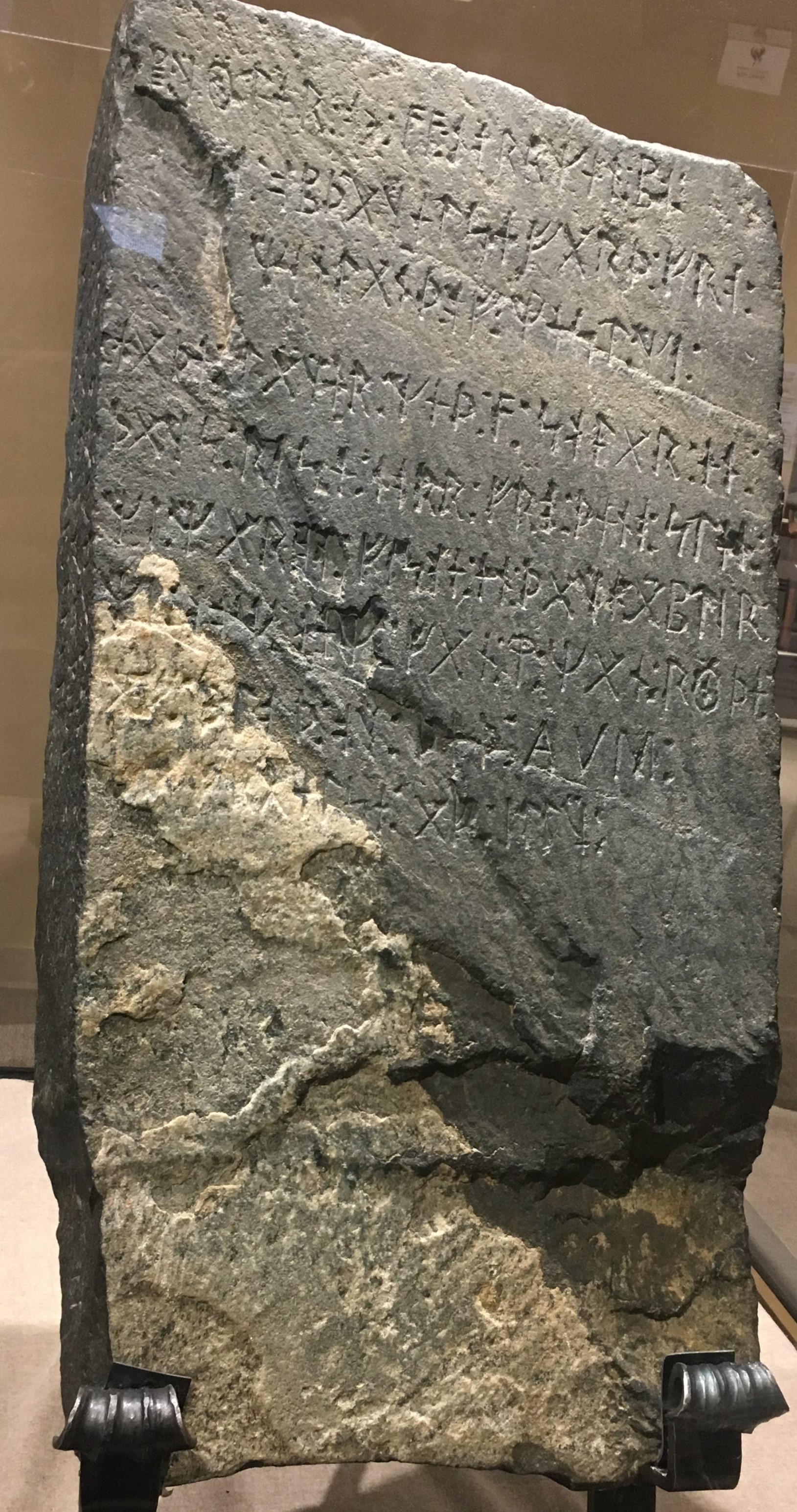

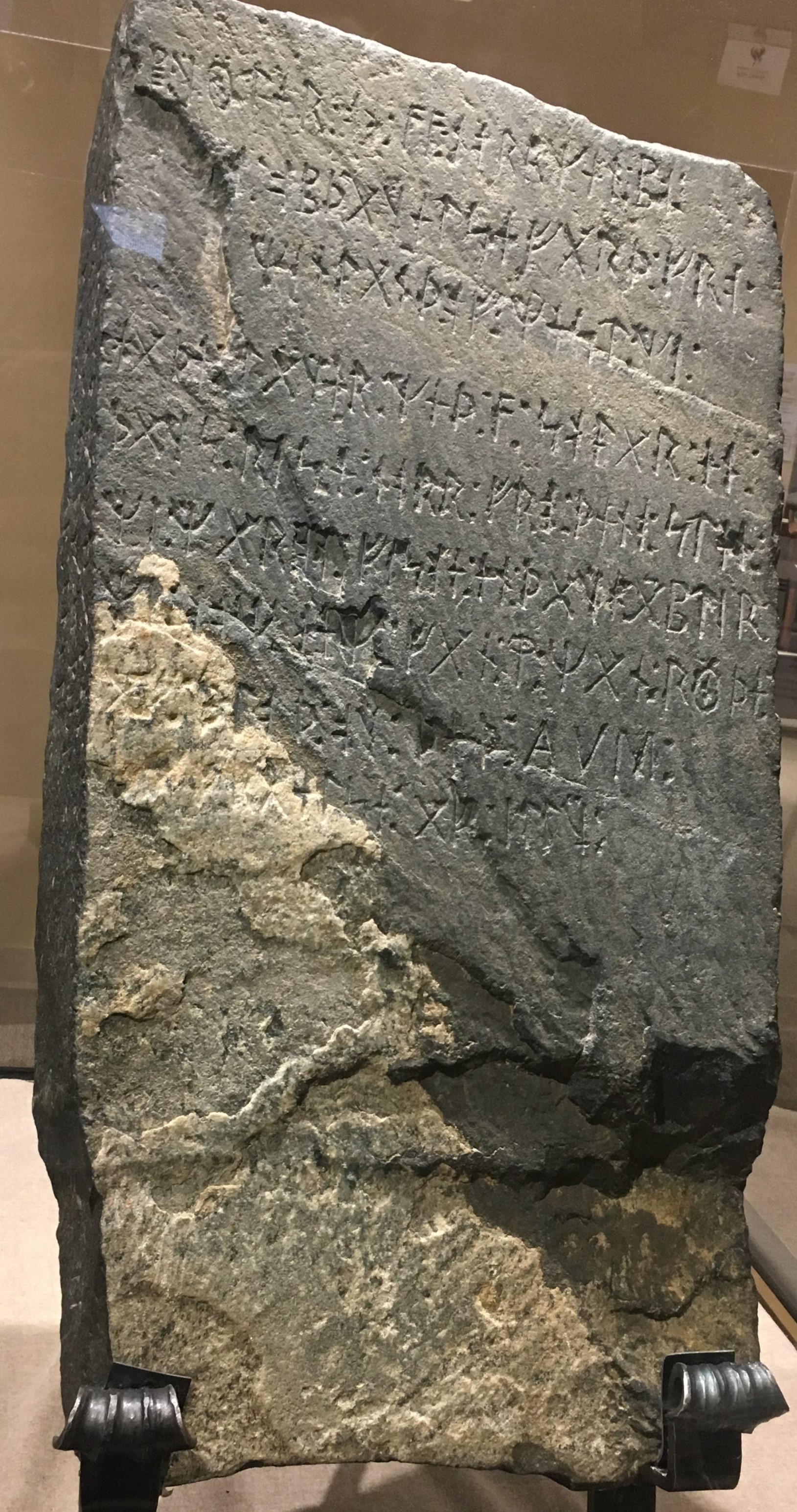

Purportedrunestone

A runestone is typically a raised stone with a runic inscription, but the term can also be applied to inscriptions on boulders and on bedrock. The tradition began in the 4th century and lasted into the 12th century, but most of the runestones da ...

s have been found in North America, most famously the Kensington Runestone

The Kensington Runestone is a slab of greywacke stone covered in runes that was allegedly discovered in central Minnesota in 1898. Olof Öhman, a Swedish immigrant, reported that he unearthed it from a field in the largely rural township of So ...

. These are generally considered forgeries or misinterpretations of Native American petroglyphs.

There are many claims of Norse colonization in New England, none well founded.

Monuments claimed to be Norse include:

* Stone Tower in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, ...

* The petroglyphs

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

on Dighton Rock, from the Taunton River in Massachusetts

* The runes on Narragansett Runestone

Kensington Runestone

In late 1898 Swedish immigrant Olof Öhman stated that he found this rune in Kensington, Minnesota, while clearing land he had recently acquired. He stated that the rune was lying face down and tangled in various roots near the crest of a small Hillock, knoll within an area of wetlands. After Olaus J. Breda (1853–1916), professor of Scandinavian Languages and Literature in the Scandinavian Department at the University of Minnesota analyzed the inscriptions, she declared the rune to be a forgery and published a discrediting article in ''Symra'' in 1910. Breda also forwarded copies of the inscription to various contemporary Scandinavian linguists and historians, such as Oluf Rygh, Sophus Bugge, Gustav Storm, Magnus Olsen and Adolf Noreen. They "unanimously pronounced the Kensington inscription a fraud and forgery of recent date".Horsford's Norumbega

The nineteenth-century Harvard chemist Eben Norton Horsford connected the Charles River Basin to places described in the Norse sagas and elsewhere, notably Norumbega. He published several books on the topic and had plaques, monuments, and statues erected in honor of the Norse. His work received little support from mainstream historians and archeologists at the time, and even less today. Other nineteenth-century writers, such as Horsford's friend Thomas Gold Appleton, in his ''A Sheaf of Papers'' (1875), and George Perkins Marsh, in his ''The Goths in New England'', seized upon such false notions of Vikings, Viking history also to promote the superiority of white people (as well as to oppose the Catholic Church). Such misuse of Viking history and imagery reemerged in the twentieth century among some groups promoting white supremacy.

Vinland Map

During the mid-1960's Yale University announced the acquisition of a map purportedly drawn around 1440 that showedVinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland ( non, Vínland ᚠᛁᚾᛚᛅᚾᛏ) was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John ...

and a legend concerning Norse voyages to the region. However certain experts doubted the authenticity of the map, based on linguistic and cartographic inconsistencies. Chemical analysis of the map's ink later shed further doubts on its authenticity. Scientific debate continued until in 2021 the university finally acknowledged that the Vinland Map is a forgery.

Misattributed archeological findings

Archeological findings in 2015 at Point Rosee, on the southwest coast of Newfoundland, were originally thought to reveal evidence of a turf wall and the roasting of bog iron ore, and therefore a possible 10th century Norse settlement in Canada. Findings from the 2016 excavation suggest the turf wall and the roasted bog iron ore discovered in 2015 were the result of natural processes. The possible settlement was initially discovered through satellite imagery in 2014, and archaeologists excavated the area in 2015 and 2016. Birgitta Wallace, Birgitta Linderoth Wallace, one of the leading experts of Norse archaeology in North America and an expert on the Norse site at L'Anse aux Meadows, is unsure of the identification of Point Rosee as a Norse site. Archaeologist Karen Milek was a member of the 2016 Point Rosee excavation and is a Norse expert. She also expressed doubt that Point Rosee was a Norse site as there are no good landing sites for their boats and there are steep cliffs between the shoreline and the excavation site. In their 8 November 2017, report Sarah Parcak and Gregory Mumford, co-directors of the excavation, wrote that they "found no evidence whatsoever for either a Norse presence or human activity at Point Rosee prior to the historic period" and that "none of the team members, including the Norse specialists, deemed this area as having any traces of human activity."Duration of Norse contact

Settlements in continental North America aimed to exploit natural resources such as furs and in particular lumber, which was in short supply in Greenland. It is unclear why the short-term settlements did not become permanent, though it was likely in part because of hostile relations with the indigenous peoples, referred to as the ''Skræling

''Skræling'' (Old Norse and Icelandic: ''skrælingi'', plural ''skrælingjar'') is the name the Norse Greenlanders used for the peoples they encountered in North America (Canada and Greenland). In surviving sources, it is first applied to the ...

'' by the Norse. Nevertheless, it appears that sporadic voyages to Markland for forages, timber, and trade with the locals could have lasted as long as 400 years.

James Watson Curran writes:From 985 to 1410, Greenland was in touch with the world. Then silence. In 1492 the Holy See, Vatican noted that no news of that country "at the end of the world" had been received for 80 years, and the bishopric of the colony was offered to a certain ecclesiastic if he would go and "restore Christianity" there. He didn't go.

See also

*Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact theories *Norwegian penning *History of Greenland *History of Nunavut *History of Newfoundland * Danish colonization of the Americas, Danish-Norwegian colonization of the Americas *Leif Erikson DayReferences

External links

L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada website

Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage website

Freda Harold Research Papers

at Dartmouth College Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Norse Colonization Of The Americas Norse colonization of North America, Populated places established in the 10th century 10th century in North America 15th century in North America