Noel Pemberton Billing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Noel Pemberton Billing (31 January 1881 – 11 November 1948), sometimes known as Noel Pemberton-Billing, was a British aviator, inventor, publisher and

A further musical invention, the "Duophone" unbreakable record, appeared in 1925, but was discontinued in 1930 as its material rapidly wore out needles and most Duophone recordings were made by the obsolete acoustical process.

In 1936, Billing designed the miniature

A further musical invention, the "Duophone" unbreakable record, appeared in 1925, but was discontinued in 1930 as its material rapidly wore out needles and most Duophone recordings were made by the obsolete acoustical process.

In 1936, Billing designed the miniature

PortCities Southampton: Noel Pemberton-Billing

Airminded: Noel Pemberton-Billing

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Billing, Noel Pemberton 1881 births 1948 deaths People from Hampstead English aviators Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Royal Navy officers Royal Naval Air Service personnel of World War I British military personnel of the Second Boer War UK MPs 1910–1918 UK MPs 1918–1922 Populism Far-right politics in England British anti-communists British conspiracy theorists Independent British political candidates Independent members of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom 20th-century English businesspeople

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for Hertford

Hertford ( ) is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. The parish had a population of 26,783 at the 2011 census.

The town grew around a ford on the River Lea, ne ...

. He founded the firm that became Supermarine

Supermarine was a British aircraft manufacturer that is most famous for producing the Supermarine Spitfire, Spitfire fighter plane during World War II as well as a range of seaplanes and flying boats, and a series of Jet engine, jet-powered figh ...

and promoted air power

Airpower or air power consists of the application of military aviation, military strategy and strategic theory to the realm of aerial warfare and close air support. Airpower began in the advent of powered flight early in the 20th century. Airpo ...

, and held a strong antipathy towards the Royal Aircraft Factory

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

and its products. He was noted during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

for his populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

views and for a sensational libel trial.

Early life and education

Noel Billing was born atHampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, and extends from Watling Street, the A5 road (Roman Watling Street) to Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland. The area forms the northwest part of the Lon ...

,north London

North London is the northern part of London, England, north of the River Thames. It extends from Clerkenwell and Finsbury, on the edge of the City of London financial district, to Greater London's boundary with Hertfordshire.

The term ''nort ...

, youngest son of Charles Eardley Billing, a Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

iron-founder, and Annie Emilia, née Claridge. He was educated at the high school at Hampstead, at Cumming's College, outside Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

, at Westcliff College, Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to t ...

, and at Craven College, Highgate

Highgate ( ) is a suburban area of north London at the northeastern corner of Hampstead Heath, north-northwest of Charing Cross.

Highgate is one of the most expensive London suburbs in which to live. It has two active conservation organisati ...

.

Career

Billing ran away from home at the age of 13 and travelled to South Africa. After trying a number of occupations, he joined themounted police

Mounted police are police who patrol on horseback or camelback. Their day-to-day function is typically picturesque or ceremonial, but they are also employed in crowd control because of their mobile mass and height advantage and increasingly in the ...

and became a boxer. He was also an actor when he took the extra name Pemberton. He fought in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

, and was at the Relief of Ladysmith

When the Second Boer War broke out on 11 October 1899, the Boers had a numeric superiority within Southern Africa. They quickly invaded the British territory and laid siege to Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking. Britain meanwhile transported th ...

, but was later invalided out.

Billing returned to Britain in 1903 and used his savings to open a garage in Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames (hyphenated until 1965, colloquially known as Kingston) is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, southwest London, England. It is situated on the River Thames and southwest of Charing Cross. It is notable as ...

. This was successful, but he became more interested in aviation, which was then in its infancy. An attempt to open an aerodrome

An aerodrome (Commonwealth English) or airdrome (American English) is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for publ ...

in Essex failed, so he started a short-lived career in property, while studying to become a lawyer. He passed his exams, but instead moved into selling steam yacht

A steam yacht is a class of luxury or commercial yacht with primary or secondary steam propulsion in addition to the sails usually carried by yachts.

Origin of the name

The English steamboat entrepreneur George Dodd (1783–1827) used the term ...

s. Convinced of the potential of powered aviation, he founded a flying field with extensive facilities on reclaimed marshland at Fambridge in Essex in 1909, but this ambitious venture did not prosper, British aviation activity becoming centred at Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields, ...

. In 1913, he bet Frederick Handley Page

Sir Frederick Handley Page, CBE, FRAeS (15 November 1885 – 21 April 1962) was an English industrialist who was a pioneer in the aircraft industry and became known as the father of the heavy bomber.

His company Handley Page Limited was ...

that he could earn his pilot's licence

Pilot licensing or certification refers to permits for operating aircraft. Flight crew licences are regulated by ICAO Annex 1 and issued by the civil aviation authority of each country. CAA’s have to establish that the holder has met a specifi ...

within 24 hours of first sitting in an aircraft. He won his bet, gaining licence number 683 and £500, equivalent to more than £28,000 in 2010, which he used to found an aircraft business, Pemberton-Billing Ltd, with Hubert Scott-Paine

Hubert Scott-Paine (11 March 1891 – 14 April 1954) was a British aircraft and boat designer, record-breaking power boat racer, entrepreneur, inventor, and sponsor of the winning entry in the 1922 Schneider Trophy.

Early life

Hubert Paine was ...

as works manager, in 1913. Billing registered the telegraphic address

A telegraphic address or cable address was a unique identifier code for a recipient of telegraph messages. Operators of telegraph services regulated the use of telegraphic addresses to prevent duplication. Rather like a uniform resource locator ( ...

''Supermarine, Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

'' for the company, which soon acquired premises at Oakbank Wharf in Woolston, Southampton

Woolston is a suburb of Southampton, Hampshire, located on the eastern bank of the River Itchen. It is bounded by the River Itchen, Sholing, Peartree Green, Itchen and Weston.

The area has a strong maritime and aviation history. The former ...

, and started construction of his flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

designs. Financial difficulties soon set in, but the onset of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

revived the fortunes of the business.

In 1914, Billing joined the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

and in October was granted a temporary commission as a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

. He was involved in the air raid on Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

sheds near Lake Constance

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three Body of water, bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, ca ...

made in November 1914. He was able to sell his share in the aviation firm to Scott-Paine in early 1916, who renamed the firm Supermarine Aviation Works Limited after the company's telegraphic address.McKinstry, Leo. ''Spitfire: Portrait of a Legend'', London, UK. John Murray Publisher. 435pp.

Politics

Parliament

As a man of means, Billing contested the Mile End by-election in 1916 as anindependent candidate

An independent or non-partisan politician is a politician not affiliated with any political party or bureaucratic association. There are numerous reasons why someone may stand for office as an independent.

Some politicians have political views th ...

, but was not successful. He then contested and won the March 1916 by-election in Hertford.

In parliament, Billing consistently advocated the creation of an air force, retaliation against German air raids, that action be taken against war profiteering

A war profiteer is any person or organization that derives profit (economics), profit from warfare or by selling weapons and other goods to parties at war. The term typically carries strong negative connotations. General profiteering (business), ...

and that action be taken to lessen the influence of Germans in Britain. In asking awkward questions of the government he was usually supported by Arthur Lynch.

In 1917, after an altercation in parliament, Noel Pemberton Billing offered Martin Archer-Shee

Sir Martin Archer-Shee CMG DSO (5 May 1873 – 6 January 1935) was a British army officer and Conservative Party politician.

Background

He was the son of Martin Archer-Shee (1846-1913) and his wife Elizabeth Edith Dennistoun (1851-1890) ( n� ...

MP a duel by boxing in public for charity, but Archer-Shee declined.

Following a disagreement over parliamentary procedure

Parliamentary procedure is the accepted rules, ethics, and customs governing meetings of an assembly or organization. Its object is to allow orderly deliberation upon questions of interest to the organization and thus to arrive at the sense or t ...

and with Billing refusing to sit down while "Germans are running about this country" Billing was ejected from the House of Commons and suspended as an MP on 1 July 1918. Because Billing refused to leave the chamber even after the House had voted to suspend him, and the Serjeant at Arms

A serjeant-at-arms, or sergeant-at-arms, is an officer appointed by a deliberative body, usually a legislature, to keep order during its meetings. The word "serjeant" is derived from the Latin ''serviens'', which means "servant". Historically, s ...

had then asked him to leave, he was automatically suspended for the rest of that parliamentary session

A legislative session is the period of time in which a legislature, in both parliamentary and presidential systems, is convened for purpose of lawmaking, usually being one of two or more smaller divisions of the entire time between two elections. ...

, rather than the usual five days.

At the 1918 general election, he was one of the few candidates to beat a Coalition Coupon

The Coalition Coupon was a letter sent to parliamentary candidates at the 1918 United Kingdom general election, endorsing them as official representatives of the Coalition Government. The 1918 election took place in the heady atmosphere of victory ...

candidate and he doubled his majority.

He resigned his seat in 1921 by accepting the Stewardship of the Manor of Northstead, citing that the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

had been rendered "unwholesome and unfair" by Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

"at the instigation of a camarilla

A camarilla is a group of courtiers or favourites who surround a king or ruler. Usually, they do not hold any office or have any official authority at the royal court but influence their ruler behind the scenes. Consequently, they also escape havi ...

of International financiers".

Advocacy of air power

During the First World War, he was notable for his support of air power, constantly accusing the government of neglecting the issue and advocating the creation of a separate air force, unattached to either theBritish Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

or the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. During the so-called " Fokker scourge" of late 1915 and early 1916, he became particularly vocal against the Royal Aircraft Factory

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

and its products, raising the question in typically exaggerated terms once he entered parliament. His prejudice against the Factory and its products persisted, and was very influential. He called for air raids against German cities. In 1917, he published ''Air War and How to Wage it'', which emphasised the future role of raids on cities and the need to develop protective measures. His own eccentric quadraplane design for a home defence fighter, the heavily armed and searchlight-equipped "Supermarine Nighthawk

The Supermarine P.B.31E Nighthawk was a British aircraft of the First World War and the first project of the Pemberton-Billing operation after it became Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd. It was an anti-Zeppelin night fighter operated by a crew of ...

", was built in prototype but had insufficient performance to be of any use against Zeppelins.

Publishing and libel trial

In late 1916, Billing founded and edited a weekly journal, The ''Imperialist''. The journal supported his parliamentary campaigns, also advocating equal voting rights for men and women andelectoral reform

Electoral reform is a change in electoral systems which alters how public desires are expressed in election results. That can include reforms of:

* Voting systems, such as proportional representation, a two-round system (runoff voting), instant-ru ...

. The journal was renamed ''Vigilante'' in 1918 to reflect his campaign for a Vigilance Committee.

In 1918, Captain Harold Sherwood Spencer

Harold Sherwood Spencer (April 12, 1890 – August 26, 1957), also known as Howland Spencer, was an American writer and anti-homosexuality and antisemitic activist during and after World War I. He was closely associated with Noel Pemberton Billi ...

became assistant editor and the journal was increasingly left in Spencer's hands. John Henry Clarke

John Henry Clarke (1853 – 24 November 1931) was an English classical homeopath. He was also, arguably, the highest profile anti-Semite of his era in Great Britain. He led The Britons, an anti-Semitic organisation. Educated at the University of ...

and Henry Hamilton Beamish

Henry Hamilton Beamish (2 June 1873 – 27 March 1948) was a leading United Kingdom, British Antisemitism, antisemitic journalist and the founder of The Britons (organisation), The Britons in 1919, the first organisation set up in Britain for the ...

began to write for ''Vigilante'', and promoted anti-semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

, claiming "the British war effort was being undermined by the "hidden hand" of German sympathisers and German Jews operating in Britain". The journal included attacks on "Jews, German music, Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

, Fabianism

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The Fab ...

, Aliens

Alien primarily refers to:

* Alien (law), a person in a country who is not a national of that country

** Enemy alien, the above in times of war

* Extraterrestrial life, life which does not originate from Earth

** Specifically, intelligent extrate ...

, Financiers, Internationalism

Internationalism may refer to:

* Cosmopolitanism, the view that all human ethnic groups belong to a single community based on a shared morality as opposed to communitarianism, patriotism and nationalism

* International Style, a major architectur ...

, and the Brotherhood of Man".Gay Wachman, ''Lesbian Empire: Radical Crosswriting in the Twenties'', Rutgers University Press

Rutgers University Press (RUP) is a nonprofit academic publishing house, operating in New Brunswick, New Jersey under the auspices of Rutgers University.

History

Rutgers University Press, a nonprofit academic publishing house operating in New B ...

, 2001. (p. 15) There is no evidence that Billing himself was antisemitic, however.

The journal's most famous articles were largely written by Spencer, but under Billing's name, in which it was claimed that the Germans were blackmailing "47,000 highly placed British perverts" to "propagate evils which all decent men thought had perished in Sodom and Lesbia

Lesbia was the literary pseudonym used by the Roman poet Gaius Valerius Catullus ( 82–52 BC) to refer to his lover. Lesbia is traditionally identified with Clodia, the wife of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer and sister of Publius Clodius Pulc ...

". The names were said to be inscribed in the "Berlin Black Book" of the Mbret of Albania. The contents of this book revealed that the Germans planned on "exterminating the manhood of Britain" by luring men into homosexuality and paedophilia

Pedophilia ( alternatively spelt paedophilia) is a psychiatric disorder in which an adult or older adolescent experiences a primary or exclusive sexual attraction to prepubescent children. Although girls typically begin the process of puberty ...

. "Even to loiter in the streets was not immune. Meretricious agents of the Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

were stationed at such places as Marble Arch

The Marble Arch is a 19th-century white marble-faced triumphal arch in London, England. The structure was designed by John Nash (architect), John Nash in 1827 to be the state entrance to the cour d'honneur of Buckingham Palace; it stood near th ...

and Hyde Park Corner

Hyde Park Corner is between Knightsbridge, Belgravia and Mayfair in London, England. It primarily refers to its major road junction at the southeastern corner of Hyde Park, that was designed by Decimus Burton. Six streets converge at the junc ...

. In this black book of sin details were given of the unnatural defloration of children ... wives of men in supreme positions were entangled. In Lesbian ecstasy the most sacred secrets of the state were threatened." He publicly attacked Margot Asquith

Emma Margaret Asquith, Countess of Oxford and Asquith (' Tennant; 2 February 1864 – 28 July 1945), known as Margot Asquith, was a British socialite, author. She was married to H. H. Asquith, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1894 ...

, the wife of the prime minister, hinting that she was caught up in this. He also targeted members of the circle around Robbie Ross

Robert Baldwin Ross (25 May 18695 October 1918) was a Canadian-British journalist, art critic and art dealer, best known for his relationship with Oscar Wilde, to whom he was a devoted friend and literary executor. A grandson of the Canadian ...

, the literary executor of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, who supported and introduced homosexual poets and writers.

He published an article, "The Cult of the Clitoris", which implied that the actress Maud Allan

Maud Allan (born as either Beulah Maude Durrant or Ulah Maud Alma Durrant;Birthname given as Ulah Maud Alma DurrantMcConnell, Virginia A. ''Sympathy for the Devil: The Emmanuel Baptist Murders of Old San Francisco'', University of Nebraska Pr ...

, then appearing in a private production of ''Salome

Salome (; he, שְלוֹמִית, Shlomit, related to , "peace"; el, Σαλώμη), also known as Salome III, was a Jewish princess, the daughter of Herod II, son of Herod the Great, and princess Herodias, granddaughter of Herod the Great, an ...

'' organised by Ross, was a lesbian associate of the conspirators. This led to a sensational libel case, at which Billing represented himself and won. Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), also known as Bosie Douglas, was an English poet and journalist, and a lover of Oscar Wilde. At Oxford he edited an undergraduate journal, ''The Spirit Lamp'', that carried a homoer ...

, a former lover of Oscar Wilde, testified in Billing's favour, as did Billing's mistress Eileen Villiers-Stuart. Villiers-Stuart claimed to have seen the "Black Book" and even asserted in court that the judge, Charles Darling, was in the book.

Billing's victory in this case created significant popular publicity. He later indicated he had never believed such a book existed, but that the whole matter had been "to frighten off those in prominent positions whose sexual tastes could have led to them being blackmailed

Blackmail is an act of coercion using the threat of revealing or publicizing either substantially true or false information about a person or people unless certain demands are met. It is often damaging information, and it may be revealed to fa ...

by German agents". Michael Kettle in his book, ''Salome's Last Veil: The Libel Case of the Century'', claimed that the Maud Allan libel case was part of a plot by generals to stop Lloyd George from making an early peace with Germany.

Vigilance Committee

While air power was his main overarching concern Pemberton Billing's primary political campaign was for the establishment of a committee of nineIndependent politician

An independent or non-partisan politician is a politician not affiliated with any political party or bureaucratic association. There are numerous reasons why someone may stand for office as an independent.

Some politicians have political views th ...

s who would watch over the government in the House of Commons. He was highly critical of party politics

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or pol ...

believing it was a "disease" which made all governments "corrupt". The name was explicitly in reference to the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance

The San Francisco Committee of Vigilance was a vigilante group formed in 1851. The catalyst for its formation was the criminality of the Sydney Ducks gang. It was revived in 1856 in response to rampant crime and corruption in the municipal governm ...

.

He then created a Vigilance Society to stand in the elections. The society was disbanded in 1919 as Billing became disillusioned with Spencer, Beamish and Clarke.

Inter-war years

Following theRussian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

, Billing began to express strong anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

viewpoints, and, in 1919, he supported British military intervention against the Bolsheviks in Russia.

After the war, he suffered increasingly from health problems, which contributed to his temporary retirement from politics in 1921. He dramatically resigned his seat in parliament, urging his constituents not to vote in the consequent by-election.Maurice Cowling, ''The Impact of Labour 1920–1924: The Beginning of Modern British Politics'', Cambridge University Press, 2005, p.459 However, he continued to remain active writing literary works and producing films. In 1927, Billing wrote a play, ''High Treason'', inspired by Fritz Lang

Friedrich Christian Anton Lang (; December 5, 1890 – August 2, 1976), known as Fritz Lang, was an Austrian film director, screenwriter, and producer who worked in Germany and later the United States.Obituary ''Variety'', August 4, 1976, p. 6 ...

's film ''Metropolis

A metropolis () is a large city or conurbation which is a significant economic, political, and cultural center for a country or region, and an important hub for regional or international connections, commerce, and communications.

A big c ...

''. It was a sci-fi drama about pacifism set in a future 1940 (later changed to 1950), when a "United States of Europe" comes into conflict with the "Empire of the Atlantic States". In 1929, Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (11 November 1887 – 28 August 1967) was one of the most prolific film directors in British history. He directed nearly 200 films between 1913 and 1957. During the silent film era he directed as many as twenty films per year. He a ...

made a film of the play, using the same title. It was released in two versions, one silent and the other an early "talkie", but neither proved successful.

He stood again for Hertford in the 1929 general election, coming second. In 1938, he registered his protest against Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

's Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

in a booklet.

Australia

Billing emigrated to Australia after the First World War. It was in Australia that he patented a recording system intended to produce laterally-cut disc records with ten times the capacity of existing systems. Billing's "World Record Controller" fitted onto a standard spring-wound gramophone, using a progressive gearing system to initially slow the turntable speed from 78 rpm to 33 rpm and then gradually increase rotational speed of the record as it played, so that the linear speed at which the recorded groove passed the needle remained constant. That allowed over ten minutes playing time per 12-inch side of the records, but the high cost of the long-playing discs (10 shillings apiece), the fact that the speed varied, and the complexity of the playback attachment, prevented popular acceptance. In 1923, Billing set up a disc recording plant under the name World Record (Australia) Limited. The plant was in Bay StreetBrighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

, a suburb of Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, from where he produced his 78 rpm to 33 rpm discs. The plant was also the base for radio station 3PB, which he established in August 1925 for the purpose of broadcasting the company’s recordings. It was a limited "manufacturers' licence", a type which was only available during the first few years of wireless broadcasting in Australia. 3PB was only on the air for four months.

The first recording made by World Record (Australia) was released in July 1925, and featured Bert Ralton’s Havana Band, then performing at the Esplanade Hotel in the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda.

Other inventions

A further musical invention, the "Duophone" unbreakable record, appeared in 1925, but was discontinued in 1930 as its material rapidly wore out needles and most Duophone recordings were made by the obsolete acoustical process.

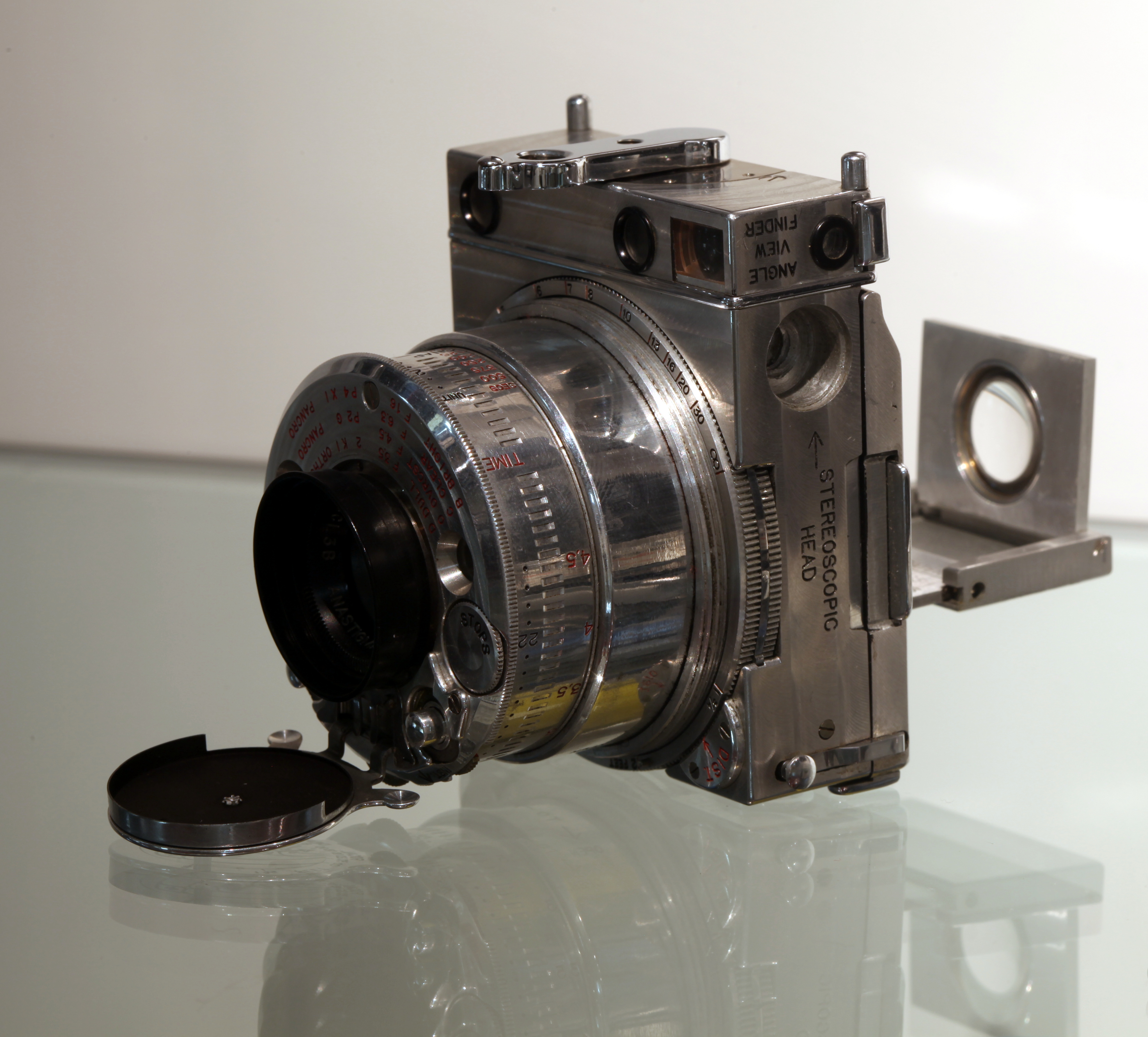

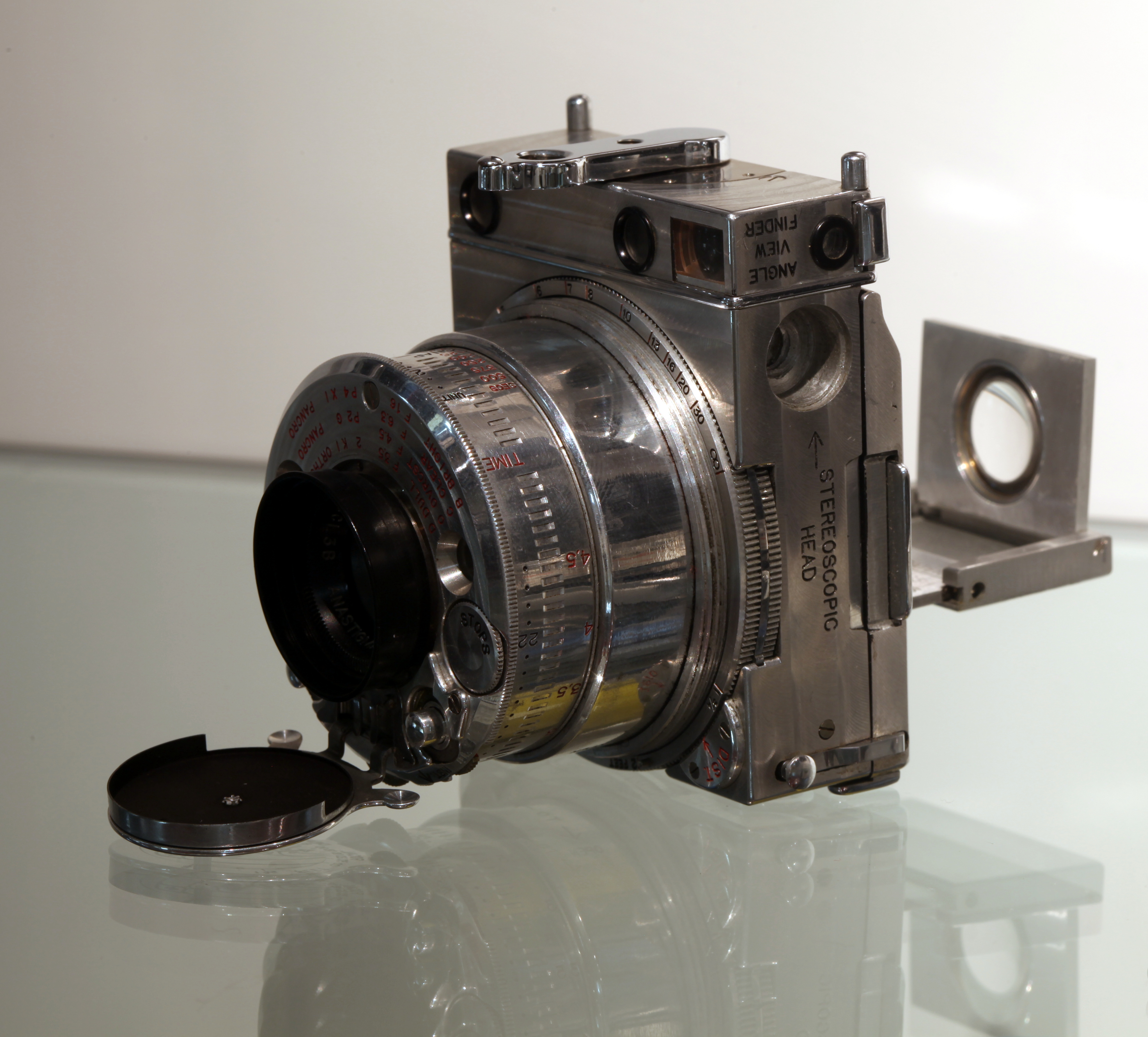

In 1936, Billing designed the miniature

A further musical invention, the "Duophone" unbreakable record, appeared in 1925, but was discontinued in 1930 as its material rapidly wore out needles and most Duophone recordings were made by the obsolete acoustical process.

In 1936, Billing designed the miniature LeCoultre

Manufacture Jaeger-LeCoultre SA, or simply Jaeger-LeCoultre (), is a Swiss luxury watch and clock manufacturer founded by Antoine LeCoultre in 1833 and is based in Le Sentier, Switzerland. Since 2000, the company has been a fully owned subsidiary ...

Compass camera. In 1948, he devised the "Phantom" camera to be used by spies. It never entered production, but its rarity led one to sell for £120,000, a record price for any camera, in 2001.

Shortly before the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Billing claimed to have invented an uncrewed flying bomb

A flying bomb is a manned or unmanned aerial vehicle or aircraft carrying a large explosive warhead, a precursor to contemporary cruise missiles. In contrast to a bomber aircraft, which is intended to release bombs and then return to its base for ...

, but the design was not pursued.

Second World War

In 1941, Billing attempted to return to politics, seeking to replicate his success during the First World War as a critic of the conduct of the war. He advocated the defeat of Germany by bombing alone, and the defence of Britain by a system of spaced light-beams directed upwards, which would confuse enemy bombers. Billing also proposed a post-war reform of theBritish constitution

The constitution of the United Kingdom or British constitution comprises the written and unwritten arrangements that establish the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a political body. Unlike in most countries, no attempt ...

, arguing that general elections should be abolished in favour of a rolling programme of by-elections and that a new second chamber

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single grou ...

should be created, appointed from representatives of trades and professions. He also argued that there should be a separate "Women's parliament" dedicated to "domestic" matters. He stood in four by-elections, most notably in Hornsey in 1941, but he was unable to win a seat in parliament at any of them.

Personal life

In 1903, Billing married Lilian Maud (died 1923), daughter of Theodore Henry Schweitzer, ofBristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

; they had no children. Billing died on 11 November 1948 at the age of 67, aboard his motor-yacht, ''Commodore'', at The Quay, Burnham-on-Crouch

Burnham-on-Crouch is a town and civil parish in the Maldon District of Essex in the East of England. It lies on the north bank of the River Crouch. It is one of Britain's leading places for yachting.

The civil parish extends east of the town t ...

, Essex.

Representations in literature

The novelistPat Barker

Patricia Mary W. Barker, (née Drake; born 8 May 1943) is an English writer and novelist. She has won many awards for her fiction, which centres on themes of memory, trauma, survival and recovery. Her work is described as direct, blunt and pl ...

's award-winning First World War trilogy – ''Regeneration

Regeneration may refer to:

Science and technology

* Regeneration (biology), the ability to recreate lost or damaged cells, tissues, organs and limbs

* Regeneration (ecology), the ability of ecosystems to regenerate biomass, using photosynthesis

...

'', ''The Eye in the Door

''The Eye in the Door'' is a novel by Pat Barker, first published in 1993, and forming the second part of the ''Regeneration'' trilogy.

''The Eye in the Door'' is set in London, beginning in mid-April 1918, and continues the interwoven storie ...

'' and ''The Ghost Road

''The Ghost Road'' is a war novel by Pat Barker, first published in 1995 and winner of the Booker Prize. It is the third volume of a trilogy that follows the fortunes of shell-shocked British army officers towards the end of the First World War ...

'' – was set against the backdrop of Billing's libel case, with several characters mentioning his ominous black book. The middle novel, in particular, deals with the psychiatric treatment of soldiers torn between patriotism and pacifism, and between homosexuality and heterosexuality.

References

Further reading

*Thomas Grant, ''Court Number One: The Old Bailey Trials that Defined Modern Britain,'' London UK, 2019 *James Hayward, ''Myths and Legends of the First World War''. Stroud: Sutton, 2002. *Philip Hoare, ''Wilde's Last Stand: Scandal, Decadence and Conspiracy During the Great War'', Duckworth Overlook, London and New York, 1997, 2nd ed., 2011. (concerning Pemberton Billing's trial for criminal libel). *Michael Kettle "Salome's Last Veil: The Libel Case of the Century" 1977 *Noel Pemberton-Billing ''Air War: How to Wage It, with some suggestions for the defence of the great cities'', Portsmouth UK,Gale & Polden

Gale and Polden was a British printer and publisher. Founded in Brompton, near Chatham, Kent in 1868, the business subsequently moved to Aldershot, where they were based until closure in November 1981 after the company had been bought by media m ...

, 1916, 74pp

*Barry Powers, ''Strategy Without Slide-Rule: British Air Strategy 1914–1939'', London UK, Croom Helm, 1976

*Barbara Stoney, ''Twentieth Century Maverick''. East Grinstead: Manor House Books, 2004.

*

External links

PortCities Southampton: Noel Pemberton-Billing

Airminded: Noel Pemberton-Billing

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Billing, Noel Pemberton 1881 births 1948 deaths People from Hampstead English aviators Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Royal Navy officers Royal Naval Air Service personnel of World War I British military personnel of the Second Boer War UK MPs 1910–1918 UK MPs 1918–1922 Populism Far-right politics in England British anti-communists British conspiracy theorists Independent British political candidates Independent members of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom 20th-century English businesspeople