Ninevites on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nineveh (; akk, ;

''A Dictionary of Archaeology''

John Wiley & Sons, 2002 p. 427 Also, for the Upper Mesopotamian region, the ''Early Jezirah'' chronology has been developed by archaeologists. According to this regional chronology, 'Ninevite 5' is equivalent to the Early Jezirah I–II period. Ninevite 5 was preceded by the Late Uruk period. Ninevite 5 pottery is roughly contemporary to the

File:Painted Jar - Ninevite 5.jpg, Painted jar – Ninevite 5

File:Painted bowl - Uruk-Nineveh 5 transition.jpg, Painted bowl – Uruk-Nineveh 5 transition

File:Jamdat Nasr Period pottery - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago - DSC06949.JPG, Jemdet Nasr ware

File:Vaso cerámico del periodo protoelamita - MARQ 01.jpg, Proto-Elamite ware 3100 BC

File:Saxsı küp, Təpəyatağı.JPG, Pottery jar, Tepeyatagi, Khudat district, Kura-Araxtes culture

The greatness of Nineveh was short-lived. In around 627 BC, after the death of its last great king

The greatness of Nineveh was short-lived. In around 627 BC, after the death of its last great king

In 1847 the young British diplomat Austen Henry Layard explored the ruins. Layard did not use modern archaeological methods; his stated goal was "to obtain the largest possible number of well preserved objects of art at the least possible outlay of time and money". In the Kuyunjiq mound, Layard rediscovered in 1849 the lost palace of Sennacherib with its 71 rooms and colossal bas-reliefs. He also unearthed the palace and famous

In 1847 the young British diplomat Austen Henry Layard explored the ruins. Layard did not use modern archaeological methods; his stated goal was "to obtain the largest possible number of well preserved objects of art at the least possible outlay of time and money". In the Kuyunjiq mound, Layard rediscovered in 1849 the lost palace of Sennacherib with its 71 rooms and colossal bas-reliefs. He also unearthed the palace and famous

SBAH

led by Nicolò Marchetti, began (with four campaigns having taken place thus far between 2019 and 2022) a long-term project aiming at the excavation, conservation and public presentation of the lower town of Nineveh. Work was carried out in eighteen excavation areas, from the Adad Gate – now completely repaired (after removing hundreds of tons of debris from ISIL's destructions), explored and protected with a new roof – deep into the Nebi Yunus town. In a few areas a thick later stratigraphy was encountered, but the late 7th century BC stratum was reached everywhere (actually in two areas in the pre-Sennacherib lower town the excavations already exposed older strata, up to the 11th century BC until now, aiming in the future at exploring the first settlement therein). The site is greatly endangered with dumping of debris, illegal settlements and quarrying as the main threats.

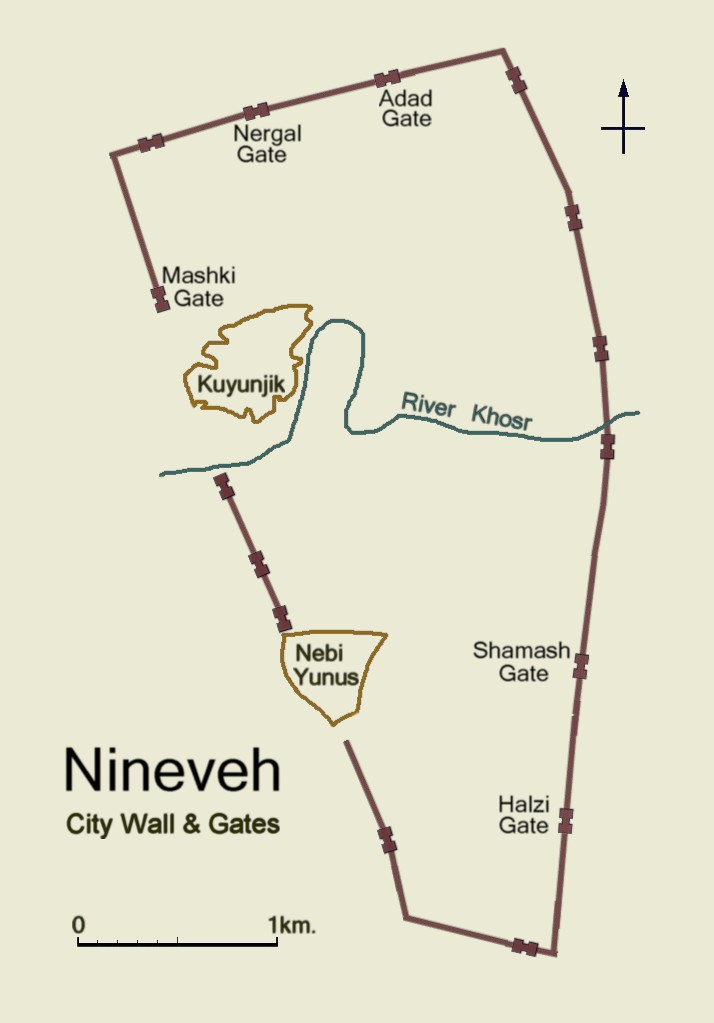

Today, Nineveh's location is marked by two large mounds, Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell ''Nabī Yūnus'' "Prophet Jonah", and the remains of the city walls (about in circumference). The Neo-Assyrian levels of Kuyunjiq have been extensively explored. The other mound, ''Nabī Yūnus'', has not been as extensively explored because there was an Arab Muslim shrine dedicated to that prophet on the site. On July 24, 2014, the Islamic State destroyed the shrine as part of a Destruction of cultural heritage by the Islamic State, campaign to destroy religious sanctuaries it deemed "un-Islamic", but also to loot that site through tunneling.

The ruin mound of Kuyunjiq rises about above the surrounding plain of the ancient city. It is quite broad, measuring about . Its upper layers have been extensively excavated, and several Neo-Assyrian palaces and temples have been found there. A deep sounding by Max Mallowan revealed evidence of habitation as early as the 6th millennium BC. Today, there is little evidence of these old excavations other than weathered pits and earth piles. In 1990, the only Assyrian remains visible were those of the entry court and the first few chambers of the Palace of Sennacherib. Since that time, the palace chambers have received significant damage by looters. Portions of relief sculptures that were in the palace chambers in 1990 were seen on the antiquities market by 1996. Photographs of the chambers made in 2003 show that many of the fine relief sculptures there have been reduced to piles of rubble.

Today, Nineveh's location is marked by two large mounds, Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell ''Nabī Yūnus'' "Prophet Jonah", and the remains of the city walls (about in circumference). The Neo-Assyrian levels of Kuyunjiq have been extensively explored. The other mound, ''Nabī Yūnus'', has not been as extensively explored because there was an Arab Muslim shrine dedicated to that prophet on the site. On July 24, 2014, the Islamic State destroyed the shrine as part of a Destruction of cultural heritage by the Islamic State, campaign to destroy religious sanctuaries it deemed "un-Islamic", but also to loot that site through tunneling.

The ruin mound of Kuyunjiq rises about above the surrounding plain of the ancient city. It is quite broad, measuring about . Its upper layers have been extensively excavated, and several Neo-Assyrian palaces and temples have been found there. A deep sounding by Max Mallowan revealed evidence of habitation as early as the 6th millennium BC. Today, there is little evidence of these old excavations other than weathered pits and earth piles. In 1990, the only Assyrian remains visible were those of the entry court and the first few chambers of the Palace of Sennacherib. Since that time, the palace chambers have received significant damage by looters. Portions of relief sculptures that were in the palace chambers in 1990 were seen on the antiquities market by 1996. Photographs of the chambers made in 2003 show that many of the fine relief sculptures there have been reduced to piles of rubble.

Tell Nebi Yunus is located about south of Kuyunjiq and is the secondary ruin mound at Nineveh. On the basis of texts of Sennacherib, the site has traditionally been identified as the "armory" of Nineveh, and a gate and pavements excavated by Iraqis in 1954 have been considered to be part of the "armory" complex. Excavations in 1990 revealed a monumental entryway consisting of a number of large inscribed Megalithic architectural elements#Orthostat, orthostats and "bull-man" sculptures, some apparently unfinished.

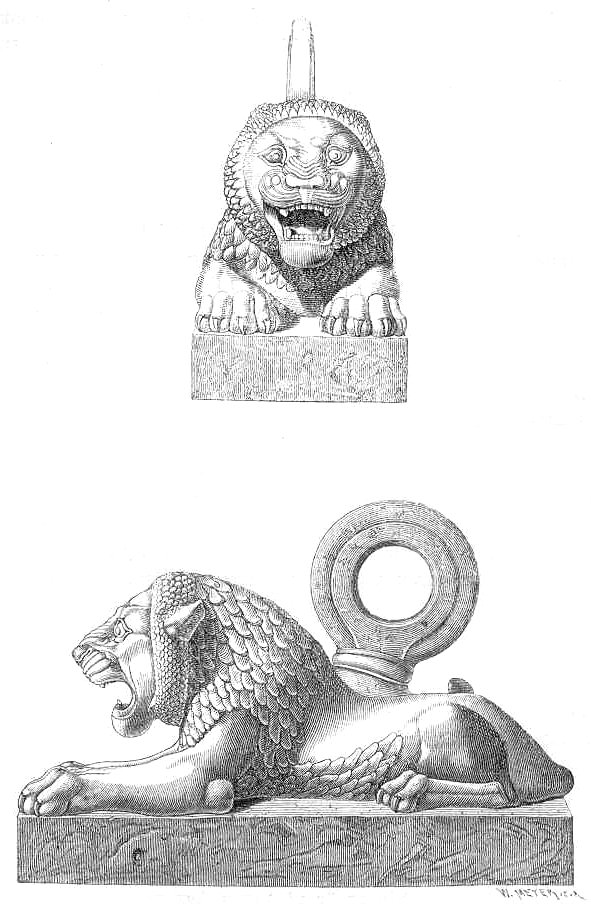

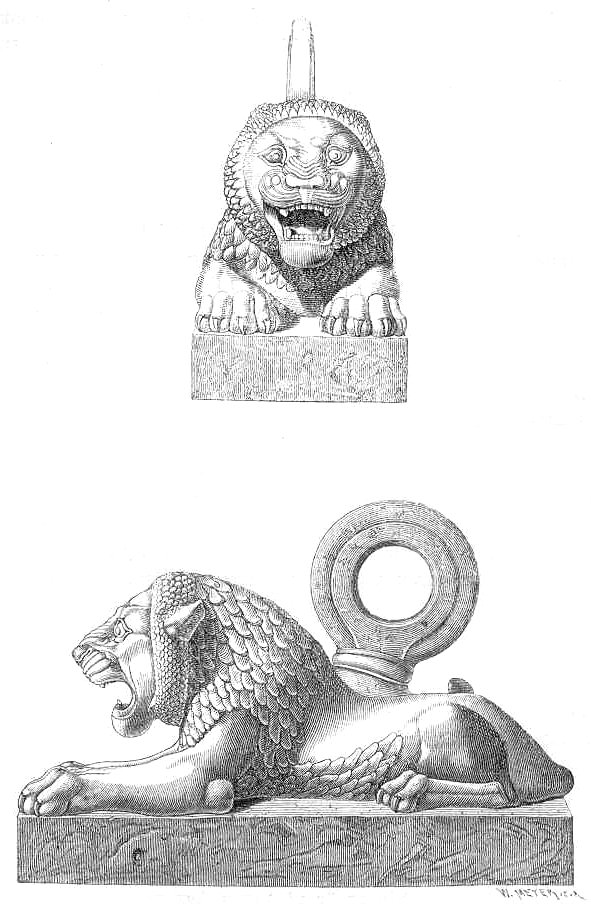

Following the Battle of Mosul (2016–2017), liberation of Mosul, the tunnels under Tell Nebi Yunus were explored in 2018, in which a 3000-year-old palace was discovered, including a pair of reliefs, each showing a row of women, along with reliefs of '' lamassu''.

Tell Nebi Yunus is located about south of Kuyunjiq and is the secondary ruin mound at Nineveh. On the basis of texts of Sennacherib, the site has traditionally been identified as the "armory" of Nineveh, and a gate and pavements excavated by Iraqis in 1954 have been considered to be part of the "armory" complex. Excavations in 1990 revealed a monumental entryway consisting of a number of large inscribed Megalithic architectural elements#Orthostat, orthostats and "bull-man" sculptures, some apparently unfinished.

Following the Battle of Mosul (2016–2017), liberation of Mosul, the tunnels under Tell Nebi Yunus were explored in 2018, in which a 3000-year-old palace was discovered, including a pair of reliefs, each showing a row of women, along with reliefs of '' lamassu''.

The ruins of Nineveh are surrounded by the remains of a massive stone and mudbrick wall dating from about 700 BC. About 12 km in length, the wall system consisted of an ashlar stone retaining wall about high surmounted by a mudbrick wall about high and thick. The stone retaining wall had projecting stone towers spaced about every . The stone wall and towers were topped by three-step merlons.

Five of the gateways have been explored to some extent by archaeologists:

* Mashki Gate (ماشکی دروازه): Translated "Gate of the Water Carriers" (''Mashki'' from Persian root word ''Mashk'', meaning waterskin), also ''Masqi Gate'' (Arabic: بوابة مسقي), it was perhaps used to take livestock to water from the Tigris which currently flows about to the west. It has been reconstructed in fortified mudbrick to the height of the top of the vaulted passageway. The Assyrian original may have been plastered and ornamented. It was bulldozed along with the Adad Gate during ISIL occupation. During the restoration project, seven alabaster carvings depicting Sennacherib reliefs were found at the gate in 2022.

* Nergal Gate: Named for the god

The ruins of Nineveh are surrounded by the remains of a massive stone and mudbrick wall dating from about 700 BC. About 12 km in length, the wall system consisted of an ashlar stone retaining wall about high surmounted by a mudbrick wall about high and thick. The stone retaining wall had projecting stone towers spaced about every . The stone wall and towers were topped by three-step merlons.

Five of the gateways have been explored to some extent by archaeologists:

* Mashki Gate (ماشکی دروازه): Translated "Gate of the Water Carriers" (''Mashki'' from Persian root word ''Mashk'', meaning waterskin), also ''Masqi Gate'' (Arabic: بوابة مسقي), it was perhaps used to take livestock to water from the Tigris which currently flows about to the west. It has been reconstructed in fortified mudbrick to the height of the top of the vaulted passageway. The Assyrian original may have been plastered and ornamented. It was bulldozed along with the Adad Gate during ISIL occupation. During the restoration project, seven alabaster carvings depicting Sennacherib reliefs were found at the gate in 2022.

* Nergal Gate: Named for the god

Atherstone's friend, the artist John Martin (painter), John Martin, created a painting of the same name inspired by the poem. The English poet John Masefield's well-known, fanciful 1903 poem ''Salt-Water Poems and Ballads#"Cargoes", Cargoes'' mentions Nineveh in its first line. Nineveh is also mentioned in Rudyard Kipling's 1897 poem ''Recessional (poem), Recessional'' and in Arthur O'Shaughnessy's 1873 poem ''Ode (poem), Ode''.

The 1962 Italian peplum (film genre), peplum film ''War Gods of Babylon'', is based on the sacking and fall of Nineveh by the combined rebel armies led by the Babylonians.

In ''Jonah: A VeggieTales Movie'', Jonah, much like his biblical counterpart, must travel to Nineveh due to God’s demands.

In the 1973 film ''The Exorcist (film), The Exorcist'', Father Lankester Merrin was on an archeological dig near Nineveh prior to returning to the United States and leading the exorcism of Reagan MacNiel.

Atherstone's friend, the artist John Martin (painter), John Martin, created a painting of the same name inspired by the poem. The English poet John Masefield's well-known, fanciful 1903 poem ''Salt-Water Poems and Ballads#"Cargoes", Cargoes'' mentions Nineveh in its first line. Nineveh is also mentioned in Rudyard Kipling's 1897 poem ''Recessional (poem), Recessional'' and in Arthur O'Shaughnessy's 1873 poem ''Ode (poem), Ode''.

The 1962 Italian peplum (film genre), peplum film ''War Gods of Babylon'', is based on the sacking and fall of Nineveh by the combined rebel armies led by the Babylonians.

In ''Jonah: A VeggieTales Movie'', Jonah, much like his biblical counterpart, must travel to Nineveh due to God’s demands.

In the 1973 film ''The Exorcist (film), The Exorcist'', Father Lankester Merrin was on an archeological dig near Nineveh prior to returning to the United States and leading the exorcism of Reagan MacNiel.

Joanne Farchakh-Bajjaly photos

of Nineveh taken in May 2003 showing damage from looters

John Malcolm Russell, "Stolen stones: the modern sack of Nineveh"

in ''Archaeology''; looting of sculptures in the 1990s

Nineveh page

at the British Museum's website. Includes photographs of items from their collection.

A teaching and research tool presenting a comprehensive picture of Nineveh within the history of archaeology in the Near East, including a searchable data repository for meaningful analysis of currently unlinked sets of data from different areas of the site and different episodes in the 160-year history of excavations

CyArk Digital Nineveh Archives

publicly accessible, free depository of the data from the previously linked UC Berkeley Nineveh Archives project, fully linked and georeferenced in a UC Berkeley/CyArk research partnership to develop the archive for open web use. Includes creative commons-licensed media items.

Photos of Nineveh, 1989–1990

: Babylonian Chronicle Concerning the Fall of Nineveh

Layard's Nineveh and its Remains- full text

{{Authority control Populated places established in the 6th millennium BC Populated places disestablished in the 13th century Ancient Assyrian cities Destroyed cities Archaeological sites in Iraq Assyria Assyrian geography Hebrew Bible cities Nineveh Governorate Former populated places in Iraq Ancient Mesopotamia Jonah Tells (archaeology) Hassuna culture Nimrod Book of Jubilees Old Assyrian Empire City-states

Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew (, or , ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite branch of Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Israel, roughly west of ...

: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern bank of the Tigris River and was the capital and largest city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, as well as the largest city in the world for several decades. Today, it is a common name for the half of Mosul that lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris, and the country's Nineveh Governorate

Nineveh Governorate ( ar, محافظة نينوى, syr, ܗܘܦܪܟܝܐ ܕܢܝܢܘܐ, Hoparkiya d’Ninwe, ckb, پارێزگای نەینەوا, Parêzgeha Neynewa), also known as Ninawa Governorate, is a governorate in northern Iraq. It has an ...

takes its name from it.

It was the largest city in the world for approximately fifty years until the year 612 BC when, after a bitter period of civil war in Assyria, it was sacked by a coalition of its former subject peoples including the Babylonians, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians. The city was never again a political or administrative centre, but by Late Antiquity it was the seat of a Christian bishop. It declined relative to Mosul during the Middle Ages and was mostly abandoned by the 13th century AD.

Its ruins lie across the river from the historical city center of Mosul, in Iraq's Nineveh Governorate

Nineveh Governorate ( ar, محافظة نينوى, syr, ܗܘܦܪܟܝܐ ܕܢܝܢܘܐ, Hoparkiya d’Ninwe, ckb, پارێزگای نەینەوا, Parêzgeha Neynewa), also known as Ninawa Governorate, is a governorate in northern Iraq. It has an ...

. The two main tells, or mound-ruins, within the walls are Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell Nabī Yūnus, site of a shrine to Jonah, the prophet who preached to Nineveh. Large amounts of Assyrian sculpture and other artifacts have been excavated there, and are now located in museums around the world.

Name

The English placename Nineveh comes from Latin ' and Septuagint Greek ''Nineuḗ'' () under influence of theBiblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

Hebrew ''Nīnəweh'' (),''Oxford English Dictionary'', 3rd ed. "Ninevite, ''n.'' and ''adj.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. from the Akkadian ' ( ''Ninâ''). or Old Babylonian '. The original meaning of the name is unclear but may have referred to a patron goddess. The cuneiform for ''Ninâ'' () is a fish within a house (cf. Aramaic ''nuna'', "fish"). This may have simply intended "Place of Fish" or may have indicated a goddess associated with fish or the Tigris, possibly originally of Hurrian origin. The city was later said to be devoted to "the goddess Ishtar of Nineveh" and ''Nina'' was one of the Sumerian

Sumerian or Sumerians may refer to:

*Sumer, an ancient civilization

**Sumerian language

**Sumerian art

**Sumerian architecture

**Sumerian literature

**Cuneiform script, used in Sumerian writing

*Sumerian Records, an American record label based in ...

and Assyrian names of that goddess.

Additionally, the word נון/נונא in Old Babylonian refers to the Anthiinae

Anthias are members of the family Serranidae and make up the subfamily Anthiinae. Anthias make up a sizeable portion of the population of pink, orange, and yellow reef fishes seen swarming in most coral reef photography and film. The name Anthi ...

genus of fish, further indicating the possibility of an association between the name Nineveh and fish.

The city was also known as ''Ninuwa'' in Mari; ''Ninawa'' in Aramaic; Ninwe (ܢܸܢܘܵܐ) in Syriac; and ''Nainavā'' () in Persian.

''Nabī Yūnus'' is the Arabic for "Prophet Jonah". ''Kuyunjiq'' was, according to Layard, a Turkish name (Layard used the form "kouyunjik", diminutive of "koyun", "sheep" in Turkish), and it was known as ''Armousheeah'' by the Arabs, and is thought to have some connection with the Kara Koyunlu dynasty. These toponyms refer to the areas to the North and South of the Khosr stream, respectively: Kuyunjiq is the name for the whole northern sector enclosed by the city walls and is dominated by the large (35 ha) mound of Tell Kuyunjiq, while Nabī (or more commonly Nebi) Yunus is the southern sector around of the mosque of Prophet Yunus/Jonah, which is located on Tell Nebi Yunus.

Geography

The remains of ancient Nineveh, the areas of Kuyunjiq and Nabī Yūnus with their mounds, are located on a level part of the plain at the junction of the Tigris and theKhosr River

The Khosr River (, ''Nahr al-Khosr'') was a tributary of the Tigris River which ran directly through the centre of the ancient city of Nineveh in Northern Mesopotamia. During the reign of Sennacherib, walls were built along the banks of the Khosr ...

s within an area of circumscribed by a fortification wall. This whole extensive space is now one immense area of ruins overlaid by c. one third by the Nebi Yunus suburbs of the city of eastern Mosul.

The site of ancient Nineveh is bisected by the Khosr river. North of the Khosr, the site is called Kuyunjiq, including the acropolis of Tell Kuyunjiq; the illegal village of Rahmaniye lay in eastern Kuyunjiq. South of the Khosr, the urbanized area is called Nebi Yunus (also Ghazliya, Jezayr, Jammasa), including Tell Nebi Yunus where the mosque of the Prophet Jonah and a palace of Esarhaddon/Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian language, Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Ashur (god), Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king o ...

below it are located. South of the street Al-'Asady (made by Daesh destroying swaths of the city walls) the area is called Jounub Ninawah or Shara Pepsi.

Nineveh was an important junction for commercial routes crossing the Tigris on the great roadway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, thus uniting the East and the West, it received wealth from many sources, so that it became one of the greatest of all the region's ancient cities, and the last capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

History

Early history

Nineveh was one of the oldest and greatest cities in antiquity. Texts from theHellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

period later offered an eponymous Ninus as the founder of Νίνου πόλις (Ninopolis), although there is no historical basis for this. Book of Genesis 10:11 says "Nimrod", possibly meaning Sargon I, built Nineveh. The context of Nineveh was as one of many centers within the regional development of Upper Mesopotamia. This area is defined as the plains which can support rain-fed agriculture. It exists as a narrow band from the Syrian coast

Syria is located in Western Asia, north of the Arabian Peninsula, at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Lebanon and Israel to the west and southwest, Iraq to the east, and Jordan to the south. It consi ...

to the Zagros mountains. It is bordered by deserts to the south and mountains to the north. The cultural practices, technology, and economy in this region were shared and they followed a similar trajectory out of the neolithic.

Neolithic

Caves in the Zagros Mountains adjacent to the north side of the Nineveh Plains were used as PPNA settlements, most famously Shanidar Cave. Nineveh itself was founded as early as 6000 BC during the late Neolithic period. Deep sounding at Nineveh uncovered soil layers that have been dated to early in the era of the Hassunaarchaeological culture

An archaeological culture is a recurring assemblage of types of artifacts, buildings and monuments from a specific period and region that may constitute the material culture remains of a particular past human society. The connection between thes ...

. The development and culture of Nineveh paralleled Tepe Gawra and Tell Arpachiyah a few kilometers to the northeast. Nineveh was a typical farming village in the Halaf Period

The Halaf culture is a prehistoric period which lasted between about 6100 BC and 5100 BC. The period is a continuous development out of the earlier Pottery Neolithic and is located primarily in the fertile valley of the Khabur River (Nahr al-K ...

.

Chalcolithic

In 5000 BC, Nineveh transitioned from a Halaf village to an Ubaid village. During the Late Chalcolithic period Nineveh was part one of the few Ubaid villages in Upper Mesopotamia which became a proto-city Ugarit, Brak, Hamoukar, Arbela,Alep

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

, and regionally at Susa, Eridu, Nippur. During the period between 4500 and 4000 BC it grew to 40ha.

The greater Nineveh area is notable in the diffusion of metal technology across the near east as the first location outside of Anatolia to smelt copper. Tell Arpachiyah has the oldest copper smelting remains, and Tepe Gawa has the oldest metal work. The copper came from the mines at Ergani.

Early Bronze Age

Nineveh became a trade colony of Uruk during the Uruk Expansion because of its location as the highest navigable point on the Tigris. It was contemporary and had a similar function toHabuba Kabira

Habuba Kabira (also Hubaba Kabire) at Tell Qanas is the site of an Uruk settlement along the Euphrates in Syria, founded during the later part of the Uruk period. It was about 800 mi (1,300 km) from the city of Uruk. The site is now mostly under ...

on the Euphrates. By 3000 BC, Kish civilization

The Kish civilization or Kish tradition was a concept created by Ignace Gelb and discarded by more recent scholarship, which Gelb placed in what he called the early East Semitic era in Mesopotamia and the Levant, starting in the early 4th millenn ...

had expanded into Nineveh. At this time, the main temple of Nineveh becomes known as Ishtar temple, re-dedicated to the Semite goddess Ishtar, in the form of Ishtar of Nineveh. Ishtar of Nineveh was conflated with Šauška from the Hurro-Urartian pantheon. This temple was called 'House of Exorcists' ( Cuneiform: 𒂷𒈦𒈦 GA2.MAŠ.MAŠ; Sumerian

Sumerian or Sumerians may refer to:

*Sumer, an ancient civilization

**Sumerian language

**Sumerian art

**Sumerian architecture

**Sumerian literature

**Cuneiform script, used in Sumerian writing

*Sumerian Records, an American record label based in ...

: e2 mašmaš). The context of the etymology surrounding the name is the Exorcist called a Mashmash in Sumerian, was a freelance magician who operated independent of the official priesthood, and was in part a medical professional via the act of expelling demons.

Ninevite 5 period

The regional influence of Nineveh became particularly pronounced during the archaeological period known as ''Ninevite 5'', or ''Ninevite V'' (2900–2600 BC). This period is defined primarily by the characteristic pottery that is found widely throughout Upper Mesopotamia.Ian Shaw''A Dictionary of Archaeology''

John Wiley & Sons, 2002 p. 427 Also, for the Upper Mesopotamian region, the ''Early Jezirah'' chronology has been developed by archaeologists. According to this regional chronology, 'Ninevite 5' is equivalent to the Early Jezirah I–II period. Ninevite 5 was preceded by the Late Uruk period. Ninevite 5 pottery is roughly contemporary to the

Early Transcaucasian culture

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Early ...

ware, and the Jemdet Nasr period ware. Iraqi ''Scarlet Ware'' culture also belongs to this period; this colourful painted pottery is somewhat similar to Jemdet Nasr ware. Scarlet Ware was first documented in the Diyala River

The Diyala River (Arabic: ; ku, Sîrwan; Farsi: , ) is a river and tributary of the Tigris. It is formed by the confluence of Sirwan river and Tanjaro river in Darbandikhan Dam in the Sulaymaniyah Governorate of Northern Iraq. It covers a total ...

basin in Iraq. Later, it was also found in the nearby Hamrin Basin, and in Luristan. It is also contemporary with the Proto-Elamite period in Susa.

Akkadian period

At this time Nineveh was still an autonomous city-state. It was incorporated into the Akkadian Empire. The early city (and subsequent buildings) was constructed on a fault line and, consequently, suffered damage from a number ofearthquakes

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

. One such event destroyed the first temple of Ishtar, which was rebuilt in 2260 BC by the Akkadian king Manishtushu.

Ur III period

In the final phase of the Early Bronze, Mesopotamia was dominated by the Ur III empire.Middle Bronze

After the fall of Ur in 2000 BC, with the transition into the Middle Bronze, Nineveh was absorbed into the rising power of Assyria.Old Assyrian period

The historic Nineveh is mentioned in the Old Assyrian Empire during the reign of Shamshi-Adad I (1809-1775) in about 1800 BC as a centre ofworship

Worship is an act of religious devotion usually directed towards a deity. It may involve one or more of activities such as veneration, adoration, praise, and praying. For many, worship is not about an emotion, it is more about a recognition ...

of Ishtar, whose cult was responsible for the city's early importance.

Late Bronze

Mitanni period

The goddess's statue was sent to PharaohAmenhotep III

Amenhotep III ( egy, jmn-ḥtp(.w), ''Amānəḥūtpū'' , "Amun is Satisfied"; Hellenized as Amenophis III), also known as Amenhotep the Magnificent or Amenhotep the Great, was the ninth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. According to different ...

of Egypt in the 14th century BC, by orders of the king of Mitanni. The Assyrian city of Nineveh became one of Mitanni's vassals for half a century until the early 14th century BC.

Middle Assyrian period

The Assyrian king Ashur-uballit I reclaimed it in 1365 BC while overthrowing the Mitanni Empire and creating theMiddle Assyrian Empire

The Middle Assyrian Empire was the third stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of Assyria from the accession of Ashur-uballit I 1363 BC and the rise of Assyria as a territorial kingdom to the death of Ashur-dan II in 912 BC. ...

(1365–1050 BC).

There is a large body of evidence to show that Assyrian monarchs built extensively in Nineveh during the late 3rd and 2nd millenniums BC; it appears to have been originally an "Assyrian provincial town". Later monarchs whose inscriptions have appeared on the high city include the Middle Assyrian Empire

The Middle Assyrian Empire was the third stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of Assyria from the accession of Ashur-uballit I 1363 BC and the rise of Assyria as a territorial kingdom to the death of Ashur-dan II in 912 BC. ...

kings Shalmaneser I (1274–1245 BC) and Tiglath-Pileser I (1114–1076 BC), both of whom were active builders in Assur (Ashur).

Iron Age

Neo-Assyrians

During the Neo-Assyrian Empire, particularly from the time ofAshurnasirpal II

Ashur-nasir-pal II (transliteration: ''Aššur-nāṣir-apli'', meaning " Ashur is guardian of the heir") was king of Assyria from 883 to 859 BC.

Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II, in 883 BC. During his reign he embarked ...

(ruled 883–859 BC) onward, there was considerable architectural expansion. Successive monarchs such as Tiglath-pileser III, Sargon II

Sargon II (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is general ...

, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian language, Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Ashur (god), Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king o ...

maintained and founded new palaces, as well as temples to Sîn

Nanna, Sīn or Suen ( akk, ), and in Aramaic ''syn'', ''syn’'', or even ''shr'' 'moon', or Nannar ( sux, ) was the god of the moon in the Mesopotamian religions of Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia and Aram. He was also associated with ...

, Ashur Ashur, Assur, or Asur may refer to:

Places

* Assur, an Assyrian city and first capital of ancient Assyria

* Ashur, Iran, a village in Iran

* Asur, Thanjavur district, a village in the Kumbakonam taluk of Thanjavur district, Tamil Nadu, India

* Assu ...

, Nergal

Nergal ( Sumerian: d''KIŠ.UNU'' or ; ; Aramaic: ܢܸܪܓܲܠ; la, Nirgal) was a Mesopotamian god worshiped through all periods of Mesopotamian history, from Early Dynastic to Neo-Babylonian times, with a few attestations under indicating hi ...

, Shamash

Utu (dUD "Sun"), also known under the Akkadian name Shamash, ''šmš'', syc, ܫܡܫܐ ''šemša'', he, שֶׁמֶשׁ ''šemeš'', ar, شمس ''šams'', Ashurian Aramaic: 𐣴𐣬𐣴 ''š'meš(ā)'' was the ancient Mesopotamian sun god. ...

, Ninurta

, image= Cropped Image of Carving Showing the Mesopotamian God Ninurta.png

, caption= Assyrian stone relief from the temple of Ninurta at Kalhu, showing the god with his thunderbolts pursuing Anzû, who has stolen the Tablet of Destinies from En ...

, Ishtar, Tammuz, Nisroch and Nabu.

Sennacherib's development of Nineveh

It was Sennacherib who made Nineveh a truly magnificent city (c. 700 BC). He laid out new streets and squares and built within it the South West Palace, or "palace without a rival", the plan of which has been mostly recovered and has overall dimensions of about . It comprised at least 80 rooms, many of which were lined with sculpture. A large number of cuneiform tablets were found in the palace. The solid foundation was made out of limestone blocks and mud bricks; it was tall. In total, the foundation is made of roughly of brick (approximately 160 million bricks). The walls on top, made out of mud brick, were an additional tall. Some of the principal doorways were flanked by colossal stone '' lamassu'' door figures weighing up to ; these were winged Mesopotamian lions or bulls, with human heads. These were transported from quarries at Balatai, and they had to be lifted up once they arrived at the site, presumably by a ramp. There are also of stone Assyrian palace reliefs, that include pictorial records documenting every construction step including carving the statues and transporting them on a barge. One picture shows 44 men towing a colossal statue. The carving shows three men directing the operation while standing on the Colossus. Once the statues arrived at their destination, the final carving was done. Most of the statues weigh between . The stone carvings in the walls include many battle scenes, impalings and scenes showing Sennacherib's men parading the spoils of war before him. The inscriptions boasted of his conquests: he wrote ofBabylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

: "Its inhabitants, young and old, I did not spare, and with their corpses I filled the streets of the city." A full and characteristic set shows the campaign leading up to the siege of Lachish in 701; it is the "finest" from the reign of Sennacherib, and now in the British Museum. He later wrote about a battle in Lachish: "And Hezekiah of Judah who had not submitted to my yoke...him I shut up in Jerusalem his royal city like a caged bird. Earthworks I threw up against him, and anyone coming out of his city gate I made pay for his crime. His cities which I had plundered I had cut off from his land."

At this time, the total area of Nineveh comprised about , and fifteen great gates penetrated its walls. An elaborate system of eighteen canals brought water from the hills to Nineveh, and several sections of a magnificently constructed aqueduct erected by Sennacherib were discovered at Jerwan, about distant. The enclosed area had more than 100,000 inhabitants (maybe closer to 150,000), about twice as many as Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

at the time, placing it among the largest settlements worldwide.

Some scholars such as Stephanie Dalley

Stephanie Mary Dalley FSA (''née'' Page; March 1943) is a British Assyriologist and scholar of the Ancient Near East. She has retired as a teaching Fellow from the Oriental Institute, Oxford. She is known for her publications of cuneiform te ...

at Oxford believe that the garden which Sennacherib built next to his palace, with its associated irrigation works, were the original Hanging Gardens of Babylon

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World listed by Hellenic culture. They were described as a remarkable feat of engineering with an ascending series of tiered gardens containing a wide variety of tre ...

; Dalley's argument is based on a disputation of the traditional placement of the Hanging Gardens attributed to Berossus together with a combination of literary and archaeological evidence.

After Ashurbanipal

The greatness of Nineveh was short-lived. In around 627 BC, after the death of its last great king

The greatness of Nineveh was short-lived. In around 627 BC, after the death of its last great king Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian language, Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Ashur (god), Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king o ...

, the Neo-Assyrian Empire began to unravel through a series of bitter civil wars between rival claimants for the throne, and in 616 BC Assyria was attacked by its own former vassals, the Babylonians, Chaldeans

Chaldean (also Chaldaean or Chaldee) may refer to:

Language

* an old name for the Aramaic language, particularly Biblical Aramaic

* Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, a modern Aramaic language

* Chaldean script, a variant of the Syriac alphabet

Places

* C ...

, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians. In about 616 BC Kalhu was sacked, the allied forces eventually reached Nineveh, besieging and sacking the city in 612 BC, following bitter house-to-house fighting, after which it was razed. Most of the people in the city who could not escape to the last Assyrian strongholds in the north and west were either massacred or deported out of the city and into the countryside where they founded new settlements. Many unburied skeletons were found by the archaeologists at the site. The Assyrian Empire then came to an end by 605 BC, the Medes and Babylonians dividing its colonies between themselves.

It is not clear whether Nineveh came under the rule of the Medes or the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 612. The Babylonian '' Chronicle Concerning the Fall of Nineveh'' records that Nineveh was "turned into mounds and heaps", but this is literary hyperbole. The complete destruction of Nineveh has traditionally been seen as confirmed by the Hebrew '' Book of Ezekiel'' and the Greek '' Retreat of the Ten Thousand'' of Xenophon (d. 354 BC).Stephanie Dalley (1993), "Nineveh after 612 BC", ''Altorientalische Forschungen'' 20(1): 134–147. There are no later cuneiform tablets in Akkadian from Nineveh. Although devastated in 612, the city was not completely abandoned. Yet, to the Greek historians Ctesias and Herodotus (c. 400 BC), Nineveh was a thing of the past; and when Xenophon passed the place in the 4th century BC he described it as abandoned.

Later history

The earliest piece of written evidence for the persistence of Nineveh as a settlement is possibly the Cyrus Cylinder of 539/538 BC, but the reading of this is disputed. If correctly read as Nineveh, it indicates thatCyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

restored the temple of Ishtar at Nineveh and probably encouraged resettlement. A number of cuneiform Elamite tablets have been found at Nineveh. They probably date from the time of the revival of Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

in the century following the collapse of Assyria. The Hebrew '' Book of Jonah'', which Stephanie Dalley asserts was written in the 4th century BC, is an account of the city's repentance and God's mercy which prevented destruction.

Archaeologically, there is evidence of repairs at the temple of Nabu after 612 and for the continued use of Sennacherib's palace. There is evidence of syncretic Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

cults. A statue of Hermes has been found and a Greek inscription attached to a shrine of the Sebitti. A statue of Herakles Epitrapezios dated to the 2nd century AD has also been found. The library of Ashurbanipal

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Assyrian Empire, is a collection of more than 30,000 clay tablets and fragments containing texts of all kinds from the 7th century BC, including texts in vari ...

may still have been in use until around the time of Alexander the Great.

The city was actively resettled under the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

.Peter Webb, "Nineveh and Mosul", in O. Nicholason (ed.), ''The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity

The ''Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity'' (ODLA) is the first comprehensive, multi-disciplinary reference work covering culture, history, religion, and life in Late Antiquity. This was the period in Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Near Eas ...

'' (Oxford University Press, 2018), vol. 2, p. 1078. There is evidence of more changes in Sennacherib's palace under the Parthian Empire. The Parthians also established a municipal mint at Nineveh coining in bronze. According to Tacitus, in AD 50 Meherdates

Meherdates ( xpr, 𐭌𐭄𐭓𐭃𐭕 ''Mihrdāt'') was a Parthian prince who competed against Gotarzes II () for the Parthian crown from 49 to 51 AD. A son of Vonones I

Vonones I ( ''Onōnēs'' on his coins) was an Arsacid prince, who ruled ...

, a claimant to the Parthian throne with Roman support, took Nineveh.J. E. Reade (1998), "Greco-Parthian Nineveh", ''Iraq'' 60: 65–83.

By Late Antiquity, Nineveh was restricted to the east bank of the Tigris and the west bank was uninhabited. Under the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

, Nineveh was not an administrative centre. By the 2nd century AD there were Christians present and by 554 it was a bishopric of the Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

. King Khosrow II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king (shah) of Iran, ruling fr ...

(591–628) built a fortress on the west bank, and two Christian monasteries were constructed around 570 and 595. This growing settlement was not called Mosul until after the Arab conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

. It may have been called Hesnā ʿEbrāyē (Jews' Fort).

In 627, the city was the site of the Battle of Nineveh (627), Battle of Nineveh between the Byzantine Empire, Eastern Roman Empire and the Sasanians. In 641, it was Muslim conquest of Persia, conquered by the Arabs, who built a mosque on the west bank and turned it into an administrative centre. Under the Umayyad dynasty, it eclipsed Nineveh, which was reduced to a Christian suburb with limited new construction. By the 13th century, Nineveh was mostly ruins. A church was converted into Islamic sites of Mosul, a Muslim shrine to the prophet Jonah, which continued to attract pilgrims until Fall of Mosul, its destruction by ISIL in 2014.

Biblical Nineveh

In the Hebrew Bible, Nineveh is first mentioned in Genesis 10:11: "Ashur (Bible), Ashur left that land, and built Nineveh". Some modern English translations interpret "Ashur" in the Hebrew of this verse as the country "Assyria" rather than a person, thus making Nimrod, rather than Ashur, the founder of Nineveh. Sir Walter Raleigh's notion that Nimrod built Nineveh, and the cities in Genesis 10:11–12, has also been refuted by scholars. The discovery of the fifteen Book of Jubilees, Jubilees texts found amongst the Dead Sea Scrolls has since shown that, according to the Jews, Jewish sects of Qumran, Genesis 10:11 affirms the apportionment of Nineveh to Ashur. The attribution of Nineveh to Ashur is also supported by the Septuagint, Greek Septuagint, King James Version, King James Bible, Geneva Bible, and by Roman historian Josephus, Flavius Josephus in his ''Antiquities of the Jews'' (Antiquities, i, vi, 4). Nineveh was the flourishing capital of the Assyrian Empire and was the home of King Sennacherib, King of Assyria, during the Biblical reign of King Hezekiah () and the lifetime of Judean prophet Isaiah (). As recorded in Hebrew scripture, Nineveh was also the place where Sennacherib died at the hands of his two sons, who then fled to the vassal land of ''`rrt'' (Urartu). The book of the prophet Nahum is almost exclusively taken up with prophetic denunciations against Nineveh. Its ruin and utter desolation are foretold. Its end was strange, sudden, and tragic. According to the Bible, it was God's doing, his judgment on Assyria's pride. In fulfillment of prophecy, God made "an utter end of the place". It became a "desolation". The prophet Zephaniah also predicts its destruction along with the fall of the empire of which it was the capital. Nineveh is also the setting of the Book of Tobit. The Book of Jonah, set in the days of the Assyrian Empire, describes it as an "exceedingly great city of three days' journey in breadth", whose population at that time is given as "more than 120,000". Genesis 10:11–12 lists four cities "Nineveh, Rehoboth, Calah, and Resen", ambiguously stating that either Resen or Calah is "the great city". The ruins of Kuyunjiq, Nimrud, Karamlesh and Dur-Sharrukin, Khorsabad form the four corners of an irregular quadrilateral. The ruins of the "great city" Nineveh, with the whole area included within the parallelogram they form by lines drawn from the one to the other, are generally regarded as consisting of these four sites. The description of Nineveh in Jonah likely was a reference to greater Nineveh, including the surrounding cities of Rehoboth, Calah and Resen The Book of Jonah depicts Nineveh as a wicked city worthy of destruction. God sent Jonah to preach to the Ninevites of their coming destruction, and they fasted and repented because of this. As a result, God spared the city; when Jonah protests against this, God states he is showing mercy for the population who are ignorant of the difference between right and wrong ("who cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand") and mercy for the animals in the city. Nineveh's repentance and salvation from evil can be found in the Hebrew Tanakh, also known as the Old Testament), and referred to in the Christian New Testament and Muslim Quran. To this day, Syriac Christianity, Syriac and Oriental Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodox churches commemorate the three days Jonah spent inside the fish during the Fast of Nineveh. Some Christians observe this holiday fast by refraining from food and drink, with churches encouraging followers to refrain from meat, fish and dairy products.Archaeology

The location of Nineveh was known, to some, continuously through the Middle Ages. Benjamin of Tudela visited it in 1170; Petachiah of Regensburg soon after. Carsten Niebuhr recorded its location during the 1761–1767 Danish Arabia expedition (1761–1767), Danish expedition. Niebuhr wrote afterwards that "I did not learn that I was at so remarkable a spot, till near the river. Then they showed me a village on a great hill, which they call Nunia, and a mosque, in which the prophet Jonah was buried. Another hill in this district is called Kalla Nunia, or the Castle of Nineveh. On that lies a village Koindsjug."Excavation history

In 1842, the French Consul General at Mosul, Paul-Émile Botta, began to search the vast mounds that lay along the opposite bank of the river. While at Tell Kuyunjiq he had little success, the locals whom he employed in these excavations, to their great surprise, came upon the ruins of a building at the 20 km far-away mound of Khorsabad, which, on further exploration, turned out to be the royal palace ofSargon II

Sargon II (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is general ...

, in which large numbers of reliefs were found and recorded, though they had been damaged by fire and were mostly too fragile to remove.

In 1847 the young British diplomat Austen Henry Layard explored the ruins. Layard did not use modern archaeological methods; his stated goal was "to obtain the largest possible number of well preserved objects of art at the least possible outlay of time and money". In the Kuyunjiq mound, Layard rediscovered in 1849 the lost palace of Sennacherib with its 71 rooms and colossal bas-reliefs. He also unearthed the palace and famous

In 1847 the young British diplomat Austen Henry Layard explored the ruins. Layard did not use modern archaeological methods; his stated goal was "to obtain the largest possible number of well preserved objects of art at the least possible outlay of time and money". In the Kuyunjiq mound, Layard rediscovered in 1849 the lost palace of Sennacherib with its 71 rooms and colossal bas-reliefs. He also unearthed the palace and famous library of Ashurbanipal

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Assyrian Empire, is a collection of more than 30,000 clay tablets and fragments containing texts of all kinds from the 7th century BC, including texts in vari ...

with 22,000 cuneiform clay tablets. Most of Layard's material was sent to the British Museum, but others were dispersed elsewhere as two large pieces which were given to Lady Charlotte Guest and eventually found their way to the Metropolitan Museum. The study of the archaeology of Nineveh reveals the wealth and glory of ancient Assyria under kings such as Esarhaddon (681–669 BC) and Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian language, Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Ashur (god), Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king o ...

(669–626 BC).

The work of exploration was carried on by Hormuzd Rassam (an Assyrian people, Assyrian), George Smith (Assyriologist), George Smith and others, and a vast treasury of specimens of Assyria was incrementally exhumed for European museums. Palace after palace was discovered, with their decorations and their sculptured slabs, revealing the life and manners of this ancient people, their arts of war and peace, the forms of their religion, the style of their architecture, and the magnificence of their monarchs.

The mound of Kuyunjiq was excavated again by the archaeologists of the British Museum, led by Leonard William King, at the beginning of the 20th century. Their efforts concentrated on the site of the Temple of Nabu, the god of writing, where another cuneiform library was supposed to exist. However, no such library was ever found: most likely, it had been destroyed by the activities of later residents.

The excavations started again in 1927, under the direction of Reginald Campbell Thompson, Campbell Thompson, who had taken part in King's expeditions. Some works were carried out outside Kuyunjiq, for instance on the mound of Tell Nebi Yunus, which was the ancient arsenal of Nineveh, or along the outside walls. Here, near the northwestern corner of the walls, beyond the pavement of a later building, the archaeologists found almost 300 fragments of prisms recording the royal annals of Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal, beside a prism of Esarhaddon which was almost perfect.

After the Second World War, several excavations were carried out by Iraqis, Iraqi archaeologists. From 1951 to 1958, Mohammed Ali Mustafa worked the site. The work was continued from 1967 through 1971 by Tariq Madhloom. Some additional excavation occurred by Manhal Jabur from the early 1970s to 1987. For the most part, these digs focused on Tell Nebi Yunus.

The British archaeologist and Assyriologist Professor David Stronach of the University of California, Berkeley conducted a series of surveys and digs at the site from 1987 to 1990, focusing his attentions on the several gates and the existent mudbrick walls, as well as the system that supplied water to the city in times of siege. The excavation reports are in progress.

Most recently, an Iraqi–Italian Archaeological Expedition by the University of Bologna, Alma Mater Studiorum – University of Bologna and the IraqSBAH

led by Nicolò Marchetti, began (with four campaigns having taken place thus far between 2019 and 2022) a long-term project aiming at the excavation, conservation and public presentation of the lower town of Nineveh. Work was carried out in eighteen excavation areas, from the Adad Gate – now completely repaired (after removing hundreds of tons of debris from ISIL's destructions), explored and protected with a new roof – deep into the Nebi Yunus town. In a few areas a thick later stratigraphy was encountered, but the late 7th century BC stratum was reached everywhere (actually in two areas in the pre-Sennacherib lower town the excavations already exposed older strata, up to the 11th century BC until now, aiming in the future at exploring the first settlement therein). The site is greatly endangered with dumping of debris, illegal settlements and quarrying as the main threats.

Archaeological remains

Today, Nineveh's location is marked by two large mounds, Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell ''Nabī Yūnus'' "Prophet Jonah", and the remains of the city walls (about in circumference). The Neo-Assyrian levels of Kuyunjiq have been extensively explored. The other mound, ''Nabī Yūnus'', has not been as extensively explored because there was an Arab Muslim shrine dedicated to that prophet on the site. On July 24, 2014, the Islamic State destroyed the shrine as part of a Destruction of cultural heritage by the Islamic State, campaign to destroy religious sanctuaries it deemed "un-Islamic", but also to loot that site through tunneling.

The ruin mound of Kuyunjiq rises about above the surrounding plain of the ancient city. It is quite broad, measuring about . Its upper layers have been extensively excavated, and several Neo-Assyrian palaces and temples have been found there. A deep sounding by Max Mallowan revealed evidence of habitation as early as the 6th millennium BC. Today, there is little evidence of these old excavations other than weathered pits and earth piles. In 1990, the only Assyrian remains visible were those of the entry court and the first few chambers of the Palace of Sennacherib. Since that time, the palace chambers have received significant damage by looters. Portions of relief sculptures that were in the palace chambers in 1990 were seen on the antiquities market by 1996. Photographs of the chambers made in 2003 show that many of the fine relief sculptures there have been reduced to piles of rubble.

Today, Nineveh's location is marked by two large mounds, Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell ''Nabī Yūnus'' "Prophet Jonah", and the remains of the city walls (about in circumference). The Neo-Assyrian levels of Kuyunjiq have been extensively explored. The other mound, ''Nabī Yūnus'', has not been as extensively explored because there was an Arab Muslim shrine dedicated to that prophet on the site. On July 24, 2014, the Islamic State destroyed the shrine as part of a Destruction of cultural heritage by the Islamic State, campaign to destroy religious sanctuaries it deemed "un-Islamic", but also to loot that site through tunneling.

The ruin mound of Kuyunjiq rises about above the surrounding plain of the ancient city. It is quite broad, measuring about . Its upper layers have been extensively excavated, and several Neo-Assyrian palaces and temples have been found there. A deep sounding by Max Mallowan revealed evidence of habitation as early as the 6th millennium BC. Today, there is little evidence of these old excavations other than weathered pits and earth piles. In 1990, the only Assyrian remains visible were those of the entry court and the first few chambers of the Palace of Sennacherib. Since that time, the palace chambers have received significant damage by looters. Portions of relief sculptures that were in the palace chambers in 1990 were seen on the antiquities market by 1996. Photographs of the chambers made in 2003 show that many of the fine relief sculptures there have been reduced to piles of rubble.

City wall and gates

Nergal

Nergal ( Sumerian: d''KIŠ.UNU'' or ; ; Aramaic: ܢܸܪܓܲܠ; la, Nirgal) was a Mesopotamian god worshiped through all periods of Mesopotamian history, from Early Dynastic to Neo-Babylonian times, with a few attestations under indicating hi ...

, it may have been used for some ceremonial purpose, as it is the only known gate flanked by stone sculptures of winged bull-men ('' lamassu''). The reconstruction is conjectural, as the gate was excavated by Layard in the mid-19th century and reconstructed in the mid-20th century. The lamassu on this gate were defaced with a jackhammer by ISIL forces.

* Adad Gate: Adad Gate was named for the god Adad. A reconstruction was begun in the 1960s by Iraqis but was not completed. The result was a mixture of concrete and eroding mudbrick, which nonetheless does give some idea of the original structure. The excavator left some features unexcavated, allowing a view of the original Assyrian construction. The original brickwork of the outer vaulted passageway was well exposed, as was the entrance of the vaulted stairway to the upper levels. The actions of Nineveh's last defenders could be seen in the hastily built mudbrick construction which narrowed the passageway from . Around April 13, 2016, ISIL demolished both the gate and the adjacent wall by flattening them with a bulldozer.

* Shamash Gate: Named for the sun god Shamash

Utu (dUD "Sun"), also known under the Akkadian name Shamash, ''šmš'', syc, ܫܡܫܐ ''šemša'', he, שֶׁמֶשׁ ''šemeš'', ar, شمس ''šams'', Ashurian Aramaic: 𐣴𐣬𐣴 ''š'meš(ā)'' was the ancient Mesopotamian sun god. ...

, it opens to the road to Erbil. It was excavated by Layard in the 19th century. The stone retaining wall and part of the mudbrick structure were reconstructed in the 1960s. The mudbrick reconstruction has deteriorated significantly. The stone wall projects outward about from the line of main wall for a width of about . It is the only gate with such a significant projection. The mound of its remains towers above the surrounding terrain. Its size and design suggest it was the most important gate in Neo-Assyrian times.

* Hali Gate: Near the south end of the eastern city wall. Exploratory excavations were undertaken here by the University of California, Berkeley expedition of 1989–1990. There is an outward projection of the city wall, though not as pronounced as at the Shamash Gate. The entry passage had been narrowed with mudbrick to about as at the Adad Gate. Human remains from the final battle of Nineveh were found in the passageway. Located in the eastern wall, it is the southernmost and largest of all the remaining gates of ancient Nineveh.

Threats to the site

By 2003, the site of Nineveh was exposed to decay of its reliefs by a lack of proper protective roofing, vandalism and looting holes dug into chamber floors. Future preservation is further compromised by the site's proximity to expanding suburbs. The ailing Mosul Dam is a persistent threat to Nineveh as well as the city of Mosul. This is in no small part due to years of disrepair (in 2006, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers cited it as the most dangerous dam in the world), the cancellation of a second dam project in the 1980s to act as flood relief in case of failure, and occupation by Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, ISIL in 2014 resulting in fleeing workers and stolen equipment. If the dam fails, the entire site could be under as much as 45 feet (14 m) of water. In an October 2010 report titled ''Saving Our Vanishing Heritage'', Global Heritage Fund named Nineveh one of 12 sites most "on the verge" of irreparable destruction and loss, citing insufficient management, development pressures and looting as primary causes. By far, the greatest threat to Nineveh has been purposeful human actions by Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, ISIL, which first occupied the area in the mid-2010s. In early 2015, they announced their intention to destroy the walls of Nineveh if the Iraqis tried to liberate the city. They also threatened to destroy artifacts. On February 26 they destroyed several items and statues in the Mosul Museum and are believed to have plundered others to sell overseas. The items were mostly from the Assyrian exhibit, which ISIL declared blasphemy, blasphemous and Idolatry, idolatrous. There were 300 items remaining in the museum out of a total of 1,900, with the other 1,600 being taken to the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad for security reasons prior to the 2014 Fall of Mosul. Some of the artifacts sold and/or destroyed were from Nineveh. Just a few days after the destruction of the museum pieces, they demolished remains at major UNESCO world heritage sites Khorsabad, Nimrud, and Hatra.Rogation of the Ninevites (Nineveh's Wish)

Assyrian people, Assyrians of the Ancient Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Assyrian Church of the East and Saint Thomas Christians of the Syro-Malabar Church observe a fast called ''Ba'uta d-Ninwe'' (ܒܥܘܬܐ ܕܢܝܢܘܐ) which means ''Nineveh's Prayer''. Copts and Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Ethiopian Orthodox also maintain this fast.Popular culture

The English Romantic poet Edwin Atherstone wrote an epic ''The Fall of Nineveh''. The work tells of an uprising against its king Sardanapalus of all the nations that were dominated by the Assyrian Empire. He is a great criminal. He has had one hundred prisoners of war executed. After a long struggle the town is conquered by Median and Babylonian troops led by prince Arbaces and priest Belesis. The king sets his own palace on fire and dies inside together with all his concubines. Atherstone's friend, the artist John Martin (painter), John Martin, created a painting of the same name inspired by the poem. The English poet John Masefield's well-known, fanciful 1903 poem ''Salt-Water Poems and Ballads#"Cargoes", Cargoes'' mentions Nineveh in its first line. Nineveh is also mentioned in Rudyard Kipling's 1897 poem ''Recessional (poem), Recessional'' and in Arthur O'Shaughnessy's 1873 poem ''Ode (poem), Ode''.

The 1962 Italian peplum (film genre), peplum film ''War Gods of Babylon'', is based on the sacking and fall of Nineveh by the combined rebel armies led by the Babylonians.

In ''Jonah: A VeggieTales Movie'', Jonah, much like his biblical counterpart, must travel to Nineveh due to God’s demands.

In the 1973 film ''The Exorcist (film), The Exorcist'', Father Lankester Merrin was on an archeological dig near Nineveh prior to returning to the United States and leading the exorcism of Reagan MacNiel.

Atherstone's friend, the artist John Martin (painter), John Martin, created a painting of the same name inspired by the poem. The English poet John Masefield's well-known, fanciful 1903 poem ''Salt-Water Poems and Ballads#"Cargoes", Cargoes'' mentions Nineveh in its first line. Nineveh is also mentioned in Rudyard Kipling's 1897 poem ''Recessional (poem), Recessional'' and in Arthur O'Shaughnessy's 1873 poem ''Ode (poem), Ode''.

The 1962 Italian peplum (film genre), peplum film ''War Gods of Babylon'', is based on the sacking and fall of Nineveh by the combined rebel armies led by the Babylonians.

In ''Jonah: A VeggieTales Movie'', Jonah, much like his biblical counterpart, must travel to Nineveh due to God’s demands.

In the 1973 film ''The Exorcist (film), The Exorcist'', Father Lankester Merrin was on an archeological dig near Nineveh prior to returning to the United States and leading the exorcism of Reagan MacNiel.

See also

* Cities of the ancient Near East * Destruction of cultural heritage by the Islamic State * Historical urban community sizes * Isaac of Nineveh * List of megalithic sites * Nanshe * Short chronology timeline * Tel KeppeNotes

References

:: * * * * ** ** ** ** ** * ** ** ** * * * - Nineveh 5, Vessel Pottery 2900 BC * - Early worship of Ishtar, Early / Prehistoric Nineveh * – Early / Prehistoric NinevehExternal links

Joanne Farchakh-Bajjaly photos

of Nineveh taken in May 2003 showing damage from looters

John Malcolm Russell, "Stolen stones: the modern sack of Nineveh"

in ''Archaeology''; looting of sculptures in the 1990s

Nineveh page

at the British Museum's website. Includes photographs of items from their collection.

A teaching and research tool presenting a comprehensive picture of Nineveh within the history of archaeology in the Near East, including a searchable data repository for meaningful analysis of currently unlinked sets of data from different areas of the site and different episodes in the 160-year history of excavations

CyArk Digital Nineveh Archives

publicly accessible, free depository of the data from the previously linked UC Berkeley Nineveh Archives project, fully linked and georeferenced in a UC Berkeley/CyArk research partnership to develop the archive for open web use. Includes creative commons-licensed media items.

Photos of Nineveh, 1989–1990

: Babylonian Chronicle Concerning the Fall of Nineveh

Layard's Nineveh and its Remains- full text

{{Authority control Populated places established in the 6th millennium BC Populated places disestablished in the 13th century Ancient Assyrian cities Destroyed cities Archaeological sites in Iraq Assyria Assyrian geography Hebrew Bible cities Nineveh Governorate Former populated places in Iraq Ancient Mesopotamia Jonah Tells (archaeology) Hassuna culture Nimrod Book of Jubilees Old Assyrian Empire City-states