Nicolaus von Amsdorf on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nicolaus von Amsdorf (German: Nikolaus von Amsdorf, 3 December 1483 – 14 May 1565) was a German

Nicolaus von Amsdorf (German: Nikolaus von Amsdorf, 3 December 1483 – 14 May 1565) was a German

Lutheran Cyclopedia

p. 13, "Nickolaus von Amsdorf". {{DEFAULTSORT:Amsdorf, Nicolaus Von 1483 births 1565 deaths People from Torgau People from the Electorate of Saxony 16th-century Lutheran bishops German Lutheran theologians Roman Catholic bishops of Naumburg University of Wittenberg faculty Clergy from Saxony 16th-century German Protestant theologians German male non-fiction writers Lutheran bishops and administrators of German prince-bishoprics 16th-century German male writers People educated at the St. Thomas School, Leipzig

Nicolaus von Amsdorf (German: Nikolaus von Amsdorf, 3 December 1483 – 14 May 1565) was a German

Nicolaus von Amsdorf (German: Nikolaus von Amsdorf, 3 December 1483 – 14 May 1565) was a German Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

theologian and an early Protestant reformer. As bishop of Naumburg

Naumburg () is a town in (and the administrative capital of) the district Burgenlandkreis, in the state of Saxony-Anhalt, Central Germany. It has a population of around 33,000. The Naumburg Cathedral became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2018. ...

(1542–1546), he became the first Lutheran bishop in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

.

Biography

He was born inTorgau

Torgau () is a town on the banks of the Elbe in northwestern Saxony, Germany. It is the capital of the district Nordsachsen.

Outside Germany, the town is best known as where on 25 April 1945, the United States and Soviet Armies forces firs ...

, on the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Rep ...

.

He was educated at Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

, and then at Wittenberg

Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the River Elbe, north of ...

, where he was one of the first who matriculated (1502) in the recently founded university. He soon obtained various academic honours, and became professor of theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

in 1511.

Like Andreas Karlstadt, he was at first a leading exponent of the older type of scholastic

Scholastic may refer to:

* a philosopher or theologian in the tradition of scholasticism

* ''Scholastic'' (Notre Dame publication)

* Scholastic Corporation, an American publishing company of educational materials

* Scholastic Building, in New Y ...

theology, but under the influence of Luther abandoned his Aristotelian positions for a theology based on the Augustinian doctrine of grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uninc ...

. Throughout his life he remained one of Luther's most determined supporters; he was with him at the Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

conference (1519), and the Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned to ...

(1521); and was privy to the secret of his Wartburg

The Wartburg () is a castle originally built in the Middle Ages. It is situated on a precipice of to the southwest of and overlooking the town of Eisenach, in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It was the home of St. Elisabeth of Hungary, the ...

seclusion. He assisted the first efforts of the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

at Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label= Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Mag ...

(1524), at Goslar

Goslar (; Eastphalian: ''Goslär'') is a historic town

A town is a human settlement. Towns are generally larger than villages and smaller than city, cities, though the criteria to distinguish between them vary considerably in different p ...

(1531) and at Einbeck

Einbeck (; Eastphalian: ''Aimbeck'') is a town in the district Northeim, in southern Lower Saxony, Germany, on the German Timber-Frame Road.

History

Prehistory

The area of the current city of Einbeck is inhabited since prehistoric times. Var ...

(1534); took an active part in the debates at Schmalkalden

Schmalkalden () is a town in the Schmalkalden-Meiningen district, in the southwest of the state of Thuringia, Germany. It is on the southern slope of the Thuringian Forest at the Schmalkalde river, a tributary to the Werra. , the town had a popu ...

(1537), where he defended the use of the sacrament by the unbelieving; and (1539) spoke out strongly against the bigamy of the Landgrave of Hesse.

After the death of Philip of the Palatinate, bishop of Naumburg-Zeitz, he was installed there on 20 January 1542, though in opposition to the chapter, by the Prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the Holy Roman Emperor, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century ...

of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

and Luther. His position was a painful one, and he longed to get back to Magdeburg, but was persuaded by Luther to stay. After Luther's death (1546) and the Battle of Mühlberg

The Battle of Mühlberg took place near Mühlberg in the Electorate of Saxony in 1547, during the Schmalkaldic War. The Catholic princes of the Holy Roman Empire led by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V decisively defeated the Lutheran Schma ...

(1547) he had to yield to his rival, Julius von Pflug

Julius von Pflug (1499 in Eythra – 3 September 1564 in Zeitz) was the last Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Naumburg from 1542 until his death. He was one of the most significant reformers involved with the Protestant Reformation.

Life

...

, and retire to the protection of the young duke of Weimar. Here he took part in founding Jena University

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The un ...

(1558); opposed the "Augsburg Interim

The Augsburg Interim (full formal title: ''Declaration of His Roman Imperial Majesty on the Observance of Religion Within the Holy Empire Until the Decision of the General Council'') was an imperial decree ordered on 15 May 1548 at the 1548 Die ...

" (1548); superintended the publication of the Jena edition of Luther's works; and debated on the freedom of the will, original sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature in need of regeneration and a proclivity to sinful conduct. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 ( ...

, and, more noticeably, on the Christian value of good works

In Christian theology, good works, or simply works, are a person's (exterior) actions or deeds, in contrast to inner qualities such as grace or faith.

Views by denomination

Anglican Churches

The Anglican theological tradition, including Th ...

, in regard to which he held that they were not only useless, but prejudicial in the matter of man's salvation. He urged the separation of the High Lutheran party from Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

(1557), got the Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country ( Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the No ...

dukes to oppose the Frankfurt Recess (1558) and continued to fight for the purity of Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

doctrine.

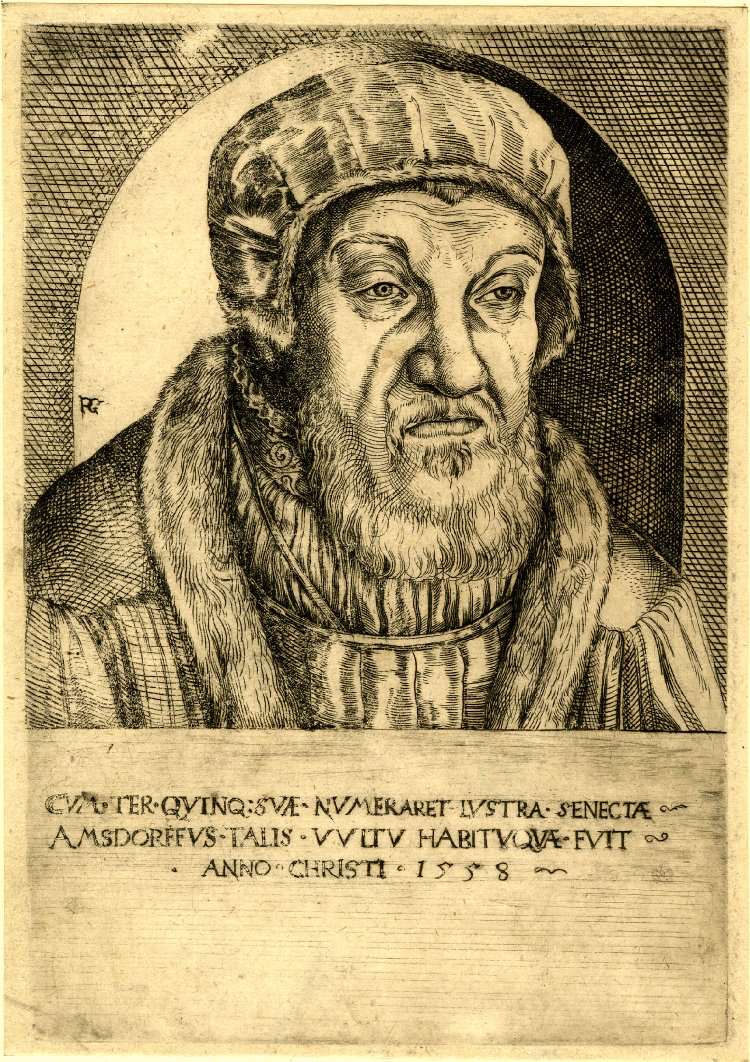

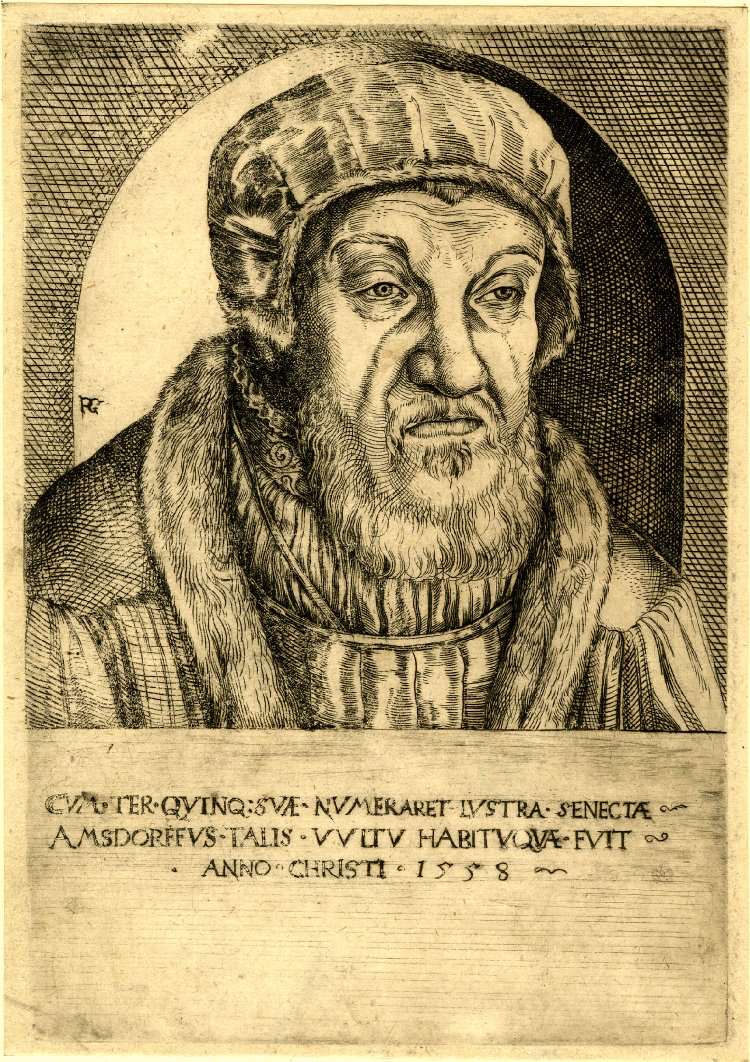

He died at Eisenach

Eisenach () is a town in Thuringia, Germany with 42,000 inhabitants, located west of Erfurt, southeast of Kassel and northeast of Frankfurt. It is the main urban centre of western Thuringia and bordering northeastern Hessian regions, sit ...

in 1565, and was buried in the church of St. Georg there, where his effigy

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

shows a well-knit frame and sharp-cut features.

Assessment

He was a man of strong will, of great aptitude for controversy, and considerable learning, and thus exercised a decided influence on the Reformation. Many letters and other short productions of his pen are extant in manuscript, especially five thick volumes of Amsdorfiana, in the Weimar library. They are a valuable source for our knowledge of Luther. A small sect, which adopted his opinion on good works, was called after him; but it is now of mere historical interest.See also

*Amsdorfians

The Amsdorfians were an early sect of Protestant Christians, who took their name from the 16th-century German reformer Nicolaus von Amsdorf. They maintained that good works were not only unprofitable, but obstacles, to salvation. The Amsdorfians w ...

* Katharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora (; 29 January 1499 – 20 December 1552), after her wedding Katharina Luther, also referred to as "die Lutherin" ("the Lutheress"), was the wife of Martin Luther, German reformer and a seminal figure of the Protestant Reformat ...

References

* Henry Eyster JacobsLutheran Cyclopedia

p. 13, "Nickolaus von Amsdorf". {{DEFAULTSORT:Amsdorf, Nicolaus Von 1483 births 1565 deaths People from Torgau People from the Electorate of Saxony 16th-century Lutheran bishops German Lutheran theologians Roman Catholic bishops of Naumburg University of Wittenberg faculty Clergy from Saxony 16th-century German Protestant theologians German male non-fiction writers Lutheran bishops and administrators of German prince-bishoprics 16th-century German male writers People educated at the St. Thomas School, Leipzig