Nicolae Ceaușescu ( , , – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

politician who served as the

general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party

The Romanian Communist Party ( ro, Partidul Comunist Român, , PCR) was a communist party in Romania. The successor to the pro-Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave ideological endorsement to a communist revolution that woul ...

from 1965 to 1989. He was the second and last communist leader of

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

. He was also the country's

head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

from 1967 to 1989, and widely classified as a

dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

, serving as President of the

State Council State Council may refer to:

Government

* State Council of the Republic of Korea, the national cabinet of South Korea, headed by the President

* State Council of the People's Republic of China, the national cabinet and chief administrative auth ...

and from 1974 concurrently as

President of the Republic, until his overthrow and

execution in the

Romanian Revolution in December 1989, part of a series of

anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

uprisings in

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

that year.

Born in 1918 in

Scornicești, Ceaușescu was a member of the Romanian Communist youth movement. He was arrested in 1939 and sentenced for "conspiracy against social order", spending the time during the war in prisons and internment camps: Jilava (1940), Caransebeș (1942), Văcărești (1943), and Târgu Jiu (1943). Ceaușescu rose up through the ranks of

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (; 8 November 1901 – 19 March 1965) was a Romanian communist politician and electrician. He was the first Communist leader of Romania from 1947 to 1965, serving as first secretary of the Romanian Communist Party ( ...

's Socialist government and, upon Gheorghiu-Dej's death in 1965, he succeeded to the leadership of the Romanian Communist Party as general secretary.

Upon achieving power, Ceaușescu eased

press censorship and condemned the

Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

in his

speech of 21 August 1968, which resulted in a surge in popularity. However, this period of stability was brief, as his government soon became

totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regul ...

and came to be considered the most repressive in the

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

. His

secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

, the

Securitate, was responsible for

mass surveillance

Mass surveillance is the intricate surveillance of an entire or a substantial fraction of a population in order to monitor that group of citizens. The surveillance is often carried out by local and federal governments or governmental organizati ...

as well as

severe repression and human rights abuses within the country, and controlled the media and press. Ceaușescu's attempts to implement

policies that would lead to a significant growth of the population led to a growing number of illegal abortions and increased the number of orphans in state institutions. Economic mismanagement due to failed oil ventures during the 1970s led to very significant foreign debts for Romania. In 1982, Ceaușescu directed the government to export much of the country's agricultural and industrial production in an effort to repay these debts.

His cult of personality experienced unprecedented elevation, followed by the deterioration of foreign relations, even with the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

.

As anti-government protesters demonstrated in

Timișoara in December 1989, Ceaușescu perceived the demonstrations as a political threat and ordered military forces to open fire on 17 December, causing many deaths and injuries. The revelation that Ceaușescu was responsible resulted in a massive spread of rioting and civil unrest across the country. The demonstrations, which reached

Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

, became known as the

Romanian Revolution—the only violent overthrow of a communist government in the course of the

Revolutions of 1989

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Natio ...

. Ceaușescu and his wife

Elena fled the capital in a helicopter, but they were captured by the military after the armed forces defected. After being

tried and convicted of economic sabotage and

genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

, both were sentenced to death, and they were immediately

executed by firing squad on 25 December.

Early life and career

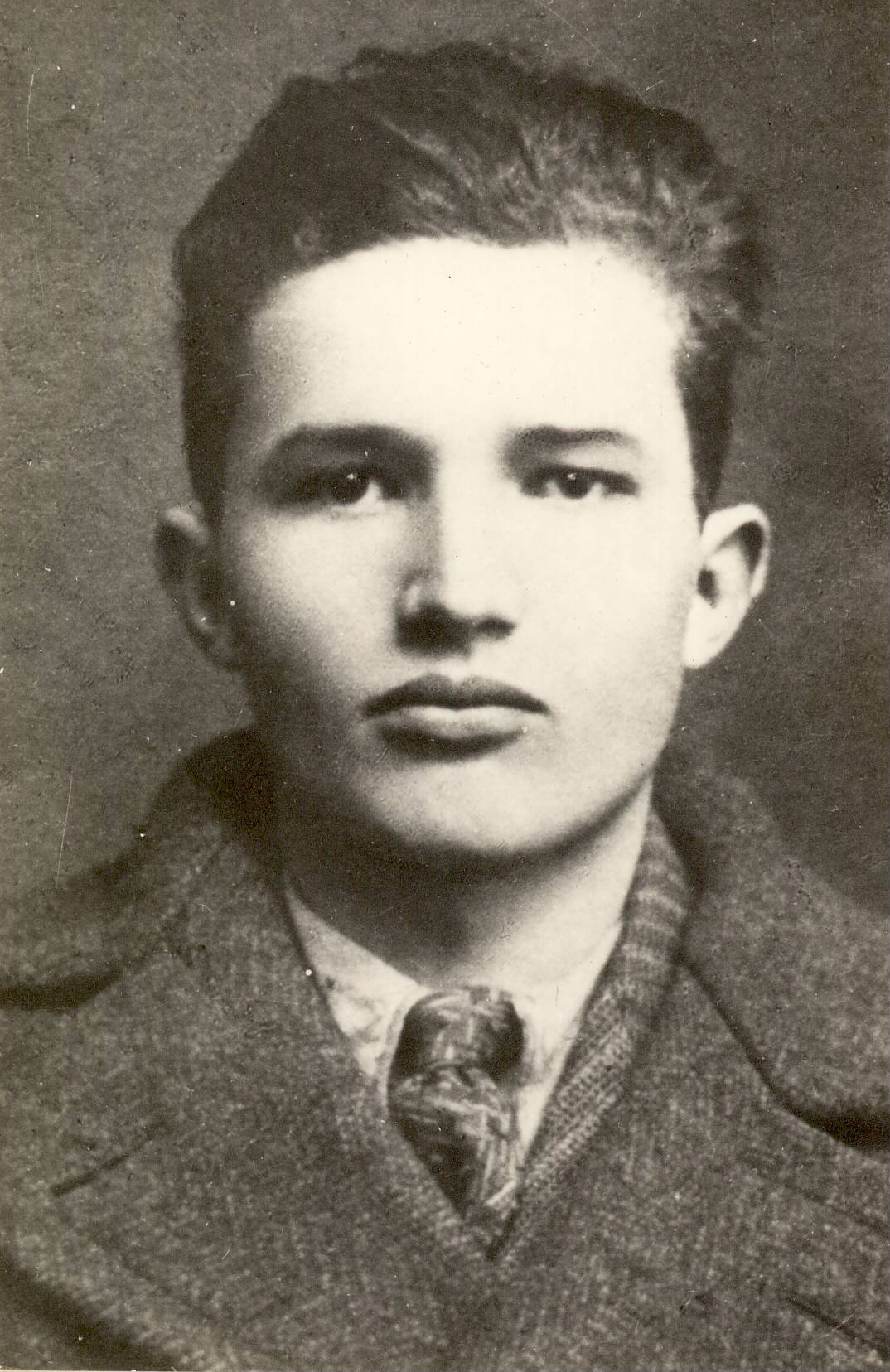

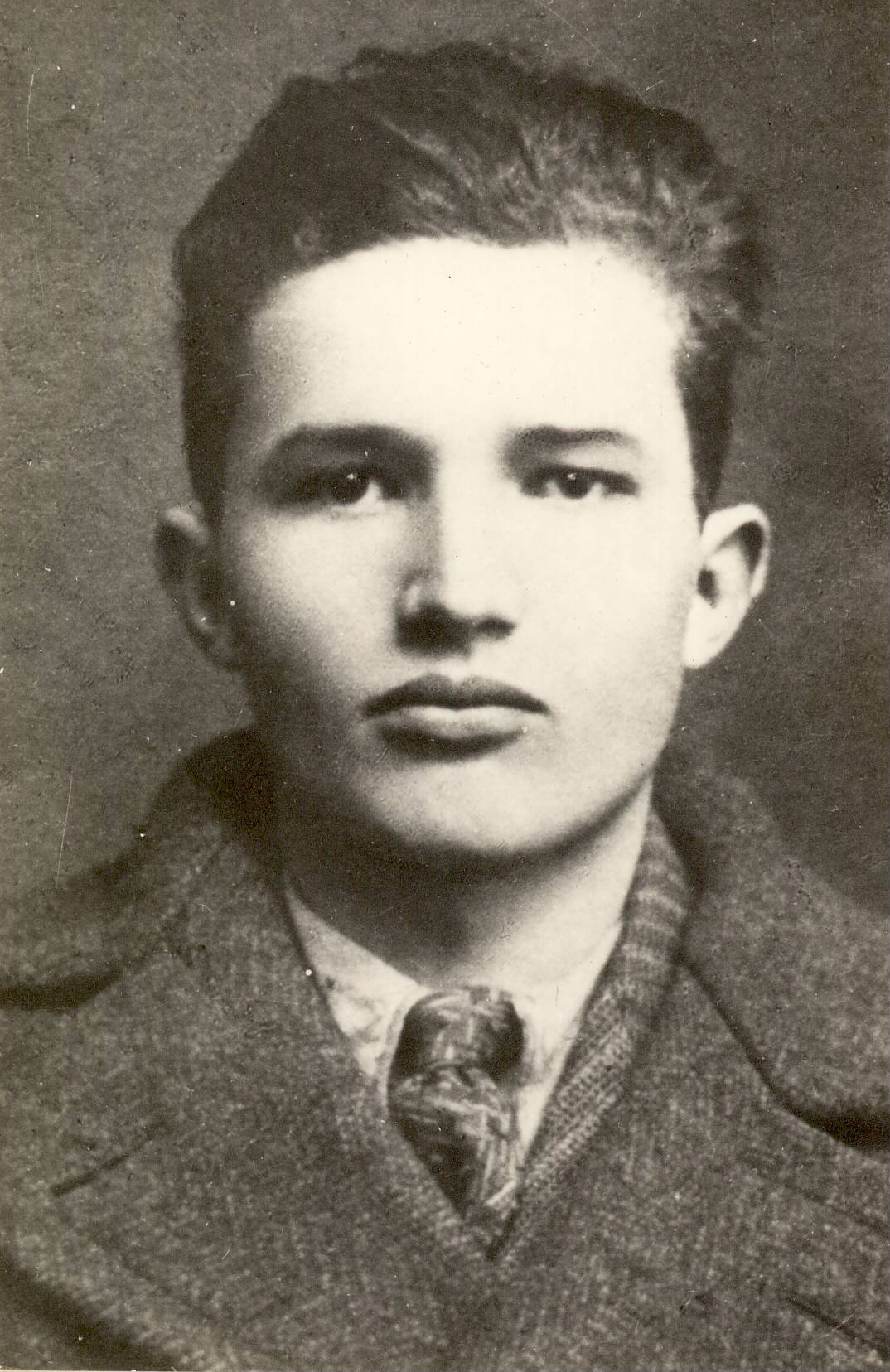

Ceaușescu was born in the small village of

Scornicești,

Olt County, being the third of nine children of a poor peasant family (see

Ceaușescu family). Based on his birth certificate, he was born on , rather than the official —his birth was registered with a three-day delay, which later led to confusion. According to the information recorded in his autobiography, Nicolae Ceaușescu was born on 26 January 1918.

His father Andruță (1886–1969) owned of agricultural land and a few sheep, and Nicolae supplemented his large family's income through tailoring.

He studied at the village school until the age of 11, when he left for

Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

. The Olt County Service of National Archives holds excerpts from the catalogs of Scornicești Primary School, which certifies that Nicolae A. Ceaușescu passed the first grade with an average of 8.26 and the second grade with an average of 8.18, ranking third, in a class in which 25 students were enrolled.

Journalist Cătălin Gruia claimed in 2007 that he ran away from his supposedly extremely religious, abusive and strict father. He initially lived with his sister, Niculina Rusescu.

He became an

apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

shoemaker

Shoemaking is the process of making footwear.

Originally, shoes were made one at a time by hand, often by groups of shoemakers, or cobblers (also known as '' cordwainers''). In the 18th century, dozens or even hundreds of masters, journeymen ...

,

working in the workshop of Alexandru Săndulescu, a shoemaker who was an active member in the then-illegal Communist Party.

Ceaușescu was soon involved in the Communist Party activities (becoming a member in early 1932), but as a teenager he was given only small tasks.

He was first arrested in 1933, at the age of 15, for street fighting during a strike and again, in 1934, first for collecting signatures on a petition protesting against the trial of railway workers and twice more for other similar activities.https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/qfp/104481.htm By the mid-1930s, he had been in missions in Bucharest,

Craiova

Craiova (, also , ), is Romania's 6th Cities in Romania, largest city and capital of Dolj County, and situated near the east bank of the river Jiu River, Jiu in central Oltenia. It is a longstanding political center, and is located at approximatel ...

,

Câmpulung

Câmpulung (also spelled ''Cîmpulung'', , german: Langenau, Old Romanian ''Dlăgopole'', ''Длъгополе'' (from Middle Bulgarian)), or ''Câmpulung Muscel'', is a municipality in the Argeș County, Muntenia, Romania. It is situated among t ...

and

Râmnicu Vâlcea, being arrested several times.

[Gruia, p. 43]

The profile file from the secret police,

Siguranța Statului

Siguranța was the generic name for the successive secret police services in the Kingdom of Romania. The official title of the organization changed throughout its history, with names including Directorate of the Police and General Safety ( ro, Di ...

, named him "a dangerous Communist agitator" and "distributor of Communist and antifascist propaganda materials".

For these charges, he was convicted on 6 June 1936 by the Brașov Tribunal to 2 years in prison, an additional 6 months for

contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the cour ...

, and one year of forced residence in Scornicești.

He spent most of his sentence in

Doftana Prison

Doftana was a Romanian prison, sometimes referred to as "the Romanian Bastille". Built in 1895 in connection with the nearby salt mines, from 1921 it began to be used to detain political prisoners, among them Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, who was the Pr ...

.

While out of jail in 1939, he met

Elena Petrescu, whom he married in 1946 and who would play an increasing role in his political life over the years.

Soon after being freed, he was arrested again and sentenced for "conspiracy against social order", spending the time during the war in prisons and

internment camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

s:

Jilava (1940),

Caransebeș (1942),

Văcărești (1943), and Târgu Jiu (1943).

In 1943, he was transferred to

Târgu Jiu

Târgu Jiu () is the capital of Gorj County in the Oltenia region of Romania. It is situated on the Southern Sub-Carpathians, on the banks of the river Jiu. Eight localities are administered by the city: Bârsești, Drăgoieni, Iezureni, Polata, ...

internment camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

, where he shared a cell with

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (; 8 November 1901 – 19 March 1965) was a Romanian communist politician and electrician. He was the first Communist leader of Romania from 1947 to 1965, serving as first secretary of the Romanian Communist Party ( ...

, becoming his protégé.

Enticed with substantial bribes, the camp authorities gave the Communist prisoners much freedom in running their cell block, provided they did not attempt to break out of prison. At Târgu Jiu, Gheorghiu-Dej ran "

self-criticism sessions" where various Party members had to confess before the other Party members to misunderstanding the teachings of

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

,

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,["Engels"](_blank)

'' Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

, and

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

as interpreted by Gheorghiu-Dej; journalist

Edward Behr claimed that Ceaușescu's role in these "self-criticism sessions" was that of the enforcer, the young man allegedly beating those Party members who refused to go with or were insufficiently enthusiastic about the "self-criticism" sessions.

[Behr, Edward ''Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite'', New York: Villard Books, 1991 pp. 181–186.] These "self-criticism sessions" not only helped to cement Gheorghiu-Dej's control over the Party, but also endeared his protégé Ceaușescu to him.

It was Ceaușescu's time at Târgu Jiu that marked the beginning of his rise to power. After

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, when Romania was beginning to fall under

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

influence, Ceaușescu served as secretary of the

Union of Communist Youth (1944–1945).

After the Communists seized power in Romania in 1947, and under the patronage of Gheorghiu-Dej, Ceaușescu was elected a member of the

Great National Assembly, the new legislative body of communist Romania.

In May 1948, Ceaușescu was appointed Secretary of the Ministry of Agriculture, and in March 1949 he was promoted to the position of Deputy Minister. From the Ministry of Agriculture and with no military experience, he was made Deputy Minister in charge of the armed forces, holding the rank of Major General. Later, promoted to the rank of lieutenant general, he became First Deputy to the Ministry of Defense and head of the Army's Higher Political Directorate.

Ceaușescu studied at the Soviet

Frunze Military Academy

The M. V. Frunze Military Academy (russian: Военная академия имени М. В. Фрунзе), or in full the Military Order of Lenin and the October Revolution, Red Banner, Order of Suvorov Academy in the name of M. V. Frunze (rus ...

in Moscow for two consecutive months in both 1951 and 1952.

In 1952, Gheorghiu-Dej brought him onto the

Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of Communist party, communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party org ...

months after the party's "Muscovite faction" led by

Ana Pauker had been purged. In the late 1940s-early 1950s, the Party had been divided into the "home communists" headed by Gheorghiu-Dej who remained inside Romania prior to 1944 and the "Muscovites" who had gone into exile in the Soviet Union. With the partial exception of Poland, where the

Polish October crisis of 1956 brought to power the previously imprisoned "home communist"

Władysław Gomułka, Romania was the only Eastern European nation where the "home communists" triumphed over the "Muscovites". In the rest of the Soviet bloc, there were a series of purges in this period that led to the "home communists" being executed or imprisoned. Like his patron Gheorghiu-Dej, Ceaușescu was a "home communist" who benefited from the fall of the "Muscovites" in 1952. In 1954, Ceaușescu became a full member of the Politburo, effectively granting him one of the highest positions of power in the country.

Ceaușescu during the collectivization process

As a high-ranking state official in the Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Defence Ceaușescu had an important role in the forced collectivisation, according to own

Romanian Workers' Party

The Romanian Communist Party ( ro, Partidul Comunist Român, , PCR) was a communist party in Romania. The successor to the pro-Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave ideological endorsement to a communist revolution that woul ...

data, between 1949 and 1952 there were over 80,000 arrests of peasants and 30,000 ended with prison sentences.

One example is the uprising of

Vadu Roșca (Vrancea county) which opposed the state program of expropriation of private holdings, when military units opened fire on the rebelling peasants, killing 9 and wounding 48. Ceaușescu personally led the investigation which resulted in 18 peasants being imprisoned for "rebellion" and "conspiring against social order".

Leadership of Romania

When Gheorghiu-Dej died on 19 March 1965, Ceaușescu was not the obvious successor, despite his closeness to the longtime leader. But widespread infighting by older and more connected officials led the Politburo to choose Ceaușescu as a compromise candidate.

He was elected general secretary on 22 March 1965, three days after Gheorghiu-Dej's death.

One of Ceaușescu's first acts was to change the name of the party from the Romanian Workers' Party back to the

Communist Party of Romania and to declare the country a

socialist republic

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ec ...

, rather than a

people's republic. In 1967, he consolidated his power by becoming president of the

State Council State Council may refer to:

Government

* State Council of the Republic of Korea, the national cabinet of South Korea, headed by the President

* State Council of the People's Republic of China, the national cabinet and chief administrative auth ...

, making him ''de jure'' head of state. His political apparatus sent many thousands of political opponents to prison or psychiatric hospitals.

Initially, Ceaușescu became a popular figure, both in Romania and in the West, because of his independent foreign policy, which challenged the authority of the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. In the 1960s, he eased press censorship and ended Romania's active participation in the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republic ...

, but Romania formally remained a member. He refused to take part in the

1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

by Warsaw Pact forces and even actively and openly condemned it in his

21 August 1968 speech. He travelled to

Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

a week before the invasion to offer moral support to his Czechoslovak counterpart,

Alexander Dubček. Although the Soviet Union largely tolerated Ceaușescu's recalcitrance, his seeming independence from Moscow earned Romania maverick status within the

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

.

[

All of Ceaușescu's economic, foreign and demographic policies were meant to achieve his ultimate goal: turning Romania into one of the world's great powers.][Crampton, Richard ''Eastern Europe In the Twentieth Century – And After'', London: Routledge, 1997 p. 355.] In October 1966, Ceaușescu banned abortion and contraception and imposed one of the world's harshest anti-abortion laws, leading to a spike in the number of Romanian infants turned over to the country's orphanages.

During the following years, Ceaușescu pursued an open policy towards the United States and Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Romania was the first Warsaw Pact country to recognize West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

, the first to join the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster globa ...

, and the first to receive a US president, Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

. In 1971, Romania became a member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is a legal agreement between many countries, whose overall purpose was to promote international trade by reducing or eliminating trade barriers such as tariffs or quotas. According to its pre ...

. Romania and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

were also the only Eastern European countries that entered into trade agreements with the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

before the fall of the Eastern Bloc.

A series of official visits to Western countries (including the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Spain and Australia) helped Ceaușescu to present himself as a reforming Communist, pursuing an independent foreign policy within the Soviet Bloc. He also became eager to be seen as an enlightened international statesman, able to mediate in international conflicts, and to gain international respect for Romania. Ceaușescu negotiated in international affairs, such as the opening of US relations with China in 1969 and the visit of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

ian president Anwar Sadat

Muhammad Anwar el-Sadat, (25 December 1918 – 6 October 1981) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the third president of Egypt, from 15 October 1970 until his assassination by fundamentalist army officers on 6 ...

to Israel in 1977. In addition, Romania was the only country in the world to maintain normal diplomatic relations with both Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establ ...

. In 1980, Romania participated in the 1980 Summer Olympics

The 1980 Summer Olympics (russian: Летние Олимпийские игры 1980, Letniye Olimpiyskiye igry 1980), officially known as the Games of the XXII Olympiad (russian: Игры XXII Олимпиады, Igry XXII Olimpiady) and commo ...

in Moscow with its other Soviet bloc allies, but in 1984 was one of the few Communist countries to participate in the 1984 Summer Olympics

The 1984 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXIII Olympiad and also known as Los Angeles 1984) were an international multi-sport event held from July 28 to August 12, 1984, in Los Angeles, California, United States. It marked the secon ...

in Los Angeles (going on to win 53 medals, trailing only the United States and West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

in the overall count) Ceaușescu refused to implement measures of economic liberalism. The evolution of his regime followed the path begun by Gheorghiu-Dej. He continued with the program of intensive

Ceaușescu refused to implement measures of economic liberalism. The evolution of his regime followed the path begun by Gheorghiu-Dej. He continued with the program of intensive industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

aimed at the economic self-sufficiency

Self-sustainability and self-sufficiency are overlapping states of being in which a person or organization needs little or no help from, or interaction with, others. Self-sufficiency entails the self being enough (to fulfill needs), and a self-s ...

of the country which since 1959 had already doubled industrial production and had reduced the peasant population from 78% at the end of the 1940s to 61% in 1966 and 49% by 1971. However, for Romania, like other Eastern People's Republics, industrialization did not mean a total social break with the countryside. The peasants returned periodically to the villages or resided in them, commuting daily to the city in a practice called naveta. This allowed Romanians to act as peasants and workers at the same time.[The contradictions between domestic and foreign policies in the Cold War Romania (1956–1975), Ferrero, M.D, 2006, Historia Actual Online]

Universities were also founded in small Romanian towns, which served to train qualified professionals such as engineers, economists, planners or jurists necessary for the industrialization and development project of the country. Romanian healthcare also achieved improvements and recognition by the World Health Organization (WHO). In May 1969, Marcolino Candau, Director General of this organization, visited Romania and declared that the visits of WHO staff to various Romanian hospital establishments had made an extraordinarily good impression.

1966 decree

In 1966, in an attempt to boost the country's population, Ceaușescu made abortion illegal and introduced Decree 770

Decree 770 was a decree of the communist Romanian government of Nicolae Ceaușescu, signed in 1967. It restricted abortion and contraception, and was intended to create a new and large Romanian population. The term (from the Romanian language wor ...

in order to reverse the Romanian population's low birth and fertility rates. Mothers of at least five children were entitled to receive significant benefits, while mothers of at least ten children were declared "heroine mothers" by the Romanian state.

The government targeted rising divorce rates and made divorce more difficult—it was decreed that marriages could only be dissolved in exceptional cases. By the late 1960s, the population began to swell. In turn, a new problem was created, child abandonment, which swelled the orphanage population (see Cighid

Cighid was a children's home in Romania where many orphans and disabled youths were held in inhumane conditions. The extent of the abuse was exposed in March 1990, shortly after the fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu's regime.

Background information

In 1 ...

). Many of the children in these orphanages suffered mental and physical deficiencies.

Measures to encourage reproduction included financial motivations for families who bore children, guaranteed maternity leave, and childcare support for mothers who returned to work, work protection for women, and extensive access to medical control in all stages of pregnancy, as well as after it. Medical control was seen as one of the most productive effects of the law, since all women who became pregnant were under the care of a qualified medical practitioner, even in rural areas. In some cases, if a woman was unable to visit a medical office, a doctor would visit her home.

Speech of 21 August 1968

Ceaușescu's speech of 21 August 1968 represented the apogee of Ceaușescu's rule. It marked the highest point in Ceaușescu's popularity, when he openly condemned the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

.

July Theses

Ceaușescu visited China, North Korea, Mongolia and North Vietnam in 1971. He took great interest in the idea of total national transformation as embodied in the programmes of North Korea's '' Juche'' and China's Cultural Revolution. He was also inspired by the personality cults of North Korea's

Ceaușescu visited China, North Korea, Mongolia and North Vietnam in 1971. He took great interest in the idea of total national transformation as embodied in the programmes of North Korea's '' Juche'' and China's Cultural Revolution. He was also inspired by the personality cults of North Korea's Kim Il Sung

Kim Il-sung (; , ; born Kim Song-ju, ; 15 April 1912 – 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he ruled from the country's establishment in 1948 until his death in 1994. He held the posts of ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

's Mao Zedong. Journalist Edward Behr claimed that Ceaușescu admired both Mao and Kim as leaders who not only totally dominated their nations but had also used totalitarian methods coupled with significant ultra-nationalism mixed in with communism in order to transform both China and North Korea into major world powers.[Behr, Edward ''Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite'', New York: Villard Books, 1991 p. 195.] Furthermore, that Kim and even more so Mao had broken free of Soviet control were additional sources of admiration for Ceaușescu. According to British journalist Edward Behr, Elena Ceaușescu allegedly bonded with Mao's wife, Jiang Qing.Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

and widely distributed inside the country.

On 6 July 1971, he delivered a speech before the executive committee of the Romanian Communist Party. This quasi- Maoist speech, which came to be known as the July Theses, contained seventeen proposals. Among these were: continuous growth in the "leading role" of the Party; improvement of Party education and of mass political action; youth participation on large construction projects as part of their "patriotic work"; an intensification of political-ideological education in schools and universities, as well as in children's, youth and student organizations; and an expansion of political propaganda, orienting radio and television shows to this end, as well as publishing houses, theatres and cinemas, opera, ballet, artists' unions, promoting a "militant, revolutionary" character in artistic productions. The liberalization of 1965 was condemned and an index of banned books and authors was re-established.

The Theses heralded the beginning of a "mini cultural revolution" in Romania, launching a Neo-Stalinist

Neo-Stalinism (russian: Неосталинизм) is the promotion of positive views of Joseph Stalin's role in history, the partial re-establishing of Stalin's policies on certain issues and nostalgia for the Stalin period. Neo-Stalinism over ...

offensive against cultural autonomy, reaffirming an ideological basis for literature that, in theory, the Party had hardly abandoned. Although presented in terms of "Socialist Humanism", the Theses in fact marked a return to the strict guidelines of Socialist Realism and attacks on non-compliant intellectuals. Strict ideological conformity in the humanities and social sciences was demanded.

In a 1972 speech, Ceaușescu stated he wanted "a certain blending of party and state activities... in the long run we shall witness an ever closer blending of the activities of the party, state and other social bodies". In practice, a number of joint party-state organizations were founded such as the Council for Socialist Education and Culture, which had no precise counterpart in any of the other communist states of Eastern Europe, and the Romanian Communist Party was embedded into the daily life of the nation in a way that it never had been before. In 1974, the party programme of the Romanian Communist Party announced that structural changes in society were insufficient to create a full socialist consciousness in the people, and that a full socialist consciousness could only come about if the entire population was made aware of socialist values that guided society. The Communist Party was to be the agency that would so "enlighten" the population and in the words of the British historian Richard Crampton "...the party would merge state and society, the individual and the collective, and would promote 'the ever more organic participation of party members in the entire social life'".

President of the Socialist Republic of Romania

In 1974, Ceaușescu converted his post of president of the State Council to a full-fledged executive presidency. He was first elected to this post in 1974 and would be reelected every five years until 1989.

Although Ceaușescu had been nominal head of state since 1967, he had merely been first among equals on the State Council, deriving his real power from his status as party leader. The new post, however, made him the nation's top decision-maker both in name and in fact. He was empowered to carry out those functions of the State Council that did not require plenums. He also appointed and dismissed the president of the Supreme Court and the prosecutor general whenever the legislature was not in session. In practice, from 1974 onward Ceaușescu frequently ruled by decree. Over time, he usurped many powers and functions that nominally were vested in the State Council as a whole.

In 1974, Ceaușescu converted his post of president of the State Council to a full-fledged executive presidency. He was first elected to this post in 1974 and would be reelected every five years until 1989.

Although Ceaușescu had been nominal head of state since 1967, he had merely been first among equals on the State Council, deriving his real power from his status as party leader. The new post, however, made him the nation's top decision-maker both in name and in fact. He was empowered to carry out those functions of the State Council that did not require plenums. He also appointed and dismissed the president of the Supreme Court and the prosecutor general whenever the legislature was not in session. In practice, from 1974 onward Ceaușescu frequently ruled by decree. Over time, he usurped many powers and functions that nominally were vested in the State Council as a whole.

Oil embargo, strike and foreign relations

Starting with the 1973–74 Arab oil embargo against the West, a period of prolonged high oil prices set in that characterised the rest of the 1970s. Romania as a major oil equipment producer greatly benefited from the high oil prices of the 1970s, which led Ceaușescu to embark on an ambitious plan to invest heavily in oil-refining plants. Ceaușescu's plan was to make Romania into Europe's number one oil refiner not only of its own oil, but also of oil from Middle Eastern states such as Iraq and Iran, and then to sell all of the refined oil at a profit on the Rotterdam spot market.

Starting with the 1973–74 Arab oil embargo against the West, a period of prolonged high oil prices set in that characterised the rest of the 1970s. Romania as a major oil equipment producer greatly benefited from the high oil prices of the 1970s, which led Ceaușescu to embark on an ambitious plan to invest heavily in oil-refining plants. Ceaușescu's plan was to make Romania into Europe's number one oil refiner not only of its own oil, but also of oil from Middle Eastern states such as Iraq and Iran, and then to sell all of the refined oil at a profit on the Rotterdam spot market.[Crampton, Richard ''Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century – And After'', London: Routledge, 1997 p. 356.] As Romania lacked the money to build the necessary oil refining plants and Ceaușescu chose to spend the windfall from the high oil prices on aid to the Third World in an attempt to buy Romania international influence, Ceaușescu borrowed heavily from Western banks on the assumption that when the loans came due, the profits from the sales of the refined oil would be more than enough to pay off the loans. In August 1977 over 30,000 miners went on strike in the Jiu River valley complaining of low pay and poor working conditions.

In August 1977 over 30,000 miners went on strike in the Jiu River valley complaining of low pay and poor working conditions. He continued to follow an independent policy in foreign relations—for example, in 1984, Romania was one of few communist states (notably including the People's Republic of China and

He continued to follow an independent policy in foreign relations—for example, in 1984, Romania was one of few communist states (notably including the People's Republic of China and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

) to take part in the 1984 Summer Olympics

The 1984 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXIII Olympiad and also known as Los Angeles 1984) were an international multi-sport event held from July 28 to August 12, 1984, in Los Angeles, California, United States. It marked the secon ...

in Los Angeles, despite a Soviet-led boycott.

Also, the Socialist Republic of Romania was the first of the

Also, the Socialist Republic of Romania was the first of the Eastern bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

nations to have official relations with the Western bloc and the European Community: an agreement including Romania in the Community's Generalised System of Preferences was signed in 1974 and an Agreement on Industrial Products was signed in 1980. On 4 April 1975, Ceaușescu visited Japan and met with Emperor Hirohito. In June 1978, Ceaușescu made a state visit to the UK where a £200m licensing agreement was signed between the Romanian government and British Aerospace for the production of more than eighty BAC One-Eleven

The BAC One-Eleven (or BAC-111/BAC 1-11) was an early jet airliner produced by the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC).

Originally conceived by Hunting Aircraft as a 30-seat jet, before its merger into BAC in 1960, it was launched as an 80-se ...

aircraft. The deal was said at the time to be the biggest between two countries involving a civil aircraft. This was the first state visit by a Communist head of state to the UK, and Ceaușescu was given a knighthood by the Queen, which was revoked on the day before his death in 1989. Similarly, in 1983, Vice President of the United States George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

and in 1985 United States Secretary of State George Shultz

George Pratt Shultz (; December 13, 1920February 6, 2021) was an American economist, businessman, diplomat and statesman. He served in various positions under two different Republican presidents and is one of the only two persons to have held fou ...

also praised the Romanian dictator.

Pacepa defection

In 1978, Ion Mihai Pacepa

Ion Mihai Pacepa (; 28 October 1928 – 14 February 2021) was a Romanian two-star general in the Securitate, the secret police of the Socialist Republic of Romania, who defected to the United States in July 1978 following President Jimmy Carter' ...

, a senior member of the Romanian political police ( Securitate, State Security), defected to the United States. A two-star general, he was the highest-ranking defector from the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. His defection was a powerful blow against the administration, forcing Ceaușescu to overhaul Romania's state security architecture. Pacepa's 1986 book, ''Red Horizons: Chronicles of a Communist Spy Chief'' (), claimed to expose details of Ceaușescu's government activities, such as massive spying on American industry and elaborate efforts to rally Western political support.

Systematization: demolition and reconstruction

Systematization ( ro, Sistematizarea) was the program of urban planning carried out under Ceaușescu's regime. After a visit to North Korea in 1971, Ceaușescu was impressed by the '' Juche'' ideology of that country, and began a major campaign shortly afterwards.

Beginning in 1974, systematization consisted largely of the demolition and reconstruction of existing villages, towns, and cities, in whole or in part, with the stated goal of turning Romania into a "multilaterally developed

Systematization ( ro, Sistematizarea) was the program of urban planning carried out under Ceaușescu's regime. After a visit to North Korea in 1971, Ceaușescu was impressed by the '' Juche'' ideology of that country, and began a major campaign shortly afterwards.

Beginning in 1974, systematization consisted largely of the demolition and reconstruction of existing villages, towns, and cities, in whole or in part, with the stated goal of turning Romania into a "multilaterally developed socialist society

The Socialist Society was founded in 1981 by a group of British socialists, including Raymond Williams and Ralph Miliband, who founded it as an organisation devoted to socialist education and research, linking the left of the British Labour Party ...

". The policy largely consisted in the mass construction of high-density blocks of flats (''blocuri'').

During the 1980s, Ceaușescu became obsessed with building himself a palace

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence, or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word is derived from the Latin name palātium, for Palatine Hill in Rome which ...

of unprecedented proportions, along with an equally grandiose neighborhood, Centrul Civic

Centrul Civic (, ''the Civic Centre'') is a district in central Bucharest, Romania, which was completely rebuilt in the 1980s as part of the scheme of systematization under the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, which included the construction of new ...

, to accompany it. The mass demolitions that occurred in the 1980s under which an overall area of eight square kilometres of the historic center of Bucharest were leveled, including monasteries, churches, synagogues, a hospital, and a noted Art Deco sports stadium, in order to make way for the grandiose Centrul Civic

Centrul Civic (, ''the Civic Centre'') is a district in central Bucharest, Romania, which was completely rebuilt in the 1980s as part of the scheme of systematization under the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, which included the construction of new ...

(Civic center) and the House of the Republic, now officially renamed the Palace of Parliament

The Palace of the Parliament ( ro, Palatul Parlamentului), also known as the Republic's House () or People's House/People's Palace (), is the seat of the Parliament of Romania, located atop Dealul Spirii in Bucharest, the national capital. The ...

, were the most extreme manifestation of the systematization policy.

In 1988 massive rural resettlement program began.

Foreign debt

Ceaușescu's political independence from the Soviet Union and his protest against the

Ceaușescu's political independence from the Soviet Union and his protest against the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

drew the interest of Western powers, whose governments briefly believed that he was an anti-Soviet maverick and hoped to create a schism in the Warsaw Pact by funding him. Ceaușescu did not realise that the funding was not always favorable. Ceaușescu was able to borrow heavily (more than $13 billion) from the West to finance economic development programs, but these loans ultimately devastated the country's finances. He also secured a deal for cheap oil from Iran, but the deal fell through after the Shah was overthrown.

In an attempt to correct this, Ceaușescu decided to repay Romania's foreign debt

A country's gross external debt (or foreign debt) is the liabilities that are owed to nonresidents by residents. The debtors can be governments, corporations or citizens. External debt may be denominated in domestic or foreign currency. It incl ...

s. He organised the 1986 military referendum and managed to change the constitution, adding a clause that barred Romania from taking foreign loans in the future. According to official results, the referendum yielded a nearly unanimous "yes" vote.

Romania's record—having all of its debts to commercial banks paid off in full—has not been matched by any other heavily indebted country in the world. The policy to repay—and, in multiple cases, prepay—Romania's external debt became the dominant policy in the late 1980s. The result was economic stagnation throughout the 1980s and, towards the end of the decade, an economic crisis. The country's industrial capacity was eroded as equipment grew obsolete and energy intensity increased, and the standard of living deteriorated significantly. Draconian restrictions were imposed on household energy use to ensure adequate supplies for industry. Convertible currency exports were promoted at all costs and imports severely reduced. In 1988, real GDP contracted by 0.5%, mostly due to a decline in industrial output caused by significantly increased material costs. Despite the 1988 decline, the net foreign balance reached its decade-long peak (9.5% of GDP). In 1989, GDP slumped by a further 5.8% due to growing shortages and the increasingly obsolete capital stock. By March 1989, virtually all external debt had been repaid, including all medium- and long-term external debt. The remaining amount, totalling less than 1 million, consisted of short-term credits (mainly short-term export credits granted by Romania). A 1989 decree legally prohibited Romanian entities from contracting external debt. The CIA World Factbook

''The World Factbook'', also known as the ''CIA World Factbook'', is a reference resource produced by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with almanac-style information about the countries of the world. The official print version is available ...

edition of 1990 listed Romania's external debt as "none" as of mid-1989.

Yearly evolution (in billions of dollars)

* 1995 was the last year in which Romania's economy was dominated by the state. From 1996 onwards, the private sector would account for most of Romania's GDP.

* Data for 1975, 1980 and 1982–1988 taken from the ''Statistical Abstract of the United States''.

* Data for 1989–1995 provided by the OECD.

1984 failed coup d'état attempt

A tentative coup d'état planned in October 1984 failed when the military unit assigned to carry out the plan was sent to harvest maize instead.

1987 Brașov rebellion

Romanian workers began to mobilize against the economic policies of Ceaușescu. Spontaneous labor conflicts, limited in scale, took place in major industrial centers such as

Romanian workers began to mobilize against the economic policies of Ceaușescu. Spontaneous labor conflicts, limited in scale, took place in major industrial centers such as Cluj-Napoca

; hu, kincses város)

, official_name=Cluj-Napoca

, native_name=

, image_skyline=

, subdivision_type1 = Counties of Romania, County

, subdivision_name1 = Cluj County

, subdivision_type2 = Subdivisions of Romania, Status

, subdivision_name2 ...

(November 1986) and the Nicolina platform in Iași

Iași ( , , ; also known by other alternative names), also referred to mostly historically as Jassy ( , ), is the second largest city in Romania and the seat of Iași County. Located in the historical region of Moldavia, it has traditionally ...

(February 1987), culminating in a massive strike in Brașov. The draconian measures taken by Ceaușescu involved reducing energy and food consumption, as well as lowering workers' incomes, leading to what political scientist Vladimir Tismăneanu called "generalized dissatisfaction".

Over 20,000 workers and a number of townspeople marched against economic policies

The economy of governments covers the systems for setting levels of taxation, government budgets, the money supply and interest rates as well as the labour market, national ownership, and many other areas of government interventions into the e ...

in Socialist Romania

The Socialist Republic of Romania ( ro, Republica Socialistă România, RSR) was a Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist state that existed officially in Romania from 1947 to 1989. From 1947 to 1965, the state was known as the Romanian People ...

and Nicolae Ceaușescu's policies of rationing of basic foodstuffs, rationing electricity and central heating.

The first protests began practically on 14 November 1987, at the 440 "Molds" Section of the Red Flag truck company. Initially, the protests were for basic needs: "We want food and heating!", "We want our money!", "We want food for the children!", "We want light and heat!" and "We want bread without a card!". Next to the County Hospital, they sang the anthem of the revolution of 1848, " Deșteaptă-te, române!". Upon arriving in the city center, thousands of workers from the Tractorul Brașov and Hidromecanica factories, pupils, students, and others joined the demonstration. From this moment on, the protest became political. Participants later claimed to have chanted slogans such as "Down with Ceaușescu!", "Down with communism!", "Down with the dictatorship!" or "Down with the tyrant!". During the march, members of the Securitate disguised as workers infiltrated the demonstrators, or remained on the sidelines as spectators, photographing or even filming.[Ruxandra Cesereanu: ''"Decembrie '89. Deconstrucția unei revoluții"'', Ediția a II-a revăzută și adăugită (Polirom, Iași, 2009), pp. 25, 26, 31, 32, 34, 38, 39, 40]

By dusk, Securitate forces and the military surrounded the city center and disbanded the revolt by force. Some 300 protesters were arrested, and, in order to hide the political nature of the Brașov uprising, tried for disturbing the peace and "outrage against morals".

Those under investigation were beaten and tortured, 61 receiving sentences ranging from 6 months to 3 years in prison, including sentences to be carried out working at various state enterprises across in the country. Although many previous party meetings had called for the death penalty to set an example, the regime was eager to downplay the uprising as "isolated cases of hooliganism". Protesters were sentenced to deportation, with compulsory residence arranged in other cities, despite such measures having been repealed as far back as the late 1950s. The entire trial lasted only an hour and a half.

Those under investigation were beaten and tortured, 61 receiving sentences ranging from 6 months to 3 years in prison, including sentences to be carried out working at various state enterprises across in the country. Although many previous party meetings had called for the death penalty to set an example, the regime was eager to downplay the uprising as "isolated cases of hooliganism". Protesters were sentenced to deportation, with compulsory residence arranged in other cities, despite such measures having been repealed as far back as the late 1950s. The entire trial lasted only an hour and a half.

Romani minority rights

Under the Ceaușescu regime, Romani people in Romania were largely neglected. This can be seen, perhaps most blatantly, in a motion from the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Romanian Workers Party, which largely laid the foundation for the Ceaușescu regime's policies regarding the rights of ethnic minorities. The motion entirely ignored the Romani.Ion Antonescu

Ion Antonescu (; ; – 1 June 1946) was a Romanian military officer and marshal who presided over two successive wartime dictatorships as Prime Minister and ''Conducător'' during most of World War II.

A Romanian Army career officer who made ...

.hate crime

A hate crime (also known as a bias-motivated crime or bias crime) is a prejudice-motivated crime which occurs when a perpetrator targets a victim because of their membership (or perceived membership) of a certain social group or racial demograph ...

s in the country. Such conditions exist in modern-day Romania, as demonstrated by the policies of several subsequent presidents.

Revolution

In November 1989, the XIVth Congress of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) saw Ceaușescu, then aged 71, re-elected for another five years as leader of the PCR. During the Congress, Ceaușescu made a speech denouncing the anti-Communist revolutions happening throughout the rest of Eastern Europe. The following month, Ceaușescu's government itself collapsed after a series of violent events in Timișoara and

In November 1989, the XIVth Congress of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) saw Ceaușescu, then aged 71, re-elected for another five years as leader of the PCR. During the Congress, Ceaușescu made a speech denouncing the anti-Communist revolutions happening throughout the rest of Eastern Europe. The following month, Ceaușescu's government itself collapsed after a series of violent events in Timișoara and Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

.

Czechoslovak President Gustáv Husák's resignation on 10 December 1989 amounted to the fall of the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia, leaving Ceaușescu's Romania as the only remaining hard-line Communist regime in the Warsaw Pact.

Timișoara

Demonstrations in the city of Timișoara were triggered by the government-sponsored attempt to evict László Tőkés, an ethnic Hungarian pastor, accused by the government of inciting ethnic hatred. Members of his ethnic Hungarian congregation

A congregation is a large gathering of people, often for the purpose of worship.

Congregation may also refer to:

*Church (congregation), a Christian organization meeting in a particular place for worship

*Congregation (Roman Curia), an administra ...

surrounded his apartment in a show of support.

Romanian students spontaneously joined the demonstration, which soon lost nearly all connection to its initial cause and became a more general anti-government demonstration. Regular military forces, police, and the Securitate fired on demonstrators on 17 December 1989, killing and injuring men, women, and children.

On 18 December 1989, Ceaușescu departed for a state visit to Iran, leaving the duty of crushing the Timișoara revolt to his subordinates and his wife. Upon his return to Romania on the evening of 20 December, the situation became even more tense, and he gave a televised speech from the TV studio inside the Central Committee Building (CC Building), in which he spoke about the events at Timișoara in terms of an "interference of foreign forces in Romania's internal affairs" and an "external aggression on Romania's sovereignty".

The country, which had little to no information of the events transpiring in Timișoara from the national media, learned about the revolt from anti-communist radio stations that broadcast news in the Eastern Bloc throughout the Cold War (such as Voice of America and Radio Free Europe) and by word of mouth. On the next day, 21 December, Ceaușescu staged a mass meeting in Bucharest. Official media presented it as a "spontaneous movement of support for Ceaușescu", emulating the 1968 meeting in which he had spoken against the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces.

Overthrow

Speech on 21 December

The mass meeting of 21 December, held in what is now Revolution Square, began like many of Ceaușescu's speeches over the years. He spoke of the achievements of the "Socialist revolution" and Romania's "multi-laterally developed Socialist society". He also blamed the Timișoara riots on "fascist agitators who want to destroy socialism".

However, Ceaușescu had misjudged the crowd's mood. Roughly eight minutes into his speech, several people began jeering and booing, and others began chanting " Timișoara!" He tried to silence them by raising his right hand and calling for the crowd's attention before order was temporarily restored, then proceeded to announce social benefit reforms that included raising the national minimum wage by 200 lei per month to a total of 2,200 per month by 1 January. Images of Ceaușescu's facial expression as the crowd began to boo and heckle him were among the most widely broadcast of the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe.

Flight on 22 December

By the morning of 22 December, the rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

had already spread to all major cities across the country. The suspicious death of Vasile Milea, Ceaușescu's defence minister

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

, later confirmed as a suicide (he tried to incapacitate himself with a flesh wound but a bullet severed his artery), was announced by the media. Immediately thereafter, Ceaușescu presided over the CPEx (Political Executive Committee) meeting and assumed the leadership of the army. Believing that Milea had been murdered, rank-and-file soldiers switched sides to the revolution almost ''en masse''. The commanders wrote off Ceaușescu as a lost cause and made no effort to keep their men loyal to the government. Ceaușescu made a last desperate attempt to address the crowd gathered in front of the Central Committee building, but the people in the square began throwing stones and other projectiles at him, forcing him to take refuge in the building once more. He, Elena and four others managed to get to the roof and escape by helicopter, only seconds ahead of a group of demonstrators who had followed them there.[ The ]Romanian Communist Party

The Romanian Communist Party ( ro, Partidul Comunist Român, , PCR) was a communist party in Romania. The successor to the pro-Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave ideological endorsement to a communist revolution that woul ...

disappeared soon afterwards; unlike its kindred parties in the former Soviet bloc, it has never been revived.

The Western press published estimates of the number of people killed by Securitate forces. The count increased rapidly until an estimated 64,000 fatalities were reported across front pages. The Hungarian military attaché expressed doubt regarding these figures, pointing out the unfeasible logistics of killing such a large number of people in such a short period. After Ceaușescu's death, hospitals across the country reported a death toll of fewer than 1,000, and probably much lower than that.

Death

Ceaușescu and his wife Elena fled the capital with Emil Bobu and

Ceaușescu and his wife Elena fled the capital with Emil Bobu and Manea Mănescu

Manea Mănescu (9 August 1916 – 27 February 2009) was a Romanian communist politician who served as Prime Minister for five years (27 February 1974 – 29 March 1979) during Nicolae Ceaușescu's Communist regime.

His father was a Communist Par ...

and flew by helicopter to Ceaușescu's Snagov

Snagov (population: 7,272) is a commune, located north of Bucharest, in Ilfov County, Muntenia, Romania. According to the 2011 census, 92% of the population is ethnic Romanian. The commune is composed of five villages: Ciofliceni, Ghermănești ...

residence, from which they fled again, this time to Târgoviște

Târgoviște (, alternatively spelled ''Tîrgoviște''; german: Tergowisch) is a city and county seat in Dâmbovița County, Romania. It is situated north-west of Bucharest, on the right bank of the Ialomița River.

Târgoviște was one of the ...

. They abandoned the helicopter near Târgoviște, having been ordered to land by the army, which by that time had restricted flying in Romania's airspace. The Ceaușescus were held by the police while the policemen listened to the radio. They were eventually handed over to the army.

On Christmas Day, 25 December 1989, the Ceaușescus were tried before a court convened in a small room on orders of the National Salvation Front, Romania's provisional government. They faced charges including illegal gathering of wealth and genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

. Ceaușescu repeatedly denied the court's authority to try him, and asserted he was still legally the President of Romania. At the end of the trial, the Ceaușescus were found guilty and sentenced to death. A soldier standing guard in the proceedings was ordered to take the Ceaușescus outside one by one and shoot them, but the Ceaușescus demanded to die together. The soldiers agreed to this and began to tie their hands behind their backs, which the Ceaușescus protested against, but were powerless to prevent.

The Ceaușescus were executed by a group of soldiers: Captain Ionel Boeru, Sergeant-Major Georghin Octavian and Dorin-Marian Cîrlan, and five other non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is a military officer who has not pursued a commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority by promotion through the enlisted ranks. (Non-officers, which includes most or all enli ...

s who were recruited from twenty volunteers. Before his sentence was carried out, Nicolae Ceaușescu sang " The Internationale" whilst being led towards the wall. The firing squad began shooting as soon as the two were in their positions up against the wall.

Later that day, the execution was also shown on Romanian television. The hasty show trial and the images of the dead Ceaușescus were videotaped and the footage released in numerous Western countries two days after the execution.

The manner in which the trial was conducted has been criticised. However, Ion Iliescu, Romania's provisional president, said in 2009 that the trial was "quite shameful, but necessary" in order to end the state of near-anarchy that had gripped the country in the three days since the Ceaușescus fled Bucharest.[ According to the '' Jurnalul Național'',]['' Jurnalul Național'', 25 January 2005] requests were made by the Ceaușescus' daughter, Zoia Zoia is both a given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

*Zoia Ceaușescu (1949–2006), Romanian mathematician

*Zoia Duriagina (born 1950), Ukrainian scientist

*Zoia Gaidai (1902–1965), Soviet Ukrainian opera so ...

, and by supporters of their political views, to move their remains to mausoleums or to purpose-built churches. These demands were denied by the government.

Exhumation and reburial

On 21 July 2010, forensic scientists exhumed the bodies to perform DNA tests to prove conclusively that they were indeed the remains of the Ceaușescus.[ and they were reburied together at Ghencea under a tombstone.

]

Ceaușescu's policies

While the term ''Ceaușism'' ( portmanteau of ''Ceaușescu'' and '' communism'') became widely used inside Romania, usually as a pejorative, it never achieved status in academia. This can be explained by the largely crude and syncretic character of the dogma. Ceaușescu attempted to include his views in mainstream Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

theory, to which he added his belief in a "multilaterally developed Socialist society" as a necessary stage between the Leninist concepts of Socialist and Communist societies (a critical view reveals that the main reason for the interval is the disappearance of the State and Party structures in Communism). A Romanian Encyclopedic Dictionary entry in 1978 underlines the concept as "a new, superior, stage in the Socialist development of Romania ... begun by the 1971–1975 Five-Year Plan, prolonged over several ucceeding and projectedFive-Year Plans".

Ceaușism's main trait was a form of Romanian nationalism, one which arguably propelled Ceaușescu to power in 1965, and probably led the Party leadership under Ion Gheorghe Maurer to select him over the more orthodox Gheorghe Apostol

Gheorghe Apostol (16 May 1913 – 21 August 2010) was a Romanian politician, deputy Prime Minister of Romania and a former leader of the Communist Party (PCR), noted for his rivalry with Nicolae Ceaușescu.

Early life

Apostol was born near T ...

. Although he had previously been a careful supporter of the official lines, Ceaușescu came to embody Romanian society's wish for independence after what many considered years of Soviet directives and purges, during and after the SovRom

The SovRoms (plural of ''SovRom'') were economic enterprises established in Romania following the communist takeover at the end of World War II, in place until 1954–1956 (when they were dissolved by the Romanian authorities).

In theory, SovRo ...

fiasco. He carried this nationalist option inside the Party, manipulating it against the nominated successor, Apostol. This nationalist policy had more timid precedents:[Geran Pilon, p. 60] for example, Gheorghiu-Dej had overseen the withdrawal of the Red Army in 1958.

It had also engineered the publishing of several works that subverted the Russian and Soviet image, no longer glossing over traditional points of tension with Russia and the Soviet Union (even alluding to an "unlawful" Soviet presence in Bessarabia). In the final years of Gheorghiu-Dej's rule, more problems were openly discussed, with the publication of a collection of Karl Marx's writings that dealt with Romanian topics, showing Marx's previously censored, politically uncomfortable views of Russia.

Ceaușescu was prepared to take a more decisive step in questioning Soviet policies. In the early years of his rule, he generally relaxed political pressures inside Romanian society, which led to the late 1960s and early 1970s being the most liberal decade in Socialist Romania. Gaining the public's confidence, Ceaușescu took a clear stand against the 1968 crushing of the

It had also engineered the publishing of several works that subverted the Russian and Soviet image, no longer glossing over traditional points of tension with Russia and the Soviet Union (even alluding to an "unlawful" Soviet presence in Bessarabia). In the final years of Gheorghiu-Dej's rule, more problems were openly discussed, with the publication of a collection of Karl Marx's writings that dealt with Romanian topics, showing Marx's previously censored, politically uncomfortable views of Russia.

Ceaușescu was prepared to take a more decisive step in questioning Soviet policies. In the early years of his rule, he generally relaxed political pressures inside Romanian society, which led to the late 1960s and early 1970s being the most liberal decade in Socialist Romania. Gaining the public's confidence, Ceaușescu took a clear stand against the 1968 crushing of the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Sec ...

by Leonid Brezhnev. After a visit from Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

earlier in the same year, during which the French President gave recognition to the incipient maverick, Ceaușescu's public speech in August deeply impressed the population, not only through its themes, but also because, uniquely, it was unscripted. He immediately attracted Western sympathies and backing, which lasted well beyond the 'liberal' phase of his rule; at the same time, the period brought forward the threat of armed Soviet invasion: significantly, many young men inside Romania joined the '' Patriotic Guards'' created on the spur of the moment, in order to meet the perceived threat. President Richard Nixon was invited to Bucharest in 1969, which was the first visit of a United States president to a communist country after the start of the Cold War.

Alexander Dubček's version of '' Socialism with a human face'' was never suited to Romanian Communist goals. Ceaușescu found himself briefly aligned with Dubček's Czechoslovakia and Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

's Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

. The latter friendship was to last until Tito's death in 1980, with Ceaușescu adapting the Titoist

Titoism is a political philosophy most closely associated with Josip Broz Tito during the Cold War. It is characterized by a broad Yugoslav identity, workers' self-management, a political separation from the Soviet Union, and leadership in the ...

doctrine of "independent Socialist development" to suit his own objectives. Romania proclaimed itself a "Socialist" (in place of "People's") Republic to show that it was fulfilling Marxist goals without Moscow's oversight, a move mirroring Communist Yugoslavia which renamed itself from a "Federal People's Republic" to a "Socialist Federal Republic" a few years earlier.

The system's nationalist traits grew and progressively blended with North Korean '' Juche'' and Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

Maoist ideals. In 1971, the Party, which had already been completely purged of internal opposition (with the possible exception of Gheorghe Gaston Marin),bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

''. The 1974 XIth Party Congress tightened the Party's grip on Romanian culture, guiding it towards Ceaușescu's nationalist principles.[Geran Pilon, p. 61] Notably, it demanded that Romanian historians refer to Dacians

The Dacians (; la, Daci ; grc-gre, Δάκοι, Δάοι, Δάκαι) were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of Dacia, located in the area near the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. They are often consid ...

as having "an unorganised State", part of a political continuum that culminated in the Socialist Republic.Turnu Severin

Drobeta-Turnu Severin (), colloquially Severin, is a city in Mehedinți County, Oltenia, Romania, on the northern bank of the Danube, close to the Iron Gates. "Drobeta" is the name of the ancient Dacian and Roman towns at the site, and the modern ...