Nicky Barr on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Andrew William "Nicky" Barr, (10 December 1915 – 12 June 2006) was a member of the

Barr was posted to

Barr was posted to  On 25 May 1942, Barr had to land in the desert when his engine overheated. Having just taken off the engine

On 25 May 1942, Barr had to land in the desert when his engine overheated. Having just taken off the engine  Barr tried to escape from his confinement four times. By November 1942 he had recovered sufficiently from the injuries he received in June to break out of the hospital where he was being held in

Barr tried to escape from his confinement four times. By November 1942 he had recovered sufficiently from the injuries he received in June to break out of the hospital where he was being held in

Australian national rugby union team

The Australia national rugby union team, nicknamed the Wallabies, is the representative national team in the sport of rugby union for the nation of Australia. The team first played at Sydney in 1899, winning their first test match against the ...

, who became a fighter ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ace is varied, but is usually co ...

in the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

(RAAF) during World War II. He was credited with 12 aerial victories, all scored flying the Curtiss P-40

The Curtiss P-40 Warhawk is an American single-engined, single-seat, all-metal fighter and ground-attack aircraft that first flew in 1938. The P-40 design was a modification of the previous Curtiss P-36 Hawk which reduced development time and ...

fighter. Born in New Zealand, Barr was raised in Victoria and first represented the state in rugby in 1936. Selected to play for Australia in the United Kingdom in 1939, he had just arrived in England when the tour was cancelled following the outbreak of war. He joined the RAAF in 1940 and was posted to North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

with No. 3 Squadron in September 1941. The squadron's highest-scoring ace, he attained his first three victories in the P-40 Tomahawk and the remainder in the P-40 Kittyhawk.

Barr's achievements as a combat pilot earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

. Shortly after taking command of No. 3 Squadron in May 1942, he was shot down and captured by Axis forces, and incarcerated in Italy. He escaped and assisted other Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

fugitives to safety, receiving for his efforts the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

, a rare honour for an RAAF pilot. Repatriated to England, he saw action during the invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

in June 1944 before returning to Australia as chief instructor with No. 2 Operational Training Unit. After the war he became a company director, and rejoined the RAAF as an active reserve officer from 1951 to 1953. From the early 1960s he was heavily involved in the oilseed industry, for which he was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

in 1983. He died in 2006, aged 90.

Early career

Andrew Barr was born inWellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

, New Zealand, on 10 December 1915; he had a twin brother, Jack. The family moved to Australia when the boys were six. Growing up in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, Andrew attended Kew Public School and played Australian rules football

Australian football, also called Australian rules football or Aussie rules, or more simply football or footy, is a contact sport played between two teams of 18 players on an oval field, often a modified cricket ground. Points are scored by k ...

. He was also the Victorian Schoolboys' 100 yards athletics champion three years in succession, from 1926 to 1928. In 1931, aged fifteen, he began his association with the Lord Somers Camp

Lord Somers Camp, or "Big Camp", is an annual week-long camp for boys and girls held in Somers, Victoria, Australia.

Founded in Anglesea, Victoria, in 1929 by The 6th Baron Somers, the then Governor of Victoria, the camp has been running co ...

and Power House social and sporting organisations located at Western Port. After leaving school, Barr studied construction at Swinburne Technical College

Swinburne University of Technology (often simply called Swinburne) is a public research university based in Melbourne, Australia. It was founded in 1908 as the Eastern Suburbs Technical College by George Swinburne to serve those without access ...

, but later took a diploma course in accountancy and made it his profession. He started playing rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In its m ...

in 1935 through a friend in the Power House club. Weighing and just under tall, Barr gained selection for Victoria as a hooker

Hooker may refer to:

People

* Hooker (surname)

Places Antarctica

* Mount Hooker (Antarctica)

* Cape Hooker (Antarctica)

* Cape Hooker (South Shetland Islands)

New Zealand

* Hooker River

* Mount Hooker (New Zealand) in the Southern Alps

* Hoo ...

the following year. In 1939, he was chosen to play in the United Kingdom with the Australian national team, the Wallabies

A wallaby () is a small or middle-sized macropod native to Australia and New Guinea, with introduced populations in New Zealand, Hawaii, the United Kingdom and other countries. They belong to the same taxonomic family as kangaroos and so ...

. The tour was cancelled less than a day after the team arrived in the UK on 2 September, due to the outbreak of World War II. Keen to serve as a fighter pilot

A fighter pilot is a military aviator trained to engage in air-to-air combat, air-to-ground combat and sometimes electronic warfare while in the cockpit of a fighter aircraft. Fighter pilots undergo specialized training in aerial warfare and ...

, Barr initially tried to enlist in the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

, but withdrew his application when told that it was unlikely he would fly anytime in the near future, and that he could expect only administrative duties in the interim.

Returning to Australia on the RMS ''Strathaird'', Barr joined the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

as an air cadet on 4 March 1940.Barr; Stokes 1990 After undergoing instruction on Tiger Moth

The de Havilland DH.82 Tiger Moth is a 1930s British biplane designed by Geoffrey de Havilland and built by the de Havilland Aircraft Company. It was operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and other operators as a primary trainer aircraft. ...

s at No. 3 Elementary Flying Training School, Essendon Essendon may refer to:

Australia

*Electoral district of Essendon

*Electoral district of Essendon and Flemington

*Essendon, Victoria

**Essendon railway station

**Essendon Airport

*Essendon Football Club in the Australian Football League

United King ...

, and on Hawker Demon

The Hawker Hart is a British two-seater biplane light bomber aircraft that saw service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was designed during the 1920s by Sydney Camm and manufactured by Hawker Aircraft. The Hart was a prominent British aircra ...

s and Avro Anson

The Avro Anson is a British twin-engined, multi-role aircraft built by the aircraft manufacturer Avro. Large numbers of the type served in a variety of roles for the Royal Air Force (RAF), Fleet Air Arm (FAA), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) a ...

s at No. 1 Service Flying Training School, Point Cook

Point Cook is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, south-west of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Wyndham local government area. Point Cook recorded a population of 66,781 at the 2021 census.

Point Cook ...

, he was commissioned as a pilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off officially in the RAF; in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly P/O in all services, and still often used in the RAF) is the lowest commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many other Commonwealth countri ...

on 24 September.Dornan 2005, pp. 10–12 He gained a reputation as something of a rebel during training, and became forever known as "Nicky", for " Old Nick", or the Devil. In his quest to gain assignment as a fighter pilot, he had deliberately aimed poorly during bombing practice, a stratagem also adopted by at least two of his fellow students. By November 1940, he had been posted to No. 23 (City of Brisbane) Squadron, flying CAC Wirraways on patrol off the Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

coast. The aircraft was, according to Barr, "our front line fighter in those days, but it didn't take too long to realise that the capacity of the Wirraway, compared with the types of planes that we were going to encounter, left much to be desired". Though his duties frustrated him somewhat, Barr was grateful to have this extensive flight experience under his belt when he eventually saw combat. While based in Queensland, he served as honorary aide-de-camp to the Governor, Sir Leslie Wilson, and also captained the RAAF rugby union team. He was promoted to flying officer on 24 March 1941.

Combat service

Barr was posted to

Barr was posted to North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

on 28 September 1941, to fly with No. 3 Squadron under the command of Squadron Leader Peter Jeffrey

Peter Jeffrey (18 April 1929 – 25 December 1999) was an English character actor. Starting his performing career on stage, he would later have many roles in television and film.

Early life

Jeffrey was born in Bristol, the son of Florence ...

.Garrisson 1999, pp. 113–115 He converted to P-40 Tomahawk fighters at an RAF operational training unit in Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

. There he also received his " goolie chit", a piece of paper to be shown to local tribesmen in the event he was shot down, reading in Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

: "don't kill the bearer, feed him and protect him, take him to the English and you will be rewarded. Peace be upon you." Returning to North Africa, Barr achieved his first aerial victory, over a Messerschmitt Bf 110

The Messerschmitt Bf 110, often known unofficially as the Me 110,Because it was built before ''Bayerische Flugzeugwerke'' became Messerschmitt AG in July 1938, the Bf 110 was never officially given the designation Me 110. is a twin-engined (de ...

, on 12 December. He followed this up with a Junkers Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a Nazi Germany, German World War II ''Luftwaffe'' twin-engined multirole combat aircraft. Junkers, Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works (JFM) designed the plane in the mid-1930s as a so-called ''Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") th ...

and a Messerschmitt Bf 109 the next day. The squadron then re-equipped with P-40 Kittyhawks; Barr was flying the new model when he became an ace

An ace is a playing card, Dice, die or domino with a single Pip (counting), pip. In the standard French deck, an ace has a single suit (cards), suit symbol (a heart, diamond, spade, or club) located in the middle of the card, sometimes large a ...

on New Year's Day 1942, shooting down two Junkers Ju 87 ''Stukas''.Thomas 2005, pp. 22–23 On 8 March, he led a flight of six Kittyhawks to intercept a raid on Tobruk

Tobruk or Tobruck (; grc, Ἀντίπυργος, ''Antipyrgos''; la, Antipyrgus; it, Tobruch; ar, طبرق, Tubruq ''Ṭubruq''; also transliterated as ''Tobruch'' and ''Tubruk'') is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near th ...

by twelve Ju 87s escorted by ten Macchi C. 202s and two Bf 109s. The Australians destroyed six Macchis and three Ju 87s without loss, Barr personally accounting for one of the Macchis.

Eventually credited with victories over twelve enemy aircraft, plus two probables and eight damaged, Barr became No. 3 Squadron's highest-scoring member.Newton 1996, pp. 65–66 He flew a total of eighty-four combat sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warfare. ...

s, twenty of them in one fortnight, and six on 16 June 1942 alone. His philosophy was that the P-40 was not a top-class fighter, but that its shortcomings "could be offset by unbridled aggression", so he resolved to treat aerial combat as he would a boxing match and "overcome much better opponents by simply going for them". Bobby Gibbes

Robert Henry Maxwell Gibbes, (6 May 1916 – 11 April 2007) was an Australian fighter ace of World War II, and the longest-serving wartime commanding officer of No. 3 Squadron RAAF. He was officially credited with 10¼ ae ...

became No. 3 Squadron's commanding officer in February 1942, and made Barr his senior flight commander. Promoted to flight lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth countries. It has a NATO rank code of OF-2. Flight lieutenant is abbreviated as Flt Lt in the India ...

on 1 April, Barr was raised to acting squadron leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr in the RAF ; SQNLDR in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly sometimes S/L in all services) is a commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence. It is also ...

and appointed to command the unit in May, barely six months after he commenced operations, following Gibbes's hospitalisation with a broken ankle. Barr had never sought leadership of the squadron, and felt that others were just as well qualified for the role. As a commander he delegated most administrative tasks to his adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of human resources in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed forces as a non-commission ...

but, contrary to normal practice, wrote letters to the next-of-kin of casualties himself.

Barr was shot down three times while serving with No. 3 Squadron. The first occasion was on 11 January 1942 when, having destroyed a Bf 109 and a Fiat G.50

The Fiat G.50 ''Freccia'' ("Arrow") was a World War II Italian fighter aircraft developed and manufactured by aviation company Fiat. Upon entering service, the type became Italy’s first single-seat, all-metal monoplane that had an enclosed co ...

, he was preparing to touch down in the desert to pick up a fellow pilot who had crash landed. Barr was halfway through lowering his undercarriage when he was "jumped" by two other Bf 109s. He immediately engaged both and shot one down before more German fighters arrived and he was hit and forced to land behind enemy lines.Wilson 2005, pp. 86–87 As one of the German pilots came in low to strafe the downed Kittyhawk, Barr ran straight at it in an attempt to throw the pilot off his aim, and was injured by fragments of rock sent airborne by the impact of cannon shells. A tribe of friendly Senussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

Arabs found him, dressed his wounds, and helped him return to Allied lines. For his exploit, and his earlier successes, Barr was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), the complete citation being published in the ''London Gazette

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

'' on 20 February 1942:

On 25 May 1942, Barr had to land in the desert when his engine overheated. Having just taken off the engine

On 25 May 1942, Barr had to land in the desert when his engine overheated. Having just taken off the engine cowling

A cowling is the removable covering of a vehicle's engine, most often found on automobiles, motorcycles, airplanes, and on outboard boat motors. On airplanes, cowlings are used to reduce drag and to cool the engine. On boats, cowlings are a cove ...

, he spotted enemy tanks approaching and immediately took off with the engine exposed to the elements, safely landing back at base. He was shot down for the second time on 30 May, when he engaged eight Bf 109s and destroyed one before being hit and forced to crash land at high speed in no-man's land. He came down in a minefield during a fierce tank battle, and was forced to remain where he was as troops of both sides slowly converged on him; British forces managed to reach him first and, after treatment for wounds, he again returned to his squadron. On 26 June, after being attacked by two Bf 109s and bailing out of his burning Kittyhawk, he was captured by Italian soldiers and taken as a prisoner-of-war, first to Tobruk

Tobruk or Tobruck (; grc, Ἀντίπυργος, ''Antipyrgos''; la, Antipyrgus; it, Tobruch; ar, طبرق, Tubruq ''Ṭubruq''; also transliterated as ''Tobruch'' and ''Tubruk'') is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near th ...

, and then to Italy, where he received hospital treatment for serious wounds. He later learned that the pilot who shot him down was Oberleutnant Werner Schroer, a Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

ace credited with sixty-one victories in North Africa. Bobby Gibbes, having recovered from his own injuries, again took command of No. 3 Squadron. During his incarceration, on 5 February 1943, Barr was awarded a Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

to his DFC for "destroying further enemy aircraft".

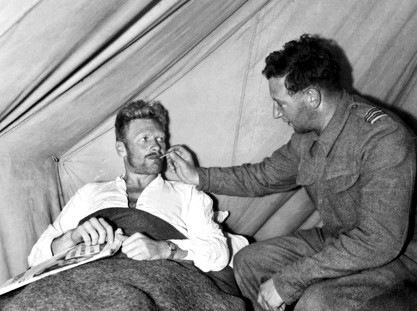

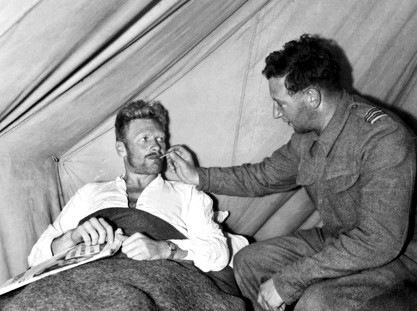

Barr tried to escape from his confinement four times. By November 1942 he had recovered sufficiently from the injuries he received in June to break out of the hospital where he was being held in

Barr tried to escape from his confinement four times. By November 1942 he had recovered sufficiently from the injuries he received in June to break out of the hospital where he was being held in Bergamo

Bergamo (; lmo, Bèrghem ; from the proto- Germanic elements *''berg +*heim'', the "mountain home") is a city in the alpine Lombardy region of northern Italy, approximately northeast of Milan, and about from Switzerland, the alpine lakes Como ...

, northern Italy. He made his way to the Swiss border, but was challenged by an Italian customs official, whom he struck with a rock before being recaptured. Court-martialled on a charge of murder, he only avoided a death sentence when the Swiss Red Cross

The Swiss Red Cross (German: ', French: ', Italian: ', Romansh: '), or SRC, is the national Red Cross society for Switzerland.

The SRC was founded in 1866 in Bern, Switzerland. In accordance with the Geneva Red Cross Agreement and its r ...

colonel representing him located the official and proved that he had not died. Barr was instead sentenced to ninety days solitary confinement in Gavi Prison Camp, Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

. In August 1943, with Italy on the verge of surrender, prisoners of war were rounded up for transport to Germany. Barr jumped from a moving train bound for the Brenner Pass

The Brenner Pass (german: link=no, Brennerpass , shortly ; it, Passo del Brennero ) is a mountain pass through the Alps which forms the border between Italy and Austria. It is one of the principal passes of the Eastern Alpine range and has ...

and joined a group of Italian partisans in Pontremoli, remaining at large for two months before again being captured. Taken to a transit camp just over the Austrian border, Barr and fourteen other prisoners escaped by tunnelling under the barbed wire. Eventually he managed to link up with an Allied special operations unit, which was gathering intelligence behind enemy lines, sabotaging Axis infrastructure, and helping Allied prisoners and Italian refugees escape over the Apennine Mountains

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains (; grc-gre, links=no, Ἀπέννινα ὄρη or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; la, Appenninus or – a singular with plural meaning;''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which wou ...

along the so-called "Alpine Route". He was recaptured and escaped once more before finally making it through the Alpine crossing himself, leading a group of more than twenty. After reaching friendly lines in March 1944, he was sent to a military hospital in Vasto, weighing only and in poor health, suffering malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, malnutrition, and blood poisoning. The assistance he rendered to fellow Allied fugitives earned him the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

(MC) for "Exceptional courage in organising escapes"; the award was gazetted on 1 December 1944. He is thought to be one of only five or six RAAF pilots to receive the MC during World War II.

Posted to Britain in April 1944, Barr went ashore at Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach was one of five beach landing sectors designated for the amphibious assault component of operation Overlord during the Second World War. On June 6, 1944, the Allies invaded German-occupied France with the Normandy landings. "Omaha" r ...

two days after D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as D ...

as part of an air support control unit. During the campaign in Normandy, he flew rocket-armed Hawker Typhoons on operations against V-1 flying bomb

The V-1 flying bomb (german: Vergeltungswaffe 1 "Vengeance Weapon 1") was an early cruise missile. Its official Ministry of Aviation (Nazi Germany), Reich Aviation Ministry () designation was Fi 103. It was also known to the Allies as the buz ...

launch sites. After his return to Australia on 11 September, Barr was promoted to acting wing commander and appointed chief instructor at No. 2 Operational Training Unit in Mildura, Victoria, taking over from Bobby Gibbes. He also went to New Guinea and flew some ground-attack missions in the Kittyhawk to gain experience in the South West Pacific theatre. Following the end of hostilities in August 1945, Barr was treated for recurring fever and underwent two operations on his limbs in No. 6 RAAF Hospital, Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

. He was discharged from the Air Force on 8 October.

Later career

After leaving the Air Force, Barr remained in Mildura with his wife, Dorothy (Dot). They had met on a blind date in 1938 and been married only a few weeks when Nicky joined the RAAF. During the war she was told on three occasions that her husband was dead. The couple had two sons, born in 1945 and 1947.Dornan 2005, pp. 273–274 Barr's injuries prevented him from returning to a rugby career, and he took up yachting as a sport. He also briefly assisted fellow No. 3 Squadron veteran Bobby Gibbes in an airline venture in New Guinea, before going into business as a company manager and director with civil engineering and pharmaceutical firms. Barr rejoined the RAAF on 20 March 1951 as a pilot in the activeCitizen Air Force

The Air Force Reserve or RAAF Reserve is the common, collective name given to the reserve units of the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, mar ...

(CAF), with the acting rank of wing commander. On 15 April 1953, he transferred to the CAF reserve. A member of the Royal Air Forces Escaping Society

The Royal Air Forces Escaping Society, was a UK-based charitable organization formed in 1946 to provide help to those in the former occupied countries in World War II who put their lives at risk to assist and save members of the ''"Royal Air For ...

, Barr began travelling to Italy with his wife on a regular basis in the late 1950s to seek out and offer assistance to those who had helped him during his wartime escape attempts.

In 1961, Barr became General Manager of Meggitt Ltd, an oilseed-crushing firm; he eventually rose to become Executive Chairman. The firm's board was joined in 1971 by the recently retired Chief of the Air Staff, Air Marshal Sir Alister Murdoch. Barr's work in the industry led to his appointment in the 1983 New Year Honours as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(OBE). The same year, he became Australian representative and Chairman of the International Oil Seed Group. In June 1987, Barr accepted an invitation to join John Glenn

John Herschel Glenn Jr. (July 18, 1921 – December 8, 2016) was an American Marine Corps aviator, engineer, astronaut, businessman, and politician. He was the third American in space, and the first American to orbit the Earth, circling ...

, Chuck Yeager, and fifteen other famed flyers in a so-called "Gathering of Eagles

The Gathering of Eagles Program is an annual aviation event that traces its origin back to 1980, when retired Brig. Gen. Paul Tibbets was invited to visit the Air Command and Staff College at Maxwell Air Force Base to share some of his experiences ...

" for a seminar at the USAF Air Command and Staff College

The Air Command and Staff College (ACSC) is located at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama and is the United States Air Force's intermediate-level Professional Military Education (PME) school. It is a subordinate command of the Air Uni ...

in Montgomery, Alabama. Generally reluctant to talk publicly about the war, he agreed to discuss his experiences during an episode of the television series '' Australian Story'' in 2002, appearing with his biographer Peter Dornan, and Bobby Gibbes. By this time Barr was said to be receiving daily treatment for the injuries he had suffered in combat. He died at the age of ninety on 12 June 2006, a few months after his wife. Four F/A-18 Hornet

The McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet is an all-weather, twinjet, twin-engine, supersonic aircraft, supersonic, carrier-based aircraft, carrier-capable, Multirole combat aircraft, multirole combat aircraft, designed as both a Fighter aircraft, ...

jet fighters from No. 3 Squadron overflew his funeral service on the Gold Coast

Gold Coast may refer to:

Places Africa

* Gold Coast (region), in West Africa, which was made up of the following colonies, before being established as the independent nation of Ghana:

** Portuguese Gold Coast (Portuguese, 1482–1642)

** Dutch G ...

, Queensland. He was further honoured at a rugby test match between Australia and England at Telstra Dome in Melbourne on 17 June, the day after his funeral. On 14 September 2006, No. 3 Squadron dedicated a stone memorial in Barr's honour; the unveiling was attended by his sons Bob and Brian.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Barr, Nicky 1915 births 2006 deaths Australian escapees Australian prisoners of war Australian rugby union players Australian World War II flying aces Officers of the Order of the British Empire Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) Recipients of the Military Cross Royal Australian Air Force officers Royal Australian Air Force personnel of World War II Rugby union hookers Shot-down aviators World War II prisoners of war held by Italy New Zealand emigrants to Australia