Nicholas Biddle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nicholas Biddle (January 8, 1786February 27, 1844) was an American

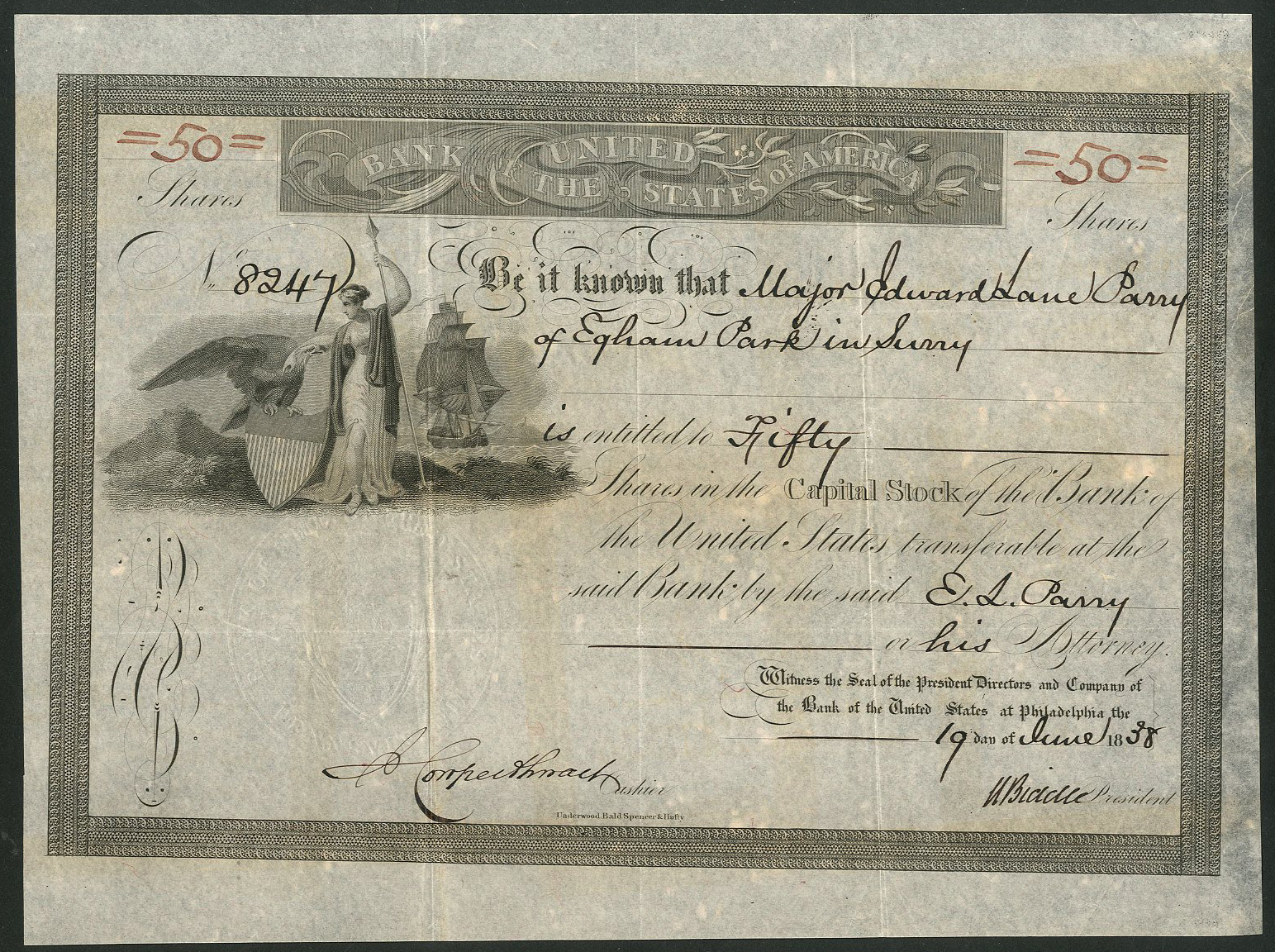

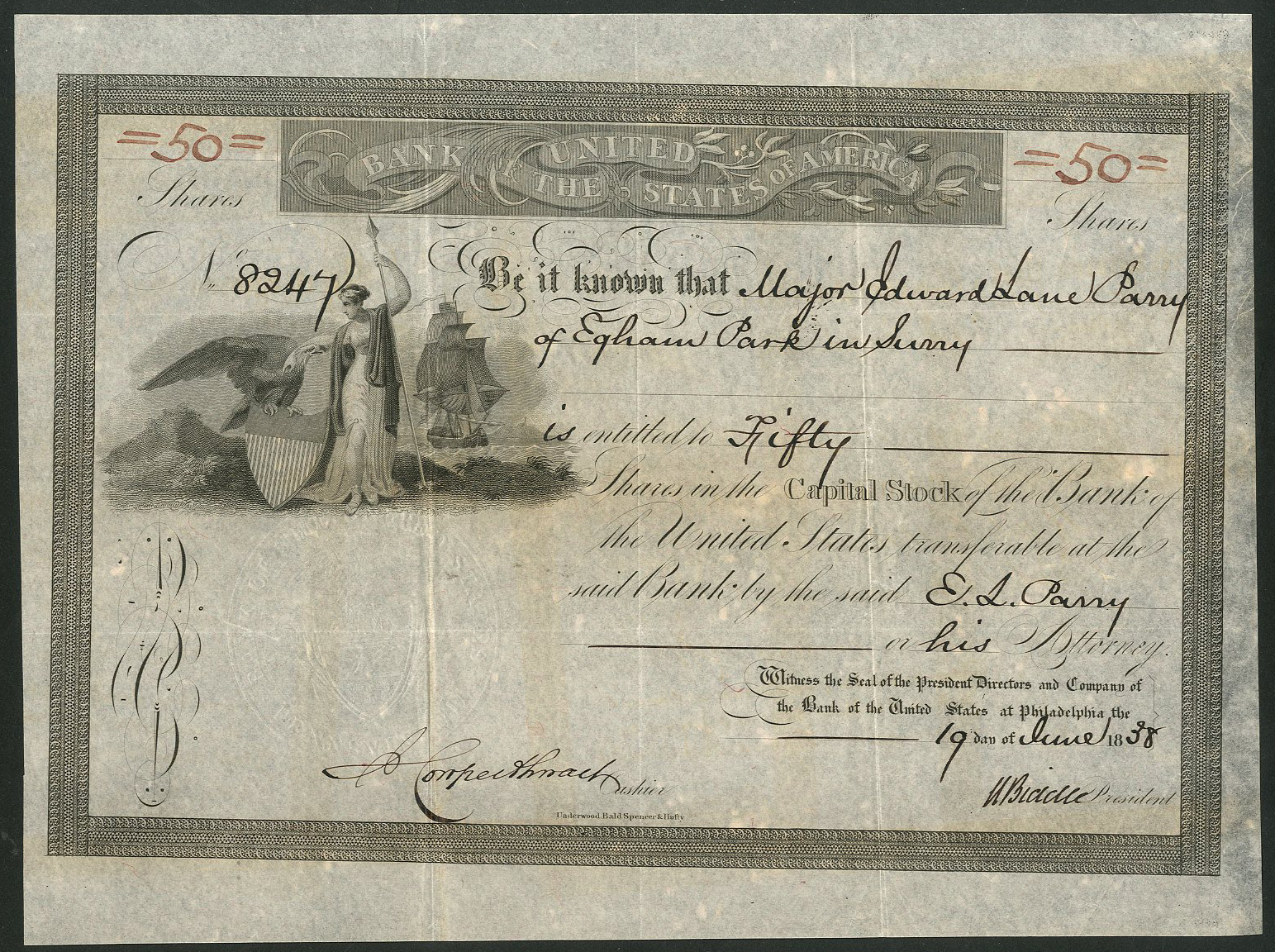

The Second Bank's twenty-year charter expired in April 1836, but Biddle worked with the Pennsylvania state legislature to prolong the institution as a state-chartered bank, the United States Bank of Pennsylvania (BUSP). The BUSP remained open for several more years. It was in the later years of his career that Biddle began to invest significant financial resources not only in internal improvement projects, but also in the booming expansion of land, cotton, and slavery in the Old Southwest.

In 1837 and 1838, Biddle secretively dispatched agents into the South to buy up several million dollars worth of cotton with the notes of state-chartered banks, all in an effort to restore the nation's credit and pay off foreign debts owed to British merchant bankers. Critics called this an example of illegal cotton speculation and noted that the Bank's charter forbid the institution from purchasing commodities. Biddle also invested in and bailed out several state-chartered banks in the South whose capital was derived partially from slave mortgages. Some of these banks, including the Union Bank of Mississippi, financed the dispossession of Native Americans. Indeed, post-notes issued by the BUSP helped conclude one of the treaties that removed the

The Second Bank's twenty-year charter expired in April 1836, but Biddle worked with the Pennsylvania state legislature to prolong the institution as a state-chartered bank, the United States Bank of Pennsylvania (BUSP). The BUSP remained open for several more years. It was in the later years of his career that Biddle began to invest significant financial resources not only in internal improvement projects, but also in the booming expansion of land, cotton, and slavery in the Old Southwest.

In 1837 and 1838, Biddle secretively dispatched agents into the South to buy up several million dollars worth of cotton with the notes of state-chartered banks, all in an effort to restore the nation's credit and pay off foreign debts owed to British merchant bankers. Critics called this an example of illegal cotton speculation and noted that the Bank's charter forbid the institution from purchasing commodities. Biddle also invested in and bailed out several state-chartered banks in the South whose capital was derived partially from slave mortgages. Some of these banks, including the Union Bank of Mississippi, financed the dispossession of Native Americans. Indeed, post-notes issued by the BUSP helped conclude one of the treaties that removed the

In 1811, Biddle married Jane Margaret Craig (1793–1856). The couple had six children, including

In 1811, Biddle married Jane Margaret Craig (1793–1856). The couple had six children, including

Article and portrait at "Discovering Lewis & Clark"

The Economic Historian: Encyclopedia of Economic History ''Nicholas Biddle''

*

Genealogy of Nicholas Biddle (1786–1844)

* James Kendall Hosmer — American history professor and librarian who edited reprinted and published Nicholas Biddle's account of Lewis and Clark's journal * Th

Biddle and Craig family Papers

including business and personal correspondence, are available for research use at the

financier

An investor is a person who allocates financial capital with the expectation of a future return (profit) or to gain an advantage (interest). Through this allocated capital most of the time the investor purchases some species of property. Type ...

who served as the third and last president of the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

(chartered 1816–1836). Throughout his life Biddle worked as an editor, diplomat, author, and politician who served in both houses of the Pennsylvania state legislature. He is best known as the chief opponent of Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

in the Bank War

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its re ...

.

Born into the illustrious Biddle family

The Biddle family of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania is an Old Philadelphian family descended from English immigrants William Biddle (1630–1712) and Sarah Kempe (1634–1709), who arrived in the Province of New Jersey in 1681. Quakers, they had emi ...

of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, young Nicholas worked for a number of prominent officials, including John Armstrong Jr. and James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

. In the Pennsylvania state legislature, he defended the utility of a national bank in the face of Jeffersonian criticisms. From 1823 to 1836, Biddle served as president of the Second Bank, during which time he exercised power over the nation's money supply and interest rates, seeking to prevent economic crises.

With prodding from Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

and the Bank's major stockholders, Biddle engineered a bill in Congress to renew the Bank's federal charter in 1832. The bill passed Congress and headed to President Andrew Jackson's desk. Jackson, who expressed deep hostility to most banks, vetoed the measure, ratcheting up tensions in a major political controversy known as the Bank War. When Jackson transferred the federal government's deposits from the Second Bank to several state banks, Biddle raised interest rates, causing a mild economic recession. The federal charter expired in 1836, but the bank continued to operate with a Pennsylvania state charter until its ultimate collapse in 1841.

Ancestry and early life

Nicholas Biddle was born into a prominent family inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Ma ...

, on January 8, 1786. Ancestors of the Biddle family

The Biddle family of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania is an Old Philadelphian family descended from English immigrants William Biddle (1630–1712) and Sarah Kempe (1634–1709), who arrived in the Province of New Jersey in 1681. Quakers, they had emi ...

had immigrated to the Pennsylvania colony along with the famous Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

proprietor, William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

, and subsequently fought in the pre- Revolutionary colonial struggles. Young Nicholas's preparatory education was received at an academy in Philadelphia, where his progress was so rapid that he entered the class of 1799 at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

. At thirteen years old, Biddle had completed his coursework, but was not allowed to graduate due to his age. His parents accordingly sent him to Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

(then the “College of New Jersey”) where he entered the sophomore class, and graduated in 1801 as valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA ...

, dividing the first honor of the class with his only rival.

Biddle was offered an official position before he had even finished his law studies. As secretary to former Revolutionary War officer and delegate to the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

, John Armstrong Jr., he went abroad in 1804 and was in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

when Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

was crowned as emperor of the new French Empire. Afterwards he participated in an audit

An audit is an "independent examination of financial information of any entity, whether profit oriented or not, irrespective of its size or legal form when such an examination is conducted with a view to express an opinion thereon.” Auditing ...

related to the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

, acquiring his first experience in financial affairs. Biddle traveled extensively through Europe as secretary for James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

, who was then serving as the United States minister to the Court of St. James

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordanc ...

. In Great Britain, Biddle took part in a conversation with Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

professors involving comparisons between the modern Greek dialect and that of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

; a conversation that captured Monroe's attention.

In 1807, Biddle returned home to Philadelphia. He practiced law and wrote, contributing papers to different publications on various subjects, but chiefly in the fine arts. He became associate editor of a literary magazine called '' Port-Folio'', which was published from 1806 to 1823. When editor Joseph Dennie

Joseph Dennie (August 30, 1768January 7, 1812) was an American author and journalist who was one of the foremost men of letters of the Federalist Era. A Federalist, Dennie is best remembered for his series of essays entitled ''The Lay Preacher' ...

died in 1812, Biddle took over the magazine and lived on 7th Street, near Spruce Street. That same year, Biddle was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

Lewis and Clark

Biddle also edited the journals of theLewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

. He encouraged President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

to write an introductory memoir of his former aide and private secretary, Captain Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 – October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with ...

(1774–1809). Biddle's work would be published as a book in 1814 and would become the standard account of the expedition for more than a century. But because he had been elected to the Pennsylvania state legislature, Biddle was compelled to hand over editorial responsibilities to Paul Allen

Paul Gardner Allen (January 21, 1953 – October 15, 2018) was an American business magnate, computer programmer, researcher, investor, and philanthropist. He co-founded Microsoft Corporation with childhood friend Bill Gates in 1975, which ...

(1775–1826), who supervised the project until its completion and appeared in print as the book's official editor.

Pennsylvania General Assembly

Biddle was elected as a Republican member of thePennsylvania House of Representatives

The Pennsylvania House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Pennsylvania General Assembly, the legislature of the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. There are 203 members, elected for two-year terms from single member districts.

It ...

in 1810, and then in the Pennsylvania State Senate

The Pennsylvania State Senate is the upper house of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, the Pennsylvania state legislature. The State Senate meets in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. Senators are elected for four year terms, staggered ev ...

for the 1st district from 1813 to 1815. He originated a bill favoring a free system of public schools—available to all Pennsylvanians regardless of their economic class—almost a quarter of a century in advance of the times. Though the bill was initially defeated, it resurfaced repeatedly in different forms until, in 1836, the Pennsylvania "common-school" system was inaugurated as an indirect result of his efforts.

The Bank of the United States

Early years

After Biddle moved to thePennsylvania State Senate

The Pennsylvania State Senate is the upper house of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, the Pennsylvania state legislature. The State Senate meets in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. Senators are elected for four year terms, staggered ev ...

, he lobbied for the rechartering of the First Bank of the United States. It was on this subject that he made his first major speech, which attracted general attention at the time, and was warmly commended by Chief Justice John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

and other leaders of public opinion.

The First Bank had been established in 1791 under the administration of President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

. Congress opted not to renew its twenty-year charter in 1811, and as a result, the First Bank closed its doors. After economic hardships, monetary pressures, and problems financing the federal government during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, Congress and the president granted a new twenty-year charter to the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

in 1816. The Second Bank was in many ways a revived and reorganized version of the First Bank. President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

subsequently appointed Biddle as a government director. When Bank President Langdon Cheves

Langdon Cheves ( September 17, 1776 – June 26, 1857) was an American politician, lawyer and businessman from South Carolina. He represented the city of Charleston in the United States House of Representatives from 1810 to 1815, where he played ...

resigned in 1822, Biddle became the institution's new president. During his association with the Bank, President Monroe, under authority from Congress, directed him to prepare a "Commercial Digest" of the laws and trade regulations of the world and the various nations. For many years after, this Digest was regarded as an authority on the subject.

In late 1818, $4 million of interest payments on the bonds previously sold in 1803 to pay for the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

were due, in either gold or silver, to European investors. The Treasury Department, therefore, had to acquire additional amounts of specie

Specie may refer to:

* Coins or other metal money in mass circulation

* Bullion coins

* Hard money (policy)

* Commodity money

Commodity money is money whose value comes from a commodity of which it is made. Commodity money consists of objects ...

. As the federal government's chief fiscal agent, the Bank was obligated to make these payments on behalf of the Treasury. The Bank demanded that private and state-chartered commercial banks, many of which had loaned excessively and previously served as fiscal agents during the War of 1812, now pay the Second Bank in specie, which was then sent to Europe to pay the federal government's creditors. This rather sudden contraction of the country's monetary base after three years of speculation helped contribute to the financial Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

.

Meanwhile, in Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, military hero and future presidential candidate Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

was hard-pressed to pay his debts during this period. He developed a lifelong hostility to all banks that were not completely backed by gold or silver deposits. This meant, above all, hostility to the new Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

.

As a banker, Biddle promulgated a nationalistic vision with an emphasis on regulation and flexibility. He was also innovative. Biddle occasionally engaged in the relatively new techniques of central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central ba ...

ing–-controlling the nation's money supply, regulating interest rates, lending to state banks, and acting as the Treasury Department's chief fiscal agent. When state banks became excessive in their lending practices, Biddle's Bank acted as a restraint. In a few instances, he even rescued state banks to prevent the risk of "contagion" spreading.

In 1823, Biddle started concentrating the Bank's facilities in the West, Southwest, and South to meet the demands for credit generated by the expansion of land, cotton, and slavery. He did this by directing his branch officers to circulate large quantities of branch drafts and by buying and selling millions of dollars of bills of exchange. As cotton moved downriver in the winter and spring months, merchants drew up bills of exchange representing the value of cotton exports, presenting them to the Bank's southern branches. Using its interregional network of branch offices and the transportation improvements then under way, the Bank would ship these bills to the Northeast where merchants could use them to pay for imported manufactured goods arriving from Great Britain in the summer and fall. The result was that Biddle helped provide an economic infrastructure that facilitated long-distance trade, propagated a relatively stable and uniform currency, and played a major role in integrating and consolidating fiscal operations at the federal level. Indeed, Biddle won praise for the Bank by making steady payments to reduce the country's public debt, by preventing a potentially harmful recession in the winter of 1825–1826, and more generally, by smoothing out variations in prices and trade.

He was also important in the 1833 establishment of Girard College

Girard College is an independent college preparatory five-day boarding school located on a 43-acre campus in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The school was founded and permanently endowed from the shipping and banking fortune of Stephen Girard upon ...

, an early free private school for poor orphaned boys in Philadelphia, under the provisions of the will of his friend and former legal client, Stephen Girard (1750–1831), one of the wealthiest men in America. Girard had been the original promoter of the revival and reorganization of the Second Bank and its largest investor.

Bank War

TheBank War

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its re ...

began when President Jackson started criticizing the Bank early in his first term. Beyond the long list of personal and ideological objections that Jackson maintained toward the Bank, there were rumors that Bank officers at some of the branch offices had interfered in the presidential contest of 1828 by providing financial assistance to the National Republican candidate, John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

. Although Biddle traveled to the branch offices to examine the veracity of these claims in person, and denied them unequivocally, Jackson continued to believe that they were true. In January 1832, Biddle submitted an application to Congress for a renewal of the Bank's twenty-year charter, four years before the current charter was due to expire. Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

and other Bank supporters hoped to force Jackson into making an unpopular decision that might cost him during an election year, but there were also pressures for an early application emanating from the Bank's stockholders and board of directors. President Jackson vetoed the bill in a stunning move that carried significant consequences for the relationship between Congress and the executive branch. The reasons for Jackson's veto were legion and included concerns over the Bank's monopoly power and concentrated wealth, constitutional scruples, states' rights, the Bank's foreign stockholders and ability to foreclose on large parcels of land, sectional animosity toward eastern financiers, and political patronage. An additional factor was Jackson's personality. The president was well known for his stubbornness and continued to harbor resentment toward Clay from the earlier " Corrupt Bargain" accusation following the presidential election of 1824.

At Biddle's direction, the Bank poured tens of thousands of dollars into a campaign to defeat Jackson in the presidential election of 1832. This was a continuation of a strategy that one historian has referred to as one of the earliest examples in the country's history of an interregional corporate lobby and public relations campaign. Articles, stockholders' reports, editorials, essays, philosophical treatises, petitions, pamphlets, and copies of congressional speeches were among the diverse forms of media that Biddle transmitted to various sections of the country through loans and Bank expenditures. Reports of unusually generous loans to pro-BUS politicians and even small bribes to sympathetic newspaper editors, the details of which came to light in a congressional report published in April 1832, helped convince hard-line Jacksonians that the corrupt "Monster Bank" must be destroyed. Biddle was told that such vigorous campaign spending would only give credence to Jackson's theory that the Bank interfered in the American political process, but chose to dismiss the warning. Ultimately, Clay's strategy failed, and in November he lost handily to Jackson, who was reelected to a second term.

In early 1833, Jackson, despite opposition from some members of his cabinet, decided to withdraw the Treasury Department's public (or federal) deposits from the Bank. The incumbent secretary of the treasury, Louis McLane

Louis McLane (May 28, 1786 – October 7, 1857) was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, in New Castle County, Delaware, and Baltimore, Maryland. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, a member of the Federalist Party and later th ...

, a member of Jackson's Cabinet, professed moderate support for the Bank. He therefore refused to withdraw the federal deposits directed by the president and would not resign, so Jackson then transferred him to the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

. McLane's successor, William J. Duane

William John Duane (May 9, 1780 – September 27, 1865) was an American politician and lawyer from Pennsylvania.

Duane served a brief term as United States Secretary of the Treasury in 1833. His refusal to withdraw Federal deposits from the Seco ...

, was also opposed to the Bank, but would not carry out Jackson's orders either. After waiting four months, President Jackson summarily dismissed Duane, replacing him with Attorney General Roger B. Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

as a recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the advi ...

when Congress was out of session. In September 1833, Taney helped transfer the public deposits from the Bank to seven state-chartered banks. Faced with the loss of the federal deposits, Biddle decided to raise interest rates. A mild financial panic

A financial crisis is any of a broad variety of situations in which some financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with banking panics, and man ...

ensued from late 1833 to mid-1834. Intended to force Jackson into a compromise and demonstrate the utility of a national bank for the nation's economy, the move had the opposite effect of increasing anti-Bank sentiment. Meanwhile, Biddle and other Bank supporters attempted to renew the Bank's charter on numerous occasions. All their attempts failed because they did not have the two-thirds majorities in Congress to overcome a presidential veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto pow ...

.

Demise of the bank

The Second Bank's twenty-year charter expired in April 1836, but Biddle worked with the Pennsylvania state legislature to prolong the institution as a state-chartered bank, the United States Bank of Pennsylvania (BUSP). The BUSP remained open for several more years. It was in the later years of his career that Biddle began to invest significant financial resources not only in internal improvement projects, but also in the booming expansion of land, cotton, and slavery in the Old Southwest.

In 1837 and 1838, Biddle secretively dispatched agents into the South to buy up several million dollars worth of cotton with the notes of state-chartered banks, all in an effort to restore the nation's credit and pay off foreign debts owed to British merchant bankers. Critics called this an example of illegal cotton speculation and noted that the Bank's charter forbid the institution from purchasing commodities. Biddle also invested in and bailed out several state-chartered banks in the South whose capital was derived partially from slave mortgages. Some of these banks, including the Union Bank of Mississippi, financed the dispossession of Native Americans. Indeed, post-notes issued by the BUSP helped conclude one of the treaties that removed the

The Second Bank's twenty-year charter expired in April 1836, but Biddle worked with the Pennsylvania state legislature to prolong the institution as a state-chartered bank, the United States Bank of Pennsylvania (BUSP). The BUSP remained open for several more years. It was in the later years of his career that Biddle began to invest significant financial resources not only in internal improvement projects, but also in the booming expansion of land, cotton, and slavery in the Old Southwest.

In 1837 and 1838, Biddle secretively dispatched agents into the South to buy up several million dollars worth of cotton with the notes of state-chartered banks, all in an effort to restore the nation's credit and pay off foreign debts owed to British merchant bankers. Critics called this an example of illegal cotton speculation and noted that the Bank's charter forbid the institution from purchasing commodities. Biddle also invested in and bailed out several state-chartered banks in the South whose capital was derived partially from slave mortgages. Some of these banks, including the Union Bank of Mississippi, financed the dispossession of Native Americans. Indeed, post-notes issued by the BUSP helped conclude one of the treaties that removed the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

from their ancestral lands. In addition, Biddle purchased bonds in the Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas ( es, República de Tejas) was a sovereign state in North America that existed from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846, that bordered Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande in 1840 (another breakaway republic from Mex ...

, opposed territorial expansion into Oregon, and denounced abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

.

Meanwhile, in the absence of any regulatory oversight provided by a central bank, state-chartered banks in the West and South relaxed their lending standards, took greater on risks, maintained unsafe reserve ratios, and contributed to a credit bubble that eventually burst with the Panic of 1837. In 1839, after seeing his investment in cotton speculation backfire, Biddle resigned from his post as bank president, and in 1841, with the nation still reeling from depression, the Bank finally collapsed. Because the BUSP had issued loans to financial institutions and individual actors who pledged slave mortgages as collateral, the BUSP tragically became one of the largest owners of plantations, slaves, and slave-grown products in Mississippi as debtors rushed to repay creditors during the economic downturn of the early 1840s.

Biddle and a few of his colleagues had borrowed tens of thousands of dollars of cash from the BUSP on their own account without going through the normal lending process and without informing the Bank's board, and as a result, a grand jury indicted Biddle on charges of fraud in December 1841. Biddle was arrested and forced to pay compensation to creditors using the remainder of his personal fortune. The charges were later dismissed. On February 27, 1844, at the age of fifty-eight, Biddle died at the Andalusia estate from complications related to bronchitis and edema. Funds from his wife's family supported the ongoing civil lawsuits that plagued Biddle toward the end of his life.

Family

Nicholas's father,Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

, was noteworthy for his devotion to the cause of American independence and served alongside Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

on the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. His paternal uncle and namesake, Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle (January 8, 1786February 27, 1844) was an American financier who served as the third and last president of the Second Bank of the United States (chartered 1816–1836). Throughout his life Biddle worked as an editor, diplomat, au ...

(1750–1778), was a naval hero who died during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Another uncle, Edward Biddle

Edward Biddle (1738–1779) was an American soldier, lawyer, and statesman from Pennsylvania. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1774 and 1775 and a signatory to the Continental Association, which was drafted and adopted by that Co ...

, was a member of the First Continental Congress of 1774.

In 1811, Biddle married Jane Margaret Craig (1793–1856). The couple had six children, including

In 1811, Biddle married Jane Margaret Craig (1793–1856). The couple had six children, including Charles John Biddle

Charles John Biddle (April 30, 1819 – September 28, 1873) was an American soldier, lawyer, congressman, and newspaper editor.

Biography

Biddle was born and died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was the son of Nicholas Biddle, president of ...

, who served in the U.S. Army and in the U.S. House of Representatives, and Edward C. Biddle (1815–1872), with whom Nicholas worked in the international cotton trade during the late 1830s.

Nicholas had a younger brother, Thomas Biddle

Thomas Biddle (November 21, 1790 – August 29, 1831) was an American military hero during the War of 1812. Biddle is better known though for having been killed in a duel with Missouri Congressman Spencer Pettis.

Early life

Thomas Biddle was bo ...

, a War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

veteran who became a federal pension agent and director at the Second Bank's branch office in St. Louis, Missouri. On August 26, 1831, Thomas participated in a duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

with U.S. Representative Spencer Pettis

Spencer Darwin Pettis (1802August 28, 1831) was a U.S. Representative from Missouri and the fourth Missouri Secretary of State. He is best known, however, for being a participant in a fatal duel with Major Thomas Biddle. Pettis County, Missouri, ...

of Missouri. The duel took place on "Bloody Island", in the middle of the Mississippi River, near St. Louis. Because Thomas was nearsighted, the two exchanged shots from a perilously close distance of five feet. Pettis died within hours while Thomas succumbed to his wounds three days later. The origins of the duel can be traced to Pettis's criticism of Nicholas's management of the Bank, which Thomas defended. After an exchange of letters to the editor of a newspaper, Biddle accosted an ill Pettis in his hotel room. Pettis recovered and then challenged Thomas to a duel. Thomas Biddle

Thomas Biddle (November 21, 1790 – August 29, 1831) was an American military hero during the War of 1812. Biddle is better known though for having been killed in a duel with Missouri Congressman Spencer Pettis.

Early life

Thomas Biddle was bo ...

should not be confused with his second cousin, Thomas Biddle of Philadelphia, one of the city's leading exchange brokers.Howard Bodenhorn, State Banking in Early America: A New Economic History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 251

Nicholas Biddle Estate

The Nicholas Biddle Estate inBensalem Township, Pennsylvania

Bensalem Township is a township in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The township borders the northeastern section of Philadelphia and includes the communities of Andalusia, Bensalem, Bridgewater, Cornwells Heights, Eddington, Flushing, Oakford, ...

, also known as "Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

", is a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

, registered with the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

of the U.S. Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the man ...

.

Notes

References

Secondary sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Primary sources

* *Attribution

* *Further reading

* * * * * * * *External links

Article and portrait at "Discovering Lewis & Clark"

The Economic Historian: Encyclopedia of Economic History ''Nicholas Biddle''

*

Genealogy of Nicholas Biddle (1786–1844)

* James Kendall Hosmer — American history professor and librarian who edited reprinted and published Nicholas Biddle's account of Lewis and Clark's journal * Th

Biddle and Craig family Papers

including business and personal correspondence, are available for research use at the

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania is a long-established research facility, based in Philadelphia. It is a repository for millions of historic items ranging across rare books, scholarly monographs, family chronicles, maps, press reports and v ...

.

, -

{{DEFAULTSORT:Biddle, Nicholas

1786 births

1844 deaths

19th-century American politicians

American bankers

American editors

American people of English descent

Andrew Jackson

Nicholas

Nicholas is a male given name and a surname.

The Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Anglicanism, Anglican Churches celebrate Saint Nicholas every year on December 6, which is the name day for "Nicholas". In Greece, the n ...

Businesspeople from Philadelphia

Henry Clay

Members of the American Philosophical Society

Members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives

Pennsylvania Federalists

Pennsylvania state senators

Princeton University alumni

Burials at St. Peter's churchyard, Philadelphia

Lewis and Clark Expedition people