Nez Percé War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Nez Perce War was an

In 1855, at the

In 1855, at the  Tensions between Nez Perce and white settlers rose in 1876 and 1877. General

Tensions between Nez Perce and white settlers rose in 1876 and 1877. General

By the time Chief Joseph formally surrendered on October 5, 1877, 2:20 pm, European Americans described him as the principal chief of the Nez Perce and the strategist behind the Nez Perce's skilled fighting retreat. The American press referred to him as "the Red

By the time Chief Joseph formally surrendered on October 5, 1877, 2:20 pm, European Americans described him as the principal chief of the Nez Perce and the strategist behind the Nez Perce's skilled fighting retreat. The American press referred to him as "the Red

During the surrender negotiations, Howard and Miles had promised Joseph that the Nez Perce would be allowed to return to their reservation in Idaho. But, the commanding general of the Army,

During the surrender negotiations, Howard and Miles had promised Joseph that the Nez Perce would be allowed to return to their reservation in Idaho. But, the commanding general of the Army,

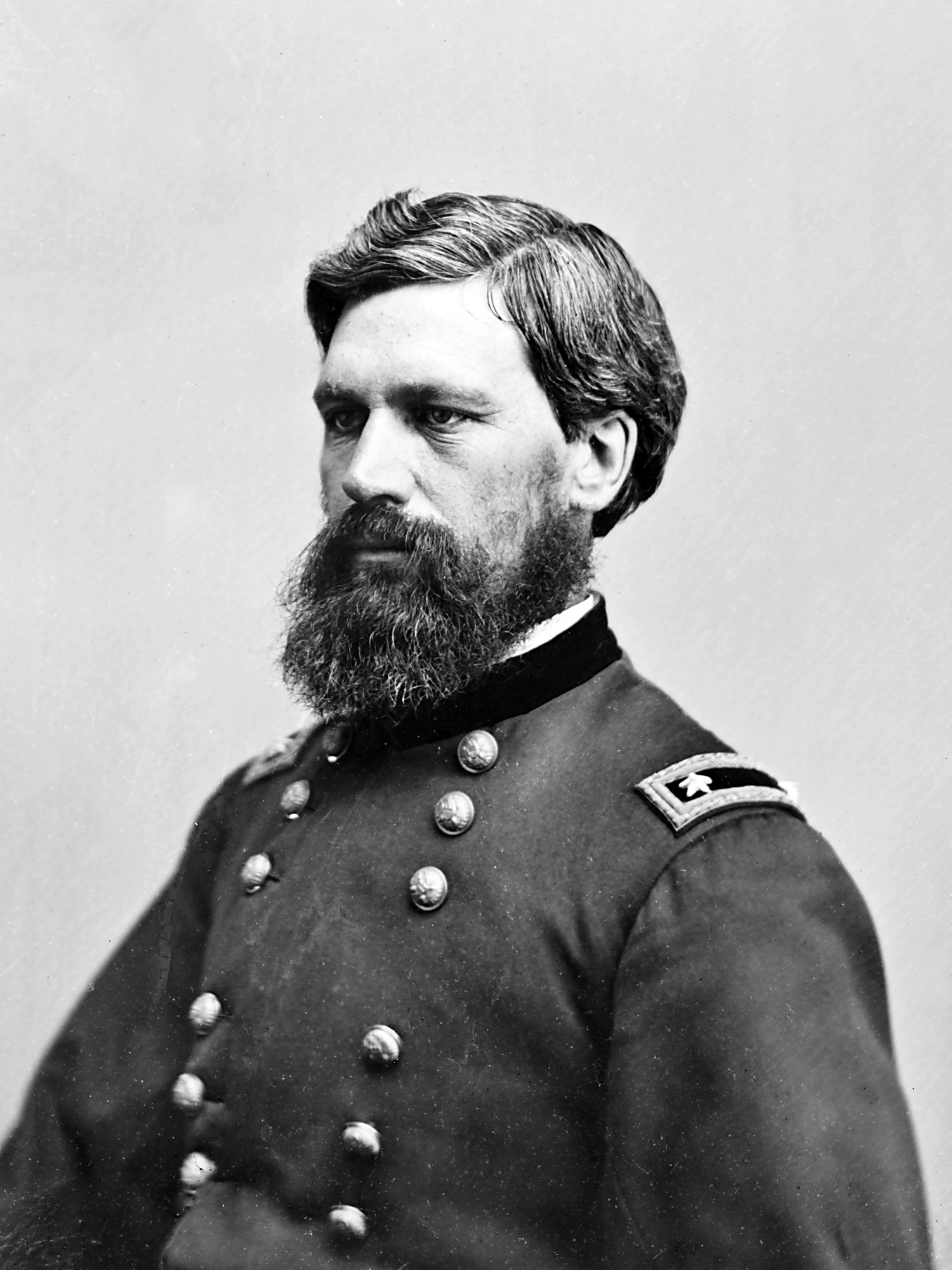

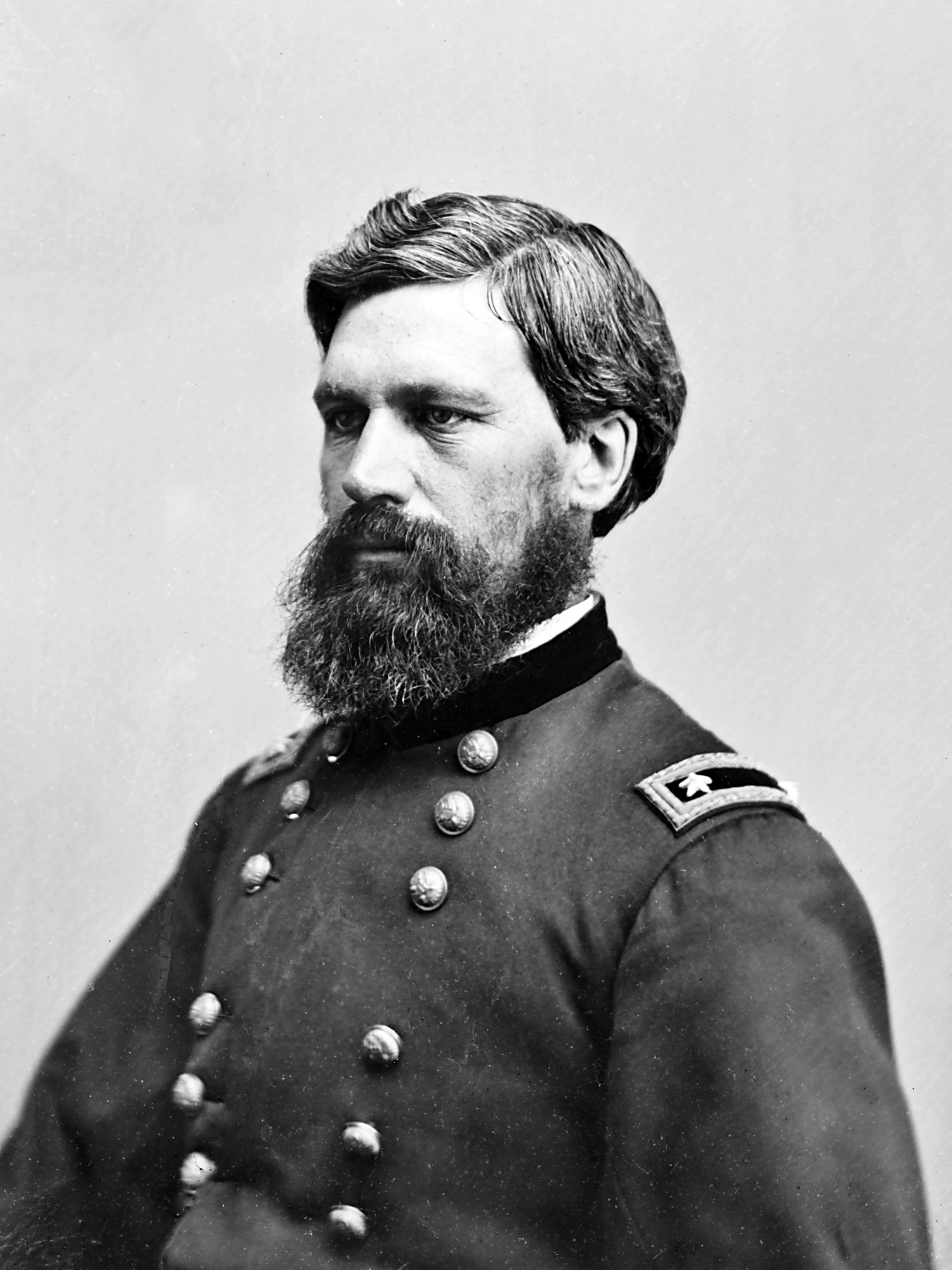

General Oliver Otis Howard was the commanding officer of U.S. troops pursuing the Nez Perce during the Nez Perce War of 1877. In 1881, he published an account of Joseph and the war, ''Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture'', depicting the Nez Perce campaign.Oliver Otis Howard, ''Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture''. Boston, MA: Lee and Shepard, 1881.

The Nez Perce perspective was represented by ''Yellow Wolf: His Own Story'', published in 1944 by

General Oliver Otis Howard was the commanding officer of U.S. troops pursuing the Nez Perce during the Nez Perce War of 1877. In 1881, he published an account of Joseph and the war, ''Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture'', depicting the Nez Perce campaign.Oliver Otis Howard, ''Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture''. Boston, MA: Lee and Shepard, 1881.

The Nez Perce perspective was represented by ''Yellow Wolf: His Own Story'', published in 1944 by

The Heart of the Appaloosa

describes the events of the Nez Perce War, highlighting the Nez Perce's skillful use of the

Online copy of ''Nez Perce Joseph: an account of his ancestors, his lands, his confederates, his enemies, his murders, his war, his pursuit and capture'' (1881)

Online copy of ''Yellow Wolf: His Own Story'' (1944)''Sacred Journey of the Nez Perce''

Documentary produced by

''Lewiston Morning Tribune''

- July 24, 1977 - special 18-page section on the centennial of Nez Perce War {{Authority control 1877 in the United States Conflicts in 1877 Indian wars of the American Old West Wars between the United States and Native Americans Native American history of Oregon Native American history of Idaho Native American history of Montana Native American history of Wyoming History of the Northwestern United States Nez Perce tribe

armed conflict

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

in 1877 in the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

that pitted several bands of the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans and their allies, a small band of the ''Palouse

The Palouse ( ) is a distinct geographic region of the northwestern United States, encompassing parts of north central Idaho, southeastern Washington, and, by some definitions, parts of northeast Oregon. It is a major agricultural area, primaril ...

'' tribe led by Red Echo (''Hahtalekin'') and Bald Head (''Husishusis Kute''), against the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

. Fought between June and October, the conflict stemmed from the refusal of several bands of the Nez Perce, dubbed "non-treaty Indians," to give up their ancestral lands in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

and move to an Indian reservation

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

in Idaho Territory

The Territory of Idaho was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1863, until July 3, 1890, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as Idaho.

History

1860s

The territory w ...

. This forced removal was in violation of the 1855 Treaty of Walla Walla

The Walla Walla Council (1855) was a meeting in the Pacific Northwest between the United States and sovereign tribal nations of the Cayuse, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Yakama. The council occurred on May 29 – June 11; ...

, which granted the tribe 7.5 million acres of their ancestral lands and the right to hunt and fish on lands ceded to the U.S. government.

After the first armed engagements in June, the Nez Perce embarked on an arduous trek north initially to seek help with the Crow tribe

The Crow, whose autonym is Apsáalooke (), also spelled Absaroka, are Native Americans living primarily in southern Montana. Today, the Crow people have a federally recognized tribe, the Crow Tribe of Montana, with an Indian reservation locate ...

. After the Crows' refusal of aid, they sought sanctuary with the Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakota ...

led by Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock I ...

, who had fled to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

in May 1877 to avoid capture following the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

.

The Nez Perce were pursued by elements of the U.S. Army with whom they fought a series of battles and skirmishes on a fighting retreat of . The war ended after a final five-day battle fought alongside Snake Creek at the base of Montana's Bears Paw Mountains

The Bears Paw Mountains (Bear Paw Mountains, Bear's Paw Mountains or Bearpaw Mountains) are an insular-montane island range in the Central Montana Alkalic Province in north-central Montana, United States, located approximately 10 miles south of ...

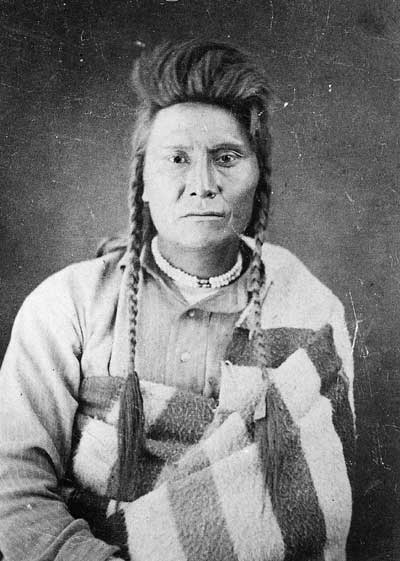

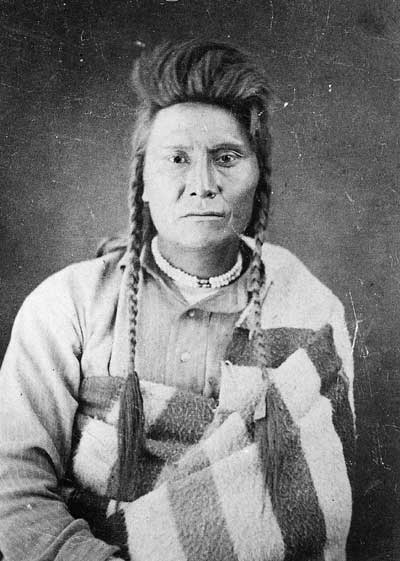

only from the Canada–US border. A large majority of the surviving Nez Perce represented by Chief Joseph

''Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt'' (or ''Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it'' in Americanist orthography), popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904), was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa ...

of the ''Wallowa'' band of Nez Perce, surrendered to Brigadier Generals Oliver Otis Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men agains ...

and Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the Spanish–American War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding Gen ...

. White Bird, of the ''Lamátta'' band of Nez Perce, managed to elude the Army after the battle and escape with an undetermined number of his band to Sitting Bull's camp in Canada. The 418 Nez Perce who surrendered, including women and children, were taken prisoner and sent by train to Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas.

Although Chief Joseph is the most well known of the Nez Perce leaders, he was not the sole overall leader. The Nez Perce were led by a coalition of several leaders from the different bands who comprised the "non-treaty" Nez Perce, including the Wallowa Ollokot

Ollokot (Ollikut álok'at) (born 1840s – died 30 September 1877), was a war leader of the Wallowa band of Nez Perce Indians and a leader of the young warriors in the Nez Perce War in 1877.

Early life

Ollokot was the son of Tuekakas or Old ...

, White Bird of the ''Lamátta'' band, Toohoolhoolzote of the ''Pikunin'' band, and Looking Glass

A mirror or looking glass is an object that Reflection (physics), reflects an image. Light that bounces off a mirror will show an image of whatever is in front of it, when focused through the lens of the eye or a camera. Mirrors reverse the ...

of the ''Alpowai'' band. Brigadier General Howard was head of the U.S. Army's Department of the Columbia

The Department of the Columbia was a major command ( Department) of the United States Army during the 19th century.

Formation

On July 27, 1865 the Military Division of the Pacific was created under Major General Henry W. Halleck, replacing the Dep ...

, which was tasked with forcing the Nez Perce onto the reservation and whose jurisdiction was extended by General William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

to allow Howard's pursuit. It was at the final surrender of the Nez Perce when Chief Joseph gave his famous "I Will No Longer Fight Forever More" speech, which was translated by the interpreter Arthur Chapman.

An 1877 ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' editorial discussing the conflict stated, "On our part, the war was in its origin and motive nothing short of a gigantic blunder and a crime".

Background

In 1855, at the

In 1855, at the Walla Walla Council

In American radio, film, television, and video games, walla is a sound effect imitating the murmur of a crowd in the background. A group of actors brought together in the post-production stage of film production to create this murmur is known a ...

, the Nez Perce were coerced by the federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

into giving up their ancestral lands and moving to the Umatilla Reservation in Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Ori ...

with the Walla Walla Walla Walla can refer to:

* Walla Walla people, a Native American tribe after which the county and city of Walla Walla, Washington, are named

* Place of many rocks in the Australian Aboriginal Wiradjuri language, the origin of the name of the town ...

, Cayuse, and Umatilla tribes. The tribes involved were so bitterly opposed to the terms of the plan that Isaac I. Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represen ...

, governor and superintendent of Indian affairs for the Washington Territory

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

, and Joel Palmer

General Joel Palmer (October 4, 1810 – June 9, 1881) was an American pioneer of the Oregon Territory in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. He was born in Canada, and spent his early years in New York and Pennsylvania before serving ...

, superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Ori ...

, signed the Nez Perce Treaty in 1855, which granted the Nez Perce the right to remain in a large portion of their own lands in Idaho, Washington, and Oregon territories, in exchange for relinquishing almost 5.5 million acres of their approximately 13 million acre homeland to the U.S. government for a nominal sum, with the caveat

Caveat may refer to

Latin phrases:

* ''Caveat lector'' ("let the reader beware")

* '' Caveat emptor'' ("let the buyer beware")

* '' Caveat venditor'' ("let the seller beware")

Other:

* CAVEAT, a Canadian lobby group

* ''Caveat'', an album by N ...

that they be able to hunt, fish. and pasture their horses etc. on unoccupied areas of their former land – the same rights to use public lands as Anglo-American

Anglo-Americans are people who are English-speaking inhabitants of Anglo-America. It typically refers to the nations and ethnic groups in the Americas that speak English as a native language, making up the majority of people in the world who spe ...

citizens of the territories.

The newly established Nez Perce Indian reservation

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

was in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington territories. Under the terms of the treaty, no white settlers were allowed on the reservation without the permission of the Nez Perce. However, in 1860 gold was discovered near present-day Pierce, Idaho

Pierce is a city in the northwest United States, located in Clearwater County, Idaho. The population was 508 at the 2010 census, down from 617 in 2000.

, and 5,000 gold-seekers rushed onto the reservation, illegally founding the downstream city of Lewiston as a supply depot on Nez Perce land. Ranchers and farmers followed the miners, and the U.S. government failed to keep settlers out of Indian lands. The Nez Perce were incensed at the failure of the U.S. government to uphold the treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

, and at settlers who squatted

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

on their land and plowed up their camas prairies, which they depended on for subsistence.

In 1869, a group of Nez Perce were coerced into signing away 90% of their reservation to the U.S., leaving only in Idaho Territory. Under the terms of the treaty, all Nez Perce were to move onto the new and much smaller reservation east of Lewiston. A large number of Nez Perce, however, did not accept the validity of the treaty, refused to move to the reservation, and remained on their traditional lands. The Nez Perce who approved the treaty were mostly Christian; the opponents mostly followed the traditional religion. The "non-treaty" Nez Perce included the band of Chief Joseph, who lived in the Wallowa Wallowa may refer to:

Places

*Wallowa, Oregon

*Wallowa County, Oregon

*Wallowa Lake

*Wallowa Lake State Park

*Wallowa Mountains

*Wallowa River

Other

*''Acacia calamifolia'', a shrub or tree

*''Acacia euthycarpa'', a shrub or tree

* ''The Wallo ...

valley in northeastern Oregon. Disputes there with white farmers and ranchers led to the murders of several Nez Perce, and the murderers were never prosecuted.

Tensions between Nez Perce and white settlers rose in 1876 and 1877. General

Tensions between Nez Perce and white settlers rose in 1876 and 1877. General Oliver Otis Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men agains ...

called a council in May 1877 and ordered the non-treaty bands to move to the reservation, setting an impossible deadline of 30 days. Howard humiliated the Nez Perce by jailing their old leader, Toohoolhoolzote, who spoke against moving to the reservation. The other Nez Perce leaders, including Chief Joseph, considered military resistance to be futile; they agreed to the move and reported as ordered to Fort Lapwai

Fort Lapwai (1862–1884), was a Federal government of the United States, federal Fortification#North America, fort in present-day Lapwai, Idaho, Lapwai in North Central Idaho, north central Idaho, United States. On the Nez Perce people#Nez P ...

, Idaho Territory. By June 14, 1877 about 600 Nez Perce from Joseph's and White Bird's bands had gathered on the Camas Prairie

The name camas prairie refers to several different geographical areas in the western United States which were named for the native perennial camassia or camas. The culturally and scientitifcally significant of these areas lie within Idaho and Monta ...

, six miles (10 km) west of present-day Grangeville.West, Elliott, pp. 5–6

On June 13, shortly before the deadline for removing onto the reservation, White Bird's band held a tel-lik-leen ceremony at the Tolo Lake camp in which the warriors paraded on horseback in a circular movement around the village while individually boasting of their battle prowess and war deeds. According to Nez Perce accounts, an aged warrior named Hahkauts Ilpilp (Red Grizzly Bear) challenged the presence in the ceremony of several young participants whose relatives' deaths at the hands of whites had gone unavenged. One named Wahlitits (Shore Crossing) was the son of Eagle Robe, who had been shot to death by Lawrence Ott three years earlier. Thus humiliated and apparently fortified with liquor, Shore Crossing and two of his cousins, Sarpsisilpilp (Red Moccasin Top) and Wetyemtmas Wahyakt (Swan Necklace), set out for the Salmon River settlements on a mission of revenge. On the following evening, June 14, 1877, Swan Necklace returned to the lake to announce that the trio had killed four white men and wounded another man. Inspired by the war furor, approximately sixteen more young men rode off to join Shore Crossing in raiding the settlements.

Joseph and his brother Ollokot were away from the camp during the raids on June 14 and 15. When they arrived at the camp the next day, most of the Nez Perce had departed for a campsite on White Bird Creek to await the response of General Howard. Joseph considered an appeal for peace to the Whites, but realized it would be useless after the raids. Meanwhile, Howard mobilized his military force and sent out 130 men, including 13 friendly Nez Perce scouts, under the command of Captain David Perry to punish the Nez Perce and force them onto the reservation. Howard anticipated that his soldiers "will make short work of it." The Nez Perce defeated Perry at the Battle of White Bird Canyon

The Battle of White Bird Canyon was fought on June 17, 1877, in Idaho Territory. White Bird Canyon was the opening battle of the Nez Perce War between the Nez Perce Indians and the United States. The battle was a significant defeat of the U.S. ...

and began their long flight eastward to escape from the U.S. soldiers.

War

Joseph and White Bird were joined by Looking Glass's band and, after several battles and skirmishes in Idaho during the next month, approximately 250 Nez Perce warriors, and 500 women and children, along with more than 2000 head of horses and other livestock, began a remarkable fighting retreat. They crossed fromIdaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

over Lolo Pass into Montana Territory

The Territory of Montana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1864, until November 8, 1889, when it was admitted as the 41st state in the Union as the state of Montana.

Original boundaries

T ...

, traveling southeast, dipping into Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

and then back north into Montana,Malone, p. 135West, p. 4 roughly . They attempted to seek refuge with the Crow Nation

The Crow, whose Exonym and endonym, autonym is Apsáalooke (), also spelled Absaroka, are Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans living primarily in southern Montana. Today, the Crow people have a federally recognized tribe, th ...

, but, rejected by the Crow, ultimately decided to try to reach safety in Canada.

A small number of Nez Perce fighters, probably fewer than 200, defeated or held off larger forces of the U.S. Army in several battles. The most notable was the two-day Battle of the Big Hole

The Battle of the Big Hole was fought in Montana Territory, August 9–10, 1877, between the United States Army and the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans during the Nez Perce War. Both sides suffered heavy casualties. The Nez Perce withd ...

in southwestern Montana territory, a battle with heavy casualties on both sides, including many women and children on the Nez Perce side. Until the Big Hole the Nez Perce had the naive view that they could end the war with the U.S. on terms favorable, or at least acceptable, to themselves. Afterwards, the war "increased in ferocity and tempo. From then on all white men were bound to be their enemies and yet their own fighting power had been severely reduced."

The war came to an end when the Nez Perce stopped to make camp and rest on the prairie adjacent to Snake Creek in the foothills of the north slope of the Bear's Paw Mountains

The Bears Paw Mountains (Bear Paw Mountains, Bear's Paw Mountains or Bearpaw Mountains) are an insular-montane island range in the Central Montana Alkalic Province in north-central Montana, United States, located approximately 10 miles south of ...

in Montana Territory, only from the Canada–United States border

The border between Canada and the United States is the longest international border in the world. The terrestrial boundary (including boundaries in the Great Lakes, Atlantic, and Pacific coasts) is long. The land border has two sections: Can ...

.

They believed that they had shaken off Howard and their pursuers, but they were unaware that the recently promoted Brigadier General Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the Spanish–American War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding Gen ...

in command of the newly created District of the Yellowstone had been dispatched from the Tongue River Cantonment to find and intercept them. Miles led a combined force made up of units of the Fifth Infantry, and Second Cavalry and the Seventh Cavalry. Accompanying the troops were Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakota ...

and Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

Indian Scouts, many of whom had fought against the Army only a year prior during the Sioux War.

They made a surprise attack upon the Nez Perce camp on the morning of September 30. After a three-day standoff, Howard arrived with his command, on October 3 and the stalemate was broken. Chief Joseph surrendered on October 5, 1877,Malone, et al. ''Montana'', p. 138 and declared in his famous surrender speech that he would "fight no more forever."

In total, the Nez Perce engaged 2,000 American soldiers of different military units, as well as their Indian auxiliaries. They fought "eighteen engagements, including four major battles and at least four fiercely contested skirmishes." Many people praised the Nez Perce for their exemplary conduct and skilled fighting ability. The Montana newspaper ''New North-West'' stated: "Their warfare since they entered Montana has been almost universally marked so far by the highest characteristics recognized by civilized nations. "

Surrender

By the time Chief Joseph formally surrendered on October 5, 1877, 2:20 pm, European Americans described him as the principal chief of the Nez Perce and the strategist behind the Nez Perce's skilled fighting retreat. The American press referred to him as "the Red

By the time Chief Joseph formally surrendered on October 5, 1877, 2:20 pm, European Americans described him as the principal chief of the Nez Perce and the strategist behind the Nez Perce's skilled fighting retreat. The American press referred to him as "the Red Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

" for the military prowess attributed to him, but the Nez Perce bands involved in the war did not consider him a war chief. Joseph's younger brother, Ollokot; Poker Joe

Most popularly known for his contribution to the Nez Perce people during the Nez Perce War of 1877, Poker Joe (18?? - 1877) went by several monikers to include Little Tobacco, Hototo, and Nez Perces Joe.Brown, Mark H. “Yellowstone Tourists and th ...

, and Looking Glass of the Alpowai band were among those who formulated the fighting strategy and tactics and led the warriors in battle, while Joseph was responsible for guarding the camp.

Chief Joseph became immortalized by his famous speech:

''I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzoote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say, "Yes" or "No." He who led the young men llokotis dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are -- perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.''Joseph's speech was translated by the interpreter Arthur Chapman and was transcribed by Howard's aide-de-camp Lieutenant C. E. S. Wood. Among other vocations, Wood was a writer and a poet. His poem, "The Poet in the Desert" (1915), was a literary success, and some critics have suggested that he may have taken

poetic license

Artistic license (alongside more contextually-specific derivative terms such as poetic license, historical license, dramatic license, and narrative license) refers to deviation from fact or form for artistic purposes. It can include the alterat ...

and embellished Joseph's speech.

Aftermath

During the surrender negotiations, Howard and Miles had promised Joseph that the Nez Perce would be allowed to return to their reservation in Idaho. But, the commanding general of the Army,

During the surrender negotiations, Howard and Miles had promised Joseph that the Nez Perce would be allowed to return to their reservation in Idaho. But, the commanding general of the Army, William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

, overruled them and directed that the Nez Perce were sent to Kansas. "I believed General Miles, or I never would have surrendered," Chief Joseph said afterward.

Miles marched his captives to the Tongue River Cantonment in southeast Montana Territory, where they arrived on October 23, 1877, and were held until Oct. 31. The able-bodied warriors were marched out to Fort Buford

Fort Buford was a United States Army Post at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers in Dakota Territory, present day North Dakota, and the site of Sitting Bull's surrender in 1881.Ewers, John C. (1988): "When Sitting Bull Surrendere ...

, at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers. On November 1, women, children, the ill and the wounded set out for Fort Buford in fourteen Mackinaw boat

The Mackinaw boat is a loose, non-standardized term for a light, open sailboat used in the interior of North America during the fur trading era. Within this term two different ''Mackinaw boats'' evolved: one for use on the upper Great Lakes, and t ...

s.

Between November 8 and 10, the Nez Perce left Fort Buford for Custer's post command at the time of his death; Fort Abraham Lincoln

Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park is a North Dakota state park located south of Mandan, North Dakota, United States. The park is home to the replica Mandan On-A-Slant Indian Village and reconstructed military buildings including the Custer House.

...

across the Missouri River from Bismarck in the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of No ...

. About two hundred left in the mackinaws on November 9 guarded by two companies of the First Infantry; the rest traveled on horseback escorted by troops of the Seventh Cavalry en route to their winter quarters.

A majority of Bismarck's citizens turned out to welcome the Nez Perce prisoners, providing a lavish buffet for them and their troop escort. On November 23, the Nez Perce prisoners had their lodges and equipment loaded into freight cars and themselves into eleven rail coaches for the trip via train to Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

in Kansas.

Over the protests to Sherman by the commander of the Fort, the Nez Perce were forced to live in a swampy bottomland. One author described the effects on the Nez Perce refugees: "the 400 miserable, helpless, emaciated specimens of humanity, subjected for months to the malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

l atmosphere of the river bottom."

Chief Joseph went to Washington in January 1879 to plead that his people be allowed to return to Idaho or, at least, be given land in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

, what would become Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

. He met with the President and Congress, and his account was published in the North American Review

The ''North American Review'' (NAR) was the first literary magazine in the United States. It was founded in Boston in 1815 by journalist Nathan Hale and others. It was published continuously until 1940, after which it was inactive until revived a ...

. While he was greeted with acclaim, the U.S. government did not grant his petition due to fierce opposition in Idaho. Instead, Joseph and the Nez Perce were sent to Oklahoma and eventually located on a small reservation near Tonkawa, Oklahoma

Tonkawa is a city in Kay County, Oklahoma, United States, along the Salt Fork Arkansas River. The population was 3,216 at the 2010 census, a decline of 2.5 percent from the figure of 3,299 in 2000.

History

Named after the Tonkawa tribe, the city ...

. Conditions in "the hot country" were hardly better than they had been at Leavenworth.

In 1885, Joseph and 268 surviving Nez Perce were finally allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest. Joseph, however, was not permitted to return to the Nez Perce reservation but instead settled at the Colville Indian Reservation

The Colville Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation in the northwest United States, in north central Washington, inhabited and managed by the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, which is federally recognized.

Established in ...

in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

. He died there in 1904.

Depictions in media

Books

General Oliver Otis Howard was the commanding officer of U.S. troops pursuing the Nez Perce during the Nez Perce War of 1877. In 1881, he published an account of Joseph and the war, ''Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture'', depicting the Nez Perce campaign.Oliver Otis Howard, ''Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture''. Boston, MA: Lee and Shepard, 1881.

The Nez Perce perspective was represented by ''Yellow Wolf: His Own Story'', published in 1944 by

General Oliver Otis Howard was the commanding officer of U.S. troops pursuing the Nez Perce during the Nez Perce War of 1877. In 1881, he published an account of Joseph and the war, ''Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture'', depicting the Nez Perce campaign.Oliver Otis Howard, ''Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture''. Boston, MA: Lee and Shepard, 1881.

The Nez Perce perspective was represented by ''Yellow Wolf: His Own Story'', published in 1944 by Lucullus Virgil McWhorter

Lucullus Virgil McWhorter (January 29, 1860 – October 10, 1944) was an American farmer and frontiersman who documented the historical Native American tribes in West Virginia and the modern-day Plateau Native Americans in Washington state. After ...

, who had interviewed Yellow Wolf, a Nez Perce warrior. This book is very critical of the U.S. military's role in the war, and especially of General Howard. McWhorter also wrote ''Hear Me, My Chiefs!'', published after his death. It was based on documentary sources and had material supporting the historical claims of each side.

The fifth volume of William T. Vollmann

William Tanner Vollmann (born July 28, 1959) is an American novelist, journalist, war correspondent, short story writer, and essayist. He won the 2005 National Book Award for Fiction with the novel ''Europe Central''.

's '' Seven Dreams'' cycle, ''The Dying Grass'', offers a detailed account of the conflict.

Television

The 1975David Wolper

David Lloyd Wolper (January 11, 1928 – August 10, 2010) was an American television and film producer, responsible for shows such as ''Roots'', ''The Thorn Birds'', and ''North and South'', and the theatrically-released films ''L.A. Confident ...

historical teledrama ''I Will Fight No More Forever

''I Will Fight No More Forever'' is a 1975 made-for-television Western film starring James Whitmore as General Oliver O. Howard and Ned Romero as Chief Joseph. It is a dramatization of Chief Joseph's resistance to the U.S. government's forcibl ...

,'' starring Ned Romero

Ned Romero (December 4, 1926 – November 4, 2017) was an American actor and opera singer who appeared in television and film.

Early childhood and education

Romero was born on December 4, 1926 in Franklin, Louisiana, the seat of St. Mary Pa ...

as Joseph and James Whitmore

James Allen Whitmore Jr. (October 1, 1921 – February 6, 2009) was an American actor. He received numerous accolades, including a Golden Globe Award, a Grammy Award, a Primetime Emmy Award, a Theatre World Award, and a Tony Award, plus two Aca ...

as General Howard, was well received at a time when Native American issues were receiving wider exposure in the culture. The drama was notable for attempting to present a balanced view of the events: the leadership pressures on Joseph were juxtaposed with the Army's having to carry out an unpopular task while an action-hungry press establishment looked on.

Song

Folk singer Fred Small's 1983 songThe Heart of the Appaloosa

describes the events of the Nez Perce War, highlighting the Nez Perce's skillful use of the

Appaloosa

The Appaloosa is an American horse breed best known for its colorful spotted coat pattern. There is a wide range of body types within the breed, stemming from the influence of multiple breeds of horses throughout its history. Each horse's colo ...

in battle and in flight. The lyrics identify Chief Joseph

''Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt'' (or ''Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it'' in Americanist orthography), popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904), was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa ...

's Nez Perce name, which translates as "Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain," and quotes extensively from his "I will fight no more forever" speech.

Texas country

Texas country music (more popularly known just as Texas country or Texas music) is a rapidly growing subgenre of country music from Texas. Texas country is a unique style of Western music and is often associated with other distinct neighboring s ...

band Micky & the Motorcars released the song "From Where the Sun Now Stands" on their 2014 album ''Hearts from Above.'' The song chronicles the flight of the Nez Perce through Idaho and Montana.

See also

*Indian Campaign Medal

The Indian Campaign Medal is a decoration established by War Department General Orders 12, 1907.

* Big Hole National Battlefield

Big Hole National Battlefield preserves a battlefield in the western United States, located in Beaverhead County, Montana. In 1877, the Nez Perce fought a delaying action against the U.S. Army's 7th Infantry Regiment here on August 9 and 10, durin ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * Nichols, Roger L. (2013). ''Warrior Nations: The United States and Indian Peoples.'' Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. * * *External links

Online copy of ''Nez Perce Joseph: an account of his ancestors, his lands, his confederates, his enemies, his murders, his war, his pursuit and capture'' (1881)

Online copy of ''Yellow Wolf: His Own Story'' (1944)

Documentary produced by

Montana PBS

Montana PBS is the PBS member public television network for the U.S. state of Montana. It is a joint venture between Montana State University (MSU) and the University of Montana (UM). The network is headquartered in the Visual Communications Bu ...

''Lewiston Morning Tribune''

- July 24, 1977 - special 18-page section on the centennial of Nez Perce War {{Authority control 1877 in the United States Conflicts in 1877 Indian wars of the American Old West Wars between the United States and Native Americans Native American history of Oregon Native American history of Idaho Native American history of Montana Native American history of Wyoming History of the Northwestern United States Nez Perce tribe