Nez Perce People on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Nez Percé (;

The Nez Perce Flight for Justice

, ''American Heritage'', Fall 2008. They are one of five federally recognized tribes in the state of Idaho. The Nez Perce only own 12% of their own reservation and some Nez Perce lease land to farmers or loggers. Today, hatching, harvesting and eating salmon is an important cultural and economic strength of the Nez Perce through full ownership or co-management of various salmon fish hatcheries, such as the

Their name for themselves is ''Nimíipuu'' (pronounced ), meaning, "The People", in their language, part of the

Their name for themselves is ''Nimíipuu'' (pronounced ), meaning, "The People", in their language, part of the

The Nez Perce territory at the time of Lewis and Clark (1804–1806) was approximately and covered parts of present-day

The Nez Perce territory at the time of Lewis and Clark (1804–1806) was approximately and covered parts of present-day

The semi-sedentary Nez Percés were

The semi-sedentary Nez Percés were  The first fishing of the season was accompanied by prescribed rituals and a ceremonial feast known as "''kooyit''". Thanksgiving was offered to the Creator and to the fish for having returned and given themselves to the people as food. In this way, it was hoped that the fish would return the next year.

Like salmon, plants contributed to traditional Nez Perce culture in both material and spiritual dimensions.

Aside from fish and game, Plant foods provided over half of the dietary calories, with winter survival depending largely on dried roots, especially Kouse, or "''qáamsit''" (when fresh) and "''qáaws''" (when peeled and dried) (

The first fishing of the season was accompanied by prescribed rituals and a ceremonial feast known as "''kooyit''". Thanksgiving was offered to the Creator and to the fish for having returned and given themselves to the people as food. In this way, it was hoped that the fish would return the next year.

Like salmon, plants contributed to traditional Nez Perce culture in both material and spiritual dimensions.

Aside from fish and game, Plant foods provided over half of the dietary calories, with winter survival depending largely on dried roots, especially Kouse, or "''qáamsit''" (when fresh) and "''qáaws''" (when peeled and dried) ( The Nez Perce believed in spirits called ''

The Nez Perce believed in spirits called ''

The Nez Perce were one of the tribal nations at the

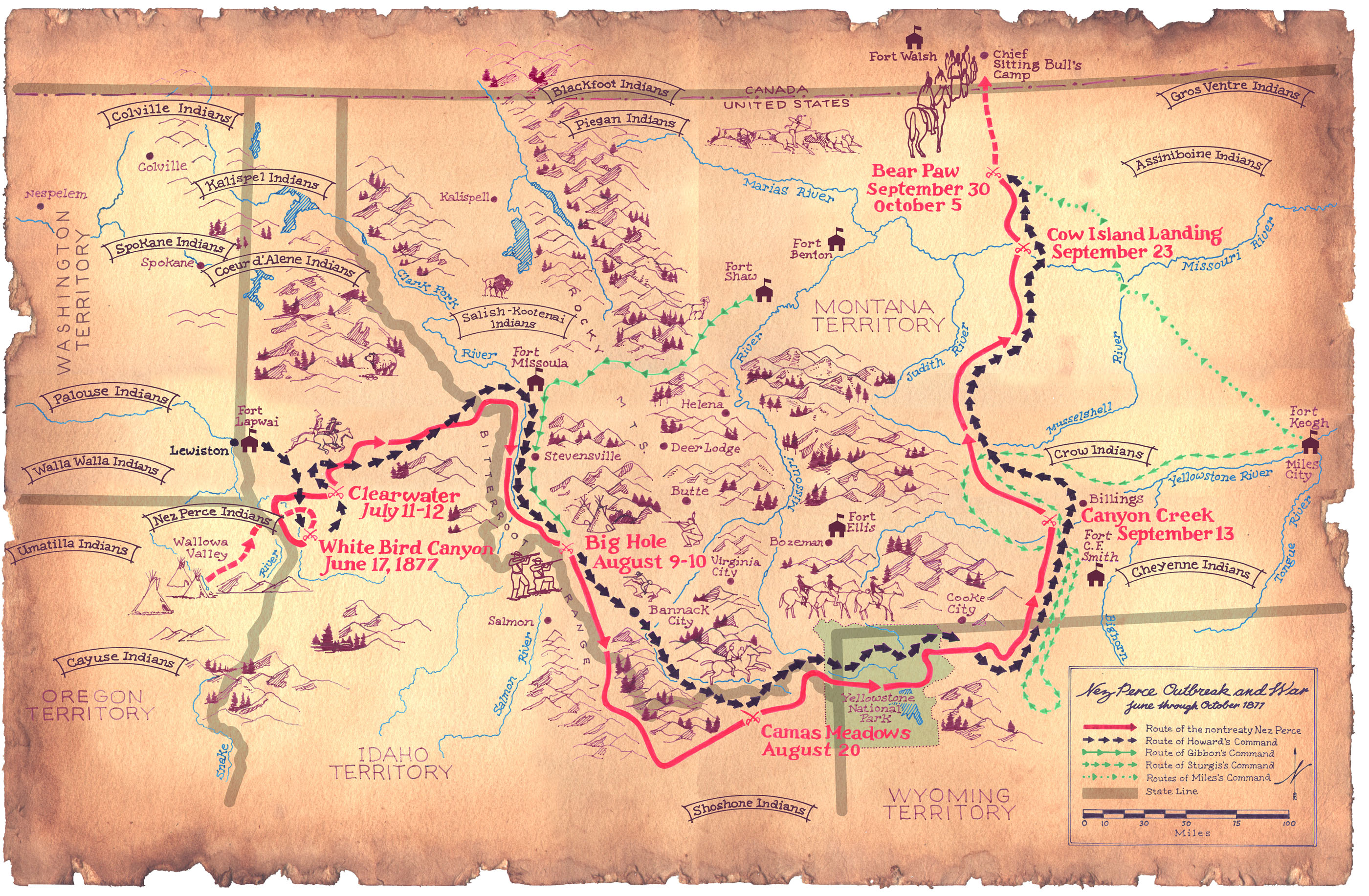

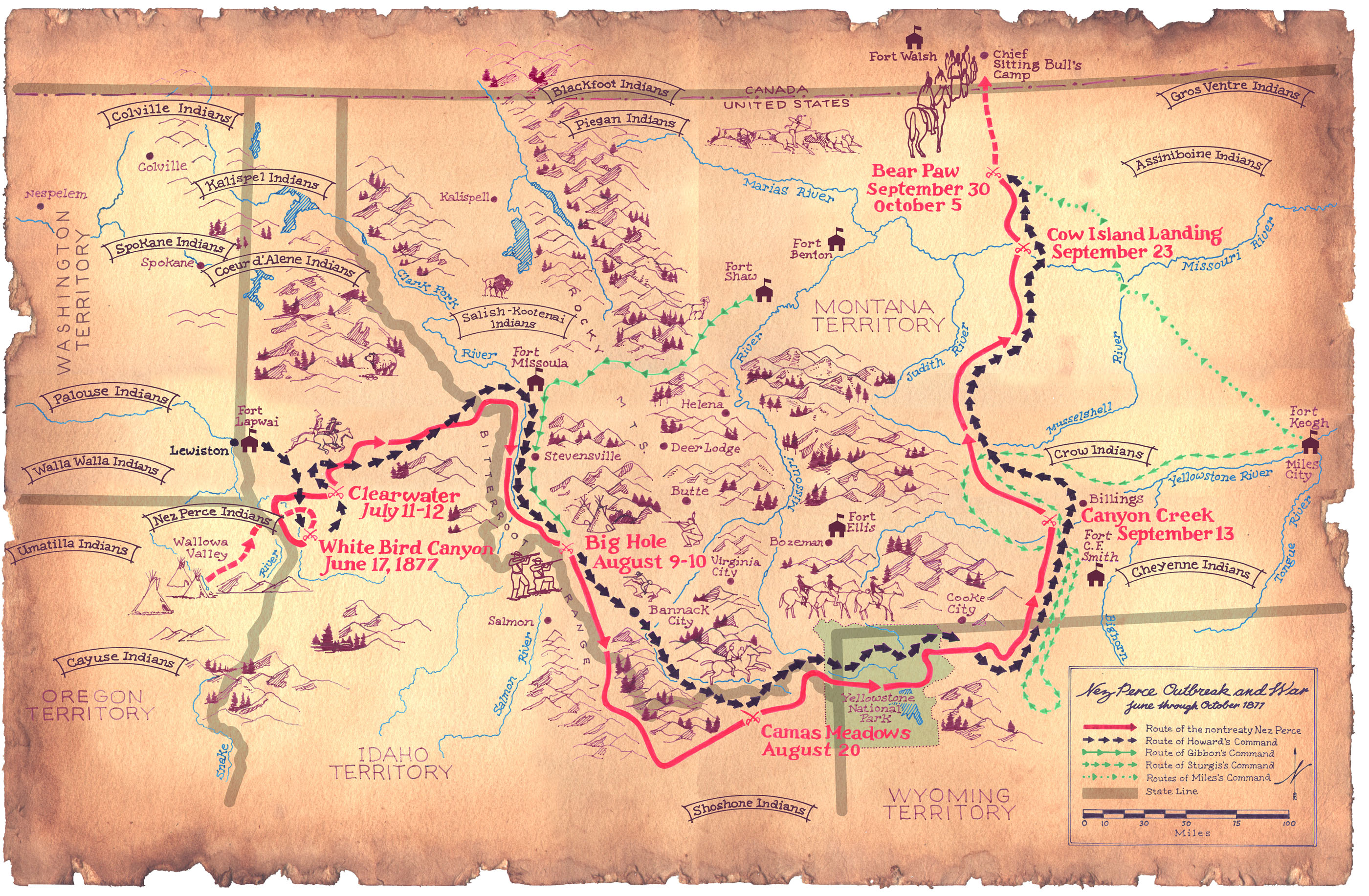

The Nez Perce were one of the tribal nations at the  The Nez Perce were pursued by over 2,000 soldiers of the

The Nez Perce were pursued by over 2,000 soldiers of the

In 1994 the Nez Perce tribe began a breeding program, based on crossbreeding the

In 1994 the Nez Perce tribe began a breeding program, based on crossbreeding the

The current tribal lands consist of a reservation in

The current tribal lands consist of a reservation in

File:Chief.Lawyer.1861.jpg,

Official tribal site

Friends of the Bear Paw, Big Hole & Canyon Creek Battlefields

Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission

– member tribes include the Nez Perce.

Nez Perce National Historic Trail

– University of Washington Digital Collection {{authority control Federally recognized tribes in the United States History of the Northwestern United States Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau Native American tribes in Idaho Native American tribes in Montana Native American tribes in Oregon Native American tribes in Washington (state)

autonym

Autonym may refer to:

* Autonym, the name used by a person to refer to themselves or their language; see Exonym and endonym

* Autonym (botany), an automatically created infrageneric or infraspecific name

See also

* Nominotypical subspecies, in zo ...

in Nez Perce language

Nez Perce, also spelled Nez Percé or called Nimipuutímt (alternatively spelled ''Nimiipuutímt'', ''Niimiipuutímt'', or ''Niimi'ipuutímt''), is a Sahaptian language related to the several dialects of Sahaptin (note the spellings ''-ian'' vs ...

: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau

The Columbia Plateau is a geologic and geographic region that lies across parts of the U.S. states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. It is a wide flood basalt plateau between the Cascade Range and the Rocky Mountains, cut through by the Columbi ...

in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, Kenneth and Alan Marshall. 1980. "Villages, Demography and Subsistence Intensification on the Southern Columbia Plateau". ''North American Archeologist'', 2(1): 25–52."

Members of the Sahaptin language group, the Nimíipuu were the dominant people of the Columbia Plateau

The Columbia Plateau is a geologic and geographic region that lies across parts of the U.S. states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. It is a wide flood basalt plateau between the Cascade Range and the Rocky Mountains, cut through by the Col ...

for much of that time, especially after acquiring the horses that led them to breed the appaloosa horse

The Appaloosa is an American horse breed best known for its colorful spotted coat pattern. There is a wide range of body types within the breed, stemming from the influence of multiple breeds of horses throughout its history. Each horse's col ...

in the 18th century.

Prior to first contact with European colonial

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense bega ...

people the Nimiipuu were economically and culturally influential in trade and war, interacting with other indigenous nations in a vast network from the western shores of Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, the high plains of Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

, and the northern Great Basin

The Great Basin is the largest area of contiguous endorheic basin, endorheic watersheds, those with no outlets, in North America. It spans nearly all of Nevada, much of Utah, and portions of California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, and Baja California ...

in southern Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

and northern Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

.

French explorers and trappers indiscriminately used and popularized the name "Nez Percé" for the Nimíipuu and nearby Chinook. The name translates as " pierced nose", but only the Chinook used that form of body modification.Slickpoo, Allen P., Sr. 1973. ''Noon Nee-Me-Poo (We, The Nez Perces): Culture and History of the Nez Perces, Vol. 1''. Lewiston, Idaho: The Nez Percé Tribe of Idaho.

Cut off from most of their horticultural sites throughout the Camas Prairie

The name camas prairie refers to several different geographical areas in the western United States which were named for the native perennial camassia or camas. The culturally and scientitifcally significant of these areas lie within Idaho and Monta ...

by an 1863 treaty (subsequently known as the "Thief Treaty" or "Steal Treaty" among the Nimiipuu), confinement to reservations in Idaho, Washington and Oklahoma Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

after the Nez Perce War

The Nez Perce War was an armed conflict in 1877 in the Western United States that pitted several bands of the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans and their allies, a small band of the ''Palouse'' tribe led by Red Echo (''Hahtalekin'') and ...

of 1877, and Dawes Act of 1887

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the Pres ...

land allotments, the Nez Perce remain as a distinct culture and political economic influence within and outside their reservation.Colombi, Benedict. 2012. "Salmon and the Adaptive Capacity of Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) Culture to Cope with Change". ''American Indian Quarterly'', 36(1): 75–97.

As a federally recognized tribe

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

, the Nez Perce Tribe of Idaho govern their Native reservation in Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

through a central government headquartered in Lapwai

Lapwai is a city in the Northwestern United States, northwest United States, in Nez Perce County, Idaho, Nez Perce County, Idaho. Its population was 1,137 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, and it is the seat of government of the Nez Pe ...

known as the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee (NPTEC).R. David Edmunds,The Nez Perce Flight for Justice

, ''American Heritage'', Fall 2008. They are one of five federally recognized tribes in the state of Idaho. The Nez Perce only own 12% of their own reservation and some Nez Perce lease land to farmers or loggers. Today, hatching, harvesting and eating salmon is an important cultural and economic strength of the Nez Perce through full ownership or co-management of various salmon fish hatcheries, such as the

Kooskia National Fish Hatchery

Kooskia National Fish Hatchery is a "mitigation" hatchery located on the Clearwater River within the Nez Perce Indian Reservation near Kooskia, in north-central Idaho. Construction began in 1966 by the Army Corps of Engineers. With funding p ...

in Kooskia or the Dworshak National Fish Hatchery

Dworshak National Fish Hatchery is a mitigation hatchery located on the Clearwater River within the Nez Perce Reservation near Ahsahka, in north-central Idaho, United States. It was constructed in 1969 by the Army Corps of Engineers, and is co-ma ...

in Orofino.Nez Perce Tribe (2003). ''Treaties: Nez Perce Perspectives''. The Nez Perce Tribe Environmental Restoration & Waste Management Program, in association with the United States Department of Energy. Lewiston, Idaho: Confluence Press.

Some still speak their traditional language, and the Tribe owns and operates two casinos along the Clearwater River (in Kamiah and east of Lewiston), health clinics, a police force and court, community centers, salmon fisheries, radio station, and other institutions that promote economic and cultural self-determination.

Name and history

Their name for themselves is ''Nimíipuu'' (pronounced ), meaning, "The People", in their language, part of the

Their name for themselves is ''Nimíipuu'' (pronounced ), meaning, "The People", in their language, part of the Sahaptin

The Sahaptin are a number of Native American tribes who speak dialects of the Sahaptin language. The Sahaptin tribes inhabited territory along the Columbia River and its tributaries in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Sahaptin-s ...

family.Aoki, Haruo. ''Nez Perce Dictionary''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. .

''Nez Percé'' is an exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

given by French Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

rs who visited the area regularly in the late 18th century, meaning literally "pierced nose". English-speaking traders and settlers adopted the name in turn. Since the late 20th century, the Nez Perce identify most often as Niimíipuu in Sahaptin. This has also been spelled Nee-Me-Poo. The Lakota/ Dakota named them the ''Watopala'', or ''Canoe'' people, from ''Watopa''. However, after Nez Perce became a more common name, they changed it to ''Watopahlute''. This comes from ''pahlute'', nasal passage, and is simply a play on words. If translated literally, it would come out as either "Nasal Passage of the Canoe" (Watopa-pahlute) or "Nasal Passage of the Grass" (Wato-pahlute). The Assiniboine called them ''Pasú oȟnógA wįcaštA'', the Arikara ''sinitčiškataríwiš''. The tribe also uses the term "Nez Perce", as does the United States Government in its official dealings with them, and contemporary historians. Older historical ethnological

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology). ...

works and documents use the French spelling of ''Nez Percé'', with the diacritic

A diacritic (also diacritical mark, diacritical point, diacritical sign, or accent) is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek (, "distinguishing"), from (, "to distinguish"). The word ''diacriti ...

. The original French pronunciation is , with three syllables.

The interpreters Sacagawea and Toussaint Charbonneau of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

mistakenly identified this people as the Nez Perce when the team encountered the tribe in 1805. Writing in 1889, anthropologist Alice Fletcher, who the U.S. government had sent to Idaho to allot the Nez Perce Reservation, explained the mistaken naming. She wrote,

In his journals, William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

referred to the people as the Chopunnish , a transliteration of a Sahaptin term. According to D.E. Walker in 1998, writing for the Smithsonian, this term is an adaptation of the term ''cú·pʼnitpeľu'' (the Nez Perce people). The term is formed from ''cú·pʼnit'' (piercing with a pointed object) and ''peľu'' (people). By contrast, the ''Nez Perce Language Dictionary'' has a different analysis than did Walker for the term ''cúpnitpelu''. The prefix ''cú''- means "in single file". This prefix, combined with the verb ''-piní'', "to come out (e.g. of forest, bushes, ice)". Finally, with the suffix of ''-pelú'', meaning "people or inhabitants of". Together, these three elements: ''cú''- + -''piní'' + ''pelú'' = ''cúpnitpelu'', or "the People Walking Single File Out of the Forest". Nez Perce oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985 ...

indicates the name "Cuupn'itpel'uu" meant "we walked out of the woods or walked out of the mountains" and referred to the time before the Nez Perce had horses.

Language

TheNez Perce language

Nez Perce, also spelled Nez Percé or called Nimipuutímt (alternatively spelled ''Nimiipuutímt'', ''Niimiipuutímt'', or ''Niimi'ipuutímt''), is a Sahaptian language related to the several dialects of Sahaptin (note the spellings ''-ian'' vs ...

, or Niimiipuutímt, is a Sahaptian

Sahaptian (also Sahaptianic, Sahaptin, Shahaptian) is a two-language branch of the Plateau Penutian family spoken by Native Americans in the United States, Native American peoples in the Columbia Plateau region of Washington (state), Washington, ...

language related to the several dialects of Sahaptin

The Sahaptin are a number of Native American tribes who speak dialects of the Sahaptin language. The Sahaptin tribes inhabited territory along the Columbia River and its tributaries in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Sahaptin-s ...

. The Sahaptian sub-family is one of the branches of the Plateau Penutian

Plateau Penutian (also Shahapwailutan, Lepitan) is a family of languages spoken in northern California, reaching through central-western Oregon to northern Washington and central-northern Idaho.

Family division

Plateau Penutian consists of four ...

family, which in turn may be related to a larger Penutian

Penutian is a proposed grouping of language families that includes many Native American languages of western North America, predominantly spoken at one time in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. The existence of a Penutian s ...

grouping.

Aboriginal territory

The Nez Perce territory at the time of Lewis and Clark (1804–1806) was approximately and covered parts of present-day

The Nez Perce territory at the time of Lewis and Clark (1804–1806) was approximately and covered parts of present-day Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

, and Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

, in an area surrounding the Snake (Weyikespe), Grande Ronde River

The Grande Ronde River ( or, less commonly, ) is a tributary of the Snake River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 3, 2011 in northeastern Oregon and southeastern ...

, Salmon (Naco’x kuus) ("Chinook salmon

The Chinook salmon (''Oncorhynchus tshawytscha'') is the largest and most valuable species of Pacific salmon in North America, as well as the largest in the genus '' Oncorhynchus''. Its common name is derived from the Chinookan peoples. Other ...

Water") and the Clearwater (Koos-Kai-Kai) ("Clear Water") rivers. The tribal area extended from the Bitterroots in the east (the door to the Northwestern Plains of Montana) to the Blue Mountains in the west between latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

s 45°N and 47°N.

In 1800, the Nez Perce had more than 70 permanent villages, ranging from 30 to 200 individuals, depending on the season and social grouping. Archeologists have identified a total of about 300 related sites including camps and villages, mostly in the Salmon River Canyon. In 1805, the Nez Perce were the largest tribe on the Columbia River Plateau

The Columbia Plateau is a geologic and geographic region that lies across parts of the U.S. states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. It is a wide flood basalt plateau between the Cascade Range and the Rocky Mountains, cut through by the Columbi ...

, with a population of about 6,000. By the beginning of the 20th century, the Nez Perce had declined to about 1,800 due to epidemics

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious d ...

, conflicts with non-Indians, and other factors. The tribe reports having more than 3,500 members in 2021.

Like other Plateau tribes

Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau, also referred to by the phrase Indigenous peoples of the Plateau, and historically called the Plateau Indians (though comprising many groups) are indigenous peoples of the Interior of British Columbia ...

, the Nez Perce had seasonal villages and camps to take advantage of natural resources throughout the year. Their migration followed a recurring pattern from permanent winter villages through several temporary camps, nearly always returning to the same locations each year. The Nez Perce traveled via the Lolo Trail (Salish: Naptnišaqs – "Nez Perce Trail") (Khoo-say-ne-ise-kit) as far east as the Plains (Khoo-sayn / Kuseyn) ("Buffalo country") of Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

to hunt buffalo (Qoq'a lx) and as far west as the Pacific Coast (’Eteyekuus) ("Big Water"). Before the 1957 construction of The Dalles Dam

The Dalles Dam is a concrete-gravity run-of-the-river dam spanning the Columbia River, two miles (3 km) east of the city of The Dalles, Oregon, United States. It joins Wasco County, Oregon with Klickitat County, Washington, 300 miles (309&nbs ...

, which flooded this area, Celilo Falls (Silayloo) was a favored location on the Columbia River (Xuyelp) ("The Great River") for salmon (lé'wliks)-fishing.

Enemies and allies

The Nez Perce had many allies and trading partners among neighboring peoples, but also enemies and ongoing antagonist tribes. To the north of them lived the Coeur d’Alene (Schitsu'umsh) (’Iskíicu’mix), Spokane (Sqeliz) (Heyéeynimuu/Heyeynimu - "Steelhead atingPeople"), and further north the Kalispel (Ql̓ispé) (Qem’éespel’uu/Q'emespelu, both meaning "Camas People" or "Camas Eaters"), Colville (Páapspaloo/Papspelu - "Fir Tree People") and Kootenay / Kootenai (Ktunaxa) (Kuuspel’úu/Kuuspelu - "Water People", lit. "River People"), to the northwest lived thePalus

Palus may refer to:

* Palus, Maharashtra, a place in India

* 24194 Paľuš, a main belt asteroid, named for Pavel Paľuš (born 1936), Slovak astronomer

* Palus tribe, or Palouse people

* ''Palus'', a grade of gladiator

See also

* Palu (dis ...

(Pelúucpuu/Peluutspu - "People of Pa-luš-sa/Palus illage) and to the west the Cayuse (Lik-si-yu) (Weyíiletpuu – "Ryegrass People"), west bound there were found the Umatilla (Imatalamłáma) (Hiyówatalampoo/Hiyuwatalampo), Walla Walla Walla Walla can refer to:

* Walla Walla people, a Native American tribe after which the county and city of Walla Walla, Washington, are named

* Place of many rocks in the Australian Aboriginal Wiradjuri language, the origin of the name of the town ...

, Wasco Wasco is the name of four places in the United States:

Places United States

* Wasco, California, a city in California

** Wasco State Prison, located in Wasco, California

* Wasco, Illinois, a former hamlet (unincorporated town) in Illinois, now pa ...

(Wecq’úupuu) and Sk'in (Tike’éspel’uu) and northwest of the latter various Yakama

The Yakama are a Native American tribe with nearly 10,851 members, based primarily in eastern Washington state.

Yakama people today are enrolled in the federally recognized tribe, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Their ...

bands (Lexéyuu), to the south lived the Snake Indians

Snake Indians is a collective name given to the Northern Paiute, Bannock (tribe), Bannock, and Shoshone Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe (Native American), tribes.

The term was used as early as 1739 by French trader an ...

(various Northern Paiute (Numu) bands (Hey’ǘuxcpel’uu) in the southwest and Bannock (Nimi Pan a'kwati)- Northern Shoshone (Newe) bands (Tiwélqe/Tewelk'a, later Sosona') in the southeast), to the east lived the Lemhi Shoshone

The Lemhi Shoshone are a tribe of Northern Shoshone, also called the Akaitikka, Agaidika, or "Eaters of Salmon".Murphy and Murphy, 306 The name "Lemhi" comes from Fort Lemhi, a Mormon mission to this group. They traditionally lived in the Lemhi Ri ...

(Lémhaay), north of them the Bitterroot Salish / Flathead (Seliš) (Séelix/Se'lix), further east and northeast on the Northern Plains were the Crow (Apsáalooke) (’Isúuxe/Isuuxh'e - "Crow People") and two powerful alliances – the Iron Confederacy (Nehiyaw-Pwat) (named after the dominating Plains and Woods Cree (Paskwāwiyiniwak and Sakāwithiniwak) and Assiniboine (Nakoda) (Wihnen’íipel’uu), an alliance of northern plains Native American nations based around the fur trade, and later included the Stoney (Nakoda), Western Saulteaux / Plains Ojibwe (Bungi or Nakawē) (Sat'sashipunu/Sat'sashipuun - "Porcupine People" or "Porcupine Eater"), and Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture which derives ...

) and the Blackfoot Confederacy (Niitsitapi or Siksikaitsitapi) (’Isq’óyxnix/Issq-oykinix - "Blackfooted People") (composed of three Blackfoot speaking peoples – the Piegan or Peigan (Piikáni), the Kainai or Bloods (Káínaa), and the Siksika or Blackfoot (Siksikáwa), later joined by the unrelated Sarcee (Tsuu T'ina) and (for a time) by Gros Ventre or Atsina (A'aninin) (H'elutiin)). The feared Blackfoot Confederacy and the various Teton Sioux (Lakota) (Iseq'uulkt - "Cut Throats") and their later allies, the Cheyenne (Suhtai/Sutaio Tsitsistas) (T'septitimeni'n - " eople withPainted arrows"), were the main enemies of the Plateau peoples when entering the Northwestern Plains to hunt buffalo.

Historic regional bands, bands, local groups, and villages

* Almotipu Band :Territories alongSnake River

The Snake River is a major river of the greater Pacific Northwest region in the United States. At long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, in turn, the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. The Snake ...

in Hells Canyon

Hells Canyon is a canyon in the Western United States, located along the border of eastern Oregon, a small section of eastern Washington and western Idaho. It is part of the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area which is also located in p ...

up to about 80 miles south of today's Lewiston, Idaho

Lewiston is a city and the county seat of Nez Perce County, Idaho, United States, in the state's north central region. It is the second-largest city in the northern Idaho region, behind Coeur d'Alene, and ninth-largest in the state. Lewiston is ...

(''Simiinekem'' – "confluence of two rivers" or "river fork", as the Clearwater flows into the Snake River here), in Wallowa Mountains

The Wallowa Mountains () are a mountain range located in the Columbia Plateau of northeastern Oregon in the United States. The range runs approximately northwest to southeast in southwestern Wallowa County and eastern Union County between the ...

and in the Seven Devils Mountains in Oregon and Idaho. Their fishing and hunting grounds were also used by the ''Pelloatpallah Band'' (comprising the "Palus (or Palus proper) Band" and "Wawawai Band" of the Upper Palus Regional Band), who formed bilingual Palus-Nez-Percé bands due to many mixed marriages.

:several village based bands are counted among them:

:*the ''Nuksiwepu Band''

:*the ''Palótpu Band'' (their village Palót was on the north bank of the Snake River – about 2 to 3 miles above Sáhatp)

:*the ''Pinewewixpu (Pinăwăwipu) Band'' (their village Pinăwăwi was located at Penawawa Creek)

:*the ''Sahatpu (Sáhatpu) Band'' (their village Sáhatp was located on the north bank of the Snake River, above Wawáwih)

:*the ''Siminekempu (Shimínĕkĕmpu) Band'' (their village Shimínĕkĕm – "confluence", was located in the area of present-day Lewiston)

:*the ''Tokalatoinu (Tukálatuinu) Band'' (along the Tucannon River

The Tucannon River is a tributary of the Snake River in the U.S. state of Washington. It flows generally northwest from headwaters in the Blue Mountains of southeastern Washington to meet the Snake upstream from Lyons Ferry Park and the mouth of ...

(''Took-kahl-la-toin''), a tributary of the Snake River)

:*the ''Wawawipu Band'' (their village Wawáwih was located at Wawawai Creek, a tributary of the Snake River)

* Alpowna (Alpowai) Band or Alpowe'ma (Alpoweyma/Alpowamino) Band ("People along Alpaha (Alpowa) Creek" or "People of ’Al’pawawaii, i.e. Clarkston")

:Territories along the South and Middle Fork of the Clearwater River downstream to the city of Lewiston (and south of it) in eastern Washington and the Idaho Panhandle. They also spent much time east of the Bitterroot Mountains and camped along the Yellowstone River, their main meeting place and one of the most important fishing grounds was the area of Kooskia, Idaho

Kooskia ( ) is a city in Idaho County, Idaho, United States. It is at the confluence of the South and Middle forks of the Clearwater River, combining to become the main river. The population was 607 at the 2010 census, down from 675 in 2000.

H ...

(''Leewikees''). Their fishing and hunting grounds were also used by the "Wawawai Band" of the Upper Palus Regional Band, who lived directly to the west and formed a bilingual Palus-Nez-Percé Band due to many intermarriages. They were the ''third largest Nez Percé regional group'' and their tribal area was one of the four centres for the large regional groups of the Nez Percé.

:several village based bands are counted among them:

:*the ''Alpowna (Alpowai) Band'' or ''Alpowe'ma (Alpoweyma/Alpowamino) Band'' (largest and most important band, along the Alpaha (Alpowa) Creek, a small tributary of the Clearwater), west of Clarkston, Washington ('Al'pawawaii = People of a "place of a plant called Ahl-pa-ha")

:*the ''Tsokolaikiinma Band'' (between Lewiston and Alpowa Creek)

:*the ''Hasotino (Hăsotōinu) Band'' (their settlement Hasutin / Hăsotōin was an important fishing ground at Asotin Creek (Héesutine – "eel river") on the Snake River in Nez Perce County, Idaho, directly opposite the present town of Asotin, Washington

Asotin is the county seat of the county of the same name, in the state of Washington, United States. The population of the city was 1,251 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Lewiston, ID-WA Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

The name ...

)

:**the ''Heswéiwewipu/Hăsweiwăwihpu local group'' (their village Hăsweiwăwih was also located opposite Asotin, along a small creek whose upper reaches were called Heswé/Hăsiwĕ)

:**the ''Anatōinnu local group'' (their village Ánatōin was located at the confluence of Mill Creek and the Snake River)

:*the ''Sapachesap Band''

:*the ''Witkispu Band'' (about 3 miles below Alpowa Creek, along the eastern bank of the Snake River)

:*the ''Sálwepu Band'' (at the Middle Fork of the Clearwater River, about 5 miles above present-day Kooskia, Idaho, Chief Looking Glass Group)

* Assuti Band ("People along Assuti Creek" in Idaho, joined Chief Joseph in the war of 1877.)

* Atskaaiwawipu Band or Asahkaiowaipu Band ("People at the confluence, People from the river mouth, i.e. Ahsahka")

:Territories from their winter village Ahsahka/Asaqa ("river mouth" or "confluence") up to the Salmon Ridge along the North Fork Clearwater River

The North Fork Clearwater River is a major tributary of the Clearwater River in the U.S. state of Idaho.

From its headwaters in the Bitterroot Mountains of eastern Idaho, it flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolu ...

up to its mouth into the Clearwater River, hunted sometimes near Peck, Idaho (''Pipyuuninma'') in the territory of the ''Painima Band''. An important fishing ground was Bruce Eddy

The English language name Bruce arrived in Scotland with the Normans, from the place name Brix, Manche in Normandy, France, meaning "the willowlands". Initially promulgated via the descendants of king Robert the Bruce (1274−1329), it has been a ...

in Clearwater County, Idaho, which was traditionally owned by the ''Atskaaiwawipu (Asahkaiowaipu)'', but was shared by neighboring bands upon invitation: the ''Tewepu Band'', the ''Ilasotino (Hasotino) Band'', the ''Nipihama (Nipĕhĕmă) Band'', the ''Alpowna (Alpowai) Band'' and the ''Matalaimo'' ("People further upstream", a collective term for bands that had their center around Kamiah).

* Hatweme (Hatwēme) Band or Hatwai (Héetwey) Band ("People along Hatweh Creek", a tributary of the Clearwater River, about four to five miles east of Lewiston)

* Hinsepu Band (lived along the Grande Ronde River

The Grande Ronde River ( or, less commonly, ) is a tributary of the Snake River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 3, 2011 in northeastern Oregon and southeastern ...

in Oregon.)

* Kămiăhpu Band or Kimmooenim Band ("People of Kămiăhp", "People of the Many Rope Litters Place, i.e. Kamiah")

:Their main village Kămiăhp was located on the south side of the Clearwater River and the confluence of Lawyer Creek near today's Kamiah, Idaho

Kamiah ( ) is a city in Lewis and Idaho counties in the U.S. state of Idaho. The largest city in Lewis County, it extends only a small distance into Idaho County, south of Lawyer Creek. The population was 1,295 at the 2010 census, up from 1,160 ...

("many rope litters") in the Kamiah Valley. They used with other bands the important fishing grounds near Bruce Eddy in Clearwater County, Idaho, which was in the territory of the ''Atskaaiwawipu (Asahkaiowaipu) Band''. Other Nez Perce bands often grouped them under the collective name Uyame or Uyămă; the closely related and neighboring ''Atskaaiwawipu (Asahkaiowaipu) Band'' referred to all bands around Kamiah as Matalaimo ("People further upstream"). Their tribal area was one of the four centers for the major regional groups of the Nez Percé.

:several village based bands are counted among them:

:*the ''Kămiăhpu (Kimmooenim) Band'' (was the biggest and most important band of the Kamiah Valley area)

:*the ''Tewepu Band'' ("People of Téewe, i.e. Orofino, Idaho

Orofino (''"fine gold"'' rein Spanish) is a city in and the county seat of Clearwater County, Idaho, along Orofino Creek and the north bank of the Clearwater River. It is the major city within the Nez Perce Indian Reservation. The population w ...

" at the confluence of Orofino Creek and Clearwater River)

:*the ''Tuke'liklikespu (Tukē'lĭklĭkespu) Band'' (near Big Eddy on the north bank of the Clearwater River, some miles upstream from Orofino)

:*the ''Pipu'inimu Band'' (at Big Canyon Creek in Camas Prairie, which flows into the Clearwater River north of today's Peck; they were therefore direct neighbours of the southern Painima Band),

:*the ''Painima Band'' (near present-day Peck, Idaho

Peck is a city in Nez Perce County, Idaho, United States. The population was 197 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Lewiston, ID- WA Metropolitan Statistical Area. Many residents of Peck work in nearby Orofino, Idaho. Additionally, Peck r ...

(''Pipyuuninma'') in Nez Perce County, on the Clearwater River in Idaho)

* Kannah Band or Kam'nakka Band ("People of Kannah (along Clearwater River)" in Idaho)

* Lamtáma (Lamátta) Band or Lamatama Band ("People of a region with little snow, i.e. Lamtáma (Lamátta) region")

:Territories were between the ''Alpowai Band'' in the north and downstream in the northwest the ''Pikunan (Pikunin) Band'' and extended in the Idaho Panhandle north along the Upper Salmon River (''Naco'x kuus'' – "Salmon River") and one of its tributaries, the White Bird Creek, and to the Snake River in the southwest, and also included the White Bird Canyon

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

(deeper than the Grand Canyon) in the southwest of the Clearwater Mountains

The Clearwater Mountains are part of the Rocky Mountains, located in the panhandle of Idaho in the Western United States. The mountains lie between the Salmon River and the Bitterroot Range and encompass an area of .

__NOTOC__ Subranges North ...

and southeast of the Camas prairie

The name camas prairie refers to several different geographical areas in the western United States which were named for the native perennial camassia or camas. The culturally and scientitifcally significant of these areas lie within Idaho and Monta ...

. Their tribal area and band name is derived from ''Lamtáma (Lamátta)'' ("area with little snow") and refers to its excellent climatic conditions, which were particularly suitable for horse breeding. They were the ''second largest Nez Percé regional group''; also called ''Salmon River Band''.

:*the ''Esnime (Iyăsnimă) Band'' (along Slate Creek ('Iyeesnime) and Upper Salmon River, therefore often simply called ''Slate Creek Band'' or ''Upper Salmon River Indians'')

:*the ''Nipihama (Nipĕhĕmă) Band'' (from Lower Salmon River to White Bird Creek)

:*the ''Tamanmu Band'' (their settlement Tamanma was located at the mouth of the Salmon River in Idaho)

* Lapwai Band or Lapwēme Band ("People of the Butterfly Place, i.e. Lapwai

Lapwai is a city in the Northwestern United States, northwest United States, in Nez Perce County, Idaho, Nez Perce County, Idaho. Its population was 1,137 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, and it is the seat of government of the Nez Pe ...

")

:Territories along Sweetwater Creek and Lapwai Creek up to its confluence with the Clearwater River near today's Spalding, Idaho

Spalding is an unincorporated community in the northwest United States, located in northern Nez Perce County, Idaho.

Description

The community is located east and upstream of Lewiston, on the Clearwater River, at the mouth of the Lapw ...

. One of their traditional settlements (as well as an important meeting place for neighbouring bands) was on the site of today's Lapwai, Idaho

Lapwai is a city in the northwest United States, in Nez Perce County, Idaho. Its population was 1,137 at the 2010 census, and it is the seat of government of the Nez Perce Indian Reservation.

Lapwai actually means "The land of the butterflies"

...

(''Thlap-Thlap'', also: ''Léepwey'' – "Place of the Butterflies"), the tribal and administrative centre of the Nez Percé Tribe of Idaho. Their tribal area was one of the four centers for the major regional groups of the Nez Percé.

* Mákapu Band ("People from Máka/Maaqa along Cottonwood Creek (formerly: Maka Creek"), a tributary of the Clearwater River, Idaho.)

* Pikunan (Pikunin) Band or Pikhininmu Band ("Snake River People")

:Territories encompassed the vast mountain wilderness between the Snake River in the south and the Lower Salmon River in the north until it met the Snake River, were direct neighbours of the ''Wallowa (Willewah) Band'' on the opposite bank of the Snake River in the west and the ''Lamtáma (Lamátta) Band'' living further southeast of them. They could be classified as buffalo hunters, but they were also true mountain dwellers, also called the ''Snake River tribe''.

* Saiksaikinpu Band (on the upper portion of the Southern Fork Clearwater; their immediate neighbors downstream was the ''Tukpame Band'')

* Saxsano Band (about 4 miles above Asotin, Washington, on the east side of Snake River.)

* Taksehepu Band ("People of ''Tukeespe/Tu-kehs-pa APS'', i.e. Ghost town

Ghost Town(s) or Ghosttown may refer to:

* Ghost town, a town that has been abandoned

Film and television

* Ghost Town (1936 film), ''Ghost Town'' (1936 film), an American Western film by Harry L. Fraser

* Ghost Town (1956 film), ''Ghost Town'' ...

Agatha")

* Tukpame Band (on the lower portion of the Southern Fork Clearwater; their immediate neighbors upstream was the ''Saiksaikinpu Band''.)

*Wallowa (Willewah) Band or Walwáma (Walwáama) Band ("People along the Wallowa River" or "People along the Grand Ronde River")

:Territories in northeastern Oregon and northwestern Idaho with tribal centre in the river valleys of the Imnaha River

The Imnaha River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 3, 2011 tributary of the Snake River in the U.S. state of Oregon. Flowing generally east near the headwaters a ...

, the Minam River

The Minam River is a tributary of the Wallowa River, long, in northeastern Oregon in the United States. It drains a rugged wilderness area of the Wallowa Mountains northeast of La Grande.

It rises in the Wallowas in the Eagle Cap Wilderness of ...

and the Wallowa River

The Wallowa River is a tributary of the Grande Ronde River, approximately long, in northeastern Oregon in the United States. It drains a valley on the Columbia Plateau in the northeast corner of the state north of Wallowa Mountains.

The Wallowa ...

(''Wal'awa'' – "the winding river"). Their territory extended into the Blue Mountains (already claimed by the Cayuse) in the west, to the Wallowa Mountains

The Wallowa Mountains () are a mountain range located in the Columbia Plateau of northeastern Oregon in the United States. The range runs approximately northwest to southeast in southwestern Wallowa County and eastern Union County between the ...

in the southwest, to both sides of the Grande Ronde River

The Grande Ronde River ( or, less commonly, ) is a tributary of the Snake River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 3, 2011 in northeastern Oregon and southeastern ...

(''Waliwa'' or ''Willewah'') and its confluence with the Snake River in the north, and almost to the Snake River in the east. Their area was widely known as an excellent grazing ground for the large herds of horses and was therefore often used by the neighbouring and related ''Weyiiletpuu (Wailetpu) Band'' ("Ryegrass People, i.e. the Cayuse people

The Cayuse are a Native American tribe in what is now the state of Oregon in the United States. The Cayuse tribe shares a reservation and government in northeastern Oregon with the Umatilla and the Walla Walla tribes as part of the Confed ...

). They were often grouped under the collective name Kămúinnu or Qéemuynu ("People of the Indian Hemp  Indian hemp may refer to any of various fiber bearing plan ...

Indian hemp may refer to any of various fiber bearing plan ...

"). They were the ''largest Nez Percé group'' and their tribal area was one of the four centers for the major regional groups of the Nez Percé. Today most part of the  Indian hemp may refer to any of various fiber bearing plan ...

Indian hemp may refer to any of various fiber bearing plan ...Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation is the federally recognized tribe that controls the Colville Indian Reservation, which is located in northeastern Washington, United States. It is the government for its people.

The Confederate Tr ...

.

:several village based bands are counted among them:

:*the ''Wallowa (Willewah) Band'' (the largest band with several local groups, in the Wallowa River Valley and Zumwalt Prairie

Zumwalt Prairie is a grassland area located in Wallowa County in northeast Oregon, United States. Measuring , much of the land is used for agriculture, with some portions protected as the Zumwalt Prairie Preserve owned by The Nature Conservancy. ...

)

:*the ''Imnáma (Imnámma) Band'' (lived with several local groups isolated in the Imnaha River Valley)

:*the ''Weliwe (Wewi'me) Band'' (their settlement Williwewix was located at the mouth of the Grande Ronde River)

:*the ''Inantoinu Band'' (in Joseph Canyon

Joseph Canyon (Nez Perce: an-an-a-soc-um, meaning "long, rough canyon") is a -deep basalt canyon in northern Wallowa County, Oregon, and southern Asotin County, Washington, United States.

Geography

Joseph Canyon contains Joseph Creek, a tributar ...

– known as ''Saqánma'' ("long, wild canyon") or ''an-an-a-soc-um'' ("long, rough canyon") – and along Lower Joseph Creek to its mouth into the Grande Ronde River)

:*the ''Toiknimapu Band'' (above Joseph Creek and along the north bank of the Grande Ronde River)

:*the ''Isäwisnemepu (Isawisnemepu) Band'' (near the present Zindel, at the Grande Ronde River in Oregon)

:*the ''Sakánma Band'' (several local groups along the Snake River between the mouth of the Salmon River in the south and the Grande Ronde River in the north, the name of their main village Sakán and the band name Sakánma refers to an area where the cliffs rise close to the water – this could be Joseph Canyon (Saqánma))

* Yakama Band or Yăkámă Band ("People of the Yăká River, i.e.Potlatch River

The Potlatch River is in the state of Idaho in the United States. About long, it is the lowermost major tributary to the Clearwater River, a tributary of the Snake River that is in turn a tributary of the Columbia River. Once surrounded by a ...

(above its mouth into the Clearwater River)", not to confused with the Yakama

The Yakama are a Native American tribe with nearly 10,851 members, based primarily in eastern Washington state.

Yakama people today are enrolled in the federally recognized tribe, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Their ...

peoples)

:Territories along the Potlatch River (which was called Yăká above its mouth into the Clearwater River) in Idaho.

:several village based bands are counted among them:

:*the ''Yakto'inu (Yaktōinu) Band'' (their village Yaktōin was located at the mouth of the Potlatch River into the Clearwater River)

:*the ''Yatóinu Band'' (lived along Pine Creek, a small right tributary of the Potlatch River)

:*the ''Iwatoinu (Iwatōinu) Band'' (their village Iwatōin was located on the north bank of the Potlatch River near today's Kendrick in Latah County)

:*the ''Tunèhepu (Tunĕhĕpu) Band'' (their village Tunĕhĕ was located at the mouth of Middle Potlatch Creek into the Potlatch River, near Juliaetta, Idaho

Juliaetta is a city in Latah County, Idaho, United States. The population was 579 at the 2010 census.

History

The area was originally called Schupferville for Rupert Schupfer, an original homesteader in the area. The town was named in 1882 by t ...

(''Yeqe''))

Because of large amount of inter-marriage between Nez Perce bands and neighboring tribes or bands to forge alliances and peace (often living in mixed bilingual villages together), the following bands were also counted to the Nez Perce (which today are viewed as being linguistically and culturally closely related, but separate ethnic groups):

; Walla Walla Band

: These were the Walla Walla people

Walla Walla (), Walawalałáma ("People of Walula region along Walla Walla River"), sometimes Walúulapam, are a Sahaptin indigenous people of the Northwest Plateau. The duplication in their name expresses the diminutive form. The name ''Walla ...

which lived along the Walla Walla River and along the confluence of the Snake and Columbia River rivers, today they are enrolled in the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation are the federally recognized confederations of three Sahaptin-speaking Native American tribes who traditionally inhabited the Columbia River Plateau region: the Cayuse, Umatilla, and ...

.

; Pelloatpallah Band Palous Band

: These were the ''Palus (or Palus proper) Band'' and ''Wawawai Band'' of the Upper Palus Band, which constituted together with the Middle Palus Band und Lower Palus Band – one of the three main groups of the Palus people

The Palouse are a Sahaptin tribe recognized in the Treaty of 1855 with the United States along with the Yakama. It was negotiated at the 1855 Walla Walla Council. A variant spelling is Palus. Today they are enrolled in the federally recognized ...

, which lived along the Columbia, Snake and Palouse Rivers to the northwest of the Nez Perce. Today the majority is enrolled in the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation #REDIRECT Yakama Indian Reservation

The Yakama Indian Reservation (spelled Yakima until 1994) is a Native American reservation in Washington state of the federally recognized tribe known as the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. ...

and some are part of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation is the federally recognized tribe that controls the Colville Indian Reservation, which is located in northeastern Washington, United States. It is the government for its people.

The Confederate Tr ...

.

; Weyiiletpuu (Wailetpu) Band Yeletpo Band

: These were the Cayuse people

The Cayuse are a Native American tribe in what is now the state of Oregon in the United States. The Cayuse tribe shares a reservation and government in northeastern Oregon with the Umatilla and the Walla Walla tribes as part of the Confed ...

which lived to the west of the Nez Perce at the headwaters of the Walla Walla, Umatilla and Grande Ronde River and from the Blue Mountains westwards up to the Deschutes River, they oft shared village sites with the Nez Perce and Palus and were feared by neighboring tribes, as early as 1805, most Cayuse had given up their mother tongue and had switched to ''Weyíiletpuu'', a variety of the Lower Nez Perce/Lower Niimiipuutímt dialect of the Nez Perce language

Nez Perce, also spelled Nez Percé or called Nimipuutímt (alternatively spelled ''Nimiipuutímt'', ''Niimiipuutímt'', or ''Niimi'ipuutímt''), is a Sahaptian language related to the several dialects of Sahaptin (note the spellings ''-ian'' vs ...

. They called themselves by their Nez-Percé name as ''Weyiiletpuu'' ("Ryegrass People"); today most Cayuse are enrolled into the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation are the federally recognized confederations of three Sahaptin-speaking Native American tribes who traditionally inhabited the Columbia River Plateau region: the Cayuse, Umatilla, and ...

, some as Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs

The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs is a recognized Native American tribe made of three tribes who put together a confederation. They live on and govern the Warm Springs Indian Reservation in the U.S. state of Oregon.

Tribes

The confederat ...

or Nez Perce Tribe of Idaho

The Nez Percé (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, K ...

.

Culture

The semi-sedentary Nez Percés were

The semi-sedentary Nez Percés were Hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

without agriculture living in a society in which most or all food is obtained by foraging

Foraging is searching for wild food resources. It affects an animal's Fitness (biology), fitness because it plays an important role in an animal's ability to survive and reproduce. Optimal foraging theory, Foraging theory is a branch of behaviora ...

(collecting wild plants and roots and pursuing wild animals). They depended on hunting, fishing, and the gathering of wild roots and berries.

Nez Perce people historically depended on various Pacific salmon and Pacific trout for their food: Chinook salmon

The Chinook salmon (''Oncorhynchus tshawytscha'') is the largest and most valuable species of Pacific salmon in North America, as well as the largest in the genus '' Oncorhynchus''. Its common name is derived from the Chinookan peoples. Other ...

or "''nacoox''" (Oncorhynchus tschawytscha

The Chinook salmon (''Oncorhynchus tshawytscha'') is the largest and most valuable species of Pacific salmon in North America, as well as the largest in the genus '' Oncorhynchus''. Its common name is derived from the Chinookan peoples. Other v ...

) were eaten the most, but other species such as Pacific lamprey

The Pacific lamprey (''Entosphenus tridentatus'') is an anadromous parasitic lamprey from the Pacific Coast of North America and Asia. It is a member of the Petromyzontidae family. The Pacific lamprey is also known as the three-tooth lamprey and ...

(Entosphenus tridentatus or Lampetra tridentata), and chiselmouth

The chiselmouth (''Acrocheilus alutaceus'') is an unusual cyprinid fish of western North America. It is named for the sharp hard plate on its lower jaw, which is used to scrape rocks for algae. It is the sole member of the monotypic genus ''Acroch ...

were eaten too. Other important fishes included the Sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka

The sockeye salmon (''Oncorhynchus nerka''), also called red salmon, kokanee salmon, blueback salmon, or simply sockeye, is an anadromous species of salmon found in the Northern Pacific Ocean and rivers discharging into it. This species is a P ...

), Silver salmon

The coho salmon (''Oncorhynchus kisutch;'' Karuk: achvuun) is a species of anadromous fish in the salmon family and one of the five Pacific salmon species. Coho salmon are also known as silver salmon or "silvers". The scientific species name i ...

or ''ka'llay'' (Oncorhynchus kisutch

The coho salmon (''Oncorhynchus kisutch;'' Karuk: achvuun) is a species of anadromous fish in the salmon family and one of the five Pacific salmon species. Coho salmon are also known as silver salmon or "silvers". The scientific species name is ...

), Chum salmon or dog salmon or ''ka'llay'' (Oncorhynchus keta

The chum salmon (''Oncorhynchus keta''), also known as dog salmon or keta salmon, is a species of anadromous salmonid fish from the genus '' Oncorhynchus'' (Pacific salmon) native to the coastal rivers of the North Pacific and the Beringian A ...

), Mountain whitefish

The mountain whitefish (''Prosopium williamsoni'') is one of the most widely distributed salmonid fish of western North America. It is found from the Mackenzie River drainage in Northwest Territories, Canada south through western Canada and ...

or "''ci'mey''" (Prosopium williamsoni

The mountain whitefish (''Prosopium williamsoni'') is one of the most widely distributed salmonid fish of western North America. It is found from the Mackenzie River drainage in Northwest Territories, Canada south through western Canada and t ...

), White sturgeon

White sturgeon (''Acipenser transmontanus'') is a species of sturgeon in the family Acipenseridae of the order Acipenseriformes. They are an anadromous fish species ranging in the Eastern Pacific; from the Gulf of Alaska to Monterey, Californ ...

( Acipenser transmontanus), White sucker

The white sucker (''Catostomus commersonii)'' is a species of freshwater cypriniform fish inhabiting the upper Midwest and Northeast in North America, but it is also found as far south as Georgia and as far west as New Mexico. The fish is common ...

or "''mu'quc''" (Catostomus commersonii

The white sucker (''Catostomus commersonii)'' is a species of freshwater cypriniform fish inhabiting the upper Midwest and Northeast in North America, but it is also found as far south as Georgia and as far west as New Mexico. The fish is commo ...

), and varieties of trout – West Coast steelhead or "''heyey''" (Oncorhynchus mykiss

The rainbow trout (''Oncorhynchus mykiss'') is a species of trout native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific Ocean in Asia and North America. The steelhead (sometimes called "steelhead trout") is an anadromous (sea-run) form of the coastal ...

), brook trout

The brook trout (''Salvelinus fontinalis'') is a species of freshwater fish in the char genus ''Salvelinus'' of the salmon family Salmonidae. It is native to Eastern North America in the United States and Canada, but has been introduced elsewhere ...

or "''pi'ckatyo''" (Salvelinus fontinalis

The brook trout (''Salvelinus fontinalis'') is a species of freshwater fish in the char genus ''Salvelinus'' of the salmon family Salmonidae. It is native to Eastern North America in the United States and Canada, but has been introduced elsewhere ...

), bull trout

The bull trout (''Salvelinus confluentus'') is a char of the family Salmonidae native to northwestern North America. Historically, ''S. confluentus'' has been known as the " Dolly Varden" (''S. malma''), but was reclassified as a separate specie ...

or "''i'slam''" (Salvelinus confluentus

The bull trout (''Salvelinus confluentus'') is a char of the family Salmonidae native to northwestern North America. Historically, ''S. confluentus'' has been known as the " Dolly Varden" (''S. malma''), but was reclassified as a separate spec ...

), and Cutthroat trout

The cutthroat trout is a fish species of the family Salmonidae native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific Ocean, Rocky Mountains, and Great Basin in North America. As a member of the genus '' Oncorhynchus'', it is one of the Pacific tro ...

or "''wawa'lam''" (Oncorhynchus clarkii

The cutthroat trout is a fish species of the family Salmonidae native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific Ocean, Rocky Mountains, and Great Basin in North America. As a member of the genus ''Oncorhynchus'', it is one of the Pacific trou ...

).

Prior to contact with Europeans, the Nez Perce's traditional hunting and fishing areas spanned from the Cascade Range

The Cascade Range or Cascades is a major mountain range of western North America, extending from southern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California. It includes both non-volcanic mountains, such as the North Cascades, ...

in the west to the Bitterroot Mountains

The Northern and Central Bitterroot Range, collectively the Bitterroot Mountains (Salish: čkʷlkʷqin), is the largest portion of the Bitterroot Range, part of the Rocky Mountains and Idaho Batholith, located in the panhandle of Idaho and west ...

in the east.

Historically, in late May and early June, Nez Perce villagers crowded to communal fishing sites to trap eels, steelhead, and chinook salmon, or haul in fish with large dip nets. Fishing took place throughout the summer and fall, first on the lower streams and then on the higher tributaries, and catches also included salmon, sturgeon, whitefish, suckers, and varieties of trout. Most of the supplies for winter use came from a second run in the fall, when large numbers of Sockeye salmon, silver, and dog salmon appeared in the rivers.

Fishing is traditionally an important ceremonial and commercial activity for the Nez Perce tribe. Today Nez Perce fishers participate in tribal fisheries in the mainstream Columbia River between Bonneville and McNary dams. The Nez Perce also fish for spring and summer Chinook salmon and Rainbow trout/steelhead in the Snake River

The Snake River is a major river of the greater Pacific Northwest region in the United States. At long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, in turn, the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. The Snake ...

and its tributaries. The Nez Perce tribe runs the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery on the Clearwater River, as well as several satellite hatchery programs.

The first fishing of the season was accompanied by prescribed rituals and a ceremonial feast known as "''kooyit''". Thanksgiving was offered to the Creator and to the fish for having returned and given themselves to the people as food. In this way, it was hoped that the fish would return the next year.

Like salmon, plants contributed to traditional Nez Perce culture in both material and spiritual dimensions.

Aside from fish and game, Plant foods provided over half of the dietary calories, with winter survival depending largely on dried roots, especially Kouse, or "''qáamsit''" (when fresh) and "''qáaws''" (when peeled and dried) (

The first fishing of the season was accompanied by prescribed rituals and a ceremonial feast known as "''kooyit''". Thanksgiving was offered to the Creator and to the fish for having returned and given themselves to the people as food. In this way, it was hoped that the fish would return the next year.

Like salmon, plants contributed to traditional Nez Perce culture in both material and spiritual dimensions.

Aside from fish and game, Plant foods provided over half of the dietary calories, with winter survival depending largely on dried roots, especially Kouse, or "''qáamsit''" (when fresh) and "''qáaws''" (when peeled and dried) (Lomatium

''Lomatium'' is a genus in the family Apiaceae. It consists of about 100 species native to western Northern America and northern Mexico. Its common names include biscuitroot, Indian parsley, and desert parsley. It is in the family Apiaceae and t ...

especially Lomatium cous

''Lomatium cous'' (cous biscuitroot) is a perennial herb of the family Apiaceae. The root is prized as a food by the tribes of the southern plateau of the Pacific Northwest. Meriwether Lewis collected a specimen in 1806 while on his expedition.Sc ...

), and Camas, or "'' qém'es''" (Nez Perce: "sweet") (Camassia quamash

''Camassia quamash'', commonly known as camas, small camas, common camas, common camash or quamash, is a perennial herb. It is native to western North America in large areas of southern Canada and the northwestern United States.

Description

...

), the first being roasted in pits, while the other was ground in mortars and molded into cakes for future use, both plants had been traditionally an important food and trade item. Women were primarily responsible for the gathering and preparing of these root crops. Camas bulbs were gathered in the region between the Salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family (biology), family Salmonidae, which are native to tributary, tributaries of the ...

and Clearwater river drainages. Techniques for preparing and storing winter foods enabled people to survive times of colder winters with little or no fresh foods.

Favorite fruits dried for winter were serviceberries or "''kel''" (Amelanchier alnifolia

''Amelanchier alnifolia'', the Saskatoon berry, Pacific serviceberry, western serviceberry, western shadbush, or western juneberry, is a shrub with an edible berry-like fruit, native to North America.

Description

It is a deciduous shrub or sma ...

or Saskatoon berry

''Amelanchier alnifolia'', the Saskatoon berry, Pacific serviceberry, western serviceberry, western shadbush, or western juneberry, is a shrub with an edible berry-like fruit, native to North America.

Description

It is a deciduous shrub or s ...

), black huckleberries or "''cemi'tk''" (Vaccinium membranaceum

''Vaccinium membranaceum'' is a species within the group of Vaccinium commonly referred to as huckleberry. This particular species is known by the common names thinleaf huckleberry, tall huckleberry, big huckleberry, mountain huckleberry, square ...

), red elderberries or "''mi'ttip''" ( Sambucus racemosa var. melanocarpa), and chokecherries

''Prunus virginiana'', commonly called bitter-berry, chokecherry, Virginia bird cherry, and western chokecherry (also black chokecherry for ''P. virginiana'' var. ''demissa''), is a species of bird cherry (''Prunus'' subgenus ''Padus'') nat ...

or "''ti'ms''" ( Prunus virginiana var. melanocarpa). Nez Perce textiles were made primarily from dogbane

Dogbane, dog-bane, dog's bane, and other variations, some of them regional and some transient, are names for certain plants that are reputed to kill or repel dogs; "bane" originally meant "slayer", and was later applied to plants to indicate tha ...

or "''qeemu''" (Apocynum cannabinum

''Apocynum cannabinum'' (dogbane, amy root, hemp dogbane, prairie dogbane, Indian hemp, rheumatism root, or wild cotton) is a perennial herbaceous plant that grows throughout much of North America—in the southern half of Canada and throughou ...

or Indian hemp  Indian hemp may refer to any of various fiber bearing plan ...

Indian hemp may refer to any of various fiber bearing plan ...

),  Indian hemp may refer to any of various fiber bearing plan ...

Indian hemp may refer to any of various fiber bearing plan ...tule

''Schoenoplectus acutus'' ( syn. ''Scirpus acutus, Schoenoplectus lacustris, Scirpus lacustris'' subsp. ''acutus''), called tule , common tule, hardstem tule, tule rush, hardstem bulrush, or viscid bulrush, is a giant species of sedge in the pl ...

s or "''to'ko''" ( Schoenoplectus acutus var. acutus), and western redcedar

''Thuja plicata'' is an evergreen coniferous tree in the cypress family Cupressaceae, native to western North America. Its common name is western redcedar (western red cedar in the UK), and it is also called Pacific redcedar, giant arborvitae, w ...

or "''tala'tat''" (Thuja plicata

''Thuja plicata'' is an evergreen coniferous tree in the cypress family Cupressaceae, native to western North America. Its common name is western redcedar (western red cedar in the UK), and it is also called Pacific redcedar, giant arborvitae, w ...

). The most important industrial woods were redcedar, ponderosa pine

''Pinus ponderosa'', commonly known as the ponderosa pine, bull pine, blackjack pine, western yellow-pine, or filipinus pine is a very large pine tree species of variable habitat native to mountainous regions of western North America. It is the ...

or "''la'qa''" (Pinus ponderosa

''Pinus ponderosa'', commonly known as the ponderosa pine, bull pine, blackjack pine, western yellow-pine, or filipinus pine is a very large pine tree species of variable habitat native to mountainous regions of western North America. It is the ...

), Douglas fir

The Douglas fir (''Pseudotsuga menziesii'') is an evergreen conifer species in the pine family, Pinaceae. It is native to western North America and is also known as Douglas-fir, Douglas spruce, Oregon pine, and Columbian pine. There are three va ...

or "''pa'ps''" (Pseudotsuga menziesii

The Douglas fir (''Pseudotsuga menziesii'') is an evergreen conifer species in the pine family, Pinaceae. It is native to western North America and is also known as Douglas-fir, Douglas spruce, Oregon pine, and Columbian pine. There are three va ...

), sandbar willow or "''tax's''" (Salix exigua

''Salix exigua'' (sandbar willow, narrowleaf willow, or coyote willow; syn. ''S. argophylla, S. hindsiana, S. interior, S. linearifolia, S. luteosericea, S. malacophylla, S. nevadensis,'' and '' S. parishiana'') is a species of willow native to m ...

), and hard woods such as Pacific yew or "''ta'mqay''" (Taxus brevifolia

''Taxus brevifolia'', the Pacific yew or western yew, is a species of tree in the yew family Taxaceae native to the Pacific Northwest of North America. It is a small evergreen conifer, thriving in moisture and otherwise tending to take the form o ...

) and syringa or "''sise'qiy''" (Philadelphus lewisii

''Philadelphus lewisii,'' the Lewis' mock-orange, mock-orange, Gordon's mockorange, wild mockorange, Indian arrowwood, or syringa, is a deciduous shrub native to western North America, and is the List of U.S. state and territory flowers, state fl ...

or Indian arrowwood

''Cornus florida'', the flowering dogwood, is a species of flowering plant, flowering tree in the family (biology), family Cornaceae native to eastern North America and northern Mexico. An endemic population once spanned from southernmost coasta ...

).

Many fishes and plants important to Nez Perce culture are today state symbols: the black huckleberry or "''cemi'tk''" is the official state fruit and the Indian arrowwood or "''sise'qiy''", the Douglas fir or "''pa'ps''" is the state tree of Oregon and the ponderosa pine or "''la'qa''" of Montana, the Chinook salmon is the state fish

This is a list of official and unofficial U.S. state fishes:

__TOC__

Table

See also

* Lists of U.S. state insignia

* Lists of U.S. state animals

Notes

References

Netstate.com state fish tables

External links

{{state insignia

.State ...

of Oregon, the cutthroat trout or "''wawa'lam''" of Idaho, Montana and Wyoming, and the West Coast steelhead or "heyey" of Washington.

The Nez Perce believed in spirits called ''

The Nez Perce believed in spirits called ''weyekin

Weyekin or wyakin is a Nez Perce word for a type of spiritual being.

According to Lucullus Virgil McWhorter, everything in the world - animals, trees, rocks, etc. - possesses a consciousness. These spirits are thought to offer a link to the invi ...

s'' (Wie-a-kins) which would, they thought, offer a link to the invisible world of spiritual power". The weyekin would protect one from harm and become a personal guardian spirit. To receive a weyekin, a seeker would go to the mountains alone on a vision quest. This included fasting and meditation over several days. While on the quest, the individual may receive a vision of a spirit, which would take the form of a mammal or bird. This vision could appear physically or in a dream or trance. The weyekin was to bestow the animal's powers on its bearer—for example; a deer might give its bearer swiftness. A person's weyekin was very personal. It was rarely shared with anyone and was contemplated in private. The weyekin stayed with the person until death.

Helen Hunt Jackson

Helen Hunt Jackson (pen name, H.H.; born Helen Maria Fiske; October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885) was an American poet and writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native Americans by t ...

, author of "A Century of Dishonor

''A Century of Dishonor'' is a non-fiction book by Helen Hunt Jackson first published in 1881 that chronicled the experiences of Native Americans in the United States, focusing on injustices.

Jackson wrote ''A Century of Dishonor'' in an attempt t ...

", written in 1889 refers to the Nez Perce as "the richest, noblest, and most gentle" of Indian peoples as well as the most industrious.

The museum at the Nez Perce National Historical Park

The Nez Perce National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park comprising 38 sites located across the states of Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington, which include traditional aboriginal lands of the Nez Perce people. The sit ...

, headquartered in Spalding, Idaho

Spalding is an unincorporated community in the northwest United States, located in northern Nez Perce County, Idaho.

Description

The community is located east and upstream of Lewiston, on the Clearwater River, at the mouth of the Lapw ...

, and managed by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

includes a research center, archives, and library. Historical records are available for on-site study and interpretation of Nez Perce history and culture. The park includes 38 sites associated with the Nez Perce in the states of Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington, many of which are managed by local and state agencies.

History

European contact

In 1805William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

was the first known Euro-American to meet any of the tribe, excluding the aforementioned French Canadian traders. While he, Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 – October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with ...

and their men were crossing the Bitterroot Mountains

The Northern and Central Bitterroot Range, collectively the Bitterroot Mountains (Salish: čkʷlkʷqin), is the largest portion of the Bitterroot Range, part of the Rocky Mountains and Idaho Batholith, located in the panhandle of Idaho and west ...

, they ran low of food, and Clark took six hunters and hurried ahead to hunt. On September 20, 1805, near the western end of the Lolo Trail

Lolo can refer to:

Places United States

* Lolo, Montana, a census-designated place

* Lolo Butte, a summit in Oregon

* Lolo Pass (Idaho–Montana)

* Lolo Pass (Oregon)

* Lolo National Forest, Montana

* Lolo Peak, Montana

Elsewhere

* Lolo, Cam ...

, he found a small camp at the edge of the camas-digging ground, which is now called Weippe Prairie

Weippe Prairie is a "beautiful upland prairie field of about nine by twenty miles of open farmland bordered by pine forests" at 3,000 feet elevation in Clearwater County, Idaho, at Weippe, Idaho. Camas flowers grow well there, and attracted ...

. The explorers were favorably impressed by the Nez Perce whom they met. Preparing to make the remainder of their journey to the Pacific by boats on rivers, they entrusted the keeping of their horses until they returned to "2 brothers and one son of one of the Chiefs." One of these Indians was ''Walammottinin'' (meaning "Hair Bunched and tied," but more commonly known as Twisted Hair). He was the father of Chief Lawyer

Hallalhotsoot, also Hal-hal-tlos-tsot or "Lawyer" (c. 1797–1876) was a leader of the Niimíipu (Nez Perce) and among its most famous, after Chief Joseph. He was the son of Twisted Hair, who welcomed and befriended the exhausted Lewis and ...

, who by 1877 was a prominent member of the "Treaty" faction of the tribe. The Nez Perce were generally faithful to the trust; the party recovered their horses without serious difficulty when they returned.