Newton's theorem of revolving orbits on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

The motion of astronomical bodies has been studied systematically for thousands of years. The stars were observed to rotate uniformly, always maintaining the same relative positions to one another. However, other bodies were observed to ''wander'' against the background of the fixed stars; most such bodies were called

The motion of astronomical bodies has been studied systematically for thousands of years. The stars were observed to rotate uniformly, always maintaining the same relative positions to one another. However, other bodies were observed to ''wander'' against the background of the fixed stars; most such bodies were called

Copernicus’s epicycles from Newton’s gravitational force law via linear perturbation theory in geometric algebra

. Roughly 350 years later,

and Delaunay.

However, Newton's theorem is more general than merely explaining apsidal precession. It describes the effects of adding an inverse-cube force to any central force ''F''(''r''), not only to inverse-square forces such as

The simplest illustration of Newton's theorem occurs when there is no initial force, i.e., ''F''1(''r'') = 0. In this case, the first particle is stationary or travels in a straight line. If it travels in a straight line that does not pass through the origin (yellow line in Figure 6) the equation for such a line may be written in the polar coordinates (''r'', ''θ''1) as

:

where ''θ''0 is the angle at which the distance is minimized (Figure 6). The distance ''r'' begins at infinity (when ''θ''1 – ), and decreases gradually until ''θ''1 – , when the distance reaches a minimum, then gradually increases again to infinity at ''θ''1 – . The minimum distance ''b'' is the

The simplest illustration of Newton's theorem occurs when there is no initial force, i.e., ''F''1(''r'') = 0. In this case, the first particle is stationary or travels in a straight line. If it travels in a straight line that does not pass through the origin (yellow line in Figure 6) the equation for such a line may be written in the polar coordinates (''r'', ''θ''1) as

:

where ''θ''0 is the angle at which the distance is minimized (Figure 6). The distance ''r'' begins at infinity (when ''θ''1 – ), and decreases gradually until ''θ''1 – , when the distance reaches a minimum, then gradually increases again to infinity at ''θ''1 – . The minimum distance ''b'' is the  An inverse-cube central force ''F''2(''r'') has the form

:

where the numerator μ may be positive (repulsive) or negative (attractive). If such an inverse-cube force is introduced, Newton's theorem says that the corresponding solutions have a shape called

An inverse-cube central force ''F''2(''r'') has the form

:

where the numerator μ may be positive (repulsive) or negative (attractive). If such an inverse-cube force is introduced, Newton's theorem says that the corresponding solutions have a shape called  One of the other solution types is given in terms of the

One of the other solution types is given in terms of the

Two types of

Two types of  Harmonic and subharmonic orbits are special types of such closed orbits. A closed trajectory is called a ''harmonic orbit'' if ''k'' is an integer, i.e., if in the formula . For example, if (green planet in Figures 1 and 4, green orbit in Figure 9), the resulting orbit is the third harmonic of the original orbit. Conversely, the closed trajectory is called a ''subharmonic orbit'' if ''k'' is the inverse of an integer, i.e., if in the formula . For example, if (green planet in Figure 5, green orbit in Figure 10), the resulting orbit is called the third subharmonic of the original orbit. Although such orbits are unlikely to occur in nature, they are helpful for illustrating Newton's theorem.

Harmonic and subharmonic orbits are special types of such closed orbits. A closed trajectory is called a ''harmonic orbit'' if ''k'' is an integer, i.e., if in the formula . For example, if (green planet in Figures 1 and 4, green orbit in Figure 9), the resulting orbit is the third harmonic of the original orbit. Conversely, the closed trajectory is called a ''subharmonic orbit'' if ''k'' is the inverse of an integer, i.e., if in the formula . For example, if (green planet in Figure 5, green orbit in Figure 10), the resulting orbit is called the third subharmonic of the original orbit. Although such orbits are unlikely to occur in nature, they are helpful for illustrating Newton's theorem.

The motion of the

The motion of the

Ironically, Hall's theory was ruled out by careful astronomical observations of the Moon. The currently accepted explanation for this precession involves the theory of

:''It is required to make a body move in a curve that revolves about the center of force in the same manner as another body in the same curve at rest.''Chandrasekhar, p. 184.

Newton's derivation of Proposition 43 depends on his Proposition 2, derived earlier in the ''Principia''.Chandrasekhar, pp. 67–70. Proposition 2 provides a geometrical test for whether the net force acting on a point mass (a particle) is a

:''It is required to make a body move in a curve that revolves about the center of force in the same manner as another body in the same curve at rest.''Chandrasekhar, p. 184.

Newton's derivation of Proposition 43 depends on his Proposition 2, derived earlier in the ''Principia''.Chandrasekhar, pp. 67–70. Proposition 2 provides a geometrical test for whether the net force acting on a point mass (a particle) is a

Three-body problem

discussed by Alain Chenciner at

classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a physical theory describing the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, and astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. For objects governed by classical ...

, Newton's theorem of revolving orbits identifies the type of central force

In classical mechanics, a central force on an object is a force that is directed towards or away from a point called center of force.

: \vec = \mathbf(\mathbf) = \left\vert F( \mathbf ) \right\vert \hat

where \vec F is the force, F is a vecto ...

needed to multiply the angular speed

Angular may refer to:

Anatomy

* Angular artery, the terminal part of the facial artery

* Angular bone, a large bone in the lower jaw of amphibians and reptiles

* Angular incisure, a small anatomical notch on the stomach

* Angular gyrus, a regio ...

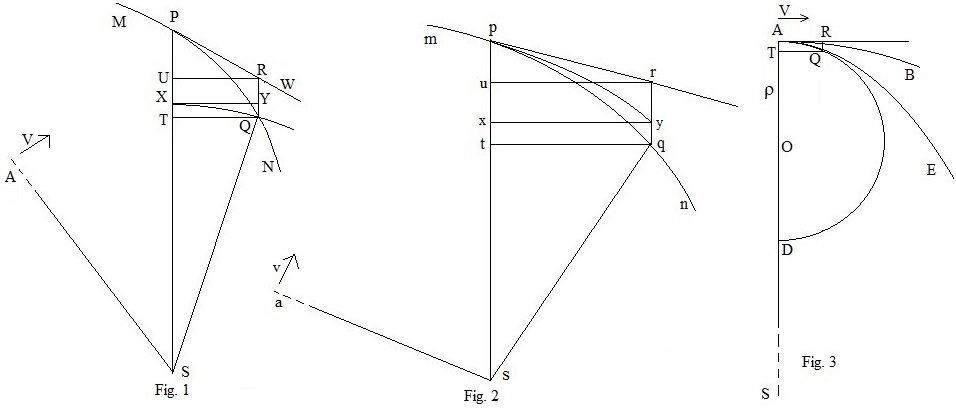

of a particle by a factor ''k'' without affecting its radial motion (Figures 1 and 2). Newton applied his theorem to understanding the overall rotation of orbits (''apsidal precession

In celestial mechanics, apsidal precession (or apsidal advance) is the precession (gradual rotation) of the line connecting the apsides (line of apsides) of an astronomical body's orbit. The apsides are the orbital points closest (periapsi ...

'', Figure 3) that is observed for the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

and planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

s. The term "radial motion" signifies the motion towards or away from the center of force, whereas the angular motion is perpendicular to the radial motion.

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

derived this theorem in Propositions 43–45 of Book I of his ''Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica

(English: ''Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy'') often referred to as simply the (), is a book by Isaac Newton that expounds Newton's laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation. The ''Principia'' is written in Latin and ...

'', first published in 1687. In Proposition 43, he showed that the added force must be a central force, one whose magnitude depends only upon the distance ''r'' between the particle and a point fixed in space (the center). In Proposition 44, he derived a formula for the force, showing that it was an inverse-cube force, one that varies as the inverse cube of ''r''. In Proposition 45 Newton extended his theorem to arbitrary central forces by assuming that the particle moved in nearly circular orbit.

As noted by astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar in his 1995 commentary on Newton's ''Principia'', this theorem remained largely unknown and undeveloped for over three centuries.Chandrasekhar, p. 183. Since 1997, the theorem has been studied by Donald Lynden-Bell

Donald Lynden-Bell CBE FRS (5 April 1935 – 6 February 2018) was a British theoretical astrophysicist. He was the first to determine that galaxies contain supermassive black holes at their centres, and that such black holes power quasars. ...

and collaborators. Its first exact extension came in 2000 with the work of Mahomed and Vawda.

Historical context

planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

s after the Greek word "πλανήτοι" (''planētoi'') for "wanderers". Although they generally move in the same direction along a path across the sky (the ecliptic

The ecliptic or ecliptic plane is the orbital plane of the Earth around the Sun. From the perspective of an observer on Earth, the Sun's movement around the celestial sphere over the course of a year traces out a path along the ecliptic again ...

), individual planets sometimes reverse their direction briefly, exhibiting retrograde motion

Retrograde motion in astronomy is, in general, orbital or rotational motion of an object in the direction opposite the rotation of its primary, that is, the central object (right figure). It may also describe other motions such as precession or ...

.

To describe this forward-and-backward motion, Apollonius of Perga

Apollonius of Perga ( grc-gre, Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Περγαῖος, Apollṓnios ho Pergaîos; la, Apollonius Pergaeus; ) was an Ancient Greek geometer and astronomer known for his work on conic sections. Beginning from the contribution ...

() developed the concept of deferents and epicycles, according to which the planets are carried on rotating circles that are themselves carried on other rotating circles, and so on. Any orbit can be described with a sufficient number of judiciously chosen epicycles, since this approach corresponds to a modern Fourier transform

A Fourier transform (FT) is a mathematical transform that decomposes functions into frequency components, which are represented by the output of the transform as a function of frequency. Most commonly functions of time or space are transformed, ...

.Sugon QM, Bragais S, McNamara DJ (2008Copernicus’s epicycles from Newton’s gravitational force law via linear perturbation theory in geometric algebra

. Roughly 350 years later,

Claudius Ptolemaeus

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

published his ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canoni ...

'', in which he developed this system to match the best astronomical observations of his era. To explain the epicycles, Ptolemy adopted the geocentric

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

cosmology of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, according to which planets were confined to concentric rotating spheres. This model of the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acc ...

was authoritative for nearly 1500 years.

The modern understanding of planetary motion arose from the combined efforts of astronomer Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was k ...

and physicist Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

in the 16th century. Tycho is credited with extremely accurate measurements of planetary motions, from which Kepler was able to derive his laws of planetary motion. According to these laws, planets move on ellipse

In mathematics, an ellipse is a plane curve surrounding two focus (geometry), focal points, such that for all points on the curve, the sum of the two distances to the focal points is a constant. It generalizes a circle, which is the special ty ...

s (not epicycles) about the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

(not the Earth). Kepler's second and third laws make specific quantitative predictions: planets sweep out equal areas in equal time, and the square of their orbital period

The orbital period (also revolution period) is the amount of time a given astronomical object takes to complete one orbit around another object. In astronomy, it usually applies to planets or asteroids orbiting the Sun, moons orbiting planets ...

s equals a fixed constant times the cube of their semi-major axis

In geometry, the major axis of an ellipse is its longest diameter: a line segment that runs through the center and both foci, with ends at the two most widely separated points of the perimeter. The semi-major axis (major semiaxis) is the long ...

. Subsequent observations of the planetary orbits showed that the long axis of the ellipse (the so-called ''line of apsides'') rotates gradually with time; this rotation is known as ''apsidal precession''. The apses

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

of an orbit are the points at which the orbiting body is closest or furthest away from the attracting center; for planets orbiting the Sun, the apses correspond to the perihelion (closest) and aphelion (furthest).

With the publication of his '' Principia'' roughly eighty years later (1687), Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

provided a physical theory that accounted for all three of Kepler's laws, a theory based on Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in moti ...

and his law of universal gravitation. In particular, Newton proposed that the gravitational force between any two bodies was a central force

In classical mechanics, a central force on an object is a force that is directed towards or away from a point called center of force.

: \vec = \mathbf(\mathbf) = \left\vert F( \mathbf ) \right\vert \hat

where \vec F is the force, F is a vecto ...

''F''(''r'') that varied as the inverse square

In science, an inverse-square law is any scientific law stating that a specified physical quantity is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the source of that physical quantity. The fundamental cause for this can be understo ...

of the distance ''r'' between them. Arguing from his laws of motion, Newton showed that the orbit of any particle acted upon by one such force is always a conic section

In mathematics, a conic section, quadratic curve or conic is a curve obtained as the intersection of the surface of a cone with a plane. The three types of conic section are the hyperbola, the parabola, and the ellipse; the circle is a specia ...

, specifically an ellipse if it does not go to infinity. However, this conclusion holds only when two bodies are present (the two-body problem

In classical mechanics, the two-body problem is to predict the motion of two massive objects which are abstractly viewed as point particles. The problem assumes that the two objects interact only with one another; the only force affecting each ...

); the motion of three bodies or more acting under their mutual gravitation (the ''n''-body problem) remained unsolved for centuries after Newton, although solutions to a few special cases were discovered. Newton proposed that the orbits of planets about the Sun are largely elliptical because the Sun's gravitation is dominant; to first approximation, the presence of the other planets can be ignored. By analogy, the elliptical orbit of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

about the Earth was dominated by the Earth's gravity; to first approximation, the Sun's gravity and those of other bodies of the Solar System can be neglected. However, Newton stated that the gradual apsidal precession of the planetary and lunar orbits was due to the effects of these neglected interactions; in particular, he stated that the precession of the Moon's orbit was due to the perturbing effects of gravitational interactions with the Sun.

Newton's theorem of revolving orbits was his first attempt to understand apsidal precession quantitatively. According to this theorem, the addition of a particular type of central force—the inverse-cube force—can produce a rotating orbit; the angular speed is multiplied by a factor ''k'', whereas the radial motion is left unchanged. However, this theorem is restricted to a specific type of force that may not be relevant; several perturbing inverse-square interactions (such as those of other planets) seem unlikely to sum exactly to an inverse-cube force. To make his theorem applicable to other types of forces, Newton found the best approximation of an arbitrary central force ''F''(''r'') to an inverse-cube potential in the limit of nearly circular orbits, that is, elliptical orbits of low eccentricity, as is indeed true for most orbits in the Solar System. To find this approximation, Newton developed an infinite series that can be viewed as the forerunner of the Taylor expansion

In mathematics, the Taylor series or Taylor expansion of a function is an infinite sum of terms that are expressed in terms of the function's derivatives at a single point. For most common functions, the function and the sum of its Taylor serie ...

. This approximation allowed Newton to estimate the rate of precession for arbitrary central forces. Newton applied this approximation to test models of the force causing the apsidal precession of the Moon's orbit. However, the problem of the Moon's motion is dauntingly complex, and Newton never published an accurate gravitational model of the Moon's apsidal precession. After a more accurate model by Clairaut in 1747, analytical models of the Moon's motion were developed in the late 19th century by Hill

A hill is a landform that extends above the surrounding terrain. It often has a distinct Summit (topography), summit.

Terminology

The distinction between a hill and a mountain is unclear and largely subjective, but a hill is universally con ...

, Brown,and Delaunay.

However, Newton's theorem is more general than merely explaining apsidal precession. It describes the effects of adding an inverse-cube force to any central force ''F''(''r''), not only to inverse-square forces such as

Newton's law of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation is usually stated as that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distanc ...

and Coulomb's law

Coulomb's inverse-square law, or simply Coulomb's law, is an experimental law of physics that quantifies the amount of force between two stationary, electrically charged particles. The electric force between charged bodies at rest is conventiona ...

. Newton's theorem simplifies orbital problems in classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a physical theory describing the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, and astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. For objects governed by classical ...

by eliminating inverse-cube forces from consideration. The radial and angular motions, ''r''(''t'') and ''θ''1(''t''), can be calculated without the inverse-cube force; afterwards, its effect can be calculated by multiplying the angular speed of the particle

:

Mathematical statement

Consider a particle moving under an arbitrarycentral force

In classical mechanics, a central force on an object is a force that is directed towards or away from a point called center of force.

: \vec = \mathbf(\mathbf) = \left\vert F( \mathbf ) \right\vert \hat

where \vec F is the force, F is a vecto ...

''F''1(''r'') whose magnitude depends only on the distance ''r'' between the particle and a fixed center. Since the motion of a particle under a central force always lies in a plane, the position of the particle can be described by polar coordinates

In mathematics, the polar coordinate system is a two-dimensional coordinate system in which each point on a plane is determined by a distance from a reference point and an angle from a reference direction. The reference point (analogous to the or ...

(''r'', ''θ''1), the radius and angle of the particle relative to the center of force (Figure 1). Both of these coordinates, ''r''(''t'') and ''θ''1(''t''), change with time ''t'' as the particle moves.

Imagine a second particle with the same mass ''m'' and with the same radial motion ''r''(''t''), but one whose angular speed is ''k'' times faster than that of the first particle. In other words, the azimuthal angle

An azimuth (; from ar, اَلسُّمُوت, as-sumūt, the directions) is an angular measurement in a spherical coordinate system. More specifically, it is the horizontal angle from a cardinal direction, most commonly north.

Mathematicall ...

s of the two particles are related by the equation ''θ''2(''t'') = ''k θ''1(''t''). Newton showed that the motion of the second particle can be produced by adding an inverse-cube central force to whatever force ''F''1(''r'') acts on the first particle

:

where ''L''1 is the magnitude of the first particle's angular momentum

In physics, angular momentum (rarely, moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of linear momentum. It is an important physical quantity because it is a conserved quantity—the total angular momentum of a closed syst ...

, which is a constant of motion In mechanics, a constant of motion is a quantity that is conserved throughout the motion, imposing in effect a constraint on the motion. However, it is a ''mathematical'' constraint, the natural consequence of the equations of motion, rather than ...

(conserved) for central forces.

If ''k''2 is greater than one, ''F''2 − ''F''1 is a negative number; thus, the added inverse-cube force is ''attractive'', as observed in the green planet of Figures 1–4 and 9. By contrast, if ''k''2 is less than one, ''F''2−''F''1 is a positive number; the added inverse-cube force is ''repulsive'', as observed in the green planet of Figures 5 and 10, and in the red planet of Figures 4 and 5.

Alteration of the particle path

The addition of such an inverse-cube force also changes the ''path'' followed by the particle. The path of the particle ignores the time dependencies of the radial and angular motions, such as ''r''(''t'') and ''θ''1(''t''); rather, it relates the radius and angle variables to one another. For this purpose, the angle variable is unrestricted and can increase indefinitely as the particle revolves around the central point multiple times. For example, if the particle revolves twice about the central point and returns to its starting position, its final angle is not the same as its initial angle; rather, it has increased by . Formally, the angle variable is defined as the integral of the angular speed : A similar definition holds for ''θ''2, the angle of the second particle. If the path of the first particle is described in the form , the path of the second particle is given by the function , since . For example, let the path of the first particle be anellipse

In mathematics, an ellipse is a plane curve surrounding two focus (geometry), focal points, such that for all points on the curve, the sum of the two distances to the focal points is a constant. It generalizes a circle, which is the special ty ...

:

where ''A'' and ''B'' are constants; then, the path of the second particle is given by

:

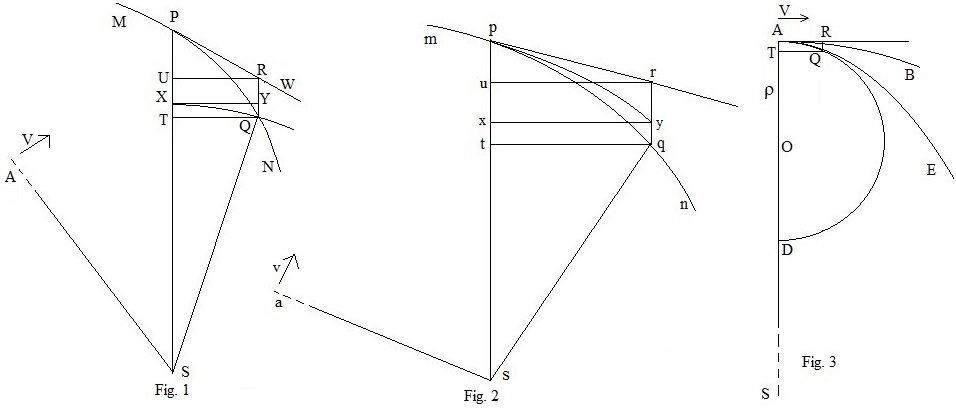

Orbital precession

If ''k'' is close, but not equal, to one, the second orbit resembles the first, but revolves gradually about the center of force; this is known as orbital precession (Figure 3). If ''k'' is greater than one, the orbit precesses in the same direction as the orbit (Figure 3); if ''k'' is less than one, the orbit precesses in the opposite direction. Although the orbit in Figure 3 may seem to rotate uniformly, i.e., at a constant angular speed, this is true only for circular orbits. If the orbit rotates at an angular speed ''Ω'', the angular speed of the second particle is faster or slower than that of the first particle by ''Ω''; in other words, the angular speeds would satisfy the equation . However, Newton's theorem of revolving orbits states that the angular speeds are related by multiplication: , where ''k'' is a constant. Combining these two equations shows that the angular speed of the precession equals . Hence, ''Ω'' is constant only if ''ω''1 is constant. According to the conservation of angular momentum, ''ω''1 changes with the radius ''r'' : where ''m'' and ''L''1 are the first particle'smass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

and angular momentum

In physics, angular momentum (rarely, moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of linear momentum. It is an important physical quantity because it is a conserved quantity—the total angular momentum of a closed syst ...

, respectively, both of which are constant. Hence, ''ω''1 is constant only if the radius ''r'' is constant, i.e., when the orbit is a circle. However, in that case, the orbit does not change as it precesses.

Illustrative example: Cotes's spirals

impact parameter

In physics, the impact parameter is defined as the perpendicular distance between the path of a projectile and the center of a potential field created by an object that the projectile is approaching (see diagram). It is often referred to in ...

, which is defined as the length of the perpendicular from the fixed center to the line of motion. The same radial motion is possible when an inverse-cube central force is added.

Cotes's spiral Introduction

In physics and in the mathematics of plane curves, a Cotes's spiral (also written Cotes' spiral and Cotes spiral) is one of a family of spirals classified by Roger Cotes.

Cotes introduces his analysis of these curves as follows: � ...

s. These are curves defined by the equation

:

where the constant ''k'' equals

:

When the right-hand side of the equation is a positive real number

In mathematics, a real number is a number that can be used to measure a ''continuous'' one-dimensional quantity such as a distance, duration or temperature. Here, ''continuous'' means that values can have arbitrarily small variations. Every real ...

, the solution corresponds to an epispiral. When the argument ''θ''1 – ''θ''0 equals ±90°×''k'', the cosine goes to zero and the radius goes to infinity. Thus, when ''k'' is less than one, the range of allowed angles becomes small and the force is repulsive (red curve on right in Figure 7). On the other hand, when ''k'' is greater than one, the range of allowed angles increases, corresponding to an attractive force (green, cyan and blue curves on left in Figure 7); the orbit of the particle can even wrap around the center several times. The possible values of the parameter ''k'' may range from zero to infinity, which corresponds to values of μ ranging from negative infinity up to the positive upper limit, ''L''12/''m''. Thus, for all attractive inverse-cube forces (negative μ) there is a corresponding epispiral orbit, as for some repulsive ones (μ < ''L''12/''m''), as illustrated in Figure 7. Stronger repulsive forces correspond to a faster linear motion.

hyperbolic cosine

In mathematics, hyperbolic functions are analogues of the ordinary trigonometric functions, but defined using the hyperbola rather than the circle. Just as the points form a circle with a unit radius, the points form the right half of the u ...

:

:

where the constant λ satisfies

:

This form of Cotes's spirals corresponds to one of the two Poinsot's spirals (Figure 8). The possible values of λ range from zero to infinity, which corresponds to values of μ greater than the positive number ''L''12/''m''. Thus, Poinsot spiral motion only occurs for repulsive inverse-cube central forces, and applies in the case that ''L'' is not too large for the given μ.

Taking the limit of ''k'' or λ going to zero yields the third form of a Cotes's spiral, the so-called ''reciprocal spiral'' or ''hyperbolic spiral

A hyperbolic spiral is a plane curve, which can be described in polar coordinates by the equation

:r=\frac

of a hyperbola. Because it can be generated by a circle inversion of an Archimedean spiral, it is called Reciprocal spiral, too..

Pier ...

'', as a solution

:

where ''A'' and ''ε'' are arbitrary constants. Such curves result when the strength μ of the repulsive force exactly balances the angular momentum-mass term

:

Closed orbits and inverse-cube central forces

central force

In classical mechanics, a central force on an object is a force that is directed towards or away from a point called center of force.

: \vec = \mathbf(\mathbf) = \left\vert F( \mathbf ) \right\vert \hat

where \vec F is the force, F is a vecto ...

s—those that increase linearly with distance, ''F = Cr'', such as Hooke's law

In physics, Hooke's law is an empirical law which states that the force () needed to extend or compress a spring (device), spring by some distance () Proportionality (mathematics)#Direct_proportionality, scales linearly with respect to that ...

, and inverse-square forces, , such as Newton's law of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation is usually stated as that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distanc ...

and Coulomb's law

Coulomb's inverse-square law, or simply Coulomb's law, is an experimental law of physics that quantifies the amount of force between two stationary, electrically charged particles. The electric force between charged bodies at rest is conventiona ...

—have a very unusual property. A particle moving under either type of force always returns to its starting place with its initial velocity, provided that it lacks sufficient energy to move out to infinity. In other words, the path of a bound particle is always closed and its motion repeats indefinitely, no matter what its initial position or velocity. As shown by Bertrand's theorem

In classical mechanics, Bertrand's theorem states that among central-force potentials with bound orbits, there are only two types of central-force (radial) scalar potentials with the property that all bound orbits are also closed orbits.

The f ...

, this property is not true for other types of forces; in general, a particle will not return to its starting point with the same velocity.

However, Newton's theorem shows that an inverse-cubic force may be applied to a particle moving under a linear or inverse-square force such that its orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as a p ...

remains closed, provided that ''k'' equals a rational number

In mathematics, a rational number is a number that can be expressed as the quotient or fraction of two integers, a numerator and a non-zero denominator . For example, is a rational number, as is every integer (e.g. ). The set of all ration ...

. (A number is called "rational" if it can be written as a fraction ''m''/''n'', where ''m'' and ''n'' are integers.) In such cases, the addition of the inverse-cubic force causes the particle to complete ''m'' rotations about the center of force in the same time that the original particle completes ''n'' rotations. This method for producing closed orbits does not violate Bertrand's theorem, because the added inverse-cubic force depends on the initial velocity of the particle.

Limit of nearly circular orbits

In Proposition 45 of his ''Principia'', Newton applies his theorem of revolving orbits to develop a method for finding the force laws that govern the motions of planets.Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

had noted that the orbits of most planets and the Moon seemed to be ellipses, and the long axis of those ellipses can determined accurately from astronomical measurements. The long axis is defined as the line connecting the positions of minimum and maximum distances to the central point, i.e., the line connecting the two apses

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

. For illustration, the long axis of the planet Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

is defined as the line through its successive positions of perihelion and aphelion. Over time, the long axis of most orbiting bodies rotates gradually, generally no more than a few degrees per complete revolution, because of gravitational perturbations from other bodies, oblateness in the attracting body, general relativistic effects, and other effects. Newton's method uses this apsidal precession as a sensitive probe of the type of force being applied to the planets.

Newton's theorem describes only the effects of adding an inverse-cube central force. However, Newton extends his theorem to an arbitrary central force ''F''(''r'') by restricting his attention to orbits that are nearly circular, such as ellipses with low orbital eccentricity

In astrodynamics, the orbital eccentricity of an astronomical object is a dimensionless parameter that determines the amount by which its orbit around another body deviates from a perfect circle. A value of 0 is a circular orbit, values betwee ...

(''ε'' ≤ 0.1), which is true of seven of the eight planetary orbits in the solar system

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

. Newton also applied his theorem to the planet Mercury, which has an eccentricity ''ε ''of roughly 0.21, and suggested that it may pertain to Halley's comet

Halley's Comet or Comet Halley, officially designated 1P/Halley, is a short-period comet visible from Earth every 75–79 years. Halley is the only known short-period comet that is regularly visible to the naked eye from Earth, and thus the o ...

, whose orbit has an eccentricity of roughly 0.97.

A qualitative justification for this extrapolation of his method has been suggested by Valluri, Wilson and Harper. According to their argument, Newton considered the apsidal precession angle α (the angle between the vectors of successive minimum and maximum distance from the center) to be a smooth

Smooth may refer to:

Mathematics

* Smooth function, a function that is infinitely differentiable; used in calculus and topology

* Smooth manifold, a differentiable manifold for which all the transition maps are smooth functions

* Smooth algebrai ...

, continuous function

In mathematics, a continuous function is a function such that a continuous variation (that is a change without jump) of the argument induces a continuous variation of the value of the function. This means that there are no abrupt changes in value ...

of the orbital eccentricity ε. For the inverse-square force, α equals 180°; the vectors to the positions of minimum and maximum distances lie on the same line. If α is initially not 180° at low ε (quasi-circular orbits) then, in general, α will equal 180° only for isolated values of ε; a randomly chosen value of ε would be very unlikely to give α = 180°. Therefore, the observed slow rotation of the apsides of planetary orbits suggest that the force of gravity is an inverse-square law.

Quantitative formula

To simplify the equations, Newton writes ''F''(''r'') in terms of a new function ''C''(''r'') : where ''R'' is the average radius of the nearly circular orbit. Newton expands ''C''(''r'') in a series—now known as aTaylor expansion

In mathematics, the Taylor series or Taylor expansion of a function is an infinite sum of terms that are expressed in terms of the function's derivatives at a single point. For most common functions, the function and the sum of its Taylor serie ...

—in powers of the distance ''r'', one of the first appearances of such a series. By equating the resulting inverse-cube force term with the inverse-cube force for revolving orbits, Newton derives an equivalent angular scaling factor ''k'' for nearly circular orbits:

:

In other words, the application of an arbitrary central force ''F''(''r'') to a nearly circular elliptical orbit can accelerate the angular motion by the factor ''k'' without affecting the radial motion significantly. If an elliptical orbit is stationary, the particle rotates about the center of force by 180° as it moves from one end of the long axis to the other (the two apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an ''exedra''. In ...

s). Thus, the corresponding apsidal angle ''α'' for a general central force equals ''k''×180°, using the general law .

Examples

Newton illustrates his formula with three examples. In the first two, the central force is apower law

In statistics, a power law is a Function (mathematics), functional relationship between two quantities, where a Relative change and difference, relative change in one quantity results in a proportional relative change in the other quantity, inde ...

, , so ''C''(''r'') is proportional to ''r''''n''. The formula above indicates that the angular motion is multiplied by a factor , so that the apsidal angle ''α'' equals 180°/.

This angular scaling can be seen in the apsidal precession, i.e., in the gradual rotation of the long axis of the ellipse (Figure 3). As noted above, the orbit as a whole rotates with a mean angular speed ''Ω''=(''k''−1)''ω'', where ''ω'' equals the mean angular speed of the particle about the stationary ellipse. If the particle requires a time ''T'' to move from one apse to the other, this implies that, in the same time, the long axis will rotate by an angle ''β'' = Ω''T'' = (''k'' − 1)''ωT'' = (''k'' − 1)×180°. For an inverse-square law such as Newton's law of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation is usually stated as that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distanc ...

, where ''n'' equals 1, there is no angular scaling (''k'' = 1), the apsidal angle ''α'' is 180°, and the elliptical orbit is stationary (Ω = ''β'' = 0).

As a final illustration, Newton considers a sum of two power laws

:

which multiplies the angular speed by a factor

:

Newton applies both of these formulae (the power law and sum of two power laws) to examine the apsidal precession of the Moon's orbit.

Precession of the Moon's orbit

The motion of the

The motion of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

can be measured accurately, and is noticeably more complex than that of the planets. The ancient Greek astronomers, Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

, had noted several periodic variations in the Moon's orbit, such as small oscillations in its orbital eccentricity

In astrodynamics, the orbital eccentricity of an astronomical object is a dimensionless parameter that determines the amount by which its orbit around another body deviates from a perfect circle. A value of 0 is a circular orbit, values betwee ...

and the inclination

Orbital inclination measures the tilt of an object's orbit around a celestial body. It is expressed as the angle between a Plane of reference, reference plane and the orbital plane or Axis of rotation, axis of direction of the orbiting object ...

of its orbit to the plane of the ecliptic

The ecliptic or ecliptic plane is the orbital plane of the Earth around the Sun. From the perspective of an observer on Earth, the Sun's movement around the celestial sphere over the course of a year traces out a path along the ecliptic again ...

. These oscillations generally occur on a once-monthly or twice-monthly time-scale. The line of its apses

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

precesses gradually with a period of roughly 8.85 years, while its line of nodes

An orbital node is either of the two points where an orbit intersects a plane of reference to which it is inclined. A non-inclined orbit, which is contained in the reference plane, has no nodes.

Planes of reference

Common planes of refere ...

turns a full circle in roughly double that time, 18.6 years. This accounts for the roughly 18-year periodicity of eclipse

An eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when an astronomical object or spacecraft is temporarily obscured, by passing into the shadow of another body or by having another body pass between it and the viewer. This alignment of three ce ...

s, the so-called Saros cycle

The saros () is a period of exactly 223 synodic months, approximately 6585.3211 days, or 18 years, 10, 11, or 12 days (depending on the number of leap years), and 8 hours, that can be used to predict eclipses of the Sun and Moon. One saros period ...

. However, both lines experience small fluctuations in their motion, again on the monthly time-scale.

In 1673, Jeremiah Horrocks

Jeremiah Horrocks (16183 January 1641), sometimes given as Jeremiah Horrox (the Latinised version that he used on the Emmanuel College register and in his Latin manuscripts), – See footnote 1 was an English astronomer. He was the first person ...

published a reasonably accurate model of the Moon's motion in which the Moon was assumed to follow a precessing elliptical orbit. A sufficiently accurate and simple method for predicting the Moon's motion would have solved the navigational problem of determining a ship's longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter l ...

; in Newton's time, the goal was to predict the Moon's position to 2' (two arc-minutes), which would correspond to a 1° error in terrestrial longitude.Smith, p. 254. Horrocks' model predicted the lunar position with errors no more than 10 arc-minutes; for comparison, the diameter of the Moon is roughly 30 arc-minutes.

Newton used his theorem of revolving orbits in two ways to account for the apsidal precession of the Moon.Newton, ''Principia'', Book I, Section IX, Proposition 45, pp. 141–147. First, he showed that the Moon's observed apsidal precession could be accounted for by changing the force law of gravity from an inverse-square law to a power law

In statistics, a power law is a Function (mathematics), functional relationship between two quantities, where a Relative change and difference, relative change in one quantity results in a proportional relative change in the other quantity, inde ...

in which the exponent was (roughly 2.0165)

:

In 1894, Asaph Hall

Asaph Hall III (October 15, 1829 – November 22, 1907) was an American astronomer who is best known for having discovered the two moons of Mars, Deimos and Phobos, in 1877. He determined the orbits of satellites of other planets and of double ...

adopted this approach of modifying the exponent in the inverse-square law slightly to explain an anomalous orbital precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In othe ...

of the planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

, which had been observed in 1859 by Urbain Le Verrier

Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier FRS (FOR) HFRSE (; 11 March 1811 – 23 September 1877) was a French astronomer and mathematician who specialized in celestial mechanics and is best known for predicting the existence and position of Neptune using ...

.Ironically, Hall's theory was ruled out by careful astronomical observations of the Moon. The currently accepted explanation for this precession involves the theory of

general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

, which (to first approximation) adds an inverse-quartic force, i.e., one that varies as the inverse fourth power of distance.

As a second approach to explaining the Moon's precession, Newton suggested that the perturbing influence of the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

on the Moon's motion might be approximately equivalent to an additional linear force

:

The first term corresponds to the gravitational attraction between the Moon and the Earth, where ''r'' is the Moon's distance from the Earth. The second term, so Newton reasoned, might represent the average perturbing force of the Sun's gravity of the Earth-Moon system. Such a force law could also result if the Earth were surrounded by a spherical dust cloud of uniform density. Using the formula for ''k'' for nearly circular orbits, and estimates of ''A'' and ''B'', Newton showed that this force law could not account for the Moon's precession, since the predicted apsidal angle ''α'' was (≈ 180.76°) rather than the observed α (≈ 181.525°). For every revolution, the long axis would rotate 1.5°, roughly half of the observed 3.0°

Generalization

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

first published his theorem in 1687, as Propositions 43–45 of Book I of his ''Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica

(English: ''Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy'') often referred to as simply the (), is a book by Isaac Newton that expounds Newton's laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation. The ''Principia'' is written in Latin and ...

''. However, as astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar noted in his 1995 commentary on Newton's ''Principia'', the theorem remained largely unknown and undeveloped for over three centuries.

The first generalization of Newton's theorem was discovered by Mahomed and Vawda in 2000. As Newton did, they assumed that the angular motion of the second particle was ''k'' times faster than that of the first particle, . In contrast to Newton, however, Mahomed and Vawda did not require that the radial motion of the two particles be the same, . Rather, they required that the inverse radii be related by a linear equation

:

This transformation of the variables changes the path of the particle. If the path of the first particle is written , the second particle's path can be written as

:

If the motion of the first particle is produced by a central force ''F''1(''r''), Mahomed and Vawda showed that the motion of the second particle can be produced by the following force

:

According to this equation, the second force ''F''2(''r'') is obtained by scaling the first force and changing its argument, as well as by adding inverse-square and inverse-cube central forces.

For comparison, Newton's theorem of revolving orbits corresponds to the case and , so that . In this case, the original force is not scaled, and its argument is unchanged; the inverse-cube force is added, but the inverse-square term is not. Also, the path of the second particle is , consistent with the formula given above.

Derivations

Newton's derivation

Newton's derivation is found in Section IX of his '' Principia'', specifically Propositions 43–45.Chandrasekhar, pp. 183–192. His derivations of these Propositions are based largely on geometry. ; Proposition 43; Problem 30central force

In classical mechanics, a central force on an object is a force that is directed towards or away from a point called center of force.

: \vec = \mathbf(\mathbf) = \left\vert F( \mathbf ) \right\vert \hat

where \vec F is the force, F is a vecto ...

. Newton showed that a force is central if and only if the particle sweeps out equal areas in equal times as measured from the center.

Newton's derivation begins with a particle moving under an arbitrary central force ''F''1(''r''); the motion of this particle under this force is described by its radius ''r''(''t'') from the center as a function of time, and also its angle θ1(''t''). In an infinitesimal time ''dt'', the particle sweeps out an approximate right triangle whose area is

:

Since the force acting on the particle is assumed to be a central force, the particle sweeps out equal angles in equal times, by Newton's Proposition 2. Expressed another way, the ''rate'' of sweeping out area is constant

:

This constant ''areal velocity'' can be calculated as follows. At the apapsis and periapsis, the positions of closest and furthest distance from the attracting center, the velocity and radius vectors are perpendicular; therefore, the angular momentum

In physics, angular momentum (rarely, moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of linear momentum. It is an important physical quantity because it is a conserved quantity—the total angular momentum of a closed syst ...

''L1'' per mass ''m'' of the particle (written as ''h''1) can be related to the rate of sweeping out areas

:

Now consider a second particle whose orbit is identical in its radius, but whose angular variation is multiplied by a constant factor ''k''

:

The areal velocity of the second particle equals that of the first particle multiplied by the same factor ''k''

:

Since ''k'' is a constant, the second particle also sweeps out equal areas in equal times. Therefore, by Proposition 2, the second particle is also acted upon by a central force ''F''2(''r''). This is the conclusion of Proposition 43.

; Proposition 44

:''The difference of the forces, by which two bodies may be made to move equally, one in a fixed, the other in the same orbit revolving, varies inversely as the cube of their common altitudes.''

To find the magnitude of ''F''2(''r'') from the original central force ''F''1(''r''), Newton calculated their difference using geometry and the definition of centripetal acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Accelerations are vector quantities (in that they have magnitude and direction). The orientation of an object's acceleration is given by th ...

. In Proposition 44 of his ''Principia'', he showed that the difference is proportional to the inverse cube of the radius, specifically by the formula given above, which Newtons writes in terms of the two constant areal velocities, ''h''1 and ''h''2

:

; Proposition 45; Problem 31

:''To find the motion of the apsides in orbits approaching very near to circles.''

In this Proposition, Newton derives the consequences of his theorem of revolving orbits in the limit of nearly circular orbits. This approximation is generally valid for planetary orbits and the orbit of the Moon about the Earth. This approximation also allows Newton to consider a great variety of central force laws, not merely inverse-square and inverse-cube force laws.

Modern derivation

Modern derivations of Newton's theorem have been published byWhittaker

Whittaker is a surname of English origin, meaning 'white acre', and a given name. Variants include Whitaker and Whitacre (disambiguation), Whitacre. People with the name include:

Surname

A

*Aaron Whittaker (born 1968), New Zealand rugby player ...

(1937)Whittaker, p. 83. and Chandrasekhar Chandrasekhar, Chandrashekhar or Chandra Shekhar is an Indian name and may refer to a number of individuals. The name comes from the name of an incarnation of the Hindu god Shiva. In this form he married the goddess Parvati. Etymologically, the nam ...

(1995). By assumption, the second angular speed is ''k'' times faster than the first

:

Since the two radii have the same behavior with time, ''r''(''t''), the conserved angular momenta are related by the same factor ''k''

:

The equation of motion for a radius ''r'' of a particle of mass ''m'' moving in a central potential

In classical mechanics, a central force on an object is a force that is directed towards or away from a point called center of force.

: \vec = \mathbf(\mathbf) = \left\vert F( \mathbf ) \right\vert \hat

where \vec F is the force, F is a vecto ...

''V''(''r'') is given by Lagrange's equations

In physics, Lagrangian mechanics is a formulation of classical mechanics founded on the stationary-action principle (also known as the principle of least action). It was introduced by the Italian-French mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Lo ...

:

Applying the general formula to the two orbits yields the equation

:

which can be re-arranged to the form

:

This equation relating the two radial forces can be understood qualitatively as follows. The difference in angular speeds (or equivalently, in angular momenta) causes a difference in the centripetal force

A centripetal force (from Latin ''centrum'', "center" and ''petere'', "to seek") is a force that makes a body follow a curved path. Its direction is always orthogonal to the motion of the body and towards the fixed point of the instantaneous c ...

requirement; to offset this, the radial force must be altered with an inverse-cube force.

Newton's theorem can be expressed equivalently in terms of potential energy

In physics, potential energy is the energy held by an object because of its position relative to other objects, stresses within itself, its electric charge, or other factors.

Common types of potential energy include the gravitational potentia ...

, which is defined for central forces

:

The radial force equation can be written in terms of the two potential energies

:

Integrating with respect to the distance ''r'', Newtons's theorem states that a ''k''-fold change in angular speed results from adding an inverse-square potential energy to any given potential energy ''V''1(''r'')

:

Newton’s Geometric Proof from the Principia

Simplified Geometric Proof of Proposition 44

Although Newton states that the problem was to be solved by Proposition 6, he does not use it explicitly. In the following, simplified proof, Proposition 6 is used to show how the result is derived. Newton's detailed proof follows that, and finally Proposition 6 is appended, as it is not well-known. Proposition 44 uses Proposition 6 to prove a result about revolving orbits. In the propositions following Proposition 6 in Section 2 of the Principia, he applies it to specific curves, for example, conic sections. In the case of Proposition 44, it is applied to any orbit, under the action of an arbitrary force directed towards a fixed point, to produce a corresponding revolving orbit. In Fig. 1, MN is part of that orbit. At point P, the body moves to Q under the action of a force directed towards S, as before. The force, F(SP) is defined at each point P on the curve. In Fig. 2, the corresponding part of the revolving orbit is mn with s as its centre of force. Assume that initially, the body in the static orbit starts out at right angles to the radius with speed V. The body in the revolving orbit must also start at right angles and assume its speed is v. In the case shown in Fig. 1, and the force is directed towards S. The argument applies equally if . Also, the force may be directed away from the centre. Let SA be the initial direction of the static orbit, and sa, that of the revolving orbit. If after a certain time the bodies in the respective orbits are at P and p, then the ratios of the angles ; the ratios of the areas ; and the radii , , . The figure pryx and the arc py in Fig. 2 are the figure PRQT and the arc PQ in Fig. 1, expanded linearly in the horizontal direction in the ratio , so that , , and . The straight lines qt and QT should really be circular arcs with centres s and S and radii sq and SQ respectively. In the limit, their ratio becomes , whether they are straight lines or arcs. Since in the limit the forces are parallel to SP and sp, if the same force acted on the body in Fig. 2 as in Fig. 1, the body would arrive at y, since ry = RQ. The difference in horizontal speed does not affect the vertical distances. Newton refers to Corollary 2 of the Laws of Motion, where the motion of the bodies is resolved into a component in the radial direction acted on by the whole force, and the other component transverse to it, acted on by no force. However, the distance from y to the centre, s, is now greater than SQ, so an additional force is required to move the body to q such that sq = SQ. The extra force is represented by yq, and f is proportional to ry + yq, just as F is to RQ. , . The difference, , can be found as follows: , , so . And in the limit, as QT and qt approach zero, becomes equal to or 2SP so . Therefore, . Since from Proposition 6 (Fig.1 and see below), the force is . Divide by , where k is constant, to obtain the forces . In Fig. 3, at the initial point A of the static curve, draw the tangent AR, which is perpendicular to SA, and the circle AQD, which just touches the curve at A. Let ρ be the radius of that circle. Since angle SAR is a right angle, the centre of the circle lies on SA. From the property of a circle: , and in the limit as Q approaches A, this becomes . Hence, . And since F(SA) is given, this determines the constant k. However, Newton wants the force at A to be of the form , where c is a constant, so that , where . The expression for f(sp) above is the same as Newton's in Corollary 4 of Proposition 44, except that he uses different letters. He writes (where G and F are not necessarily equal to v and V respectively), and uses the letter “V” for the constant corresponding to “c”, and the letter “X” for the function F(sp). The above geometric proof shows very clearly where the additional force arises from to make the orbit revolve with respect to the static orbit.Newton’s Proof of Proposition 44

Newton's proof is complicated, in view of the simplicity of the above proof. As an example, his proof requires some deciphering, as the following sentence shows: “And therefore, if with centre C and any radius CP or Cp a circular sector is described equal to the total area VPC which the body P revolving in an immobile orbit has described in any time by a radius drawn to the centre, the difference between the forces by which the body P in an immobile orbit and body p in a mobile orbit revolve will be to the centripetal force by which some body, by a radius drawn to the centre, would have been able to describe that sector uniformly in the same time in which the area VPC was described as G2 - F2 to F2.” He initially regards the infinitesimal as fixed, then the areas SPQ and spq are proportional to V and v, respectively; therefore, and at each of the points P and p, and so the additional force varies inversely as the cube of the radius. In Fig.1, XQ is a circular arc, with centre S and radius SQ, meeting SP at X. The perpendicular XY meets RQ at Y, and . Let be the force required to make a body move in a circle of radius SQ, if it has the same speed as the transverse speed of the body in the static orbit at Q. at every point, P and in particular at the apside, A: . But at A, in Fig. 3., the ratio of the force that makes the body follow the static curve, AE, to that required to make it follow the circle, AB, with radius SA, is inversely as the ratio of their radii of curvature, since they are both moving at the same speed, V, perpendicular to SA: . From the first part of the proof, . Substituting Newton's expression for F(SA), gives the result obtained previously.Newton’s Proof of Proposition 45

“To find the motion of the apsides in orbits approaching circles.” Proposition 44 was devised expressly to prove this Proposition. Newton wants to investigate the motion of a body in a nearly circular orbit attracted by a force of the form . He approximates the static curve by an ellipse with an inverse square force, F(SP), directed to one of the foci, made to revolve by the addition of an inverse cube force, according to Proposition 44. For the static ellipse, with the force varying inversely as SP squared, , since c is defined above so that . With the body in the static orbit starting from the upper apside at A, it will reach the lower apside, the point closest to S, after moving through an angle of 180 degrees. Newton wants a corresponding revolving orbit starting from apside, a, about a point s, with the lower apside shifted by an angle, α, where . The initial speed, V, at A must be just less than that required to make the body move in a circle. Then ρ can be taken as equal to SA or sa. The problem is to determine v from the value of n, so that α can be found, or given α, to find n. Letting , . Then “by our method of converging series”: plus terms in X2 and above which can be ignored because the orbit is almost circular, so X is small compared to sa. Comparing the 2 expressions for f(sp), it follows that . Also, . The ratio of the initial forces at a is given by .Proposition 6 for Proof of Proposition 44, above

In Fig. 1, a body is moving along a specific curve MN acted on by a (centripetal) force, towards the fixed point S. The force depends only of the distance of the point from S. The aim of this proposition is to determine how the force varies with the radius, SP. The method applies equally to the case where the force is centrifugal. In a small time, , the body moves from P to the nearby point Q. Draw QR parallel to SP meeting the tangent at R, and QT perpendicular to SP meeting it at T. If there was no force present it would have moved along the tangent at P with the speed that it had at P, arriving at the point, R. If the force on the body moving from P to Q was constant in magnitude and parallel to the direction SP, the arc PQ would be parabolic with PR as its tangent and QR would be proportional to that constant force and the square of the time, . Conversely, if instead of arriving at R, the body was deflected to Q, then a constant force parallel to SP, with magnitude: would have caused it to reach Q instead of R. However, since the direction of the radius from S to points on the arc PQ and also the magnitude of the force towards S will change along PQ, the above relation will not give the exact force at P. If Q is sufficiently close to P, the direction of force will be almost parallel to SP all along PQ and if the force changes little, PQ can be assumed to be approximated by a parabolic arc with the force given as above in terms of QR and . The time, is proportional to the area of the sector SPQ. This is Kepler's Second Law. A proof is demonstrated in Proposition 1, Book 1, in the Principia. Since the arc PQ can be approximated by a straight line, the area of the sector SPQ and the area of the triangle SPQ can be taken as equal, so , where k is constant. Again, this is not exact for finite lengths PQ. The force law is obtained if the limit of the above expression exists as a function of SP, as PQ approaches zero. In fact, in time , the body with no force would have reached a point, W, further from P than R. However, in the limit QW becomes parallel to SP. The point W is ignored in Newton's proof. Also, Newton describes QR as the versed sine of the arc with P at its centre and length twice QP. Although this is not strictly the same as the QR that he has in the diagram (Fig.1), in the limit, they become equal. Notes: This proposition is based on Galileo's analysis of a body following a parabolic trajectory under the action of a constant acceleration. In Proposition 10, he describes it as Galileo's Theorem, and mentions Galileo several other times in relation to it in the Principia. Combining it with Kepler's Second Law gives the simple and elegant method. In the historically very important case where MN in Fig. 1 was part of an ellipse and S was one of its foci, Newton showed in Proposition 11 that the limit was constant at each point on the curve, so that the force on the body directed towards the fixed point S varied inversely as the square of the distance SP. Besides the ellipse with the centre at the focus, Newton also applied Proposition 6 to the hyperbola (Proposition 12), the parabola (Proposition 13), the ellipse with the centre of force at the centre of the ellipse (Proposition 10), the equiangular spiral (Proposition 9), and the circle with the centre of force not coinciding with the centre, and even on the circumference (Proposition 7).See also

*Kepler problem

In classical mechanics, the Kepler problem is a special case of the two-body problem, in which the two bodies interact by a central force ''F'' that varies in strength as the inverse square of the distance ''r'' between them. The force may be ei ...

* Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector

In classical mechanics, the Laplace–Runge–Lenz (LRL) vector is a vector used chiefly to describe the shape and orientation of the orbit of one astronomical body around another, such as a binary star or a planet revolving around a star. For t ...

* Two-body problem in general relativity

The two-body problem in general relativity is the determination of the motion and gravitational field of two bodies as described by the field equations of general relativity. Solving the Kepler problem is essential to calculate the bending of lig ...

* Newton's theorem about ovals

In mathematics, Newton's theorem about ovals states that the area cut off by a secant of a smooth convex oval is not an algebraic function of the secant.

Isaac Newton stated it as lemma 28 of section VI of book 1 of Newton's '' Pri ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* (séance du lundi 20 Octobre 1873) * * * * * Alternative translation of earlier (2nd) edition of Newton's ''Principia''. * * *External links

Three-body problem

discussed by Alain Chenciner at

Scholarpedia

''Scholarpedia'' is an English-language wiki-based online encyclopedia with features commonly associated with open-access online academic journals, which aims to have quality content in science and medicine.

''Scholarpedia'' articles are written ...

{{good article

Classical mechanics

Concepts in physics

Articles containing video clips