New York American on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in

Hearst to Merge New York Papers: American will cease as separate publication

''

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

from 1937 to 1966. The ''Journal-American'' was the product of a merger between two New York newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

: The ''New York American'' (originally the ''New York Journal'', renamed ''American'' in 1901), a morning paper, and the ''New York Evening Journal'', an afternoon paper. Both were published by Hearst from 1895 to 1937. The ''American'' and ''Evening Journal'' merged in 1937.

History

Beginnings

''New York Morning Journal''

Joseph Pulitzer's younger brother Albert founded the ''New York Morning Journal'' in 1882. After three years of its existence, John R. McLean briefly acquired the paper in 1895. It was renamed ''The Journal''. But a year later in 1896, he sold it to Hearst.(23 June 1937)Hearst to Merge New York Papers: American will cease as separate publication

''

Miami News

''The Miami News'' was an evening newspaper in Miami, Florida. It was the media market competitor to the morning edition of the ''Miami Herald'' for most of the 20th century. The paper started publishing in May 1896 as a weekly called ''The Miami ...

'' (Associated Press story)

''New York American''

In 1901, the morning newspaper was renamed ''New York American''.''New York Evening Journal''

Hearst founded the ''New York Evening Journal'' about a year later in 1896. He entered into a circulation war with the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publ ...

'', the newspaper run by his former mentor Joseph Pulitzer and from whom he stole the cartoonist

A cartoonist is a visual artist who specializes in both drawing and writing cartoons (individual images) or comics (sequential images). Cartoonists differ from comics writers or comic book illustrators in that they produce both the literary an ...

s George McManus

George McManus (January 23, 1884 – October 22, 1954) was an American cartoonist best known as the creator of Irish immigrant Jiggs and his wife Maggie, the main characters of his syndicated comic strip, ''Bringing Up Father''.

Biography

...

and Richard F. Outcault. In October 1896, Outcault defected to Hearst's ''New York Journal''. Because Outcault had failed in his effort to copyright '' The Yellow Kid'' both newspapers published versions of the comic feature with George Luks providing the ''New York World'' with their version after Outcault left. ''The Yellow Kid'' was one of the first comic strips to be printed in color and gave rise to the phrase yellow journalism

Yellow journalism and yellow press are American terms for journalism and associated newspapers that present little or no legitimate, well-researched news while instead using eye-catching headlines for increased sales. Techniques may include ...

, used to describe the sensationalist and often exaggerated articles, which helped, along with a one-cent price tag, to greatly increase circulation of the newspaper. Many believed that as part of this, aside from any nationalistic sentiment, Hearst may have helped to initiate the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cl ...

of 1898 with lurid exposes of Spanish atrocities against insurgents and foreign journalists.

''New York Journal-American''

In 1937, both newspapers, the morning paper known as ''New York American'' (since 1901) and the evening paper ''New York Evening Journal'' merged in one publication renamed ''New York Journal-American''. The ''Journal-American'' was a publication with several editions in the afternoon and evening.Comics

In the early 1900s, Hearst weekday morning and afternoon papers around the country featured scattered black-and-white comic strips, and on January 31, 1912, Hearst introduced the nation's first full daily comics page in the ''Evening Journal''. On January 12, 1913, McManus launched his '' Bringing Up Father'' comic strip. The comics expanded into two full pages daily and a 12-page Sunday color section with leadingKing Features Syndicate

King Features Syndicate, Inc. is a American content distribution and animation studio, consumer product licensing and print syndication company owned by Hearst Communications that distributes about 150 comic strips, newspaper columns, editoria ...

strips. By the mid-1940s, the newspaper's Sunday comics included ''Bringing Up Father'', '' Blondie'', a full-page '' Prince Valiant'', '' Flash Gordon'', '' The Little King'', '' Buz Sawyer'', Feg Murray's ''Seein' Stars'', ''Tim Tyler's Luck

''Tim Tyler's Luck'' is an adventure comic strip created by Lyman Young, elder brother of '' Blondie'' creator Chic Young. Distributed by King Features Syndicate, the strip ran from August 13, 1928, until August 24, 1996.

Characters and story

Wh ...

'', Gene Ahern's ''Room and Board'' and ''The Squirrel Cage'', ''The Phantom

''The Phantom'' is an American adventure comic strip, first published by Lee Falk in February 1936. The main character, the Phantom, is a fictional costumed crime-fighter who operates from the fictional African country of Bangalla. The ch ...

'', '' Jungle Jim'', '' Tillie the Toiler'', '' Little Annie Rooney'', '' Little Iodine'', Bob Green's ''The Lone Ranger'', ''Believe It or Not!'', ''Uncle Remus'', ', ''Donald Duck'', ''Tippie'', ''Right Around Home'', '' Barney Google and Snuffy Smith'', and '' The Katzenjammer Kids''.

Tad Dorgan, known for his boxing and dog cartoons, as well as the comic character Judge Rummy, joined the ''Journal''Popeye

Popeye the Sailor Man is a fictional cartoon character created by E. C. Segar, Elzie Crisler Segar.Grandma'', Don Tobin's ''The Little Woman'', '' Mandrake the Magician'', Don Flowers' ''Glamor Girls'', '' Grin and Bear It'', and '' Buck Rogers'', and other strips.

Rube Goldberg and Einar Nerman also became cartoonists with the ''Journal-American''.

The ''Evening Journal'' was home to famed investigative reporter Nellie Bly, who began writing for the paper in 1914 as a war correspondent from the battlefields of World War I. Bly eventually returned to the United States and was given her own column that she wrote right up until her death in 1922.

Popular columnists included

The ''Evening Journal'' was home to famed investigative reporter Nellie Bly, who began writing for the paper in 1914 as a war correspondent from the battlefields of World War I. Bly eventually returned to the United States and was given her own column that she wrote right up until her death in 1922.

Popular columnists included

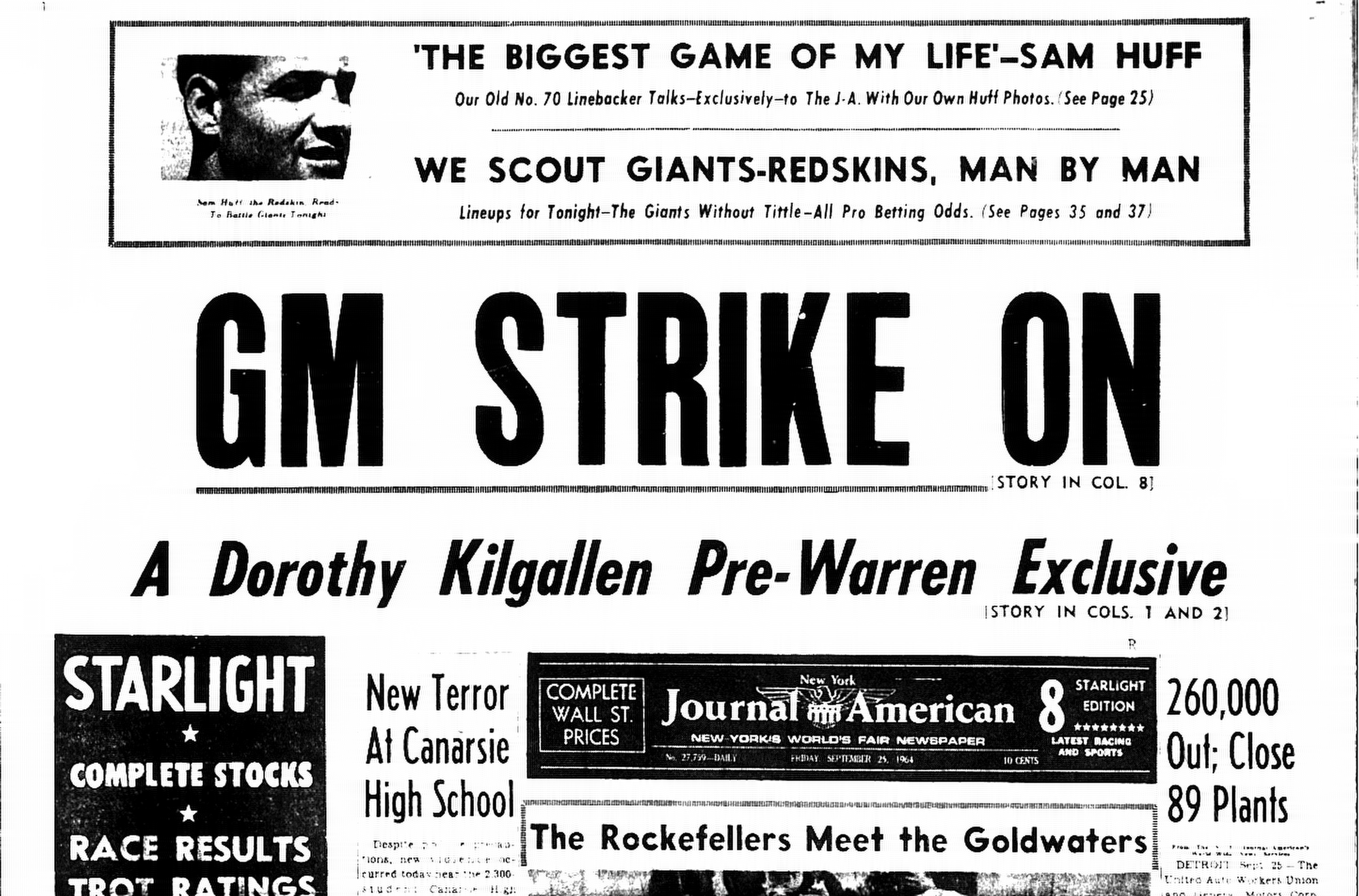

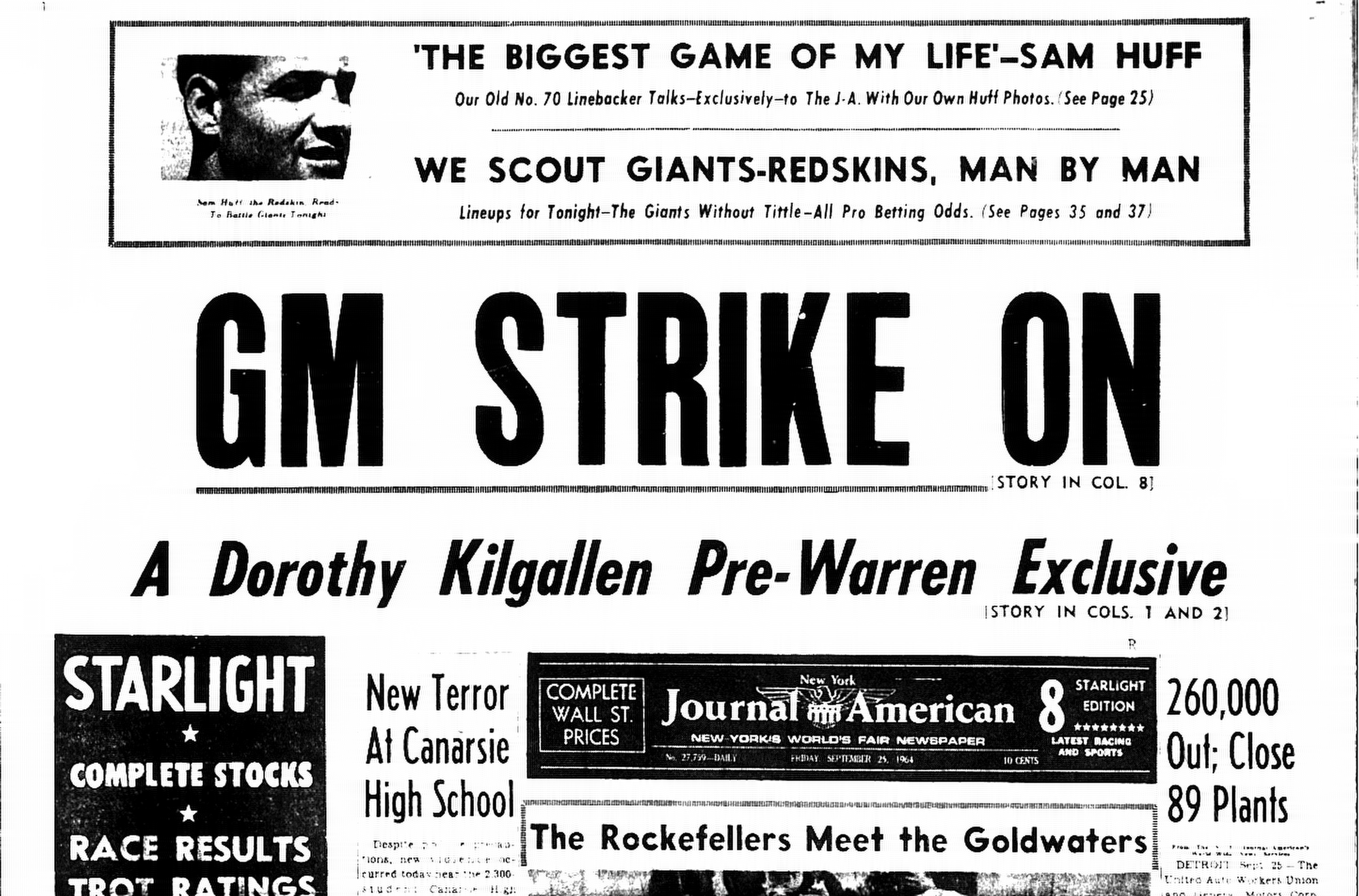

It published enlarged photographs of civil rights demonstrations, Dorothy Kilgallen's skepticism about the Warren Commission report as well as many reporters' stories on the increasing crime rate in New York's five boroughs.

Most of the front page of the Sunday edition of January 12, 1964 ran stories that were relevant to the previous day's announcement by U.S. Surgeon General Luther Terry that "a blue ribbon committee of scientists and doctors," in the words of reporter Jack Pickering, had concluded that cigarette smoking was dangerous.

The ''Journal-American''s feel of the pulse of the changing times of the mid-1960s hid the trouble that was going on behind the scenes at the paper, which was unknown to many New Yorkers until after it had ceased publication.

Besides trouble with advertisers, another major factor that led to the ''Journal-American''s demise was a power struggle between Hearst CEO

It published enlarged photographs of civil rights demonstrations, Dorothy Kilgallen's skepticism about the Warren Commission report as well as many reporters' stories on the increasing crime rate in New York's five boroughs.

Most of the front page of the Sunday edition of January 12, 1964 ran stories that were relevant to the previous day's announcement by U.S. Surgeon General Luther Terry that "a blue ribbon committee of scientists and doctors," in the words of reporter Jack Pickering, had concluded that cigarette smoking was dangerous.

The ''Journal-American''s feel of the pulse of the changing times of the mid-1960s hid the trouble that was going on behind the scenes at the paper, which was unknown to many New Yorkers until after it had ceased publication.

Besides trouble with advertisers, another major factor that led to the ''Journal-American''s demise was a power struggle between Hearst CEO

File:Full confession of H. H. Holmes.pdf, ''The Journal'' April 12, 1896 front page with Holmes mugshots

File:Full confession of H. H. Holmes (page 2).pdf, ''The Journal'' April 12, 1896 showing at the top Holmes "Murder Castle" and at bottom the trunk used by Holmes to kill the Pietzel sisters

File:Full confession of H. H. Holmes (page 3).pdf, ''The Journal'' April 12, 1896 showing at center pictures of 10 known victims of Holmes

File:Editorial cartoon about Jacob Smith's retaliation for Balangiga.PNG, One of the ''New York Journal''s most infamous cartoons, depicting

Mr. Hearst's Flagship Sank Like the Maine

by Stan Fischler for the ''

Database for the photographic morgue

at the

Information on the clippings morgue at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

* * {{Authority control Defunct newspapers published in New York City Newspapers established in 1937 Publications disestablished in 1966 1937 establishments in New York City 1966 disestablishments in New York (state) Hearst Communications publications William Randolph Hearst Daily newspapers published in New York City

Columnists and reporters

Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – ) was an American short story writer, journalist, poet, and American Civil War veteran. His book '' The Devil's Dictionary'' was named as one of "The 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature" by ...

, Benjamin De Casseres, Dorothy Kilgallen, O. O. McIntyre, and Westbrook Pegler. Kilgallen also wrote articles that appeared on the same days as her column on different pages, sometimes the front page. Regular ''Journal-American'' contributor Jimmy Cannon was one of the highest paid sports columnists in the United States. Society columnist Maury Henry Biddle Paul, who wrote under the pseudonym "Cholly Knickerbocker", became famous and coined the term "Café Society". John F. Kennedy contributed to the newspaper during a brief career he had as a journalist during the final months of World War II. Leonard Liebling

Leonard Liebling (February 7, 1874 – October 28, 1945) was an American music critic, writer, librettist, editor, pianist, and composer. He is best remembered as the long time editor-in-chief of the ''Musical Courier'' from 1911 to 1945.

Life a ...

served as the paper's music critic from 1923 to 1936.

Staff

Beginning in 1938,Max Kase

Max Kase (July 21, 1897 – March 20, 1974) was an American newspaper writer and editor. He worked for the Hearst newspapers from 1917 to 1966 and was the sports editor of the ''New York Journal-American'' from 1938 to 1966. In 1946, he was one of ...

(1898–1974) was the sports editor until the newspaper expired in 1966. The fashion editor was Robin Chandler Duke.

Jack O'Brian

John Dennis Patrick O'Brian (August 16, 1914 – November 5, 2000) was an entertainment journalist best known for his longtime role as a television critic for '' New York Journal American''.

Career

After the death of Dorothy Kilgallen, his ...

(1914–2000) was television critic for the ''Journal-American'' and exposed the 1958 quiz-show scandal that involved cheating on the popular television program ''Twenty-One

21 (twenty-one) is the natural number following 20 and preceding 22.

The current century is the 21st century AD, under the Gregorian calendar.

In mathematics

21 is:

* a composite number, its proper divisors being 1, 3 and 7, and a deficie ...

''. O'Brian was a supporter of Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

and his series of published attacks on CBS News and WCBS-TV reporter Don Hollenbeck, may have been a major factor in Hollenbeck's eventual suicide, referenced in the 1986 HBO film ''Murrow'' and the 2005 motion picture ''Good Night, and Good Luck

''Good Night, and Good Luck'' (stylized as ''good night, and good luck.'') is a 2005 historical drama film about American television news directed by George Clooney, with the movie starring David Strathairn, Patricia Clarkson, Jeff Daniels, ...

''.

Ford Frick (1894–1978) was a sportswriter for the ''American'' before becoming president of baseball's National League

The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the National League (NL), is the older of two leagues constituting Major League Baseball (MLB) in the United States and Canada, and the world's oldest extant professional team ...

(1934–1951), then commissioner of Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (AL) ...

(1951–1965). Frick was hired by Wilton S. Farnsworth, who was sports editor of the ''American'' from 1914–1937 until becoming a boxing promoter.

Bill Corum was a sportswriter for the ''Journal-American'' who also served nine years as president of the Churchill Downs race track. Frank Graham covered sports there from 1945 to 1965 and was inducted in the Baseball Hall of Fame

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is a history museum and hall of fame in Cooperstown, New York, operated by private interests. It serves as the central point of the history of baseball in the United States and displays baseball ...

, as were colleagues Charley Feeney and Sid Mercer

James Sidney Mercer (August 4, 1880 – June 19, 1945) was an American sports writer who covered mostly boxing and baseball in St. Louis and in New York City.

Biography

Mercer was born to James H. and Laura Ann Search Mercer on August 4, 1880, ...

.

Before becoming a news columnist elsewhere, Jimmy Breslin

James Earle Breslin (October 17, 1928 – March 19, 2017) was an American journalist and author. Until the time of his death, he wrote a column for the New York ''Daily News'' Sunday edition.''Current Biography 1942'', pp. 648–51: "Patterson, ...

was a ''Journal-American'' sportswriter in the early 1960s. He authored the book ''Can't Anybody Here Play This Game?

''Can't Anybody Here Play This Game?'' is a book written by journalist Jimmy Breslin, about the 1962 New York Mets.Sandomir, Richard (April 7, 2012)"Affectionate Scorn for '62 Mets" ''The New York Times''. Retrieved June 26, 2016. The book chroni ...

'' chronicling the season of the 1962 New York Mets.

Sheilah Graham (1904-1988) was a reporter for the ''Journal-American'' before gaining fame as a gossip columnist and as an acquaintance of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

William V. Finn, a staff photographer, died on the morning of June 25, 1958 while photographing the aftermath of a fiery collision between the tanker ''Empress Bay'' and cargo ship Nebraska in the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Que ...

. Finn was a past-president of the New York Press Photographers Association

The New York Press Photographers Association is an association of photojournalists who

work for news organizations in the print and electronic media based within a seventy-five mile radius of Manhattan. The organization was founded in 1913 and ha ...

and was the second of only two of the association's members to die in the line of duty.

Photographs

The newspaper was famous for publishing many photographs with the "Journal-American Photo" credit line as well as news photographs fromAssociated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. n ...

and other wire services

A news agency is an organization that gathers news reports and sells them to subscribing news organizations, such as newspapers, magazines and radio and television broadcasters. A news agency may also be referred to as a wire service, newswi ...

.

Decline

With one of the highest circulations in New York in the 1950s and 1960s, the ''Journal-American'' nevertheless had difficulties attracting advertising as its blue-collar reading base turned to television, a situation compounded by the fact that television news was affecting evening newspapers more than their morning counterparts. The domination of television news became evident starting with the four-day period of JFK's assassination, Jack Ruby's shooting ofLee Harvey Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald (October 18, 1939 – November 24, 1963) was a U.S. Marine veteran who assassinated John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, on November 22, 1963.

Oswald was placed in juvenile detention at the age of 12 ...

and both men's funerals. New York newspapers in general were in dire straits by then, following a devastating newspaper strike in late 1962 and early 1963.

''Journal-American'' editors, apparently sensing that psychotherapy and rock music were starting to enter the consciousness of both blue-collar and white-collar New Yorkers, enlisted Dr. Joyce Brothers to write front-page articles in February 1964 analyzing the Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the most influential band of all time and were integral to the developm ...

. While the Beatles were filming '' Help!'' in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the arc ...

, columnist Phyllis Battelle interviewed them for articles that ran on the ''Journal-American'' front page and in other Hearst papers, including the ''Los Angeles Herald Examiner

The ''Los Angeles Herald Examiner'' was a major Los Angeles daily newspaper, published in the afternoon from Monday to Friday and in the morning on Saturdays and Sundays. It was part of the Hearst syndicate. It was formed when the afternoon ' ...

'', for four consecutive days, from April 25 to 28, 1965.

During every visit that the Beatles made to New York in 1964 and 1965, including their appearances at Shea Stadium

Shea Stadium (), formally known as William A. Shea Municipal Stadium, was a multi-purpose stadium in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, Queens, New York City.

, various ''Journal-American'' columnists and reporters devoted a lot of space to them.

Throughout 1964 and 1965, Dorothy Kilgallen's ''Voice of Broadway'' column, which ran Sunday through Friday, often reported short news items about trendy young rock groups and performers such as The Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones are an English rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for six decades, they are one of the most popular and enduring bands of the rock era. In the early 1960s, the Rolling Stones pioneered the gritty, rhythmically d ...

, The Animals

The Animals (also billed as Eric Burdon and the Animals) are an English rock band, formed in Newcastle upon Tyne in the early 1960s. The band moved to London upon finding fame in 1964. The Animals were known for their gritty, bluesy sound an ...

, The Dave Clark Five, Mary Wells

Mary Esther Wells (May 13, 1943 – July 26, 1992) was an American singer, who helped to define the emerging sound of Motown in the early 1960s.

Along with The Supremes, The Miracles, The Temptations, Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, and ...

and Sam Cooke. The newspaper was trying to keep up with the many mid-1960s changes in popular music and its interracial fan bases.

It published enlarged photographs of civil rights demonstrations, Dorothy Kilgallen's skepticism about the Warren Commission report as well as many reporters' stories on the increasing crime rate in New York's five boroughs.

Most of the front page of the Sunday edition of January 12, 1964 ran stories that were relevant to the previous day's announcement by U.S. Surgeon General Luther Terry that "a blue ribbon committee of scientists and doctors," in the words of reporter Jack Pickering, had concluded that cigarette smoking was dangerous.

The ''Journal-American''s feel of the pulse of the changing times of the mid-1960s hid the trouble that was going on behind the scenes at the paper, which was unknown to many New Yorkers until after it had ceased publication.

Besides trouble with advertisers, another major factor that led to the ''Journal-American''s demise was a power struggle between Hearst CEO

It published enlarged photographs of civil rights demonstrations, Dorothy Kilgallen's skepticism about the Warren Commission report as well as many reporters' stories on the increasing crime rate in New York's five boroughs.

Most of the front page of the Sunday edition of January 12, 1964 ran stories that were relevant to the previous day's announcement by U.S. Surgeon General Luther Terry that "a blue ribbon committee of scientists and doctors," in the words of reporter Jack Pickering, had concluded that cigarette smoking was dangerous.

The ''Journal-American''s feel of the pulse of the changing times of the mid-1960s hid the trouble that was going on behind the scenes at the paper, which was unknown to many New Yorkers until after it had ceased publication.

Besides trouble with advertisers, another major factor that led to the ''Journal-American''s demise was a power struggle between Hearst CEO Richard E. Berlin

Richard E. Berlin (1894-1986) was the president and chief executive officer of the Hearst Foundation.

Work

In his early career Berlin directed advertising for ''The Smart Set'' and ''McClure's'' magazines. In 1919 he joined the Hearst Corporatio ...

and two of Hearst's sons, who had trouble carrying on the father's legacy after his 1951 death. William Randolph Hearst Jr. claimed in 1991 that Berlin, who died in 1986, had suffered from Alzheimer's disease starting in the mid-1960s and that caused him to shut down several Hearst newspapers without just cause.

Merger

The ''Journal-American'' ceased publishing in April 1966, officially the victim of a general decline in the revenue of afternoon newspapers. While participating in a lock-out in 1965 after ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' and ''New York Daily News

The New York ''Daily News'', officially titled the ''Daily News'', is an American newspaper based in Jersey City, NJ. It was founded in 1919 by Joseph Medill Patterson as the ''Illustrated Daily News''. It was the first U.S. daily printed in Ta ...

'' had been struck by a union, the ''Journal-American'' agreed it would merge (the following year) with its evening rival, the '' New York World-Telegram and Sun'', and the morning '' New York Herald-Tribune''. According to its publisher, publication of the combined '' New York World Journal Tribune'' was delayed for several months after the April 1966 expiration of its three components because of difficulty reaching an agreement with manual laborers who were needed to operate the press. The ''World Journal Tribune'' commenced publication on September 12, 1966, but folded eight months later.

Archives

Other afternoon and evening newspapers that expired following the rise of network news in the 1960s donated their clipping files and many darkroom prints of published photographs to libraries. The Hearst Corporation decided to donate the "basic back-copy morgue" of the ''Journal-American'', according to a book about Dorothy Kilgallen, plus darkroom prints and negatives, according to other sources, to theUniversity of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

.Israel, Lee. ''Kilgallen''. New York: Delacorte Press, 1979. Office memorandums and letters from politicians and other notables were shredded in 1966. The newspaper is preserved on microfilm in New York City, Washington, DC, and Austin, Texas. Interlibrary loans make the microfilm accessible to people who cannot travel to those cities.

The ''Journal-American'' photo morgue is housed at the Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pu ...

at the University of Texas at Austin. The photographic morgue consists of approximately two million prints and one million negatives created for publication, with the bulk of the collection covering the years from 1937 to the paper's demise in 1966. The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, also at the University of Texas at Austin, has the ''Journal-American'' morgue of clippings, numbering approximately nine million. Because they are not digitized and because employees of the facility have limited time for communicating by email with people who are searching for very old articles, the people who are searching should know the date of a ''Journal-American'' article to locate it on microfilm.

Gallery

Two scoops of ''The Journal'' was the printing of the confession of Herman Webster Mudghett aka Dr. H. H. Holmes a serial killer of Chicago in 1896 and the Jacob Smith order of 1902Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War or Filipino–American War ( es, Guerra filipina-estadounidense, tl, Digmaang Pilipino–Amerikano), previously referred to as the Philippine Insurrection or the Tagalog Insurgency by the United States, was an arm ...

General Jacob H. Smith's order "Kill Everyone over Ten," from the front page on May 5, 1902.

References

External links

Mr. Hearst's Flagship Sank Like the Maine

by Stan Fischler for the ''

Village Voice

''The Village Voice'' is an American news and culture paper, known for being the country's first alternative newspaper, alternative newsweekly. Founded in 1955 by Dan Wolf (publisher), Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher, John Wilcock, and Norman Mailer, th ...

'' April 28, 1966

Database for the photographic morgue

at the

Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pu ...

at the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

Information on the clippings morgue at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

* * {{Authority control Defunct newspapers published in New York City Newspapers established in 1937 Publications disestablished in 1966 1937 establishments in New York City 1966 disestablishments in New York (state) Hearst Communications publications William Randolph Hearst Daily newspapers published in New York City