The New Order (german: Neuordnung) of Europe was the political order which

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

wanted to impose on the conquered areas under its dominion. The establishment of the german: label=none, Neuordnung had already begun long before the start of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, but was publicly proclaimed by

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

in 1941: "The year 1941 will be, I am convinced, the historical year of a great European New Order!"

Among other things, it entailed the creation of a

pan-German

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

racial state, structured according to

Nazi ideology

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

, to ensure the existence of a perceived

Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

-

Nordic master race

The master race (german: Herrenrasse) is a Pseudoscience, pseudoscientific concept in Nazism, Nazi ideology in which the putative "Aryan race" is deemed the pinnacle of Race (classification of human beings), human racial hierarchy. Members wer ...

, consolidate a massive territorial expansion into

Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe is a term encompassing the countries in the Baltics, Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Southeast Europe (mostly the Balkans), usually meaning former communist states from the Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact in Europe. ...

through

colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

by German settlers, achieve the

physical annihilation of

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

,

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

(especially

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

and

Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

),

Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

*Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

("gypsies"), and others considered to be "

unworthy of life", as well as the

extermination, expulsion or enslavement of most of the Slavic peoples and others regarded as "

racially inferior".

Nazi Germany's desire for aggressive territorial

expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

was one of the most important

causes of World War II

The causes of World War II, a global war from 1939 to 1945 that was the deadliest conflict in human history, have been given considerable attention by historians from many countries who studied and understood them. The immediate precipitating ...

.

Historians

are still divided as to its ultimate goals, some believing that it was to be limited to Nazi German domination of Europe, while others maintain that it was a springboard for eventual world conquest and the establishment of a

world government

World government is the concept of a single political authority with jurisdiction over all humanity. It is conceived in a variety of forms, from tyrannical to democratic, which reflects its wide array of proponents and detractors.

A world gove ...

under German control.

Origin of the term

The term ''Neuordnung'' originally had a more limited meaning than it did later. It is typically translated as "New Order", but a more correct translation would be more akin to "reorganization". When it was used in Germany during the Third Reich era, it referred specifically to the desire of the Nazis to redraw the

state borders within

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, thereby transforming the existing geopolitical structures. In the same sense, it has also been used, now and in the past, to denote similar re-orderings of the international political order such as those following the

Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pea ...

in 1648, the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815, and the

Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

victory in 1945. The complete phrase used by the Nazi establishment was actually ''die Neuordnung Europas'' (the New Order of Europe), for which ''Neuordnung'' was merely a shorthand.

According to the

Nazi government

The government of Nazi Germany was totalitarian, run by the Nazi Party in Germany according to the Führerprinzip through the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nazi Germany began with the fact that the Enabling Act was enacted to give Hitler's gover ...

, that principle was pursued by Germany to secure a fair rearrangement of territory for the common benefit of

a new, economically integrated Europe, which in Nazi terminology meant the continent of Europe with the exception of the "

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

tic"

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. Nazi racial views regarded the "

Judeo-Bolshevist" Soviet state as both a criminal institution which needed to be destroyed, and as a barbarian place lacking any culture that would give it a "European" character. Therefore, ''Neuordnung'' was rarely used in reference to Soviet Russia, because the Nazis believed it did not feature any elements that could be re-organized along National Socialist lines.

The objective was to ensure a state of total post-war continental

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

for

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

.

[Haffner, Sebastian (1979). ''The Meaning of Hitler''. Macmillan Publishing Company Inc., p. 100]

/ref> That was to be achieved by the expansionism, expansion of the territorial base of the German state itself, combined with the political and economic subjugation of the rest of Europe to Germany. Eventual extensions of the project to areas beyond Europe, as well as on an ultimately global scale, were anticipated for the future period in which Germany would have secured unchallenged control over her own continent, but ''Neuordnung'' did not carry that extra-European meaning at the time.

Through its wide use in Nazi propaganda

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation o ...

, the phrase quickly gained coinage in Western media. In English-language academic circles especially, it eventually carried a much more inclusive definition, and was increasingly used to refer to the foreign and domestic policies, and the war aims, of the Nazi state, and its dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

ial leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

. Therefore, the phrase had approximately the same connotations as the term '' co-prosperity sphere'' did in Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

circles, in reference to their planned imperial domain. Nowadays, it is generally used to refer to all the post-war plans and policies, both in and outside of Europe, that the Nazis expected to implement after the anticipated victory of Germany and the other Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Ideological background

Racialist doctrine

The Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

claimed to scientifically measure a strict hierarchy of human race

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

. The "master race

The master race (german: Herrenrasse) is a Pseudoscience, pseudoscientific concept in Nazism, Nazi ideology in which the putative "Aryan race" is deemed the pinnacle of Race (classification of human beings), human racial hierarchy. Members wer ...

" was said to comprise the purest stock of the Aryan race

The Aryan race is an obsolete historical race concept that emerged in the late-19th century to describe people of Proto-Indo-European heritage as a racial grouping. The terminology derives from the historical usage of Aryan, used by modern I ...

, which was narrowly defined by the Nazis as being identical with the Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming th ...

, followed by other sub-Aryan races.[Hitler, Adolf '']Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'' The Nazis said that because Western civilization

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

, created and maintained mostly by Nordics, was obviously superior to other civilizations, the "Nordic" peoples were superior to all other races and were entitled to dominate the world, a concept known as Nordicism

Nordicism is an ideology of racism which views the historical race concept of the "Nordic race" as an endangered and superior racial group. Some notable and seminal Nordicist works include Madison Grant's book ''The Passing of the Great Race'' ...

.

Geopolitical strategy

Hitler's ideas about the eastward expansion that he promulgated in ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'' were greatly influenced during his 1924 imprisonment by his contact with his geopolitical

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

mentor

Mentorship is the influence, guidance, or direction given by a mentor. A mentor is someone who teaches or gives help and advice to a less experienced and often younger person. In an organizational setting, a mentor influences the personal and p ...

Karl Haushofer

Karl Ernst Haushofer (27 August 1869 – 10 March 1946) was a German general, professor, geographer, and politician. Through his student Rudolf Hess, Haushofer's conception of Geopolitik influenced the development of Adolf Hitler's expansio ...

. One of Haushofer's primary geopolitical concepts was the necessity for Germany to get control of the Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

n Heartland

Heartland or Heartlands may refer to:

Businesses and organisations

* Heartland Bank, a New Zealand-based financial institution

* Heartland Inn, a chain of hotels based in Iowa, United States

* Heartland Alliance, an anti-poverty organization i ...

in order for it to attain eventual world domination.

Anticipated territorial extent of Nazi imperialism

In a subsequently published speech given at Erlangen University

Erlangen (; East Franconian: ''Erlang'', Bavarian: ''Erlanga'') is a Middle Franconian city in Bavaria, Germany. It is the seat of the administrative district Erlangen-Höchstadt (former administrative district Erlangen), and with 116,062 inhabi ...

in November 1930, Hitler explained to his audience that no other people had more of a right to fight for and attain "control" of the globe (''Weltherrschaft'', i.e. "world leadership", "world rule") than the Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

. He realized that an extremely ambitious goal could never be achieved without significant military effort. Hitler had alluded to future German world dominance even earlier in his political career. In a letter written by Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

to Walter Hewel

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 1 ...

in 1927, Hess paraphrases Hitler's vision: "World peace

World peace, or peace on Earth, is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Planet Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would ...

is certainly an ideal worth striving for; in Hitler's opinion it will be realizable only when one power

''The Wheel of Time'' is a series of high fantasy novels by American author Robert Jordan, with Brandon Sanderson as a co-author for the final three novels. Originally planned as a six-book series, ''The Wheel of Time'' spans 14 volumes, in a ...

, the racially best one has attained complete and uncontested supremacy. That ower

Ower is a hamlet in the New Forest district of Hampshire, England. Its nearest towns are Totton – approximately to the southeast, and Romsey – around to the north-east.

Ower lies on the A36 road northwest of Totton. It lies mo ...

can then provide a sort of world police, seeing to it at the same time that the most valuable race is guaranteed the necessary living space. And if no other way is open to them, the lower races will have to restrict themselves accordingly".

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

discussed the territorial aspirations of Germany during his first Posen speech

The Posen speeches were two speeches made by Heinrich Himmler, the head of the Schutzstaffel, SS of Nazi Germany, on 4 and 6 October 1943 in the Poznań Town Hall, town hall of Posen (Poznań), in History of Poland (1939–1945)#German-occupied P ...

in 1943. He commented on the goals of the warring nations involved in the conflict and stated that Germany was fighting for new territories and a global power status:

Implementation in Europe

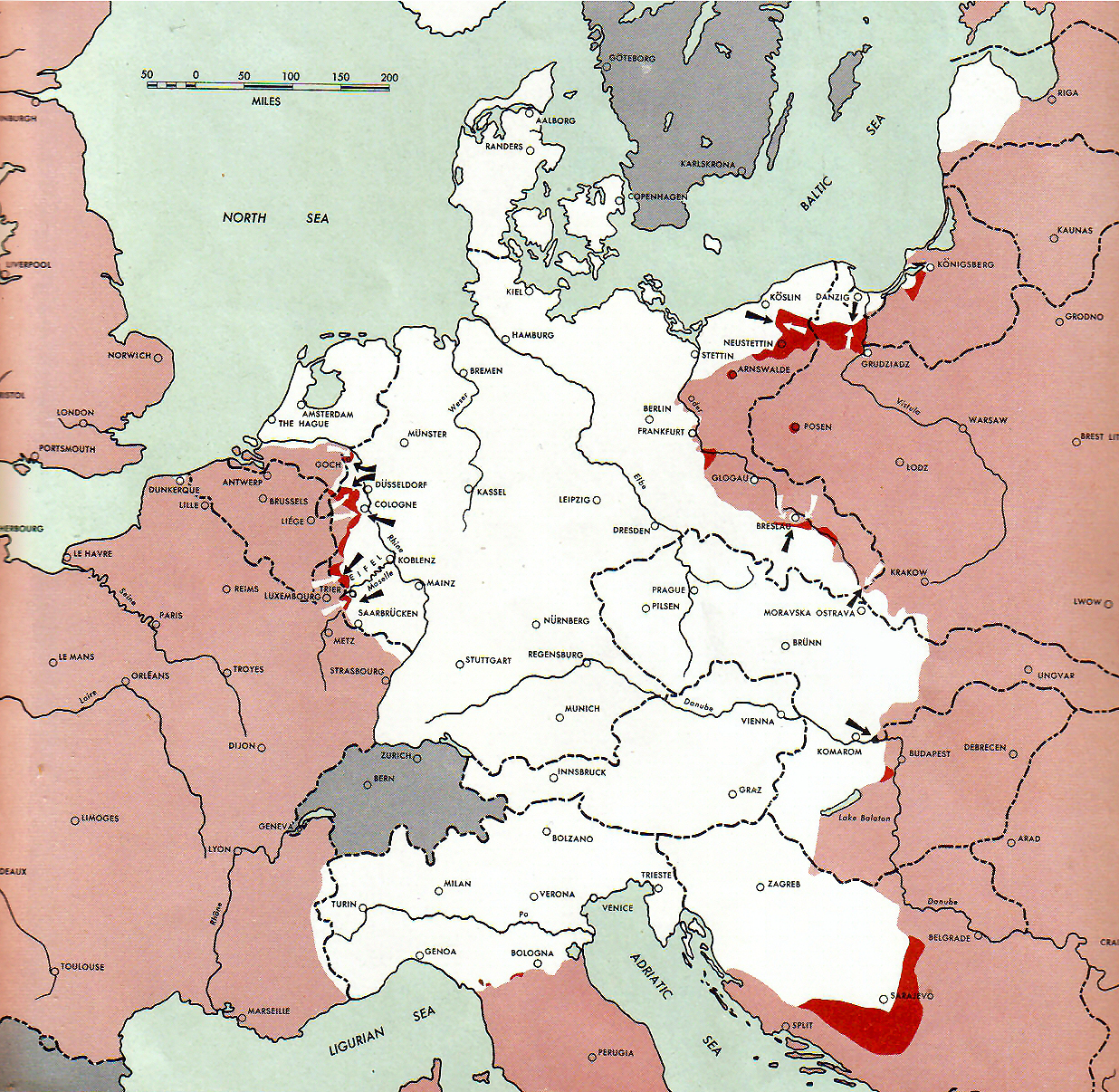

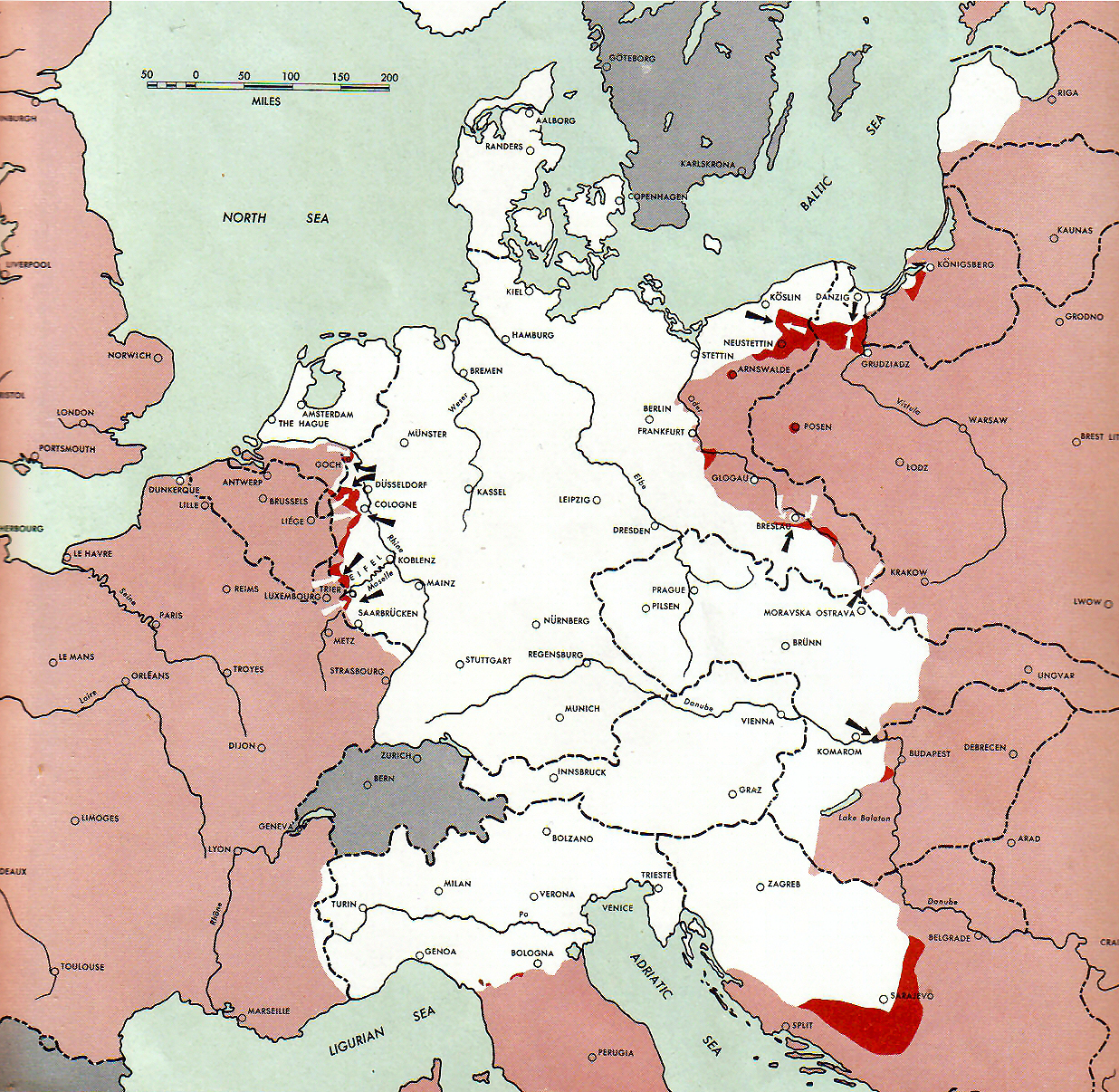

Military campaigns in Poland and Western Europe

The initial phase of the establishment of the New Order was:

* First, the signing of the German–Soviet non-aggression agreement on 23 August 1939 prior to the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

to secure the new eastern border with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, prevent the emergence of a two-front war

According to military terminology, a two-front war occurs when opposing forces encounter on two geographically separate fronts. The forces of two or more allied parties usually simultaneously engage an opponent in order to increase their chance ...

, and to circumvent a shortage of raw materials

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feedst ...

due to an expected British naval blockade

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It includ ...

.

* Second, the Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air su ...

attacks in northern and western Europe (Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung (german: Unternehmen Weserübung , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was Germany's assault on Denmark and Norway during the Second World War and the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 Ap ...

and the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

respectively) to neutralize opposition from the west. This resulted in the conquest of Denmark, Norway, Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

, Belgium, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, and France, all of which were under German rule by the early summer of 1940.

Had the British been defeated by Germany, the political re-ordering of Western Europe would have been accomplished. There was to be no post-war general peace conference

A peace conference is a diplomatic meeting where representatives of certain states, armies, or other warring parties converge to end hostilities and sign a peace treaty.

Significant international peace conferences in the past include the follo ...

in the manner of the one held in Paris after the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, merely bilateral negotiations between Germany and her defeated enemies.[Weinberg, ''A world at arms'' (2005), p. 175] All still existing international organization

An international organization or international organisation (see spelling differences), also known as an intergovernmental organization or an international institution, is a stable set of norms and rules meant to govern the behavior of states an ...

s such as the International Labour Organization

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is the first and o ...

were to be dismantled or replaced by German-controlled equivalents.

One of the primary German foreign policy aims throughout the 1930s had been to establish a military alliance with the United Kingdom, and despite anti-British policies having been adopted as this proved impossible, hope remained that the UK would in time yet become a reliable German ally.[Rich 1974, p. 396.] Hitler professed an admiration for the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

and preferred to see it preserved as a world power, mostly because its break-up

A relationship breakup, breakup, or break-up is the termination of a relationship. The act is commonly termed "dumping omeone in slang when it is initiated by one partner. The term is less likely to be applied to a married couple, where a brea ...

would benefit other countries far more than it would Germany, particularly the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

.Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

after its defeat by the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

in 1866, after which Austria was formally excluded from German affairs but would prove to become a loyal ally of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in the pre-World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

power alignments in Europe. It was hoped that a defeated Britain would fulfill a similar role, being excluded from continental affairs, but maintaining its Empire and becoming an allied seafaring partner of the Germans.William L. Shirer

William Lawrence Shirer (; February 23, 1904 – December 28, 1993) was an American journalist and war correspondent. He wrote ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'', a history of Nazi Germany that has been read by many and cited in scholarly w ...

, however, claims that the British male population between 17 and 45 would have been forcibly transferred to the continent to be used as industrial slave labour

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, although possibly with better treatment than similar forced labor from Eastern Europe.[Shirer, p. 949] The remaining population would have been terrorized, including civilian hostages being taken and the death penalty immediately imposed for even the most trivial acts of resistance, with the UK being plundered for anything of financial, military, industrial or cultural value.[Shirer, p. 782 & 943]

After the war, Otto Bräutigam

Otto Bräutigam (14 May 1895 – 30 April 1992) was a German diplomat and lawyer who worked for the ''Auswärtiges Amt'' (German Foreign Office) and for the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, which was led by Alfred Rosenber ...

of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories

The Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (german: Reichsministerium für die besetzten Ostgebiete (RMfdbO) or ''Ostministerium'', ) was created by Adolf Hitler on 17 July 1941 and headed by the Nazi theoretical expert, the Baltic ...

claimed in his book that in February 1943 he had the opportunity to read a personal report by Wagner regarding a discussion with Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, in which Himmler had expressed the intention to exterminate about 80% of the populations of France and England by special forces

Special forces and special operations forces (SOF) are military units trained to conduct special operations. NATO has defined special operations as "military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, selected, trained and equip ...

of the SD after the German victory.

By annexing large territories in northeastern France, Hitler hoped to marginalize the country to prevent any further continental challenges to Germany's hegemony.Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and Italy) were to be eventually brought into a state of total German dependency and control.

Establishment of a Greater Germanic Reich

One of the most elaborate Nazi projects initiated in the newly conquered territories during this period of the war was the planned establishment of a "Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation" (''Großgermanisches Reich Deutscher Nation''). This future empire was to consist of, in addition to Greater Germany, virtually all of historically Germanic Europe (except

One of the most elaborate Nazi projects initiated in the newly conquered territories during this period of the war was the planned establishment of a "Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation" (''Großgermanisches Reich Deutscher Nation''). This future empire was to consist of, in addition to Greater Germany, virtually all of historically Germanic Europe (except Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

), whose inhabitants the Nazis believed to be "Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

" in nature. The consolidation of these countries as mere provinces of the Third Reich, in the same manner in which Austria was reduced to the "Ostmark

Ostmark is a German term meaning either Eastern march when applied to territories or Eastern Mark when applied to currencies.

Ostmark may refer to:

*the medieval March of Austria and its predecessors ''Bavarian Eastern March'' and ''March of Pann ...

", was to be carried out through a rapidly enforced process of ''Gleichschaltung

The Nazi term () or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied b ...

'' (synchronization). The ultimate intent of this was to eradicate all traces of national rather than racial

A race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 1500s, when it was used to refer to groups of variou ...

consciousness, although their native languages were to remain in existence.

Establishment of German domination in Southeastern Europe

Immediately prior to Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, five countries, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

and Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

were already client states

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

of Nazi Germany. Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

was under direct German military occupation and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

was under the occupation of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

had been annexed by Italy. Greece was under direct German-Italian military occupation because of the growing resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objective ...

. Although technically in the Italian sphere of influence, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

was, in reality, a condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

puppet state of the two Axis powers, with Italy controlling the southwestern half, and Germany the northeastern half. Hitler observed that permanent German bases might be established in Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

(possibly to be renamed to '' Prinz-Eugen-Stadt'') and Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

.

Conquest of Lebensraum in Eastern Europe

Adolf Hitler in ''

Adolf Hitler in ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'' argued in the chapter "Eastern Orientation or Eastern Policy" that the Germans needed ''Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imperi ...

'' in the East and described it as a "historic destiny" which would properly nurture the future generations of Germans. Hitler believed that "the organization of a Russian state formation was not the result of the political abilities of the Slavs in Russia, but only a wonderful example of the state-forming efficacity of the German element in an inferior race." Hitler spoke on 3 February 1933 to the staff of the army and declared that Germany's problems could be solved by "the conquest of new living space in the east and its ruthless Germanization". His earlier invasions of Czechoslovakia and Poland can be directly connected to his desire for Lebensraum in ''Mein Kampf''.

Implementation of the long-term plan for the New Order was begun on June 22, 1941 with Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

, the invasion of the USSR. The goal of the campaign was not merely the destruction of the Soviet regime—which the Nazis considered illegitimate and criminal—but also the racial reorganization of European Russia

European Russia (russian: Европейская Россия, russian: европейская часть России, label=none) is the western and most populated part of Russia. It is geographically situated in Europe, as opposed to the cou ...

, outlined for the Nazi elite in the Generalplan Ost

The ''Generalplan Ost'' (; en, Master Plan for the East), abbreviated GPO, was the Nazi German government's plan for the genocide and ethnic cleansing on a vast scale, and colonization of Central and Eastern Europe by Germans. It was to be un ...

("General Plan for the East"). Nazi party philosopher Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

(who, incidentally, protested against the inhumane policy shown toward the Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

) was the '' Minister for the Eastern Territories'', the person nominally in charge of the project, and Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, head of the SS, was assigned to implement the General Plan for the East which detailed the enslavement, expulsion, and extermination

Extermination or exterminate may refer to:

* Pest control, elimination of insects or vermin

* Genocide, extermination—in whole or in part—of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group

* Homicide or murder in general

* "Exterminate!", t ...

of the Baltic peoples and Slavic peoples.

Furthermore, Hitler hoped to turn Germany into a total blockade-proof autarky

Autarky is the characteristic of self-sufficiency, usually applied to societies, communities, states, and their economic systems.

Autarky as an ideal or method has been embraced by a wide range of political ideologies and movements, especially ...

by exploiting the vast resources lying in Soviet territories: Ukraine was to provide grain, vegetable oil, fodder, iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the fo ...

, nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow to ...

, manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy use ...

, coal, molybdenum

Molybdenum is a chemical element with the symbol Mo and atomic number 42 which is located in period 5 and group 6. The name is from Neo-Latin ''molybdaenum'', which is based on Ancient Greek ', meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lea ...

; Crimea natural rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds. Thailand, Malaysia, and ...

, citrus fruit

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the rue family, Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as oranges, lemons, grapefruits, pomelos, and limes. The genus ''Citrus'' is native to So ...

and cotton; the Black Sea fish, and the Caucasus crude oil.

By 1942 the quasi-colonial regimes called the ''General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

'' in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

, the ''Reichskommissariat Ostland

The Reichskommissariat Ostland (RKO) was established by Nazi Germany in 1941 during World War II. It became the civilian occupation regime in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the western part of Byelorussian SSR. German planning documents initia ...

'' in the Baltic states

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

and Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

, and the ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine

During World War II, (abbreviated as RKU) was the civilian occupation regime () of much of Nazi German-occupied Ukraine (which included adjacent areas of modern-day Belarus and pre-war Second Polish Republic). It was governed by the Reich Min ...

'' in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

had been established. Two more administrative divisions were envisaged: a ''Reichskommissariat Moskowien

Reichskommissariat Moskowien (RKM; russian: Рейхскомиссариат Московия, Reykhskomissariat Moskoviya , Reich Commissariat of Muscovy) was the civilian occupation-regime that Nazi Germany intended to establish in central an ...

'' that would include the Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

metropolitan area and vast tracts of European Russia

European Russia (russian: Европейская Россия, russian: европейская часть России, label=none) is the western and most populated part of Russia. It is geographically situated in Europe, as opposed to the cou ...

, and a ''Reichskommissariat Kaukasus

The Reichskommissariat Kaukasien (russian: Рейхскомиссариат Кавказ), also spelled as Kaukasus, was the theoretical political division and planned civilian occupation regime of Germany in the occupied territories of the Cauc ...

'' in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

. This policy was accompanied by the annihilation

In particle physics, annihilation is the process that occurs when a subatomic particle collides with its respective antiparticle to produce other particles, such as an electron colliding with a positron to produce two photons. The total energy a ...

of the entire Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

population (the Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

), as well as the enslavement of their Slavic inhabitants, who it was planned, would be made slave laborers on the estates be granted to SS soldiers after the conquest of European Russia. Each of these SS "soldier peasants" was expected to father at least seven children.

German women were encouraged to have as many children as possible to populate the newly acquired Eastern territories. To encourage this fertility policy, the Lebensborn

Lebensborn e.V. (literally: "Fount of Life") was an SS-initiated, state-supported, registered association in Nazi Germany with the stated goal of increasing the number of children born who met the Nazi standards of "racially pure" and "healt ...

program was expanded and the state decoration known as the Gold Honor Cross of the German Mother was instituted, which was awarded to German women who bore at least eight children for the Third Reich. There was also an effort by Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

and Himmler to introduce new marriage legislation to facilitate population growth, which would have allowed decorated war heroes to marry an additional wife.Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

was not merely the destruction of the Bolshevik regime, but the "reversing of Russian dynamism" towards the east (Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

) and the freeing of the Reich of the "eastern nightmare for centuries to come" by eliminating the Russian state, regardless of its political ideology. The continued existence of Russia as a potential instigator of Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had ruled ...

and its suggestive power over other Slavic peoples in the fight between "Germandom" and "Slavism" was seen as a major threat.Vyatichs

The Vyatichs or more properly Vyatichi or Viatichi (russian: вя́тичи) were a native tribe of Early East Slavs who inhabited regions around the Oka, Moskva and Don rivers.

The Vyatichi had for a long time no princes, but the social struct ...

and Severians

The Severians or Severyans or Siverians ( be, Севяране; bg, Севери; russian: Северяне; uk, Сiверяни, translit=Siveriany) were a tribe or tribal confederation of early East Slavs occupying areas to the east of the mi ...

.White Ruthenia

White Ruthenia ( cu, Бѣла Роусь, Bela Rous'; be, Белая Русь, Biełaja Ruś; pl, Ruś Biała; russian: Белая Русь, Belaya Rus'; ukr, Біла Русь, Bila Rus') alternatively known as Russia Alba, White Rus' or W ...

, and in particular the Ukraine ("in its present extent") he deemed to be dangerously large.Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

had already advocated for such a general policy towards Eastern Europe in 1940.[(German) Reinhard Kühnl (1978). ''Der deutsche Faschismus in Quellen und Dokumenten'', 3rd Edition, p. 328. ]

Einige Gedanken über die Behandlung der Fremdvölkischen im Osten

'. Köln. A top-secret memorandum in 1940 from Himmler entitled "Thoughts on the Treatment of Alien Peoples in the East" expressed that the Germans must splinter as many ethnic splinter groups in German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

as possible, including Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian. The majority ...

, "White Russians" (Belarusians

, native_name_lang = be

, pop = 9.5–10 million

, image =

, caption =

, popplace = 7.99 million

, region1 =

, pop1 = 600,000–768,000

, region2 =

, pop2 ...

), Gorals

The Gorals ( pl, Górale; Goral dialect: ''Górole''; sk, Gorali; Cieszyn Silesia dialect, Cieszyn Silesian: ''Gorole''), also known as the Highlanders (in Poland as the Polish Highlanders) are an indigenous ethnographic or ethnic group primar ...

(see ''Goralenvolk

''Goralenvolk'' was a geopolitical term invented by the German Nazis in World War II in reference to the Goral highlander population of Podhale region in the south of Poland near the Slovak border. The Germans postulated a separate nation ...

''), Lemkos

Lemkos ( rue, Лeмкы, translit= Lemkŷ; pl, Łemkowie; uk, Лемки, translit=Lemky) are an ethnic group inhabiting the Lemko Region ( rue, Лемковина, translit=Lemkovyna; uk, Лемківщина, translit=Lemkivshchyna) of Car ...

, and Kashubians

The Kashubians ( csb, Kaszëbi; pl, Kaszubi; german: Kaschuben), also known as Cassubians or Kashubs, are a Lechitic ( West Slavic) ethnic group native to the historical region of Pomerania, including its eastern part called Pomerelia, in nor ...

and to find all "racially valuable" people and assimilate them in Germany.NSDAP Office of Racial Policy

The Office of Racial Policy was a department of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) that was founded for "unifying and supervising all indoctrination and propaganda work in the field of population and racial politics". It began in 1933 as the Nazi Party Offi ...

administration, in April 1942 details the splitting up of Reichskommissariat Moskowien into very loosely tied Generalkommissariats.[Gumkowski, Janusz; Leszczyński, Kazimierz (1961). ''Poland Under Nazi Occupation''. Polonia Pub. House]

/ref> The objective was to undermine the national cohesion of the Russians by promoting regional identification; a Russian from the Gorki Generalkommissariat was to feel that he was different from a Russian in the Tula Generalkommissariat.Cyrillic letters

, bg, кирилица , mk, кирилица , russian: кириллица , sr, ћирилица, uk, кирилиця

, fam1 = Egyptian hieroglyphs

, fam2 = Proto-Sinaitic

, fam3 = Phoenician

, fam4 = G ...

with the German alphabet

German orthography is the orthography used in writing the German language, which is largely phonemic. However, it shows many instances of spellings that are historic or analogous to other spellings rather than phonemic. The pronunciation of alm ...

.Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Ernst Kaltenbrunner (4 October 190316 October 1946) was a high-ranking Austrian SS official during the Nazi era and a major perpetrator of the Holocaust. After the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, and a brief period under Heinrich ...

, the head of the RSHA

The Reich Security Main Office (german: Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and ''Reichsführer-SS'', the head of the Nazi ...

, to begin the exporting of the faith of the Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

to the occupied east.[Longerich, P. (2008), ''Heinrich Himmler'', p. 267, ] Himmler considered the Jehovah's Witnesses to be frugal, hard-working, honest and fanatic in their pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

, and he believed that these traits were extremely desirable for the suppressed nations in the eastPeter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

and its follow-ups until the revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

.Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

and the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia or Tsardom of Rus' also externally referenced as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of Tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter I i ...

) was to be called the "Muscovite state", while post-1917 Russia was not to be referred to as an empire or a state at all; the preferred terms for this period were "bolshevik chaos" or "communist elements".Little Russia

Little Russia (russian: Малороссия/Малая Россия, Malaya Rossiya/Malorossiya; uk, Малоросія/Мала Росія, Malorosiia/Mala Rosiia), also known in English as Malorussia, Little Rus' (russian: Малая Ру� ...

'' (Ukraine), ''White Russia'' (Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

/White Ruthenia

White Ruthenia ( cu, Бѣла Роусь, Bela Rous'; be, Белая Русь, Biełaja Ruś; pl, Ruś Biała; russian: Белая Русь, Belaya Rus'; ukr, Біла Русь, Bila Rus') alternatively known as Russia Alba, White Rus' or W ...

), ''Russian Sea'' (for the Black Sea), and ''Russian Asia'' (for Siberia and Central Asia) were to be absolutely avoided as terminology of the "Muscovite imperialism".Tatars

The Tatars ()[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different " was described as a pejorative Russian term for the Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the List of rivers of Europe#Rivers of Europe by length, longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Cas ...

, Crimean

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, and Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

which was preferably to be avoided, and respectively replaced with the concepts " Idel (Volga)-Uralian", "Crimean Turks", and Azerbaijanis

Azerbaijanis (; az, Azərbaycanlılar, ), Azeris ( az, Azərilər, ), or Azerbaijani Turks ( az, Azərbaycan Türkləri, ) are a Turkic people living mainly in northwestern Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. They are the second-most numer ...

.

Re-settlement efforts

By 1942, Hitler's empire encompassed much of Europe, but the territories annexed lacked population desired by the Nazis.

By 1942, Hitler's empire encompassed much of Europe, but the territories annexed lacked population desired by the Nazis.Reichskommissar

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official gubernatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Germa ...

für die Festigung deutschen Volkstums'') (RKFDV

The Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood (german: Reichskommissar für die Festigung deutschen Volkstums, RKF, RKFDV) was an office in Nazi Germany, which was held by ''Reichsführer-SS'' Heinrich Himmler.

Adolf Hitler in ...

) (see also '' Hauptamt Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle'', VoMi)Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of '' volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

'') living abroad to occupied Poland

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October 2 ...

.[Kroener et al. (2003), p. 251] The great majority of Himmler's ''Volksdeutsche'' were acquired from the Soviet sphere of interest under the German–Soviet "population exchange" treaty. At the end of 1942 a total of 629,000 ''Volksdeutsche'' had been re-settled, and preparations for the transfer of 393,000 others were underway.

At the end of 1942 a total of 629,000 ''Volksdeutsche'' had been re-settled, and preparations for the transfer of 393,000 others were underway.Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

, Banat

Banat (, ; hu, Bánság; sr, Банат, Banat) is a geographical and historical region that straddles Central and Eastern Europe and which is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of T ...

, France, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

.

Spain and Portugal

Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

contemplated joining the war on the German side. The Spanish Falangists made numerous border claims. Franco claimed French Basque departments, Catalan-speaking Roussillon

Roussillon ( , , ; ca, Rosselló ; oc, Rosselhon ) is a historical province of France that largely corresponded to the County of Roussillon and part of the County of Cerdagne of the former Principality of Catalonia. It is part of the reg ...

, Cerdagne

Cerdanya () or often La Cerdanya ( la, Ceretani or ''Ceritania''; french: Cerdagne; es, Cerdaña), is a natural comarca and historical region of the eastern Pyrenees divided between France and Spain. Historically it was one of the counties ...

and Andorra

, image_flag = Flag of Andorra.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Andorra.svg

, symbol_type = Coat of arms

, national_motto = la, Virtus Unita Fortior, label=none (Latin)"United virtue is stro ...

. Spain also wanted to reclaim Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

from the United Kingdom because of the symbolic and strategic value. Franco also called for the reunification of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

as a Spanish protectorate, the annexation of the Oran district from French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

and large-scale expansion of Spanish Guinea

Spanish Guinea (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Guinea Española'') was a set of Insular Region (Equatorial Guinea), insular and Río Muni, continental territories controlled by Spain from 1778 in the Gulf of Guinea and on the Bight of Bonny, in ...

. This last project was especially unfeasible because it overlapped German territorial ambition to reclaim German Cameroon

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern ...

and Spain would most likely be forced to give up Guinea entirely. Spain also sought federation with Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

on common cultural and historical grounds (such as the Iberian Union

pt, União Ibérica

, conventional_long_name =Iberian Union

, common_name =

, year_start = 1580

, date_start = 25 August

, life_span = 1580–1640

, event_start = War of the Portuguese Succession

, event_end = Portuguese Restoration War

, ...

).

After the Spanish refusal to join the war, Spain and Portugal were expected to be invaded and become puppet states. They were to turn over coastal cities and islands in the Atlantic to Germany as part of the Atlantic Wall

The Atlantic Wall (german: link=no, Atlantikwall) was an extensive system of coastal defences and fortifications built by Nazi Germany between 1942 and 1944 along the coast of continental Europe and Scandinavia as a defence against an anticip ...

and to serve as German naval facilities. Portugal was to cede Portuguese Mozambique

Portuguese Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique) or Portuguese East Africa (''África Oriental Portuguesa'') were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese Empire, Portuguese colony. Portuguese Moz ...

and Portuguese Angola

Portuguese Angola refers to Angola during the historic period when it was a territory under Portuguese rule in southwestern Africa. In the same context, it was known until 1951 as Portuguese West Africa (officially the State of West Africa).

I ...

as part of the intended Mittelafrika

''Mittelafrika'' (, "Middle Africa") is the name created for a geostrategic region in central and east Africa. Much like ''Mitteleuropa'', it articulated Germany's foreign policy aim, prior to the First World War, of bringing the region und ...

colonial project.

Plans for other parts of the world outside Europe

Plans for an African colonial domain

Hitler's geopolitical thoughts about

Hitler's geopolitical thoughts about Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

always occupied a secondary position to his expansionist aims in Europe itself. His public announcements prior to outbreak of the war that Germany's former colonies be returned to it served primarily as bargaining chips to further territorial goals in Europe itself. Africa was nevertheless expected to fall under German control in some way or another after Germany had first achieved supremacy over its own continent.[Weinberg 2005, p. 14.]

Hitler's overall intentions for the future organization of Africa divided the continent into three overall. The northern third was to be assigned to its Italian ally, while the central part would fall under German rule. The remaining southern sector would be controlled by a pro-Nazi Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from Free Burghers, predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: ...

state built on racial grounds.Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

had communicated with South African leaders thought to be sympathetic to the Nazi cause, informing them that Germany was to reclaim its former colony of German South-West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

, then a mandate of the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

.[Rich (1974), pp. 500-501.] South Africa was to be compensated by the territorial acquisitions of the British protectorates of Swaziland

Eswatini ( ; ss, eSwatini ), officially the Kingdom of Eswatini and formerly named Swaziland ( ; officially renamed in 2018), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Mozambique to its northeast and South Africa to its no ...

, Basutoland

Basutoland was a British Crown colony that existed from 1884 to 1966 in present-day Lesotho. Though the Basotho (then known as Basuto) and their territory had been under British control starting in 1868 (and ruled by Cape Colony from 1871), th ...

and Bechuanaland and the colony of Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kn ...

.Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

.

In 1940 the general staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

of the ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

'' (navy) produced a much more detailed plan accompanied by a map showing a proposed German colonial empire

A colonial empire is a collective of territories (often called colonies), either contiguous with the imperial center or located overseas, settled by the population of a certain state and governed by that state.

Before the expansion of early mode ...

delineated in blue (the traditional color used in German cartography to indicate the German sphere of influence as opposed to the red or pink that represented the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

) in sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

, extending from the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

to the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

. The proposed domain was supposed to fulfill the long-sought territorial German goal of ''Mittelafrika

''Mittelafrika'' (, "Middle Africa") is the name created for a geostrategic region in central and east Africa. Much like ''Mitteleuropa'', it articulated Germany's foreign policy aim, prior to the First World War, of bringing the region und ...

'', and even further beyond. It would provide a base from which Germany would achieve a pre-eminent position on the African continent just as the conquest of Eastern Europe was to achieve a similar status over the continent of Europe.

In contrast to territories that were to be acquired in Europe itself (specifically European Russia

European Russia (russian: Европейская Россия, russian: европейская часть России, label=none) is the western and most populated part of Russia. It is geographically situated in Europe, as opposed to the cou ...

), these areas were not envisaged as targets for extensive German population settlement. The establishment of a vast colonial empire was to serve primarily economic purposes, for it would provide Germany with most natural resources that it would not be able to find in its continental possessions, as well as an additional nearly unlimited supply of labor. Racialist policies would nevertheless be strictly enforced on all inhabitants (meaning segregation of Europeans and blacks and punishing of interracial relationships) to maintain "Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

" purity.

The area included all pre-1914 German colonial territories in Africa, as well as additional parts of the French, Belgian and British colonial holdings in Africa. These included the French and Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

s, Northern and Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kn ...

(the latter going perhaps to South Africa), Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate located in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasala ...

, southern Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =