Neoplesiosauria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Plesiosauria (;

Skeletal elements of plesiosaurs are among the first fossils of extinct reptiles recognised as such. In 1605,

Skeletal elements of plesiosaurs are among the first fossils of extinct reptiles recognised as such. In 1605,  During the eighteenth century, the number of English plesiosaur discoveries rapidly increased, although these were all of a more or less fragmentary nature. Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and

During the eighteenth century, the number of English plesiosaur discoveries rapidly increased, although these were all of a more or less fragmentary nature. Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and

In the early nineteenth century, plesiosaurs were still poorly known and their special build was not understood. No systematic distinction was made with

In the early nineteenth century, plesiosaurs were still poorly known and their special build was not understood. No systematic distinction was made with  Plesiosaurs became better known to the general public through two lavishly illustrated publications by the collector Thomas Hawkins: ''Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri'' of 1834 and ''The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons'' of 1840. Hawkins entertained a very idiosyncratic view of the animals, seeing them as monstrous creations of the devil, during a pre-Adamitic phase of history. Hawkins eventually sold his valuable and attractively restored specimens to the British Museum of Natural History.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the number of plesiosaur finds steadily increased, especially through discoveries in the sea cliffs of Lyme Regis. Sir Richard Owen alone named nearly a hundred new species. The majority of their descriptions were, however, based on isolated bones, without sufficient diagnosis to be able to distinguish them from the other species that had previously been described. Many of the new species described at this time have subsequently been invalidated. The genus ''Plesiosaurus'' is particularly problematic, as the majority of the new species were placed in it so that it became a

Plesiosaurs became better known to the general public through two lavishly illustrated publications by the collector Thomas Hawkins: ''Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri'' of 1834 and ''The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons'' of 1840. Hawkins entertained a very idiosyncratic view of the animals, seeing them as monstrous creations of the devil, during a pre-Adamitic phase of history. Hawkins eventually sold his valuable and attractively restored specimens to the British Museum of Natural History.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the number of plesiosaur finds steadily increased, especially through discoveries in the sea cliffs of Lyme Regis. Sir Richard Owen alone named nearly a hundred new species. The majority of their descriptions were, however, based on isolated bones, without sufficient diagnosis to be able to distinguish them from the other species that had previously been described. Many of the new species described at this time have subsequently been invalidated. The genus ''Plesiosaurus'' is particularly problematic, as the majority of the new species were placed in it so that it became a

In 1867, physician Theophilus Turner near Fort Wallace in

In 1867, physician Theophilus Turner near Fort Wallace in

The Plesiosauria have their origins within the

The Plesiosauria have their origins within the  From the earliest

From the earliest  The latest common ancestor of the Plesiosauria was probably a rather small short-necked form. During the earliest Jurassic, the subgroup with the most species was the Rhomaleosauridae, a possibly very basal split-off of species which were also short-necked. Plesiosaurs in this period were at most five metres (sixteen feet) long. By the Toarcian, about 180 million years ago, other groups, among them the Plesiosauridae, became more numerous and some species developed longer necks, resulting in total body lengths of up to .

In the middle of the Jurassic, very large

The latest common ancestor of the Plesiosauria was probably a rather small short-necked form. During the earliest Jurassic, the subgroup with the most species was the Rhomaleosauridae, a possibly very basal split-off of species which were also short-necked. Plesiosaurs in this period were at most five metres (sixteen feet) long. By the Toarcian, about 180 million years ago, other groups, among them the Plesiosauridae, became more numerous and some species developed longer necks, resulting in total body lengths of up to .

In the middle of the Jurassic, very large

The following cladogram follows an analysis by Benson & Druckenmiller (2014).

The following cladogram follows an analysis by Benson & Druckenmiller (2014).

In general, plesiosaurians varied in adult length from between to about . The group thus contained some of the largest marine

In general, plesiosaurians varied in adult length from between to about . The group thus contained some of the largest marine

While plesiosaurs varied little in the build of the trunk, and can be called "conservative" in this respect, there were major differences between the subgroups as regards the form of the neck and the skull. Plesiosaurs can be divided into two major morphological types that differ in head and neck size. "Plesiosauromorphs", such as Cryptoclididae, Elasmosauridae, and Plesiosauridae, had long necks and small heads. "Pliosauromorphs", such as the

While plesiosaurs varied little in the build of the trunk, and can be called "conservative" in this respect, there were major differences between the subgroups as regards the form of the neck and the skull. Plesiosaurs can be divided into two major morphological types that differ in head and neck size. "Plesiosauromorphs", such as Cryptoclididae, Elasmosauridae, and Plesiosauridae, had long necks and small heads. "Pliosauromorphs", such as the  The tooth form and number was very variable. Some forms had hundreds of needle-like teeth. Most species had larger conical teeth with a round or oval cross-section. Such teeth numbered four to six in the premaxilla and about fourteen to twenty-five in the maxilla; the number in the lower jaws roughly equalled that of the skull. The teeth were placed in tooth-sockets, had vertically wrinkled enamel and lacked a true cutting edge or ''wikt:carina, carina''. With some species, the front teeth were notably longer, to grab prey.

The tooth form and number was very variable. Some forms had hundreds of needle-like teeth. Most species had larger conical teeth with a round or oval cross-section. Such teeth numbered four to six in the premaxilla and about fourteen to twenty-five in the maxilla; the number in the lower jaws roughly equalled that of the skull. The teeth were placed in tooth-sockets, had vertically wrinkled enamel and lacked a true cutting edge or ''wikt:carina, carina''. With some species, the front teeth were notably longer, to grab prey.

Like all tetrapods with limbs, plesiosaurs must have had a certain gait, a coordinated movement pattern of the, in this case, flippers. Of all the possibilities, in practice attention has been largely directed to the question of whether the front pair and hind pair moved simultaneously, so that all four flippers were engaged at the same moment, or in an alternate pattern, each pair being employed in turn. Frey & Riess in 1991 proposed an alternate model, which would have had the advantage of a more continuous propulsion. In 2000, Theagarten Lingham-Soliar evaded the question by concluding that, like sea turtles, plesiosaurs only used the front pair for a powered stroke. The hind pair would have been merely used for steering. Lingham-Soliar deduced this from the form of the hip joint, which would have allowed for only a limited vertical movement. Furthermore, a separation of the propulsion and steering function would have facilitated the general coordination of the body and prevented a too extreme Pitch (aviation), pitch. He rejected Robinson's hypothesis that elastic energy was stored in the ribcage, considering the ribs too stiff for this.

The interpretation by Frey & Riess became the dominant one, but was challenged in 2004 by Sanders, who showed experimentally that, whereas an alternate movement might have caused excessive pitching, a simultaneous movement would have caused only a slight pitch, which could have been easily controlled by the hind flippers. Of the other axial movements, rolling could have been controlled by alternately engaging the flippers of the right or left side, and Yaw (rotation), yaw by the long neck or a vertical tail fin. Sanders did not believe that the hind pair was not used for propulsion, concluding that the limitations imposed by the hip joint were very relative. In 2010, Sanders & Carpenter concluded that, with an alternating gait, the turbulence caused by the front pair would have hindered an effective action of the hind pair. Besides, a long gliding phase after a simultaneous engagement would have been very energy efficient. It is also possible that the gait was optional and was adapted to the circumstances. During a fast steady pursuit, an alternate movement would have been useful; in an ambush, a simultaneous stroke would have made a peak speed possible. When searching for prey over a longer distance, a combination of a simultaneous movement with gliding would have cost the least energy. In 2017, a study by Luke Muscutt, using a robot model, concluded that the rear flippers were actively employed, allowing for a 60% increase of the propulsive force and a 40% increase of efficiency. The stroke would have been at its most powerful using a slightly alternating gait, the rear flippers engaging just after the front flippers, to benefit from their wake. However, there would not have been a single optimal phase for all conditions, the gait likely having been changed as the situation demanded.

Like all tetrapods with limbs, plesiosaurs must have had a certain gait, a coordinated movement pattern of the, in this case, flippers. Of all the possibilities, in practice attention has been largely directed to the question of whether the front pair and hind pair moved simultaneously, so that all four flippers were engaged at the same moment, or in an alternate pattern, each pair being employed in turn. Frey & Riess in 1991 proposed an alternate model, which would have had the advantage of a more continuous propulsion. In 2000, Theagarten Lingham-Soliar evaded the question by concluding that, like sea turtles, plesiosaurs only used the front pair for a powered stroke. The hind pair would have been merely used for steering. Lingham-Soliar deduced this from the form of the hip joint, which would have allowed for only a limited vertical movement. Furthermore, a separation of the propulsion and steering function would have facilitated the general coordination of the body and prevented a too extreme Pitch (aviation), pitch. He rejected Robinson's hypothesis that elastic energy was stored in the ribcage, considering the ribs too stiff for this.

The interpretation by Frey & Riess became the dominant one, but was challenged in 2004 by Sanders, who showed experimentally that, whereas an alternate movement might have caused excessive pitching, a simultaneous movement would have caused only a slight pitch, which could have been easily controlled by the hind flippers. Of the other axial movements, rolling could have been controlled by alternately engaging the flippers of the right or left side, and Yaw (rotation), yaw by the long neck or a vertical tail fin. Sanders did not believe that the hind pair was not used for propulsion, concluding that the limitations imposed by the hip joint were very relative. In 2010, Sanders & Carpenter concluded that, with an alternating gait, the turbulence caused by the front pair would have hindered an effective action of the hind pair. Besides, a long gliding phase after a simultaneous engagement would have been very energy efficient. It is also possible that the gait was optional and was adapted to the circumstances. During a fast steady pursuit, an alternate movement would have been useful; in an ambush, a simultaneous stroke would have made a peak speed possible. When searching for prey over a longer distance, a combination of a simultaneous movement with gliding would have cost the least energy. In 2017, a study by Luke Muscutt, using a robot model, concluded that the rear flippers were actively employed, allowing for a 60% increase of the propulsive force and a 40% increase of efficiency. The stroke would have been at its most powerful using a slightly alternating gait, the rear flippers engaging just after the front flippers, to benefit from their wake. However, there would not have been a single optimal phase for all conditions, the gait likely having been changed as the situation demanded.

In general, it is hard to determine the maximum speed of extinct sea creatures. For plesiosaurs, this is made more difficult by the lack of consensus about their flipper stroke and gait. There are no exact calculations of their Reynolds Number. Fossil impressions show that the skin was relatively smooth, not scaled, and this may have reduced form drag. Small wrinkles are present in the skin that may have prevented separation of the laminar flow in the boundary layer and thereby reduced skin friction.

Cruise (flight), Sustained speed may be estimated by calculating the Drag (physics), drag of a simplified model of the body, that can be approached by a prolate spheroid, and the sustainable level of energy output by the muscles. A first study of this problem was published by Judy Massare in 1988. Even when assuming a low hydrodynamic efficiency of 0.65, Massare's model seemed to indicate that plesiosaurs, if warm-blooded, would have cruised at a speed of four metres per second, or about fourteen kilometres per hour, considerably exceeding the known speeds of extant dolphins and whales.Massare, J. A., 1994, "Swimming capabilities of Mesozoic marine reptiles: a review", In: L. Maddock et al. (eds.) ''Mechanics and Physiology of Animal Swimming'', Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press pp. 133-149 However, in 2002 Ryosuke Motani showed that the formulae that Massare had used, had been flawed. A recalculation, using corrected formulae, resulted in a speed of half a metre per second (1.8 km/h) for a cold-blooded plesiosaur and one and a half metres per second (5.4 km/h) for an endothermic plesiosaur. Even the highest estimate is about a third lower than the speed of extant Cetacea.

Massare also tried to compare the speeds of plesiosaurs with those of the two other main sea reptile groups, the Ichthyosauria and the Mosasauridae. She concluded that plesiosaurs were about twenty percent slower than advanced ichthyosaurs, which employed a very effective tunniform movement, oscillating just the tail, but five percent faster than mosasaurids, which were assumed to swim with an inefficient anguilliform, eel-like, movement of the body.

The many plesiosaur species may have differed considerably in their swimming speeds, reflecting the various body shapes present in the group. While the short-necked "pliosauromorphs" (e.g. ''Liopleurodon'') may have been fast swimmers, the long-necked "plesiosauromorphs" were built more for manoeuvrability than for speed, slowed by a strong skin friction, yet capable of a fast rolling movement. Some long-necked forms, such as the Elasmosauridae, also have relatively short stubby flippers with a low Aspect ratio (wing), aspect ratio, further reducing speed but improving roll.

In general, it is hard to determine the maximum speed of extinct sea creatures. For plesiosaurs, this is made more difficult by the lack of consensus about their flipper stroke and gait. There are no exact calculations of their Reynolds Number. Fossil impressions show that the skin was relatively smooth, not scaled, and this may have reduced form drag. Small wrinkles are present in the skin that may have prevented separation of the laminar flow in the boundary layer and thereby reduced skin friction.

Cruise (flight), Sustained speed may be estimated by calculating the Drag (physics), drag of a simplified model of the body, that can be approached by a prolate spheroid, and the sustainable level of energy output by the muscles. A first study of this problem was published by Judy Massare in 1988. Even when assuming a low hydrodynamic efficiency of 0.65, Massare's model seemed to indicate that plesiosaurs, if warm-blooded, would have cruised at a speed of four metres per second, or about fourteen kilometres per hour, considerably exceeding the known speeds of extant dolphins and whales.Massare, J. A., 1994, "Swimming capabilities of Mesozoic marine reptiles: a review", In: L. Maddock et al. (eds.) ''Mechanics and Physiology of Animal Swimming'', Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press pp. 133-149 However, in 2002 Ryosuke Motani showed that the formulae that Massare had used, had been flawed. A recalculation, using corrected formulae, resulted in a speed of half a metre per second (1.8 km/h) for a cold-blooded plesiosaur and one and a half metres per second (5.4 km/h) for an endothermic plesiosaur. Even the highest estimate is about a third lower than the speed of extant Cetacea.

Massare also tried to compare the speeds of plesiosaurs with those of the two other main sea reptile groups, the Ichthyosauria and the Mosasauridae. She concluded that plesiosaurs were about twenty percent slower than advanced ichthyosaurs, which employed a very effective tunniform movement, oscillating just the tail, but five percent faster than mosasaurids, which were assumed to swim with an inefficient anguilliform, eel-like, movement of the body.

The many plesiosaur species may have differed considerably in their swimming speeds, reflecting the various body shapes present in the group. While the short-necked "pliosauromorphs" (e.g. ''Liopleurodon'') may have been fast swimmers, the long-necked "plesiosauromorphs" were built more for manoeuvrability than for speed, slowed by a strong skin friction, yet capable of a fast rolling movement. Some long-necked forms, such as the Elasmosauridae, also have relatively short stubby flippers with a low Aspect ratio (wing), aspect ratio, further reducing speed but improving roll.

As reptiles in general are oviparous, until the end of the twentieth century it had been seen as possible that smaller plesiosaurs may have crawled up on a beach to lay eggs, like modern turtles. Their strong limbs and a flat underside seemed to have made this feasible. This method was, for example, defended by Halstead. However, as those limbs no longer had functional elbow or knee joints and the underside by its very flatness would have generated a lot of friction, already in the nineteenth century it was hypothesised that plesiosaurs had been viviparous. Besides, it was hard to conceive how the largest species, as big as whales, could have survived a beaching. Fossil finds of ichthyosaur embryos showed that at least one group of marine reptiles had borne live young. The first to claim that similar embryos had been found in plesiosaurs was Harry Govier Seeley, who reported in 1887 having acquired a Nodule (geology), nodule with four to eight tiny skeletons. In 1896, he described this discovery in more detail. If authentic, the embryos of plesiosaurs would have been very small, like those of ichthyosaurs. However, in 1982 Richard Anthony Thulborn showed that Seeley had been deceived by a "doctored" fossil of a nest of crayfish.

An actual plesiosaur specimen found in 1987 eventually proved that plesiosaurs gave birth to live young: This fossil of a pregnant ''Polycotylus latippinus'' shows that these animals gave birth to a single large juvenile and probably invested parental care in their offspring, similar to modern whales. The young was 1.5 metres (five feet) long and thus large compared to its mother of five metres (sixteen feet) length, indicating a K-strategy in reproduction. Little is known about growth rates or a possible sexual dimorphism.

As reptiles in general are oviparous, until the end of the twentieth century it had been seen as possible that smaller plesiosaurs may have crawled up on a beach to lay eggs, like modern turtles. Their strong limbs and a flat underside seemed to have made this feasible. This method was, for example, defended by Halstead. However, as those limbs no longer had functional elbow or knee joints and the underside by its very flatness would have generated a lot of friction, already in the nineteenth century it was hypothesised that plesiosaurs had been viviparous. Besides, it was hard to conceive how the largest species, as big as whales, could have survived a beaching. Fossil finds of ichthyosaur embryos showed that at least one group of marine reptiles had borne live young. The first to claim that similar embryos had been found in plesiosaurs was Harry Govier Seeley, who reported in 1887 having acquired a Nodule (geology), nodule with four to eight tiny skeletons. In 1896, he described this discovery in more detail. If authentic, the embryos of plesiosaurs would have been very small, like those of ichthyosaurs. However, in 1982 Richard Anthony Thulborn showed that Seeley had been deceived by a "doctored" fossil of a nest of crayfish.

An actual plesiosaur specimen found in 1987 eventually proved that plesiosaurs gave birth to live young: This fossil of a pregnant ''Polycotylus latippinus'' shows that these animals gave birth to a single large juvenile and probably invested parental care in their offspring, similar to modern whales. The young was 1.5 metres (five feet) long and thus large compared to its mother of five metres (sixteen feet) length, indicating a K-strategy in reproduction. Little is known about growth rates or a possible sexual dimorphism.

The belief that plesiosaurs are dinosaurs is a List of common misconceptions, common misconception, and plesiosaurs are often Cultural depictions of dinosaurs, erroneously depicted as dinosaurs in popular culture.

It has been suggested that legends of sea serpents and modern sightings of supposed lake monster, monsters in lakes or the sea could be explained by the survival of plesiosaurs into modern times. This cryptozoological proposal has been rejected by the scientific community at large, which considers it to be based on fantasy and pseudoscience. Purported plesiosaur carcasses have been shown to be partially decomposed corpses of basking sharks instead.

While the Loch Ness monster is often reported as looking like a plesiosaur, it is also often described as looking completely different. A number of reasons have been presented for it to be unlikely to be a plesiosaur. They include the assumption that the water in the loch is too cold for a presumed Ectothermy, cold-blooded reptile to be able to survive easily, the assumption that air-breathing animals would be easy to see whenever they appear at the surface to breathe, the fact that the loch is too small and contains insufficient food to be able to support a breeding colony of large animals, and finally the fact that the lake was formed only 10,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age, and the latest fossil appearance of plesiosaurs dates to over 66 million years ago. Frequent explanations for the sightings include waves, floating inanimate objects, tricks of the light, swimming known animals and practical jokes. Nevertheless, in the popular imagination, plesiosaurs have come to be identified with the Monster of Loch Ness. That has had the advantage of making the group better known to the general public, but the disadvantage that people have trouble taking the subject seriously, forcing paleontologists to explain time and time again that plesiosaurs really existed and are not merely creatures of myth or fantasy.Ellis (2003), pp. 1–3.

The belief that plesiosaurs are dinosaurs is a List of common misconceptions, common misconception, and plesiosaurs are often Cultural depictions of dinosaurs, erroneously depicted as dinosaurs in popular culture.

It has been suggested that legends of sea serpents and modern sightings of supposed lake monster, monsters in lakes or the sea could be explained by the survival of plesiosaurs into modern times. This cryptozoological proposal has been rejected by the scientific community at large, which considers it to be based on fantasy and pseudoscience. Purported plesiosaur carcasses have been shown to be partially decomposed corpses of basking sharks instead.

While the Loch Ness monster is often reported as looking like a plesiosaur, it is also often described as looking completely different. A number of reasons have been presented for it to be unlikely to be a plesiosaur. They include the assumption that the water in the loch is too cold for a presumed Ectothermy, cold-blooded reptile to be able to survive easily, the assumption that air-breathing animals would be easy to see whenever they appear at the surface to breathe, the fact that the loch is too small and contains insufficient food to be able to support a breeding colony of large animals, and finally the fact that the lake was formed only 10,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age, and the latest fossil appearance of plesiosaurs dates to over 66 million years ago. Frequent explanations for the sightings include waves, floating inanimate objects, tricks of the light, swimming known animals and practical jokes. Nevertheless, in the popular imagination, plesiosaurs have come to be identified with the Monster of Loch Ness. That has had the advantage of making the group better known to the general public, but the disadvantage that people have trouble taking the subject seriously, forcing paleontologists to explain time and time again that plesiosaurs really existed and are not merely creatures of myth or fantasy.Ellis (2003), pp. 1–3.

The Plesiosaur Site

'. Richard Forrest. *

The Plesiosaur Directory

'. Adam Stuart Smith. *

Plesiosauria

technical definition at the Plesiosaur Directory *

Plesiosaur FAQ's

'. Raymond Thaddeus C. Ancog. *

'. Mike Everhart. *

Plesiosaur fossil found in Bridgwater Bay

. ''Somersert Museums County Service''. (best known fossil) *

. Allan Hall and Mark Henderson. ''Times Online'', December 30, 2002. (Monster of Aramberri) *

Triassic reptiles had live young

'.

Bridgwater Bay juvenile plesiosaur

Just How Good Is the Plesiosaur Fossil Record? ''Laelaps Blog''.

{{Authority control Plesiosaurs, Taxa named by Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville Fossil taxa described in 1835 Rhaetian first appearances Late Triassic taxonomic orders Early Jurassic taxonomic orders Middle Jurassic taxonomic orders Late Jurassic taxonomic orders Early Cretaceous taxonomic orders Late Cretaceous taxonomic orders Maastrichtian extinctions Articles containing video clips

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosauria became ...

.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago (Year#Abbreviations yr and ya, Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 ...

Period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Era, a length or span of time

* Full stop (or period), a punctuation mark

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (or rhetorical period), a concept ...

, possibly in the Rhaetian stage, about 203 million years ago. They became especially common during the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

Period, thriving until their disappearance due to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event (also known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction) was a sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, approximately 66 million years ago. With the ...

at the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

Period, about 66 million years ago. They had a worldwide oceanic distribution, and some species at least partly inhabited freshwater environments.

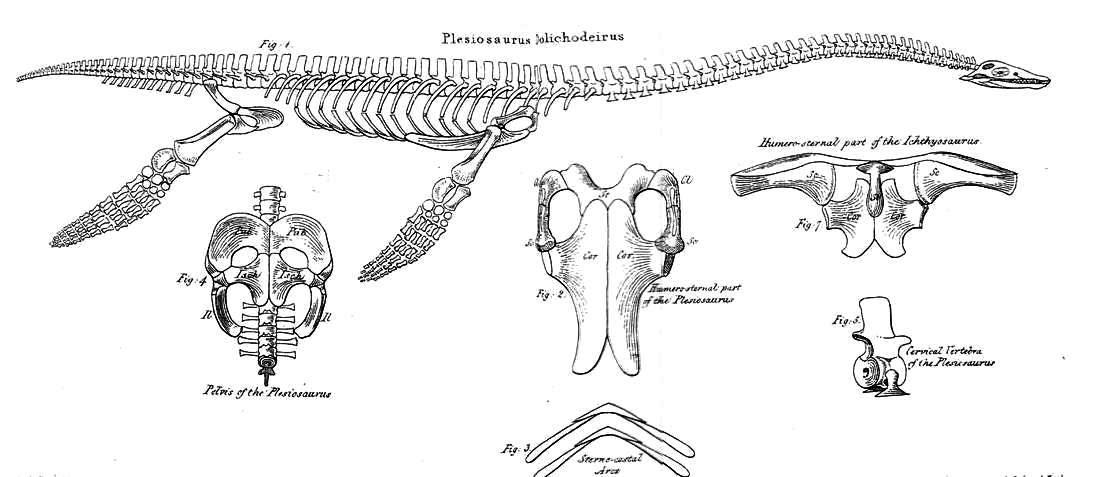

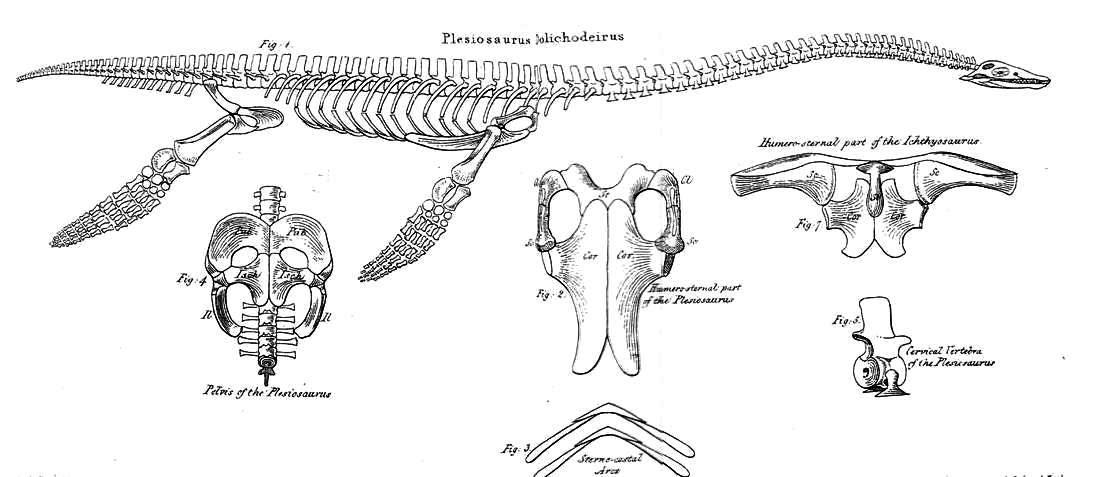

Plesiosaurs were among the first fossil reptiles discovered. In the beginning of the nineteenth century, scientists realised how distinctive their build was and they were named as a separate order in 1835. The first plesiosaurian genus, the eponymous ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable b ...

'', was named in 1821. Since then, more than a hundred valid species have been described. In the early twenty-first century, the number of discoveries has increased, leading to an improved understanding of their anatomy, relationships and way of life.

Plesiosaurs had a broad flat body and a short tail. Their limbs had evolved into four long flippers, which were powered by strong muscles attached to wide bony plates formed by the shoulder girdle and the pelvis. The flippers made a flying movement through the water. Plesiosaurs breathed air, and bore live young; there are indications that they were warm-blooded.

Plesiosaurs showed two main morphological types. Some species, with the "plesiosauromorph" build, had (sometimes extremely) long necks and small heads; these were relatively slow and caught small sea animals. Other species, some of them reaching a length of up to seventeen metres, had the "pliosauromorph" build with a short neck and a large head; these were apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the highest trophic lev ...

s, fast hunters of large prey. The two types are related to the traditional strict division of the Plesiosauria into two suborders, the long-necked Plesiosauroidea

Plesiosauroidea (; Greek: 'near, close to' and 'lizard') is an extinct clade of carnivorous marine reptiles. They have the snake-like longest neck to body ratio of any reptile. Plesiosauroids are known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous period ...

and the short-neck Pliosauroidea

Pliosauroidea is an extinct clade of plesiosaurs, known from the earliest Jurassic to early Late Cretaceous. They are best known for the subclade Thalassophonea, which contained crocodile-like short-necked forms with large heads and massive t ...

. Modern research, however, indicates that several "long-necked" groups might have had some short-necked members or vice versa. Therefore, the purely descriptive terms "plesiosauromorph" and "pliosauromorph" have been introduced, which do not imply a direct relationship. "Plesiosauroidea" and "Pliosauroidea" today have a more limited meaning. The term "plesiosaur" is properly used to refer to the Plesiosauria as a whole, but informally it is sometimes meant to indicate only the long-necked forms, the old Plesiosauroidea.

History of discovery

Early finds

Skeletal elements of plesiosaurs are among the first fossils of extinct reptiles recognised as such. In 1605,

Skeletal elements of plesiosaurs are among the first fossils of extinct reptiles recognised as such. In 1605, Richard Verstegen

Richard Rowlands, born Richard Verstegan (c. 1550 – 1640), was an Anglo- Dutch antiquary, publisher, humorist and translator. Verstegan was born in East London the son of a cooper; his grandfather, Theodore Roland Verstegen, was a refugee f ...

of Antwerp illustrated in his ''A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence'' plesiosaur vertebrae that he referred to fishes and saw as proof that Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

was once connected to the European continent. The Welshman Edward Lhuyd

Edward Lhuyd FRS (; occasionally written Llwyd in line with modern Welsh orthography, 1660 – 30 June 1709) was a Welsh naturalist, botanist, linguist, geographer and antiquary. He is also named in a Latinate form as Eduardus Luidius.

Life

...

in his ''Lithophylacii Brittannici Ichnographia'' from 1699 also included depictions of plesiosaur vertebrae that again were considered fish vertebrae or ''Ichthyospondyli''. Other naturalists during the seventeenth century added plesiosaur remains to their collections, such as John Woodward John Woodward or ''variant'', may refer to:

Sports

* John Woodward (English footballer) (born 1947), former footballer

* John Woodward (Scottish footballer) (born 1949), former footballer

* Johnny Woodward (1924–2002), English footballer

* Jo ...

; these were only much later understood to be of a plesiosaurian nature and are today partly preserved in the Sedgwick Museum

The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, is the geology museum of the University of Cambridge. It is part of the Department of Earth Sciences and is located on the university's Downing Site in Downing Street, central Cambridge, England. The Sedgw ...

.

In 1719, William Stukeley described a partial skeleton of a plesiosaur, which had been brought to his attention by the great-grandfather of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, Robert Darwin of Elston. The stone plate came from a quarry at Fulbeck

Fulbeck is a small village and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. The population (including Byards Leap) taken at the 2011 census was 513. The village is on the A607, north from Grantham and north-west from ...

in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-we ...

and had been used, with the fossil at its underside, to reinforce the slope of a watering-hole in Elston

Elston is a village and civil parish in Nottinghamshire, England, to the south-west of Newark, and a mile from the A46 Fosse Way. The population of the civil parish taken at the 2011 Census was 631. It lies between the rivers Trent and Devon ...

in Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The trad ...

. After the strange bones it contained had been discovered, it was displayed in the local vicarage as the remains of a sinner drowned in the Great Flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primaeval ...

. Stukely affirmed its " diluvial" nature but understood it represented some sea creature, perhaps a crocodile or dolphin. The specimen is today preserved in the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

, its inventory number being BMNH R.1330. It is the earliest discovered more or less complete fossil reptile skeleton in a museum collection. It can perhaps be referred to ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable b ...

dolichodeirus''.

During the eighteenth century, the number of English plesiosaur discoveries rapidly increased, although these were all of a more or less fragmentary nature. Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and

During the eighteenth century, the number of English plesiosaur discoveries rapidly increased, although these were all of a more or less fragmentary nature. Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and Baptist Noel Turner

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

, active in the Vale of Belvoir, whose collections were in 1795 described by John Nicholls in the first part of his ''The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicestershire''. One of Turner's partial plesiosaur skeletons is still preserved as specimen BMNH R.45 in the British Museum of Natural History; this is today referred to ''Thalassiodracon

''Thalassiodracon'' (tha-LAS-ee-o-DRAY-kon) is an extinct genus of plesiosauroid from the Pliosauridae that was alive during the Late Triassic-Early Jurassic (Rhaetian-Hettangian) and is known exclusively from the Lower Lias of England. The t ...

''.

Naming of ''Plesiosaurus''

In the early nineteenth century, plesiosaurs were still poorly known and their special build was not understood. No systematic distinction was made with

In the early nineteenth century, plesiosaurs were still poorly known and their special build was not understood. No systematic distinction was made with ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, alt ...

, so the fossils of one group were sometimes combined with those of the other to obtain a more complete specimen. In 1821, a partial skeleton discovered in the collection of Colonel Thomas James Birch, was described by William Conybeare and Henry Thomas De la Beche, and recognised as representing a distinctive group. A new genus was named, ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable b ...

''. The generic name was derived from the Greek πλήσιος, ''plèsios'', "closer to" and the Latinised ''saurus'', in the meaning of "saurian", to express that ''Plesiosaurus'' was in the Chain of Being

The great chain of being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The chain begins with God and descends through angels, humans, animals and plants to minerals.

The great c ...

more closely positioned to the Sauria

Sauria is the clade containing the most recent common ancestor of archosaurs (such as crocodilians, dinosaurs, etc.) and lepidosaurs ( lizards and kin), and all its descendants. Since most molecular phylogenies recover turtles as more closely ...

, particularly the crocodile, than ''Ichthyosaurus

''Ichthyosaurus'' (derived from Greek ' () meaning 'fish' and ' () meaning 'lizard') is a genus of ichthyosaurs from the Early Jurassic (Hettangian - Pliensbachian), with possible Late Triassic record, from Europe ( Belgium, England, Germany, ...

'', which had the form of a more lowly fish. The name should thus be rather read as "approaching the Sauria" or "near reptile" than as "near lizard". Parts of the specimen are still present in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History, sometimes known simply as the Oxford University Museum or OUMNH, is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It a ...

.

Soon afterwards, the morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

became much better known. In 1823, Thomas Clark reported an almost complete skull, probably belonging to ''Thalassiodracon'', which is now preserved by the British Geological Survey as specimen BGS GSM 26035. The same year, commercial fossil collector Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known around the world for the discoveries she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel ...

and her family uncovered an almost complete skeleton at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and beaches on the Heri ...

in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

, England, on what is today called the Jurassic Coast

The Jurassic Coast is a World Heritage Site on the English Channel coast of southern England. It stretches from Exmouth in East Devon to Studland Bay in Dorset, a distance of about , and was inscribed on the World Heritage List in mid-Decembe ...

. It was acquired by the Duke of Buckingham

Duke of Buckingham held with Duke of Chandos, referring to Buckingham, is a title that has been created several times in the peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. There have also been earls and marquesses of Buckingham.

...

, who made it available to the geologist William Buckland

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named ' ...

. He in turn let it be described by Conybeare on 24 February 1824 in a lecture to the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

, during the same meeting in which for the first time a dinosaur was named, ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period (Bathonian stage, 166 million years ...

''. The two finds revealed the unique and bizarre build of the animals, in 1832 by Professor Buckland likened to "a sea serpent run through a turtle". In 1824, Conybeare also provided a specific name to ''Plesiosaurus'': ''dolichodeirus'', meaning "longneck". In 1848, the skeleton was bought by the British Museum of Natural History and catalogued as specimen BMNH 22656. When the lecture was published, Conybeare also named a second species: ''Plesiosaurus giganteus''. This was a short-necked form later assigned to the Pliosauroidea

Pliosauroidea is an extinct clade of plesiosaurs, known from the earliest Jurassic to early Late Cretaceous. They are best known for the subclade Thalassophonea, which contained crocodile-like short-necked forms with large heads and massive t ...

.

Plesiosaurs became better known to the general public through two lavishly illustrated publications by the collector Thomas Hawkins: ''Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri'' of 1834 and ''The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons'' of 1840. Hawkins entertained a very idiosyncratic view of the animals, seeing them as monstrous creations of the devil, during a pre-Adamitic phase of history. Hawkins eventually sold his valuable and attractively restored specimens to the British Museum of Natural History.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the number of plesiosaur finds steadily increased, especially through discoveries in the sea cliffs of Lyme Regis. Sir Richard Owen alone named nearly a hundred new species. The majority of their descriptions were, however, based on isolated bones, without sufficient diagnosis to be able to distinguish them from the other species that had previously been described. Many of the new species described at this time have subsequently been invalidated. The genus ''Plesiosaurus'' is particularly problematic, as the majority of the new species were placed in it so that it became a

Plesiosaurs became better known to the general public through two lavishly illustrated publications by the collector Thomas Hawkins: ''Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri'' of 1834 and ''The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons'' of 1840. Hawkins entertained a very idiosyncratic view of the animals, seeing them as monstrous creations of the devil, during a pre-Adamitic phase of history. Hawkins eventually sold his valuable and attractively restored specimens to the British Museum of Natural History.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the number of plesiosaur finds steadily increased, especially through discoveries in the sea cliffs of Lyme Regis. Sir Richard Owen alone named nearly a hundred new species. The majority of their descriptions were, however, based on isolated bones, without sufficient diagnosis to be able to distinguish them from the other species that had previously been described. Many of the new species described at this time have subsequently been invalidated. The genus ''Plesiosaurus'' is particularly problematic, as the majority of the new species were placed in it so that it became a wastebasket taxon

Wastebasket taxon (also called a wastebin taxon, dustbin taxon or catch-all taxon) is a term used by some taxonomists to refer to a taxon that has the sole purpose of classifying organisms that do not fit anywhere else. They are typically defined ...

. Gradually, other genera were named. Hawkins had already created new genera, though these are no longer seen as valid. In 1841, Owen named ''Pliosaurus

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages (Late Jurassic) of Europe and South America. Their diet would have included fish, cephalopods, and marin ...

brachydeirus''. Its etymology

Etymology ()The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the Phonological chan ...

referred to the earlier ''Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus'' as it is derived from πλεῖος, ''pleios'', "more fully", reflecting that according to Owen it was closer to the Sauria than ''Plesiosaurus''. Its specific name means "with a short neck". Later, the Pliosauridae

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Rhaetian to Turonian stages) of Australia, Europe, North America and South America. The family is more inclusive than the archetypal ...

were recognised as having a morphology fundamentally different from the plesiosaurids. The family Plesiosauridae had already been coined by John Edward Gray

John Edward Gray, FRS (12 February 1800 – 7 March 1875) was a British zoologist. He was the elder brother of zoologist George Robert Gray and son of the pharmacologist and botanist Samuel Frederick Gray (1766–1828). The same is used for ...

in 1825. In 1835, Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville

Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (; 12 September 1777 – 1 May 1850) was a French zoologist and anatomist.

Life

Blainville was born at Arques, near Dieppe. As a young man he went to Paris to study art, but ultimately devoted himself to natur ...

named the order Plesiosauria itself.

American discoveries

In the second half of the nineteenth century, important finds were made outside of England. While this included some German discoveries, it mainly involved plesiosaurs found in the sediments of the American CretaceousWestern Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, and the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea that split the continent of North America into two landmasses. The ancient sea ...

, the Niobrara Chalk

The Niobrara Formation , also called the Niobrara Chalk, is a geologic formation in North America that was deposited between 87 and 82 million years ago during the Coniacian, Santonian, and Campanian stages of the Late Cretaceous. It is compose ...

. One fossil in particular marked the start of the Bone Wars

The Bone Wars, also known as the Great Dinosaur Rush, was a period of intense and ruthlessly competitive fossil hunting and discovery during the Gilded Age of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope (of the Ac ...

between the rival paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among ...

.

In 1867, physician Theophilus Turner near Fort Wallace in

In 1867, physician Theophilus Turner near Fort Wallace in Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

uncovered a plesiosaur skeleton, which he donated to Cope. Cope attempted to reconstruct the animal on the assumption that the longer extremity of the vertebral column was the tail, the shorter one the neck. He soon noticed that the skeleton taking shape under his hands had some very special qualities: the neck vertebrae had chevrons and with the tail vertebrae the joint surfaces were orientated back to front. Excited, Cope concluded to have discovered an entirely new group of reptiles: the Streptosauria or "Turned Saurians", which would be distinguished by reversed vertebrae and a lack of hindlimbs, the tail providing the main propulsion. After having published a description of this animal, followed by an illustration in a textbook about reptiles and amphibians, Cope invited Marsh and Joseph Leidy

Joseph Mellick Leidy (September 9, 1823 – April 30, 1891) was an American paleontologist, parasitologist and anatomist.

Leidy was professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, later was a professor of natural history at Swarthmore ...

to admire his new ''Elasmosaurus

''Elasmosaurus'' (;) is a genus of plesiosaur that lived in North America during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, about 80.5million years ago. The first specimen was discovered in 1867 near Fort Wallace, Kansas, US, and was se ...

platyurus''. Having listened to Cope's interpretation for a while, Marsh suggested that a simpler explanation of the strange build would be that Cope had reversed the vertebral column relative to the body as a whole. When Cope reacted indignantly to this suggestion, Leidy silently took the skull and placed it against the presumed last tail vertebra, to which it fitted perfectly: it was in fact the first neck vertebra, with still a piece of the rear skull attached to it. Mortified, Cope tried to destroy the entire edition of the textbook and, when this failed, immediately published an improved edition with a correct illustration but an identical date of publication. He excused his mistake by claiming that he had been misled by Leidy himself, who, describing a specimen of ''Cimoliasaurus

''Cimoliasaurus'' was a plesiosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of New Jersey. It grew up to long and weighed up to .

Etymology

The name is derived from the Greek , meaning "white chalk", and , meaning "lizard", in ...

'', had also reversed the vertebral column. Marsh later claimed that the affair was the cause of his rivalry with Cope: "he has since been my bitter enemy". Both Cope and Marsh in their rivalry named many plesiosaur genera and species, most of which are today considered invalid.

Around the turn of the century, most plesiosaur research was done by a former student of Marsh, Professor Samuel Wendell Williston

Samuel Wendell Williston (July 10, 1852 – August 30, 1918) was an American educator, entomologist, and paleontologist who was the first to propose that birds developed flight cursorially (by running), rather than arboreally (by leaping from tr ...

. In 1914, Williston published his ''Water reptiles of the past and present''. Despite treating sea reptiles in general, it would for many years remain the most extensive general text on plesiosaurs. In 2013, a first modern textbook was being prepared by Olivier Rieppel

Olivier is the French form of the given name Oliver. It may refer to:

* Olivier (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Olivier (surname), a list of people

* Château Olivier, a Bordeaux winery

*Olivier, Louisiana, a rural popul ...

. During the middle of the twentieth century, the USA remained an important centre of research, mainly through the discoveries of Samuel Paul Welles

Samuel Paul Welles (November 9, 1907 – August 6, 1997) was an American palaeontologist. Welles was a research associate at the Museum of Palaeontology, University of California, Berkeley. He took part in excavations at the Placerias Quarry in ...

.

Recent discoveries

Whereas during the nineteenth and most of the twentieth century, new plesiosaurs were described at a rate of three or four novel genera each decade, the pace suddenly picked up in the 1990s, with seventeen plesiosaurs being discovered in this period. The tempo of discovery accelerated in the early twenty-first century, with about three or four plesiosaurs being named each year. This implies that about half of the known plesiosaurs are relatively new to science, a result of a far more intense field research. Some of this is taking place away from the traditional areas, e.g. in new sites developed inNew Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

, Japan, China and Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

, but the locations of the more original discoveries have proven to be still productive, with important new finds in England and Germany. Some of the new genera are a renaming of already known species, which were deemed sufficiently different to warrant a separate genus name.

In 2002, the " Monster of Aramberri" was announced to the press. Discovered in 1982 at the village of Aramberri, in the northern Mexican state of Nuevo León, it was originally classified as a dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

. The specimen is actually a very large plesiosaur, possibly reaching in length. The media published exaggerated reports claiming it was long, and weighed up to , which would have made it among the largest predators of all time.

In 2004, what appeared to be a completely intact juvenile plesiosaur was discovered, by a local fisherman, at Bridgwater Bay

Bridgwater Bay is on the Bristol Channel, north of Bridgwater in Somerset, England at the mouth of the River Parrett and the end of the River Parrett Trail. It stretches from Minehead at the southwestern end of the bay to Brean Down in the nor ...

National Nature Reserve in Somerset, UK. The fossil, dating from 180 million years ago as indicated by the ammonites associated with it, measured in length, and may be related to ''Rhomaleosaurus

''Rhomaleosaurus'' (meaning "strong lizard") is an extinct genus of Early Jurassic ( Toarcian age, about 183 to 175.6 million years ago) rhomaleosaurid pliosauroid known from Northamptonshire and from Yorkshire of the United Kingdom. It was fi ...

''. It is probably the best preserved specimen of a plesiosaur yet discovered.

In 2005, the remains of three plesiosaurs (''Dolichorhynchops herschelensis

''Dolichorhynchops'' is an extinct genus of polycotylid plesiosaur from the Late Cretaceous (early Turonian to late Campanian stage) of North America, containing three species, ''D. osborni'', ''D. bonneri'' and ''D. tropicensis'', as well as a ...

'') discovered in the 1990s near Herschel, Saskatchewan

Herschel is a special service area in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. It is the seat of the Rural Municipality of Mountain View No. 318 and held village status prior to December 31, 2006. The population was 30 people in 2016. The communi ...

were found to be a new species, by Dr. Tamaki Sato, a Japanese vertebrate paleontologist.

In 2006, a combined team of American and Argentinian investigators (the latter from the Argentinian Antarctic Institute and the La Plata Museum

The La Plata Museum ( es, Museo de la Plata) is a natural history museum in La Plata, Argentina. It is part of the (Natural Sciences School) of the UNLP ( National University of La Plata).

The building, long, today houses 3 million fossils an ...

) found the skeleton of a juvenile plesiosaur measuring in length on Vega Island in Antarctica. The fossil is currently on display at the geological museum of South Dakota School of Mines and Technology

The South Dakota School of Mines & Technology (South Dakota Mines, SD Mines, or SDSM&T) is a public university in Rapid City, South Dakota. It is governed by the South Dakota Board of Regents and was founded in 1885. South Dakota Mines offers ba ...

.

In 2008, fossil remains of an undescribed plesiosaur that was named Predator X, now known as ''Pliosaurus funkei'', were unearthed in Svalbard. It had a length of , and its bite force of is one of the most powerful known.

In December 2017, a large skeleton of a plesiosaur was found in the continent of Antarctica, the oldest creature on the continent, and the first of its species in Antarctica.

Not only has the number of field discoveries increased, but also, since the 1950s, plesiosaurs have been the subject of more extensive theoretical work. The methodology of cladistics has, for the first time, allowed the exact calculation of their evolutionary relationships. Several hypotheses have been published about the way they hunted and swam, incorporating general modern insights about biomechanics and ecology. The many recent discoveries have tested these hypotheses and given rise to new ones.

Evolution

The Plesiosauria have their origins within the

The Plesiosauria have their origins within the Sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosauria became ...

, a group of perhaps archelosaurian reptiles that returned to the sea. An advanced sauropterygian subgroup, the carnivorous Eusauropterygia with small heads and long necks, split into two branches during the Upper Triassic. One of these, the Nothosauroidea, kept functional elbow and knee joints; but the other, the Pistosauria, became more fully adapted to a sea-dwelling lifestyle. Their vertebral column became stiffer and the main propulsion while swimming no longer came from the tail but from the limbs, which changed into flippers. The Pistosauria became warm-blooded and viviparous, giving birth to live young. Early, basal (phylogenetics), basal, members of the group, traditionally called "Pistosauridae, pistosaurids", were still largely coastal animals. Their shoulder girdles remained weak, their pelvis, pelves could not support the power of a strong swimming stroke, and their flippers were blunt. Later, a more advanced pistosaurian group split off: the Plesiosauria. These had reinforced shoulder girdles, flatter pelves, and more pointed flippers. Other adaptations allowing them to colonise the open seas included stiff limb joints; an increase in the number of phalanges of the hand and foot; a tighter lateral connection of the finger and toe phalanx series, and a shortened tail.Rieppel, O., 1997, "Introduction to Sauropterygia", In: Callaway, J. M. & Nicholls, E. L. (eds.), ''Ancient marine reptiles'' pp 107–119. Academic Press, San Diego, California

From the earliest

From the earliest Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

, the Hettangian stage, a rich radiation of plesiosaurs is known, implying that the group must already have diversified in the Late Triassic; of this diversification, however, only a few very basal forms have been discovered. The subsequent evolution of the plesiosaurs is very contentious. The various cladistic analyses have not resulted in a consensus about the relationships between the main plesiosaurian subgroups. Traditionally, plesiosaurs have been divided into the long-necked Plesiosauroidea

Plesiosauroidea (; Greek: 'near, close to' and 'lizard') is an extinct clade of carnivorous marine reptiles. They have the snake-like longest neck to body ratio of any reptile. Plesiosauroids are known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous period ...

and the short-necked Pliosauroidea

Pliosauroidea is an extinct clade of plesiosaurs, known from the earliest Jurassic to early Late Cretaceous. They are best known for the subclade Thalassophonea, which contained crocodile-like short-necked forms with large heads and massive t ...

. However, modern research suggests that some generally long-necked groups might have had short-necked members. To avoid confusion between the phylogeny, the evolutionary relationships, and the morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

, the way the animal is built, long-necked forms are therefore called "plesiosauromorph" and short-necked forms are called "pliosauromorph", without the "plesiosauromorph" species necessarily being more closely related to each other than to the "pliosauromorph" forms.

The latest common ancestor of the Plesiosauria was probably a rather small short-necked form. During the earliest Jurassic, the subgroup with the most species was the Rhomaleosauridae, a possibly very basal split-off of species which were also short-necked. Plesiosaurs in this period were at most five metres (sixteen feet) long. By the Toarcian, about 180 million years ago, other groups, among them the Plesiosauridae, became more numerous and some species developed longer necks, resulting in total body lengths of up to .

In the middle of the Jurassic, very large

The latest common ancestor of the Plesiosauria was probably a rather small short-necked form. During the earliest Jurassic, the subgroup with the most species was the Rhomaleosauridae, a possibly very basal split-off of species which were also short-necked. Plesiosaurs in this period were at most five metres (sixteen feet) long. By the Toarcian, about 180 million years ago, other groups, among them the Plesiosauridae, became more numerous and some species developed longer necks, resulting in total body lengths of up to .

In the middle of the Jurassic, very large Pliosauridae

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Rhaetian to Turonian stages) of Australia, Europe, North America and South America. The family is more inclusive than the archetypal ...

evolved. These were characterized by a large head and a short neck, such as ''Liopleurodon'' and ''Simolestes''. These forms had skulls up to three metres (ten feet) long and reached a length of up to and a weight of ten tonnes. The pliosaurids had large, conical teeth and were the dominant marine carnivores of their time. During the same time, approximately 160 million years ago, the Cryptoclididae were present, shorter species with a long neck and a small head.

The Leptocleididae radiated during the Early Cretaceous. These were rather small forms that, despite their short necks, might have been more closely related to the Plesiosauridae than to the Pliosauridae. Later in the Early Cretaceous, the Elasmosauridae appeared; these were among the longest plesiosaurs, reaching up to fifteen metres (fifty feet) in length due to very long necks containing as many as 76 vertebrae, more than any other known vertebrate. Pliosauridae were still present as is shown by large predators, such as ''Kronosaurus''.

At the beginning of the Late Cretaceous, the Ichthyosauria became extinct; perhaps a plesiosaur group evolved to fill their niches: the Polycotylidae, which had short necks and peculiarly elongated heads with narrow snouts. During the Late Cretaceous, the elasmosaurids still had many species.

All plesiosaurs became extinction, extinct as a result of the K-T event at the end of the Cretaceous period, approximately million years ago.

Relationships

In modern phylogeny, clades are defined groups that Monophyly, contain all species belonging to a certain branch of the evolutionary tree. One way to define a clade is to let it consist of the last common ancestor of two such species and all its descendants. Such a clade is called a "node-based taxon, node clade". In 2008, Patrick Druckenmiller and Anthony Russell (paleontologist), Anthony Russell in this way defined Plesiosauria as the group consisting of the last common ancestor of ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable b ...

dolichocheirus'' and ''Peloneustes philarchus'' and all its descendants. ''Plesiosaurus'' and ''Peloneustes'' represented the main subgroups of the Plesiosauroidea and the Pliosauroidea and were chosen for historical reasons; any other species from these groups would have sufficed.

Another way to define a clade is to let it consist of all species more closely related to a certain species that one in any case wishes to include in the clade than to another species that one to the contrary desires to exclude. Such a clade is called a "stem-based taxon, stem clade". Such a definition has the advantage that it is easier to include all species with a certain morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

. Plesiosauria was in 2010 by Hillary Ketchum and Roger Benson defined as such a stem-based taxon: "all taxa more closely related to ''Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus'' and ''Pliosaurus brachydeirus'' than to ''Augustasaurus hagdorni''". Ketchum and Benson (2010) also coined a new clade Neoplesiosauria, a node-based taxon that was defined by as "''Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus'', ''Pliosaurus brachydeirus'', their most recent common ancestor and all of its descendants". The clade Neoplesiosauria very likely is materially identical to Plesiosauria ''sensu'' Druckenmiller & Russell, thus would designate exactly the same species, and the term was meant to be a replacement of this concept.

Benson ''et al.'' (2012) found the traditional Pliosauroidea to be paraphyletic in relation to Plesiosauroidea. Rhomaleosauridae was found to be outside Neoplesiosauria, but still within Plesiosauria. The early Carnian pistosaur ''Bobosaurus'' was found to be one step more advanced than ''Augustasaurus'' in relation to the Plesiosauria and therefore it represented by definition the basalmost known plesiosaur. This analysis focused on basal plesiosaurs and therefore only one derived pliosaurid and one cryptoclidian were included, while Elasmosauridae, elasmosaurids were not included at all. A more detailed analysis published by both Benson and Druckenmiller in 2014 was not able to resolve the relationships among the lineages at the base of Plesiosauria.

Description

Size

In general, plesiosaurians varied in adult length from between to about . The group thus contained some of the largest marine

In general, plesiosaurians varied in adult length from between to about . The group thus contained some of the largest marine apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the highest trophic lev ...

s in the fossil record, roughly equalling the longest ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, alt ...

, mosasaurids, sharks and toothed whales in size. Some plesiosaurian remains, such as a long set of highly reconstructed and fragmentary lower jaws preserved in the Oxford University Museum and referable to ''Pliosaurus rossicus'' (previously referred to ''Stretosaurus'' and ''Liopleurodon''), indicated a length of . However, it was recently argued that its size cannot be currently determined due to their being poorly reconstructed and a length of metres is more likely.McHenry, Colin Richard (2009). "Devourer of Gods: the palaeoecology of the Cretaceous pliosaur ''Kronosaurus queenslandicus''" (PDF): 1–460 MCZ 1285, a specimen currently referable to ''Kronosaurus queenslandicus'', from the Early Cretaceous of Australia, was estimated to have a skull length of .

Skeleton

The typical plesiosaur had a broad, flat, body and a short tail. Plesiosaurs retained their ancestral two pairs of limbs, which had evolved into large Flipper (anatomy), flippers. Plesiosaurs were related to the earlier Nothosauridae, that had a more crocodile-like body. The flipper arrangement is unusual for aquatic animals in that probably all four limbs were used to propel the animal through the water by up-and-down movements. The tail was most likely only used for helping in directional control. This contrasts to theichthyosaurs

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, alt ...

and the later mosasaurs, in which the tail provided the main propulsion.

To power the flippers, the shoulder girdle and the pelvis had been greatly modified, developing into broad bone plates at the underside of the body, which served as an attachment surface for large muscle groups, able to pull the limbs downwards. In the shoulder, the coracoid had become the largest element covering the major part of the breast. The scapula was much smaller, forming the outer front edge of the trunk. To the middle, it continued into a clavicle and finally a small interclavicular bone. As with most tetrapods, the shoulder joint was formed by the scapula and coracoid. In the pelvis, the bone plate was formed by the ischium at the rear and the larger pubic bone in front of it. The Ilium (bone), ilium, which in land vertebrates bears the weight of the hindlimb, had become a small element at the rear, no longer attached to either the pubic bone or the thighbone. The hip joint was formed by the ischium and the pubic bone. The pectoral and pelvic plates were connected by a plastron, a bone cage formed by the paired belly ribs that each had a middle and an outer section. This arrangement immobilised the entire trunk.

To become flippers, the limbs had changed considerably. The limbs were very large, each about as long as the trunk. The forelimbs and hindlimbs strongly resembled each other. The humerus in the upper arm, and the femur in the upper leg, had become large flat bones, expanded at their outer ends. The elbow joints and the knee joints were no longer functional: the lower arm and the lower leg could not flex in relation to the upper limb elements, but formed a flat continuation of them. All outer bones had become flat supporting elements of the flippers, tightly connected to each other and hardly able to rotate, flex, extend or spread. This was true of the ulna, Radius (bone), radius, metacarpals and fingers, as well of the tibia, fibula, metatarsals and toes. Furthermore, in order to elongate the flippers, the number of phalanges had increased, up to eighteen in a row, a phenomenon called hyperphalangy. The flippers were not perfectly flat, but had a lightly convexly curved top profile, like an airfoil, to be able to "fly" through the water.

While plesiosaurs varied little in the build of the trunk, and can be called "conservative" in this respect, there were major differences between the subgroups as regards the form of the neck and the skull. Plesiosaurs can be divided into two major morphological types that differ in head and neck size. "Plesiosauromorphs", such as Cryptoclididae, Elasmosauridae, and Plesiosauridae, had long necks and small heads. "Pliosauromorphs", such as the

While plesiosaurs varied little in the build of the trunk, and can be called "conservative" in this respect, there were major differences between the subgroups as regards the form of the neck and the skull. Plesiosaurs can be divided into two major morphological types that differ in head and neck size. "Plesiosauromorphs", such as Cryptoclididae, Elasmosauridae, and Plesiosauridae, had long necks and small heads. "Pliosauromorphs", such as the Pliosauridae

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Rhaetian to Turonian stages) of Australia, Europe, North America and South America. The family is more inclusive than the archetypal ...

and the Rhomaleosauridae, had shorter necks with a large, elongated head. The neck length variations were not caused by an elongation of the individual cervical vertebrae, but an increase in their number. ''Elasmosaurus

''Elasmosaurus'' (;) is a genus of plesiosaur that lived in North America during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, about 80.5million years ago. The first specimen was discovered in 1867 near Fort Wallace, Kansas, US, and was se ...