Neocommunist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eurocommunism, also referred to as democratic communism or neocommunism, was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more relevant for Western Europe. During the

Eurocommunism, also referred to as democratic communism or neocommunism, was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more relevant for Western Europe. During the

The

The

Some communist parties with strong popular support, notably the PCI and the PCE, adopted Eurocommunism most enthusiastically. The SKP was dominated by Eurocommunists. In the 1980s, the traditional, pro-Soviet faction broke away, calling the main party revisionist. At least one mass party such as the PCF as well as many smaller parties strongly opposed to Eurocommunism and stayed aligned to the positions of the

Some communist parties with strong popular support, notably the PCI and the PCE, adopted Eurocommunism most enthusiastically. The SKP was dominated by Eurocommunists. In the 1980s, the traditional, pro-Soviet faction broke away, calling the main party revisionist. At least one mass party such as the PCF as well as many smaller parties strongly opposed to Eurocommunism and stayed aligned to the positions of the

Archive of Eurocommunism at marxists.org

by

Eurocommunism, also referred to as democratic communism or neocommunism, was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more relevant for Western Europe. During the

Eurocommunism, also referred to as democratic communism or neocommunism, was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more relevant for Western Europe. During the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, they sought to reject the influence of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

. The trend was especially prominent in Italy, Spain, and France.

Terminology

The origin of the term Eurocommunism was subject to great debate in the mid-1970s, being attributed to Zbigniew Brzezinski andArrigo Levi

Arrigo Levi (17 July 1926 – 24 August 2020) was an Italian journalist, essayist, and television anchorman.

Life Exile to Argentina

Levi was from a family of Jewish descent (his father Enzo was a renowned lawyer in Modena). In 1938, when he ...

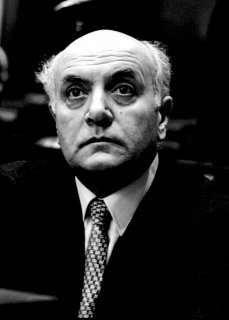

, among others. Jean-François Revel

Jean-François Revel (born Jean-François Ricard; 19 January 192430 April 2006) was a French philosopher, journalist, and author. A prominent public intellectual, Revel was a socialist in his youth but later became a prominent European propo ...

once wrote that "one of the favourite amusements of 'political scientists' is to search for the author of the term Eurocommunism". In April 1977, ''Deutschland Archiv'' decided that the word was first used in the summer of 1975 by Yugoslav journalist Frane Barbieri, former editor of Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

's '' NIN'' newsmagazine. Outside Western Europe, it is sometimes referred to as neocommunism. This theory stresses greater independence from the Soviet Union.

Background

Theoretical foundation and inspirations

According to Perry Anderson, the main theoretical foundation of Eurocommunism wasAntonio Gramsci

Antonio Francesco Gramsci ( , , ; 22 January 1891 – 27 April 1937) was an Italian Marxist philosopher, journalist, linguist, writer, and politician. He wrote on philosophy, political theory, sociology, history, and linguistics. He was a ...

's writing about Marxist theory

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew fro ...

which questioned the sectarianism of the left and encouraged communist parties to develop social alliances to win hegemonic support for social reforms. Early inspirations can also be found in Austro-Marxism

Austromarxism (also stylised as Austro-Marxism) was a Marxist theoretical current, led by Victor Adler, Otto Bauer, Karl Renner, Max Adler and Rudolf Hilferding, members of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria in Austria-Hungary and ...

and its seeking of a third democratic way to socialism.

Eurocommunist parties expressed their fidelity to democratic institutions more clearly than before and attempted to widen their appeal by embracing public sector middle-class workers, new social movements such as feminism and gay liberation and more publicly questioning the Soviet Union. However, Eurocommunism did not go as far as the Anglosphere-centred New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights, g ...

movement which had originally borrowed from the French , but in the course of the events went past their academic theorists, largely abandoning Marxist historical materialism, class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms ...

and its traditional institutions such as communist parties.

Legacy of the Prague Spring

The

The Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Sec ...

and particularly its crushing by the Soviet Union in 1968 became a turning point for the communist world. Romania's leader Nicolae Ceaușescu staunchly criticized the Soviet invasion in a speech, explicitly declaring his support for the Czechoslovakian leadership under Alexander Dubček. While the Portuguese Communist Party, the South African Communist Party and the Communist Party, USA supported the Soviet position, the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) firmly denounced the occupation. The leadership of the Communist Party of Finland (SKP), the Swedish Left Communist Party (VPK) and the French Communist Party (PCF) which had pleaded for conciliation expressed their disapproval about the Soviet intervention, with the PCF thereby publicly criticizing a Soviet action for the first time in its history. The Communist Party of Greece

The Communist Party of Greece ( el, Κομμουνιστικό Κόμμα Ελλάδας, ''Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas'', KKE) is a political party in Greece.

Founded in 1918 as the Socialist Labour Party of Greece and adopted its curren ...

(KKE) suffered a major split over the internal disputes regarding the Prague Spring, with the pro-Dubček faction breaking ties with the Soviet leadership and founding the KKE Interior

The Communist Party of Greece, Interior (), usually abbreviated as KKE Interior (Greek: ''ΚΚΕ Εσωτερικού''), was a Eurocommunist party existing between 1968 and 1987 in Greece.

The party was formed after the Communist Party of Greece ...

.

Early developments

Developments in Western European communist parties

Some communist parties with strong popular support, notably the PCI and the PCE, adopted Eurocommunism most enthusiastically. The SKP was dominated by Eurocommunists. In the 1980s, the traditional, pro-Soviet faction broke away, calling the main party revisionist. At least one mass party such as the PCF as well as many smaller parties strongly opposed to Eurocommunism and stayed aligned to the positions of the

Some communist parties with strong popular support, notably the PCI and the PCE, adopted Eurocommunism most enthusiastically. The SKP was dominated by Eurocommunists. In the 1980s, the traditional, pro-Soviet faction broke away, calling the main party revisionist. At least one mass party such as the PCF as well as many smaller parties strongly opposed to Eurocommunism and stayed aligned to the positions of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

until the end of the Soviet Union, although the PCF did make a brief turn toward Eurocommunism in the mid-to-late 1970s.

The PCE and its Catalan referent, the United Socialist Party of Catalonia, had already been committed to the liberal possibilist politics of the Popular Front during the Spanish Civil War. The PCE's leader Santiago Carrillo wrote Eurocommunism's defining book ('' Eurocommunism and the State'') and participated in the development of the liberal democratic constitution as Spain emerged from the dictatorship of Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

. The Communist Party of Austria, the Communist Party of Belgium, the Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPG ...

and the Communist Party of the Netherlands also turned Eurocommunist.

The PCI in particular had been developing an independent line from Moscow for many years prior which had already been exhibited in 1968, when the party refused to support the Soviet invasion of Prague. In 1975, the PCI and the PCE had made a declaration regarding the "march toward socialism" to be done in "peace and freedom". In 1976, the PCI's leader Enrico Berlinguer had spoken of a "pluralistic system" ( translated by the interpreter as "multiform system") in Moscow and in front of 5,000 communist delegates described the PCI's intentions to build "a socialism that we believe necessary and possible only in Italy". The Historic Compromise () with the Christian Democracy

Christian democracy (sometimes named Centrist democracy) is a political ideology that emerged in 19th-century Europe under the influence of Catholic social teaching and neo-Calvinism.

It was conceived as a combination of modern democratic ...

, stopped by the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro

The kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro ( it, Rapimento di Aldo Moro), also referred to in Italy as Moro Case ( it, Caso Moro), was a seminal event in Italian political history.

On the morning of 16 March 1978, the day on which the new cabine ...

in 1978, was a consequence of this new policy.

The SKP changed its leadership in 1965 with leadership post changing from the Stalinist

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory o ...

Aimo Aaltonen

Aimo Anshelm Aaltonen (10 December 1906 – 21 September 1987) was a Finnish construction worker and politician.

Aaltonen was born in Pargas. He became a communist as a young man and went to the Soviet Union in 1930, where he studied from 1930 t ...

, who had even a picture of Lavrentiy Beria in his office, to a revisionist, quite popular trade unionist Aarne Saarinen

Aarne Armas Saarinen (5 December 1913 – 13 April 2004) was a Finnish politician and a trade union leader, who was a member of the Parliament of Finland for the People's Democratic League. He was also the leader of the Communist-led Construction ...

. The same happened even more drastically when the Finnish People's Democratic League also changed its leadership with the reformist Ele Alenius leading it. In 1968, these were the only parties to directly oppose the actions of the Soviet militarship in Prague in 1968, therefore the two organizations split ''de facto'' into two different parties, with one reformist and one hard-line Soviet. What was peculiar was that the youth wing was nearly completely Taistoist. Progress was hard to make as the party accorded that the Taistolaist strongly pro-Soviet movement named after their leader Taisto Sinisalo

Taisto Jalo Sinisalo (29 June 1926 – 26 March 2002) was a Finnish communist politician, MP of the SKDL (1962–1978), leader of the Communist Party of Finland’s hardline pro-Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet S ...

had equal rights of power in the party, although it was a minority and the vast majority of the party was Eurocommunist. In 1984, with a strong Eurocommunist majority the hard-line organizations were massively expelled from the already weakened party. Pro-Soviet hard-liners formed their own cover-organization called Democratic Movement. In 1990, the new Left Alliance integrated the parties, but Alenius chose not to be member of it because they also took hard-line Taistolaists.

Western European communists came to Eurocommunism via a variety of routes. For some, it was their direct experience of feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

and similar action while for others it was a reaction to the political events of the Soviet Union at the apogee of what Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

later called the Era of Stagnation. This process was accelerated after the events of 1968, particularly the crushing of the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Sec ...

. The politics of détente also played a part. With war less likely, Western communists were under less pressure to follow Soviet orthodoxy yet also wanted to engage with a rise in Western proletarian militancy such as Italy's Hot Autumn and Britain's Shop Stewards Movement.

Further development

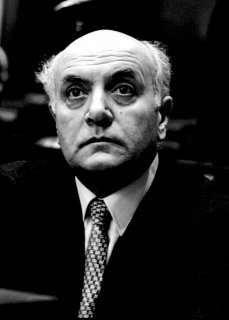

Eurocommunism was in many ways only a staging ground for changes in the political structure of the European left. Some, like the Italians, became social democrats while others, like the Dutch, moved into green politics and the French party during the 1980s reverted to a more pro-Soviet stance. Eurocommunism became a force across Europe in 1977, when the PCI's Enrico Berlinguer, the PCE's Santiago Carrillo and the PCF'sGeorges Marchais

Georges René Louis Marchais (7 June 1920 – 16 November 1997) was the head of the French Communist Party (PCF) from 1972 to 1994, and a candidate in the French presidential elections of 1981.

Early life

Born into a Roman Catholic family, he bec ...

met in Madrid and laid out the fundamental lines of the "new way".

Eurocommunist ideas won at least partial acceptance outside of Western Europe. Prominent parties influenced by it outside of Europe were the Communist Party of Australia, the Japanese Communist Party, the Mexican Communist Party and the Venezuelan Movement for Socialism

The Movement for Socialism–Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the Peoples ( es, Movimiento al Socialismo–Instrumento Político por la Soberanía de los Pueblos, abbreviated MAS-IPSP, or simply MAS, punning on ''más'', Spanish for ...

. Soviet leader

During its 69-year history, the Soviet Union usually had a ''de facto'' leader who would not necessarily be head of state but would lead while holding an office such as premier or general secretary. Under the 1977 Constitution, the chairman ...

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

also referred to Eurocommunism as a key influence on the ideas of glasnost

''Glasnost'' (; russian: link=no, гласность, ) has several general and specific meanings – a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information, the inadmissibility of hushing up problems, ...

and perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

in his memoirs.

Soviet dissolution

Thebreakup of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

and the end of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

put practically all leftist parties in Europe on the defensive and made neoliberal

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent fa ...

reforms the order of the day. Many Eurocommunist parties split, with the right factions (such as the Democrats of the Left or the Initiative for Catalonia Greens) adopting social democracy more whole-heartedly while the left strove to preserve some identifiably communist positions (the Communist Refoundation Party

The Communist Refoundation Party ( it, Partito della Rifondazione Comunista, PRC) is a communist political party in Italy that emerged from a split of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in 1991. The party's secretary is Maurizio Acerbo, who replac ...

or the PCE and the Living Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia

The Living Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia ( ca, PSUC viu, lit="Living PSUC") is a political party in Catalonia, Spain. PSUC viu emerged from factional fighting within the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSUC) in the mid-1990s. Since 19 ...

).

Criticism

Several criticisms have been advanced against Eurocommunism. First, it is alleged by critics that Eurocommunists showed a lack of courage in sufficiently and definitively breaking off from the Soviet Union (for example, the Italian Communist Party took this step only in 1981 after the repression of Solidarność in Poland). This timidity has been explained as the fear of losing old members and supporters, many of whom admired the Soviet Union, or with apragmatic

Pragmatism is a philosophical movement.

Pragmatism or pragmatic may also refer to:

*Pragmaticism, Charles Sanders Peirce's post-1905 branch of philosophy

*Pragmatics, a subfield of linguistics and semiotics

*''Pragmatics'', an academic journal in ...

desire to keep the support of a strong and powerful country.

Other critics point out the difficulties the Eurocommunist parties had in developing a clear and recognisable strategy. They observe that Eurocommunists have always claimed to be different—not only from Soviet communism, but also from social democracy—while in practice they were always very similar to at least one of these two tendencies. As a result, critics argue that Eurocommunism does not have a well-defined identity and cannot be regarded as a separate movement in its own right.

From a Trotskyist point of view in ''From Stalinism to Eurocommunism: The Bitter Fruits of 'Socialism in One Country'', Ernest Mandel views Eurocommunism as a subsequent development of the decision taken by the Soviet Union in 1924 to abandon the goal of world revolution and concentrate on social and economic development of the Soviet Union, the doctrine of socialism in one country. According to this vision, the Eurocommunists of the Italian and French communist parties are considered to be nationalist movements, who together with the Soviet Union abandoned internationalism.

From an anti-revisionist

Anti-revisionism is a position within Marxism–Leninism which emerged in the 1950s in opposition to the reforms of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Where Khrushchev pursued an interpretation that differed from his predecessor Joseph Stalin, ...

point of view, Enver Hoxha

Enver Halil Hoxha ( , ; 16 October 190811 April 1985) was an Albanian communist politician who was the authoritarian ruler of Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985. He was First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania from 1941 unt ...

argued in ''Eurocommunism is Anti-Communism'' that Eurocommunism is the result of Nikita Khrushchev's policy of peaceful coexistence. Khrushchev was accused of being a revisionist who encouraged conciliation with the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

rather than adequately calling for its overthrow by the dictatorship of the proletariat. He also stated that the Soviet Union's refusal to reject Palmiro Togliatti's theory of polycentrism

Polycentric is an English adjective, meaning "having more than one center," derived from the Greek words ''polús'' ("many") and ''kentrikós'' ("center"). Polycentricism (or polycentricity) is the abstract noun formed from polycentric. They may r ...

encouraged the various pro-Soviet communist parties to moderate their views in order to join cabinets

A cabinet is a body of high-ranking state officials, typically consisting of the executive branch's top leaders. Members of a cabinet are usually called cabinet ministers or secretaries. The function of a cabinet varies: in some countrie ...

which in turn forced them to abandon Marxism–Leninism as their leading ideology.

See also

* * * * * * *References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Archive of Eurocommunism at marxists.org

by

Enver Hoxha

Enver Halil Hoxha ( , ; 16 October 190811 April 1985) was an Albanian communist politician who was the authoritarian ruler of Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985. He was First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania from 1941 unt ...

{{authority control

Communism

Democratic socialism

Politics of Europe

Marxist schools of thought