Oktōēchos (here transcribed "Octoechos";

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: ; from

ὀκτώ "eight" and

ἦχος "sound, mode" called

echos

Echos (Greek: "sound", pl. echoi ; Old Church Slavonic: "voice, sound") is the name in Byzantine music theory for a mode within the eight-mode system ( oktoechos), each of them ruling several melody types, and it is used in the melodic and r ...

;

Slavonic: Осмогласие, ''Osmoglasie'' from

о́смь "eight" and

гласъ "voice, sound") is the name of the eight

mode

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

system used for the composition of religious chant in Byzantine, Syriac, Armenian, Georgian, Latin and Slavic churches since the Middle Ages. In a modified form the octoechos is still regarded as the foundation of the tradition of monodic Orthodox chant today.

From a

Phanariot

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots ( el, Φαναριώτες, ro, Fanarioți, tr, Fenerliler) were members of prominent Greek families in Phanar (Φανάρι, modern ''Fener''), the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople where the Ecumen ...

point of view, the re-formulation of the Octoechos and its melodic models according to the New Method was neither a simplification of the Byzantine tradition nor an adaption to Western tonality and its method of an heptaphonic

solfeggio, just based on one tone system (σύστημα κατὰ ἑπταφωνίαν). Quite the opposite, as a universal approach to music traditions of the Mediterranean it was rather based on the integrative power of the psaltic art and the

Papadike, which can be traced back to the

Hagiopolitan Octoechos

Oktōēchos (here transcribed ""; Greek: pronounced in koine: ; from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмогласие, ''Osmoglasie'' from о́смь "eight" and гласъ "voice, sound") is the n ...

and its exchange with Oriental music traditions since more than thousand years.

Hence, the current article is divided into three parts. The first is a discussion of the current solfeggio method based on seven syllables in combination with the invention of a universal notation system which transcribed the melos in the very detail (Chrysanthos' ''Theoretikon mega''). The second and third part are based on a theoretical separation between the ''exoteric'' and the ''esoteric'' use of modern or Neobyzantine notation. ''Exoteric'' (ἐξωτερική = "External") music meant the transcription of patriotic songs, opera arias, traditional music of the Mediterrean including Ottoman

makam

The Turkish makam ( Turkish: ''makam'' pl. ''makamlar''; from the Arabic word ) is a system of melody types used in Turkish classical music and Turkish folk music. It provides a complex set of rules for composing and performance. Each makam spec ...

and

Persian music Persian music may refer to various types of the music of Persia/Iran or other Persian-speaking countries:

* Persian traditional music

* Persian ritual music

*Persian pop music

* Persian symphonic music

* Persian piano music

See also

*Music of Ira ...

, while ''esoteric'' (ἐσωτερική = "internal") pointed at the papadic tradition of using Round notation with the modal signatures of the eight modes, now interpreted as a simple pitch key without implying any cadential patterns of a certain echos. In practice there had never been such a rigid separation between ''exoteric'' and ''esoteric'' among Romaic musicians, certain exchanges—with makam traditions in particular—were rather essential for the redefinition of Byzantine Chant, at least according to the traditional chant books published as "internal music" by the teachers of the New Music School of the Patriarchate.

Transcribing theseis of the melos and makam music

Unlike Western tonality and music theory the universal theory of the Phanariotes does not distinguish between

major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

and

minor scale

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which also ...

s, even if they transcribed Western polyphony into Byzantine neumes, and in fact, the majority of the models of the Byzantine Octoechos, as they are performed in

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

churches by traditional singers, would lose their proper intonation and expression, if they were played on a conventionally tuned piano. Exactly the familiarity with microtonal intervals was an advantage, which made the Chrysanthine or Neobyzantine notation as a medium of transmission more universal than any Western notation system. Among others even Western staff notation and Eastern neume notation had been used for transcriptions of

Ottoman classical music

Ottoman music ( tr, Osmanlı müziği) or Turkish classical music ( tr, Türk sanat müziği) is the tradition of classical music originating in the Ottoman Empire. Developed in the palace, major Ottoman cities, and Sufi lodges, it traditional ...

, despite their specific traditional background.

The transcription into the reform notation and its distribution by the first printed chant books were another aspect of the Phanariotes' universality. The first source to study the development of modern Byzantine notation and its translation of Papadic Notation is

Chrysanthos Chrysanthos ( el, Χρύσανθος), Latinized as Chrysanthus, is a Greek name meaning "golden flower". The feminine form of the name is Chrysanthe (Χρυσάνθη), also written Chrysanthi, Chrysanthy and Chrysanthea.

Notable people bearing t ...

' "Long Treatise of Music Theory". In 1821 only a small extract had been published as a manual for his reform notation, the Θεωρητικόν μέγα was printed later in 1832. Like the Papadic method, Chrysanthos described first the basic elements, the phthongoi, their intervals according to the genus, and how to memorise them by a certain solfeggio called "parallage." The thesis of the melos was part of the singers' performance and it included also the use of rhythm.

Chrysanthos' parallagai of the three genera (γένη)

In the early

Hagiopolitan Octoechos

Oktōēchos (here transcribed ""; Greek: pronounced in koine: ; from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмогласие, ''Osmoglasie'' from о́смь "eight" and гласъ "voice, sound") is the n ...

(6th-13th century) the diatonic echoi were destroyed by two phthorai

nenano

Phthora nenano (Medieval Greek: , also νενανώ) is the name of one of the two "extra" modes in the Byzantine Octoechos—an eight mode system, which was proclaimed by a synod of . The phthorai nenano and nana were favoured by composers at th ...

and

nana

Nana, Nanna, Na Na or NANA may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Nana (given name), including a list of people and characters with the given name

* Nana (surname), including a list of people and characters with the surname

* Nana ( ...

, which were like two additional modes with their own melos, but subordinated to certain diatonic echoi. In the period of

psaltic art (13th-17th century), changes between the diatonic, the chromatic, and the enharmonic genus became so popular in certain chant genres, that certain diatonic echoi of the Papadic Octoechos were coloured by the ''phthorai''—not only by the traditional Hagiopolitan ''phthorai,'' but also by additional phthorai, which introduced transition models assimilated to certain

makam

The Turkish makam ( Turkish: ''makam'' pl. ''makamlar''; from the Arabic word ) is a system of melody types used in Turkish classical music and Turkish folk music. It provides a complex set of rules for composing and performance. Each makam spec ...

intervals. After

Chrysanthos Chrysanthos ( el, Χρύσανθος), Latinized as Chrysanthus, is a Greek name meaning "golden flower". The feminine form of the name is Chrysanthe (Χρυσάνθη), also written Chrysanthi, Chrysanthy and Chrysanthea.

Notable people bearing t ...

' redefinition of Byzantine chant according to the New Method (1814), the scales of and of used intervals according to soft diatonic tetrachord divisions, while those of the and of the papadic had become enharmonic (φθορά νανά) and those of the chromatic (φθορά νενανῶ).

In his ''Mega Theoretikon'' (

vol. 1, book 3), Chrysanthos did not only discuss the difference to European concepts of the ''diatonic genus'', but also the other genera (''chromatic'' and ''enharmonic''), which had been refused in the treatises of Western music theory. He included Papadic forms of ''parallagai'', as they had been described in the article

Papadic Octoechos

Oktōēchos (here transcribed "Octoechos"; Greek: , pronounced in Constantinopolitan: ; from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмогласие, ''Osmoglasie'' from о́смь "eight" and гласъ " ...

, Western

solfeggio as well as another solfeggio taken from Ancient Greek harmonics. The differences between the ''diatonic,'' the ''chromatic,'' and ''enharmonic genus'' (gr. γένος) were defined by the use of

microtones

Microtonal music or microtonality is the use in music of microtones—intervals smaller than a semitone, also called "microintervals". It may also be extended to include any music using intervals not found in the customary Western tuning of tw ...

—more precisely by the question, whether intervals were either narrower or wider than the proportion of the Latin "semitonium," once defined by

Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandria ...

. His points of reference were the

equally tempered

An equal temperament is a musical temperament or tuning system, which approximates just intervals by dividing an octave (or other interval) into equal steps. This means the ratio of the frequencies of any adjacent pair of notes is the same, w ...

and to the

just intonation

In music, just intonation or pure intonation is the tuning of musical intervals

Interval may refer to:

Mathematics and physics

* Interval (mathematics), a range of numbers

** Partially ordered set#Intervals, its generalization from numbers to ...

, as it had been used since the Renaissance period, and the Pythagorean intonation, as it has been used in the diatonic genus of the Carolingian Octoechos since the Middle Ages.

Parallage of the diatonic genus

Chrysanthos Chrysanthos ( el, Χρύσανθος), Latinized as Chrysanthus, is a Greek name meaning "golden flower". The feminine form of the name is Chrysanthe (Χρυσάνθη), also written Chrysanthi, Chrysanthy and Chrysanthea.

Notable people bearing t ...

already introduced his readers into the ''

diatonic genus

In the musical system of ancient Greece, genus (Greek: γένος 'genos'' pl. γένη 'genē'' Latin: ''genus'', pl. ''genera'' "type, kind") is a term used to describe certain classes of intonations of the two movable notes within a tetracho ...

'' and its ''phthongoi'' in the 5th chapter of the first book, called "About the ''parallage'' of the diatonic genus" (Περὶ Παραλλαγῆς τοῦ Διατονικοῦ Γένους). In the 8th chapter he demonstrates, how the intervals can be found on the keyboard of the

tambur

The ''tambur'' (spelled in keeping with TDK conventions) is a fretted string instrument of Turkey and the former lands of the Ottoman Empire. Like the ney, the armudi (lit. pear-shaped) kemençe and the kudüm, it constitutes one of the fou ...

.

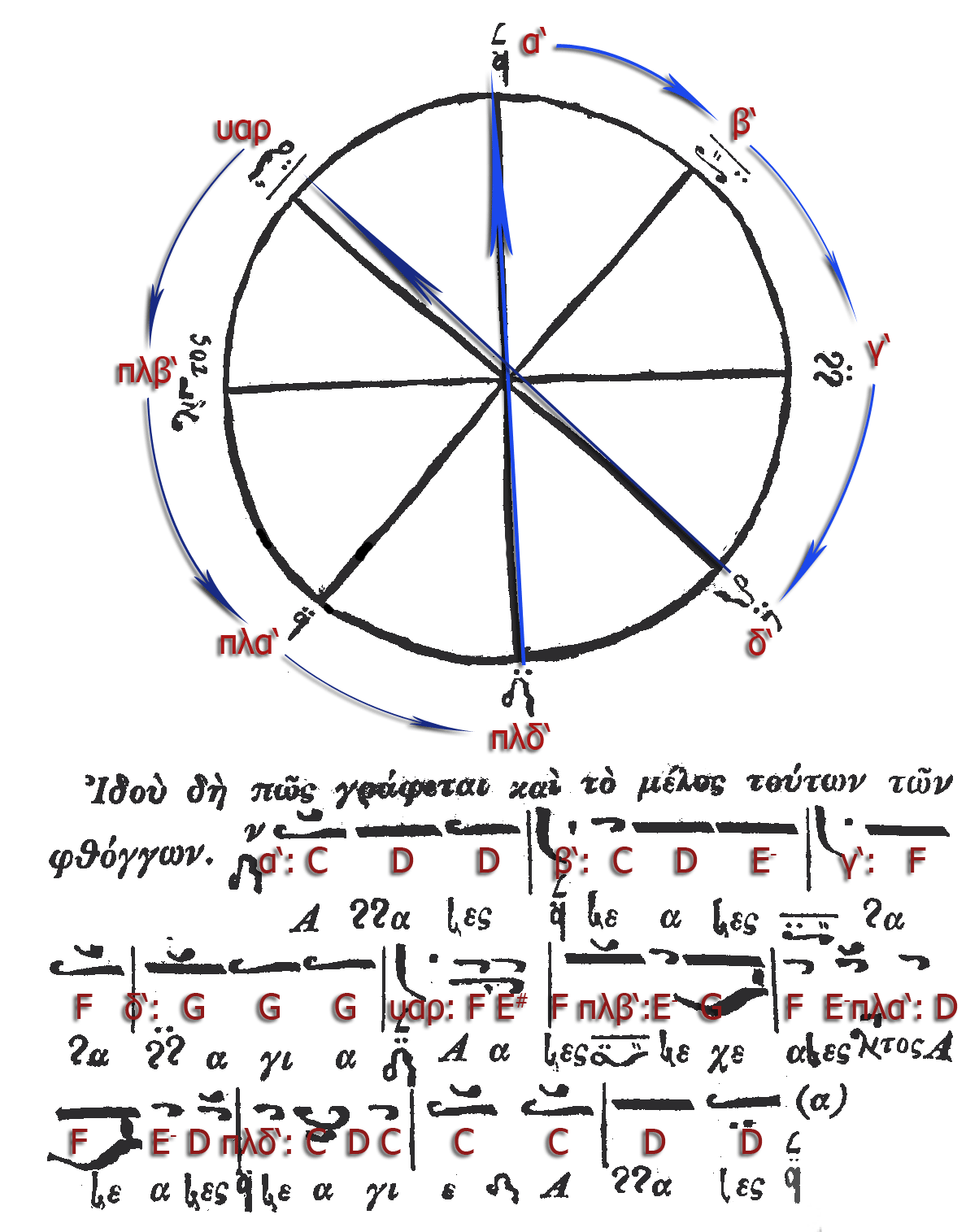

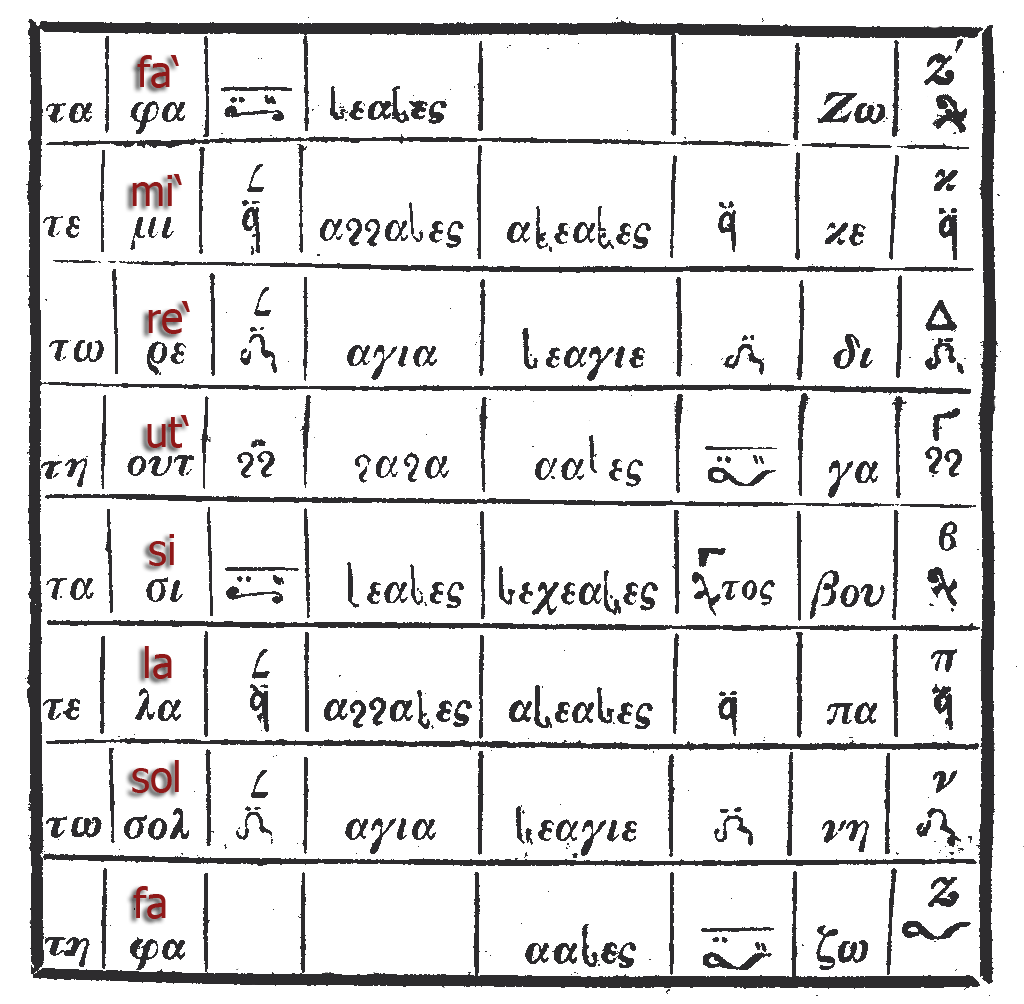

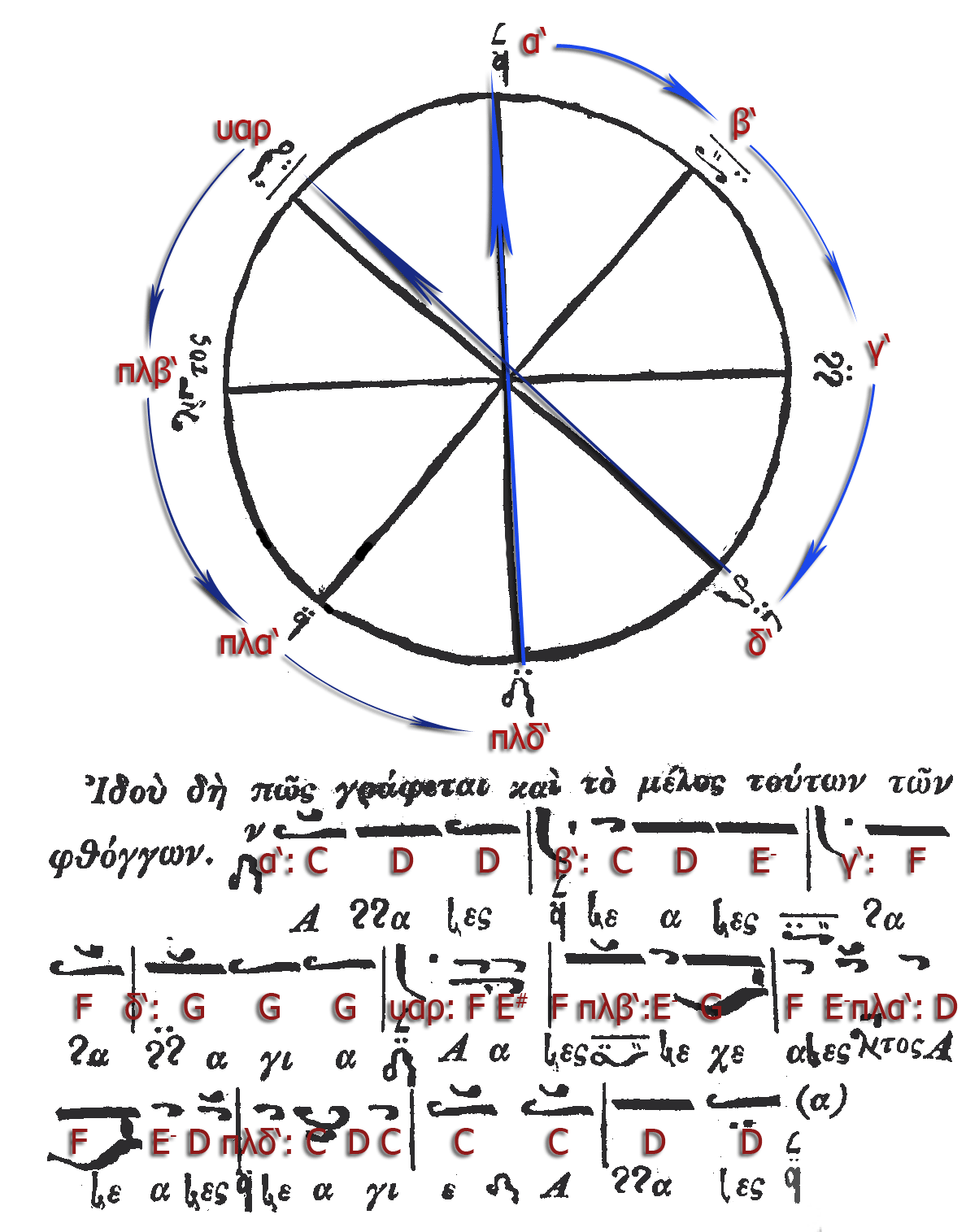

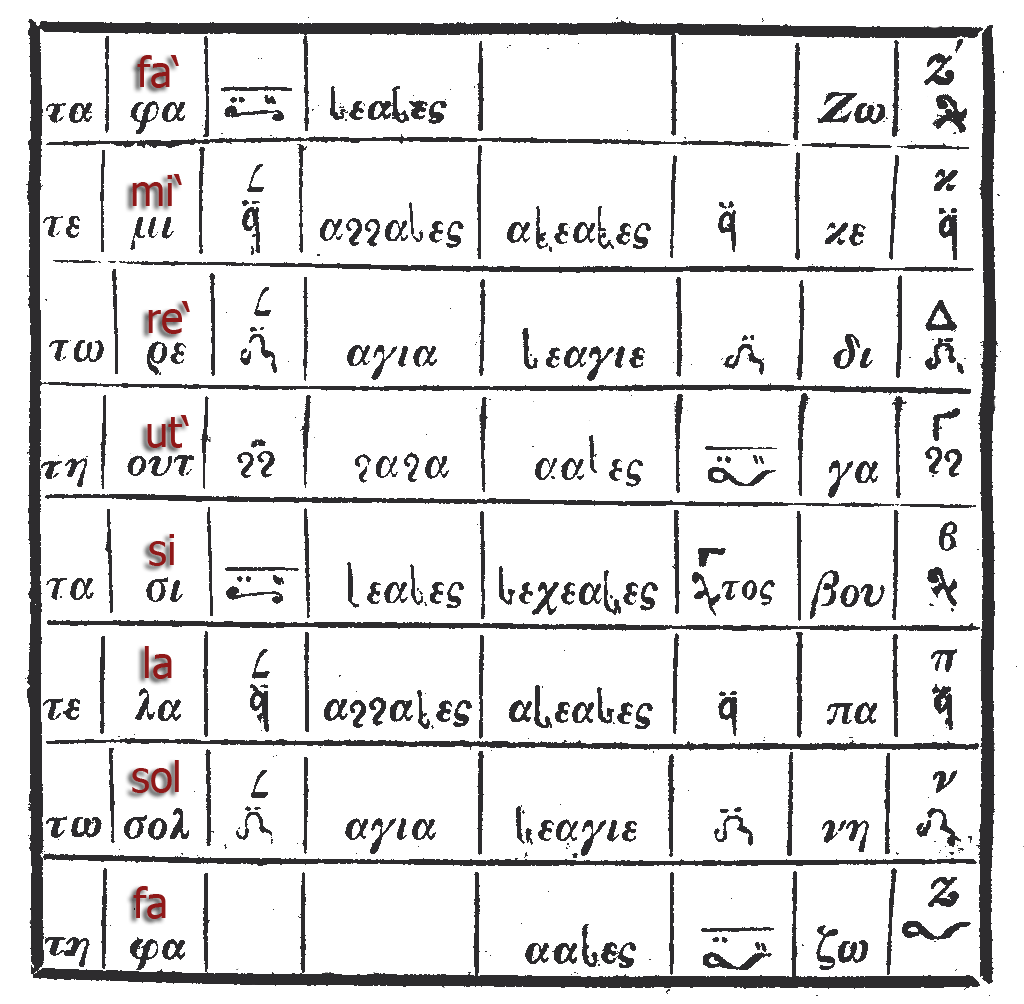

Hence, the ''phthongoi'' of the ''diatonic genus'' had been defined according to the proportions, as they were later called the "soft chroa of the diatonic genus" (τὸ γένος μαλακὸν διατονικὸν). For Chrysanthos this was the only diatonic genus, as far as it had been used since the early church musicians, who memorised the ''phthongoi'' by the intonation formulas (''enechemata'') of the Papadic Octoechos. In fact, he did not use the historical intonations, he rather translated them in the Koukouzelian wheel in the 9th chapter (Περὶ τοῦ Τροχοῦ) according to a current practice of parallage, which was common to 18th-century versions of ''Papadike'', while he identified another chroa of the diatonic genus with a practice of ancient Greeks:

Τὸ δὲ Πεντάχορδον, τὸ ὁποῖον λέγεται καὶ Τροχὸς, περιέχει διαστήματα τέσσαρα, τὰ ὁποῖα καθ᾽ ἡμᾶς μὲν εἶναι τόνοι· κατὰ δὲ τοὺς ἀρχαίους ἕλληνας, τὰ μὲν τρία ἦσαν τόνοι· καὶ τὸ ἕν λεῖμμα. Περιορίζονται δὲ τὰ τέσσαρα διαστήματα ταῦτα ἀπὸ φθόγγους πέντε.

πα βου γα δι Πα, καθ᾽ ἡμᾶς·

κατὰ δὲ τοὺς ἀρχαίους τε τα τη τω Τε.

The pentachord which was also called wheel (τροχὸς), contains four intervals which we regard as certain tones ��λάσσων τόνος, ἐλάχιστος τόνος, and 2 μείζονες τόνοι but according to the ancient Greeks they had been three whole tones μείζονες τόνοιand the difference leimma 56:243 The four intervals spanned five phthongoi:

πα βου γα δι Πα Πα" means here the fifth-equivalent for the protos: α'for us,

but according to the ancient (Greeks) τε τα τη τω Τε.

In Chrysanthos' version of the wheel the Middle Byzantine modal signatures had been replaced by alternative signatures which were still recognised by ''enechemata'' of the former parallage, and these signatures were important, because they formed a part of the modal signatures (') used in Chrysanthos reform notation. These signs had to be understood as ''dynameis'' within the context of the pentachord and the principle of '. According to Chrysanthos' signatures (see his kanonion) the ' of ' and ' were represented by the modal signature of their ''kyrioi'', but without the final ascending step to the upper fifth, the ''tritos'' signature was replaced by the signature of ''

phthora nana'', while the signature of ' (which was no longer used in its diatonic form) had been replaced by the ''enechema'' of the ', the so-called "" (ἦχος λέγετος) or former ἅγια νεανὲς, according to the New Method the ''heirmologic melos'' of the '.

In the table at the end of the trochos chapter, it becomes evident, that Chrysanthos was quite aware of the discrepancies between his adaption to the Ottoman

tambur

The ''tambur'' (spelled in keeping with TDK conventions) is a fretted string instrument of Turkey and the former lands of the Ottoman Empire. Like the ney, the armudi (lit. pear-shaped) kemençe and the kudüm, it constitutes one of the fou ...

frets which he called ''diapason'' (σύστημα κατὰ ἑπταφωνίαν), and the former Papadic ''parallage'' according to the trochos system (σύστημα κατὰ τετραφωνίαν), which was still recognised as the older practice. And later in the fifth book he emphasised that the great harmony of Greek music comes by the use of four tone systems (diphonia, triphonia, tetraphonia, and heptaphonia), while European and Ottoman musicians used only the heptaphonia or diapason system:

Ἀπὸ αὐτὰς λοιπὸν ἡ μὲν διαπασῶν εἶναι ἡ ἐντελεστέρα, καὶ εἰς τὰς ἀκοὰς εὐαρεστοτέρα· διὰ τοῦτο καὶ τὸ Διαπασῶν σύστημα προτιμᾶται, καὶ μόνον εἶναι εἰς χρῆσιν παρὰ τοῖς Μουσικοῖς Εὐρωπαίοις τε καὶ Ὀθωμανοῖς· οἵ τινες κατὰ τοῦτο μόνον τονίζοθσι τὰ Μουσικά τῶν ὄργανα.

But among those, the diapason is the most perfect and it pleases more the ears than the others, hence, the diapason system is favored and the only one used by European and Ottoman musicians, so that they tune their instruments only according to this system.

Until the generation of traditional protopsaltes who died during the 1980s, there were still traditional singers who intoned the Octoechos according to the ''trochos system'' (columns 3–6), but they did not intone the ' according to Pythagorean tuning, as Chrysanthos imagined it as a practice of the Ancient Greeks and identified it as a common European practice (first column in comparison with Western

solfeggio in the second column).

In the last column of his table, he listed the new modal signatures or ''matyriai of the phthongoi'' (μαρτυρίαι "witnesses"), as he introduced them for the use of his reform notation as a kind of pitch class system. These ''marytyriai'' had been composed by a thetic and a dynamic sign. The ''thetic'' was the first letter of Chrysanthos monosyllable parallage, the ''dynamic'' was taken from 5 signs of the eight ''enechemata'' of the ''trochos''. The four of the descending ''enechemata'' (πλ α', πλ β', υαρ, and πλ δ'), and the ''phthora nana'' (γ'). Thus, it was still possible to refer to the ''tetraphonia'' of the ''trochos system'' within the ''heptaphonia'' of Chrysanthos' ''parallage'', but there was one exception: usually the νανὰ represented the tritos element, while the varys-sign (the ligature for υαρ) represented the ζω (b natural)—the ''plagios tritos'' which could no longer establish a pentachord to its ''kyrios'' (like in the old system represented by Western solfeggio between B fa and F ut'), because it had been diminished to a slightly augmented tritone.

The older polysyllable parallage of the ''trochos'' was represented between the third and the sixth column. The third column used the "old" modal signatures for the ascending ''kyrioi echoi'' according to Chrysanthos' annotation of the ''trochos'', as they became the main signatures of the reform notation. The fourth column listed the names of their ''enechemata'', the fifth column the names of the ''enechemata'' of the descending ' together with their signatures in the sixth column.

In the 5th chapter "about the ''parallage'' of the diatonic genus", he characterised both ''parallagai'', of the Papadike and of the New Method, as follows:

§. 43. Παραλλαγὴ εἶναι, τὸ νὰ ἑφαρμόζωμεν τὰς συλλαβὰς τῶν φθόγγων ἐπάνω εἰς τοὺς ἐγκεχαραγμένους χαρακτῆρας, ὥστε βλέποντες τοὺς συντεθειμένους χαρακτῆρας, νὰ ψάλλωμεν τοὺς φθόγγους· ἔνθα ὅσον οἱ πολυσύλλαβοι φθόγγοι ἀπομακρύνονται τοῦ μέλους, ἄλλο τόσον οἱ μονοσύλλαβοι ἐγγίζουσιν ἀυτοῦ. Διότι ὅταν μάθῃ τινὰς νὰ προφέρῃ παραλλακτικῶς τὸ μουσικὸν πόνημα ὀρθῶς, ἀρκεῖ ἠ ἀλλάξῃ τὰς συλλαβὰς τῶν φθόγγων, λέγων τὰς συλλαβὰς τῶν λέξεων, καὶ ψάλλει αὐτὸ κατὰ μέλος.

Parallage is to apply the syllables of the phthongoi according to the steps indicated by the phonic neumes, so that we sing the ''phthongoi'' while we look at the written neumes. Note, that the more the polysyllabic ''phthongoi'' lead away from the melos ecause the thesis of the melos has still to be done the more go the monosyllable ''phthongoi'' with the melos. Once a musical composition has been studied thoroughly by the use of ''parallage'', it is enough to replace the syllables of the ''phthongoi'' by those of the text, and thus, we sing already its melos.

The disadvantage of the Papadic or "polysyllabic parallage" was, that ''metrophonia'' (its application to the phonic neumes of a musical composition) led away from the melodic structure, because of the own gesture of each modal intonation (''enechema''), which already represents an ''echos'' and its models in itself. After the phonic neumes had been recognised by μετροφωνία, the appropriate method to do the thesis of the melos had to be chosen, before a reader could find the way to the composition's performance. This was no longer necessary with monosyllabic solfeggio or ''parallage'', because the thesis of the melos had been already transcribed into phonic neumes—the musician had finally become as ignorant as

Manuel Chrysaphes

Manuel Doukas Chrysaphes ( el, , ) was the most prominent Byzantine musician of the 15th century.

Life and works

A singer, composer, and musical theoretician, Manuel Chrysaphes was called "the New Koukouzeles" by his admirer, the Cretan compos ...

had already feared it during the 15th century.

Nevertheless, the ''diapason system'' (see table) had also changed the former tetraphonic disposition of the ''echoi'' according to the ''trochos system'', which organised the final notes of each kyrios-plagios pair in a pentachord which had always been a pure fifth. In this heptaphonic disposition, the ' is not represented, because it would occupy the ''phthongos'' of the ''plagios protos'' πα, but with a ''chromatic parallage'' (see below). The ' (δι) and ' (βου) have both moved to their ''mesos'' position.

The difference between the ''diapason'' and the ''trochos system'' corresponded somehow with the oral melos transmission of the 18th century, documented by the manuscripts and the printed editions of the "New Music School of the Patriarchate", and the written transmission of the 14th-century chant manuscripts (revised

heirmologia,

sticheraria, Akolouthiai, and

Kontakaria) which fit rather to the Octoechos disposition of the ''trochos system''. Chrysanthos' theory aimed to bridge these discrepancies and the "exegetic transcription" or translation of late Byzantine notation into his notation system. This way the "exegesis" had become an important tool to justify the innovations of the 18th century within the background of the Papadic tradition of psaltic art.

G δι was still the ''phthongos'' for the finalis and basis of the ', the ἅγια παπαδικῆς, but E βου had become the finalis of the ''sticheraric, troparic'', and ''heirmologic melos'' of the same echos, and only the ''sticheraric melos'' had a second basis and intonation on the ''phthongos'' D πα.

Parallagai of the chromatic genus

The

phthora nenano and the tendency in psaltic art to

chromatize compositions since the 14th century had gradually substituted the diatonic models of the '. In psaltic treatises the process is described as the career of ' as an "" (κράτημα) which finally turned whole compositions of ' (ἦχος δεύτερος) and of the ' (ἦχος πλάγιος τοῦ δευτέρου) into the chromatic genus and the melos of φθορά νενανῶ.

The two ''chroai'' can be described as the "soft chromatic genus", which has developed from the ', and the "hard chromatic genus" as the proper ' which follows the protos parallage and changed its tetrachord from E—a to D—G.

;The soft chromatic scale of and its diphonic tone system

It found its most odd definition in Chrysanthos' ''Mega Theoretikon'', because he diminished the whole octave about 4 divisions in order to describe ' as a mode which has developed its own diphonic tone system (7+12=19). Indeed, its parallage is indefinite and in this particular case the ' has no direction, instead the direction is defined by the ''diatonic'' intonations of ':

§. 244. Ἡ χρωματικὴ κλίμαξ νη �α ὕφεσιςβου γα δι �ε ὕφεσιςζω Νη σχηματίζει ὄχι τετράχορδα, ἀλλὰ τρίχορδα πάντῃ ὅμοια καὶ συνημμένα τοῦτον τὸν τρόπον·

:νη �α ὕφεσιςβου, βου γα δι, δι �ε ὕφεσιςζω, ζω νη Πα.

Αὕτη ἡ κλίμαξ ἀρχομένη ἀπὸ τοῦ δι, εἰμὲν πρόεισιν ἐπὶ τὸ βαρὺ, θέλει τὸ μὲν δι γα διάστημα τόνον μείζονα· τὸ δὲ γα βου τόνον ἐλάχιστον· τὸ δὲ βου πα, τόνον μείζονα· καὶ τὸ πα νη, τόνον ἐλάχιστον. Εἰδὲ πρόεισιν ἐπὶ τὸ ὀξὺ, θέλει τὸ μὲν δι κε διάστημα τόνον ἐλάχιστον· τὸ δὲ κε ζω, τόνον μείζονα· τὸ δὲ ζω νη, τόνον ἐλάχιστον· καὶ τὸ νη Πα, τόνον μείζονα. Ὥστε ταύτης τῆς χρωματικῆς κλίμακος μόνον οἱ βου γα δι φθόγγοι ταὐτίζονται μὲ τοὺς βου γα δι φθόγγους τῆς διατονικῆς κλίμακος· οἱ δὲ λοιποὶ κινοῦνται. Διότι τὸ βου νη διάστημα κατὰ ταύτην μὲν τὴν κλίμακα περιέχει τόνους μείζονα καὶ ἐλάχιστον· κατὰ δὲ τὴν διατονικὴν κλίμακα περιέχει τόνους ἐλάσσονα καὶ μείζονα· ὁμοίως καὶ τὸ δι ζω διάστημα.

The chromatic scale C νη— flat��E βου—F γα—G δι— flat��b ζω'—c νη' is not made of tetrachords, but of trichords which are absolutely equal and conjunct with each other—in this way:

:C νη— flat��E βου, E βου—F γα—G δι, G δι— flat��b ζω', b ζω'—c νη'—d πα'

If the scale starts on G δι, and it moves towards the lower, the step G δι—F γα requests the interval of a great tone (μείζων τόνος) and the step F γα—E βου a small tone (ἐλάχιστος τόνος); likewise the step E βου— flatπα ��φεσιςan interval of μείζων τόνος, and the step πα ��φεσις flat��C νη one of ἐλάχιστος τόνος. When the direction is towards the higher, the step G δι— flatκε ��φεσιςrequests the interval of a small tone and flatκε ��φεσις��b ζω' that of a great tone; likewise the step b ζω'—c νη' an interval of ἐλάχιστος τόνος, and the step c νη'—Cd πα one of μείζων τόνος. Among the ' of this chromatic scale only the ' βου, γα, and δι can be identified with the same ' of the diatonic scale, while the others are moveable degrees of the mode. While this scale extends between E βου and C νη over one great and one small tone 2+7=19 the diatonic scale extends from the middle (ἐλάσσων τόνος) to the great tone (μείζων τόνος) 2+9=21 for the interval between G δι and b ζω' it is the same.

In this ''chromatic genus'' there is a strong resemblance between the ' G δι, the ', and b ζω', the ', but as well to E βου or to C νη. The trichordal structure (σύστημα κατὰ διφωνίαν) is nevertheless memorised with a soft chromatic

nenano

Phthora nenano (Medieval Greek: , also νενανώ) is the name of one of the two "extra" modes in the Byzantine Octoechos—an eight mode system, which was proclaimed by a synod of . The phthorai nenano and nana were favoured by composers at th ...

intonation around the small tone and the ''enechema'' of ἦχος δεύτερος in the ascending parallage and the ' of ἦχος λέγετος as ἦχος πλάγιος τοῦ δευτέρου in the descending parallage.

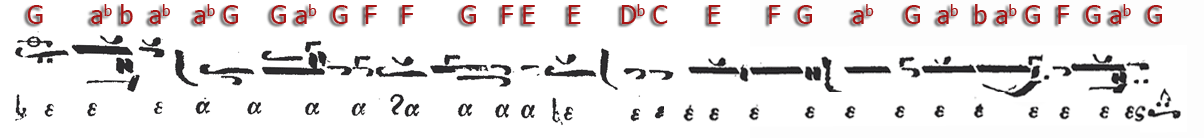

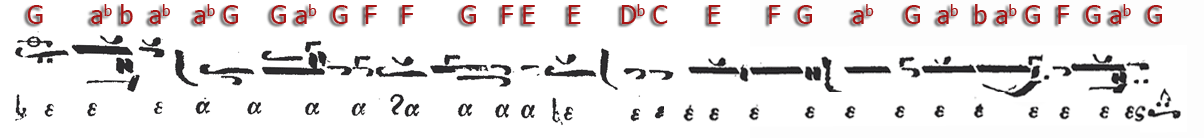

According to Chrysanthos, the old ''enechema'' for the ''diatonic '' on b ζω' was preserved by traditional singers as the ''chromatic mesos'', which he transcribed by the following exegesis. Please note the soft chromatic phthora at the beginning:

It can be argued that Chrysanthos' concept of the ' was not chromatic at all, but later manuals replaced his concept of ''diatonic diphonia'' by a concept of ''chromatic tetraphonia'' similar to the ', and added the missing two divisions to each pentachord, so that the octave of this echos C νη—G δι—c νη' was in tune (C νη—G δι, G δι—d πα': , 7 + 14 + 7, + 12 = 40). Also this example explains an important aspect of the contemporary concept of exegesis.

;The hard chromatic and mixed scale of

If we remember that the

φθορά νενανῶ originally appeared between βου (πλ β'), the phthongos of ' (ἦχος πλάγιος τοῦ δευτέρου), and κε (α'), the phthongos of ' (ἦχος πρῶτος), we are not so surprised, when we read, that the hard chromatic scale uses the same names during its ''parallage'' as the ''parallage'' of ἦχος δεύτερος:

§. 247. Τὴν δὲ Β κλίμακα πα �ου ὕφεσις �α δίεσιςδι κε �ω ὕφεσις �η δίεσιςΠα, μὲ τοὺς αὐτοὺς μὲν φθόγγους ψάλλομεν, καὶ ἡ μελῳδία τοῦτων μὲ τοὺς αὐτοὺς χαρακτῆρας γράφεται· ὅμως οἱ φθόγγοι φυλάττουσι τὰ διαστήματα, ἅτινα διωρίσθησαν (§. 245.).

We sing with the same ' ere the same names for the notes as memorial placesthe second hromaticscale: D πα— igh E flat�� igh F sharp��G δι—a κε— igh b flat�� igh c sharp��d πα', and their melody is written with the same phonic neumes. Nevertheless the phthongoi preserve the intervals as written in § 245.

Without any doubt the ''hard chromatic phthongoi'' use the chromaticism with the enharmonic hemitone of the intonation νενανῶ, so in this case the ''chromatic parallage'' gets a very clear direction, that the diphonic tone system does not have:

§. 245. Ἡ χρωματικὴ κλίμαξ, πα �ου ὕφεσις �α δίεσιςδι κε �ω ὕφεσις �η δίεσιςΠα, σύγκειται ἀπὸ δύο τετράχορδα· ἐν ἑκατέρῳ δὲ τετραχόρδῳ κεῖνται τὰ ἡμίτονα οὕτως, ὥστε τὸ διάστημα πα βου εἶναι ἴσον μὲ τὸ κε ζω· τὸ δὲ βου γα εἶναι ἴσον μὲ τὸ ζω νη· καὶ τὸ γα δι εἶναι ἴσον μὲ τὸ νη Πα· καὶ ὅλον τὸ πα δι τετράχορδον εἶναι ἴσον μὲ τὸ κε Πα τετράχορδον. Εἶναι δὲ τὸ μὲν πα βου διάστημα ἴσον ἐλαχιστῳ τόνῳ· τὸ δὲ βου γα, τριημιτόνιον· καὶ τὸ γα δι, ἡμιτόνιον· ἤγουν ἴσον 3:12.

The chromatic scale: D πα— igh E flat�� igh F sharp��G δι—a κε— igh b flat�� igh c sharp��d πα', consists of two tetrachords. In each tetrachords the hemitones are placed in a way, that the interval D πα—E βου ��φεσιςis the same as a κε—b ζω' ��φεσις Ε βου ��φεσις��F sharp γα �ίεσιςis the same as b ζω' ��φεσις��c sharp νη' �ίεσις and F sharp γα �ίεσις��G δι is the same as c sharp νη' �ίεσις��d πα', so that both tetarchords, D πα—G δ and a κε—d πα', are unisono. This means that the interval D πα—E βου ��φεσιςis unisono with the small tone (ἐλάχιστος τόνος), Ε βου ��φεσις��F sharp γα �ίεσιςwith the trihemitone, and F sharp γα �ίεσις��G δι with the hemitone: 3:12—a quarter of the great tone (μείζων τόνος) +18+3=28

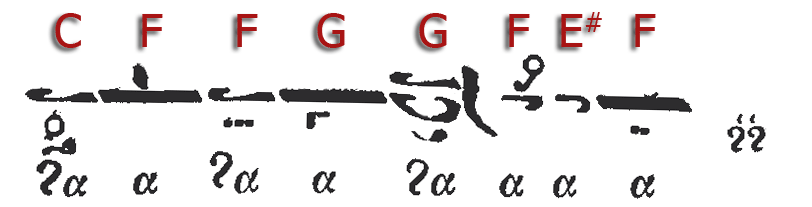

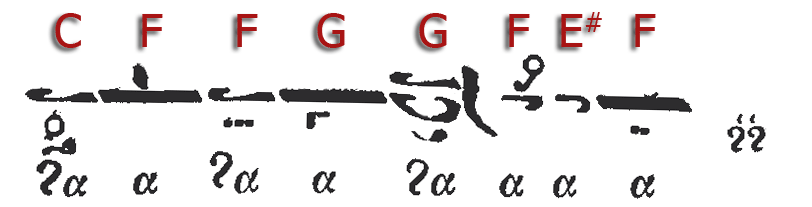

The shift of ' from the ' to the ' was explained by Chrysanthos through the exegesis of the Papadic ' intonation. Please note the hard chromatic phthorai, the second in the text line had been taken from the papadic ':

Despite this pure chromatic form, the ' in the ''sticheraric'' and ' is the only echos of the Octoechos which combines as well and in a temporary change of genus (μεταβολή κατὰ γένος) two different ''genera'' within the two tetrachords of the protos octave, while the diatonic tetrachord lies between δ' and γ' (a triphonic construction πλα'—δ'—γ'), and has the melos of ' (as shown in the mixed example of its ''parallage''). As could already studied in the ''

parallage of Ioannis Plousiadinos'', the same chromatic tetrachord could be as well that of the (πλα'—δ') like in the older ''enechemata'' of '. The other mixed form, though rare, was the combination of

phthora nenano on the protos parallage (α' κε—δ' πα') with a diatonic protos pentachord under it (πλ α' πα—α' κε).

Enharmonic genos and triphonia of phthora nana

According to the definition of

Aristides Quintilianus Aristides Quintilianus (Greek: Ἀριστείδης Κοϊντιλιανός) was the Greek author of an ancient musical treatise, ''Perì musikês'' (Περὶ Μουσικῆς, i.e. ''On Music''; Latin: ''De Musica'')

According to Theodore Kar ...

, quoted in the seventh chapter of the third book (περὶ τοῦ ἐναρμονίου γένους) in

Chrysanthos' ''Mega Theoretikon'', "enharmonic" is defined by the smallest interval, as long as it is not larger than a quarter or a third of the great tone (μείζων τόνος):

§. 258. Ἁρμονία δὲ λέγεται εἰς τὴν μουσικὴν τὸ γένος ὅπερ ἔχει εἰς τὴν κλίμακά του διάστημα τεταρτημορίου τοῦ μείζονος τόνου· τὸ δὲ τοιοῦτον διάστημα λέγεται ὕφεσις ἢ δίεσις ἐναρμόνιος· καθὼς καὶ δίεσις χρωματικὴ λέγεται τὸ ἥμισυ διάστημα τοῦ μείζονος τόνου. Ἐπειδὴ δὲ ὁ ἐλάχιστος τόνος, λογιζόμενος ἴσος 7, διαιρούμενος εἰς 3 καὶ 4, δίδει τεταρτημόριον καὶ τριτημόριον τοῦ μείζονος τόνου, ἡμεῖς ὅταν λάβωμεν ἓν διάστημα βου γα, ἴσον 3, εὑρίσκομεν τὴν ἐναρμόνιον δίεσιν· τὴν ὁποίαν μεταχειριζόμενοι εἰς τὴν κλίμακα, ἐκτελοῦμεν τὸ ἐναρμόνιον γένος· διότι χαρακτηρίζεται, λέγει ὁ Ἀριστείδης, τὸ ἐναρμόνιον γένος ἐκ τῶν τεταρτημοριαίων διέσεων τοῦ τόνου.

In music, the genus is called "harmony" which has the interval of a quarter great tone (μείζων τόνος) in its scale, and such an interval is called the "enharmonic" hyphesis or diesis, while the diesis with an interval about half of a great tone is called "chromatic". Since the small tone (ἐλάχιστος τόνος) is considered equal to 7 parts, the difference about 3 or 4, which makes a quarter or a third of the great tone, and the interval E βου—F γα, equal to 3, can be found through the enharmonic diesis; this applied to a scale, realizes the enharmonic genus. Aristeides said, that the enharmonic genus was characterised by the diesis about a quarter of a whole tone.

But the difference about 50 cents already made the difference between the small tone (ἐλάχιστος τόνος) and the Western ''semitonium'' (88:81=143 C', 256:243=90 C'), so it did not only already appear in the ''hard chromatic genos'', but also in the Eastern use of ''dieses'' within the ''diatonic genus'' and in the definition of the ''diatonic genus'' in Latin chant treatises. Hence, several manuals of Orthodox Chant mentioned that the ''enharmonic'' use of intervals had been spread over all different ''genera'' (Chrysanthos discussed these differences within the ''genus'' as "chroa"), but several

Phanariotes

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots ( el, Φαναριώτες, ro, Fanarioți, tr, Fenerliler) were members of prominent Greeks, Greek families in Fener, Phanar (Φανάρι, modern ''Fener''), the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople whe ...

defined this general phenomenon by the use of the word "harmony" (ἁρμονία) which was the Greek term for music and contrasted it with the modern term "music" (μουσική) which had been taken from Arabic, usually to make a difference between the reference to ancient Greek music theory and the autochthonous theory treating melody (''naġām'') and rhythm (''īqā′at''). According to the ancient Greek use, ἐναρμονίος was simply an adjective meaning "being within the music". In the discussion of the Euklidian term "chroa", he mentioned that the substitution of a ''semitonium'' by two ''dieses'' as it can be found in Western music, was "improper" (ἄτοπον) in Byzantine as well as in Ottoman art music, because it added one more element to the heptaphonic scale.

But Aristeides' definition also explained, why the enharmonic ' (also called ') had been defined in later manuals as "hard diatonic". The more characteristic change was less those of the genus (μεταβολή κατὰ γένος) than the one from the tetraphonic to the triphonic tone system (μεταβολή κατὰ σύστημα):

Διὰ τοῦτο ὅταν τὸ μέλος τοῦ ἐναρμονίου γένους ἄρχηται ἀπὸ τοῦ γα, θέλει νὰ συμφωνῇ μὲ τὸν γα ἡ ζω ὕφεσις, καὶ ὄχι ὁ νη φθόγγος. Καὶ ἐκεῖνο ὅπερ εἰς τὴν διατονικὴν καὶ χρωματικὴν κλίμακα ἐγίνετο διὰ τῆς τετραφωνίας, ἐδῶ γίνεται διὰ τῆς τριφωνίας

:νη πα �ου δίεσιςγα, γα δι κε �ω ὕφεσις−6 �ω ὕφεσις−6νη πα �ου ὕφεσις−6

Ὥστε συγκροτοῦνται καὶ ἐδῶ τετράχορδα συνημμένα ὅμοια, διότι ἔχουσι τὰ ἐν μέσῳ διαστήματα ἴσα· τὸ μὲν νη πα ἴσον τῷ γα δι· τὸ δὲ πα �ου δίεσις ἴσον τῷ δι κε· τὸ δὲ �ου δίεσιςγα, ἴσον τῷ κε �ω ὕφεσις−6� καὶ τὰ λοιπά.

Hence, if the melos of the enharmonic genus starts on F γα, F γα and b flat �ω' ὕφεσις−6should be symphonous, and not the phthongos c νη'. And like the diatonic and chromatic scales are made of tetraphonia, here they are made of triphonia:

:C νη—D πα—E sharp �ου δίεσις��F γα, F γα—G δι—a κε—b flat �ω' ὕφεσις−6 b flat �ω' ὕφεσις−6��c νη'—d πα'—e flat �ου' ὕφεσις−6

Thus, also conjunct similar tetrachords are constructed by the same intervals in the middle ''12+13+3=28 C νη—D πα is equal to F γα—G δι, D πα—E sharp �ου δίεσιςto G δι—a κε, E sharp �ου δίεσις��F γα is equal to a κε—b flat �ω' ὕφεσις−6 etc.

As can be already seen in the ''Papadikai'' of the 17th century, the ''diatonic'' intonation of ''echos tritos'' had been represented by the modal signature of the ''enharmonic

phthora nana''. In his chapter about the intonation formulas (περὶ ἁπηχημάτων) Chrysanthos does no longer refer to the diatonic intonation of ἦχος τρίτος, instead the ''echos tritos'' is simply an exegesis of the enharmonic '. Please note the use of the Chrysanthine ''phthora'' to indicate the small ''hemitonion'' in the ''final cadence'' of φθορά νανὰ in the interval γα—βου:

Because the pentachord between ''kyrios'' and ' did no longer exist in Chrysanthos' ''diapason system'', the ''enharmonic '' had only one ' in it, that between ' (πλ δ′) and ' (γ′). Hence, in the ''enharmonic genus'' of the ', there was no real difference between ἦχος τρίτος and ἦχος βαρύς. Hence, while there was an additional intonation needed for the ''diatonic varys'' on the ' B ζω, the ''protovarys'' which was not unlike the traditional ''diatonic '', the ''enharmonic'' exegesis of the traditional ''diatonic'' intonation of ἦχος βαρύς was as well located on the ' of ἦχος τρίτος:

Smallest tones (''hemitona'')

Chrysanthos' concept of "half tone" (ἡμίτονον) should not be mistaken with the Latin ''semitonium'' which he called λεῖμμα (256:243), it was rather flexible, as it can be read in his chapter "about hemitonoi" (περὶ ἡμιτόνων):

Τὸ Ἡμίτονον δὲν ἐννοεῖ τὸν τόνον διηρημένον ἀκριβῶς εἰς δύο, ὡς τὰ δώδεκα εἰς ἓξ καὶ ἓξ, ἀλλ᾽ ἀορίστως· ἤγουν τὰ δώδεκα εἰς ὀκτὼ καὶ τέσσαρα, ἢ εἰς ἐννέα καὶ τρία, καὶ τὰ λοιπά. Διότι ὁ γα δι τόνος διαιρεῖται εἰς δύο διαστήματα, ἀπὸ τὰ ὁποῖα τὸ μὲν ἀπὸ τοῦ ὀξέος ἐπὶ τὸ βαρὺ εἶναι τριτημόριον· τὸ δὲ ἀπὸ τοῦ βαρέος ἐπὶ τὸ ὀξὺ, εἶναι δύο τριτημόρια, καὶ τὰ λοιπά. Εἰναι ἔτι δυνατὸν νὰ διαιρεθῃ καὶ ἀλλέως· τὸ ἡμίτονον ὃμως τοῦ βου γα τόνου καὶ τοῦ ζω νη, εἶναι τὸ μικρότατον, καὶ δὲν δέχεται διαφορετικὴν διαίρεσιν· διότι λογίζεται ὡς τεταρτημόριον τοῦ μείζονος τόνου· ἤγουν ὡς 3:12.

..Καὶ τὸ λεῖμμα ἐκείνων, ἢ τὸ ἡμίτονον τῶν Εὐρωπαίων σι ουτ, εἶναι μικρότερον ἀπὸ τὸν ἡμέτερον ἐλάχιστον τόνον βου γα. Διὰ τοῦτο καὶ οἱ φθόγγοι τῆς ἡμετέρας διατονικῆς κλίμακος ἔχουσιν ἀπαγγέλίαν διάφορον, τινὲς μὲν ταὐτιζόμενοι, τινὲς δὲ ὀξυνόμενοι, καὶ τινες βαρυνόμενοι.

The hemitonon is not always the exact division into two halves like 12 into 6 and 6, it is less defined like the 12 into 8 and 4, or into 9 and 3 etc. So, the tonos γα δι �'—δ'is divided into two intervals: the higher one is one third, the lower two thirds etc. The latter might be divided again, while a hemitonon of the tonos βου γα and ζω νη �'—γ'cannot be further divided, because they are regarded as the quarter of the great tone, which is 3:12.

..And the leimma of those he Ancient Greekslike the "semitonium" si ut of the Europeans are smaller than our small tone (ἐλάχιστος τόνος) βου γα �'—γ' Hence, the elements (φθόγγοι) of our diatonic scale are intoned in a slightly different way, some are just the same t, re, fa, sol other are higher a, si bemolor lower i, si

Chrysanthos' definition of a Byzantine ''hemitonon'' is related with the introduction of accidental '. Concerning his own theory and the influence that it had on later theory, the accidental use of ' had two functions:

# the notation of melodic attraction as part of a certain ''melos'', which became important in the further development of modern Byzantine notation, especially within the school of

Simon Karas Simon Karas (3 June 1905 – 26 January 1999) was a Greek musicologist, who specialized in Byzantine music tradition.

Simon Karas studied paleography of Byzantine musical notation, was active in collecting and preserving ancient musical manu ...

.

# the notation of modified diatonic scales which became an important tool for the transcription of other modal traditions outside the Byzantine Octoechos (the so-called "exoteric music"), for instance folk music traditions or other traditions of Ottoman art music like the transcription of certain

makam

The Turkish makam ( Turkish: ''makam'' pl. ''makamlar''; from the Arabic word ) is a system of melody types used in Turkish classical music and Turkish folk music. It provides a complex set of rules for composing and performance. Each makam spec ...

lar.

The chroai and the notation of melodic attraction

The accidental ' had been used to notate details of melodic attraction, as ''dieseis'' in case of augmentation or ascending attraction or ' in case of diminution or descending attraction.

About the phenomenon of temporary attraction which did not cause a change into another genus (μεταβολή κατὰ γένος), although it caused a microtonal change, he wrote in his eight chapter "about the chroai" (περὶ χροῶν):

§. 265. Ἑστῶτες μὲν φθόγγοι εἶναι ἐκεῖνοι, τῶν ὁποίων οἱ τόνοι δὲν μεταπίπτουσιν εἰς τὰς διαφορὰς τῶν γενῶν, ἀλλὰ μένουσιν ἐπὶ μιᾶς τάσεως. Κινούμενοι δὲ ἢ φερόμενοι γθόγγοι εἲναι ἐκείνοι, τῶν ὁποίων οἱ τόνοι μεταβάλλονται εἰς τὰς διαφορὰς τῶν γενῶν, καὶ δὲν μένουσιν ἐπὶ μιᾶς τάσεως· ἣ, ὃ ταὑτὸν ἐστὶν, οἱ ποτὲ μὲν ἐλάσσονα, ποτὲ δὲ μείζονα δηλοῦντες τὰ διαστήματα, κατὰ τὰς διαφόρους συνθέσεις τῶν τετραχόρδων.

§. 266. Χρόα δὲ εἶναι εἰδικὴ διαίρεσις τοῦ γένους. Παρῆγον δὲ τὰς χρόας οἱ ἀρχαῖοι ἀπὸ τὴν διάφορον διαίρεσιν τῶν τετραχόρδων, ἀφήνοντες μὲν Ἑστῶτας φθόγγους τοῦς ἄκρους τοῦ τετραχόρδου· ποιοῦντες δὲ Κινουμένους τοὺς ἐν μέσῳ.

Fixed phthongoi called "ἑστῶτες", because they remain unaltered by the different genera, are always defined by one proportion ength of the chord Mobile phthongoi called "κινούμενοι", because they are altered by the different genera, are not defined by just one proportion; in other words, concerning the different divisions of the tetrachord their intervals are sometimes middle ones sometimes large ones.

"Chroa" is a particular division within a certain genus. The ancient reeksmade the "chroai" through the different divisions of the tetrachord by leaving the external phthongoi fixed (ἑστῶτες) and by moving the ones called "κινούμενοι".

As a reference for the ancient Greeks, Chrysanthos offer some examples of tetrachord divisions taken from

Euklid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of g ...

which creates subdivisions within the same genus. Chrysanthos does not comment on the different quality between the ' which have a particular shape for a specific division, on the one hand, and the accidental use of those ' which he introduced in the second chapter about ''hemitonoi'' (

footnote on p. 101), on the other hand. The accidental use of ' became later, in 1883, a subject of a synod, obviously the oral transmission of melodic attraction which differed between various local traditions, had been declined, after the abundant use of accidental ' in different printed editions had confused it.

Besides, the introduction of the accidental phthora did not change the notation very much. They were perceived by performers as an interpretation without any obligation to follow, because there were various local traditions which were used to an alternative use of melodic attraction in the different melodic models used within a certain ''echos''.

Only recently, during the 1990s, the reintroduction of abandoned late Byzantine neumes, re-interpreted into the context of the rhythmic Chrysanthine notation, had been also combined by a systematic notation of melodic attraction (μελωδικές ἕλξεις). This innovation had been already proposed by the Phanariot

Simon Karas Simon Karas (3 June 1905 – 26 January 1999) was a Greek musicologist, who specialized in Byzantine music tradition.

Simon Karas studied paleography of Byzantine musical notation, was active in collecting and preserving ancient musical manu ...

, but it was his student

Lykourgos Angelopoulos who used this ''dieseis'' and ''hypheseis'' in a systematic way to transcribe a certain local tradition of melodic attraction. But it was somehow the result of distinctions between the intervals used by Western and Byzantine traditions, which finally tempted the details of the notation used by Karas' school.

Transcription of makamlar

In the last chapter of his third book "Plenty possible chroai" (Πόσαι αἱ δυναταὶ Χρόαι), Chrysanthos used with the adjective δυνατή a term which was connected with the Aristotelian philosophy of

δύναμις (translated into Latin as "

contingentia"), i.e. the potential of being outside the cause (ἐνέργεια) of the Octoechos, something has been modified there and it becomes something completely different within the context of another tradition.

This is Chrysanthos' systematic lists of modifications (the bold syllable had been modified by a ''phthora—hyphesis'' or ''diesis'').

The first list is concerned about just one modification (-/+ 3):

It can be observed that the unmodified diatonic scale already corresponded to certain

makam

The Turkish makam ( Turkish: ''makam'' pl. ''makamlar''; from the Arabic word ) is a system of melody types used in Turkish classical music and Turkish folk music. It provides a complex set of rules for composing and performance. Each makam spec ...

lar, for instance ἦχος λέγετος (based on the ''ison'' E βου) corresponded to ''makam segâh''. Nevertheless, if the ' βου (already a slightly flattened E) had an accidental ' (ὕφεσις) as ', it corresponded to another ''makam'', very closely related to ''segâh'', but according to the particular use among Kurdish musicians who intoned this central degree of the ''makam'' even lower: it was called ''makam kürdî''. Concerning the ''genus, chromatic tetrachords'' can be found in the ''makamlar hicâz, sabâ'', and ''hüzzâm''.

A second list of scales gives 8 examples out of 60 possible chroai which contain 2 modifications, usually in the same direction (the bold syllable had been modified by 2 ''phthorai—hypheseis'' or ''dieseis'' about -/+ 3 divisions, if not indicated alternatively):

A third list gives "4 examples out of 160 possible " which have 3 modifications with respect to the diatonic scale:

Chrysanthos' approach had been only systematic with respect to the modification of the diatonic scale, but not with respect to the ''makamlar'' and its models (''seyirler''), as they had been collected by Panagiotes Halaçoğlu and his student Kyrillos Marmarinos who already transcribed into late Byzantine Round notation in their manuscripts. A systematic convention concerning ''exoteric phthorai'', how these models have to be transcribed according to the New Method, became the later subject of the treatises by Ioannis Keïvelis (

1856) and by Panagiotes Keltzanides (

1881).

Hence, the author of the ''Mega Theoretikon'' mode no efforts to offer a complete list of ''makamlar''. Remarks that ''makam arazbâr'' "is a kind of ' which has to be sung according to the trochos system", made it evident, that his tables have not been made in order to demonstrate, that a composition of makam arazbâr can always be transcribed by the use of the main signature of ''echos varys''. Nevertheless, the central treatise of the New Method already testified, that the reform notation as a medium of transcription had been designed as a universal notation, which could be used as well to transcribe other genres of Ottoman music than just Orthodox Chant as the Byzantine heritage.

Chrysanthos' theory of rhythm and of the octoechos

The question of rhythm is the most controversial and most difficult one and an important part of the Octoechos, because the method of how to do the thesis of the melos included not only melodic features like opening, transitional, or cadential formulas, but also their rhythmic structure.

In the third chapter about the performance concept of Byzantine chant ("Aufführungssinn"), Maria Alexandru discussed in her doctoral thesis rhythm already as an aspect of the ' of the cathedral rite (a gestic notation which had been originally used in the

Kontakaria, Asmatika, and Psaltika, before the Papadic synthesis). On the other hand, the New Method redefined the different genres according psalmody and according to the traditional chant books like ''

Octoechos mega'', now ''Anastasimatarion neon'', ''

Heirmologion

Irmologion ( grc-gre, τὸ εἱρμολόγιον ) is a liturgical book of the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite. It contains ''irmoi'' () organised in sequences of odes (, sg. ) and su ...

,

Sticherarion

A sticheron (Greek: "set in verses"; plural: stichera; Greek: ) is a hymn of a particular genre sung during the daily evening (Hesperinos/Vespers) and morning (Orthros) offices, and some other services, of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Cath ...

'', and the ''Papadike''—the treatise which preceded since the 17th century an Anthology which included a collection

Polyeleos The Polyeleos is a festive portion of the Matins or All-Night Vigil service as observed on higher-ranking feast days in the Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Lutheran, and Byzantine Rite Catholic Churches. The Polyeleos is considered to be the high point of ...

compositions, chant sung during the

Divine Liturgy

Divine Liturgy ( grc-gre, Θεία Λειτουργία, Theia Leitourgia) or Holy Liturgy is the Eucharistic service of the Byzantine Rite, developed from the Antiochene Rite of Christian liturgy which is that of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of C ...

(

Trisagia,

Allelouiaria,

Cherouvika,

Koinonika), but also a ''Heirmologion kalophonikon''. According to the New Method, every genre was defined now by the tempo and its formulaic repertory with respect to the

echos

Echos (Greek: "sound", pl. echoi ; Old Church Slavonic: "voice, sound") is the name in Byzantine music theory for a mode within the eight-mode system ( oktoechos), each of them ruling several melody types, and it is used in the melodic and r ...

, which formed a certain "exegesis type".

Hence, it is not a surprise that Chrysanthos in his ''Theoretikon mega'' treats rhythm and meter in the second book together with the discussion of the ''great signs'' or ''hypostaseis'' (περὶ ὑποστάσεων). The controversial discussion of the "syntomon style" as it had been created by Petros Peloponnesios and his student Petros Byzantios, was about rhythm, but the later rhythmic system of the New Method which had been created two generations later, had provoked a principle refuse of Chrysanthine notation among some traditionalists.

The new analytic use of Round notation established a direct relation of performance and rhythmic signs, which had already been a tabu since the 15th century, while the change of tempo was probably not an invention of the 19th century. At least since the 13th century, melismatic chant of the cathedral rite had been notated with abbreviations or ligatures (ἀργόν "slow") which presumably indicated a change to a slower tempo. Other discussions were about the quality of rhythm itself, if certain genres and its text had to be performed in a rhythmic or arhythmic way. In particular the knowledge of the most traditional and simple method had been lost.

Mediating between tradition and innovation, Chrysanthos had the characteristic Phanariot creativity. While he was writing about the metric feet (πώδαι) as rhythmic patterns or periods, mainly based on

Aristides Quintilianus Aristides Quintilianus (Greek: Ἀριστείδης Κοϊντιλιανός) was the Greek author of an ancient musical treatise, ''Perì musikês'' (Περὶ Μουσικῆς, i.e. ''On Music''; Latin: ''De Musica'')

According to Theodore Kar ...

and

Aristoxenos, he treated the ''arseis'' and ''theseis'' simultaneously with the Ottoman timbres ''düm'' and ''tek'' of the ''

usulümler'', and concluded, that only a very experienced musician can know, which are the rhythmic patterns that can be applied to a certain thesis of the melos. He analysed for instance the rhythmic periods as he transcribed them from Petros Peloponnesios' ''Heirmologion argon''.

Especially concerning the ethic aspect of music, melody as well as rhythm, Chrysanthos combined knowledge about ancient Greek music theory with his experience of the use of ''makamlar'' and ''usulümler'' in the ceremony of whirling dervishes. There was a collective ethos of rhythm, because the ceremony and its composition (''ayinler'') followed a strict sequence of ''usulümler'', which varied rarely and only slightly. There was a rather individual ethic concept for the combination of ''

makam

The Turkish makam ( Turkish: ''makam'' pl. ''makamlar''; from the Arabic word ) is a system of melody types used in Turkish classical music and Turkish folk music. It provides a complex set of rules for composing and performance. Each makam spec ...

lar'' (''tarqib''), which was connected with the individual constitution of the psyche and with the inspiration of an individual musician on the other side.

In the fifth book (chapt. 3: τωρινὸς τρόπος τοῦ μελίζειν "the contemporary way of chant",

pp. 181-192), he also wrote about a certain effect on the auditory that a well-educated musician is capable to create, and about contemporary types of musicians with different levels of education (the empiric, the artistic, and the experienced type). They are worth to be studied, because the role of notation in transmission becomes evident in Chrysanthos' description of the psaltes' competences. The ''empiric'' type did not know notation at all, but they knew the ''heirmologic melos'' by heart, so that they could apply it to any text, but sometimes they were sure if they repeated, what they wished repeat. So what they sang, could be written down by the ''artistic'' type, if the latter thought that the ''empiric'' psaltis was good enough. The latter case showed a certain competence which Chrysanthos already expected on the level of the ''empiric'' type. The ''artistic'' type could read, study, and transcribe all the four chant genres, and thus, they were able to repeat everything in a precise and identical way. This gave them the opportunity to create an ''

idiomelon

(Medieval Greek: from , 'unique' and , 'melody'; Church Slavonic: , )—pl. ''idiomela''—is a type of sticheron found in the liturgical books used in the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite, ...

'' of their own, if they simply followed the syntax of a given text by the use of ''open'' (ἀτελεῖς καταλήξεις), ''closing'' (ἐντελεῖς καταλήξεις) and ''final cadences'' (τελικαὶ καταλήξεις). Hence, the ''artistic'' type could study other musicians and learn from their art, as long as they imitated them in their own individual way—especially in the ''papadic'' (kalophonic) genre. But only the latter ''experienced'' type understood the emotive effects of music well enough, so that they could invent text and music in exactly the way, as they wished to move the soul of the auditory.

As well for the eight echoi of the Octoechos (book 4) as for the use of rhythm (book 2), Chrysanthos described the effects that both could create, usually with reference to ancient Greek scientists and philosophers. Despite that Chrysanthos agreed with the Arabo-Persian concept of musicians as humours maker (''mutriban'') and with the dramaturgy of rhythm in a mystic context, his ethic concept of music was collective concerning the Octoechos and individual concerning rhythm, at least in theory. While the ethos of the echoi were characterised very generally (since

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

), the "three tropes of rhythm" (book 2, chapter 12) were distincted as systaltic (συσταλτικὴ, λυπηρὸς "sad"), diastaltic (διασταλτικὴ, θυμὸς "rage"), and hesychastic (ἡσυχαστικὴ, ἡσυχία "peace, silence" was connected with an Athonite mystic movement). ''Systaltic'' and ''diastaltic'' effects were created by the beginning of the rhythmical period (if it starts on an ''arsis'' or ''thesis'') and by the use of the tempo (slow or fast). The ''hesychastic'' trope required a slow, but smooth rhythm, which used simple and rather equal time proportions. The agitating effect of the fast ''diastaltic'' trope could become enthusiastic and cheerful by the use of hemiolic rhythm.

In conclusion, Chrysanthos' theory was less academic than experimental and creative, and the tradition was rather an authorisation of the creative and open-minded experiments of the most important protagonists around the Patriarchate and the Fener district, but also with respect to patriotic and anthropological projects in the context of ethnic and national movements.

Makamlar as an echos aspect

Medieval Arabic sources describe the important impact that the Byzantine and Greek traditions of Damascus had for the development of an Arab music tradition, when the melodies (since 1400

maqamat) had been already described as ''naġme''. Today the Greek reception of Ottoman ''

makam

The Turkish makam ( Turkish: ''makam'' pl. ''makamlar''; from the Arabic word ) is a system of melody types used in Turkish classical music and Turkish folk music. It provides a complex set of rules for composing and performance. Each makam spec ...

lar'' by the transcription into Byzantine neume notation can be recognised as a process in six different stages or steps. The first were teretismata or kratemata which allowed various experiments with rhythm and melos like the integration of Persian chant. The second step was an interest for particular transitions inspired by makam compositions like

Petros Bereketis

Petros Bereketis ( el, Πέτρος Μπερεκέτης) or Peter the Sweet (Πέτρος ο Γλυκής) was one of the most innovative musicians of 17th-century Constantinople (Ottoman period). He, together with Panagiotes the New Chrysaphes, ...

' heirmoi of the early 18th century, in which he used certain ''makam'' intervals as a kind of change of the genus (μεταβολή κατὰ γένος) for refined transitions between certain echoi. The third stage was a systematic collection of ''seyirler'', in order to adapt the written transmission of Byzantine chant to other traditions. The fourth and most important step was a reform of the notation as the medium of written transmission, in order to adapt it to the scales and the tone system which was the common reference for all

musicians of the Ottoman Empire. The fifth step was the systematic transcription of the written transmission of ''makamlar'' into modern Byzantine neumes, the ''Mecmuase'', a form of Anthology which was used by Court and Sephardic musicians as well, but usually as text books. The sixth and last step was the composition of certain ''makamlar'' as part of the Octoechos tradition, after ''external music'' had turned into something ''internal''. The ''exoteric'' had become ''esoteric''.

"Stolen" music

Petros Peloponnesios Petros Peloponnesios ("Peter the Peloponnesian") or Peter the Lampadarios (c. 1735 Tripolis–1778 Constantinople) was a great cantor, composer and teacher of Byzantine and Ottoman music. He must have served as second ''domestikos'' between his arri ...

(about 1735–1778), the teacher of the Second Music School of the Patriarchate, was born in Peloponnese, but already as a child, he grew up at

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

within its various music traditions. An Ottoman anecdote about "the thief Petros" (Hırsız Petros) testified that his capability to memorize and to write down music was so astonishing, that he was able to steal his melodies from everywhere and to make them up as an own composition which convinced the audience more than the musician, from whom he once had stolen it. His capacity as listener included, that he could understand any music according to its own tradition—this was not necessarily the Octoechos for a Greek socialised at

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

—, so that he was rather believed to be its original creator. Concerning the competence of notating music, he was not only well known as the inventor of an own method to transcribe music into Late Byzantine neumes. The use of notation as a medium of written transmission had never had such an important role within most of the Ottoman music traditions, but in case of "Hırsız Petros" a lot of musicians preferred to ask him for his permission, before they had published their own compositions. Until today the living tradition of monodic Orthodox chant is dominated by Petros Peloponnesios' own compositions and his reformulation of the traditional chant books

heirmologion

Irmologion ( grc-gre, τὸ εἱρμολόγιον ) is a liturgical book of the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite. It contains ''irmoi'' () organised in sequences of odes (, sg. ) and su ...

(the ''katavaseion'' melodies) and

sticherarion

A sticheron (Greek: "set in verses"; plural: stichera; Greek: ) is a hymn of a particular genre sung during the daily evening (Hesperinos/Vespers) and morning (Orthros) offices, and some other services, of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Cath ...

(his ''Doxastarion syntomon'' is today distributed in most of the

Menaia as they are used in several National-Orthodox traditions).

In Petros' time Panagiotes Halacoğlu and Kyrillos Marmarinos, Metropolit of

Tinos

Tinos ( el, Τήνος ) is a Greek island situated in the Aegean Sea. It is located in the Cyclades archipelago. The closest islands are Andros, Delos, and Mykonos. It has a land area of and a 2011 census population of 8,636 inhabitants.

Tinos ...

, were collecting the ''seyirler'' by a transcription into Late Byzantine notation—other musicians, who had grown up with

Alevi

Alevism or Anatolian Alevism (; tr, Alevilik, ''Anadolu Aleviliği'' or ''Kızılbaşlık''; ; az, Ələvilik) is a local Islamic tradition, whose adherents follow the mystical Alevi Islamic ( ''bāṭenī'') teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, w ...

de and

Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

compositions and with the makam ''seyirler'' of the

Ottoman court

Ottoman court was the culture that evolved around the court of the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman court was held at the Topkapı Palace in Constantinople where the sultan was served by an army of pages and scholars. Some served in the Treasury and the ...

and who knew not just Byzantine neumes, but also other notation systems of the Empire.

The next step which followed the systematic collection of ''seyirler'' was its classification and integration according to the Octoechos. The different ''usulümler'' were just transcribed under their names by the syllables "düm" and "tek" (for instance δοὺμ τεκ-κὲ τὲκ) with the number of beats or a division of one beat. The neume transcription just mentioned the ''

makam

The Turkish makam ( Turkish: ''makam'' pl. ''makamlar''; from the Arabic word ) is a system of melody types used in Turkish classical music and Turkish folk music. It provides a complex set of rules for composing and performance. Each makam spec ...

'' and the ''

usul'' at the beginning of the piece, and the main question was, which modal signature of the Octoechos had to be used to transcribe a certain ''makam'' and which additional ''phthora'' was needed to indicate the particular intonation by a change of genos (μεταβολή κατὰ γένος), the integrative concept since the ''Hagiopolites''.

The makamlar of the diatonic echos varys

One important innovation of the reformed neume notation and its "New Method" of transcription was the heptaphonic solfeggio, which was not based on the Western equal temperature but on the frets of the

tambur

The ''tambur'' (spelled in keeping with TDK conventions) is a fretted string instrument of Turkey and the former lands of the Ottoman Empire. Like the ney, the armudi (lit. pear-shaped) kemençe and the kudüm, it constitutes one of the fou ...

—a long-necked lute which had replaced the

oud

, image=File:oud2.jpg

, image_capt=Syrian oud made by Abdo Nahat in 1921

, background=

, classification=

* String instruments

*Necked bowl lutes

, hornbostel_sachs=321.321-6

, hornbostel_sachs_desc=Composite chordophone sounded with a plectrum

, ...

at the Ottoman court (''mehterhane'') by the end of the 17th century and which also took its place in the representation of the tone system. In his reformulation of the ''sticheraric melos''

Petros Peloponnesios Petros Peloponnesios ("Peter the Peloponnesian") or Peter the Lampadarios (c. 1735 Tripolis–1778 Constantinople) was a great cantor, composer and teacher of Byzantine and Ottoman music. He must have served as second ''domestikos'' between his arri ...

defined most of the echos-tritos models as enharmonic ('), but the diatonic ''varys'' ("grave mode") was no longer based on the ''tritos pentachord'' B flat—F according to the tetraphonic tone system ("trochos system"), it was based according to the tambur frets on an octave on B natural on a fret called "arak", so that the pentachord had been diminished to a tritone. Thus, some melodic models which were well known from Persian, Kurdish, or another music traditions of the Empire, could be integrated within '.

For the printed chant books also a New Method had to be created which was concerned about the transcription of the ''makamlar''. Several theoretical treatises followed Chrysanthos and some of them treated the New Method of transcribing exoteric music, which meant folklore of different regions of the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean which often used tunes far from the Byzantine Octoechos tradition, but also ''makamlar'' traditions of the Court and of Sufi lodges (''tekke'').

Panagiotes Keltzanides' method of exoteric music

Panagiotes Keltzanides' "Methodical Teaching of the Theory and Practice of External music" (

1881) is not only one of few complete treatises which continue the theoretical reflection of Panagiotes Halaçoğlu and Kyrillos Marmarinos. It also contained a reproduction of a manuscript by

Konstantinos the Protopsaltes with a representation of the tambur frets and interval calculations referred to certain ''makamlar'' and ''echoi''.

The whole book is written about a composition of Beyzade Yangu Karaca and Çelebi Yangu, a didactic chant to memorize each ''makam'' like each great sign in the ''Mega Ison'' according to the school of John Glykys, and their composition was arranged by Konstantinos the Protopsaltes, and transcribed by

Stephanos the Domestikos and

Theodoros Phokaeos. Konstantinos' negative opinion concerning the reform notation had been well-known, so it was left to his students to transcribe the method of his teaching and its subjects. It became obviously the motivation for Panagiotes Keltzanides' publication, thus, he taught a systematic transcription method for all ''makamlar'' according to the New Method.

The main part of his work is the first part of the seventh chapter. The identification of a certain ''makam'' by a fret name makes the fret name to a substitute of a solmisation syllable used for the basis tone. Thus, "dügah" (D: πα, α') represents all ''makamlar'' which belong to the ', "segah" (E: βου, β') represents all ''makamlar'' of the diatonic ', "çargah" (F: γα, γ') all ''makamlar'' of ', "neva" (G: δι, δ') all ''makamlar'' of the ', "hüseyni" (a: κε, πλ α') all ''makamlar'' of the ''echos plagios tou protou'', "hicaz" as makam lies on "dügah" (D: πα in chromatic solfeggio, πλ β') and represents the different ''hard chromatic'' forms of ', "arak" (B natural: ζω, υαρ) represents the diatonic ', and finally "rast" (C: νη, πλ δ') represents all ''makamlar'' of '. It is evident that the whole solution is based on Chrysanthos New Method, and it is no longer compatible with the ''Papadike'' and the former solfeggio based on the ''trochos system''. On the other hand, the former concept of Petros Bereketis to use a ''makam'' for a temporary change of the genus is still present in Keltzanides' method. Every ''makam'' can now be represented and even develop its own ''melos'' like any other ''echos'', because the proper interval structure of a certain ''makam'' is indicated by the use of additional ' which were sometimes named after a certain ''makam'', as long as the ''phthora'' was representative for just one ''makam''.

For instance the ''seyir'' of ''makam sabâ'' (μακὰμ σεμπὰ) was defined as an aspect of ''echos protos'' (ἦχος πρῶτος) on fret "dügah", despite that there is no chromaticism on γα (F) in any ''melos'' of '. There are several compositions in ''echos varys''—also from the great teachers like

Gregorios the Protopsaltes—which are in fact compositions in ''makam sabâ'', but it has no proper ''phthora'' which would clearly indicate the difference between ''echos varys'' and ''makam sabâ'' (see also Chrysanthos' method of transcription in

his chroa chapter). A Greek singer from Istanbul would recognize it anyway, but it became so common that it might be regarded as an aspect of ''echos varys'' by psaltes of the living tradition. On the other hand, the intonation of ''makam müstear'' has its own characteristic ' (φθορά μουσταχὰρ) which is often used in printed chant books. Though it is treated as an aspect of ''echos legetos'', according to Keltzanides treated as an aspect of the diatonic ' on fret "segah", its intonation is so unique, that it will be even recognised by an audience which is not as familiar with ''makam'' music, at least as something odd in an echos which already requires a very experienced psaltes.

In 1881 the transcription of ''makam'' compositions was nothing new, because several printed anthologies had been published by Phanariotes: ''Pandora'' and ''Evterpe'' by

Theodoros Phokaeos and

Chourmouzios the Archivist

Chourmouzios the Archivist or Chourmouzios Chartophylax ( gr, Χουρμούζιος ὁ Χαρτοφύλαξ, "Chourmoúzios the Chartophýlax"), also known with the nickname "the Chalkenteros" (, "he with a copper intestine"), born Chourmouzios ...

in 1830, ''Harmonia'' by Vlachopoulos in 1848, ''Kaliphonos Seiren'' by Panagiotes Georgiades in 1859, ''Apanthisma'' by Ioannis Keïvelis in 1856 and in 1872, and ''Lesvia Sappho'' by Nikolaos Vlahakis in 1870 in another reform notation invented in Lesbos. New was without any doubt the systematic approach to understand the whole system of ''makamlar'' as part of the Octoechos tradition.

Octoechos melopœia according to the New Method

The

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

echoi are currently used in the monodic

hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' ...

s of the

Eastern Orthodox Churches in Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, Croatia, Albania, Serbia, Macedonia, Italy, Russia, and in several

Oriental Orthodox Churches

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent ...

of the Middle East.

According to medieval theory, the plagioi (oblique) echoi mentioned above (

Hagiopolitan Octoechos

Oktōēchos (here transcribed ""; Greek: pronounced in koine: ; from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмогласие, ''Osmoglasie'' from о́смь "eight" and гласъ "voice, sound") is the n ...

) employ the same scales, the final degrees of the ''plagioi echoi'' are a fifth below with respect to the ones of the ''kyrioi echoi''. There are typically two main notes that defined each of the Byzantine tones (ἦχοι, гласове): the base degree (basis) or ison which is sung as a typical drone with the melody by ison-singers (''isokrates''), and the final degree (finalis) of the mode on which the hymn ends.

In current traditional practice, there are more than only one ''basis'' in certain ''mele'', and in some particular cases the base degree of the mode is not even the degree of the ''finalis''. The Octoechos cycles as they exist in different chant genres, are no longer defined as entirely ''diatonic'', some of the ''chromatic'' or ''enharmonic mele'' had replaced the former diatonic ones entirely, so often the pentachord between the ''finales'' does no longer exist or the ''mele'' of certain ''kyrioi'' ''echoi'' used in more elaborated genres are transposed to the ''finalis'' of its ''plagios'', for instance the ''papadic melos'' of ''echos protos''.

Their melodic patterns were created by four generations of teachers at the "New Music School of the Patriarchate" (Constantinople/Istanbul), which redefined the Ottoman tradition of Byzantine chant between 1750 and 1830 and transcribed it into the notation of the New Method since 1814.

Whereas in Gregorian chant a

mode

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

referred to the classification of chant according to the local

tonaries and the obligatory psalmody, the Byzantine echoi were rather defined by an oral tradition how to do the thesis of the melos, which included melodic patterns like the base degree (''

ison

Ison, ISON or variant, may refer to: Geography

* Isön, a small island in lake Storsjön, Jämtland, Sweden People First name / given name

*Ison (rapper), stage name of Ison Glasgow, a Swedish rapper of American origin Last name / family name

* Dav ...

''), open or closed melodic endings or cadences (cadential degrees of the mode), and certain accentuation patterns. These rules or methods defined ''melopœia,'' the different ways of creating a certain ''melos''. The melodic patterns were further distinguished according to different chant genres, which traditionally belong to certain types of chant books, often connected with various local traditions.

Melopœia of new exegeseis types

According to the New Method, the whole repertory of hymns used in Orthodox chant, had been divided into four chant genres or exegesis types defined by their tempo and their melodic patterns used for each echos. On the one hand, their names were taken from traditional chant books, on the other hand, different forms, which had never been connected in hymnology, were now put together by a purely musical definition of ''melos'' which had been summed up by a very broad concept of more or less elaborated psalmody:

*''Papadic'' hymns are melismatic

troparia

A troparion (Greek , plural: , ; Georgian: , ; Church Slavonic: , ) in Byzantine music and in the religious music of Eastern Orthodox Christianity is a short hymn of one stanza, or organised in more complex forms as series of stanzas.

The wi ...

sung during the

Divine Liturgy

Divine Liturgy ( grc-gre, Θεία Λειτουργία, Theia Leitourgia) or Holy Liturgy is the Eucharistic service of the Byzantine Rite, developed from the Antiochene Rite of Christian liturgy which is that of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of C ...

(

Cheruvikon,

Koinonikon, etc.), according to the New Method slow in tempo, and fast in ''Teretismoi'' or ''Kratemata'' (sections using abstract syllables); the name "papadic" refers to the treatise of psaltic art called "papadike" (παπαδική) and its elaborated form is based on kalophonic compositions (between the 14th and the 17th century). Hence, also kalophonic compositions over models taken from the ''

sticherarion

A sticheron (Greek: "set in verses"; plural: stichera; Greek: ) is a hymn of a particular genre sung during the daily evening (Hesperinos/Vespers) and morning (Orthros) offices, and some other services, of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Cath ...

'' (so-called ''stichera kalophonika'' or ''anagrammatismoi'') or from the ''

heirmologion

Irmologion ( grc-gre, τὸ εἱρμολόγιον ) is a liturgical book of the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite. It contains ''irmoi'' () organised in sequences of odes (, sg. ) and su ...

'' (''heirmoi kalophonikoi'') were part of the ''papadic'' genre and used its ''melos'' (

Papadic Octoechos

Oktōēchos (here transcribed "Octoechos"; Greek: , pronounced in Constantinopolitan: ; from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмогласие, ''Osmoglasie'' from о́смь "eight" and гласъ " ...

).

*''Sticheraric'' hymns are taken from the book

sticherarion

A sticheron (Greek: "set in verses"; plural: stichera; Greek: ) is a hymn of a particular genre sung during the daily evening (Hesperinos/Vespers) and morning (Orthros) offices, and some other services, of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Cath ...

(στιχηράριον), its text is composed in hexameter, today the Greek chant book is called ''Doxastarion'' ("the book of

Doxasticha"), according to the New Method there is a slow (''Doxastarion argon'') and a fast way (''Doxastarion syntomon'') of singing its melos; the tempo used in ''syntomon'' is 2 times faster than that of the papadic melos. Since the old repertory there has been always a distinction between ''stichera idiomela'', ''stichera'' with own melodies which are usually sung only once during the year, and ''stichera avtomela''—metrical and melodical models which belong less to the repertory itself, they were rather used to compose several ''stichera prosomeia'', so that these melodies were sung on several occasions. The name ''Doxastarion'' derived from the practice to introduce these chants by one or both ''stichoi'' of the

small doxology. Hence, ''stichera'' were also called ''Doxastika'' and regarded as a derivative of psalmody, at least according to