The

apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

system in

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

was ended through a series of bilateral and multi-party negotiations between 1990 and 1993. The negotiations culminated in the passage of a new

interim Constitution A provisional constitution, interim constitution or transitional constitution is a constitution intended to serve during a transitional period until a permanent constitution is adopted. The following countries currently have,had in the past,such a c ...

in 1993, a precursor to the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

of 1996; and in South Africa's first non-racial

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative ...

in 1994, won by the

African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a Social democracy, social-democratic political party in Republic of South Africa, South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when ...

(ANC)

liberation movement

A liberation movement is an organization or political movement leading a rebellion, or a non-violent social movement, against a colonial power or national government, often seeking independence based on a nationalist identity and an anti-imperial ...

.

Although there had been gestures towards negotiations in the 1970s and 1980s, the process accelerated in 1990, when the government of

F. W. de Klerk took a number of unilateral steps towards reform, including releasing

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist who served as the President of South Africa, first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1 ...

from prison and unbanning the ANC and other political organisations. In 1990–91, bilateral "talks about talks" between the ANC and the government established the pre-conditions for substantive negotiations, codified in the Groote Schuur Minute and Pretoria Minute. The first multi-party agreement on the desirability of a negotiated settlement was the 1991 National Peace Accord, consolidated later that year by the establishment of the multi-party Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA). However, the second plenary session of CODESA, in May 1992, encountered stubborn

deadlock

In concurrent computing, deadlock is any situation in which no member of some group of entities can proceed because each waits for another member, including itself, to take action, such as sending a message or, more commonly, releasing a loc ...

over questions of

regional autonomy Regional autonomy is decentralization of governance to outlying regions. Recent examples of disputes over autonomy include:

* The Basque region of Spain

* The Catalan region of Spain

* The Sicilia region of Italy

* The disputes over autonomy of pr ...

, political and cultural

self-determination, and the constitution-making process itself.

The ANC returned to a programme of mass action, hoping to leverage its popular support, only to withdraw from negotiations entirely in June 1992 after the

Boipatong massacre. The massacre revived pre-existing, and enduring, concerns about state complicity in

political violence, possibly through the use of a state-sponsored

third force bent on destabilisation. Indeed, political violence was nearly continuous throughout the negotiations – white

extremists

Extremism is "the quality or state of being extreme" or "the advocacy of extreme measures or views". The term is primarily used in a political or religious sense to refer to an ideology that is considered (by the speaker or by some implied shar ...

and

separatists

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

launched periodic attacks, and there were regular clashes between supporters of the ANC and supporters of the

Inkatha Freedom Party

The Inkatha Freedom Party ( zu, IQembu leNkatha yeNkululeko, IFP) is a right-wing political party in South Africa. The party has been led by Velenkosini Hlabisa since the party's 2019 National General Conference. Mangosuthu Buthelezi founded ...

(IFP). However, intensive bilateral talks led to a new bilateral Record of Understanding, signed between the ANC and the government in September 1992, which prepared the way for the ultimately successful Multi-Party Negotiating Forum of April–November 1993.

Although the ANC and the governing

National Party were the main figures in the negotiations, they encountered serious difficulties building consensus not only among their own constituencies but among other participating groups, notably

left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

black groups,

right-wing white groups, and the

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

leaders of the

independent homelands and

KwaZulu

KwaZulu was a semi-independent bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government as a homeland for the Zulu people. The capital was moved from Nongoma to Ulundi in 1980.

It was led until its abolition in 1994 by Chief Mangosuth ...

homeland. Several groups, including the IFP, boycotted the tail-end of the negotiations, but the most important among them ultimately agreed to participate in the 1994 elections.

Background

Apartheid was a system of

racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

and

segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

by the South African government. It was formalised in 1948, forming a framework for political and economic dominance by the

white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

population and severely restricting the political rights of the

black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ...

majority.

Between 1960 and 1990, the

African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a Social democracy, social-democratic political party in Republic of South Africa, South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when ...

and other mainly black opposition political organisations were banned. As the

National Party cracked down on black opposition to apartheid, most leaders of ANC and other opposition organisations were either killed, imprisoned, or went into exile.

However, increasing local and international pressure on the government, as well as the realisation that apartheid could neither be maintained by force forever nor overthrown by the opposition without considerable suffering, eventually led both sides to the negotiating table. The

Tripartite Accord, which brought an end to the

South African Border War

The South African Border War, also known as the Namibian War of Independence, and sometimes denoted in South Africa as the Angolan Bush War, was a largely asymmetric conflict that occurred in Namibia (then South West Africa), Zambia, and Ango ...

in neighbouring Angola and Namibia, created a window of opportunity to create the enabling conditions for a negotiated settlement, recognized by

Niel Barnard

Lukas Daniel Barnard (born 1949), known as Niël Barnard, is a former head of South Africa's National Intelligence Service and was notable for his behind-the-scenes role in preparing former president Nelson Mandela and former South African pre ...

of the National Intelligence Service.

Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith: January 1974

On 4 January 1974,

Harry Schwarz

Harry Heinz Schwarz (13 May 1924 – 5 February 2010) was a South African lawyer, statesman and long-time political opposition leader against apartheid in South Africa, who eventually served as the South African Ambassador to the United States ...

, leader of the liberal-reformist wing of the

United Party, met with

Gatsha (later Mangosuthu) Buthelezi, Chief Executive Councillor of the black homeland of

KwaZulu

KwaZulu was a semi-independent bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government as a homeland for the Zulu people. The capital was moved from Nongoma to Ulundi in 1980.

It was led until its abolition in 1994 by Chief Mangosuth ...

and signed a five-point plan for racial peace in South Africa, which came to be known as the

Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith

The Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith was a statement of core principles laid down by South African political leaders Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Harry Schwarz on 4 January 1974. It was signed in Mahlabatini, KwaZulu-Natal, hence its name. Its purpo ...

. The declaration stated that "the situation of South Africa in the world scene as well as internal community relations requires, in our view, an acceptance of certain fundamental concepts for the economic, social, and constitutional development of our country." It called for negotiations involving all peoples, in order to draw up constitutional proposals stressing opportunity for all with a

Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

to safeguard these rights. It suggested that the federal concept was the appropriate framework for such changes to take place. It also affirmed that political change must take place through non-violent means.

The declaration was the first of such agreements by acknowledged black and white political leaders in South Africa that affirmed to these principles. The commitment to the peaceful pursuit of political change was declared at a time when neither the National Party nor the African National Congress was looking to peaceful solutions or dialogue. The declaration was heralded by the English speaking press as a breakthrough in race relations in South Africa. Shortly after it was issued, the declaration was endorsed by several chief ministers of the black homelands, including

Cedric Phatudi

Dr Cedric Namedi Phatudi (27 May 1912 – 7 October 1987) was the Chief Minister of Lebowa, one of the South African bantustans.

Early life

Born in Ga-Mphahlele, the son of the chief of the Mphahlele tribe. He earned his basic education in mis ...

(

Lebowa

Lebowa was a bantustan ("homeland") located in the Transvaal in northeastern South Africa. Seshego initially acted as Lebowa's capital while the purpose-built Lebowakgomo was being constructed. Granted internal self-government on 2 October ...

),

Lucas Mangope

Kgosi Lucas Manyane Mangope (27 December 1923 – 18 January 2018) was the leader of the Bantustan (homeland) of Bophuthatswana. The territory he ruled over was distributed between the Orange Free State – what is now Free State – and North W ...

(

Bophuthatswana

Bophuthatswana (, meaning "gathering of the Tswana people"), officially the Republic of Bophuthatswana ( tn, Riphaboliki ya Bophuthatswana; af, Republiek van Bophuthatswana), was a Bantustan (also known as "Homeland"; an area set aside for mem ...

) and Hudson Nisanwisi (

Gazankulu). Despite considerable support from black leaders, the English speaking press and liberal figures such as

Alan Paton, the declaration saw staunch opposition from the National Party, the Afrikaans press and the conservative wing of Harry Schwarz's United Party.

Early contact: 1980s

The very first meetings between the South African Government and

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist who served as the President of South Africa, first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1 ...

were driven by the

National Intelligence Service (NIS) under the leadership of

Niel Barnard

Lukas Daniel Barnard (born 1949), known as Niël Barnard, is a former head of South Africa's National Intelligence Service and was notable for his behind-the-scenes role in preparing former president Nelson Mandela and former South African pre ...

and his Deputy Director General,

Mike Louw. These meetings were secret in nature and were designed to develop an understanding about whether there were sufficient common grounds for future peace talks. As these meetings evolved, a level of trust developed between the key actors (Barnard, Louw, and Mandela).

To facilitate future talks while preserving secrecy needed to protect the process, Barnard arranged for Mandela to be moved off

Robben Island

Robben Island ( af, Robbeneiland) is an island in Table Bay, 6.9 kilometres (4.3 mi) west of the coast of Bloubergstrand, north of Cape Town, South Africa. It takes its name from the Dutch word for seals (''robben''), hence the Dutch/Afrik ...

to

Pollsmoor Prison

Pollsmoor Prison, officially known as Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison, is located in the Cape Town suburb of Tokai in South Africa. Pollsmoor is a maximum security penal facility that continues to hold some of South Africa's most dangerous c ...

in 1982. This provided Mandela with more comfortable lodgings, but also gave easier access in a way that could not be compromised. Barnard therefore brokered an initial agreement in principle about what became known as "talks about talks." It was at this stage that the process was elevated from a secret engagement to a more public engagement.

The first less-tentative meeting between Mandela and the

National Party government came while

P. W. Botha

Pieter Willem Botha, (; 12 January 1916 – 31 October 2006), commonly known as P. W. and af, Die Groot Krokodil (The Big Crocodile), was a South African politician. He served as the last prime minister of South Africa from 1978 to 1984 and ...

was

State President. In November 1985, Minister

Kobie Coetsee

Hendrik Jacobus Coetsee (19 April 1931 – 29 July 2000), known as Kobie Coetsee, was a South African lawyer, National Party politician and administrator as well as a negotiator during the country's transition to universal democracy.

Biograph ...

met Mandela in the hospital while Mandela was being treated for prostate surgery. Over the next four years, a series of tentative meetings took place, laying the groundwork for further contact and future negotiations, but little real progress was made and the meetings remained secret until several years later.

As the secret talks bore fruit and the political engagement started to take place, the National Intelligence Service withdrew from centre stage in the process and moved to a new phase of operational support work. This new phase was designed to test public opinion about a negotiated solution. Central to this planning was an initiative that became known in Security Force circles as the Dakar Safari, which saw a number of prominent Afrikaner opinion-makers engage with the

African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a Social democracy, social-democratic political party in Republic of South Africa, South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when ...

(ANC) in Dakar, Senegal, and

Leverkusen

Leverkusen () is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, on the eastern bank of the Rhine. To the south, Leverkusen borders the city of Cologne, and to the north the state capital, Düsseldorf.

With about 161,000 inhabitants, Leverkusen is o ...

, Germany at events organized by the

Institute for Democratic Alternatives in South Africa

The Institute for Democratic Alternatives in South Africa (IDASA) later known as the Institute for Democracy in South Africa was a South African-based think-tank organisation that was formed in 1986 by Frederik van Zyl Slabbert and Alex Boraine. ...

.

The operational objective of this meeting was not to understand the opinions of the actors themselves—that was very well known at this stage within strategic management circles—but rather to gauge public opinion about a movement away from the previous security posture of confrontation and repression to a new posture based on engagement and accommodation.

Reforms announced: February 1990

When

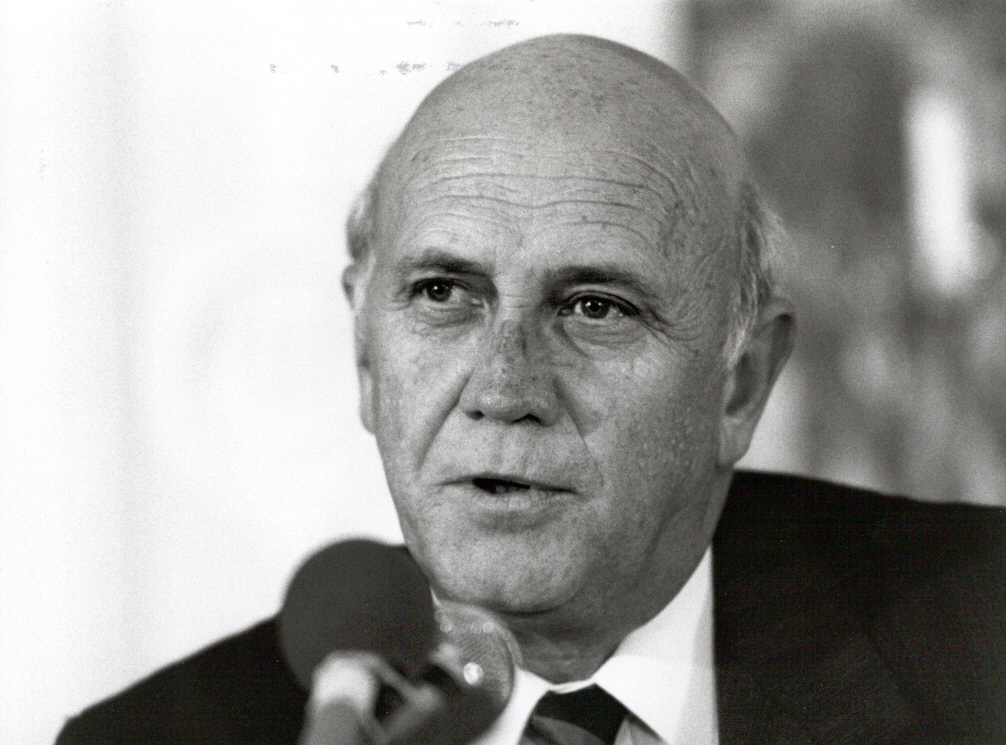

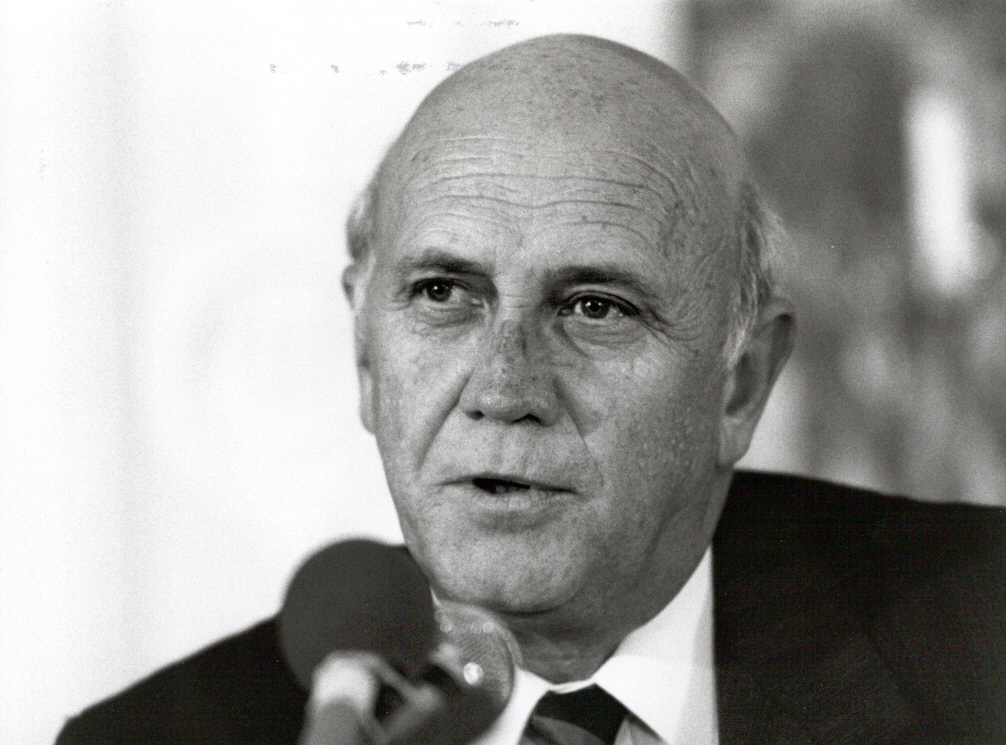

F. W. de Klerk became president in 1989, he was able to build on the previous secret negotiations with Mandela. The first significant steps towards formal negotiations took place in February 1990 when, in his

speech at the opening of Parliament, de Klerk announced the repeal of the ban on the ANC and other banned political organisations, as well as Mandela's release after 27 years in prison. Mandela was released on 11 February 1990 and direct talks between the ANC and the government were scheduled to begin on 11 April.

However, on 26 March, 11 protestors were killed by

police

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and t ...

in the

Sebokeng

Sebokeng () locally called Zweni by residents, is a middle-class township in the Emfuleni Local Municipality in southern Gauteng, South Africa near the industrial cities of Vanderbijlpark and Vereeniging. Other neighboring townships include Evaton ...

massacre, and the ANC announced on 31 March that it intended to pull out of the negotiations indefinitely. The talks were only rescheduled after an emergency meeting between Mandela and de Klerk, held in early April.

Early "talks about talks"

Groote Schuur Minute: May 1990

On 2–4 May 1990, the ANC met with the South African government at the

Groote Schuur

Groote Schuur (, Dutch for "big shed") is an estate in Cape Town, South Africa. In 1657, the estate was owned by the Dutch East India Company which used it partly as a granary. Later, the farm and farmhouse was sold into private hands. Groote Sc ...

presidential residence in

Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, in what were touted as the first of several "talks about talks", intended to negotiate the terms for more substantive negotiations.

After the first day of meetings, a joint statement was released which identified the factors held by the parties to constitute obstacles to further negotiations: the government was concerned primarily about the ANC's ongoing commitment to armed struggle, while the ANC listed six preliminary demands, including the release of

political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

s, the return of ANC activists from exile, and the lifting of the

state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

.

The outcome of the talks was a joint communiqué known as the Groote Schuur Minute, which was released on 4 May and which canvassed, though rarely in decisive terms, many of the seven obstacles that had been identified. The minute consisted primarily in a commitment by both parties to "the resolution of the existing climate of violence and intimidation from whatever quarter as well as a commitment to stability and to a peaceful process of negotiations".

The parties agreed to establish a working group, which should aim to complete its work before 21 May and which would consider the terms under which retroactive immunity would be granted for political offences. The government also committed to review its security legislation to "ensure normal and free political activities".

Pretoria Minute: August 1990

Tensions between the parties were piqued in late July, when several senior members of the ANC were arrested because of their involvement in

Operation Vula, an ongoing clandestine ANC operation inside the country. Police raids also turned up Operation Vula material which de Klerk believed substantiated his concerns about the sincerity of the ANC's commitment to negotiations and about its intimacy with the

South African Communist Party

The South African Communist Party (SACP) is a communist party in South Africa. It was founded in 1921 as the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), tactically dissolved itself in 1950 in the face of being declared illegal by the governing Na ...

(SACP).

Following another meeting between Mandela and de Klerk on 26 July, intensive bilateral talks were held on 6 August in

Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends eastward into the foot ...

, resulting in another joint communiqué, the Pretoria Minute.

The minute reiterated and extended earlier pledges by the government to consider amending its security legislation and lifting the state of emergency (then ongoing only in

Natal province); and it also committed the government to releasing certain categories of political prisoners from September and indemnifying certain categories of political offences from October. Most significantly, however, the minute included a commitment to the immediate and unilateral suspension of all armed activities by the ANC and its armed wing,

Umkhonto we Sizwe.

D. F. Malan Accord: February 1991

The Pretoria Minute was followed on 12 February 1991 by the

D. F. Malan Accord, which contained commitments arising from the activities of the working group on political offences, and which also clarified the terms of the ANC's suspension of armed struggle. It specified that the ANC would not launch attacks, create underground structures, threaten or incite violence, infiltrate men and materials into the country, or train men for armed action inside the country.

This concession was already unpopular with important segments of the ANC's support base,

and the situation was further unsettled by the continuation of political violence in parts of the country, particularly in Natal and certain

Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

townships, where ANC and IFP supporters periodically clashed.

In early April 1991, the ANC imposed an ultimatum, threatening to suspend all negotiations unless the government took steps to reduce the violence.

Its case was strengthened by a major scandal in July 1991, known as Inkathagate, which unravelled after journalist

David Beresford published evidence, obtained from a

Security Branch informant, that the government had been subsidising the IFP.

National Peace Accord: September 1991

On 14 September 1991, twenty-six organisations signed the National Peace Accord. The first multi-party agreement towards negotiations, it did not resolve substantive questions about the nature of the post-apartheid settlement, but did include guidelines for the conduct of political organisations and security forces. To address the ongoing political violence, it established multi-party conflict resolution structures (or "sub-committees") at the community level, as well as related structures at the national level, notably the

Goldstone Commission

The Goldstone Commission, formally known as the Commission of Inquiry Regarding the Prevention of Public Violence and Intimidation, was appointed on 24 October 1991 to investigate political violence and intimidation in South Africa. Over its three- ...

. The accord prepared the way for multi-party negotiations, under the organisation that came to be called the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA).

Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA)

Composition

19 groups were represented at CODESA: the South African government and the governments of the so-called

TBVC states

A Bantustan (also known as Bantu homeland, black homeland, black state or simply homeland; ) was a territory that the National Party administration of South Africa set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa (now ...

(the nominally independent

homelands of

Transkei

Transkei (, meaning ''the area beyond he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei ( xh, iRiphabliki yeTranskei), was an unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa from 1976 to 1994. It was, along with Ciskei, a Ba ...

,

Bophuthatswana

Bophuthatswana (, meaning "gathering of the Tswana people"), officially the Republic of Bophuthatswana ( tn, Riphaboliki ya Bophuthatswana; af, Republiek van Bophuthatswana), was a Bantustan (also known as "Homeland"; an area set aside for mem ...

,

Venda

Venda () was a Bantustan in northern South Africa, which is fairly close to the South African border with Zimbabwe to the north, while to the south and east, it shared a long border with another black homeland, Gazankulu. It is now part of the ...

, and

Ciskei

Ciskei (, or ) was a Bantustan for the Xhosa people-located in the southeast of South Africa. It covered an area of , almost entirely surrounded by what was then the Cape Province, and possessed a small coastline along the shore of the Indian O ...

); the three main political players – the ANC, the IFP, and the NP (represented separately to the government, although holding identical positions to it);

and a further variety of political groups. These were the SACP, the

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, the

Dikwankwetla Party

Dikwankwetla Party of South Africa is a political party in the Free State province, South Africa. The party was founded by Kenneth Mopeli in 1975. The party governed the bantustan state of QwaQwa from 1975 to 1994.

It was one of the signatori ...

, the Inyandza National Movement (of

KaNgwane

KaNgwane () was a bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government to be a semi-independent homeland for the Swazi people. It was called the "Swazi Territorial Authority" from 1976 to 1977. In September 1977 it was renamed KaNgwan ...

), the Intando Yesizwe Party (of

KwaNdebele

KwaNdebele was a bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government as a semi-independent homeland for the Ndebele people. The homeland was created when the South African government purchased nineteen white-owned farms and install ...

), the

Labour Party, the Transvaal and

Natal Indian Congress

The Natal Indian Congress (NIC) was an organisation that aimed to fight discrimination against Indians in South Africa.

The Natal Indian Congress was proposed by Mahatma Gandhi on 22 May 1894. established on 22 August 1894.

Gandhi was the H ...

, the

National People's Party,

Solidarity, the United People's Front, and the

Ximoko Progressive Party.

However, the negotiations were boycotted by organisations both on the far left (notably the

Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) and

Azanian People's Organisation

The Azanian People's Organisation (AZAPO) is a South African liberation movement and political party. The organisation's two student wings are the Azanian Students' Movement (AZASM) for high school learners and the other being for university leve ...

) and on far right (notably the

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

and the

Herstigte Nasionale Party

The Herstigte Nasionale Party (Reconstituted National Party) is a South African political party which was formed as a far-right splinter group of the now defunct National Party in 1969. The party name was commonly abbreviated as HNP, evokin ...

).

Buthelezi personally, though not the IFP, boycotted the sessions, in protest of the steering committee's decision not to allow a separate delegation representing the

Zulu monarch,

Goodwill Zwelithini

King Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu (27 July 1948 – 12 March 2021) was the reigning King of the Zulu nation from 1968 to his death in 2021.

He became King on the death on of his father, King Cyprian Bhekuzulu, in 1968 aged 20 years. P ...

. And South Africa's largest labour grouping, the

Congress of South African Trade Unions

The Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) is a trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions ...

, applied for but was denied permission to participate at CODESA; instead, its interests were to be represented indirectly by its

Tripartite Alliance

The Tripartite Alliance is an alliance between the African National Congress (ANC), the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP). The ANC holds a majority in the South African parliament, while ...

partners, the ANC and SACP.

In addition to a secretariat – led by

Mac Maharaj

Sathyandranath Ragunanan "Mac" Maharaj (born 22 April 1936 in Newcastle, Natal) is a retired South African politician affiliated with the African National Congress, academic and businessman of Indian origin. He was the official spokesperson ...

of the ANC and Fanie van der Merwe of the government

– and a management committee, CODESA I comprised five working groups, which became the main negotiating forums during CODESA's lifespan and each of which was dedicated to a specific issue.

Each working group included two delegates and two advisors from each of the 19 parties, as well as a chairperson appointed on a rotational basis. Each had a steering committee and some had further sub-committees. Agreements reached at the working group level were subject to ratification by the CODESA plenary.

CODESA I: December 1991

CODESA held two plenary sessions, both at the World Trade Centre in

Kempton Park outside

Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

. The first plenary was held on 20–21 December 1991; was chaired by judges

Michael Corbett, Petrus Shabort, and

Ismail Mahomed

Ismail Mahomed SCOB SC (5 July 1931 – 17 June 2000) was a South African lawyer who served as the Chief Justice of South Africa and the Chief Justice of Namibia, and co-authored the constitution of Namibia.

Early life

Mahomed was born in Pre ...

; and was broadcast live on television.

On the first day, all 19 participants signed a Declaration of Intent, assenting to be bound by certain initial principles and by further agreements reached at CODESA. Notwithstanding various enduring sticking points, the extent of agreement reached at CODESA I was remarkable. Participants agreed that South Africa was to be a united, democratic, and non-racial state, with adherence to a

separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typic ...

, with a supreme

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

and judicially enforceable

bill of rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

, with regular

multi-party elections

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system in which multiple political parties across the political spectrum run for national elections, and all have the capacity to gain control of government offices, separately or in c ...

under a system of

proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to a type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to geographical (e.g. states, regions) and political divis ...

, and with a common South African citizenship.

Disagreements about how these provisos were to be implemented, however – and, for example, what exactly was entailed by a unified state or by proportional representation – continued to occupy, and to obstruct, the working groups well into 1992.

CODESA II: May 1992

The second plenary session, CODESA II, convened on 15 May 1992 at the World Trade Centre to canvas the progress made by the working groups.

In the interim, electoral losses by the NP to the Conservative Party had led de Klerk to call a

whites-only referendum on 17 March 1992, which demonstrated overwhelming support among the white minority for reforms and a negotiated settlement and which had therefore solidified his mandate to proceed. However, de Klerk's triumph in the referendum did not curtail – and may have inflamed – political violence, including among the white right-wing;

nor did it resolve the

deadlock

In concurrent computing, deadlock is any situation in which no member of some group of entities can proceed because each waits for another member, including itself, to take action, such as sending a message or, more commonly, releasing a loc ...

that the working groups had arrived at on certain key questions. The most important elements of the deadlock arose from the work of the second working group, whose mandate was to devise constitutional principles and guidelines for the constitution-making process. In terms of the content of the constitutional principles, the ANC favoured a highly centralised government with strict limitations on regional autonomy, while the IFP and NP advocated for

federal systems of slightly different kinds, but with strong, built-in guarantees for the

representation of minority interests. For example, the NP's preferred proposal was for a

bicameral legislature whose

upper house

An upper house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house.''Bicameralism'' (1997) by George Tsebelis The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smalle ...

would incorporate a

veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

for minority groups, to exist alongside a bill of rights with specific protections for so-called

group rights

Group rights, also known as collective rights, are rights held by a group '' qua'' a group rather than individually by its members; in contrast, individual rights are rights held by individual people; even if they are group-differentiated, which ...

.

The ANC viewed such proposals as attempts to dilute majority rule and possibly to allow the maintenance of ''de facto'' apartheid in the country's Majority minority, minority-majority regions.

Perhaps even more obstructive were disagreements about how the constitution itself was to be devised and passed into law. The ANC's enduring proposal had been that the task should be entrusted to a constituent assembly, democratically elected under the principle of one man, one vote. Although it recognised that the white minority would not abide a constitution-making process without any guarantees of its outcomes, the ANC believed that the pre-agreement of constitutional principles at CODESA should suffice for such guarantees.

On the other hand, the NP held that the constitution should be negotiated among parties, in a forum resembling CODESA, and then adopted by the existing (and NP-dominated) legislature – both to protect minority interests, and to ensure Revolutionary breach of legal continuity, legal continuity.

Alternatively, if a constituent assembly was unavoidable, it insisted that approval of the new constitution should require the support of a three-quarters majority in the assembly, rather than the two-thirds majority proposed by the ANC.

Thereafter, it sought a transitional system of government under a compulsory coalition, with the cabinet drawn equally from each of the three major parties and a presidency that would rotate among them.

The IFP also opposed the notion of a democratically elected constituent assembly, although for different reasons.

As a result of this deadlock, with consensus evidently out of reach, discussions stalled and the plenary was dissolved on the second day of meetings, 16 May – although the parties reaffirmed their commitment to the Declaration of Intent, and expected to re-convene once the major disagreements had been resolved outside the plenary.

Breakdown of negotiations

Return to mass action: June–August 1992

With CODESA stalled, the ANC announced its return to a programme of "rolling mass action", aimed at consolidating – and decisively demonstrating – the level of popular support for its agenda in the constitutional negotiations.

The programme began with a nationwide stay-away on 16 June, the anniversary of the Soweto uprising, 1976 Soweto uprising.

It was overshadowed when later that week, on 17–18 June 1992, 45 residents of Boipatong, Boipatong, Gauteng were killed, primarily by Zulu people, Zulu hostel dwellers, in the

Boipatong massacre. Amid broader suspicions of state-sponsored so-called

third force involvement in the ongoing political violence, the ANC accused the government of complicity in the attack and announced, on 24 June, that it was withdrawing from negotiations until such time as the government took steps to restore its trust.

Lamenting that the massacre had thrown South Africa "back to the Sharpeville massacre, Sharpeville days", Mandela suggested that trust might be restored by specific measures to curtail political violence, including regulating workers' hostels, banning cultural weapons like the spears favoured by the IFP, and prosecuting state security personnel implicated in violence.

In the aftermath of the massacre, the ANC capitalised on public sentiment to further promote its mass action campaign, and also harnessed the increased international attention – on 15 July, Mandela addressed a meeting of the United Nations (UN) United Nations Security Council, Security Council in New York about state complicity in political violence, leading to a UN observer mission and ultimately to additional UN support for various transitional structures, including the Goldstone Commission.

The political impetus for a negotiated solution was given further urgency after the Bisho massacre on 7 September, in which the Ciskei Defence Force killed 28 ANC supporters.

Record of Understanding: September 1992

For the month following 21 August 1992, representatives of the ANC and the government met to discuss the resumption of negotiations. Specifically, the government was represented by the Minister of Constitutional Development, Roelf Meyer, and the ANC by its Secretary General, Cyril Ramaphosa.

Through intensive informal discussions, Meyer and Ramaphosa struck up a famous friendship.

Their informal meetings were followed by a full bilateral summit in

Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

on 26 September 1992, which resulted in a Record of Understanding.

The agreement improved relations between the parties to the extent that both delegations sent key members to two ''bosberaads'' (Afrikaans for "The bush, bush summits" or retreats) that summer.

The document asserted a shared desire to reopen negotiations and reflected at least partial resolutions to many of the major disagreements which had led to CODESA's collapse. On political violence, the parties agreed to further engagements, to a ban on carrying dangerous weapons in public, and to security measures at a specific list of hostels which had been identified as "problematic". The government also agreed to further extend the indemnity granted to political prisoners and to accelerate their release. The ANC, meanwhile, committed to easing tensions and to consulting its constituency "with a view to examine" its mass action programme.

Most importantly, the Record of Understanding resolved the most obstructive disagreements between the parties about the form of the constitution-making process and the nature of the post-apartheid state. In a major concession, the NP agreed that the constitution would be drafted by a democratically elected body, though one bound by pre-determined constitutional principles. The ANC agreed in broad terms to a transitional arrangement, a Government of National Unity (GNU), and, by thus conceding to a two-stage transition, agreed to postpone the full transition to pure majority rule.

This concession on the ANC's part was in keeping with an evolving internal debate, much of which revolved around a paper published during the same period in the ''African Communist'' by Joe Slovo, an influential SACP leader and negotiator. Slovo, urging the ANC-SACP alliance to take a long-term view on the transition, proposed making strategic concessions to the NP's demands, including the incorporation of a "sunset clause" which would allow a transitional period of temporary Consociationalism, power-sharing to appease white politicians, bureaucrats, and military men. In February 1993, the National Executive Committee of the African National Congress, National Executive Committee of the ANC formally endorsed the sunset clause proposal and the idea of a five-year coalition GNU, a decision which was to lubricate multi-party negotiations when they resumed later that year.

Multi-Party Negotiating Forum (MPNF)

In early March 1993, an official Multi-Party Planning Conference was held at the World Trade Centre to arrange the resumption of multi-party negotiations. The conference established the Multi-Party Negotiating Forum (MPNF), which met for the first time on 1 April 1993.

Over the remainder of the year, the parties to the MPNF devised and agreed to an

interim Constitution A provisional constitution, interim constitution or transitional constitution is a constitution intended to serve during a transitional period until a permanent constitution is adopted. The following countries currently have,had in the past,such a c ...

, which included a list of 34 "constitutional principles" by which the envisaged constituent assembly would be bound in drafting the final constitution.

Composition

The MPNF comprised 26 political groups, among them – in contrast to CODESA – the PAC, the Afrikaner Volksunie, and delegations representing various Tribal chief, traditional leaders.

It was managed by a planning committee comprising representatives from twelve of the parties, who were appointed in their personal capacity and worked full-time.

Among them were Slovo of the SACP, Ramaphosa of the ANC, Meyer of the NP, Colin Eglin of the Democratic Party, Khoisan X, Benny Alexander of the PAC, Pravin Gordhan of the Transvaal Indian Congress, Frank Mdlalose of the IFP, and Rowan Cronjé of Bophuthatswana.

Each party sent ten delegates to the plenary, which, as in CODESA, was required to ratify all formal agreements.

Before they reached the plenary, proposals were discussed in the intermediate Negotiating Forum, which contained two delegates and two advisers from each party. However, the bulk of the MPNF's work was done in its Negotiating Council, which contained two delegates and two advisers from each party, and which was almost continuously in session between April and November. It was in the council that proposals were developed and compromises thrashed out before being sent for formal approval in the higher tiers of the body.

The issues before the Negotiating Council were almost identical to those discussed at CODESA and the MPNF built on the latter's work. However, in a new innovation, the Negotiating Council at the end of April resolved to appoint seven technical committees, staffed mostly by lawyers and other experts, to assist in formulating detailed proposals on specific matters.

As a result of agreements reached earlier by the Gender Advisory Committee of CODESA, at least one party delegate at each level of the MPNF had to be a woman.

In principle, the parties to the forum participated on an equal basis, irrespective of the size of their support base, with decisions taken by consensus. In practice, however, the ANC and NP developed a doctrine known as "sufficient consensus", which usually deemed bilateral ANC–NP agreement (sometimes reached in external or informal forums) "sufficient", regardless of any protests from minority parties.

As a result, the MPNF was still more dominated by the interests of the ANC and NP than CODESA had been.

Assassination of Chris Hani: April 1993

On 10 April 1993, a white extremist Assassination of Chris Hani, assassinated senior SACP and ANC leader Chris Hani outside Hani's home in Boksburg, Boksburg, Gauteng. Hani was extremely popular with the militant urban youth, a constituency whose commitment to a peaceful settlement was already tenuous, and his murder was potentially incendiary. However, Mandela's plea for calm, broadcast on national television, is viewed as having increased the status and credibility of the ANC, both internationally and among domestic moderates.

Thus, somewhat paradoxically, the incident helped accelerate consensus between the ANC and the government, and on 3 June the parties announced a date for democratic elections, to be held in April the next year.

Storming of the World Trade Centre: June 1993

On 25 June 1993, MPNF negotiations were dramatically interrupted when their Storming of Kempton Park World Trade Centre, venue was stormed by the right-wing Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB), whose supporters crashed through the glass front of the building in an armoured car and briefly took over the negotiations chamber. Both Mandela and de Klerk condemned the attack, and all but two of the 26 negotiating parties publicly rejected the secessionist overtones of the AWB's protest.

Concerned South Africans Group

In early October 1992,

the IFP initiated the formation of the Concerned South Africans Group (COSAG), an "unlikely alliance" between the IFP and other black traditionalists –

Lucas Mangope

Kgosi Lucas Manyane Mangope (27 December 1923 – 18 January 2018) was the leader of the Bantustan (homeland) of Bophuthatswana. The territory he ruled over was distributed between the Orange Free State – what is now Free State – and North W ...

of Bophuthatswana and Oupa Gqozo of Ciskei – and the white Conservative Party.

Buthelezi himself later called it "a motley gathering".

Buthelezi had been infuriated by the IFP's exclusion from the Record of Understanding, and in October 1992 had announced to a rally that the IFP would withdraw from further negotiations.

Although he walked back this threat and the IFP ultimately joined the MPNF, COSAG was formed to ensure that its members were not sidelined or played off against each other, as they believed they had been in the past. Moreover, its members were in broad agreement in favour of federalism and political self-determination, principles that even the NP increasingly appeared to have abandoned, and they sought to present a united front in advocating for those principles.

Notwithstanding COSAG's efforts, Buthelezi felt that the negotiations had become two-sided and that the IFP – and he personally – were being marginalised by the principle of sufficient consensus.

In June 1993, the IFP walked out of the MPNF, announcing its withdrawal from negotiations. What immediately precipitated the walk-out was an objection to the ANC–NP consensus on the date of the 1994 election.

The Ciskei and Bophuthatswana governments continued to participate in the forum until October 1993, when they also withdrew. At that time, COSAG was reconstituted as the Freedom Alliance, also incorporating far-right white groups of the Afrikaner Volksfront.

None of the Alliance's members participated in the remaining negotiations or ratified the proposals that emerged from them, but informal negotiations with the ANC and government continued on the sidelines of the MPNF.

Interim Constitution: November 1993

The final plenary of the MPNF was convened on 17–18 November 1993.

It ratified the

interim Constitution A provisional constitution, interim constitution or transitional constitution is a constitution intended to serve during a transitional period until a permanent constitution is adopted. The following countries currently have,had in the past,such a c ...

in the early hours of the morning of 18 November 1993,

after a flurry of bilateral agreements on sensitive issues were concluded in quick succession on 17 November.

The MPNF's proposals and proposed electoral laws were adopted by the Tricameral Parliament, a concession to the NP's demand for legal continuity.

Thereafter, South Africa's transition to democracy was overseen by the multi-party Transitional Executive Council.

On the day of the council's inauguration in late 1993,

Mandela and de Klerk were travelling to Oslo, where they were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to end apartheid.

Political transition

Democratic elections: April 1994

In the run-up to the 1994 elections, a final stumbling block was the continued boycott of the elections by the members of the Freedom Alliance. Shortly before the election, an international delegation, led by former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and former Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, British Foreign Secretary Peter Carington, 6th Baron Carrington, Peter Carington, visited South Africa to broker a resolution to the IFP's election boycott, or, failing that, to persuade the ANC and NP to delay the elections to avert possible violence.

Rejecting the call to delay, the ANC and NP offered Buthelezi additional guarantees of the status of the List of Zulu kings, Zulu monarchy, and Buthelezi's IFP agreed to participate in the elections. Its name was added to the ballot papers, which had already been printed, by means of a sticker added manually to the bottom of each slip.

Opposition from other wings of the former COSAG was also neutralised: in March, days after Mangope announced that his "country" would not participate in the elections, his administration was effectively paralysed by the 1994 Bophuthatswana crisis, Bophutatswana crisis.

In the aftermath of the crisis, which was considered humiliating by some far-right leaders, the Freedom Front Plus, Freedom Front split from the Afrikaner Volksfront and confirmed its intention to contest the elections, ensuring that far-right Afrikaners would be represented in the new government.

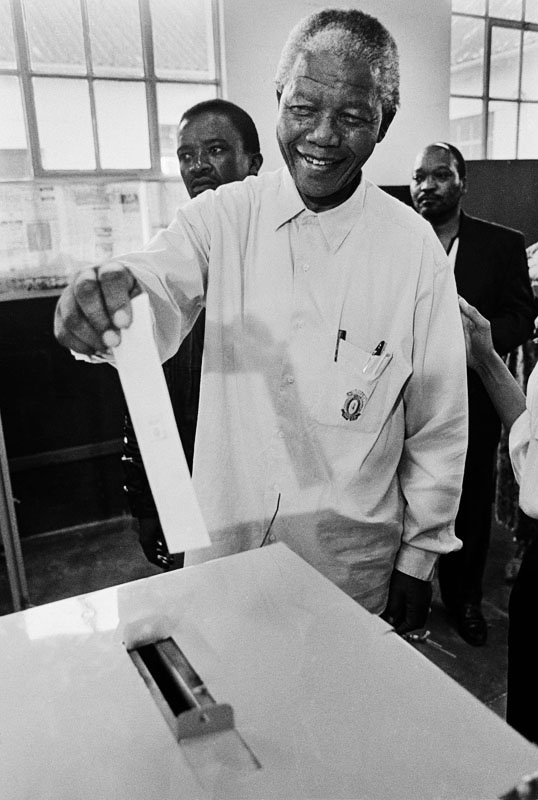

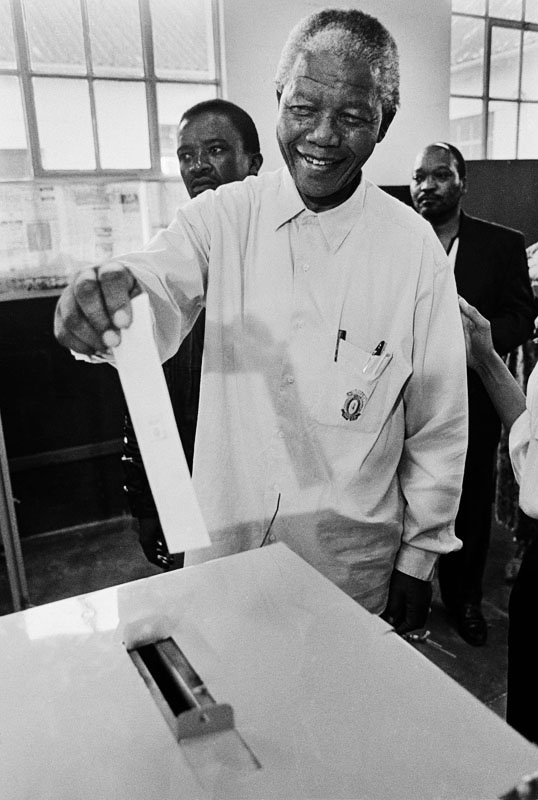

On 27 April 1994, a date later celebrated as Freedom Day (South Africa), Freedom Day, South Africa held its 1994 South African general election, first elections under universal suffrage. The ANC won a resounding majority in the election and Mandela was elected President of South Africa, president. Six other parties were represented in the national legislature and among them, under the provisions of the interim Constitution, the NP and IFP won enough seats to participate alongside the ANC in a single-term coalition Government of National Unity (South Africa), Government of National Unity. Also in terms of a constitutional provision, de Klerk was appointed Mandela's second deputy president.

Aftermath

In 1995, the government passed legislation mandating the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (South Africa), Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a restorative justice tribunal which over the next three years investigated human rights violations under apartheid. The Constitution of South Africa, final Constitution was negotiated by the Constitutional Assembly, working from principles contained in the interim Constitution, and was provisionally adopted in 8 May 1996. The next day, de Klerk announced that the NP would withdraw from the Government of National Unity, calling the moment a "natural watershed".

Following changes made to the text at the instruction of the new Constitutional Court of South Africa, Constitutional Court, the final Constitution came into effect in February 1997 and 1999 South African general election, successful elections were held under its provisions in June 1999, consolidating the ANC's long-lived majority in the national legislature.

See also

References

Further reading

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

Negotiation documents

Text of the bilateral accordsText of the CODESA Declaration of IntentTerms of reference of CODESA working groupsDocuments of MPNF plenaryText of the interim Constitution

Other media

Constitution Hill Trust series on the negotiationsShort documentary on the Groote Schuur meeting*

*

Mandela's replySpecial issue of the ''African Communist'' on the sunset clause proposal

{{Nelson Mandela

Democratization

Events associated with apartheid

Negotiation

Nelson Mandela

Peace processes

On 2–4 May 1990, the ANC met with the South African government at the

On 2–4 May 1990, the ANC met with the South African government at the  Perhaps even more obstructive were disagreements about how the constitution itself was to be devised and passed into law. The ANC's enduring proposal had been that the task should be entrusted to a constituent assembly, democratically elected under the principle of one man, one vote. Although it recognised that the white minority would not abide a constitution-making process without any guarantees of its outcomes, the ANC believed that the pre-agreement of constitutional principles at CODESA should suffice for such guarantees. On the other hand, the NP held that the constitution should be negotiated among parties, in a forum resembling CODESA, and then adopted by the existing (and NP-dominated) legislature – both to protect minority interests, and to ensure Revolutionary breach of legal continuity, legal continuity. Alternatively, if a constituent assembly was unavoidable, it insisted that approval of the new constitution should require the support of a three-quarters majority in the assembly, rather than the two-thirds majority proposed by the ANC. Thereafter, it sought a transitional system of government under a compulsory coalition, with the cabinet drawn equally from each of the three major parties and a presidency that would rotate among them. The IFP also opposed the notion of a democratically elected constituent assembly, although for different reasons.

As a result of this deadlock, with consensus evidently out of reach, discussions stalled and the plenary was dissolved on the second day of meetings, 16 May – although the parties reaffirmed their commitment to the Declaration of Intent, and expected to re-convene once the major disagreements had been resolved outside the plenary.

Perhaps even more obstructive were disagreements about how the constitution itself was to be devised and passed into law. The ANC's enduring proposal had been that the task should be entrusted to a constituent assembly, democratically elected under the principle of one man, one vote. Although it recognised that the white minority would not abide a constitution-making process without any guarantees of its outcomes, the ANC believed that the pre-agreement of constitutional principles at CODESA should suffice for such guarantees. On the other hand, the NP held that the constitution should be negotiated among parties, in a forum resembling CODESA, and then adopted by the existing (and NP-dominated) legislature – both to protect minority interests, and to ensure Revolutionary breach of legal continuity, legal continuity. Alternatively, if a constituent assembly was unavoidable, it insisted that approval of the new constitution should require the support of a three-quarters majority in the assembly, rather than the two-thirds majority proposed by the ANC. Thereafter, it sought a transitional system of government under a compulsory coalition, with the cabinet drawn equally from each of the three major parties and a presidency that would rotate among them. The IFP also opposed the notion of a democratically elected constituent assembly, although for different reasons.

As a result of this deadlock, with consensus evidently out of reach, discussions stalled and the plenary was dissolved on the second day of meetings, 16 May – although the parties reaffirmed their commitment to the Declaration of Intent, and expected to re-convene once the major disagreements had been resolved outside the plenary.