Naval history of World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At the beginning of

/ref> It had over 15 battleships and battlecruisers, 7 aircraft carriers, 66 cruisers, 164 destroyers and 66 submarines. With a massive merchant navy, about a third of the world total, it also dominated shipping. The Royal Navy fought in every theatre from the Atlantic, Mediterranean, freezing Northern routes to Russia and the Pacific ocean. In the course of the war the

The

The

Feldgrau.com In 1939–1945 German shipyards launched 1,162 U-boats, of which 785 were destroyed during the war (632 at sea) along with the loss of 30,000 crew. The British anti-submarine ships and aircraft accounted for over 500 kills. At the end of the war, 156 U-boats surrendered to the Allies, while the crews scuttled 221 others, chiefly in German ports. In terms of effectiveness, German and other Axis submarines sank 2828 merchant ships totaling 14.7 million tons (11.7 million British); many more were damaged. The use of convoys dramatically reduced the number of sinkings, but convoys made for slow movement and long delays at both ends, and thus reduced the flow of Allied goods. German submarines also sank 175 Allied warships, mostly British, with 52,000 Royal Navy sailors killed.

naval-history.net At the end the RN had 16 battleships, 52 carriers—though most of these were small escort or merchant carriers—62 cruisers, 257 destroyers, 131 submarines and 9,000 other ships. During the war the Royal Navy lost 278 major warships and more than 1,000 small ones. There were 200,000 men (including reserves and marines) in the navy at the start of the war, which rose to 939,000 by the end. 51,000 RN sailors were killed and a further 30,000 from the merchant services. The WRNS was reactivated in 1938 and their numbers rose to a peak of 74,000 in 1944. The Royal Marines reached a maximum of 78,000 in 1945, having taken part in all the major landings.

The small but modern Dutch fleet had as its primary mission the defence of the oil-rich

The small but modern Dutch fleet had as its primary mission the defence of the oil-rich

The

The

U.S. Submarines in World War II

Furthermore, they played important reconnaissance roles, as at the battles of the Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf, when they gave accurate and timely warning of the approach of the Japanese fleet. Submarines operated from secure bases in Fremantle, Australia; Pearl Harbor;

excerpt and text search vol 5

500pp each; includes warships and civilian ships from Allied, Axis, and neutral nations. Data is organized by month, then by geographical area, then by date. * Dear, Ian and M.R.D. Foot, eds. ''The Oxford companion to world war II'' (1995), comprehensive encyclopedia * Rohwer, Jürgen, and Gerhard Hümmelchen. ''Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two'' (Naval Institute Press, 2005) * , comprehensive naval encyclopedia * Symonds, Craig L. ''World War II at Sea: A Global History'' (2018), 770pp

complete text dissertation version, 2 vol., 2015

* Boyd, Carl, and Akihiko Yoshida. ''The Japanese Submarine Force and World War II'' (1995) *Carpenter, Ronald H. "Admiral Mahan, 'narrative fidelity,' and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor." ''Quarterly Journal of Speech'' (1986) 72#3 pp: 290-305. * Dull, Paul S. ''Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–45'' (1978). * Dunnigan, James F., and Albert A. Nofi. ''The Pacific War Encyclopedia.'' Facts on File, 1998. 2 vols. 772p. * * Evans, David C., ed. ''The Japanese Navy in World War II'' (2017); 17 essays by Japanese scholars. * Ford, Douglas. ''The elusive enemy: US naval intelligence and the imperial Japanese fleet.'' (Naval Institute Press, 2011). * Gailey, Harry A. ''The War in the Pacific: From Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay'' (1995

online

* Hopkins, William B. ''The Pacific War: The Strategy, Politics, and Players that Won the War'' (2010) * Inoguchi, Rikihei, Tadashi Nakajima, and Robert Pineau. ''The Divine Wind''. Ballantine, 1958. Kamikaze. * Kirby, S. Woodburn ''The War Against Japan''. 4 vols. London: H.M.S.O., 1957–1965. Official Royal Navy history. * * Marder, Arthur. ''Old Friends, New Enemies: The Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, vol. 2: The Pacific War, 1942–1945'' (1990) * * Morison, Samuel Eliot, ''

online

* Morison, Samuel Eliot. ''History of United States Naval Operation in World War II'' in 15 Volumes (1947–62, often reprinted). vol 1 ''The Battle of the Atlantic, September 1939 – May 1943''; vol 2 ''Operations in North African Waters, October 1942 – June 1943''; vol 9. ''Sicily – Salerno – Anzio, January 1943 – June 1944''; vol 10. ''The Atlantic Battle Won, May 1943 – May 1945''; vol 11 "The Invasion of France and Germany, 1944–1945'' **Morison, Samuel Eliot. ''The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War'' (2007), condensed version * Offley, Edward. ''Turning the Tide: How a Small Band of Allied Sailors Defeated the U-boats and Won the Battle of the Atlantic'' (Basic Books, 2011) * O'Hara, Vincent P. ''The German Fleet at War, 1939–1945'' (Naval Institute Press, 2004) * Paterson, Lawrence. ''U-boats in the Mediterranean, 1941–1944.'' (Naval Institute Press, 2007) * Rodger, N. A. M. ''Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, Volume 3: 1815–1945'' (2009) * Roskill, S. W. ''War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 1: The Defensive'' London: HMSO, 1954; ''War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 2: The Period of Balance,'' 1956; ''War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 3: The Offensive, Part 1,'' 1960; ''War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 3: The Offensive, Part 2,'' 1961

** Roskill, S. W. ''The White Ensign: British Navy at War, 1939–1945'' (1960). summary * Runyan, Timothy J., and Jan M. Copes, eds. ''To die gallantly: the battle of the Atlantic'' (Westview Press, 1994) *Sarty, Roger, ''The Battle of the Atlantic: The Royal Canadian Navy's Greatest Campaign, 1939–1945'', (CEF Books, Ottawa, 2001) *Syrett, David. ''The Defeat of the German U-Boats: The Battle of the Atlantic'' (U of South Carolina Press, 1994.) * Terraine, John, ''Business in Great Waters'', (London 1987) The best single-volume study of the U-Boat Campaigns, 1917–1945 * Tomblin, Barbara Brooks. ''With Utmost Spirit: Allied Naval Operations in the Mediterranean, 1942–1945'' (2004

online

* Tomblin, Barbara Brooks. "The Naval War in the Mediterranean." in ''A Companion to World War II'' (2013): 222+ * Vat, Dan van der. ''The Atlantic Campaign'' (1988)

* U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, ''Publications'

excerpt and text search

* Murfett, Malcolm. ''The First Sea Lords from Fisher to Mountbatten'' (1995), British * Padfield, Peter. ''Dönitz: The Last Führer'' (2001) * Potter, E. B. ''Bull Halsey'' (1985). * Potter, E. B. ''Nimitz''. (1976). * Potter, John D. ''Yamamoto'' (1967). * Roskill, Stephen. ''Churchill and the Admirals'' (1977). * Simpson, Michael. ''Life of Admiral of the Fleet Andrew Cunningham'' (Routledge, 2004) * Stephen, Martin. ''The Fighting Admirals: British Admirals of the Second World War'' (1991). * Ugaki, Matome, Donald M. Goldstein, and Katherine V. Dillon. ''Fading Victory: The Diary of Admiral Matome Ugaki, 1941–1945'' (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991), a primary source * Wukovits, John. ''Admiral" Bull" Halsey: The Life and Wars of the Navy's Most Controversial Commander'' (Macmillan, 2010)

"The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia" compiled by Kent G. Budge

4000 short articles {{Authority control

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

was the strongest navy in the world, with the largest number of warships built and with naval bases across the globe.Fleets 1939/ref> It had over 15 battleships and battlecruisers, 7 aircraft carriers, 66 cruisers, 164 destroyers and 66 submarines. With a massive merchant navy, about a third of the world total, it also dominated shipping. The Royal Navy fought in every theatre from the Atlantic, Mediterranean, freezing Northern routes to Russia and the Pacific ocean. In the course of the war the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

grew tremendously as the United States was faced with a two-front war on the seas.Stephen Howarth, ''To Shining Sea: a History of the United States Navy, 1775–1998'' (1999) By the end of World War II the U.S Navy was larger than any other navy in the world.

Main navies

United States

The

The United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

grew rapidly during World War II from 1941–45, and played a central role in the Pacific theatre in the war against Japan. It also played a major supporting role, alongside the Royal Navy, in the European war against Germany.

The Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

(IJN) sought naval superiority in the Pacific by sinking the main American battle fleet at Pearl Harbor, which was built around its battleships. The December 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

did knock out the battle fleet, but it did not touch the aircraft carriers, which became the mainstay of the rebuilt fleet.

Naval doctrine had to be changed overnight. The United States Navy (like the IJN) had followed Alfred Thayer Mahan's emphasis on concentrated groups of battleships as the main offensive naval weapons. The loss of the battleships at Pearl Harbor forced Admiral Ernest J. King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the Un ...

, the head of the Navy, to place primary emphasis on the small number of aircraft carriers.

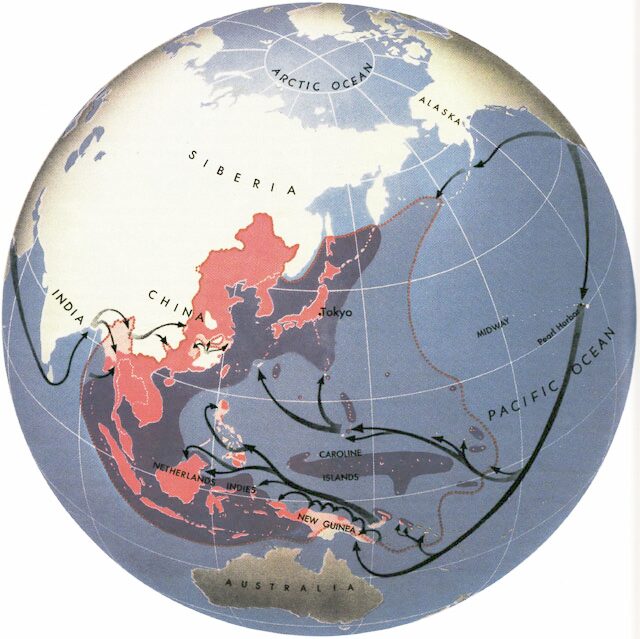

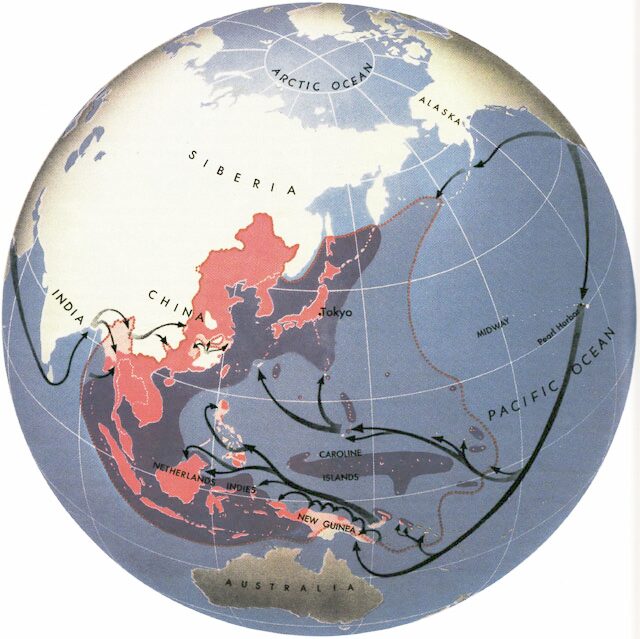

The U.S. Navy grew tremendously as it faced a two-front war on the seas. It achieved notable acclaim in the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

, where it was instrumental to the Allies' successful "island hopping

Leapfrogging, also known as island hopping, was a military strategy employed by the Allies in the Pacific War against the Empire of Japan during World War II.

The key idea is to bypass heavily fortified enemy islands instead of trying to captu ...

" campaign. The U.S. Navy fought five great battles with the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN): the Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea, from 4 to 8 May 1942, was a major naval battle between the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and naval and air forces of the United States and Australia. Taking place in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, the batt ...

, the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under Adm ...

, the Battle of the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20, 1944) was a major naval battle of World War II that eliminated the Imperial Japanese Navy's ability to conduct large-scale carrier actions. It took place during the United States' amphibious invas ...

, the Battle of Leyte Gulf

The Battle of Leyte Gulf ( fil, Labanan sa golpo ng Leyte, lit=Battle of Leyte gulf; ) was the largest naval battle of World War II and by some criteria the largest naval battle in history, with over 200,000 naval personnel involved. It was fou ...

, and the Battle of Okinawa

The , codenamed Operation Iceberg, was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa by United States Army (USA) and United States Marine Corps (USMC) forces against the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The initial invasion of ...

.

By war's end in 1945, the United States Navy had added thousands of new ships, including 18 aircraft carriers and 8 battleships, and had over 70% of the world's total numbers and total tonnage of naval vessels of 1,000 tons or greater.Weighing the U.S. Navy Defense & Security Analysis, Volume 17, Issue 3 December 2001, pp. 259 - 265. At its peak, the U.S. Navy was operating 7,601 ships on V-J Day

Victory over Japan Day (also known as V-J Day, Victory in the Pacific Day, or V-P Day) is the day on which Imperial Japan surrendered in World War II, in effect bringing the war to an end. The term has been applied to both of the days on ...

in August 1945, including 28 aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s, 23 battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s, 71 escort carrier

The escort carrier or escort aircraft carrier (U.S. hull classification symbol CVE), also called a "jeep carrier" or "baby flattop" in the United States Navy (USN) or "Woolworth Carrier" by the Royal Navy, was a small and slow type of aircraft ...

s, 72 cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s, over 232 submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s, 377 destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s, and thousands of amphibious, supply and auxiliary ships.

1941–1942

The American war plan was Rainbow 5 and was completed on 14 May 1941. It assumed that the United States was allied with Britain and France and provided for offensive operations by American forces in Europe, Africa, or both. The assumptions and plans for Rainbow 5 were discussed extensively in thePlan Dog memo

The Plan Dog memorandum was a 1940 American government document written by Chief of Naval Operations Harold Stark. It has been called "one of the best known documents of World War II." Confronting the problem of an expected two-front war against ...

, which concluded ultimately that the United States would adhere to a Europe first Europe first, also known as Germany first, was the key element of the grand strategy agreed upon by the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II. According to this policy, the United States and the United Kingdom would use the prepon ...

strategy, making the war against Germany a higher priority than the war against Japan. However President Roosevelt did not approve the plan—he wanted to play it by ear. The Navy wanted to make Japan the top target, and in 1941–1943 the U.S. in effect was mostly fighting a naval war against Japan, in addition to its support for Army landings in North Africa, Sicily and Italy in 1942–1943.

U.S. strategy in 1941 was to deter Japan from further advances toward British, Dutch, French and American territories to the South. When the Allies cut off sales of oil to Japan, it lost 90% of its fuel supply for airplanes and warships. It had stocks that would last a year or two. It had to compromise or fight to recapture British and Dutch wells to the South. in November 1941, U.S. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

explained the American air war strategy to the press—it was top secret and not for publication:

:We are preparing for an offensive war against Japan, whereas the Japs believe we are preparing only to defend the Philippines. ...We have 35 Flying Fortresses already there—the largest concentration anywhere in the world. Twenty more will be added next month, and 60 more in January....If war with the Japanese does come, we'll fight mercilessly. Flying fortresses will be dispatched immediately to set the paper cities of Japan on fire. There won't be any hesitation about bombing civilians—it will be all-out.

Marshall was talking about long-range B-17 bombers based in the Philippines, which were within range of Tokyo. After Japan captured the Philippines in early 1942, American strategy refocused on a naval war focusing on the capture of islands close enough for the intensive bombing campaign Marshall spoke about. In 1944, the Navy captured Saipan

Saipan ( ch, Sa’ipan, cal, Seipél, formerly in es, Saipán, and in ja, 彩帆島, Saipan-tō) is the largest island of the Northern Mariana Islands, a Commonwealth (U.S. insular area), commonwealth of the United States in the western Pa ...

and the Mariana Islands, which were within range of the new B-29 bombers.

After its Pearl Harbor victory in early December the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) seemed unstoppable because it outnumbered and outgunned the disorganized Allies—US, Britain, Netherlands, Australia, China. London and Washington both believed in Mahanian doctrine, which stressed the need for a unified fleet. However, in contrast to the cooperation achieved by the armies, the Allied navies failed to combine or even coordinate their activities until mid-1942. Tokyo also believed in Mahan, who said command of the seas—achieved by great fleet battles—was the key to sea power. Therefore, the IJN kept its main strike force together under Admiral Yamamoto and won a series of stunning victories over the Americans and British in the 90 days after Pearl Harbor.

Outgunned at sea, with its big guns lying at the bottom of Pearl Harbor, the American strategy for victory required a slow retreat or holding action against the IJN until the much greater industrial potential of the US could be mobilized to launch a fleet capable of projecting Allied power to the enemy heartland.

Midway

The Battle of Midway, together with the Guadalcanal campaign, marked the turning point in thePacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. Between June 4–7, 1942, the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

decisively defeated a Japanese naval force that had sought to lure the U.S. carrier fleet into a trap at Midway Atoll

Midway Atoll (colloquial: Midway Islands; haw, Kauihelani, translation=the backbone of heaven; haw, Pihemanu, translation=the loud din of birds, label=none) is a atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. Midway Atoll is an insular area of the Unit ...

. The Japanese fleet lost four aircraft carriers and a heavy cruiser to the U.S. Navy's one American carrier and a destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

. After Midway, and the exhausting attrition of the Solomon Islands campaign

The Solomon Islands campaign was a major campaign of the Pacific War of World War II. The campaign began with Japanese landings and occupation of several areas in the British Solomon Islands and Bougainville, in the Territory of New Guinea, du ...

, Japan's shipbuilding and pilot training programs were unable to keep pace in replacing their losses while the U.S. steadily increased its output in both areas. Military historian John Keegan

Sir John Desmond Patrick Keegan (15 May 1934 – 2 August 2012) was an English military historian, lecturer, author and journalist. He wrote many published works on the nature of combat between prehistory and the 21st century, covering land, ...

called the Battle of Midway "the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare."

Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal, fought from August 1942 to February 1943, was the first major Allied offensive of the war in the Pacific Theater. This campaign saw American air, naval and ground forces (later augmented by Australians and New Zealanders) in a six months campaign slowly overwhelm determined Japanese resistance. Guadalcanal was the key to control theSolomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

, which both sides saw as strategically essential. Both sides won some battles but both sides were overextended in terms of supply lines.

The rival navies fought seven battles, with the two sides dividing the victories. They were: Battle of Savo Island

The Battle of Savo Island, also known as the First Battle of Savo Island and, in Japanese sources, as the , and colloquially among Allied Guadalcanal veterans as the Battle of the Five Sitting Ducks, was a naval battle of the Solomon Islands ca ...

, Battle of the Eastern Solomons

The naval Battle of the Eastern Solomons (also known as the Battle of the Stewart Islands and, in Japanese sources, as the Second Battle of the Solomon Sea) took place on 24–25 August 1942, and was the third carrier battle of the Pacific ca ...

, Battle of Cape Esperance

The Battle of Cape Esperance, also known as the Second Battle of Savo Island and, in Japanese sources, as the , took place on 11–12 October 1942, in the Pacific campaign of World War II between the Imperial Japanese Navy and United States Na ...

, Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, fought during 25–27 October 1942, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Santa Cruz or Third Battle of Solomon Sea, in Japan as the Battle of the South Pacific ( ''Minamitaiheiyō kaisen''), was the fourt ...

, Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, sometimes referred to as the Third and Fourth Battles of Savo Island, the Battle of the Solomons, the Battle of Friday the 13th, or, in Japanese sources, the , took place from 12 to 15 November 1942, and was t ...

, Battle of Tassafaronga

The Battle of Tassafaronga, sometimes referred to as the Fourth Battle of Savo Island or, in Japanese sources, as the , was a nighttime naval battle that took place on November 30, 1942, between United States Navy and Imperial Japanese Navy warsh ...

and Battle of Rennell Island

The took place on 29–30 January 1943. It was the last major naval engagement between the United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy during the Guadalcanal Campaign of World War II. It occurred in the South Pacific between Rennell Is ...

. Both sides pulled out their aircraft carriers, as they were too vulnerable to land-based aviation.

1943

In preparation of the recapture of the Philippines, the Navy started the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign to retake the Gilbert and Marshall Islands from the Japanese in summer 1943. Enormous effort went into recruiting and training sailors and Marines, and building warships, warplanes and support ships in preparation for a thrust across the Pacific, and to support Army operations in the Southwest Pacific, as well as in Europe and North Africa.1944

The Navy continued its long movement west across the Pacific, seizing one island base after another. Not every Japanese stronghold had to be captured; some, like the big bases at Truk, Rabaul and Formosa were neutralized by air attack and then simply leapfrogged. The ultimate goal was to get close to Japan itself, then launch massive strategic air attacks and finally an invasion. The US Navy did not seek out the Japanese fleet for a decisive battle, as Mahanian doctrine would suggest; the enemy had to attack to stop the inexorable advance. The climax of the carrier war came at theBattle of the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20, 1944) was a major naval battle of World War II that eliminated the Imperial Japanese Navy's ability to conduct large-scale carrier actions. It took place during the United States' amphibious invas ...

. Taking control of islands that could support airfields within B-29 range of Tokyo was the objective. 535 ships began landing 128,000 Army and Marine invaders on June 15, 1944, in the Mariana and Palau Islands. The Japanese launched an ill-coordinated attack on the larger American fleet; its planes operated at extreme ranges and could not keep together, allowing them to be easily shot down in what Americans jokingly called the "Great Marianas Turkey Shoot."

Japan had now lost most of its offensive capabilities, and the U.S. had air bases on Guam, Saipan and Tinian for B-29 bombers targeted at Japan's home islands.

The final act of 1944 was the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the last naval battle in history in which the battle line of one navy "crossed the T" of the battle line of its enemy, enabling the crossing line to fire the full broadsides of its main batteries as against only the forward guns of only the enemy's lead ship. The Japanese plan was to lure the main body of the U.S. fleet away from the action at Leyte Gulf by decoying it with a dummy fleet far to the north, and then to close in on the U.S. Army and Marines landing at Leyte with a pincer movement of two squadrons of battleships, and annihilate them. The movements of these Japanese fleet components were terribly uncoordinated, resulting in piecemeal slaughter of Japanese fleet units in the Sibuyan Sea and the Surigao Strait (where "the T was crossed"), but, although the ruse to lure the main body of the U.S. fleet away had worked to perfection, the Japanese were unaware of this, with the result that an overwhelmingly superior remaining force of Japanese battleships and cruisers that massively outnumbered and outgunned the few U.S. fleet units left behind at Leyte, thinking it was sailing into the jaws of the more powerful U.S. main body, turned tail and ran away without exploiting its hard-won advantage. After which Japan had now lost all its offensive naval capability.

Okinawa 1945

Okinawa was the last great battle of the entire war. The goal was to make the island into a staging area for theinvasion of Japan

Operation Downfall was the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of the Japanese home islands near the end of World War II. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ...

scheduled for fall 1945. It was just 350 miles (550 km) south of the Japanese home islands. Marines and soldiers landed on 1 April 1945, to begin an 82-day campaign which became the largest land-sea-air battle in history and was noted for the ferocity of the fighting and the high civilian casualties with over 150,000 Okinawans losing their lives. Japanese kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

pilots exacted the largest loss of ships in U.S. naval history with the sinking of 38 and the damaging of another 368. Total U.S. casualties were over 12,500 dead and 38,000 wounded, while the Japanese lost over 110,000 men. The fierce combat and high American losses led the Navy to oppose an invasion of the main islands. An alternative strategy was chosen: using the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

to induce surrender.

Naval technology: US vs Japan

Technology and industrial power proved decisive. Japan failed to exploit its early successes before the immense potential power of the Allies could be brought to bear. In 1941 the Japanese Zero fighter had a longer range and better performance than rival American warplanes, and the pilots had more experience in the air. But Japan never improved the Zero and by 1944 the Allied navies were far ahead of Japan in both quantity and quality, and ahead of Germany in quantity and in putting advanced technology to practical use. High tech innovations arrived with dizzying rapidity. Entirely new weapons systems were invented—like the landing ships, such as the 3,000-ton LST ("Landing Ship, Tank

Landing Ship, Tank (LST), or tank landing ship, is the naval designation for ships first developed during World War II (1939–1945) to support amphibious operations by carrying tanks, vehicles, cargo, and landing troops directly onto shore with ...

") that carried 25 tanks thousands of miles and landed them right on the assault beaches - invented by the British and delivered by industrial capacity of the US. Furthermore, older weapons systems were constantly upgraded and improved. Obsolescent airplanes, for example, received more powerful engines and more sensitive radar sets. One impediment to progress was that admirals who had grown up with great battleships and fast cruisers had a hard time adjusting their war-fighting doctrines to incorporate the capability and flexibility of the rapidly evolving new weapons systems.

Ships

The ships of the American and Japanese forces were closely matched at the beginning of the war. By 1943 the American qualitative edge was winning battles; by 1944 the American quantitative advantage made the Japanese position hopeless. The German navy, distrusting its Japanese ally, ignored Hitler's orders to cooperate and failed to share its expertise in radar and radio. Thus the Imperial Navy was further handicapped in the technological race with the Allies (who did cooperate with each other). The United States economic base was ten times larger than Japan's, and its technological capabilities also significantly greater, and it mobilized engineering skills much more effectively than Japan, so that technological advances came faster and were applied more effectively to weapons. Above all, American admirals adjusted their doctrines of naval warfare to exploit the advantages. The quality and performance of the warships of Japan were initially comparable to those of the US. The Americans were supremely, and perhaps overly, confident in 1941. Pacific commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz boasted he could beat a bigger fleet because of "...our superior personnel in resourcefulness and initiative, and the undoubted superiority of much of our equipment." As Willmott notes, it was a dangerous and ill-founded assumption. Nimitz would later make good on his boast by defeating a larger Japanese force in theBattle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under Adm ...

and turning the tide in the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

.

Battleships

The American battleships before Pearl Harbor could fire salvos of nine 2,100-pound armor-piercing shells every minute to a range of 35,000 yards (19 miles). No ship except another battleship had the thick armor that could withstand that kind of firepower. When intelligence reported that Japan had secretly built even more powerful battleships, Washington responded with four ''Iowa''-class battleships. The "big-gun" admirals on both sides dreamed of a great shootout at twenty-mile (32 km) range, in which carrier planes would be used only for spotting the mighty guns. Their doctrine was utterly out of date. A plane like the Grumman TBF Avenger could drop a 2,000-pound bomb on a battleship at a range of hundreds of miles. An aircraft carrier cost less, required about the same number of personnel, was just as fast, and could easily sink a battleship. During the war the battleships found new missions: they were platforms holding all together dozens of anti-aircraft guns and eight or nine 14-inch or 16-inch long-range guns used to blast land targets before amphibious landings. Their smaller 5-inch guns, and the 4,800 3-inch to 8-inch guns on cruisers and destroyers also proved effective at bombarding landing zones. After a short bombardment of Tarawa island in November 1943, Marines discovered that the Japanese defenders were surviving in underground shelters. It then became routine doctrine to thoroughly work over beaches with thousands of high-explosive and armor-piercing shells. The bombardment would destroy some fixed emplacements and kill some troops. More important, it severed communication lines, stunned and demoralized the defenders, and gave the landing parties fresh confidence. After the landing, naval gunfire directed by ground observers would target any enemy pillboxes that were still operational. The sinking of the battleships at Pearl Harbor proved a blessing in deep disguise, for after they were resurrected and assigned their new mission they performed well. (Absent Pearl Harbor, big-gun admirals likeRaymond Spruance

Raymond Ames Spruance (July 3, 1886 – December 13, 1969) was a United States Navy admiral during World War II. He commanded U.S. naval forces during one of the most significant naval battles that took place in the Pacific Theatre: the Battle ...

might have followed prewar doctrine and sought a surface battle in which the Japanese would have been very hard to defeat.)

Naval aviation

In World War I the US Navy explored aviation, both land-based and carrier based. However, the Navy nearly abolished aviation in 1919 when AdmiralWilliam S. Benson

William Shepherd Benson (25 September 1855 – 20 May 1932) was an admiral in the United States Navy and the first chief of naval operations (CNO), holding the post throughout World War I.

Early life and career

Born in Bibb County, Georgi ...

, the reactionary Chief of Naval Operations, could not "conceive of any use the fleet will ever have for aviation", and he secretly tried to abolish the Navy's Aviation Division. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt reversed the decision because he believed aviation might someday be "the principal factor" at sea with missions to bomb enemy warships, scout enemy fleets, map minefields, and escort convoys. Grudgingly allowing it a minor mission, the Navy slowly built up its aviation. In 1929 it had one carrier (), 500 pilots and 900 planes; by 1937 it had 5 carriers (the , , ''Ranger'', and ), 2000 pilots and 1000 much better planes. With Roosevelt now in the White House, the tempo soon quickened. One of the main relief agencies, the PWA, made building warships a priority. In 1941 the U.S. Navy with 8 carriers, 4,500 pilots and 3,400 planes had more air power than the Japanese Navy.

Nazi Germany

Submarines

Germany's main naval weapon was theU-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

; its main mission was to cut off the flow of supplies and munitions reaching Britain by sea. Submarine attacks on Britain's vital maritime supply routes in the "Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

" started immediately at the outbreak of war. Although they were hampered initially by the lack of well-placed ports from which to operate, that changed when France fell in 1940 and Germany took control of all the ports in France and the Low Countries. The U-boats had such a high success rate at first that the period to early 1941 was known as the First Happy Time. The ''Kriegsmarine'' was responsible for coastal artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

From the Middle Ages until World War II, coastal artillery and naval artillery in the form of c ...

protecting major ports and possible invasion points, and also handled anti-aircraft batteries protecting major ports.Organization of the Kriegsmarine in the West 1940–1945Feldgrau.com In 1939–1945 German shipyards launched 1,162 U-boats, of which 785 were destroyed during the war (632 at sea) along with the loss of 30,000 crew. The British anti-submarine ships and aircraft accounted for over 500 kills. At the end of the war, 156 U-boats surrendered to the Allies, while the crews scuttled 221 others, chiefly in German ports. In terms of effectiveness, German and other Axis submarines sank 2828 merchant ships totaling 14.7 million tons (11.7 million British); many more were damaged. The use of convoys dramatically reduced the number of sinkings, but convoys made for slow movement and long delays at both ends, and thus reduced the flow of Allied goods. German submarines also sank 175 Allied warships, mostly British, with 52,000 Royal Navy sailors killed.

Surface fleet

The German fleet was involved in many operations, starting with theInvasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

. Also in 1939, it sank the British aircraft carrier and the battleship , while losing the at the Battle of the River Plate

The Battle of the River Plate was fought in the South Atlantic on 13 December 1939 as the first naval battle of the Second World War. The Kriegsmarine heavy cruiser , commanded by Captain Hans Langsdorff, engaged a Royal Navy squadron, command ...

.

In April 1940, the German navy was heavily involved in the invasion of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, where it lost the heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

, two light cruisers, and ten destroyers. In return it sank the British aircraft carrier and some smaller ships.

United Kingdom

At the start of the war, the Royal Navy was the largest navy in the world. In the critical years 1939–43 it was under the command ofFirst Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed ...

Admiral Sir Dudley Pound

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Alfred Dudley Pickman Rogers Pound, (29 August 1877 – 21 October 1943) was a British senior officer of the Royal Navy. He served in the First World War as a battleship commander, taking part in the Battle of Jutland ...

(1877–1943).

As a result of the earlier changes the Royal Navy entered the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

as a heterogeneous force of World War I veterans, inter-war ships limited by close adherence to treaty restrictions and later unrestricted designs. Though smaller and relatively older than it was during World War I, it remained the major naval power up until 1944-45 when it was overtaken by the American navy.

At the start of World War II, Britain's global commitments were reflected in the Navy's deployment. Its first task remained the protection of trade, since Britain was heavily dependent upon imports of food and raw materials, and the global empire was also interdependent. The navy's assets were allocated between various fleets and stations.

There are sharply divided opinions of Pound's leadership. His greatest achievement was his successful campaign against German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

activity and the winning of the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, the civilian head of the Navy (1939–40) and of all the forces as Prime Minister (1940–45) worked with him closely on naval strategies; he was dubbed "Churchill's anchor". He blocked Churchill's scheme of sending a battle fleet into the Baltic early in the war. However his judgment has been challenged regarding his micromanagement, the failed Norwegian Campaign in 1940, his dismissal of Admiral Dudley North in 1940, Japan's sinking of the ''Repulse'' and the ''Prince of Wales'' by air attack off Malaya in late 1941, and the failure in July 1942 to disperse Convoy PQ 17

PQ 17 was the code name for an Allied Arctic convoy during the Second World War. On 27 June 1942, the ships sailed from Hvalfjörður, Iceland, for the port of Arkhangelsk in the Soviet Union. The convoy was located by German forces on 1 July, aft ...

under German attack.

During the early phases of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the Royal Navy provided critical cover during British evacuations from Norway (where an aircraft carrier and 6 destroyers were lost but 338,000 men were evacuated), from Dunkirk (where 7,000 RN men were killed) and at the Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (german: Luftlandeschlacht um Kreta, el, Μάχη της Κρήτης), codenamed Operation Mercury (german: Unternehmen Merkur), was a major Axis airborne and amphibious operation during World War II to capture the island ...

. In the latter operation Admiral Cunningham ran great risks to extract the Army, and saved many men to fight another day. The prestige of the Navy suffered a severe blow when the battlecruiser ''Hood'' was sunk by the German battleship ''Bismarck'' in May 1941. Although the ''Bismarck'' was sunk a few days later, public pride in the Royal Navy was severely damaged as a result of the loss of the "mighty ''Hood''".

The RN carried out a bombardment of Oran in Algeria against the French Mediterranean Fleet

The French Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, also known as CECMED (French for ''Commandant en chef pour la Méditerranée'') is a French Armed Forces regional commander. He commands the zone, the region and the Mediterranean maritime ''arrondiss ...

. In the attack on Taranto

The Battle of Taranto took place on the night of 11–12 November 1940 during the Second World War between British naval forces, under Admiral Andrew Cunningham, and Italian naval forces, under Admiral Inigo Campioni. The Royal Navy launched ...

torpedo bombers sank three Italian battleships in their naval base at Taranto and in March 1941 it sank three cruisers and two destroyers at Cape Matapan

Cape Matapan ( el, Κάβο Ματαπάς, Maniot dialect: Ματαπά), also named as Cape Tainaron or Taenarum ( el, Ακρωτήριον Ταίναρον), or Cape Tenaro, is situated at the end of the Mani Peninsula, Greece. Cape Matapa ...

. The RN carried out an evacuation of troops from Greece to Crete and then from that island. In this the navy lost three cruisers and six destroyers but rescued 30,000 men.

The RN was vital in interdicting Axis supplies to North Africa and in the resupply of its base in Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

. The losses in Operation Pedestal were high but the convoy got through.

The Royal Navy was also vital in guarding the sea lanes that enabled British forces to fight in remote parts of the world such as North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

and the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

. Convoys were used from the start of the war and anti-submarine hunting patrols used. From 1942, responsibility for the protection of Atlantic convoys was divided between the various allied navies: the Royal Navy being responsible for much of the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans. Suppression of the U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

threat was an essential requirement for the invasion of northern Europe: the necessary armies could not otherwise be transported and resupplied. During this period the Royal Navy acquired many relatively cheap and quickly built escort vessels.

The defence of the ports and harbours and keeping sea-lanes around the coast open was the responsibility of Coastal Forces

Coastal Forces was a division of the Royal Navy initially established during World War I, and then again in World War II under the command of Rear-Admiral, Coastal Forces. It remained active until the last minesweepers to wear the "HM Coastal Fo ...

and the Royal Naval Patrol Service

The Royal Naval Patrol Service (RNPS) was a branch of the Royal Navy active during both the First and Second World Wars. The RNPS operated many small auxiliary vessels such as naval trawlers for anti-submarine and minesweeping operations to pro ...

.

Naval supremacy was vital to the amphibious operations carried out, such as the invasions of Northwest Africa (Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

), Sicily, Italy, and Normandy (Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The operat ...

). For Operation Neptune

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Ma ...

the RN and RCN supplied 958 of the 1213 warships and three quarters of the 4000 landing craft. The use of the Mulberry harbours allowed the invasion forces to be kept resupplied. There were also landings in the south of France in August.

During the war however, it became clear that aircraft carriers

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a n ...

were the new capital ship of naval warfare

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

, and that Britain's former naval superiority in terms of battleships had become irrelevant. Britain was an early innovator in aircraft carrier design, introducing armoured flight decks, in place of the now obsolete and vulnerable battleship. The Royal Navy was now dwarfed by its ally, the United States Navy. The successful invasion of Europe reduced the European role of the navy to escorting convoys and providing fire support for troops near the coast as at Walcheren

Walcheren () is a region and former island in the Dutch province of Zeeland at the mouth of the Scheldt estuary. It lies between the Eastern Scheldt in the north and the Western Scheldt in the south and is roughly the shape of a rhombus. The two ...

, during the battle of the Scheldt

The Battle of the Scheldt in World War II was a series of military operations led by the First Canadian Army, with Polish and British units attached, to open up the shipping route to Antwerp so that its port could be used to supply the Allies ...

.

The British Eastern Fleet had been withdrawn to East Africa because of Japanese incursions into the Indian Ocean. Despite opposition from the U.S. naval chief, Admiral Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the Un ...

, the Royal Navy sent a large task force to the Pacific (British Pacific Fleet

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation that saw action against Japan during the Second World War. The fleet was composed of empire naval vessels. The BPF formally came into being on 22 November 1944 from the remaining ships ...

). This required the use of wholly different techniques, requiring a substantial fleet support train, resupply at sea and an emphasis on naval air power and defence. In 1945 84 warships and support vessels were sent to the Pacific. It remains the largest foreign deployment of the Royal Navy. Their largest attack was on the oil refineries in Sumatra to deny Japanese access to supplies. However it also gave cover to the US landings on Okinawa and carried out air attacks and bombardment of the Japanese mainland.

At the start of the Second World War the RN had 15 battleships and battlecruisers with five more battleships under construction, and 66 cruisers with another 23 under construction. To 184 destroyers with 52 more under construction a further 50 old destroyers (and other smaller craft) were obtained from the US in exchange for US access to bases in British territories (Destroyers for Bases Agreement

The destroyers-for-bases deal was an agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom on September 2, 1940, according to which 50 , , and US Navy destroyers were transferred to the Royal Navy from the US Navy in exchange for land rights ...

). There were 60 submarines and seven aircraft carriers with more of both under construction."British and Commonwealth Navies at the Beginning and End of World War 2"naval-history.net At the end the RN had 16 battleships, 52 carriers—though most of these were small escort or merchant carriers—62 cruisers, 257 destroyers, 131 submarines and 9,000 other ships. During the war the Royal Navy lost 278 major warships and more than 1,000 small ones. There were 200,000 men (including reserves and marines) in the navy at the start of the war, which rose to 939,000 by the end. 51,000 RN sailors were killed and a further 30,000 from the merchant services. The WRNS was reactivated in 1938 and their numbers rose to a peak of 74,000 in 1944. The Royal Marines reached a maximum of 78,000 in 1945, having taken part in all the major landings.

Norway campaign, 1940

Finland's defensive war against the Soviet invasion, lasting November 1939 to March 1940, came at a time when there was a lack of large scale military action on the continent called the "Phony War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

". Attention turned to the Nordic theater. After months of planning at the highest civilian, military and diplomatic levels in London and Paris, in spring, 1940, a series of decisions were made that would involve uninvited invasions of Norway, Sweden, Iceland, and Denmark's Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

, with the goals of damaging the German war economy and assisting Finland in its war with the Soviet Union. An allied war against the Soviet Union was part of the plan. The main naval launching point would be Royal Navy's base at Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

in the Orkney Islands. The Soviet invasion of Finland excited widespread outrage at popular and elite levels in support of Finland not only in wartime Britain and France but also in neutral United States. The League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

declared the USSR was the aggressor and expelled it. "American opinion makers treated the attack on Finland as dastardly aggression worthy of daily headlines, which thereafter exacerbated attitudes toward Russia." The real Allied goal was economic warfare: cutting off shipments of Swedish iron ore to Germany, which they calculated would seriously weaken German war industry. The British Ministry of Economic Warfare

The Minister of Economic Warfare was a British government position which existed during the Second World War. The minister was in charge of the Special Operations Executive and the Ministry of Economic Warfare.

See also

* Blockade of Germany (193 ...

stated that the project against Norway would be likely to cause "An extremely serious repercussion on German industrial output... nd the Swedish componentmight well bring German industry to a standstill and would in any case have a profound effect on the duration of the war." The idea was to shift forces away from doing little on the static Western Front into an active role on a new front. The British military leadership by December became enthusiastic supporters when they realized that their first choice, an attack on German oil supplies, would not get approval. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, now head of the Admiralty, pushed hard for an invasion of Norway and Sweden to help the Finns and cut the iron supplies. Likewise the political and military leaders in Paris strongly supported the plan, because it would put their troops in action. The poor performance of the Soviet army against the Finns strengthened the confidence of the Allies that the invasion, and the resulting war with Russia, would be worthwhile. However the civilian leadership of Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

's government in London drew back and postponed invasion plans. Neutral Norway and Sweden refused to cooperate. Finland hoped for Allied intervention but its position became increasingly hopeless; its agreement to an armistice on March 13 signalled defeat. On March 20, a more aggressive Paul Reynaud

Paul Reynaud (; 15 October 1878 – 21 September 1966) was a French politician and lawyer prominent in the interwar period, noted for his stances on economic liberalism and militant opposition to Germany.

Reynaud opposed the Munich Agreement of ...

became Prime Minister of France and demanded an immediate invasion; Chamberlain and the British cabinet finally agreed and orders were given. However Germany invaded first, quickly conquering Denmark and southern Norway in Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung (german: Unternehmen Weserübung , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was Germany's assault on Denmark and Norway during the Second World War and the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 Ap ...

. The Germans successfully repelled the Allied invasion. With the British failure in Norway, London decided it immediately needed to set up naval and air bases in Iceland. Despite Iceland's plea for neutrality, its occupation was seen as a military necessity by London. The Faroe Islands were occupied on April 13, and the decision made to occupy Iceland on May 6.

German invasion threat 1940

Operation Sea Lion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (german: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Battle o ...

was Germany's threatened invasion across the English channel in 1940. The Germans had the soldiers and the small boats in place, and had far more in the way of tanks and artillery than the British had after their retreat from Dunkirk. However, the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force were fully prepared, and historians believe that an attempted invasion would be a disaster for the Germans. British naval power, based in Scotland, was very well-equipped with heavily armored battleships; Germany had none available. At no point did Germany have the necessary air superiority. And even if they had achieved air superiority, it would have been meaningless on bad weather days, which would ground warplanes but not hinder the Royal Navy from demolishing the transports and blasting the landing fields. The German general Alfred Jodl

Alfred Josef Ferdinand Jodl (; 10 May 1890 – 16 October 1946) was a German ''Generaloberst'' who served as the chief of the Operations Staff of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' – the German Armed Forces High Command – throughout World ...

realized that as long as the British navy was a factor, an invasion would be to send "my troops into a mincing machine."

Collaboration

With a wide range of nations collaborating with the Allies, the British needed a way to coordinate the work. The Royal Navy dealt smoothly with the navies-in-exile of Poland, Norway, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Yugoslavia, and Greece using a liaison system between senior naval officers. The system produced the effective integration of Allied navies into Royal Navy commands.France

When France fell in June 1940, Germany made French soldiers into POWs but allowed Vichy France to keep its powerful fleet, the fourth largest in the world. France sent its warships to its colonial ports or to ports controlled by Britain. The British fought one of the main squadrons in theattack on Mers-el-Kébir

The Attack on Mers-el-Kébir (Battle of Mers-el-Kébir) on 3 July 1940, during the Second World War, was a British naval attack on neutral French Navy ships at the naval base at Mers El Kébir, near Oran, on the coast of French Algeria. The atta ...

, Algeria (near Oran), on 3 July 1940. The attack killed 1300 men and sank or badly damaged three of the four battleships at anchor. The Vichy government was angry indeed but did not retaliate and maintained a state of armed neutrality in the war. The British seized warships in British harbors, and they eventually became part of the Free French Naval Forces

The Free French Naval Forces (french: Forces Navales Françaises Libres, or FNFL) were the naval arm of the Free French Forces during the Second World War. They were commanded by Admiral Émile Muselier.

History

In the wake of the Armistice a ...

. When Germany occupied all of France in November 1942, Vichy France had assembled at Toulon about a third of the warships it had started with, amounting to 200,000 tons. Germany tried to seize them; the French officers then scuttled their own fleet.

Italy

The Italian navy ("Regia Marina") had the mission of keeping open the trans Mediterranean to North Africa and the Balkans; it was challenged by the British Royal Navy. It was well behind the British in the latest technology, such as radar, which was essential for night gunnery at long range. ''Regia Marina'' Strength 6 battleships, 19 cruisers, 59 destroyers, 67 torpedo boats, 116 submarines. Two aircraft carriers were under construction; they were never launched. The nation was too poor to launch a major shipbuilding campaign, which made the senior commanders cautious for fear of losing assets that could not be replaced. In theBattle of the Mediterranean

The Battle of the Mediterranean was the name given to the naval campaign fought in the Mediterranean Sea during World War II, from 10 June 1940 to 2 May 1945.

For the most part, the campaign was fought between the Italian Royal Navy (''Regia ...

the British had broken the Italian naval code and knew the times of departure, routing, time of arrival and make up of convoys. The Italians neglected to capture Malta, which became the main staging and logistical base for the British.

Japan

Strength

On 7 December 1941, the principal units of the Japanese Navy included: *10 battleships (11 by the end of the year) *6 fleet carriers *4 light fleet carriers *18 heavy cruisers *18 light cruisers *113 destroyers *63 submarines The front-line strength of theNaval Air Forces

Commander, Naval Air Forces ( COMNAVAIRFOR, and CNAF; and dual-hatted as Commander, Naval Air Force, Pacific, and COMNAVAIRPAC) is the aviation Type Commander (TYCOM) for all United States Navy naval aviation units. Type Commanders are in Admini ...

was 1753 warplanes, including 660 fighters, 330 torpedo bombers, and 240 shore-based bombers. There were also 520 flying boats used for reconnaissance.

1942 IJN Operation

In the six months following Pearl Harbor, Admiral Yamamoto's carrier-based fleet engaged in multiple operations ranging from raids on Ceylon in the Indian Ocean to an attempted conquest of Midway Island, west of Hawaii. His actions were largely successful in defeating American, British and Dutch naval forces, although The American fleet held at the battle of Coral Sea, and inflicted a decisive defeat on Yamamoto at Midway.Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

fell in mid-December, and the Philippines were invaded at several points. Wake Island fell on December 23. January, 1942 saw the IJN handle invasions of the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

, Western New Guinea

Western New Guinea, also known as Papua, Indonesian New Guinea, or Indonesian Papua, is the western half of the Melanesian island of New Guinea which is administered by Indonesia. Since the island is alternatively named as Papua, the region ...

, and the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

. IJN built major forward bases at Truk and Rabaul

Rabaul () is a township in the East New Britain province of Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. It lies about 600 kilometres to the east of the island of New Guinea. Rabaul was the provincial capital and most important settlement in ...

. The Japanese army captured Manila, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore. Bali

Bali () is a province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller neighbouring islands, notably Nusa Penida, Nusa Lembongan, and Nu ...

and Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is East Timor–Indonesia border, divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western p ...

also fell in February. The rapid collapse of Allied resistance had left the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command

The American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command, or ABDACOM, was a short-lived, supreme command for all Allies of World War II, Allied forces in South East Asia in early 1942, during the Pacific War in World War II. The command consists of ...

split in two. At the Battle of the Java Sea

The Battle of the Java Sea ( id, Pertempuran Laut Jawa, ja, スラバヤ沖海戦, Surabaya oki kaisen, Surabaya open-sea battle, Javanese : ꦥꦼꦫꦁꦱꦼꦒꦫꦗꦮ, romanized: ''Perang Segara Jawa'') was a decisive naval battle o ...

, in late February and early March, the IJN inflicted a resounding defeat on the main ABDA naval force, under the Dutch. The Netherlands East Indies campaign subsequently ended with the surrender of Allied forces on Java.

Netherlands

The small but modern Dutch fleet had as its primary mission the defence of the oil-rich

The small but modern Dutch fleet had as its primary mission the defence of the oil-rich Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

.Herman Theodore Bussemaker, "Paradise in Peril: The Netherlands, Great Britain and the Defence of the Netherlands East Indies, 1940–41," ''Journal of Southeast Asian Studies'' (2000) 31#1 pp: 115-136. The Netherlands, Britain and the United States tried to defend the colony from the Japanese as it moved south in late 1941 in search of Dutch oil. The Dutch had five cruisers, eight destroyers, 24 submarines, and smaller vessels, along with 50 obsolete aircraft. Most of the forces were lost to Japanese air or sea attacks, with the survivors merged into the British Eastern Fleet. The Dutch navy had suffered from years of underfunding and came ill-prepared to face an enemy with far more and far heavier ships with better weapons, including the Long Lance

The was a -diameter torpedo of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), launched from surface ships. It is commonly referred to as the Long Lance by most modern English-language naval historians, a nickname given to it after the war by Samuel Eliot Mori ...

-torpedo, with which the cruiser '' Haguro'' sank the light cruiser .

As Germany invaded in April 1940, the government moved into exile in Britain and a few ships along with the headquarters of the Royal Netherlands Navy

The Royal Netherlands Navy ( nl, Koninklijke Marine, links=no) is the naval force of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

During the 17th century, the navy of the Dutch Republic (1581–1795) was one of the most powerful naval forces in the world an ...

continued the fight. It maintained units in the Dutch East Indies and, after it was conquered, in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

. It was decisively defeated defending the Dutch East Indies in the Battle of the Java Sea

The Battle of the Java Sea ( id, Pertempuran Laut Jawa, ja, スラバヤ沖海戦, Surabaya oki kaisen, Surabaya open-sea battle, Javanese : ꦥꦼꦫꦁꦱꦼꦒꦫꦗꦮ, romanized: ''Perang Segara Jawa'') was a decisive naval battle o ...

. The battle consisted of a series of attempts over a seven-hour period by Admiral Karel Doorman

Karel Willem Frederik Marie Doorman (23 April 1889 – 28 February 1942) was a Dutch naval officer who during World War II commanded remnants of the short-lived American-British-Dutch-Australian Command naval strike forces in the Battle ...

's Combined Striking Force to attack the Japanese invasion convoy; each was rebuffed by the escort force. Doorman went down with his ships together with 1000 of his crew. During the relentless Japanese offensive of February through April 1942 in the Dutch East Indies, the Dutch navy in the Far East was virtually annihilated, and it sustained losses of a total of 20 ships (including its only two light cruisers) and 2500 sailors killed.

A small force of Dutch submarines based in Western Australia sank more Japanese ships in the first weeks of the war than the entire British and American navies together, an exploit which earned Admiral Helfrich the nickname "Ship-a-day Helfrich".

Around the world Dutch naval units were responsible for transporting troops; for example, during Operation Dynamo

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

in Dunkirk and on D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as D ...

, they escorted convoys and attacked enemy targets.

USSR

Building a Soviet fleet was a national priority, but many senior officers were killed in purges in the late 1930s. The naval share of the national munitions budget fell from 11.5% in 1941 to 6.6% in 1944. When Germany invaded in 1941 and captured millions of soldiers, many sailors and naval guns were detached to reinforce theRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

; these reassigned naval forces participated with every major action on the Eastern Front. Soviet naval personnel had especially significant roles on land in the battles for Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, Stalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stal ...

, Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk ( rus, Новоросси́йск, p=nəvərɐˈsʲijsk; ady, ЦIэмэз, translit=Chəməz, p=t͡sʼɜmɜz) is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is one of the largest ports on the Black Sea. It is one of the few cities hono ...

, Tuapse

Tuapse (russian: Туапсе́; ady, Тӏуапсэ ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town in Krasnodar Krai, Russia, situated on the northeast shore of the Black Sea, south of Gelendzhik and north of Sochi. Population:

Tuapse i ...

(see Battle of the Caucasus

The Battle of the Caucasus is a name given to a series of Axis and Soviet operations in the Caucasus area on the Eastern Front of World War II. On 25 July 1942, German troops captured Rostov-on-Don, Russia, opening the Caucasus region of t ...

), and Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. The Baltic fleet was blockaded in Leningrad and Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for "crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city of ...

by minefields, but the submarines escaped. The surface fleet fought with the anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

defence of the city and bombarded German positions. In the Black Sea, many ships were damaged by minefields and Axis aviation, but they helped defend naval bases and supply them while besieged, as well as later evacuating them.

The U.S. and Britain through Lend Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

gave the USSR ships with a total displacement of 810,000 tons.

Although Soviet leaders were reluctant to risk larger vessels after the heavy losses suffered by the Soviet Navy in 1941-2, the Soviet destroyer force was used throughout the war in escort, fire-support and transport roles. Soviet warships, and especially the destroyers, saw action throughout the war in Arctic waters and in the Black Sea. In Arctic waters Soviet destroyers participated in the defense of Allied convoys.

Romania

The

The Romanian Navy