Navajo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a

The Navajos are speakers of a Na-Dené

The Navajos are speakers of a Na-Dené

The United States military continued to maintain forts on the Navajo reservation in the years after the Long Walk. From 1873 to 1895, the military employed Navajos as "Indian Scouts" at Fort Wingate to help their regular units. During this period, Chief

The United States military continued to maintain forts on the Navajo reservation in the years after the Long Walk. From 1873 to 1895, the military employed Navajos as "Indian Scouts" at Fort Wingate to help their regular units. During this period, Chief

The name "Navajo" comes from the late 18th century via the Spanish ''(Apaches de) Navajó'' "(Apaches of) Navajó", which was derived from the

The name "Navajo" comes from the late 18th century via the Spanish ''(Apaches de) Navajó'' "(Apaches of) Navajó", which was derived from the

A

A

Magic in North America Part 1: Ugh.

at '' Native Appropriations", 8 March 2016. Accessed 9 April 2016: "What happens when Rowling pulls this in, is we as Native people are now opened up to a barrage of questions about these beliefs and traditions ... but these are not things that need or should be discussed by outsiders. At all. I'm sorry if that seems "unfair," but that's how our cultures survive."

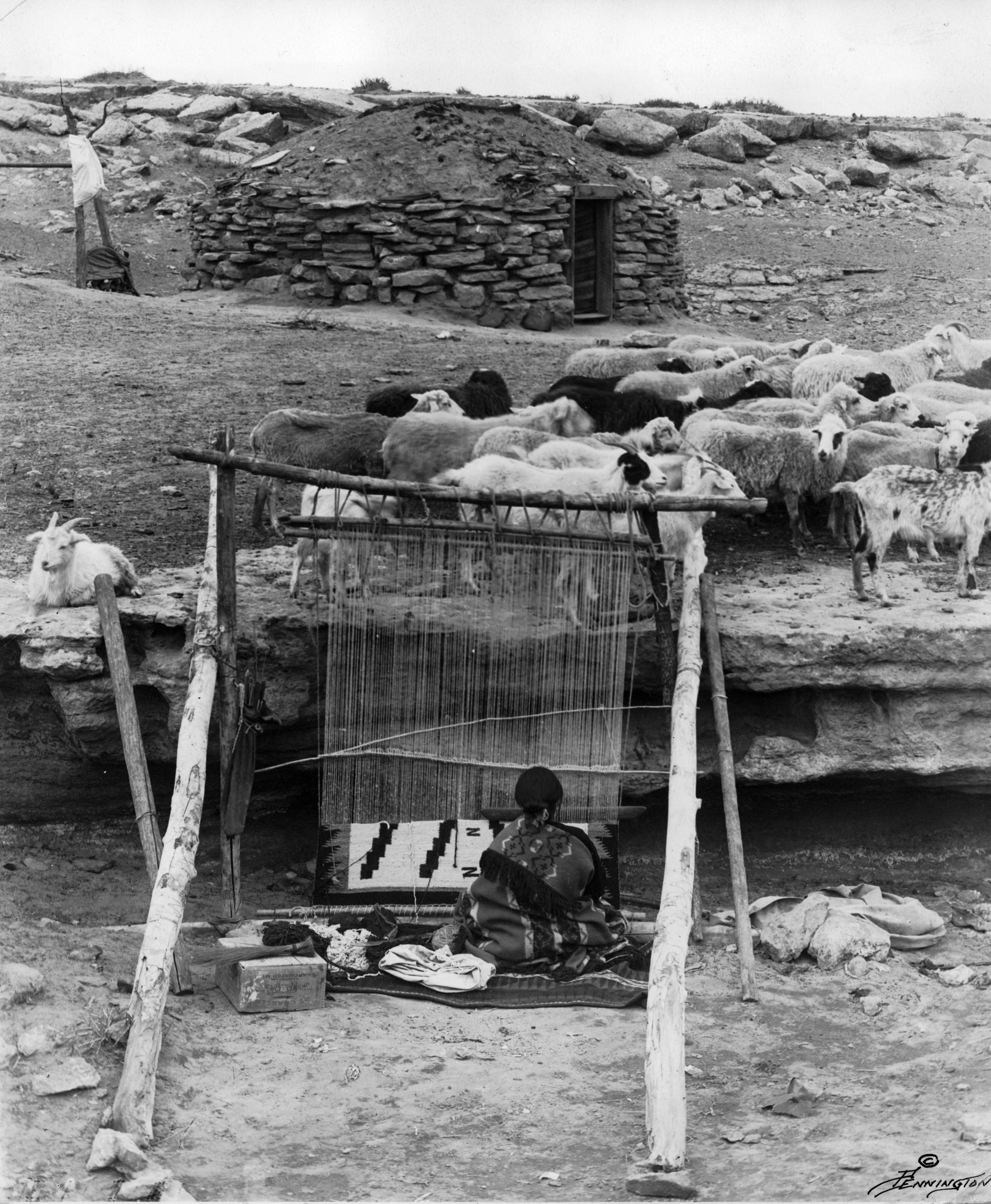

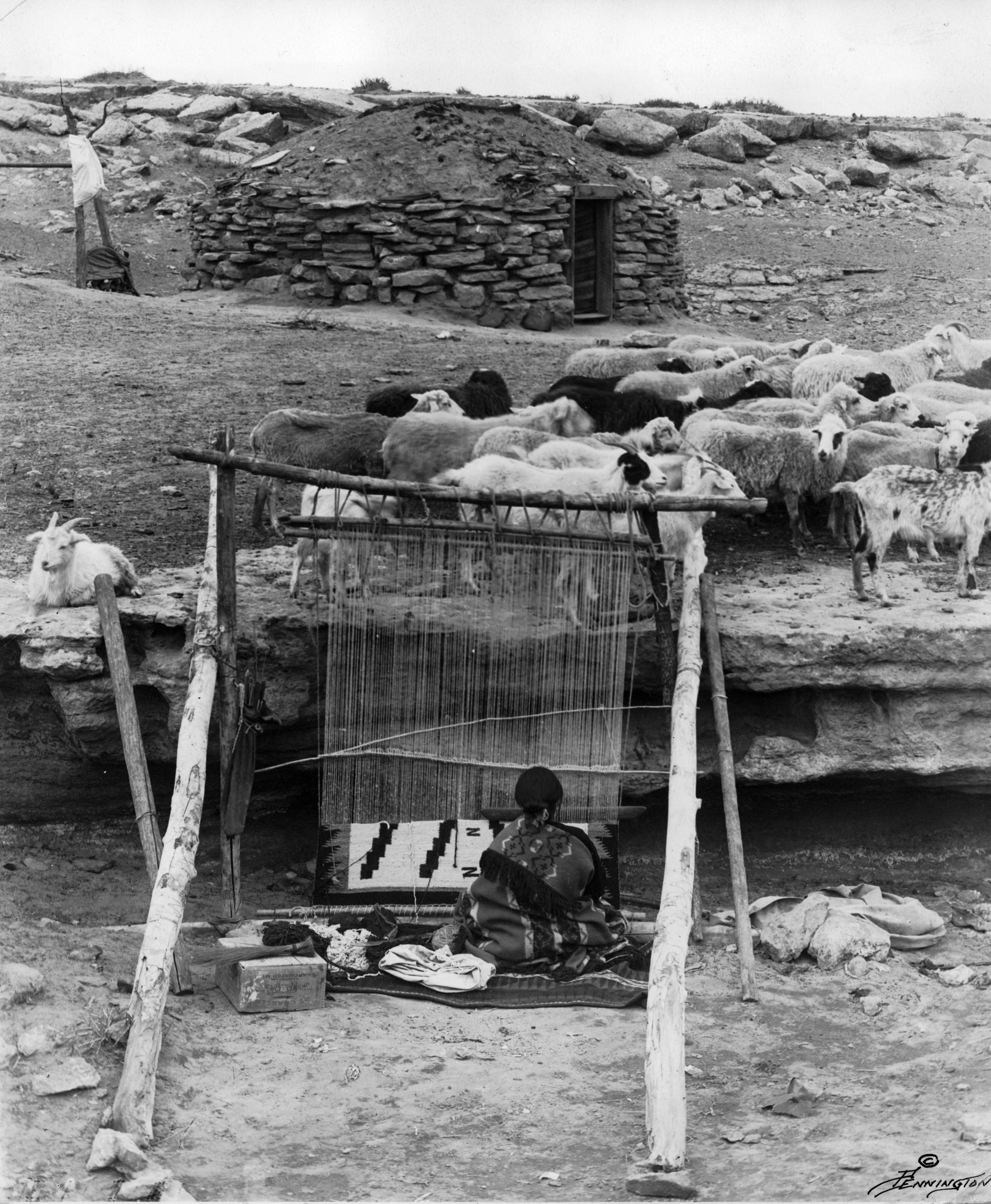

Navajos came to the southwest with their own weaving traditions; however, they learned to weave cotton on upright looms from Pueblo peoples. The first Spaniards to visit the region wrote about seeing Navajo blankets. By the 18th century, the Navajos had begun to import Bayeta red yarn to supplement local black, grey, and white wool, as well as wool dyed with

Navajos came to the southwest with their own weaving traditions; however, they learned to weave cotton on upright looms from Pueblo peoples. The first Spaniards to visit the region wrote about seeing Navajo blankets. By the 18th century, the Navajos had begun to import Bayeta red yarn to supplement local black, grey, and white wool, as well as wool dyed with

* Fred Begay,

* Fred Begay,

Native American people

Native Americans, also known as American Indians, First Americans, Indigenous Americans, and other terms, are the Indigenous peoples of the mainland United States (Indigenous peoples of Hawaii, Alaska and territories of the United States are ...

of the Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States that generally includes Arizona, New Mexico, and adjacent portions of California, Colorado, N ...

.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation

The Navajo Nation ( nv, Naabeehó Bináhásdzo), also known as Navajoland, is a Native Americans in the United States, Native American Indian reservation, reservation in the United States. It occupies portions of northeastern Arizona, northwe ...

is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United States; additionally, the Navajo Nation has the largest reservation __NOTOC__

Reservation may refer to: Places

Types of places:

* Indian reservation, in the United States

* Military base, often called reservations

* Nature reserve

Government and law

* Reservation (law), a caveat to a treaty

* Reservation in India, ...

in the country. The reservation straddles the Four Corners

The Four Corners is a region of the Southwestern United States consisting of the southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and northwestern corner of New Mexico. The Four Corners area ...

region and covers more than 27,325 square miles (70,000 square km) of land in Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States. It is the list of U.S. states and territories by area, 6th largest and the list of U.S. states and territories by population, 14 ...

, Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

, and New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

. The Navajo Reservation is slightly larger than the state of West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

. The Navajo language

Navajo or Navaho (; Navajo: or ) is a Southern Athabaskan languages, Southern Athabaskan language of the Na-Dene languages, Na-Dené family, through which it is related to languages spoken across the western areas of North America. Navajo is s ...

is spoken throughout the region, and most Navajos also speak English.

The states with the largest Navajo populations are Arizona (140,263) and New Mexico (108,306). More than three-fourths of the enrolled Navajo population resides in these two states.American FactfinderUnited States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy

An economy is an area of th ...

Besides the Navajo Nation

The Navajo Nation ( nv, Naabeehó Bináhásdzo), also known as Navajoland, is a Native Americans in the United States, Native American Indian reservation, reservation in the United States. It occupies portions of northeastern Arizona, northwe ...

proper, a small group of Navajos are members of the federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the Unite ...

Colorado River Indian Tribes.

History

Early history

The Navajos are speakers of a Na-Dené

The Navajos are speakers of a Na-Dené Southern Athabaskan language

Southern Athabaskan (also Apachean) is a subfamily of Athabaskan languages spoken primarily in the Southwestern United States (including Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah) with two outliers in Oklahoma and Texas. The language is spoken to ...

which they call ''Diné bizaad'' (lit. 'People's language'). The term ''Navajo'' comes from Spanish missionaries and historians who referred to the Pueblo Indians through this term, although they referred to themselves as the ''Diné,'' is a compound word meaning up where there is no surface, and then down to where we are on the surface of Mother Earth. The language comprises two geographic, mutually intelligible dialects. The Apache language is closely related to the Navajo Language; the Navajos and Apaches are believed to have migrated from northwestern Canada and eastern Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S ...

, where the majority of Athabaskan speakers reside. Speakers of various other Athabaskan languages located in Canada may still comprehend the Navajo language despite the geographic and linguistic deviation of the languages. Additionally, some Navajos speak Navajo Sign Language, which is either a dialect or daughter of Plains Sign Talk. Some also speak Plains Sign Talk itself.Samuel J. Supalla (1992) ''The Book of Name Signs'', p. 22

Archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape ...

and historical evidence suggests the Athabaskan ancestors of the Navajos and Apaches entered the Southwest around 1400 AD. The Navajo oral tradition is transcribed to retain references to this migration.

Initially, the Navajos were largely hunters and gatherers. Later, they adopted farming from Pueblo

In the Southwestern United States, Pueblo (capitalized) refers to the Native tribes of Puebloans having fixed-location communities with permanent buildings which also are called pueblos (lowercased). The Spanish explorers of northern New Spain ...

peoples, growing mainly the traditional " Three Sisters" of corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn ( North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. ...

, bean

A bean is the seed of several plants in the family Fabaceae, which are used as vegetables for human or animal food. They can be cooked in many different ways, including boiling, frying, and baking, and are used in many traditional dishes t ...

s, and squash. They adopted herding sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated sh ...

and goats

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a domesticated species of goat-antelope typically kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the a ...

from the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

** Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Ca ...

as a main source of trade and food. Meat became essential in the Navajo diet. Sheep became a form of currency and family status. Women began to spin and weave wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

...

into blanket

A blanket is a swath of soft cloth large enough either to cover or to enfold most of the user's body and thick enough to keep the body warm by trapping radiant body heat that otherwise would be lost through convection.

Etymology

The ter ...

s and clothing; they created items of highly valued artistic expression, which were also traded and sold.

Oral history indicates a long relationship with Pueblo people and a willingness to incorporate Puebloan ideas and linguistic variance. There were long-established trading practices between the groups. Mid-16th century Spanish records recount that the Pueblo exchanged maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn ( North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. ...

and woven cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor p ...

goods for bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North ...

meat, hides, and stone from Athabaskans traveling to the pueblos or living nearby. In the 18th century, the Spanish reported that the Navajos' maintained large herds of livestock and cultivated large crop areas.

Western historians believe that the Spanish before 1600 referred to the Navajos as ''Apaches'' or ''Quechos''. Fray Geronimo de Zarate-Salmeron, who was in Jemez in 1622, used ''Apachu de Nabajo'' in the 1620s to refer to the people in the Chama Valley region, east of the San Juan River and northwest of present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico

Santa Fe ( ; , Spanish for 'Holy Faith'; tew, Oghá P'o'oge, Tewa for 'white shell water place'; tiw, Hulp'ó'ona, label= Northern Tiwa; nv, Yootó, Navajo for 'bead + water place') is the capital of the U.S. state of New Mexico. The name “S ...

. ''Navahu'' comes from the Tewa

The Tewa are a linguistic group of Pueblo Native Americans who speak the Tewa language and share the Pueblo culture. Their homelands are on or near the Rio Grande in New Mexico north of Santa Fe. They comprise the following communities:

* ...

language, meaning a large area of cultivated lands. By the 1640s, the Spanish began using the term ''Navajo'' to refer to the Diné.

During the 1670s, the Spanish wrote that the Diné lived in a region known as ', about west of the Rio Chama valley region. In the 1770s, the Spanish sent military expeditions against the Navajos in the Mount Taylor and Chuska Mountain regions of New Mexico. The Spanish, Navajos and Hopis continued to trade with each other and formed a loose alliance to fight Apache and Comanche bands for the next 20 years. During this time there were relatively minor raids by Navajo bands and Spanish citizens against each other.

In 1800 Governor Chacon led 500 men to the Tunicha Mountains against the Navajo. Twenty Navajo chiefs asked for peace. In 1804 and 1805 the Navajos and Spanish mounted major expeditions against each other's settlements. In May 1805 another peace was established. Similar patterns of peace-making, raiding, and trading among the Navajo, Spanish, Apache, Comanche, and Hopi continued until the arrival of Americans in 1846.

Territory of New Mexico 1846–1863

The Navajos encountered theUnited States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

in 1846, when General Stephen W. Kearny invaded Santa Fe with 1,600 men during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

. On November 21, 1846, following an invitation from a small party of American soldiers under the command of Captain John Reid, who journeyed deep into Navajo country and contacted him, Narbona and other Navajos negotiated a treaty of peace with Colonel Alexander Doniphan at Bear Springs, Ojo del Oso (later the site of Fort Wingate

Fort Wingate was a military installation near Gallup, New Mexico. There were two other locations in New Mexico called Fort Wingate: Seboyeta, New Mexico (1849–1862) and San Rafael, New Mexico (1862–1868). The most recent Fort Wingate (1868 ...

). This agreement was not honored by some Navajo, nor by some New Mexicans. The Navajos raided New Mexican livestock, New Mexicans took women, children, and livestock from the Navajo.

In 1849, the military governor of New Mexico, Colonel John MacRae Washington—accompanied by John S. Calhoun, an Indian agent—led 400 soldiers into Navajo country, penetrating Canyon de Chelly. He signed a treaty with two Navajo leaders: Mariano Martinez as Head Chief and Chapitone as Second Chief. The treaty acknowledged the transfer of jurisdiction from the United Mexican States to the United States. The treaty allowed forts and trading posts to be built on Navajo land. In exchange, the United States, promised "such donations ndsuch other liberal and humane measures, as tmay deem meet and proper." While en route to sign this treaty, the prominent Navajo peace leader Narbona, was killed, causing hostility between the treaty parties.

During the next 10 years, the U.S. established forts on traditional Navajo territory. Military records cite this development as a precautionary measure to protect citizens and the Navajos from each other. However, the Spanish/Mexican-Navajo pattern of raids and expeditions continued. Over 400 New Mexican militia conducted a campaign against the Navajo, against the wishes of the Territorial Governor, in 1860–61. They killed Navajo warriors, captured women and children for slaves, and destroyed crops and dwellings. The Navajos call this period ''Naahondzood'', "the fearing time."

In 1861, Brigadier-General James H. Carleton, Commander of the Federal District of New Mexico, initiated a series of military actions against the Navajos and Apaches. Colonel Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and ...

was at the new Fort Wingate

Fort Wingate was a military installation near Gallup, New Mexico. There were two other locations in New Mexico called Fort Wingate: Seboyeta, New Mexico (1849–1862) and San Rafael, New Mexico (1862–1868). The most recent Fort Wingate (1868 ...

with Army troops and volunteer New Mexico militia. Carleton ordered Carson to kill Mescalero

Mescalero or Mescalero Apache ( apm, Naa'dahéńdé) is an Apache tribe of Southern Athabaskan–speaking Native Americans. The tribe is federally recognized as the Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Apache Reservation, located in south- ...

Apache men and destroy any Mescalero property he could find. Carleton believed these harsh tactics would bring any Indian Tribe under control. The Mescalero surrendered and were sent to the new reservation called Bosque Redondo.

In 1863, Carleton ordered Carson to use the same tactics on the Navajo. Carson and his force swept through Navajo land, killing Navajos and destroying crops and dwellings, fouling wells, and capturing livestock. Facing starvation and death, Navajo groups came in to Fort Defiance for relief. On July 20, 1863, the first of many groups departed to join the Mescalero at Bosque Redondo. Other groups continued to come in though 1864.

However, not all the Navajos came in or were found. Some lived near the San Juan River, some beyond the Hopi villages, and others lived with Apache bands.

Long Walk

Beginning in the spring of 1864, the Army forced around 9,000 Navajo men, women, and children to walk over to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, for internment at Bosque Redondo. The internment was disastrous for the Navajo, as the government failed to provide enough water, wood, provisions, and livestock for the 4,000–5,000 people. Large-scale crop failure and disease were also endemic during this time, as were raids by other tribes and civilians. Some Navajos froze in the winter because they could make only poor shelters from the few materials they were given. This period is known among the Navajos as "The Fearing Time". In addition, a small group of Mescalero Apache, longtime enemies of the Navajos had been relocated to the area, which resulted in conflicts. In 1868, the Treaty of Bosque Redondo was negotiated between Navajo leaders and the federal government allowing the surviving Navajos to return to areservation __NOTOC__

Reservation may refer to: Places

Types of places:

* Indian reservation, in the United States

* Military base, often called reservations

* Nature reserve

Government and law

* Reservation (law), a caveat to a treaty

* Reservation in India, ...

on a portion of their former homeland.

Reservation era

The United States military continued to maintain forts on the Navajo reservation in the years after the Long Walk. From 1873 to 1895, the military employed Navajos as "Indian Scouts" at Fort Wingate to help their regular units. During this period, Chief

The United States military continued to maintain forts on the Navajo reservation in the years after the Long Walk. From 1873 to 1895, the military employed Navajos as "Indian Scouts" at Fort Wingate to help their regular units. During this period, Chief Manuelito

Chief Manuelito or Hastiin Chʼil Haajiní ("Sir Black Reeds", "Man of the Black Plants Place") (1818–1893) was one of the principal headmen of the Diné people before, during and after the Long Walk Period. ''Manuelito'' is the diminutive fo ...

founded the Navajo Tribal Police. It operated from 1872 to 1875 as an anti-raid task force working to maintain the peaceful terms of the 1868 Navajo treaty.

By treaty, the Navajos were allowed to leave the reservation for trade, with permission from the military or local Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of ...

. Eventually, the arrangement led to a gradual end in Navajo raids, as the tribe was able to increase their livestock and crops. Also, the tribe gained an increase in the size of the Navajo reservation from to the as it stands today. But economic conflicts with non-Navajos continued for many years as civilians and companies exploited resources assigned to the Navajo. The US government made leases for livestock grazing, took land for railroad development, and permitted mining on Navajo land without consulting the tribe.

In 1883, Lt. Parker, accompanied by 10 enlisted men and two scouts, went up the San Juan River to separate the Navajos and citizens who had encroached on Navajo land. In the same year, Lt. Lockett, with the aid of 42 enlisted soldiers, was joined by Lt. Holomon at Navajo Springs. Evidently, citizens of the surnames Houck and/or Owens had murdered a Navajo chief's son, and 100 armed Navajo warriors were looking for them.

In 1887, citizens Palmer, Lockhart, and King fabricated a charge of horse stealing and randomly attacked a dwelling on the reservation. Two Navajo men and all three whites died as a result, but a woman and a child survived. Capt. Kerr (with two Navajo scouts) examined the ground and then met with several hundred Navajos at Houcks Tank. Rancher Bennett, whose horse was allegedly stolen, told Kerr that his horses were stolen by the three whites to catch a horse thief. In the same year, Lt. Scott went to the San Juan River with two scouts and 21 enlisted men. The Navajos believed Scott was there to drive off the whites who had settled on the reservation and had fenced off the river from the Navajo. Scott found evidence of many non-Navajo ranches. Only three were active, and the owners wanted payment for their improvements before leaving. Scott ejected them.

In 1890, a local rancher refused to pay the Navajos a fine of livestock. The Navajos tried to collect it, and whites in southern Colorado and Utah claimed that 9,000 of the Navajos were on a warpath. A small military detachment out of Fort Wingate restored white citizens to order.

In 1913, an Indian agent ordered a Navajo and his three wives to come in, and then arrested them for having a plural marriage. A small group of Navajos used force to free the women and retreated to Beautiful Mountain with 30 or 40 sympathizers. They refused to surrender to the agent, and local law enforcement and military refused the agent's request for an armed engagement. General Scott arrived, and with the help of Henry Chee Dodge, a leader among the Navajo, defused the situation.

Boarding schools and education

During the time on the reservation, the Navajo tribe was forced to assimilate to white society. Navajo children were sent to boarding schools within the reservation and off the reservation. The first Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) school opened at Fort Defiance in 1870 and led the way for eight others to be established. Many older Navajos were against this education and would hide their children to keep them from being taken. Once the children arrived at the boarding school, their lives changed dramatically. European Americans taught the classes under an English-only curriculum and punished any student caught speaking Navajo. The children were under militaristic discipline, run by the ''Siláo''. In multiple interviews, subjects recalled being captured and disciplined by the ''Siláo'' if they tried to run away. Other conditions included inadequate food, overcrowding, required manual labor in kitchens, fields, and boiler rooms; and military-style uniforms and haircuts. Change did not occur in these boarding schools until after the Meriam Report was published in 1929 by the Secretary of Interior, Hubert Work. This report discussed Indian boarding schools as being inadequate in terms of diet, medical services, dormitory overcrowding, undereducated teachers, restrictive discipline, and manual labor by the students to keep the school running. This report was the precursor to education reforms initiated under PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, under which two new schools were built on the Navajo reservation. But Rough Rock Day School was run in the same militaristic style as Fort Defiance and did not implement the educational reforms. The Evangelical Missionary School was opened next to Rough Rock Day School. Navajo accounts of this school portray it as having a family-like atmosphere with home-cooked meals, new or gently used clothing, humane treatment, and a Navajo-based curriculum. Educators found the Evangelical Missionary School curriculum to be much more beneficial for the Navajo children.

In 1937, Boston heiress Mary Cabot Wheelright and Navajo singer and medicine man

A medicine man or medicine woman is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of Indigenous people of the Americas. Individual cultures have their own names, in their respective languages, for spiritual healers and cerem ...

Hastiin Klah founded the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian

The Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian is a museum devoted to Native American arts. It is located in Santa Fe, New Mexico and was founded in 1937 by Mary Cabot Wheelwright, who came from Boston, and Hastiin Klah, a Navajo singer and medic ...

in Santa Fe. It is a repository for sound recordings, manuscripts, paintings, and sandpainting tapestries of the Navajos. It also featured exhibits to express the beauty, dignity, and logic of Navajo religion. When Klah met Cabot in 1921, he had witnessed decades of efforts by the US government and missionaries to assimilate the Navajos into mainstream society. The museum was founded to preserve the religion and traditions of the Navajo, which Klah was sure would otherwise soon be lost forever.

The result of these boarding schools led to much language loss within the Navajo Nation. After the Second World War, the Meriam Report funded more children to attend these schools with six times as many children attending boarding school than before the War. English as the primary language spoken at these schools as well as the local towns surrounding the Navajo reservations contributed to residents becoming bilingual; however Navajo was the still the primary language spoken at home.

Livestock Reduction 1930s–1950s

TheNavajo Livestock Reduction

The Navajo Livestock Reduction was imposed by the United States government upon the Navajo Nation in the 1930s, during the Great Depression. The reduction of herds was justified at the time by stating that grazing areas were becoming eroded and ...

was imposed upon the Navajo Nation by the federal government starting in the 1933, during the Great Depression. Under various forms it continued into the 1950s. Worried about large herds in the arid climate, at a time when the Dust Bowl was endangering the Great Plains, the government decided that the land of the Navajo Nation could support only a fixed number of sheep, goats, cattle, and horses. The Federal government believed that land erosion was worsening in the area and the only solution was to reduce the number of livestock.

In 1933, John Collier John Collier may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*John Collier (caricaturist) (1708–1786), English caricaturist and satirical poet

*John Payne Collier (1789–1883), English Shakespearian critic and forger

*John Collier (painter) (1850–1934), ...

was appointed commissioner of the BIA. In many ways, he worked to reform government relations with the Native American tribes, but the reduction program was devastating for the Navajo, for whom their livestock was so important. The government set land capacity in terms of "sheep units". In 1930 the Navajos grazed 1,100,000 mature sheep units. These sheep provided half the cash income for the individual Navajo.

Collier's solution was to first launch a voluntary reduction program, which was made mandatory two years later in 1935. The government paid for part of the value of each animal, but it did nothing to compensate for the loss of future yearly income for so many Navajo. In the matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

and matrilocal world of the Navajo, women were especially hurt, as many lost their only source of income with the reduction of livestock herds.

The Navajos did not understand why their centuries-old practices of raising livestock should change. They were united in opposition but they were unable to stop it. Historian Brian Dippie notes that the Indian Rights Association

The Indian Rights Association (IRA) was a social activist group dedicated to the well being and acculturation of American Indians. Founded by non-Indians in Philadelphia in 1882, the group was highly influential in American Indian policy through ...

denounced Collier as a 'dictator' and accused him of a "near reign of terror" on the Navajo reservation. Dippie adds that, "He became an object of 'burning hatred' among the very people whose problems so preoccupied him." The long-term result was strong Navajo opposition to Collier's Indian New Deal.

Navajo Code Talkers in World War II

Many Navajo young people moved to cities to work in urban factories in World War II. Many Navajo men volunteered for military service in keeping with their warrior culture, and they served in integrated units. The War Department in 1940 rejected a proposal by the BIA that segregated units be created for the Indians. The Navajos gained firsthand experience with how they could assimilate into the modern world, and many did not return to the overcrowded reservation, which had few jobs. Four hundred Navajo code talkers played a famous role during World War II by relaying radio messages using their own language. The Japanese were unable to understand or decode it. In the 1940s, large quantities of uranium were discovered in Navajo land. From then into the early 21st century, the U.S. allowed mining without sufficient environmental protection for workers, waterways, and land. The Navajos have claimed high rates of death and illness from lung disease and cancer resulting from environmental contamination. Since the 1970s, legislation has helped to regulate the industry and reduce the toll, but the government has not yet offered holistic and comprehensive compensation.U.S. Marine Corps Involvement

The Navajo Code Talkers played a significant role inUSMC

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through co ...

history. Using their own language they utilized a military code; for example, the Navajo word "turtle" represented a tank. In 1942, Marine staff officers composed several combat simulations and the Navajo translated it and transmitted it in their dialect to another Navajo on the other line. This Navajo then translated it back in English faster than any other cryptographic facilities, which demonstrated their efficacy. As a result, General Vogel recommended their recruitment into the USMC code talker program.

Each Navajo went through basic bootcamp at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego before being assigned to Field Signal Battalion training at Camp Pendleton

Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton is the major West Coast base of the United States Marine Corps and is one of the largest Marine Corps bases in the United States. It is on the Southern California coast in San Diego County and is bordered by ...

. Once the code talkers completed training in the States, they were sent to the Pacific for assignment to the Marine combat divisions. With that said, there was never a crack in the Navajo language, it was never deciphered. It is known that many more Navajos volunteered to become code talkers than could be accepted; however, an undetermined number of other Navajos served as Marines in the war, but not as code talkers.

These achievements of the Navajo Code Talkers have resulted in an honorable chapter in USMC history. Their patriotism and honor inevitably earned them the respect of all Americans.

After 1945

Culture

The name "Navajo" comes from the late 18th century via the Spanish ''(Apaches de) Navajó'' "(Apaches of) Navajó", which was derived from the

The name "Navajo" comes from the late 18th century via the Spanish ''(Apaches de) Navajó'' "(Apaches of) Navajó", which was derived from the Tewa

The Tewa are a linguistic group of Pueblo Native Americans who speak the Tewa language and share the Pueblo culture. Their homelands are on or near the Rio Grande in New Mexico north of Santa Fe. They comprise the following communities:

* ...

''navahū'' "farm fields adjoining a valley". The Navajos call themselves '.

Like other Apacheans, the Navajos were semi-nomadic

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the pop ...

from the 16th through the 20th centuries. Their extended kinship groups had seasonal dwelling areas to accommodate livestock, agriculture, and gathering practices. As part of their traditional economy, Navajo groups may have formed trading or raiding parties, traveling relatively long distances.

There is a system of clans which defines relationships between individuals and families. The clan system is exogamous

Exogamy is the social norm of marrying outside one's social group. The group defines the scope and extent of exogamy, and the rules and enforcement mechanisms that ensure its continuity. One form of exogamy is dual exogamy, in which two groups ...

: people can only marry (and date) partners outside their own clans, which for this purpose include the clans of their four grandparents. Some Navajos favor their

children to marry into their father's clan. While clans are associated with a geographical area, the area is not for the exclusive use of any one clan. Members of a clan may live hundreds of miles apart but still have a clan bond.

Historically, the structure of the Navajo society is largely a matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

system, in which the family of the women owned livestock, dwellings, planting areas and livestock grazing areas. Once married, a Navajo man would follow a matrilocal residence and live with his bride in her dwelling and near her mother's family. Daughters (or, if necessary, other female relatives) were traditionally the ones who received the generational property inheritance. In cases of marital separation, women would maintain the property and children. Children are "born to" and belong to the mother's clan, and are "born for" the father's clan. The mother's eldest brother has a strong role in her children's lives. As adults, men represent their mother's clan in tribal politics.

Neither sex can live without the other in the Navajo culture. Men and women are seen as contemporary equals as both a male and female are needed to reproduce. Although women may carry a bigger burden, fertility is so highly valued that males are expected to provide economic resources (known as bride wealth

Bride price, bride-dowry ( Mahr in Islam), bride-wealth, or bride token, is money, property, or other form of wealth paid by a groom or his family to the woman or the family of the woman he will be married to or is just about to marry. Bride ...

). Corn is a symbol of fertility in Navajo culture as they eat white corn in the wedding ceremonies. It is considered to be immoral and/or stealing if one does not provide for the other in that premarital or marital relationship.

Ethnobotany

See Navajo ethnobotany.Traditional dwellings

A

A hogan

A hogan ( or ; from Navajo ' ) is the primary, traditional dwelling of the Navajo people. Other traditional structures include the summer shelter, the underground home, and the sweat house. A hogan can be round, cone-shaped, multi-sided, or squ ...

, the traditional Navajo home, is built as a shelter for either a man or for a woman. Male hogans are square or conical with a distinct rectangular entrance, while a female hogan is an eight-sided house. Hogans are made of logs and covered in mud, with the door always facing east to welcome the sun each morning. Navajos also have several types of hogans for lodging and ceremonial use. Ceremonies, such as healing ceremonies or the ''kinaaldá'', take place inside a hogan. According to Kehoe, this style of housing is distinctive to the Navajos. She writes, "even today, a solidly constructed, log-walled Hogan is preferred by many Navajo families." Most Navajo members today live in apartments and houses in urban areas.Kehoe, 133

Those who practice the Navajo religion regard the hogan as sacred. The religious song " The Blessingway" (') describes the first hogan as being built by Coyote with help from Beavers to be a house for First Man, First Woman, and Talking God. The Beaver People gave Coyote logs and instructions on how to build the first hogan. Navajos made their hogans in the traditional fashion until the 1900s, when they started to make them in hexagonal and octagonal shapes. Hogans continue to be used as dwellings, especially by older Navajos, although they tend to be made with modern construction materials and techniques. Some are maintained specifically for ceremonial purposes.

Spiritual and religious beliefs

Navajo spiritual practice is about restoring balance and harmony to a person's life to produce health and is based on the ideas of ''Hózhóójí''. The Diné believed in two classes of people: Earth People and Holy People. The Navajo people believe they passed through three worlds before arriving in this world, the Fourth World or the Glittering World. As Earth People, the Diné must do everything within their power to maintain the balance between Mother Earth and man. The Diné also had the expectation of keeping a positive relationship between them and the Diyin Diné. In the Diné Bahane' (Navajo beliefs about creation), the First, or Dark World is where the four Diyin Diné lived and where First Woman and First Man came into existence. Because the world was so dark, life could not thrive there and they had to move on. The Second, or Blue World, was inhabited by a few of the mammals Earth People know today as well as the Swallow Chief, or Táshchózhii. The First World beings had offended him and were asked to leave. From there, they headed south and arrived in the Third World, or Yellow World. The four sacred mountains were found here, but due to a great flood, First Woman, First Man, and the Holy People were forced to find another world to live in. This time, when they arrived, they stayed in the Fourth World. In the Glittering World, true death came into existence, as well as the creations of the seasons, the moon, stars, and the sun. The Holy People, or Diyin Diné, had instructed the Earth People to view the four sacred mountains as the boundaries of the homeland () they should never leave:Blanca Peak

Blanca Peak (Navajo: ) is the fourth highest summit of the Rocky Mountains of North America and the U.S. state of Colorado. The ultra-prominent peak is the highest summit of the Sierra Blanca Massif, the Sangre de Cristo Range, and the Sa ...

( — Dawn or White Shell Mountain) in Colorado; Mount Taylor ( — Blue Bead or Turquoise Mountain) in New Mexico; the San Francisco Peaks

The San Francisco Peaks (Navajo: , es, Sierra de San Francisco, Hopi: ''Nuva'tukya'ovi'', Western Apache: ''Dził Tso'', Keres: ''Tsii Bina'', Southern Paiute: ''Nuvaxatuh'', Havasupai-Hualapai: ''Hvehasahpatch''/''Huassapatch''/''Wik'hanbaja' ...

( — Abalone Shell Mountain) in Arizona; and Hesperus Mountain

Hesperus Mountain (Navajo: ) is the highest summit of the La Plata Mountains range of the Rocky Mountains of North America. The prominent thirteener is located in San Juan National Forest, northeast by east ( bearing 59°) of the Town of M ...

( — Big Mountain Sheep) in Colorado. Times of day, as well as colors, are used to represent the four sacred mountains. Throughout religions, the importance of a specific number is emphasized and in the Navajo religion, the number four appears to be sacred to their practices. For example, there were four original clans of Diné, four colors and times of day, four Diyin Diné, and for the most part, four songs sung for a ritual.

Navajos have many different ceremonies. For the most part, their ceremonies are to prevent or cure diseases. Corn pollen is used as a blessing and as an offering during prayer. One half of major Navajo song ceremonial complex

The Navajo song ceremonial complex is a spiritual practice used by certain Navajo ceremonial people to restore and maintain balance and harmony in the lives of the people. One half of the ceremonial complex is the Blessing Way, while the other hal ...

is the Blessing Way (''Hózhǫ́ǫ́jí)'' and other half is the Enemy Way (''Anaʼí Ndááʼ''). The Blessing Way ceremonies are based on establishing "peace, harmony, and good things exclusively" within the Dine. The Enemy Way, or Evil Way ceremonies are concerned with counteracting influences that come from outside the Dine. Spiritual healing ceremonies are rooted in Navajo traditional stories. One of them, the Night Chant ceremony, is conducted over several days and involves up to 24 dancers. The ceremony requires the dancers to wear buckskin masks, as do many of the other Navajo ceremonies, and they all represent specific gods. The purpose of the Night Chant is to purify the patients and heal them through prayers to the spirit-beings. Each day of the ceremony entails the performance of certain rites and the creation of detailed sand paintings. One of the songs describes the home of the thunderbirds:

The ceremonial leader proceeds by asking the Holy People to be present at the beginning of the ceremony, then identifying the patient with the power of the spirit-being, and describing the patient's transformation to renewed health with lines such as, "Happily I recover." Ceremonies are used to correct curses that cause some illnesses or misfortunes. People may complain ofIn Tsegihi hite House In the house made of the dawn, In the house made of the evening light

witches

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of Magic (supernatural), magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In Middle Ages, medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually ...

who do harm to the minds, bodies, and families of innocent people, though these matters are rarely discussed in detail with those outside of the community.Keene, Dr. Adrienne,Magic in North America Part 1: Ugh.

at '' Native Appropriations", 8 March 2016. Accessed 9 April 2016: "What happens when Rowling pulls this in, is we as Native people are now opened up to a barrage of questions about these beliefs and traditions ... but these are not things that need or should be discussed by outsiders. At all. I'm sorry if that seems "unfair," but that's how our cultures survive."

Oral stories/Works of literature

''See: Diné Bahane' (Creation Story) and Black God andCoyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans'') is a species of canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the wolf, and slightly smaller than the closely related eastern wolf and red wolf. It fills much of the same ecological ni ...

(notable traditional characters)''

The Navajo Tribe relied on oral tradition to maintain beliefs and stories. Examples would include the traditional creation story '' Diné Bahane'Music

Visual arts

Silverwork

Silversmith

A silversmith is a metalworker who crafts objects from silver. The terms ''silversmith'' and ''goldsmith'' are not exactly synonyms as the techniques, training, history, and guilds are or were largely the same but the end product may vary gre ...

ing is an important art form among Navajos. Atsidi Sani (c. 1830–c. 1918) is considered to be the first Navajo silversmith. He learned silversmithing from a Mexican man called ''Nakai Tsosi'' ("Thin Mexican") around 1878 and began teaching other Navajos how to work with silver. By 1880, Navajo silversmiths were creating handmade jewelry including bracelets, tobacco flasks, necklace

A necklace is an article of jewellery that is worn around the neck. Necklaces may have been one of the earliest types of adornment worn by humans. They often serve ceremonial, religious, magical, or funerary purposes and are also used as symb ...

s and bracer

A bracer (or arm-guard) is a strap or sheath, commonly made of leather, stone or plastic, that covers the ventral (inside) surface of an archer's bow-holding arm. It protects the archer's forearm against injury by accidental whipping from t ...

s. Later, they added silver earrings, buckles, bolos

Volos ( el, Βόλος ) is a coastal port city in Thessaly situated midway on the Greece, Greek mainland, about north of Athens and south of Thessaloniki. It is the sixth most populous city of Greece, and the capital of the Magnesia (region ...

, hair ornaments, pins and squash blossom necklaces for tribal use, and to sell to tourists as a way to supplement their income.

The Navajos' hallmark jewelry piece called the "squash blossom" necklace first appeared in the 1880s. The term "squash blossom" was apparently attached to the name of the Navajo necklace at an early date, although its bud-shaped beads are thought to derive from Spanish-Mexican pomegranate

The pomegranate (''Punica granatum'') is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae, subfamily Punicoideae, that grows between tall.

The pomegranate was originally described throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean re ...

designs. The Navajo silversmiths also borrowed the "naja" (''najahe'' in Navajo) symbol to shape the silver pendant that hangs from the "squash blossom" necklace.

Turquoise

Turquoise is an opaque, blue-to-green mineral that is a hydrated phosphate of copper and aluminium, with the chemical formula . It is rare and valuable in finer grades and has been prized as a gemstone and ornamental stone for thousands of y ...

has been part of jewelry for centuries, but Navajo artists did not use inlay techniques to insert turquoise into silver designs until the late 19th century.

Weaving

Navajos came to the southwest with their own weaving traditions; however, they learned to weave cotton on upright looms from Pueblo peoples. The first Spaniards to visit the region wrote about seeing Navajo blankets. By the 18th century, the Navajos had begun to import Bayeta red yarn to supplement local black, grey, and white wool, as well as wool dyed with

Navajos came to the southwest with their own weaving traditions; however, they learned to weave cotton on upright looms from Pueblo peoples. The first Spaniards to visit the region wrote about seeing Navajo blankets. By the 18th century, the Navajos had begun to import Bayeta red yarn to supplement local black, grey, and white wool, as well as wool dyed with indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', ...

. Using an upright loom, the Navajos made extremely fine utilitarian blankets that were collected by Ute

Ute or UTE may refer to:

* Ute (band), an Australian jazz group

* Ute (given name)

* ''Ute'' (sponge), a sponge genus

* Ute (vehicle), an Australian and New Zealand term for certain utility vehicles

* Ute, Iowa, a city in Monona County along the ...

and Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) o ...

. These Chief's Blankets, so called because only chiefs or very wealthy individuals could afford them, were characterized by horizontal stripes and minimal patterning in red. First Phase Chief's Blankets have only horizontal stripes, Second Phase feature red rectangular designs, and Third Phase features red diamonds and partial diamond patterns.

The completion of the railroads dramatically changed Navajo weaving. Cheap blankets were imported, so Navajo weavers shifted their focus to weaving rugs for an increasingly non-Native audience. Rail service also brought in Germantown wool from Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, commercially dyed wool which greatly expanded the weavers' color palettes.

Some early European-American settlers moved in and set up trading posts, often buying Navajo rugs by the pound and selling them back east by the bale. The traders encouraged the locals to weave blankets and rugs into distinct styles. These included "Two Gray Hills" (predominantly black and white, with traditional patterns); ''Teec Nos Pos'' (colorful, with very extensive patterns); "Ganado" (founded by Don Lorenzo Hubbell

John Lorenzo Hubbell (November 27, 1853 – November 12, 1930) was a member of the Arizona State Senate. He was elected to serve in the 1st Arizona State Legislature from Apache County. He served in the Senate from March 1912 until March 1914. ...

), red-dominated patterns with black and white; "Crystal" (founded by J. B. Moore); oriental and Persian styles (almost always with natural dye

Natural dyes are dyes or colorants derived from plants, invertebrates, or minerals. The majority of natural dyes are vegetable dyes from plant sources—roots, berries, bark, leaves, and wood—and other biological sources such as fungi.

Archae ...

s); "Wide Ruins", "Chinlee", banded geometric patterns; "Klagetoh", diamond-type patterns; "Red Mesa" and bold diamond patterns. Many of these patterns exhibit a fourfold symmetry, which is thought to embody traditional ideas about harmony or '' hózhǫ́''.

In the media

In 2000 the documentary '' The Return of Navajo Boy'' was shown at theSundance Film Festival

The Sundance Film Festival (formerly Utah/US Film Festival, then US Film and Video Festival) is an annual film festival organized by the Sundance Institute. It is the largest independent film festival in the United States, with more than 46,6 ...

. It was written in response to an earlier film, '' The Navajo Boy'' which was somewhat exploitative of those Navajos involved. ''The Return of Navajo Boy'' allowed the Navajos to be more involved in the depictions of themselves.

In the final episode of the third season of the FX reality TV show '' 30 Days'', the show's producer Morgan Spurlock

Morgan Valentine Spurlock (born November 7, 1970) is an American documentary filmmaker, humorist, television producer, screenwriter and playwright.

Spurlock's films include '' Super Size Me'' (2004), ''Where in the World Is Osama bin Laden?'' (20 ...

spends thirty days living with a Navajo family on their reservation in New Mexico. The July 2008 show called "Life on an Indian Reservation", depicts the dire conditions that many Native Americans experience living on reservations in the United States.

Tony Hillerman

Anthony Grove Hillerman (May 27, 1925 – October 26, 2008) was an American author of detective novels and nonfiction works, best known for his mystery novels featuring Navajo Nation Police officers Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee. Several of his w ...

wrote a series of detective novels whose detective characters were members of the Navajo Tribal Police. The novels are noted for incorporating details about Navajo culture, and in some cases expand the focus to include nearby Hopi

The Hopi are a Native American ethnic group who primarily live on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona, United States. As of the 2010 census, there are 19,338 Hopi in the country. The Hopi Tribe is a sovereign nation within the Unite ...

and Zuni characters and cultures, as well. Four of the novels have been adapted for film/TV. His daughter has continued the novel series after his death.

In 1997, Welsh author Eirug Wyn published the Welsh-language novel "I Ble'r Aeth Haul y Bore?" ("Where did the Morning Sun go?" in English) which tells the story of Carson's misdoings against the Navajo people from the point of view of a fictional young Navajo woman called "Haul y Bore" ("Morning Sun" in English).

Notable people with Navajo ancestry

* Fred Begay,

* Fred Begay, nuclear physicist

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

and a Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top: ...

veteran

* Notah Begay III

Notah Ryan Begay III (born September 14, 1972) is a Native American professional golfer. He is one of the only Native American golfers to have played in the PGA Tour. Since 2013, Begay has served as an analyst with the Golf Channel and NBC Spor ...

(Navajo-Isleta-San Felipe Pueblo), American professional golfer

* Klee Benally, musician and documentary filmmaker

* Nikki Cooley

Nikki Cooley is the co-manager for the Institute for Tribal Environmental Professional's Tribes' Climate Change Program and is the first Navajo person to gain a river rafting guide license for the Grand Canyon.

Early life and education

Nikki ...

, environmentalist, Grand Canyon river guide

* Jacoby Ellsbury

Jacoby McCabe Ellsbury ( ; born September 11, 1983) is an American former professional baseball center fielder. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Boston Red Sox from 2007 through 2013 and then played for the New York Yankees from 2 ...

, New York Yankees

The New York Yankees are an American professional baseball team based in the New York City borough of the Bronx. The Yankees compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) East division. They are one o ...

outfielder (enrolled Colorado River Indian Tribes)

* Rickie Fowler, American professional golfer

* Joe Kieyoomia

Joe Kieyoomia (November 21, 1919 – February 17, 1997) was a Navajo soldier in New Mexico's 200th Coast Artillery unit who was captured by the Imperial Japanese Army after the fall of the Philippines in 1942 during World War II. Kieyoomia w ...

, captured by the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor ...

after the fall of the Philippines in 1942

* Nicco Montaño

Nicco Montaño (born December 16, 1988) is an American mixed martial artist who last competed in the bantamweight division of the Ultimate Fighting Championship. She was the inaugural UFC Women's Flyweight Champion.

Background

Of Navajo, Chicka ...

, former women's UFC flyweight champion

* Chester Nez, the last original Navajo code talker who served in the United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through ...

during World War II.

* Krystal Tsosie

Dr. Krystal Tsosie (Diné) is a Navajo geneticist and bioethicist at Arizona State University and activist for Indigenous data sovereignty. She is also an educator and an expert on genetic and social identities. Her advocacy and academic work ...

, geneticist and bioethicist known for promoting Indigenous data sovereignty and studying genetics within Indigenous communities

* Lance Tsosie, TikToker whose videos discuss North American Native culture and history.

* Cory Witherill, first full-blooded Native American in NASCAR

The National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, LLC (NASCAR) is an American auto racing sanctioning and operating company that is best known for stock car racing. The privately owned company was founded by Bill France Sr. in 1948, and h ...

* Aaron Yazzie, mechanical engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) is a federally funded research and development center and NASA field center in the City of La Cañada Flintridge, California, United States.

Founded in the 1930s by Caltech researchers, JPL is owned by NASA ...

Artists

* Beatien Yazz (born 1928), painter * Apie Begay (fl. 1902), first Navajo artist to use European drawing materials *Harrison Begay

Harrison Begay, also known as Haashké yah Níyá (meaning "Warrior Who Walked Up to His Enemy" or "Wandering Boy") (November 15, 1914 or 1917 – August 18, 2012) was a renowned Diné (Navajo) painter, printmaker, and illustrator. Begay speciali ...

(1914–2012), Studio

A studio is an artist or worker's workroom. This can be for the purpose of acting, architecture, painting, pottery (ceramics), sculpture, origami, woodworking, scrapbooking, photography, graphic design, filmmaking, animation, industrial design, ...

painter

* Joyce Begay-Foss, weaver, educator, and museum curator

* Mary Holiday Black (born c. 1934), basket maker

* Raven Chacon

Raven Chacon (born 1977) is a Diné-American composer, musician and artist. Born in Fort Defiance, Arizona within the Navajo Nation, Chacon became the first Native American to win a Pulitzer Prize for Music, for his '' Voiceless Mass'' in 2022.

...

(born 1977), conceptual artist

* Lorenzo Clayton (born 1940), artist

*Carl Nelson Gorman

Dr. Carl Nelson Gorman, also known as Kin-Ya-Onny-Beyeh (1907–1998) was a Navajo code talker, visual artist, painter, illustrator, and professor. He was faculty at the University of California, Davis, from 1950 until 1973. During World War II, G ...

(also known as Kin-Ya-Onny-Beyeh; 1907–1998), painter, printmaker, illustrator, and Navajo code talker with the U.S. Marine Corp during World War II.

* R. C. Gorman (1932–2005), painter and printmaker

* Hastiin Klah, weaver and co-founder of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian

The Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian is a museum devoted to Native American arts. It is located in Santa Fe, New Mexico and was founded in 1937 by Mary Cabot Wheelwright, who came from Boston, and Hastiin Klah, a Navajo singer and medic ...

* David Johns (born 1948), painter

* Yazzie Johnson, contemporary silversmith

* Betty Manygoats, Tàchii'nii, contemporary ceramicist

* Christine Nofchissey McHorse (1948-2021), ceramicist

* Gerald Nailor, Sr. (1917–1952), studio painter

* Barbara Teller Ornelas (born 1954), master Navajo weaver

Navajo rugs and blankets ( nv, ) are textiles produced by Navajo people of the Four Corners area of the United States. Navajo textiles are highly regarded and have been sought after as trade items for over 150 years. Commercial production of han ...

, cultural ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or so ...

of the U.S. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

* Atsidi Sani (c. 1828–1918), first known Navajo silversmith

* Clara Nezbah Sherman, weaver

* Ryan Singer, painter, illustrator, screen printer

* Tommy Singer, silversmith and jeweler

* Quincy Tahoma

Quincy Tahoma (1921–1956) was a Navajo painter from Arizona and New Mexico.

Biography

Youth

Quincy Tahoma was born near Tuba City, Arizona on Christmas Day 1921. Tahoma means "Water Edge".Klah Tso (mid-19th century — early 20th century), pioneering easel painter

* Emmi Whitehorse, contemporary painter

*

/ref> *

''The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths''

Norman: Oklahoma Press, 1989. . *Iverson, Peter, Jennifer Nez Denetdale, and Ada E. Deer

''The Navajo.''

New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2006. . * Kehoe, Alice Beck. ''North American Indians: A Comprehensive account''. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2005. * * Pritzker, Barry M. ''A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. . * Sandner, Donald

''Navaho symbols of healing: a Jungian exploration of ritual, image, and medicine.''

Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press, 1991. . * Sides, Hampton, ''Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West''. Doubleday (2006).

Removing Classrooms from the Battlefield: Liberty, Paternalism, and the Redemptive Promise of Educational Choice, 2008 BYU Law Review 377 The Navajo and Richard Henry Pratt

* Zaballos, Nausica (2009). ''Le système de santé navajo''. Paris: L'Harmattan.

Navajo Nation

official site

Navajo Tourism DepartmentNavajo people: history, culture, language, art

of Northern Colorado University with images of U.S. documents of treaties and reports 1846–1931

Navajo Silversmiths

by

Navajo Institute for Social JusticeNavajo Arts

Information on authentic Navajo Art, Rugs, Jewelry, and Crafts

The Navajo

Navajo expert, Doctor Sarah Davis, about the Navajo * {{DEFAULTSORT:Navajo people Native American history of Arizona Native American history of New Mexico Native American history of Utah Native American tribes in Arizona Native American tribes in New Mexico Native American tribes in Utah

Melanie Yazzie

Melanie Yazzie is a Navajo sculptor, painter, printmaker, and professor. She teaches at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Early life and education

Yazzie was born in 1966 in Ganado, Arizona, United States. She is Navajo of the , born for .< ...

, contemporary print maker and educator

* Teresa Montoya

Teresa Montoya is a Diné media maker and social scientist with training in socio-cultural anthropology, critical Indigenous studies, and filmmaking.

Early life

Teresa grew up in Western Colorado.

Teresa received a Bachelor of Arts (BA) at th ...

, film maker

Performers

* Jeremiah Bitsui, actor * Blackfire, punk/alternative rock band *Raven Chacon

Raven Chacon (born 1977) is a Diné-American composer, musician and artist. Born in Fort Defiance, Arizona within the Navajo Nation, Chacon became the first Native American to win a Pulitzer Prize for Music, for his '' Voiceless Mass'' in 2022.

...

, composer

* Radmilla Cody, traditional singer

* James and Ernie, comedy duo

* R. Carlos Nakai, musician

* Jock Soto, ballet dancer

Politicians

* Christina Haswood, member of theKansas House of Representatives

The Kansas House of Representatives is the lower house of the legislature of the U.S. state of Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocke ...

since 2021.

* Henry Chee Dodge, last Head Chief of the Navajo and first Chairman of the Navajo Tribe, (1922–1928, 1942–1946).

* Peterson Zah, first President of the Navajo Nation

The Navajo Nation ( nv, Naabeehó Bináhásdzo), also known as Navajoland, is a Native Americans in the United States, Native American Indian reservation, reservation in the United States. It occupies portions of northeastern Arizona, northwe ...

and last Chairman of the Navajo Tribe.Peterson Zah Biography/ref> *

Albert Hale

Albert A. Hale (March 13, 1950 – February 2, 2021) was an American attorney and politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in the Arizona Senate from 2004 to 2011 and in the Arizona House of Representatives from 2011 to 2017.

A m ...

, former President of the Navajo Nation. He served in the Arizona Senate from 2004 to 2011 and in the Arizona House of Representatives from 2011 to 2017.

* Jonathan Nez, Current President of the Navajo Nation. He served three terms as Navajo Council Delegate representing the chapters of Shonto, Oljato, Tsah Bi Kin and Navajo Mountain. Served two terms as Navajo County Board of Supervisors for District 1.

* Annie Dodge Wauneka, former Navajo Tribal Councilwoman and advocate.

* Thomas Dodge, former Chairman of the Navajo Tribe and first Diné attorney.

* Peter MacDonald, Navajo Code Talker and former Chairman of the Navajo Tribe.

* Mark Maryboy

Mark Maryboy (born December 10, 1955) is a retired American politician for San Juan County, Utah, and a former Navajo Nation Council Delegate for the Utah Navajo Section of the Navajo Tribe. He is the brother of Kenneth Maryboy who currently ...

( Aneth/ Red Mesa/Mexican Water), former Navajo Nation Council Delegate, working in Utah Navajo Investments.

* Lilakai Julian Neil, the first woman elected to Navajo Tribal Council.

* Joe Shirley, Jr.

Joe Shirley Jr. (born December 4, 1947) is a Navajo politician who is the only two-term President of the Navajo Nation. He served as president from 2003 to 2011. He lives in Chinle, Arizona, and is Tódích'íi'nii, born for Tábaahá.

Person ...

, former President of the Navajo Nation.

* Ben Shelly, former President of the Navajo Nation.

* Chris Stearns, member of the Washington House of Representatives

The Washington House of Representatives is the lower house of the Washington State Legislature, and along with the Washington State Senate makes up the legislature of the U.S. state of Washington. It is composed of 98 Representatives from 49 ...

since 2022.

* Chris Deschene

Christopher L. Clark Deschene is an American politician, attorney, and energy development expert. A member of the Navajo Nation, Deschene was the Democratic Party's candidate for Secretary of State in Arizona in 2010, and served as a Department ...

, veteran, attorney, engineer, and a community leader. One of few Native Americans to be accepted into the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. Upon graduation, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lt. in the U.S. Marine Corps. He made an unsuccessful attempt to run for Navajo Nation President.

Writers

*Freddie Bitsoie

Freddie J. Bitsoie is a Navajo chef and author. He was the Executive Chef for the Mitsitam Native Foods Café at the National Museum of the American Indian.

Bitsoie was born in Utah to Diné parents and moved frequently between Albuquerque's Sand ...

, author and chef

* Sherwin Bitsui

Sherwin Bitsui is a Navajo writer and poet. His book, ''Flood Song'', won the American Book Award and the PEN Open Book Award.

Life and Education

Bitsui was born in 1974. He is originally from Whitecone, Arizona.

He is Navajo people, Navajo; his ...

, author and poet

* Luci Tapahonso, poet and lecturer

* Elizabeth Woody

Elizabeth Woody (born 1959) is an American Navajo/ Warm Springs/Wasco/Yakama artist, author, and educator. In March 2016, she was the first Native American to be named poet laureate of Oregon by Governor Kate Brown.

Background

Elizabeth Woody w ...

, author, educator, and environmentalist

See also

* Navajo-Churro sheep *Navajo pueblitos

The term Navajo Pueblitos, also known as Dinétah Pueblitos, refers to a class of archaeological sites that are found in the northwestern corner of the American state of New Mexico. The sites generally consist of relatively small stone and ti ...

* Navajo Nation

The Navajo Nation ( nv, Naabeehó Bináhásdzo), also known as Navajoland, is a Native Americans in the United States, Native American Indian reservation, reservation in the United States. It occupies portions of northeastern Arizona, northwe ...

* Long Walk of the Navajo

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo ( nv, Hwéeldi), was the 1864 deportation and attempted ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people by the United States federal government. Navajos were forced to walk from t ...

Notes

References

*Adair, John''The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths''

Norman: Oklahoma Press, 1989. . *Iverson, Peter, Jennifer Nez Denetdale, and Ada E. Deer

''The Navajo.''

New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2006. . * Kehoe, Alice Beck. ''North American Indians: A Comprehensive account''. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2005. * * Pritzker, Barry M. ''A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. . * Sandner, Donald

''Navaho symbols of healing: a Jungian exploration of ritual, image, and medicine.''

Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press, 1991. . * Sides, Hampton, ''Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West''. Doubleday (2006).

Further reading

* Bailey, L. R. (1964). ''The Long Walk: A History of the Navaho Wars, 1846–1868''. * Bighorse, Tiana (1990). ''Bighorse the Warrior''. Ed. Noel Bennett, Tucson: University of Arizona Press. * * Clarke, Dwight L. (1961). ''Stephen Watts Kearny: Soldier of the West''. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. * Downs, James F. (1972). ''The Navajo''. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. * * * Hammond, George P. and Rey, Agapito (editors) (1940). ''Narratives of the Coronado Expedition 1540–1542.'' Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. * Iverson, Peter (2002). ''Diné: A History of the Navahos''. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. . * Kelly, Lawrence (1970). ''Navajo Roundup'' Pruett Pub. Co., Colorado. * Linford, Laurence D. (2000). ''Navajo Places: History, Legend, Landscape''. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. * McNitt, Frank (1972). ''Navajo Wars''. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. * Plog, Stephen ''Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest''. Thames and London, LTD, London, England, 1997. . * Roessel, Ruth (editor) (1973). ''Navajo Stories of the Long Walk Period''. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community College Press. * * Voyles, Traci Brynne (2015). ''Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country.'' Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. * * Witherspoon, Gary (1977). ''Language and Art in the Navajo Universe''. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. * Witte, DanielRemoving Classrooms from the Battlefield: Liberty, Paternalism, and the Redemptive Promise of Educational Choice, 2008 BYU Law Review 377 The Navajo and Richard Henry Pratt

* Zaballos, Nausica (2009). ''Le système de santé navajo''. Paris: L'Harmattan.

External links

Navajo Nation

official site

Navajo Tourism Department

of Northern Colorado University with images of U.S. documents of treaties and reports 1846–1931

Navajo Silversmiths

by

Washington Matthews

Washington Matthews (June 17, 1843 – March 2, 1905) was a surgeon in the United States Army, ethnographer, and linguist known for his studies of Native American peoples, especially the Navajo.

Early life and education

Matthews was born in ...

, 1883 from Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital li ...

Navajo Institute for Social Justice

Information on authentic Navajo Art, Rugs, Jewelry, and Crafts

The Navajo

Navajo expert, Doctor Sarah Davis, about the Navajo * {{DEFAULTSORT:Navajo people Native American history of Arizona Native American history of New Mexico Native American history of Utah Native American tribes in Arizona Native American tribes in New Mexico Native American tribes in Utah