NHMUK on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The Natural History Museum's main frontage, however, is on Cromwell Road.

The museum is home to life and earth science specimens comprising some 80 million items within five main collections: botany,

The foundation of the collection was that of the Ulster doctor Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), who allowed his significant collections to be purchased by the British Government at a price well below their market value at the time. This purchase was funded by a lottery. Sloane's collection, which included dried plants, and animal and human skeletons, was initially housed in Montagu House, Bloomsbury, in 1756, which was the home of the British Museum.

Most of the Sloane collection had disappeared by the early decades of the nineteenth century. Dr

The foundation of the collection was that of the Ulster doctor Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), who allowed his significant collections to be purchased by the British Government at a price well below their market value at the time. This purchase was funded by a lottery. Sloane's collection, which included dried plants, and animal and human skeletons, was initially housed in Montagu House, Bloomsbury, in 1756, which was the home of the British Museum.

Most of the Sloane collection had disappeared by the early decades of the nineteenth century. Dr

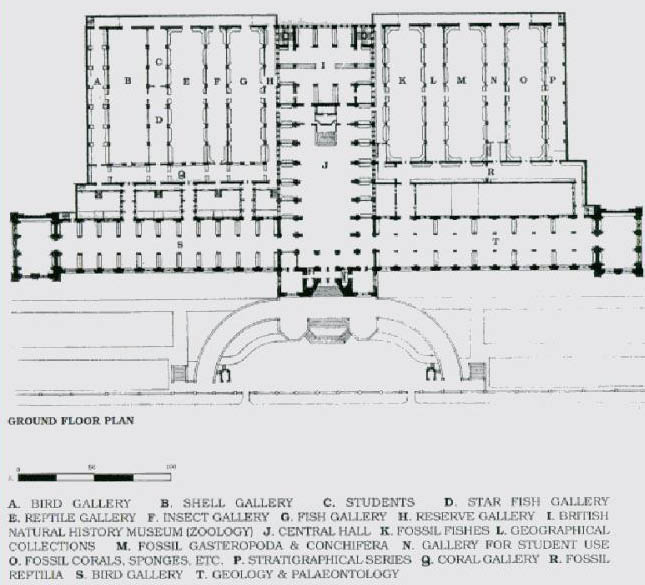

Owen saw that the natural history departments needed more space, and that implied a separate building as the British Museum site was limited. Land in South Kensington was purchased, and in 1864 a competition was held to design the new museum. The winning entry was submitted by the civil engineer Captain Francis Fowke, who died shortly afterwards. The scheme was taken over by Alfred Waterhouse who substantially revised the agreed plans, and designed the façades in his own idiosyncratic Romanesque style which was inspired by his frequent visits to the Continent. The original plans included wings on either side of the main building, but these plans were soon abandoned for budgetary reasons. The space these would have occupied are now taken by the Earth Galleries and Darwin Centre.

Owen saw that the natural history departments needed more space, and that implied a separate building as the British Museum site was limited. Land in South Kensington was purchased, and in 1864 a competition was held to design the new museum. The winning entry was submitted by the civil engineer Captain Francis Fowke, who died shortly afterwards. The scheme was taken over by Alfred Waterhouse who substantially revised the agreed plans, and designed the façades in his own idiosyncratic Romanesque style which was inspired by his frequent visits to the Continent. The original plans included wings on either side of the main building, but these plans were soon abandoned for budgetary reasons. The space these would have occupied are now taken by the Earth Galleries and Darwin Centre. Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened in 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of architectural terracotta tiles to resist the sooty atmosphere of

Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened in 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of architectural terracotta tiles to resist the sooty atmosphere of

Even after the opening, the Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name British Museum (Natural History), usually abbreviated in the scientific literature as ''B.M.(N.H.)''. A petition to the

Even after the opening, the Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name British Museum (Natural History), usually abbreviated in the scientific literature as ''B.M.(N.H.)''. A petition to the

The Darwin Centre (named after Charles Darwin) was designed as a new home for the museum's collection of tens of millions of preserved specimens, as well as new work spaces for the museum's scientific staff and new educational visitor experiences. Built in two distinct phases, with two new buildings adjacent to the main Waterhouse building, it is the most significant new development project in the museum's history.

Phase one of the Darwin Centre opened to the public in 2002, and it houses the zoological department's 'spirit collections'—organisms preserved in

The Darwin Centre (named after Charles Darwin) was designed as a new home for the museum's collection of tens of millions of preserved specimens, as well as new work spaces for the museum's scientific staff and new educational visitor experiences. Built in two distinct phases, with two new buildings adjacent to the main Waterhouse building, it is the most significant new development project in the museum's history.

Phase one of the Darwin Centre opened to the public in 2002, and it houses the zoological department's 'spirit collections'—organisms preserved in

Nature Live

talks on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

One of the most famous and certainly most prominent of the exhibits—nicknamed "

One of the most famous and certainly most prominent of the exhibits—nicknamed " The blue whale skeleton, Hope, that has replaced Dippy, is another prominent display in the museum. The display of the skeleton, some long and weighing 4.5 tonnes, was only made possible in 1934 with the building of the New Whale Hall (now the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery). The whale had been in storage for 42 years since its stranding on sandbanks at the mouth of Wexford Harbour, Ireland in March 1891 after being injured by whalers. At this time, it was first displayed in the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery, but now takes pride of place in the museum's Hintze Hall. Discussion of the idea of a life-sized model also began around 1934, and work was undertaken within the Whale Hall itself. Since taking a cast of such a large animal was deemed prohibitively expensive, scale models were used to meticulously piece the structure together. During construction, workmen left a trapdoor within the whale's stomach, which they would use for surreptitious cigarette breaks. Before the door was closed and sealed forever, some coins and a telephone directory were placed inside—this soon growing to an urban myth that a time capsule was left inside. The work was completed—entirely within the hall and in view of the public—in 1938. At the time it was the largest such model in the world, at in length. The construction details were later borrowed by several American museums, who scaled the plans further. The work involved in removing Dippy and replacing it with Hope was documented in a BBC Television special, ''

The blue whale skeleton, Hope, that has replaced Dippy, is another prominent display in the museum. The display of the skeleton, some long and weighing 4.5 tonnes, was only made possible in 1934 with the building of the New Whale Hall (now the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery). The whale had been in storage for 42 years since its stranding on sandbanks at the mouth of Wexford Harbour, Ireland in March 1891 after being injured by whalers. At this time, it was first displayed in the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery, but now takes pride of place in the museum's Hintze Hall. Discussion of the idea of a life-sized model also began around 1934, and work was undertaken within the Whale Hall itself. Since taking a cast of such a large animal was deemed prohibitively expensive, scale models were used to meticulously piece the structure together. During construction, workmen left a trapdoor within the whale's stomach, which they would use for surreptitious cigarette breaks. Before the door was closed and sealed forever, some coins and a telephone directory were placed inside—this soon growing to an urban myth that a time capsule was left inside. The work was completed—entirely within the hall and in view of the public—in 1938. At the time it was the largest such model in the world, at in length. The construction details were later borrowed by several American museums, who scaled the plans further. The work involved in removing Dippy and replacing it with Hope was documented in a BBC Television special, ''

This is the zone that can be entered from Exhibition Road, on the East side of the building. It is a gallery themed around the changing history of the Earth.

''Earth's Treasury'' shows specimens of rocks, minerals and gemstones behind glass in a dimly lit gallery. ''Lasting Impressions'' is a small gallery containing specimens of rocks, plants and minerals, of which most can be touched.

* Earth Hall ('' Stegosaurus'' skeleton)

* Human Evolution

* Earth's Treasury

* Lasting Impressions

* Restless Surface

* From the Beginning

* Volcanoes and Earthquakes

* The Waterhouse Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

This is the zone that can be entered from Exhibition Road, on the East side of the building. It is a gallery themed around the changing history of the Earth.

''Earth's Treasury'' shows specimens of rocks, minerals and gemstones behind glass in a dimly lit gallery. ''Lasting Impressions'' is a small gallery containing specimens of rocks, plants and minerals, of which most can be touched.

* Earth Hall ('' Stegosaurus'' skeleton)

* Human Evolution

* Earth's Treasury

* Lasting Impressions

* Restless Surface

* From the Beginning

* Volcanoes and Earthquakes

* The Waterhouse Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

This zone is accessed from the Cromwell Road entrance via the Hintze Hall and follows the theme of the evolution of the planet.

* Birds

* Creepy Crawlies

* Fossil Marine Reptiles

* Hintze Hall (formerly the Central Hall, with blue whale skeleton and giant sequoia)

* Minerals

* The Vault

* Fossils from Britain

* Anning Rooms (exclusive space for members and patrons of the museum)

* Investigate

* East Pavilion (space for changing Wildlife Photographer of the Year exhibition)

This zone is accessed from the Cromwell Road entrance via the Hintze Hall and follows the theme of the evolution of the planet.

* Birds

* Creepy Crawlies

* Fossil Marine Reptiles

* Hintze Hall (formerly the Central Hall, with blue whale skeleton and giant sequoia)

* Minerals

* The Vault

* Fossils from Britain

* Anning Rooms (exclusive space for members and patrons of the museum)

* Investigate

* East Pavilion (space for changing Wildlife Photographer of the Year exhibition)

To the left of the Hintze Hall, this zone explores the diversity of life on the planet.

* Dinosaurs

* Fish, Amphibians and Reptiles

* Human Biology

* Images of Nature

* The Jerwood Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

* Marine Invertebrates

* Mammals

* Mammals Hall ( blue whale model)

* Treasures in the Cadogan Gallery

To the left of the Hintze Hall, this zone explores the diversity of life on the planet.

* Dinosaurs

* Fish, Amphibians and Reptiles

* Human Biology

* Images of Nature

* The Jerwood Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

* Marine Invertebrates

* Mammals

* Mammals Hall ( blue whale model)

* Treasures in the Cadogan Gallery

Enables the public to see science at work and also provides spaces for relaxation and contemplation. Accessible from Queens Gate.

* Wildlife Garden

* Darwin Centre

* Zoology Spirit Building

Enables the public to see science at work and also provides spaces for relaxation and contemplation. Accessible from Queens Gate.

* Wildlife Garden

* Darwin Centre

* Zoology Spirit Building

The museum runs a series of educational and public engagement programmes. These include for example a highly praised "How Science Works" hands on workshop for school students demonstrating the use of microfossils in geological research. The museum also played a major role in securing designation of the Jurassic Coast of Devon and Dorset as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has subsequently been a lead partner in the Lyme Regis Fossil Festivals.

In 2005, the museum launched a project to develop notable gallery characters to patrol display cases, including 'facsimiles' of Carl Linnaeus, Mary Anning, Dorothea Bate and William Smith. They tell stories and anecdotes of their lives and discoveries and aim to surprise visitors.

In 2010, a six-part BBC documentary series was filmed at the museum entitled ''

The museum runs a series of educational and public engagement programmes. These include for example a highly praised "How Science Works" hands on workshop for school students demonstrating the use of microfossils in geological research. The museum also played a major role in securing designation of the Jurassic Coast of Devon and Dorset as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has subsequently been a lead partner in the Lyme Regis Fossil Festivals.

In 2005, the museum launched a project to develop notable gallery characters to patrol display cases, including 'facsimiles' of Carl Linnaeus, Mary Anning, Dorothea Bate and William Smith. They tell stories and anecdotes of their lives and discoveries and aim to surprise visitors.

In 2010, a six-part BBC documentary series was filmed at the museum entitled ''

Picture Library of the Natural History Museum

The Natural History Museum on Google Cultural Institute

Architectural history and description

from the '' Survey of London''

Architecture and history of the NHM

from the Royal Institute of British Architects * Maps of

Nature News article on proposed cuts, June 2010

{{Authority control British Museum Natural history museums in London Museums sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Grade I listed buildings in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Grade I listed museum buildings Cultural infrastructure completed in 1880 Alfred Waterhouse buildings Non-departmental public bodies of the United Kingdom government Exempt charities Charities based in London Museums in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Romanesque Revival architecture in England Terracotta Museums established in 1881 1881 establishments in England National museums of England Dinosaur museums Natural History Museum, London South Kensington

entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

, mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...

, palaeontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

and zoology. The museum is a centre of research specialising in taxonomy, identification and conservation. Given the age of the institution, many of the collections have great historical as well as scientific value, such as specimens collected by Charles Darwin. The museum is particularly famous for its exhibition of dinosaur skeletons and ornate architecture—sometimes dubbed a ''cathedral of nature''—both exemplified by the large '' Diplodocus'' cast that dominated the vaulted central hall before it was replaced in 2017 with the skeleton of a blue whale hanging from the ceiling. The Natural History Museum Library contains an extensive collection of books, journals, manuscripts, and artwork linked to the work and research of the scientific departments; access to the library is by appointment only. The museum is recognised as the pre-eminent centre of natural history and research of related fields in the world.

Although commonly referred to as the Natural History Museum, it was officially known as British Museum (Natural History) until 1992, despite legal separation from the British Museum itself in 1963. Originating from collections within the British Museum, the landmark Alfred Waterhouse

Alfred Waterhouse (19 July 1830 – 22 August 1905) was an English architect, particularly associated with the Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, although he designed using other architectural styles as well. He is perhaps best known f ...

building was built and opened by 1881 and later incorporated the Geological Museum. The Darwin Centre is a more recent addition, partly designed as a modern facility for storing the valuable collections.

Like other publicly funded national museums in the United Kingdom, the Natural History Museum does not charge an admission fee.

The museum is an exempt charity and a non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. The Princess of Wales

Princess of Wales (Welsh: ''Tywysoges Cymru'') is a courtesy title used since the 14th century by the wife of the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. The current title-holder is Catherine (née Middleton).

The title was fir ...

, is a patron of the museum. There are approximately 850 staff at the museum. The two largest strategic groups are the Public Engagement Group and Science Group.

History

Early history

George Shaw George Shaw may refer to:

* George Shaw (biologist) (1751–1813), English botanist and zoologist

* George B. Shaw (1854–1894), U.S. Representative from Wisconsin

* George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950), Irish playwright

* George C. Shaw (1866–196 ...

(Keeper of Natural History 1806–1813) sold many specimens to the Royal College of Surgeons and had periodic ''cremations'' of material in the grounds of the museum. His successors also applied to the trustees for permission to destroy decayed specimens. In 1833, the Annual Report states that, of the 5,500 insects listed in the Sloane catalogue, none remained. The inability of the natural history departments to conserve its specimens became notorious: the Treasury refused to entrust it with specimens collected at the government's expense. Appointments of staff were bedevilled by gentlemanly favouritism; in 1862 a nephew of the mistress of a Trustee was appointed Entomological Assistant despite not knowing the difference between a butterfly and a moth.

J. E. Gray (Keeper of Zoology 1840–1874) complained of the incidence of mental illness amongst staff: George Shaw threatened to put his foot on any shell not in the 12th edition

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1. I ...

of Linnaeus' ''Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the system, now known as binomial nomen ...

''; another had removed all the labels and registration numbers from entomological cases arranged by a rival. The huge collection of the conchologist

Conchology () is the study of mollusc shells. Conchology is one aspect of malacology, the study of molluscs; however, malacology is the study of molluscs as whole organisms, whereas conchology is confined to the study of their shells. It includ ...

Hugh Cuming was acquired by the museum, and Gray's own wife had carried the open trays across the courtyard in a gale: all the labels blew away. That collection is said never to have recovered.

The Principal Librarian at the time was Antonio Panizzi

Sir Antonio Genesio Maria Panizzi (16 September 1797 – 8 April 1879), better known as Anthony Panizzi, was a naturalised British citizen of Italian birth, and an Italian patriot. He was a librarian, becoming the Principal Librarian (i.e. head ...

; his contempt for the natural history departments and for science in general was total. The general public was not encouraged to visit the museum's natural history exhibits. In 1835 to a Select Committee of Parliament, Sir Henry Ellis Henry Ellis may refer to:

* Henry Augustus Ellis (1861–1939), Irish Australian physician and federalist

* Henry Ellis (diplomat) (1788–1855), British diplomat

* Henry Ellis (governor) (1721–1806), explorer, author, and second colonial Gover ...

said this policy was fully approved by the Principal Librarian and his senior colleagues.

Many of these faults were corrected by the palaeontologist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

, appointed Superintendent of the natural history departments of the British Museum in 1856. His changes led Bill Bryson to write that "by making the Natural History Museum an institution for everyone, Owen transformed our expectations of what museums are for".

Planning and architecture of new building

Owen saw that the natural history departments needed more space, and that implied a separate building as the British Museum site was limited. Land in South Kensington was purchased, and in 1864 a competition was held to design the new museum. The winning entry was submitted by the civil engineer Captain Francis Fowke, who died shortly afterwards. The scheme was taken over by Alfred Waterhouse who substantially revised the agreed plans, and designed the façades in his own idiosyncratic Romanesque style which was inspired by his frequent visits to the Continent. The original plans included wings on either side of the main building, but these plans were soon abandoned for budgetary reasons. The space these would have occupied are now taken by the Earth Galleries and Darwin Centre.

Owen saw that the natural history departments needed more space, and that implied a separate building as the British Museum site was limited. Land in South Kensington was purchased, and in 1864 a competition was held to design the new museum. The winning entry was submitted by the civil engineer Captain Francis Fowke, who died shortly afterwards. The scheme was taken over by Alfred Waterhouse who substantially revised the agreed plans, and designed the façades in his own idiosyncratic Romanesque style which was inspired by his frequent visits to the Continent. The original plans included wings on either side of the main building, but these plans were soon abandoned for budgetary reasons. The space these would have occupied are now taken by the Earth Galleries and Darwin Centre. Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened in 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of architectural terracotta tiles to resist the sooty atmosphere of

Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened in 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of architectural terracotta tiles to resist the sooty atmosphere of Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

London, manufactured by the Tamworth-based company of Gibbs and Canning Limited. The tiles and bricks feature many relief sculptures of flora and fauna, with living and extinct species featured within the west and east wings respectively. This explicit separation was at the request of Owen, and has been seen as a statement of his contemporary rebuttal of Darwin's attempt to link present species with past through the theory of natural selection. Though Waterhouse slipped in a few anomalies, such as bats amongst the extinct animals and a fossil ammonite with the living species. The sculptures were produced from clay models by a French sculptor based in London, M Dujardin, working to drawings prepared by the architect.

The central axis of the museum is aligned with the tower of Imperial College London (formerly the Imperial Institute) and the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

and Albert Memorial further north. These all form part of the complex known colloquially as Albertopolis.

Separation from the British Museum

Even after the opening, the Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name British Museum (Natural History), usually abbreviated in the scientific literature as ''B.M.(N.H.)''. A petition to the

Even after the opening, the Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name British Museum (Natural History), usually abbreviated in the scientific literature as ''B.M.(N.H.)''. A petition to the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

was made in 1866, signed by the heads of the Royal, Linnean and Zoological societies as well as naturalists including Darwin

Darwin may refer to:

Common meanings

* Charles Darwin (1809–1882), English naturalist and writer, best known as the originator of the theory of biological evolution by natural selection

* Darwin, Northern Territory, a territorial capital city i ...

, Wallace

Wallace may refer to:

People

* Clan Wallace in Scotland

* Wallace (given name)

* Wallace (surname)

* Wallace (footballer, born 1986), full name Wallace Fernando Pereira, Brazilian football left-back

* Wallace (footballer, born 1987), full name ...

and Huxley

Huxley may refer to:

People

* Huxley (surname)

* The British Huxley family

* Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895), British biologist known as "Darwin's Bulldog"

* Aldous Huxley (1894–1963), British writer, author of ''Brave New World'', grandson ...

, asking that the museum gain independence from the board of the British Museum, and heated discussions on the matter continued for nearly one hundred years. Finally, with the passing of the British Museum Act 1963

The British Museum Act 1963 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It replaced the British Museum Act 1902. The Act forbids the Museum from disposing of its holdings, except in a small number of special circumstances. In May 2005 a ...

, the British Museum (Natural History) became an independent museum with its own board of trustees, although – despite a proposed amendment to the act in the House of Lords – the former name was retained. In 1989 the museum publicly re-branded itself as the Natural History Museum and stopped using the title British Museum (Natural History) on its advertising and its books for general readers. Only with the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 did the museum's formal title finally change to the Natural History Museum.

Geological Museum

In 1985, the museum merged with the adjacent Geological Museum of theBritish Geological Survey

The British Geological Survey (BGS) is a partly publicly funded body which aims to advance geoscientific knowledge of the United Kingdom landmass and its continental shelf by means of systematic surveying, monitoring and research.

The BGS h ...

, which had long competed for the limited space available in the area. The Geological Museum became world-famous for exhibitions including an active volcano model and an earthquake machine (designed by James Gardner), and housed the world's first computer-enhanced exhibition (''Treasures of the Earth''). The museum's galleries were completely rebuilt and relaunched in 1996 as ''The Earth Galleries'', with the other exhibitions in the Waterhouse building retitled ''The Life Galleries''. The Natural History Museum's own mineralogy displays remain largely unchanged as an example of the 19th-century display techniques of the Waterhouse building.

The central atrium design by Neal Potter overcame visitors' reluctance to visit the upper galleries by "pulling" them through a model of the Earth made up of random plates on an escalator. The new design covered the walls in recycled slate and sandblasted the major stars and planets onto the wall. The museum's 'star' geological exhibits are displayed within the walls. Six iconic figures were the backdrop to discussing how previous generations have viewed Earth. These were later removed to make place for a '' Stegosaurus'' skeleton that was put on display in late 2015.

The Darwin Centre

The Darwin Centre (named after Charles Darwin) was designed as a new home for the museum's collection of tens of millions of preserved specimens, as well as new work spaces for the museum's scientific staff and new educational visitor experiences. Built in two distinct phases, with two new buildings adjacent to the main Waterhouse building, it is the most significant new development project in the museum's history.

Phase one of the Darwin Centre opened to the public in 2002, and it houses the zoological department's 'spirit collections'—organisms preserved in

The Darwin Centre (named after Charles Darwin) was designed as a new home for the museum's collection of tens of millions of preserved specimens, as well as new work spaces for the museum's scientific staff and new educational visitor experiences. Built in two distinct phases, with two new buildings adjacent to the main Waterhouse building, it is the most significant new development project in the museum's history.

Phase one of the Darwin Centre opened to the public in 2002, and it houses the zoological department's 'spirit collections'—organisms preserved in alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

. Phase Two was unveiled in September 2008 and opened to the general public in September 2009. It was designed by the Danish architecture practice C. F. Møller Architects

Arkitektfirmaet C. F. Møller, internationally also known as C. F. Møller Architects, is an architectural firm based in Århus, Denmark. Founded in 1924 by C. F. Møller, it is today the largest architectural firm in Denmark based on number of em ...

in the shape of a giant, eight-story cocoon and houses the entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

and botanical collections—the 'dry collections'. It is possible for members of the public to visit and view non-exhibited items for a fee by booking onto one of the several Spirit Collection Tours offered daily.

Arguably the most famous creature in the centre is the 8.62-metre-long giant squid, affectionately named Archie.

The Attenborough Studio

As part of the museum's remit to communicate science education and conservation work, a new multimedia studio forms an important part of Darwin Centre Phase 2. In collaboration with the BBC's Natural History Unit (holder of the largest archive of natural history footage) the Attenborough Studio—named after the broadcaster SirDavid Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and author. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Natural History Unit, the nine natural histor ...

—provides a multimedia environment for educational events. The studio holds regular lectures and demonstrations, including freNature Live

talks on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

Major specimens and exhibits

Dippy

Dippy is a composite ''Diplodocus'' skeleton in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the holotype of the species ''Diplodocus carnegii''. It is considered the most famous single dinosaur skeleton in the world, due to the numerous ...

"—is a -long replica of a '' Diplodocus carnegii'' skeleton which was on display for many years within the central hall. The cast was given as a gift by the Scottish-American industrialist Andrew Carnegie, after a discussion with King Edward VII, then a keen trustee of the British Museum. Carnegie paid £2,000 () for the casting, copying the original held at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The pieces were sent to London in 36 crates, and on 12 May 1905, the exhibit was unveiled to great public and media interest. The real fossil had yet to be mounted, as the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh was still being constructed to house it. As word of Dippy spread, Mr Carnegie paid to have additional copies made for display in most major European capitals and in Central and South America, making Dippy the most-viewed dinosaur skeleton in the world. The dinosaur quickly became an iconic representation of the museum, and has featured in many cartoons and other media, including the 1975 Disney comedy '' One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing''. After 112 years on display at the museum, the dinosaur replica was removed in early 2017 to be replaced by the actual skeleton of a young blue whale, a 128-year-old skeleton nicknamed "Hope". Dippy went on a tour of various British museums starting in 2018 and concluding in 2020 at Norwich Cathedral.

The blue whale skeleton, Hope, that has replaced Dippy, is another prominent display in the museum. The display of the skeleton, some long and weighing 4.5 tonnes, was only made possible in 1934 with the building of the New Whale Hall (now the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery). The whale had been in storage for 42 years since its stranding on sandbanks at the mouth of Wexford Harbour, Ireland in March 1891 after being injured by whalers. At this time, it was first displayed in the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery, but now takes pride of place in the museum's Hintze Hall. Discussion of the idea of a life-sized model also began around 1934, and work was undertaken within the Whale Hall itself. Since taking a cast of such a large animal was deemed prohibitively expensive, scale models were used to meticulously piece the structure together. During construction, workmen left a trapdoor within the whale's stomach, which they would use for surreptitious cigarette breaks. Before the door was closed and sealed forever, some coins and a telephone directory were placed inside—this soon growing to an urban myth that a time capsule was left inside. The work was completed—entirely within the hall and in view of the public—in 1938. At the time it was the largest such model in the world, at in length. The construction details were later borrowed by several American museums, who scaled the plans further. The work involved in removing Dippy and replacing it with Hope was documented in a BBC Television special, ''

The blue whale skeleton, Hope, that has replaced Dippy, is another prominent display in the museum. The display of the skeleton, some long and weighing 4.5 tonnes, was only made possible in 1934 with the building of the New Whale Hall (now the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery). The whale had been in storage for 42 years since its stranding on sandbanks at the mouth of Wexford Harbour, Ireland in March 1891 after being injured by whalers. At this time, it was first displayed in the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery, but now takes pride of place in the museum's Hintze Hall. Discussion of the idea of a life-sized model also began around 1934, and work was undertaken within the Whale Hall itself. Since taking a cast of such a large animal was deemed prohibitively expensive, scale models were used to meticulously piece the structure together. During construction, workmen left a trapdoor within the whale's stomach, which they would use for surreptitious cigarette breaks. Before the door was closed and sealed forever, some coins and a telephone directory were placed inside—this soon growing to an urban myth that a time capsule was left inside. The work was completed—entirely within the hall and in view of the public—in 1938. At the time it was the largest such model in the world, at in length. The construction details were later borrowed by several American museums, who scaled the plans further. The work involved in removing Dippy and replacing it with Hope was documented in a BBC Television special, ''Horizon

The horizon is the apparent line that separates the surface of a celestial body from its sky when viewed from the perspective of an observer on or near the surface of the relevant body. This line divides all viewing directions based on whether i ...

: Dippy and the Whale'', narrated by David Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and author. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Natural History Unit, the nine natural histor ...

, which was first broadcast on BBC Two

BBC Two is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network owned and operated by the BBC. It covers a wide range of subject matter, with a remit "to broadcast programmes of depth and substance" in contrast to the more mainstream an ...

on 13 July 2017, the day before Hope was unveiled for public display.

The Darwin Centre is host to Archie

Archie is a masculine given name, a diminutive of Archibald. It may refer to:

People Given name or nickname

*Archie Alexander (1888–1958), African-American mathematician, engineer and governor of the US Virgin Islands

* Archie Blake (mathematici ...

, an 8.62-metre-long giant squid taken alive in a fishing net near the Falkland Islands in 2004. The squid is not on general display, but stored in the large tank room in the basement of the Phase 1 building. It is possible for members of the public to visit and view non-exhibited items behind the scenes for a fee by booking onto one of the several Spirit Collection Tours offered daily. On arrival at the museum, the specimen was immediately frozen while preparations commenced for its permanent storage. Since few complete and reasonably fresh examples of the species exist, "wet storage" was chosen, leaving the squid undissected. A 9.45-metre acrylic tank was constructed (by the same team that provide tanks to Damien Hirst), and the body preserved using a mixture of formalin and saline solution.

The museum holds the remains and bones of the "River Thames whale

The River Thames whale, affectionately nicknamed Willy by Londoners, was a juvenile female northern bottlenose whale which was discovered swimming in the River Thames in central London on Friday 20 January 2006. According to the BBC, she was fi ...

", a northern bottlenose whale that lost its way on 20 January 2006 and swam into the Thames. Although primarily used for research purposes, and held at the museum's storage site at Wandsworth.

Dinocochlea

''Dinocochlea ingens'' is a trace fossil specimen held in the Natural History Museum of London. It is a symmetrical helicospiral several metres in length that was famously unexplained until shown in 2009 to be a concretion formed around the burr ...

, one of the longer-standing mysteries of paleontology (originally thought to be a giant gastropod shell, then a coprolite, and now a concretion of a worm's tunnel), has been part of the collection since its discovery in 1921.

The museum keeps a wildlife garden on its west lawn, on which a potentially new species of insect resembling Arocatus roeselii

''Arocatus roeselii'' is a species of lygaeid bug.

Distribution

This species can be found in most of Europe, in the Middle East and Caucasus. It is not present in the British isles.

In 2008, it was reported in large numbers in London by the Na ...

was discovered in 2007.

Galleries

The museum is divided into four sets of galleries, or zones, each colour coded to follow a broad theme.Red Zone

This is the zone that can be entered from Exhibition Road, on the East side of the building. It is a gallery themed around the changing history of the Earth.

''Earth's Treasury'' shows specimens of rocks, minerals and gemstones behind glass in a dimly lit gallery. ''Lasting Impressions'' is a small gallery containing specimens of rocks, plants and minerals, of which most can be touched.

* Earth Hall ('' Stegosaurus'' skeleton)

* Human Evolution

* Earth's Treasury

* Lasting Impressions

* Restless Surface

* From the Beginning

* Volcanoes and Earthquakes

* The Waterhouse Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

This is the zone that can be entered from Exhibition Road, on the East side of the building. It is a gallery themed around the changing history of the Earth.

''Earth's Treasury'' shows specimens of rocks, minerals and gemstones behind glass in a dimly lit gallery. ''Lasting Impressions'' is a small gallery containing specimens of rocks, plants and minerals, of which most can be touched.

* Earth Hall ('' Stegosaurus'' skeleton)

* Human Evolution

* Earth's Treasury

* Lasting Impressions

* Restless Surface

* From the Beginning

* Volcanoes and Earthquakes

* The Waterhouse Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

Green zone

Blue zone

To the left of the Hintze Hall, this zone explores the diversity of life on the planet.

* Dinosaurs

* Fish, Amphibians and Reptiles

* Human Biology

* Images of Nature

* The Jerwood Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

* Marine Invertebrates

* Mammals

* Mammals Hall ( blue whale model)

* Treasures in the Cadogan Gallery

To the left of the Hintze Hall, this zone explores the diversity of life on the planet.

* Dinosaurs

* Fish, Amphibians and Reptiles

* Human Biology

* Images of Nature

* The Jerwood Gallery (temporary exhibition space)

* Marine Invertebrates

* Mammals

* Mammals Hall ( blue whale model)

* Treasures in the Cadogan Gallery

Orange zone

Enables the public to see science at work and also provides spaces for relaxation and contemplation. Accessible from Queens Gate.

* Wildlife Garden

* Darwin Centre

* Zoology Spirit Building

Enables the public to see science at work and also provides spaces for relaxation and contemplation. Accessible from Queens Gate.

* Wildlife Garden

* Darwin Centre

* Zoology Spirit Building

Highlights of the collection

* Otumpa iron meteorite weighing , found in 1783 inCampo del Cielo

Campo del Cielo refers to a group of iron meteorites and the area in Argentina where they were found. The site straddles the provinces of Chaco and Santiago del Estero, located north-northwest of Buenos Aires, Argentina and approximately southwe ...

, Argentina

* Latrobe nugget

The Latrobe nugget is one of the largest clusters of cubic gold crystals known in the world and is kept at the Natural History Museum in London. The nugget weighs 717 grams. It was found at Mount McIvor, Victoria, Australia. It was raised on ...

, one of the largest known clusters of cubic gold crystals

* Apollo 16

Apollo 16 (April 1627, 1972) was the tenth crewed mission in the United States Apollo space program, administered by NASA, and the fifth and penultimate to land on the Moon. It was the second of Apollo's " J missions", with an extended sta ...

Moon rock sample collected in 1972

* Ostro

Ostro ( ca, Migjorn, hr, Oštro, el, Όστρια), or Austro, is a southerly wind in the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic. Its name is Italian, derived from the Latin name ''Anemoi#Auster, Auster'', which also meant a s ...

Stone, flawless blue topaz

Topaz is a silicate mineral of aluminium and fluorine with the chemical formula Al Si O( F, OH). It is used as a gemstone in jewelry and other adornments. Common topaz in its natural state is colorless, though trace element impurities can mak ...

gemstone weighing 9,381 carats, about , the largest of its kind in the world

* Aurora Pyramid of Hope

The Aurora Pyramid of Hope is a collection of 296 cut natural diamonds in a wide variety of colors, billed as "the most comprehensive natural color diamond collection in the world". It is owned by Aurora Gems, Inc., a diamond merchant specialisin ...

, a collection of 296 natural diamonds in a wide variety of colours

* First Iguanodon teeth ever discovered

* Dippy

Dippy is a composite ''Diplodocus'' skeleton in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the holotype of the species ''Diplodocus carnegii''. It is considered the most famous single dinosaur skeleton in the world, due to the numerous ...

, plaster cast replica of the fossilised bones of a Diplodocus carnegii skeleton

* Mantellisaurus and American mastodon skeletons

* Full-sized animatronic model of a Tyrannosaurus rex

* The most intact Stegosaurus fossil skeleton ever discovered (nicknamed Sophie)

* Large skull of a Triceratops

* First specimen of Archaeopteryx

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird''), is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek (''archaīos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" ...

ever discovered, one of only 12 found and generally accepted by palaeontologists to be the oldest known bird

* Rare dodo skeleton, reconstructed from bones over 1,000 years old

* Only surviving specimen of the Great Auk

The great auk (''Pinguinus impennis'') is a species of flightless alcid that became extinct in the mid-19th century. It was the only modern species in the genus ''Pinguinus''. It is not closely related to the birds now known as penguins, wh ...

from the British Isles, collected in 1813 from Papa Westray

Papa Westray () ( sco, Papa Westree), also known as Papay, is one of the Orkney Islands in Scotland, United Kingdom. The fertile soilKeay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) ''Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland''. London. HarperCollins. has long been a draw ...

in the Orkney Islands

* Broken Hill skull, Middle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Paleoli ...

cranium

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, the ...

now considered part of a Homo heidelbergensis, discovered in the mine of Broken Hill or Kabwe in Zambia

* Gibraltar 1

Gibraltar 1 is the specimen name of a Neanderthal skull, also known as the Gibraltar Skull found at Forbes' Quarry in Gibraltar and presented to the Gibraltar Scientific Society by its secretary, Lieutenant Edmund Henry Réné Flint on 3 March 18 ...

and Gibraltar 2

Gibraltar 2, also known as Devil's Tower Child, represented five skull fragments of a male Neanderthal child discovered in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. The discovery of the fossils at the Devil's Tower (Gibraltar), Devil's Tower Mo ...

, two Neanderthal skulls found at Forbes' Quarry in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

* Cross-section of 1,300-year-old giant sequoia, at the museum since 1893

* Rare copy of ''The Birds of America

''The Birds of America'' is a book by naturalist and painter John James Audubon, containing illustrations of a wide variety of birds of the United States. It was first published as a series in sections between 1827 and 1838, in Edinburgh and ...

'' by John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin; April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was an American self-trained artist, naturalist, and ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornithology turned into a plan to make a complete pictoria ...

, containing illustrations of a wide variety of birds from the United States

* Rare first edition of Charles Darwin's '' On the Origin of Species''

Education and research

The museum runs a series of educational and public engagement programmes. These include for example a highly praised "How Science Works" hands on workshop for school students demonstrating the use of microfossils in geological research. The museum also played a major role in securing designation of the Jurassic Coast of Devon and Dorset as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has subsequently been a lead partner in the Lyme Regis Fossil Festivals.

In 2005, the museum launched a project to develop notable gallery characters to patrol display cases, including 'facsimiles' of Carl Linnaeus, Mary Anning, Dorothea Bate and William Smith. They tell stories and anecdotes of their lives and discoveries and aim to surprise visitors.

In 2010, a six-part BBC documentary series was filmed at the museum entitled ''

The museum runs a series of educational and public engagement programmes. These include for example a highly praised "How Science Works" hands on workshop for school students demonstrating the use of microfossils in geological research. The museum also played a major role in securing designation of the Jurassic Coast of Devon and Dorset as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has subsequently been a lead partner in the Lyme Regis Fossil Festivals.

In 2005, the museum launched a project to develop notable gallery characters to patrol display cases, including 'facsimiles' of Carl Linnaeus, Mary Anning, Dorothea Bate and William Smith. They tell stories and anecdotes of their lives and discoveries and aim to surprise visitors.

In 2010, a six-part BBC documentary series was filmed at the museum entitled ''Museum of Life

The Museum of Life is located at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Location

The museum is located on the campus of Oswaldo Cruz Foundation

The Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Portuguese ''Fundação Oswaldo Cruz'', also known a ...

'' exploring the history and behind the scenes aspects of the museum.

Since May 2001, the Natural History Museum admission has been free for some events and permanent exhibitions. However, there are certain temporary exhibits and shows that require a fee.

The Natural History museum combines the museum's life and earth science collections with specialist expertise in "taxonomy, systematics, biodiversity, natural resources, planetary science, evolution and informatics" to tackle scientific questions.

In 2011, the museum led the setting up of an International Union for Conservation of Nature Bumblebee Specialist Group, chaired by Dr. Paul H. Williams, to assess the threat status of bumblebee species worldwide using Red List criteria.

Access

The closest London Underground station is South Kensington — there is a tunnel from the station that emerges close to the entrances of all three museums. Admission is free, though there are donation boxes in the foyer.Museum Lane

Museum Lane runs between two of London's leading museums in South Kensington, namely the Science Museum to the north and the Natural History Museum (formerly the Geological Museum) to the south. It runs to the west off Exhibition Road through ...

immediately to the north provides disabled access

Accessibility is the design of products, devices, services, vehicles, or environments so as to be usable by people with disabilities. The concept of accessible design and practice of accessible development ensures both "direct access" (i.e ...

to the museum.

A connecting bridge between the Natural History and Science museums closed to the public in the late 1990s.

In popular culture

The museum plays an important role in the 1975 London-based Disney live-action feature '' One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing''; the eponymous skeleton is stolen from the museum, and a group of intrepid nannies hide inside the mouth of the museum's blue whale model (in fact a specially created prop – the nannies peer out from behind the whale's teeth, but a blue whale is abaleen whale

Baleen whales (systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their ...

and has no teeth). Additionally, the film is set in the 1920s, before the blue whale model was built.

The museum features as a base for Prodigium, a secret society

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

which studies and fights monsters, first appearing on '.

In the 2014 film '' Paddington'', Millicent Clyde is a devious and trecherous taxidermist at the museum. She kidnaps Paddington, intending to kill and stuff him, but is thwarted by the Brown family after scenes involving chases inside and on the roof of the building.

The museum features prominently in the level Lud's Gate from Tomb Raider III

''Tomb Raider III: Adventures of Lara Croft'' is an action-adventure video game developed by Core Design and published by Eidos Interactive. It was released for the PlayStation and Microsoft Windows platforms in 1998. ''Tomb Raider III'' is th ...

, with Core Design launching the game with Jonathan Ross

Jonathan Stephen Ross (born 17 November 1960) is an English broadcaster, film critic, comedian, actor, writer, and producer. He presented the BBC One chat show ''Friday Night with Jonathan Ross'' during the 2000s, hosted his own radio show on ...

at the museum on 15 October 1998.

Andy Day

Andy Day (born 15 May 1981) is an English actor, comedian, singer, dancer, songwriter and television presenter. He is best known for his work on the BBC's CBeebies channel. He is also a patron of Anti-Bullying Week.

He was first on Friendly T ...

's CBeebies shows, ''Andy's Dinosaur Adventures'' and ''Andy's Prehistoric Adventures'' are filmed in the Natural History Museum.

The museum was site of the first Pit Stop on ''The Amazing Race 33

''The Amazing Race 33'' is the thirty-third season of the American reality television show ''The Amazing Race''. It featured eleven teams of two competing in a race around the world.

Though filming initially started in February 2020, the COVID-1 ...

''.

Natural History Museum at Tring

The NHM also has an outpost in Tring,Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

, built by local eccentric Lionel Walter Rothschild. The NHM took ownership in 1938. In 2007, the museum announced that the name would be changed to the Natural History Museum at Tring, though the older name, the Walter Rothschild Zoological Museum, is still in widespread use.

See also

* James John Joicey *Keeper of Entomology, Natural History Museum {{Use dmy dates, date=April 2022

The Keeper of Entomology was an entomological academic position within the Natural History Museum, London. The Keeper of Entomology served as the head of the Department of Entomology within the Museum. Originally, t ...

* Sophie the Stegosaurus

''Stegosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of herbivorous, four-legged, armored dinosaur from the Late Jurassic, characterized by the distinctive kite-shaped upright plates along their backs and spikes on their tails. Fossils of the genus have been foun ...

* :Employees of the Natural History Museum, London

References

Bibliography

* ''Dr Martin Lister: Abibliography

Bibliography (from and ), as a discipline, is traditionally the academic study of books as physical, cultural objects; in this sense, it is also known as bibliology (from ). English author and bibliographer John Carter describes ''bibliography ...

'' by Geoffrey Keynes. St Paul's Bibliographies (UK). . (Includes illustrations by Lister's wife and daughter).

* ''The Travelling Naturalists'' (1985) by Clare Lloyd. (Study of 18th Century Natural History — includes Charles Waterton, John Hanning Speke, Henry Seebohm

Henry Seebohm (12 July 1832 – 26 November 1895) was an English steel manufacturer, and amateur ornithologist, oologist and traveller.

Biography

Henry was the oldest son of Benjamin Seebohm (1798–1871) who was a wool merchant at Horton Gra ...

and Mary Kingsley). Contains colour and black and white reproductions. Croom Helm (UK). .

* ''Dry storeroom no 1: The Secret Life of the Natural History Museum'' (2009) by Richard Fortey. HarperPress (UK). .

External links

*Picture Library of the Natural History Museum

The Natural History Museum on Google Cultural Institute

Architectural history and description

from the '' Survey of London''

Architecture and history of the NHM

from the Royal Institute of British Architects * Maps of

Nature News article on proposed cuts, June 2010

{{Authority control British Museum Natural history museums in London Museums sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Grade I listed buildings in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Grade I listed museum buildings Cultural infrastructure completed in 1880 Alfred Waterhouse buildings Non-departmental public bodies of the United Kingdom government Exempt charities Charities based in London Museums in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Romanesque Revival architecture in England Terracotta Museums established in 1881 1881 establishments in England National museums of England Dinosaur museums Natural History Museum, London South Kensington