Myrtle Hill Cemetery on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Myrtle Hill Cemetery is the second oldest cemetery in the city of

Evidence of the battle was found in the form of Cherokee bones and relics in the

Evidence of the battle was found in the form of Cherokee bones and relics in the

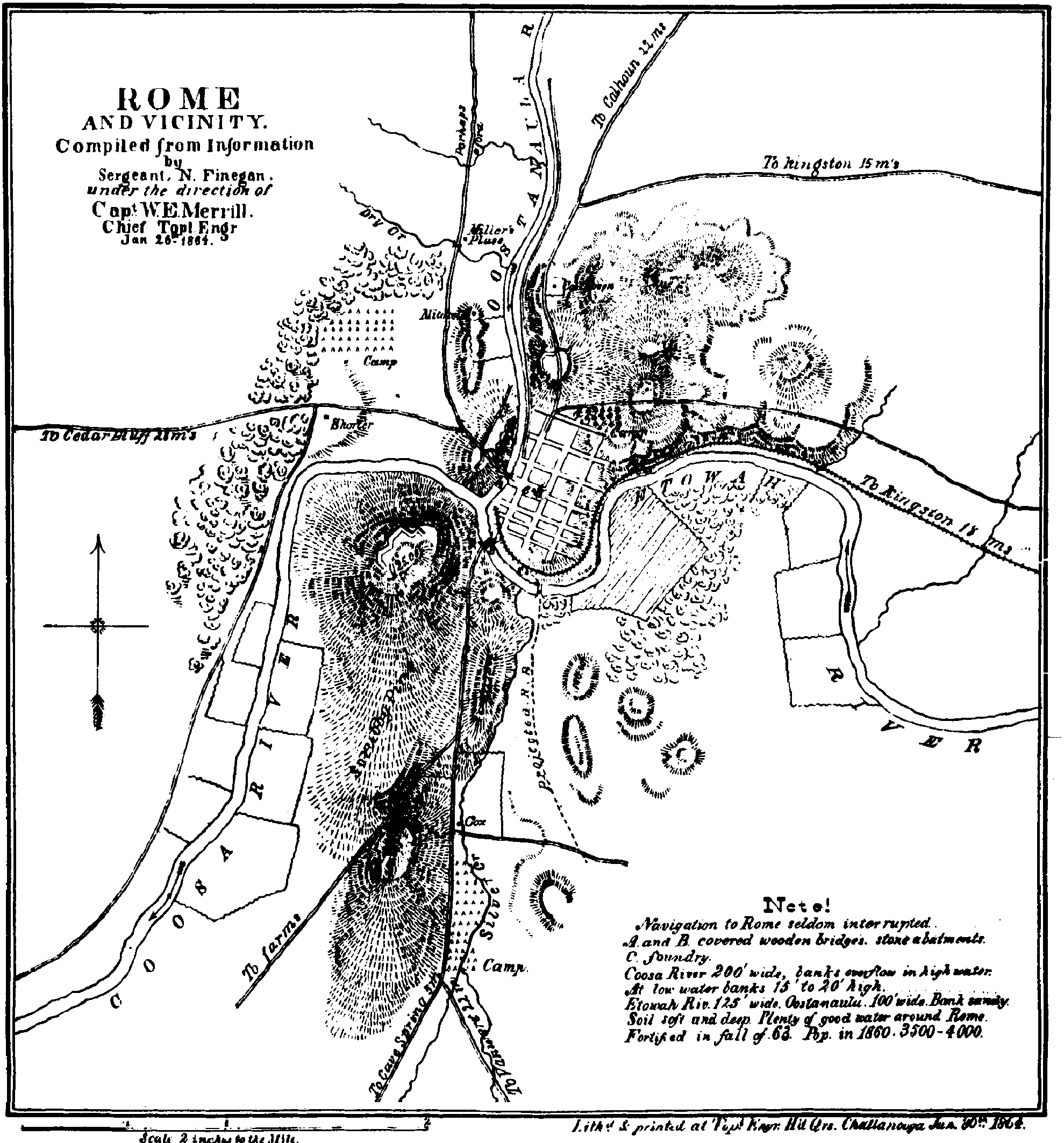

The exact location of the earthworks of Fort Stovall is impossible to determine from a Civil War era "map", and no evidence of it can be seen in the cemetery. Defensive lines constructed on a hill were typically built below the very top of the hill to prevent the occupants of the line from being silhouetted against the sky and giving the enemy a better target. It also gave the soldiers a clearer line of sight down the slope of the hill. The extensive terracing necessary for burials at Myrtle Hill has eliminated any evidence of Fort Stovall on the surface. It is possible, although unlikely, that remnants of the

The exact location of the earthworks of Fort Stovall is impossible to determine from a Civil War era "map", and no evidence of it can be seen in the cemetery. Defensive lines constructed on a hill were typically built below the very top of the hill to prevent the occupants of the line from being silhouetted against the sky and giving the enemy a better target. It also gave the soldiers a clearer line of sight down the slope of the hill. The extensive terracing necessary for burials at Myrtle Hill has eliminated any evidence of Fort Stovall on the surface. It is possible, although unlikely, that remnants of the

Georgia-Virginia football game

and Rosalind Gammon (died 1904), Gammon's mother who saved a football from being illegal in the state of Georgia. The Confederate Soldier statue on top of Myrtle Hill is known as "The Monument to the Confederate Dead of Rome and Floyd County in the Civil War" and was placed by the local chapter of the

This section contains over 377 Confederate and Union soldiers including 85 Unknown Union and/or Confederate Soldiers [Ref: A History of Rome and Floyd County, Battey, pp. 622 and see also Rome and Floyd County: An Illustrated History, Sesquicentennial Edition, 1985, pp 39. The first reference states that the Unknown graves are Confederate, while the second source states that the unknown graves are Union. More definitive information is needed for clarification]. They lost their lives in the battles of the American Civil War from Rome and other places. Dr. Samuel H. Stout, the physician in charge of all the hospitals that served the Army of Tennessee, ordered that all permanently disabled patients be sent to Rome. Many are buried in this section. The buildings and churches that were used as hospitals for the fallen soldiers were spared from General

This section contains over 377 Confederate and Union soldiers including 85 Unknown Union and/or Confederate Soldiers [Ref: A History of Rome and Floyd County, Battey, pp. 622 and see also Rome and Floyd County: An Illustrated History, Sesquicentennial Edition, 1985, pp 39. The first reference states that the Unknown graves are Confederate, while the second source states that the unknown graves are Union. More definitive information is needed for clarification]. They lost their lives in the battles of the American Civil War from Rome and other places. Dr. Samuel H. Stout, the physician in charge of all the hospitals that served the Army of Tennessee, ordered that all permanently disabled patients be sent to Rome. Many are buried in this section. The buildings and churches that were used as hospitals for the fallen soldiers were spared from General

Veteran's Plaza is a bricked site located at the corner of South Broad Street and Myrtle Street. The centerpiece of the plaza is the grave of America's Known Soldier, Charles Graves, 1904 water-cooled automatic machine guns around Graves' grave, and bronze replica of a World War

Veteran's Plaza is a bricked site located at the corner of South Broad Street and Myrtle Street. The centerpiece of the plaza is the grave of America's Known Soldier, Charles Graves, 1904 water-cooled automatic machine guns around Graves' grave, and bronze replica of a World War

The Tomb of the Known Soldier is the grave of Private Charles W. Graves (1893–1918). Private Graves was an

The Tomb of the Known Soldier is the grave of Private Charles W. Graves (1893–1918). Private Graves was an

The only U.S. First Lady buried in Georgia is buried in Myrtle Hill Cemetery.

The only U.S. First Lady buried in Georgia is buried in Myrtle Hill Cemetery.

Stockton Axson

Stockton Axson

Secretary of the American Red Cross in World War I. * Dr. Robert M. Battey, who performed the first bilateral oophorectomy as known as Battey's Operation. * Nathan Henry Bass Sr., Civil War Confederate Congressman. * Thomas and Frances Rhea Berry,

City of Rome, GA - Myrtle Hill Cemetery

Georgia's Rome Tourism - Myrtle Hill Cemetery

Myrtle Hill Cemetery grave list

Myrtle Hill Cemetery at ''Find a Grave''

{{Authority control Rome, Georgia Cemeteries on the National Register of Historic Places in Georgia (U.S. state) Protected areas of Floyd County, Georgia National Register of Historic Places in Floyd County, Georgia 1857 establishments in Georgia (U.S. state)

Rome, Georgia

Rome is the largest city in and the county seat of Floyd County, Georgia, United States. Located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, it is the principal city of the Rome, Georgia metropolitan area, Rome, Georgia, metropolitan statisti ...

. The cemetery is at the confluence of the Etowah River

The Etowah River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 27, 2011 waterway that rises northwest of Dahlonega, Georgia, north of Atlanta. On Matthew Carey's 1795 ...

and Oostanaula River

The Oostanaula River (pronounced "oo-stuh-NA-luh") is a principal tributary of the Coosa River, about long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 27, 2011 formed by the ...

and to the south of downtown Rome across the South Broad Street bridge.

Geography

Three of Rome's seven hills were chosen as burial grounds - Lumpkin Hill, Myrtle Hill, and Mount Aventine because of the flooding of Rome's three rivers - Etowah, Oostanaula and Coosa. Myrtle Hill was named for its ''Vinca minor

''Vinca minor'' (common names lesser periwinkle or dwarf periwinkle) is a species of flowering plant in the dogbane family, native to central and southern Europe, from Portugal and France north to the Netherlands and the Baltic States, east to ...

'' (trailing myrtle) on the hill

A hill is a landform that extends above the surrounding terrain. It often has a distinct Summit (topography), summit.

Terminology

The distinction between a hill and a mountain is unclear and largely subjective, but a hill is universally con ...

. The cemetery covers on 6 terraces and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

.

Myrtle Hill cemetery is the final resting place of more than 20,000 people including doctors, politicians, football heroes, soldiers including America's Known Soldier, a First Lady of the United States, and Rome's founders.

"Where Romans Rest" is an annual tour of Myrtle Hill Cemetery, given by the Greater Rome Convention & Visitors Bureau.

History

Battle of Hightower

Before becoming a cemetery, the hill gained notability as an 18th-century battle site. In September 1793, GeneralJohn Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

, in command of 800 men, came to the area on an unauthorized mission. Sevier was pursuing 1,000 Cherokees who had scalped and killed thirteen settlers at Cavett's Station, near Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state's ...

. The pursuit ended in Georgia, when Sevier caught up with the Cherokee at the village of what he called Hightower (Etowah, or Itawayi), which is near the present-day site of Cartersville, Georgia

Cartersville is a city in Bartow County, Georgia, United States; it is located within the northwest edge of the Atlanta metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 23,187. Cartersville is the county seat of Bartow Coun ...

. The Cherokee created a defensive position on Myrtle Hill and used a guard to try to prevent Sevier from fording the rivers.

Sevier left a written account of the battle, in which he described an attempt to cross the Etowah River about a mile south of Myrtle Hill, drawing the Cherokee defenders out of their prepared positions, then galloping back to Myrtle Hill to cross there. The Cherokee rushed back to contest the crossing of the Etowah, but failed. When the Cherokee leader, Kingfisher, was killed, the remaining warriors fled, and Sevier burned the village.

Evidence of the battle was found in the form of Cherokee bones and relics in the

Evidence of the battle was found in the form of Cherokee bones and relics in the crevasses

A crevasse is a deep crack, that forms in a glacier or ice sheet that can be a few inches across to over 40 feet. Crevasses form as a result of the movement and resulting stress associated with the shear stress generated when two semi-rigid pie ...

of the hill. In 1901, the Xavier chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' efforts towards independence.

A non-profit group, they promote ...

erected a stone monument to Sevier which describes the battle to honor Sevier and the battle. The monument is located between Myrtle Hill Cemetery and the Etowah River by the South Broad Street bridge.

Cemetery Named Myrtle Hill

After the Battle of Hightower, the hill was largely undisturbed until white settlers came to western Georgia in search of gold. TheDahlonega, Georgia

The city of Dahlonega () is the county seat of Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242, and in 2018 the population was estimated to be 6,884.

Dahlonega is located at the north end of ...

gold discovery (gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

) of 1829 brought prospectors and settlers into the area of present-day Rome. The Indian Removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

, or Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

, which took place between 1830 and 1838, forced the Cherokee to abandon their holdings in the area. The former Cherokee territory was then allotted to white settlers. The city of Rome, founded in 1834 by Colonel Daniel R. Mitchell, Colonel Zachariah Hargrove, Major Phillip Hemphill

Rome is the largest city in and the county seat of Floyd County, Georgia, United States. Located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, it is the principal city of the Rome, Georgia, metropolitan statistical area, which encompasses all ...

, Colonel William Smith, and John Lumpkin, established Oak Hill (opened in 1837) as Rome's first cemetery. Thirteen years later, when Oak Hill Cemetery was nearly out of lots, the need for a second cemetery became apparent.

In 1850, after considering several properties, Colonel Thomas A. Alexander and Daniel S. Printup chose a hill near the rivers. The hill was originally owned by Colonel Alfred Shorter and Cunningham Pennington, a civil engineer. ''Rome Female College'' was later renamed Shorter University

Shorter University is a private Baptist university in Rome, Georgia. It was founded in 1873 and offers undergraduate and graduate degrees through six colleges and schools. In addition Shorter operates the Robert H. Ledbetter College of Busines ...

in honor of the Colonel and his wife Martha. Pennington designed the plan for the interments on six levels of the steep terrain as a 19th-century picturesque rural cemetery

A rural cemetery or garden cemetery is a style of cemetery that became popular in the United States and Europe in the mid-nineteenth century due to the overcrowding and health concerns of urban cemeteries. They were typically built one to five ...

. Roads circle the hill and combine with the necessary terracing to create a layered, "wedding cake" look. The new cemetery was opened in 1857 as Myrtle Hill Cemetery. "Myrtle" was chosen because of the myrtle (vinca minor) or "Flower of Death" that grew wild over the hill. The original Cemetery of was at the top of the hill. One of the first graves was of John Billups who died in 1857.

Fort Stovall

On July 14, 1863, the citizens of Rome allocated $3,000 to construct threeearthen

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former term ...

forts to defend Rome from the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

Army during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. The forts were completed in October 1863, as Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

soldiers began to take up duties in the new fortifications. As anticipated, Union raiders made forays into the area. Their focus was to cripple the Confederate war machine by destroying the Noble Foundry, located in the city on the Etowah River across from the cemetery. One of the forts, constructed on the crest of Myrtle Hill, was named ''Fort Stovall'' in honor of fallen Confederate soldier, George Stovall. Other forts, ''Fort Attaway'' (named for Thomas Attaway) and ''Fort Norton'' (named for Charles Norton), were opposite the location of Fort Stovall. It was described as a bracket-shaped linear earthwork near the top of Myrtle Hill as shown on the map. Its line faced northwest, defending the western approach to Rome as well as the Coosa River. It was made with several faces, which provided maximum coverage along its front. The zigzag

A zigzag is a pattern made up of small corners at variable angles, though constant within the zigzag, tracing a path between two parallel lines; it can be described as both jagged and fairly regular.

In geometry, this pattern is described as a ...

shape permitted defenders to direct enfilading

Enfilade and defilade are concepts in military tactics used to describe a military formation's exposure to enemy fire. A formation or position is "in enfilade" if weapon fire can be directed along its longest axis. A unit or position is "in de ...

(from the side) fire on any men who approached the line.

earthworks

Earthworks may refer to:

Construction

*Earthworks (archaeology), human-made constructions that modify the land contour

* Earthworks (engineering), civil engineering works created by moving or processing quantities of soil

*Earthworks (military), m ...

survive as subsurface features. While it is clear that subsequent earth-moving activities at Myrtle Hill affected the Civil War earthworks, it is also likely the Civil War action resulted in damage to the cemetery. The top of the monument on Billups' grave, which dates to 1857, is believed to have been shot off by a musket ball

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

during the war, but no other specific mention is made of damage to the graves. However, because of the excellent vantage point provided by the hill, there was likely considerable activity at the fort, as a point of origin for Confederate scouting and raiding parties. While the exact location of Fort Stovall is unclear, three sites are considered likely; the crest of the hill, where a Confederate soldier statue now stands, the Axson family homesite, or the hillside nearest the Etowah river.

On May 17, 1864, Confederate units defended Rome, including Fort Stovall, when Union General Jefferson C. Davis

Jefferson Columbus Davis (March 2, 1828 – November 30, 1879) was a regular officer of the United States Army during the American Civil War, known for the similarity of his name to that of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and for his kil ...

, in command of the 2nd Division of Palmer's 14th Army Corps, Army of the Cumberland

The Army of the Cumberland was one of the principal Union armies in the Western Theater during the American Civil War. It was originally known as the Army of the Ohio.

History

The origin of the Army of the Cumberland dates back to the creation ...

, approached down the west side of the Oostanaula and took up a position opposite Rome and engaged with the Confederate pickets. On reaching this position, Davis received an order to return to the 14th Corps, but as he was already engaged with Confederates and suspected a weak defense, he determined to stay on and capture Rome. Davis' considerable force was held at bay overnight by a small garrison assisted by three brigades of Polk's Corps on their way from Mississippi to reinforce General Albert Sidney Johnston. Fort Stovall was occupied during this brief standoff, but the main point of Confederate artillery was on Shorter Hill on the west side of the Oostanaula. The next day, when the Union forces moved to capture Rome, the Confederates had retreated. After the Confederates retreated and left Rome, Union forces likely used the fort during their occupation of Rome.

Postbellum Myrtle Hill Cemetery

The cemetery was used for fallen soldiers from several Civil War battles. A number ofantebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ...

burials have been noted, and numerous interments had been made in the Confederate Cemetery section by 1863. Other graves were added during the Atlanta Campaign following the death of soldiers in Rome's hospitals. After 1872, more graves were added as some important people with roles in the founding of Rome were buried there. Daniel R. Mitchell (died 1876), one of the founders of Rome, Daniel S. Printup (died 1887), one of the men who selected this site of the cemetery, John H. Underwood (died 1888), a United States Representative before the Civil War, a two-term superior court judge, and lawyer in Rome, Colonel Alfred Shorter (died 1882), the former owner of the cemetery and namesake of Shorter University, Nathan Henry Bass Sr. (died 1890), Civil War Confederate Congressman, Augustus Romaldus Wright

Augustus Romaldus Wright (June 16, 1813 – March 31, 1891) was an American politician and lawyer, as well as a colonel in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Augustus Wright was born in Wrightsboro, Georgi ...

(died 1891) who served in U.S. Congress with Abraham Lincoln, Dr. Robert Battey (died 1895), who performed the first ovarian operation, Homer V. M. Miller (died 1896), 1886 U.S. Senate in 1886, first Democrat from Georgia, Richard Vonalbade Gammon (died 1897), the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

football player who died of the injuries he received in thGeorgia-Virginia football game

and Rosalind Gammon (died 1904), Gammon's mother who saved a football from being illegal in the state of Georgia. The Confederate Soldier statue on top of Myrtle Hill is known as "The Monument to the Confederate Dead of Rome and Floyd County in the Civil War" and was placed by the local chapter of the

Ladies' Memorial Association

A Ladies' Memorial Association (LMA) is a type of organization for women that sprang up all over the American South in the years after the American Civil War. Typically, these were organizations by and for women, whose goal was to raise monument ...

in 1869. The Ladies Memorial Association raised the $6,000 for the statue to be made. This was difficult during Reconstruction and the 1870 financial panics caused a delay in the placing of the statue; however, the statue's plan was complete in 1887 as the statue was dedicated. The statue still stands on top of the hill, "Crown Point". In 1874, Hines M. Smith made a new survey of the cemetery which defined what is called the Old Original cemetery. New numbers were assigned to the lots at that time. Some deeds after 1874 make reference to the old number as well as the new one. Boundaries of the Old Original cemetery are based on a copy of the Smith survey updated to 1901. Some of the lots on this map, especially in the western part of the cemetery, may have been added between 1874 and 1901. The 1901 survey indicates that the original road pattern within the cemetery was nearly identical to its configuration today. A short section of road in the south western part of the Old Original section was closed by 1901. Also, it is evident that in the western part of the Old Original cemetery, some of the original walkways between the lots were being filled in by that date. By the end of the 19th century, the popularity of lots had been sold out to people who purchased the additions for their plans. The additions had been created and completed by Branham about 1899 on the steep bluff facing the rivers on the north side of the Old Original cemetery, Terraces A-D were added from 1908 to 1928 to near Branham's, the New Front in around 1909, The triangle "Memorial Addition" at the corner of streets and the south boundary of the Old Original cemetery in 1923 for Charles Graves, "America's Known Soldier" "the designated representative of all the Known Dead of the Great War 1917-1918" by President Warren Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. ...

and the Congressional Record

The ''Congressional Record'' is the official record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress, published by the United States Government Publishing Office and issued when Congress is in session. The Congressional Record Inde ...

, Glover Vault, the New Front Terrace, and the Greystone in 1938. The lots also contains the Freedman (African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

) section set aside when the cemetery was segregated. One of the African Americans buried at Myrtle Hill in 1915 was Tom McClintock, who had worked as a Myrtle Hill Cemetery gravedigger for 42 years.

2017 Confederate Monument Vandalism

In December 2017, the Confederate monument atop Myrtle Hill was vandalized. The monument was initially an urn and was erected 1887 by the "Women of Rome" to honor the Confederate veterans of Rome. The urn was replaced by a statue of a soldier in 1909. In 2017, a vandal or vandals knocked off its hands and the rifle, along with bashing in its face. The vandal or vandals responsible were never apprehended.Confederate Cemetery

William Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

's November 1864 order of burning buildings on Broad Street. Most are still standing and are on the National Register of Historic Places. The section's graves were marked with painted wooden markers between 1863 and 1900. Sometime after 1900, their wooden markers were replaced with the present stone markers that still exist. The section is called the Confederate Section of the Cemetery, but is not limited to just soldiers from the Civil War. A few graves are those of soldiers from subsequent wars; and one woman, buried at the feet of her husband.

Veteran's Plaza

Veteran's Plaza is a bricked site located at the corner of South Broad Street and Myrtle Street. The centerpiece of the plaza is the grave of America's Known Soldier, Charles Graves, 1904 water-cooled automatic machine guns around Graves' grave, and bronze replica of a World War

Veteran's Plaza is a bricked site located at the corner of South Broad Street and Myrtle Street. The centerpiece of the plaza is the grave of America's Known Soldier, Charles Graves, 1904 water-cooled automatic machine guns around Graves' grave, and bronze replica of a World War doughboy

Doughboy was a popular nickname for the American infantryman during World War I. Though the origins of the term are not certain, the nickname was still in use as of the early 1940s. Examples include the 1942 song "Johnny Doughboy Found a Rose in ...

enhances this site. Before Veteran's Plaza was a bricked site, it was just a grassy field with Graves' grave, the three maxim guns that were in the different positions, and shrines as memorials from the 1930s to the present to fallen soldiers who were involved with other wars. In the beginning of the year 2000, Many of the bricks were placed by a brick mason named Leroy Minter. The plaza has more than 3,000 bricks engraved with the names and branch of service, to honor and memorialize military veterans and civilians for their services to America in war or peace throughout all of American history. E.

Confederate Monuments

Two notable Confederate monuments stand at the side corners of Veterans Plaza. They are the General Nathan Forrest Monument and the Women of the Confederacy Monument. These monuments were moved in 1952 from their original places on Broad Street at Second Avenue because they had become a traffic hazard. General Forrest's Monument was dedicated to honor him for saving Rome from ColonelAbel Streight

Abel Delos Streight (June 17, 1828 – May 27, 1892) was a peacetime lumber merchant and publisher, and was a Union Army colonel in the American Civil War. His command precipitated a notable cavalry raid in 1863, known as Streight's Raid. He ...

and his mule-equipped cavalry on their mission to capture Rome. Colonel Streight who was coming from Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

on May 3, 1863 was defeated by General Forrest with a small group of confederates serving with him. General Forrest had 425 men and Colonel Streight had 1,000 but Streight surrendered as his raid was caught (see Rome, Georgia#Civil war period). His monument was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

in 1909. Forrest's monument was rededicated by the Emma Sansom Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in a ceremony on Saturday, April 18, 2009 for the 100th anniversary of the first dedication of his monument. The Women of the Confederacy Monument honors Confederate women who served as nurses in Rome to care for Confederate and Union soldiers during the Civil War and mothers/wives who waited while their men fought. Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

wrote the inscription on the monument. This monument is believed to be the first monument in the world to honor the role of women in war.

Tomb of the Known Soldier

The Tomb of the Known Soldier is the grave of Private Charles W. Graves (1893–1918). Private Graves was an

The Tomb of the Known Soldier is the grave of Private Charles W. Graves (1893–1918). Private Graves was an infantryman

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marin ...

in the American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought alon ...

who fought in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. On October 5, 1918, Private Graves was killed by German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

shrapnel

Shrapnel may refer to:

Military

* Shrapnel shell, explosive artillery munitions, generally for anti-personnel use

* Shrapnel (fragment), a hard loose material

Popular culture

* ''Shrapnel'' (Radical Comics)

* ''Shrapnel'', a game by Adam C ...

on the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (German: , Siegfried Position) was a German defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to Laffaux, near Soissons on the Aisne. In 191 ...

. His mother received the telegram from the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

that informed her about Private Graves' death; however, his body was not returned to America until March 29, 1922 when they brought American soldiers' remains from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

aboard the troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

''Cambria'' to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. The U.S. Government had the idea of creating Unknown Soldier and ''Known Soldier'' in Arlington Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

to honor World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

soldiers. Private Graves was chosen for ''America's Known Soldier'' by a blindfolded sailor who picked Graves' name from American soldier remains list, but his mother objected to his burial at Arlington. The War Department wanted to give his body flag-draped coffin a parade on Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major and prominent thoroughfare in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It stretches north from Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village to West 143rd Street in Harlem. It is one of the most expensive shopping stre ...

, in New York with generals, admirals, and politicians before his mother buried Graves in the cemetery near Antioch Church on April 6, 1922. On September 22, 1923, Romans decided to relocate Private Graves' body from Antioch Cemetery to Myrtle Hill Cemetery as ''America's Known Soldier'' after his mother's death and his brother's agreement. Private Graves was buried a third and final time. On November 11, 1923, Armistice Day

Armistice Day, later known as Remembrance Day in the Commonwealth and Veterans Day in the United States, is commemorated every year on 11 November to mark Armistice of 11 November 1918, the armistice signed between the Allies of World War I a ...

, Private Graves and the other 33 young men from Floyd County who died in World War I were honored with three Maxim gun

The Maxim gun is a recoil-operated machine gun invented in 1884 by Hiram Stevens Maxim. It was the first fully automatic machine gun in the world.

The Maxim gun has been called "the weapon most associated with imperial conquest" by historian M ...

s and 34 magnolia trees.

Ellen Axson Wilson

The only U.S. First Lady buried in Georgia is buried in Myrtle Hill Cemetery.

The only U.S. First Lady buried in Georgia is buried in Myrtle Hill Cemetery. Ellen Axson Wilson

Ellen Louise Wilson (née Axson; May 15, 1860 – August 6, 1914) was the first wife of President Woodrow Wilson and the mother of their three daughters. Like her husband, she was a Southerner, as well as the daughter of a clergyman. She was ...

, was the first wife of President Woodrow Wilson. Ellen Louise Axson Wilson was the daughter of Reverend S. E. Axson, who was a Presbyterian minister and Margaret Hoyt Axson. She was born in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

but grew up in Rome. She graduated from the Rome Female College and later studied Art at the Students' Art League in New York. In the Spring of 1883, she met Woodrow Wilson, a young lawyer from Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

. They were married in 1885 and moved to Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania

Bryn Mawr, pronounced ,

from Welsh for big hill, is a census-designated place (CDP) located across three townships: Radnor Township and Haverford Township in Delaware County, and Lower Merion Township in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. It i ...

where Mr. Wilson taught at the newly formed Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College ( ; Welsh: ) is a women's liberal arts college in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Founded as a Quaker institution in 1885, Bryn Mawr is one of the Seven Sister colleges, a group of elite, historically women's colleges in the United St ...

. After Wilson became the president of Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

in 1902 and the governor of New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

in 1910, he became the U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

in 1912. Ellen was the First Lady who had a studio with a skylight

A skylight (sometimes called a rooflight) is a light-permitting structure or window, usually made of transparent or translucent glass, that forms all or part of the roof space of a building for daylighting and ventilation purposes.

History

Open ...

installed at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

in 1913, and found time for painting and the duties of hostess for the nation. With her health failing slowly from Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied b ...

(chronic nephritis), she died August 6, 1914. After her death, her body was taken to Rome by a train with five private cars for President Wilson. The procession, a two-horse drawn funeral carriage, from First Presbyterian Church to Myrtle Hill Cemetery passed down Broad Street, which was lined with Romans. As the graveside service began, rain began to fall as if the sky were weeping. Mrs. Wilson was buried with her father, her mother, and her brotherStockton Axson

Notable burials

Stockton Axson

Secretary of the American Red Cross in World War I. * Dr. Robert M. Battey, who performed the first bilateral oophorectomy as known as Battey's Operation. * Nathan Henry Bass Sr., Civil War Confederate Congressman. * Thomas and Frances Rhea Berry,

Martha Berry

Martha McChesney Berry (October 7, 1865 – February 27, 1942) was an American educator and the founder of Berry College in Rome, Georgia.

Early years

Martha McChesney Berry was the daughter of Capt. Thomas Berry, a veteran of the Mexican– ...

's parents.

* Confederate Cemetery, 377 Floyd County soldiers lost their lives in American Civil War.

* Richard Vonalbade Gammon, the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

football player.

* Rosalind Gammon, Gammon's mother who saved Georgia's football.

* Private Charles W. Graves, "Known Soldier".

* Dr. Robert Maxwell Harbin, one of Harbin Hospital (later Clinic in 1948) founders.

* Dr. William Pickens Harbin, one of Harbin Hospital (later Clinic in 1948) founders.

* Colonel Zachariah B. Hargove, one of Rome founders.

* Ethel Hillyer Harris, author.

* Henderson Lovelace Lanham

Henderson Lovelace Lanham (September 14, 1888 – November 10, 1957) was an American politician and lawyer.

Lanham was born in Rome, Georgia. He attended the University of Georgia in Athens where he was a member of the Sigma Chi fraternity and t ...

, US Congressman.

* Homer V. M. Miller, 1886 U.S. Senate, first Democrat from Georgia after Civil War.

* Colonel Daniel R. Mitchell, one of the founders of Rome.

* John W. Maddox, Civil War Veteran US Congressman.

* Julia Omberg, first Dr. Battey's oophorectomy patient.

* Colonel Cunningham M. Pennington, who designed the cemetery.

* Daniel S. Printup, who helped select the site of the cemetery.

* Colonel Alfred Shorter, Shorter University

Shorter University is a private Baptist university in Rome, Georgia. It was founded in 1873 and offers undergraduate and graduate degrees through six colleges and schools. In addition Shorter operates the Robert H. Ledbetter College of Busines ...

's namesake.

* John H. Underwood, a United States Representative, superior court judge.

* Ellen Axson Wilson

Ellen Louise Wilson (née Axson; May 15, 1860 – August 6, 1914) was the first wife of President Woodrow Wilson and the mother of their three daughters. Like her husband, she was a Southerner, as well as the daughter of a clergyman. She was ...

, first wife of President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

.

* Helen Woodrow Bones, cousin of President Woodrow Wilson, acting First Lady

* Augustus Romaldus Wright

Augustus Romaldus Wright (June 16, 1813 – March 31, 1891) was an American politician and lawyer, as well as a colonel in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Augustus Wright was born in Wrightsboro, Georgi ...

, who served in the U.S. Congress with Abraham Lincoln.

* Dale M. Stone Sr. - Played the "Mighty Mo" organ at the Fox Theatre in 1935Images of America: Fox Theatre p. 78 and was the Official Organist for the State of Georgia in the 1950s.

See also

*History of Rome, Georgia

The history of Rome, Georgia extends to thousands of years of human settlement by ancient Native Americans. Spanish explorers recorded reaching the area in the later 16th century, and European Americans of the United States founded the city named ...

* Cemeteries on the National Register of Historic Places

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite or graveyard is a place where the remains of dead people are buried or otherwise interred. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek , "sleeping place") implies that the land is specifically designated as a buri ...

Gallery

References

External links

City of Rome, GA - Myrtle Hill Cemetery

Georgia's Rome Tourism - Myrtle Hill Cemetery

Myrtle Hill Cemetery grave list

Myrtle Hill Cemetery at ''Find a Grave''

{{Authority control Rome, Georgia Cemeteries on the National Register of Historic Places in Georgia (U.S. state) Protected areas of Floyd County, Georgia National Register of Historic Places in Floyd County, Georgia 1857 establishments in Georgia (U.S. state)