Myles Keogh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Myles Walter Keogh (25 March 1840 – 25 June 1876) was an

Through Secretary Seward's intervention, the three were given Captains' rank and on 15 April assigned to the staff of Irish-born Brigadier General James Shields, whose forces were about to confront the Confederate army of

Through Secretary Seward's intervention, the three were given Captains' rank and on 15 April assigned to the staff of Irish-born Brigadier General James Shields, whose forces were about to confront the Confederate army of

The badly injured animal was found on the fatal battlefield, and nursed back to health as the 7th Cavalry's regimental mascot, which he remained until his death in 1890. This horse,

The badly injured animal was found on the fatal battlefield, and nursed back to health as the 7th Cavalry's regimental mascot, which he remained until his death in 1890. This horse,

Keogh Family Papers at the Autry National Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Keogh, Myles 1840 births 1876 deaths American Civil War prisoners of war American military personnel killed in the American Indian Wars American Roman Catholics Battle of the Little Bighorn Irish emigrants to the United States (before 1923) Irish soldiers in Italy Irish soldiers in the United States Army Knights of St. Gregory the Great People educated at St Mary's Knockbeg College People from County Carlow People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 Union Army officers United States Army officers

Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

soldier. He served in the armies of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

during the war for Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

in 1860, and was recruited into the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, serving as a cavalry officer, particularly under Brig. Gen. John Buford

John Buford, Jr. (March 4, 1826 – December 16, 1863) was a United States Army cavalry officer. He fought for the Union as a brigadier general during the American Civil War. Buford is best known for having played a major role in the first day o ...

during the Gettysburg Campaign and the three-day Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

. After the war, Keogh remained in the regular United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

as commander of I Troop of the 7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Ireland, Irish air "Garryowen (air), Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune.

The regiment participated i ...

under George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

during the Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

, until he was killed along with Custer and all five of the companies directly under Custer's command at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

in 1876.

Career

Myles Keogh was born in Orchard House,Leighlinbridge

Leighlinbridge (; ) is a small town on the River Barrow in County Carlow, Ireland. The N9 National primary route once passed through the village, which was by-passed in the 1980s. It now lies on the R705 regional road.

It covers the townla ...

, County Carlow

County Carlow ( ; ga, Contae Cheatharlach) is a county located in the South-East Region of Ireland, within the province of Leinster. Carlow is the second smallest and the third least populous of Ireland's 32 traditional counties. Carlow Cou ...

, on 25 March 1840. The farming carried out at Keogh's home place in Leighlinbridge was arable, barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley pr ...

being the main crop. This meant that the Keogh family were largely unaffected by the hunger and poverty that accompanied the Great Famine and ravaged the country between 1845 and 1850 – Keogh's childhood days. However, two, or possibly three, of Keogh's siblings did die young, apparently from typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

– a disease associated with the famine and an illness that Myles also suffered as a boy.

He attended the National School in Leighlinbridge where he was enrolled under the spelling 'Miles Kehoe'.''http://www.littlebighorn.info/Articles.htm" – "A Visit to Orchard", ''Kimber, Doyle 2008'' – "''At Classics''" was recorded as the reason for leaving in 1852. He was long thought to have attended St. Patrick's College in Carlow but that college has not found any proof of his attendance. It is possible that he attended St. Mary's Knockbeg College where, from 1847, young lay pupils from St. Patrick's were sent to be educated.

By 1860, a twenty-year-old Myles Keogh had volunteered, along with over one thousand of his countrymen, to rally to the defence of Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

following a call to arms by the Catholic clergy in Ireland. By August 1860, Keogh was appointed second lieutenant of his unit in the Battalion of St. Patrick, Papal Army under the command of General Christophe Léon Louis Juchault de Lamoricière Christophe may refer to:

People

* Christophe (given name), list of people with this name

* Christophe (singer) (1945–2020), French singer

* Cristophe (hairstylist) (born 1958), Belgian hairstylist

* Georges Colomb (1856–1945), French comic str ...

. He was posted at Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic S ...

, a central port city of Italy. The Papal forces were defeated in September in the Battle of Castelfidardo

The Battle of Castelfidardo took place on 18 September 1860 at Castelfidardo, a small town in the Marche region of Italy. It was fought between the Sardinian army – acting as the driving force in the war for Italian unification, against the P ...

, and Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic S ...

was surrounded. The soldiers, although having admirable defence, were forced to surrender and Keogh was imprisoned at Genoa. After his quick release by exchange, Keogh went to Rome and was invited to wear the spirited green uniforms of the Company of St. Patrick as a member of the Vatican Guard. During his service, the Holy See awarded him the Medaglia for gallantry – the Pro Petri Sede Medal – and also the Cross of a Knight of the Order of St. Gregory the Great

The Pontifical Equestrian Order of St. Gregory the Great ( la, Ordo Sancti Gregorii Magni; it, Ordine di San Gregorio Magno) was established on 1 September 1831, by Pope Gregory XVI, seven months after his election as Pope.

The order is one of ...

– Ordine di San Gregorio.''Myles Keogh: The Life and Legend of an "Irish Dragoon" in the Seventh Cavalry'', John P. Langellier, Kurt Hamilton Cox, Brian C. Pohanka, 1998, .

Now that the fighting was over and duties of the Vatican Guard were more mundane, Keogh saw little purpose in remaining at Rome. With civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

raging in America, Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senate, United States Senat ...

began seeking experienced European officers to serve the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

, and called upon a number of prominent clerics to assist in his endeavour. John Hughes, Archbishop of New York

The Archbishop of New York is the head of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, who is responsible for looking after its spiritual and administrative needs. As the archdiocese is the metropolitan bishop, metropolitan see of the ecclesiastic ...

, travelled to Italy to recruit veterans of the Papal War, and met with Keogh and his comrades. Thus in March 1862 Keogh resigned his commission in the Company of Saint Patrick, and with his senior officer – 30-year-old Daniel J. Keily of Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

– returned briefly to Ireland, then boarded the steamer "''Kangaroo''" bound from Liverpool to New York, where the vessel arrived 2 April. Another Papal comrade, Joseph O'Keeffe – 19-year-old nephew of the Bishop of Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

– met with Keogh and Keily in Washington.

Through Secretary Seward's intervention, the three were given Captains' rank and on 15 April assigned to the staff of Irish-born Brigadier General James Shields, whose forces were about to confront the Confederate army of

Through Secretary Seward's intervention, the three were given Captains' rank and on 15 April assigned to the staff of Irish-born Brigadier General James Shields, whose forces were about to confront the Confederate army of Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

. They notably confronted Jackson's army in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

at the Battle of Port Republic

The Battle of Port Republic was fought on June 9, 1862, in Rockingham County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War. Port Republic w ...

. Though the Union army was defeated Keogh's courage during his first engagement did not go unnoticed. George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

, the commander of the Potomac Army, was impressed with Keogh, describing the young Captain as ''"a most gentlemanlike man, of soldierly appearance,"'' whose ''"record had been remarkable for the short time he had been in the army."''''The Honor of Arms: A Biography of Myles W. Keogh'', Charles L. Convis, 1990, . On McClellan's request, Keogh was temporarily transferred to his personal staff. He was to be with 'Little Mac' for only a few months but served the General during the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

. After McClellan's removal from command in November 1862, the admirable traits identified in his first six months in the Union army came to the fore when he and his Papal comrade, Joseph O'Keeffe, were reassigned to General John Buford

John Buford, Jr. (March 4, 1826 – December 16, 1863) was a United States Army cavalry officer. He fought for the Union as a brigadier general during the American Civil War. Buford is best known for having played a major role in the first day o ...

's staff.''Son of the Morning Star

''Son of the Morning Star: Custer and the Little Big Horn'' is a nonfiction account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876, by novelist Evan S. Connell, published in 1984 by North Point Press. The book features extensive portraits ...

'', Evan S. Connell, 1984,

Although held in reserve with the rest of the Union cavalry for the winter of 1862 and during the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnsi ...

, Myles Keogh and O'Keeffe served Buford with obedience and gallantry during the Stoneman Raid in April 1863 and the battle on 9 June at Brandy Station, which was practically all cavalry. Buford's 1st Division of cavalry fought with distinction in June 1863 as they skirmished with their much vaunted Confederate foe, led by J.E.B. Stuart

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart (February 6, 1833May 12, 1864) was a United States Army officer from Virginia who became a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War. He was known to his friends as "Jeb,” from the initials of ...

in Loudoun County

Loudoun County () is in the northern part of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. In 2020, the census returned a population of 420,959, making it Virginia's third-most populous county. Loudoun County's seat is Leesburg. Loudoun C ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

– most notably at Upperville.

On 30 June, Buford, with Keogh by his side, rode into the small town of Gettysburg. Very soon, Buford realised that he was facing a superior force of rebels to his front and set about creating a defence against the Confederate advance. He was acutely aware of the importance of holding the tactically important high ground about Gettysburg and so he did, beginning one of the most iconic battles in American military history. His intelligent defensive troop alignments, coupled with the bravery and tenacity of his dismounted men, allowed the 1st Corps, under General John F. Reynolds, time to come up in support and thus maintain a Union foothold at strategically important positions. Despite Lee's barrage attack of 140 cannons and a final infantry attack on the third day of the battle, the Union army won a highly significant victory. The importance of Buford's leadership and tactical foresight on 1 July cannot be overstated in its contribution to this victory. Significantly, Myles Keogh received his first brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

for ''"gallant and meritorious services"'' during the battle and was promoted to the rank of major.

The battle was over and so were almost 8,000 men's lives with it. However this was a turning point in the war, and a turning point in Buford's health. Five further months of almost constant skirmishing with J.E.B. Stuart

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart (February 6, 1833May 12, 1864) was a United States Army officer from Virginia who became a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War. He was known to his friends as "Jeb,” from the initials of ...

's Rebel cavalry at such battles as Funkstown and Willamsport worsened Buford's condition. As Keogh later wrote in Buford's service record (etat de service), Buford ''"was taken ill from fatique and extreme hardship"''. By the winter Buford would succumb to typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

. Keogh would stay by his side and care for him, while they rested in Washington at the home of an old friend General George Stoneman

George Stoneman Jr. (August 8, 1822 – September 5, 1894) was a United States Army cavalry officer and politician who served as the fifteenth Governor of California from 1883 to 1887. He was trained at West Point, where his roommate was Stonewall ...

. Buford was buried at West Point Cemetery

West Point Cemetery is a historic cemetery in the eastern United States, on the grounds of the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York. It overlooks the Hudson River, and served as a burial ground for Revolutionary War soldiers and early ...

, as Keogh attended his funeral at Washington and rode with his body on the train.

Major Keogh was now appointed as aide de camp to General George Stoneman

George Stoneman Jr. (August 8, 1822 – September 5, 1894) was a United States Army cavalry officer and politician who served as the fifteenth Governor of California from 1883 to 1887. He was trained at West Point, where his roommate was Stonewall ...

. In July 1864, Stoneman raided to the south and southeast, destroying railroads and industrial works. Their risky raids behind Confederate lines were also designed to free federal prisoners held at Macon, Georgia

Macon ( ), officially Macon–Bibb County, is a consolidated city-county in the U.S. state of Georgia. Situated near the fall line of the Ocmulgee River, it is located southeast of Atlanta and lies near the geographic center of the state of Geo ...

, and liberate the nearly 30,000 captives at Andersonville prison.

Although Stoneman's Union cavalry did destroy the railroads, the onslaught on Macon failed from the beginning and on 31 July 1864, Keogh and Stoneman's command were surrounded during the Battle of Sunshine Church, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. They were captured after both their horses were shot out from under them. Keogh was held for 2½ months as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

before being released through Union general William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

's efforts. Keogh would later receive a second brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

with promotion to lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

for his gallantry with Stoneman at the Battle of Dallas

The Battle of Dallas (May 28, 1864) was an engagement during the Atlanta Campaign in the American Civil War. The Union army of William Tecumseh Sherman and the Confederate army led by Joseph E. Johnston fought a series of battles between May 25 ...

.

The praise garnered from the commanders Myles Keogh served with during the war years was indeed high:

At the war's end, brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

Lt. Colonel Keogh chose to remain on active duty and accepted a Regular Army commission as a second lieutenant in the 4th Cavalry on 4 May 1866. On 28 July 1866 he was promoted to Captain, and reassigned to the 7th Cavalry at Ft. Riley

Fort Riley is a United States Army military base, installation located in North Central Kansas, on the Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, between Junction City, Kansas, Junction City and Manhattan, Kansas, Manhattan. The Fort Riley Military Re ...

in Northeast Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

where he took command of Company I. The 7th Cavalry Regiment was first commanded by Colonel Andrew Smith (from 1866 to 1869) and subsequently by Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis (from 1869 to 1886). George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

was the regiment's Lieutenant Colonel and its deputy commander.

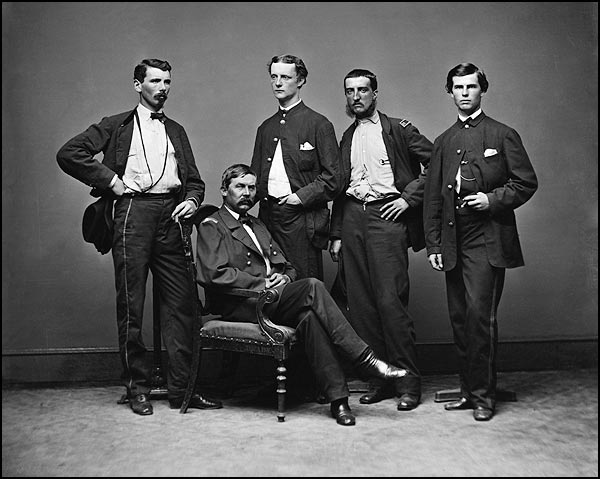

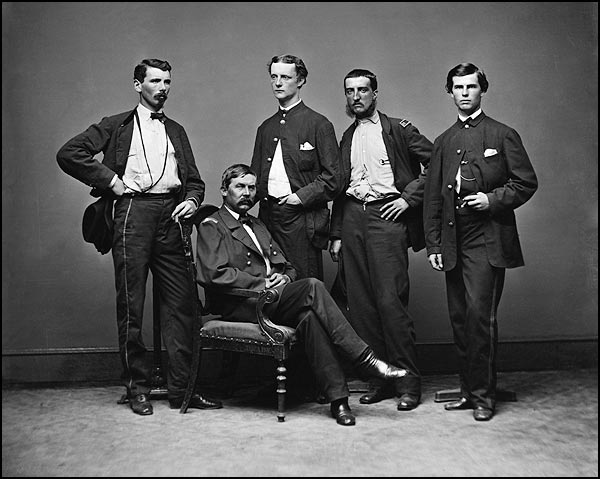

Postbellum career

Keogh was generally well liked by fellow officers although the isolation of military duty on the western frontier often weighed heavily upon him. When depressed he occasionally drank to excess, though he seems not to have fallen prey to the chronic alcoholism that destroyed the careers of many fellow officers of the frontier Regular Army. There was more than a tinge of melancholy in Keogh's nature, which seemed somehow at odds with his handsome, dashing persona. While he was not given to self-analysis, Keogh once noted: Keogh was also fond of the ladies, though he never married: He did, however, carry a photograph of Capt. Thomas McDougall's sister, Josephine Buel, with him to Little Bighorn. Although absent from theBattle of Washita River

The Battle of Washita River (also called Battle of the Washita or the Washita Massacre) occurred on November 27, 1868, when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer's 7th U.S. Cavalry attacked Black Kettle's Southern Cheyenne camp on the Washita Rive ...

(1868) and the Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

Expedition (1873), Custer's encounters of substance with hostile Indians, Keogh did have sole responsibility for defending the Smoky Hill route against Indian raids from late 1866 to the summer of 1867. When Sheridan took over from Hancock Hancock may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Hancock, Iowa

* Hancock, Maine

* Hancock, Maryland

* Hancock, Massachusetts

* Hancock, Michigan

* Hancock, Minnesota

* Hancock, Missouri

* Hancock, New Hampshire

** Hancock (CDP), New Hampshir ...

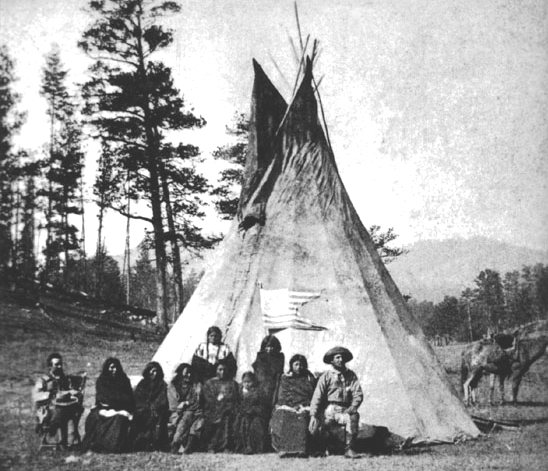

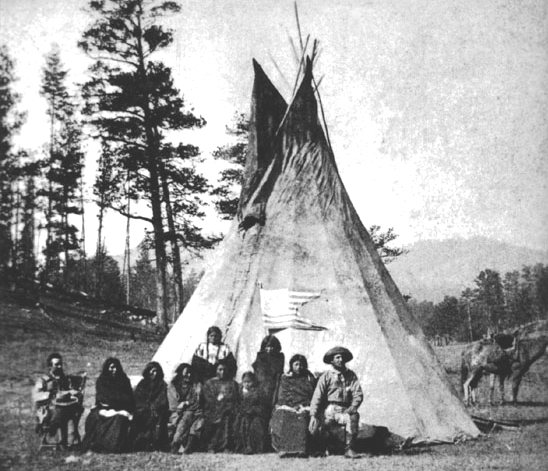

in 1868, there is evidence that it was to Keogh he turned for first-hand information on conditions on the front line. And while with Sully's expedition later that year, Keogh was fighting Indians almost every day—indeed, it was in one such fight that his new mount, Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in La ...

, received his first wound and, as the story goes, his name. Captain Keogh's frustration with an enemy who did not fight in a conventional manner is evident from a comment he wrote in a personal letter to his family in Ireland:

In the summer of 1874, Keogh was on leave to visit his homeland on a seven-month leave of absence, while Custer was leading a controversial expedition through the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black Elk P ...

. During this second visit home he deeded his inherited Clifden estate in Kilkenny

Kilkenny (). is a city in County Kilkenny, Ireland. It is located in the South-East Region and in the province of Leinster. It is built on both banks of the River Nore. The 2016 census gave the total population of Kilkenny as 26,512.

Kilken ...

to his sister Margaret. He enjoyed his stay in his homeland, feeling the necessity to support his sisters after the death of both parents.

In October, Keogh returned to Fort Abraham Lincoln

Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park is a North Dakota state park located south of Mandan, North Dakota, United States. The park is home to the replica Mandan On-A-Slant Indian Village and reconstructed military buildings including the Custer House.

...

for his old duty with Custer, and it would be his last days. As a precaution, he purchased a $10,000 life insurance policy and wrote a letter of warning to his close friends in the Throop-Martin family, Auburn, New York

Auburn is a city in Cayuga County, New York, United States. Located at the north end of Owasco Lake, one of the Finger Lakes in Central New York, the city had a population of 26,866 at the 2020 census. It is the largest city of Cayuga County, the ...

, outlining his burial wishes:

He gave out copies of his will to comrades, and left behind personal papers with instructions that they be burned if he was killed.

Keogh died during Custer's Last Stand – the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

on 25 June 1876. The senior captain among the five companies wiped out with Custer that day, and commanding one of two squadrons within the Custer detachment, Keogh died in a "last stand" of his own, surrounded by the men of Company I. When the sun-blackened and dismembered dead were buried three days later, Keogh's body was found at the center of a group of troopers that included his two sergeants, company trumpeter and guidon bearer. The slain officer was stripped but not mutilated, perhaps because of the "medicine" the Indians saw in the Agnus Dei

is the Latin name under which the " Lamb of God" is honoured within the Catholic Mass and other Christian liturgies descending from the Latin liturgical tradition. It is the name given to a specific prayer that occurs in these liturgies, and ...

("Lamb of God") he wore on a chain about his neck or because "many of Sitting Bull's warriors" were Catholic. Keogh's left knee had been shattered by a bullet that corresponded to a wound through the chest and flank of his horse, indicating that horse and rider may have fallen together prior to the last rally.

The badly injured animal was found on the fatal battlefield, and nursed back to health as the 7th Cavalry's regimental mascot, which he remained until his death in 1890. This horse,

The badly injured animal was found on the fatal battlefield, and nursed back to health as the 7th Cavalry's regimental mascot, which he remained until his death in 1890. This horse, Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in La ...

, is considered the only U.S. military survivor of the battle, though several other badly wounded horses were found and destroyed at the scene. Keogh's bloody gauntlet and the guidon of his Company I were recovered by the army three months after Little Bighorn at the Battle of Slim Buttes

The Battle of Slim Buttes was fought on September 9–10, 1876, in the Great Sioux Reservation between the United States Army and Miniconjou Sioux during the Great Sioux War of 1876. It marked the first significant victory for the army sinc ...

.

Originally buried on the battlefield, Keogh's remains were disinterred and taken to Auburn, as he had requested in his will. He was buried at Fort Hill Cemetery

Fort Hill Cemetery is a cemetery located in Auburn, New York, United States. It was incorporated on May 15, 1851 under its official name: "Trustees of the Fort Hill Cemetery Association of Auburn". It is known for its headstones of notable people ...

on 26 October 1877, an occasion marked by citywide official mourning and an impressive military procession to the cemetery.

Tongue River Cantonment

A cantonment (, , or ) is a military quarters. In Bangladesh, India and other parts of South Asia, a ''cantonment'' refers to a permanent military station (a term from the British India, colonial-era). In military of the United States, United Stat ...

, in southeastern Montana, was renamed after him to be Fort Keogh

Fort Keogh is a former United States Army post located at the western edge of modern Miles City, Montana, Miles City, in the U.S. state of Montana. It is situated on the south bank of the Yellowstone River, at the mouth of the Tongue River (Montan ...

. The fort was first commanded by Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the Spanish–American War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding Gen ...

. The 55,000-acre fort is today an agricultural experiment station. Miles City, Montana is located two miles from the old fort.

Funeral

''We extract from the Auburn papers the following accounts of the burial of the late Col. Myles W. Keogh, at Fort Hill Cemetery, Auburn, NY. 26 October: Promptly at 2pm the funeral procession moved from the St James Hotel, where the pallbearers had assembled, and marched in the following order: The Pall-Bearers; Auburn City Band; Military, Lt. Judge, commanding; Post Crocker, G.A.R.; Post Seward G.A.R.; Hearse, draped with the National colors; Carriages bearing the family of E. T. Throop Martin and Army officers. A detail from Post Seward fired minute guns during the march and the ceremonies at the grave. The flag at the State Armoury was flown at half-mast, as were numerous other flags about the city. Volunteers from the several Auburn organisations of the 49th NY Militia were formed into a company, charged with the duties of escort and firing party, according to military etiquette. At the receiving vault the casket was draped with the American flag, upon which were placed some beautiful floral designs. The bearers then placed the casket in the hearse and the line moved to the grave on the lot of E.T. Throop Martin Esq. The pall-bearers were Gen. W. H. Seward, Col. C.C. Dwight, Col. J. E. Storke, Col. E.D. Woodruff, Surgeon Theo. Dimon, Major L.E. Carpenter, Major W.G. Wise and Capt. W.M. Kirby. The following officers of the regular army were present: Gen. L.C. Hunt, Col. R.N. Scott, Surgeon R.N. O'Reilly, Gen. A. J. Alexander, Lieut. J.W. Martin. The grave was laid with evergreens and flowers, and at its head, the base of a handsome monument to be erected in memory of this dead soldier, was strewn with other floral tributes. The remains were lowered into the grave, when the solemn burial service was read by Rev. Dr. Brainard. A dirge was then executed by the band, after which three volleys of musketry were fired by the military, and the procession marched from the cemetery in the same order as on its entry, the immediate friends remaining until the grave was closed. The obsequies were most solemn and imposing, and in every way befitting the rank and record of the fallen brave in whose honour they were held.'' The prominent Throop-Martin family, with whom Keogh had become friendly after his comrade General A.J. Alexander married Evelina Martin, was responsible for his burial in their Fort Hill plot and the design of his monument. At the base of decorative, white obelisk there is an inscription taken from the poem, The Song of the Camp byBayard Taylor

Bayard Taylor (January 11, 1825December 19, 1878) was an American poet, literary critic, translator, travel author, and diplomat. As a poet, he was very popular, with a crowd of more than 4,000 attending a poetry reading once, which was a record ...

:

''"Sleep soldier still in honored rest, Your truth and valor wearing; The bravest are the tenderest, The loving are the daring."''

The marble cross atop his grave was added later at the request of his sister in Ireland.

U.S. military career and ranks

Appointed Captain, US Volunteers, 9 April 1862 Promoted Major, US Volunteers, 7 April 1864 Brevetted Lieutenant Colonel, US Volunteers, 13 March 1865 Honorably discharged from US Volunteers, 1 September 1866 Appointed Second Lieutenant, Regular Army, 4 May 1866 Promoted Captain, Regular Army, 28 July 1866 Killed in action, 25 June 1876.References

Further reading

* ''Son of the Morning Star

''Son of the Morning Star: Custer and the Little Big Horn'' is a nonfiction account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876, by novelist Evan S. Connell, published in 1984 by North Point Press. The book features extensive portraits ...

'', Evan S. Connell, 1984,

* ''Classic Battles: Little Big Horn 1876'', Peter Panzieri, 1995,

* ''Custer and His Commands'', Kurt Hamilton Cox, 1999,

* ''The Custer Autograph Album'', John M. Carroll, 1994,

* ''The Little Bighorn Campaign'', Wayne Michael Sarf, 1993,

* ''Myles Keogh: The Life and Legend of an "Irish Dragoon" in the Seventh Cavalry'', John P. Langellier, Kurt Hamilton Cox, Brian C. Pohanka, 1998,

* ''The Honor of Arms: A Biography of Myles W. Keogh'', Charles L. Convis, 1990,

* ''Custer's Fall'', David Humphreys Miller

David Humphreys Miller (June 8, 1918 – August 21, 1992) was an American artist, author, and film advisor who specialized in the culture of the northern Plains Indians. He was most notable for painting his 72 portraits of the survivors of the Bat ...

, Duell, Sloan and Pierce, Inc., 1957

* ''http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/opinion/2008/1003/1222959302719.html

External links

Keogh Family Papers at the Autry National Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Keogh, Myles 1840 births 1876 deaths American Civil War prisoners of war American military personnel killed in the American Indian Wars American Roman Catholics Battle of the Little Bighorn Irish emigrants to the United States (before 1923) Irish soldiers in Italy Irish soldiers in the United States Army Knights of St. Gregory the Great People educated at St Mary's Knockbeg College People from County Carlow People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 Union Army officers United States Army officers