Moonraker (novel) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Moonraker'' is the third novel by the British author Ian Fleming to feature his fictional British

Secret Service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For ...

agent James Bond

The ''James Bond'' series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have ...

. It was published by Jonathan Cape on 5 April 1955 and featured a cover design conceived by Fleming. The plot is derived from a Fleming screenplay that was too short for a full novel, so he added the passage of the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

game between Bond and the industrialist Hugo Drax

Sir Hugo Drax is a fictional character created by author Ian Fleming for the 1955 James Bond novel '' Moonraker''. For the later film and its novelization, Drax was greatly altered from the novel by screenwriter

A screenplay writer (also ...

. In the latter half of the novel, Bond is seconded to Drax's staff as the businessman builds the Moonraker, a prototype missile designed to defend England. Unknown to Bond, Drax is German, an ex-Nazi now working for the Soviets; his plan is to build the rocket, arm it with a nuclear warhead, and fire it at London. Uniquely for a Bond novel, ''Moonraker'' is set entirely in Britain, which raised comments from some readers, complaining about the lack of exotic locations.

''Moonraker'', like Fleming's previous novels, was well received by critics. It plays on several 1950s fears, including attack by rockets (following the V-2 strikes of the Second World War), nuclear annihilation, Soviet communism

The ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was Bolshevist Marxism–Leninism, an ideology of a centralised command economy with a vanguardist one-party state to realise the dictatorship of the proletariat. The Soviet Un ...

, the re-emergence of Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

and the "threat from within" posed by both ideologies. Fleming examines Englishness, and the novel shows the virtues and strength of England. Adaptations include a broadcast on South African radio in 1956 starring Bob Holness

Robert Wentworth John Holness (12 November 1928 – 6 January 2012) was a British-South African radio and television presenter and occasional actor. He presented the British version of '' Blockbusters''.

Early life

Holness was born in Vryheid, ...

and a 1958 '' Daily Express'' comic strip. The novel's name was used in 1979 for the eleventh official film in the Eon Productions

Eon Productions Ltd. is a British film production company that primarily produces the ''James Bond'' film series. The company is based in London's Piccadilly and also operates from Pinewood Studios in the UK.

''Bond'' films

Eon was started ...

Bond series and the fourth to star Roger Moore as Bond; the plot was significantly changed from the novel to include excursions into space.

Plot

The BritishSecret Service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For ...

agent James Bond

The ''James Bond'' series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have ...

is asked by his superior, M, to join him at M's club, Blades. A club member, the multi-millionaire businessman Sir Hugo Drax, is winning considerable money playing bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

, seemingly against the odds. M suspects Drax is cheating, and while claiming indifference, is concerned as to why a multi-millionaire and national hero would cheat. Bond confirms Drax's deception and manages to turn the tables—aided by a stacked deck of cards—and wins £15,000 () (more than seven times his own annual salary).

Drax is the product of a mysterious background, purportedly unknown even to himself. Presumed to have been a British Army soldier during the Second World War, he was badly injured and stricken with amnesia in the explosion of a bomb planted by a German saboteur at a British field headquarters. After extensive rehabilitation in an army hospital, he returned home to become a wealthy industrialist. After building his fortune and establishing himself in business and society, Drax started building the "Moonraker", Britain's first nuclear missile

Nuclear weapons delivery is the technology and systems used to place a nuclear weapon at the position of detonation, on or near its target. Several methods have been developed to carry out this task.

''Strategic'' nuclear weapons are used primari ...

project, intended to defend Britain against its Cold War enemies. The Moonraker rocket was to be an upgraded V-2 rocket

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develop ...

using liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen (LH2 or LH2) is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecular H2 form.

To exist as a liquid, H2 must be cooled below its critical point of 33 K. However, for it to be in a fully l ...

and fluorine as propellants

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or other motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicles, the e ...

; to withstand the ultra-high combustion temperatures of its engine, it used columbite

Columbite, also called niobite, niobite-tantalite and columbate [], is a black mineral group that is an ore of niobium. It has a submetallic Lustre (mineralogy), luster and a high density and is a niobate of iron and manganese. This mineral group ...

, in which Drax had a monopoly. Because the rocket's engine could withstand high heat, the Moonraker was able to use these powerful fuels, greatly expanding its effective range.

After a Ministry of Supply security officer working at the project is shot dead, M assigns Bond to replace him and also to investigate what has been going on at the missile-building base, located between Dover and Deal on the south coast of England. All the rocket scientists working on the project are German. At his post on the complex, Bond meets Gala Brand, a beautiful police Special Branch officer working undercover as Drax's personal assistant. Bond also uncovers clues concerning his predecessor's death, concluding that the man may have been killed for witnessing a submarine off the coast.

Drax's henchman Krebs is caught by Bond snooping through his room. Later, an attempted assassination by triggering a landslide nearly kills Bond and Brand, as they swim beneath the Dover cliffs. Drax takes Brand to London, where she discovers the truth about the Moonraker by comparing her own launch trajectory figures with those in a notebook picked from Drax's pocket. She is captured by Krebs, and finds herself captive in a secret radio homing station—intended to serve as a beacon for the missile's guidance system—in the heart of London. While Brand is being taken back to the Moonraker facility by Drax, Bond gives chase, but is also captured by Drax and Krebs.

Drax tells Bond that he was never a British soldier and has never suffered from amnesia: his real name is Graf

(feminine: ) is a historical title of the German nobility, usually translated as "count". Considered to be intermediate among noble ranks, the title is often treated as equivalent to the British title of "earl" (whose female version is "coun ...

Hugo von der Drache, the German commander of a Werwolf commando unit. Disguised in an Allied uniform, he was the saboteur whose team placed the car bomb at the army field headquarters, only to be injured himself in the detonation. The amnesia story was simply a cover he used while recovering in hospital to avoid recognition, although it would lead to a whole new British identity. Drax remains a dedicated Nazi, bent on revenge against England for the wartime defeat of his Fatherland and his prior history of social slights suffered as a youth growing up in an English boarding school before the war. He explains that he now means to destroy London, with a Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

-supplied nuclear warhead that has been secretly fitted to the Moonraker. His company is also selling the British pound short in order to make a huge profit from the disaster.

Brand and Bond are imprisoned where the blast from the Moonraker's engines will incinerate them, to leave no trace of them once the missile is launched. Before the launch, the couple escape. Brand gives Bond the coordinates he needs to redirect the gyros and send the Moonraker into the sea. Having been in collaboration with Soviet Intelligence all along, Drax and his henchman attempt to escape by Soviet submarine—only to be killed as the vessel makes its escape through the waters onto which the Moonraker has been re-targeted. After their debriefing at headquarters, Bond meets up with Brand, expecting her company—but they part ways after she reveals that she is engaged to a fellow Special Branch officer.

Background and writing history

In early 1953 the film producerAlexander Korda

Sir Alexander Korda (; born Sándor László Kellner; hu, Korda Sándor; 16 September 1893 – 23 January 1956)Live and Let Die'', and informed its author, Ian Fleming, that he was excited by the book, but that it would not make a good basis for a film. Fleming told the producer that his next book was to be an expansion of an idea for a screenplay, set in London and Kent, adding that the location would allow "for some wonderful film settings".

Fleming undertook a significant amount of background research in preparation for writing ''Moonraker''; he asked his fellow correspondent on ''

Fleming undertook a significant amount of background research in preparation for writing ''Moonraker''; he asked his fellow correspondent on ''

The locations draw from Fleming's personal experiences. ''Moonraker'' is the only Bond novel that takes place solely in Britain, which gave Fleming the chance to write about the England he cherished, such as the Kent countryside, including the

The locations draw from Fleming's personal experiences. ''Moonraker'' is the only Bond novel that takes place solely in Britain, which gave Fleming the chance to write about the England he cherished, such as the Kent countryside, including the

Parker describes the novel as "a hymn to England", and highlights Fleming's description of the white cliffs of Dover and the heart of London as evidence. Even the German Krebs is moved by the sight of the Kent countryside in a country he hates. The novel places England—and particularly London and Kent—in the front line of the cold war, and the threat to the location further emphasises its importance. Bennett and Woollacott consider that ''Moonraker'' defines the strengths and virtues of England and Englishness as being the "quiet and orderly background of English institutions", which are threatened by the disturbance Drax brings.

The literary critic Meir Sternberg considers the theme of English identity can be seen in the confrontation between Drax and Bond. Drax—whose real name is German for dragon—is in opposition to Bond, who takes the role of

Parker describes the novel as "a hymn to England", and highlights Fleming's description of the white cliffs of Dover and the heart of London as evidence. Even the German Krebs is moved by the sight of the Kent countryside in a country he hates. The novel places England—and particularly London and Kent—in the front line of the cold war, and the threat to the location further emphasises its importance. Bennett and Woollacott consider that ''Moonraker'' defines the strengths and virtues of England and Englishness as being the "quiet and orderly background of English institutions", which are threatened by the disturbance Drax brings.

The literary critic Meir Sternberg considers the theme of English identity can be seen in the confrontation between Drax and Bond. Drax—whose real name is German for dragon—is in opposition to Bond, who takes the role of

Fleming's friend—and neighbour in Jamaica—Noël Coward considered ''Moonraker'' to be the best thing Fleming had written to that point: "although as usual too far-fetched, not quite so much so as the last two ... His observation is extraordinary and his talent for description vivid." Fleming received numerous letters from readers complaining about the lack of exotic locations; one of which protested "We want taking out of ourselves, not sitting on the beach in Dover."

Fleming's friend—and neighbour in Jamaica—Noël Coward considered ''Moonraker'' to be the best thing Fleming had written to that point: "although as usual too far-fetched, not quite so much so as the last two ... His observation is extraordinary and his talent for description vivid." Fleming received numerous letters from readers complaining about the lack of exotic locations; one of which protested "We want taking out of ourselves, not sitting on the beach in Dover."

The actor John Payne attempted to take up the option on the film rights to the book in 1955, but nothing came of the attempt. The

The actor John Payne attempted to take up the option on the film rights to the book in 1955, but nothing came of the attempt. The

Ian Fleming.com

Official website of

Fleming undertook a significant amount of background research in preparation for writing ''Moonraker''; he asked his fellow correspondent on ''

Fleming undertook a significant amount of background research in preparation for writing ''Moonraker''; he asked his fellow correspondent on ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, w ...

'', Anthony Terry, for information on the Second World War German resistance force—the Werewolves

In folklore, a werewolf (), or occasionally lycanthrope (; ; uk, Вовкулака, Vovkulaka), is an individual that can shapeshift into a wolf (or, especially in modern film, a therianthropic hybrid wolf-like creature), either purposely ...

—and German V-2 rockets. The latter was a subject on which he wrote to the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke and the British Interplanetary Society

The British Interplanetary Society (BIS), founded in Liverpool in 1933 by Philip E. Cleator, is the oldest existing space advocacy organisation in the world. Its aim is exclusively to support and promote astronautics and space exploration.

Str ...

. Fleming also visited the Wimpole Street

Wimpole Street is a street in Marylebone, central London. Located in the City of Westminster, it is associated with private medical practice and medical associations. No. 1 Wimpole Street is an example of Edwardian baroque architecture, comple ...

psychiatrist Eric Strauss to discuss the traits of megalomaniacs; Strauss lent him the book ''Men of Genius'', which provided the link between megalomania and childhood thumb-sucking. Fleming used this information to give Drax diastema

A diastema (plural diastemata, from Greek διάστημα, space) is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition ...

, a common result of thumb-sucking. According to his biographer Andrew Lycett

Andrew Michael Duncan Lycett (born 1948) FRSL is an English biographer and journalist.

Early life

Born at Stamford, Lincolnshire to Peter Norman Lycett Lycett and Joan Mary Duncan (née Day), Lycett spent some of his childhood in Tanganyika, wher ...

, Fleming "wanted to make ''Moonraker'' his most ambitious and personal novel yet." Fleming, a keen card player, was fascinated by the background to the 1890 royal baccarat scandal, and when in 1953 he met a woman who had been present at the game, he questioned her so intently that she burst into tears.

In January 1954 Fleming and his wife, Ann, travelled to their Goldeneye estate in Jamaica for their annual two-month holiday. He had already written two Bond novels, '' Casino Royale'', which had been published in April 1953, and ''Live and Let Die'', whose publication was imminent. He began writing ''Moonraker'' on his arrival in the Caribbean. He later wrote an article for ''Books and Bookmen'' magazine describing his approach to writing, in which he said: "I write for about three hours in the morning ... and I do another hour's work between six and seven in the evening. I never correct anything and I never go back to see what I have written ... By following my formula, you write 2,000 words a day." By 24 February he had written over 30,000 words, although he wrote to a friend that he felt like he was already parodying the two earlier Bond novels. Fleming's own copy bears the following inscription, "This was written in January and February 1954 and published a year later. It is based on a film script I have had in my mind for many years." He later said that the idea for the film had been too short for a full novel, and that he "had to more or less graft the first half of the book onto my film idea in order to bring it up to the necessary length".

Fleming considered several titles for the story; his first choice had been ''The Moonraker'', until Noël Coward reminded him of a novel of the same name by F. Tennyson Jesse. Fleming then considered ''The Moonraker Secret'', ''The Moonraker Plot'', ''The Inhuman Element'', ''Wide of the Mark'', ''The Infernal Machine'', ''Mondays are Hell'' and ''Out of the Clear Sky''. George Wren Howard of Jonathan Cape suggested ''Bond & the Moonraker'', ''The Moonraker Scare'' and ''The Moonraker Plan'', while his friend, the writer William Plomer

William Charles Franklyn Plomer (10 December 1903 – 20 September 1973) was a South African and British novelist, poet and literary editor. He also wrote a series of librettos for Benjamin Britten. He wrote some of his poetry under the pseud ...

, suggested ''Hell is Here''; the final choice of ''Moonraker'' was a suggestion by Wren Howard.

Although Fleming provided no dates within his novels, two writers have identified different timelines based on events and situations within the novel series

A book series is a sequence of books having certain characteristics in common that are formally identified together as a group. Book series can be organized in different ways, such as written by the same author, or marketed as a group by their pub ...

as a whole. John Griswold and Henry Chancellor—both of whom have written books on behalf of Ian Fleming Publications

Ian Fleming Publications is the production company formerly known as both Glidrose Productions Limited and Glidrose Publications Limited, named after its founders John Gliddon and Norman Rose. In 1952, author Ian Fleming bought it after completi ...

—put the events of ''Moonraker'' in 1953; Griswold is more precise, and considers the story to have taken place in May of that year.

Development

Plot inspirations

White Cliffs of Dover

The White Cliffs of Dover is the region of English coastline facing the Strait of Dover and France. The cliff face, which reaches a height of , owes its striking appearance to its composition of chalk accented by streaks of black flint, depos ...

, and London clubland. Fleming owned a cottage in St Margaret's at Cliffe

St. Margaret's at Cliffe is a three-part village situated just off the coast road between Deal and Dover in Kent, England. The centre of the village is about ¾ mile (1km) from the sea, with the residential area of Nelson Park further inland, and ...

, near Dover, and he went to great lengths to get the details of the area right, including lending his car to his stepson to time the journey from London to Deal for the car chase passage. Fleming used his experiences of London clubs for the background of the Blades scenes. As a clubman, he enjoyed membership of Boodle's

Boodle's is a London gentlemen's club, founded in January 1762, at No. 50 Pall Mall, London, by Lord Shelburne, the future Marquess of Lansdowne and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

History

The club was originally based next door to Wi ...

, White's

White's is a gentlemen's club in St James's, London. Founded in 1693 as a hot chocolate shop in Mayfair, it is the oldest gentleman's club in London. It moved to its current premises on St James's Street in 1778.

Status

White's is the oldes ...

and the Portland Club, and a combination of Boodles and the Portland Club is thought to be the model for Blades; the author Michael Dibdin

Michael Dibdin (21 March 1947 – 30 March 2007) was a British crime writer, best known for inventing Aurelio Zen, the principal character in 11 crime novels set in Italy.

Early life

Dibdin was born in Wolverhampton, Staffordshire (now West M ...

found the scene in the club to be "surely one of the finest things that Ian Fleming ever did".

The early chapters of the novel centre on Bond's private life, with Fleming using his own lifestyle as a basis for Bond's. Fleming used further aspects of his private life, such as his friends, as he had done in his previous novels: Hugo Drax was named after his brother-in-law Hugo Charteris and a navy acquaintance Admiral Sir Reginald Aylmer Ranfurly Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, while Fleming's friend Duff Sutherland (described as "a scruffy looking chap") was one of the bridge players at Blades. The name of the Scotland Yard superintendent, Ronnie Vallance, was made up from those of Ronald Howe, the actual assistant commissioner at the Yard, and of Vallance Lodge & Co., Fleming's accountants. Other elements of the plot came from Fleming's knowledge of wartime operations carried out by T-Force

T-Force was the operational arm of a joint US Army–British Army mission to secure German scientific and industrial technology before it could be destroyed by retreating German forces or looters during the final stages of the Second World War an ...

, a secret British Army unit formed to continue the work of the Fleming-established 30 Assault Unit.

Characters

According to the author Raymond Benson, ''Moonraker'' is a deeper and more introspective book than Fleming's previous work, which allows the author to develop the characters further. As such, Bond "becomes something more than ... hecardboard figure" that he had been in the previous two novels. The start of the book concentrates on Bond at home and his daily routines, which Fleming describes as "Elastic office hours from around ten until six, ... evenings spent playing cards in the company of a few close friends, ... or making love, with rather cold passion, to one of three similarly disposed married women." This lifestyle was largely modelled on Fleming's own, which the journalist and writer Matthew Parker sees as showing "a sourness" in the author's character. According to Chancellor, two of Bond's other vices were also displayed in the book: his fondness for gambling—illegal except in private members clubs in 1955—and excessive drink and drug taking, neither of which were frowned upon in post-war upper class circles. In preparation for beating Drax at cards, Bond consumes a vodka martini, a carafe of vodka shared with M, two bottles of champagne and a brandy; he also mixes a quantity of Benzedrine, an amphetamine, into a glass of the champagne. According to ''The Times'' journalist and historian Ben Macintyre, to Fleming the alcohol consumption "meant relaxation, ritual and reliability". Benzedrine was regularly taken by troops during the war to remain awake and alert, and Fleming was an occasional consumer. Drax is physically abnormal, as are many of Bond's later adversaries. He has very broad shoulders, a large head and protruding teeth with diastema; his face is badly scarred from a wartime explosion. According to the writersKingsley Amis

Sir Kingsley William Amis (16 April 1922 – 22 October 1995) was an English novelist, poet, critic, and teacher. He wrote more than 20 novels, six volumes of poetry, a memoir, short stories, radio and television scripts, and works of social a ...

and Benson—both of whom subsequently wrote Bond novels—Drax is the most successful villain in the Bond canon. Amis considers this to be "because the most imagination and energy has gone into his portrayal. He lives in the real world ... ndhis physical presence fills ''Moonraker''. The view is shared by Chancellor, who considers Drax "perhaps the most believable" of all Fleming's villains. The cultural historian Jeremy Black writes that as with Le Chiffre

Le Chiffre (, "The Cypher" or "The Digit") is a fictional character and the main antagonist of Ian Fleming's 1953 novel, ''Casino Royale (novel), Casino Royale''. On screen Le Chiffre has been portrayed by Peter Lorre in the Casino Royale (195 ...

and Mr Big—the villains of the first two Bond novels—Drax's origins and war history are vital to an understanding of the character. Like several other antagonists in the Bond canon, Drax was German, reminding readers of a familiar threat in 1950s Britain. Because Drax is without a girlfriend or wife he is, according to the norms of Fleming and his works, abnormal in Bond's world.

Benson considers Brand to be one of the weakest female roles in the Bond canon and "a throwback to the rather stiff characterization of Vesper Lynd

Vesper Lynd is a fictional character featured in Ian Fleming's 1953 James Bond novel '' Casino Royale''. She was portrayed by Ursula Andress in the 1967 James Bond parody, which is only slightly based on the novel, and by Eva Green in the 20 ...

" from ''Casino Royale''. Brand's lack of interest in Bond removes sexual tension from the novel; she is unique in the canon for being the one woman that Bond does not seduce. The cultural historians Janet Woollacott and Tony Bennett

Anthony Dominick Benedetto (born August 3, 1926), known professionally as Tony Bennett, is an American retired singer of traditional pop standards, big band, show tunes, and jazz. Bennett is also a painter, having created works under his birt ...

write that the perceived reserve shown by Brand to Bond was not due to frigidity, but to her engagement to a fellow police officer.

M is another character who is more fully realised than in the previous novels, and for the first time in the series he is shown outside a work setting at the Blades club. It is never explained how he received or could afford his membership of the club, which had a restricted membership of only 200 gentlemen, all of whom had to show £100,000 in cash or gilt-edged securities. Amis, in his study '' The James Bond Dossier'', considers that on M's salary his membership of the club would have been puzzling; Amis points out that in the 1963 book '' On Her Majesty's Secret Service'' it is revealed that M's pay as head of the Secret Service is £6,500 a year.

Style

Benson analysed Fleming's writing style and identified what he described as the "Fleming Sweep": a stylistic technique that sweeps the reader from one chapter to another using 'hooks' at the end of each chapter to heighten tension and pull the reader into the next: Benson feels that the sweep in ''Moonraker'' was not as pronounced as Fleming's previous works, largely due to the lack of action sequences in the novel. According to the literary analyst LeRoy L. Panek, in his examination of 20th-century British spy novels, in ''Moonraker'' Fleming uses a technique closer to the detective story than to the thriller genre. This manifests itself in Fleming placing clues to the plot line throughout the story, and leaving Drax's unveiling of his plan until the later chapters. Black sees that the pace of the novel is set by the launch of the rocket (there are four days between Bond's briefing by M and the launch) while Amis considers that the story to have a "rather hurried" ending. ''Moonraker'' uses a literary device Fleming employs elsewhere, that of having a seemingly trivial incident between the main characters—the card game—that leads to the uncovering of a greater incident—the main plot involving the rocket. Dibdin sees gambling as the common link, thus the card game acts as an "introduction to the ensuing encounter ... for even higher stakes". Savoye sees this concept of competition between Bond and villain as a "notion of game and the eternal fight between Order and Disorder", common throughout the Bond stories.Themes

Parker describes the novel as "a hymn to England", and highlights Fleming's description of the white cliffs of Dover and the heart of London as evidence. Even the German Krebs is moved by the sight of the Kent countryside in a country he hates. The novel places England—and particularly London and Kent—in the front line of the cold war, and the threat to the location further emphasises its importance. Bennett and Woollacott consider that ''Moonraker'' defines the strengths and virtues of England and Englishness as being the "quiet and orderly background of English institutions", which are threatened by the disturbance Drax brings.

The literary critic Meir Sternberg considers the theme of English identity can be seen in the confrontation between Drax and Bond. Drax—whose real name is German for dragon—is in opposition to Bond, who takes the role of

Parker describes the novel as "a hymn to England", and highlights Fleming's description of the white cliffs of Dover and the heart of London as evidence. Even the German Krebs is moved by the sight of the Kent countryside in a country he hates. The novel places England—and particularly London and Kent—in the front line of the cold war, and the threat to the location further emphasises its importance. Bennett and Woollacott consider that ''Moonraker'' defines the strengths and virtues of England and Englishness as being the "quiet and orderly background of English institutions", which are threatened by the disturbance Drax brings.

The literary critic Meir Sternberg considers the theme of English identity can be seen in the confrontation between Drax and Bond. Drax—whose real name is German for dragon—is in opposition to Bond, who takes the role of Saint George

Saint George (Greek: Γεώργιος (Geórgios), Latin: Georgius, Arabic: القديس جرجس; died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was a Christian who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to tradition he was a soldie ...

in the conflict.

As with ''Casino Royale'' and ''Live and Let Die'', ''Moonraker'' involves the idea of the "traitor within". Drax, real name Graf Hugo von der Drache, is a "megalomaniac German Nazi who masquerades as an English gentleman", while Krebs bears the same name as Hitler's last Chief of Staff. Black sees that, in using a German as the novel's main enemy, "Fleming ... exploits another British cultural antipathy of the 1950s. Germans, in the wake of the Second World War, made another easy and obvious target for bad press." ''Moonraker'' uses two of the foes feared by Fleming, the Nazis and the Soviets, with Drax being German and working for the Soviets; in ''Moonraker'' the Soviets were hostile and provided not just the atomic bomb, but support and logistics to Drax. ''Moonraker'' played on fears of the audiences of the 1950s of rocket attacks from overseas, fears grounded in the use of the V-2 rocket by the Nazis during the Second World War. The story takes the threat one stage further, with a rocket based on English soil, aimed at London and "the end of British invulnerability".

Publication and reception

Publication history

''Moonraker'' was published in the UK by Jonathan Cape in hardback format on 5 April 1955 with a cover designed by Kenneth Lewis, following Fleming's suggestions of using a stylised flame motif; the first impression was of 9,900 copies. The US publication was by Macmillan on 20 September that year. In October 1956Pan Books

Pan Books is a publishing imprint that first became active in the 1940s and is now part of the British-based Macmillan Publishers, owned by the Georg von Holtzbrinck Publishing Group of Germany.

Pan Books began as an independent publisher, es ...

published a paperback version of the novel in the UK, which sold 43,000 copies before the end of the year. In December that year the US paperback was published under the title ''Too Hot to Handle'' by Permabooks. This edition was rewritten to Americanise the British idioms used, and Fleming provided explanatory footnotes such as the value of English currency against the dollar. Since its initial publication the book has been issued in numerous hardback and paperback editions, translated into several languages and has never been out of print.

Reception

Fleming's friend—and neighbour in Jamaica—Noël Coward considered ''Moonraker'' to be the best thing Fleming had written to that point: "although as usual too far-fetched, not quite so much so as the last two ... His observation is extraordinary and his talent for description vivid." Fleming received numerous letters from readers complaining about the lack of exotic locations; one of which protested "We want taking out of ourselves, not sitting on the beach in Dover."

Fleming's friend—and neighbour in Jamaica—Noël Coward considered ''Moonraker'' to be the best thing Fleming had written to that point: "although as usual too far-fetched, not quite so much so as the last two ... His observation is extraordinary and his talent for description vivid." Fleming received numerous letters from readers complaining about the lack of exotic locations; one of which protested "We want taking out of ourselves, not sitting on the beach in Dover."

Julian Symons

Julian Gustave Symons (originally Gustave Julian Symons) (pronounced ''SIMM-ons''; 30 May 1912 – 19 November 1994) was a British crime writer and poet. He also wrote social and military history, biography and studies of literature. He was bor ...

, writing in ''The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication ...

'', found ''Moonraker'' "a disappointment", and considered that "Fleming's tendency ... to parody the form of the thriller, has taken charge in the second half of this story." Maurice Richardson, in his review for ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

'', was more welcoming: "Do not miss this", he urged, saying that "Mr. Fleming continues to be irresistibly readable, however incredible". Hilary Corke, writing in '' The Listener'', thought that "Fleming is one of the most accomplished of thriller-writers", and considered that ''Moonraker'' "is as mercilessly readable as all the rest". Corke warned Fleming away from being over-dramatic, declaring that "Mr Fleming is evidently far too accomplished to need to lean upon these blood-and-thunder devices: he could keep our hair on end for three hundred pages without spilling more blood than was allowed to Shylock." The reviewer in ''The Scotsman

''The Scotsman'' is a Scottish compact newspaper and daily news website headquartered in Edinburgh. First established as a radical political paper in 1817, it began daily publication in 1855 and remained a broadsheet until August 2004. Its pare ...

'' considered that Fleming "administers stimuli with no mean hand ... 'Astonish me!' the addict may challenge: Mr Fleming can knock him sideways."

John Metcalf for ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'' thought the book "utterly disgraceful—and highly enjoyable ... without 'Moonraker''no forthcoming railway journey should be undertaken", although he also considered that it was "not one of Mr. Fleming's best". Anthony Boucher

William Anthony Parker White (August 21, 1911 – April 29, 1968), better known by his pen name Anthony Boucher (), was an American author, critic, and editor who wrote several classic mystery novels, short stories, science fiction, and radio d ...

, writing in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', was equivocal, saying "I don't know anyone who writes about gambling more vividly than Fleming and I only wish the other parts of his books lived up to their gambling sequences". Richard Lister in the ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British Political magazine, political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney Webb, Sidney and Beatrice ...

'' thought that "Mr. Fleming is splendid; he stops at nothing." Writing for ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'', Al Manola believed that the "British tradition of rich mystery writing, copious description and sturdy heroism all blend nicely" in ''Moonraker'', providing what he considered was "probably the best action novel of the month".

Adaptations

The actor John Payne attempted to take up the option on the film rights to the book in 1955, but nothing came of the attempt. The

The actor John Payne attempted to take up the option on the film rights to the book in 1955, but nothing came of the attempt. The Rank Organisation

The Rank Organisation was a British entertainment conglomerate founded by industrialist J. Arthur Rank in April 1937. It quickly became the largest and most vertically integrated film company in the United Kingdom, owning production, distrib ...

also came to an agreement to make a film, but this likewise fell through.

The novel was not one of Fleming's stories acquired by Eon Productions

Eon Productions Ltd. is a British film production company that primarily produces the ''James Bond'' film series. The company is based in London's Piccadilly and also operates from Pinewood Studios in the UK.

''Bond'' films

Eon was started ...

in 1961; in 1969 the company acquired the rights and commissioned Gerry Anderson

Gerald Alexander Anderson (; 14 April 1929 – 26 December 2012) was an English television and film producer, director, writer and occasional voice artist. He remains famous for his futuristic television programmes, especially his 1960s produ ...

to produce and co-write a screenplay. Anderson and Tony Barwick prepared a 70-page treatment that was never filmed, but some elements were similar to the final screenplay of '' The Spy Who Loved Me''.

The first adaptation of ''Moonraker'' was for South African radio in 1956, with Bob Holness

Robert Wentworth John Holness (12 November 1928 – 6 January 2012) was a British-South African radio and television presenter and occasional actor. He presented the British version of '' Blockbusters''.

Early life

Holness was born in Vryheid, ...

providing the voice of Bond. According to ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publish ...

'', "listeners across the Union thrilled to Bob's cultured tones as he defeated evil master criminals in search of world domination". The novel was adapted as a comic strip that was published in the '' Daily Express'' newspaper and syndicated worldwide. The adaptation was written by Henry Gammidge and illustrated by John McLusky, and ran daily from 30 March to 8 August 1959. Titan Books

Titan Publishing Group is the publishing division of Titan Entertainment Group, which was established in 1981. The books division has two main areas of publishing: film and television tie-ins and cinema reference books; and graphic novels and c ...

reprinted the strip in 2005 along with ''Casino Royale'' and ''Live and Let Die'' as a part of the ''Casino Royale'' anthology.

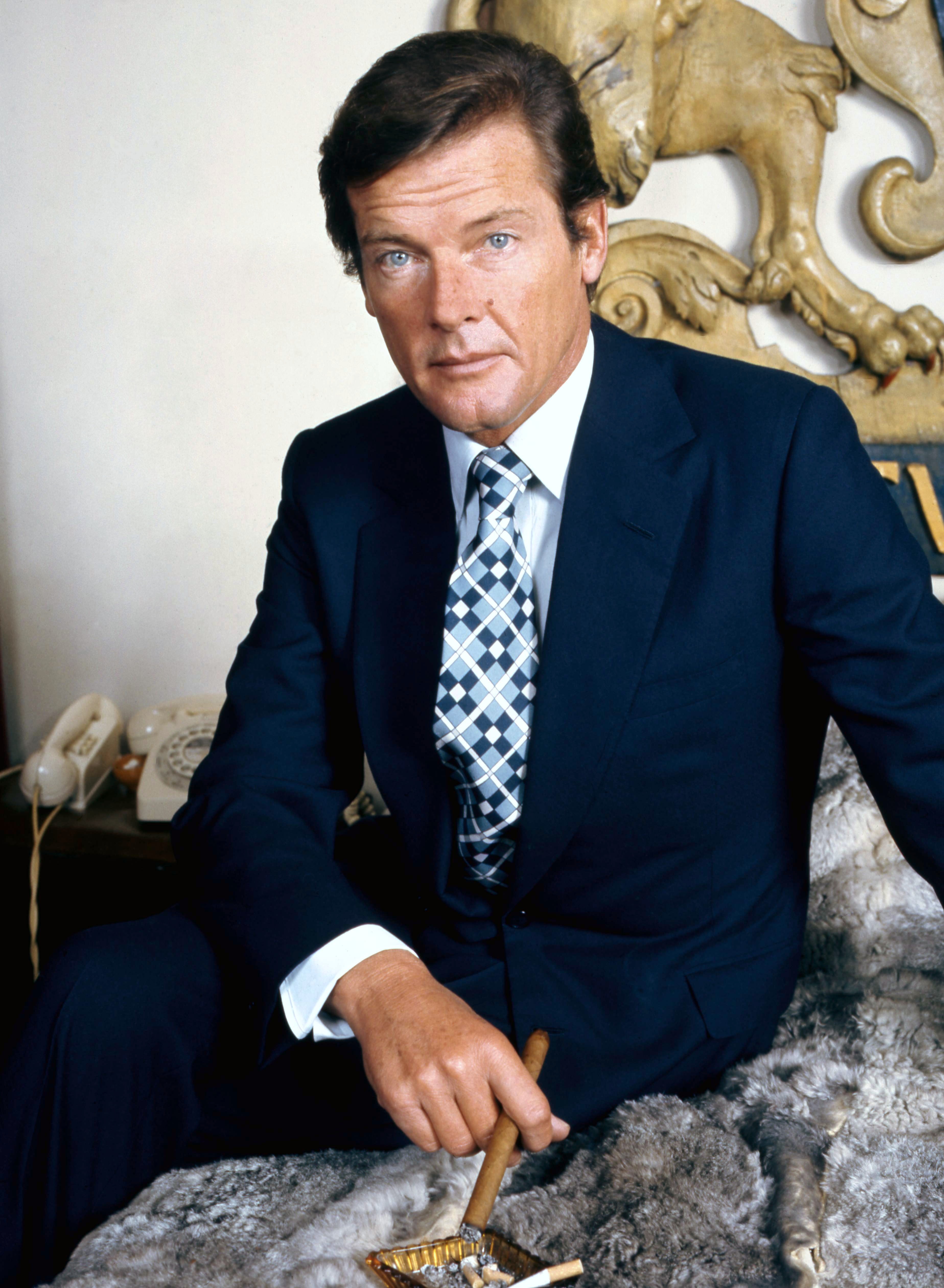

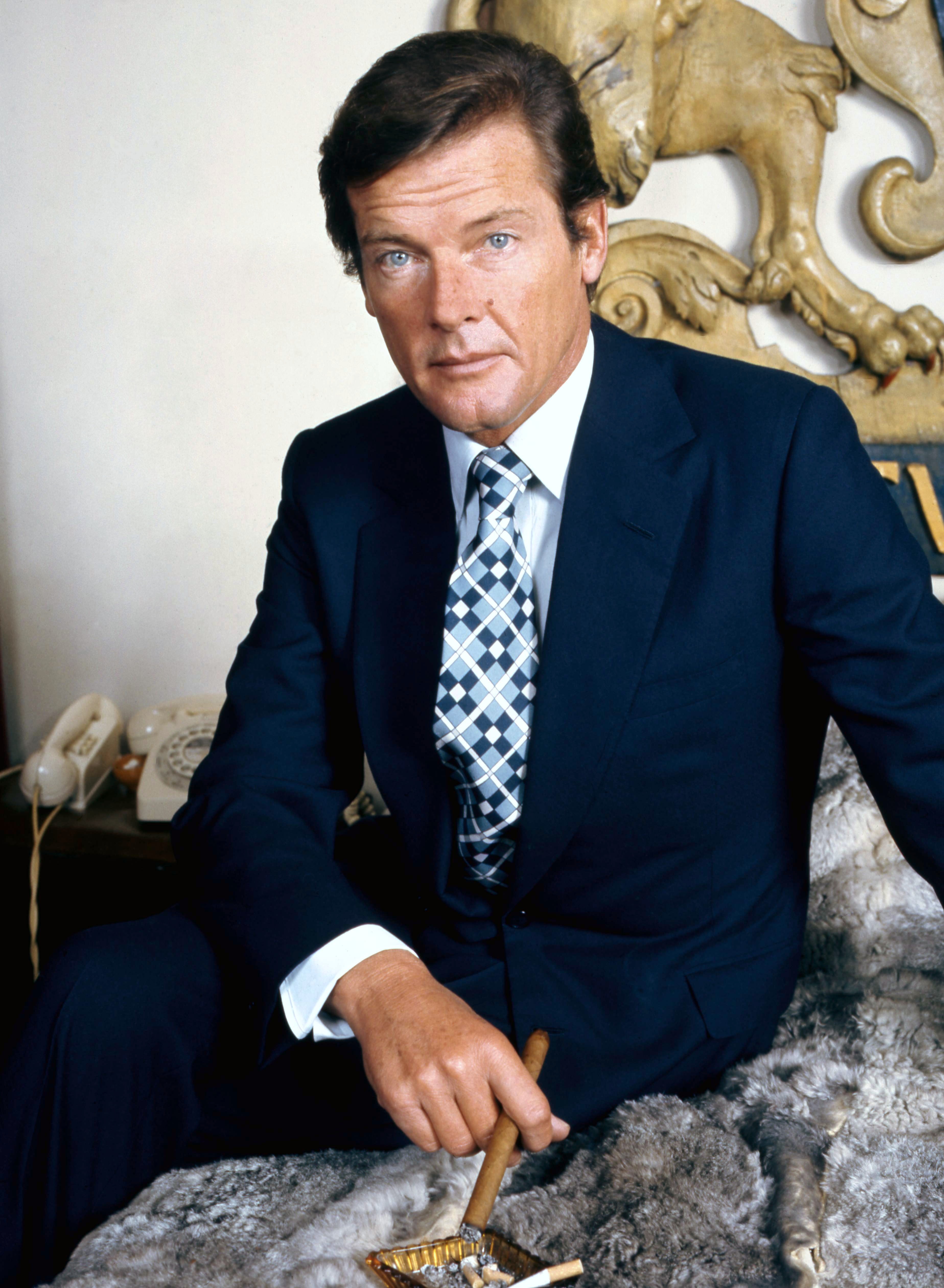

"Moonraker" was used as the title for the eleventh James Bond film, produced by Eon Productions and released in 1979. Directed by Lewis Gilbert

Lewis Gilbert (6 March 1920 – 23 February 2018) was an English film director, producer and screenwriter who directed more than 40 films during six decades; among them such varied titles as ''Reach for the Sky'' (1956), ''Sink the Bismarck!'' ...

and produced by Albert R. Broccoli

Albert Romolo Broccoli ( ; April 5, 1909 – June 27, 1996), nicknamed "Cubby", was an American film producer who made more than 40 motion pictures throughout his career. Most of the films were made in the United Kingdom and often filmed at Pi ...

, the film features Roger Moore in his fourth appearance as Bond. The Nazi-inspired element of Drax's motivation in the novel was indirectly preserved with the "master race" theme of the film's plot. Since the screenplay was original, Eon Productions and Glidrose Publications authorised the film's writer, Christopher Wood, to produce his second novelization based on a film; this was entitled ''James Bond and Moonraker

''James Bond and Moonraker'' is a novelization by Christopher Wood of the James Bond film '' Moonraker''. Its name was changed to avoid confusion with Fleming's novel. It was released in 1979.

Plot

British Secret Service agent James Bond, cod ...

''. Elements of ''Moonraker'' were also used in the 2002 film ''Die Another Day

''Die Another Day'' is a 2002 spy film and the twentieth film in the ''James Bond'' series produced by Eon Productions. It was produced by Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli, and directed by Lee Tamahori. The fourth and final film st ...

'', with a scene set in the Blades club. The actress Rosamund Pike

Rosamund Mary Ellen Pike (born 1979) is a British actress. She began her acting career by appearing in stage productions such as ''Romeo and Juliet'' and ''Gas Light''. After her screen debut in the television film ''A Rather English Marriage'' ...

, who plays Miranda Frost in the film, later said that her character was originally to have been named Gala Brand.

Notes and references

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Ian Fleming.com

Official website of

Ian Fleming Publications

Ian Fleming Publications is the production company formerly known as both Glidrose Productions Limited and Glidrose Publications Limited, named after its founders John Gliddon and Norman Rose. In 1952, author Ian Fleming bought it after completi ...

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Moonraker (Novel)

1955 British novels

British novels adapted into films

James Bond books

Jonathan Cape books

Novel

Novels adapted into comics

Novels by Ian Fleming

Novels set in Kent