Milt Hinton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Milton John Hinton (June 23, 1910 – December 19, 2000) was an American double bassist and photographer.

Regarded as the Dean of American jazz bass players, his nicknames included "Sporty" from his years in Chicago, "Fump" from his time on the road with

Hinton moved with his extended family to

Hinton moved with his extended family to

In 1936, Hinton joined the

In 1936, Hinton joined the

By far, his most regular work during this era was in the recording studio, where Hinton was among the first African-Americans to be regularly hired for studio contract work. From the mid-1950s through the early 1970s, he contributed to thousands of jazz and popular records, as well as hundreds of jingles and film soundtracks. He would regularly play on three three-hour studio sessions per day, requiring him to own multiple basses that he hired assistants to transport from one studio to the next. During this era, he recorded with everyone from

By far, his most regular work during this era was in the recording studio, where Hinton was among the first African-Americans to be regularly hired for studio contract work. From the mid-1950s through the early 1970s, he contributed to thousands of jazz and popular records, as well as hundreds of jingles and film soundtracks. He would regularly play on three three-hour studio sessions per day, requiring him to own multiple basses that he hired assistants to transport from one studio to the next. During this era, he recorded with everyone from

By the late 1960s, studio work began dropping off, so Hinton incorporated more live performances into his schedule. He regularly accepted club gigs, most often at Michael's Pub, Zinno's, and the Rainbow Room where he performed with

By the late 1960s, studio work began dropping off, so Hinton incorporated more live performances into his schedule. He regularly accepted club gigs, most often at Michael's Pub, Zinno's, and the Rainbow Room where he performed with  By the 1990s, he was revered as an elder statesman in jazz, and he was regularly honored with significant awards and accolades. He received honorary doctorates from

By the 1990s, he was revered as an elder statesman in jazz, and he was regularly honored with significant awards and accolades. He received honorary doctorates from

Milt Hinton film clipsNPR Documentary on Milt Hinton's life and musicSmithsonian Oral History Interview with Milt HintonMilt Hinton Interview

NAMM Oral History Library (1994)

Milt Hinton recordings

at the

Cab Calloway

Cabell Calloway III (December 25, 1907 – November 18, 1994) was an American singer, songwriter, bandleader, conductor and dancer. He was associated with the Cotton Club in Harlem, where he was a regular performer and became a popular vocalis ...

, and "The Judge" from the 1950s and beyond. Hinton's recording career lasted over 60 years, mostly in jazz but also with a variety of other genres as a prolific session musician

Session musicians, studio musicians, or backing musicians are musicians hired to perform in recording sessions or live performances. The term sideman is also used in the case of live performances, such as accompanying a recording artist on a ...

.

He was also a photographer of note, praised for documenting American jazz during the 20th Century.

Biography

Early life in Mississippi (1910–1919)

Hinton was born inVicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a historic city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the county seat, and the population at the 2010 census was 23,856.

Located on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, Vi ...

, United States, the only child of Hilda Gertrude Robinson, whom he referred to as "Titter," and Milton Dixon Hinton. He was three-months-old when his father left the family. He grew up in a home with his mother, his maternal grandmother (a former slave of Joe Davis, the brother of Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

), and two of his mother's sisters.

His childhood in Vicksburg was characterized by extreme poverty and extreme racism. Lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

was a common practice at the time. Hinton said that one of the clearest memories of his childhood was when he accidentally came upon a lynching.

Growing up in Chicago (1919–1935)

Hinton moved with his extended family to

Hinton moved with his extended family to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

, in late 1919, which created opportunities for him. Chicago was where Hinton first encountered economic diversity among African-Americans, about which he later noted, "That's when I realized that being black didn't always mean you had to be poor." It was also where he experienced an abundance of music, either in person or through live performances on the radio. During this time he first heard concerts featuring Louis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and Singing, vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and se ...

, Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was bas ...

, Fletcher Henderson

James Fletcher Hamilton Henderson (December 18, 1897 – December 29, 1952) was an American pianist, bandleader, arranger and composer, important in the development of big band jazz and swing music. He was one of the most prolific black music ...

, Earl Hines

Earl Kenneth Hines, also known as Earl "Fatha" Hines (December 28, 1903 – April 22, 1983), was an American jazz pianist and bandleader. He was one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano and, according to one source, " ...

, Eddie South, and many others.

Music was a fixture at home. His mother and other relatives regularly played piano. He received his first instrument – a violin – in 1923 for his thirteenth birthday, which he studied for four years. In addition to taking lessons on the violin, Hinton and his mother attended performances at the Vendome Theater every Sunday, featuring the orchestra of Erskine Tate with Louis Armstrong as a feature soloist.

After graduating from Wendell Phillips High School

Wendell Phillips Academy High School is a public 4–year high school located in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the south side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Phillips is part of the Chicago Public Schools district and is managed by the Aca ...

, Hinton attended Crane Junior College

Malcolm X College, one of the City Colleges of Chicago, is a two-year college located on the Near West Side of Chicago, Illinois. It was founded as Crane Junior College in 1911 and was the first of the City Colleges. Crane ceased operations at ...

for two years, during which time he began receiving regular work as a freelance musician around Chicago. He performed with Freddie Keppard, Zutty Singleton

Arthur James "Zutty" Singleton (May 14, 1898 – July 14, 1975) was an American jazz drummer.

Career

Singleton was born in Bunkie, Louisiana, United States, and raised in New Orleans. According to his ''Jazz Profiles'' biography, his unusual ...

, Jabbo Smith

Jabbo Smith (born Cladys Smith; December 24, 1908 – January 16, 1991) was an American jazz musician, known for his virtuoso playing on the trumpet.

Biography

Smith was born in Pembroke, Georgia, United States. At the age of six he went into ...

, Erskine Tate, and Art Tatum

Arthur Tatum Jr. (, October 13, 1909 – November 5, 1956) was an American jazz pianist who is widely regarded as one of the greatest in his field. From early in his career, Tatum's technical ability was regarded by fellow musicians as extraord ...

. Hinton soon taught himself to play the double bass

The double bass (), also known simply as the bass () (or #Terminology, by other names), is the largest and lowest-pitched Bow (music), bowed (or plucked) string instrument in the modern orchestra, symphony orchestra (excluding unorthodox addit ...

because opportunities for violinists were limited. His first steady job began in the spring of 1930, playing tuba (and later double bass) in the band of pianist Tiny Parham. His recording debut on November 4, 1930, was on tuba with Parham's band on a tune titled "Squeeze Me." After graduating from Crane Junior College in 1932, attended Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

for one semester, then dropped out to pursue music full-time. He received steady work from 1932 through 1935 in a quartet with violinist Eddie South, with extended residencies in California, Chicago, and Detroit. With this group he first recorded on double bass in early 1933.

The Cab Calloway era (1936–1950)

In 1936, Hinton joined the

In 1936, Hinton joined the Cab Calloway

Cabell Calloway III (December 25, 1907 – November 18, 1994) was an American singer, songwriter, bandleader, conductor and dancer. He was associated with the Cotton Club in Harlem, where he was a regular performer and became a popular vocalis ...

Orchestra, initially as a temporary replacement for Al Morgan, while the band was on tour en route to a six-month residency at the newly opened midtown location of the Cotton Club

The Cotton Club was a New York City nightclub from 1923 to 1940. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue (1923–1936), then briefly in the midtown Theater District (1936–1940).Elizabeth Winter"Cotton Club of Harlem (1923- )" Blac ...

in New York City. He quickly found acceptance among the band members, and he ended up staying with Calloway for over fifteen years. Until the Cotton Club closed in 1940, the Calloway band performed there for up to six months per year, going on tour for the remaining six months of the year. During the Cotton Club residencies, Hinton took part in recording sessions with Benny Goodman

Benjamin David Goodman (May 30, 1909 – June 13, 1986) was an American clarinetist and bandleader known as the "King of Swing".

From 1936 until the mid-1940s, Goodman led one of the most popular swing big bands in the United States. His conc ...

, Lionel Hampton

Lionel Leo Hampton (April 20, 1908 – August 31, 2002) was an American jazz vibraphonist, pianist, percussionist, and bandleader. Hampton worked with jazz musicians from Teddy Wilson, Benny Goodman, and Buddy Rich, to Charlie Parker, Charles ...

, Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan; April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed "Lady Day" by her friend and music partner, Lester Young, Holiday had an innovative influence on jazz music and pop s ...

, Ethel Waters

Ethel Waters (October 31, 1896 – September 1, 1977) was an American singer and actress. Waters frequently performed jazz, swing, and pop music on the Broadway stage and in concerts. She began her career in the 1920s singing blues. Her no ...

, Teddy Wilson

Theodore Shaw Wilson (November 24, 1912 – July 31, 1986) was an American jazz pianist. Described by critic Scott Yanow as "the definitive swing pianist", Wilson had a sophisticated, elegant style. His work was featured on the records of many ...

, and many others. It was at this time that he recorded what is possibly the first bass feature, "Pluckin' the Bass" in August 1939.

Hinton appeared regularly on radio while in Calloway's band, either on bass in concerts broadcast from the Cotton Club, or as a cast member for the short-lived music quiz show "Cab Calloway's Quizzicale." These broadcasts brought national attention to the Calloway band and helped enable the successful national tours the band would schedule. They also gave listeners a chance to hear examples of jive talk, which Calloway would formalize through publications such as his ''Hepster's Dictionary'', first published in 1938.

Calloway's band included renowned sidemen such as Danny Barker

Daniel Moses Barker (January 13, 1909 – March 13, 1994) was an American jazz musician, vocalist, and author from New Orleans. He was a rhythm guitarist for Cab Calloway, Lucky Millinder and Benny Carter during the 1930s.

One of Barker's earl ...

, Chu Berry, Doc Cheatham

Adolphus Anthony Cheatham, better known as Doc Cheatham (June 13, 1905 – June 2, 1997), was an American jazz trumpeter, singer, and bandleader. He is also the Grandfather of musician Theo Croker.

Early life

Doc Cheatham was born in Nashv ...

, Cozy Cole

William Randolph "Cozy" Cole (October 17, 1909 – January 9, 1981) was an American jazz drummer who worked with Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong among others and led his own groups.

Life and career

William Randolph Cole was born in East Or ...

, Dizzy Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie (; October 21, 1917 – January 6, 1993) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer, educator and singer. He was a trumpet virtuoso and improviser, building on the virtuosic style of Roy Eldridge but a ...

, Illinois Jacquet

Jean-Baptiste "Illinois" Jacquet (October 30, 1922 – July 22, 2004) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist, best remembered for his solo on " Flying Home", critically recognized as the first R&B saxophone solo.

Although he was a pioneer of ...

, Jonah Jones

Jonah Jones (born Robert Elliott Jones; December 31, 1909 – April 29, 2000) was a jazz trumpeter who created concise versions of jazz and swing and jazz standards that appealed to a mass audience. In the jazz community, he is known for his wo ...

, Ike Quebec

Ike Abrams Quebec (August 17, 1918 – January 16, 1963) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. He began his career in the big band era of the 1940s, then fell from prominence for a time until launching a comeback in the years before his dea ...

, and Ben Webster

Benjamin Francis Webster (March 27, 1909 – September 20, 1973) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist.

Career Early life and career

A native of Kansas City, Missouri, he studied violin, learned how to play blues on the piano from ...

. Hinton credits Chu Berry with elevating the overall musicianship of the Calloway band, in part by encouraging Cab to hire arrangers such as Benny Carter

Bennett Lester Carter (August 8, 1907 – July 12, 2003) was an American jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, trumpeter, composer, arranger, and bandleader. With Johnny Hodges, he was a pioneer on the alto saxophone. From the beginning of his career ...

, to create new arrangements that would challenge the musicians. As Hinton put it, "Musically he was the greatest thing that ever happened to the band." Hinton was also heavily influenced by the musical innovations of Dizzy Gillespie, with whom he had informal sessions in the late 1930s, during breaks between sets at the Cotton Club. Hinton credits Gillespie with introducing him to many of the experimental harmonic practices and chord substitutions, that would later be associated with bebop.

In 1939 when Hinton returned to Chicago for his grandmother's funeral, he met Mona Clayton, who was then singing in his mother's church choir. The two were married a few years later and remained inseparable for the rest of Milt's life. (Mona was his second wife; the first was a brief relationship in the 1930s with Oby Allen, a friend he knew from high school.) He and Mona's only child, Charlotte, was born on February 28, 1947. Mona had begun traveling with the Calloway Orchestra in the early 1940s — the only musician's friend or spouse to do so. She helped musicians in the band manage their money, and she often insisted that they open savings accounts. For band members, she was a trusted confidant who was known for her discretion. When traveling with a toddler became too difficult, the Hintons bought a two-family house in Queens, and ten years later they purchased a larger single-family home in an adjacent neighborhood where they remained for the rest of their lives.

In addition to caring for their daughter, Mona handled the family's finances, and her attention to detail ensured the couple's financial security later in life. She kept track of Hinton's freelance work, scheduled interviews, coordinated public relations events, and often drove him back and forth to gigs (Hinton never drove as an adult, due in part to a car accident he was involved in as a teenager in Chicago). In the mid 1960s, Mona completed both a bachelor's and a master's degree and taught in the public schools for several years. In the 1970s, she began traveling with Hinton again and was regularly invited to join him at jazz parties and festivals where he performed. At the same time, she was active as a music contractor for Lena Horne

Lena Mary Calhoun Horne (June 30, 1917 – May 9, 2010) was an American dancer, actress, singer, and civil rights activist. Horne's career spanned more than seventy years, appearing in film, television, and theatre. Horne joined the chorus of th ...

and others. Mona was always well respected in the jazz community, and she and Hinton were viewed by many as role models; as the jazz historian Dan Morgenstern noted in an article from 2000, "If there is a closer couple, I'd be surprised."

After Cab Calloway (1950–1954)

By 1950, popular music tastes had changed, and Calloway lacked the funds to support a full big band. Instead, he hired Hinton and a few others to create a smaller ensemble, first a septet and later a quartet, which toured until June 1952, with trips to Cuba and Uruguay. After the Calloway ensemble disbanded, Hinton spent more time as a freelancestudio musician

Session musicians, studio musicians, or backing musicians are musicians hired to perform in recording sessions or live performances. The term sideman is also used in the case of live performances, such as accompanying a recording artist on a t ...

in New York City. At first, the work was sporadic, and, as Hinton put it, "This was the one period in my life when I was worried about earning a living." He played as many clubs and restaurants as possible, a practice he would continue for the next several decades. He performed regularly at La Vie en Rose, the Embers, the Metropole, and Basin Street West, where he appeared with Jackie Gleason

John Herbert Gleason (February 26, 1916June 24, 1987) was an American actor, comedian, writer, composer, and conductor known affectionately as "The Great One." Developing a style and characters from growing up in Brooklyn, New York, he was know ...

, Phil Moore, and Joe Bushkin. In the early 1950s, he performed with Count Basie

William James "Count" Basie (; August 21, 1904 – April 26, 1984) was an American jazz pianist, organist, bandleader, and composer. In 1935, he formed the Count Basie Orchestra, and in 1936 took them to Chicago for a long engagement and the ...

for a brief time in the New York area.

Although his freelance work was increasing, in July 1953 Hinton signed a one-year contract to tour with Louis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and Singing, vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and se ...

. He described the decision as "very difficult" as it would force him to be away from his family, and it would also slow down the momentum he was gaining as a freelance musician in New York City. Steady pay and the opportunity to perform with Armstrong were persuasive, and Hinton performed dozens of concerts, including a tour of Japan, as a member of the band. When an opportunity to join the house band for a television show hosted by Robert Q. Lewis in New York opened up in February 1954, Hinton gave his notice to Armstrong and returned to Queens.

In the studios (1954–1970)

For roughly the next two decades he performed regularly on numerous radio and television programs, including those hosted byJackie Gleason

John Herbert Gleason (February 26, 1916June 24, 1987) was an American actor, comedian, writer, composer, and conductor known affectionately as "The Great One." Developing a style and characters from growing up in Brooklyn, New York, he was know ...

, Robert Q. Lewis, Galen Drake, Patti Page

Clara Ann Fowler (November 8, 1927 – January 1, 2013), known professionally as Patti Page, was an American singer and actress. Primarily known for pop and country music, she was the top-charting female vocalist and best-selling female ar ...

, Polly Bergen

Polly Bergen (born Nellie Paulina Burgin; July 14, 1930 – September 20, 2014) was an American actress, singer, television host, writer and entrepreneur.

She won an Emmy Award in 1958 for her performance as Helen Morgan in '' The Helen ...

, Teddy Wilson

Theodore Shaw Wilson (November 24, 1912 – July 31, 1986) was an American jazz pianist. Described by critic Scott Yanow as "the definitive swing pianist", Wilson had a sophisticated, elegant style. His work was featured on the records of many ...

, Mitch Miller

Mitchell William Miller (July 4, 1911 – July 31, 2010) was an American choral conductor, record producer, record-industry executive, and professional oboist. He was involved in almost all aspects of the industry, particularly as a conductor ...

, Dick Cavett

Richard Alva Cavett (; born November 19, 1936) is an American television personality and former talk show host. He appeared regularly on nationally broadcast television in the United States for five decades, from the 1960s through the 2000s.

In ...

, and others. As he recalled, "I had a great situation because I was never on staff. That meant I'd get paid by the show. And since I never spent more than fifteen hours a week on rehearsals and shows, I always had free time to do record dates."

By far, his most regular work during this era was in the recording studio, where Hinton was among the first African-Americans to be regularly hired for studio contract work. From the mid-1950s through the early 1970s, he contributed to thousands of jazz and popular records, as well as hundreds of jingles and film soundtracks. He would regularly play on three three-hour studio sessions per day, requiring him to own multiple basses that he hired assistants to transport from one studio to the next. During this era, he recorded with everyone from

By far, his most regular work during this era was in the recording studio, where Hinton was among the first African-Americans to be regularly hired for studio contract work. From the mid-1950s through the early 1970s, he contributed to thousands of jazz and popular records, as well as hundreds of jingles and film soundtracks. He would regularly play on three three-hour studio sessions per day, requiring him to own multiple basses that he hired assistants to transport from one studio to the next. During this era, he recorded with everyone from Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan; April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed "Lady Day" by her friend and music partner, Lester Young, Holiday had an innovative influence on jazz music and pop s ...

to Paul McCartney

Sir James Paul McCartney (born 18 June 1942) is an English singer, songwriter and musician who gained worldwide fame with the Beatles, for whom he played bass guitar and shared primary songwriting and lead vocal duties with John Lennon. One ...

, Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Nicknamed the " Chairman of the Board" and later called "Ol' Blue Eyes", Sinatra was one of the most popular entertainers of the 1940s, 1950s, and ...

to Leon Redbone

Leon Redbone (born Dickran Gobalian; August 26, 1949 – May 30, 2019) was a singer-songwriter and musician specializing in jazz, blues, and Tin Pan Alley classics. Recognized by his hat (often a Panama hat), dark sunglasses, and black tie, Re ...

, and Sam Cooke

Samuel Cook (January 22, 1931 – December 11, 1964), known professionally as Sam Cooke, was an American singer and songwriter. Considered to be a pioneer and one of the most influential soul music, soul artists of all time, Cooke is common ...

to Barbra Streisand

Barbara Joan "Barbra" Streisand (; born April 24, 1942) is an American singer, actress and director. With a career spanning over six decades, she has achieved success in multiple fields of entertainment, and is among the few performers awar ...

. As Hinton summarized his time in the studios, "I might be on a date for Andre Kostelanetz

Andre Kostelanetz (russian: Абрам Наумович Костелянец; December 22, 1901 – January 13, 1980) was a Russian-born American popular orchestral music conductor and arranger who was one of the major exponents of popular orch ...

in the morning, do one with Brook Benton

Benjamin Franklin Peay (September 19, 1931 – April 9, 1988), better known as Brook Benton, was an American singer and songwriter who was popular with rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and pop music audiences during the late 1950s and early 1960 ...

or Johnny Mathis

John Royce Mathis (born September 30, 1935) is an American singer of popular music. Starting his career with singles of standard music, he became highly popular as an album artist, with several dozen of his albums achieving gold or platinum s ...

in the afternoon, and then finish up the day with Paul Anka

Paul Albert Anka (born July 30, 1941) is a Canadian-American singer, songwriter and actor. He is best known for his signature hit songs including " Diana", " Lonely Boy", " Put Your Head on My Shoulder", and "(You're) Having My Baby". Anka also ...

or Bobby Rydell

Robert Louis Ridarelli (April 26, 1942 – April 5, 2022), known by the stage name Bobby Rydell, was an American singer and actor who mainly performed rock and roll and traditional pop music. In the early 1960s he was considered a teen idol. Hi ...

. At one time or another, I probably played for just about every popular artist around in those days."

Starting in the mid-1950s, he regularly worked in the studio with Hank Jones

Henry Jones Jr. (July 31, 1918 – May 16, 2010) was an American jazz pianist, bandleader, arranger, and composer. Critics and musicians described Jones as eloquent, lyrical, and impeccable. In 1989, The National Endowment for the Arts honored ...

(piano), Barry Galbraith

Joseph Barry Galbraith (December 18, 1919 – January 13, 1983) was an American jazz guitarist.

Galbraith moved to New York City from McDonald, PA in the early 1940s and found work playing with Babe Russin, Art Tatum, Red Norvo, Hal McIntyre, an ...

(guitar), and Osie Johnson

James "Osie" Johnson (January 11, 1923, in Washington, D.C. – February 10, 1966, in New York City) was a jazz drummer, arranger and singer.

Johnson studied at Armstrong Highschool where he was classmates with Leo Parker and Frank Wess. He firs ...

(drums) in a group that informally became known as the New York Rhythm Section. The four played on hundreds of sessions together and even recorded an LP in 1956 that was titled, ''The Rhythm Section''.

After the studios (1970–2000)

By the late 1960s, studio work began dropping off, so Hinton incorporated more live performances into his schedule. He regularly accepted club gigs, most often at Michael's Pub, Zinno's, and the Rainbow Room where he performed with

By the late 1960s, studio work began dropping off, so Hinton incorporated more live performances into his schedule. He regularly accepted club gigs, most often at Michael's Pub, Zinno's, and the Rainbow Room where he performed with Benny Goodman

Benjamin David Goodman (May 30, 1909 – June 13, 1986) was an American clarinetist and bandleader known as the "King of Swing".

From 1936 until the mid-1940s, Goodman led one of the most popular swing big bands in the United States. His conc ...

, Johnny Hartman

John Maurice Hartman (July 3, 1923 – September 15, 1983) was an American jazz singer who specialized in ballads. He sang and recorded with Earl Hines' and Dizzy Gillespie's big bands and with Erroll Garner. Hartman is best remembered for his ...

, Dick Hyman

Richard Hyman (born March 8, 1927) is an American jazz pianist and composer. Over a 70-year career, he has worked as a pianist, organist, arranger, music director, electronic musician, and composer. He was named a National Endowment for the Ar ...

, Red Norvo

Red Norvo (born Kenneth Norville; March 31, 1908 – April 6, 1999) was an American musician, one of jazz's early vibraphonists, known as "Mr. Swing". He helped establish the xylophone, marimba, and vibraphone as jazz instruments. His reco ...

, Teddy Wilson

Theodore Shaw Wilson (November 24, 1912 – July 31, 1986) was an American jazz pianist. Described by critic Scott Yanow as "the definitive swing pianist", Wilson had a sophisticated, elegant style. His work was featured on the records of many ...

, and others. He also went back on the road, first with Diahann Carroll

Diahann Carroll (; born Carol Diann Johnson; July 17, 1935 – October 4, 2019) was an American actress, singer, model, and activist. She rose to prominence in some of the earliest major film studio, major studio films to feature black cas ...

for a tour in Paris in 1966, and later with Paul Anka

Paul Albert Anka (born July 30, 1941) is a Canadian-American singer, songwriter and actor. He is best known for his signature hit songs including " Diana", " Lonely Boy", " Put Your Head on My Shoulder", and "(You're) Having My Baby". Anka also ...

, Barbra Streisand

Barbara Joan "Barbra" Streisand (; born April 24, 1942) is an American singer, actress and director. With a career spanning over six decades, she has achieved success in multiple fields of entertainment, and is among the few performers awar ...

, Pearl Bailey

Pearl Mae Bailey (March 29, 1918 – August 17, 1990) was an American actress, singer and author. After appearing in vaudeville, she made her Broadway debut in ''St. Louis Woman'' in 1946. She received a Special Tony Award for the title role in ...

, and Bing Crosby

Harry Lillis "Bing" Crosby Jr. (May 3, 1903 – October 14, 1977) was an American singer, musician and actor. The first multimedia star, he was one of the most popular and influential musical artists of the 20th century worldwide. He was a ...

. From the 1960s through the 1990s he traveled extensively to Europe, Canada, South America, Japan, the Soviet Union, and the Middle East, while also appearing throughout the U.S.

In 1968, he began performing as a part of Professionals Unlimited (later renamed the New York Bass Violin Choir), a collective bass ensemble organized by Bill Lee that included Lisle Atkinson, Ron Carter

Ronald Levin Carter (born May 4, 1937) is an American jazz double bassist. His appearances on 2,221 recording sessions make him the most-recorded jazz bassist in history. He has won three Grammy awards, and is also a cellist who has recorded nu ...

, Richard Davis, Michael Fleming, Percy Heath, and Sam Jones. The group performed irregularly for a number of years and in 1980 released a self-titled album on the Strata-East label (SES-8003) containing material recorded between 1969 and 1975.

Hinton taught for nearly twenty years, as a visiting professor of jazz studies at Hunter College

Hunter College is a public university in New York City. It is one of the constituent colleges of the City University of New York and offers studies in more than one hundred undergraduate and postgraduate fields across five schools. It also admin ...

and Baruch College

Baruch College (officially the Bernard M. Baruch College) is a public college in New York City. It is a constituent college of the City University of New York system. Named for financier and statesman Bernard M. Baruch, the college operates unde ...

, first offering a jazz workshop at Hunter in late 1973. During this time he regularly appeared at jazz festivals, parties, and cruises; performing annually at Dick Gibson's jazz parties in Colorado, the Odessa and Midland jazz parties in Texas beginning in 1967, and Don and Sue Miller's jazz parties in Phoenix and Scottsdale.

He played at the first Newport Jazz Festival

The Newport Jazz Festival is an annual American multi-day jazz music festival held every summer in Newport, Rhode Island. Elaine Lorillard established the festival in 1954, and she and husband Louis Lorillard financed it for many years. They hir ...

in 1954 and was a regular at Newport and other jazz festivals produced by George Wein

George Wein (October 3, 1925 – September 13, 2021) was an American jazz promoter, pianist, and producer.

throughout the next four decades. He was a favorite at the Bern Jazz Festival in Switzerland, sponsored by Hans Zurbruegg and Marianne Gauer. In 1977, he recorded with Earl Hines

Earl Kenneth Hines, also known as Earl "Fatha" Hines (December 28, 1903 – April 22, 1983), was an American jazz pianist and bandleader. He was one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano and, according to one source, " ...

and Lionel Hampton

Lionel Leo Hampton (April 20, 1908 – August 31, 2002) was an American jazz vibraphonist, pianist, percussionist, and bandleader. Hampton worked with jazz musicians from Teddy Wilson, Benny Goodman, and Buddy Rich, to Charlie Parker, Charles ...

. For much of the 1980s and 1990s, Hinton was featured on jazz cruises organized by Hank O'Neal, then owner of Chiaroscuro Records

Chiaroscuro Records is a jazz record company and label founded by Hank O'Neal in 1970. The label's name comes from the Chiaroscuro, art term for the use of light and dark in a painting. O'Neal came up with the name via his friend and mentor Eddie ...

.

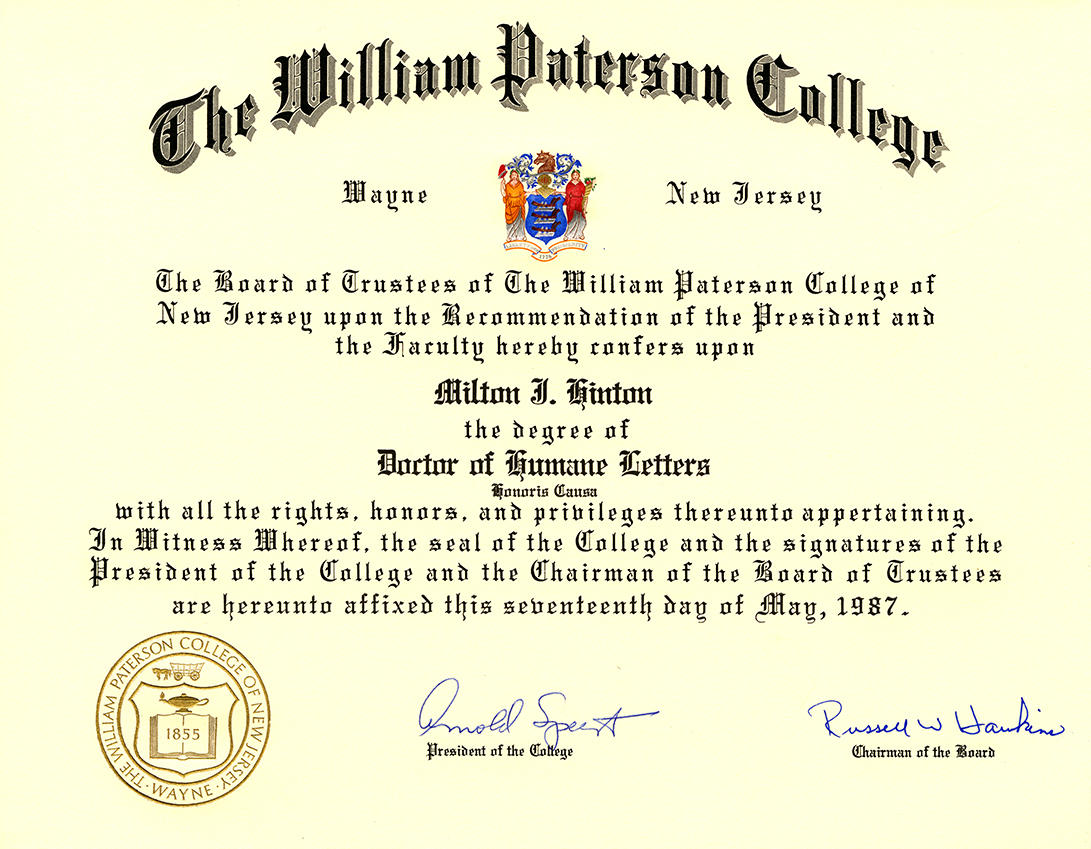

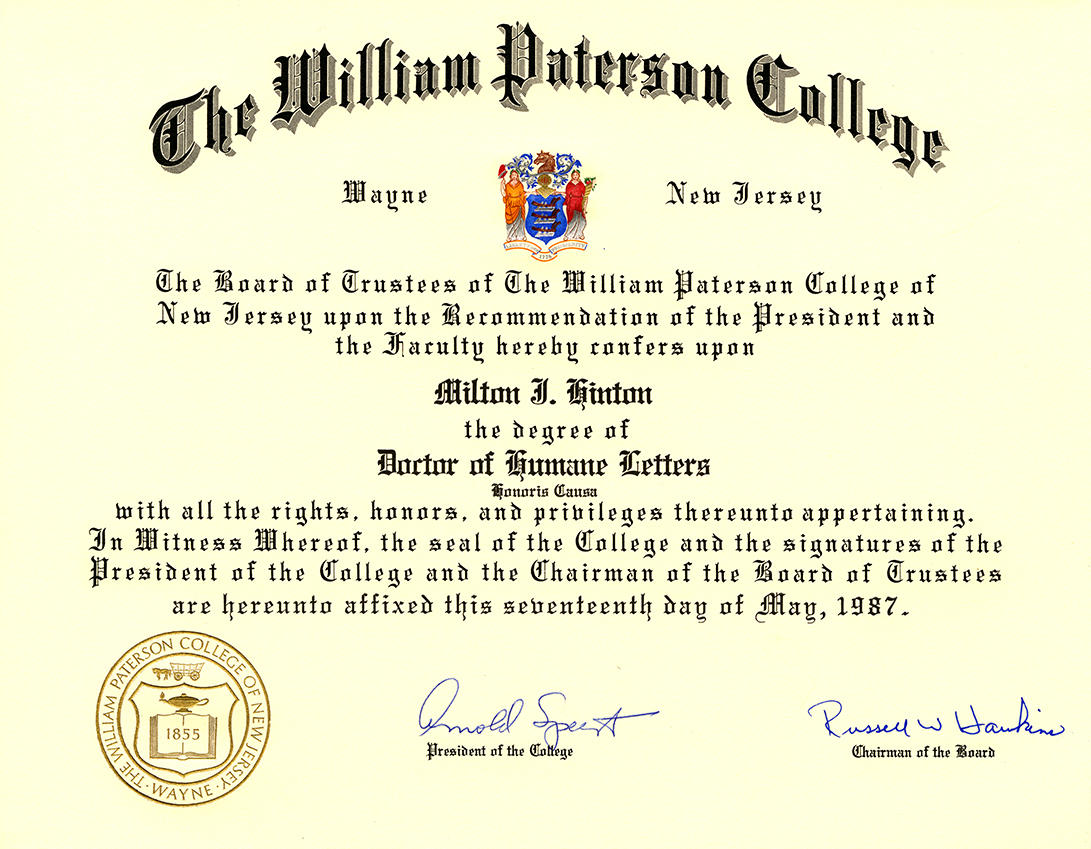

By the 1990s, he was revered as an elder statesman in jazz, and he was regularly honored with significant awards and accolades. He received honorary doctorates from

By the 1990s, he was revered as an elder statesman in jazz, and he was regularly honored with significant awards and accolades. He received honorary doctorates from William Paterson College

William Paterson University, officially William Paterson University of New Jersey (WPUNJ), is a public university in Wayne, New Jersey. It is part of New Jersey's public system of higher education.

Founded in 1855 and was named after American ...

, Skidmore College

Skidmore College is a private liberal arts college in Saratoga Springs, New York. Approximately 2,650 students are enrolled at Skidmore pursuing a Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science degree in one of more than 60 areas of study.

Histo ...

, Hamilton College

Hamilton College is a private liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York. It was founded as Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and was chartered as Hamilton College in 1812 in honor of inaugural trustee Alexander Hamilton, following ...

, DePaul University

DePaul University is a private, Catholic research university in Chicago, Illinois. Founded by the Vincentians in 1898, the university takes its name from the 17th-century French priest Saint Vincent de Paul. In 1998, it became the largest Ca ...

, Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

, the Berklee College of Music

Berklee College of Music is a private music college in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the largest independent college of contemporary music in the world. Known for the study of jazz and modern American music, it also offers college-level cours ...

, Fairfield University

Fairfield University is a private Jesuit university in Fairfield, Connecticut. It was founded by the Jesuits in 1942. In 2017, the university had about 4,100 full-time undergraduate students and 1,100 graduate students, including full-time a ...

, and Baruch College

Baruch College (officially the Bernard M. Baruch College) is a public college in New York City. It is a constituent college of the City University of New York system. Named for financier and statesman Bernard M. Baruch, the college operates unde ...

of the City University of New York. He won the Eubie Award from the New York Chapter of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences

The Recording Academy (formally the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences; abbreviated NARAS) is an American learned academy of musicians, producers, recording engineers, and other musical professionals. It is famous for its Grammy Aw ...

, the Living Treasure Award from the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

, and he was the first recipient of the Three Keys Award in Bern, Switzerland. In 1993, he was awarded the highly prestigious National Endowment for the Arts

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created in 1965 as an independent agency of the federal ...

Jazz Master Fellowship. He also contributed to the NEA's Jazz Oral History Program, continuing a longstanding practice of recording interviews with friends in his basement during extended visits. In 1996 he received a New York State Governor's Arts Award, in March 1998 he was awarded the Artist Achievement Award by the Governor of Mississippi, and in 2000 his name was installed on ASCAP's Wall of Fame.

In 1990, Hinton's 80th year, WRTI-FM in Philadelphia produced a series of twenty-eight short programs in which he chronicled his life. These were aired nationwide by more than one hundred fifty public radio stations and received a Gabriel Award that year as Best National Short Feature. In the same year George Wein produced a concert as a part of the JVC Jazz Festival in honor of Hinton's 80th birthday. Similar concerts were produced for his 85th and 90th birthdays. By 1996, he ceased performing on bass, due to a number of physical ailments, and he died at the age of 90 on December 19, 2000.

Musicianship

Hinton was broadly regarded as a consummate sideman, possessing a sensitivity for appropriately applying his formidable technique and his extensive harmonic knowledge to the performance at hand. He was equally adept atbowing

Bowing (also called stooping) is the act of lowering the torso and head as a social gesture in direction to another person or symbol. It is most prominent in Asian cultures but it is also typical of nobility and aristocracy in many European cou ...

, pizzicato

Pizzicato (, ; translated as "pinched", and sometimes roughly as "plucked") is a playing technique that involves plucking the strings of a string instrument. The exact technique varies somewhat depending on the type of instrument :

* On bowe ...

, and " slapping," a technique for which he first became famous while playing with the Cab Calloway Orchestra early in his career. He was also an accomplished sight-reader, a skill which he developed on the road with Calloway and honed during his several decades of studio work. As he described his technical diversity, "Working with Cab for sixteen years could have made me stale. You play the same music over and over, and after awhile you can do it in your sleep. Many guys liked it that way because it was easy. But when the band business got bad, they weren’t prepared to do anything else. On the other hand, I was able to work on radio and TV and get all kinds of record dates. In a real way, practicing and discipline paid off."

Hinton Photographic Collection

Hinton received his first camera, a 35mm Argus C3, on his 25th birthday in 1935. He later moved on to a Leica, then a Canon 35mm range-finder, and by the 1960s to a Nikon F. Between 1935 and 1999 Hinton took thousands of photographs, approximately 60,000 of which now comprise the Milton J. Hinton Photographic Collection, co-directed by David G. Berger and Holly Maxson. The Collection includes 35mm black and white negatives and color transparencies, reference and exhibition-quality prints, and photographs given to and collected by Hinton throughout his life. The work depicts an extensive range of jazz artists and popular performers in varied settings - on the road, in recording studios, at parties, and at home - over a period of six decades. Beginning in the early 1960s, Hinton and Berger worked together to organize the photographs and identify the subjects of the photos. In June 1981, Hinton had his first one-person photographic exhibition in Philadelphia, and since then items from the Collection have been featured in dozens of exhibits across the country and in Europe. Photographs from the Collection have also regularly appeared in periodicals, calendars, postcards, CD liner notes, films, and books. Hinton and Berger co-wrote ''Bass Line: The Stories and Photographs of Milt Hinton'' (Temple University Press, 1988), and with the addition of Holly Maxson, the three co-wrote ''OverTime: The Jazz Photographs of Milt Hinton'' (Pomegranate Art Books, 1991) and ''Playing the Changes: Milt Hinton’s Life in Stories and Photographs'' (Vanderbilt University Press, 2008). Notable documentary films that have drawn upon the Collection include ''The Long Night of Lady Day'' (Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan; April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed "Lady Day" by her friend and music partner, Lester Young, Holiday had an innovative influence on jazz music and pop s ...

), ''The Brute and the Beautiful'' (Ben Webster

Benjamin Francis Webster (March 27, 1909 – September 20, 1973) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist.

Career Early life and career

A native of Kansas City, Missouri, he studied violin, learned how to play blues on the piano from ...

), and ''Listen Up'' (Quincy Jones

Quincy Delight Jones Jr. (born March 14, 1933) is an American record producer, musician, songwriter, composer, arranger, and film and television producer. His career spans 70 years in the entertainment industry with a record of 80 Grammy Award n ...

). '' A Great Day in Harlem'', a 1994 documentary about Esquire's photographic shoot of jazz legends in 1958, features numerous photographs by Milt as well as a home movie shot by Mona. In late 2002 Berger and Maxson utilized the Collection along with a number of original interviews with Hinton's friends and colleagues to produce the documentary film ''Keeping Time: The Life, Music & Photographs of Milt Hinton''. It debuted at the London Film Festival

The BFI London Film Festival is an annual film festival founded in 1957 and held in the United Kingdom, running for two weeks in October with co-operation from the British Film Institute. It screens more than 300 films, documentaries and shor ...

, won the Audience Award at the Tribeca Film Festival

The Tribeca Festival is an annual film festival organized by Tribeca Productions. It takes place each spring in New York City, showcasing a diverse selection of film, episodic, talks, music, games, art, and immersive programming. Tribeca was f ...

in 2003, and has been shown at film festivals both domestically and abroad.

Hinton Collection at Oberlin College

In 1980, in honor of Hinton's 70th birthday, his friends and associates worked to create the Milton J. Hinton Scholarship Fund, which was used to help support the musical studies of a variety of bass students over the next 35 years. In 2014 the fund was transferred toOberlin College

Oberlin College is a private liberal arts college and conservatory of music in Oberlin, Ohio. It is the oldest coeducational liberal arts college in the United States and the second oldest continuously operating coeducational institute of highe ...

to provide scholarships to students attending the biennial Milton J. Hinton Summer Institute for Studio Bass, established at Oberlin College in 2014 and directed by Peter Dominguez, Professor of Jazz Studies and Double Bass at Oberlin. The institute is one component of a broader relationship between the Hinton Estate and Oberlin, which also includes:

* the acquisition by Oberlin of four of Hinton's basses, including the 18th-century bass that Hinton performed on for the majority of his career;

* the presence of the Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton Collection in the Oberlin Conservatory

The Oberlin Conservatory of Music is a private music conservatory in Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio. It was founded in 1865 and is the second oldest conservatory and oldest continually operating conservatory in the United States. It is one o ...

Library special collections, which comprises materials created or compiled by Milt and Mona Hinton over the course of their lives. The Collection includes date books, correspondence, financial records, artifacts, newspaper clippings, photographs, audio and moving image materials, and other ephemera that provide an unrivalled view of Hinton's life;

* an exhibition in 2014 at the Allen Memorial Art Museum

The Allen Memorial Art Museum (AMAM) is an art museum located in Oberlin, Ohio, and it is run by Oberlin College. Founded in 1917, the collection contains over 15,000 works of art.

Overview

The AMAM is primarily a teaching museum and is aimed a ...

at Oberlin College of 99 of Hinton's photographs, several dozen of which are now a part of the AMAM's permanent collection.

This relationship is in line with Hinton's longstanding goal to educate and inspire future generations of musicians. As he noted when discussing one of his own bass teachers, "For mitri Shmuklovsky passing on his skill and knowledge to the next generation was a solemn duty. It was a mission that went beyond his music. And looking back, I know his greatest gift was to teach me this strong sense of responsibility. It's the reason I've always tried to help young people. If someone wants to improve, if they have a sincere desire to learn, I've always tried to be there to give them whatever I can." The multifaceted relationship between the Hinton Estate and Oberlin College will ensure that Milt and Mona's legacy will be passed on to future generations.

Discography

*'' Everywhere ''and'' Beefsteak Charlie ''(1945) *'' And Say It Again ''(1947) *'' Just Plain Blues ''(1947) *'' If You Believed in Me ''(Staff 1947) *'' Meditation Jeffonese ''(Staff 1947) *'' Milt Hinton: East Coast Jazz 5 ''(1955) *'' Basses Loaded ''(1955) *'' The Rhythm Section ''(1956) *'' Percussion and Bass ''(Everest, 1960) withJo Jones

Jonathan David Samuel Jones (October 7, 1911 – September 3, 1985) was an American jazz drummer. A band leader and pioneer in jazz percussion, Jones anchored the Count Basie Orchestra rhythm section from 1934 to 1948. He was sometimes ...

*'' Here Swings the Judge ''(1964)

*'' Bassically with Blue ''(1976)

*'' The Trio ''(1977)

*'' Just the Two of Us ''(1981)

*'' The Judge’s Decision ''(1984)

*'' Back to Bass-ics ''(1984)

*'' Hayward and Hinton ''(1987)

*'' The Basement Tapes ''(1989)

*'' Old Man Time ''(1989)

*'' Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz with Guest Milt Hinton ''(1991)

*'' The Trio 1994 ''(1994)

*'' Laughing at Life ''(1994)

*'' The Judge at His Best: The Legendary Chiaroscuro Sessions, 1973-1995 ''(1995)

References

External links

Milt Hinton film clips

NAMM Oral History Library (1994)

Milt Hinton recordings

at the

Discography of American Historical Recordings

The Discography of American Historical Recordings (DAHR) is a database of master recordings made by American record companies during the 78rpm era. The DAHR provides some of these original recordings, free of charge, via audio streaming, along with ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hinton, Milt

1910 births

2000 deaths

Swing double-bassists

American jazz double-bassists

Male double-bassists

20th-century American photographers

Chiaroscuro Records artists

Musicians from Vicksburg, Mississippi

Jazz musicians from Mississippi

Jazz photographers

20th-century American musicians

Slap bassists (double bass)

20th-century double-bassists

20th-century American male musicians

American male jazz musicians

The Cab Calloway Orchestra members

Statesmen of Jazz members

Sackville Records artists