The military history of Mexico encompasses

armed conflicts

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regul ...

within that nation's territory, dating from before the arrival of Europeans in 1519 to the present era. Mexican

military history is replete with small-scale revolts, foreign invasions, civil wars, indigenous uprisings, and coups d'état by disgruntled military leaders. Mexico's colonial-era military was not established until the eighteenth century. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in the early sixteenth century, the Spanish crown did not establish on a standing military, but the crown responded to the external threat of a British invasion by creating a standing military for the first time following the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

(1756–63). The regular army units and militias had a short history when in the early 19th century, the unstable situation in Spain with the Napoleonic invasion gave rise to an insurgency for independence, propelled by militarily untrained, darker complected men fighting for the independence of Mexico. The

Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence ( es, Guerra de Independencia de México, links=no, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from Spain. It was not a single, co ...

(1810–21) saw royalist and insurgent armies battling to a stalemate in 1820. That stalemate ended with the royalist military officer turned insurgent,

Agustín de Iturbide persuading the guerrilla leader of the insurgency,

Vicente Guerrero

Vicente Ramón Guerrero (; baptized August 10, 1782 – February 14, 1831) was one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence. He fought against Spain for independence in the early 19th century, and later served as ...

, to join in a unified movement for independence, forming the

Army of the Three Guarantees

At the end of the Mexican War of Independence, the Army of the Three Guarantees ( es, Ejército Trigarante or ) was the name given to the army after the unification of the Spanish troops led by Agustín de Iturbide and the Mexican insurgent troo ...

. The royalist military had to decide whether to support newly independent Mexico. With the collapse of the Spanish state and the establishment of first a monarchy under Iturbide and then a republic, the state was a weak institution. The Roman Catholic Church and the military weathered independence better. Military men dominated Mexico's nineteenth-century history, most particularly General

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

, under whom the Mexican military were defeated by Texas insurgents for independence in 1836 and then the

U.S. invasion of Mexico (1846–48). With the overthrow of Santa Anna in 1855 and the installation of a government of political liberals, Mexico briefly had civilian heads of state. The

Liberal Reforms

The Liberal welfare reforms (1906–1914) were a series of acts of social legislation passed by the Liberal Party after the 1906 general election. They represent the emergence of the modern welfare state in the United Kingdom. The reforms demons ...

that were instituted by

Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec, he was the first indigenous pre ...

sought to curtail the power of the military and the church and wrote a new constitution in 1857 enshrining these principles. Conservatives comprised large landowners, the Catholic Church, and most of the regular army revolted against the Liberals, fighting a

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. The Conservative military lost on the battlefield. But Conservatives sought another solution, supporting the

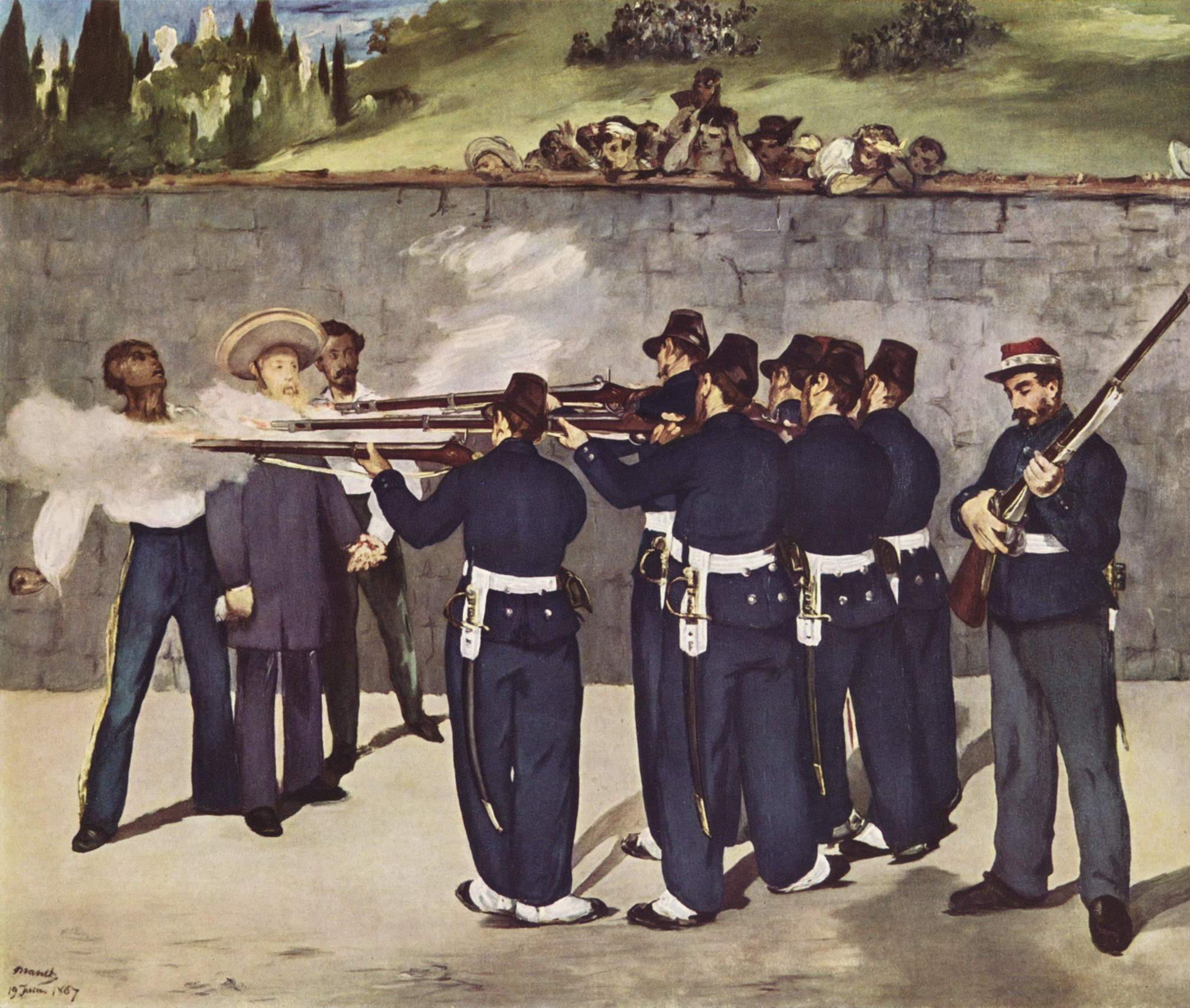

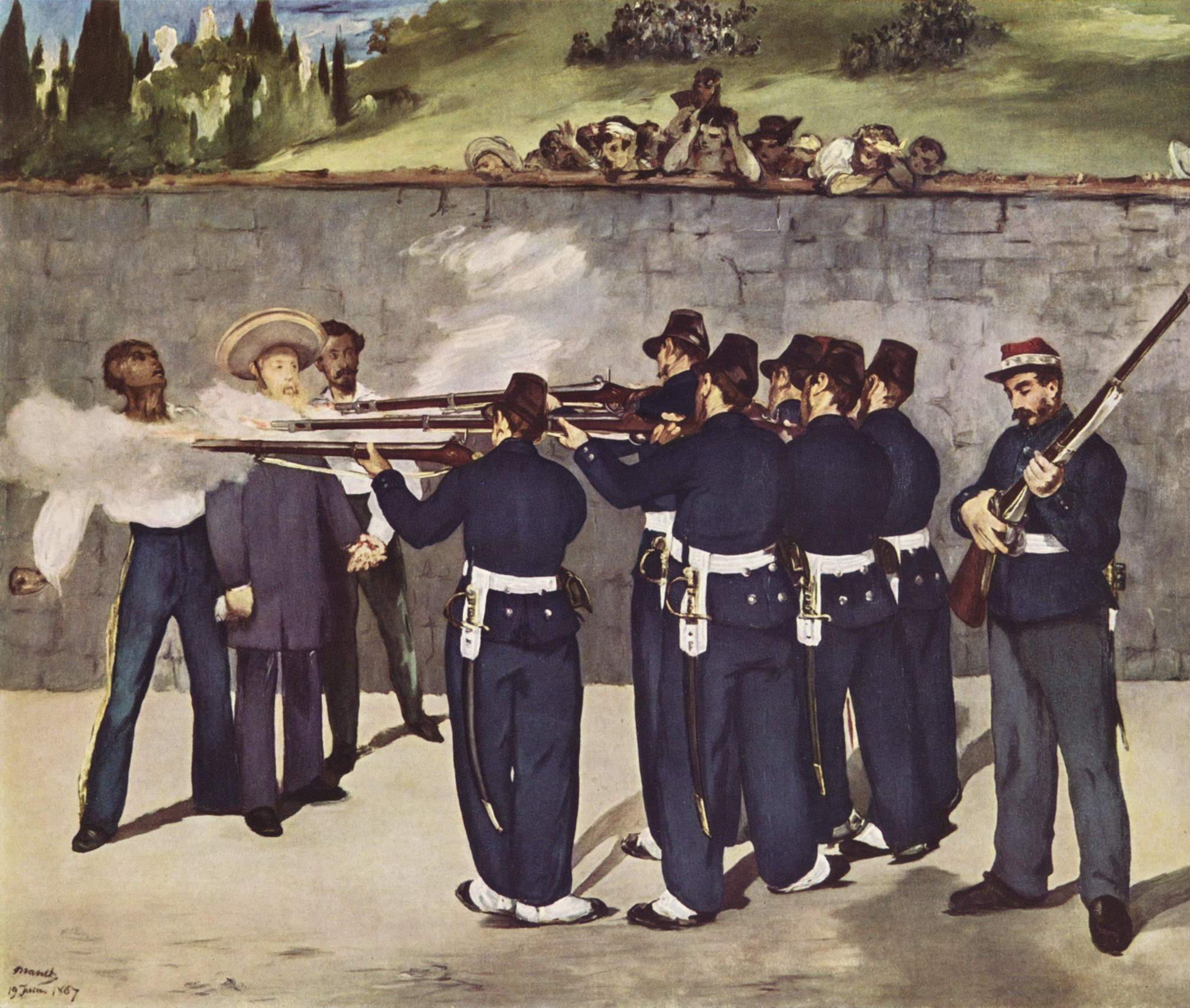

French intervention in Mexico (1862–65). The Mexican army loyal to the liberal republic were unable to stop the French army's invasion, briefly halting it in with a victory at Puebla on 5 May 1862. Mexican Conservatives supported the installation of Maximilian Hapsburg as Emperor of Mexico, propped up by the French and Mexican armies. With the military aid of the U.S. flowing to the republican government in exile of Juárez, the French withdrew its military supporting the monarchy and Maximilian was caught and executed. The Mexican army that emerged in the wake of the French Intervention was young and battle tested, not part of the military tradition dating to the colonial and early independence eras.

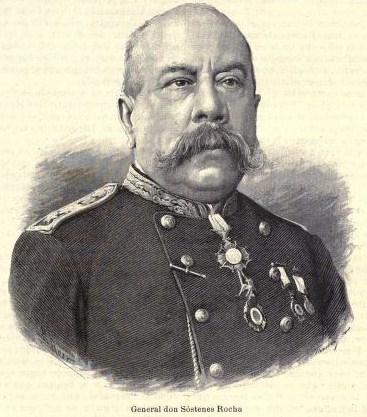

Liberal General

Porfirio Díaz was part of the new Mexican military, a hero of the Mexican victory over the French on

Cinco de Mayo

Cinco de Mayo ( in Mexico, Spanish for "Fifth of May") is a yearly celebration held on May 5, which commemorates the anniversary of Mexico's victory over the Second French Empire at the Battle of Puebla in 1862, led by General Ignacio Zaragoz ...

1862. He revolted against the civilian liberal government in 1876, and remained continuously in the presidency from 1880 to 1911. Over the course of his presidency, Díaz began professionalizing the army that had emerged. By the time he turned 80 years old in 1910, the Mexican military was an aging, largely ineffective fighting force. When revolts broke out in 1910–11 against his regime, a rebel forces scored decisive victories over the

Federal Army

The Mexican Federal Army ( es, Ejército Federal), also known as the Federales in popular culture, was the military of Mexico from 1876 to 1914 during the Porfiriato, the long rule of President Porfirio Díaz, and during the presidencies of Franci ...

in the opening chapter of the

Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). Díaz resigned in May 1911, but

Francisco I. Madero

Francisco Ignacio Madero González (; 30 October 1873 – 22 February 1913) was a Mexican businessman, revolutionary, writer and statesman, who became the 37th president of Mexico from 1911 until he was deposed in a coup d'etat in February 1 ...

, on whose political behalf rebels rose against Díaz, demobilized the rebel forces and kept the Federal Army in place. "This single decision cost

aderothe presidency and his life." Army General

Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 22 December 1854 – 13 January 1916) was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero wit ...

seized the presidency of Madero in 1913, with Madero murdered in the coup d'état. Civil war broke out in the wake of the coup. Huerta's Federal Army racked up one defeat after another by the revolutionary armies, with Huerta resigning in 1914. The Federal Army ceased to exist. A new generation of fighting men, most of whom with no formal military training but were natural soldiers, now fought against each other in a civil war of the winners. The

Constitutionalist Army

The Constitutional Army ( es, Ejército constitucionalista; also known as the Constitutionalist Army) was the army that fought against the Federal Army, and later, against the Villistas and Zapatistas during the Mexican Revolution. It was forme ...

under the civilian leadership of

Venustiano Carranza

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza (; 29 December 1859 – 21 May 1920) was a Mexican wealthy land owner and politician who was Governor of Coahuila when the constitutionally elected president Francisco I. Madero was overthrown in a Februa ...

and the military leadership of General

Alvaro Obregón were the victors in 1915. The revolutionary military men were to continue to dominate Mexico's postrevolutionary period, but the military men who became presidents of Mexico brought the military under civilian control, systematically reining in the power of the military and professionalizing the force. The Mexican military has been under civilian government control with no

President of Mexico

The president of Mexico ( es, link=no, Presidente de México), officially the president of the United Mexican States ( es, link=no, Presidente de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the head of state and head of government of Mexico. Under the Co ...

being military generals since 1946. The fact of Mexico's civilian control of the military is in contrast the situation in many other countries in Latin America.

Mexico stood among the

Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

and was one of two

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

n nations to send combat troops to serve in the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Recent developments in the Mexican military include their suppression of the 1994

Zapatista Army of National Liberation

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (, EZLN), often referred to as the Zapatistas (Mexican ), is a far-left political and militant group that controls a substantial amount of territory in Chiapas, the southernmost state of Mexico.

Since ...

in Chiapas, control of

narcotrafficking, and border security.

Pre-Hispanic era, before 1519

Before the arrival of Europeans in 1492, there were many large-scale civilizations in

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica ...

that had engaged in conquest of rival powers. As civilizations arose, traditional raiding to plunder resources evolved into full-scale conquests between 300 BCE and 150 BCE, with occupying forces that could direct tribute from the conquered to the conquerors. Conquest on a grand scale only occurred with the

Aztec Empire, which coalesced in the fifteenth century C.E., but smaller-scale conquests affected the rise and fall of civilizations before that. As early as

Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan (Spanish: ''Teotihuacán'') (; ) is an ancient Mesoamerican city located in a sub-valley of the Valley of Mexico, which is located in the State of Mexico, northeast of modern-day Mexico City. Teotihuacan is known today as t ...

and

Monte Albán

Monte Albán is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site in the Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán Municipality in the southern Mexico, Mexican state of Oaxaca (17.043° N, 96.767°W). The site is located on a low mountainous range rising above the plain i ...

, the first Mesoamerican states, there is evidence of local conquests of defensive walls around urban cores and conflicts resulting in large-scale sacrifice of warriors. There were cycles of conquests over many hundreds of years, resulting in the rise and decline of civilizations.

For many years, scholars depicted the Maya as peaceful, but there is ample evidence of Maya warfare in glyphic written texts and pictorials, as well as archeological evidence of "fortifications, mass graves, and militaristic iconography," indicating warfare's importance. In the 6th century, a

series of wars between the

Tikal

Tikal () (''Tik’al'' in modern Mayan orthography) is the ruin of an ancient city, which was likely to have been called Yax Mutal, found in a rainforest in Guatemala. It is one of the largest archeological sites and urban centers of the pre-C ...

and

Calakmul

Calakmul (; also Kalakmul and other less frequent variants) is a Maya archaeological site in the Mexican state of Campeche, deep in the jungles of the greater Petén Basin region. It is from the Guatemalan border. Calakmul was one of the l ...

erupted on the

Yucatán

Yucatán (, also , , ; yua, Yúukatan ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán,; yua, link=no, Xóot' Noj Lu'umil Yúukatan. is one of the 31 states which comprise the federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 106 separate mun ...

. The Mayan conflict also included vassal states in the

Petén Basin

The Petén Basin is a geographical subregion of Mesoamerica, primarily located in northern Guatemala within the Department of El Petén, and into Campeche state in southeastern Mexico.

During the Late Preclassic and Classic periods of pre-Colum ...

such as

Copan,

Dos Pilas

Dos Pilas is a Pre-Columbian site of the Maya civilization located in what is now the department of Petén, Guatemala. It dates to the Late Classic Period, and was founded by an offshoot of the dynasty of the great city of Tikal in AD ...

,

Naranjo

Naranjo is a Pre-Columbian Maya city in the Petén Basin region of Guatemala. It was occupied from about 500 BC to 950 AD, with its height in the Late Classic Period. The site is part of Yaxha-Nakum-Naranjo National Park. The city lies along the ...

,

Sacul,

Quiriguá

Quiriguá () is an ancient Maya archaeological site in the department of Izabal in south-eastern Guatemala. It is a medium-sized site covering approximately along the lower Motagua River, with the ceremonial center about from the north bank ...

, and briefly

Yaxchilan

Yaxchilan () is an ancient Maya city located on the bank of the Usumacinta River in the state of Chiapas, Mexico. In the Late Classic Period Yaxchilan was one of the most powerful Maya states along the course of the Usumacinta River, with Pi ...

had a role in initiating the first war. There is also evidence of conquests in the region of the Mixtecs, Zapotecs, and Purépecha (or Tarascans), which were not as extensive as the Aztec empire, but followed the same pattern on a smaller scale.

Prior to Spanish colonization, in the 15th century, several wars ensued between the Aztecs and several other native tribes. Alliances between the

Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

state and

Texcoco had become central to these pre colonial wars. Several of these conflicts were evolved to an organized warfare, known as the

Flower wars

A flower war or flowery war ( nah, xōchiyāōyōtl, es, guerra florida) was a ritual war fought intermittently between the Aztec Triple Alliance and its enemies from the "mid-1450s to the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519." Enemies included th ...

. In the Flower wars the primary objective was to injure or capture the enemy, rather than killing as in Western warfare. Prisoners-of-war were ritually

sacrificed to

Aztec gods

Aztec mythology is the body or collection of myths of the Aztec civilization of Central Mexico. The Aztecs were Nahuatl-speaking groups living in central Mexico and much of their mythology is similar to that of other Mesoamerican cultures. Accor ...

.

Cannibalism was also a center feature to this type of warfare. Historical accounts such as that of

Juan Bautista de Pomar Juan Bautista (de) Pomar (c. 1535 – after 1601) was a mestizo descendant of the rulers of prehispanic Texcoco, a historian and writer on prehispanic Aztec history. He is the author of two major works. His ''Relación de Texcoco'' was written ...

state that small pieces of meat were offered as gifts to important people in exchange for presents and slaves, but it was rarely eaten, since they considered it had no value; instead it was replaced by turkey, or just thrown away.

Perhaps the most famous of the Native Mexican states is the

Aztec Empire. In the 13th and 14th centuries, around

Lake Texcoco

Lake Texcoco ( es, Lago de Texcoco) was a natural lake within the "Anahuac" or Valley of Mexico. Lake Texcoco is best known as where the Aztecs built the city of Tenochtitlan, which was located on an island within the lake. After the Spanish con ...

in the

Anahuac Valley

The Valley of Mexico ( es, Valle de México) is a highlands plateau in central Mexico roughly coterminous with present-day Mexico City and the eastern half of the State of Mexico. Surrounded by mountains and volcanoes, the Valley of Mexico w ...

, the most powerful of these city states were

Culhuacan to the south, and

Azcapotzalco

Azcapotzalco ( nci, Āzcapōtzalco , , from '' āzcapōtzalli'' “anthill” + '' -co'' “place”; literally, “In the place of the anthills”) is a borough (''demarcación territorial'') in Mexico City. Azcapotzalco is in the northwestern p ...

to the west. Between them, they controlled the whole Lake Texcoco area.

The Aztecs hired themselves out as

mercenaries in wars between the

Nahuas

The Nahuas () are a group of the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They comprise the largest indigenous group in Mexico and second largest in El Salvador. The Mexica (Aztecs) were of Nahua ethnicity, a ...

, breaking the balance of power between city states. Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and

Tlacopan

Tlacopan, also called Tacuba, was a Tepanec / Mexica altepetl on the western shore of Lake Texcoco. The site is today the neighborhood of Tacuba, in Mexico City.

Etymology

The name comes from Classical Nahuatl ''tlacōtl'', "stem" or "rod" and ...

formed a "Triple Alliance" that came to dominate the

Valley of Mexico

The Valley of Mexico ( es, Valle de México) is a highlands plateau in central Mexico roughly coterminous with present-day Mexico City and the eastern half of the State of Mexico. Surrounded by mountains and volcanoes, the Valley of Mexico w ...

, and then extended its power beyond.

Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

, the traditional capital of the Aztec Empire, gradually became the dominant power in the alliance.

The

Chichimeca

Chichimeca () is the name that the Nahua peoples of Mexico generically applied to nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples who were established in present-day Bajio region of Mexico. Chichimeca carried the meaning as the Roman term "barbarian" that d ...

, a wide range of

nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic groups that inhabited the north of modern-day Mexico, were never conquered by the Aztecs.

Spanish conquest of Mexico

The two-year

Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, also known as the Conquest of Mexico or the Spanish-Aztec War (1519–21), was one of the primary events in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. There are multiple 16th-century narratives of the eve ...

(1519–1521) is the most famous episode of Spanish conquest history. It is documented in the sixteenth century by both Spaniards, their indigenous allies, and indigenous opponents shortly after the events. With arrival of Spaniards in the Caribbean in 1492, they developed patterns of conquest and settlement. From the Caribbean, they went on expeditions (''entradas'') of exploration, trade, conquest, and settlement. The Spanish crown issued a license for a particular leader to head an expedition, a mature man with wealth, social standing, and ambition to better his position. Explorers probed Mexico's east coast, with

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba Francisco Hernández de Córdoba may refer to:

* Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (Yucatán conquistador) (died 1517)

* Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (founder of Nicaragua) (died 1526)

{{hndis, name=Hernandez de Cordoba, Francisco ...

exploring southeast Mexico in 1517, followed by

Juan de Grijalva

Juan de Grijalva (; born c. 1490 in Cuéllar, Crown of Castile – 21 January 1527 in Honduras) was a Spanish conquistador, and a relative of Diego Velázquez.Diaz, B., 1963, The Conquest of New Spain, London: Penguin Books, He went to Hispanio ...

in 1518. The most important

Conquistadores was

Hernán Cortés, a settler in Cuba who was well-connected locally. He received a license to lead an expedition of exploration only. As was standard practice for an expedition, those joining it brought their own weapons and armor, and if wealthy enough, a horse. If an entrada of conquest was successful, participants would receive shares of the spoils, with each man receiving one share, and if he was a horseman, an additional share. These expeditions were not organized armies of salaried troops funded by the crown, but groups of settlers turned bands of men in combat or soldiers of fortune, who joined with the expectation that their valor and skill in combat would be rewarded. The term "soldier" was not used by participants themselves. The leader was often called "captain,", but this was not a military rank. Cortés did not want to be restricted by the license limiting him solely to exploration of Mexico's coast, and left Cuba before officials realized his ambition. For that reason, once the Spanish would-be conquerors landed on the mainland, they needed to find way to constitute themselves as a legal entity. They did so by founding the town of Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz (today's

Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

), and constituting themselves as the city council. They chose Hernán Cortés as their captain.

The conquest of Mexico unfolded along established principles worked out by the Spanish in their twenty years of settlement and expeditions around the Caribbean. Seizing the leader of an indigenous group during a friendly parley was typical, quickly giving Spaniards the advantage. Some groups capitulated immediately and of those some became active allies of the Spanish. The small group of Spaniards realized immediately that the mainland had indigenous populations that were far denser and hierarchically organized societies. The

Aztec Empire, the dominant power in central Mexico at the time of European Contact, had conquered indigenous city-states, many of which were chafing under Aztec rule and sought independent status themselves. Cortés quickly realized that he needed indigenous allies for successful conquest and found various indigenous city-states willing to take their chances with these newcomers. From the Spaniards' point of view, the standard strategy of divide-and-conquer was a workable—and winning—strategy. From the indigenous allies' point of view, they formed this alliance with the expectation of bettering their own circumstances. The most important of these allies was the city-state (

Nahuatl: ''altepetl'') of

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 60 municipaliti ...

, which the Aztecs had been unable to conquer. The Spanish benefited from another type of ally, an indigenous woman,

Malinche or more politely called Doña Marina, who became Cortés's cultural translator. Sent into slavery as a child by her family, she was given as a gift to the Spaniards by a Maya indigenous ally. Malinche was a native speaker of language of the Aztecs,

Nahuatl and had learned a Maya language in captivity. She quickly became essential in the Spaniards' ability to negotiate with potential allies and advise the Spaniards about indigenous military strategy and tactics. In sixteenth-century indigenous pictorial accounts of the conquest, such as

Codex Azcatitlan

The Codex Azcatitlan is an Aztec codex detailing the history of the Mexica and their migration journey from Aztlán to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. The exact date when the codex was produced is unknown, but scholars speculate it was ...

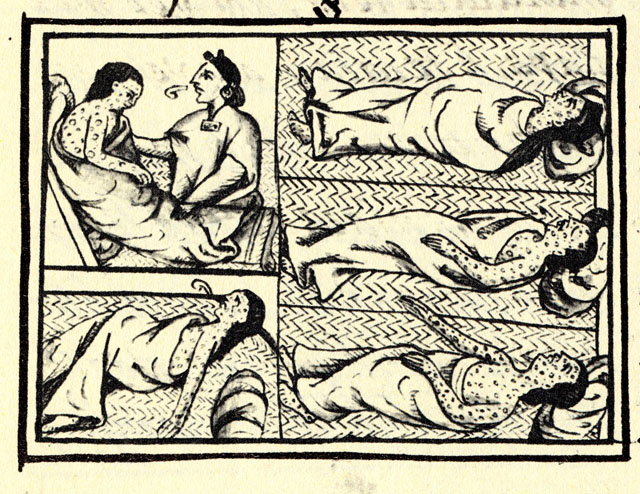

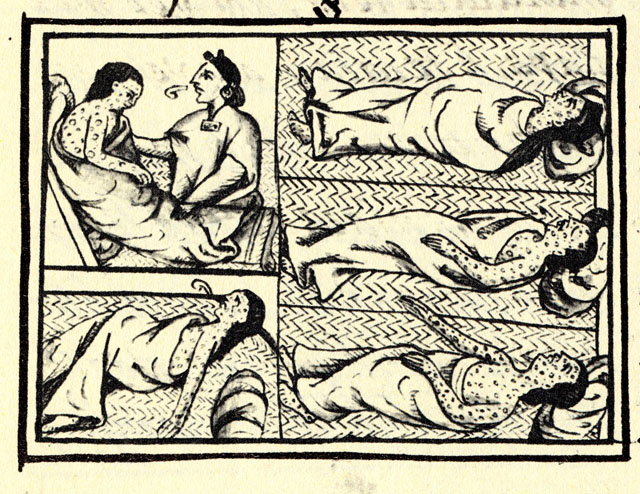

, Malinche is shown as an out-sized figure in a leadership position. With their indigenous allies, the Spanish defeated the Aztec empire in a two-year long struggle. They were aided by the outbreak of a smallpox

epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious ...

unintentionally introduced to the mainland by a black slave; the disease disproportionately affected the indigenous populations, since they had no immunity to it.

The Spaniards surrounded and laid siege to the inhabitants of the Aztec's island capital

Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

, bringing about the Aztecs' total defeat in 1521. Despite their metal weapons, horses, dogs, cannons, and thousands of indigenous allies, the Spanish were unable to subdue the Mexica for seven full months. It was one of the longest continuous sieges in world history.

Several factors contributed to Spanish victory against the Aztecs. Their alliances with indigenous city-states discontented with Aztec rule were crucial to their victory, vastly swelling the number of warriors that could be mobilized in combat. The Aztec empire was fragile politically and militarily, once it became clear that they were beatable. Spanish military technology was superior in many ways, with horses giving Spaniards the advantage in open-field warfare. Iron and steel weapons and harquebuses provided advantages. The Spanish were further aided in their conquest by the

Old World disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

s (primarily

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

) they brought with them, to which the natives had no immunity, and which became

pandemic, killing large portions of the native population.

Colonial-era control without a standing military

Not until the Spanish empire was by foreign conquest in the eighteenth century did the Spanish crown establish a standing military. Conquests of the central Mexican indigenous civilizations was basically final in the sixteenth century, with the conquest of the Maya region more protracted. Spaniards who had participated in the conquest of central Mexico were rewarded with grants of labor and tribute from city-states which was facilitated by indigenous nobles. The institution of

encomienda required the awardees to keep "their Indians" peaceful and to promote their conversion to Christianity. The status of indigenous nobles was recognized by the Spanish crown and were granted the right to carry Spanish arms and ride on horseback, prohibited to commoners. In general, once conquered, the indigenous were incorporated into the Spanish colonial empire as vassals of the crown. There were few rebellions. An exception was the 1541

Mixtón war

The Mixtón War (1540-1542) was a rebellion by the Caxcan people of northwestern Mexico against the Spanish conquerors. The war was named after Mixtón, a hill in Zacatecas which served as an Indigenous stronghold.

The Caxcanes

Although othe ...

, where an uprising in what is now

Jalisco was suppressed by armed Spaniards and their loyal Tlaxcalan allies led by the highest Spanish administrator, the

viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

, Don

Antonio de Mendoza

Antonio de Mendoza y Pacheco (, ; 1495 – 21 July 1552) was a Spanish colonial administrator who was the first Viceroy of New Spain, serving from 14 November 1535 to 25 November 1550, and the third Viceroy of Peru, from 23 September 1551 ...

.

The indigenous groups in northern Mexico, collectively called

Chichimeca

Chichimeca () is the name that the Nahua peoples of Mexico generically applied to nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples who were established in present-day Bajio region of Mexico. Chichimeca carried the meaning as the Roman term "barbarian" that d ...

by the Aztecs became fierce and effective warriors against the Spanish once they acquired horses. With the expansion of Spanish exploration northward, these northern indigenous groups were not quickly or permanently subdued and block northern settlement until the discovery of large deposits of silver in

Zacatecas

, image_map = Zacatecas in Mexico (location map scheme).svg

, map_caption = State of Zacatecas within Mexico

, coordinates =

, coor_pinpoint =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type ...

. The high value of the silver mines and the need to secure the mining zone and the overland routes to transport silver south and supplies north meant the crown had to create a viable solution. A fifty-year long conflict, the

Chichimeca War

The Chichimeca War (1550–90) was a military conflict between the Spanish Empire and the Chichimeca Confederation established in the territories today known as the Central Mexican Plateau, called by the Conquistadores La Gran Chichimeca. Th ...

initially used the construction of

presidio

A presidio ( en, jail, fortification) was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire around between 16th and 18th centuries in areas in condition of their control or influence. The presidios of Spanish Philippines in particular, were cen ...

s to place soldiers permanently to protect the trunk lines. The Spanish "war of blood and fire" (''guerra de sangre y fuego'') was not effective enough and the Spanish turned to a strategy of "peace by purchase," followed by peaceful Christian evangelization of the indigenous. The frontier institutions of the presidio and the Christian mission complex became standard crown-supported ways to establish and maintain Spanish control in northern Mexico.

Establishment of a standing military, 18th c.

In the eighteenth century, the rise of rival European empires, particularly the British, threatened Spanish control of its lucrative overseas colonies. The 1762 British capture of

Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center. , Cuba and

Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

, the Philippines in the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

, prompted the Spanish crown to protect its colony of

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

by establishing a standing military. The external military threat was real, but in order to establish a military, Spanish and colonial elites had to overcome the fear of arming large numbers of lower-class non-whites. Given the small number of Spaniards available for military service and the large-scale external threat, there was no alternative to enlisting dark-skinned plebeians into part-time militias or a standing military. Indians were exempt from military service, but mixed-race

casta men were part of companies and there were some light- and dark-skinned

Afro-Mexican

Afro-Mexicans ( es, afromexicanos), also known as Black Mexicans ( es, mexicanos negros), are Mexicans who have heritage from sub-Saharan Africa and identify as such. As a single population, Afro-Mexicans include individuals descended from both ...

companies.

In the eighteenth century, the

Bourbon regime had introduced practices and reforms that systematically excluded elite American-born Spaniards from holding high civil or ecclesiastical office. There were fewer visible routes to status and privilege for these men. The establishment of the military provided such a route to recognition with the establishment of the

''fuero militar'', the privilege of being tried before a military rather than a civilian or criminal court, no matter what the offense. Viceroy Branciforte saw the fuero as a way of attracting wealthy American-born Spaniards to the military. Many of them donated large sums to create militias, with themselves as the ranking member, funding the purchase of arms, uniforms, and equipment. The local city councils

cabildos, nominated wealthy and socially prominent estate owners to be officers. What was unusual about the fuero militar from fueros of other groups was its extension to enlisted men and not just officers. The crown was concerned that such an extension to the lower ranks would the military a haven for miscreants.

Mexican War of Independence, 1810–1821

Events in the late 18th and early 19th centuries may be best summed as to have caused the fight against the Spanish. The ''

Criollos

In Hispanic America, criollo () is a term used originally to describe people of Spanish descent born in the colonies. In different Latin American countries the word has come to have different meanings, sometimes referring to the local-born majo ...

'', or American-born rather than Spaniards born in Spain (''Peninsulares'') had since the eighteen-century

Bourbon reforms

The Bourbon Reforms ( es, Reformas Borbónicas) consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Monarchy, Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of ...

been passed over for high posts in the civil and ecclesiastical structures; mixed-race

castas and indigenous peoples were legally lower in standing with unequal access to justice and usually lived in dire poverty. Spain's debility at the start of the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, and an inability to control itself

during its French occupation allowed several creole rebels to take advantage of the situation. Thus, leaders such as

Simón Bolívar,

José de San Martín

José Francisco de San Martín y Matorras (25 February 177817 August 1850), known simply as José de San Martín () or '' the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru'', was an Argentine general and the primary leader of the southern and centr ...

and

Antonio José de Sucre

Antonio José de Sucre y Alcalá (; 3 February 1795 – 4 June 1830), known as the "Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho" ( en, "Grand Marshal of Ayacucho"), was a Venezuelan independence leader who served as the president of Peru and as the second p ...

started revolutions throughout

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

to attain

independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

.

Mexico's

War of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List o ...

was less straightforward than the independence movements in most of Spanish South America. In 1808 Peninsulares in Mexico City ousted the viceroy, Iturrigaray, whom they considered too accommodating to creoles' demands. In 1810 a conspiracy of creoles for independence, plotted a rising against the royal government. When it was discovered, secular priest

Miguel Hidalgo

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla y Gallaga Mandarte Villaseñor (8 May 1753 – 30 July 1811), more commonly known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or Miguel Hidalgo (), was a Catholic priest, leader of the Mexican ...

called to his rural parishioners in the pueblo of Dolores for an uprising. The

Grito de Dolores

A ''grito'' or ''grito mexicano'' (, Spanish for "shout") is a common Mexican interjection, used as an expression.

Characteristics

This interjection is similar to the ''yahoo'' or '' yeehaw'' of the American cowboy during a hoedown, with added ...

that had denounced bad government touched off a massive uprising by mixed-race castas and indigenous tens of thousands of unorganized followers of Hidalgo. Creole elites who had toyed with the idea of political independence rapidly withdrew their support as their property and persons were targeted for violence.

The viceroy was slow to mobilize a military response to the Hidalgo revolt. Troops had been moved to Mexico City and units suspected of sympathies for independence were demobilized. The followers of Hidalgo rapidly took

San Miguel,

Guanajuato, Valladolid, and

Guadalajara, to the north and northwest of Mexico City. Some regional forces were caught up with the rebels in Querétaro and Michoacán. "Militiamen with their arms and wearing their Spanish uniforms marched with Hidalgo's masses. Some criollo officers, mostly provincial sublieutenants, lieutenants, and captains, attempted to discipline and organize the inchoate popular movement." The larger story, however, was that the vast majority of the royalist army remained loyal to the crown. When

Félix Calleja took command of the royal forces, he won a series of decisive victories against Hidalgo's insurgent forces.

The large-scale insurgency for independence in the north was suppressed, but insurgents in southern Mexico, particularly under

Vicente Guerrero

Vicente Ramón Guerrero (; baptized August 10, 1782 – February 14, 1831) was one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence. He fought against Spain for independence in the early 19th century, and later served as ...

turned to guerrilla warfare. Royal troops were less able to win decisive victories and the insurgency remained at a stalemale until the end of the decade. The political situation changed in Spain with a major impact on the situation in New Spain. Spanish liberals staged a coup against the absolutist monarch and for

three years sought to implement the liberal constitution of 1812. In Mexico, conservatives saw this turn of events as highly unsettling and considered political independence now an option. Royalist army officer Agustín de Iturbide drafted the

Plan of Iguala

The Plan of Iguala, also known as The Plan of the Three Guarantees ("Plan Trigarante") or Act of Independence of North America, was a revolutionary proclamation promulgated on 24 February 1821, in the final stage of the Mexican War of Independenc ...

, calling for political independence, a

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, equality, and Catholicism as its core principles. He persuaded insurgent leader Guerrero to join them. Together they formed the

Army of the Three Guarantees

At the end of the Mexican War of Independence, the Army of the Three Guarantees ( es, Ejército Trigarante or ) was the name given to the army after the unification of the Spanish troops led by Agustín de Iturbide and the Mexican insurgent troo ...

, which triumphantly marched into Mexico City in 1821. Independence from Spain was first proclaimed by Hidalgo in 1810, but it was not a political reality until 1821, when the last Spanish viceroy

Juan O'Donojú signed the

Treaty of Córdoba

The Treaty of Córdoba established Mexican independence from Spain at the conclusion of the Mexican War of Independence. It was signed on August 24, 1821 in Córdoba, Veracruz, Mexico. The signatories were the head of the Army of the Three Guara ...

, 16 September in

Córdoba, Veracruz

Córdoba, known officially as Heroica Córdoba, is a city and the seat of the municipality of the same name in the Mexican state of Veracruz. It was founded in 1618.

The city is composed of 15 barrios (neighborhoods) bounded to the north by Ixhua ...

.

File:Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla.png, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, "father of Mexican independence" for his 1810 insurgency

File:Retrato del excelentísimo señor don José María Morelos.png, Father José María Morelos, Mexican insurgent. 1812 portrait, now in Chapultepec Castle

Chapultepec Castle ( es, Castillo de Chapultepec) is located on top of Chapultepec Hill in Mexico City's Chapultepec park. The name ''Chapultepec'' is the Nahuatl word ''chapoltepēc'' which means "on the hill of the grasshopper". The castle has s ...

in the Museo Nacional de Historia.

File:Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña.png, Vicente Guerrero, insurgent general who signed onto the Plan of Iguala

File:Agustin de Iturbide Oleo Primitivo Miranda.png, Agustín de Iturbide, royalist officer turned insurgent leader. Author of the Plan of Iguala, Emperor Agustín I, forced to abdicate and later shot returning to Mexico

File:Oleo Guadalupe Victoria.PNG, General Guadalupe Victoria

Guadalupe Victoria (; 29 September 178621 March 1843), born José Miguel Ramón Adaucto Fernández y Félix, was a Mexican general and political leader who fought for independence against the Spanish Empire in the Mexican War of Independence. He ...

, first president of the Republic of Mexico

File:Santaanna1.JPG, Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

came to dominate Mexico for thirty years

First Mexican Empire and its overthrow, 1822–1823

In 1821 Agustín de Iturbide, a former Spanish general who switched sides to fight for Mexican independence, proclaimed himself emperor – officially as a temporary measure until a member of European royalty could be persuaded to become monarch of Mexico (see

First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire ( es, Imperio Mexicano, ) was a constitutional monarchy, the first independent government of Mexico and the only former colony of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after independence. It is one of the few modern-era, ...

for more information). A revolt against Iturbide in 1823 established the United Mexican States. In 1824

Guadalupe Victoria

Guadalupe Victoria (; 29 September 178621 March 1843), born José Miguel Ramón Adaucto Fernández y Félix, was a Mexican general and political leader who fought for independence against the Spanish Empire in the Mexican War of Independence. He ...

became the first president of the new country; his given name was actually Félix Fernández but he chose his new name for symbolic significance: Guadalupe to give thanks for the protection of

Our Lady of Guadalupe

Our Lady of Guadalupe ( es, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe ( es, Virgen de Guadalupe), is a Catholic title of Mary, mother of Jesus associated with a series of five Marian apparitions, which are believed t ...

, and ''Victoria'', which means Victory.

The ''

Plan de Casa Mata'' was formulated to abolish the

monarchy

A monarchy is a government#Forms, form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The legitimacy (political)#monarchy, political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restric ...

and to establish a

republic. In December 1822,

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

and

Guadalupe Victoria

Guadalupe Victoria (; 29 September 178621 March 1843), born José Miguel Ramón Adaucto Fernández y Félix, was a Mexican general and political leader who fought for independence against the Spanish Empire in the Mexican War of Independence. He ...

signed the ''Plan de Casa Mata'' on February 1, 1823, as a start of their efforts to overthrow

Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Agustín de Iturbide.

In May 1822, using military riots and pressures, Iturbide had taken the power and designated himself

Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

, initiating his government in fight with the Congress. Later he dissolved Congress and ordered opposing deputies to jail.

Several insurrections arose in the provinces and were later crushed by the army.

Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

was spared due to an agreement between Antonio López de Santa Anna and the rebel general Echávarri.

By agreement of both heads the Plan de Casa Mata was proclaimed on February 1, 1823. This plan did not recognize the Empire and requested the meeting of a new

Constituent Congress

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

. The insurrectionists sent their proposal to the provincial delegations and requested their adhesion to the plan. In the course of only six weeks the Plan de Casa Mata had arrived at remote places, like

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, and almost all the provinces had been united to the plan.

Early Republic

Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico, 1821–29

Spain did not reconcile itself to the loss of its valuable colony, refusing to acknowledge the

Treaty of Cordoba. Spain initiated military efforts to reconquer it during the 1820s. A criollo military officer who emerged as a hero of Mexican nationalism was

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

. In defending Mexico's independence, Santa Anna lost a leg in battle, which became the visible symbol of his sacrifices for the nation. He capitalized on this reputation to forward his political career. The early post-independence period is often called the Age of Santa Anna.

The attempts to reconquer Mexico were not successful, but not until 28 December 1836 did Spain recognize the independence of Mexico. The

Santa María–Calatrava Treaty

The Santa María–Calatrava Treaty (historically known as the definitive treaty of peace and friendship between Mexico and Spain) was a treaty between Mexico and Spain recognizing the independence of Mexico on December 28, 1836. It ended the tens ...

was signed in Madrid by the Mexican Commissioner Miguel Santa María and the Spanish state minister José María Calatrava.

Pastry War, 1838

In 1838 a French

pastry

Pastry is baked food made with a dough of flour, water and shortening (solid fats, including butter or lard) that may be savoury or sweetened. Sweetened pastries are often described as '' bakers' confectionery''. The word "pastries" sugges ...

cook, Monsieur Remontel, claimed his shop in the

Tacubaya

Tacubaya is a working-class area of west-central Mexico City, in the borough of Miguel Hidalgo, consisting of the '' colonia'' Tacubaya proper and adjacent areas in other colonias, with San Miguel Chapultepec sección II, Observatorio, Daniel Ga ...

district of Mexico City had been ruined by looting Mexican officers in 1828. He appealed to

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

's King

Louis-Philippe

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, he distinguished himself commanding troops during the Revolutionary Wa ...

(1773–1850). Coming to its citizen's aid, France demanded 600,000 pesos in damages. This amount was extremely high when compared to an average workman's daily pay, which was about one peso. In addition to this amount, Mexico had defaulted on millions of dollars worth of loans from France. Diplomat Baron Beffaudis gave Mexico an ultimatum of paying, or the French would demand satisfaction. When the payment was not forthcoming from president

Anastasio Bustamante

Anastasio Bustamante y Oseguera (; 27 July 1780 – 6 February 1853) was a Mexican physician, general, and politician who served as president of Mexico three times. He participated in the Mexican War of Independence initially as a royalist befo ...

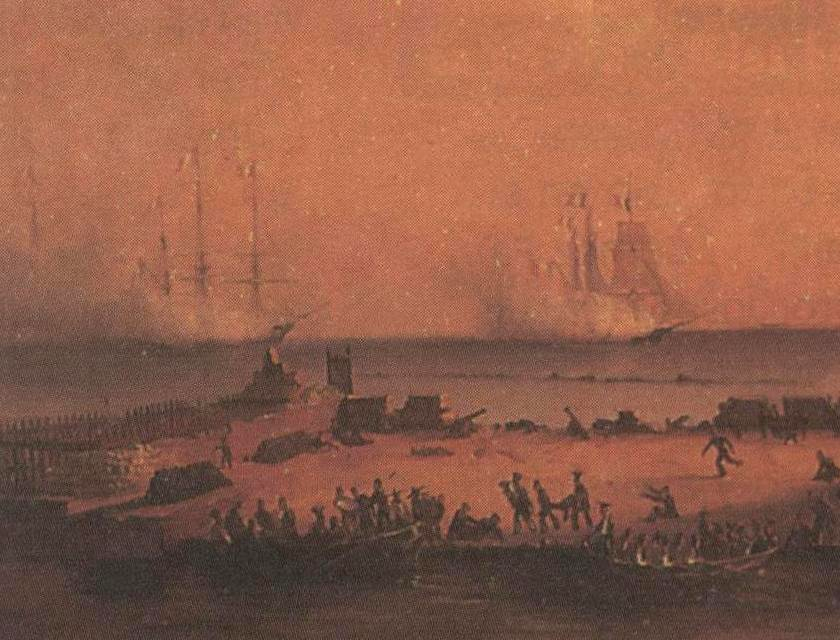

(1780–1853), the king sent a fleet under Rear Admiral

Charles Baudin

Charles Baudin (21 July 1784 – 7 June 1854), was a French admiral, whose naval service extended from the First Empire through the early days of the Second Empire.

Biography

From 1800, Baudin served as a midshipman on ''Géographe'' and took ...

to declare a blockade of all Mexican ports from

Yucatán

Yucatán (, also , , ; yua, Yúukatan ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán,; yua, link=no, Xóot' Noj Lu'umil Yúukatan. is one of the 31 states which comprise the federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 106 separate mun ...

to the

Rio Grande, to bombard the coastal fortress of

San Juan de Ulúa

San Juan de Ulúa, also known as Castle of San Juan de Ulúa, is a large complex of fortresses, prisons and one former palace on an island of the same name in the Gulf of Mexico overlooking the seaport of Veracruz, Mexico. Juan de Grijalva's ...

, and to seize the port of Veracruz. Virtually the entire Mexican Navy was captured at Veracruz by December 1838. Mexico declared war on France. The French withdrew in 1839.

Texas Revolution, 1835–1836

The Texan struggle for independence marked the beginning of a conflict with the modern

U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

of

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, and its independence from Mexico and the state of

Coahuila y Tejas

Coahuila y Tejas, officially the Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila y Tejas (), was one of the constituent states of the newly established United Mexican States under its 1824 Constitution.

It had two capitals: first Saltillo (1822–1825) f ...

. Battles associated with the conflict with Texas include

the Alamo, where federal troops led by

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

defeated the Texans, and the

Battle of San Jacinto

The Battle of San Jacinto ( es, Batalla de San Jacinto), fought on April 21, 1836, in present-day La Porte and Pasadena, Texas, was the final and decisive battle of the Texas Revolution. Led by General Samuel Houston, the Texan Army engage ...

, which allowed secession to take place.

Revolts erupted throughout several states after Santa Anna's rise to power. The revolution in Texas began in

Gonzales, Texas, when Santa Anna ordered troops to go there and disarm the militia. The war leaned heavily in favor of the rebels after they had won the

Battle of Gonzales, captured the fort

La Bahía, and successfully captured

San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_t ...

(commonly called Béxar at the time). The war ended in 1836 at the

Battle of San Jacinto

The Battle of San Jacinto ( es, Batalla de San Jacinto), fought on April 21, 1836, in present-day La Porte and Pasadena, Texas, was the final and decisive battle of the Texas Revolution. Led by General Samuel Houston, the Texan Army engage ...

(about 20 miles east of modern-day

Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 i ...

) where General

Sam Houston led the Texas army to victory over a portion of the Mexican Army led by Santa Anna, who was captured shortly after the battle. The conclusion of the war resulted in the creation of the

Republic of Texas, a nation that teetered between collapse and invasion from Mexico until it was annexed by the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

of America in 1845.

Mexican–American War, 1846–1848

The dominant figure of the second quarter of 19th century

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

was the dictator

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

. During this period, many of the territories in the north were lost to the United States. Santa Anna was the nation's leader during the conflict with

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, which declared itself independent in 1836, and during the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

(1846–48). One of the memorable battles of the U.S. invasion of 1847 was when a group of

young Military College cadets (now considered national

hero

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or a main fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or strength. Like other formerly gender-specific terms (like ''actor''), ''her ...

es) fought to the death against a large army of experienced soldiers in the

Battle of Chapultepec

The Battle of Chapultepec was a battle between American forces and Mexican forces holding the strategically located Chapultepec Castle just outside Mexico City, fought 13 September 1847 during the Mexican–American War. The building, sitting ...

(September 13, 1847). Ever since this war many Mexicans have resented the loss of much territory, some by means of coercion, and more territory sold cheaply by the dictator Santa Anna (allegedly) for personal profit.

After the declaration of war, U.S. forces invaded Mexican territory on several fronts. In the Pacific, the U.S. Navy sent

John D. Sloat

John Drake Sloat (July 26, 1781 – November 28, 1867) was a commodore in the United States Navy who, in 1846, claimed California for the United States.

Life

He was born at the family home of Sloat House in Sloatsburg, New York, of Dutch ancestr ...

to occupy

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

and claim it for the U.S. because of concerns that

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

might also attempt to occupy the area. He linked up with Anglo colonists in Northern California controlled by the U.S. Army. Meanwhile, U.S. army troops under

Stephen W. Kearny occupied

Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Kearny led a small force to California where, after some initial reverses, he united with naval reinforcements under

Robert F. Stockton

Robert Field Stockton (August 20, 1795 – October 7, 1866) was a United States Navy commodore, notable in the capture of California during the Mexican–American War. He was a naval innovator and an early advocate for a propeller-driven, steam-p ...

to occupy

San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United State ...

and

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

.

The main force led by Taylor continued across the Rio Grande, winning the

Battle of Monterrey

In the Battle of Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846) during the Mexican–American War, General Pedro de Ampudia and the Mexican Army of the North was defeated by the Army of Occupation, a force of United States Regulars, Volunteers an ...

in September 1846. President

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

personally marched north to fight Taylor but was defeated at the battle of

Buena Vista Buena Vista, meaning "good view" in Spanish, may refer to:

Places Canada

*Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador, with the name being originally derived from “Buena Vista”

*Buena Vista, Saskatchewan

*Buena Vista, Saskatoon, a neighborhood in ...

on February 22, 1847. Meanwhile, rather than reinforce Taylor's army for a continued advance, President Polk sent a second army under U.S. general

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

in March, which was transported to the port of

Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

by sea, to begin an invasion of the country's heartland. Scott won the

Siege of Veracruz

The Battle of Veracruz was a 20-day siege of the key Mexican beachhead seaport of Veracruz during the Mexican–American War. Lasting from March 9–29, 1847, it began with the first large-scale amphibious assault conducted by United States ...

and marched toward

Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital city, capital and primate city, largest city of Mexico, and the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North Amer ...

, winning the battles of

Cerro Gordo and

Chapultepec

Chapultepec, more commonly called the "Bosque de Chapultepec" (Chapultepec Forest) in Mexico City, is one of the largest city parks in Mexico, measuring in total just over 686 hectares (1,695 acres). Centered on a rock formation called Chapultep ...

and occupying the capital.

The

Treaty of Cahuenga

The Treaty of Cahuenga ( es, Tratado de Cahuenga), also called the Capitulation of Cahuenga (''Capitulación de Cahuenga''), was an 1847 agreement that ended the Conquest of California, resulting in a ceasefire between Californios and Americans. ...

, signed on January 13, 1847, ended the fighting in

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

. The

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the war and gave the USA undisputed control of Texas as well as California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of

Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

,

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

,

New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

, and

Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the s ...

. In return, Mexico received $18,250,000, equivalent to $ in dollars, total for the cost of the war.

Caste War of Yucatán, 1847–1901

The

Caste War

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultura ...

lasted from 1847 to 1901, and began as a war of the

Maya

Maya may refer to:

Civilizations

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Maya language, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (Ethiopia), a popul ...

against the ''Yucatecos'', a colloquial name for people of non-Maya ancestry that settled in the region. Nowadays "Yucatecos" is the demonym given to people who live in the Yucatán state.

The Maya revolt reached its peak of success in the spring of 1848 by driving the Europeans from all the

Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula (, also , ; es, Península de Yucatán ) is a large peninsula in southeastern Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north ...

, with the exception of the walled cities of

Campeche and

Mérida and a stronghold between the road from Mérida and

Sisal

Sisal (, ) (''Agave sisalana'') is a species of flowering plant native to southern Mexico, but widely cultivated and naturalized in many other countries. It yields a stiff fibre used in making rope and various other products. The term sisal may ...

.

The Yucatecan governor

Miguel Barbachano had prepared a decree for the evacuation of Mérida, but was apparently delayed in publishing it by the lack of suitable paper in the besieged capital. The decree became unnecessary when the republican troops suddenly broke the siege and took the offensive with major advances. The majority of the Maya troops, not realizing the unique strategic advantage of their situation, had left the lines to plant their crops, planning to return after planting.

Yucatán had considered itself an independent nation, but during the crisis of the revolt had offered sovereignty to any nation that would aid in defeating the Indians. The Mexican government was in a rare position of being cash rich from payment by the United States under the

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

for the territory taken in the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, and accepted Yucatán's offer. Yucatán was officially reunited with Mexico on 17 August 1848. European Yucateco forces rallied, aided by fresh guns, money, and troops from Mexico, and pushed back the Maya from more than half of the state.

In the 1850s a stalemate developed, with the Yucatecan government in control of the north-west, and the Maya in control of the south-east, with a sparsely populated jungle frontier in between.

In 1850, the Maya of the south east were inspired to continue the struggle by the apparition of the "Talking Cross". This apparition, believed to be a way in which God communicated with the Maya, dictated that the War continue. Chan Santa Cruz (Small Holy Cross) became the religious and political center of the Maya resistance and the rebellion came to be infused with religious significance.

Chan Santa Cruz

Chan Santa Cruz was the name of a shrine in Mexico of the Maya Cruzob (or Cruzoob) religious movement. It was also the name of the town that developed around it (now known as Felipe Carrillo Puerto) and, less formally, the late 19th-century indi ...

also became the name of the largest of the independent Maya states, as well as the name of the capital town. The followers of the Cross were known as "Cruzob".

The government of Yucatán first declared the war over in 1855, but hopes for peace were premature. There were regular skirmishes, and occasional deadly major assaults into each other's territory, by both sides. The

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

recognized the Chan Santa Cruz Maya as a de facto independent nation, in part because of the major trade between Chan Santa Cruz and

British Honduras

British Honduras was a British Crown colony on the east coast of Central America, south of Mexico, from 1783 to 1964, then a self-governing colony, renamed Belize in June 1973, .

Negotiations in 1883 led to a treaty signed on 11 January 1884 in

Belize City

Belize City is the largest city in Belize and was once the capital of the former British Honduras. According to the 2010 census, Belize City has a population of 57,169 people in 16,162 households. It is at the mouth of the Haulover Creek, w ...

by a Chan Santa Cruz general and the vice-Governor of Yucatán recognizing Mexican sovereignty over Chan Santa Cruz in exchange for Mexican recognition of Chan Santa Cruz leader

Crescencio Poot as "Governor" of the "State" of Chan Santa Cruz, but the following year there was a

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

in Chan Santa Cruz, and the treaty was declared cancelled.

Era of the Liberal Reform

This period was the only one in the nineteenth century with civilian control of the government, but it was not a peaceful era, with a civil war and the foreign invasion of the French and monarchy supported by Mexico's Conservatives, followed by the restoration of the Liberal Republic.

Overthrow of Santa Anna in the Revolution of Ayutla, 1855

The

Revolution of Ayutla

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

was an 1854 plan to overthrow the

Santa Anna Santa Anna may refer to:

* Santa Anna, Texas, a town in Coleman County in Central Texas, United States

* Santa Anna, Starr County, Texas

* Santa Anna Township, DeWitt County, Illinois, one of townships in DeWitt County, Illinois, United States. ...

regime by the revolutionary

Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec, he was the first indigenous pre ...

during his exile in

. The revolution sustained much support among intellectuals. This tension led to the final resignation of Santa Anna in 1855.

Juan Álvarez

Juan Nepomuceno Álvarez Hurtado de Luna, generally known as Juan Álvarez, (27 January 1790 – 21 August 1867) was a general, long-time caudillo (regional leader) in southern Mexico, and president of Mexico for two months in 1855, following ...

led a provisional government after Santa Anna's final resignation, and the Revolution of Ayutla became one of the leading factors in the

Reform War

The Reform War, or War of Reform ( es, Guerra de Reforma), also known as the Three Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Tres Años), was a civil war in Mexico lasting from January 11, 1858 to January 11, 1861, fought between liberals and conservativ ...

.

The Reform War, 1857–1860

In 1855

Ignacio Comonfort

Ignacio Gregorio Comonfort de los Ríos (; 12 March 1812 – 13 November 1863), known as Ignacio Comonfort, was a Mexican politician and soldier who was also president during one of the most eventful periods in 19th century Mexican history: La ...

, leader of the self-described Moderates, was elected president. The ''Moderados'' tried to find a middle ground between the nation's Liberals and Conservatives. During Comonfort's presidency a new Constitution was drafted. The

Constitution of 1857

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1857 ( es, Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos de 1857), often called simply the Constitution of 1857, was the liberal constitution promulgated in 1857 by Constituent Co ...

sought to establish equality before the law, so that the abolition of fueros, the special privileges of corporate groups, were abolished, including the ''fuero militar''. Such reforms were unacceptable to the leadership of the clergy and the Conservatives, Comonfort and members of his administration were

excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

and a revolt was declared. This led to the

War of Reform

The Reform War, or War of Reform ( es, Guerra de Reforma), also known as the Three Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Tres Años), was a civil war in Mexico lasting from January 11, 1858 to January 11, 1861, fought between liberals and conservativ ...

, from December 1857 to January 1861. This

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

became increasingly bloody and polarized the nation's politics. Many of the Moderados came over to the side of the Liberales, convinced that the great political power of the Church needed to be curbed. For some time the Liberals and Conservatives had their own governments, the Conservatives in Mexico City and the Liberals headquartered in

Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...