Medieval warfare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Medieval warfare is the warfare of the

Medieval warfare is the warfare of the

In Europe, breakdowns in centralized power led to the rise of several groups that turned to large-scale pillage as a source of income. Most notably the

In Europe, breakdowns in centralized power led to the rise of several groups that turned to large-scale pillage as a source of income. Most notably the

Advances in the prosecution of

Advances in the prosecution of

In the earliest Middle Ages, it was the obligation of every noble to respond to the call to battle with his equipment, archers, and infantry. This decentralized system was necessary due to the social order of the time but could lead to motley forces with variable training, equipment and abilities. The more resources the noble had access to, the better his troops would typically be.

Typically the feudal armies consisted of a core of highly skilled knights and their household troops, mercenaries hired for the time of the campaign and feudal levies fulfilling their feudal obligations, who usually were little more than rabble. They could, however, be efficient in disadvantageous terrain. Towns and cities could also field militias.

As central governments grew in power, a return to the citizen and mercenary armies of the classical period also began, as central levies of the peasantry began to be the central recruiting tool. It was estimated that the best

In the earliest Middle Ages, it was the obligation of every noble to respond to the call to battle with his equipment, archers, and infantry. This decentralized system was necessary due to the social order of the time but could lead to motley forces with variable training, equipment and abilities. The more resources the noble had access to, the better his troops would typically be.

Typically the feudal armies consisted of a core of highly skilled knights and their household troops, mercenaries hired for the time of the campaign and feudal levies fulfilling their feudal obligations, who usually were little more than rabble. They could, however, be efficient in disadvantageous terrain. Towns and cities could also field militias.

As central governments grew in power, a return to the citizen and mercenary armies of the classical period also began, as central levies of the peasantry began to be the central recruiting tool. It was estimated that the best

Weapons

Medieval weapons consisted of many different types of ranged and hand-held objects:

* Melee

**

Weapons

Medieval weapons consisted of many different types of ranged and hand-held objects:

* Melee

**

Medieval warfare largely predated the use of Train (military), supply trains, which meant that armies had to acquire food supplies from the territory they were passing through. This meant that large-scale looting by soldiers was unavoidable, and was actively encouraged in the 14th century with its emphasis on ''chevauchée'' tactics, where mounted troops would burn and pillage enemy territory in order to distract and demoralize the enemy while denying them their supplies.

Through the medieval period, soldiers were responsible for supplying themselves, either through foraging, looting, or purchases. Even so, military commanders often provided their troops with food and supplies, but this would be provided instead of the soldiers' wages, or soldiers would be expected to pay for it from their wages, either at cost or even with a profit.

In 1294, the same year John Balliol, John II de Balliol of Scotland refused to support Edward I of England's planned invasion of France, Edward I implemented a system in Wales and Scotland where sheriffs would acquire foodstuffs, horses and carts from merchants with Eminent domain, compulsory sales at prices fixed below typical market prices under the Crown's rights of purveyance, prise and purveyance. These goods would then be transported to Supply depot, Royal Magazines in southern Scotland and along the Scottish border where English Conscription, conscripts under his command could purchase them. This continued during the Wars of Scottish Independence, First War of Scottish Independence which began in 1296, though the system was unpopular and was ended with Edward I's death in 1307.

Starting under the rule of Edward II of England, Edward II in 1307 and ending under the rule of Edward III of England, Edward III in 1337, the English instead used a system where merchants would be asked to meet armies with supplies for the soldiers to purchase. This led to discontent as the merchants saw an opportunity to War profiteering, profiteer, forcing the troops to pay well above normal market prices for food.

As Edward III went to war with France in the

Medieval warfare largely predated the use of Train (military), supply trains, which meant that armies had to acquire food supplies from the territory they were passing through. This meant that large-scale looting by soldiers was unavoidable, and was actively encouraged in the 14th century with its emphasis on ''chevauchée'' tactics, where mounted troops would burn and pillage enemy territory in order to distract and demoralize the enemy while denying them their supplies.

Through the medieval period, soldiers were responsible for supplying themselves, either through foraging, looting, or purchases. Even so, military commanders often provided their troops with food and supplies, but this would be provided instead of the soldiers' wages, or soldiers would be expected to pay for it from their wages, either at cost or even with a profit.

In 1294, the same year John Balliol, John II de Balliol of Scotland refused to support Edward I of England's planned invasion of France, Edward I implemented a system in Wales and Scotland where sheriffs would acquire foodstuffs, horses and carts from merchants with Eminent domain, compulsory sales at prices fixed below typical market prices under the Crown's rights of purveyance, prise and purveyance. These goods would then be transported to Supply depot, Royal Magazines in southern Scotland and along the Scottish border where English Conscription, conscripts under his command could purchase them. This continued during the Wars of Scottish Independence, First War of Scottish Independence which began in 1296, though the system was unpopular and was ended with Edward I's death in 1307.

Starting under the rule of Edward II of England, Edward II in 1307 and ending under the rule of Edward III of England, Edward III in 1337, the English instead used a system where merchants would be asked to meet armies with supplies for the soldiers to purchase. This led to discontent as the merchants saw an opportunity to War profiteering, profiteer, forcing the troops to pay well above normal market prices for food.

As Edward III went to war with France in the

The waters surrounding Europe can be grouped into two types which affected the design of craft that traveled and therefore the warfare. The Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and Black Seas were free of large tides, generally calm, and had predictable weather. The seas around the north and west of Europe experienced stronger and less predictable weather. The weather gage, weather gauge, the advantage of having a following wind, was an important factor in naval battles, particularly to the attackers. Typically westerlies (winds blowing from west to east) dominated Europe, giving naval powers to the west an advantage. Medieval sources on the conduct of medieval naval warfare are less common than those about land-based war. Most medieval chroniclers had no experience of life on the sea and generally were not well informed. Maritime archaeology has helped provide information.

The waters surrounding Europe can be grouped into two types which affected the design of craft that traveled and therefore the warfare. The Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and Black Seas were free of large tides, generally calm, and had predictable weather. The seas around the north and west of Europe experienced stronger and less predictable weather. The weather gage, weather gauge, the advantage of having a following wind, was an important factor in naval battles, particularly to the attackers. Typically westerlies (winds blowing from west to east) dominated Europe, giving naval powers to the west an advantage. Medieval sources on the conduct of medieval naval warfare are less common than those about land-based war. Most medieval chroniclers had no experience of life on the sea and generally were not well informed. Maritime archaeology has helped provide information.

Early in the medieval period, ships in the context of warfare were used primarily for transporting troops. In the Mediterranean, naval warfare in the Middle Ages was similar to that under late Roman Empire: fleets of galleys would exchange missile fire and then try to board bow first to allow marine (military), marines to fight on deck. This mode of naval warfare remained the same into the early modern period, as, for example, at the Battle of Lepanto (1571), Battle of Lepanto. Famous admirals included Roger of Lauria, Andrea Doria and Hayreddin Barbarossa.

Galleys were not suitable for the colder and more turbulent North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, although they saw occasional use. Bulkier ships were developed which were primarily sail-driven, although the long lowboard Viking-style rowed longship saw use well into the 15th century. Their main purpose in the north remained the transportation of soldiers to fight on the decks of the opposing ship (as, for example, at the Battle of Svolder or the Battle of Sluys).

Late medieval sailing warships resembled floating fortresses, with towers in the bow (boat), bows and at the stern (respectively, the forecastle and aftcastle). The large superstructure made these warships quite unstable, but the decisive defeats that the more mobile but considerably lower boarded longships suffered at the hands of high-boarded cogs in the 15th century ended the issue of which ship type would dominate northern European warfare.

Early in the medieval period, ships in the context of warfare were used primarily for transporting troops. In the Mediterranean, naval warfare in the Middle Ages was similar to that under late Roman Empire: fleets of galleys would exchange missile fire and then try to board bow first to allow marine (military), marines to fight on deck. This mode of naval warfare remained the same into the early modern period, as, for example, at the Battle of Lepanto (1571), Battle of Lepanto. Famous admirals included Roger of Lauria, Andrea Doria and Hayreddin Barbarossa.

Galleys were not suitable for the colder and more turbulent North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, although they saw occasional use. Bulkier ships were developed which were primarily sail-driven, although the long lowboard Viking-style rowed longship saw use well into the 15th century. Their main purpose in the north remained the transportation of soldiers to fight on the decks of the opposing ship (as, for example, at the Battle of Svolder or the Battle of Sluys).

Late medieval sailing warships resembled floating fortresses, with towers in the bow (boat), bows and at the stern (respectively, the forecastle and aftcastle). The large superstructure made these warships quite unstable, but the decisive defeats that the more mobile but considerably lower boarded longships suffered at the hands of high-boarded cogs in the 15th century ended the issue of which ship type would dominate northern European warfare.

As guns were made more durable to withstand stronger gunpowder charges, they increased their potential to inflict critical damage to the vessel rather than just their crews. Since these guns were much heavier than the earlier anti-personnel weapons, they had to be placed lower in the ships, and fire from gunports, to avoid ships becoming unstable. In Northern Europe the technique of building ships with clinker (boat building), clinker planking made it difficult to cut ports in the hull; clinker-built (or clench-built) ships had much of their structural strength in the outer hull. The solution was the gradual adoption of Carvel (boat building), carvel-built ships that relied on an internal skeleton structure to bear the weight of the ship.

The first ships to actually mount heavy cannon capable of sinking ships were galleys, with large wrought-iron pieces mounted directly on the timbers in the bow. The first example is known from a woodcut of a Venetian galley from 1486. Heavy artillery on galleys was mounted in the bow which fit conveniently with the long-standing tactical tradition of attacking head-on and bow-first. The ordnance on galleys was quite heavy from its introduction in the 1480s, and capable of quickly demolishing medieval-style stone walls that still prevailed until the 16th century.Guilmartin (1974), pp. 264–66

This temporarily upended the strength of older seaside fortresses, which had to be rebuilt to cope with gunpowder weapons. The addition of guns also improved the amphibious abilities of galleys as they could assault supported with heavy firepower, and could be even more effectively defended when beached stern-first. Galleys and similar oared vessels remained uncontested as the most effective gun-armed warships in theory until the 1560s, and in practice for a few decades more, and were considered a grave risk to sailing warships.

As guns were made more durable to withstand stronger gunpowder charges, they increased their potential to inflict critical damage to the vessel rather than just their crews. Since these guns were much heavier than the earlier anti-personnel weapons, they had to be placed lower in the ships, and fire from gunports, to avoid ships becoming unstable. In Northern Europe the technique of building ships with clinker (boat building), clinker planking made it difficult to cut ports in the hull; clinker-built (or clench-built) ships had much of their structural strength in the outer hull. The solution was the gradual adoption of Carvel (boat building), carvel-built ships that relied on an internal skeleton structure to bear the weight of the ship.

The first ships to actually mount heavy cannon capable of sinking ships were galleys, with large wrought-iron pieces mounted directly on the timbers in the bow. The first example is known from a woodcut of a Venetian galley from 1486. Heavy artillery on galleys was mounted in the bow which fit conveniently with the long-standing tactical tradition of attacking head-on and bow-first. The ordnance on galleys was quite heavy from its introduction in the 1480s, and capable of quickly demolishing medieval-style stone walls that still prevailed until the 16th century.Guilmartin (1974), pp. 264–66

This temporarily upended the strength of older seaside fortresses, which had to be rebuilt to cope with gunpowder weapons. The addition of guns also improved the amphibious abilities of galleys as they could assault supported with heavy firepower, and could be even more effectively defended when beached stern-first. Galleys and similar oared vessels remained uncontested as the most effective gun-armed warships in theory until the 1560s, and in practice for a few decades more, and were considered a grave risk to sailing warships.

In the Medieval period, the mounted cavalry long held sway on the battlefield. Heavily armoured mounted knights represented a formidable foe for reluctant peasant draftees and lightly armoured freemen. To defeat mounted cavalry, infantry used swarms of missiles or a tightly packed phalanx of men, techniques honed in antiquity by the Greeks.

In the Medieval period, the mounted cavalry long held sway on the battlefield. Heavily armoured mounted knights represented a formidable foe for reluctant peasant draftees and lightly armoured freemen. To defeat mounted cavalry, infantry used swarms of missiles or a tightly packed phalanx of men, techniques honed in antiquity by the Greeks.

The Welsh & English longbowman used a single-piece longbow (but some bows later developed a composite design) to deliver arrows that could penetrate contemporary Mail (armour), mail and damage/dent plate armour. The longbow was a difficult weapon to master, requiring long years of use and constant practice. A skilled longbowman could shoot about 12 shots per minute. This rate of fire was far superior to competing weapons like the

The Welsh & English longbowman used a single-piece longbow (but some bows later developed a composite design) to deliver arrows that could penetrate contemporary Mail (armour), mail and damage/dent plate armour. The longbow was a difficult weapon to master, requiring long years of use and constant practice. A skilled longbowman could shoot about 12 shots per minute. This rate of fire was far superior to competing weapons like the

In 1326 the earliest known European picture of a gun appeared in a manuscript by Walter de Milemete. In 1350, Petrarch wrote that the presence of cannons on the battlefield was 'as common and familiar as other kinds of arms'.

Early artillery played a limited role in the

In 1326 the earliest known European picture of a gun appeared in a manuscript by Walter de Milemete. In 1350, Petrarch wrote that the presence of cannons on the battlefield was 'as common and familiar as other kinds of arms'.

Early artillery played a limited role in the

The Vikings were a feared force in Europe because of their savagery and speed of their attacks. Whilst seaborne raids were nothing new at the time, the Vikings refined the practice to a science through their shipbuilding, tactics and training. Unlike other raiders, the Vikings made a lasting impact on the face of Europe. During the Viking age, their expeditions, frequently combining raiding and trading, penetrated most of the old Frankish Empire, the British Isles, the Baltic region, Russia, and both Muslim and Christian Iberia. Many served as mercenaries, and the famed Varangian Guard, serving the Emperor of Constantinople, was drawn principally of Scandinavian warriors.

Viking longships were swift and easily manoeuvered; they could navigate deep seas or shallow rivers, and could carry warriors that could be rapidly deployed directly onto land due to the longships being able to land directly. The longship was the enabler of the Viking style of warfare that was fast and mobile, relying heavily on the element of surprise, and they tended to capture horses for mobility rather than carry them on their ships. The usual method was to approach a target stealthily, strike with surprise and then retire swiftly. The tactics used were difficult to stop, for the Vikings, like guerrilla-style raiders elsewhere, deployed at a time and place of their choosing. The fully armoured Viking raider would wear an iron helmet and a mail hauberk, and fight with a combination of axe, sword, shield, spear or great "Danish" two-handed axe, although the typical raider would be unarmoured, carrying only a bow and arrows, a knife "seax", a shield and spear; the swords and the axes were much less common. Almost by definition, opponents of the Vikings were ill-prepared to fight a force that struck at will, with no warning. European countries with a weak system of government would be unable to organize a suitable response and would naturally suffer the most to Viking raiders. Viking raiders always had the option to fall back in the face of a superior force or stubborn defence and then reappear to attack other locations or retreat to their bases in what is now Sweden, Denmark, Norway and their Atlantic colonies. As time went on, Viking raids became more sophisticated, with coordinated strikes involving multiple forces and large armies, as the "Great Heathen Army" that ravaged Anglo-Saxon England in the 9th century. In time, the Vikings began to hold on to the areas they raided, first wintering and then consolidating footholds for further expansion later.

With the growth of centralized authority in the Scandinavian region, Viking raids, always an expression of "private enterprise", ceased and the raids became pure voyages of conquest. In 1066, King Harald Hardråde of Norway invaded England, only to be defeated by Harold Godwinson. The two rulers had their claims to the English crown (Harald probably primarily on the overlord-ship of Northumbria) and it was this that motivated the battles rather than the lure of plunder.

The Vikings were a feared force in Europe because of their savagery and speed of their attacks. Whilst seaborne raids were nothing new at the time, the Vikings refined the practice to a science through their shipbuilding, tactics and training. Unlike other raiders, the Vikings made a lasting impact on the face of Europe. During the Viking age, their expeditions, frequently combining raiding and trading, penetrated most of the old Frankish Empire, the British Isles, the Baltic region, Russia, and both Muslim and Christian Iberia. Many served as mercenaries, and the famed Varangian Guard, serving the Emperor of Constantinople, was drawn principally of Scandinavian warriors.

Viking longships were swift and easily manoeuvered; they could navigate deep seas or shallow rivers, and could carry warriors that could be rapidly deployed directly onto land due to the longships being able to land directly. The longship was the enabler of the Viking style of warfare that was fast and mobile, relying heavily on the element of surprise, and they tended to capture horses for mobility rather than carry them on their ships. The usual method was to approach a target stealthily, strike with surprise and then retire swiftly. The tactics used were difficult to stop, for the Vikings, like guerrilla-style raiders elsewhere, deployed at a time and place of their choosing. The fully armoured Viking raider would wear an iron helmet and a mail hauberk, and fight with a combination of axe, sword, shield, spear or great "Danish" two-handed axe, although the typical raider would be unarmoured, carrying only a bow and arrows, a knife "seax", a shield and spear; the swords and the axes were much less common. Almost by definition, opponents of the Vikings were ill-prepared to fight a force that struck at will, with no warning. European countries with a weak system of government would be unable to organize a suitable response and would naturally suffer the most to Viking raiders. Viking raiders always had the option to fall back in the face of a superior force or stubborn defence and then reappear to attack other locations or retreat to their bases in what is now Sweden, Denmark, Norway and their Atlantic colonies. As time went on, Viking raids became more sophisticated, with coordinated strikes involving multiple forces and large armies, as the "Great Heathen Army" that ravaged Anglo-Saxon England in the 9th century. In time, the Vikings began to hold on to the areas they raided, first wintering and then consolidating footholds for further expansion later.

With the growth of centralized authority in the Scandinavian region, Viking raids, always an expression of "private enterprise", ceased and the raids became pure voyages of conquest. In 1066, King Harald Hardråde of Norway invaded England, only to be defeated by Harold Godwinson. The two rulers had their claims to the English crown (Harald probably primarily on the overlord-ship of Northumbria) and it was this that motivated the battles rather than the lure of plunder. At that point, the Scandinavians had entered their medieval period and consolidated their kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. This period marks the end of significant raider activity both for plunder or conquest. The resurgence of centralized authority throughout Europe limited opportunities for traditional raiding expeditions in the West, whilst the Christianisation of the Scandinavian kingdoms themselves encouraged them to direct their attacks against the still predominantly pagan regions of the eastern Baltic. The Scandinavians started adapting more continental European ways, whilst retaining an emphasis on naval power – the "Viking" clinker-built warship was used in the war until the 14th century at least. However, developments in shipbuilding elsewhere removed the advantage the Scandinavian countries had previously enjoyed at sea, whilst castle building throughout frustrated and eventually ended Viking raids. Natural trading and diplomatic links between Scandinavia and Continental Europe ensured that the Scandinavians kept up to date with continental developments in warfare.

The Scandinavian armies of the High Middle Ages followed the usual pattern of the Northern European armies, but with a stronger emphasis on infantry. The terrain of Scandinavia favoured heavy infantry, and whilst the nobles fought mounted in the continental fashion, the Scandinavian peasants formed a well-armed and well-armoured infantry, of which approximately 30% to 50% would be archers or crossbowmen. The

At that point, the Scandinavians had entered their medieval period and consolidated their kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. This period marks the end of significant raider activity both for plunder or conquest. The resurgence of centralized authority throughout Europe limited opportunities for traditional raiding expeditions in the West, whilst the Christianisation of the Scandinavian kingdoms themselves encouraged them to direct their attacks against the still predominantly pagan regions of the eastern Baltic. The Scandinavians started adapting more continental European ways, whilst retaining an emphasis on naval power – the "Viking" clinker-built warship was used in the war until the 14th century at least. However, developments in shipbuilding elsewhere removed the advantage the Scandinavian countries had previously enjoyed at sea, whilst castle building throughout frustrated and eventually ended Viking raids. Natural trading and diplomatic links between Scandinavia and Continental Europe ensured that the Scandinavians kept up to date with continental developments in warfare.

The Scandinavian armies of the High Middle Ages followed the usual pattern of the Northern European armies, but with a stronger emphasis on infantry. The terrain of Scandinavia favoured heavy infantry, and whilst the nobles fought mounted in the continental fashion, the Scandinavian peasants formed a well-armed and well-armoured infantry, of which approximately 30% to 50% would be archers or crossbowmen. The

By 1241, having conquered large parts of Russia, the Mongols continued the invasion of Europe with a massive three-pronged advance, following the fleeing

By 1241, having conquered large parts of Russia, the Mongols continued the invasion of Europe with a massive three-pronged advance, following the fleeing

* * Lehmann, L. Th., ''Galleys in the Netherlands.'' Meulenhoff, Amsterdam. 1984. * Marsden, Peter, ''Sealed by Time: The Loss and Recovery of the Mary Rose.'' The Archaeology of the ''Mary Rose'', Volume 1. The Mary Rose Trust, Portsmouth. 2003. * * * Rodger, Nicholas A. M., "The Development of Broadside Gunnery, 1450–1650." ''Mariner's Mirror'' 82 (1996), pp. 301–24. * Rodger, Nicholas A. M., ''The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain 660–1649.'' W.W. Norton & Company, New York. 1997. * Laury Sarti, "Perceiving War and the Military in Early Christian Gaul (ca. 400–700 A.D.)" (= Brill's Series on the Early Middle Ages, 22), Leiden/Boston 2013, .

Parts of which are available online

* McNeill, William Hardy. ''The pursuit of power: technology, armed force, and society since A.D. 1000''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982. * Oman, Charles William Chadwick. ''A history of the art of war in the Middle Ages''. London: Greenhill Books; Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1998.

De Re Militari: The Society for Medieval Military History

* Parker, Geoffrey. ''The Military Revolution: Military innovation and the Rise of The West'', 1988. * Titterton, James, ''Deception in Medieval Warfare''. Boydell & Brewer, 2022,

Medieval Warfare

Siege warfare, open battles, weapons, armour and fighting techniques.

Database of thousands of English soldiers during the later medieval periodMedieval History Database (MHDB), which includes medieval military recordsGuide to researching records of medieval soldiers, from the British National Archives site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Medieval Warfare Warfare of the Middle Ages, Military history of Europe

Medieval warfare is the warfare of the

Medieval warfare is the warfare of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. Technological, cultural, and social advancements had forced a severe transformation in the character of warfare from antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

, changing military tactics

Military tactics encompasses the art of organizing and employing fighting forces on or near the battlefield. They involve the application of four battlefield functions which are closely related – kinetic or firepower, Mobility (military), mobil ...

and the role of cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

(see military history

Military history is the study of War, armed conflict in the Human history, history of humanity, and its impact on the societies, cultures and economies thereof, as well as the resulting changes to Politics, local and international relationships.

...

). In terms of fortification, the Middle Ages saw the emergence of the castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

in Europe, which then spread to the Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

(modern day Israel and Palestine).

Strategy and tactics

''De re militari''

Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus

Publius (or Flavius) Vegetius Renatus, known as Vegetius (), was a writer of the Later Roman Empire (late 4th century). Nothing is known of his life or station beyond what is contained in his two surviving works: ''Epitoma rei militaris'' (also r ...

wrote ''De re militari

''De re militari'' (Latin "Concerning Military Matters"), also ''Epitoma rei militaris'', is a treatise by the Late Latin writer Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus about Roman warfare and military principles as a presentation of the methods and ...

(Concerning Military Matters)'' possibly in the late 4th century. Described by historian Walter Goffart as "the bible of warfare throughout the Middle Ages", ''De re militari'' was widely distributed through the Latin West. While Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

relied on a single text for the basis of its military knowledge, the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

in Southeastern Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (a ...

had a succession of military writers. Though Vegetius had no military experience and ''De re militari'' was derived from the works of Cato and Frontinus, his books were the standard for military discourse in Western Europe from their production until the 16th century.

''De re militari'' was divided into five books: who should be a soldier and the skills they needed to learn, the composition and structure of an army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, field tactics, how to conduct and withstand siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

s, and the role of the navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

. According to Vegetius, infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

was the most important element of an army because it was cheap compared to cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

and could be deployed on any terrain.Nicholson (2004), p. 14 One of the tenets he put forward was that a general should only engage in battle when he was sure of victory or had no other choice. As archaeologist Robert Liddiard explains, "Pitched battle

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A ...

s, particularly in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, were rare."

Although his work was widely reproduced, and over 200 copies, translations, and extracts survive today, the extent to which Vegetius affected the actual practice of warfare as opposed to its concept is unclear because of his habit of stating the obvious. Historian Michael Clanchy

Michael Thomas Clanchy (28 November 1936 – 29 January 2021) was Professor Emeritus of Medieval History at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London and Fellow of the British Academy.

Early life and education

Clanchy was bo ...

noted "the medieval axiom that laymen are illiterate and its converse that clergy are literate", so it may be the case that few soldiers read Vegetius' work. While their Roman predecessors were well-educated and had been experienced in warfare, the European nobility of the early Medieval period were not renowned for their education, but from the 12th century, it became more common for them to read.Nicholson (2004), p. 16

Some soldiers regarded the experience of warfare as more valuable than reading about it; for example, Geoffroi de Charny

Geoffroi de Charny ({{circa, 1306 – 19 September 1356) was the third son of Jean de Charny, the lord of Charny (then a major Burgundian fortress), and Marguerite de Joinville, daughter of Jean de Joinville, the biographer and close friend of Fra ...

, a 14th century knight who wrote about warfare, recommended that his audience should learn by observing and asking advice from their superiors. Vegetius remained prominent in medieval literature on warfare, although it is uncertain to what extent his work was read by the warrior class as opposed to the clergy. In 1489, King Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry's mother, Margaret Beauf ...

commissioned the translation of ''De re militari'' into English, "so every gentleman born to arms and all manner of men of war, captains, soldiers, victuallers and all others would know how they ought to behave in the feats of wars and battles".

Fortifications

In Europe, breakdowns in centralized power led to the rise of several groups that turned to large-scale pillage as a source of income. Most notably the

In Europe, breakdowns in centralized power led to the rise of several groups that turned to large-scale pillage as a source of income. Most notably the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

, Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

, Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

, Cumans

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many so ...

, Tartars, and Magyars

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Uralic ...

raided significantly. As these groups were generally small and needed to move quickly, building fortifications

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''face ...

was a good way to provide refuge and protection for the people and the wealth in the region.

These fortifications evolved throughout the Middle Ages, the most important form being the castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

, a structure which has become almost synonymous with the Medieval era in the popular eye. The castle served as a protected place for the local elites. Inside a castle they were protected from bands of raiders and could send mounted warriors to drive the enemy from the area, or to disrupt the efforts of larger armies to supply themselves in the region by gaining local superiority over foraging parties that would be impossible against the whole enemy host.

Fortifications were a very important part of warfare because they provided safety to the lord, his family, and his servants. They provided refuge from armies too large to face in open battle. The ability of the heavy cavalry to dominate a battle on an open field was useless against fortifications. Building siege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while oth ...

s was a time-consuming process, and could seldom be effectively done without preparations before the campaign. Many sieges could take months, if not years, to weaken or demoralize the defenders sufficiently. Fortifications were an excellent means of ensuring that the elite could not be easily dislodged from their lands – as Count Baldwin of Hainaut commented in 1184 on seeing enemy troops ravage his lands from the safety of his castle, "they can't take the land with them".

Siege warfare

In the Medieval period besieging armies used a wide variety ofsiege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while oth ...

s including: scaling ladders; battering ram

A battering ram is a siege engine that originated in ancient times and was designed to break open the masonry walls of fortifications or splinter their wooden gates. In its simplest form, a battering ram is just a large, heavy log carried b ...

s; siege tower

A Roman siege tower or breaching tower (or in the Middle Ages, a belfry''Castle: Stephen Biesty's Cross-Sections''. Dorling Kindersley Pub (T); 1st American edition (September 1994). Siege towers were invented in 300 BC. ) is a specialized siege ...

s and various types of catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stor ...

s such as the mangonel

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel o ...

, onager

The onager (; ''Equus hemionus'' ), A new species called the kiang (''E. kiang''), a Tibetan relative, was previously considered to be a subspecies of the onager as ''E. hemionus kiang'', but recent molecular studies indicate it to be a distinct ...

, ballista

The ballista (Latin, from Greek βαλλίστρα ''ballistra'' and that from βάλλω ''ballō'', "throw"), plural ballistae, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an ancient missile weapon that launched either bolts or stones at a distant ...

, and trebuchet

A trebuchet (french: trébuchet) is a type of catapult that uses a long arm to throw a projectile. It was a common powerful siege engine until the advent of gunpowder. The design of a trebuchet allows it to launch projectiles of greater weight ...

. Siege techniques also included mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the econom ...

in which tunnels were dug under a section of the wall and then rapidly collapsed to destabilize the wall's foundation. Another technique was to bore into the enemy walls, however, this was not nearly as effective as other methods due to the thickness of castle walls.

Advances in the prosecution of

Advances in the prosecution of siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

s encouraged the development of a variety of defensive counter-measures. In particular, Medieval fortifications became progressively stronger – for example, the advent of the concentric castle

A concentric castle is a castle with two or more concentric curtain walls, such that the outer wall is lower than the inner and can be defended from it. The layout was square (at Belvoir and Beaumaris) where the terrain permitted, or an irreg ...

from the period of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

– and more dangerous to attackers – witness the increasing use of machicolations, as well the preparation of hot or incendiary substances. Arrow slit

An arrowslit (often also referred to as an arrow loop, loophole or loop hole, and sometimes a balistraria) is a narrow vertical aperture in a fortification through which an archer can launch arrows or a crossbowman can launch bolts.

The interio ...

s, concealed doors for sallies, and deep water wells were also integral to resisting siege at this time. Designers of castles paid particular attention to defending entrances, protecting gates with drawbridges, portcullises and barbicans. Wet animal skins were often draped over gates to repel fire. Moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch, either dry or filled with water, that is dug and surrounds a castle, fortification, building or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. In some places moats evolved into more extensive ...

s and other water defences, whether natural or augmented, were also vital to defenders.

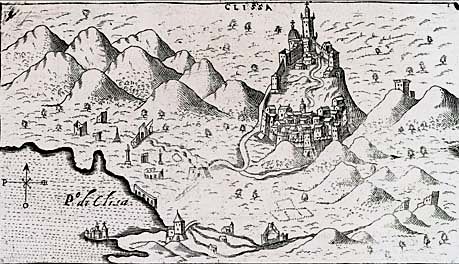

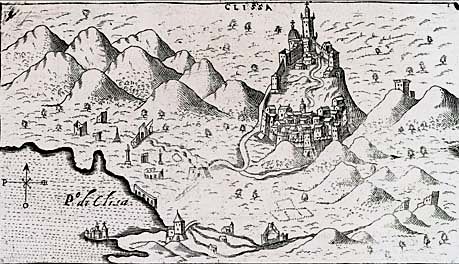

In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, virtually all large cities had city wall

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications with towers, bastions and gates ...

s – Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik (), historically known as Ragusa (; see notes on naming), is a city on the Adriatic Sea in the region of Dalmatia, in the southeastern semi-exclave of Croatia. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterran ...

in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

is an impressive and well-preserved example – and more important cities had citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

I ...

s, fort

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

s or castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

s. Great effort was expended to ensure a good water supply inside the city in case of siege. In some cases, long tunnels were constructed to carry water into the city. In other cases, such as the Ottoman siege of Shkodra

The fourth siege of Shkodra of 1478–79 was a confrontation between the Ottoman Empire and the Venetians together with the League of Lezhe and other Albanians at Shkodra (Scutari in Italian) and its Rozafa Castle during the First Ottoman-V ...

, Venetian engineers had designed and installed cisterns that were fed by rain water channeled by a system of conduits in the walls and buildings. Complex systems of tunnels were used for storage and communications in medieval cities like Tábor

Tábor (; german: Tabor) is a town in the South Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 33,000 inhabitants. The town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument reservation.

Administrative parts

The followi ...

in Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

. Against these would be matched the mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic via ...

skills of teams of trained sapper

A sapper, also called a pioneer or combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefields, preparing ...

s, who were sometimes employed by besieging armies.

Until the invention of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

-based weapons (and the resulting higher-velocity projectiles), the balance of power and logistics favoured the defender. With the invention of gunpowder, the traditional methods of defence became less and less effective against a determined siege.

Organization

The medieval knight was usually a mounted and armouredsoldier

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, or an officer.

Etymology

The word ''soldier'' derives from the Middle English word , from Old French ...

, often connected with nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

or royalty

Royalty may refer to:

* Any individual monarch, such as a king, queen, emperor, empress, etc.

* Royal family, the immediate family of a king or queen regnant, and sometimes his or her extended family

* Royalty payment for use of such things as int ...

, although (especially in north-eastern Europe) knights could also come from the lower classes, and could even be enslaved persons. The cost of their armour, horses, and weapons

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

was great; this, among other things, helped gradually transform the knight, at least in western Europe, into a distinct social class separate from other warriors. During the crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

, holy orders of Knights fought in the Holy Land (see Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

, the Hospitallers

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

, etc.).

The light cavalry consisted usually of lighter armed and armoured men, who could have lances, javelins or missile weapons, such as bows or crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an elastic launching device consisting of a bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar fashion to the stock of a long fi ...

s. In much of the Middle Ages, light cavalry usually consisted of wealthy commoners. Later in the Middle Ages, light cavalry would also include sergeants who were men who had trained as knights but could not afford the costs associated with the title. Light cavalry was used as scouts, skirmishers or outflankers. Many countries developed their styles of light cavalries, such as Hungarian mounted archers, Spanish jinete

''Jinete'' () is Spanish for " horseman", especially in the context of light cavalry.

Etymology

The word Jinete (of Berber ''zenata'') designates, in Castilian and the Provençal dialect of Occitan language, those who show great skill and riding ...

s, Italian and German mounted crossbowmen and English currours.

The infantry was recruited and trained in a wide variety of manners in different regions of Europe all through the Middle Ages, and probably always formed the most numerous part of a medieval field army. Many infantrymen in prolonged wars would be mercenaries. Most armies contained significant numbers of spearmen, archers and other unmounted soldiers.

Recruiting

In the earliest Middle Ages, it was the obligation of every noble to respond to the call to battle with his equipment, archers, and infantry. This decentralized system was necessary due to the social order of the time but could lead to motley forces with variable training, equipment and abilities. The more resources the noble had access to, the better his troops would typically be.

Typically the feudal armies consisted of a core of highly skilled knights and their household troops, mercenaries hired for the time of the campaign and feudal levies fulfilling their feudal obligations, who usually were little more than rabble. They could, however, be efficient in disadvantageous terrain. Towns and cities could also field militias.

As central governments grew in power, a return to the citizen and mercenary armies of the classical period also began, as central levies of the peasantry began to be the central recruiting tool. It was estimated that the best

In the earliest Middle Ages, it was the obligation of every noble to respond to the call to battle with his equipment, archers, and infantry. This decentralized system was necessary due to the social order of the time but could lead to motley forces with variable training, equipment and abilities. The more resources the noble had access to, the better his troops would typically be.

Typically the feudal armies consisted of a core of highly skilled knights and their household troops, mercenaries hired for the time of the campaign and feudal levies fulfilling their feudal obligations, who usually were little more than rabble. They could, however, be efficient in disadvantageous terrain. Towns and cities could also field militias.

As central governments grew in power, a return to the citizen and mercenary armies of the classical period also began, as central levies of the peasantry began to be the central recruiting tool. It was estimated that the best infantrymen

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marin ...

came from the younger sons of free land-owning yeomen

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

, such as the English archers and Swiss pikemen. England was one of the most centralized states in the Late Middle Ages, and the armies that fought the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

were mostly paid professionals.

In theory, every Englishman had an obligation to serve for forty days. Forty days was not long enough for a campaign, especially one on the continent. Thus the scutage

Scutage is a medieval English tax levied on holders of a knight's fee under the feudal land tenure of knight-service. Under feudalism the king, through his vassals, provided land to knights for their support. The knights owed the king military s ...

was introduced, whereby most Englishmen paid to escape their service and this money was used to create a permanent army. However, almost all high medieval armies in Europe were composed of a great deal of paid core troops, and there was a large mercenary market in Europe from at least the early 12th century.

As the Middle Ages progressed in Italy, Italian cities began to rely mostly on mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

to do their fighting rather than the militias that had dominated the early and high medieval period in this region. These would be groups of career soldiers who would be paid a set rate. Mercenaries tended to be effective soldiers, especially in combination with standing forces, but in Italy, they came to dominate the armies of the city-states. This made them problematic; while at war they were considerably more reliable than a standing army, at peacetime they proved a risk to the state itself like the Praetorian Guard

The Praetorian Guard (Latin: ''cohortēs praetōriae'') was a unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors. During the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard were an escort fo ...

had once been.

Mercenary-on-mercenary warfare in Italy led to relatively bloodless campaigns which relied as much on manoeuvre as on battles, since the condottieri

''Condottieri'' (; singular ''condottiero'' or ''condottiere'') were Italian captains in command of mercenary companies during the Middle Ages and of multinational armies during the early modern period. They notably served popes and other Europ ...

recognized it was more efficient to attack the enemy's ability to wage war rather than his battle forces, discovering the concept of indirect warfare 500 years before Sir Basil Liddell Hart

Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart (31 October 1895 – 29 January 1970), commonly known throughout most of his career as Captain B. H. Liddell Hart, was a British soldier, military historian and military theorist. He wrote a series of military histo ...

, and attempting to attack the enemy supply lines, his economy and his ability to wage war rather than risking an open battle, and manoeuvre him into a position where risking a battle would have been suicidal. Machiavelli understood this indirect approach

The Indirect approach is a military strategy described and chronicled by B. H. Liddell Hart after World War I. It was an attempt to find a solution to the problem of high casualty rates in conflict zones with high force to space ratios, such as the ...

as cowardice.Equipment

Weapons

Medieval weapons consisted of many different types of ranged and hand-held objects:

* Melee

**

Weapons

Medieval weapons consisted of many different types of ranged and hand-held objects:

* Melee

** Battleaxe

A battle axe (also battle-axe, battle ax, or battle-ax) is an axe specifically designed for combat. Battle axes were specialized versions of utility axes. Many were suitable for use in one hand, while others were larger and were deployed two-ha ...

*** Horseman's pick

The horseman's pick was a weapon of Middle Eastern origin used by cavalry during the Middle Ages in Europe and the Middle East. This was a type of war hammer that had a very long spike on the reverse of the hammer head. Usually, this spike was sl ...

** Blades

*** Arming Sword

In the European High Middle Ages, the typical sword (sometimes academically categorized as the knightly sword, arming sword, or in full, knightly arming sword) was a straight, double-edged weapon with a single-handed, cruciform (i.e., cross-shape ...

*** Dagger

A dagger is a fighting knife with a very sharp point and usually two sharp edges, typically designed or capable of being used as a thrusting or stabbing weapon.State v. Martin, 633 S.W.2d 80 (Mo. 1982): This is the dictionary or popular-use de ...

*** Knife

A knife ( : knives; from Old Norse 'knife, dirk') is a tool or weapon with a cutting edge or blade, usually attached to a handle or hilt. One of the earliest tools used by humanity, knives appeared at least 2.5 million years ago, as evidenced ...

*** Longsword

A longsword (also spelled as long sword or long-sword) is a type of European sword characterized as having a cruciform hilt with a grip for primarily two-handed use (around ), a straight double-edged blade of around , and weighing approximate ...

*** Messer

** Blunt weapons

*** Club

Club may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Club'' (magazine)

* Club, a '' Yie Ar Kung-Fu'' character

* Clubs (suit), a suit of playing cards

* Club music

* "Club", by Kelsea Ballerini from the album ''kelsea''

Brands and enterprises ...

*** Mace

*** War Hammer

A war hammer (French: ''martel-de-fer'', "iron hammer") is a weapon that was used by both foot soldiers and cavalry. It is a very old weapon and gave its name, owing to its constant use, to Judah Maccabee, a 2nd-century BC Jewish rebel, and to Ch ...

** Polearm

A polearm or pole weapon is a close combat weapon in which the main fighting part of the weapon is fitted to the end of a long shaft, typically of wood, thereby extending the user's effective range and striking power. Polearms are predominantl ...

*** Halberd

A halberd (also called halbard, halbert or Swiss voulge) is a two-handed pole weapon that came to prominent use during the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. The word ''halberd'' is cognate with the German word ''Hellebarde'', deriving from ...

*** Lance

A lance is a spear designed to be used by a mounted warrior or cavalry soldier (lancer). In ancient and medieval warfare, it evolved into the leading weapon in cavalry charges, and was unsuited for throwing or for repeated thrusting, unlike s ...

*** Military fork

A military fork is a pole weapon which was used in Europe between the 15th and 19th centuries. Like many polearms, the military fork traces its lineage to an agricultural tool, in this case the pitchfork.

Unlike a trident used for fishing, the ...

, the weaponized Pitchfork

A pitchfork (also a hay fork) is an agricultural tool with a long handle and two to five tines used to lift and pitch or throw loose material, such as hay, straw, manure, or leaves.

The term is also applied colloquially, but inaccurately, to ...

*** Pollaxe

The poleaxe (also pollaxe, pole-axe, pole axe, poleax, polax) is a European polearm that was widely used by medieval infantry.

Etymology

Most etymological authorities consider the ''poll''- prefix historically unrelated to "pole", instead mea ...

*** Spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...

* Ranged

** Bow

** Longbow

A longbow (known as warbow in its time, in contrast to a hunting bow) is a type of tall bow that makes a fairly long draw possible. A longbow is not significantly recurved. Its limbs are relatively narrow and are circular or D-shaped in cross ...

** Crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an elastic launching device consisting of a bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar fashion to the stock of a long fi ...

** Throwing axe

A throwing axe is a weapon used from Ancient history, Antiquity to the Middle Ages by foot soldiers and occasionally by mounted soldiers. Usually, they are thrown in an overhand motion in a manner that causes the axe to rotate as it travels thro ...

** Throwing spear and Javelin

** Sling

Armour

* Body armour

Body armor, also known as body armour, personal armor or armour, or a suit or coat of armor, is protective clothing designed to absorb or deflect physical attacks. Historically used to protect military personnel, today it is also used by variou ...

** Leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffalo, pigs and hogs, ...

** Fabric

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not th ...

** Chainmail

Chain mail (properly called mail or maille but usually called chain mail or chainmail) is a type of armour consisting of small metal rings linked together in a pattern to form a mesh. It was in common military use between the 3rd century BC and ...

** Brigandine

** Plate armour, Plate

* Shield

* Combat helmet, Helmet

Artillery and Siege engine

* Battering rams

* Catapult

* Trebuchet

* Ballista

* Siege tower

Animals

* Camel cavalry, Camels in warfare

* Dogs in warfare#History, Dogs in warfare

* Horses in warfare and Horses in the Middle Ages

* War elephant

* War pigs

Relics

The practice of carrying relics into battle is a feature that distinguishes medieval warfare from its predecessors or early modern warfare and possibly inspired by biblical references. The presence of relics was believed to be an important source of supernatural power that served both as a spiritual weapon and a form of defence; the relics of martyrs were considered by Saint John Chrysostom much more powerful than "walls, trenches, weapons and hosts of soldiers" In Italy, the ''carroccio'' or ''carro della guerra'', the "war wagon", was an elaboration of this practice that developed during the 13th century. The ''carro della guerra'' of Milan was described in detail in 1288 by Bonvesin de la Riva in his book on the "Marvels of Milan". Wrapped in scarlet cloth and drawn by three yoke of oxen that were caparisoned in white with the red cross of Saint Ambrose, the city's patron, it carried a crucifix so massive it took four men to step it in place, like a ship's mast.Supplies and logistics

Medieval warfare largely predated the use of Train (military), supply trains, which meant that armies had to acquire food supplies from the territory they were passing through. This meant that large-scale looting by soldiers was unavoidable, and was actively encouraged in the 14th century with its emphasis on ''chevauchée'' tactics, where mounted troops would burn and pillage enemy territory in order to distract and demoralize the enemy while denying them their supplies.

Through the medieval period, soldiers were responsible for supplying themselves, either through foraging, looting, or purchases. Even so, military commanders often provided their troops with food and supplies, but this would be provided instead of the soldiers' wages, or soldiers would be expected to pay for it from their wages, either at cost or even with a profit.

In 1294, the same year John Balliol, John II de Balliol of Scotland refused to support Edward I of England's planned invasion of France, Edward I implemented a system in Wales and Scotland where sheriffs would acquire foodstuffs, horses and carts from merchants with Eminent domain, compulsory sales at prices fixed below typical market prices under the Crown's rights of purveyance, prise and purveyance. These goods would then be transported to Supply depot, Royal Magazines in southern Scotland and along the Scottish border where English Conscription, conscripts under his command could purchase them. This continued during the Wars of Scottish Independence, First War of Scottish Independence which began in 1296, though the system was unpopular and was ended with Edward I's death in 1307.

Starting under the rule of Edward II of England, Edward II in 1307 and ending under the rule of Edward III of England, Edward III in 1337, the English instead used a system where merchants would be asked to meet armies with supplies for the soldiers to purchase. This led to discontent as the merchants saw an opportunity to War profiteering, profiteer, forcing the troops to pay well above normal market prices for food.

As Edward III went to war with France in the

Medieval warfare largely predated the use of Train (military), supply trains, which meant that armies had to acquire food supplies from the territory they were passing through. This meant that large-scale looting by soldiers was unavoidable, and was actively encouraged in the 14th century with its emphasis on ''chevauchée'' tactics, where mounted troops would burn and pillage enemy territory in order to distract and demoralize the enemy while denying them their supplies.

Through the medieval period, soldiers were responsible for supplying themselves, either through foraging, looting, or purchases. Even so, military commanders often provided their troops with food and supplies, but this would be provided instead of the soldiers' wages, or soldiers would be expected to pay for it from their wages, either at cost or even with a profit.

In 1294, the same year John Balliol, John II de Balliol of Scotland refused to support Edward I of England's planned invasion of France, Edward I implemented a system in Wales and Scotland where sheriffs would acquire foodstuffs, horses and carts from merchants with Eminent domain, compulsory sales at prices fixed below typical market prices under the Crown's rights of purveyance, prise and purveyance. These goods would then be transported to Supply depot, Royal Magazines in southern Scotland and along the Scottish border where English Conscription, conscripts under his command could purchase them. This continued during the Wars of Scottish Independence, First War of Scottish Independence which began in 1296, though the system was unpopular and was ended with Edward I's death in 1307.

Starting under the rule of Edward II of England, Edward II in 1307 and ending under the rule of Edward III of England, Edward III in 1337, the English instead used a system where merchants would be asked to meet armies with supplies for the soldiers to purchase. This led to discontent as the merchants saw an opportunity to War profiteering, profiteer, forcing the troops to pay well above normal market prices for food.

As Edward III went to war with France in the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

(starting in 1337), the English returned to a practice of foraging and raiding to meet their logistical needs. This practice lasted throughout the war, extending through the remainder of Edward III's reign into the reign of Henry VI of England, Henry VI.

Naval warfare

The waters surrounding Europe can be grouped into two types which affected the design of craft that traveled and therefore the warfare. The Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and Black Seas were free of large tides, generally calm, and had predictable weather. The seas around the north and west of Europe experienced stronger and less predictable weather. The weather gage, weather gauge, the advantage of having a following wind, was an important factor in naval battles, particularly to the attackers. Typically westerlies (winds blowing from west to east) dominated Europe, giving naval powers to the west an advantage. Medieval sources on the conduct of medieval naval warfare are less common than those about land-based war. Most medieval chroniclers had no experience of life on the sea and generally were not well informed. Maritime archaeology has helped provide information.

The waters surrounding Europe can be grouped into two types which affected the design of craft that traveled and therefore the warfare. The Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and Black Seas were free of large tides, generally calm, and had predictable weather. The seas around the north and west of Europe experienced stronger and less predictable weather. The weather gage, weather gauge, the advantage of having a following wind, was an important factor in naval battles, particularly to the attackers. Typically westerlies (winds blowing from west to east) dominated Europe, giving naval powers to the west an advantage. Medieval sources on the conduct of medieval naval warfare are less common than those about land-based war. Most medieval chroniclers had no experience of life on the sea and generally were not well informed. Maritime archaeology has helped provide information.

Early in the medieval period, ships in the context of warfare were used primarily for transporting troops. In the Mediterranean, naval warfare in the Middle Ages was similar to that under late Roman Empire: fleets of galleys would exchange missile fire and then try to board bow first to allow marine (military), marines to fight on deck. This mode of naval warfare remained the same into the early modern period, as, for example, at the Battle of Lepanto (1571), Battle of Lepanto. Famous admirals included Roger of Lauria, Andrea Doria and Hayreddin Barbarossa.

Galleys were not suitable for the colder and more turbulent North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, although they saw occasional use. Bulkier ships were developed which were primarily sail-driven, although the long lowboard Viking-style rowed longship saw use well into the 15th century. Their main purpose in the north remained the transportation of soldiers to fight on the decks of the opposing ship (as, for example, at the Battle of Svolder or the Battle of Sluys).

Late medieval sailing warships resembled floating fortresses, with towers in the bow (boat), bows and at the stern (respectively, the forecastle and aftcastle). The large superstructure made these warships quite unstable, but the decisive defeats that the more mobile but considerably lower boarded longships suffered at the hands of high-boarded cogs in the 15th century ended the issue of which ship type would dominate northern European warfare.

Early in the medieval period, ships in the context of warfare were used primarily for transporting troops. In the Mediterranean, naval warfare in the Middle Ages was similar to that under late Roman Empire: fleets of galleys would exchange missile fire and then try to board bow first to allow marine (military), marines to fight on deck. This mode of naval warfare remained the same into the early modern period, as, for example, at the Battle of Lepanto (1571), Battle of Lepanto. Famous admirals included Roger of Lauria, Andrea Doria and Hayreddin Barbarossa.

Galleys were not suitable for the colder and more turbulent North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, although they saw occasional use. Bulkier ships were developed which were primarily sail-driven, although the long lowboard Viking-style rowed longship saw use well into the 15th century. Their main purpose in the north remained the transportation of soldiers to fight on the decks of the opposing ship (as, for example, at the Battle of Svolder or the Battle of Sluys).

Late medieval sailing warships resembled floating fortresses, with towers in the bow (boat), bows and at the stern (respectively, the forecastle and aftcastle). The large superstructure made these warships quite unstable, but the decisive defeats that the more mobile but considerably lower boarded longships suffered at the hands of high-boarded cogs in the 15th century ended the issue of which ship type would dominate northern European warfare.

Introduction of guns