Matthew Henson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

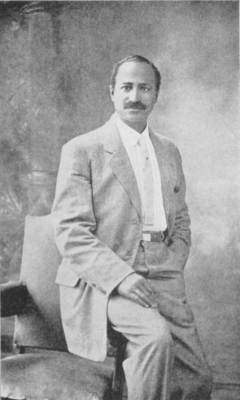

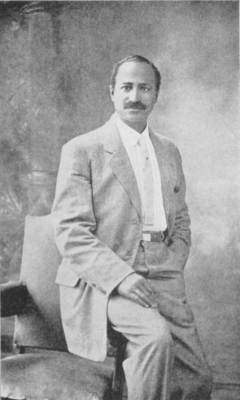

Matthew Alexander Henson (August 8, 1866March 9, 1955) was an African American explorer who accompanied

Globe Pequot, 2009, pp. 3–6 He is best known for his participation in the 1908–1909 expedition that claimed to have reached the

Matthew A. Henson website, 2012, accessed 2 October 2013 Matthew's mother died when Matthew was seven. His father Lemuel remarried to a woman named Caroline and had additional children with her, including daughters and a son. After his father died, Matthew was sent to live with his uncle, who lived in Washington, D.C. (Georgetown was made part of Washington, DC in 1871.) The uncle paid for a few years of education for Matthew but soon died. Henson attended a Black public school for the next six years, during the last of which he took a summer job washing dishes in a restaurant. His early years were marked by one especially memorable event. When he was 10 years old, he went to a ceremony honoring Abraham Lincoln, the American president who had fought so hard to preserve the Union during the Civil War and had issued the proclamation that had freed slaves in the occupied Confederate states in 1863. At the ceremony, Matthew was greatly inspired by a speech given by

While working at a Washington D.C. clothing store, B.H. Stinemetz and Sons, in November 1887, Henson met Commander Robert E. Peary. Learning of Henson's sea experience, Peary recruited him as an aide for his planned voyage and surveying expedition to Nicaragua, with four other men. Peary supervised 45 engineers on the canal survey in Nicaragua. Impressed with Henson's seamanship on that voyage, Peary recruited him as a colleague and he became "first man" in his expeditions.

After that, for more than 20 years, their expeditions were to the Arctic. Henson traded with the

While working at a Washington D.C. clothing store, B.H. Stinemetz and Sons, in November 1887, Henson met Commander Robert E. Peary. Learning of Henson's sea experience, Peary recruited him as an aide for his planned voyage and surveying expedition to Nicaragua, with four other men. Peary supervised 45 engineers on the canal survey in Nicaragua. Impressed with Henson's seamanship on that voyage, Peary recruited him as a colleague and he became "first man" in his expeditions.

After that, for more than 20 years, their expeditions were to the Arctic. Henson traded with the

in ''Daily News'' (Bowling Green, KY), 17 May 1992 He was remembered as the only non-Inuit who became skilled in driving the dog sleds and in training dog teams in the Inuit way. He was a skilled craftsman, often coming up with solutions for what the team needed in the harsh Arctic conditions; they learned to build

In 1908–09, Peary mounted his eighth attempt to reach the North Pole. The expedition was large, as Peary planned to use his system of setting up cached supplies along the way. When he and Henson boarded his ship ''Roosevelt'', leaving Greenland on August 18, 1909, they were accompanied by

Peary selected Henson and four Inuit as part of the team of six men who would make the final run to the Pole. Before the goal was reached, Peary could no longer continue on foot and rode in a dog sled. Various accounts say he was ill, was exhausted, or had frozen toes. He sent Henson ahead as a scout.

In a newspaper interview, Henson later said:

Henson proceeded to plant the American flag.

The claim by Peary's team to have reached the North Pole was widely debated in newspapers at the time, as was the competing claim by

In 1908–09, Peary mounted his eighth attempt to reach the North Pole. The expedition was large, as Peary planned to use his system of setting up cached supplies along the way. When he and Henson boarded his ship ''Roosevelt'', leaving Greenland on August 18, 1909, they were accompanied by

Peary selected Henson and four Inuit as part of the team of six men who would make the final run to the Pole. Before the goal was reached, Peary could no longer continue on foot and rode in a dog sled. Various accounts say he was ill, was exhausted, or had frozen toes. He sent Henson ahead as a scout.

In a newspaper interview, Henson later said:

Henson proceeded to plant the American flag.

The claim by Peary's team to have reached the North Pole was widely debated in newspapers at the time, as was the competing claim by

In 1912 Henson published a memoir about his arctic explorations, ''A Negro Explorer at the North Pole''. In this, he describes himself as a "general assistant, skilled craftsperson, interpreter, and laborer." He later collaborated with author Bradley Robinson on his 1947 biography, ''Dark Companion'', which told more about his life.

During the following decades, Admiral Peary received many honors for leading the expedition to the Pole, but Henson's contributions were largely ignored. In 1909 he was honored at dinners within the black community. Henson spent most of the next 30 years working on staff in the U.S. Customs House in New York, at the suggestion of

In 1912 Henson published a memoir about his arctic explorations, ''A Negro Explorer at the North Pole''. In this, he describes himself as a "general assistant, skilled craftsperson, interpreter, and laborer." He later collaborated with author Bradley Robinson on his 1947 biography, ''Dark Companion'', which told more about his life.

During the following decades, Admiral Peary received many honors for leading the expedition to the Pole, but Henson's contributions were largely ignored. In 1909 he was honored at dinners within the black community. Henson spent most of the next 30 years working on staff in the U.S. Customs House in New York, at the suggestion of

, Intercultural Issues, 2005–2009, Harvard Foundation, Harvard University, accessed 1 October 2013. He arranged a visit for them the following year to the United States, where they met American relatives from both families and visited their fathers' graves.Dr. S. Allen Counter, "North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo" (1991; Invisible Cities Press, reprint 2001). Anauakaq died in 1987. He and his wife Aviaq had five sons and a daughter, who have children of their own. While some still reside in Greenland, others have moved to Sweden or the United States. Several Inuit family members returned to Washington, D.C., in 1988 for the ceremony of reinterment of Henson and his wife Lucy at Arlington National Cemetery. Counter had petitioned President Ronald Reagan for this honor to gain recognition of Henson's contributions to Arctic exploration. Counter wrote a book about his finding Anauakaq and Kali, his research on Henson's life and contributions, historical racial relations, and the Inuits' meeting with Henson and Peary relatives in the United States, entitled ''North Pole Legacy: Black, White and Eskimo'' (1991). The material was adapted and produced as a film documentary by the same name.

"The real Taraji Henson"

''

* On October 19, 1909, Henson was the guest of honor at a dinner ceremony held by the Colored Citizens of New York, where he was honored by toasts and given a gold watch and chain.

* In 1937,

* On October 19, 1909, Henson was the guest of honor at a dinner ceremony held by the Colored Citizens of New York, where he was honored by toasts and given a gold watch and chain.

* In 1937,

"Arctic Autograph"

''Destination Freedom''

Miller, Floyd. ''Ahdoolo! Ahdoolo! The Biography of Matthew A. Henson''

New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1963, full text online at Internet Archive – no footnotes or sources * Potter, J. (2002). ''African American Firsts'', New York: Kensington Publishing Corp. * Robinson, Bradley. ''Dark Companion'', 1947 (biography of Henson) * ''American History'', Feb 2013, Vol. 47 Issue 6, p. 33 Brendle, Anna. * "Profile: African-American North Pole Explorer Matthew Henson." ''National Geographic News''. National Geographic Society, 28 Oct. 2010. * Dolan, Sean. ''Matthew Henson''. New York: Chelsea Juniors, 1992. * Johnson, Dolores. ''Onward''. Washington D.C.: National Geographic, 1949. * "On Top Of The World" ''American History'' 47.6 (2013): 33–41. ''History Reference Center''. * "Robert Peary." ''American History''. ABC-CLIO, 2015. * Schwartz, Simon (2015) ''First Man: Reimagining Matthew Henson''. Minneapolis: Graphic Universe/Lerner Publishing Group

"Matthew A. Henson"

at ArlingtonCemetery•org, an unofficial website (archived page)

Matthew A. Henson

website by Bradley Robinson (son of 1947 biographer)

Intercultural Issues, 2005–2009, Harvard Foundation, Harvard University

{{DEFAULTSORT:Henson, Matthew 1866 births 1955 deaths People from Charles County, Maryland American polar explorers Explorers of the Arctic Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Recipients of the Cullum Geographical Medal 20th-century American writers 20th-century American male writers 20th-century African-American writers African-American male writers

Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He is best known for, in Apri ...

on seven voyages to the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada ( Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm ( Greenland), Finland, Iceland ...

over a period of nearly 23 years. They spent a total of 18 years on expeditions together.Deirdre C. Stam, "Introduction to The Explorers Club Edition," ''Matthew A. Henson's Historic Arctic Journey: The Classic Account of One of the World's Greatest Black Explorers''Globe Pequot, 2009, pp. 3–6 He is best known for his participation in the 1908–1909 expedition that claimed to have reached the

geographic North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

on April 6, 1909. Henson said he was the first of their party to reach the pole.

Henson was born in Nanjemoy, Maryland, to sharecropper

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

parents who were free Black Americans before the Civil War. He spent most of his early life in Washington, D.C., but left school at the age of twelve to work as a cabin boy

''Cabin Boy'' is a 1994 American fantasy comedy film, directed by Adam Resnick and co-produced by Tim Burton, which starred comedian Chris Elliott. Elliott co-wrote the film with Resnick. Both Elliott and Resnick worked for ''Late Night with Davi ...

. He later returned to Washington and worked as a salesclerk at a good department store. One of his customers was Robert Peary, who in 1887 hired him as a personal valet. At the time, Peary was working on the Nicaragua Canal

The Nicaraguan Canal ( es, Canal de Nicaragua), formally the Nicaraguan Canal and Development Project (also referred to as the Nicaragua Grand Canal, or the Grand Interoceanic Canal) was a proposed shipping route through Nicaragua to connect t ...

.

Their first Arctic expedition together was in 1891–92. Henson served as a navigator and craftsman, and was known as Peary's "first man". Like Peary, he studied Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, ...

survival techniques.

During their 1908–09 expedition to Greenland, Henson was one of the six men – including Peary and four Inuit assistants – who claimed to have been the first to reach the geographic North Pole. In interviews, Henson identified as the first member of the party to reach what they believed was the pole. Their claim had gained widespread acceptance but in 1989, Wally Herbert published research that found that their expedition records were unreliable and indicated an implausibly high speed during their final rush for the pole, and that the men could have fallen short of the pole due to navigational errors.

Henson achieved a degree of fame as a result of participating in the expedition, and in 1912, he published a memoir titled ''A Negro Explorer at the North Pole''. As he approached old age, his exploits received renewed attention. In 1937, he was the first African American to be made a life member of The Explorers Club

The Explorers Club is an American-based international multidisciplinary professional society with the goal of promoting scientific exploration and field study. The club was founded in New York City in 1904, and has served as a meeting point fo ...

; in 1948 he was elevated to the club's highest level of membership. In 1944, Henson was awarded the Peary Polar Expedition Medal

The Peary Polar Expedition Medal was a commemorative medal awarded to six of the participants of the 1908–1909 Expedition to the North Pole, led by Robert Peary. Authorized by Congress in 1944, the silver medals were presented by the Secretary ...

, and he was received at the White House by Presidents Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Frankli ...

and Dwight Eisenhower. In 1988, he and his wife were re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

. In 2000, Henson posthumously was awarded the Hubbard Medal

The Hubbard Medal is awarded by the National Geographic Society for distinction in exploration, discovery, and research. The medal is named for Gardiner Greene Hubbard, first National Geographic Society president. It is made of gold and is tr ...

by the National Geographic Society. In September 2021, the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; french: link=yes, Union astronomique internationale, UAI) is a nongovernmental organisation with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreach ...

named a lunar crater

Lunar craters are impact craters on Earth's Moon. The Moon's surface has many craters, all of which were formed by impacts. The International Astronomical Union currently recognizes 9,137 craters, of which 1,675 have been dated.

History

The wor ...

after him.

Early life and education

Henson was born on August 8, 1866 on his parents' farm east of the Potomac River in Charles County, Maryland to sharecroppers who had beenfree people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

. Matthew's parents were subjected to attacks by the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Ca ...

and other white supremacist groups, who terrorized southern freedmen and former free people of color after the Civil War.

To escape from racial violence in southern Maryland, the Henson family sold the farm in 1867 and moved to Georgetown, then still an independent town adjacent to the national capital. He had an older sister S., born in 1864, and two younger sisters Eliza and M.Bradley Robinson, "Matthew Henson genealogy"Matthew A. Henson website, 2012, accessed 2 October 2013 Matthew's mother died when Matthew was seven. His father Lemuel remarried to a woman named Caroline and had additional children with her, including daughters and a son. After his father died, Matthew was sent to live with his uncle, who lived in Washington, D.C. (Georgetown was made part of Washington, DC in 1871.) The uncle paid for a few years of education for Matthew but soon died. Henson attended a Black public school for the next six years, during the last of which he took a summer job washing dishes in a restaurant. His early years were marked by one especially memorable event. When he was 10 years old, he went to a ceremony honoring Abraham Lincoln, the American president who had fought so hard to preserve the Union during the Civil War and had issued the proclamation that had freed slaves in the occupied Confederate states in 1863. At the ceremony, Matthew was greatly inspired by a speech given by

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

, an escaped slave and renowned orator, the longtime leading figure in the Black American community. Douglass called upon Black people to vigorously pursue educational opportunities and battle racial prejudice.

At the age of 12, the youth made his way to Baltimore, Maryland, a busy port. He went to sea as a cabin boy on the merchant ship ''Katie Hines,'' traveling to ports in China, Japan, Africa, and the Russian Arctic seas. The ship's leader, Captain Childs, took Henson under his wing and taught him to read and write.

Exploration

While working at a Washington D.C. clothing store, B.H. Stinemetz and Sons, in November 1887, Henson met Commander Robert E. Peary. Learning of Henson's sea experience, Peary recruited him as an aide for his planned voyage and surveying expedition to Nicaragua, with four other men. Peary supervised 45 engineers on the canal survey in Nicaragua. Impressed with Henson's seamanship on that voyage, Peary recruited him as a colleague and he became "first man" in his expeditions.

After that, for more than 20 years, their expeditions were to the Arctic. Henson traded with the

While working at a Washington D.C. clothing store, B.H. Stinemetz and Sons, in November 1887, Henson met Commander Robert E. Peary. Learning of Henson's sea experience, Peary recruited him as an aide for his planned voyage and surveying expedition to Nicaragua, with four other men. Peary supervised 45 engineers on the canal survey in Nicaragua. Impressed with Henson's seamanship on that voyage, Peary recruited him as a colleague and he became "first man" in his expeditions.

After that, for more than 20 years, their expeditions were to the Arctic. Henson traded with the Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, ...

and mastered the Inuit language

The Inuit languages are a closely related group of indigenous American languages traditionally spoken across the North American Arctic and adjacent subarctic, reaching farthest south in Labrador. The related Yupik languages (spoken in wester ...

; they called him ''Mahri-Pahluk.''Stephanie Schorow (AP), "Descendant of Black man and Eskimo woman are unique"in ''Daily News'' (Bowling Green, KY), 17 May 1992 He was remembered as the only non-Inuit who became skilled in driving the dog sleds and in training dog teams in the Inuit way. He was a skilled craftsman, often coming up with solutions for what the team needed in the harsh Arctic conditions; they learned to build

igloos

An igloo (Inuit languages: , Inuktitut syllabics (plural: )), also known as a snow house or snow hut, is a type of shelter built of suitable snow.

Although igloos are often associated with all Inuit, they were traditionally used only ...

out of snow, for mobile housing as they traveled. His and Peary's teams covered thousands of miles in dog sleds and reached the "Farthest North

Farthest North describes the most northerly latitude reached by explorers, before the first successful expedition to the North Pole rendered the expression obsolete. The Arctic polar regions are much more accessible than those of the Antarctic, as ...

" point of any Arctic expedition until 1909.

1908–09 expedition

In 1908–09, Peary mounted his eighth attempt to reach the North Pole. The expedition was large, as Peary planned to use his system of setting up cached supplies along the way. When he and Henson boarded his ship ''Roosevelt'', leaving Greenland on August 18, 1909, they were accompanied by

Peary selected Henson and four Inuit as part of the team of six men who would make the final run to the Pole. Before the goal was reached, Peary could no longer continue on foot and rode in a dog sled. Various accounts say he was ill, was exhausted, or had frozen toes. He sent Henson ahead as a scout.

In a newspaper interview, Henson later said:

Henson proceeded to plant the American flag.

The claim by Peary's team to have reached the North Pole was widely debated in newspapers at the time, as was the competing claim by

In 1908–09, Peary mounted his eighth attempt to reach the North Pole. The expedition was large, as Peary planned to use his system of setting up cached supplies along the way. When he and Henson boarded his ship ''Roosevelt'', leaving Greenland on August 18, 1909, they were accompanied by

Peary selected Henson and four Inuit as part of the team of six men who would make the final run to the Pole. Before the goal was reached, Peary could no longer continue on foot and rode in a dog sled. Various accounts say he was ill, was exhausted, or had frozen toes. He sent Henson ahead as a scout.

In a newspaper interview, Henson later said:

Henson proceeded to plant the American flag.

The claim by Peary's team to have reached the North Pole was widely debated in newspapers at the time, as was the competing claim by Frederick Cook

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician, and ethnographer who claimed to have reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908. That was nearly a year before Robert Peary, who similarly claim ...

. The National Geographic Society, as well as, the Naval Affairs Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives both credited Peary's team with having reached the North Pole. Others remained doubtful. A reassessment of Peary's notebook by British polar explorer Wally Herbert in 1988 found it "lacking in essential data", thus, renewing doubts about Peary's claim.

Later life

In 1912 Henson published a memoir about his arctic explorations, ''A Negro Explorer at the North Pole''. In this, he describes himself as a "general assistant, skilled craftsperson, interpreter, and laborer." He later collaborated with author Bradley Robinson on his 1947 biography, ''Dark Companion'', which told more about his life.

During the following decades, Admiral Peary received many honors for leading the expedition to the Pole, but Henson's contributions were largely ignored. In 1909 he was honored at dinners within the black community. Henson spent most of the next 30 years working on staff in the U.S. Customs House in New York, at the suggestion of

In 1912 Henson published a memoir about his arctic explorations, ''A Negro Explorer at the North Pole''. In this, he describes himself as a "general assistant, skilled craftsperson, interpreter, and laborer." He later collaborated with author Bradley Robinson on his 1947 biography, ''Dark Companion'', which told more about his life.

During the following decades, Admiral Peary received many honors for leading the expedition to the Pole, but Henson's contributions were largely ignored. In 1909 he was honored at dinners within the black community. Henson spent most of the next 30 years working on staff in the U.S. Customs House in New York, at the suggestion of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

.

He later gained renewed attention. In 1937 Henson was admitted as a member to the prestigious Explorers Club

The Explorers Club is an American-based international multidisciplinary professional society with the goal of promoting scientific exploration and field study. The club was founded in New York City in 1904, and has served as a meeting point fo ...

in New York City, and in 1948 he was made an honorary member, of whom there are only 20 per year. In 1944 Congress awarded him and five other Peary aides duplicates of the Peary Polar Expedition Medal

The Peary Polar Expedition Medal was a commemorative medal awarded to six of the participants of the 1908–1909 Expedition to the North Pole, led by Robert Peary. Authorized by Congress in 1944, the silver medals were presented by the Secretary ...

, a silver medal given to Peary. Presidents Truman and Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

both honored Henson before he died in 1955.

Henson died in the Bronx, New York on March 9, 1955 at the age of 88. He was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery and survived by his wife Lucy. After her death in 1968, she was buried with him. In 1988, both their bodies were moved for reinterment at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

, accompanied by a commemoration ceremony.

Family

Henson married Eva Flint in 1891, but their marriage did not survive their long periods of separation, and they divorced in 1897. He later married Lucy Ross in New York City on September 7, 1907. They had no children.Counter, S. Allen, "The Henson Family", ''National Geographic,'' 174, September 1988, pp. 414–429. During the extended expeditions to Greenland, Henson and Peary both tookInuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, ...

women as " country wives" and fathered children with them. With his concubine, known as Akatingwah, Henson fathered his only child, a son named Anauakaq, born in 1906. Anauakaq's children are Henson's only descendants. After 1909, Henson never saw Akatingwah or his son again; other explorers sometimes updated him about them. The existence of Henson's and Peary's descendants first was made public by French explorer and ethnologist Jean Malaurie

Jean Malaurie (born 22 December 1922) is a French cultural anthropologist, explorer, geographer, physicist, and writer. He and Kutsikitsoq, an Inuk, were the first two men to reach the North Geomagnetic Pole on 29 May 1951.

He was a director of ...

who spent a year in Greenland in 1951–1952.

S. Allen Counter, a neuroscientist and director of the Harvard Foundation, had been interested in Henson's story and traveled in Greenland for research related to it. Learning of possible descendants of the explorers, he tracked down Henson's and Peary's sons, Anauakaq and Kali, respectively in 1986. By then the men were octogenarians.People: "Dr. S. Allen Counter", Intercultural Issues, 2005–2009, Harvard Foundation, Harvard University, accessed 1 October 2013. He arranged a visit for them the following year to the United States, where they met American relatives from both families and visited their fathers' graves.Dr. S. Allen Counter, "North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo" (1991; Invisible Cities Press, reprint 2001). Anauakaq died in 1987. He and his wife Aviaq had five sons and a daughter, who have children of their own. While some still reside in Greenland, others have moved to Sweden or the United States. Several Inuit family members returned to Washington, D.C., in 1988 for the ceremony of reinterment of Henson and his wife Lucy at Arlington National Cemetery. Counter had petitioned President Ronald Reagan for this honor to gain recognition of Henson's contributions to Arctic exploration. Counter wrote a book about his finding Anauakaq and Kali, his research on Henson's life and contributions, historical racial relations, and the Inuits' meeting with Henson and Peary relatives in the United States, entitled ''North Pole Legacy: Black, White and Eskimo'' (1991). The material was adapted and produced as a film documentary by the same name.

Extended family

Matthew Henson's only descendants were the children of his Inuit son and their children. According to S. Allen Counter, in his lifetime Henson had identified families of two nieces as being part of his extended birth family. They were Virginia Carter Brannum, daughter of Henson's sister Eliza Henson Carter of Washington, D.C., and Olive Henson Fulton of Boston, daughter of his half-brother. In a 1988 article, Counter noted that these two women had letters and photographs certifying their kinship. They were the only family members to attend Henson's funeral in 1955, along with his widow Lucy Ross Henson. Counter later recommended to the United States Navy and theNational Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society (NGS), headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest non-profit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, ...

that Audrey Mebane, daughter of Virginia Brannum, and Olive Henson Fulton be designated as family representatives for any ceremonies honoring Henson.

Henson is believed to be a brother of the great-great-grandfather of actress Taraji P. Henson.Tucker, Neely (October 6, 2011). Henson, spent most of her summers as a child in Scotland Neck, North Carolina

Scotland Neck is a town in Halifax County, North Carolina, United States. According to the 2010 census, the town population was 2,059. It is part of the Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina Micropolitan Statistical Area.

History

The Hoffman-Bowers ...

, a small town between Rocky Mount and Roanoke Rapids. It is about an hour and a half from Raleigh, North Carolina and 45 mins from the Virginia state line"The real Taraji Henson"

''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

''.

Legacy and honors

The Explorers Club

The Explorers Club is an American-based international multidisciplinary professional society with the goal of promoting scientific exploration and field study. The club was founded in New York City in 1904, and has served as a meeting point fo ...

, under its "polar" President Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (November 3, 1879 – August 26, 1962) was an Arctic explorer and ethnologist. He was born in Manitoba, Canada.

Early life

Stefansson, born William Stephenson, was born at Arnes, Manitoba, Canada, in 1879. His parents had ...

, invited Henson to join its ranks.

* In 1940, a public housing project, for affordable housing for Phoenix African Americans, was named after Matthew Henson. The former site of the project was recognized as part of a historic district by the Phoenix Historic Property Register

The Phoenix Historic Property Register is the official listing of the historic and prehistoric properties in the city of Phoenix, the capital and largest city, of the U.S. state of Arizona.

History

The register was established on 1986 with the ai ...

in June 2005. Only one courtyard with the original buildings remains.

* In 1940, Henson was honored with one of the 33 diorama

A diorama is a replica of a scene, typically a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as military vehicle mode ...

s at the American Negro Exposition

The American Negro Exposition, also known as the Black World's Fair and the Diamond Jubilee Exposition, was a world's fair held in Chicago from July until September in 1940, to celebrate the 75th anniversary (also known as a diamond jubilee) of t ...

in Chicago.

*In 1945, Henson and other Peary aides were given U.S. Navy medals for their Arctic achievements.

* In 1948, the Club awarded the explorer its highest rank of Honorary Member, an honor reserved for no more than 20 living members at a time."Peary Aide is Honored: Matthew Henson, 81, Made Member of Celebrated Club", ''New York Times,'' 12 May 1948.

* In 1954, Henson was invited to the White House

* Before his death in 1955, Henson received honorary doctoral degrees from Howard University and Morgan State University.

* On May 28, 1986, the United States Postal Service issued a 22 cent postage stamp in honor of Henson and Peary; they were previously honored in 1959, but not by name.

* In 1988 Henson and his wife Lucy were reinterred in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

, with a monument to his exploring achievements, near Peary's grave and monument. Many members from his Inuit descendants (Anauakaq's children) and extended American family attended.R. Drummond Ayres Jr., "Matt Henson, Aide at Pole, Rejoins Peary", ''New York Times'', 7 April 1988.

* In October 1996, the United States Navy commissioned USNS ''Henson'', a ''Pathfinder'' class Oceanographic Survey Ship, named in honor of Matthew Henson.

* In 2000, the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society (NGS), headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest non-profit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, ...

awarded the Hubbard Medal

The Hubbard Medal is awarded by the National Geographic Society for distinction in exploration, discovery, and research. The medal is named for Gardiner Greene Hubbard, first National Geographic Society president. It is made of gold and is tr ...

to Matthew A. Henson posthumously. The medal was presented to Henson's great-niece Audrey Mebane at the newly named Matthew A. Henson Earth Conservation Center in Washington, D.C.; in addition, the NGS established a scholarship in Henson's name.

* Places in Maryland named in Henson's honor include the following: Matthew Henson State Park in Aspen Hill, Maryland, Matthew Henson Middle School in Pomonkey, and elementary schools named for him in Baltimore and Palmer Park, Maryland.

* The Henson Glacier (Greenland) was named after him.

* In 2008–2009, a 100th anniversary expedition to the North Pole was undertaken in honor of Henson by Dwayne Fields.

* In October 2020, the previously named ''Columbus'' GPS Block III satellite was renamed after the launch as ''Matthew Henson''.

* In September 2021, on the proposal of an intern at the Lunar and Planetary Institute

The Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI) is a scientific research institute dedicated to study of the Solar System, its formation, evolution, and current state. The Institute is part of the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) and is supp ...

, a crater at the south pole of the Moon

The lunar south pole is the southernmost point on the Moon, at 90°S. It is of special interest to scientists because of the occurrence of water ice in permanently shadowed areas around it. The lunar south pole region features craters that are ...

, located between Sverdrup

In oceanography, the sverdrup (symbol: Sv) is a non- SI metric unit of volumetric flow rate, with equal to . It is equivalent to the SI derived unit cubic hectometer per second (symbol: hm3/s or hm3⋅s−1): 1 Sv is equal to 1 hm3/s. It is u ...

and de Gerlache

Baron Adrien Victor Joseph de Gerlache de Gomery (; 2 August 1866 – 4 December 1934) was a Belgian officer in the Belgian Royal Navy who led the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–99.

Early years

Born in Hasselt in eastern Belgium as t ...

craters, was named ''Henson'' after him.

Representation in media

* "Matthew Henson, Black Explorer" is part of the series "TheScooby-Doo

''Scooby-Doo'' is an American animated media franchise based on an animated television series launched in 1969 and continued through several derivative media. Writers Joe Ruby and Ken Spears created the original series, ''Scooby-Doo, Where Are ...

Gang: Black Explorers" released in 1978 by Hanna-Barbera Educational Filmstrips

''Hanna-Barbera Educational Filmstrips'' is a series of animated filmstrips of educational material produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions' educational division. The series ran from 1977 to 1980 for a total of 26 titles, featuring the studio's an ...

. Catalog number 52410.

*S. Allen Counter's book, ''North Pole Legacy: Black, White and Eskimo'' (1991), discusses the explorations, as well as Peary and Henson's "country wives" (Inuit women) and their part-Inuit descendants, and historical race relations. He made a film documentary by the same name, shown on the Monitor Channel in 1992.

* The 1998 TV movie '' Glory & Honor'' was about the Peary-Henson explorations and their lives. Henson was played by Delroy Lindo

Delroy George Lindo (born 18 November 1952) is an English-American actor. He is the recipient of such accolades as a NAACP Image Award, a Satellite Award, and nominations for a Drama Desk Award, a Helen Hayes Award, a Tony Award, two Critics' Ch ...

, and Henry Czerny played Robert Peary. The film won a Primetime Emmy

The Primetime Emmy Awards, or Primetime Emmys, are part of the extensive range of Emmy Awards for artistic and technical merit for the American television industry. Bestowed by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS), the Primetime E ...

and Lindo won a Golden Satellite Award for his performance.

* Henson's role in polar expeditions was included in E.L. Doctorow's novel ''Ragtime

Ragtime, also spelled rag-time or rag time, is a musical style that flourished from the 1890s to 1910s. Its cardinal trait is its syncopated or "ragged" rhythm. Ragtime was popularized during the early 20th century by composers such as Scott ...

'' (1975).

* Donna Jo Napoli

Donna Jo Napoli (born February 28, 1948) is an American writer of children's and young adult fiction, as well as a linguist. She currently is a professor at Swarthmore College teaching Linguistics in all different forms (music, Theater (structure ...

's young adult novel, ''North,'' is set against Henson's life and role in polar expeditions.

* In 2012, the German artist Simon Schwartz published a graphic novel about Henson, entitled ''Packeis'' (pack ice), which won the Max & Moritz Prize for the "Best German-language Comic Book." The novel was published in English as ''First Man: Reimagining Matthew Henson'' in 2015.

* In the graphic novel '' Sous le soleil de minuit'', published in 2015 by writer Juan Díaz Canales

Juan Díaz Canales is a Spanish comics artist and an animated film director, known as the co-creator of '' Blacksad''.

Biography

At an early age, Juan Díaz Canales became interested in comics and their creation, which progressed and broadened o ...

and artist Rubén Pellejero, Henson helps Corto Maltese in his Alaskan adventure in 1915.''Bajo el sol de medianoche'', Juan Díaz Canales

Juan Díaz Canales is a Spanish comics artist and an animated film director, known as the co-creator of '' Blacksad''.

Biography

At an early age, Juan Díaz Canales became interested in comics and their creation, which progressed and broadened o ...

and Rubén Pellejero, Norma Editorial

Norma Editorial is a Spanish comics publisher, with its headquarters in Barcelona.Home

Norma Editor ...

, Barcelona, 2015.

* Henson's story is featured in '' Kevin Hart's Guide to Black History'' on Netflix.

* Henson is named in response to the question "Who was the first man to set foot on the North Pole?" in ''Norma Editor ...

Stevie Wonder

Stevland Hardaway Morris ( Judkins; May 13, 1950), known professionally as Stevie Wonder, is an American singer-songwriter, who is credited as a pioneer and influence by musicians across a range of genres that include rhythm and blues, pop, sou ...

s song Black Man on the album ''Songs in the Key of Life

''Songs in the Key of Life'' is the eighteenth studio album by American singer, songwriter and musician Stevie Wonder. A double album, it was released on September 28, 1976, by Tamla Records, a division of Motown. It was recorded primarily at Crys ...

''.

* His life and the polar exploration is retold in the radio drama "Arctic Autograph", a presentation from ''Destination Freedom

''Destination Freedom'' was a weekly radio program produced by WMAQ in Chicago from 1948 to 1950 that presented biographical histories of prominent African-Americans such as George Washington Carver, Satchel Paige, Frederick Douglass, Harriet ...

''''Destination Freedom''

Notes

Further reading

* Counter, S. Allen, "The Henson Family", ''National Geographic'', 174, September 1988, pp. 414–429 * * Miles, J. H., Davis, J. J., Ferguson-Roberts, S. E., and Giles, R. G. (2001). ''Almanac of African American Heritage'', Paramus, NJ:Prentice Hall Press

Prentice Hall was an American major educational publisher owned by Savvas Learning Company. Prentice Hall publishes print and digital content for the 6–12 and higher-education market, and distributes its technical titles through the Safari B ...

.

Miller, Floyd. ''Ahdoolo! Ahdoolo! The Biography of Matthew A. Henson''

New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1963, full text online at Internet Archive – no footnotes or sources * Potter, J. (2002). ''African American Firsts'', New York: Kensington Publishing Corp. * Robinson, Bradley. ''Dark Companion'', 1947 (biography of Henson) * ''American History'', Feb 2013, Vol. 47 Issue 6, p. 33 Brendle, Anna. * "Profile: African-American North Pole Explorer Matthew Henson." ''National Geographic News''. National Geographic Society, 28 Oct. 2010. * Dolan, Sean. ''Matthew Henson''. New York: Chelsea Juniors, 1992. * Johnson, Dolores. ''Onward''. Washington D.C.: National Geographic, 1949. * "On Top Of The World" ''American History'' 47.6 (2013): 33–41. ''History Reference Center''. * "Robert Peary." ''American History''. ABC-CLIO, 2015. * Schwartz, Simon (2015) ''First Man: Reimagining Matthew Henson''. Minneapolis: Graphic Universe/Lerner Publishing Group

External links

* * * *"Matthew A. Henson"

at ArlingtonCemetery•org, an unofficial website (archived page)

Matthew A. Henson

website by Bradley Robinson (son of 1947 biographer)

Intercultural Issues, 2005–2009, Harvard Foundation, Harvard University

{{DEFAULTSORT:Henson, Matthew 1866 births 1955 deaths People from Charles County, Maryland American polar explorers Explorers of the Arctic Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Recipients of the Cullum Geographical Medal 20th-century American writers 20th-century American male writers 20th-century African-American writers African-American male writers