Massacres During The Greek War Of Independence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

There were numerous

There were numerous

Most of the Greeks in the Greek quarter of Constantinople were massacred. On

Most of the Greeks in the Greek quarter of Constantinople were massacred. On

The Turks and Egyptians ravaged several Greek islands during the Greek Revolution, including those of

The Turks and Egyptians ravaged several Greek islands during the Greek Revolution, including those of

There were numerous

There were numerous massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

s during the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

(1821-1829) perpetrated by both the Ottoman forces and the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

revolutionaries. The war was characterized by a lack of respect for civilian

Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not "combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant, b ...

life, and prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

on both sides of the conflict. Massacres of Greeks took place especially in Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionian ...

, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

, Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, Macedonia and the Aegean islands. Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

, Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

, Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, and Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

populations, who were identified with the Ottomans inhabiting the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

, suffered massacres, particularly where Greek forces were dominant. Settled Greek communities in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

, Crete, Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

and Southern Greece were wiped out, and settled Turkish, Albanian, Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, and smaller Jewish communities in the Peloponnese were destroyed.

Massacres of Greeks

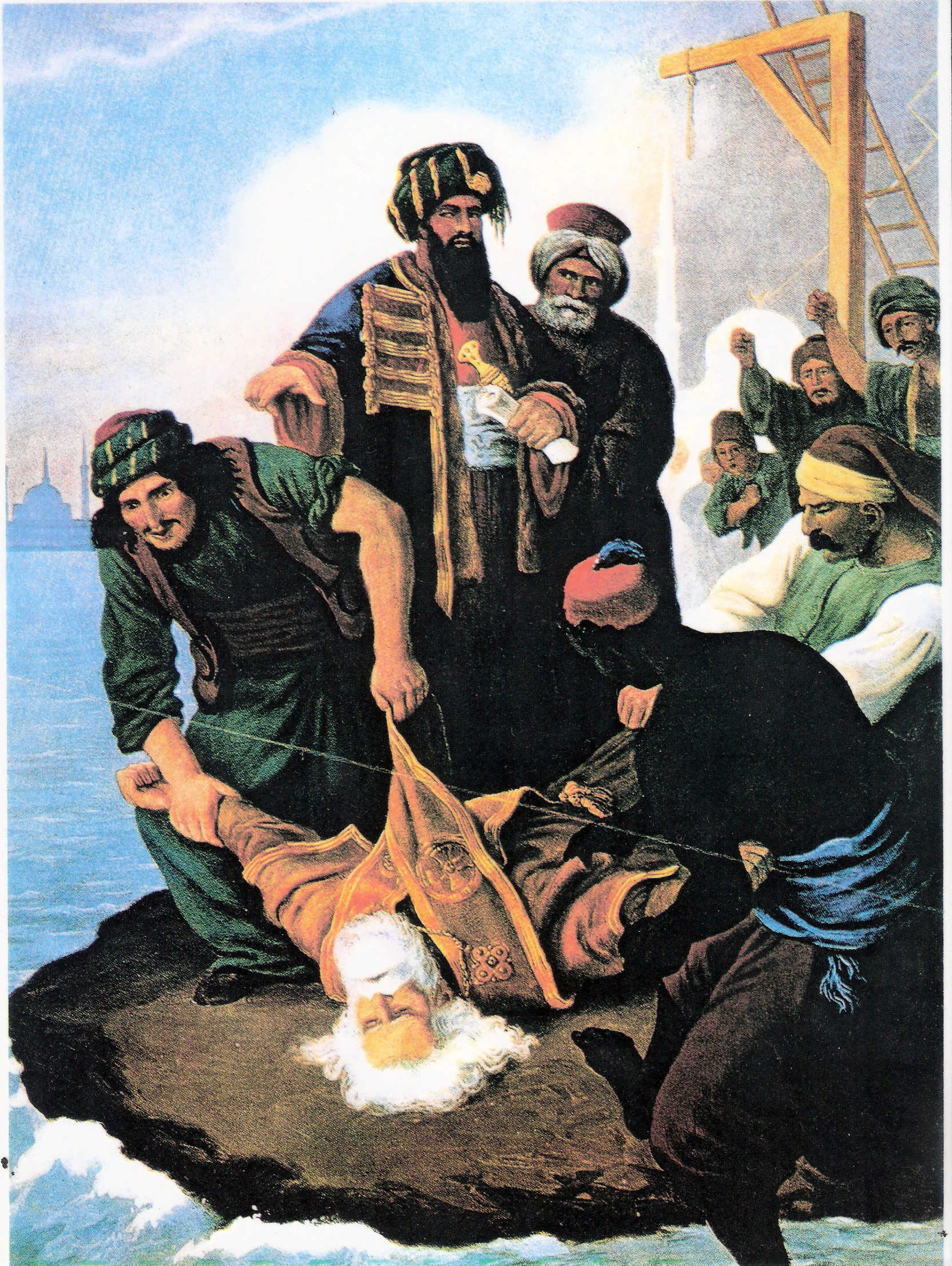

Constantinople

Easter Sunday

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the ''Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

, 9 April 1821, Gregory V

Gregory may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Gregory (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Gregory (surname), a surname

Places Australia

* Gregory, Queensland, a town in the Shire o ...

was hanged in the central outside portal of the Ecumenical Patriarchate

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople ( el, Οἰκουμενικὸν Πατριαρχεῖον Κωνσταντινουπόλεως, translit=Oikoumenikón Patriarkhíon Konstantinoupóleos, ; la, Patriarchatus Oecumenicus Constanti ...

by the Ottomans. His body was mutilated and thrown into the sea, where it was rescued by Greek sailors. One week later, the former Ecumenical Patriarch Cyril VI was hanged in the gate of the Adrianople

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

's cathedral. This was followed by the execution of two Metropolitans and twelve Bishops by the Turkish authorities. By the end of April, a number of prominent Greeks had been decapitated by Turkish forces in Constantinople, including Constantine Mourousis, Levidis Tsalikis, Dimitrios Paparigopoulos, Antonios Tsouras, and the Phanariotes

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots ( el, Φαναριώτες, ro, Fanarioți, tr, Fenerliler) were members of prominent Greeks, Greek families in Fener, Phanar (Φανάρι, modern ''Fener''), the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople whe ...

Petros Tsigris, Dimitrios Skanavis and Manuel Hotzeris, while Georgios Mavrocordatos

The House of Mavrocordatos (also Mavrocordato, Mavrokordatos, Mavrocordat, Mavrogordato or Maurogordato; el, Μαυροκορδάτος) is the name of a family of Phanariot Greeks originally from Chios, a branch of which was distinguished in the ...

was hanged. In May, the Metropolitans Gregorios of Derkon, Dorotheos of Adrianople, Ioannikios of Tyrnavos

Tyrnavos ( el, Τύρναβος) is a municipality in the Larissa regional unit, of the Thessaly region of Greece. It is the second-largest town of the Larissa regional unit, after Larissa. The town is near the mountains and the Thessalian Plain. ...

, Joseph of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

, and the Phanariote

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots ( el, Φαναριώτες, ro, Fanarioți, tr, Fenerliler) were members of prominent Greek families in Phanar (Φανάρι, modern ''Fener''), the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople where the Ecumeni ...

Georgios Callimachi

The House of Callimachi, Calimachi, or Kallimachi ( el, Καλλιμάχη, russian: Каллимаки, tr, Kalimakizade; originally ''Calmașul'' or ''Călmașu''), was a Phanariote family of mixed Moldavian (Romanian) and Greek origins. Origina ...

and Nikolaos Mourousis were decapitated on the Sultan's orders in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

.

Aegean Islands

Samothrace

Samothrace (also known as Samothraki, el, Σαμοθράκη, ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. It is a municipality within the Evros regional unit of Thrace. The island is long and is in size and has a population of 2,859 (2011 ...

(1821), Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mastic ...

(1822), Kos

Kos or Cos (; el, Κως ) is a Greek island, part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese by area, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 36,986 (2021 census), ...

, Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

, Kasos

Kasos (; el, Κάσος, ), also Casos, is a Greek island municipality in the Dodecanese. It is the southernmost island in the Aegean Sea, and is part of the Karpathos regional unit. The capital of the island is Fri. , its population was 1,22 ...

and Psara

Psara ( el, Ψαρά, , ; known in ancient times as /, /) is a Greek island in the Aegean Sea. Together with the small island of Antipsara (Population 4) it forms the municipality of Psara. It is part of the Chios regional unit, which is part of ...

(1824). The massacre of Samothrace occurred on September 1, 1821, where a Turkish fleet under the Kapudan Pasha

The Kapudan Pasha ( ota, قپودان پاشا, modern Turkish: ), was the Grand Admiral of the navy of the Ottoman Empire. He was also known as the ( ota, قپودان دریا, links=no, modern: , "Captain of the Sea"). Typically, he was based ...

Nasuhzade Ali Pasha killed most of the male population, took the women and children to slavery and burned down their homes. The Chios Massacre

The Chios massacre (in el, Η σφαγή της Χίου, ) was a catastrophe that resulted to the death, enslavement, and refuging of about four-fifths of the total population of Greeks on the island of Chios by Ottoman troops, during the G ...

of 1822 became one of the most notorious occurrences of the war. Mehmet Ali Mehmet Ali, Memet Ali or Mehmed Ali ("Ali"

''

Shortly after

Shortly after

According to historian William St. Clair, during the beginning of the Greek revolution upwards of twenty thousand Turkish men, women and children were killed by their Greek neighbors in a few weeks of slaughter. William St. Clair also argued that: "''with the beginning of the revolt, the bishops and priests exhorted their parishioners to exterminate infidel Muslims.''" St. Clair wrote:

According to historian William St. Clair, during the beginning of the Greek revolution upwards of twenty thousand Turkish men, women and children were killed by their Greek neighbors in a few weeks of slaughter. William St. Clair also argued that: "''with the beginning of the revolt, the bishops and priests exhorted their parishioners to exterminate infidel Muslims.''" St. Clair wrote:

The essence of the Greek-Turkish rivalry: national narrative and identity

'. Academic Paper. The London School of Economics and Political Science. p. 15. "On the Greek side, a case in point is the atrocious onslaught of the Greeks and Hellenised Christian Albanians against the city of Tripolitza in October 1821, which is justified by the Greeks ever since as the almost natural and predictable outcome of more than ‘400 years of slavery and dudgeon’. All the other similar atrocious acts all over Peloponnese, where apparently the whole population of Muslims (Albanian and Turkish-speakers), well over twenty thousand vanished from the face of the earth within a spat of a few months in 1821 is unsaid and forgotten, a case of ethnic cleansing through sheer slaughter (St Clair 2008: 1-9, 41-46) as are the atrocities committed in Moldavia (were the "Greek Revolution" actually started in February 1821) by prince Ypsilantis." to 30,000 only in Tripolitsa. Massacres of Turkish civilians started simultaneously with the outbreak of the revolt. Historian George Finlay claimed that the extermination of the Muslims in the rural districts was the result of a premeditated design and it proceeded more from the suggestions of men of letters, than from the revengeful feelings of the people. William St. Clair wrote that: ''"The orgy of genocide exhausted itself in the Peloponnese only when there were no more Turks to kill."''

''

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, dispatched his fleet to Kasos and on May 27, 1824 killed the population. A few weeks later, the fleet under Koca Hüsrev Mehmed Pasha

Koca Hüsrev Mehmed Pasha (also known as Koca Hüsrev Pasha; sometimes known in Western sources as just Husrev Pasha or Khosrew Pasha;Inalcık, Halil. Trans. by Gibb, H.A.R. ''The Encyclopaedia of Islam'', New Ed., Vol. V, Fascicules 79–80, p ...

destroyed the population of Psara.

Central Greece

Shortly after

Shortly after Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

's death in 1824, the Turks arrived to besiege the Greeks once more at Missolonghi

Missolonghi or Messolonghi ( el, Μεσολόγγι, ) is a municipality of 34,416 people (according to the 2011 census) in western Greece. The town is the capital of Aetolia-Acarnania regional unit, and the seat of the municipality of Iera Polis ...

. Turkish commander Reşid Mehmed Pasha

Reşid Mehmed Pasha, also known as Kütahı ( el, Μεχμέτ Ρεσίτ πασάς Κιουταχής, 1780–1836), was an Ottoman statesman and general who reached the post of Grand Vizier in the first half of the 19th century, playing an imp ...

was joined by Ibrahim Pasha, who crossed the Gulf of Corinth

The Gulf of Corinth or the Corinthian Gulf ( el, Κορινθιακός Kόλπος, ''Korinthiakόs Kόlpos'', ) is a deep inlet of the Ionian Sea, separating the Peloponnese from western mainland Greece. It is bounded in the east by the Isth ...

, and during the early part of 1826, Ibrahim had more artillery and supply brought in. However, his men were unable to storm the walls, and in 1826, following a one-year siege, Turkish-Egyptian forces conquered the city on Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is a Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Palm Sunday marks the first day of Holy ...

, and exterminated almost its entire population. The attack increased support for the Greek cause in western Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, with Eugène Delacroix

Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix ( , ; 26 April 1798 – 13 August 1863) was a French Romantic artist regarded from the outset of his career as the leader of the French Romantic school.Noon, Patrick, et al., ''Crossing the Channel: Britis ...

depicting the massacre in his painting ''Greece Expiring on the Ruins of Missolonghi''.

Crete

During the great massacre ofHeraklion

Heraklion or Iraklion ( ; el, Ηράκλειο, , ) is the largest city and the administrative capital of the island of Crete and capital of Heraklion regional unit. It is the fourth largest city in Greece with a population of 211,370 (Urban A ...

on 24 June 1821, remembered in the area as "the great ravage" ("ο μεγάλος αρπεντές", "o megalos arpentes"), the Turks also killed the metropolite of Crete, Gerasimos Pardalis, and five more bishops: Neofitos of Knossos, Joachim of Herronissos, Ierotheos of Lambis, Zacharias of Sitia and Kallinikos, the titular bishop of Diopolis.

After the Sultan's vassal in Egypt was sent to intervene with the Egyptian fleet on 1825, Muhammad Ali's son, Ibrahim, landed in Crete and began to massacre the majority Greek community.

Cyprus

In July 1821, the head of theCypriot Orthodox Church

The Church of Cyprus ( el, Ἐκκλησία τῆς Κύπρου, translit=Ekklisia tis Kyprou; tr, Kıbrıs Kilisesi) is one of the autocephalous Greek Orthodox churches that together with other Eastern Orthodox churches form the communion ...

Archbishop Kyprianos

Archbishop Kyprianos of Cyprus ( el, Αρχιεπίσκοπος Κύπρου Κυπριανός) was the head of the Cypriot Orthodox Church in the early 19th century at the time that the Greek War of Independence broke out.

Kyprianos was born i ...

, along with 486 prominent Greek Cypriots

Greek Cypriots or Cypriot Greeks ( el, Ελληνοκύπριοι, Ellinokýprioi, tr, Kıbrıs Rumları) are the ethnic Greek population of Cyprus, forming the island's largest ethnolinguistic community. According to the 2011 census, 659,115 r ...

, amongst them the Metropolitans Chrysanthethos of Paphos

Paphos ( el, Πάφος ; tr, Baf) is a coastal city in southwest Cyprus and the capital of Paphos District. In classical antiquity, two locations were called Paphos: Old Paphos, today known as Kouklia, and New Paphos.

The current city of Pap ...

, Meletios of Kition

Kition (Egyptian language, Egyptian: ; Phoenician language, Phoenician: , , or , ; Ancient Greek: , ; Latin: ) was a petty kingdom, city-kingdom on the southern coast of Cyprus (in present-day Larnaca). According to the text on the plaque clos ...

and Lavrentios of Kyrenia

Kyrenia ( el, Κερύνεια ; tr, Girne ) is a city on the northern coast of Cyprus, noted for its historic harbour and castle. It is under the ''de facto'' control of Northern Cyprus.

While there is evidence showing that the wider region ...

, were executed by hanging or beheading by the Ottomans in Nicosia

Nicosia ( ; el, Λευκωσία, Lefkosía ; tr, Lefkoşa ; hy, Նիկոսիա, romanized: ''Nikosia''; Cypriot Arabic: Nikusiya) is the largest city, capital, and seat of government of Cyprus. It is located near the centre of the Mesaor ...

.

The French consul M. Méchain reported on 15 September 1821 that the local pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, gener ...

, Küçük Mehmet, carried out several days of massacres in Cyprus since July 9 and continued on for forty days, despite the Vizier's command to end the plundering since 20 July 1821.

On October 15, a massive Turkish Cypriot

Turkish Cypriots or Cypriot Turks ( tr, Kıbrıs Türkleri or ''Kıbrıslı Türkler''; el, Τουρκοκύπριοι, Tourkokýprioi) are ethnic Turks originating from Cyprus. Following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1571, about 30,00 ...

mob seized and hanged an Archbishop, five Bishops, thirty six ecclesiastics, and hanged most of the Greek Cypriots in Larnaca

Larnaca ( el, Λάρνακα ; tr, Larnaka) is a city on the south east coast of Cyprus and the capital of the district of the same name. It is the third-largest city in the country, after Nicosia and Limassol, with a metro population of 144 ...

and the other towns. By September and October 1822, sixty two Greek Cypriot

villages and hamlets had entirely disappeared and many people, including clerics, were massacred.

Peloponnese

Historian David Brewer writes that in the first year of the revolution, a Turkish army descended on the city ofPatras

)

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 =

, demographics1_info2 =

, timezone1 = EET

, utc_offset1 = +2

, ...

and slaughtered all of the civilians of the settlement, razing the city.

The forces of Ibrahim Pasha were extremely brutal in the Peloponnese, burning the major port of Kalamata

Kalamáta ( el, Καλαμάτα ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula, after Patras, in southern Greece and the largest city of the homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia reg ...

to the ground and slaughtering the city's inhabitants; they also ravaged the countryside and were heavily involved in the slave trade.

Macedonia

Greek villages in Macedonia were destroyed, and many of the inhabitants were put to death. Thomas Gordon reports executions of Greek civilians inSerres

Sérres ( el, Σέρρες ) is a city in Macedonia, Greece, capital of the Serres regional unit and second largest city in the region of Central Macedonia, after Thessaloniki.

Serres is one of the administrative and economic centers of Northe ...

and Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

, beheadings of merchants and clergy, and seventy burnt villages.

In May 1821, the governor Yusuf Bey ordered his men to kill any Greeks in Thessaloniki they found in the streets. Haïroullah Effendi reported that then and "''for days and nights the air was filled with shouts, wails, screams''." The Metropolitan bishop was brought in chains, together with other leading notables, and they were tortured and executed in the square

In Euclidean geometry, a square is a regular quadrilateral, which means that it has four equal sides and four equal angles (90-degree angles, π/2 radian angles, or right angles). It can also be defined as a rectangle with two equal-length adj ...

of the flour market. Some were hanged from the plane trees around the Rotonda. Others were killed in the cathedral where they had fled for refuge, and their heads were gathered together as a present for Yusuf Bey.

In 1822, Abdul Abud, the Pasha of Thessaloniki, arrived on 14 March at the head of a 16,000 strong force and 12 cannons against Naousa. The Greeks defended Naousa with a force of 4,000 under the overall command of Zafeirakis Theodosiou Zafeirakis Theodosiou ( el, Ζαφειράκης Θεοδοσίου) (1772 - 1822) was a Greek ''prokritos'' (πρόκριτος), meaning political leader of Greeks during Ottoman rule, of Naousa, Imathia and an important figure of the Greek War of ...

and Anastasios Karatasos

Anastasios Karatasos ( el, Αναστάσιος Καρατάσος; 1764 – 21 January 1830) was a Greek military commander during the Greek War of Independence was born in the village of Dovras (Δοβράς or Δορβρά), Imathia and is cons ...

. The Turks attempted to take the town on 16 March 1822, and on 18 and 19 March, without success. On 24 March the Turks began a bombardment of the city walls that lasted for days. After requests for the town's surrender were dismissed by the Greeks, the Turks charged the gate of St George on 31 March. The Turkish attack failed but on 6 April, after receiving fresh reinforcements of some 3,000 men, the Turkish army finally overcame the Greek resistance and entered the city. In an infamous incident, many of the women committed suicide by falling down a cliff over the small river Arapitsa. Abdul Abud laid the town and surrounding area to waste. The Greek population was massacred. The destruction of Naousa marked the end of the Greek revolution in Macedonia in 1822.

Massacres of Turks and Muslims

Peloponnese

According to historian William St. Clair, during the beginning of the Greek revolution upwards of twenty thousand Turkish men, women and children were killed by their Greek neighbors in a few weeks of slaughter. William St. Clair also argued that: "''with the beginning of the revolt, the bishops and priests exhorted their parishioners to exterminate infidel Muslims.''" St. Clair wrote:

According to historian William St. Clair, during the beginning of the Greek revolution upwards of twenty thousand Turkish men, women and children were killed by their Greek neighbors in a few weeks of slaughter. William St. Clair also argued that: "''with the beginning of the revolt, the bishops and priests exhorted their parishioners to exterminate infidel Muslims.''" St. Clair wrote:

The Turks of Greece left few traces. They disappeared suddenly and finally in the spring of 1821 unmourned and unnoticed by the rest of the world....It was hard to believe then that Greece once contained a large population of Turkish descent, living in small communities all over the country, prosperous farmers, merchants, and officials, whose families had known no other home for hundreds of years...They were killed deliberately, without qualm or scruple, and there was no regrets either then or later.Atrocities toward the Turkish civilian population inhabiting the Peloponnese had started in

Achaia

Achaea () or Achaia (), sometimes transliterated from Greek as Akhaia (, ''Akhaïa'' ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Western Greece and is situated in the northwestern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. The ...

on the 28th of March, just with the beginning of the Greek revolt. On 2 April, the outbreak became general over the whole of Peloponnese and on that day many Turks were murdered in different places. On the third of April 1821, the Turks of Kalavryta

Kalavryta ( el, Καλάβρυτα) is a town and a municipality in the mountainous east-central part of the regional unit of Achaea, Greece. The town is located on the right bank of the river Vouraikos, south of Aigio, southeast of Patras and ...

surrendered upon promises of security which were afterwards violated. Followingly, massacres ensued against the Turkish civilians in the towns of Peloponnese that the Greek revolutionaries had captured.

The Turks in Monemvasia

Monemvasia ( el, Μονεμβασιά, Μονεμβασία, or ) is a town and municipality in Laconia, Greece. The town is located on a small island off the east coast of the Peloponnese, surrounded by the Myrtoan Sea. The island is connected t ...

, weakened by the famine opened the gates of the city, and laid down their weapons. Six hundred of them had already gone on board the brigs, when the Maniots

The Maniots or Maniates ( el, Μανιάτες) are the inhabitants of Mani Peninsula, located in western Laconia and eastern Messenia, in the southern Peloponnese, Greece. They were also formerly known as Mainotes and the peninsula as ''Maina''. ...

burst into the town and started murdering all those who had not yet reached to the shore or those who had chosen to stay in the town. Those on the ships meanwhile were stripped of their clothes, beaten and left on a desolate rock in the Aegean, instead of being deported to Asia Minor as promised. Only a few of them were saved by a French merchant, called M. Bonfort.

A general massacre ensued the fall of Navarino Navarino or Navarin may refer to:

Battle

* Battle of Navarino, 1827 naval battle off Navarino, Greece, now known as Pylos

Geography

* Navarino, Wisconsin, a town, United States

* Navarino (community), Wisconsin, an unincorporated community, Unite ...

on August 19, 1821. See Navarino Massacre

The siege of Navarino was one of the earliest battles of the Greek War of Independence. It resulted in one of a series of massacres which resulted in the extermination of the Turkish civilian population of the region.

Siege of the fortress

In ...

.

The worst Greek atrocity in terms of the numbers of victims involved was the massacre following the Fall of Tripolitsa in 1821:

For three days the miserable inhabitants were given over to lust and cruelty of a mob of savages. Neither sex nor age was spared. Women and children were tortured before being put to death. So great was the slaughter thatAlthough the total estimates of the casualties vary, the Turkish, Muslim Albanian and Jewish population of the Peloponnese had ceased to exist as a settled community. Some estimates of the Turkish and Muslim Albanian civilian deaths by the rebels range from 15,000, 20,000 or more out of 40,000 Muslim residentsHeraclides, Alexis (2011).Kolokotronis Kolokotronis (Greek: Κολοκοτρώνης) is a Greek surname. When used without any other context, it refers to the Greek warlord Theodoros Kolokotronis whose contribution to the Greek revolution of 1821 against the Ottoman Empire, was determin ...himself says that, from the gate to the citadel his horse’s hoofs never touched the ground. His path of triumph was carpeted with corpses. At the end of two days, the wretched remnant of the Mussulmans were deliberately collected, to the number of some two thousand souls, of every age and sex, but principally women and children, were led out to a ravine in the neighboring mountains and there butchered like cattle.

The essence of the Greek-Turkish rivalry: national narrative and identity

'. Academic Paper. The London School of Economics and Political Science. p. 15. "On the Greek side, a case in point is the atrocious onslaught of the Greeks and Hellenised Christian Albanians against the city of Tripolitza in October 1821, which is justified by the Greeks ever since as the almost natural and predictable outcome of more than ‘400 years of slavery and dudgeon’. All the other similar atrocious acts all over Peloponnese, where apparently the whole population of Muslims (Albanian and Turkish-speakers), well over twenty thousand vanished from the face of the earth within a spat of a few months in 1821 is unsaid and forgotten, a case of ethnic cleansing through sheer slaughter (St Clair 2008: 1-9, 41-46) as are the atrocities committed in Moldavia (were the "Greek Revolution" actually started in February 1821) by prince Ypsilantis." to 30,000 only in Tripolitsa. Massacres of Turkish civilians started simultaneously with the outbreak of the revolt. Historian George Finlay claimed that the extermination of the Muslims in the rural districts was the result of a premeditated design and it proceeded more from the suggestions of men of letters, than from the revengeful feelings of the people. William St. Clair wrote that: ''"The orgy of genocide exhausted itself in the Peloponnese only when there were no more Turks to kill."''

Central Greece

InAthens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, 1,150 Turks, of whom only 180 were capable of bearing arms, surrendered upon promises of security. W. Alison Phillips noted that: ''A scene of horror followed which has only too many parallels during the course of this horrible war.''

Vrachori, modern day Agrinio

Agrinio (Greek: Αγρίνιο, , Latin: ''Agrinium'') is the largest city of the Aetolia-Acarnania regional unit of Greece and its largest municipality, with 106,053 inhabitants. It is the economical center of Aetolia-Acarnania, although its capi ...

, was an important town in West-Central Greece. It contained, besides the Christian population, some five hundred Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

families and about two hundred Jews. The massacres in Vrachori commenced with the Jews and soon Musulmans shared the same fate.

Aegean Islands

There were also massacres towards the Muslim inhabitants of the islands in the Aegean Sea, in the early years of the Greek revolt. According to historian William St. Clair, one of the aims of the Greek revolutionaries was to embroil as many Greek communities as possible in their struggle. Their technique was ''"to engineer some atrocity against the local Turkish population"'', so that these different Greek communities would have to ally themselves with the revolutionaries fearing a retaliation from the Ottomans. In such a case, in March 1821, Greeks from Samos island had landed in the Chios and attacked the Muslim population living in that island. The crews and passengers of Turkish ships captured by Greek cruisers were often put to death: two Ηydriot brigs captured a Turkish ship laden with a valuable cargo, and carrying a number of passengers. Among these was a recently deposed Sheikh-ul-Islam, or patriarch of the Orthodox Muslims, who was said to be going to Mecca for pilgrimage. It was his efforts to prevent the cruel reprisals which, at Constantinople, followed the news of the massacres in Peloponnese, which brought him into disfavor, and caused his exile. There were also several other Turkish families on board. British historian of the Greek revolt, W. Alison Phillips, noted (drawing from Finlay): ''The Hydriots murdered them all in cold blood, helpless old men, ladies of rank, beautiful slaves, and little children were butchered like cattle. The venerable old man, whose crime had been an excess of zeal on behalf of the Greeks, was forced to see his family outraged and murdered before his eyes...''Massacres of Jews

Steven Bowman claims that despite the fact that many Jews were killed, they were not targeted specifically: "''Such a tragedy seems to be more a side-effect of the butchering of the Turks ofTripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

s, the last Ottoman stronghold in the South where the Jews had taken refuge from the fighting, than a specific action against Jews per se.''" However, in the case of Vrachori, a massacre of a Jewish population occurred first, and the Jewish population in the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

regardless was effectively decimated, unlike that of the considerable Jewish populations of the Aegean, Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich ...

and other areas of Greece in the several following conflicts between Greeks and the Ottomans later in the century. Many Jews within Greece and throughout Europe were however supporters of the Greek revolt, and many assisted the Greek cause. Following the state's establishment, it also then attracted many Jewish immigrants from the Ottoman Empire, as one of the first European states in the world to grant legal equality to Jews.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* General Makriyannis, ''Ἀπομνημονεύματα'' (Memoirs), Athens: 1907 (preface by Yannis Vlahogiannis; in Greek). * {{Greek War of Independence, state=collapsedMassacres

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...