Mary Shelley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (; ; 30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was an English novelist who wrote the

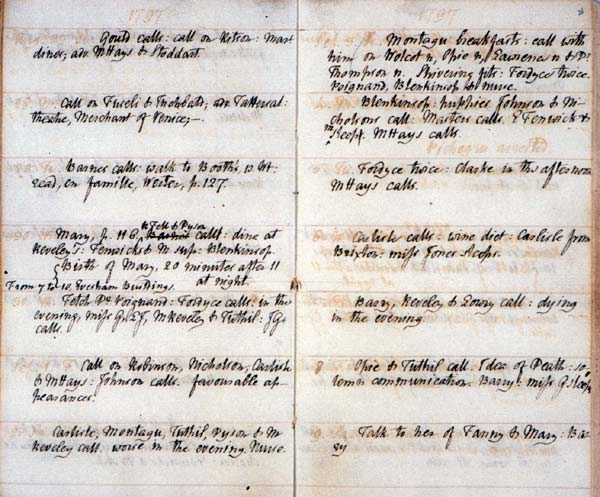

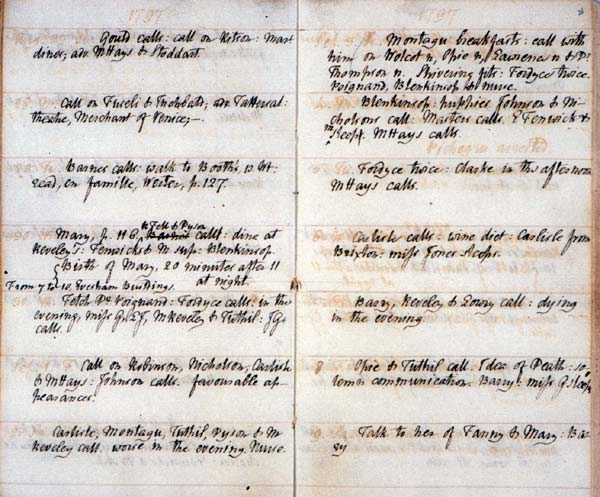

Mary Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in

Mary Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in  Though Mary Godwin received little formal education, her father tutored her in a broad range of subjects. He often took the children on educational outings, and they had access to his library and to the many intellectuals who visited him, including the

Though Mary Godwin received little formal education, her father tutored her in a broad range of subjects. He often took the children on educational outings, and they had access to his library and to the many intellectuals who visited him, including the

Mary Godwin may have first met the radical poet-philosopher

Mary Godwin may have first met the radical poet-philosopher  The situation awaiting Mary Godwin in England was fraught with complications, some of which she had not foreseen. Either before or during the journey, she had become pregnant. She and Percy now found themselves penniless, and, to Mary's genuine surprise, her father refused to have anything to do with her. The couple moved with Claire into lodgings at Somers Town, and later, Nelson Square. They maintained their intense programme of reading and writing, and entertained Percy Shelley's friends, such as

The situation awaiting Mary Godwin in England was fraught with complications, some of which she had not foreseen. Either before or during the journey, she had become pregnant. She and Percy now found themselves penniless, and, to Mary's genuine surprise, her father refused to have anything to do with her. The couple moved with Claire into lodgings at Somers Town, and later, Nelson Square. They maintained their intense programme of reading and writing, and entertained Percy Shelley's friends, such as

In May 1816, Mary Godwin, Percy Shelley, and their son travelled to

In May 1816, Mary Godwin, Percy Shelley, and their son travelled to

Frankenstein's hour of creation identified by astronomers

'', ''The Guardian'', 25 September 2011 (retrieved 5 January 2014)

One of the party's first tasks on arriving in Italy was to hand Alba over to Byron, who was living in

One of the party's first tasks on arriving in Italy was to hand Alba over to Byron, who was living in  In the summer of 1822, a pregnant Mary moved with Percy, Claire, and Edward and Jane Williams to the isolated Villa Magni, at the sea's edge near the hamlet of San Terenzo in the Bay of Lerici. Once they were settled in, Percy broke the "evil news" to Claire that her daughter Allegra had died of

In the summer of 1822, a pregnant Mary moved with Percy, Claire, and Edward and Jane Williams to the isolated Villa Magni, at the sea's edge near the hamlet of San Terenzo in the Bay of Lerici. Once they were settled in, Percy broke the "evil news" to Claire that her daughter Allegra had died of

In the mid-1840s, Mary Shelley found herself the target of three separate blackmailers. In 1845, an Italian political exile called Gatteschi, whom she had met in Paris, threatened to publish letters she had sent him. A friend of her son's bribed a police chief into seizing Gatteschi's papers, including the letters, which were then destroyed. Shortly afterwards, Mary Shelley bought some letters written by herself and Percy Bysshe Shelley from a man calling himself G. Byron and posing as the illegitimate son of the late

In the mid-1840s, Mary Shelley found herself the target of three separate blackmailers. In 1845, an Italian political exile called Gatteschi, whom she had met in Paris, threatened to publish letters she had sent him. A friend of her son's bribed a police chief into seizing Gatteschi's papers, including the letters, which were then destroyed. Shortly afterwards, Mary Shelley bought some letters written by herself and Percy Bysshe Shelley from a man calling himself G. Byron and posing as the illegitimate son of the late

Gothic novel

Gothic fiction, sometimes called Gothic horror in the 20th century, is a loose literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name is a reference to Gothic architecture of the European Middle Ages, which was characteristic of the settings of ea ...

''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus

''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' is an 1818 novel written by English author Mary Shelley. ''Frankenstein'' tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a sapient creature in an unorthodox scientific exp ...

'' (1818), which is considered an early example of science fiction. She also edited and promoted the works of her husband, the Romantic poet

Romantic poetry is the poetry of the Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. It involved a reaction against prevailing Enlightenment ideas of the 18t ...

and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achie ...

. Her father was the political philosopher

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous for ...

and her mother was the philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

.

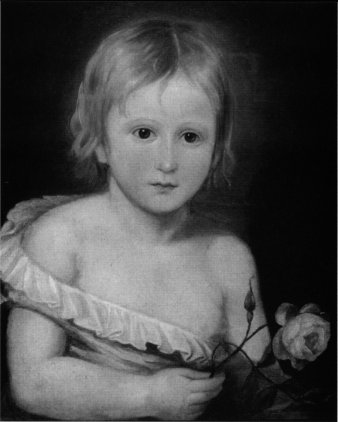

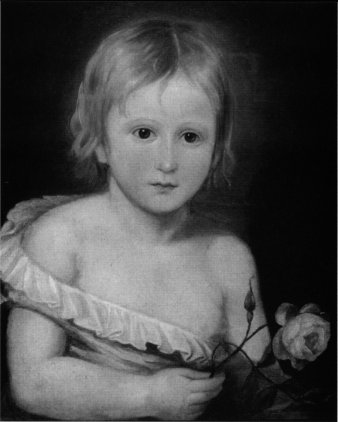

Mary's mother died less than a fortnight after giving birth to her. She was raised by her father, who provided her with a rich if informal education, encouraging her to adhere to his own anarchist political theories. When she was four, her father married a neighbour, Mary Jane Clairmont, with whom Mary came to have a troubled relationship.

In 1814, Mary began a romance with one of her father's political followers, Percy Bysshe Shelley, who was already married. Together with her stepsister, Claire Clairmont

Clara Mary Jane Clairmont (27 April 1798 – 19 March 1879), or Claire Clairmont as she was commonly known, was the stepsister of the writer Mary Shelley and the mother of Lord Byron's daughter Allegra. She is thought to be the subject of a poe ...

, she and Percy left for France and travelled through Europe. Upon their return to England, Mary was pregnant with Percy's child. Over the next two years, she and Percy faced ostracism, constant debt and the death of their prematurely born daughter. They married in late 1816, after the suicide of Percy Shelley's first wife, Harriet.

In 1816, the couple and Mary's stepsister famously spent a summer with Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

and John William Polidori

John William Polidori (7 September 1795 – 24 August 1821) was a British writer and physician. He is known for his associations with the Romantic movement and credited by some as the creator of the vampire genre of fantasy

Fantasy is a ...

near Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, Switzerland, where Shelley conceived the idea for her novel ''Frankenstein''. The Shelleys left Britain in 1818 for Italy, where their second and third children died before Shelley gave birth to her last and only surviving child, Percy Florence Shelley

Sir Percy Florence Shelley, 3rd Baronet (12 November 1819 – 5 December 1889) was the son of the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his second wife, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, novelist and author of ''Frankenstein''. He was the only child ...

. In 1822, her husband drowned when his sailing boat sank during a storm near Viareggio

Viareggio () is a city and ''comune'' in northern Tuscany, Italy, on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea. With a population of over 62,000, it is the second largest city within the province of Lucca, after Lucca.

It is known as a seaside resort as ...

. A year later, Shelley returned to England and from then on devoted herself to the upbringing of her son and a career as a professional author. The last decade of her life was dogged by illness, most likely caused by the brain tumour which killed her at age 53.

Until the 1970s, Shelley was known mainly for her efforts to publish her husband's works and for her novel ''Frankenstein'', which remains widely read and has inspired many theatrical and film adaptations. Recent scholarship has yielded a more comprehensive view of Shelley's achievements. Scholars have shown increasing interest in her literary output, particularly in her novels, which include the historical novels '' Valperga'' (1823) and ''Perkin Warbeck

Perkin Warbeck ( 1474 – 23 November 1499) was a pretender to the English throne claiming to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, who was the second son of Edward IV and one of the so-called "Princes in the Tower". Richard, were he alive, ...

'' (1830), the apocalyptic novel ''The Last Man

''The Last Man'' is an apocalyptic, dystopian science fiction novel by Mary Shelley, first published in 1826. The narrative concerns Europe in the late 21st century, ravaged by a mysterious plague pandemic that rapidly sweeps across the entire ...

'' (1826) and her final two novels, ''Lodore

''Lodore'', also published under the title ''The Beautiful Widow'', is the penultimate novel by Romantic novelist Mary Shelley, completed in 1833 and published in 1835.

Plot and themes

In ''Lodore'', Shelley focused her theme of power and resp ...

'' (1835) and '' Falkner'' (1837). Studies of her lesser-known works, such as the travel book ''Rambles in Germany and Italy

''Rambles in Germany and Italy, in 1840, 1842, and 1843'' is a travel narrative by the British Romantic author Mary Shelley. Issued in 1844, it is her last published work. Published in two volumes, the text describes two European trips that ...

'' (1844) and the biographical articles for Dionysius Lardner

Professor Dionysius Lardner FRS FRSE (3 April 179329 April 1859) was an Irish scientific writer who popularised science and technology, and edited the 133-volume '' Cabinet Cyclopædia''.

Early life in Dublin

He was born in Dublin on 3 Apr ...

's '' Cabinet Cyclopaedia'' (1829–1846), support the growing view that Shelley remained a political radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

throughout her life. Shelley's works often argue that cooperation and sympathy, particularly as practised by women in the family, were the ways to reform civil society. This view was a direct challenge to the individualistic Romantic ethos promoted by Percy Shelley and the Enlightenment political theories articulated by her father, William Godwin.

Life and career

Early life

Mary Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in

Mary Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in Somers Town, London

Somers Town is an inner-city district in North West London. It has been strongly influenced by the three mainline north London railway termini: Euston (1838), St Pancras (1868) and King's Cross (1852), together with the Midland Railway Some ...

, in 1797. She was the second child of the feminist philosopher, educator, and writer Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

and the first child of the philosopher, novelist, and journalist William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous for ...

. Wollstonecraft died of puerperal fever shortly after Mary was born. Godwin was left to bring up Mary, along with her older half-sister, Fanny Imlay

Frances Imlay (14 May 1794 – 9 October 1816), also known as Fanny Godwin and Frances Wollstonecraft, was the illegitimate daughter of the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and the American commercial speculator and diplomat Gilbert Iml ...

, Wollstonecraft's child by the American speculator Gilbert Imlay

Gilbert Imlay (February 9, 1754 – November 20, 1828) was an American businessman, author, and diplomat.

He served in the U.S. embassy to France and became one of the earliest American writers, producing two books, the influential ''A Topograph ...

. A year after Wollstonecraft's death, Godwin published his ''Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman'' (1798) is William Godwin's biography of his late wife Mary Wollstonecraft. Rarely published in the nineteenth century and sparingly even today, ''Memoirs'' is most often viewed ...

'' (1798), which he intended as a sincere and compassionate tribute. However, because the ''Memoirs'' revealed Wollstonecraft's affairs and her illegitimate child, they were seen as shocking. Mary Godwin read these memoirs and her mother's books, and was brought up to cherish her mother's memory.

Mary's earliest years were happy, judging from the letters of William Godwin's housekeeper and nurse, Louisa Jones. But Godwin was often deeply in debt; feeling that he could not raise the children by himself, he cast about for a second wife. In December 1801, he married Mary Jane Clairmont, a well-educated woman with two young children of her own—Charles and Claire

Clair or Claire may refer to:

*Claire (given name), a list of people with the name Claire

* Clair (surname)

Places

Canada

* Clair, New Brunswick, a former village, now part of Haut-Madawaska

* Clair Parish, New Brunswick

* Pointe-Claire, Q ...

.Claire's first name was "Jane", but from 1814 (see Gittings and Manton, 22) she preferred to be called "Claire" (her second name was "Clara"), which is how she is known to history. To avoid confusion, this article calls her "Claire" throughout. Most of Godwin's friends disliked his new wife, describing her as quick-tempered and quarrelsome;William St Clair, in his biography of the Godwins and the Shelleys, notes that "it is easy to forget in reading of these crises n the lives of the Godwins and the Shelleyshow unrepresentative the references in surviving documents may be. It is easy for the biographer to give undue weight to the opinions of the people who happen to have written things down." (246) but Godwin was devoted to her, and the marriage was a success. Mary Godwin, on the other hand, came to detest her stepmother.Letter to Percy Shelley, 28 October 1814. ''Selected Letters'', 3; St Clair, 295; Seymour 61. William Godwin's 19th-century biographer Charles Kegan Paul

Charles Kegan Paul (8 March 1828 – 19 July 1902) was an English clergyman, publisher and author. He began his adult life as a clergyman of the Church of England, and served the Church for more than 20 years. His religious orientation moved fr ...

later suggested that Mrs Godwin had favoured her own children over those of Mary Wollstonecraft.St Clair, 295.

Together, the Godwins started a publishing firm called M. J. Godwin, which sold children's books as well as stationery, maps, and games. However, the business did not turn a profit, and Godwin was forced to borrow substantial sums to keep it going. He continued to borrow to pay off earlier loans, compounding his problems. By 1809, Godwin's business was close to failure, and he was "near to despair". Godwin was saved from debtor's prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Histori ...

by philosophical devotees such as Francis Place

Francis Place (3 November 1771 in London – 1 January 1854 in London) was an English social reformer.

Early life

He was an illegitimate son of Simon Place and Mary Gray. His father was originally a journeyman baker. He then became a Marshalse ...

, who lent him further money.

Though Mary Godwin received little formal education, her father tutored her in a broad range of subjects. He often took the children on educational outings, and they had access to his library and to the many intellectuals who visited him, including the

Though Mary Godwin received little formal education, her father tutored her in a broad range of subjects. He often took the children on educational outings, and they had access to his library and to the many intellectuals who visited him, including the Romantic poet

Romantic poetry is the poetry of the Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. It involved a reaction against prevailing Enlightenment ideas of the 18t ...

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poe ...

and the former vice-president of the United States Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

. Godwin admitted he was not educating the children according to Mary Wollstonecraft's philosophy as outlined in works such as ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosop ...

'' (1792), but Mary Godwin nonetheless received an unusual and advanced education for a girl of the time. She had a governess

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, th ...

, a daily tutor, and read many of her father's children's books on Roman and Greek history in manuscript. For six months in 1811, she also attended a boarding school in Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to t ...

. Her father described her at age 15 as "singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind. Her desire of knowledge is great, and her perseverance in everything she undertakes almost invincible."

In June 1812, Mary's father sent her to stay with the dissenting

Dissent is an opinion, philosophy or sentiment of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or policy enforced under the authority of a government, political party or other entity or individual. A dissenting person may be referred to as ...

family of the radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

William Baxter, near Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, Scotland. To Baxter, he wrote, "I am anxious that she should be brought up ... like a philosopher, even like a cynic." Scholars have speculated that she may have been sent away for her health, to remove her from the seamy side of the business, or to introduce her to radical politics. Mary Godwin revelled in the spacious surroundings of Baxter's house and in the companionship of his four daughters, and she returned north in the summer of 1813 for a further stay of 10 months. In the 1831 introduction to ''Frankenstein'', she recalled: "I wrote then—but in a most common-place style. It was beneath the trees of the grounds belonging to our house, or on the bleak sides of the woodless mountains near, that my true compositions, the airy flights of my imagination, were born and fostered."

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Mary Godwin may have first met the radical poet-philosopher

Mary Godwin may have first met the radical poet-philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achie ...

in the interval between her two stays in Scotland. By the time she returned home for a second time on 30 March 1814, Percy Shelley had become estranged from his wife and was regularly visiting William Godwin, whom he had agreed to bail out of debt. Percy Shelley's radicalism, particularly his economic views, which he had imbibed from William Godwin's ''Political Justice

''Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness'' is a 1793 book by the philosopher William Godwin, in which the author outlines his political philosophy. It is the first modern work to expound anarchism.

Backg ...

'' (1793), had alienated him from his wealthy aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word's ...

family: they wanted him to follow traditional models of the landed aristocracy, and he wanted to donate large amounts of the family's money to schemes intended to help the disadvantaged. Percy Shelley, therefore, had difficulty gaining access to money until he inherited his estate because his family did not want him wasting it on projects of "political justice". After several months of promises, Shelley announced that he either could not or would not pay off all of Godwin's debts. Godwin was angry and felt betrayed.

Mary and Percy began meeting each other secretly at her mother Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

's grave in the churchyard of St Pancras Old Church

St Pancras Old Church is a Church of England parish church in Somers Town, Central London. It is dedicated to the Roman martyr Saint Pancras, and is believed by many to be one of the oldest sites of Christian worship in England. The church i ...

, and they fell in love—she was 16, and he was 21. On 26 June 1814, Shelley and Godwin declared their love for one another as Shelley announced he could not hide his "ardent passion", leading her in a "sublime and rapturous moment" to say she felt the same way; on either that day or the next, Godwin lost her virginity to Shelley, which tradition claims happened in the churchyard. Godwin described herself as attracted to Shelley's "wild, intellectual, unearthly looks". To Mary's dismay, her father disapproved, and tried to thwart the relationship and salvage the "spotless fame" of his daughter. At about the same time, Mary's father learned of Shelley's inability to pay off the father's debts. Mary, who later wrote of "my excessive and romantic attachment to my father", was confused. She saw Percy Shelley as an embodiment of her parents' liberal and reformist ideas of the 1790s, particularly Godwin's view that marriage was a repressive monopoly, which he had argued in his 1793 edition of ''Political Justice'' but later retracted. On 28 July 1814, the couple eloped and secretly left for France, taking Mary's stepsister, Claire Clairmont

Clara Mary Jane Clairmont (27 April 1798 – 19 March 1879), or Claire Clairmont as she was commonly known, was the stepsister of the writer Mary Shelley and the mother of Lord Byron's daughter Allegra. She is thought to be the subject of a poe ...

, with them.

After convincing Mary Jane Godwin, who had pursued them to Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

, that they did not wish to return, the trio travelled to Paris, and then, by donkey, mule, carriage, and foot, through a France recently ravaged by war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

, to Switzerland. "It was acting in a novel, being an incarnate romance," Mary Shelley recalled in 1826. Godwin wrote about France in 1814: "The distress of the inhabitants, whose houses had been burned, their cattle killed and all their wealth destroyed, has given a sting to my detestation of war...". As they travelled, Mary and Percy read works by Mary Wollstonecraft and others, kept a joint journal, and continued their own writing. At Lucerne

Lucerne ( , ; High Alemannic German, High Alemannic: ''Lozärn'') or Luzern ()Other languages: gsw, Lozärn, label=Lucerne German; it, Lucerna ; rm, Lucerna . is a city in central Switzerland, in the Languages of Switzerland, German-speaking po ...

, lack of money forced the three to turn back. They travelled down the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

and by land to the Dutch port of Maassluis

Maassluis () is a city in the western Netherlands, in the province of South Holland. The municipality had a population of in and covered of which was water.

It received city rights in 1811.

History

Maassluis was founded circa 1340 as a se ...

, arriving at Gravesend, Kent

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Rochester, it is t ...

, on 13 September 1814.

The situation awaiting Mary Godwin in England was fraught with complications, some of which she had not foreseen. Either before or during the journey, she had become pregnant. She and Percy now found themselves penniless, and, to Mary's genuine surprise, her father refused to have anything to do with her. The couple moved with Claire into lodgings at Somers Town, and later, Nelson Square. They maintained their intense programme of reading and writing, and entertained Percy Shelley's friends, such as

The situation awaiting Mary Godwin in England was fraught with complications, some of which she had not foreseen. Either before or during the journey, she had become pregnant. She and Percy now found themselves penniless, and, to Mary's genuine surprise, her father refused to have anything to do with her. The couple moved with Claire into lodgings at Somers Town, and later, Nelson Square. They maintained their intense programme of reading and writing, and entertained Percy Shelley's friends, such as Thomas Jefferson Hogg

Thomas Jefferson Hogg (24 May 1792 – 27 August 1862) was a British barrister and writer best known for his friendship with the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Hogg was raised in County Durham, but spent most of his life in London. ...

and the writer Thomas Love Peacock

Thomas Love Peacock (18 October 1785 – 23 January 1866) was an English novelist, poet, and official of the East India Company. He was a close friend of Percy Bysshe Shelley and they influenced each other's work. Peacock wrote satirical novels, ...

. Percy Shelley sometimes left home for short periods to dodge creditors. The couple's distraught letters reveal their pain at these separations.

Pregnant and often ill, Mary Godwin had to cope with Percy's joy at the birth of his son by Harriet Shelley in late 1814 and his constant outings with Claire Clairmont."''Journal 6 December''—Very Unwell. Shelley & Clary walk out, as usual, to heaps of places...A letter from Hookham to say that Harriet has been brought to bed of a son and heir. Shelley writes a number of circular letters on this event, which ought to be ushered in with ringing of bells, etc., for it is the son of his ''wife''" (quoted in Spark, 39). Shelley and Clairmont were almost certainly lovers, which caused much jealousy on Godwin's part. Shelley greatly offended Godwin at one point when during a walk in the French countryside he suggested that they both take the plunge into a stream naked as it offended her principles. She was partly consoled by the visits of Hogg, whom she disliked at first but soon considered a close friend. Percy Shelley seems to have wanted Mary Godwin and Hogg to become lovers; Mary did not dismiss the idea, since in principle she believed in free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

. In practice, however, she loved only Percy Shelley and seems to have ventured no further than flirting with Hogg.Sunstein speculates that Mary Shelley and Jefferson Hogg made love in April 1815. (Sunstein, 98–99) On 22 February 1815, she gave birth to a two-month premature baby girl, who was not expected to survive. On 6 March, she wrote to Hogg:

My dearest Hogg my baby is dead—will you come to see me as soon as you can. I wish to see you—It was perfectly well when I went to bed—I awoke in the night to give it suck it appeared to be ''sleeping'' so quietly that I would not awake it. It was dead then, but we did not find ''that'' out till morning—from its appearance it evidently died of convulsions—Will you come—you are so calm a creature & Shelley is afraid of a fever from the milk—for I am no longer a mother now.The loss of her child induced acute depression in Mary Godwin, who was haunted by visions of the baby; but she conceived again and had recovered by the summer. With a revival in Percy Shelley's finances after the death of his grandfather, Sir Bysshe Shelley, the couple holidayed in

Torquay

Torquay ( ) is a seaside town in Devon, England, part of the unitary authority area of Torbay. It lies south of the county town of Exeter and east-north-east of Plymouth, on the north of Tor Bay, adjoining the neighbouring town of Paignton ...

and then rented a two-storey cottage at Bishopsgate, on the edge of Windsor Great Park

Windsor Great Park is a Royal Park of , including a deer park, to the south of the town of Windsor on the border of Berkshire and Surrey in England. It is adjacent to the private Home Park, which is nearer the castle. The park was, for many ...

. Little is known about this period in Mary Godwin's life, since her journal from May 1815 to July 1816 is lost. At Bishopsgate, Percy wrote his poem ''Alastor, or The Spirit of Solitude

''Alastor, or The Spirit of Solitude'' is a poem by Percy Bysshe Shelley, written from 10 September to 14 December in 1815 in Bishopsgate, near Windsor Great Park and first published in 1816. The poem was without a title when Shelley passed it a ...

''; and on 24 January 1816, Mary gave birth to a second child, William, named after her father, and soon nicknamed "Willmouse". In her novel ''The Last Man

''The Last Man'' is an apocalyptic, dystopian science fiction novel by Mary Shelley, first published in 1826. The narrative concerns Europe in the late 21st century, ravaged by a mysterious plague pandemic that rapidly sweeps across the entire ...

'', she later imagined Windsor as a Garden of Eden.

Lake Geneva and ''Frankenstein''

In May 1816, Mary Godwin, Percy Shelley, and their son travelled to

In May 1816, Mary Godwin, Percy Shelley, and their son travelled to Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

with Claire Clairmont. They planned to spend the summer with the poet Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

, whose recent affair with Claire had left her pregnant. In ''History of a Six Weeks’ Tour through a part of France, Switzerland, Germany and Holland (1817)'', she describes the particularly desolate landscape in crossing from France into Switzerland.

The party arrived in Geneva on 14 May 1816, where Mary called herself "Mrs Shelley". Byron joined them on 25 May, with his young physician, John William Polidori

John William Polidori (7 September 1795 – 24 August 1821) was a British writer and physician. He is known for his associations with the Romantic movement and credited by some as the creator of the vampire genre of fantasy

Fantasy is a ...

,Sunstein, 117. and rented the Villa Diodati

The Villa Diodati is a mansion in the village of Cologny near Lake Geneva in Switzerland, notable because Lord Byron rented it and stayed there with John Polidori in the summer of 1816. Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley, who had rented a house ...

, close to Lake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial lak ...

at the village of Cologny

Cologny () is a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in the Canton of Geneva, Switzerland.

History

Cologny is first mentioned in 1208 as ''Colognier''.

The oldest trace of a settlement in the area is a Neolithic lake side village which ...

; Percy Shelley rented a smaller building called Maison Chapuis on the waterfront nearby. They spent their time writing, boating on the lake, and talking late into the night.

"It proved a wet, ungenial summer", Mary Shelley remembered in 1831, "and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house".The violent storms were, it is now known, a repercussion of the volcanic eruption of Mount Tambora

Mount Tambora, or Tomboro, is an active stratovolcano in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Located on Sumbawa in the Lesser Sunda Islands, it was formed by the active subduction zones beneath it. Before 1815, its elevation reached more than ...

in Indonesia the year before (Sunstein, 118). See also The Year Without a Summer. Sitting around a log fire at Byron's villa, the company amused themselves with German ghost stories, which prompted Byron to propose that they "each write a ghost story". Unable to think of a story, young Mary Godwin became anxious: "''Have you thought of a story?'' I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative." During one mid-June evening, the discussions turned to the nature of the principle of life. "Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated", Mary noted; "galvanism

Galvanism is a term invented by the late 18th-century physicist and chemist Alessandro Volta to refer to the generation of electric current by chemical action. The term also came to refer to the discoveries of its namesake, Luigi Galvani, specif ...

had given token of such things". It was after midnight before they retired, and unable to sleep, she became possessed by her imagination as she beheld the ''grim terrors'' of her "waking dream", her ghost story:

She began writing what she assumed would be a short story. With Percy Shelley's encouragement, she expanded this tale into her first novel, ''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'', published in 1818. She later described that summer in Switzerland as the moment "when I first stepped out from childhood into life". The story of the writing of ''Frankenstein'' has been fictionalised several times and formed the basis for a number of films.

In September 2011, the astronomer Donald Olson, after a visit to the Lake Geneva villa the previous year, and inspecting data about the motion of the moon and stars, concluded that her ''waking dream'' took place "between 2am and 3am" 16 June 1816, several days after the initial idea by Lord Byron that they each write a ghost story.Radford, Tim, Frankenstein's hour of creation identified by astronomers

'', ''The Guardian'', 25 September 2011 (retrieved 5 January 2014)

Authorship of ''Frankenstein''

While her husband Percy encouraged her writing, the extent of Percy's contribution to the novel is unknown and has been argued over by readers and critics.Seymour, 195–96. Mary Shelley wrote, "I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband, and yet but for his incitement, it would never have taken the form in which it was presented to the world." She wrote that the preface to the first edition was Percy's work "as far as I can recollect." There are differences in the 1818, 1823 and 1831 editions, which have been attributed to Percy's editing. James Rieger concluded Percy's "assistance at every point in the book's manufacture was so extensive that one hardly knows whether to regard him as editor or minor collaborator", while Anne K. Mellor later argued Percy only "made many technical corrections and several times clarified the narrative and thematic continuity of the text." Charles E. Robinson, editor of a facsimile edition of the ''Frankenstein'' manuscripts, concluded that Percy's contributions to the book "were no more than what most publishers' editors have provided new (or old) authors or, in fact, what colleagues have provided to each other after reading each other's works in progress." Writing on the 200th anniversary of ''Frankenstein'', literary scholar and poetFiona Sampson

Fiona Ruth Sampson, is a British poet and writer. She is published in thirty-seven languages and has received a

number of national and international awards for her writing. A former musician, Sampson has written on the links between music a ...

asked, "Why hasn't Mary Shelley gotten the respect she deserves?" She noted that "In recent years Percy's corrections, visible in the ''Frankenstein'' notebooks held at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, have been seized on as evidence that he must have at least co-authored the novel. In fact, when I examined the notebooks myself, I realized that Percy did rather less than any line editor working in publishing today." Sampson published her findings in ''In Search of Mary Shelley'' (2018), one of many biographies written about Shelley.

Bath and Marlow

On their return to England in September, Mary and Percy moved—with Claire Clairmont, who took lodgings nearby—to Bath, where they hoped to keep Claire's pregnancy secret. At Cologny, Mary Godwin had received two letters from her half-sister,Fanny Imlay

Frances Imlay (14 May 1794 – 9 October 1816), also known as Fanny Godwin and Frances Wollstonecraft, was the illegitimate daughter of the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and the American commercial speculator and diplomat Gilbert Iml ...

, who alluded to her "unhappy life"; on 9 October, Fanny wrote an "alarming letter" from Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

that sent Percy Shelley racing off to search for her, without success. On the morning of 10 October, Fanny Imlay was found dead in a room at a Swansea

Swansea (; cy, Abertawe ) is a coastal city and the second-largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Swansea ( cy, links=no, Dinas a Sir Abertawe).

The city is the twenty-fifth largest in ...

inn, along with a suicide note and a laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum Linnaeus'') in alcohol (ethanol).

Red ...

bottle. On 10 December, Percy Shelley's wife, Harriet, was discovered drowned in the Serpentine, a lake in Hyde Park, London

Hyde Park is a Grade I-listed major park in Westminster, Greater London, the largest of the four Royal Parks that form a chain from the entrance to Kensington Palace through Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, via Hyde Park Corner and Green Pa ...

. Both suicides were hushed up. Harriet's family obstructed Percy Shelley's efforts—fully supported by Mary Godwin—to assume custody of his two children by Harriet. His lawyers advised him to improve his case by marrying; so he and Mary, who was pregnant again, married on 30 December 1816 at St Mildred's Church, Bread Street

Bread Street is one of the 25 wards of the City of London the name deriving from its principal street, which was anciently the City's bread market; already named ''Bredstrate'' (to at least 1180) for by the records it appears as that in 1302, ...

, London. Mr and Mrs Godwin were present and the marriage ended the family rift.

Claire Clairmont gave birth to a baby girl on 13 January, at first called Alba, later Allegra.Alba was renamed "Allegra" in 1818. (Seymour, 177) In March of that year, the Chancery Court ruled Percy Shelley morally unfit to assume custody of his children and later placed them with a clergyman's family. Also in March, the Shelleys moved with Claire and Alba to Albion House at Marlow, Buckinghamshire

Marlow (; historically Great Marlow or Chipping Marlow) is a town and civil parish within the Unitary Authority of Buckinghamshire, England. It is located on the River Thames, south-southwest of High Wycombe, west-northwest of Maidenhead and ...

, a large, damp building on the river Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

. There Mary Shelley gave birth to her third child, Clara, on 2 September. At Marlow, they entertained their new friends Marianne and Leigh Hunt

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 178428 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Hunt co-founded '' The Examiner'', a leading intellectual journal expounding radical principles. He was the centr ...

, worked hard at their writing, and often discussed politics.

Early in the summer of 1817, Mary Shelley finished ''Frankenstein'', which was published anonymously in January 1818. Reviewers and readers assumed that Percy Shelley was the author, since the book was published with his preface and dedicated to his political hero William Godwin. At Marlow, Mary edited the joint journal of the group's 1814 Continental journey, adding material written in Switzerland in 1816, along with Percy's poem "Mont Blanc

Mont Blanc (french: Mont Blanc ; it, Monte Bianco , both meaning "white mountain") is the highest mountain in the Alps and Western Europe, rising above sea level. It is the second-most prominent mountain in Europe, after Mount Elbrus, and i ...

". The result was the ''History of a Six Weeks' Tour'', published in November 1817. That autumn, Percy Shelley often lived away from home in London to evade creditors. The threat of a debtor's prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Histori ...

, combined with their ill health and fears of losing custody of their children, contributed to the couple's decision to leave England for Italy on 12 March 1818, taking Claire Clairmont and Alba with them. They had no intention of returning.

Italy

One of the party's first tasks on arriving in Italy was to hand Alba over to Byron, who was living in

One of the party's first tasks on arriving in Italy was to hand Alba over to Byron, who was living in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. He had agreed to raise her so long as Claire had nothing more to do with her. The Shelleys then embarked on a roving existence, never settling in any one place for long.At various times, the Shelleys lived at Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 158,493 residents in December 2017. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn (pronou ...

, Bagni di Lucca

Bagni di Lucca (formerly Bagno a Corsena) is a comune of Tuscany, Italy, in the Province of Lucca with a population of about 6,100. The comune has 27 named frazioni (wards).

History

Bagni di Lucca has been known for its thermal springs since th ...

, Venice, Este, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Rome, Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

, Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the cit ...

, Bagni di Pisa, and San Terenzo. Along the way, they accumulated a circle of friends and acquaintances who often moved with them. The couple devoted their time to writing, reading, learning, sightseeing, and socialising. The Italian adventure was, however, blighted for Mary Shelley by the deaths of both her children—Clara, in September 1818 in Venice, and William, in June 1819 in Rome.Clara died of dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

at the age of one, and William of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

at three and a half. (Seymour, 214, 231) These losses left her in a deep depression that isolated her from Percy Shelley, who wrote in his notebook:

For a time, Mary Shelley found comfort only in her writing. The birth of her fourth child, Percy Florence, on 12 November 1819, finally lifted her spirits, though she nursed the memory of her lost children till the end of her life.Sunstein, 384–85. Italy provided the Shelleys, Byron, and other exiles with political freedom unattainable at home. Despite its associations with personal loss, Italy became for Mary Shelley "a country which memory painted as paradise". Their Italian years were a time of intense intellectual and creative activity for both Shelleys. While Percy composed a series of major poems, Mary wrote the novel ''My dearest Mary, wherefore hast thou gone, And left me in this dreary world alone? Thy form is here indeed—a lovely one— But thou art fled, gone down a dreary road That leads to Sorrow's most obscure abode. For thine own sake I cannot follow thee Do thou return for mine.

Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1846), British Thoroughbred racehorse

* Matilda, a dog of the professional wrestling tag-team The ...

'', the historical novel '' Valperga'', and the plays '' Proserpine'' and ''Midas

Midas (; grc-gre, Μίδας) was the name of a king in Phrygia with whom several myths became associated, as well as two later members of the Phrygian royal house.

The most famous King Midas is popularly remembered in Greek mythology for his ...

''. Mary wrote ''Valperga'' to help alleviate her father's financial difficulties, as Percy refused to assist him further. She was often physically ill, however, and prone to depressions. She also had to cope with Percy's interest in other women, such as Sophia Stacey

Sophia Stacey (1791– December 11, 1874) was a friend of the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, to whom he dedicated the ''Ode'' which begins:

''Thou art fair, and few are fairer,

''Of the nymphs of earth or ocean,''

''They are robes that fi ...

, Emilia Viviani, and Jane Williams

Jane Williams (''née'' Jane Cleveland; 21 January 1798 – 8 November 1884) was a British woman best known for her association with the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Jane was raised in England and India, before marrying a naval ...

. Since Mary Shelley shared his belief in the non-exclusivity of marriage, she formed emotional ties of her own among the men and women of their circle. She became particularly fond of the Greek revolutionary Prince Alexandros Mavrokordatos and of Jane and Edward Williams.The Williamses were not technically married; Jane was still the wife of an army officer named Johnson.

In December 1818, the Shelleys travelled south with Claire Clairmont and their servants to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, where they stayed for three months, receiving only one visitor, a physician. In 1820, they found themselves plagued by accusations and threats from Paolo and Elise Foggi, former servants whom Percy Shelley had dismissed in Naples shortly after the Foggis had married. The pair revealed that on 27 February 1819 in Naples, Percy Shelley had registered as his child by Mary Shelley a two-month-old baby girl named Elena Adelaide Shelley. The Foggis also claimed that Claire Clairmont was the baby's mother. Biographers have offered various interpretations of these events: that Percy Shelley decided to adopt a local child; that the baby was his by Elise, Claire, or an unknown woman; or that she was Elise's by Byron.Elise had been employed by Byron as Allegra's nurse. Mary Shelley stated in a letter that Elise had been pregnant by Paolo at the time, which was the reason they had married, but not that she had had a child in Naples. Elise seems to have first met Paolo only in September. See Mary Shelley's letter to Isabella Hoppner, 10 August 1821, ''Selected Letters'', 75–79. Mary Shelley insisted she would have known if Claire had been pregnant, but it is unclear how much she really knew. The events in Naples, a city Mary Shelley later called a paradise inhabited by devils,Seymour, 221. remain shrouded in mystery."Establishing Elena Adelaide's parentage is one of the greatest bafflements Shelley left for his biographers." (Bieri, 106) The only certainty is that she herself was not the child's mother. Elena Adelaide Shelley died in Naples on 9 June 1820.

After leaving Naples, the Shelleys settled in Rome, the city where her husband wrote where "the meanest streets were strewed with truncated columns, broken capitals...and sparkling fragments of granite or porphyry...The voice of dead time, in still vibrations, is breathed from these dumb things, animated and glorified as they were by man".Garrett, 55. Rome inspired her to begin writing the unfinished novel ''Valerius, the Reanimated Roman'', where the eponymous hero resists the decay of Rome and the machinations of "superstitious" Catholicism. The writing of her novel was broken off when her son William died of malaria. Shelley bitterly commented that she had come to Italy to improve her husband's health, and instead the Italian climate had just killed her two children, leading her to write: "May you my dear Marianne never know what it is to lose two only and lovely children in one year—to watch their dying moments—and then at last to be left childless and forever miserable". To deal with her grief, Shelley wrote the novella ''The Fields of Fancy'', which became ''Matilda'', dealing with a young woman whose beauty inspired incestuous love in her father, who ultimately commits suicide to stop himself from acting on his passion for his daughter, while she spends the rest of her life full of despair about "the unnatural love I had inspired". The novella offered a feminist critique of a patriarchal society as Matilda is punished in the afterlife, though she did nothing to encourage her father's feelings.

In the summer of 1822, a pregnant Mary moved with Percy, Claire, and Edward and Jane Williams to the isolated Villa Magni, at the sea's edge near the hamlet of San Terenzo in the Bay of Lerici. Once they were settled in, Percy broke the "evil news" to Claire that her daughter Allegra had died of

In the summer of 1822, a pregnant Mary moved with Percy, Claire, and Edward and Jane Williams to the isolated Villa Magni, at the sea's edge near the hamlet of San Terenzo in the Bay of Lerici. Once they were settled in, Percy broke the "evil news" to Claire that her daughter Allegra had died of typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

in a convent at Bagnacavallo

Bagnacavallo ( rgn, Bagnacavàl) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Ravenna, Emilia-Romagna, Italy.

The Renaissance painter Bartolomeo Ramenghi bore the nickname of his native city.

Main sights

*''Castellaccio'' (15th century)

* Gia ...

. Mary Shelley was distracted and unhappy in the cramped and remote Villa Magni, which she came to regard as a dungeon. On 16 June, she miscarried

Miscarriage, also known in medical terms as a spontaneous abortion and pregnancy loss, is the death of an embryo or fetus before it is able to survive independently. Miscarriage before 6 weeks of gestation is defined by ESHRE as biochemical lo ...

, losing so much blood that she nearly died. Rather than wait for a doctor, Percy sat her in a bath of ice to stanch the bleeding, an act the doctor later told him saved her life. All was not well between the couple that summer, however, and Percy spent more time with Jane Williams than with his depressed and debilitated wife. Much of the short poetry Shelley wrote at San Terenzo involved Jane rather than Mary.

The coast offered Percy Shelley and Edward Williams the chance to enjoy their "perfect plaything for the summer", a new sailing boat. The boat had been designed by Daniel Roberts and Edward Trelawny, an admirer of Byron's who had joined the party in January 1822. On 1 July 1822, Percy Shelley, Edward Ellerker Williams

Edward Ellerker Williams (22 April 1793 – 8 July 1822) was a retired army officer who became a friend of Percy Bysshe Shelley in the final months of his life and died with him.

Early life

Edward Williams was born in India, the son of an East ...

, and Captain Daniel Roberts sailed south down the coast to Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 158,493 residents in December 2017. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn (pronou ...

. There Percy Shelley discussed with Byron and Leigh Hunt the launch of a radical magazine called ''The Liberal

''The Liberal'' was a London-based magazine "dedicated to promoting liberalism around the world", which ran in print from 2004 to 2009 and online until 2012. The publication explored liberal attitudes to a range of cultural issues, and encouraged ...

''. On 8 July, he and Edward Williams set out on the return journey to Lerici with their eighteen-year-old boat boy, Charles Vivian. They never reached their destination. A letter arrived at Villa Magni from Hunt to Percy Shelley, dated 8 July, saying, "pray write to tell us how you got home, for they say you had bad weather after you sailed Monday & we are anxious".Letter to Maria Gisborne, 15 August 1815, ''Selected Letters'', 99. "The paper fell from me," Mary told a friend later. "I trembled all over." She and Jane Williams rushed desperately to Livorno and then to Pisa in the fading hope that their husbands were still alive. Ten days after the storm, three bodies washed up on the coast near Viareggio

Viareggio () is a city and ''comune'' in northern Tuscany, Italy, on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea. With a population of over 62,000, it is the second largest city within the province of Lucca, after Lucca.

It is known as a seaside resort as ...

, midway between Livorno and Lerici. Trelawny, Byron, and Hunt cremated

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre i ...

Percy Shelley's corpse on the beach at Viareggio.

Return to England and writing career

After her husband's death, Mary Shelley lived for a year with Leigh Hunt and his family inGenoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

, where she often saw Byron and transcribed his poems. She resolved to live by her pen and for her son, but her financial situation was precarious. On 23 July 1823, she left Genoa for England and stayed with her father and stepmother in the Strand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street ...

until a small advance from her father-in-law enabled her to lodge nearby. Sir Timothy Shelley had at first agreed to support his grandson, Percy Florence, only if he were handed over to an appointed guardian. Mary Shelley rejected this idea instantly. She managed instead to wring out of Sir Timothy a limited annual allowance (which she had to repay when Percy Florence inherited the estate), but to the end of his days, he refused to meet her in person and dealt with her only through lawyers. Mary Shelley busied herself with editing her husband's poems, among other literary endeavours, but concern for her son restricted her options. Sir Timothy threatened to stop the allowance if any biography of the poet were published. In 1826, Percy Florence became the legal heir of the Shelley estate after the death of his half-brother Charles Shelley, his father's son by Harriet Shelley. Sir Timothy raised Mary's allowance from £100 a year to £250 but remained as difficult as ever. Mary Shelley enjoyed the stimulating society of William Godwin's circle, but poverty prevented her from socialising as she wished. She also felt ostracised by those who, like Sir Timothy, still disapproved of her relationship with Percy Bysshe Shelley.

In the summer of 1824, Mary Shelley moved to Kentish Town

Kentish Town is an area of northwest London, England in the London Borough of Camden, immediately north of Camden Town. Less than four miles north of central London, Kentish Town has good transport connections and is situated close to the ope ...

in north London to be near Jane Williams. She may have been, in the words of her biographer Muriel Spark

Dame Muriel Sarah Spark (née Camberg; 1 February 1918 – 13 April 2006). was a Scottish novelist, short story writer, poet and essayist.

Life

Muriel Camberg was born in the Bruntsfield area of Edinburgh, the daughter of Bernard Camberg, an ...

, "a little in love" with Jane. Jane later disillusioned her by gossiping that Percy had preferred her to Mary, owing to Mary's inadequacy as a wife. At around this time, Mary Shelley was working on her novel, ''The Last Man

''The Last Man'' is an apocalyptic, dystopian science fiction novel by Mary Shelley, first published in 1826. The narrative concerns Europe in the late 21st century, ravaged by a mysterious plague pandemic that rapidly sweeps across the entire ...

'' (1826); and she assisted a series of friends who were writing memoirs of Byron and Percy Shelley—the beginnings of her attempts to immortalise her husband. She also met the American actor John Howard Payne

John Howard Payne (June 9, 1791 – April 10, 1852) was an American actor, poet, playwright, and author who had nearly two decades of a theatrical career and success in London. He is today most remembered as the creator of "Home! Sweet Home ...

and the American writer Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

, who intrigued her. Payne fell in love with her and in 1826 asked her to marry him. She refused, saying that after being married to one genius, she could only marry another. Payne accepted the rejection and tried without success to talk his friend Irving into proposing himself. Mary Shelley was aware of Payne's plan, but how seriously she took it is unclear.

In 1827, Mary Shelley was party to a scheme that enabled her friend Isabel Robinson and Isabel's lover, Mary Diana Dods

Mary Diana Dods (1790–1830) was a Scottish writer of books, stories and other works who adopted a male identity. Most of her works appeared under the pseudonym David Lyndsay. In private life she used the name Walter Sholto Douglas. This may hav ...

, who wrote under the name David Lyndsay, to embark on a life together in France as husband and wife.Dods, who had an infant daughter, assumed the name Walter Sholto Douglas and was accepted in France as a man. With the help of Payne, whom she kept in the dark about the details, Mary Shelley obtained false passports for the couple. In 1828, she fell ill with smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

while visiting them in Paris. Weeks later she recovered, unscarred but without her youthful beauty.

During the period 1827–40, Mary Shelley was busy as an editor and writer. She wrote the novels '' The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck'' (1830), ''Lodore

''Lodore'', also published under the title ''The Beautiful Widow'', is the penultimate novel by Romantic novelist Mary Shelley, completed in 1833 and published in 1835.

Plot and themes

In ''Lodore'', Shelley focused her theme of power and resp ...

'' (1835), and '' Falkner'' (1837). She contributed five volumes of ''Lives

Lives may refer to:

* The plural form of a '' life''

* Lives, Iran, a village in Khuzestan Province, Iran

* The number of lives in a video game

* '' Parallel Lives'', aka ''Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans'', a series of biographies of famous ...

'' of Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and French authors to Lardner's '' Cabinet Cyclopaedia''. She also wrote stories for ladies' magazines. She was still helping to support her father, and they looked out for publishers for each other. In 1830, she sold the copyright for a new edition of ''Frankenstein'' for £60 to Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley for their new Standard Novels series. After her father's death in 1836 at the age of eighty, she began assembling his letters and a memoir for publication, as he had requested in his will; but after two years of work, she abandoned the project. Throughout this period, she also championed Percy Shelley's poetry, promoting its publication and quoting it in her writing. By 1837, Percy's works were well-known and increasingly admired. In the summer of 1838 Edward Moxon

Edward Moxon (12 December 1801 – 3 June 1858) was a British poet and publisher, significant in Victorian literature.

Biography

Moxon was born at Wakefield in Yorkshire, where his father Michael worked in the wool trade. In 1817 he left ...

, the publisher of Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

and the son-in-law of Charles Lamb

Charles Lamb (10 February 1775 – 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, poet, and antiquarian, best known for his ''Essays of Elia'' and for the children's book ''Tales from Shakespeare'', co-authored with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764–18 ...

, proposed publishing a collected works of Percy Shelley. Mary was paid £500 to edit the ''Poetical Works'' (1838), which Sir Timothy insisted should not include a biography. Mary found a way to tell the story of Percy's life, nonetheless: she included extensive biographical notes about the poems.

Shelley continued to practice her mother's feminist principles by extending aid to women whom society disapproved of.Garrett, 98. For instance, Shelley extended financial aid to Mary Diana Dods, a single mother and illegitimate herself who appears to have been a lesbian and gave her the new identity of Walter Sholto Douglas, husband of her lover Isabel Robinson. Shelley also assisted Georgiana Paul, a woman disallowed for by her husband for alleged adultery.Garrett, 99. Shelley in her diary about her assistance to the latter: "I do not make a boast-I do not say aloud-behold my generosity and greatness of mind-for in truth it is simple justice I perform-and so I am still reviled for being worldly".

Mary Shelley continued to treat potential romantic partners with caution. In 1828, she met and flirted with the French writer Prosper Mérimée

Prosper Mérimée (; 28 September 1803 – 23 September 1870) was a French writer in the movement of Romanticism, and one of the pioneers of the novella, a short novel or long short story. He was also a noted archaeologist and historian, and a ...

, but her one surviving letter to him appears to be a deflection of his declaration of love. She was delighted when her old friend from Italy, Edward Trelawny, returned to England, and they joked about marriage in their letters. Their friendship had altered, however, following her refusal to cooperate with his proposed biography of Percy Shelley; and he later reacted angrily to her omission of the atheistic section of ''Queen Mab

Queen Mab is a fairy referred to in William Shakespeare's play ''Romeo and Juliet'', where "she is the fairies' midwife". Later, she appears in other poetry and literature, and in various guises in drama and cinema. In the play, her activity i ...

'' from Percy Shelley's poems. Oblique references in her journals, from the early 1830s until the early 1840s, suggest that Mary Shelley had feelings for the radical politician Aubrey Beauclerk, who may have disappointed her by twice marrying others.Beauclerk married Ida Goring in 1838 and, after Ida's death, Mary Shelley's friend Rosa Robinson in 1841. A clear picture of Mary Shelley's relationship with Beauclerk is difficult to reconstruct from the evidence. (Seymour, 425–26)

Mary Shelley's first concern during these years was the welfare of Percy Florence. She honoured her late husband's wish that his son attend public school

Public school may refer to:

* State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

* Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England an ...

and, with Sir Timothy's grudging help, had him educated at Harrow. To avoid boarding fees, she moved to Harrow on the Hill

Harrow on the Hill is a locality and historic village in the borough of Harrow in Greater London, England. The name refers to Harrow Hill, ,Mills, A., ''Dictionary of London Place Names'', (2001) and is located some half a mile south of the mod ...

herself so that Percy could attend as a day scholar. Though Percy went on to Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

, and dabbled in politics and the law, he showed no sign of his parents' gifts. He was devoted to his mother, and after he left university in 1841, he came to live with her.

Final years and death

In 1840 and 1842, mother and son travelled together on the continent, journeys that Mary Shelley recorded in '' Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843'' (1844). In 1844, Sir Timothy Shelley finally died at the age of ninety, "falling from the stalk like an overblown flower", as Mary put it. For the first time, she and her son were financially independent, though the estate proved less valuable than they had hoped. In the mid-1840s, Mary Shelley found herself the target of three separate blackmailers. In 1845, an Italian political exile called Gatteschi, whom she had met in Paris, threatened to publish letters she had sent him. A friend of her son's bribed a police chief into seizing Gatteschi's papers, including the letters, which were then destroyed. Shortly afterwards, Mary Shelley bought some letters written by herself and Percy Bysshe Shelley from a man calling himself G. Byron and posing as the illegitimate son of the late

In the mid-1840s, Mary Shelley found herself the target of three separate blackmailers. In 1845, an Italian political exile called Gatteschi, whom she had met in Paris, threatened to publish letters she had sent him. A friend of her son's bribed a police chief into seizing Gatteschi's papers, including the letters, which were then destroyed. Shortly afterwards, Mary Shelley bought some letters written by herself and Percy Bysshe Shelley from a man calling himself G. Byron and posing as the illegitimate son of the late Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

. Also in 1845, Percy Bysshe Shelley's cousin Thomas Medwin

Thomas Medwin (20 March 1788 –2 August 1869) was an early 19th-century English writer, poet and translator. He is known chiefly for his biography of his cousin, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and for published recollections of his friend, Lord Byron.

...

approached her claiming to have written a damaging biography of Percy Shelley. He said he would suppress it in return for £250, but Mary Shelley refused.According to Bieri, Medwin claimed to possess evidence relating to Naples. Medwin is the source for the theory that the child registered by Percy Shelley in Naples was his daughter by a mystery woman. See also, ''Journals'', 249–50 ''n''3.

In 1848, Percy Florence married Jane Gibson St John. The marriage proved a happy one, and Mary Shelley and Jane were fond of each other. Mary lived with her son and daughter-in-law at Field Place, Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

, the Shelleys' ancestral home, and at Chester Square

Chester Square is an elongated residential garden square in London's Belgravia district. It was developed by the Grosvenor family, as were the nearby Belgrave and Eaton Square. The square is named after the city of Chester, the city nearest t ...

, London, and accompanied them on travels abroad.

Mary Shelley's last years were blighted by illness. From 1839, she suffered from headaches and bouts of paralysis in parts of her body, which sometimes prevented her from reading and writing. On 1 February 1851, at Chester Square, she died at the age of fifty-three from what her physician suspected was a brain tumour. According to Jane Shelley, Mary Shelley had asked to be buried with her mother and father; but Percy and Jane, judging the graveyard at St Pancras to be "dreadful", chose to bury her instead at St Peter's Church, Bournemouth, near their new home at Boscombe

Boscombe is a suburb of Bournemouth, England. Historically in Hampshire, but today in Dorset, it is located to the east of Bournemouth town centre and west of Southbourne.

Originally a sparsely inhabited area of heathland, from around 1865 B ...

. On the first anniversary of Mary Shelley's death, the Shelleys opened her box-desk. Inside they found locks of her dead children's hair, a notebook she had shared with Percy Bysshe Shelley, and a copy of his poem ''Adonaïs

''Adonais: An Elegy on the Death of John Keats, Author of Endymion, Hyperion, etc.'' () is a pastoral elegy written by Percy Bysshe Shelley for John Keats in 1821, and widely regarded as one of Shelley's best and best-known works.

' s multiple narratives enable Shelley to split her artistic persona: she can "express and efface herself at the same time". Shelley's fear of self-assertion is reflected in the fate of Frankenstein, who is punished for his egotism by losing all his domestic ties.

Feminist critics often focus on how authorship itself, particularly female authorship, is represented in and through Shelley's novels. As Mellor explains, Shelley uses the

Mary Shelley believed in the Enlightenment idea that people could improve society through the responsible exercise of political power, but she feared that the irresponsible exercise of power would lead to chaos. In practice, her works largely criticise the way 18th-century thinkers such as her parents believed such change could be brought about. The creature in ''Frankenstein'', for example, reads books associated with radical ideals but the education he gains from them is ultimately useless. Shelley's works reveal her as less optimistic than Godwin and Wollstonecraft; she lacks faith in Godwin's theory that humanity could eventually be perfected.

As literary scholar Kari Lokke writes, ''The Last Man'', more so than ''Frankenstein'', "in its refusal to place humanity at the centre of the universe, its questioning of our privileged position in relation to nature ... constitutes a profound and prophetic challenge to Western humanism." Specifically, Mary Shelley's allusions to what radicals believed was a failed revolution in France and the Godwinian, Wollstonecraftian, and Burkean responses to it, challenge "Enlightenment faith in the inevitability of progress through collective efforts". As in ''Frankenstein'', Shelley "offers a profoundly disenchanted commentary on the age of revolution, which ends in a total rejection of the progressive ideals of her own generation". Not only does she reject these Enlightenment political ideals, but she also rejects the Romantic notion that the poetic or literary imagination can offer an alternative.