Marwan ibn al-Hakam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marwan ibn al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As ibn Umayya ( ar, links=no, مروان بن الحكم بن أبي العاص بن أمية, Marwān ibn al-Ḥakam ibn Abī al-ʿĀṣ ibn Umayya), commonly known as MarwanI (623 or 626April/May 685), was the fourth Umayyad caliph, ruling for less than a year in 684–685. He founded the Marwanid ruling house of the

Marwan was born in 2 or 4 AH (623 or 626 CE). His father was al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As of the

Marwan was born in 2 or 4 AH (623 or 626 CE). His father was al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As of the

Ali was assassinated by a member of the

Ali was assassinated by a member of the

In opposition to the Kalb, the pro-Zubayrid

In opposition to the Kalb, the pro-Zubayrid

Umayyad dynasty

Umayyad dynasty ( ar, بَنُو أُمَيَّةَ, Banū Umayya, Sons of Umayya) or Umayyads ( ar, الأمويون, al-Umawiyyūn) were the ruling family of the Caliphate between 661 and 750 and later of Al-Andalus between 756 and 1031. In the ...

, which replaced the Sufyanid house after its collapse in the Second Muslim Civil War

The Second Fitna was a period of general political and military disorder and civil war in the Islamic community during the early Umayyad Caliphate., meaning trial or temptation) occurs in the Qur'an in the sense of test of faith of the believer ...

and remained in power until 750.

During the reign of his cousin Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic proph ...

(), Marwan took part in a military campaign

A military campaign is large-scale long-duration significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of interrelated military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war. The term derives from the p ...

against the Byzantines of the Exarchate of Africa

The Exarchate of Africa was a division of the Byzantine Empire around Carthage that encompassed its possessions on the Western Mediterranean. Ruled by an exarch (viceroy), it was established by the Emperor Maurice in the late 580s and survive ...

(in central North Africa), where he acquired significant war spoils. He also served as Uthman's governor in Fars (southwestern Iran) before becoming the caliph's ''katib

A katib ( ar, كَاتِب, ''kātib'') is a writer, scribe, or secretary in the List of countries where Arabic is an official language, Arabic-speaking world, Persian people, Persian World, and other Islamic areas as far as India. In North Africa ...

'' (secretary or scribe). He was wounded fighting the rebel siege of Uthman's house, in which the caliph was slain. In the ensuing civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policie ...

between Ali

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam. ...

() and the largely Qurayshite partisans of A'isha, Marwan sided with the latter at the Battle of the Camel

The Battle of the Camel, also known as the Battle of Jamel or the Battle of Basra, took place outside of Basra, Iraq, in 36 AH (656 CE). The battle was fought between the army of the fourth caliph Ali, on one side, and the rebel army led by ...

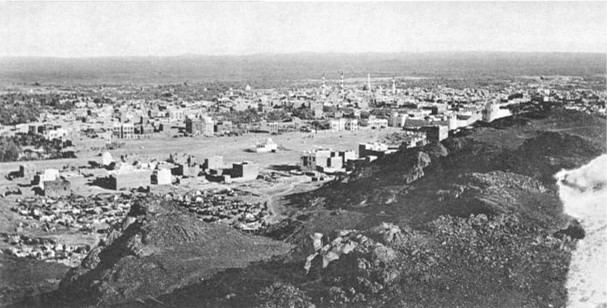

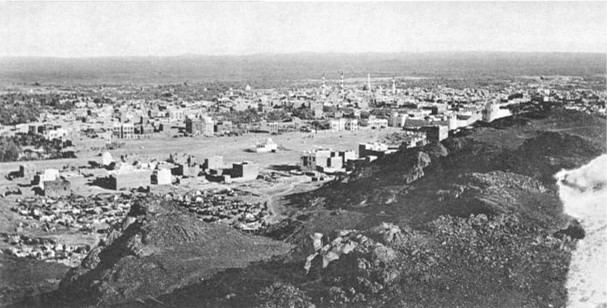

. Marwan later served as governor of Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

under his distant kinsman Caliph Mu'awiya I

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

(), founder of the Umayyad Caliphate. During the reign of Mu'awiya's son and successor Yazid I

Yazid ibn Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan ( ar, يزيد بن معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiya ibn ʾAbī Sufyān; 64611 November 683), commonly known as Yazid I, was the second caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate. He ruled from ...

(), Marwan organized the defense of the Umayyad realm in the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

(western Arabia) against the local opposition. After Yazid died in November 683, the Mecca-based rebel Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr

Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam ( ar, عبد الله ابن الزبير ابن العوام, ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-ʿAwwām; May 624 CE – October/November 692), was the leader of a caliphate based in Mecca that rivaled the ...

declared himself caliph and expelled Marwan, who took refuge in Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, the center of Umayyad rule. With the death of the last Sufyanid caliph Mu'awiya II in 684, Marwan, encouraged by the ex-governor of Iraq Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad

ʿUbayd Allāh ibn Ziyād ( ar, عبيد الله بن زياد, ʿUbayd Allāh ibn Ziyād) was the Umayyad governor of Basra, Kufa and Khurasan during the reigns of caliphs Mu'awiya I and Yazid I, and the leading general of the Umayyad army unde ...

, volunteered his candidacy for the caliphate during a summit of pro-Umayyad tribes in Jabiya

Jabiyah ( ar, الجابية / ALA-LC: ''al-Jābiya'') was a town of political and military significance in the 6th–8th centuries. It was located between the Hawran plain and the Golan Heights. It initially served as the capital of the Ghassanids ...

. The tribal nobility, led by Ibn Bahdal

Hassan ibn Malik ibn Bahdal al-Kalbi ( ar, حسان بن مالك بن بحدل الكلبي, Ḥassān ibn Mālik ibn Baḥdal al-Kalbī, commonly known as Ibn Bahdal ( ar, ابن بحدل, Ibn Baḥdal; d. 688/89), was the Umayyad governor of Pa ...

of the Banu Kalb

The Banu Kalb ( ar, بنو كلب) was an Arab tribe which mainly dwelt in the desert between northwestern Arabia and central Syria. The Kalb was involved in the tribal politics of the eastern frontiers of the Byzantine Empire, possibly as early ...

, elected Marwan and together they defeated the pro-Zubayrid Qays

Qays ʿAylān ( ar, قيس عيلان), often referred to simply as Qays (''Kais'' or ''Ḳays'') were an Arab tribal confederation that branched from the Mudar group. The tribe does not appear to have functioned as a unit in the pre-Islamic er ...

tribes at the Battle of Marj Rahit in August of that year.

In the months that followed, Marwan reasserted Umayyad rule over Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East J ...

, and northern Syria, whose governors had defected to Ibn al-Zubayr's cause, while keeping the Qays in check in the Jazira

Jazira or Al-Jazira ( 'island'), or variants, may refer to:

Business

*Jazeera Airways, an airlines company based in Kuwait

Locations

* Al-Jazira, a traditional region known today as Upper Mesopotamia or the smaller region of Cizre

* Al-Jazira (c ...

(Upper Mesopotamia). He dispatched an expedition led by Ibn Ziyad to reconquer Zubayrid Iraq, but died while it was underway in the spring of 685. Before his death, Marwan firmly established his sons in positions of power: Abd al-Malik

Abdul Malik ( ar, عبد الملك) is an Arabic (Muslim or Christian) male given name and, in modern usage, surname. It is built from the Arabic words '' Abd'', ''al-'' and ''Malik''. The name means "servant of the King", in the Christian instan ...

was designated his successor, Abd al-Aziz was made governor of Egypt, and Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

oversaw military command in Upper Mesopotamia. Although Marwan was stigmatized as an outlaw and a father of tyrants in later anti-Umayyad tradition, the historian Clifford E. Bosworth asserts that the caliph was a shrewd, capable, and decisive military leader and statesman who laid the foundations of continued Umayyad rule for a further sixty-five years.

Early life and family

Marwan was born in 2 or 4 AH (623 or 626 CE). His father was al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As of the

Marwan was born in 2 or 4 AH (623 or 626 CE). His father was al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As of the Banu Umayya

Umayyad dynasty ( ar, بَنُو أُمَيَّةَ, Banū Umayya, Sons of Umayya) or Umayyads ( ar, الأمويون, al-Umawiyyūn) were the ruling family of the Caliphate between 661 and 750 and later of Al-Andalus between 756 and 1031. In the ...

(Umayyads), the strongest clan of the Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Qur ...

, a polytheistic tribe which dominated the town of Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valle ...

in the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

. The Quraysh converted to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

en masse in following the conquest of Mecca

The Conquest of Mecca ( ar, فتح مكة , translit=Fatḥ Makkah) was the capture of the town of Mecca by Muslims led by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in December 629 or January 630 AD ( Julian), 10–20 Ramadan, 8 AH. The conquest marked t ...

by the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

, himself a member of the Quraysh. Marwan knew Muhammad and is thus counted among the latter's ''sahaba

The Companions of the Prophet ( ar, اَلصَّحَابَةُ; ''aṣ-ṣaḥāba'' meaning "the companions", from the verb meaning "accompany", "keep company with", "associate with") were the disciples and followers of Muhammad who saw or m ...

'' (companions). Marwan's mother was Amina bint Alqama of the Kinana

The Kinana ( ar, كِنَاَنَة, Kināna) were an Arab tribe based around Mecca in the Tihama coastal area and the Hejaz mountains. The Quraysh of Mecca, the tribe of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, was an offshoot of the Kinana. A number of mod ...

, the ancestral tribe of the Quraysh which dominated the area stretching southwest from Mecca to the Tihama

Tihamah or Tihama ( ar, تِهَامَةُ ') refers to the Red Sea coastal plain of the Arabian Peninsula from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb.

Etymology

Tihāmat is the Proto-Semitic language's term for ' sea'. Tiamat (or Tehom, in ma ...

coastline.

Marwan had at least sixteen children, among them at least twelve sons from five wives and an ''umm walad

An ''umm walad'' ( ar, أم ولد, , lit=mother of the child) was the title given to a slave-concubine in the Muslim world after she had born her master a child. She could not be sold, and became automatically free on her master's death. The off ...

'' (concubine). From his wife A'isha, a daughter of his paternal first cousin Mu'awiya ibn al-Mughira

Muʿāwiya ibn al-Mughīra ibn Abī al-ʿĀs ibn Umayya () was a member of the Banu Umayya alleged to be a spy against the Muslims during the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He was captured during the Invasion of Hamra al-Asad, where Muhamma ...

, he had his eldest son Abd al-Malik

Abdul Malik ( ar, عبد الملك) is an Arabic (Muslim or Christian) male given name and, in modern usage, surname. It is built from the Arabic words '' Abd'', ''al-'' and ''Malik''. The name means "servant of the King", in the Christian instan ...

, Mu'awiya and daughter Umm Amr. Umm Amr later married Sa'id ibn Khalid ibn Amr, a great-grandson of Marwan's paternal first cousin Uthman ibn Affan

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic proph ...

, who became caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

(leader of the Muslim community) in 644. Marwan's wife Layla bint Zabban ibn al-Asbagh of the Banu Kalb

The Banu Kalb ( ar, بنو كلب) was an Arab tribe which mainly dwelt in the desert between northwestern Arabia and central Syria. The Kalb was involved in the tribal politics of the eastern frontiers of the Byzantine Empire, possibly as early ...

tribe bore him Abd al-Aziz and daughter Umm Uthman, who was married to Caliph Uthman's son al-Walid; al-Walid was also married at one point to Marwan's daughter Umm Amr. Another of Marwan's wives, Qutayya bint Bishr of the Banu Kilab

The Banu Kilab ( ar, بنو كِلاب, Banū Kilāb) was an Arab tribe in the western Najd (central Arabia) where they controlled the horse-breeding pastures of Dariyya from the mid-6th century until at least the mid-9th century. The tribe was div ...

, bore him Bishr and Abd al-Rahman, the latter of whom died young. One of Marwan's wives, Umm Aban al-Kubra, was a daughter of Caliph Uthman. She was mother to six of his sons, Aban

Apas (, ae, āpas) is the Avestan language term for "the waters", which, in its innumerable aggregate states, is represented by the Apas, the hypostases of the waters.

''Āb'' (plural ''Ābān'') is the Middle Persian-language form.

Introduc ...

, Uthman, Ubayd Allah, Ayyub, Dawud and Abd Allah, though the last of them died a child. Marwan was married to Zaynab bint Umar, a granddaughter of Abu Salama

Abū Salamah ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-Asad ( ar, أَبُو سَلَمَة عَبْد ٱلله ٱبْن عَبْد ٱلْأَسَد ) was one of the Companians of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He was also a cousin and a foster-brother of Muhamm ...

from the Banu Makhzum

The Banu Makhzum () was one of the wealthy clans of the Quraysh. They are regarded as being among the three most powerful and influential clans in Mecca before the advent of Islam, the other two being the Banu Hashim (the tribe of the Islamic proph ...

, who mothered his son Umar. Marwan's ''umm walad'' was also named Zaynab and gave birth to his son Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

. Marwan had ten brothers and was the paternal uncle of ten nephews.

Secretary of Uthman

During the reign of Caliph Uthman (), Marwan took part in amilitary campaign

A military campaign is large-scale long-duration significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of interrelated military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war. The term derives from the p ...

against the Byzantines of the Exarchate of Carthage

The Exarchate of Africa was a division of the Byzantine Empire around Carthage that encompassed its possessions on the Western Mediterranean. Ruled by an exarch (viceroy), it was established by the Emperor Maurice in the late 580s and survive ...

(in central North Africa), where he acquired significant war spoils. These likely formed the basis of Marwan's substantial wealth, part of which he invested in properties in Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

, the capital of the Caliphate. At an undetermined point, he served as Uthman's governor in Fars (southwestern Iran) before becoming the caliph's ''katib

A katib ( ar, كَاتِب, ''kātib'') is a writer, scribe, or secretary in the List of countries where Arabic is an official language, Arabic-speaking world, Persian people, Persian World, and other Islamic areas as far as India. In North Africa ...

'' (secretary or scribe) and possibly the overseer of Medina's treasury. According to the historian Clifford E. Bosworth, in this capacity Marwan "doubtless helped" in the revision "of what became the canonical text of the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

" in Uthman's reign.

The historian Hugh N. Kennedy

Hugh Nigel Kennedy (born 22 October 1947) is a British medieval historian and academic. He specialises in the history of the early Islamic Middle East, Muslim Iberia and the Crusades. From 1997 to 2007, he was Professor of Middle Eastern Histo ...

asserts that Marwan was the caliph's "right-hand man". According to the traditional Muslim reports, many of Uthman's erstwhile backers among the Quraysh gradually withdrew their support as a result of Marwan's pervasive influence, which they blamed for the caliph's controversial decisions. The historian Fred Donner

Fred McGraw Donner (born 1945) is a scholar of Islam and Peter B. Ritzma Professor of Near Eastern History at the University of Chicago.

questions the veracity of these reports, citing the unlikelihood that Uthman would be highly influenced by a younger relative such as Marwan and the rarity of specific charges against the latter, and describes them as a possible "attempt by later Islamic tradition to salvage Uthman's reputation as one of the so-called 'rightly-guided' ('' rāshidūn'') caliphs by making Marwan... the fall guy for the unhappy events at the end of Uthman's twelve-year reign."

Discontent over Uthman's nepotistic

Nepotism is an advantage, privilege, or position that is granted to relatives and friends in an occupation or field. These fields may include but are not limited to, business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, fitness, religion, an ...

policies and confiscation of the former Sasanian

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

crown lands in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

drove the Quraysh and the dispossessed elites of Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

to oppose the caliph. In early 656, rebels from Egypt and Kufa entered Medina to press Uthman to reverse his policies. Marwan recommended a violent response against them. Instead, Uthman entered into a settlement with the Egyptians, the largest and most outspoken group among the mutineers. On their return to Egypt, the rebels intercepted a letter in Uthman's name to Egypt's governor, Ibn Abi Sarh, instructing him to take action against the rebels. In reaction, the Egyptians marched back to Medina and besieged Uthman in his home in June 656. Uthman claimed to have been unaware of the letter, and it may have been authored by Marwan without Uthman's knowledge. Despite orders to the contrary, Marwan actively defended Uthman's house and was badly wounded in the neck when he challenged the rebels assembled at its entrance. According to tradition, he was saved by the intervention of his wet nurse, Fatima bint Aws, and was transported to the safety of her home by his '' mawla'' (freedman or client), Abu Hafs al-Yamani. Shortly after, Uthman was assassinated by the rebels, which became one of the major contributing factors to the First Muslim Civil War

The First Fitna ( ar, فتنة مقتل عثمان, fitnat maqtal ʻUthmān, strife/sedition of the killing of Uthman) was the first civil war in the Islamic community. It led to the overthrow of the Rashidun Caliphate and the establishment of ...

. After the assassination, Marwan and other Umayyads fled to Mecca. Calls for avenging Uthman's death were led by the Umayyads, one of Muhammad's wives, A'isha, and two of his prominent companions, Talha ibn Ubayd Allah

Ṭalḥa ibn ʿUbayd Allāh al-Taymī ( ar, طَلْحَة بن عُبَيْد اللّه التَّيمي, ) was a Companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. In Sunni Islam, he is mostly known for being among ('the ten to whom Paradise was ...

and Zubayr ibn al-Awwam

Az Zubayr ( ar, الزبير) is a city in and the capital of Al-Zubair District, part of the Basra Governorate of Iraq. The city is just south of Basra. The name can also refer to the old Emirate of Zubair.

The name is also sometimes written A ...

. Punishing Uthman's murderers became a rallying cry of the opposition to his successor, Ali ibn Abi Talib

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam. ...

, a cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad.

Role in the First Fitna

In the ensuing hostilities between Ali and the largely Qurayshite partisans of A'isha, Marwan sided with the latter. He fought alongside A'isha's forces at theBattle of the Camel

The Battle of the Camel, also known as the Battle of Jamel or the Battle of Basra, took place outside of Basra, Iraq, in 36 AH (656 CE). The battle was fought between the army of the fourth caliph Ali, on one side, and the rebel army led by ...

near Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is hand ...

in December 656. The historian Leone Caetani

Leone Caetani (September 12, 1869 – December 25, 1935), Duke of Sermoneta (also known as Prince Caetani), was an Italian scholar, politician, and historian of the Middle East.

Caetani is considered a pioneer in the application of the historic ...

presumed that Marwan was the organizer of A'isha's strategy there. The modern historian Laura Veccia Vaglieri

Laura Veccia Vaglieri (1893 – 1989) was an Italian orientalist.

A scholar and one of the pioneers of Arabic and Islamic studies in Italy, Veccia Vaglieri served as professor at the Università degli Studi di Napoli "L'Orientale" and was the a ...

notes that while Caetani's "theory is attractive", there is no information in the traditional sources to confirm it and should Marwan have been A'isha's war adviser "he operated so discreetly that the sources hardly speak of his actions."

According to one version in the Islamic tradition, Marwan used the occasion of the battle to kill a partisan of A'isha, Talha, whom he held especially responsible for instigating Uthman's death. Marwan had fired an arrow at Talha, which struck the sciatic vein below his knee, as their troops fell back in a hand-to-hand fight with Ali's soldiers. The historian Wilferd Madelung

Wilferd Ferdinand Madelung FBA (b. December 26, 1930 in Stuttgart) is a German-British author and scholar of Islamic history.

Life

After World War II, the adolescent Wilferd accompanied his parents to the USA where his father Georg Hans Mad ...

notes that Marwan "evidently" waited to kill Talha when A'isha appeared close to defeat and thus in a weak position to call Marwan to account for his action. Another version in the tradition attributes Talha's death to Ali's supporters during Talha's retreat from the field, and Caetani dismisses Marwan's culpability as a fabrication by the generally anti-Umayyad sources. Madelung holds that Marwan's slaying of Talha is corroborated by Umayyad propaganda in the 680s heralding him as the first person to take revenge for Uthman's death by killing Talha.

After the battle ended with Ali's victory, Marwan pledged him allegiance. Ali pardoned him and Marwan left for Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, where his distant cousin Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

, who refused allegiance to Ali, was governor. Marwan was present alongside Mu'awiya at the Battle of Siffin

The Battle of Siffin was fought in 657 CE (37 AH) between Ali ibn Abi Talib, the fourth of the Rashidun Caliphs and the first Shia Imam, and Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, the rebellious governor of Syria. The battle is named after its location S ...

near Raqqa

Raqqa ( ar, ٱلرَّقَّة, ar-Raqqah, also and ) ( Kurdish: Reqa/ ڕەقە) is a city in Syria on the northeast bank of the Euphrates River, about east of Aleppo. It is located east of the Tabqa Dam, Syria's largest dam. The Hellenistic, R ...

in 657, which ended in a stalemate with Ali's army and abortive arbitration talks to settle the civil war.

Governor of Medina

Ali was assassinated by a member of the

Ali was assassinated by a member of the Kharijite

The Kharijites (, singular ), also called al-Shurat (), were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the ...

s, a sect opposed to both Ali and Mu'awiya, in January 661. His son and successor Hasan ibn Ali

Hasan ibn Ali ( ar, الحسن بن علي, translit=Al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī; ) was a prominent early Islamic figure. He was the eldest son of Ali and Fatima and a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He briefly ruled as caliph from Jan ...

abdicated in a peace treaty with Mu'awiya, who entered Hasan's and formerly Ali's capital at Kufa and gained recognition as caliph there in July or September, marking the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

. Marwan served as Mu'awiya's governor in Bahrayn

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ad ...

(eastern Arabia) before serving two stints as governor of Medina in 661–668 and 674–677. In between those two terms, Marwan's Umayyad kinsmen Sa'id ibn al-As and al-Walid ibn Utba ibn Abi Sufyan

Al-Walīd ibn ʿUtba ibn Abī Sufyān () (died 684) was an Umayyad ruling family member and statesman during the reigns of the Umayyad caliphs Mu'awiya I () and Yazid I (). He served two stints as the governor of Medina in 677/78–680 and 681– ...

held the post. Medina had lost its status as the political center of the Caliphate in the aftermath of Uthman's assassination, and under Mu'awiya the capital shifted to Damascus. Although it was reduced to a provincial governorship, Medina remained a hub of Arab culture and Islamic scholarship and home of the traditional Islamic aristocracy. The old elites in Medina, including most of the Umayyad family, resented their loss of power to Mu'awiya; in the summation of the historian Julius Wellhausen

Julius Wellhausen (17 May 1844 – 7 January 1918) was a German biblical scholar and orientalist. In the course of his career, he moved from Old Testament research through Islamic studies to New Testament scholarship. Wellhausen contributed to ...

, "of what consequence was Marwan, formerly the all-powerful imperial chancellor of Uthman, now as Emir of Medina! No wonder he cast envious looks at his cousin of Damascus who had so far outstripped him."

During his first term, Marwan acquired from Mu'awiya a large estate in the Fadak

Fadak ( ar, فدك) was a village with fertile land in an oasis near Medina. The takeover of Fadak by Muslims in 629 CE was peaceful and a share of it thus belonged to the Islamic prophet Muhammad. After Muhammad died in 632, Fadak was confisc ...

oasis in northwestern Arabia, which he then bestowed on his sons Abd al-Malik and Abd al-Aziz. Marwan's first dismissal from the governorship caused him to travel to Mu'awiya's court for an explanation from the caliph, who listed three reasons: Marwan's refusal to confiscate for Mu'awiya the properties of their relative Abd Allah ibn Amir

Abū ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿĀmir ibn Kurayz ( ar, أبو عبد الرحمن عبد الله بن عامر بن كريز) (626–678) was a Rashidun politician and general, serving as governor of Basra from 647 to 656 AD during t ...

after the latter's dismissal from the governorship of Basra; Marwan's criticism of the caliph's adoption of the fatherless Ziyad ibn Abihi

Abu al-Mughira Ziyad ibn Abihi ( ar, أبو المغيرة زياد بن أبيه, Abū al-Mughīra Ziyād ibn Abīhi; – 673), also known as Ziyad ibn Abi Sufyan ( ar, زياد بن أبي سفيان, Ziyād ibn Abī Sufyān), was an adminis ...

, Ibn Amir's successor in Basra, as the son of his father Abu Sufyan

Sakhr ibn Harb ibn Umayya ibn Abd Shams ( ar, صخر بن حرب بن أمية بن عبد شمس, Ṣakhr ibn Ḥarb ibn Umayya ibn ʿAbd Shams; ), better known by his '' kunya'' Abu Sufyan ( ar, أبو سفيان, Abū Sufyān), was a prominent ...

, which the Umayyad family disputed; and Marwan's refusal to assist the caliph's daughter Ramla in a domestic dispute with her husband, Amr ibn Uthman ibn Affan. In 670, Marwan led Umayyad opposition to the attempted burial of Hasan ibn Ali beside the grave of Muhammad, compelling Hasan's brother, Husayn

Hussein, Hussain, Hossein, Hossain, Huseyn, Husayn, Husein or Husain (; ar, حُسَيْن ), coming from the triconsonantal root Ḥ-S-i-N ( ar, ح س ی ن, link=no), is an Arabic name which is the diminutive of Hassan, meaning "good", " ...

, and his clan, the Banu Hashim

)

, type = Qurayshi Arab clan

, image =

, alt =

, caption =

, nisba = al-Hashimi

, location = Mecca, Hejaz Middle East, North Africa, Horn of Africa

, descended = Hashim ibn Abd Manaf

, parent_tribe = Qura ...

, to abandon their original funeral arrangement and bury Hasan in the Baqi cemetery instead. Afterward, Marwan participated in the funeral and eulogized Hasan as one "whose forbearance weighed mountains".

According to Bosworth, Mu'awiya may have been suspicious of the ambitions of Marwan and the Abu al-As line of the Banu Umayya in general, which was significantly more numerous than the Abu Sufyan (Sufyanid) line to which Mu'awiya belonged. Marwan was among the eldest and most prestigious Umayyads at a time when there were few experienced Sufyanids of mature age. Bosworth speculates that it "may have been fears of the family of Abu'l-ʿĀs that impelled Muʿāwiya to his adoption of his putative half-brother Ziyād b. Sumayya iyad ibn Abihi Iyad may refer to:

*Iyad (tribe), Arab tribe, 3rd–7th centuries

*Iyad Jamal Al-Din (born 1961), prominent Iraqi intellectual, politician and religious cleric

*Iyad Al-Khatib, Jordanian football player

*Abdallah Iyad Barghouti (born 1979), Palestin ...

and to the unusual step of naming his own son Yazīd as heir to the caliphate during his own lifetime". Marwan had earlier pressed Uthman's son Amr to claim the caliphate based on the legitimacy of his father, a member of the Abu al-As branch, but Amr was uninterested. Marwan reluctantly accepted Mu'awiya's nomination of Yazid in 676, but quietly encouraged another son of Uthman, Sa'id, to contest the succession. Sa'id's ambitions were neutralized when the caliph gave him military command in Khurasan

Greater Khorāsān,Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236 or Khorāsān ( pal, Xwarāsān; fa, خراسان ), is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plate ...

, the easternmost region of the Caliphate.

Leader of the Umayyads in Medina

After Mu'awiya died in 680, Husayn ibn Ali,Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr

Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam ( ar, عبد الله ابن الزبير ابن العوام, ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-ʿAwwām; May 624 CE – October/November 692), was the leader of a caliphate based in Mecca that rivaled the ...

and Abd Allah ibn Umar, all sons of prominent Qurayshite companions of Muhammad with their own claims to the caliphate, continued to refuse allegiance to Mu'awiya's chosen successor Yazid. Marwan, the leader of the Umayyad clan in the Hejaz, advised al-Walid ibn Utba, then governor of Medina, to coerce Husayn and Ibn al-Zubayr, both of whom he considered especially dangerous to Umayyad rule, to accept the caliph's sovereignty. Husayn answered al-Walid's summons, but withheld his recognition of Yazid, offering instead to make the pledge in public. Al-Walid accepted, prompting Marwan, who attended the meeting, to castigate the governor and demand Husayn's detention until he proffered the oath of allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to a monarch or a country. In modern republics, oaths are sworn to the country in general, or to the country's constitution. For ...

to Yazid or his execution should he refuse. Husayn then cursed Marwan and left the meeting, eventually making his way toward Kufa to lead a rebellion against the Umayyads. He was slain by Yazid's forces at the Battle of Karbala in October 680.

Meanwhile, Ibn al-Zubayr avoided al-Walid's summons and escaped to Mecca, where he rallied opposition to Yazid from his headquarters in the Ka'aba

The Kaaba (, ), also spelled Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah ( ar, ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, lit=Honored Ka'bah, links=no, translit=al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah), is a building at the c ...

, Islam's holiest sanctuary where violence was traditionally banned. In the Islamic traditional anecdotes relating Yazid's response, Marwan warns Ibn al-Zubayr not to submit to the caliph; Wellhausen considers these variable traditions to be unreliable. In 683, the people of Medina rebelled against the caliph and assaulted the local Umayyads and their supporters, prompting them to take refuge in Marwan's houses in the city's suburbs where they were besieged. In response to Marwan's plea for assistance, Yazid dispatched an expeditionary force of Syrian tribesmen led by Muslim ibn Uqba

Muslim ibn ʿUqba al-Murrī () (pre-622–683) was a general of the Umayyad Caliphate during the reigns of caliphs Mu'awiya I ( 661–680) and his son and successor Yazid I ( 680–683). The latter assigned Muslim, a staunch loyalist who had disti ...

to assert Umayyad authority over the region. The Umayyads of Medina were afterward expelled and many, including Marwan and the Abu al-As family, joined Ibn Uqba's expedition. In the ensuing Battle of al-Harra

The Battle of al-Harra ( ar, يوم الحرة, Yawm al-Ḥarra ) was fought between the Syrian army of the Umayyad caliph Yazid I () led by Muslim ibn Uqba and the defenders of Medina from the Ansar and Muhajirun factions, who had rebelled a ...

in August 683, Marwan led his horsemen through Medina and launched a rear assault against the Medinese defenders fighting Ibn Uqba in the city's eastern outskirts. Despite its victory over the Medinese, Yazid's army retreated to Syria in the wake of the caliph's death in November. On the Syrians' departure, Ibn al-Zubayr declared himself caliph and soon gained recognition in most of the Caliphate's provinces, including Egypt, Iraq and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and sha ...

. Marwan and the Umayyads of the Hejaz were expelled for a second time by Ibn al-Zubayr's partisans and their properties were confiscated.

Caliphate

Accession

By early 684, Marwan was in Syria, either atPalmyra

Palmyra (; Palmyrene: () ''Tadmor''; ar, تَدْمُر ''Tadmur'') is an ancient city in present-day Homs Governorate, Syria. Archaeological finds date back to the Neolithic period, and documents first mention the city in the early second ...

or in the court of Yazid's young son and successor, Mu'awiya II, in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

. The latter died several weeks into his reign without designating a successor. The governors of the Syrian ''jund

Under the early Caliphates, a ''jund'' ( ar, جند; plural ''ajnad'', اجناد) was a military division, which became applied to Arab military colonies in the conquered lands and, most notably, to the provinces into which Greater Syria (the Le ...

s'' (military districts) of Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East J ...

, Homs

Homs ( , , , ; ar, حِمْص / ALA-LC: ; Levantine Arabic: / ''Ḥomṣ'' ), known in pre-Islamic Syria as Emesa ( ; grc, Ἔμεσα, Émesa), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level ...

and Qinnasrin

Qinnasrin ( ar, قنسرين; syr, ܩܢܫܪܝܢ, ''Qinnašrīn'', lit=Nest of Eagles), also known by numerous other romanizations and originally known as ( la, Chalcis ad Belum; grc-gre, Χαλκὶς, ''Khalkìs''), was a historical town in ...

subsequently gave their allegiance to Ibn al-Zubayr. As a result, Marwan "despaired over any future for the Umayyads as rulers", according to Bosworth, and was prepared to recognize Ibn al-Zubayr's legitimacy. However, he was encouraged by the expelled governor of Iraq, Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad

ʿUbayd Allāh ibn Ziyād ( ar, عبيد الله بن زياد, ʿUbayd Allāh ibn Ziyād) was the Umayyad governor of Basra, Kufa and Khurasan during the reigns of caliphs Mu'awiya I and Yazid I, and the leading general of the Umayyad army unde ...

, to volunteer himself as Mu'awiyaII's successor during a summit of loyalist Syrian Arab tribes being held in Jabiya

Jabiyah ( ar, الجابية / ALA-LC: ''al-Jābiya'') was a town of political and military significance in the 6th–8th centuries. It was located between the Hawran plain and the Golan Heights. It initially served as the capital of the Ghassanids ...

. The bids for leadership of the Muslim community exposed the conflict between three developing principles of succession. The general recognition of Ibn al-Zubayr adhered to the Islamic principle of passing leadership to the most righteous and eminent Muslim, while the Umayyad loyalists at the Jabiya summit debated the two other principles: direct hereditary succession as introduced by Mu'awiyaI and represented by the nomination of his adolescent grandson Khalid ibn Yazid

Khālid ibn Yazīd (full name ''Abū Hāshim Khālid ibn Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān'', ), 668–704 or 709, was an Umayyad prince and purported alchemist.

As a son of the Umayyad caliph Yazid I, Khalid was supposed to become cal ...

; and the Arab tribal norm of selecting the wisest and most capable member of a tribe's leading clan, epitomized in this case by Marwan.

The organizer of the Jabiya summit, Ibn Bahdal

Hassan ibn Malik ibn Bahdal al-Kalbi ( ar, حسان بن مالك بن بحدل الكلبي, Ḥassān ibn Mālik ibn Baḥdal al-Kalbī, commonly known as Ibn Bahdal ( ar, ابن بحدل, Ibn Baḥdal; d. 688/89), was the Umayyad governor of Pa ...

, the chieftain of the powerful Banu Kalb tribe and maternal cousin of Yazid, supported Khalid's nomination. Most of the other chieftains, led by Rawh ibn Zinba of the Judham

The Judham ( ar, بنو جذام, ') was an Arab tribe that inhabited the southern Levant and northwestern Arabia during the Byzantine and early Islamic eras (5th–8th centuries). Under the Byzantines, the tribe was nominally Christian and foug ...

and Husayn ibn Numayr

Al-Ḥuṣayn ibn Numayr al-Sakūnī (died 5/6 August 686) was a leading general of the early Umayyad Caliphate, from the Sakun subtribe of the Kinda.Lammens & Cremonesi (1971), pp. 620–621

Biography

A man of his name is recorded as being r ...

of the Kinda, opted for Marwan, citing his mature age, political acumen and military experience, over Khalid's youth and inexperience. The 9th-century historian al-Ya'qubi quotes Rawh heralding Marwan: "People of Syria! This is Marwān b. al-Ḥakam, the chief of Quraysh, who avenged the blood of ʿUthmān and fought ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib at the Battle of the Camel and Ṣiffīn." A consensus was ultimately reached on 22 June 684 (29 Shawwal

Shawwal ( ar, شَوَّال, ') is the tenth month of the lunar based Islamic calendar. ''Shawwāl'' stems from the verb ''shāla'' () which means to 'lift or carry', generally to take or move things from one place to another,

Fasting during S ...

64 AH), whereby Marwan would accede to the caliphate, followed by Khalid and then Amr ibn Sa'id ibn al-As, another prominent young Umayyad. In exchange for backing Marwan, the loyalist Syrian tribes, who shortly thereafter became known as the "Yaman" faction ( see below), were promised financial compensation. The Yamani ''ashraf

Sharīf ( ar, شريف, 'noble', 'highborn'), also spelled shareef or sherif, feminine sharīfa (), plural ashrāf (), shurafāʾ (), or (in the Maghreb) shurfāʾ, is a title used to designate a person descended, or claiming to be descended, fr ...

'' (tribal nobility) demanded from Marwan the same courtly and military privileges they held under the previous Umayyad caliphs. Husayn ibn Numayr had attempted to reach a similar arrangement with Ibn al-Zubayr, who publicly rejected the terms. In contrast, Marwan "realized the importance of the Syrian troops and adhered wholeheartedly to their demands", according to the historian Mohammad Rihan. In the summation of Kennedy, "Marwān had no experience or contacts in Syria; he would be entirely dependent on the ''ashrāf'' from the Yamanī tribes who had elected him."

Campaigns to reassert Umayyad rule

Qays

Qays ʿAylān ( ar, قيس عيلان), often referred to simply as Qays (''Kais'' or ''Ḳays'') were an Arab tribal confederation that branched from the Mudar group. The tribe does not appear to have functioned as a unit in the pre-Islamic er ...

i tribes objected to Marwan's accession and beckoned al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Fihri

Abū Unays (or Abū ʿAbd al-Raḥmān) al-Ḍaḥḥak ibn Qays al-Fihrī () (died August 684) was an Umayyad general, head of security forces and governor of Damascus during the reigns of caliphs Mu'awiya I, Yazid I and Mu'awiya II. Though long ...

, the governor of Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, to mobilize for war; accordingly, al-Dahhak and the Qays set up camp in the Marj Rahit plain north of Damascus. Most of the Syrian ''junds'' backed Ibn al-Zubayr, with the exception of Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

, whose dominant tribe was the Kalb. With the critical support of the Kalb and its allied tribes, Marwan marched against al-Dahhak's larger army, while in Damascus city, a Ghassanid

The Ghassanids ( ar, الغساسنة, translit=al-Ġasāsina, also Banu Ghassān (, romanized as: ), also called the Jafnids, were an Arab tribe which founded a kingdom. They emigrated from southern Arabia in the early 3rd century to the Levan ...

nobleman expelled al-Dahhak's partisans and brought the city under Marwan's authority. In August, Marwan's forces routed the Qays and killed al-Dahhak at the Battle of Marj Rahit. Marwan's rise had affirmed the power of the Quda'a

The Quda'a ( ar, قضاعة, translit=Quḍāʿa) were a confederation of Arab tribes, including the powerful Kalb and Tanukh, mainly concentrated throughout Syria and northwestern Arabia, from at least the 4th century CE, during Byzantine rule, ...

tribal confederation, of which the Kalb was part, and after the battle, it formed an alliance with the Qahtan

The terms Qahtanite and Qahtani ( ar, قَحْطَانِي; transliterated: Qaḥṭānī) refer to Arabs who originate from South Arabia. The term "Qahtan" is mentioned in multiple ancient Arabian inscriptions found in Yemen. Arab traditions be ...

confederation of Homs, forming the new super-tribe of Yaman. The crushing Umayyad–Yamani victory at Marj Rahit led to the long-running Qays–Yaman blood feud. The remnants of Qays rallied around Zufar ibn al-Harith al-Kilabi

Abu al-Hudhayl Zufar ibn al-Harith al-Kilabi ( ar, أبو الهذيل زفر بن الحارث الكلابي, Abū al-Hudhayl Zufar ibn al-Ḥārith al-Kilābī; died ) was a Muslim commander, a chieftain of the Arab tribe of Banu Amir, and t ...

, who took over the fortress of Qarqisiya (Circesium) in Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia is the name used for the uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the region has been ...

, from which he led the tribal opposition to the Umayyads. In a poem attributed to him, Marwan thanked the Yamani tribes for their support at Marj Rahit:

When I saw that the affair would be one of plunder, I made ready Ghassan and Kalb against them he QaysAnd the Saksakīs indites men who would triumph, and Ṭayyi', who would insist on the striking of blows,And the Qayn who would come weighed down with arms, and of Tanūkh a difficult and lofty peak.Although he was already recognized by the loyalist tribes at Jabiya, Marwan received ceremonial oaths of allegiance as caliph in Damascus in July or August. He wed Yazid's widow and mother of Khalid, Umm Hashim Fakhita, thereby establishing a political link with the Sufyanids. Wellhausen viewed the marriage as an attempt by Marwan to seize the inheritance of Yazid by becoming stepfather to his sons. Marwan appointed the Ghassanid Yahya ibn Qays as the head of his ''he enemy He or HE may refer to: Language * He (pronoun), an English pronoun * He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ * He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets * He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...will not seize the kingship unless by force, and if Qays approach, say, Keep away!

shurta

''Shurṭa'' ( ar, شرطة) is the common Arabic term for police, although its precise meaning is that of a "picked" or elite force. Bodies termed ''shurṭa'' were established in the early days of the Caliphate, perhaps as early as the caliphate ...

'' (security forces) and his own ''mawla'' Abu Sahl al-Aswad as his ''hajib

A ''hajib'' or ''hadjib'' ( ar, الحاجب, al-ḥājib, to block, the prevent someone from entering somewhere; It is a word "hajb" meaning to cover, to hide. It means "the person who prevents a person from entering a place, the doorman". The ...

'' (chamberlain).

Despite his victory at Marj Rahit and the consolidation of Umayyad power in central Syria, Marwan's authority was not recognized in the rest of the Umayyads' former domains; with the help of Ibn Ziyad and Ibn Bahdal, Marwan undertook to restore Umayyad rule across the Caliphate with "energy and determination", according to Kennedy. To Palestine he dispatched Rawh ibn Zinba, who forced the flight to Mecca of his rival for leadership of the Judham tribe, the pro-Zubayrid governor Natil ibn Qays. Marwan also consolidated Umayyad rule in northern Syria, and the remainder of his reign was marked by attempts to reassert Umayyad authority. By February/March 685, he secured his rule in Egypt with key assistance from the Arab tribal nobility of the provincial capital Fustat

Fusṭāṭ ( ar, الفُسطاط ''al-Fusṭāṭ''), also Al-Fusṭāṭ and Fosṭāṭ, was the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, and the historical centre of modern Cairo. It was built adjacent to what is now known as Old Cairo by ...

. The province's pro-Zubayrid governor, Abd al-Rahman ibn Utba al-Fihri

Abd al-Rahman ibn Utba al-Fihri, also known as Ibn Jahdam, was the governor of Egypt for the rival caliph Ibn al-Zubayr in 684, during the Second Fitna.

Egypt's Kharijites proclaimed themselves for Ibn al-Zubayr when he proclaimed himself Cali ...

, was expelled and replaced with Marwan's son Abd al-Aziz. Afterward, Marwan's forces led by Amr ibn Sa'id repelled a Zubayrid expedition against Palestine launched by Ibn al-Zubayr's brother Mus'ab. Marwan dispatched an expedition to the Hejaz led by the Quda'a commander Hubaysh ibn Dulja, which was routed at al-Rabadha east of Medina. Meanwhile, Marwan sent his son Muhammad to check the Qaysi tribes in the middle Euphrates region. By early 685, he dispatched an army led by Ibn Ziyad to conquer Iraq from the Zubayrids and the pro-Alid

The Alids are those who claim descent from the '' rāshidūn'' caliph and Imam ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (656–661)—cousin, son-in-law, and companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad—through all his wives. The main branches are the (inclu ...

s (partisans of Caliph Ali and his household and the forerunners of the Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, most n ...

sect of Islam).

Death and succession

After a reign of between six and ten months, depending on the source, Marwan died in the spring of 65 AH/685. The precise date of his death is not clear from the medieval sources, with historiansIbn Sa'd

Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Sa‘d ibn Manī‘ al-Baṣrī al-Hāshimī or simply Ibn Sa'd ( ar, ابن سعد) and nicknamed ''Scribe of Waqidi'' (''Katib al-Waqidi''), was a scholar and Arabian biographer. Ibn Sa'd was born in 784/785 C ...

, al-Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari i ...

and Khalifa ibn Khayyat

Abū ʿAmr Khalīfa ibn Khayyāṭ al-Laythī al-ʿUṣfurī () (born : 160/161 AH/777 AD– died 239/240 AH/854 AD) was an Arab historian.

His family were natives of Basra in Iraq. His grandfather was a noted muhaddith or traditionalist, and Kh ...

placing it on 29Sha'ban

Shaʽban ( ar, شَعْبَان, ') is the eighth month of the Islamic calendar. It is called as the month of "separation", as the word means "to disperse" or "to separate" because the pagan Arabs used to disperse in search of water.

The fiftee ...

/10 or 11 April, al-Mas'udi

Al-Mas'udi ( ar, أَبُو ٱلْحَسَن عَلِيّ ٱبْن ٱلْحُسَيْن ٱبْن عَلِيّ ٱلْمَسْعُودِيّ, '; –956) was an Arab historian, geographer and traveler. He is sometimes referred to as the "Herodotu ...

on 3Ramadan

, type = islam

, longtype = Religious

, image = Ramadan montage.jpg

, caption=From top, left to right: A crescent moon over Sarıçam, Turkey, marking the beginning of the Islamic month of Ramadan. Ramadan Quran reading in Bandar Torkaman, Iran. C ...

/13 April and Elijah of Nisibis

, native_name_lang = Syriac

, church = Church of the East

, archdiocese = Nisibis

, province = Metropolitanate of Nisibis

, metropolis =

, diocese =

, see =

, appointed = 26 Dec ...

on 7May. Most early Muslim sources hold that Marwan died in Damascus, while al-Mas'udi holds that he died at his winter residence in al-Sinnabra near Lake Tiberias

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest f ...

. Although it is widely reported in the traditional Muslim sources that Marwan was killed in his sleep by Umm Hashim Fakhita in retaliation for a serious verbal insult to her honor by the caliph, most western historians dismiss the story. Based on a report by al-Mas'udi, Bosworth and others suspect Marwan succumbed to a plague afflicting Syria at the time of his death.

Upon Marwan's return to Syria from Egypt in 685, he had designated his sons Abd al-Malik and Abd al-Aziz as his successors, in that order. He made the change after he reached al-Sinnabra and was informed that Ibn Bahdal recognized Amr ibn Sa'id as Marwan's successor-in-waiting. He summoned and questioned Ibn Bahdal and ultimately demanded that he give allegiance to Abd al-Malik as his heir apparent. By this, Marwan abrogated the arrangement reached at the Jabiya summit in 684, re-instituting the principle of direct hereditary succession. Abd al-Malik acceded to the caliphate without opposition from the previously designated successors, Khalid ibn Yazid and Amr ibn Sa'id. Thereafter, hereditary succession became the standard practice of the Umayyad caliphs.

Assessment

By making his family the foundation of his power, Marwan modeled his administration on that of Caliph Uthman, who extensively relied on his kinsmen, as opposed to Mu'awiyaI, who largely kept them at arm's length. To that end, Marwan ensured Abd al-Malik's succession as caliph and gave his sons Muhammad and Abd al-Aziz key military commands. Despite the tumultuous beginnings, the "Marwanids" (descendants of Marwan) were established as the ruling house of the Umayyad realm. In the view of Bosworth, Marwan "was obviously a military leader and statesman of great skill and decisiveness amply endowed with the qualities of ''ḥilm'' evelheadednessand shrewdness, which characterised other outstanding members of the Umayyad clan". His rise as caliph in Syria, a largely unfamiliar territory where he lacked a power-base, laid the foundations for Abd al-Malik's reign, which consolidated Umayyad rule for a further sixty-five years. In the view of Madelung, Marwan's path to the caliphate was "truly high politics", the culmination of intrigues dating from his early career. These included encouraging Uthman's empowerment of the Umayyads, becoming the "first avenger" of Uthman's assassination by murdering Talha, and privately undermining while publicly enforcing the authority of the Sufyanid caliphs of Damascus. Marwan was known to be gruff and lacking in social graces. He suffered permanent injuries after a number of battle wounds. His tall and emaciated appearance lent him the nickname ''khayt batil'' (gossamer-like thread). In later anti-Umayyad Muslim tradition, Marwan was derided as ''tarid ibn tarid'' (outlawed son of an outlaw) in reference to his father al-Hakam's alleged exile toTa'if

Taif ( ar, , translit=aṭ-Ṭāʾif, lit=The circulated or encircled, ) is a city and governorate in the Makkan Region of Saudi Arabia. Located at an elevation of in the slopes of the Hijaz Mountains, which themselves are part of the Sarat M ...

by the Islamic prophet Muhammad and Marwan's expulsion from Medina by Ibn al-Zubayr. He was also referred to as ''abu al-jababira'' (father of tyrants) because his son and grandsons later inherited the caliphal throne. In a number of sayings attributed to Muhammad, Marwan and his father are the subject of the Islamic prophet's foreboding, though Donner holds that much of these reports were likely conceived by Shia opponents of Marwan and the Umayyads in general.

A number of reports cited by the medieval Islamic historians al-Baladhuri

ʾAḥmad ibn Yaḥyā ibn Jābir al-Balādhurī ( ar, أحمد بن يحيى بن جابر البلاذري) was a 9th-century Muslim historian. One of the eminent Middle Eastern historians of his age, he spent most of his life in Baghdad and e ...

(d. 892) and Ibn Asakir

Ibn Asakir ( ar-at, ابن عساكر, Ibn ‘Asākir; 1105–c. 1176) was a Syrian Sunni Islamic scholar, who was one of the most renowned experts on Hadith and Islamic history in the medieval era. and a disciple of the Sufi mystic Abu al-Najib ...

(d. 1176) are indicative of Marwan's piety, such as the 9th-century historian al-Mada'ini

Abū l-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbdallāh ibn Abī Sayf al-Qurashī l-Madāʾinī () (752/3–843), better known by his ''nisba'' of al-Madāʾinī ("from al-Mada'in"), was a scholar of Iranian descent who wrote in Arabic and was active ...

's assertion that Marwan was among the best readers of the Qur'an and Marwan's own claim to have recited the Qur'an for over forty years before the Battle of Marj Rahit. On the basis that many of his sons bore clearly Islamic names (as opposed to traditional Arabian names), Donner speculates Marwan may have indeed been "deeply religious" and "profoundly impressed" by the Qur'anic message to honor God and the prophets of Islam

Prophets in Islam ( ar, الأنبياء في الإسلام, translit=al-ʾAnbiyāʾ fī al-ʾIslām) are individuals in Islam who are believed to spread God's message on Earth and to serve as models of ideal human behaviour. Some prophets a ...

, including Muhammad. Donner notes the difficulty of "achieving a sound assessment of Marwan", as with most Islamic leaders of his generation, due to an absence of archaeological and epigraphic

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

documentation and the restriction of his biographical information to often polemical literary sources.

See also

* Al-Harith ibn al-Hakam, brother of Marwan I *Yahya ibn al-Hakam

Yaḥyā ibn al-Ḥakam ibn Abī al-ʿĀṣ () (died before 700) was an Umayyad statesman during the caliphate of his nephew, Abd al-Malik (). He fought against Caliph Ali () at the Battle of the Camel and later moved to Damascus where he was a ...

, brother of Marwan I

* Aban ibn al-Walid ibn Uqba

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Marwan 01 620s births 685 deaths Year of birth uncertain 7th-century Umayyad caliphs 7th-century rulers in Asia 7th-century rulers in Africa 7th-century Arabs Hadith narrators People of the Second Fitna Umayyad governors of Medina Rashidun governors of Bahrain