Martinus W. Beijerinck on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

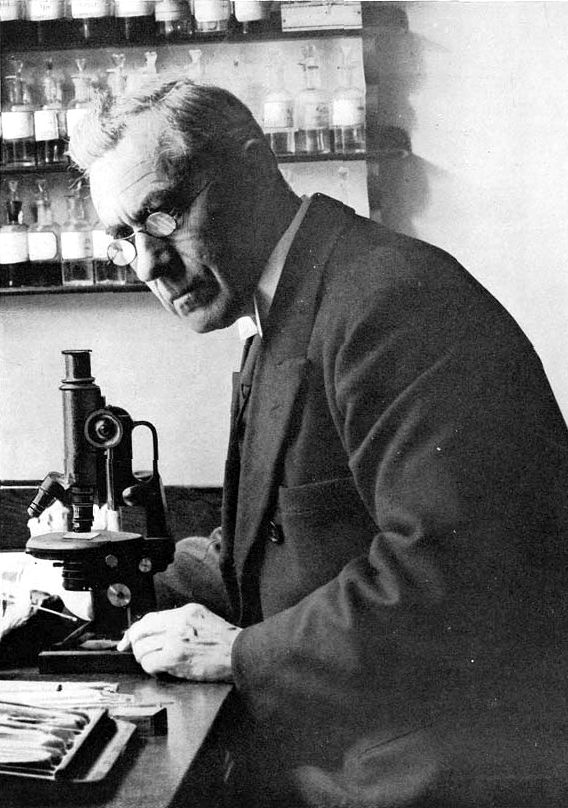

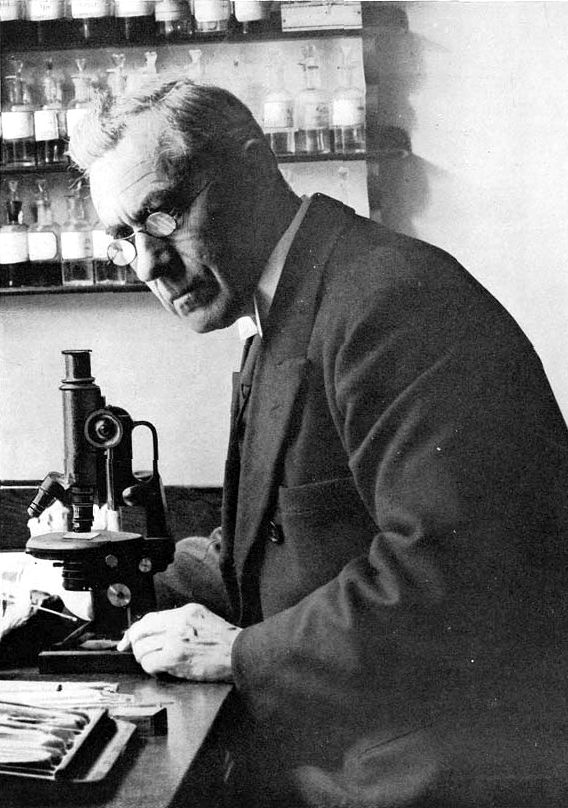

Martinus Willem Beijerinck (, 16 March 1851 – 1 January 1931) was a Dutch microbiologist and botanist who was one of the founders of

He is considered one of the founders of

He is considered one of the founders of

Beijerinck and the Delft School of Microbiology

{{DEFAULTSORT:Beijerinck, Martinus 1851 births 1931 deaths Corresponding Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1917–1925) Corresponding Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Delft University of Technology alumni Delft University of Technology faculty Dutch microbiologists 19th-century Dutch botanists 20th-century Dutch botanists Dutch phytopathologists Environmental microbiology Foreign Members of the Royal Society Honorary Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Leeuwenhoek Medal winners Leiden University alumni Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Nitrogen cycle Scientists from Amsterdam Dutch soil scientists Wageningen University and Research faculty

virology

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host cells for reproduction, th ...

and environmental microbiology

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

. He is credited with the discovery of viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's ...

, which he called "''contagium vivum fluidum

''Contagium vivum fluidum'' (Latin: "contagious living fluid") was a phrase first used to describe a virus, and underlined its ability to slip through the finest-mesh filters then available, giving it almost liquid properties. Martinus Beijerinck ...

''".

Life

Early life and education

Born inAmsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

, Beijerinck studied at the Technical School of Delft, where he was awarded the degree of Chemical Engineer in 1872. He obtained his Doctor of Science degree from the University of Leiden

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; nl, Universiteit Leiden) is a public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. The university was founded as a Protestant university in 1575 by William, Prince of Orange, as a reward to the city of Le ...

in 1877.

At the time, Delft, then a Polytechnic

Polytechnic is most commonly used to refer to schools, colleges, or universities that qualify as an institute of technology or vocational university also sometimes called universities of applied sciences.

Polytechnic may also refer to:

Educatio ...

, did not have the right to confer doctorates, so Leiden did this for them. He became a teacher in microbiology at the Agricultural School in Wageningen (now Wageningen University

Wageningen University & Research (also known as Wageningen UR; abbreviation: WUR) is a public university in Wageningen, Netherlands, specializing in life sciences with a focus on agriculture, technical and engineering subjects. It is a globally ...

) and later at the ''Polytechnische Hogeschool Delft'' (Delft Polytechnic, currently Delft University of Technology

Delft University of Technology ( nl, Technische Universiteit Delft), also known as TU Delft, is the oldest and largest Dutch public technical university, located in Delft, Netherlands. As of 2022 it is ranked by QS World University Rankings among ...

) (from 1895). He established the Delft School of Microbiology. His studies of agricultural and industrial microbiology yielded fundamental discoveries in the field of biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

. His achievements have been perhaps unfairly overshadowed by those of his contemporaries, Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( , ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the bacteri ...

and Louis Pasteur, because unlike them, Beijerinck never studied human disease.

In 1877, he wrote his first notable research paper, discussing plant galls. The paper later became the basis for his doctoral dissertation.

In 1885 he became a member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Scientific career

He is considered one of the founders of

He is considered one of the founders of virology

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host cells for reproduction, th ...

. In 1898, he published results on the filtration experiments demonstrating that tobacco mosaic disease

''Tobacco mosaic virus'' (TMV) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus species in the genus '' Tobamovirus'' that infects a wide range of plants, especially tobacco and other members of the family Solanaceae. The infection causes characte ...

is caused by an infectious agent smaller than a bacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were amon ...

.

His results were in accordance with the similar observation made by Dmitri Ivanovsky

Dmitri Iosifovich Ivanovsky (alternative spelling ''Dmitrii'' or ''Dmitry Iwanowski''; russian: Дми́трий Ио́сифович Ивано́вский; 28 October 1864 – 20 June 1920) was a Russian botanist, the co-discoverer of :viruses ...

in 1892. Like Ivanovsky before him and Adolf Mayer, predecessor at Wageningen, Beijerinck could not culture the filterable infectious agent; however, he concluded that the agent can replicate and multiply in living plants. He named the new pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

''virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsk ...

'' to indicate its non-bacterial nature. Beijerinck asserted that the virus was somewhat liquid in nature, calling it "''contagium vivum fluidum

''Contagium vivum fluidum'' (Latin: "contagious living fluid") was a phrase first used to describe a virus, and underlined its ability to slip through the finest-mesh filters then available, giving it almost liquid properties. Martinus Beijerinck ...

''" (contagious living fluid). It was not until the first crystals of the tobacco mosaic virus

''Tobacco mosaic virus'' (TMV) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus species in the genus ''Tobamovirus'' that infects a wide range of plants, especially tobacco and other members of the family Solanaceae. The infection causes characteri ...

(TMV) obtained by Wendell Stanley

Wendell Meredith Stanley (16 August 1904 – 15 June 1971) was an American biochemist, virologist and Nobel laureate.

Biography

Stanley was born in Ridgeville, Indiana, and earned a BSc in Chemistry at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. ...

in 1935, the first electron micrographs of TMV produced in 1939 and the first X-ray crystallographic analysis of TMV performed in 1941 proved that the virus was particulate.

Nitrogen fixation

Nitrogen fixation is a chemical process by which molecular nitrogen (), with a strong triple covalent bond, in the air is converted into ammonia () or related nitrogenous compounds, typically in soil or aquatic systems but also in industry. Atmo ...

, the process by which diatomic nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

gas is converted to ammonium ions and becomes available to plants, was also investigated by Beijerinck. Bacteria perform nitrogen fixation, dwelling inside root nodules of certain plants ( legumes). In addition to having discovered a biochemical reaction vital to soil fertility and agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people t ...

, Beijerinck revealed this archetypical example of symbiosis between plants

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclude ...

and bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometr ...

.

Beijerinck discovered the phenomenon of bacterial sulfate reduction, a form of anaerobic respiration

Anaerobic respiration is respiration using electron acceptors other than molecular oxygen (O2). Although oxygen is not the final electron acceptor, the process still uses a respiratory electron transport chain.

In aerobic organisms undergoing r ...

. He learned bacteria could use sulfate as a terminal electron acceptor, instead of oxygen. This discovery has had an important impact on our current understanding of biogeochemical cycles

A biogeochemical cycle (or more generally a cycle of matter) is the pathway by which a chemical substance cycles (is turned over or moves through) the biotic and the abiotic compartments of Earth. The biotic compartment is the biosphere and th ...

. ''Spirillum desulfuricans'', now known as '' Desulfovibrio desulfuricans'', the first known sulfate-reducing bacterium, was isolated and described by Beijerinck.

Beijerinck invented the enrichment culture Enrichment culture is the use of certain growth media to favor the growth of a particular microorganism over others, enriching a sample for the microorganism of interest. This is generally done by introducing nutrients or environmental conditions t ...

, a fundamental method of studying microbes from the environment. He is often incorrectly credited with framing the microbial ecology idea that "everything is everywhere, but, the environment selects", which was stated by Lourens Baas Becking

Lourens Gerhard Marinus Baas Becking (4 January 1895 in Deventer – 6 January 1963 in Canberra, Australia) was a Dutch botanist and microbiologist. He is known for the Baas Becking hypothesis, which he originally formulated as ''"Everything ...

.

Personal life

Beijerinck was a socially eccentric figure. He was verbally abusive to students, never married, and had few professional collaborations. He was also known for his ascetic lifestyle and his view of science and marriage being incompatible. His low popularity with his students and their parents periodically depressed him, as he very much loved spreading his enthusiasm for biology in the classroom. After his retirement at the Delft School of Microbiology in 1921, at age 70, he moved to Gorssel where he lived for the rest of his life, together with his two sisters.Recognition

Beijerinckia

Beijerinckia is a free living nitrogen-fixing aerobic microbe. It has abundant of nitrogenase enzyme capable of nitrogen reduction.

''Beijerinckia'' is a genus of bacteria from the family of Beijerinckiaceae

The Beijerinckiaceae are a fami ...

(a genus of bacteria), Beijerinckiaceae

The Beijerinckiaceae are a family of Hyphomicrobiales named after the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Willem Beijerinck. '' Beijerinckia'' is a genus of free-living aerobic nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Acidotolerant ''Beijerinckiaceae'' has been sho ...

(a family of Hyphomicrobiales

The ''Hyphomicrobiales'' are an order of Gram-negative Alphaproteobacteria.

The rhizobia, which fix nitrogen and are symbiotic with plant roots, appear in several different families. The four families ''Nitrobacteraceae'', ''Hyphomicrobiaceae' ...

), and Beijerinck crater are named after him.

The M.W. Beijerinck Virology Prize The M.W. Beijerinck Virology Prize (''M.W. Beijerinck Virologie Prijs'') is a prize in virology awarded every two years by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, ''Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen'' (KNAW). The prize c ...

(''M.W. Beijerinck Virologie Prijs'') is awarded in his honor.

See also

*History of virology

The history of virology – the scientific study of viruses and the infections they cause – began in the closing years of the 19th century. Although Louis Pasteur and Edward Jenner developed the first vaccines to protect against viral infection ...

* Nitrification

''Nitrification'' is the biological oxidation of ammonia to nitrite followed by the oxidation of the nitrite to nitrate occurring through separate organisms or direct ammonia oxidation to nitrate in comammox bacteria. The transformation of am ...

* Clostridium beijerinckii

''Clostridium beijerinckii'' is a gram positive, rod shaped, motile bacterium of the genus ''Clostridium''. It has been isolated from feces and soil. Produces oval to subterminal spores. it is named after Martinus Beijerinck who is a Dutch bacte ...

* Sergei Winogradsky

References

External links

*Beijerinck and the Delft School of Microbiology

{{DEFAULTSORT:Beijerinck, Martinus 1851 births 1931 deaths Corresponding Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1917–1925) Corresponding Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Delft University of Technology alumni Delft University of Technology faculty Dutch microbiologists 19th-century Dutch botanists 20th-century Dutch botanists Dutch phytopathologists Environmental microbiology Foreign Members of the Royal Society Honorary Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Leeuwenhoek Medal winners Leiden University alumni Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Nitrogen cycle Scientists from Amsterdam Dutch soil scientists Wageningen University and Research faculty