The history of Atlanta dates back to 1836, when

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

decided to build a railroad to the

U.S. Midwest and a location was chosen to be the line's terminus. The stake marking the founding of "Terminus" was driven into the ground in 1837 (called the

Zero Mile Post). In 1839, homes and a store were built there and the settlement grew. Between 1845 and 1854, rail lines arrived from four different directions, and the rapidly growing town quickly became the rail hub for the entire

Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. During the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Atlanta, as a distribution hub, became the target of a

major Union campaign, and in 1864, Union

William Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

's troops set on fire and destroyed the city's assets and buildings, save churches and hospitals. After the war, the population grew rapidly, as did manufacturing, while the city retained its role as a rail hub. Coca-Cola was launched here in 1886 and grew into an Atlanta-based world empire. Electric streetcars arrived in 1889, and the city added new "

streetcar suburbs".

The city's elite black colleges were founded between 1865 and 1885, and despite disenfranchisement and the later imposition of

Jim Crow laws in the 1910s, a prosperous

black middle class

The African-American middle class consists of African-Americans who have middle-class status within the American class structure. It is a societal level within the African-American community that primarily began to develop in the early 1960s, ...

and

upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status, usually are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper class is gen ...

emerged. By the early 20th century,

"Sweet" Auburn Avenue was called "the most prosperous Negro street in the nation". In the 1950s, black people started moving into city neighborhoods that had previously kept them out, while Atlanta's first freeways enabled large numbers of whites to move to, and commute from, new suburbs. Atlanta was home to

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, and a major center for the

Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

. Resulting desegregation occurred in stages over the 1960s. Slums were razed and the new

Atlanta Housing Authority built public-housing projects.

From the mid-1960s to mid-'70s, nine suburban malls opened, and the downtown shopping district declined, but just north of it, gleaming office towers and hotels rose, and in 1976, the new

Georgia World Congress Center

The Georgia World Congress Center (GWCC) is a convention center in Atlanta, Georgia. Enclosing some 3.9 million ft2 (360,000 m2) in exhibition space and hosting more than a million visitors each year, the GWCC is the world's largest LEED certi ...

signaled Atlanta's rise as a major convention city. In 1973, the city elected its first black mayor,

Maynard Jackson

Maynard Holbrook Jackson Jr. (March 23, 1938 – June 23, 2003) was an American politician and attorney from Georgia. A member of the Democratic Party, he was elected in 1973 at the age of 35 as the first black mayor of Atlanta, Georgia and of ...

, and in ensuing decades, black political leaders worked successfully with the white business community to promote business growth, while still empowering black businesses. From the mid-'70s to mid-'80s most of the

MARTA rapid transit system was built. While the suburbs grew rapidly, much of the city itself deteriorated and the city lost 21% of its population between 1970 and '90.

In 1996, Atlanta hosted the

Summer Olympics, for which new facilities and infrastructure were built. Hometown airline

Delta continued to grow, and by 1998-1999,

Atlanta's airport was the busiest in the world. Since the mid-'90s,

gentrification

Gentrification is the process of changing the character of a neighborhood through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses. It is a common and controversial topic in urban politics and planning. Gentrification often increases the ec ...

has given new life to many of the city's

intown neighborhoods. The 2010 census showed affluent black people leaving the city for newer exurban properties and growing suburban towns, younger whites moving back to the city, and a much more diverse metropolitan area with heaviest growth in the exurbs at its outer edges.

Native American civilization: before 1836

The region where Atlanta and its suburbs were built was originally

Creek and

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

Native American territory. In 1813, the Creeks, who had been recruited by the British to assist them in the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, attacked and burned

Fort Mims Mims or MIMS may refer to:

Acronyms

* Mandarin Immersion Magnet School, Houston, Texas

* MediCiti Institute of Medical Sciences, a medical college near Hyderabad, India

* Membrane-introduction mass spectrometry

* Monthly Index of Medical Speciali ...

in southwestern

Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

. The conflict broadened and became known as the

Creek War. In response, the United States built a string of forts along the

Ocmulgee and

Chattahoochee Rivers, including Fort Daniel on top of Hog Mountain near present-day

Dacula, Georgia

Dacula ( ) is a city in Gwinnett County, Georgia, United States. It is an exurb of Atlanta, located approximately northeast of downtown. The population as of the 2010 census was 4,442, and the U.S. Census Bureau estimated the population to be 6, ...

, and Fort Gilmer. Fort Gilmer was situated next to an important Indian site called

Standing Peachtree, a

Creek Indian

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands[Peachtree Creek

Peachtree Creek is a major stream in Atlanta. It flows for U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 15, 2011 almost due west into the Chattahoochee River just south of Vi ...]

flows into the Chattahoochee. The fort was soon renamed Fort Peachtree. A road was built linking Fort Peachtree and Fort Daniel following the route of existing trails.

As part of the systematic removal of Native Americans from northern Georgia from 1802 to 1825, the Creek ceded the area that is now metro Atlanta in 1821. Four months later, the

Georgia Land Lottery Act created five new counties in the area that would later become Atlanta. Dekalb County was created in 1822, from portions of Henry, Fayette, and Gwinnett Counties, and

Decatur was created as its county seat the following year. As part of the land lottery, Archibald Holland received a grant for District 14, Land Lot 82: an area of 202.5 acres near the present-day Coca-Cola headquarters. Holland farmed the land and operated a blacksmith shop. However, the land was low-lying and wet, so his cattle often became mired in the mud. He left the area in 1833 to farm in Paulding County.

In 1830, an inn was established that became known as Whitehall due to the then-unusual fact that it had a coat of white paint, when most other buildings were of washed or natural wood. Later, Whitehall Street was built as the road from Atlanta to Whitehall. The Whitehall area was renamed

West End in 1867 and is the oldest intact

Victorian neighborhood of Atlanta.

In 1835, some leaders of the Cherokee Nation ceded their territory to the United States without the consent of the majority of the Cherokee people in exchange for land out west under the

Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia, by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party.

The treaty established ter ...

, an act that led to the

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

.

From railroad terminus to Atlanta: 1836–1860

In 1836, the

Georgia General Assembly voted to build the

Western and Atlantic Railroad

The Western & Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia (W&A) is a railroad owned by the State of Georgia and currently leased by CSX, which CSX operates in the Southeastern United States from Atlanta, Georgia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee.

It was fo ...

to provide a link between the

port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

of

Savannah and the

Midwest.

The initial route of that state-sponsored project was to run from

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020 ...

, to a spot east of the

Chattahoochee River, in present-day

Fulton County Fulton County is the name of eight counties in the United States of America. Most are named for Robert Fulton, inventor of the first practical steamboat:

*Fulton County, Arkansas, named after Governor William Savin Fulton

*Fulton County, Georgia

*F ...

. The plan was to eventually link up with the

Georgia Railroad

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

from

Augusta, and with the

Macon and Western Railroad The Macon and Western Railroad was an American railway company that operated in Georgia in the middle of the 19th century. Originally chartered as the Monroe Railroad and Banking Company in December 1833, it was not until 1838 that it opened for bus ...

, which ran between

Macon and Savannah. A

U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

engineer, Colonel Stephen Harriman Long, was asked to recommend the location where the Western and Atlantic line would terminate. He surveyed various possible routes, then in the autumn of 1837, drove a stake into the ground between what are now Forsyth Street and Andrew Young International Boulevard, about three or four blocks northwest of today's

Five Points.

The zero milepost was later placed to mark that spot.

In 1839,

John Thrasher built homes and a

general store in this vicinity, and the settlement was nicknamed Thrasherville. A marker identifies the location of Thrasherville at 104

Marietta Street, NW, in front of the

State Bar of Georgia Building

The State Bar of Georgia Building is located at 104 Marietta St. NW in Downtown Atlanta. The building opened in 1918, and was designed by A. Ten Eyck Brown, one of the most notable architects of public buildings in Atlanta in the first third ...

, between Spring and Cone Streets.

() At this point, Thrasher built th

Monroe Embankment an earthen embankment to carry the Monroe Railway to meet the W&A at the terminus. This is the oldest existing man-made structure in

downtown Atlanta

Downtown Atlanta is the central business district of Atlanta, Georgia, United States. The larger of the city's two other commercial districts ( Midtown and Buckhead), it is the location of many corporate and regional headquarters; city, county ...

.

[

In 1842, the planned terminus location was moved, four blocks southeast (two to three blocks southeast of Five Points), to what would become ]State Square

State Square was the central square of antebellum Atlanta, Georgia. The original Atlanta Union Depot designed by Edward A. Vincent stood in the middle of the square. The square was bounded by Marietta Street (now Decatur Street) on the northeast ...

, on Wall Street between Central Avenue and Pryor Street. (). At this location, the zero milepost can now be found, adjacent to the southern entrance of Underground Atlanta

Underground Atlanta is a shopping and entertainment district in the Five Points neighborhood of downtown Atlanta, Georgia, United States, near the Five Points MARTA station. It is currently undergoing renovations. First opened in 1969, it takes ...

.Buckhead

Buckhead is the uptown commercial and residential district of the city of Atlanta, Georgia, comprising approximately the northernmost fifth of the city. Buckhead is the third largest business district within the Atlanta city limits, behind Downto ...

section of Atlanta, several miles north of today's downtown. In 1838, Henry Irby started a tavern and grocery at what became the intersection of Paces Ferry and Roswell Roads.

In 1842, when a two-story brick depot was built, the locals asked that the settlement of Terminus be called Lumpkin, after

In 1842, when a two-story brick depot was built, the locals asked that the settlement of Terminus be called Lumpkin, after Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Wilson Lumpkin. Gov. Lumpkin asked them to name it after his young daughter (Martha Atalanta Lumpkin) instead, and Terminus became Marthasville; it was officially incorporated on December 23, 1843. In 1845, the chief engineer of the Georgia Railroad ( J. Edgar Thomson) suggested that Marthasville be renamed "Atlantica-Pacifica", which was quickly shortened to "Atlanta". Wilson Lumpkin seems to have supported the change, reporting that Martha's middle name was ''Atalanta''. The residents approved the name change, apparently undaunted by the fact that not a single train had yet visited. Act 109 of the Georgia General Assembly enacted the name change, which was approved December 26, 1845,mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

took office in January 1848.

Growth and development into a regional rail hub

The first Georgia Railroad

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

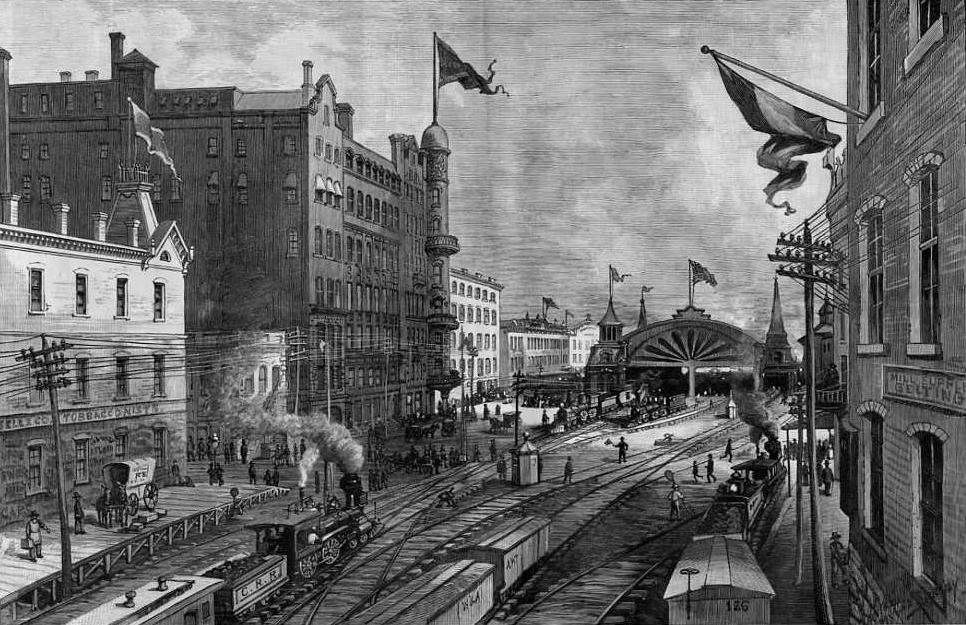

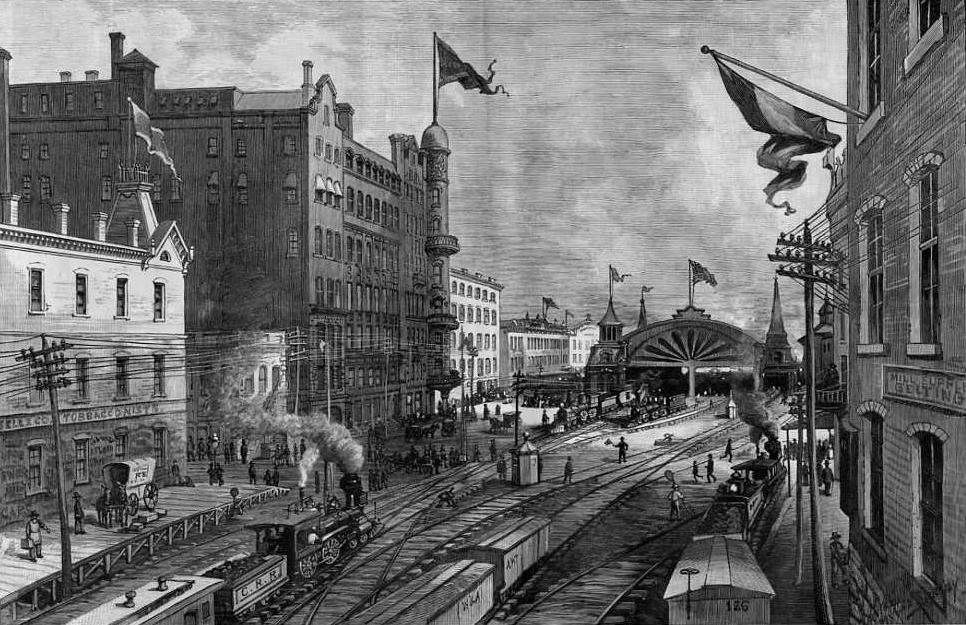

freight and passenger trains from Augusta (to the east of Atlanta), arrived in September 1845 and in that year the first hotel, the Atlanta Hotel, was opened. The railroad was the chief stimulus to the town's growth, with several lines being added.Western and Atlantic Railroad

The Western & Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia (W&A) is a railroad owned by the State of Georgia and currently leased by CSX, which CSX operates in the Southeastern United States from Atlanta, Georgia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee.

It was fo ...

- for which the site of Atlanta had been identified as a terminus - finally arrived, connecting Atlanta to Chattanooga in the northwest and opening up Georgia to trade with the Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

and Ohio River Valleys, and the American Midwest. The union depot was completed in 1853 on State Square

State Square was the central square of antebellum Atlanta, Georgia. The original Atlanta Union Depot designed by Edward A. Vincent stood in the middle of the square. The square was bounded by Marietta Street (now Decatur Street) on the northeast ...

. That year, the depot's architect, Edward A. Vincent, also delivered Atlanta's first official map to the city council.

Fulton County Fulton County is the name of eight counties in the United States of America. Most are named for Robert Fulton, inventor of the first practical steamboat:

*Fulton County, Arkansas, named after Governor William Savin Fulton

*Fulton County, Georgia

*F ...

was established in 1853 from the western section of DeKalb DeKalb or De Kalb may refer to:

People

* Baron Johann de Kalb (1721–1780), major general in the American Revolutionary War

Places Municipalities in the United States

* DeKalb, Illinois, the largest city in the United States named DeKalb

**DeKal ...

, and in 1854, a combination Fulton County Court House and Atlanta City Hall was built– which would be razed 30 years later to make way for today's State Capitol building. (After the Civil War, the Georgia General Assembly decided to move the state capital

Below is an index of pages containing lists of capital cities.

National capitals

*List of national capitals

* List of national capitals by latitude

*List of national capitals by population

* List of national capitals by area

* List of capital c ...

from Milledgeville to Atlanta.)[

In 1854, a fourth rail line, the Atlanta and LaGrange Rail Road (later ]Atlanta & West Point Railroad

The Atlanta and West Point Rail Road was a railroad in the U.S. state of Georgia, forming the east portion of the Atlanta- Selma West Point Route. The company was chartered in 1847 as the Atlanta and LaGrange Rail Road and renamed in 1857; constr ...

) arrived, connecting Atlanta with LaGrange, Georgia, to the southwest, sealing Atlanta's role as a rail hub for the entire South, with lines to the northwest, east, southeast, and southwest.

By 1855, the town had grown to 6,025 residents and had a bank, a daily newspaper, a factory to build freight cars, a new brick depot, property taxes, a gasworks, gas street lights, a theater, a medical college, and juvenile delinquency.

Manufacturing and commerce

The first true manufacturing establishment was opened in 1844, when Jonathan Norcross, who later became mayor of Atlanta, arrived in Marthasville and built a sawmill. Richard Peters, Lemuel Grant, and John Mims built a three-story flour mill, which was used as a pistol factory during the Civil War. In 1848, Austin Leyden started the town's first foundry and machine shop, which was later the Atlanta Machine Works.rolling mill

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simil ...

. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

it rolled out cannon, iron rail, and sheets of iron to clad the CSS ''Virginia'' for the Confederate navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the American ...

. The mill was destroyed by the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

in 1864.[

The city became a busy center for ]cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

distribution. As an example, in 1859, the Georgia Railroad

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

alone sent 3,000 empty rail cars to the city to be loaded with cotton.

By 1860, the city had four large machine shops, two planing mills, three tanneries, two shoe factories, a soap factory, and clothing factories employing 75 people.[

]

Slavery in antebellum Atlanta

In 1850, out of 2,572 people, 493 were enslaved African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s, and 18 were free blacks, for a total black population of 20%. The black proportion of Atlanta's population became much higher after the Civil War, when freed slaves came to Atlanta in search of opportunity.

Several slave auction houses were in the town, which advertised in the newspapers and many of which also traded in manufactured goods.

Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861–1871

Civil War: 1861–1865

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Atlanta served as an important railroad and military supply hub. (See also: Atlanta in the Civil War.) In 1864, the city became the target of a major Union invasion (the setting for the 1939 film ''Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind may also refer to:

Music

* ''Gone with the Wind'' ...

''). The area now covered by Atlanta was the scene of several battles, including the Battle of Peachtree Creek

The Battle of Peachtree Creek was fought in Georgia on July 20, 1864, as part of the Atlanta Campaign in the American Civil War. It was the first major attack by Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood since taking command of the Confederate Army of Tennessee ...

, the Battle of Atlanta

The Battle of Atlanta was a battle of the Atlanta Campaign fought during the American Civil War on July 22, 1864, just southeast of Atlanta, Georgia. Continuing their summer campaign to seize the important rail and supply hub of Atlanta, Un ...

, and the Battle of Ezra Church. General Sherman cut the last supply line to Atlanta at the Battle of Jonesboro

The Battle of Jonesborough (August 31–September 1, 1864) was fought between Union Army forces led by William Tecumseh Sherman and Confederate forces under William J. Hardee during the Atlanta Campaign in the American Civil War. On the first ...

fought on August 31 – September 1.[O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, OR # 1, p 80] With all of his supply lines cut, Confederate General John Bell Hood

John Bell Hood (June 1 or June 29, 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Although brave, Hood's impetuosity led to high losses among his troops as he moved up in rank. Bruce Catton wrote that "the de ...

was forced to abandon Atlanta. On the night of September 1, his troops marched out of the city to Lovejoy, Georgia

Lovejoy is a city in Clayton County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 6,422, up from 2,495 in 2000. During the American Civil War, it was the site of the Battle of Lovejoy's Station during the Atlanta ...

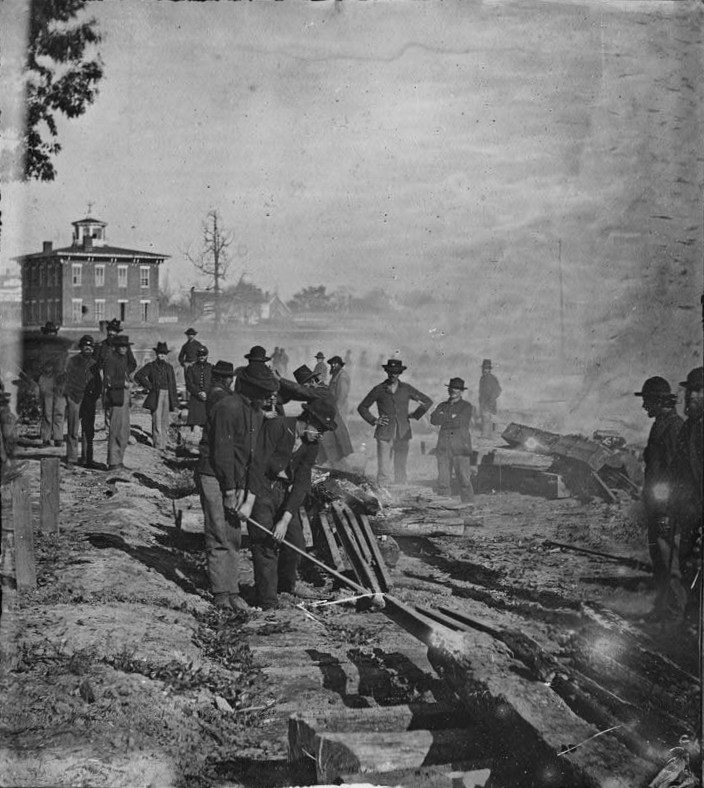

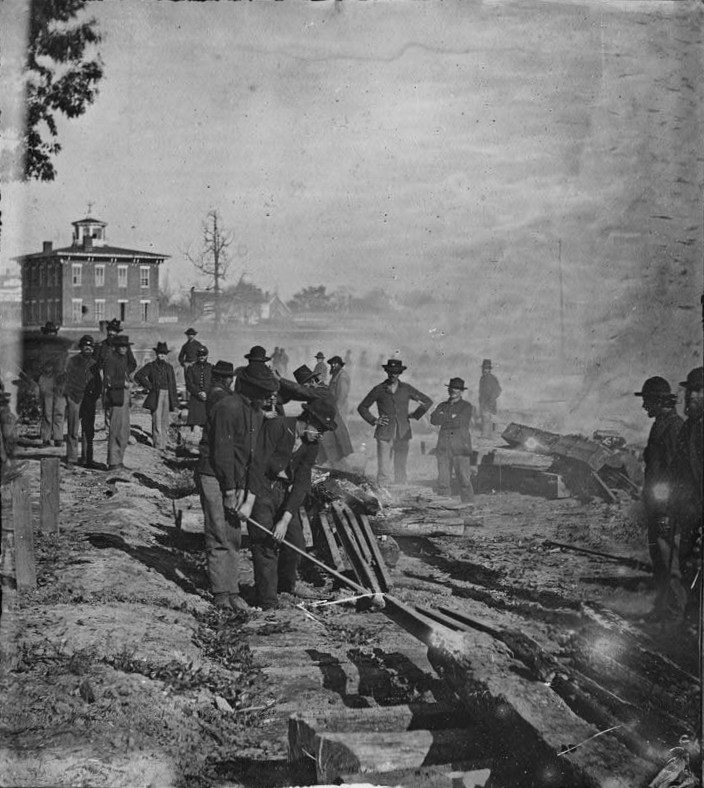

. General Hood ordered that the 81 rail cars filled with ammunition and other military supplies be destroyed. The resulting fire and explosions were heard for miles. The next day, Mayor James Calhoun surrendered the city, and on September 7 Sherman ordered the civilian population to evacuate. He then ordered Atlanta burned to the ground on November 11 in preparation for his punitive march south.

After a plea by the Bishops of the Episcopal and Catholic churches in Atlanta, Sherman did not burn the city's churches or hospitals. The remaining war resources were then destroyed in the aftermath in Sherman's March to the Sea

Sherman's March to the Sea (also known as the Savannah campaign or simply Sherman's March) was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, maj ...

. The fall of Atlanta was a critical point in the Civil War. Its much publicized fall gave confidence to the Northerners. Together with the Battle of Mobile Bay

The Battle of Mobile Bay of August 5, 1864, was a naval and land engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fle ...

, the fall of Atlanta led to the re-election of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and the eventual surrender of the Confederacy.

Reconstruction: 1865–1871

The city emerged from the ashes – hence the city's symbol, the phoenix

Phoenix most often refers to:

* Phoenix (mythology), a legendary bird from ancient Greek folklore

* Phoenix, Arizona, a city in the United States

Phoenix may also refer to:

Mythology

Greek mythological figures

* Phoenix (son of Amyntor), a ...

– and was gradually rebuilt, as its population increased rapidly after the war. Atlanta received migrants from surrounding counties and states: from 1860 to 1870 Fulton County more than doubled in population, from 14,427 to 33,446. In a pattern seen across the South after the Civil War, many freedmen moved from plantations to towns or cities for work, including Atlanta; Fulton County went from 20.5% black in 1860 to 45.7% black in 1870.

Food supplies were erratic due to poor harvests, which were a result of the turmoil in the agricultural labor supply after emancipation of the slaves. Many refugees were destitute without even proper clothing or shoes; the AMA helped fill the gap with food, shelter, and clothing, and the federally sponsored Freedmen's Bureau also offered much help, though erratically.

Food supplies were erratic due to poor harvests, which were a result of the turmoil in the agricultural labor supply after emancipation of the slaves. Many refugees were destitute without even proper clothing or shoes; the AMA helped fill the gap with food, shelter, and clothing, and the federally sponsored Freedmen's Bureau also offered much help, though erratically.[Allison Dorsey, ''To Build Our Lives Together'', p. 34ff.]

/ref>

The destruction of the housing stock by the Union army, together with the massive influx of refugees, resulted in a severe housing shortage. Some to lots with a small house rented for $5 per month, while those with a glass pane rented for $20. High rents rather than laws led to ''de facto'' segregation, with most black people settling in three shantytown areas at the city's edge. There, housing was substandard; an AMA missionary remarked that many houses were "rickety shacks" rented at inflated rates. Two of the three shantytowns sat in low-lying areas, prone to flooding and sewage overflows, which resulted in outbreaks of disease in the late 19th century.[ A shantytown named Tight Squeeze developed at Peachtree at what is now 10th Street in ]Midtown Atlanta

Midtown Atlanta, or Midtown, is a high-density commercial and residential neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia. The exact geographical extent of the area is ill-defined due to differing definitions used by the city, residents, and local business ...

. It was infamous for vagrancy, desperation, and robberies of merchants transiting the settlement.

A smallpox epidemic hit Atlanta in December 1865, with few doctors or hospital facilities to help. Another epidemic hit in fall, 1866; hundreds died.[

Construction created many new jobs, and employment boomed. Atlanta soon became the industrial and commercial center of the South. From 1867 until 1888, U.S. Army soldiers occupied McPherson Barracks (later renamed Fort McPherson) in southwest Atlanta to ensure Reconstruction-era reforms. In 1868, Atlanta became the Georgia state capital, taking over from Milledgeville.

]

Center of black education

Atlanta quickly became a center of black education. Atlanta University was established in 1865, the forerunner of Morehouse College in 1867, Clark University

Clark University is a private research university in Worcester, Massachusetts. Founded in 1887 with a large endowment from its namesake Jonas Gilman Clark, a prominent businessman, Clark was one of the first modern research universities in the ...

in 1869, Spelman College

Spelman College is a private, historically black, women's liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. It is part of the Atlanta University Center academic consortium in Atlanta. Founded in 1881 as the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, Spelman rece ...

in 1881, and Morris Brown College in 1881. This was one of several factors aiding the establishment of one of the nation's oldest and best-established African-American elite in Atlanta.

Gate City of the New South: 1872-1905

The New South

Henry W. Grady, the editor of the ''Atlanta Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the only major daily newspaper in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger between ...

'', promoted the city to investors as a city of the "New South

New South, New South Democracy or New South Creed is a slogan in the history of the American South first used after the American Civil War. Reformers used it to call for a modernization of society and attitudes, to integrate more fully with the ...

", by which he meant a diversification of the economy away from agriculture, and a shift from the "Old South

Geographically, the U.S. states known as the Old South are those in the Southern United States that were among the original Thirteen Colonies. The region term is differentiated from the Deep South and Upper South.

From a cultural and social ...

" attitudes of slavery and rebellion. As part of the effort to modernize the South, Grady and many others also supported the creation of the Georgia School of Technology

The Georgia Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Georgia Tech or, in the state of Georgia, as Tech or The Institute, is a public research university and institute of technology in Atlanta, Georgia. Established in 1885, it is part of ...

(now the Georgia Institute of Technology), which was founded on the city's northern outskirts in 1885. With Grady's support, the Confederate Soldiers' Home was built in 1889.

In 1880, Sister Cecilia Carroll, RSM, and three companions traveled from Savannah, Georgia to Atlanta to minister to the sick. With just 50 cents in their collective purse, the sisters opened the Atlanta Hospital, the first medical facility in the city after the Civil War. This later became known as Saint Joseph's Hospital.

Expansion and the first planned suburbs

Starting in 1871, horse-drawn, and later, starting in 1888, electric streetcars fueled real estate development and the city's expansion. Washington Street south of downtown and Peachtree Street north of the central business district became wealthy residential areas.

In the 1890s, West End became the suburb of choice for the city's elite, but Inman Park, planned as a harmonious whole, soon overtook it in prestige. Peachtree Street's mansions reached ever further north into what is now Midtown Atlanta, including Amos G. Rhodes' (founder of the Rhodes Furniture Company in 1875) mansion, Rhodes Hall, which can still be visited.

Atlanta surpassed Savannah as Georgia's largest city by 1880.

Starting in 1871, horse-drawn, and later, starting in 1888, electric streetcars fueled real estate development and the city's expansion. Washington Street south of downtown and Peachtree Street north of the central business district became wealthy residential areas.

In the 1890s, West End became the suburb of choice for the city's elite, but Inman Park, planned as a harmonious whole, soon overtook it in prestige. Peachtree Street's mansions reached ever further north into what is now Midtown Atlanta, including Amos G. Rhodes' (founder of the Rhodes Furniture Company in 1875) mansion, Rhodes Hall, which can still be visited.

Atlanta surpassed Savannah as Georgia's largest city by 1880.

Disenfranchisement of black people

As Atlanta grew, ethnic and racial tensions mounted. Late 19th- and early 20th-century immigration added a very small number of new Europeans to the mix. After Reconstruction, whites had used a variety of tactics, including militias and legislation, to re-establish political and social supremacy throughout the South. Starting with a poll tax in 1877, by the turn of the century, Georgia passed a variety of legislation that completed the disfranchisement of black people. Not even college-educated men could vote. Nonetheless, African Americans in Atlanta had been developing their own businesses, institutions, churches, and a strong, educated middle class. Meanwhile, the 2nd Ku Klux Klan era, (19151944) headed by William J. Simmons, and the 3rd Ku Klux Klan era, (1946present) headed by Dr. Samuel Green, both started off in Atlanta.

Coca-Cola

The identities of Atlanta and Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola, or Coke, is a carbonated soft drink manufactured by the Coca-Cola Company. Originally marketed as a temperance drink and intended as a patent medicine, it was invented in the late 19th century by John Stith Pemberton in Atlant ...

have been intertwined since 1886, when John Pemberton developed the soft drink in response to Atlanta and Fulton County going "dry". The first sales were at Jacob's Pharmacy in Atlanta. Asa Griggs Candler

Asa Griggs Candler (December 30, 1851 – March 12, 1929) was an American business tycoon and politician who in 1888 purchased the Coca-Cola recipe for $238.98 from chemist John Stith Pemberton in Atlanta, Georgia. Candler founded The Coca-C ...

acquired a stake in Pemberton's company in 1887 and incorporated it as the Coca Cola Company

The Coca-Cola Company is an American multinational beverage corporation founded in 1892, best known as the producer of Coca-Cola. The Coca-Cola Company also manufactures, sells, and markets other non-alcoholic beverage concentrates and syrups ...

in 1888.World of Coca-Cola

The World of Coca-Cola is a museum, located in Atlanta, Georgia, showcasing the history of the Coca-Cola Company. The complex opened to the public on May 24, 2007, relocating from and replacing the original exhibit, which was founded in 1990 in ...

, which has remained one of the city's top visitor attractions.

Cotton States Expo and Booker T. Washington speech

In 1895, the Cotton States and International Exposition was held at what is now Piedmont Park. Nearly 800,000 visitors attended the event. The exposition was designed to promote the region to the world and showcase products and new technologies, as well as to encourage trade with Latin America. The exposition featured exhibits from several states, including various innovations in agriculture and technology. President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

presided over the opening of the exposition, but the event is best remembered for the both hailed and criticized "Atlanta Compromise" speech given by Booker T. Washington in which Southern black people would work meekly and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that black people would receive basic education and due process in law.

Streetcar suburbs and World War II: 1906–1945

1906 massacre and results

Competition between working-class whites and black for jobs and housing gave rise to fears and tensions. In 1906, print media fueled these tensions with hearsay about alleged sexual assaults on white women by Black men, triggering the Atlanta massacre of 1906, which left at least 27 people dead (25 of them black) and over 70 injured. Many Black businesses were destroyed.

Competition between working-class whites and black for jobs and housing gave rise to fears and tensions. In 1906, print media fueled these tensions with hearsay about alleged sexual assaults on white women by Black men, triggering the Atlanta massacre of 1906, which left at least 27 people dead (25 of them black) and over 70 injured. Many Black businesses were destroyed.

Rise of Sweet Auburn

Black businesses started to move from the previously integrated business district downtown to the relative safety of the area around the Atlanta University Center

The Atlanta University Center Consortium (AUC Consortium) is the oldest and largest contiguous consortium of African-American higher education institutions in the United States. The center consists of four historically black colleges and univers ...

west of downtown, and to Auburn Avenue in the Fourth Ward east of downtown. "Sweet" Auburn Avenue became home to Alonzo Herndon

Alonzo Franklin Herndon (June 26, 1858 Walton County, Georgia – July 21, 1927) was an African-American entrepreneur and businessman in Atlanta, Georgia. Born into slavery, he became one of the first African American millionaires in the Unit ...

's Atlanta Mutual, the city's first black-owned life insurance company, and to a celebrated concentration of black businesses, newspapers, churches, and nightclubs. In 1956, '' Fortune'' magazine called Sweet Auburn "the richest Negro street in the world", a phrase originally coined by civil-rights leader John Wesley Dobbs. Sweet Auburn and Atlanta's elite black colleges formed the nexus of a prosperous black middle class

The African-American middle class consists of African-Americans who have middle-class status within the American class structure. It is a societal level within the African-American community that primarily began to develop in the early 1960s, ...

and upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status, usually are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper class is gen ...

, which arose despite enormous social and legal obstacles.

Jim Crow laws

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

were passed in swift succession in the years after the riot. The result was in some cases segregated facilities, with nearly always inferior conditions for black customers, but in many cases it resulted in no facilities at all available to black people, e.g. all parks were designated whites-only (although a private park, Joyland, did open in 1921). In 1910, the city council passed an ordinance requiring that restaurants be designated for one race only, hobbling black restaurant owners who had been attracting both black and white customers. In the same year, Atlanta's streetcars were segregated, with black patrons required to sit in the rear. If not enough seats were available for all white riders, the black people sitting furthest forward in the trolley were required to stand and give their seats to whites. In 1913, the city created official boundaries for white and black residential areas. And in 1920, the city prohibited black-owned salons from serving white women and children.

Beyond this, black people were subject to the South's "racial protocol", whereby, according to the ''New Georgia Encyclopedia'':

l blacks were required to pay obeisance to all whites, even those whites of low social standing. And although they were required to address whites by the title "sir," blacks rarely received the same courtesy themselves. Because even minor breaches of racial etiquette often resulted in violent reprisals, the region's codes of deference transformed daily life into a theater of ritual, where every encounter, exchange, and gesture reinforced black inferiority.

In 1913, Leo Frank

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884August 17, 1915) was an American factory superintendent who was convicted in 1913 of the murder of a 13-year-old employee, Mary Phagan, in Atlanta, Georgia. His trial, conviction, and appeals attracted national at ...

, a Jewish supervisor at a factory in Atlanta, was put on trial for raping and murdering a 13-year-old white employee from Marietta, a suburb of Atlanta. After doubts about Frank's guilt led his death sentence to be commuted in 1915, riots broke out in Atlanta among whites. They kidnapped Frank from the State Prison Farm in the city of Milledgeville, with the collusion of prison guards, and took him to Marietta, where he was lynched. Later that year, the Klan was reborn in Atlanta.

Country music scene

Many Appalachian people came to Atlanta to work in the cotton mills and brought their music with them. Starting with a 1913 fiddler's convention, Atlanta became the center of a thriving country-music scene. Atlanta was an important center for country music recording and talent recruiting in the 1920s and 1930s, and a live music center for an additional two decades after that.

Growth

In 1914, Asa Griggs Candler

Asa Griggs Candler (December 30, 1851 – March 12, 1929) was an American business tycoon and politician who in 1888 purchased the Coca-Cola recipe for $238.98 from chemist John Stith Pemberton in Atlanta, Georgia. Candler founded The Coca-C ...

, the founder of The Coca-Cola Company

The Coca-Cola Company is an American multinational beverage corporation founded in 1892, best known as the producer of Coca-Cola. The Coca-Cola Company also manufactures, sells, and markets other non-alcoholic beverage concentrates and syrup ...

and brother to former Emory President Warren Candler, persuaded the Methodist Episcopal Church South

The Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MEC, S; also Methodist Episcopal Church South) was the American Methodist denomination resulting from the 19th-century split over the issue of slavery in the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC). Disagreement ...

to build the new campus of Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

in the emerging affluent suburb of Druid Hills, which borders northeastern Atlanta.

In 1916, Candler was elected mayor of Atlanta (taking office in 1917). As mayor he balanced the city budget and coordinated rebuilding efforts after the Great Atlanta fire of 1917

The Great Atlanta Fire of 1917 began just after noon on 21 May 1917 in the Old Fourth Ward of Atlanta, Georgia. It is unclear just how the fire started, but it was fueled by hot temperatures and strong winds which propelled the fire. The fire, ...

destroyed 1,500 homes. He also made large personal loans in order to develop the water and sewage facilities of the city of Atlanta, in order to provide the infrastructure necessary to a modern city.

Candler was also a philanthropist, endowing numerous schools and universities (he gave a total of $7 million to Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

,) and the Candler Hospital in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the British colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later t ...

. Candler had paid to relocate Emory University from Oxford, Georgia

Oxford is a city in Newton County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 2,134. It is the location of Oxford College of Emory University.

Much of the city is part of the National Parks-designated Oxford Histori ...

, to Atlanta.

Great Atlanta Fire of 1917

On May 21, 1917, the Great Atlanta Fire destroyed 1,938 buildings, mostly wooden, in what is now the Old Fourth Ward. The fire resulted in 10,000 people becoming homeless. Only one person died, a woman who died of a heart attack when seeing her home in ashes.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression hit Atlanta. With the city government nearing bankruptcy, the Coca-Cola Company had to help bail out the city's deficit. The federal government stepped in to help Atlantans by establishing Techwood Homes, the nation's first federal housing project in 1935.

On the political scene, between March and May 1930, the police arrested six communist leaders, who became known as the Atlanta Six, under a restoration-era insurrection statute. These leaders were Morris H. Powers, Joseph Carr, Mary Dalton, Ann Burlak, Herbert Newton, and Henry Storey. During the summer of 1930, approximately 150 Atlanta business leaders, American Legion members, and members of law enforcement founded the American Fascisti Association and Order of the Black Shirts with the goal to "foster the principles of white supremacy". By 1932, the city began to deny the Black Shirts permits for parades and charters. In 1932, Angelo Herndon

Angelo Braxton Herndon (May 6, 1913 in Wyoming, Ohio – December 9, 1997 in Sweet Home, Arkansas) was an African-American labor organizer arrested and convicted of insurrection after attempting to organize black and white industrial workers in ...

was arrested and charged under the insurrection statute for being in possession of communist literature. Herndon's defense team, including attorney Benjamin J. Davis Jr., countered that by systemically excluding Black Americans from the jury pool, the criminal justice system was violating Herndon's civil rights, making the verdict invalid. The defense team appealed the decision to the Supreme Court twice and secured a decision against the insurrection statute in 1937.

''Gone with the Wind'' premiere

On December 15, 1939, Atlanta hosted the premiere of ''Gone with the Wind'', the movie based on Atlanta resident Margaret Mitchell

Margaret Munnerlyn Mitchell (November 8, 1900 – August 16, 1949) was an American novelist and journalist. Mitchell wrote only one novel, published during her lifetime, the American Civil War-era novel '' Gone with the Wind'', for which she wo ...

's best-selling novel. Stars Clark Gable

William Clark Gable (February 1, 1901November 16, 1960) was an American film actor, often referred to as "The King of Hollywood". He had roles in more than 60 motion pictures in multiple genres during a career that lasted 37 years, three decades ...

, Vivien Leigh, and Olivia de Havilland

Dame Olivia Mary de Havilland (; July 1, 1916July 26, 2020) was a British-American actress. The major works of her cinematic career spanned from 1935 to 1988. She appeared in 49 feature films and was one of the leading actresses of her time. ...

were in attendance. The premiere was held at Loew's Grand Theatre, at Peachtree and Forsyth Streets, current site of the Georgia-Pacific building. An enormous crowd, numbering 300,000 people according to the ''Atlanta Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the only major daily newspaper in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger between ...

'', filled the streets on an ice-cold night in Atlanta. A rousing ovation greeted a group of Confederate veterans who were guests of honor.

Absence of film's black stars at event

Noticeably absent was Hattie McDaniel

Hattie McDaniel (June 10, 1893October 26, 1952) was an American actress, singer-songwriter, and comedian. For her role as Mammy in ''Gone with the Wind (film), Gone with the Wind'' (1939), she won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, ...

, who won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role as Mammy, as well as Butterfly McQueen

Butterfly McQueen (born Thelma McQueen; January 8, 1911December 22, 1995) was an American actress. Originally a dancer, McQueen first appeared in films as "Prissy" in '' Gone with the Wind'' (1939). She was unable to attend the film's premiere b ...

(Prissy). The black actors were barred from attending the premiere, from appearing in the souvenir program, and from all the film's advertising in the South. Director David Selznick had attempted to bring McDaniel to the premiere, but MGM

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded on April 17, 1924 a ...

advised him not to do so. Clark Gable angrily threatened to boycott the premiere, but McDaniel convinced him to attend, anyway. McDaniel did attend the Hollywood debut thirteen days later, and was featured prominently in the program.

Controversial participation of Martin Luther King Sr.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

sang at the gala as part of a children's choir of his father's church, Ebenezer Baptist. The boys dressed as pickaninnies and the girls wore "Aunt Jemima

Pearl Milling Company (formerly known as Aunt Jemima from 1889 to 2021) is an American breakfast brand for Baking mix, pancake mix, syrup, and other breakfast food products. The original version of the pancake mix for the brand was developed i ...

"-style bandanas, the dress seen by many black people as humiliating. John Wesley Dobbs tried to dissuade Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., from participating at the whites-only event, and Rev. King was harshly criticized in the black community.

Transportation hub

In 1941, Delta Air Lines

Delta Air Lines, Inc., typically referred to as Delta, is one of the major airlines of the United States and a legacy carrier. One of the world's oldest airlines in operation, Delta is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia. The airline, along w ...

moved its headquarters to Atlanta. Delta became the world's largest airline in 2008 after acquiring Northwest Airlines

Northwest Airlines Corp. (NWA) was a major American airline founded in 1926 and absorbed into Delta Air Lines, Inc. by a merger. The merger, approved on October 29, 2008, made Delta the largest airline in the world until the American Airlines ...

.

World War II

With the entry of the United States into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, soldiers from around the Southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also referred to as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical region of the United States. It is located broadly on the eastern portion of the southern United States and the southern por ...

went through Atlanta to train and later be discharged at Fort McPherson. War-related manufacturing such as the Bell Aircraft

The Bell Aircraft Corporation was an American aircraft manufacturer, a builder of several types of fighter aircraft for World War II but most famous for the Bell X-1, the first supersonic aircraft, and for the development and production of man ...

factory in the suburb of Marietta helped boost the city's population and economy. Shortly after the war in 1946, the Communicable Disease Center, later called the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency, under the Department of Health and Human Services, and is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgi ...

was founded in Atlanta from the old Malaria Control in War Areas offices and staff.

Suburbanization and Civil Rights: 1946–1989

In 1951, the city received the

In 1951, the city received the All-America City Award

The All-America City Award is a community recognition program in the United States given by the National Civic League. The award recognizes the work of communities in using inclusive civic engagement to address critical issues and create strong ...

due to its rapid growth and high standard of living in the southern U.S.

Annexation was the central strategy for growth. In 1952, Atlanta annexed Buckhead

Buckhead is the uptown commercial and residential district of the city of Atlanta, Georgia, comprising approximately the northernmost fifth of the city. Buckhead is the third largest business district within the Atlanta city limits, behind Downto ...

as well as vast areas of what are now northwest, southwest, and south Atlanta, adding and tripling its area. By doing so, 100,000 new affluent white residents were added, preserving white political power, expanding the city's property tax base, and enlarging the traditional white upper middle class leadership. This class now had room to expand inside the city limits.

Federal court decisions in 1962 and1963 ended the county-unit system, thus greatly reducing rural Georgia control over the state legislature, enabling Atlanta and other cities to gain proportional political power. The federal courts opened the Democratic Party primary to black voters, who surged in numbers and became increasingly well organized through the Atlanta Negro Voters League.

Blockbusting and racial transition in neighborhoods

In the late 1950s, after forced-housing patterns were outlawed, violence, intimidation, and organized political pressure were used in some white neighborhoods to discourage black people from buying homes there. However, by the late 1950s, such efforts proved futile as blockbusting drove whites to sell their homes in neighborhoods such as Adamsville, Center Hill, Grove Park in northwest Atlanta, and white sections of Edgewood Edgewood may refer to:

Places Canada

*Edgewood, British Columbia

South Africa

*Edgewood, a University of KwaZulu-Natal campus in Pinetown, South Africa

United States Cities and towns

*Edgewood, California

*Edgewood, Florida

*Edgewood, Illinois, a ...

and Kirkwood on the east side. In 1961, the city attempted to thwart blockbusting by erecting road barriers in Cascade Heights, countering the efforts of civic and business leaders to foster Atlanta as the "city too busy to hate".White flight

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They refer ...

and the building of malls in the suburbs triggered a slow decline of the central business district. Meanwhile, conservatism grew rapidly in the suburbs, and white Georgians were increasingly willing to vote for Republicans, most notably Newt Gingrich.

Civil Rights Movement

In the wake of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'', which helped usher in the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

, racial tensions in Atlanta erupted in acts of violence. One such instance occurred on October 12, 1958, when a Reform Jewish temple on Peachtree Street was bombed. A group of white supremacists

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

calling themselves the "Confederate Underground" claimed responsibility. The temple's leader, Rabbi Jacob Rothschild, actively spoke out in support of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement and against segregation, which is likely why the congregation was targeted.

In January 1956, Bobby Grier became the first black player to participate in the Sugar Bowl. He is also regarded as the first black player to compete at a bowl game in the Deep South, though others such as Wallace Triplett had played in games like the 1948 Cotton Bowl in Dallas. Grier's team, the Pittsburgh Panthers, was set to play against the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets. However, Georgia's Governor Marvin Griffin beseeched Georgia Tech's president Blake Van Leer and it's players to not participate in this racially integrated game. Griffin was widely criticized by news media leading up to the game, and protests were held at his mansion by Georgia Tech students. After delivering a commencement speech at the all-Black Morris Brown College, Van Leer was summoned by the board of regents where he was quoted . Despite the governor's objections, Georgia Tech upheld the contract and proceeded to compete in the bowl. In the game's first quarter, a pass interference call against Grier ultimately resulted in Yellow Jackets' 7-0 victory. Grier stated that he has mostly positive memories about the experience, including the support from teammates and letters from all over the world.

In the 1960s, Atlanta was a major organizing center of the Civil Rights Movement, with Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, and students from Atlanta's historically black colleges and universities playing major roles in the movement's leadership. On October 19, 1960, a sit-in at the lunch counters of several Atlanta department stores led to the arrest of Dr. King and several students. This drew attention from the national media and from presidential candidate John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

.

Despite this incident, Atlanta's political and business leaders fostered Atlanta's image as "the city too busy to hate". While the city mostly avoided confrontation, minor race riots did occur in 1965 and 1968.

Desegregation

Desegregation of the public sphere came in stages, with buses and trolleybuses desegregated in 1959, restaurants at Rich's department store in 1961, (though Lester Maddox

Lester Garfield Maddox Sr. (September 30, 1915 – June 25, 2003) was an American politician who served as the 75th governor of the U.S. state of Georgia from 1967 to 1971. A populist Democrat, Maddox came to prominence as a staunch segregatio ...

's Pickrick restaurant famously remained segregated through 1964), and movie theaters in 1962–3. While in 1961, Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. became one of the few Southern white mayors to support desegregation of his city's public schools, initial compliance was token, and in reality desegregation occurred in stages from 1961 to 1973.

1962 air crash and influence on art scene

In 1962, Atlanta in general and its arts community in particular were shaken by the deaths of 106 people on Air France

Air France (; formally ''Société Air France, S.A.''), stylised as AIRFRANCE, is the flag carrier of France headquartered in Tremblay-en-France. It is a subsidiary of the Air France–KLM Group and a founding member of the SkyTeam global a ...

charter flight 007, which crashed. The Atlanta Art Association had sponsored a month-long tour of the art treasures of Europe. 106[Morris, Mike]

"Air France crash recalls '62 Orly tragedy"

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the only major daily newspaper in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger between ...

''. Tuesday June 2, 2009. Retrieved on June 2, 2009. of the tour members were heading home to Atlanta on the flight. The group included many of Atlanta's cultural and civic leaders. Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr. went to Orly, France, to inspect the crash site where so many important Atlantans perished. The loss was a catalyst for the arts in Atlanta and helped create the Woodruff Arts Center

Woodruff Arts Center is a visual and performing arts center located in Atlanta, Georgia. The center houses three not-for-profit arts divisions on one campus. Opened in 1968, the Woodruff Arts Center is home to the Alliance Theatre, the Atlant ...

, originally called the Memorial Arts Center, as a tribute to the victims, and led to the creation of the Atlanta Arts Alliance. The French government donated a Rodin sculpture, '' The Shade'', to the High in memory of the victims of the crash.Harry Belafonte

Harry Belafonte (born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.; March 1, 1927) is an American singer, activist, and actor. As arguably the most successful Jamaican-American pop star, he popularized the Trinbagonian Caribbean musical style with an interna ...

announced cancellation of a sit-in in downtown Atlanta as a conciliatory gesture to the grieving city, while Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

gained widespread national attention for the first time by expressing joy over the deaths of the all-white group.

Freeway construction and revolts

Atlanta's freeway system was completed in the 1950s and 1960s, with the Perimeter

A perimeter is a closed path that encompasses, surrounds, or outlines either a two dimensional shape or a one-dimensional length. The perimeter of a circle or an ellipse is called its circumference.

Calculating the perimeter has several pr ...

completed in 1969. Historic neighborhoods such as Washington-Rawson and Copenhill

Copenhill, Copenhill Park, or Copen Hill was a neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia which was located largely where the Carter Center now sits, and which now forms part of the Poncey-Highland neighborhood.

History

Copen Hill (as it was origina ...

were damaged or destroyed in the process. Additional proposed freeways were never built due to the protests of city residents. The opposition lasted three decades, with then-governor Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1 ...

playing a key role in stopping I-485 through Morningside and Virginia Highland

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

to Inman Park in 1973, but pushing hard in the 1980s for a "Presidential Parkway" between downtown, the new Carter Center

The Carter Center is a nongovernmental, not-for-profit organization founded in 1982 by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter. He and his wife Rosalynn Carter partnered with Emory University just after his defeat in the 1980 United States presid ...

, and Druid Hills/ Emory.

Urban renewal

In the 1960s, slums such as Buttermilk Bottom near today's Civic Center were razed, in principle to build better housing, but much of the land remained empty until the 1980s, when mixed-income communities were built in what was renamed Bedford Pine. The African-American community east of downtown suffered as the center of the black economy moved squarely to southwestern Atlanta. During the 1960s, African-American citizens'-rights groups such as U-Rescue emerged to address the lack of housing for poor black people.

Shoppers move to new malls as Downtown gains new roles

The first major mall built in Atlanta was Lenox Square in Buckhead, opening in August 1959. From 1964 until 1973, nine major malls opened, most at the Perimeter freeway: Cobb Center in 1963, Avondale Mall, Columbia Mall in 1964, North DeKalb Mall, North DeKalb and Greenbriar Mall, Greenbriar malls in 1965, Gallery at South DeKalb, South DeKalb Mall in 1968, Phipps Plaza (near Lenox Square) in 1969, Perimeter Mall, Perimeter and Northlake Mall (Atlanta), Northlake malls in 1971, and Cumberland Mall (Georgia), Cumberland Mall in 1973. Downtown Atlanta became less and less a shopping destination for the area's shoppers. Rich's closed its flagship store downtown in 1991, leaving government offices the major presence in the South Downtown area around it.

On the north side of Five Points, Downtown continued as the Downtown Atlanta#Buildings, largest concentration of office space in Metro Atlanta, though it began to compete with Midtown, Buckhead, and the suburbs. The first four towers of Peachtree Center were built in 1965–1967, including the Hyatt Regency Atlanta, designed by John Portman, with its 22-story atrium. In total, 17 buildings of more than 15n floors were built in the 1960s. The center of gravity of Downtown Atlanta correspondingly moved north from the Five Points area towards Peachtree Center.

Atlanta's convention and hotel facilities also grew immensely. John C. Portman, Jr. designed and opened what is now the AmericasMart merchandise mart in 1958; the Sheraton Atlanta, the city's first convention hotel, was built in the 1960s; the Atlanta Hilton opened in 1971; as did two Portman-designed hotels: the Peachtree Plaza Hotel now owned by Westin Peachtree Plaza Hotel, Westin in 1976, and the Atlanta Marriott Marquis, Marriott in 1985. The Omni Coliseum opened in 1976, as did the Georgia World Congress Center

The Georgia World Congress Center (GWCC) is a convention center in Atlanta, Georgia. Enclosing some 3.9 million ft2 (360,000 m2) in exhibition space and hosting more than a million visitors each year, the GWCC is the world's largest LEED certi ...

(GWCC). The GWCC expanded multiple times in succeeding decades and helped make Atlanta one of the country's top convention cities.

Black political power and Mayor Jackson

In 1960, whites comprised 61.7% of the city's population. African Americans became a majority in the city by 1970, and exercised new-found political influence by electing Atlanta's first black mayor, Maynard Jackson

Maynard Holbrook Jackson Jr. (March 23, 1938 – June 23, 2003) was an American politician and attorney from Georgia. A member of the Democratic Party, he was elected in 1973 at the age of 35 as the first black mayor of Atlanta, Georgia and of ...

, in 1973.

During Jackson's first term as the mayor, much progress was made in improving race relations in and around Atlanta, and Atlanta acquired the motto "A City Too Busy to Hate". As mayor, he led the beginnings and much of the progress on several huge public-works projects in Atlanta and its region. He helped arrange for the rebuilding of the airport's huge terminal to modern standards, and this airport was renamed the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in his honor shortly after his death, also named after him is the new Maynard Holbrook Jackson, Jr. International Terminal which opened in May 2012. He also Atlanta freeway revolts, fought against the construction of freeways through intown neighborhoods.

Construction of MARTA rail system

In 1965, an act of the Georgia General Assembly created the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, or MARTA, which was to provide rapid transit for the five largest metropolitan counties:

In 1965, an act of the Georgia General Assembly created the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, or MARTA, which was to provide rapid transit for the five largest metropolitan counties: DeKalb DeKalb or De Kalb may refer to:

People

* Baron Johann de Kalb (1721–1780), major general in the American Revolutionary War

Places Municipalities in the United States

* DeKalb, Illinois, the largest city in the United States named DeKalb

**DeKal ...

, Fulton, Clayton County, Georgia, Clayton, Gwinnett County, Georgia, Gwinnett, and Cobb County, Georgia, Cobb, but a referendum authorizing participation in the system failed in Cobb County. A 1968 referendum to fund MARTA failed, but in 1971, Fulton and DeKalb Counties passed a 1% sales tax increase to pay for operations, while Clayton and Gwinnett counties overwhelmingly rejected the tax in referendum, fearing the introduction of crime and "undesirable elements".[ A line originally envisioned to run to ]Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

is Clifton Corridor, still under consideration.

Child murders

Atlanta was rocked by a Atlanta murders of 1979–1981, series of murders of children from the summer of 1979 until the spring of 1981. Over the two-year period, at least 22 children, and 6 adults were killed, all of them black. Atlanta native Wayne Williams, also black and 23 years old at the time of the last murder, was convicted of two of the murders and sent to prison for life. The rest of the crimes remain unsolved today.

Mayor Andrew Young

In 1981, after being urged by a number of people, including Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King Jr., Democratic Congressman Andrew Young ran for mayor of Atlanta. He was elected later that year with 55% of the vote, succeeding Maynard Jackson

Maynard Holbrook Jackson Jr. (March 23, 1938 – June 23, 2003) was an American politician and attorney from Georgia. A member of the Democratic Party, he was elected in 1973 at the age of 35 as the first black mayor of Atlanta, Georgia and of ...

. As mayor of Atlanta, he brought in $70 billion of new private investment. He continued and expanded Maynard Jackson's programs for including minority and female-owned businesses in all city contracts. The Mayor's Task Force on Education established the Dream Jamboree College Fair that tripled the college scholarships given to Atlanta public school graduates. In 1985, he was involved in privatizing the Atlanta Zoo, which was renamed Zoo Atlanta. The then-moribund zoo was overhauled, making ecological habitats specific to different animals.

Young was re-elected as Mayor in 1985 with more than 80% of the vote. Atlanta hosted the 1988 Democratic National Convention during Young's tenure. He was prohibited by term limits from running for a third term. He was succeeded by Maynard Jackson who returned as mayor from 1990 to 1994. Bill Campbell (mayor), Bill Campbell succeeded Jackson as mayor in 1994 and served through 2002.

Campbell mayorship and failure of Atlanta Empowerment Zone

In November 1994, the Atlanta Empowerment Zone was established, a 10-year, $250 million federal program to revitalize Atlanta's 34 poorest neighborhoods including The Bluff (Atlanta), The Bluff. Scathing reports from both the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Georgia Department of Community Affairs revealed corruption, waste, bureaucratic incompetence, and specifically called out interference by mayor Bill Campbell (mayor), Bill Campbell.[Scott Henry, "Federal grants go to groups with shaky past", ''Creative Loafing'', September 26, 2007]

/ref>

In 1993-1996 about 250,000 people attended Freaknik, an annual Spring Break gathering for African Americans which was not centrally organized and which resulted in much traffic gridlock and increased crime. After a 1996 crackdown annual attendance dissipated and the event moved to other cities.

Olympic and World City: 1990present

1996 Summer Olympics

In 1990, the International Olympic Committee selected Atlanta as the site for the Centennial Olympic Games 1996 Summer Olympics. Following the announcement, Atlanta undertook several major construction projects to improve the city's parks, sports facilities, and transportation, including the completion of long-contested Freedom Parkway. Former Mayor Bill Campbell (mayor), Bill Campbell allowed many "tent cities" to be built, creating a carnival atmosphere around the games. Atlanta became the third American city to host the Summer Olympics, after St. Louis, Missouri, St. Louis (1904 Summer Olympics) and Los Angeles (1932 Summer Olympics, 1932 and 1984 Summer Olympics, 1984). The games themselves were notable in the realm of sporting events, but they were marred by numerous organizational inefficiencies. A dramatic event was the Centennial Olympic Park bombing, in which two people died, one from a heart attack, and several others were injured. Eric Robert Rudolph was later convicted of the bombing as an anti-government and pro-life protest.