Marco Polo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a

Marco Polo was born in 1254 in

Marco Polo was born in 1254 in

online copy pp. 24–25

Some old Venetian historical sources considered Polo's ancestors to be of far

Marco Polo is most often mentioned in the archives of the Republic of Venice as , which means Marco Polo of the of St John Chrysostom Church.

However, he was also nicknamed during his lifetime (which in Italian literally means 'Million'). In fact, the Italian title of his book was , which means "The Book of Marco Polo, nicknamed '. According to the 15th-century humanist Giovanni Battista Ramusio, his fellow citizens awarded him this nickname when he came back to Venice because he kept on saying that Kublai Khan's wealth was counted in millions. More precisely, he was nicknamed (Mr Marco Millions).

However, since also his father Niccolò was nicknamed , 19th-century philologist Luigi Foscolo Benedetto was persuaded that was a shortened version of , and that this nickname was used to distinguish Niccolò's and Marco's branch from other Polo families. ( Ranieri Allulli, ''MARCO POLO E IL LIBRO DELLE MERAVIGLIE – Dialogo in tre tempi del giornalista Qualunquelli Junior e dell'astrologo Barbaverde'', Milano, Mondadori, 1954, p.26)

Marco Polo is most often mentioned in the archives of the Republic of Venice as , which means Marco Polo of the of St John Chrysostom Church.

However, he was also nicknamed during his lifetime (which in Italian literally means 'Million'). In fact, the Italian title of his book was , which means "The Book of Marco Polo, nicknamed '. According to the 15th-century humanist Giovanni Battista Ramusio, his fellow citizens awarded him this nickname when he came back to Venice because he kept on saying that Kublai Khan's wealth was counted in millions. More precisely, he was nicknamed (Mr Marco Millions).

However, since also his father Niccolò was nicknamed , 19th-century philologist Luigi Foscolo Benedetto was persuaded that was a shortened version of , and that this nickname was used to distinguish Niccolò's and Marco's branch from other Polo families. ( Ranieri Allulli, ''MARCO POLO E IL LIBRO DELLE MERAVIGLIE – Dialogo in tre tempi del giornalista Qualunquelli Junior e dell'astrologo Barbaverde'', Milano, Mondadori, 1954, p.26)

In 1168, his great-uncle, Marco Polo, borrowed money and commanded a ship in Constantinople. His grandfather, Andrea Polo of the parish of San Felice, had three sons, Maffeo, yet another Marco, and the traveller's father Niccolò. This genealogy, described by Ramusio, is not universally accepted as there is no additional evidence to support it.

His father, Niccolò Polo, a merchant, traded with the

In 1168, his great-uncle, Marco Polo, borrowed money and commanded a ship in Constantinople. His grandfather, Andrea Polo of the parish of San Felice, had three sons, Maffeo, yet another Marco, and the traveller's father Niccolò. This genealogy, described by Ramusio, is not universally accepted as there is no additional evidence to support it.

His father, Niccolò Polo, a merchant, traded with the

di Michele T. Mazzucato In 1260, Niccolò and Maffeo, while residing in Constantinople, then the capital of the

In 1323, Polo was confined to bed, due to illness. On 8 January 1324, despite physicians' efforts to treat him, Polo was on his deathbed. To write and certify the will, his family requested Giovanni Giustiniani, a priest of San Procolo. His wife, Donata, and his three daughters were appointed by him as co-executrices. The church was entitled by law to a portion of his estate; he approved of this and ordered that a further sum be paid to the convent of San Lorenzo, the place where he wished to be buried. He also set free Peter, a

In 1323, Polo was confined to bed, due to illness. On 8 January 1324, despite physicians' efforts to treat him, Polo was on his deathbed. To write and certify the will, his family requested Giovanni Giustiniani, a priest of San Procolo. His wife, Donata, and his three daughters were appointed by him as co-executrices. The church was entitled by law to a portion of his estate; he approved of this and ordered that a further sum be paid to the convent of San Lorenzo, the place where he wished to be buried. He also set free Peter, a

Venezia.sbn.it

Due to the Venetian law stating that the day ends at sunset, the exact date of Marco Polo's death cannot be determined, but according to some scholars it was between the sunsets of 8 and 9 January 1324. Biblioteca Marciana, which holds the original copy of his testament, dates the testament on 9 January 1323, and gives the date of his death at some time in June 1324.

The book opens with a preface describing his father and uncle travelling to

The book opens with a preface describing his father and uncle travelling to  In 1271, Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo embarked on their voyage to fulfil Kublai's request. They sailed to

In 1271, Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo embarked on their voyage to fulfil Kublai's request. They sailed to

Since its publication, some have viewed the book with skepticism. Some in the Middle Ages regarded the book simply as a romance or fable, due largely to the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck, who portrayed the Mongols as '

Since its publication, some have viewed the book with skepticism. Some in the Middle Ages regarded the book simply as a romance or fable, due largely to the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck, who portrayed the Mongols as '

Other lesser-known European explorers had already travelled to China, such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, but Polo's book meant that his journey was the first to be widely known.

Other lesser-known European explorers had already travelled to China, such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, but Polo's book meant that his journey was the first to be widely known.

The Marco Polo sheep, a subspecies of ''

The Marco Polo sheep, a subspecies of ''

Marco Polo, ''Marci Poli Veneti de Regionibus Orientalibus'', Simon Grynaeus Johannes Huttichius, ''Novus Orbis Regionum ac Insularum Veteribus Incognitarum,'' Basel, 1532, pp. 350–418.

* * * * * * (Article republished in 2006 World Almanac Books, available online fro

History.com

* * * * * Olivier Weber, ''Le grand festin de l'Orient''; Robert Laffont, 2004 * * * * * * * * * Marco Polo. (2010). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-08-28, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

Marco Polo , Biography, Travels, & Influence

*

Marco Polo

on IMDb

Marco Polo's house in Venice, near the church of San Giovanni Grisostomo

* * *

Marco Polo's Orient

Film on the material culture of areas along Polo's route using objects from the collections of the Glasgow Museums {{DEFAULTSORT:Polo, Marco Marco Polo, 1254 births 1324 deaths 13th-century explorers 13th-century Venetian writers Explorers of Asia Explorers of Central Asia Explorers from the Republic of Venice Medieval travel writers Republic of Venice merchants Venetian expatriates in China Venetian male writers Venetian Roman Catholics Venetian travel writers 14th-century Venetian writers People of the War of Curzola

Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

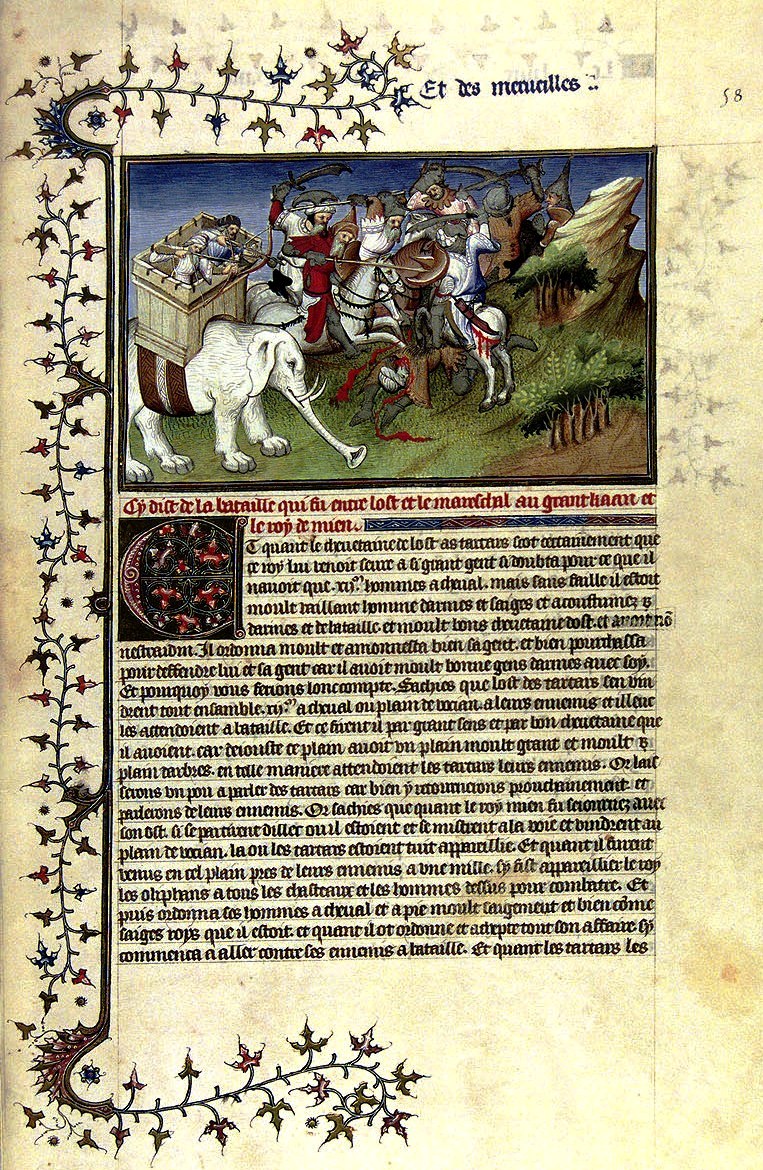

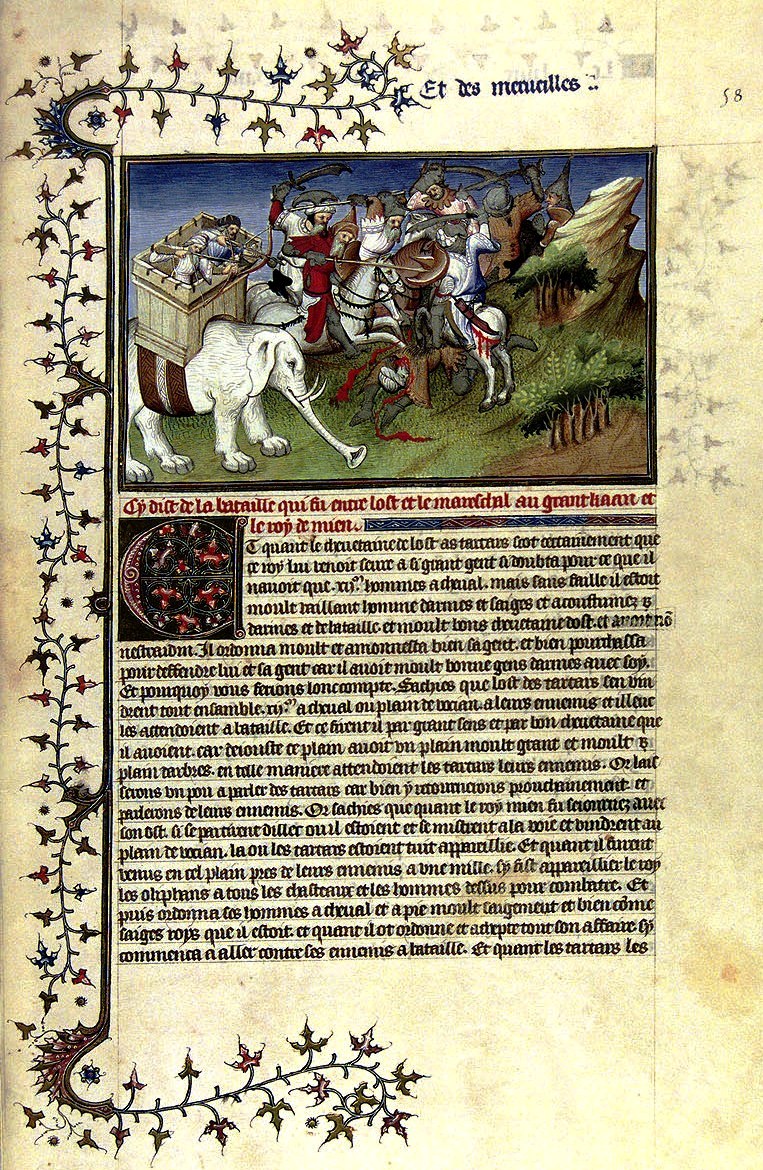

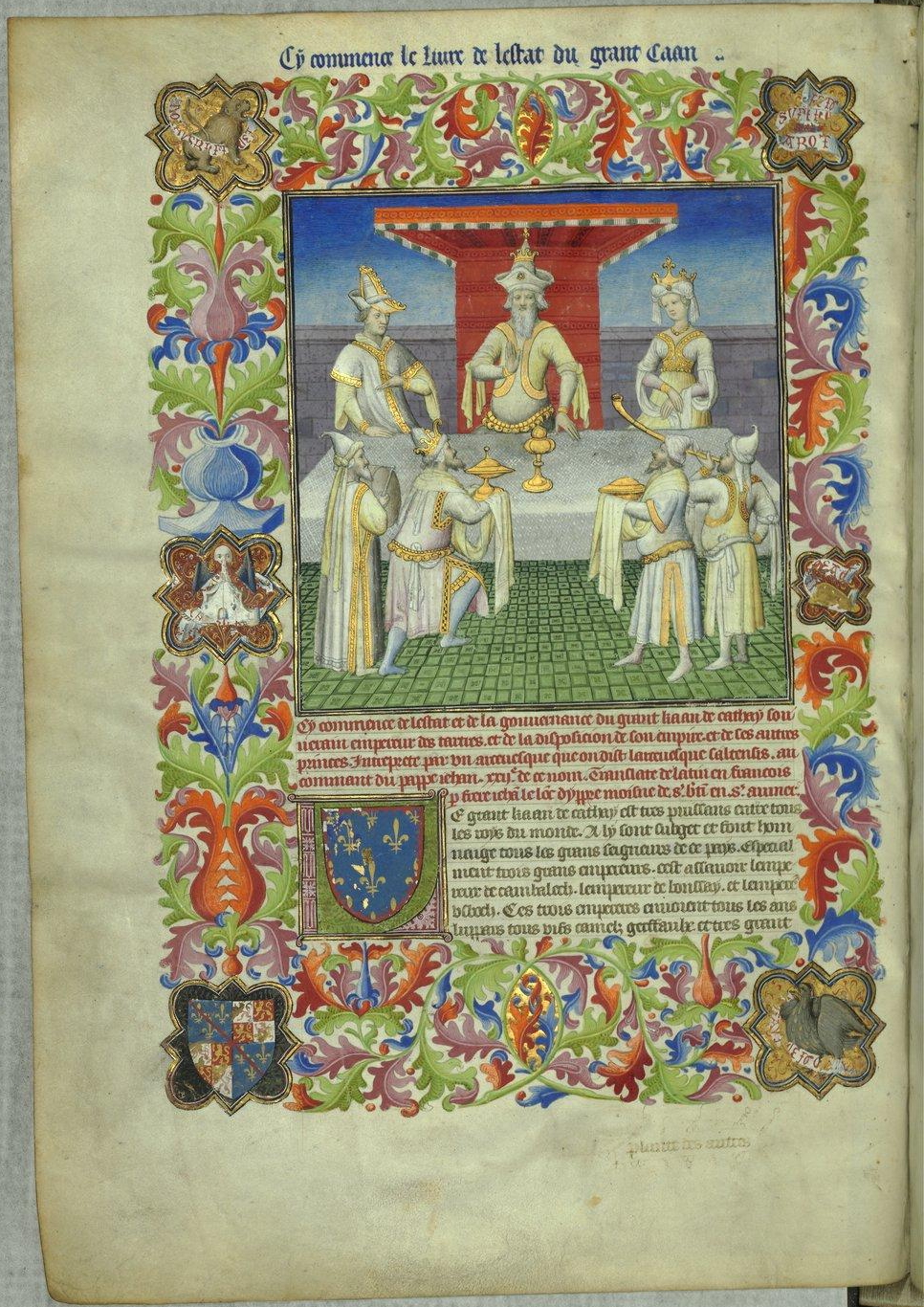

between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marvels of the World '' and ''Il Milione'', ), a book that described to Europeans the then mysterious culture and inner workings of the Eastern world, including the wealth and great size of the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

and China in the Yuan Dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

, giving their first comprehensive look into China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

and other Asian cities and countries.

Born in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, Marco learned the mercantile trade from his father and his uncle, Niccolò and Maffeo, who travelled through Asia and met Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

. In 1269, they returned to Venice to meet Marco for the first time. The three of them embarked on an epic journey to Asia, exploring many places along the Silk Road until they reached Cathay

Cathay (; ) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term ''Cathay'' initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from China, which ...

(China). They were received by the royal court of Kublai Khan, who was impressed by Marco's intelligence and humility. Marco was appointed to serve as Khan's foreign emissary, and he was sent on many diplomatic mission

A diplomatic mission or foreign mission is a group of people from a state or organization present in another state to represent the sending state or organization officially in the receiving or host state. In practice, the phrase usually den ...

s throughout the empire and Southeast Asia, such as in present-day Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

. As part of this appointment, Marco also travelled extensively inside China, living in the emperor's lands for 17 years and seeing many things that had previously been unknown to Europeans. Around 1291, the Polos also offered to accompany the Mongol princess Kököchin to Persia; they arrived around 1293. After leaving the princess, they travelled overland to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

and then to Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, returning home after 24 years. At this time, Venice was at war with Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

; Marco was captured and imprisoned by the Genoans after joining the war effort and dictated his stories to Rustichello da Pisa, a cellmate. He was released in 1299, became a wealthy merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as indust ...

, married, and had three children. He died in 1324 and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Venice.

Though he was not the first European to reach China (see Europeans in Medieval China), Marco Polo was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experience. This account of the Orient provided the Europeans with a clear picture of the East's geography and ethnic customs, and was the first Western record of porcelain, gunpowder, paper money, and some Asian plants and exotic animals. His travel book inspired Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

and many other travellers. There is substantial literature based on Polo's writings; he also influenced European cartography

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an i ...

, leading to the introduction of the Fra Mauro map.

Life

Birthplace and family origin

Marco Polo was born in 1254 in

Marco Polo was born in 1254 in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, the capital of the Venetian Republic

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

. His father, Niccolò Polo, had his household in Venice and left Marco's pregnant mother in order to travel to Asia with his brother Maffeo Polo

Maffeo is a given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

*Maffeo Barberini (1568–1644), reigned as Pope Urban VIII from 1623 to his death in 1644

*Maffeo Barberini (1631–1685), Italian nobleman of the Barberini, P ...

. Their return to Italy in order to "go to Venice and visit their household" is described in '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' as follows: "...they departed from Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

and went to Negropont, and from Negropont they continued their voyage to Venice. On their arrival there, Messer Nicolas found that his wife was dead and that she had left behind her a son of fifteen years of age, whose name was Marco".

His first known ancestor was a great uncle, Marco Polo (the older) from Venice, who lent some money and commanded a ship in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. Andrea, Marco's grandfather, lived in Venice in " contrada San Felice", he had three sons: Marco "the older", Maffeo and Niccolò (Marco's father).online copy pp. 24–25

Some old Venetian historical sources considered Polo's ancestors to be of far

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

n origin.

Nickname

Early life and Asian travel

In 1168, his great-uncle, Marco Polo, borrowed money and commanded a ship in Constantinople. His grandfather, Andrea Polo of the parish of San Felice, had three sons, Maffeo, yet another Marco, and the traveller's father Niccolò. This genealogy, described by Ramusio, is not universally accepted as there is no additional evidence to support it.

His father, Niccolò Polo, a merchant, traded with the

In 1168, his great-uncle, Marco Polo, borrowed money and commanded a ship in Constantinople. His grandfather, Andrea Polo of the parish of San Felice, had three sons, Maffeo, yet another Marco, and the traveller's father Niccolò. This genealogy, described by Ramusio, is not universally accepted as there is no additional evidence to support it.

His father, Niccolò Polo, a merchant, traded with the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

, becoming wealthy and achieving great prestige. Niccolò and his brother Maffeo set off on a trading voyage before Marco's birth.Italiani nel sistema solaredi Michele T. Mazzucato In 1260, Niccolò and Maffeo, while residing in Constantinople, then the capital of the

Latin Empire

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byza ...

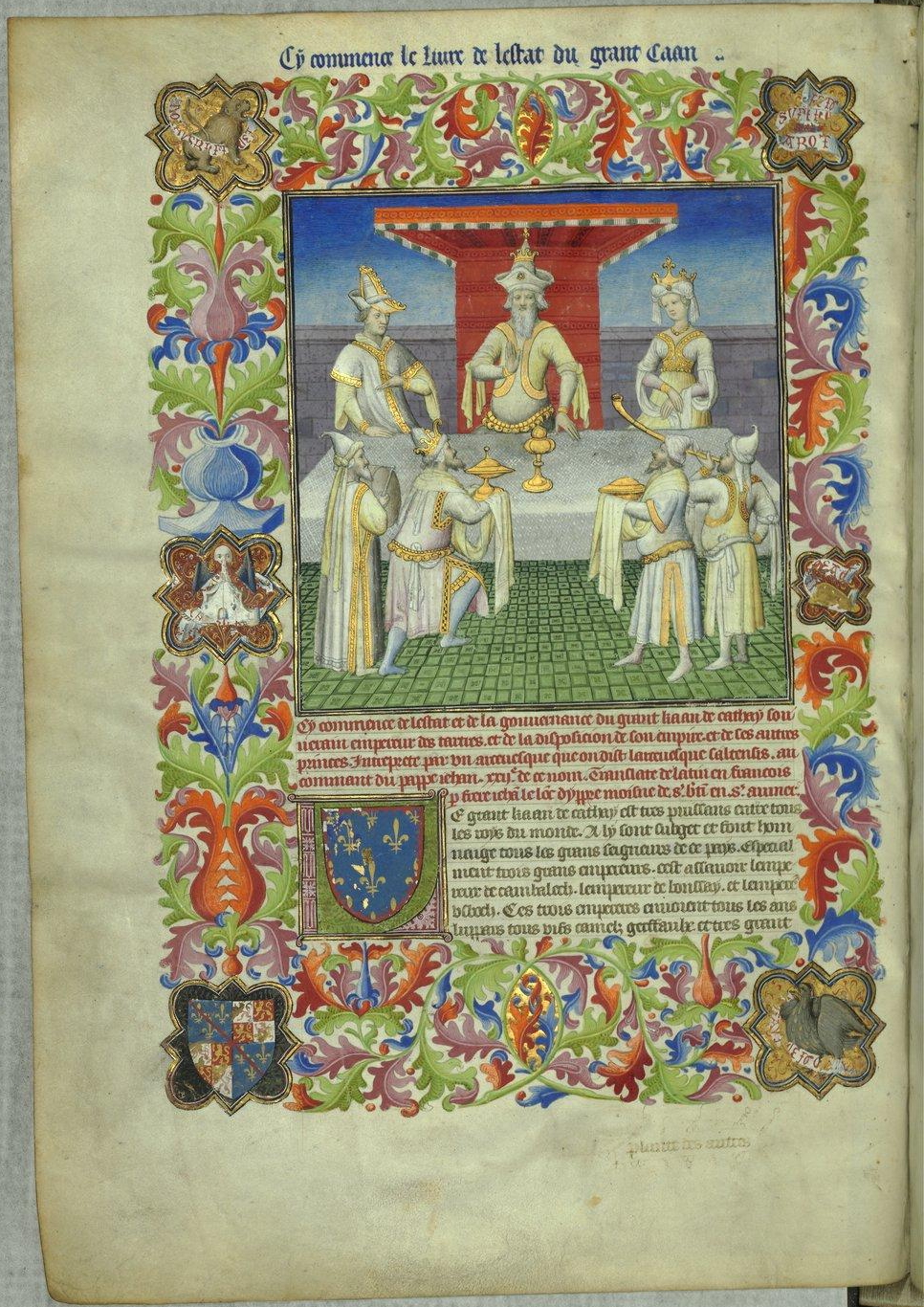

, foresaw a political change; they liquidated their assets into jewels and moved away. According to ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', they passed through much of Asia, and met with Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

, a Mongol ruler and founder of the Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

. Their decision to leave Constantinople proved timely. In 1261 Michael VIII Palaiologos

Michael VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Μιχαὴλ Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος, Mikhaēl Doukas Angelos Komnēnos Palaiologos; 1224 – 11 December 1282) reigned as the co-emperor of the Empire ...

, the ruler of the Empire of Nicaea

The Empire of Nicaea or the Nicene Empire is the conventional historiographic name for the largest of the three Byzantine Greek''A Short history of Greece from early times to 1964'' by W. A. Heurtley, H. C. Darby, C. W. Crawley, C. M. Woodhous ...

, took Constantinople, promptly burned the Venetian quarter and re-established the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. Captured Venetian citizens were blinded, while many of those who managed to escape perished aboard overloaded refugee ships fleeing to other Venetian colonies in the Aegean Sea.

Almost nothing is known about the childhood of Marco Polo until he was fifteen years old, except that he probably spent part of his childhood in Venice. Meanwhile, Marco Polo's mother died, and an aunt and uncle raised him. He received a good education, learning mercantile subjects including foreign currency, appraising, and the handling of cargo ships; he learned little or no Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

. His father later married Floradise Polo (née Trevisan).

In 1269, Niccolò and Maffeo returned to their families in Venice, meeting young Marco for the first time. In 1271, during the rule of Doge Lorenzo Tiepolo, Marco Polo (at seventeen years of age), his father, and his uncle set off for Asia on the series of adventures that Marco later documented in his book.

They sailed to Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

and later rode on their camels to the Persian port Hormuz. During the first stages of the journey, they stayed for a few months in Acre and were able to speak with Archdeacon Tedaldo Visconti of Piacenza. The Polo family, on that occasion, had expressed their regret at the long lack of a pope, because on their previous trip to China they had received a letter from Kublai Khan to the Pope, and had thus had to leave for China disappointed. During the trip, however, they received news that after 33 months of vacation, finally, the Conclave had elected the new Pope and that he was exactly the archdeacon of Acre. The three of them hurried to return to the Holy Land, where the new Pope entrusted them with letters for the "Great Khan", inviting him to send his emissaries to Rome. To give more weight to this mission he sent with the Polos, as his legates, two Dominican fathers, Guglielmo of Tripoli and Nicola of Piacenza.

They continued overland until they arrived at Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

's place in Shangdu, China (then known as Cathay

Cathay (; ) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term ''Cathay'' initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from China, which ...

). By this time, Marco was 21 years old. Impressed by Marco's intelligence and humility, Khan appointed him to serve as his foreign emissary to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

. He was sent on many diplomatic missions throughout his empire and in Southeast Asia, (such as in present-day Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

), but also entertained the Khan with stories and observations about the lands he saw. As part of this appointment, Marco travelled extensively inside China, living in the emperor's lands for 17 years.

Kublai initially refused several times to let the Polos return to Europe, as he appreciated their company and they became useful to him. However, around 1291, he finally granted permission, entrusting the Polos with his last duty: accompany the Mongol princess Kököchin, who was to become the consort of Arghun Khan, in Persia (see ''Narrative

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether nonfictional ( memoir, biography, news report, documentary, travelogue, etc.) or fictional ( fairy tale, fable, legend, thriller, novel, etc ...

'' section). After leaving the princess, the Polos travelled overland to Constantinople. They later decided to return to their home.

They returned to Venice in 1295, after 24 years, with many riches and treasures. They had travelled almost .

Genoese captivity and later life

Marco Polo returned to Venice in 1295 with his fortune converted intogemstone

A gemstone (also called a fine gem, jewel, precious stone, or semiprecious stone) is a piece of mineral crystal which, in cut and polished form, is used to make jewelry or other adornments. However, certain rocks (such as lapis lazuli, opal, ...

s. At this time, Venice was at war with the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the La ...

.Nicol 1992, p. 219 Polo armed a galley equipped with a trebuchetYule, ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', London, 1870: reprinted by Dover, New York, 1983. to join the war. He was probably caught by Genoans in a skirmish in 1296, off the Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

n coast between Adana

Adana (; ; ) is a major city in southern Turkey. It is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The administrative seat of Adana province, it has a population of 2.26 million.

Adana lies in the heart of Cilicia, wh ...

and the Gulf of Alexandretta (and not during the battle of Curzola

The Battle of Curzola (today Korčula, southern Dalmatia, now in Croatia) was a naval battle fought on 9 September 1298 between the Genoese and Venetian navies. It was a disaster for Venice, a major setback among the many battles fought in the ...

(September 1298), off the Dalmatian coast, a claim which is due to a later tradition (16th century) recorded by Giovanni Battista Ramusio).

He spent several months of his imprisonment dictating a detailed account of his travels to a fellow inmate, Rustichello da Pisa, who incorporated tales of his own as well as other collected anecdotes and current affairs from China. The book soon spread throughout Europe in manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced i ...

form, and became known as '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' ( Italian title: ''Il Milione'', lit. "The Million", deriving from Polo's nickname "Milione". Original title in Franco-Italian : ''Livres des Merveilles du Monde''). It depicts the Polos' journeys throughout Asia, giving Europeans their first comprehensive look into the inner workings of the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The t ...

, including China, India, and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

.

Polo was finally released from captivity in August 1299, and returned home to Venice, where his father and uncle in the meantime had purchased a large palazzo in the zone named ''contrada San Giovanni Crisostomo'' (Corte del Milion). For such a venture, the Polo family probably invested profits from trading, and even many gemstones they brought from the East. The company continued its activities and Marco soon became a wealthy merchant. Marco and his uncle Maffeo financed other expeditions, but likely never left Venetian provinces, nor returned to the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

and Asia. Sometime before 1300, his father Niccolò died. In 1300, he married Donata Badoèr, the daughter of Vitale Badoèr, a merchant. They had three daughters, Fantina (married Marco Bragadin), Bellela (married Bertuccio Querini), and Moreta.

Pietro d'Abano philosopher, doctor and astrologer based in Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, reports having spoken with Marco Polo about what he had observed in the vault of the sky during his travels. Marco told him that during his return trip to the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by the shores of South China (hence the name), in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Ph ...

, he had spotted what he describes in a drawing as a star "shaped like a sack" (in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

: ''ut sacco'') with a big tail (''magna habens caudam''), most likely a comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena ...

. Astronomers agree that there were no comets sighted in Europe at the end of the thirteenth century, but there are records about a comet sighted in China and Indonesia in 1293. Interestingly, this circumstance does not appear in Polo's book of Travels. Peter D'Abano kept the drawing in his volume "Conciliator Differentiarum, quæ inter Philosophos et Medicos Versantur". Marco Polo gave Pietro other astronomical observations he made in the Southern Hemisphere, and also a description of the Sumatran rhinoceros, which are collected in the ''Conciliator''.

In 1305 he is mentioned in a Venetian document among local sea captains regarding the payment of taxes. His relation with a certain Marco Polo, who in 1300 was mentioned with riots against the aristocratic government, and escaped the death penalty, as well as riots from 1310 led by Bajamonte Tiepolo and Marco Querini, among whose rebels were Jacobello and Francesco Polo from another family branch, is unclear. Polo is clearly mentioned again after 1305 in Maffeo's testament from 1309 to 1310, in a 1319 document according to which he became owner of some estates of his deceased father, and in 1321, when he bought part of the family property of his wife Donata.

Death

In 1323, Polo was confined to bed, due to illness. On 8 January 1324, despite physicians' efforts to treat him, Polo was on his deathbed. To write and certify the will, his family requested Giovanni Giustiniani, a priest of San Procolo. His wife, Donata, and his three daughters were appointed by him as co-executrices. The church was entitled by law to a portion of his estate; he approved of this and ordered that a further sum be paid to the convent of San Lorenzo, the place where he wished to be buried. He also set free Peter, a

In 1323, Polo was confined to bed, due to illness. On 8 January 1324, despite physicians' efforts to treat him, Polo was on his deathbed. To write and certify the will, his family requested Giovanni Giustiniani, a priest of San Procolo. His wife, Donata, and his three daughters were appointed by him as co-executrices. The church was entitled by law to a portion of his estate; he approved of this and ordered that a further sum be paid to the convent of San Lorenzo, the place where he wished to be buried. He also set free Peter, a Tartar

Tartar may refer to:

Places

* Tartar (river), a river in Azerbaijan

* Tartar, Switzerland, a village in the Grisons

* Tərtər, capital of Tartar District, Azerbaijan

* Tartar District, Azerbaijan

* Tartar Island, South Shetland Islands, A ...

servant, who may have accompanied him from Asia, and to whom Polo bequeathed 100 lire of Venetian denari.

He divided up the rest of his assets, including several properties, among individuals, religious institutions, and every guild and fraternity to which he belonged. He also wrote off multiple debts including 300 lire that his sister-in-law owed him, and others for the convent of San Giovanni, San Paolo of the Order of Preachers, and a cleric named Friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ...

Benvenuto. He ordered 220 soldi

"Soldi" (; ) is a song recorded by Italian singer Mahmood. It was released on 6 February 2019, as the fifth single from his debut studio album, '' Gioventù bruciata'' (2019). Mahmood co-wrote the song with Dario "Dardust" Faini and Charlie C ...

be paid to Giovanni Giustiniani for his work as a notary and his prayers.

The will was not signed by Polo, but was validated by the then-relevant " signum manus" rule, by which the testator only had to touch the document to make it legally valid.Biblioteca Marciana, the institute that holds Polo's original copy of his testamentVenezia.sbn.it

Due to the Venetian law stating that the day ends at sunset, the exact date of Marco Polo's death cannot be determined, but according to some scholars it was between the sunsets of 8 and 9 January 1324. Biblioteca Marciana, which holds the original copy of his testament, dates the testament on 9 January 1323, and gives the date of his death at some time in June 1324.

''The Travels of Marco Polo''

An authoritative version of Marco Polo's book does not and cannot exist, for the early manuscripts differ significantly, and the reconstruction of the original text is a matter oftextual criticism

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and of literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts or of printed books. Such texts may range in da ...

. A total of about 150 copies in various languages are known to exist. Before the availability of printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

, errors were frequently made during copying and translating, so there are many differences between the various copies.

Polo related his memoirs orally to Rustichello da Pisa while both were prisoners of the Genova Republic. Rustichello wrote '' Devisement du Monde'' in Franco-Venetian.Maria Bellonci, "Nota introduttiva", Il Milione di Marco Polo, Milano, Oscar Mondadori, 2003, p. XI The idea probably was to create a handbook for merchants, essentially a text on weights, measures and distances.

The oldest surviving manuscript is in Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intel ...

heavily flavoured with Italian; According to the Italian scholar Luigi Foscolo Benedetto, this "F" text is the basic original text, which he corrected by comparing it with the somewhat more detailed Italian of Giovanni Battista Ramusio, together with a Latin manuscript in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana. Other early important sources are R (Ramusio's Italian translation first printed in 1559), and Z (a fifteenth-century Latin manuscript kept at Toledo, Spain). Another Old French Polo manuscript, dating to around 1350, is held by the National Library of Sweden.

One of the early manuscripts ''Iter Marci Pauli Veneti'' was a translation into Latin made by the Dominican brother in 1302, just a few years after Marco's return to Venice. Since Latin was then the most widespread and authoritative language of culture, it is suggested that Rustichello's text was translated into Latin for a precise will of the Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of ...

, and this helped to promote the book on a European scale.

The first English translation is the Elizabethan version by John Frampton published in 1579, ''The most noble and famous travels of Marco Polo'', based on Santaella's Castilian translation of 1503 (the first version in that language).

The published editions of Polo's book rely on single manuscripts, blend multiple versions together, or add notes to clarify, for example in the English translation by Henry Yule. The 1938 English translation by Moule and Paul Pelliot is based on a Latin manuscript found in the library of the Cathedral of Toledo

, native_name_lang =

, image = Toledo Cathedral, from Plaza del Ayuntamiento.jpg

, imagesize = 300px

, imagelink =

, imagealt =

, landscape =

, caption ...

in 1932, and is 50% longer than other versions. The popular translation published by Penguin Books in 1958 by Latham works several texts together to make a readable whole.

Narrative

Bolghar

Bolghar ( tt-Cyrl, Болгар, cv, Пăлхар) was intermittently the capital of Volga Bulgaria from the 8th to the 15th centuries, along with Bilyar and Nur-Suvar. It was situated on the bank of the Volga River, about 30 km downstrea ...

where Prince Berke Khan lived. A year later, they went to Ukek

Ukek or Uvek ( tt-Latn, Ükäk, russian: Увек) was a city of the Golden Horde, situated on the banks of the Volga River, at the ''Uvekovka'' estuary.

Ukek marked the half-way distance between Sarai, the capital of the Golden Horde, and Bo ...

and continued to Bukhara

Bukhara ( Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara for at least five millennia, and the city ...

. There, an envoy from the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

invited them to meet Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

, who had never met Europeans. In 1266, they reached the seat of Kublai Khan at Dadu, present-day Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

, China. Kublai received the brothers with hospitality and asked them many questions regarding the European legal and political system. He also inquired about the Pope and Church in Rome. After the brothers answered the questions he tasked them with delivering a letter to the Pope, requesting 100 Christians acquainted with the Seven Arts (grammar, rhetoric, logic, geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy). Kublai Khan requested also that an envoy bring him back oil of the lamp in Jerusalem. The long ''sede vacante

''Sede vacante'' ( in Latin.) is a term for the state of a diocese while without a bishop. In the canon law of the Catholic Church, the term is used to refer to the vacancy of the bishop's or Pope's authority upon his death or resignation.

Hi ...

'' between the death of Pope Clement IV in 1268 and the election of his successor delayed the Polos in fulfilling Kublai's request. They followed the suggestion of Theobald Visconti, then papal legate for the realm of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, and returned to Venice in 1269 or 1270 to await the nomination of the new Pope, which allowed Marco to see his father for the first time, at the age of fifteen or sixteen.

In 1271, Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo embarked on their voyage to fulfil Kublai's request. They sailed to

In 1271, Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo embarked on their voyage to fulfil Kublai's request. They sailed to Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

, and then rode on camels to the Persian port of Hormuz. The Polos wanted to sail straight into China, but the ships there were not seaworthy, so they continued overland through the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

, until reaching Kublai's summer palace in Shangdu, near present-day Zhangjiakou. In one instance during their trip, the Polos joined a caravan of travelling merchants whom they crossed paths with. Unfortunately, the party was soon attacked by bandits

Banditry is a type of organized crime committed by outlaws typically involving the threat or use of violence. A person who engages in banditry is known as a bandit and primarily commits crimes such as extortion, robbery, and murder, either as an ...

, who used the cover of a sandstorm to ambush them. The Polos managed to fight and escape through a nearby town, but many members of the caravan were killed or enslaved. Three and a half years after leaving Venice, when Marco was about 21 years old, the Polos were welcomed by Kublai into his palace. The exact date of their arrival is unknown, but scholars estimate it to be between 1271 and 1275. On reaching the Yuan court, the Polos presented the sacred oil from Jerusalem and the papal letters to their patron.

Marco knew four languages, and the family had accumulated a great deal of knowledge and experience that was useful to Kublai. It is possible that he became a government official; he wrote about many imperial visits to China's southern and eastern provinces, the far south and Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

. They were highly respected and sought after in the Mongolian court, and so Kublai Khan decided to decline the Polos' requests to leave China. They became worried about returning home safely, believing that if Kublai died, his enemies might turn against them because of their close involvement with the ruler. In 1292, Kublai's great-nephew, then ruler of Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, sent representatives to China in search of a potential wife, and they asked the Polos to accompany them, so they were permitted to return to Persia with the wedding party—which left that same year from Zaitun in southern China on a fleet of 14 junks

A junk (Chinese: 船, ''chuán'') is a type of Chinese sailing ship with fully battened sails. There are two types of junk in China: northern junk, which developed from Chinese river boats, and southern junk, which developed from Austronesian ...

. The party sailed to the port of Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, travelled north to Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

, and around the southern tip of India, eventually crossing the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea ( ar, اَلْبَحرْ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Bahr al-ˁArabī) is a region of the northern Indian Ocean bounded on the north by Pakistan, Iran and the Gulf of Oman, on the west by the Gulf of Aden, Guardafui Channe ...

to Hormuz. The two-year voyage was a perilous one—of the six hundred people (not including the crew) in the convoy only eighteen had survived (including all three Polos). The Polos left the wedding party after reaching Hormuz and travelled overland to the port of Trebizond on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

, the present-day Trabzon.

Role of Rustichello

The British scholar Ronald Latham has pointed out that ''The Book of Marvels'' was, in fact, a collaboration written in 1298–1299 between Polo and a professional writer of romances, Rustichello of Pisa.Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pp. 7–20 from ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', London: Folio Society, 1958 p. 11. It is believed that Polo related his memoirs orally to Rustichello da Pisa while both were prisoners of the Genova Republic. Rustichello wrote '' Devisement du Monde'' in Franco-Venetian language, which was the language of culture widespread in northern Italy between the subalpine belt and the lower Po between the 13th and 15th centuries. Latham also argued that Rustichello may have glamorised Polo's accounts, and added fantastic and romantic elements that made the book a bestseller. The Italian scholar Luigi Foscolo Benedetto had previously demonstrated that the book was written in the same "leisurely, conversational style" that characterised Rustichello's other works, and that some passages in the book were taken verbatim or with minimal modifications from other writings by Rustichello. For example, the opening introduction in ''The Book of Marvels'' to "emperors and kings, dukes and marquises" was lifted straight out of an Arthurian romance Rustichello had written several years earlier, and the account of the second meeting between Polo and Kublai Khan at the latter's court is almost the same as that of the arrival ofTristan

Tristan ( Latin/Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed ...

at the court of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

at Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as th ...

in that same book. Latham believed that many elements of the book, such as legends of the Middle East and mentions of exotic marvels, may have been the work of Rustichello who was giving what medieval European readers expected to find in a travel book.Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pp. 7–20 from ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', London: Folio Society, 1958 p. 12.

Role of the Dominican Order

Apparently, from the very beginning, Marco's story aroused contrasting reactions, as it was received by some with a certain disbelief. The Dominican father Francesco Pipino was the author of a translation into Latin, ''Iter Marci Pauli Veneti'' in 1302, just a few years after Marco's return to Venice. Francesco Pipino solemnly affirmed the truthfulness of the book and defined Marco as a "prudent, honoured and faithful man". inaldo Fulin, Archivio Veneto, 1924, p. 255/ref> In his writings, the Dominican brother Jacopo d'Acqui explains why his contemporaries were sceptical about the content of the book. He also relates that before dying, Marco Polo insisted that "he had told only a half of the things he had seen". According to some recent research of the Italian scholar Antonio Montefusco, the very close relationship that Marco Polo cultivated with members of theDominican Order

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of ...

in Venice suggests that local fathers collaborated with him for a Latin version of the book, which means that Rustichello's text was translated into Latin for a precise will of the Order.

Since Dominican fathers had among their missions that of evangelizing foreign peoples (cf. the role of Dominican missionaries in China and in the Indies), it is reasonable to think that they considered Marco's book as a trustworthy piece of information for missions in the East. The diplomatic communications between Pope Innocent IV and Pope Gregory X with the Mongols were probably another reason for this endorsement. At the time, there was open discussion of a possible Christian-Mongol alliance with an anti-Islamic function.Jean Richard, ''Histoire des Croisades'' (Paris: Fayard 1996), p.465 In fact, a Mongol delegate was solemny baptised at the Second Council of Lyon. At the council, Pope Gregory X promulgated a new Crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

to start in 1278 in liaison with the Mongols.

Authenticity and veracity

Since its publication, some have viewed the book with skepticism. Some in the Middle Ages regarded the book simply as a romance or fable, due largely to the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck, who portrayed the Mongols as '

Since its publication, some have viewed the book with skepticism. Some in the Middle Ages regarded the book simply as a romance or fable, due largely to the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck, who portrayed the Mongols as 'barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by some to be less ...

s' who appeared to belong to 'some other world'. Doubts have also been raised in later centuries about Marco Polo's narrative of his travels in China, for example for his failure to mention the Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand ''li'' wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic grou ...

, and in particular the difficulties in identifying many of the place names he used (the great majority, however, have since been identified). Many have questioned whether he had visited the places he mentioned in his itinerary, whether he had appropriated the accounts of his father and uncle or other travellers, and some doubted whether he even reached China, or that if he did, perhaps never went beyond Khanbaliq

Khanbaliq or Dadu of Yuan () was the winter capital of the Yuan dynasty of China in what is now Beijing, also the capital of the People's Republic of China today. It was located at the center of modern Beijing. The Secretariat directly admini ...

(Beijing).

It has, however, been pointed out that Polo's accounts of China are more accurate and detailed than other travellers' accounts of the period. Polo had at times refuted the 'marvellous' fables and legends given in other European accounts, and despite some exaggerations and errors, Polo's accounts have relatively few of the descriptions of irrational marvels. In many cases of descriptions of events where he was not present (mostly given in the first part before he reached China, such as mentions of Christian miracles), he made a clear distinction that they are what he had heard rather than what he had seen. It is also largely free of the gross errors found in other accounts such as those given by the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berber Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, largely in the Muslim ...

who had confused the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest river system in the world at the estimated length of . Originating in the Bayan Ha ...

with the Grand Canal and other waterways, and believed that porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises main ...

was made from coal.

Modern studies have further shown that details given in Marco Polo's book, such as the currencies used, salt productions and revenues, are accurate and unique. Such detailed descriptions are not found in other non-Chinese sources, and their accuracy is supported by archaeological evidence as well as Chinese records compiled after Polo had left China. His accounts are therefore unlikely to have been obtained second hand. Other accounts have also been verified; for example, when visiting Zhenjiang

Zhenjiang, alternately romanized as Chinkiang, is a prefecture-level city in Jiangsu Province, China. It lies on the southern bank of the Yangtze River near its intersection with the Grand Canal. It is opposite Yangzhou (to its north) a ...

in Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an eastern coastal province of the People's Republic of China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with it ...

, China, Marco Polo noted that a large number of Christian church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym fo ...

es had been built there. His claim is confirmed by a Chinese text of the 14th century explaining how a Sogdia

Sogdia ( Sogdian: ) or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also a province of the Achaemenid Emp ...

n named Mar-Sargis from Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top:Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zinda, ...

founded six Nestorian Christian churches there in addition to one in Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also Chinese postal romanization, romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the prov ...

during the second half of the 13th century. His story of the princess Kököchin sent from China to Persia to marry the Īl-khān is also confirmed by independent sources in both Persia and China.

Scholarly analyses

Explaining omissions

Sceptics have long wondered whether Marco Polo wrote his book based on hearsay, with some pointing to omissions about noteworthy practices and structures of China as well as the lack of details on some places in his book. While Polo describes paper money and the burning of coal, he fails to mention theGreat Wall of China

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand ''li'' wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic grou ...

, tea, Chinese characters

Chinese characters () are logograms developed for the writing of Chinese. In addition, they have been adapted to write other East Asian languages, and remain a key component of the Japanese writing system where they are known as ''kanji ...

, chopstick

Chopsticks ( or ; Pinyin: ''kuaizi'' or ''zhu'') are shaped pairs of equal-length sticks of Chinese origin that have been used as kitchen and eating utensils in most of East and Southeast Asia for over three millennia. They are held in the ...

s, or footbinding. His failure to note the presence of the Great Wall of China was first raised in the middle of the seventeenth century, and in the middle of the eighteenth century, it was suggested that he might have never reached China. Later scholars such as John W. Haeger argued that Marco Polo might not have visited Southern China due to the lack of details in his description of southern Chinese cities compared to northern ones, while Herbert Franke also raised the possibility that Marco Polo might not have been to China at all, and wondered if he might have based his accounts on Persian sources due to his use of Persian expressions. This is taken further by Frances Wood

Frances Wood (; born 1948) is an English librarian, sinologue and historian known for her writings on Chinese history, including Marco Polo, life in the Chinese treaty ports, and the First Emperor of China.

Biography

Wood was born in Londo ...

who claimed in her 1995 book '' Did Marco Polo Go to China?'' that at best Polo never went farther east than Persia (modern Iran), and that there is nothing in ''The Book of Marvels'' about China that could not be obtained via reading Persian books.Morgan, D.O. "Marco Polo in China—Or Not" 221–225 from ''The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society'', Volume 6, Issue # 2 July 1996 p. 222. Wood maintains that it is more probable that Polo only went to Constantinople (modern Istanbul, Turkey) and some of the Italian merchant colonies around the Black Sea, picking hearsay from those travellers who had been farther east.

Supporters of Polo's basic accuracy countered on the points raised by sceptics such as footbinding and the Great Wall of China. Historian Stephen G. Haw argued that the Great Walls were built to keep out northern invaders, whereas the ruling dynasty during Marco Polo's visit were those very northern invaders. They note that the Great Wall familiar to us today is a Ming

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han pe ...

structure built some two centuries after Marco Polo's travels; and that the Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

rulers whom Polo served controlled territories both north and south of today's wall, and would have no reasons to maintain any fortifications that may have remained there from the earlier dynasties. Other Europeans who travelled to Khanbaliq

Khanbaliq or Dadu of Yuan () was the winter capital of the Yuan dynasty of China in what is now Beijing, also the capital of the People's Republic of China today. It was located at the center of modern Beijing. The Secretariat directly admini ...

during the Yuan dynasty, such as Giovanni de' Marignolli and Odoric of Pordenone, said nothing about the wall either. The Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berber Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, largely in the Muslim ...

, who asked about the wall when he visited China during the Yuan dynasty, could find no one who had either seen it or knew of anyone who had seen it, suggesting that while ruins of the wall constructed in the earlier periods might have existed, they were not significant or noteworthy at that time.

Haw also argued that footbinding was not common even among Chinese during Polo's time and almost unknown among the Mongols. While the Italian missionary Odoric of Pordenone who visited Yuan China mentioned footbinding (it is however unclear whether he was merely relaying something he had heard as his description is inaccurate), no other foreign visitors to Yuan China mentioned the practice, perhaps an indication that the footbinding was not widespread or was not practised in an extreme form at that time. Marco Polo himself noted (in the Toledo manuscript) the dainty walk of Chinese women who took very short steps. It has also been noted by other scholars that many of the things not mentioned by Marco Polo such as tea and chopsticks were not mentioned by other travellers as well. Haw also pointed out that despite the few omissions, Marco Polo's account is more extensive, more accurate and more detailed than those of other foreign travellers to China in this period. Marco Polo even observed Chinese nautical inventions such as the watertight compartments of bulkhead partitions in Chinese ships, knowledge of which he was keen to share with his fellow Venetians.

In addition to Haw, a number of other scholars have argued in favour of the established view that Polo was in China in response to Wood's book. The book has been criticized by figures including Igor de Rachewiltz

Igor de Rachewiltz (April 11, 1929 – July 30, 2016) was an Italian historian and philologist specializing in Mongol studies.

Igor de Rachewiltz was born in Rome, the son of Bruno Guido and Antonina Perosio, and brother of Boris de Rachewilt ...

(translator and annotator of '' The Secret History of the Mongols'') and Morris Rossabi (author of ''Kublai Khan: his life and times''). The historian David Morgan points out basic errors made in Wood's book such as confusing the Liao dynasty

The Liao dynasty (; Khitan: ''Mos Jælud''; ), also known as the Khitan Empire (Khitan: ''Mos diau-d kitai huldʒi gur''), officially the Great Liao (), was an imperial dynasty of China that existed between 916 and 1125, ruled by the Yelü ...

with the Jin dynasty, and he found no compelling evidence in the book that would convince him that Marco Polo did not go to China. Haw also argues in his book ''Marco Polo's China'' that Marco's account is much more correct and accurate than has often been supposed and that it is extremely unlikely that he could have obtained all the information in his book from second-hand sources. Haw also criticizes Wood's approach to finding mention of Marco Polo in Chinese texts by contending that contemporaneous Europeans had little regard for using surnames and that a direct Chinese transliteration

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one script to another that involves swapping letters (thus ''trans-'' + '' liter-'') in predictable ways, such as Greek → , Cyrillic → , Greek → the digraph , Armenian → or L ...

of the name "Marco" ignores the possibility of him taking on a Chinese or even Mongol name with no similarity to his Latin name.

Also in reply to Wood, Jørgen Jensen recalled the meeting of Marco Polo and Pietro d'Abano in the late 13th century. During this meeting, Marco gave to Pietro details of the astronomical observations he had made on his journey. These observations are only compatible with Marco's stay in China, Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

and the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by the shores of South China (hence the name), in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Ph ...

and are recorded in Pietro's book ''Conciliator Differentiarum'', but not in Marco's ''Book of Travels''.

Reviewing Haw's book, Peter Jackson (author of ''The Mongols and the West'') has said that Haw "must surely now have settled the controversy surrounding the historicity of Polo's visit to China". Igor de Rachewiltz's review, which refutes Wood's points, concludes with a strongly-worded condemnation: "I regret to say that F. W.'s book falls short of the standard of scholarship that one would expect in a work of this kind. Her book can only be described as deceptive, both in relation to the author and to the public at large. Questions are posted that, in the majority of cases, have already been answered satisfactorily ... her attempt is unprofessional; she is poorly equipped in the basic tools of the trade, i.e., adequate linguistic competence and research methodology ... and her major arguments cannot withstand close scrutiny. Her conclusion fails to consider all the evidence supporting Marco Polo's credibility."

Allegations of exaggeration

Some scholars believe that Marco Polo exaggerated his importance in China. The British historian David Morgan thought that Polo had likely exaggerated and lied about his status in China, while Ronald Latham believed that such exaggerations were embellishments by his ghostwriter Rustichello da Pisa. This sentence in ''The Book of Marvels'' was interpreted as Marco Polo was "the governor" of the city of "Yangiu"Yangzhou

Yangzhou, postal romanization Yangchow, is a prefecture-level city in central Jiangsu Province (Suzhong), East China. Sitting on the north bank of the Yangtze, it borders the provincial capital Nanjing to the southwest, Huai'an to the north, ...

for three years, and later of Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also Chinese postal romanization, romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the prov ...

. This claim has raised some controversy. According to David Morgan no Chinese source mentions him as either a friend of the Emperor or as the governor of Yangzhou – indeed no Chinese source mentions Marco Polo at all.Morgan, D.O. "Marco Polo in China—Or Not" 221–225 from ''The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society'', Volume 6, Issue # 2 July 1996 p. 223. In fact, in the 1960s the German historian Herbert Franke noted that all occurrences of Po-lo or Bolod in Yuan texts were names of people of Mongol or Turkic extraction.

However, in the 2010s the Chinese scholar Peng Hai identified Marco Polo with a certain "Boluo", a courtier of the emperor, who is mentioned in the Yuanshi ("History of Yuan") since he was arrested in 1274 by an imperial dignitary named Saman. The accusation was that Boluo had walked on the same side of the road as a female courtesan, in contravention of the order for men and women to walk on opposite sides of the road inside the city. According to the "Yuanshi" records, Boluo was released at the request of the emperor himself, and was then transferred to the region of Ningxia, in the northeast of present-day China, in the spring of 1275. The date could correspond to the first mission of which Marco Polo speaks.

If this identification is correct, there is a record about Marco Polo in Chinese sources. These conjectures seem to be supported by the fact that in addition to the imperial dignitary Saman (the one who had arrested the official named "Boluo"), the documents mention his brother, Xiangwei. According to sources, Saman died shortly after the incident, while Xiangwei was transferred to Yangzhou in 1282–1283. Marco Polo reports that he was moved to Hangzhou the following year, in 1284. It has been supposed that these displacements are due to the intention to avoid further conflicts between the two. Giulio Busi, "Marco Polo. Viaggio ai confini del Medioevo", Collezione Le Scie. Nuova serie, Milano, Mondadori, 2018, , § "Boluo, il funzionario invisibile

The sinologist Paul Pelliot thought that Polo might have served as an officer of the government salt monopoly in Yangzhou, which was a position of some significance that could explain the exaggeration.

It may seem unlikely that a European could hold a position of power in the Mongolian empire. However, some records prove he was not the first nor the only one. In his book, Marco mentions an official named "Mar Sarchis" who probably was a Nestorian Christian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

, and he says he founded two Christian churches in the region of "Caigiu". This official is actually mentioned in the local gazette ''Zhishun Zhenjian zhi'' under the name "Ma Xuelijisi" and the qualification of "General of Third Class". Always in the gazette, it is said Ma Xuelijsi was an assistant supervisor in the province of Zhenjiang for three years, and that during this time he founded two Christian churches. In fact, it is a well-documented fact that Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

trusted foreigners more than Chinese subjects in internal affairs.

Stephen G. Haw challenges this idea that Polo exaggerated his own importance, writing that, "contrary to what has often been said ... Marco does not claim any very exalted position for himself in the Yuan empire."Stephen G. Haw (2006), ''Marco Polo's China: a Venetian in the Realm of Kublai Khan'', London & New York: Routledge, p. 173, . He points out that Polo never claimed to hold high rank, such as a ''darughachi

''Darughachi'' (Mongol form) or ''Basqaq'' (Turkic form) were originally designated officials in the Mongol Empire that were in charge of taxes and administration in a certain province. The plural form of the Mongolian word is ''darugha''. They ...

'', who led a '' tumen'' – a unit that was normally 10,000 strong. In fact, Polo does not even imply that he had led 1,000 personnel. Haw points out that Polo himself appears to state only that he had been an emissary of the khan

Khan may refer to:

*Khan (inn), from Persian, a caravanserai or resting-place for a travelling caravan

*Khan (surname), including a list of people with the name

*Khan (title), a royal title for a ruler in Mongol and Turkic languages and used by ...

, in a position with some esteem. According to Haw, this is a reasonable claim if Polo was, for example, a ''keshig Kheshig ( Mongolian: Khishig, Keshik, Khishigten for "favored", "blessed") were the imperial guard for Mongol royalty in the Mongol Empire, particularly for rulers like Genghis Khan and his wife Börte. Their primary purpose was to act as bodyguard ...

'' – a member of the imperial guard by the same name, which included as many as 14,000 individuals at the time.

Haw explains how the earliest manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced i ...

s of Polo's accounts provide contradicting information about his role in Yangzhou, with some stating he was just a simple resident, others stating he was a governor, and Ramusio's manuscript claiming he was simply holding that office as a temporary substitute for someone else, yet all the manuscripts concur that he worked as an esteemed emissary for the khan. Haw also objected to the approach to finding mention of Marco Polo in Chinese texts, contending that contemporaneous Europeans had little regard for using surnames, and a direct Chinese transcription of the name "Marco" ignores the possibility of him taking on a Chinese or even Mongol name that had no bearing or similarity with his Latin name.

Another controversial claim is at chapter 145 when the Book of Marvels states that the three Polos provided the Mongols with technical advice on building mangonels during the Siege of Xiangyang,

Since the siege was over in 1273, before Marco Polo had arrived in China for the first time, the claim cannot be true. The Mongol army that besieged Xiangyang did have foreign military engineers, but they were mentioned in Chinese sources as being from Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

and had Arabic names. In this respect, Igor de Rachewiltz

Igor de Rachewiltz (April 11, 1929 – July 30, 2016) was an Italian historian and philologist specializing in Mongol studies.

Igor de Rachewiltz was born in Rome, the son of Bruno Guido and Antonina Perosio, and brother of Boris de Rachewilt ...