Manuel Torres (diplomat) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Manuel de Trujillo y Torres (November 1762 – July15, 1822) was a Colombian publicist and diplomat. He is best known for being received as the first ambassador of Colombia by U.S. President

In the spring of 1776 the young Torres sailed to Cuba with his maternal uncle

In the spring of 1776 the young Torres sailed to Cuba with his maternal uncle

Quick to make American contacts, Torres became close friends with William Duane, who became editor of the Philadelphia newspaper ''

Quick to make American contacts, Torres became close friends with William Duane, who became editor of the Philadelphia newspaper ''

Torres' lobbying included domestic affairs; in February1815, near the end of

Torres' lobbying included domestic affairs; in February1815, near the end of

Another of the agents to join the junta was

Another of the agents to join the junta was

Torres' appointment coincided with a turn in the wars of independence. Where before the situation had been dire, the Patriot forces under Bolívar began a campaign to liberate New Granada and achieved a famous victory at the

Torres' appointment coincided with a turn in the wars of independence. Where before the situation had been dire, the Patriot forces under Bolívar began a campaign to liberate New Granada and achieved a famous victory at the

In February 1820, Torres came to Washington to purchase twenty thousand muskets from the U.S. government—a source that could fill what he could not obtain from private merchants. Monroe delayed by responding that the

In February 1820, Torres came to Washington to purchase twenty thousand muskets from the U.S. government—a source that could fill what he could not obtain from private merchants. Monroe delayed by responding that the

In June 1821, Mier returned to Philadelphia after escaping imprisonment in

In June 1821, Mier returned to Philadelphia after escaping imprisonment in

James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

on June19, 1822. This act represented the first U.S. recognition of a former Spanish colony's independence.

Born in Spain, he lived as a young adult in the colony of New Granada (present-day Colombia). After being implicated in a conspiracy against the monarchy he fled in 1794, arriving in the United States in 1796. From Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

he spent the rest of his life advocating for independence of the Spanish colonies in the Americas. Working closely with newspaper editor William Duane he produced English- and Spanish-language articles, pamphlets and books.

During the Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

he was a central figure in directing the work of revolutionary agents in North America, who frequently visited his home. In 1819 Torres was appointed a diplomat for Venezuela, which that year united with New Granada to form Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 18 ...

. As ''chargé d'affaires

A ''chargé d'affaires'' (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador ...

'' he negotiated significant weapons purchases but failed to obtain public loans. Having laid the groundwork for the diplomatic recognition

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state (may be also a recognized state). Recognition can be accorde ...

of Colombia, he died less than a month after achieving this goal. Though largely unknown today, he is remembered as an early proponent of Pan-Americanism

Pan-Americanism is a movement that seeks to create, encourage, and organize relationships, associations and cooperation among the states of the Americas, through diplomatic, political, economic, and social means.

History

Following the indepen ...

.

Early life

Manuel Torres was born in the Spanish region of Córdoba in early November 1762. His mother's family was from the city of Córdoba while his father's side was probably from nearby Baena. He was descended from the minor nobility on both sides of his family, a class with social stature but not necessarily wealth. In the spring of 1776 the young Torres sailed to Cuba with his maternal uncle

In the spring of 1776 the young Torres sailed to Cuba with his maternal uncle Antonio Caballero y Góngora

Antonio Caballero y Góngora (in full, ''Antonio Pascual de San Pedro de Alcántara Caballero y Góngora'') (24 May 1723 in Priego de Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain – 24 March 1796 in Córdoba) was a Spanish Roman Catholic prelate in the coloni ...

, who was consecrated there as bishop of Mérida in the Viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Amer ...

(modern Mexico). Torres would later attribute his republican ideals to his uncle, a man of the Enlightenment who was an extensive collector of books, art, and coins. After Caballero y Góngora was promoted to archbishop of Santa Fé de Bogotá

Santa Claus, also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Kris Kringle, or simply Santa, is a Legend, legendary figure originating in Western Christianity, Western Christian culture who is said to Christmas gift-bringer, bring ...

the family arrived in New Granada (modern Colombia) on June 29, 1778.

At age 17 Torres began working for the secretariat of the Viceroyalty and for the royal treasury. In the following seven years he learned finance and was able to observe the political and social conflicts in New Grenada, including the Revolt of the Comuneros

The Revolt of the Comuneros ( es, Guerra de las Comunidades de Castilla, "War of the Communities of Castile") was an uprising by citizens of Castile against the rule of Charles I and his administration between 1520 and 1521. At its height, th ...

. This was also the time of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, which Spain joined against Great Britain. Caballero y Góngora became viceroy in 1782 and ruled as a liberal modernizer.

Torres went to France in early 1785 to study at the , where he spent about a year and half learning military science

Military science is the study of military processes, institutions, and behavior, along with the study of warfare, and the theory and application of organized coercive force. It is mainly focused on theory, method, and practice of producing mil ...

and mathematics. As lieutenant of engineers ( es, teniente de ingenerios) he probably aided Colonel Domingo Esquiaqui's survey and helped reorganize the colonial garrisons. On presentation by the archbishop-viceroy, Torres was gifted land near Santa Marta

Santa Marta (), officially Distrito Turístico, Cultural e Histórico de Santa Marta ("Touristic, Cultural and Historic District of Santa Marta"), is a city on the coast of the Caribbean Sea in northern Colombia. It is the capital of Magdalena ...

by CharlesIV and established a successful plantation, which he named San Carlos. Torres married and at San Carlos had a daughter.

He became involved with political liberals of Bogotá's class (i.e., native New Granadians of European descent), joining a secret club led by Antonio Nariño

Antonio Amador José de Nariño y Álvarez del Casal (Santa Fé de Bogotá, Colombia 1765 – 1824 Villa de Leyva, Colombia)Hector, M., and A. Ardila. Hombres y mujeres en las letras de Colombia. 2. Bogota: Magisterio, 2008. 25. Print. was a C ...

where radical ideas were discussed freely. When in 1794 Nariño and other club members were implicated in a conspiracy against the Crown, Torres fled New Granada without his family. He first went to Curaçao

Curaçao ( ; ; pap, Kòrsou, ), officially the Country of Curaçao ( nl, Land Curaçao; pap, Pais Kòrsou), is a Lesser Antilles island country in the southern Caribbean Sea and the Dutch Caribbean region, about north of the Venezuela coast ...

, and in 1796 to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, then the capital of the United States.

Arrival in Philadelphia

Spanish Americans heading north tended to go to Philadelphia, Baltimore or (French-controlled) New Orleans, centers of commercial relations with the colonies. Philadelphia in particular was a symbol of republican ideals, which may have attracted Torres. Its trade with the Spanish colonies was significant and theAmerican Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

was the first learned society in the U.S. to nominate Spanish American members. At St.Mary's Church he joined a cosmopolitan community of Roman Catholics, including many from Spanish and French America.

Quick to make American contacts, Torres became close friends with William Duane, who became editor of the Philadelphia newspaper ''

Quick to make American contacts, Torres became close friends with William Duane, who became editor of the Philadelphia newspaper ''Aurora

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

'' in 1798. The editor continually published Torres' views on Spanish American independence in the paper, whose contents would be copied by others. Torres translated Spanish pamphlets

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a hard cover or binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' or it may consist of a ...

for Duane, and sometimes translated Duane's editorials to Spanish. In Spanish America the purpose of this literature was to praise the United States as an example of independent representative government

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a types of democracy, type of democracy where elected people Representation (politics), represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern liberal democr ...

to be emulated; in the United States it was to increase support for the independence movements.

Initially Torres was quite wealthy and received remittances from his wife, which helped him make important social connections. However, he had his money invested in risky merchant ventures; on one occasion he lost $40,000, on another $70,000—thus he was forced to live more modestly in later years.

Three years after Torres' arrival, a "Spaniard in Philadelphia" wrote the pamphlet ' (released in English as ''Observations on the Commerce of Spain with her Colonies, in Time of War''). The author, probably Torres, criticizes Spanish colonialism. In particular, Spain monopolized trade with the colonies to their detriment: during wartime the mother country could not supply the colonies with essential goods, and in peacetime the prices were too high. The author's solution is to implement a system of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

in the Americas. The pamphlet was reprinted in London by William Tatham

William is a male given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norm ...

.

Torres' residence increased the attraction of Philadelphia for Spanish American revolutionaries. Torres probably met Francisco de Miranda

Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza (28 March 1750 – 14 July 1816), commonly known as Francisco de Miranda (), was a Venezuelan military leader and revolutionary. Although his own plans for the independence of the Spani ...

(also exiled after a failed conspiracy) in 1805, shortly before Miranda's failed expedition to the Captaincy General of Venezuela

The Captaincy General of Venezuela ( es, Capitanía General de Venezuela), also known as the Kingdom of Venezuela (), was an administrative district of colonial Spain, created on September 8, 1777, through the Royal Decree of Graces of 1777, t ...

, and he met with Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and B ...

in 1806. The Spanish minister to the United States, Carlos Martínez de Irujo, reported Torres' activity to his superiors.

Coordinating revolutionaries

During the instability caused byNapoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's conquest of Spain—the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

—the people of the colonies followed the model of Peninsular Spanish provinces by organizing juntas to govern in the absence of central rule. Advocates of independence, who called themselves Patriots, argued that sovereignty reverted to the people when there was no monarch. They clashed with the Royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

, who supported the authority of the Crown. Starting in 1810 the Patriot juntas successively declared independence, and Torres was their natural point of contact in the United States.

Brokered weapons shipments

Although PresidentJames Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

's administration officially recognized no governments on either side, Patriot agents were permitted to seek weapons in the U.S., and American ports became bases for privateering

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

. Torres acted as an intermediary between the newly arrived agents and influential Americans, such as introducing (Simón's brother) to wealthy banker Stephen Girard. Juan Vicente successfully purchased weapons for Venezuela, but was lost at sea on his return journey in 1811.

Together with Telésforo de Orea from Venezuela, and Diego de Saavedra and Juan Pedro de Aguirre

Juan Pedro Julián Aguirre y López de Anaya (October 19, 1781 – July 17, 1837) was an Argentine revolutionary and politician.

Aguirre was born in Buenos Aires, on October 19, 1781, to parents Cristobal Aguirre Hordenana Lecue and Maria ...

from Buenos Aires, Torres brokered a plan to purchase 20,000 muskets and bayonets from the U.S. government. Girard agreed to finance the plan on the joint credit of Buenos Aires and Venezuela, but Secretary of State James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

blocked it by refusing to reply. Saavedra and Aguirre managed to ship only 1,000 muskets to Buenos Aires, but by the end of 1811 Torres had helped Orea supply Venezuela with about 24,000 weapons. New purchasers continued to arrive, and the supplies were an important contribution while the revolutionaries were suffering many defeats.

The new Spanish minister, Luís de Onís, covertly attempted to disrupt the weapons shipments. He became aware of the plan to purchase from the U.S. arsenal due to being informed by a postman. Onís reported on these subversive activities and his agents harassed suspected revolutionaries like Torres. Francisco Sarmiento and Miguel Cabral de Noroña, two associates of Onís, attempted to assassinate Torres in 1814—apparently on the minister's orders. Due to his aid for the revolution, Torres' estate in Royalist-controlled New Granada was confiscated after his wife and daughter died.

Public writing

Running out of money during this period, Torres sustained himself in part by teaching. With Louis Hargous he wrote an adaptation for both English- and Spanish-teaching of Nicolas Gouïn Dufief's ''Nature Displayed in Her Mode of Teaching Language to Man''. The lengthy book's title page styles Torres and Hargous as "professors of general grammar"; in the introduction they argue the importance to Americans of studying Spanish literature. Influential revised editions by Mariano Velázquez de la Cadena were published in New York (1825) and London (1826). Soon after ''Nature Displayed'' followed the 1812 pamphlet ' ("A Republican's Manual for the Use of a Free People"), which Torres probably wrote. Structured as a dialog, the anonymous pamphlet offers a defense of the U.S. system of government based on the philosophy ofJean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, and argues it should be a model for Spanish America. The contents suggest the author is "a conservative partisan of Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, which ...

".

Besides Duane's ''Aurora'', Torres sent news and opinion to Baptis Irvine's Baltimore ''Whig'' and New York ''Columbian'', Jonathan Elliot's ''City of Washington Gazette'', and Hezekiah Niles

Hezekiah Niles (October 10, 1777 – April 2, 1839), was an American editor and publisher of the Baltimore-based national weekly news magazine, ''Niles' Weekly Register'' (aka ''Niles' Register'') and the ''Weekly Register''.

Niles was born in ...

' Baltimore ''Weekly Register''. He acquainted himself with notables such as Congressman Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

, lawyer Henry Marie Brackenridge

Henry Marie Brackenridge (May 11, 1786 – January 18, 1871) was an American writer, lawyer, judge, superintendent, and U.S. Congressman from Pennsylvania.

Born in Pittsburgh in 1786, he was educated by his father, the writer and judge Hugh ...

, Baltimore Postmaster John Stuart Skinner

John Stuart Skinner (22 February 1788 – 21 March 1851) was an American lawyer, publisher, and editor. During his life he held several civil and government positions. He is associated with farming, domesticated animals, and agricultural m ...

, Judge Theodorick Bland and Patent Office head William Thornton

William Thornton (May 20, 1759 – March 28, 1828) was a British-American physician, inventor, painter and architect who designed the United States Capitol. He also served as the first Architect of the Capitol and first Superintendent of the Uni ...

. Especially the support of Clay, who became a champion of Spanish American independence in Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

, permitted him to lobby many influential officials.

Economic proposals

Torres' lobbying included domestic affairs; in February1815, near the end of

Torres' lobbying included domestic affairs; in February1815, near the end of War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

that had preoccupied the American public, he wrote two letters to President Madison describing a proposal for fiscal and financial reform. This included an equal and direct tax on all property, which Torres considered more just; ultimately he calculated a $1million budget surplus under his scheme and suggested gradual elimination of the national debt. In his December5 message to Congress, Madison did propose two ideas that Torres had favored: the establishment of a second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ac ...

and utilizing it to create a uniform national currency.

The same year, Torres authored ''An Exposition of the Commerce of Spanish America; with some Observations upon its Importance to the United States''. This work, published in 1816, was the first inter-American handbook. Torres plays on Anglo-American rivalry by arguing for the importance of establishing American over British commercial interests in this critical region, just as revolutionary agents in Britain suggested the opposite. Applying political economy

Political economy is the study of how Macroeconomics, economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and Economy, national economies) and Politics, political systems (e.g. law, Institution, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied ph ...

, he observes that a country with a negative balance of trade

The balance of trade, commercial balance, or net exports (sometimes symbolized as NX), is the difference between the monetary value of a nation's exports and imports over a certain time period. Sometimes a distinction is made between a balance ...

—like the United States—needs a source of gold and silver ''specie

Specie may refer to:

* Coins or other metal money in mass circulation

* Bullion coins

* Hard money (policy)

* Commodity money

Commodity money is money whose value comes from a commodity of which it is made. Commodity money consists of objects ...

''—like South America—to stabilize its currency and economy. The political commentary is interwoven with practical advice to merchants, followed by conversion tables between currencies and units of measure.

He momentarily returned to economics in April1818. Through Clay, Torres suggested to Congress that he had discovered a new way to make revenue collection and spending more efficient, which he would reveal in detail if he was promised a share of the government's savings. The preliminary proposal was referred to the House Committee on Ways and Means

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other program ...

, which declined to examine it for being too complex.

Philadelphia junta

By 1816, Spanish American propagandists had solidified American public opinion in favor of the Patriots. However, the propaganda victories did not translate into practical success: the Royalists reconquered New Granada and Venezuela by May 1816. Pedro José Gual, who had come to the United States to represent those governments, instead worked with Torres on a plan to liberate New Spain. They were joined by a number of other agents to form a "junta" of their own, which included Orea,Mariano Montilla

Mariano Montilla (8 September 1782 in Caracas – 22 September 1851 in Caracas) was a major general of the Army of Venezuela in the Venezuelan War of Independence.

Biography

Youth

As a young man he went to Spain where he joined the Ameri ...

, José Rafael Revenga

José Rafael Revenga y Hernández (24 November 1786 – 9 March 1852 venezuelatuya.com/ref>) was a minister of foreign affairs of Gran Colombia (1819–1821).

He was the 2nd Secretary of Foreign Affairs of Colombia starting 17 September 1825, ...

, Juan Germán Roscio

Juan Germán Roscio (27 May 1763 – 10 March 1821) was a Venezuelan lawyer and politician of Italian background. He served as the secretary of foreign affairs for the Supreme Junta, Junta of Caracas, as Venezuela's first foreign minister, ...

from Venezuela, Miguel Santamaría from Mexico, as well as from Buenos Aires.

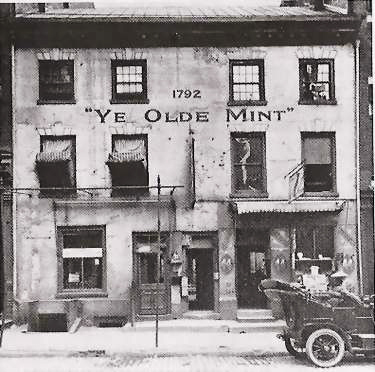

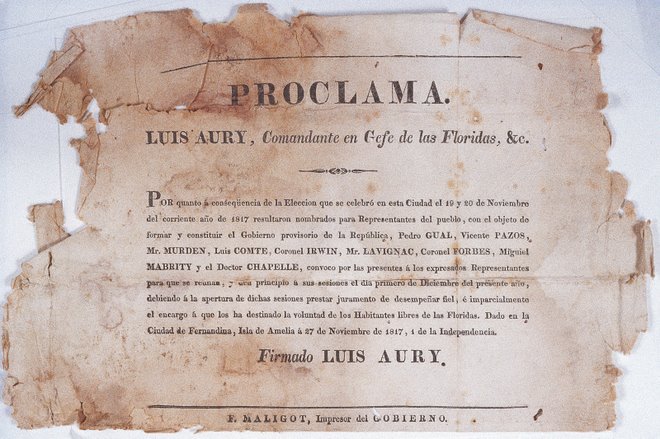

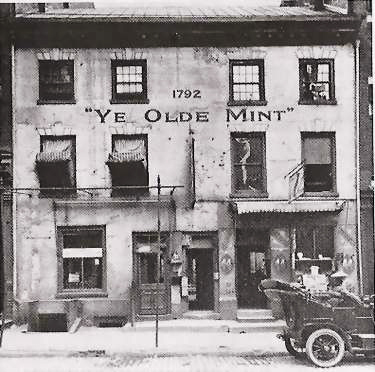

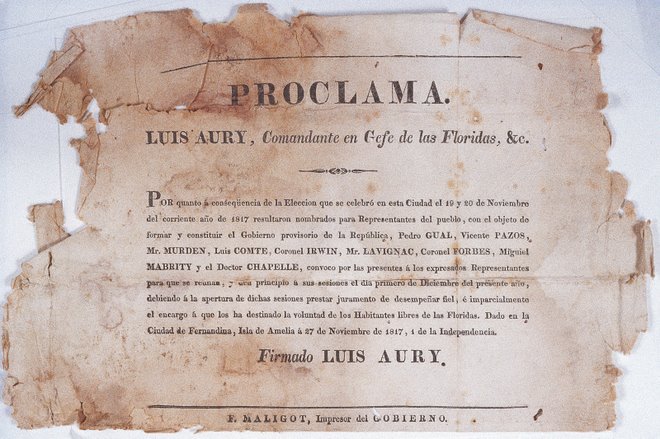

This Philadelphia junta surrounding Torres conspired in mid-1816 to invade a New Spanish port using ships commanded by French privateer Louis Aury. This plan failed because Aury's fleet was reduced to seven ships, making it unable to capture any major port. But the plotters were able to organize a force under the recently arrived General Francisco Xavier Mina

Francisco is the Spanish and Portuguese form of the masculine given name ''Franciscus''.

Nicknames

In Spanish, people with the name Francisco are sometimes nicknamed "Paco". San Francisco de Asís was known as ''Pater Comunitatis'' (father of ...

(despite the obstructions of José Alvarez de Toledo, an acquaintance of Torres who was actually spying for Onís). The operation was funded by a group of merchants from Baltimore, where Torres traveled to oversee it. The exiled priest Servando Teresa de Mier

Fray José Servando Teresa de Mier Noriega y Guerra (October 18, 1765 – December 3, 1827) was a Roman Catholic priest, preacher, and politician in New Spain. He was imprisoned several times for his controversial beliefs, and lived in exil ...

had traveled to the U.S. with Mina, and became a good friend of Torres. He brought to Mexico with him two copies of Torres' ''Exposition'' and one of the . The expedition sailed September 1816, but in just over a year Mina was captured and shot.

Another of the agents to join the junta was

Another of the agents to join the junta was Lino de Clemente

Lino de Clemente (1767–1834) was a figure in the movement to obtain Venezuelan independence from Spain.

Clemente was born in what is now Venezuela and received his early education in Spain before joining the Spanish Navy, where he served from 1 ...

, who in 1816 came to the United States as Venezuelan ''chargé d'affaires

A ''chargé d'affaires'' (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador ...

'' (a diplomat of the lowest rank). Torres became his secretary in Philadelphia. Clemente was one of the men who signed Gregor MacGregor

General Gregor MacGregor (24 December 1786 – 4 December 1845) was a Scottish soldier, adventurer, and confidence trickster who attempted from 1821 to 1837 to draw British and French investors and settlers to "Poyais", a fictional Central Am ...

's commission to seize Amelia Island

Amelia Island is a part of the Sea Islands chain that stretches along the East Coast of the United States from South Carolina to Florida; it is the southernmost of the Sea Islands, and the northernmost of the barrier islands on Florida's Atlantic ...

off the coast of Florida, what became a political scandal known as the Amelia Island affair

The Amelia Island affair was an episode in the history of Spanish Florida.

The Embargo Act (1807) and the abolition of the American slave trade (1808) made Amelia Island, on the coast of northeastern Florida, a resort for smugglers with som ...

. All who had been involved became intolerable to Monroe.

The Philadelphia junta effectively disbanded because of the event, which Simón Bolívar disavowed. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

refused any further communication with Clemente. Although Torres participated, he had discreetly avoided public involvement. (Privately he derided "Don Quixote

is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'' or, in Spanish, (changing in Part 2 to ). A founding work of Wester ...

" Aguirre and Pazos.) In October1818, Bolívar thus instructed Clemente to return home and to transfer his duties as ''chargé d'affaires'' to Torres.

Diplomat for Colombia

Torres' appointment coincided with a turn in the wars of independence. Where before the situation had been dire, the Patriot forces under Bolívar began a campaign to liberate New Granada and achieved a famous victory at the

Torres' appointment coincided with a turn in the wars of independence. Where before the situation had been dire, the Patriot forces under Bolívar began a campaign to liberate New Granada and achieved a famous victory at the Battle of Boyacá

The Battle of Boyacá (1819), was the decisive battle that ensured the success of Bolívar's campaign to liberate New Granada. The battle of Boyaca is considered the beginning of the independence of the north of South America, and is considered i ...

. When Torres received his diplomatic credentials he was authorized "to do in the United States everything possible to put an immediate end to the conflict in which the patriots of Venezuela are now engaged for their independence and liberty." Venezuela and New Granada united on December17, 1819, to form the Republic of Colombia (a union called Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 18 ...

by historians).

Francisco Antonio Zea

Juan Francisco Antonio Hilarión Zea Díaz (23 November 1766 – 28 November 1822) was a Neogranadine journalist, botanist, diplomat, politician, and statesman who served as Vice President of Colombia under then President Simón Bolívar. He wa ...

was first appointed Colombia's envoy

Envoy or Envoys may refer to:

Diplomacy

* Diplomacy, in general

* Envoy (title)

* Special envoy, a type of diplomatic rank

Brands

*Airspeed Envoy, a 1930s British light transport aircraft

*Envoy (automobile), an automobile brand used to sell Br ...

to the United States but never went there; Torres was authorized to take over his duties on May15, 1820, and thus formally empowered to negotiate for the republic. He would try to secure its independence by three methods: by purchasing weapons and other military supplies, by obtaining a loan, and by obtaining diplomatic recognition

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state (may be also a recognized state). Recognition can be accorde ...

of its government.

Weapons purchases

With the help of Samuel Douglas Forsyth, an American citizen sent from Venezuela by Bolívar, Torres was instructed to procure thirty thousand muskets on credit. This sum was not realistically available from private sources, in part due to thePanic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic h ...

. Torres did make substantial deals, especially with Philadelphia merchant Jacob Idler, who represented a network of business associates.

In one such contract, signed April4, 1819, Idler promised a total of $63,071.50 of supplies, including 4,023 muskets and 50 quintals of gunpowder. After delivery Colombia was obliged to make payment in gold, silver or the tobacco produce of the Barinas province. More agreements on this model followed as merchants gained confidence with the news of successive Patriot victories. From December1819 to April1820 negotiated contracts worth $108,842.80 () and in the summer, Torres made a deal for the Colombian navy.

Although Torres repeatedly wrote to his superiors about the great importance of maintaining Colombia's credit among American merchants, the government failed to make payment as agreed. In spite of this Torres was able to negotiate continued shipments, even with merchants who had unpaid claims. After independence, such claims became a significant problem of U.S. relations with South America; Idler's estate would litigate them up to the end of the century. Nevertheless, Torres obtained from Idler 11,571 muskets, and other supplies such as shoes and uniforms. They arrived in Venezuela in 1820–1821 aboard the ''Wilmot'' and ''Endymion''.

In February 1820, Torres came to Washington to purchase twenty thousand muskets from the U.S. government—a source that could fill what he could not obtain from private merchants. Monroe delayed by responding that the

In February 1820, Torres came to Washington to purchase twenty thousand muskets from the U.S. government—a source that could fill what he could not obtain from private merchants. Monroe delayed by responding that the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

prevented him from selling weapons without the consent of Congress, but his cabinet considered a missive from Torres. This missive argued for the sale by emphasizing the common interests of the American republics against the European monarchies. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun and Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson

Smith Thompson (January 17, 1768 – December 18, 1843) was a US Secretary of the Navy from 1819 to 1823 and a US Supreme Court Associate Justice from 1823 to his death.

Early life and the law

Born in Amenia, New York, Thompson graduated ...

were supportive, and Torres had estimated the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

was in his favor. However, Secretary of State Adams emphatically spoke against what he considered a violation of American neutrality, causing the cabinet to unanimously decline the request in a meeting on March29.

The next day Adams explained his feelings to Monroe:

Despite this skepticism, Adams trusted Torres to inform him on Spanish American affairs, perhaps because Torres was also strongly supportive of the United States. Torres made six repeat visits to Adams through February19, 1821, without success.

Attempted borrowing

Recognizing the financial difficulty the Colombian government was in, Torres attempted to borrow money in the United States on its behalf. Aided by a letter of introduction from Henry Clay, in the fall of 1819 he proposed a $500,000 loan () toLangdon Cheves

Langdon Cheves ( September 17, 1776 – June 26, 1857) was an American politician, lawyer and businessman from South Carolina. He represented the city of Charleston in the United States House of Representatives from 1810 to 1815, where he played ...

, president of the Second Bank of the United States. It would be repaid with Colombian bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from t ...

, which the Bank was severely short of, within 18 months. When the Bank stated it had no authority to lend to foreign governments, Torres restated his proposal as a of bullion. He also contacted Adams, who said the government had no objection and left it to the Bank directors' judgment, and gained Cheves' support. Despite continued negotiation this loan was never finalized—let alone Bolívar's bolder proposal for the Bank to take on the entirety of Venezuela's national debt in exchange for the Santa Ana de Mariquita silver mine in New Granada. Colombia had poor credit, and Torres believed the distressed Bank was actually unable to make the loan.

To improve Colombia's financial reputation Torres circulated several public memorials, and he continued to seek loans from other sources. Idler introduced him to Philip Contteau, the American agent of the Dutch merchant firm Mees, Boer and Moens. On April8, 1820, Torres and Contteau negotiated a loan of $4million ($) at eight percent interest. Colombia would maintain a state monopoly on Barinas tobacco, and would give sole control of the tobacco to Mees, Boer and Moens until the proceeds had repaid the loan. These terms were sent to Colombia and Holland for approval.

Torres was instructed to borrow as much as $20million ($), an impossible request. He did hope to build on his success by borrowing an additional $1million ($) with participation from the U.S. government. He made the request to Adams during the winter of 1820–1821, and obtained support from Monroe and Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as US Secretary of War and US Secretary of the Treasury before he ran for US president in the 1824 ...

. However, like the weapons purchase, this proposal failed due to Adams' commitment to neutrality.

The loan in its original form was approved by the Colombian government, but before the Dutch lenders could agree to it Barinas was recaptured by the Royalists. Without the source of tobacco on which repayment depended, the bankers rejected the loan.

Thus, Torres was ultimately unable to borrow any money for Colombia. Historian Charles Bowman assessed Torres as a talented negotiator with an "exceptional knowledge of high finance", who failed due to circumstances beyond his control.

Influence in pamphleteering

In June 1821, Mier returned to Philadelphia after escaping imprisonment in

In June 1821, Mier returned to Philadelphia after escaping imprisonment in Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, and moved into Torres' house. (Another Spanish American agent, Vicente Rocafuerte

Vicente Rocafuerte y Bejarano (1 May 1783 – 16 May 1847) was an influential figure in Ecuadorian politics and President of Ecuador from 10 September 1834 to 31 January 1839.

He was born into an aristocratic family in Guayaquil, Ecuador, an ...

, was already living there.) Connected through Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

, Torres became a father figure to Mier, signing his letters He gradually drew Mier away from constitutional monarchism and toward the republican model of the United States. In doing so Torres tried to provide a political-philosophical basis for Mier's radicalism. The pair encouraged Colombia to send a diplomat to Mexico, hoping to counter the rising monarchism there. When Mier published his as well as a new edition of Bartolomé de Las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar ...

' , Torres paid the costs.

Torres, Mier and Rocafuerte worked together to publish numerous articles over the next few months. The nature of their cooperation is disputed. Historian José de Onís mentions that "some Spanish American critics assert that Torres' works are generally regarded as having been written by Mier and Vicente Rocafuerte. This would be hard to verify." But Charles Bowman gives the opposite interpretation: "It is likely that several of the works generally attributed to either Mier or Rocafuerte were actually from Torres' pen."

In particular, Bowman believes a pamphlet bearing Mier's name, , was actually Torres' work. Discussing political organization after the revolution, the author suggests a "Spanish America Divided in Two Grand Departments, North and South, or Septentrional and Meridional." Bowman bases this attribution on a moderation uncommon for Mier, and the use of statistics Mier would not have known. Torres' motive for publishing it under Mier's name would have been to avoid controversy and thus protect his influence with Adams.

During this period Torres also became friends with Richard W. Meade, a Philadelphia merchant who had in 1820 returned from imprisonment in Spain. He had a claim against the Spanish government that the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined t ...

required him to collect from the U.S. government instead. Meade was a pewholder of St. Mary's Church, like Torres. Through the diplomat, Mier and Meade began working together in a controversy surrounding the parish priest, William Hogan, who had been excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

. Torres did not get publicly involved in the battle of pamphlets; Mier left Philadelphia for Mexico in September 1821, traveling with a Colombian passport Torres had issued him.

Diplomatic recognition

On the same day theU.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

voted to ratify the Adams–Onís Treaty, February19, 1821, Torres met with Adams. The next day he formally requested the recognition of Colombia "as a free and independent nation, a sister republic". He expected that first the United States would take possession of the new territory, while in the meantime Colombia gained increasing military control over its own, and that recognition would soon follow.

Torres suffered a three-month illness in late 1821 but on November30 wrote to Adams reporting the latest developments in Colombia. He glorified its achievement of near-total military victory, the extent of its population and territory, and its potential for commerce:

The purpose of these boasts was to underscore the importance of the U.S. being the first to recognize its independence, to which Torres added warnings about the unstable politics of Mexico and Peru. The letter received significant publicity because of its extensive information and ambitious statement of Colombia's importance.

President Monroe noted the success of Colombia and the other former colonies in his December3 message to Congress, a signal that recognition was imminent. Torres wrote letters to Adams on December30 and January2 reporting Colombia's new constitution, a sign the republic was stable. He hoped to go to Washington to state the case for recognition in person, but was prevented by illness and poverty. The House of Representatives asked the administration on January30 to report on the state of South America. Colombia's ''de facto'' independence as a republic, and the conclusion of Adams' treaty with Spain, encouraged the hesitant administration that the time was ripe for recognition. During this same period, the Colombian government was starting to see the prospect of recognition as hopeless.

Torres' health declined intermittently over the winter; his weakening disposition was attributed to asthma and severe overwork. "If I could move to a good climate where there were no books, paper, or pen and where I could speak of politics in a word, ... with my little garden and a horse to carry me about, perhaps I could convalesce", he wrote to Mier. But in March, Monroe reported to the House that the Spanish American governments had "a claim to recognition by other powers which ought not to be resisted." The formerly reluctant Adams dismissed a protest by Spanish minister Joaquín de Anduaga by calling the recognition "the mere acknowledgment of existing facts". By May4, the House and Senate had sent Monroe resolutions in support of recognition and an appropriation to put this into effect; this news was greatly celebrated in Colombia. Pedro José Gual, now the Colombian secretary of state and foreign relations, wrote to Bolívar that Torres deserved sole credit for the achievement.

The question remained when to send ministers and whom to recognize first. At this time, Torres was the only authorized agent in the United States for any of the Patriot governments. It was Adams' suggestion that Torres should be received as ''chargé d'affaires'' immediately, with the United States reciprocating after other diplomats arrived; Monroe agreed to thus formalize his existing relationship with Torres. The ''chargé'' was invited on May23 but delayed by his poor health. Nevertheless, he insisted on traveling to Washington.

At 1p.m. on June19, Torres was received at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

by Adams and Monroe. The weakened Torres told them of the importance of recognition to Colombia, and wept when the President said how satisfied he was for Torres to be received as its first representative. Indeed, he was the first representative from any Spanish American government. On leaving the short meeting, Torres gave Adams a print of the Colombian constitution.

Before Torres departed Washington, Adams visited him on June21; he promised Adams to work for equal tariffs on American and European goods in Colombia, and predicted would be sent to the U.S. as permanent diplomat. Adams published a satisfied announcement in the ''National Intelligencer

The ''National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser'' was a newspaper published in Washington, D.C., from October 30, 1800 until 1870. It was the first newspaper published in the District, which was founded in 1790. It was originally a Tri- ...

''.

Death

In rapidly declining health, Torres returned to Hamiltonville, now inWest Philadelphia

West Philadelphia, nicknamed West Philly, is a section of the city of Philadelphia. Alhough there are no officially defined boundaries, it is generally considered to reach from the western shore of the Schuylkill River, to City Avenue to the nort ...

, where that spring he had purchased a new home. Duane was with him when he died there at 2p.m. on July15, 1822, at age59.

On July17, the funeral procession began from Meade's house, which was joined by Commodore Daniels of the Colombian navy and prominent citizens. The procession went to St.Mary's, where the requiem mass was held by Father Hogan and Torres was buried with military honors

A military funeral is a memorial or burial rite given by a country's military for a soldier, sailor, marine or airman who died in battle, a veteran, or other prominent military figures or heads of state. A military funeral may feature guards ...

. Ships in the harbor held their flags at half-mast. This highly unusual display of honor was not only because Torres was well-liked, but also because he was the first foreign diplomat to die in the United States. An obituary named him "the Franklin

Franklin may refer to:

People

* Franklin (given name)

* Franklin (surname)

* Franklin (class), a member of a historical English social class

Places Australia

* Franklin, Tasmania, a township

* Division of Franklin, federal electoral d ...

of South America".

Duane and Meade were the executors of his estate. Not yet aware of his death, the Colombian government appointed him consul-general

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

and (as he had predicted) sent Salazar as envoy to succeed him.

Legacy

Sources for Torres' life include his voluminous correspondence, his published writing, newspaper articles, and Adams and Duane's memoirs. His long exile from Colombia has tended to obscure him in diplomatic history compared to his contemporaries; indeed his grave site was forgotten until rediscovered by historianCharles Lyon Chandler

Charles Lyon Chandler (December 29, 1883June 29, 1962) was an American consul and historian of Latin America–United States relations. A Harvard graduate who came to South America in the Consular Service, he became a student and proponen ...

in 1924.

R. Dana Skinner called him "the first panamericanist" that year. During the U.S. Sesquicentennial Exposition

The Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition of 1926 was a world's fair in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Its purpose was to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence, and the 50th anniversary o ...

in 1926, a plaque was placed at St. Mary's that honors him as "the first Latin American diplomatic representative in the United States of America." It was a gift "from the government of Colombia and Philadelphian descendants of his friends", including Duane's great-great-grandson. The ceremony was attended by Colombian minister Enrique Olaya

Enrique Alfredo Olaya Herrera (12 November 1880 – 18 February 1937) was a Colombian journalist and politician. He served as President of Colombia from 7 August 1930 until 7 August 1934 representing the Colombian Liberal Party.

Early years

...

, who held him up as a model for cooperation of the peoples of the New World.

Responding to an accusation by Spanish writer J. E. Casariego that Torres was a traitor to his native Spain, Nicolás García Samudio in 1941 called him a patriot, even the originator of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile ac ...

—though that specific claim has been met skeptically. A 1946 article suggested Torres had not been given a large enough place in Colombian diplomatic histories, and likewise praised him as a "precursor of pan-Americanism".

In the United States, Torres is given modest attention in general diplomatic histories,E.g., ; ; . but his importance is promoted by historians of Spanish American agents. In the judgment of José de Onís, Torres was "the most successful of all the Spanish American agents". Charles H. Bowman Jr. wrote a master's thesis and a series of articles about Torres in the 1960s and 1970s. To celebrate the 150th anniversary of U.S.–Latin American relations in 1972, the Permanent Council of the Organization of American States

The Permanent Council is one of the two main political bodies of the Organization of American States, the other being the General Assembly.

The Permanent Council is established under Chapter XII of the OAS Charter. It is composed of ambassadors ap ...

held a session in Philadelphia because it was the home of Manuel Torres.

However, Emily García documented that in 2016 Torres was obscure even to the archivists of St. Mary's, where the plaque still hangs. That he is mostly unknown today, despite being celebrated in his time and with the plaque, is for her illustrative that "Latino

Latino or Latinos most often refers to:

* Latino (demonym), a term used in the United States for people with cultural ties to Latin America

* Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States

* The people or cultures of Latin America;

** Latin A ...

s inhabit a paradoxical position in the larger U.S. national imaginary." Her book chapter analyzes him as the embodiment of a culture bridge that existed between Philadelphia and Spanish America: while he helped spread U.S. ideals to the south, he also brought Spanish influences to the north. This dual nature is characteristic of Torres' life and thinking.

Works

* English translation 1800. * * *Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Torres, Manuel (diplomat) 1762 births 1822 deaths Ambassadors of Colombia to the United States Colombian writers Writers from Philadelphia People of the Colombian War of Independence American people of Spanish descent Spanish emigrants to Colombia Colombian Roman Catholics Catholics from Pennsylvania