Manifesto of the Sixteen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Manifesto of the Sixteen'' (french: Manifeste des seize), or ''Proclamation of the Sixteen'', was a document drafted in 1916 by eminent

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Kropotkin was arrested under suspicion of having motivated the assassins. While in jail, Kropotkin was interviewed for an article to appear in the August 27 edition of ''

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Kropotkin was arrested under suspicion of having motivated the assassins. While in jail, Kropotkin was interviewed for an article to appear in the August 27 edition of ''

As a result of his firm support of the war, Kropotkin's popularity dwindled, and many former friends cut ties with him. Two exceptions included Rudolf Rocker and Alexander Schapiro, but both were serving prison sentences at the time. As a result, Kropotkin became increasingly isolated during his final years in London prior to his return to Russia. In ''Peter Kropotkin: His Federalist Ideas'' (1922), an overview of Kropotkin's writings by

As a result of his firm support of the war, Kropotkin's popularity dwindled, and many former friends cut ties with him. Two exceptions included Rudolf Rocker and Alexander Schapiro, but both were serving prison sentences at the time. As a result, Kropotkin became increasingly isolated during his final years in London prior to his return to Russia. In ''Peter Kropotkin: His Federalist Ideas'' (1922), an overview of Kropotkin's writings by

''Manifeste des seize'' and responses to the ''Manifesto''

, archived January 21, 2001

at the Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia {{DEFAULTSORT:Manifesto Of The Sixteen Anarchist manifestos Cultural history of World War I History of anarchism Politics of World War I World War I publications Anarchism in Russia 1916 in politics 1916 documents

anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

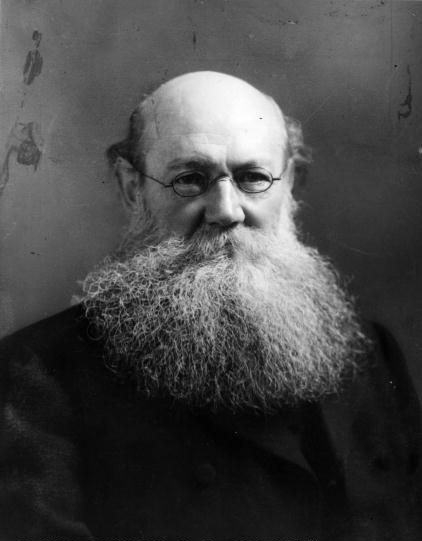

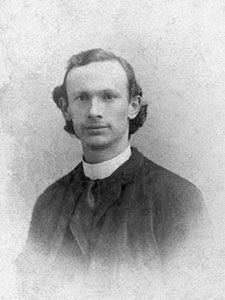

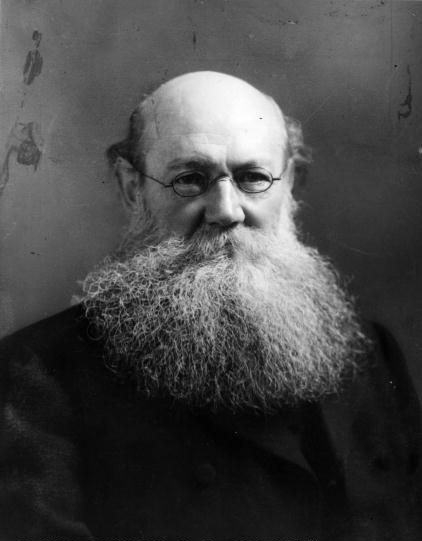

Peter Kropotkin and Jean Grave

Jean Grave (; October 16, 1854, Le Breuil-sur-Couze – December 8, 1939, Vienne-en-Val) was an important activist in the French anarchist and the international anarchist communism movements. He was the editor of three major anarchist periodica ...

which advocated an Allied victory over Germany and the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

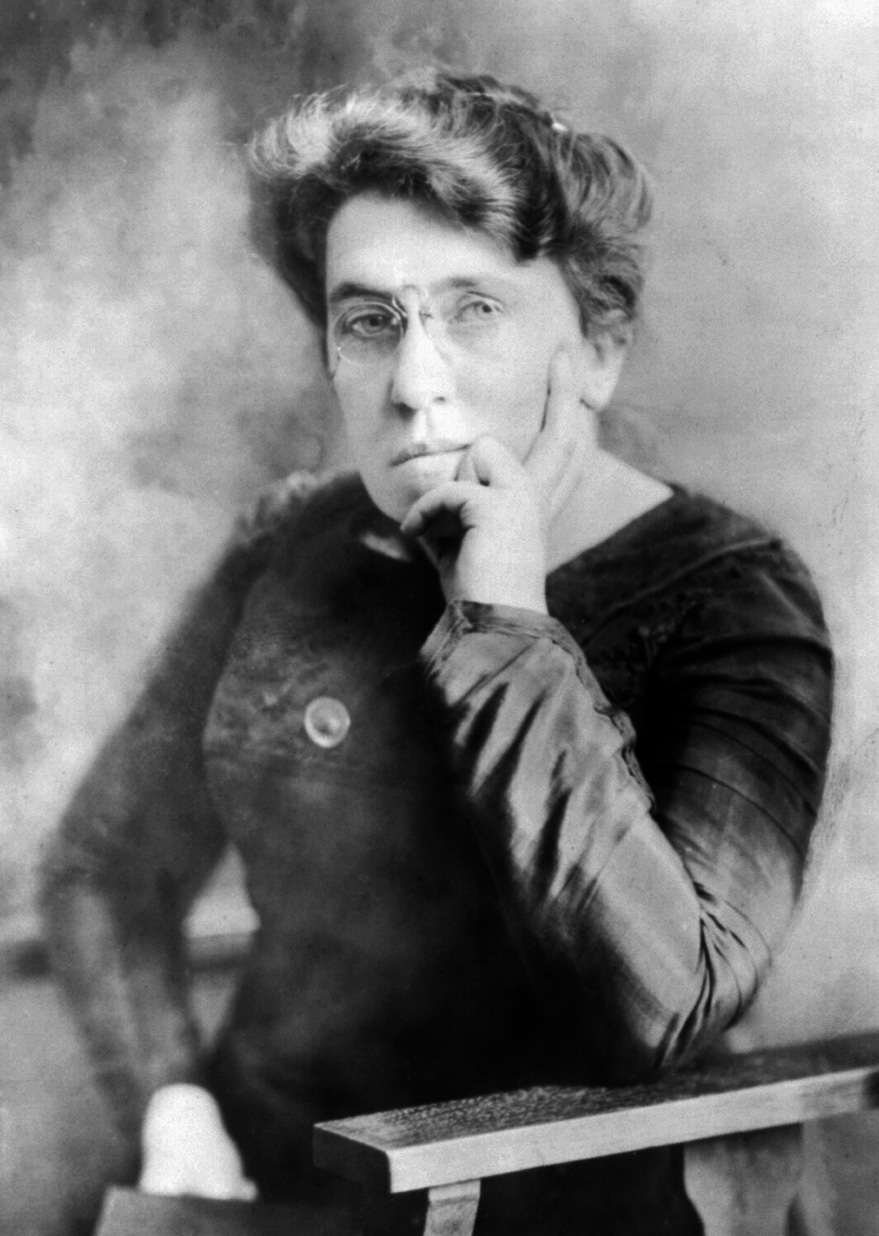

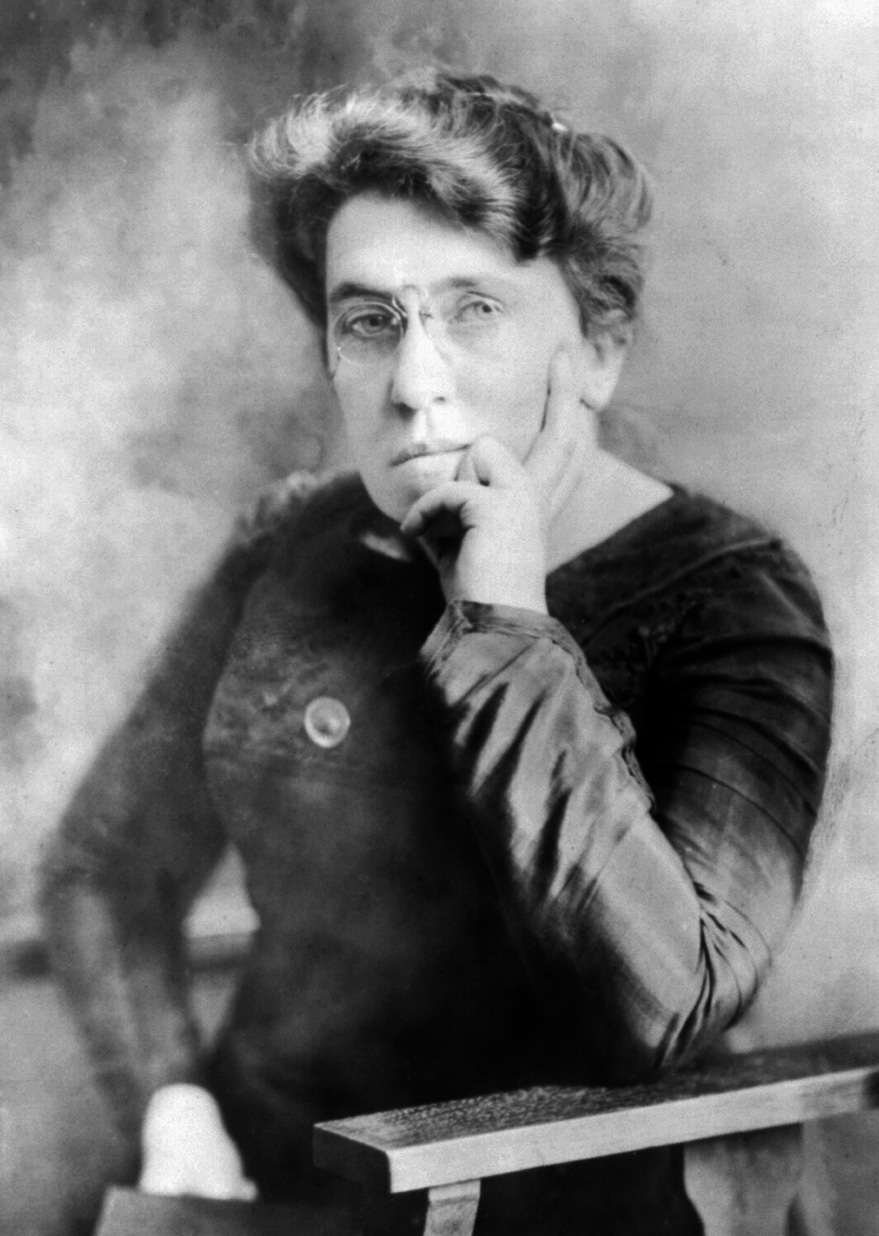

. At the outbreak of the war, Kropotkin and other anarchist supporters of the Allied cause advocated their position in the pages of the '' Freedom'' newspaper, provoking sharply critical responses. As the war continued, anarchists across Europe campaigned in anti-war movements and wrote denunciations of the war in pamphlets and statements, including one February 1916 statement signed by prominent anarchists such as Emma Goldman and Rudolf Rocker

Johann Rudolf Rocker (March 25, 1873 – September 19, 1958) was a German anarchist writer and activist. He was born in Mainz to a Roman Catholic artisan family.

His father died when he was a child, and his mother when he was in his teens, so he ...

.

At this time, Kropotkin was in frequent correspondence with those who shared his position, and was convinced by one of their number, Jean Grave, to draft a document encouraging anarchist support for the Allies. The resulting manifesto was published in the pages of the pro-war socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

periodical '' La Bataille '' on March 14, 1916, and republished in other European anarchist periodicals shortly thereafter. The manifesto declared that supporting the war was an act of resistance against the aggression of the German Empire, and that the war had to be pursued until its defeat. At this point, the authors conjectured, the ruling political parties of Germany would be overthrown and the anarchist goal of the emancipation of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

and of the German people would be advanced.

Contrary to its misleading title, the ''Manifesto of the Sixteen'' had originally fifteen signatories—among them some of the most eminent anarchists in Europe—and was later countersigned by another hundred. The position of the ''Manifesto'' was in stark contrast to that of most anarchists of the day, many of whom denounced its signatories and their sympathizers, and accused them of betraying anarchist principles. In the fallout over the war, Kropotkin became increasingly isolated, with many former friends cutting their ties to him. The Russian anarchist movement was split into two, with a faction supporting Kropotkin's position to the strong criticism of the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. Elsewhere, the Spanish and Swiss anarchist movements dismissed the ''Manifesto'' and marginalized its supporters.

Background

Kropotkin's anti-German stance

Anti-German sentiment

Anti-German sentiment (also known as Anti-Germanism, Germanophobia or Teutophobia) is opposition to or fear of Germany, its inhabitants, its culture, or its language. Its opposite is Germanophilia.

Anti-German sentiment largely began wit ...

was a strong current in progressive and revolutionary movements in Russia from their early beginnings, due to German influence on the aristocracy of the ruling Romanov dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

. Historian George Woodcock

George Woodcock (; May 8, 1912 – January 28, 1995) was a Canadian writer of political biography and history, an anarchist thinker, a philosopher, an essayist and literary critic. He was also a poet and published several volumes of travel wri ...

contended that as a Russian, Kropotkin was influenced by similar opinions throughout his life, culminating in a staunch anti-German prejudice at the onset of the First World War. Kropotkin was also influenced by fellow Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

, who was affected by his rivalry with Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

; the successes of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which subverted Germany's revolutionary movements; and the rise of the German Empire under the rule of Otto von Bismarck. As such, Woodcock notes Kropotkin came to despise the growth of Marxism, "German ideas", and augmented this with an interest in the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, which Woodcock referred to as "a kind of adoptive patriotism".

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Kropotkin was arrested under suspicion of having motivated the assassins. While in jail, Kropotkin was interviewed for an article to appear in the August 27 edition of ''

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Kropotkin was arrested under suspicion of having motivated the assassins. While in jail, Kropotkin was interviewed for an article to appear in the August 27 edition of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''. The piece, which referred to him as a "veteran Russian agitator and democrat", quoted him as an optimistic supporter of the newly erupted war, believing it would ultimately have a liberalizing effect on Russian society. In a letter to Jean Grave

Jean Grave (; October 16, 1854, Le Breuil-sur-Couze – December 8, 1939, Vienne-en-Val) was an important activist in the French anarchist and the international anarchist communism movements. He was the editor of three major anarchist periodica ...

, written in September of that year, Kropotkin chastised Grave for desiring a peaceful end to the conflict, and insisted that the war must be fought to its end since "the conditions of peace would be imposed by the victor".

Months later, Kropotkin allowed a letter he wrote to be included in an October 1914 issue of '' Freedom''. Entitled "A Letter to Steffen", in it he made his case for the war, arguing that the presence of Germany's empire had prevented the progress of anarchist movements throughout Europe, and that the German people were as culpable for the war as the German state was. He also claimed that Russia's populace would be radicalized and united following victory in the war, preventing the Russian aristocracy from benefiting from the conflict. As such, he claimed that tactics designed to end the war, such as pacifism and general strikes, were unnecessary, and that instead the war should be pursued until Germany was defeated.

The Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s quickly responded to Kropotkin's militarism in a bid for political capital

Political capital is the term used for an individual's ability to influence political decisions. This capital is built from what the opposition thinks of the politician, so radical politicians will lose capital. Political capital can be understoo ...

. Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

published a 1915 article in ''The National Pride of the Great Russians'', in which he attacked Kropotkin and Russian anarchists ''en masse'' for the former's early pro-war sentiment, and denounced Kropotkin and another political enemy, Georgi Plekhanov, as "chauvinists by opportunism or spinelessness". In other speeches and essays, Lenin referred to Kropotkin in the early years of the war as a "bourgeoisie", demoting him in the following months to "petit bourgeoisie".

Throughout 1915 and 1916, Kropotkin, who lived in Brighton, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, was often in poor health. He was unable to travel during the winter, having been ordered not to do so by doctors in January 1915, and underwent two operations to his chest in March. As a result, he was confined to a bed for the majority of 1915 and to a wheeled bath-chair in 1916. During this time, Kropotkin kept a steady correspondence with other anarchists, including fellow Russian anarchist Marie Goldsmith

Maria Isidorovna Goldsmith (russian: Мария Исидоровна Гольдсмит; 1862–1933), also known as Marie Goldsmith, was a Russian Jewish anarchist and collaborator of Peter Kropotkin. She also wrote under the pseudonyms Maria ...

. Goldsmith and Kropotkin clashed often on their opinions about the World War

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

, the role of internationalism

Internationalism may refer to:

* Cosmopolitanism, the view that all human ethnic groups belong to a single community based on a shared morality as opposed to communitarianism, patriotism and nationalism

* International Style, a major architectur ...

during the conflict, and whether it was possible to advocate antimilitarism

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (espec ...

during that period (early 1916). As explained above, Kropotkin took firmly pro-war positions during these communiques, as he was predisposed to frequently criticize the German Empire.

Anarchist response to the War and Kropotkin

Unprepared by what historian Max Nettlau called the "explosive imminence" of the First World War at its outbreak in August 1914, anarchists resigned themselves to the reality of the situation and, after a time, began themselves to take sides. Like all nationals, the anarchists had been conditioned to react to the political interests of their nations, whose influence left few unaffected. On the climate of the time, Nettlau remarked: "The air was saturated with accepted nations, conventional opinions and the peculiar illusions which people entertained concerning small nationalities and the virtues and defects of certain races. There were all sorts of plausible justifications for imperialism, for financial controls and so on. And, since Tolstoy had been dead since 1910, no voice of libertarian and moral power was heard in the world: no organisation, large or small, spoke up." European anarchist activity was restricted both physically and by the internal divisions within the anarchist movement over attitudes towards the war. The November 1914 issue of ''Freedom'' featured articles supporting the Allied cause from anarchists including Kropotkin, Jean Grave, Warlaam Tcherkesoff and Verleben as well as a rebuttal to Kropotkin's "A Letter to Steffen", entitled "Anarchists have forgotten their Principles", by Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta. In the following weeks, numerous letters critical of Kropotkin were sent to ''Freedom'', and in turn published due to the editorial impartiality of the newspaper's editor, Thomas Keell. Responding to the criticism, Kropotkin became enraged at Keell for not rejecting such letters, denouncing him as a coward unworthy of his role as editor. A meeting was later called by members of ''Freedom'' who supported Kropotkin's pro-war position and called for the paper to be suspended. Keell, the only anti-war anarchist called to attend, rejected the demand, ending the meeting in hostile disagreement. As a result, Kropotkin's connection with ''Freedom'' ended and the paper continued to be published as an organ for the majority of anti-war ''Freedom'' members. By 1916, the Great War had been ongoing for almost two years, during which anarchists had taken part in anti-war movements across Europe, issuing numerous anti-war statements in anarchist and leftist publications. In February 1915, a statement was issued by an assembly of anarchists from various regions, including England, Switzerland, Italy, the United States, Russia, France, and the Netherlands. The document was signed by such figures asDomela Nieuwenhuis

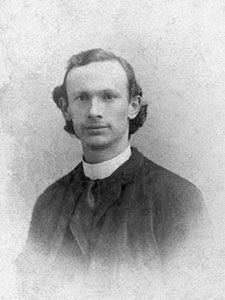

Ferdinand Jacobus Domela Nieuwenhuis (31 December 1846 – 18 November 1919) was a Dutch socialist politician and later a social anarchist and anti-militarist. He was a Lutheran preacher who, after he lost his faith, started a political fight ...

, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

Be ...

, Luigi Bertoni

Luigi Bertoni (1872–1947) was an Italian-born anarchist writer and typographer.

Bertoni fought on the Huesca front with Italian comrades during the Spanish Revolution and was, with Emma Goldman, one of the outspoken critics of anarchist ...

, Saul Yanovsky, Harry Kelly, Thomas Keell, Lilian Wolfe, Rudolf Rocker

Johann Rudolf Rocker (March 25, 1873 – September 19, 1958) was a German anarchist writer and activist. He was born in Mainz to a Roman Catholic artisan family.

His father died when he was a child, and his mother when he was in his teens, so he ...

, and George Barrett. It was also endorsed by Errico Malatesta and Alexander Schapiro, two of three secretaries elected to their position at the Anarchist International of 1907. It set out several viewpoints, including that all wars were the result of the current system of society, and therefore not the blame of any particular government; did not regard a defensive and offensive war as being fundamentally distinctly different; and encouraged all anarchists to support only class conflict and the liberation of oppressed populaces as a means by which to resolve wars between nation-states.

As a result of their increasing isolation from the majority of anti-war anarchists, George Woodcock notes that Kropotkin and anarchists who supported his position drew closer together in the months that preceded the ''Manifestos creation. Several of these same men would later sign the ''Manifesto'', including Jean Grave

Jean Grave (; October 16, 1854, Le Breuil-sur-Couze – December 8, 1939, Vienne-en-Val) was an important activist in the French anarchist and the international anarchist communism movements. He was the editor of three major anarchist periodica ...

, Charles Malato, Paul Reclus, and Christiaan Cornelissen

Christiaan Gerardus Cornelissen (1864–1942) was a Dutch syndicalist writer, economist, and trade unionist.

Further reading

Christianus Gerardus Cornelisseni* ttp://hdl.handle.net/10622/ARCH00340 Archief Christiaan Cornelissen International In ...

.

The ''Manifesto''

Conception and publication

As he was unable to travel during 1916, Kropotkin found himself in frequent correspondence with others, including Jean Grave, who visited Kropotkin from France with his wife. Together, they discussed the war and Kropotkin's firm support for it. At Kropotkin's suggestion that he would like to have been a combatant were he younger, Grave suggested publishing a document urging anarchists to support the war effort on the side of the Allied Powers. Initially hesitant, due to his personal inability to sign up for active duty, Kropotkin was eventually persuaded by Grave. Exactly what part each played in the authorship is unknown. At the time, Grave asserted that he had authored the manifesto and that Kropotkin had revised it. Alternatively, Grigorii Maksimov reported that Kropotkin had written the document and that Grave had merely advised minor alterations. George Woodcock noted that the work seems to be highly influenced by Kropotkin's common concerns and arguments against the German Empire, and so felt that the exact authorship was unimportant. The ''Manifesto'', which would be given its famous name at a later point, dates from February 28, 1916 and was first published in ''La Bataille'' on March 14. ''La Bataille'' was a controversial socialist periodical known for its support of the war, and was accused of being a front for government propaganda by Marxist groups as a result.Contents

The original statement, ten paragraphs in length, includes philosophical and ideological premises based upon the opinions of Peter Kropotkin. The essay begins by declaring that anarchists had correctly resisted the war from its inception, and that the authors would prefer a peace brought about by an international conference of European workers. It then submits that German workers would most likely also favor such a conclusion to the war, and presents several reasons why it would be in their best interest to call for anarmistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

. These reasons were that the citizens, after twenty months of war, would understand that they had been deceived into believing they were taking part in a defensive war

A defensive war (german: Verteidigungskrieg) is one of the causes that justify war by the criteria of the Just War tradition. It means a war where at least one nation is mainly trying to defend itself from another, as opposed to a war where both ...

; that they would recognize that the German state had long prepared for such a conflict, and as such it would be inevitably at fault; that the German Empire could not logistically support an occupation of the territory it had captured; and that the individuals living in the occupied territories were free to choose whether or not they would like to be annexed.

Several paragraphs outline potential conditions for an armistice, rejecting any notion that the German Empire has any place in dictating the terms of peace. The authors also insist that the German populace must accept some blame for having not resisted the march to war on the part of the German government. The authors maintain that immediate calls for negotiation would not be favorable, as the German state would potentially dictate the process from a position of diplomatic and military power. Instead, the manifesto proclaims that the war must be continued so that the German state loses its military strength, and by extension, its ability to negotiate.

The authors proclaim that, due to their anti-government, antimilitarist, and internationalist philosophy, supporting the war was an act of "resistance" to the German Empire. The manifesto then concludes that victory over Germany and the overthrow of the Social Democratic Party of Germany and other ruling parties of the German Empire would advance the anarchist goal of the emancipation of Europe and of the German people, and that the authors are prepared to collaborate with Germans to advance this goal.

Signatories and supporters

The manifesto was signed by some of the most eminent anarchists in Europe. The signatories originally numbered fifteen, with the mistaken sixteenth name, "Hussein Dey

Hussein Dey (real name Hüseyin bin Hüseyin; 1765 – 1838; ar, حسين داي) was the last Dey of the Deylik of Algiers.

Early life

He was born either in İzmir or Urla in the Ottoman Empire. He went to Istanbul and joined the Canoneers ...

", being the name of the city in which Antoine Orfila lived. As the manifesto's co-authors, Jean Grave

Jean Grave (; October 16, 1854, Le Breuil-sur-Couze – December 8, 1939, Vienne-en-Val) was an important activist in the French anarchist and the international anarchist communism movements. He was the editor of three major anarchist periodica ...

and Peter Kropotkin were among its first signatories.

From France, the anarcho-syndicalists Christiaan Cornelissen

Christiaan Gerardus Cornelissen (1864–1942) was a Dutch syndicalist writer, economist, and trade unionist.

Further reading

Christianus Gerardus Cornelisseni* ttp://hdl.handle.net/10622/ARCH00340 Archief Christiaan Cornelissen International In ...

and François Le Levé were signatories; Cornelissen was a supporter of the ''union sacrée The Sacred Union (french: Union Sacrée, ) was a political truce in France in which the left-wing agreed, during World War I, not to oppose the government or call any strikes. Made in the name of patriotism, it stood in opposition to the pledge mad ...

'', a truce between the French government and trade unions during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and wrote several anti-German brochures, while the thirty-two-year-old Le Levé later joined the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Another French signatory was Paul Reclus, brother of renowned anarchist Élisée Reclus

Jacques Élisée Reclus (; 15 March 18304 July 1905) was a French geographer, writer and anarchist. He produced his 19-volume masterwork, ''La Nouvelle Géographie universelle, la terre et les hommes'' ("Universal Geography"), over a period of ...

, whose endorsement of the war and manifesto convinced Japanese anarchist Sanshirō Ishikawa (who was staying with Reclus) to sign. Ishikawa signed the paper as "Tchikawa".

Varlam Cherkezishvili (who signed in the Russian manner as "Warlaam Tcherkesoff"), a Georgian

Georgian may refer to:

Common meanings

* Anything related to, or originating from Georgia (country)

** Georgians, an indigenous Caucasian ethnic group

** Georgian language, a Kartvelian language spoken by Georgians

**Georgian scripts, three scrip ...

anarchist, Marxist critic, and journalist was another noteworthy signatory. The remaining signatories of the initial publication of the document were , , Charles-Ange Laisant

Charles-Ange Laisant (1 November 1841 – 5 May 1920), French politician and mathematician, was born at Indre, near Nantes on 1 November 1841, and was educated at the École Polytechnique as a military engineer. He was a Freemason and a liberta ...

, Charles Malato, , Antoine Orfila, and Ph. Richard. James Guillaume

James Guillaume (February 16, 1844, London – November 20, 1916, Paris) was a leading member of the Jura federation, the anarchist wing of the First International. Later, Guillaume would take an active role in the founding of the Anarchist St. I ...

, although a supporter of the war, was for reasons unknown not an initial signatory. The manifesto was countersigned by approximately one hundred other anarchists, half of whom were Italian anarchists

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

.

Impact and legacy

The publication of the ''Manifesto'' was met with great disapproval by the international anarchist movement, and in considering its impact, George Woodcock stated that it "merely confirmed the split which existed in the anarchist movement." The signatories of the ''Manifesto'' saw the First World War as a battle between German imperialism and the international working class. In contrast, most anarchists of the time, including Emma Goldman andAlexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

Be ...

, saw the war as being that of different capitalist-imperialist states at the expense of the working class. The number of supporters of Kropotkin's position peaked at perhaps 100 or so, while the overwhelming majority of anarchists embraced Goldman's and Berkman's views.

Alongside the reprinted manifesto in the letter columns of '' Freedom'' in April 1916 was a prepared response by Errico Malatesta. Malatesta's response, titled "Governmental Anarchists", recognized the "good faith and good intentions" of the signatories but accused them of having betrayed anarchist principles. Malatesta was soon joined in denunciation by others, including Luigi Fabbri, Sébastien Faure

Sébastien Faure (6 January 1858 – 14 July 1942) was a French anarchist, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

Biography

Before becoming a free-thinker, Faure was a seminarist. He engage ...

, and Emma Goldman:

As a result of his firm support of the war, Kropotkin's popularity dwindled, and many former friends cut ties with him. Two exceptions included Rudolf Rocker and Alexander Schapiro, but both were serving prison sentences at the time. As a result, Kropotkin became increasingly isolated during his final years in London prior to his return to Russia. In ''Peter Kropotkin: His Federalist Ideas'' (1922), an overview of Kropotkin's writings by

As a result of his firm support of the war, Kropotkin's popularity dwindled, and many former friends cut ties with him. Two exceptions included Rudolf Rocker and Alexander Schapiro, but both were serving prison sentences at the time. As a result, Kropotkin became increasingly isolated during his final years in London prior to his return to Russia. In ''Peter Kropotkin: His Federalist Ideas'' (1922), an overview of Kropotkin's writings by Camillo Berneri

Camillo Berneri (also known as Camillo da Lodi; May 28, 1897 – May 5, 1937) was an Italian professor of philosophy, anarchist militant, propagandist and theorist. He was married to Giovanna Berneri, and was father of Marie-Louise Berneri a ...

, the author interjected criticism of the former's militarism. Berneri wrote, "with his pro-war attitude Kropotkin separated himself from anarchism," and asserted that the ''Manifesto of the Sixteen'' "marks the culmination of incoherence in the pro-war anarchists; ropotkinalso supported Kerensky in Russia on the question of prosecuting the war." Anarchist scholar Vernon Richards

Vernon Richards (born Vero Benvenuto Costantino Recchioni, 19 July 1915 – 10 December 2001) was an Anglo-Italian anarchist, editor, author, engineer, photographer, and companion of Marie-Louise Berneri.

Richards' founding of the paper ''Spai ...

speculates that were it not for the desire of '' Freedom'' editor Thomas Keell (himself staunchly anti-war) to give the supporters of the war a fair hearing from the start, they might have found themselves politically isolated far earlier.

Russia

HistorianPaul Avrich

Paul Avrich (August 4, 1931 – February 16, 2006) was a historian of the 19th and early 20th century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his entire career, from 19 ...

describes the fallout over the support for the war an "almost fatal" division in the Russian anarchist movement. Muscovite

Muscovite (also known as common mica, isinglass, or potash mica) is a hydrated phyllosilicate mineral of aluminium and potassium with formula K Al2(Al Si3 O10)( F,O H)2, or ( KF)2( Al2O3)3( SiO2)6( H2O). It has a highly perfect basal cleavag ...

anarchists split into two groups, with the larger faction supporting Kropotkin and his "defensist" associates; the smaller anti-war faction responded by abandoning Kropotkinite anarchist communism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains res ...

for anarcho-syndicalism. In spite of this, the anarchist movement in Russia continued to gain strength. In an article published in a December 1916 issue of ''The State and Revolution

''The State and Revolution'' (1917) is a book by Vladimir Lenin describing the role of the state in society, the necessity of proletarian revolution, and the theoretic inadequacies of social democracy in achieving revolution to establish the dicta ...

'', Bolshevik leader Lenin accused the vast majority of Russian anarchists of following Kropotkin and Grave, and denounced them as "anarcho-chauvinists". Similar remarks were made by other Bolsheviks, such as Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, who wrote in a letter to a Communist leader, "I have recently read Kropotkin's articlesthe old fool must have completely lost his mind". Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

cited Kropotkin's support for the war and his manifesto while further denouncing anarchism:

Historian George Woodcock characterized these criticisms as acceptable insofar as they focused on Kropotkin's militarism. However, he found the criticisms of Russian anarchists to be "unjustified", and regarding accusations that Russian anarchists embraced Kropotkin and Grave's message, Woodcock stated, "nothing of the kind happened; only about a hundred anarchists signed the various pronouncements in support of the war; the majority in all countries maintained the anti-militarist position as consistently as the Bolsheviks."

Switzerland and Spain

InGeneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

, an angry group of "internationalists" – Grossman-Roštšin, Alexander Ghe and Kropotkin's disciple K. Orgeiani among them – labeled the anarchist champions of the war "Anarcho-Patriots". They maintained that the only form of war acceptable to true anarchists was the social revolution that would overthrow the bourgeoisie and their oppressive institutions. Jean Wintsch, founder of the Ferrer School of Lausanne and editor of ''La libre fédération'', was isolated from the Swiss anarchist movement when he aligned himself with the ''Manifesto'' and its signatories.

The Spanish anarcho-syndicalists, who opposed the war out of doctrinaire cynicism and a belief that neither faction were on the workers' side, angrily repudiated their former idols (including Kropotkin, Malato and Grave) after discovering they had authored the manifesto. A small number of anarchists in Galicia and Asturias dissented and were heatedly denounced by the majority of Catalan anarcho-syndicalists (who prevailed in the anarchist union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo ( en, National Confederation of Labor; CNT) is a Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionar ...

).

See also

*Anarchism and violence

Anarchism and violence have been linked together by events in anarchist history such as violent revolution, terrorism, assassination attempts and propaganda of the deed. Propaganda of the deed, or ''attentát'', was espoused by leading anarchis ...

* Opposition to World War I

Opposition to World War I included socialist, anarchist, syndicalist, and Marxist groups on the left, as well as Christian pacifists, Canadian and Irish nationalists, women's groups, intellectuals, and rural folk.

The socialist movements had ...

Footnotes

. In her autobiography, ''Living My Life'', Emma Goldman recalled numerous anarchists from the warring nations of Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Germany, who she contrasted with Kropotkin for their anti-war stance during World War I. Among those in Britain, she listed Errico Malatesta, Rudolf Rocker, Alexander Schapiro, Thomas H. Keell, and "other native & Jewish-speaking anarchists". In France, she noted Sébastien Faure, "A. Armand" (E. Armand? — ed.), and "members of the anarchist & syndicalist movements". From the Netherlands she counted Domela Nieuwenhuis and "his co-workers". And of Germany, she listed Gustav Landauer, Erich Mühsam, Fritz Oerter, Fritz Kater, and "scores of other comrades".References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

''Manifeste des seize'' and responses to the ''Manifesto''

, archived January 21, 2001

at the Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia {{DEFAULTSORT:Manifesto Of The Sixteen Anarchist manifestos Cultural history of World War I History of anarchism Politics of World War I World War I publications Anarchism in Russia 1916 in politics 1916 documents