Malcolm Fraser on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

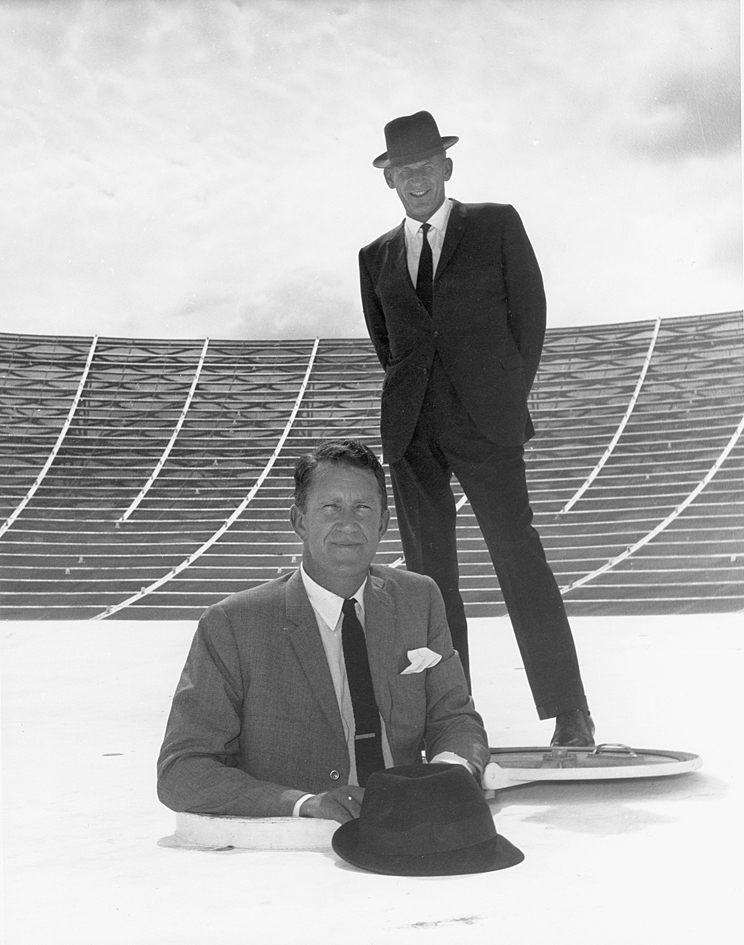

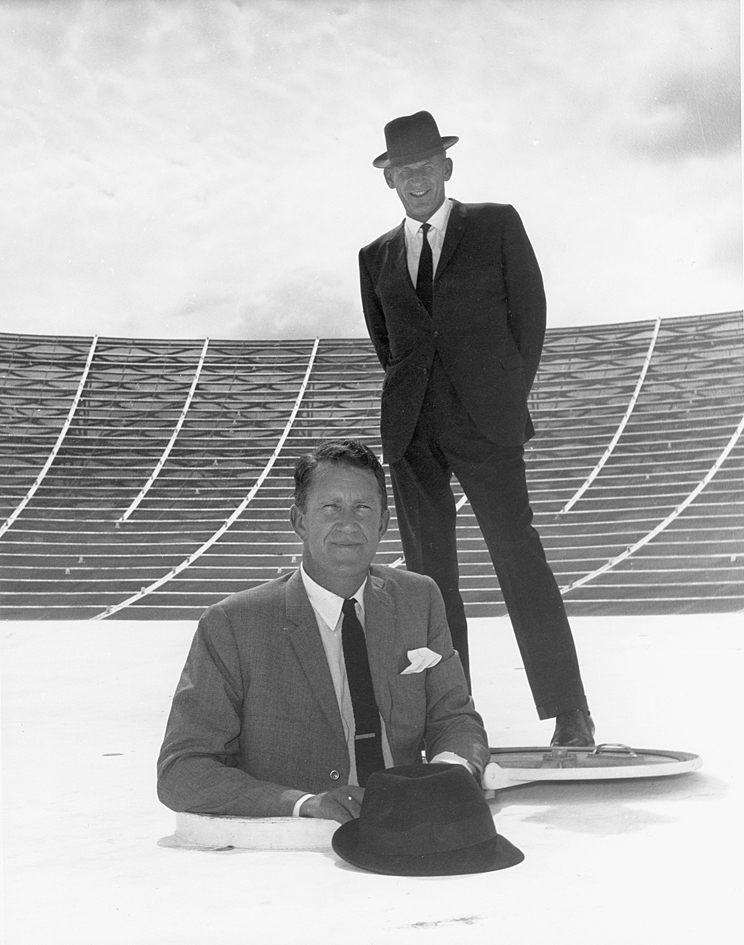

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd

Fraser took his seat in parliament at the age of 25 – the youngest sitting MP by four years, and the first who had been too young to serve in World War II. He was re-elected at the 1958 election despite being restricted in his campaigning by a bout of hepatitis. Fraser was soon being touted as a future member of cabinet, but despite good relations with

Fraser took his seat in parliament at the age of 25 – the youngest sitting MP by four years, and the first who had been too young to serve in World War II. He was re-elected at the 1958 election despite being restricted in his campaigning by a bout of hepatitis. Fraser was soon being touted as a future member of cabinet, but despite good relations with

In 1966, after more than a decade on the backbench, Sir Robert Menzies retired as Prime Minister. His successor

In 1966, after more than a decade on the backbench, Sir Robert Menzies retired as Prime Minister. His successor

At the 1975 election, Fraser led the Liberal-Country Party Coalition to a landslide victory. The Coalition won 91 seats of a possible 127 in the election to gain a 55-seat majority, which remains to date the largest in Australian history. Fraser subsequently led the Coalition to a second victory in

At the 1975 election, Fraser led the Liberal-Country Party Coalition to a landslide victory. The Coalition won 91 seats of a possible 127 in the election to gain a 55-seat majority, which remains to date the largest in Australian history. Fraser subsequently led the Coalition to a second victory in

Fraser quickly dismantled some of the programs of the Whitlam Government, such as the Ministry of the Media, and made major changes to the universal health insurance system

Fraser quickly dismantled some of the programs of the Whitlam Government, such as the Ministry of the Media, and made major changes to the universal health insurance system

At the 1980 election, Fraser saw his majority more than halved, from 48 seats to 21. The Coalition also lost control of the Senate. Despite this, Fraser remained ahead of Labor leader

At the 1980 election, Fraser saw his majority more than halved, from 48 seats to 21. The Coalition also lost control of the Senate. Despite this, Fraser remained ahead of Labor leader

By early 1982, the popular former ACTU President,

By early 1982, the popular former ACTU President,

In 1993, Fraser made a bid for the Liberal Party presidency but withdrew at the last minute following opposition to his bid, which was raised due to his having been critical of then Liberal leader

In 1993, Fraser made a bid for the Liberal Party presidency but withdrew at the last minute following opposition to his bid, which was raised due to his having been critical of then Liberal leader

In December 2011, Fraser was highly critical of the Australian government's decision (also supported by the Liberal Party Opposition) to permit the export of uranium to India, relaxing the Fraser government's policy of banning sales of uranium to countries that are not signatories of the

In December 2011, Fraser was highly critical of the Australian government's decision (also supported by the Liberal Party Opposition) to permit the export of uranium to India, relaxing the Fraser government's policy of banning sales of uranium to countries that are not signatories of the

On 9 December 1956, Fraser married Tamara "Tamie" Beggs, who was almost six years his junior. They had met at a New Year's Eve party, and bonded over similar personal backgrounds and political views. The couple had four children together: Mark (b. 1958), Angela (b. 1959), Hugh (b. 1963), and Phoebe (b. 1966). Tamie frequently assisted her husband in campaigning, and her gregariousness was seen as complementing his more shy and reserved nature. She advised him on most of the important decisions in his career, and in retirement he observed that "if she had been prime minister in 1983, we would have won".

On 9 December 1956, Fraser married Tamara "Tamie" Beggs, who was almost six years his junior. They had met at a New Year's Eve party, and bonded over similar personal backgrounds and political views. The couple had four children together: Mark (b. 1958), Angela (b. 1959), Hugh (b. 1963), and Phoebe (b. 1966). Tamie frequently assisted her husband in campaigning, and her gregariousness was seen as complementing his more shy and reserved nature. She advised him on most of the important decisions in his career, and in retirement he observed that "if she had been prime minister in 1983, we would have won".

Sentiments on Australia’s influential political figures

The Australian, 12 March 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2019. Fraser was given a state funeral at Scots' Church in Melbourne on 27 March 2015. His ashes are interred within the Prime Ministers Garden of

"Former Aust PM awarded top honour"

''The National'', 31 December 2009

Organisations

* 2000

Malcolm Fraser

�� Australia's Prime Ministers / National Archives of Australia

Australian Biography– Malcolm Fraser

An extensive 1994 interview with Fraser

The Malcolm Fraser Collection at the University of Melbourne ArchivesMalcolm Fraser at the National Film and Sound Archive

* ttp://www.theage.com.au/news/opinion/malcolm-fraser/2008/05/09/1210131260171.html Balanced policy the only way to peace: Malcolm Fraser– The Age 10/05/2008 {{DEFAULTSORT:Fraser, Malcolm 1930 births 2015 deaths 1975 Australian constitutional crisis Alumni of Magdalen College, Oxford American Enterprise Institute Australian Leaders of the Opposition Australian people of Canadian descent Australian people of English-Jewish descent Australian people of New Zealand descent Australian people of Scottish descent Australian pastoralists Australian republicans Australian agnostics Australian former Christians Companions of the Order of Australia Grand Companions of the Order of Logohu Liberal Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia Australian Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Wannon Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom People educated at Geelong Grammar School People educated at Melbourne Grammar School Politicians from Melbourne Prime Ministers of Australia Grand Cordons of the Order of the Rising Sun Defence ministers of Australia Leaders of the Liberal Party of Australia Fellows of the Royal Commonwealth Society 20th-century Australian politicians Government ministers of Australia Australian memoirists Burials at Melbourne General Cemetery

prime minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the federal government of Australia and is also accountable to federal parliament under the princip ...

from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is a centre-right political party in Australia, one of the two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-left Australian Labor Party. It was founded in 1944 as the successor to the United A ...

.

Fraser was raised on his father's sheep stations, and after studying at Magdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College (, ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1458 by William of Waynflete. Today, it is the fourth wealthiest college, with a financial endowment of £332.1 million as of 2019 and one of the ...

, returned to Australia to take over the family property in the Western District of Victoria. After an initial defeat in 1954, he was elected to the Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Senate. Its composition and powers are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

The term of members of ...

at the 1955 federal election, as a member of parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for the division of Wannon

The Division of Wannon is an Australian Electoral Division in the state of Victoria.

History

The division was proclaimed in 1900, and was one of the original 65 divisions to be contested at the first Federal election. The division was nam ...

. He was 25 at the time, making him one of the youngest people ever elected to parliament. When Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt (5 August 190817 December 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Australia from 1966 until his presumed death in 1967. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party.

Holt was born in ...

became prime minister in 1966, Fraser was appointed Minister for the Army. After Holt's disappearance and replacement by John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

, Fraser became Minister for Education and Science (1968–1969) and then Minister for Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

(1969–1971). In 1971, Fraser resigned from cabinet and denounced Gorton as "unfit to hold the great office of prime minister"; this precipitated the replacement of Gorton with William McMahon

Sir William McMahon (23 February 190831 March 1988) was an Australian politician who served as the 20th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1971 to 1972 as leader of the Liberal Party. He was a government minister for over 21 years, ...

. He subsequently returned to his old education and science portfolio.

After the Liberal-National Coalition

The Liberal–National Coalition, commonly known simply as "the Coalition" or informally as the LNP, is an alliance of centre-right political parties that forms one of the two major groupings in Australian federal politics. The two partners in ...

was defeated at the 1972 election, Fraser unsuccessfully stood for the Liberal leadership, losing to Billy Snedden

Sir Billy Mackie Snedden, (31 December 1926 – 27 June 1987) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Liberal Party from 1972 to 1975. He was also a cabinet minister from 1964 to 1972, and Speaker of the House of Repres ...

. When the party lost the 1974 election, he began to move against Snedden, eventually mounting a successful challenge in March 1975. As Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, Fraser used the Coalition's control of the Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia. There are a t ...

to block supply

Supply may refer to:

*The amount of a resource that is available

**Supply (economics), the amount of a product which is available to customers

**Materiel, the goods and equipment for a military unit to fulfill its mission

*Supply, as in confidenc ...

to the Whitlam Government, precipitating the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis

The 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, also known simply as the Dismissal, culminated on 11 November 1975 with the dismissal from office of the prime minister, Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), by Governor-General Sir ...

. This culminated with Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the h ...

being dismissed as prime minister by the governor-general

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

, Sir John Kerr

Sir John Robert Kerr (24 September 1914 – 24 March 1991) was an Australian barrister and judge who served as the 18th Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1974 to 1977. He is primarily known for his involvement in the 1975 constit ...

, a unique occurrence in Australian history. The correctness of Fraser's actions in the crisis and the exact nature of his involvement in Kerr's decision have since been a topic of debate. Fraser remains the only Australian prime minister to ascend to the position upon the dismissal of his predecessor.

After Whitlam's dismissal, Fraser was sworn in as prime minister on an initial caretaker basis. The Coalition won a landslide victory

A landslide victory is an election result in which the victorious candidate or party wins by an overwhelming margin. The term became popular in the 1800s to describe a victory in which the opposition is "buried", similar to the way in which a geol ...

at the 1975 election, and was re-elected in 1977 and 1980

Events January

* January 4 – U.S. President Jimmy Carter proclaims a grain embargo against the USSR with the support of the European Commission.

* January 6 – Global Positioning System time epoch begins at 00:00 UTC.

* January 9 – In ...

. Fraser took a keen interest in foreign affairs as prime minister, and was more active in the international sphere than many of his predecessors. He was a strong supporter of multiculturalism

The term multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and in everyday usage, it is a synonym for " ethnic pluralism", with the two terms often used interchang ...

, and during his term in office Australia admitted significant numbers of non-white immigrants (including Vietnamese boat people) for the first time, effectively ending the White Australia policy

The White Australia policy is a term encapsulating a set of historical policies that aimed to forbid people of non-European ethnic origin, especially Asians (primarily Chinese) and Pacific Islanders, from immigrating to Australia, starting i ...

. His government also established the Special Broadcasting Service

The Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) is an Australian hybrid-funded public service broadcaster. About 80 percent of funding for the company is derived from the Australian Government. SBS operates six TV channels ( SBS, SBS Viceland, SBS Wor ...

(SBS). Particularly in his final years in office, Fraser came into conflict with the "dry" economic rationalist and fiscal conservative faction of his party. His government made few major changes to economic policy.

After losing the 1983 election, Fraser retired from politics. In his post-political career, he held advisory positions with the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

(UN) and the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the C ...

, and was president of the aid agency CARE

Care may refer to:

Organizations and projects

* CARE (New Zealand), Citizens Association for Racial Equality, a former New Zealand organisation

* CARE (relief agency), "Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere", an international aid and ...

from 1990 to 1995. He resigned his membership of the Liberal Party in 2009 after the election of Tony Abbott

Anthony John Abbott (; born 4 November 1957) is a former Australian politician who served as the 28th prime minister of Australia from 2013 to 2015. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Abbott was born in Londo ...

as leader, Fraser having been a critic of the Liberals’ policy direction for a number of years. Evaluations of Fraser's prime ministership have been mixed. He is generally credited with restoring stability to the country after a series of short-term leaders and has been praised for his commitment to multiculturalism and opposition to apartheid, but the circumstances of his entry to office remains controversial and many have viewed his government as a lost opportunity for economic reform. His seven and a half-year tenure as prime minister is the fourth longest in Australian history, only surpassed by Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

, John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

and Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

.

Early life

Birth and family background

John Malcolm Fraser was born in Toorak, Melbourne, Victoria, on 21 May 1930. He was the second of two children born to Una Arnold (née Woolf) and John Neville Fraser; his older sister Lorraine had been born in 1928. Both he and his father were known exclusively by their middle names. His paternal grandfather, Sir Simon Fraser, was born inNova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, Canada, and arrived in Australia in 1853. He made his fortune as a railway contractor, and later acquired significant pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depict ...

holdings, becoming a member of the " squattocracy". Fraser's maternal grandfather, Louis Woolf, was born in Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

, New Zealand, and arrived in Australia as a child. He was of Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

origin, a fact which his grandson did not learn until he was an adult. A chartered accountant by trade, he married Amy Booth, who was related to the wealthy Hordern family of Sydney and was a first cousin of Sir Samuel Hordern.

Fraser had a political background on both sides of his family. His father served on the Wakool Shire Council, including as president for two years, and was an admirer of Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

and a friend of Richard Casey. Simon Fraser served in both houses of the colonial Parliament of Victoria

The Parliament of Victoria is the bicameral legislature of the Australian state of Victoria that follows a Westminster-derived parliamentary system. It consists of the King, represented by the Governor of Victoria, the Legislative Assembly an ...

, and represented Victoria at several of the constitutional conventions of the 1890s. He eventually become one of the inaugural members of the new federal Senate, serving from 1901 to 1913 as a member of the early conservative parties. Louis Woolf also ran for the Senate in 1901, standing as a Free Trader in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

. He polled only 400 votes across the whole state, and was never again a candidate for public office.

Childhood

Fraser spent most of his early life at ''Balpool-Nyang'', a sheep station of on theEdward River

Edward River, or Kyalite River, an anabranch of the Murray River and part of the Murray–Darling basin, is located in the western Riverina region of south western New South Wales, Australia.

The river rises at Picnic Point east of Mathoura, ...

near Moulamein, New South Wales

Moulamein is a small town in New South Wales, Australia, in the Murray River Council local government area. At the , Moulamein had a population of 484 . Moulamein is the oldest town in the Riverina.

The town is located between Balranald, Ha ...

. His father had a law degree from Magdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College (, ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1458 by William of Waynflete. Today, it is the fourth wealthiest college, with a financial endowment of £332.1 million as of 2019 and one of the ...

, but never practised law and preferred the life of a grazier. Fraser contracted a severe case of pneumonia when he was eight years old, which nearly proved fatal. He was home-schooled until the age of ten, when he was sent to board at Tudor House School

, established = 1897, relocated in 1901

, type = Independent, co-educational since 2017, primary, day and boarding

, denomination = Anglican

, slogan = Learning for life

, coordinates =

, head of school = Anni Sandwell

, found ...

in the Southern Highlands. He attended Tudor House from 1940 to 1943, and then completed his secondary education at Melbourne Grammar School

(Pray and Work)

, established = 1849 (on present site since 1858 - the celebrated date of foundation)

, type = Independent, co-educational primary, single-sex boys secondary, day and boarding

, denomination ...

from 1944 to 1948 where he was a member of Rusden House. While at Melbourne Grammar, he lived in a flat that his parents owned on Collins Street. In 1943, Fraser's father sold ''Balpool-Nyang'' – which had been prone to drought – and bought ''Nareen'', in the Western District of Victoria. He was devastated by the sale of his childhood home, and regarded the day he found out about it as the worst of his life.

University

In 1949, Fraser moved to England to study atMagdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College (, ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1458 by William of Waynflete. Today, it is the fourth wealthiest college, with a financial endowment of £332.1 million as of 2019 and one of the ...

, which his father had also attended. He read Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE), graduating in 1952 with third-class honours. Although Fraser did not excel academically, he regarded his time at Oxford as his intellectual awakening, where he learned "how to think". His college tutor

TUTOR, also known as PLATO Author Language, is a programming language developed for use on the PLATO system at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign beginning in roughly 1965. TUTOR was initially designed by Paul Tenczar for use in ...

was Harry Weldon, who was a strong influence. His circle of friends at Oxford included Raymond Bonham Carter

Raymond Henry Bonham Carter (19 June 1929 – 17 January 2004) was a British banker and a member of the prominent Bonham Carter family.

Early life

He was born in Paddington, London, to Sir Maurice Bonham-Carter (1880–1960), a politician and ...

, Nicolas Browne-Wilkinson, and John Turner

John Napier Wyndham Turner (June 7, 1929September 19, 2020) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Canada from June to September 1984. He served as leader of the Liberal Party of Canada and leader of t ...

. In his second year, he had a relationship with Anne Reid, who as Anne Fairbairn later became a prominent poet. After graduating, Fraser considered taking a law degree or joining the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

, but eventually decided to return to Australia and take over the running of the family property.

Early political career

Fraser returned to Australia in mid-1952. He began attending meetings of the Young Liberals inHamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilto ...

, and became acquainted with many of the local party officials. In November 1953, aged 23, Fraser unexpectedly won Liberal preselection

Preselection is the process by which a candidate is selected, usually by a political party, to contest an election for political office. It is also referred to as candidate selection. It is a fundamental function of political parties. The presele ...

for the Division of Wannon

The Division of Wannon is an Australian Electoral Division in the state of Victoria.

History

The division was proclaimed in 1900, and was one of the original 65 divisions to be contested at the first Federal election. The division was nam ...

, which covered most of Victoria's Western District. The previous Liberal member, Dan Mackinnon

Ewen Daniel Mackinnon (11 February 1903 – 7 June 1983) was an Australian politician. The son of state MLA Donald Mackinnon, he was born in Melbourne and educated at Geelong Grammar School and then attended Oxford University. He returned to ...

, had been defeated in 1951 and moved to a different electorate. He was expected to be succeeded by Magnus Cormack, who had recently lost his place in the Senate. Fraser had put his name forward as a way of building a profile for future candidacies, but mounted a strong campaign and in the end won a narrow victory. In January 1954, he made the first of a series of weekly radio broadcasts on 3HA

Ace Radio Broadcasters is an Australian media company. Formed in 1984, it operates 21 commercial radio stations in Victoria and southern New South Wales, as well as the digital marketing agency Ace Digital and ''The Weekly Advertiser'', a free ...

Hamilton and 3YB

3YB FM is a radio broadcaster based in Warrnambool, Victoria, Australia. It transmits on the frequency modulation radio band, at a frequency of 94.5 MHz. The station is part of the Ace Radio FM network. It has an adult contemporary music fo ...

Warrnambool, titled ''One Australia''. His program – consisting of a pre-recorded 15-minute monologue – covered a wide range of topics, and was often reprinted in newspapers. It continued more or less uninterrupted until his retirement from politics in 1983, and helped him build a substantial personal following in his electorate.

At the 1954 election, Fraser lost to the sitting Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

member Don McLeod

Donald Martin "Smokey" McLeod (August 24, 1946 – March 11, 2015) was a Canadian professional ice hockey goaltender who played briefly in the National Hockey League and six full seasons in the World Hockey Association between 1970 and 1978.

Pl ...

by just 17 votes (out of over 37,000 cast). However, he reprised his candidacy at the early 1955 election after a redistribution made Wannon notionally Liberal. McLeod concluded the reconfigured Wannon was unwinnable and retired. These factors, combined with the 1955 Labor Party split, allowed Fraser to win a landslide victory.

Backbencher

Fraser took his seat in parliament at the age of 25 – the youngest sitting MP by four years, and the first who had been too young to serve in World War II. He was re-elected at the 1958 election despite being restricted in his campaigning by a bout of hepatitis. Fraser was soon being touted as a future member of cabinet, but despite good relations with

Fraser took his seat in parliament at the age of 25 – the youngest sitting MP by four years, and the first who had been too young to serve in World War II. He was re-elected at the 1958 election despite being restricted in his campaigning by a bout of hepatitis. Fraser was soon being touted as a future member of cabinet, but despite good relations with Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

never served in cabinet during Menzies' tenure. His long wait for ministerial preferment was probably due to a combination of his youth and the fact that Menzies' ministries already contained a disproportionately high number of Victorians.

Fraser spoke on a wide range of topics during his early years in parliament, but took a particular interest in foreign affairs. In 1964, he and Gough Whitlam were both awarded Leader Grants by the United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

, allowing them to spend two months in Washington, D.C., getting to know American political and military leaders. The Vietnam War was the main topic of conversation, and on his return trip to Australia he spent two days in Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

. Early in 1965, he also made a private seven-day visit to Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

, and with assistance from Ambassador Mick Shann

Sir Keith Charles Owen "Mick" Shann (22 November 1917 – 4 August 1988) was a senior Australian public servant and diplomat.

Life and career

Mick Shann was born in the Melbourne suburb of Kew, Victoria, on 22 November 1917. His father wa ...

secured meetings with various high-ranking officials.

Cabinet Minister and Gorton downfall

In 1966, after more than a decade on the backbench, Sir Robert Menzies retired as Prime Minister. His successor

In 1966, after more than a decade on the backbench, Sir Robert Menzies retired as Prime Minister. His successor Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt (5 August 190817 December 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Australia from 1966 until his presumed death in 1967. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party.

Holt was born in ...

appointed Fraser to the ministry as Minister for the Army. In that position, Fraser presided over the controversial Vietnam War conscription program.

Under the new prime minister, John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

, he was elevated to Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

as Minister for Education and Science. In 1969 he was promoted to Minister for Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

, a particularly challenging post at the time, given the height of Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

and the protests against it.

In March 1971 Fraser abruptly resigned from the Cabinet in protest at what he called Gorton's "interference in (his) ministerial responsibilities", and denounced Gorton on the floor of the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

as "not fit to hold the great office of Prime Minister". This precipitated a series of events which eventually led to the downfall of Gorton and his replacement as prime minister by William McMahon

Sir William McMahon (23 February 190831 March 1988) was an Australian politician who served as the 20th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1971 to 1972 as leader of the Liberal Party. He was a government minister for over 21 years, ...

. In the leadership contest that followed Gorton's resignation, Fraser unsuccessfully contested the deputy Liberal leadership against Gorton and David Fairbairn. Gorton never forgave Fraser for the role he played in his downfall; to the day Gorton died in 2002, he could not bear to be in the same room with Fraser.

Fraser remained on the backbenches until he was reinstated to Cabinet in his old position of Minister for Education and Science by McMahon in August 1971, immediately following Gorton's sacking as deputy Liberal leader by McMahon. When the Liberals were defeated at the 1972 election by the Labor Party under Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the h ...

, McMahon resigned and Fraser became Shadow Minister for Labour under Billy Snedden

Sir Billy Mackie Snedden, (31 December 1926 – 27 June 1987) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Liberal Party from 1972 to 1975. He was also a cabinet minister from 1964 to 1972, and Speaker of the House of Repres ...

.

Opposition (1972–1975)

After the Coalition lost the 1972 election, Fraser was one of five candidates for the Liberal leadership that had been vacated by McMahon. He outpolled John Gorton andJames Killen

Sir Denis James "Jim" Killen, (23 November 1925 – 12 January 2007) was an Australian politician and a Liberal Party member of the Australian House of Representatives from December 1955 to August 1983, representing the Division of Moreton in Q ...

, but was eliminated on the third ballot. Billy Snedden

Sir Billy Mackie Snedden, (31 December 1926 – 27 June 1987) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Liberal Party from 1972 to 1975. He was also a cabinet minister from 1964 to 1972, and Speaker of the House of Repres ...

eventually defeated Nigel Bowen by a single vote on the fifth ballot. In the new shadow cabinet – which featured only Liberals – Fraser was given responsibility for primary industry. This was widely seen as a snub, as the new portfolio kept him mostly out of the public eye and was likely to be given to a member of the Country Party when the Coalition returned to government. In an August 1973 reshuffle, Snedden instead made him the Liberals' spokesman for industrial relations. He had hoped to be given responsibility for foreign affairs (in place of the retiring Nigel Bowen), but that role was given to Andrew Peacock

Andrew Sharp Peacock (13 February 193916 April 2021) was an Australian politician and diplomat. He served as a cabinet minister and went on to become leader of the Liberal Party on two occasions (1983–1985 and 1989–1990), leading the pa ...

.Ayres (1987), p. 213. Fraser oversaw the development of the party's new industrial relations policy, which was released in April 1974. It was seen as more flexible and even-handed than the policy that the Coalition had pursued in government, and was received well by the media. According to Fraser's biographer Philip Ayres, by "putting a new policy in place, he managed to modify his public image and emerge as an excellent communicator across a traditionally hostile divide".

Leader of the Opposition

After the Liberals lost the 1974 election, Fraser unsuccessfully challenged Snedden for the leadership in November. Despite surviving the challenge, Snedden's position in opinion polls continued to decline and he was unable to get the better of Whitlam in the Parliament. Fraser again challenged Snedden on 21 March 1975, this time succeeding and becoming Leader of the Liberal Party andLeader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

.

Role in the Dismissal

Following a series of ministerial scandals engulfing the Whitlam Government later that year, Fraser began to instruct Coalition senators to delay the government's budget bills, with the objective of forcing an early election that he believed he would win. After several months of political deadlock, during which time the government secretly explored methods of obtaining supply funding outside the Parliament, theGovernor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

, Sir John Kerr

Sir John Robert Kerr (24 September 1914 – 24 March 1991) was an Australian barrister and judge who served as the 18th Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1974 to 1977. He is primarily known for his involvement in the 1975 constit ...

, controversially dismissed Whitlam as prime minister on 11 November 1975.

Fraser was immediately sworn in as caretaker prime minister on the condition that he end the political deadlock and call an immediate double dissolution

A double dissolution is a procedure permitted under the Australian Constitution to resolve deadlocks in the bicameral Parliament of Australia between the House of Representatives ( lower house) and the Senate (upper house). A double dissoluti ...

election.

On 19 November 1975, shortly after the election had been called, a letter bomb was sent to Fraser, but it was intercepted and defused before it reached him. Similar devices were sent to the governor-general and the Premier of Queensland

The premier of Queensland is the head of government in the Australian state of Queensland.

By convention the premier is the leader of the party with a parliamentary majority in the unicameral Legislative Assembly of Queensland. The premier is ap ...

, Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

Prime Minister (1975–1983)

1975 and 1977 federal elections

At the 1975 election, Fraser led the Liberal-Country Party Coalition to a landslide victory. The Coalition won 91 seats of a possible 127 in the election to gain a 55-seat majority, which remains to date the largest in Australian history. Fraser subsequently led the Coalition to a second victory in

At the 1975 election, Fraser led the Liberal-Country Party Coalition to a landslide victory. The Coalition won 91 seats of a possible 127 in the election to gain a 55-seat majority, which remains to date the largest in Australian history. Fraser subsequently led the Coalition to a second victory in 1977

Events January

* January 8 – Three bombs explode in Moscow within 37 minutes, killing seven. The bombings are attributed to an Armenian separatist group.

* January 10 – Mount Nyiragongo erupts in eastern Zaire (now the Democrat ...

, with only a very small decrease in their vote. The Liberals actually won a majority in their own right in both of these elections, something that Menzies and Holt had never achieved. Although Fraser thus had no need for the support of the (National) Country Party to govern, he retained the formal Coalition between the two parties.

Fiscal policy

Fraser quickly dismantled some of the programs of the Whitlam Government, such as the Ministry of the Media, and made major changes to the universal health insurance system

Fraser quickly dismantled some of the programs of the Whitlam Government, such as the Ministry of the Media, and made major changes to the universal health insurance system Medibank

Medibank Private Limited, better known as simply Medibank, is one of the largest Australian private health insurance providers, covering 3.7 million people in 2021. Medibank initially started as an Australian Government not-for-profit insurer i ...

. He initially maintained Whitlam's levels of tax and spending, but real per-person tax and spending soon began to increase. He did manage to rein in inflation, which had soared under Whitlam. His so-called "Razor Gang" implemented stringent budget cuts across many areas of the Commonwealth Public Sector, including the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) is the national broadcaster of Australia. It is principally funded by direct grants from the Australian Government and is administered by a government-appointed board. The ABC is a publicly-owne ...

(ABC).

Fraser practised Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

economics during his time as Prime Minister, in part demonstrated by running budget deficits throughout his term as Prime Minister. He was the Liberal Party's last Keynesian Prime Minister. Though he had long been identified with the Liberal Party's right wing, he did not carry out the radically conservative program that his political enemies had predicted, and that some of his followers wanted. Fraser's relatively moderate policies particularly disappointed the Treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

, John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

, as well as other ministers who were strong adherents of fiscal conservatism

Fiscal conservatism is a political and economic philosophy regarding fiscal policy and fiscal responsibility with an ideological basis in capitalism, individualism, limited government, and ''laissez-faire'' economics.M. O. Dickerson et al., '' ...

and economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic libera ...

, and therefore detractors of Keynesian economics. The government's economic record was marred by rising double-digit unemployment and double-digit inflation, creating "stagflation

In economics, stagflation or recession-inflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high or increasing, the economic growth rate slows, and unemployment remains steadily high. It presents a dilemma for economic policy, since actio ...

", caused in part by the ongoing effects of the 1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had su ...

.

Foreign policy

Fraser was particularly active in foreign policy as prime minister. He supported theCommonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

in campaigning to abolish apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

in South Africa and refused permission for the aircraft carrying the Springbok

The springbok (''Antidorcas marsupialis'') is a medium-sized antelope found mainly in south and southwest Africa. The sole member of the genus ''Antidorcas'', this bovid was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm ...

rugby team to refuel on Australian territory en route to their controversial 1981 tour of New Zealand. However, an earlier tour by the South African ski boat angling team was allowed to pass through Australia on the way to New Zealand in 1977 and the transit records were suppressed by Cabinet order.

Fraser also strongly opposed white minority rule in Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

. During the 1979 Commonwealth Conference, Fraser, together with his Nigerian counterpart, convinced the newly elected British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

, to withhold recognition of the internal settlement Zimbabwe Rhodesia

Zimbabwe Rhodesia (), alternatively known as Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, also informally known as Zimbabwe or Rhodesia, and sometimes as Rhobabwe, was a short-lived sovereign state that existed from 1 June to 12 December 1979. Zimbabwe Rhodesia was p ...

government; Thatcher had earlier promised to recognise it. Subsequently, the Lancaster House Agreement was signed and Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of the ...

was elected leader of an independent Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and ...

at the inaugural 1980 election. Duncan Campbell, a former deputy secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has stated that Fraser was "the principal architect" in the ending of white minority rule. The President of Tanzania

The President of the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Rais wa Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania) is the head of state and head of government of the United Republic of Tanzania. The President leads the executive branch of the Government of Ta ...

, Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, af ...

, said that he considered Fraser's role "crucial in many parts" and the President of Zambia, Kenneth Kaunda

Kenneth David Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first President of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from British rule. Diss ...

, called his contribution "vital".

Under Fraser, Australia recognised Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

's annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of East Timor

East Timor (), also known as Timor-Leste (), officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, is an island country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the exclave of Oecusse on the island's north-w ...

, although many East Timorese refugees were granted asylum in Australia

Asylum in Australia has been granted to many refugees since 1945, when half a million Europeans displaced by World War II were given asylum. Since then, there have been periodic waves of asylum seekers from South East Asia and the Middle East ...

.

Fraser was also a strong supporter of the United States and supported the boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics

The 1980 Summer Olympics (russian: Летние Олимпийские игры 1980, Letniye Olimpiyskiye igry 1980), officially known as the Games of the XXII Olympiad (russian: Игры XXII Олимпиады, Igry XXII Olimpiady) and commo ...

in Moscow. However, although he persuaded some sporting bodies not to compete, Fraser did not try to prevent the Australian Olympic Committee

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal Aus ...

sending a team to the Moscow Games.

Other policy

Fraser also surprised his critics over immigration policy; according to 1977 Cabinet documents, the Fraser Government adopted a formal policy for "a humanitarian commitment to admit refugees for resettlement". Fraser's aim was to expand immigration from Asian countries and allow more refugees to enter Australia. He was a firm supporter ofmulticulturalism

The term multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and in everyday usage, it is a synonym for " ethnic pluralism", with the two terms often used interchang ...

and established a government-funded multilingual radio and television network, the Special Broadcasting Service

The Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) is an Australian hybrid-funded public service broadcaster. About 80 percent of funding for the company is derived from the Australian Government. SBS operates six TV channels ( SBS, SBS Viceland, SBS Wor ...

(SBS), building on their first radio stations which had been established under the Whitlam Government.

Despite Fraser's support for SBS, his government imposed stringent budget cuts on the national broadcaster, the ABC, which came under repeated attack from the Coalition for alleged "left-wing bias" and "unfair" coverage on their TV programs, including '' This Day Tonight'' and ''Four Corners

The Four Corners is a region of the Southwestern United States consisting of the southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and northwestern corner of New Mexico. The Four Corners area ...

'', and on the ABC's new youth-oriented radio station Double Jay. One result of the cuts was a plan to establish a national youth radio network, of which Double Jay was the first station. The network was delayed for many years and did not come to fruition until the 1990s.

Fraser also legislated to give Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

control of their traditional lands in the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (commonly abbreviated as NT; formally the Northern Territory of Australia) is an Australian territory in the central and central northern regions of Australia. The Northern Territory shares its borders with Western Aust ...

, but resisted imposing land rights laws on conservative state governments.

1980 federal election

At the 1980 election, Fraser saw his majority more than halved, from 48 seats to 21. The Coalition also lost control of the Senate. Despite this, Fraser remained ahead of Labor leader

At the 1980 election, Fraser saw his majority more than halved, from 48 seats to 21. The Coalition also lost control of the Senate. Despite this, Fraser remained ahead of Labor leader Bill Hayden

William George Hayden (born 23 January 1933) is an Australian politician who served as the 21st governor-general of Australia from 1989 to 1996. He was Leader of the Labor Party and Leader of the Opposition from 1977 to 1983, and served as ...

in opinion polls. However, the economy was hit by the early 1980s recession, and a protracted scandal over tax-avoidance schemes run by some high-profile Liberals also began to hurt the Government.

Disputes within the Liberal Party

In April 1981, the Minister for Industrial Relations,Andrew Peacock

Andrew Sharp Peacock (13 February 193916 April 2021) was an Australian politician and diplomat. He served as a cabinet minister and went on to become leader of the Liberal Party on two occasions (1983–1985 and 1989–1990), leading the pa ...

, resigned from the Cabinet, accusing Fraser of "constant interference in his portfolio". Fraser, however, had accused former prime minister John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

of the same thing a decade earlier. Peacock subsequently challenged Fraser for the leadership; although Fraser defeated Peacock, these events left him politically weakened.

Labor Party and 1983 federal election

Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

, who had entered Parliament in 1980, was polling well ahead of both Fraser and the Labor Leader, Bill Hayden

William George Hayden (born 23 January 1933) is an Australian politician who served as the 21st governor-general of Australia from 1989 to 1996. He was Leader of the Labor Party and Leader of the Opposition from 1977 to 1983, and served as ...

, on the question of who voters would rather see as prime minister. Fraser was well aware of the infighting this caused between Hayden and Hawke and had planned to call a snap election in autumn 1982, preventing the Labor Party changing leaders. These plans were derailed when Fraser suffered a severe back injury. Shortly after recovering from his injury, the Liberal Party narrowly won a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election ( Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to ...

in the marginal seat of Flinders in December 1982. The failure of the Labor Party to win the seat convinced Fraser that he would be able to win an election against Hayden.

As leadership tensions began to grow in the Labor Party throughout January, Fraser subsequently resolved to call a double dissolution

A double dissolution is a procedure permitted under the Australian Constitution to resolve deadlocks in the bicameral Parliament of Australia between the House of Representatives ( lower house) and the Senate (upper house). A double dissoluti ...

election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operat ...

at the earliest opportunity, hoping to capitalise on Labor's disunity. He knew that if the writs were issued soon enough, Labor would essentially be frozen into going into the subsequent election with Hayden as leader.

On 3 February 1983, Fraser arranged to visit the Governor-General of Australia

The governor-general of Australia is the representative of the monarch, currently King Charles III, in Australia.Sir Ninian Stephen

Sir Ninian Martin Stephen (15 June 1923 – 29 October 2017) was an Australian judge who served as the 20th governor-general of Australia, in office from 1982 to 1989. He was previously a justice of the High Court of Australia from 1972 to 198 ...

, intending to ask for a surprise election. However, Fraser made his run too late. Without any knowledge of Fraser's plans, Hayden resigned as Labor leader just two hours before Fraser travelled to Government House. This meant that the considerably more popular Hawke was able to replace him at almost exactly the same time that the writs were issued for the election. Although Fraser reacted to the move by saying he looked forward to "knock ngtwo Labor Leaders off in one go" at the forthcoming election, Labor immediately surged in the opinion polls.

At the election on 5 March the Coalition was heavily defeated, suffering a 24-seat swing, the worst defeat of a non-Labor government since Federation. Fraser immediately announced his resignation as Liberal leader and formally resigned as prime minister on 11 March 1983; he retired from Parliament two months later. To date, he is the last non-interim prime minister from a rural seat.

Retirement

In retirement Fraser served as Chairman of the UN Panel of Eminent Persons on the Role of Transnational Corporations in South Africa 1985, as Co-Chairman of the Commonwealth Group of Eminent Persons on South Africa in 1985–86 (appointed by Prime Minister Hawke), and as Chairman of the UN Secretary-General's Expert Group on African Commodity Issues in 1989–90. He was a distinguished international fellow at theAmerican Enterprise Institute

The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, known simply as the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), is a center-right Washington, D.C.–based think tank that researches government, politics, economics, and social welfare. A ...

from 1984 to 1986. Fraser helped to establish the foreign aid group CARE

Care may refer to:

Organizations and projects

* CARE (New Zealand), Citizens Association for Racial Equality, a former New Zealand organisation

* CARE (relief agency), "Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere", an international aid and ...

organisation in Australia and became the agency's international president in 1991, and worked with a number of other charitable organisations. In 2006, he was appointed Professorial Fellow at the Asia Pacific Centre for Military Law, and in October 2007 he presented his inaugural professorial lecture, "Finding Security in Terrorism's Shadow: The importance of the rule of law".

Memphis trousers affair

On 14 October 1986, Fraser, then the Chairman of theCommonwealth Eminent Persons Group Several Eminent Persons Groups, abbreviated to EPG, have been founded by the Commonwealth of Nations.

1985 Eminent Persons Group

The first EPG was established at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 1985, held in Nassau. It was tasked ...

, was found in the foyer of the Admiral Benbow Inn, a seedy Memphis hotel, wearing only a pair of underpants and confused as to where his trousers were. The hotel was an establishment popular with prostitutes and drug dealers. Though it was rumoured at the time that the former Prime Minister had been with a prostitute, his wife stated that Fraser had no recollection of the events and that she believes it more likely that he was the victim of a practical joke by his fellow delegates.

Estrangement from the Liberal Party

In 1993, Fraser made a bid for the Liberal Party presidency but withdrew at the last minute following opposition to his bid, which was raised due to his having been critical of then Liberal leader

In 1993, Fraser made a bid for the Liberal Party presidency but withdrew at the last minute following opposition to his bid, which was raised due to his having been critical of then Liberal leader John Hewson

John Robert Hewson AM (born 28 October 1946) is an Australian former politician who served as leader of the Liberal Party from 1990 to 1994. He led the Liberal-National Coalition to defeat at the 1993 Australian federal election.

Hewson wa ...

for losing the election earlier that year.

After 1996, Fraser was critical of the Howard Coalition government over foreign policy issues, particularly John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

's alignment with the foreign policy of the Bush administration, which Fraser saw as damaging Australian relationships in Asia. He opposed Howard's policy on asylum-seekers

An asylum seeker is a person who leaves their country of residence, enters another country and applies for asylum (i.e., international protection) in that other country. An asylum seeker is an immigrant who has been forcibly displaced and m ...

, campaigned in support of an Australian Republic

Republicanism in Australia is a popular movement to change Australia's system of government from a constitutional parliamentary monarchy to a republic, replacing the monarch of Australia (currently Charles III) with a president. Republicanism ...

and attacked what he perceived as a lack of integrity in Australian politics, together with former Labor prime minister Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the h ...

, finding much common ground with his predecessor and his successor Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

, another republican.

The 2001 election continued his estrangement from the Liberal Party. Many Liberals criticised the Fraser years as "a decade of lost opportunity" on deregulation of the Australian economy and other issues. In early 2004, a Young Liberal convention in Hobart called for Fraser's life membership of the Liberal Party to be ended.

In 2006, Fraser criticised Howard Liberal government policies on areas such as refugees, terrorism and civil liberties, and that "if Australia continues to follow United States policies, it runs the risk of being embroiled in the conflict in Iraq for decades, and a fear of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

in the Australian community will take years to eradicate". Fraser claimed that the way the Howard government handled the David Hicks, Cornelia Rau

Cornelia Rau is a German and Australian citizen who was unlawfully detained for a period of ten months in 2004 and 2005 as part of the Australian Government's mandatory detention program.

Her detention became the subject of a government inquiry w ...

and Vivian Solon

Vivian Alvarez Solon (born 30 October 1962) is an Australian who was unlawfully removed to the Philippines by the Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (DIMIA) in July 2001. In May 2005, it became public knowledge th ...

cases was questionable.

On 20 July 2007, Fraser sent an open letter to members of the large activist group GetUp!, encouraging members to support GetUp's campaign for a change in policy on Iraq including a clearly defined exit strategy. Fraser stated: "One of the things we should say to the Americans, quite simply, is that if the United States is not prepared to involve itself in high-level diplomacy concerning Iraq and other Middle East questions, our forces will be withdrawn before Christmas."

After the defeat of the Howard government at the 2007 federal election

This electoral calendar 2007 lists the national/federal direct elections held in 2007 in the de jure and de facto sovereign states and their dependent territories. Referendums are included, although they are not elections. By-elections are not ...

, Fraser claimed Howard approached him in a corridor, following a cabinet meeting in May 1977 regarding Vietnamese refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

s, and said: "We don't want too many of these people. We're doing this just for show, aren't we?" The claims were made by Fraser in an interview to mark the release of the 1977 cabinet papers. Howard, through a spokesman, denied having made the comment.

In October 2007 Fraser gave a speech to Melbourne Law School on terrorism and "the importance of the rule of law," which Liberal MP Sophie Mirabella

Sophie Mirabella (née Panopoulos; born 27 October 1968) is an Australian lawyer and former politician who currently serves as a Commissioner on the Fair Work Commission since 24 May 2021. She was previously a Liberal Party member of the Austra ...

condemned in January 2008, claiming errors and "either intellectual sloppiness or deliberate dishonesty", and claimed that he tacitly supported Islamic fundamentalism, that he should have no influence on foreign policy, and claimed his stance on the war on terror

The war on terror, officially the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), is an ongoing international counterterrorism military campaign initiated by the United States following the September 11 attacks. The main targets of the campaign are militant ...

had left him open to caricature as a "frothing-at-the-mouth leftie".

Shortly after Tony Abbott

Anthony John Abbott (; born 4 November 1957) is a former Australian politician who served as the 28th prime minister of Australia from 2013 to 2015. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Abbott was born in Londo ...

won the 2009 Liberal Party leadership spill, Fraser ended his Liberal Party membership, stating the party was "no longer a liberal party but a conservative party".

Later political activity

In December 2011, Fraser was highly critical of the Australian government's decision (also supported by the Liberal Party Opposition) to permit the export of uranium to India, relaxing the Fraser government's policy of banning sales of uranium to countries that are not signatories of the

In December 2011, Fraser was highly critical of the Australian government's decision (also supported by the Liberal Party Opposition) to permit the export of uranium to India, relaxing the Fraser government's policy of banning sales of uranium to countries that are not signatories of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation ...

.

In 2012, Fraser criticised the basing of US military forces in Australia.

In late 2012, Fraser wrote a foreword for the journal ''Jurisprudence'' where he openly criticised the current state of human rights in Australia and the Western World. "It is a sobering thought that in recent times, freedoms hard won through centuries of struggle, in the United Kingdom and elsewhere have been whittled away. In Australia alone we have laws that allow the secret detention of the innocent. We have had a vast expansion of the power of intelligence agencies. In many cases the onus of proof has been reversed and the justice that once prevailed has been gravely diminished."

In July 2013, Fraser endorsed Australian Greens

The Australian Greens, commonly known as The Greens, are a confederation of Green state and territory political parties in Australia. As of the 2022 federal election, the Greens are the third largest political party in Australia by vote and t ...

Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

Sarah Hanson-Young

Sarah Coral Hanson-Young (née Hanson; born 23 December 1981) is an Australian politician who has been a Senator for South Australia since July 2008, representing the Australian Greens. She is a graduate of the WEF young global leaders program. ...

for re-election in a television advertisement, stating she had been a "reasonable and fair-minded voice".

Fraser's books include ''Malcolm Fraser: The Political Memoirs'' (with Margaret Simons

Margaret Simons (born 1960) is an Australian academic, freelance journalist and author. She has written numerous articles and essays as well as many books, including a biography of Senate leader of the Australian Labor Party Penny Wong. Her essa ...

– The Miegunyah Press, 2010) and ''Dangerous Allies'' (Melbourne University Press, 2014), which warns of "strategic dependence" on the United States. In the book and in talks promoting it, he criticised the concept of American exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the belief that the United States is inherently different from other nations.US foreign policy

The officially stated goals of the foreign policy of the United States of America, including all the bureaus and offices in the United States Department of State, as mentioned in the ''Foreign Policy Agenda'' of the Department of State, are ...

.

Personal life

Marriage and children

On 9 December 1956, Fraser married Tamara "Tamie" Beggs, who was almost six years his junior. They had met at a New Year's Eve party, and bonded over similar personal backgrounds and political views. The couple had four children together: Mark (b. 1958), Angela (b. 1959), Hugh (b. 1963), and Phoebe (b. 1966). Tamie frequently assisted her husband in campaigning, and her gregariousness was seen as complementing his more shy and reserved nature. She advised him on most of the important decisions in his career, and in retirement he observed that "if she had been prime minister in 1983, we would have won".

On 9 December 1956, Fraser married Tamara "Tamie" Beggs, who was almost six years his junior. They had met at a New Year's Eve party, and bonded over similar personal backgrounds and political views. The couple had four children together: Mark (b. 1958), Angela (b. 1959), Hugh (b. 1963), and Phoebe (b. 1966). Tamie frequently assisted her husband in campaigning, and her gregariousness was seen as complementing his more shy and reserved nature. She advised him on most of the important decisions in his career, and in retirement he observed that "if she had been prime minister in 1983, we would have won".

Views on religion

Fraser attended Anglican schools, although his parents were Presbyterian. In university he was inclined towards atheism, once writing that "the idea that God exists is a nonsense". However, his beliefs became less definite over time and tended towards agnosticism. During his political career, he occasionally self-described as Christian, such as in a 1975 interview with '' The Catholic Weekly''.Margaret Simons

Margaret Simons (born 1960) is an Australian academic, freelance journalist and author. She has written numerous articles and essays as well as many books, including a biography of Senate leader of the Australian Labor Party Penny Wong. Her essa ...

, the co-author of Fraser's memoirs, thought that he was "not religious, and yet thinks religion is a necessary thing". In a 2010 interview with her, he said: "I would probably like to be less logical and, you know, really able to believe there is a God, whether it is Allah, or the Christian God, or some other – but I think I studied too much philosophy ... you can never know".

Death and legacy

Fraser died on 20 March 2015 at the age of 84, after a brief illness. Anobituary

An obituary ( obit for short) is an article about a recently deceased person. Newspapers often publish obituaries as news articles. Although obituaries tend to focus on positive aspects of the subject's life, this is not always the case. Ac ...

noted that there had been "greater appreciation of the constructive and positive nature of his post-prime ministerial contribution" as his retirement years progressed. Fraser's death came five months after that of his predecessor and political rival Gough Whitlam.

Upon his death, Fraser's 1983 nemesis and often bitter opponent Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

fondly described him as a "very significant figure in the history of Australian politics" who, in his post-Prime Ministerial years, "became an outstanding figure in the advancement of human rights issues in all respects", praised him for being "extraordinarily generous and welcoming to refugees from Indochina" and concluded that Fraser had "moved so far to the left he was almost out of sight". Andrew Peacock

Andrew Sharp Peacock (13 February 193916 April 2021) was an Australian politician and diplomat. He served as a cabinet minister and went on to become leader of the Liberal Party on two occasions (1983–1985 and 1989–1990), leading the pa ...

, who had challenged Fraser for the Liberal leadership and later succeeded him, said that he had "a deep respect and pleasurable memories of the first five years of the Fraser Government... I disagreed with him later on but during that period in the 1970s he was a very effective Prime Minister", and lamented that "despite all my arguments with him later on I am filled with admiration for his efforts on China".Andrew PeacockSentiments on Australia’s influential political figures

The Australian, 12 March 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2019. Fraser was given a state funeral at Scots' Church in Melbourne on 27 March 2015. His ashes are interred within the Prime Ministers Garden of

Melbourne General Cemetery

The Melbourne General Cemetery is a large (43 hectare) necropolis located north of the city of Melbourne in the suburb of Carlton North.