Mahdist War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "

Among the forces historians see as the causes of the uprising are

Among the forces historians see as the causes of the uprising are

It was therefore decided by the Egyptian government, under some coercion from their British comptrollers, that the Egyptian presence in the Sudan should be withdrawn and the country left to some form of self-government, likely headed by the Mahdi. The withdrawal of the Egyptian garrisons stationed throughout the country, such as those at

It was therefore decided by the Egyptian government, under some coercion from their British comptrollers, that the Egyptian presence in the Sudan should be withdrawn and the country left to some form of self-government, likely headed by the Mahdi. The withdrawal of the Egyptian garrisons stationed throughout the country, such as those at  Gordon arrived in Khartoum on 18 February, and immediately became apprised of the vast difficulty of the task. Egypt's garrisons were scattered widely across the country; three—

Gordon arrived in Khartoum on 18 February, and immediately became apprised of the vast difficulty of the task. Egypt's garrisons were scattered widely across the country; three—

Gordon's position in Khartoum was very strong, as the city was bordered to the north and east by the

Gordon's position in Khartoum was very strong, as the city was bordered to the north and east by the

The British also sent an expeditionary force under Lieutenant-General Sir

The British also sent an expeditionary force under Lieutenant-General Sir

In the intervening years, Egypt had not renounced her claims over Sudan, and the British authorities considered these claims legitimate. Under strict control by British administrators, Egypt's economy had been rebuilt, and the Egyptian army reformed, this time trained and led by British officers and non-commissioned officers. The situation evolved in a way that allowed Egypt, both politically and militarily, to reconquer Sudan.

In the intervening years, Egypt had not renounced her claims over Sudan, and the British authorities considered these claims legitimate. Under strict control by British administrators, Egypt's economy had been rebuilt, and the Egyptian army reformed, this time trained and led by British officers and non-commissioned officers. The situation evolved in a way that allowed Egypt, both politically and militarily, to reconquer Sudan.

Since 1890, Italian Empire, Italian troops had defeated Mahdist troops in the Battle of Serobeti and the First Battle of Agordat. In December 1893, Italian colonial troops and Mahdists fought again in the Second Battle of Agordat; Ahmed Ali campaigned against the Italian forces in eastern Sudan and led about 10–12,000 men east from Kassala, encountering 2,400 Kingdom of Italy, Italians and their Eritrean Ascaris commanded by Colonel Arimondi. The Italians won again, and the outcome of the battle constituted "the first decisive victory yet won by Europeans against the Sudanese revolutionaries". A year later, Italian Eritrea, Italian colonial forces seized Kassala after the successful Battle of Kassala.

In 1891 a Catholic priest, Father Joseph Ohrwalder, escaped from captivity in Sudan. In 1895 the erstwhile Governor of Darfur, Rudolf Carl von Slatin, managed to escape from the Khalifa's prison. Besides providing vital intelligence on the Mahdist dispositions, both men wrote detailed accounts of their experiences in Sudan. Written in collaboration with Reginald Wingate, a proponent of the reconquest of Sudan, both works emphasized the savagery and barbarism of the Mahdists, and through the wide publicity they received in Britain, served to influence public opinion in favour of military intervention.

In 1896, when Italy suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the Ethiopians at Battle of Adwa, Adwa, the Italian position in East Africa was seriously weakened. The Mahdists threatened to retake Kassala, which they had lost to the Italians in 1894. The British government judged it politic to assist the Italians by making a military demonstration in northern Sudan. This coincided with the increased threat of French encroachment on the Upper Nile, Sudan, Upper Nile regions. Lord Cromer, judging that the Unionist government, 1895–1905, Conservative-Unionist government in power would favour taking the offensive, managed to extend the demonstration into a full-fledged invasion. In 1897, the Italians gave back to the British the control of Kassala, returning in Italian Eritrea, in order to get international recognition of their colony.

Since 1890, Italian Empire, Italian troops had defeated Mahdist troops in the Battle of Serobeti and the First Battle of Agordat. In December 1893, Italian colonial troops and Mahdists fought again in the Second Battle of Agordat; Ahmed Ali campaigned against the Italian forces in eastern Sudan and led about 10–12,000 men east from Kassala, encountering 2,400 Kingdom of Italy, Italians and their Eritrean Ascaris commanded by Colonel Arimondi. The Italians won again, and the outcome of the battle constituted "the first decisive victory yet won by Europeans against the Sudanese revolutionaries". A year later, Italian Eritrea, Italian colonial forces seized Kassala after the successful Battle of Kassala.

In 1891 a Catholic priest, Father Joseph Ohrwalder, escaped from captivity in Sudan. In 1895 the erstwhile Governor of Darfur, Rudolf Carl von Slatin, managed to escape from the Khalifa's prison. Besides providing vital intelligence on the Mahdist dispositions, both men wrote detailed accounts of their experiences in Sudan. Written in collaboration with Reginald Wingate, a proponent of the reconquest of Sudan, both works emphasized the savagery and barbarism of the Mahdists, and through the wide publicity they received in Britain, served to influence public opinion in favour of military intervention.

In 1896, when Italy suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the Ethiopians at Battle of Adwa, Adwa, the Italian position in East Africa was seriously weakened. The Mahdists threatened to retake Kassala, which they had lost to the Italians in 1894. The British government judged it politic to assist the Italians by making a military demonstration in northern Sudan. This coincided with the increased threat of French encroachment on the Upper Nile, Sudan, Upper Nile regions. Lord Cromer, judging that the Unionist government, 1895–1905, Conservative-Unionist government in power would favour taking the offensive, managed to extend the demonstration into a full-fledged invasion. In 1897, the Italians gave back to the British the control of Kassala, returning in Italian Eritrea, in order to get international recognition of their colony.

Herbert Kitchener, the new ''Sirdar (Egypt), Sirdar'' (commander) of the Anglo-Egyptian Army, received his marching orders on 12 March, and his forces entered Sudan on the 18th. Numbering at first 11,000 men, Kitchener's force was armed with the most modern military equipment of the time, including Maxim gun, Maxim machine-guns and modern artillery, and was supported by a flotilla of River gunboat, gunboats on the Nile. Their advance was slow and methodical, while fortified camps were built along the way, and two separate Narrow gauge railways were hastily constructed from a station at Wadi Halfa: the first rebuilt Isma'il Pasha's abortive and ruined former line south along the east bank of the Nile to supply the 1896 Dongola Expedition and a second, carried out in 1897, was extended along a new line directly across the desert to Abu Hamad—which they captured in the Battle of Abu Hamed on 7 August 1897—to supply the main force moving on Khartoum.Gleichen, Edward ed.

Herbert Kitchener, the new ''Sirdar (Egypt), Sirdar'' (commander) of the Anglo-Egyptian Army, received his marching orders on 12 March, and his forces entered Sudan on the 18th. Numbering at first 11,000 men, Kitchener's force was armed with the most modern military equipment of the time, including Maxim gun, Maxim machine-guns and modern artillery, and was supported by a flotilla of River gunboat, gunboats on the Nile. Their advance was slow and methodical, while fortified camps were built along the way, and two separate Narrow gauge railways were hastily constructed from a station at Wadi Halfa: the first rebuilt Isma'il Pasha's abortive and ruined former line south along the east bank of the Nile to supply the 1896 Dongola Expedition and a second, carried out in 1897, was extended along a new line directly across the desert to Abu Hamad—which they captured in the Battle of Abu Hamed on 7 August 1897—to supply the main force moving on Khartoum.Gleichen, Edward ed.

The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: A Compendium Prepared by Officers of the Sudan Government

', Vol. 1, p. 99. Harrison & Sons (London), 1905. Accessed 13 February 2014.Sudan Railway Corporation.

". 2008. Accessed 13 February 2014. It was not until 7 June 1896 that the first serious engagement of the campaign occurred, when Kitchener led a 9,000 strong force that wiped out the Mahdist garrison at Battle of Ferkeh, Ferkeh. In 1898, in the context of the scramble for Africa, the British decided to reassert Egypt's claim on Sudan. An expedition commanded by Kitchener was organised in Egypt. It was composed of 8,200 British soldiers and 17,600 Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers commanded by British officers. The Mahdist forces (sometimes called the Dervishes) were more numerous, numbering more than 60,000 warriors, but lacked modern weapons.

After defeating a Mahdist force in the Battle of Atbara in April 1898, the Anglo-Egyptians reached Omdurman, the Mahdist capital, in September. The bulk of the Mahdist army Battle of Omdurman, attacked, but was cut down by British machine-guns and rifle fire.

The remnant, with the Khalifa Abdullah, fled to southern Sudan. During the pursuit, Kitchener's forces met a French force under Major Jean-Baptiste Marchand at

In 1898, in the context of the scramble for Africa, the British decided to reassert Egypt's claim on Sudan. An expedition commanded by Kitchener was organised in Egypt. It was composed of 8,200 British soldiers and 17,600 Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers commanded by British officers. The Mahdist forces (sometimes called the Dervishes) were more numerous, numbering more than 60,000 warriors, but lacked modern weapons.

After defeating a Mahdist force in the Battle of Atbara in April 1898, the Anglo-Egyptians reached Omdurman, the Mahdist capital, in September. The bulk of the Mahdist army Battle of Omdurman, attacked, but was cut down by British machine-guns and rifle fire.

The remnant, with the Khalifa Abdullah, fled to southern Sudan. During the pursuit, Kitchener's forces met a French force under Major Jean-Baptiste Marchand at

Sufi flags typically feature the Muslim shahada – "There is no God but Allah; Muḥammad is Allah’s Messenger" – and the name of the sect’s founder, an individual usually regarded as a saint. The Mahdī adapted this form of flag for military purposes. A quotation from the Koran was added – "Yā allah yā ḥayy yā qayūm yā ḍhi’l-jalāl wa’l-ikrām" (O Allah! O Ever-living, O Everlasting, O Lord of Majesty and Generosity) – and the highly charged claim – "Muḥammad al-Mahdī khalifat rasūl Allah" (Muḥammad al-Mahdī is the successor of Allah’s messenger).

After the fall of Khartoum, a "Tailor of Flags" was set up in Omdurman. The production of flags became standardised and regulations concerning the colour and inscriptions of the flags were established. As the Mahdist forces became more organized, the word "flag" (rayya) came to mean a division of troops or a body of troops under a commander. The flags were colour coded to direct soldiers of the three main divisions of the Mahdist army – the Black, Green and Red Banners (rāyāt).

Sufi flags typically feature the Muslim shahada – "There is no God but Allah; Muḥammad is Allah’s Messenger" – and the name of the sect’s founder, an individual usually regarded as a saint. The Mahdī adapted this form of flag for military purposes. A quotation from the Koran was added – "Yā allah yā ḥayy yā qayūm yā ḍhi’l-jalāl wa’l-ikrām" (O Allah! O Ever-living, O Everlasting, O Lord of Majesty and Generosity) – and the highly charged claim – "Muḥammad al-Mahdī khalifat rasūl Allah" (Muḥammad al-Mahdī is the successor of Allah’s messenger).

After the fall of Khartoum, a "Tailor of Flags" was set up in Omdurman. The production of flags became standardised and regulations concerning the colour and inscriptions of the flags were established. As the Mahdist forces became more organized, the word "flag" (rayya) came to mean a division of troops or a body of troops under a commander. The flags were colour coded to direct soldiers of the three main divisions of the Mahdist army – the Black, Green and Red Banners (rāyāt).

The jibba: clothing for Sufi and soldier

''Making African Connections''. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

Churchill, The River War

Too late for Gordon and Khartoum, 1887

Ten years captivity in the Mahdist camp

Suakin 1885

The Downfall of the Dervishes, 1898

Sudan Campaign 1896–1899

The British Expedition to Rescue Emin Pasha

{{Authority control Mahdist War, African resistance to colonialism Wars involving the United Kingdom Wars involving Sudan Wars involving the states and peoples of Africa 19th-century military history of the United Kingdom Wars involving Egypt Rebellions in Africa Rebellions against the British Empire Wars involving British India 19th century in Egypt 19th century in Africa Proxy wars

Mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a Messianism, messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a de ...

" of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

(the "Guided One"), and the forces of the Khedivate of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which br ...

, initially, and later the forces of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

. Eighteen years of war resulted in the nominally joint-rule state of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ar, السودان الإنجليزي المصري ') was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt in the Sudans region of northern Africa between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day ...

(1899–1956), a ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

and the Kingdom of Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt ( ar, المملكة المصرية, Al-Mamlaka Al-Miṣreyya, The Egyptian Kingdom) was the legal form of the Egyptian state during the latter period of the Muhammad Ali dynasty's reign, from the United Kingdom's recog ...

in which Britain had ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' control over the Sudan. The Sudanese launched several unsuccessful invasions of their neighbours, expanding the scale of the conflict to include not only Britain and Egypt but also the Italian Empire

The Italian colonial empire ( it, Impero coloniale italiano), known as the Italian Empire (''Impero Italiano'') between 1936 and 1943, began in Africa in the 19th century and comprised the colonies, protectorates, concessions and dependencie ...

, the Congo Free State and the Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historical ...

.

The British participation in the war is called the Sudan campaign. Other names for this war include the Mahdist Revolt, the Anglo–Sudan War and the Sudanese Mahdist Revolt.

Background

Following the invasion byMuhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

in 1819, Sudan was governed by an Egyptian administration. Because of the heavy taxes it imposed and because of the bloody start of the Turkish-Egyptian rule in Sudan, this colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

system was resented by the Sudanese people.

Throughout the period of Turco-Egyptian rule, many segments of the Sudanese population suffered extreme hardship because of the system of taxation imposed by the central government. Under this system, a flat tax was imposed on farmers and small traders and collected by government-appointed tax collectors from the Sha'iqiyya tribe of northern Sudan. In bad years, and especially during times of drought and famine, farmers were unable to pay the high taxes. Fearing the brutal and unjust methods of the Sha'iqiyya, many farmers fled their villages in the fertile Nile Valley to the remote areas of Kordofan

Kordofan ( ar, كردفان ') is a former province of central Sudan. In 1994 it was divided into three new federal states: North Kordofan, South Kordofan and West Kordofan. In August 2005, West Kordofan State was abolished and its territory ...

and Darfur. These migrants, known as "jallaba" after their loose-fitting style of dress, began to function as small traders and middlemen for the foreign trading companies that had established themselves in the cities and towns of central Sudan. The jallaba were also known to be slave trading tribes.

By the middle 19th century the Ottoman Imperial subject administration in Egypt was in the hands of Khedive Ismail

Isma'il Pasha ( ar, إسماعيل باشا ; 12 January 1830 – 2 March 1895), was the Khedive of Egypt and conqueror of Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of Great Britain. Sharing the ambitious outlook of his gran ...

. Khedive Ismail's spending had put Egypt into huge debt, and when his financing of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

started to crumble, the United Kingdom stepped in and repaid his loans in return for controlling shares in the canal. As the most direct route to India, the jewel in the British Crown, the Suez Canal was of paramount strategic importance, and British commercial and imperial interests dictated the need to seize or otherwise control it. Thus an ever-increasing British role in Egyptian affairs seemed necessary. With Khedive Ismail's spending and corruption causing instability, in 1873 the British government supported a program whereby an Anglo-French debt commission assumed responsibility for managing Egypt's fiscal affairs. This commission eventually forced Khedive Ismail

Isma'il Pasha ( ar, إسماعيل باشا ; 12 January 1830 – 2 March 1895), was the Khedive of Egypt and conqueror of Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of Great Britain. Sharing the ambitious outlook of his gran ...

to abdicate in favor of his son Tawfiq in 1877, leading to a period of political turmoil.

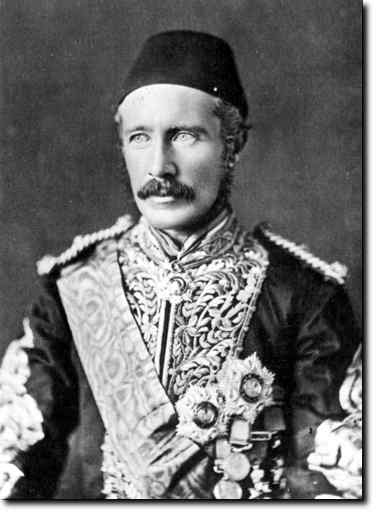

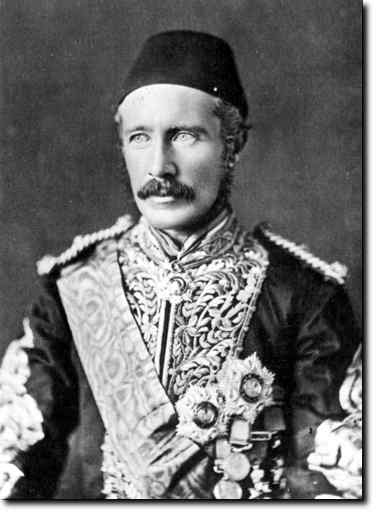

Also in 1873, Ismail had appointed General Charles "Chinese" Gordon Governor of the Equatorial Provinces of Sudan. For the next three years, General Gordon fought against a native chieftain of Darfur, Al-Zubayr Rahma Mansur

Al-Zubayr Rahma Mansur Pasha ( ar, الزبير رحمة منصور; 1830 – January 1913), also known as Sebehr Rahma or Rahama Zobeir, Hake, Alfred Egmont.The Story of Chinese Gordon, 1884. was a slave trader in the late 19th century. He lat ...

.

Upon Ismail's abdication in 1877, Gordon found himself with dramatically decreased support. Exhausted by years of work, he resigned his post in 1880 and left early the next year. His policies were soon abandoned by the new governors, but the anger and discontent of the dominant Arab minority was left unaddressed.

Although the Egyptians were fearful of the deteriorating conditions, the British refused to get involved, as Foreign Secretary Earl Granville

Earl Granville is a title that has been created twice, once in the Peerage of Great Britain and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It is now held by members of the Leveson-Gower family.

First creation

The first creation came in the Pee ...

declared, "Her Majesty’s Government are in no way responsible for operations in the Sudan".

Historical development of the conflict

Mahdi uprising

Among the forces historians see as the causes of the uprising are

Among the forces historians see as the causes of the uprising are ethnic

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

Sudanese anger at the foreign Turkish Ottoman rulers, Muslim revivalist anger at the Turks' lax religious standards and willingness to appoint non-Muslims such as the Christian Charles Gordon to high positions, and Sudanese Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

resistance to "dry, scholastic Islam of Egyptian officialdom."Mortimer, Edward, ''Faith and Power'', Vintage, 1982, p. 77. Another widely reported potential source of frustration was the Turco-Egyptian abolition of the slave trade, one of the main sources of income in Sudan at the time.

In the 1870s, a Muslim cleric named Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad ( ar, محمد أحمد ابن عبد الله; 12 August 1844 – 22 June 1885) was a Nubian Sufi religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, as a youth, studied Sunni Islam. In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi, ...

preached renewal of the faith and liberation of the land, and began attracting followers. Soon in open revolt against the Egyptians, Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself the Mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a Messianism, messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a de ...

, the promised redeemer of the Islamic world. In August 1881 the then-governor of the Sudan, Raouf Pasha, sent two companies of infantry each with one machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

to arrest him. The captains of the two companies were each promised promotion if their soldiers were the ones to return the Mahdi to the governor. Both companies disembarked from the steamer that had brought them up the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

to Aba Island

Aba Island is an island on the White Nile to the south of Khartoum, Sudan. It is the original home of the Mahdi in Sudan and the spiritual base of the Umma Party.

History

Aba Island was the birthplace of the Mahdiyya, first declared on J ...

and approached the Mahdi's village from separate directions. Arriving simultaneously, each force began to fire blindly on the other, allowing the Mahdi's scant followers to attack and destroy each force in turn at the Battle of Aba

The Battle of Aba, which took place on August 12, 1881, was the opening battle of the Mahdist War. The incident saw Mahdist rebels, led by Muhammad Ahmad, who had proclaimed himself the Mahdi, rout Egyptian troops who had landed on Aba Island.

...

.

The Mahdi then began a strategic retreat to Kordofan

Kordofan ( ar, كردفان ') is a former province of central Sudan. In 1994 it was divided into three new federal states: North Kordofan, South Kordofan and West Kordofan. In August 2005, West Kordofan State was abolished and its territory ...

, where he was at a distance from the seat of government in Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

. This movement, couched as a triumphal progress, incited many of the Arab tribes to rise in support of the Jihad the Mahdi had declared against the Turkish oppressors.

The Mahdi and the forces of his Ansar arrived in the Nuba Mountains of south Kordofan around early November 1881. Another Egyptian expedition dispatched from Fashoda

Kodok or Kothok ( ar, كودوك), formerly known as Fashoda, is a town in the north-eastern South Sudanese state of Upper Nile State. Kodok is the capital of Shilluk country, formally known as the Shilluk Kingdom. Shilluk had been an independ ...

arrived around one month later; this force was ambushed and slaughtered on the night of 9 December 1881. Consisting, like the earlier Aba Island force, of two 200 man strong Egyptian raised infantry companies, this time augmented with an additional 1,000 native irregulars, the force commander – Colonel Rashid Bay Ahman – and all his principal leadership team, died. It is unknown if any of Colonel Ahman's troops survived.

As these military incursions were happening, the Mahdi legitimized his movement by drawing deliberate parallels to the life of the Prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monoth ...

. He called his followers Ansar, after the people who greeted the Prophet in Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, and he called his flight from the British, the hijrah

The Hijrah or Hijra () was the journey of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina. The year in which the Hijrah took place is also identified as the epoch of the Lunar Hijri and Solar Hijri calendars; its date e ...

, after the Prophet's flight from the Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Qur ...

. The Mahdi also appointed commanders to represent three of the four Righteous Caliphs; for example, he announced that Abdullahi ibn Muhammad, his eventual successor, represented Abu Bakr Al Sidiq, the Prophet's successor.

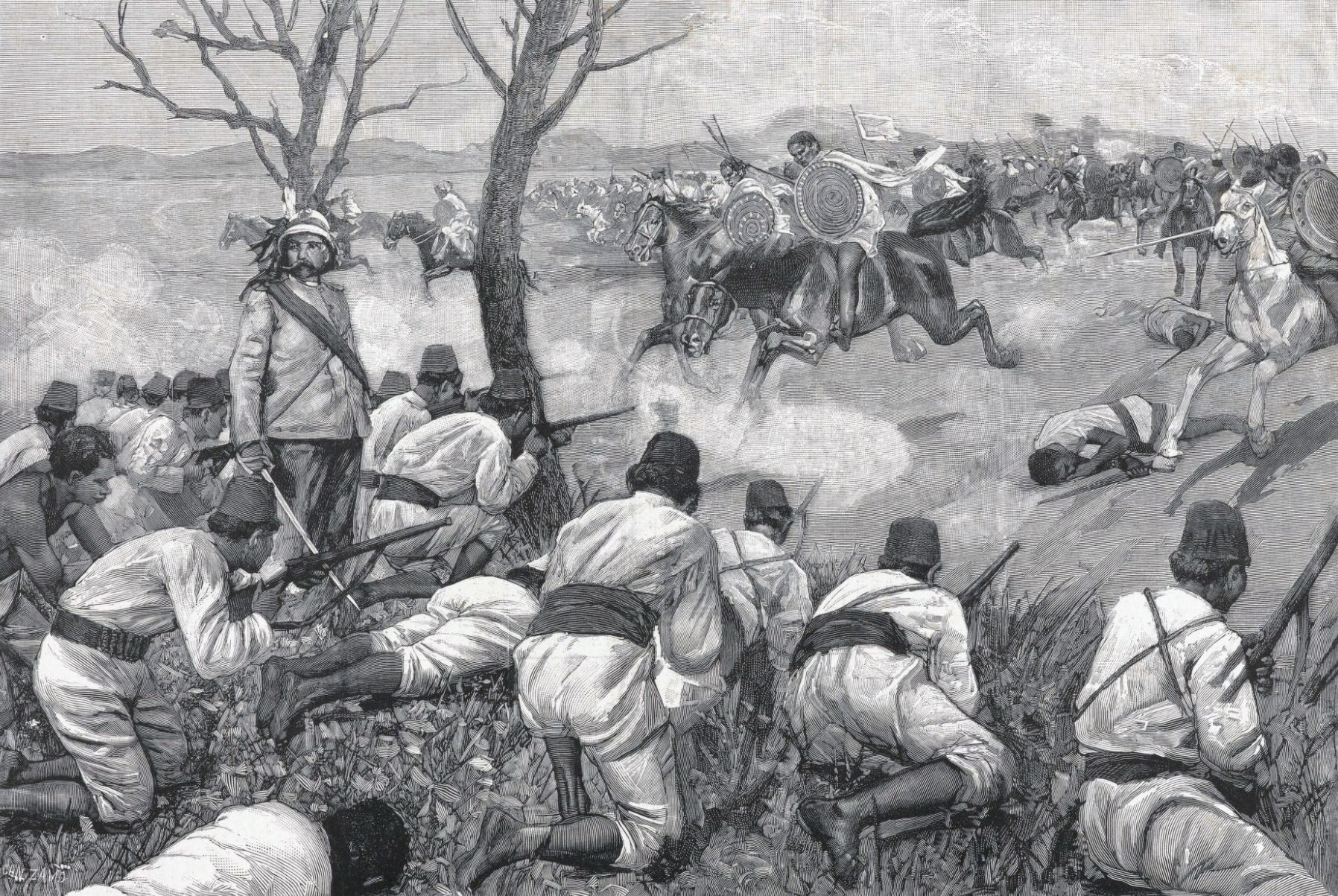

The Egyptian administration in the Sudan, now thoroughly concerned by the scale of the uprising, assembled a force of 4,000 troops under Yusef Pasha. In mid 1882, this force approached the Mahdist gathering, whose members were poorly clothed, half starving, and armed only with sticks and stones. However, supreme overconfidence led the Egyptian army into camping within sight of the Mahdist 'army' without posting sentries. The Mahdi led a dawn assault on 7 June 1882, which slaughtered the army to a man. The rebels gained vast stores of arms and ammunition, military clothing and other supplies.

Hicks expedition

With the Egyptian government now passing largely under British control, the European powers became increasingly aware of the troubles in the Sudan. The British advisers to the Egyptian government gave tacit consent for another expedition. Throughout the summer of 1883, Egyptian troops were concentrated at Khartoum, eventually reaching the strength of around 7,300infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

, 1,000 cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

, and an artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

force of 300 personnel hauling between them 4 Krupp 80mm field guns, 10 brass mountain guns and 6 Nordenfeldt machine guns. This force was placed under the command of a retired British Indian Staff Corps

The Indian Staff Corps was a branch of the Indian Army during the British Raj.

Separate Staff Corps were formed in 1861 for the Bengal, Madras and Bombay Armies, which were later combined into the Indian Army. They were meant to provide officers f ...

officer William Hicks and twelve European officers. The force was, in the words of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, "perhaps the worst army that has ever marched to war"—unpaid, untrained, and undisciplined, its soldiers having more in common with their enemies than with their officers.

El Obeid

El-Obeid ( ar, الأبيض, ''al-ʾAbyaḍ'', lit."the White"), also romanized as Al-Ubayyid, is the capital of the state of North Kurdufan, in Sudan.

History and overview

El-Obeid was founded by the pashas of Ottoman Egypt in 1821. It ...

, the city whose siege Hicks had intended to relieve, had already fallen by the time the expedition left Khartoum, but Hicks continued anyway, although not confident of his chances of success. Upon his approach, the Mahdi assembled an army of about 40,000 men and drilled them rigorously in the art of war

''The Art of War'' () is an ancient Chinese military treatise dating from the Late Spring and Autumn Period (roughly 5th century BC). The work, which is attributed to the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu ("Master Sun"), is comp ...

, equipping them with the arms and ammunition captured in previous battles. On 3 and 4 November 1883, when Hicks' forces actually offered battle, the Mahdist army was a credible military force, which utterly defeated Hicks' army—only about 500 Egyptians survived—at the Battle of El Obeid

The Battle of Shaykan was fought between Anglo-Egyptian forces under the command of Hicks Pasha and forces of Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi, in the woods of Shaykan near Kashgil near the town of El-Obeid on 3–5 November 1883.

...

.

Egyptian evacuation

At this time, the British Empire was increasingly entrenching itself in the workings of the Egyptian government. Egypt was groaning under a barely maintainable debt repayment structure for her enormous European debt. For the Egyptian government to avoid further interference from its Europeancreditor

A creditor or lender is a party (e.g., person, organization, company, or government) that has a claim on the services of a second party. It is a person or institution to whom money is owed. The first party, in general, has provided some property ...

s, it had to ensure that the debt interest

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a borrower or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum (that is, the amount borrowed), at a particular rate. It is distin ...

was paid on time, every time. To this end, the Egyptian treasury, initially crippled by corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

and bureaucracy

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

, was placed by the British almost entirely under the control of a 'Financial Advisor', who exercised the power of veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

over all matters of financial policy. The holders of this office—first Sir Auckland Colvin

Sir Auckland Colvin (1838–1908) was a colonial administrator in India and Egypt, born into the Anglo-Indian Colvin family. He was comptroller general in Egypt (1880–2), and financial adviser to the Khedive (1883–87). From 1883–92 he wa ...

, and later Sir Edgar Vincent

Edgar Vincent (13 March 1918, Hamburg — 26 June 2008, New York City) was an American publicist and actor of Germany, German birth. He began his career appearing in small roles in Hollywood films during the 1940s but his German accent prevented ...

—were instructed to exercise the greatest possible parsimony in Egypt's financial affairs. Maintaining the garrisons in the Sudan was costing the Egyptian government over 100,000 Egyptian pounds a year, an unmaintainable expense.

It was therefore decided by the Egyptian government, under some coercion from their British comptrollers, that the Egyptian presence in the Sudan should be withdrawn and the country left to some form of self-government, likely headed by the Mahdi. The withdrawal of the Egyptian garrisons stationed throughout the country, such as those at

It was therefore decided by the Egyptian government, under some coercion from their British comptrollers, that the Egyptian presence in the Sudan should be withdrawn and the country left to some form of self-government, likely headed by the Mahdi. The withdrawal of the Egyptian garrisons stationed throughout the country, such as those at Sennar

Sennar ( ar, سنار ') is a city on the Blue Nile in Sudan and possibly the capital of the state of Sennar. It remains publicly unclear whether Sennar or Singa is the capital of Sennar State. For several centuries it was the capital of the F ...

, Tokar and Sinkat, was therefore threatened unless it was conducted in an orderly fashion. The Egyptian government asked for a British officer to be sent to the Sudan to co-ordinate the withdrawal of the garrisons. It was hoped that Mahdist forces would judge an attack on a British subject to be too great a risk, and hence allow the withdrawal to proceed without incident. It was proposed to send Charles 'Chinese' Gordon. Gordon was a gifted officer, who had gained renown commanding Imperial Chinese

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the ''Book of Documents'' (early chapter ...

forces during the Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion, also known as the Taiping Civil War or the Taiping Revolution, was a massive rebellion and civil war that was waged in China between the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the Han, Hakka-led Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. It laste ...

. However, he was also renowned for his aggression and rigid personal honour

Honour (British English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is the idea of a bond between an individual and a society as a quality of a person that is both of social teaching and of personal ethos, that manifests itself as a ...

, which, in the eyes of several prominent British officials in Egypt, made him unsuitable for the task. Sir Evelyn Baring (later the Earl of Cromer

Earl of Cromer is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, held by members of the Baring family, of German descent. It was created for Evelyn Baring, 1st Viscount Cromer, long time British Consul-General in Egypt. He had already been cr ...

), the British Consul-general

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

in Egypt, was particularly opposed to Gordon's appointment, only reluctantly being won over by the British press

Press may refer to:

Media

* Print media or news media, commonly called "the press"

* Printing press, commonly called "the press"

* Press (newspaper), a list of newspapers

* Press TV, an Iranian television network

People

* Press (surname), a fam ...

and public

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichkei ...

. Gordon was eventually given the mission, but he was to be accompanied by the much more level-headed and reliable Colonel John Stewart. It was intended that Stewart, while nominally Gordon's subordinate, would act as a brake on the latter and ensure that the Sudan was evacuated quickly and peacefully.

Gordon left England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

on 18 January 1884 and arrived in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

on the evening of 24 January. Gordon was largely responsible for drafting his own orders, along with proclamations from the Khedive announcing Egypt's intentions to leave the Sudan. Gordon's orders, by his own request, were unequivocal and left little room for misinterpretation.

Gordon arrived in Khartoum on 18 February, and immediately became apprised of the vast difficulty of the task. Egypt's garrisons were scattered widely across the country; three—

Gordon arrived in Khartoum on 18 February, and immediately became apprised of the vast difficulty of the task. Egypt's garrisons were scattered widely across the country; three—Sennar

Sennar ( ar, سنار ') is a city on the Blue Nile in Sudan and possibly the capital of the state of Sennar. It remains publicly unclear whether Sennar or Singa is the capital of Sennar State. For several centuries it was the capital of the F ...

, Tokar and Sinkat—were under siege, and the majority of the territory between them was under the control of the Mahdi. There was no guarantee that, if the garrisons were to sortie, even with the clear intention of withdrawing, they would not be cut to pieces by the Mahdist forces. Khartoum's Egyptian and European population was greater than all the other garrisons combined, including 7,000 Egyptian troops and 27,000 civilians and the staffs of several embassies. Although the pragmatic approach would have been to secure the safety of the Khartoum garrison and abandon the outlying fortifications and their troops to the Mahdi, Gordon became increasingly reluctant to leave the Sudan until "every one who wants to go down he Nileis given the chance to do so," feeling it would be a slight on his honour to abandon any Egyptian soldiers to the Mahdi. He also became increasingly fearful of the Mahdi's potential to cause trouble in Egypt if allowed control of the Sudan, leading to a conviction that the Mahdi must be "crushed," by British troops if necessary, to assure the stability of the region. It is debated whether or not Gordon deliberately remained in Khartoum longer than strategically sensible, seemingly intent on becoming besieged within the town. Gordon's brother, H. W. Gordon, was of the opinion that the British officers could easily have escaped from Khartoum up until 14 December 1884.

Whether or not it was the Mahdi's intention, in March 1884, the Sudanese tribes to the north of Khartoum, who had previously been sympathetic or at least neutral towards the Egyptian authorities, rose in support of the Mahdi. The telegraph line

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

s between Khartoum and Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

were cut on 15 March, severing communication between Khartoum and the outside world.

Siege of Khartoum

Gordon's position in Khartoum was very strong, as the city was bordered to the north and east by the

Gordon's position in Khartoum was very strong, as the city was bordered to the north and east by the Blue Nile

The Blue Nile (; ) is a river originating at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. It travels for approximately through Ethiopia and Sudan. Along with the White Nile, it is one of the two major tributaries of the Nile and supplies about 85.6% of the water to ...

, to the west by the White Nile, and to the south by ancient fortifications looking on to a vast expanse of desert. Gordon had food for an estimated six months, several million rounds of ammunition in store, with the capacity to produce a further 50,000 rounds per week, and 7,000 Egyptian soldiers. But outside the walls, the Mahdi had mustered about 50,000 Dervish

Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from fa, درویش, ''Darvīsh'') in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity

A fraternity (from Latin language, Latin ''wiktionary:frater, frater'': "brother (Christian), brother"; whence, ...

soldiers, and as time went on, the chances of a successful breakout became slim. Gordon had enthusiastically supported the idea of recalling the notorious former slaver Pasha Zobeir from exile in Egypt to organize and lead a popular uprising against the Mahdi. When this idea was vetoed by the British government, Gordon proposed a number of alternative means to salvage his situation successively to his British superiors. All were similarly vetoed. Among them were:

* Making a breakout ''southwards'' along the Blue Nile towards Abyssinia (now Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

), which would have enabled him to collect the garrisons stationed along that route. The window for navigation of the upper reaches of that river was very narrow.

* Requesting Mohammedan regiments from India.Churchill p. 46

* Requesting several thousand Turkish troops be sent to quell the uprising.

* Visiting the Mahdi himself to explore a possible solution.

Eventually it became impossible for Gordon to be relieved without British troops. An expedition was duly dispatched under Sir Garnet Wolseley

Field Marshal Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley, (4 June 183325 March 1913), was an Anglo-Irish officer in the British Army. He became one of the most influential and admired British generals after a series of successes in Canada, W ...

, but as the level of the White Nile fell through the winter, muddy 'beaches' at the foot of the walls were exposed. With starvation and cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

rampant in the city and the Egyptian troops' morale shattered, Gordon's position became untenable and the city fell on 26 January 1885, after a siege of 313 days.

Nile campaign

The British Government, reluctantly and late, but under strong pressure from public opinion, sent a relief column under Sir Garnet Wolseley to relieve the Khartoum garrison. This was described in some British papers as the 'Gordon Relief Expedition', a term Gordon strongly objected to. After defeating the Mahdists at theBattle of Abu Klea

The Battle of Abu Klea, or the Battle of Abu Tulayh took place between the dates of 16 and 18 January 1885, at Abu Klea, Sudan, between the British Desert Column and Mahdist forces encamped near Abu Klea. The Desert Column, a force of approxim ...

on 17 January 1885, the column arrived within sight of Khartoum at the end of January, only to find they were too late: the city had fallen two days earlier, and Gordon and the garrison had been massacred.

Suakin Expedition

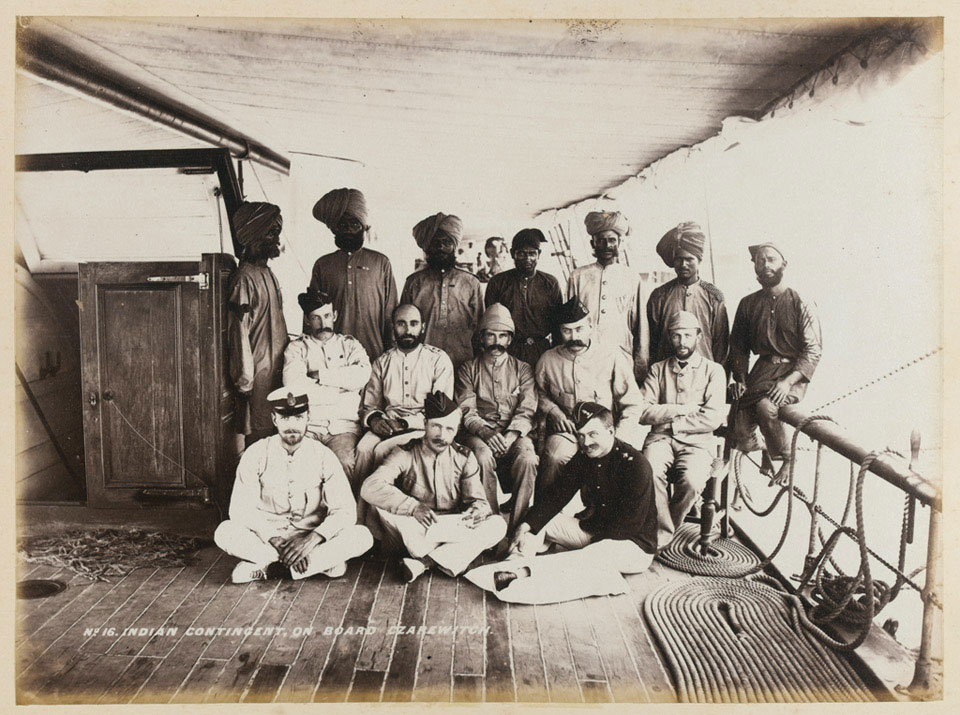

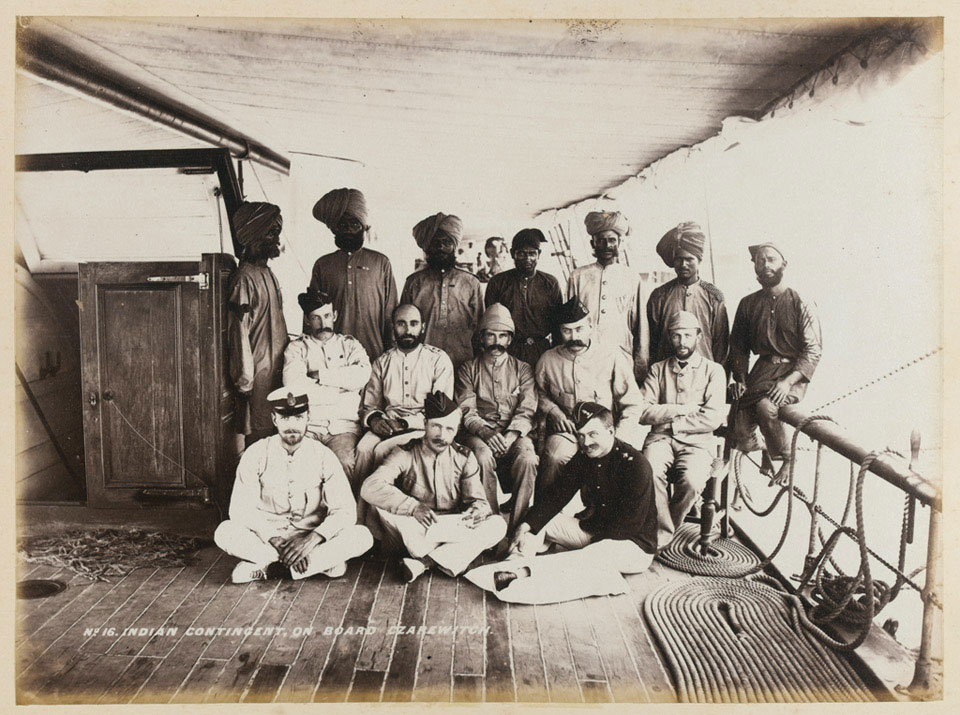

The British also sent an expeditionary force under Lieutenant-General Sir

The British also sent an expeditionary force under Lieutenant-General Sir Gerald Graham

Lieutenant General Sir Gerald Graham, (27 June 1831 – 17 December 1899) was a senior British Army commander in the late 19th century and an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that ...

, including an Indian contingent, to Suakin

Suakin or Sawakin ( ar, سواكن, Sawákin, Beja: ''Oosook'') is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about north.

Suakin used to b ...

in March 1885. Though successful in the two actions it fought, it failed to change the military situation and was withdrawn. These events temporarily ended British and Egyptian involvement in Sudan, which passed completely under the control of the Mahdists.

Muhammad Ahmad died soon after his victory, on 22 June 1885, and was succeeded by the Khalifa

Khalifa or Khalifah (Arabic: خليفة) is a name or title which means "successor", "ruler" or "leader". It most commonly refers to the leader of a Caliphate, but is also used as a title among various Islamic religious groups and others. Khalif ...

Abdallahi ibn Muhammad

Abdullah Ibn-Mohammed Al-Khalifa or Abdullah al-Khalifa or Abdallahi al-Khalifa, also known as "The Khalifa" ( ar, c. عبدالله بن سيد محمد الخليفة; 184625 November 1899) was a Sudanese Ansar ruler who was one of the principa ...

, who proved to be an able, albeit ruthless, ruler of the Mahdiyah (the Mahdist state).

Equatoria expedition

Between 1886 and 1889 a British expedition to relieve the Egyptian governor of Equatoria made its way through central Africa. The governor, Emin Pasha, was rescued, but the expedition was not without its failures, such as the disaster that befell the rear column.Ethiopian campaigns

According to theHewett Treaty

The Hewett Treaty, also called the Treaty of Adwa, was an agreement between Britain, Egypt and Ethiopia signed at Adwa on 3 June 1884. The treaty ended a long-simmering conflict between Egypt and Ethiopia, but indirectly started a new conflict bet ...

of 3 June 1884, Ethiopia agreed to facilitate the evacuation of Egyptian garrisons in southern Sudan. In September 1884, Ethiopia reoccupied the province of Bogos

The Bilen (also variously transcribed as Blin, and also formerly known as the Bogo, Bogos or North Agaw) are a Cushitic ethnic group in the Eritrea. They are primarily concentrated in central Eritrea, in and around the city of Keren and further s ...

, which had been occupied by Egypt, and began a long campaign to relieve the Egyptian garrisons besieged by the Mahdists. The bitter campaigning was led by the Emperor Yohannes IV

''girmāwī''His Imperial Majesty, spoken= am , ጃንሆይ ''djānhoi''Your Imperial Majesty(lit. "O steemedroyal"), alternative= am , ጌቶቹ ''getochu''Our Lord (familiar)(lit. "Our master" (pl.)) yohanes

Yohannes IV (Tigrinya: ዮሓ� ...

and Ras Alula

The alula , or bastard wing, (plural ''alulae'') is a small projection on the anterior edge of the wing of modern birds and a few non-avian dinosaurs. The word is Latin and means "winglet"; it is the diminutive of ''ala'', meaning "wing". The al ...

. The Ethiopians under Ras Alula achieved a victory in the Battle of Kufit

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

on 23 September 1885.

Between November 1885 and February 1886, Yohannes IV was putting down a revolt in Wollo

Wollo (Amharic: ወሎ) was a historical province of northern Ethiopia that overlayed part of the present day Amhara, Afar, and Tigray regions. During the Middle Ages this region was known as Bete Amhara and had Amhara kings. Bete Amhara had ...

. In January 1886, a Mahdist army invaded Ethiopia, seized Dembea

Dembiya (Amharic: ደምቢያ ''Dembīyā''; also transliterated Dembea, Dambya, Dembya, Dambiya, etc.) is a historic region of Ethiopia, intimately linked with Lake Tana. According to the account of Manuel de Almeida, Dembiya was "bounded on Ea ...

, burned the Mahbere Selassie monastery, and advanced on Chilga

Chilga (Amharic: ጭልጋ ''č̣ilgā'') also Chelga, Ch'ilga is a woreda in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. It is named after its chief town Chilga (also known as Ayikel), an important stopping point on the historic Gondar- Sudan trade route. Part o ...

. King Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam

Tekle Haymanot Tessemma, also known as Adal Tessemma, Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam, and Tekle Haimanot of Gojjam (1847 – 10 January 1901), was King of Gojjam. He later was an army commander and a member of the nobility of the Ethiopian Empire. ...

led a successful counteroffensive as far as Gallabat in the Sudan in January 1887. A year later, in January 1888, the Mahdists returned, defeating Tekle Haymanot at Battle of Sar Weha, Sar Weha and sacking Gondar. This culminated in the end of the Ethiopian theatre (warfare), theatre at the Battle of Gallabat

Italian campaign and Anglo-Egyptian reconquest

In the intervening years, Egypt had not renounced her claims over Sudan, and the British authorities considered these claims legitimate. Under strict control by British administrators, Egypt's economy had been rebuilt, and the Egyptian army reformed, this time trained and led by British officers and non-commissioned officers. The situation evolved in a way that allowed Egypt, both politically and militarily, to reconquer Sudan.

In the intervening years, Egypt had not renounced her claims over Sudan, and the British authorities considered these claims legitimate. Under strict control by British administrators, Egypt's economy had been rebuilt, and the Egyptian army reformed, this time trained and led by British officers and non-commissioned officers. The situation evolved in a way that allowed Egypt, both politically and militarily, to reconquer Sudan.

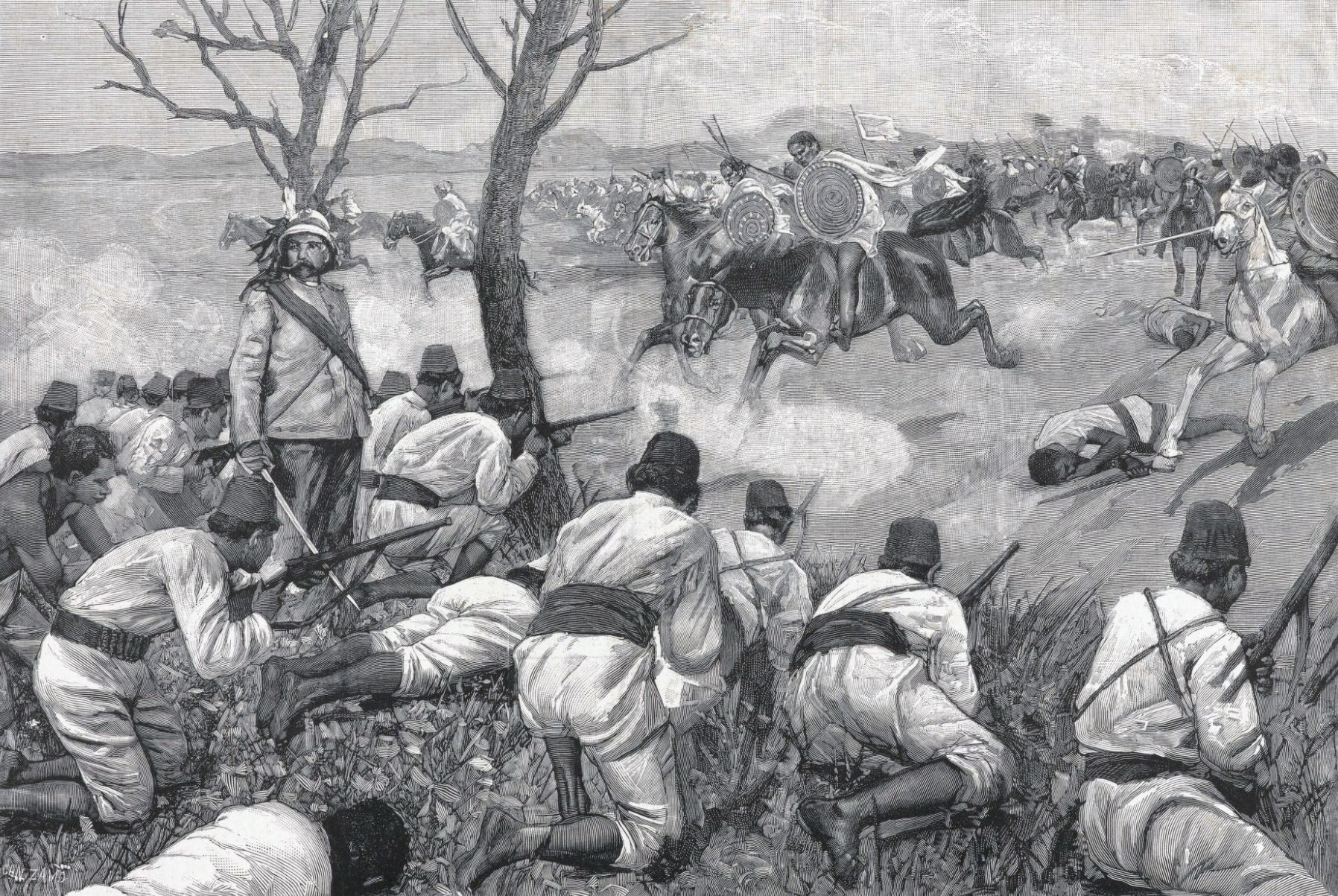

Since 1890, Italian Empire, Italian troops had defeated Mahdist troops in the Battle of Serobeti and the First Battle of Agordat. In December 1893, Italian colonial troops and Mahdists fought again in the Second Battle of Agordat; Ahmed Ali campaigned against the Italian forces in eastern Sudan and led about 10–12,000 men east from Kassala, encountering 2,400 Kingdom of Italy, Italians and their Eritrean Ascaris commanded by Colonel Arimondi. The Italians won again, and the outcome of the battle constituted "the first decisive victory yet won by Europeans against the Sudanese revolutionaries". A year later, Italian Eritrea, Italian colonial forces seized Kassala after the successful Battle of Kassala.

In 1891 a Catholic priest, Father Joseph Ohrwalder, escaped from captivity in Sudan. In 1895 the erstwhile Governor of Darfur, Rudolf Carl von Slatin, managed to escape from the Khalifa's prison. Besides providing vital intelligence on the Mahdist dispositions, both men wrote detailed accounts of their experiences in Sudan. Written in collaboration with Reginald Wingate, a proponent of the reconquest of Sudan, both works emphasized the savagery and barbarism of the Mahdists, and through the wide publicity they received in Britain, served to influence public opinion in favour of military intervention.

In 1896, when Italy suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the Ethiopians at Battle of Adwa, Adwa, the Italian position in East Africa was seriously weakened. The Mahdists threatened to retake Kassala, which they had lost to the Italians in 1894. The British government judged it politic to assist the Italians by making a military demonstration in northern Sudan. This coincided with the increased threat of French encroachment on the Upper Nile, Sudan, Upper Nile regions. Lord Cromer, judging that the Unionist government, 1895–1905, Conservative-Unionist government in power would favour taking the offensive, managed to extend the demonstration into a full-fledged invasion. In 1897, the Italians gave back to the British the control of Kassala, returning in Italian Eritrea, in order to get international recognition of their colony.

Since 1890, Italian Empire, Italian troops had defeated Mahdist troops in the Battle of Serobeti and the First Battle of Agordat. In December 1893, Italian colonial troops and Mahdists fought again in the Second Battle of Agordat; Ahmed Ali campaigned against the Italian forces in eastern Sudan and led about 10–12,000 men east from Kassala, encountering 2,400 Kingdom of Italy, Italians and their Eritrean Ascaris commanded by Colonel Arimondi. The Italians won again, and the outcome of the battle constituted "the first decisive victory yet won by Europeans against the Sudanese revolutionaries". A year later, Italian Eritrea, Italian colonial forces seized Kassala after the successful Battle of Kassala.

In 1891 a Catholic priest, Father Joseph Ohrwalder, escaped from captivity in Sudan. In 1895 the erstwhile Governor of Darfur, Rudolf Carl von Slatin, managed to escape from the Khalifa's prison. Besides providing vital intelligence on the Mahdist dispositions, both men wrote detailed accounts of their experiences in Sudan. Written in collaboration with Reginald Wingate, a proponent of the reconquest of Sudan, both works emphasized the savagery and barbarism of the Mahdists, and through the wide publicity they received in Britain, served to influence public opinion in favour of military intervention.

In 1896, when Italy suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the Ethiopians at Battle of Adwa, Adwa, the Italian position in East Africa was seriously weakened. The Mahdists threatened to retake Kassala, which they had lost to the Italians in 1894. The British government judged it politic to assist the Italians by making a military demonstration in northern Sudan. This coincided with the increased threat of French encroachment on the Upper Nile, Sudan, Upper Nile regions. Lord Cromer, judging that the Unionist government, 1895–1905, Conservative-Unionist government in power would favour taking the offensive, managed to extend the demonstration into a full-fledged invasion. In 1897, the Italians gave back to the British the control of Kassala, returning in Italian Eritrea, in order to get international recognition of their colony.

Herbert Kitchener, the new ''Sirdar (Egypt), Sirdar'' (commander) of the Anglo-Egyptian Army, received his marching orders on 12 March, and his forces entered Sudan on the 18th. Numbering at first 11,000 men, Kitchener's force was armed with the most modern military equipment of the time, including Maxim gun, Maxim machine-guns and modern artillery, and was supported by a flotilla of River gunboat, gunboats on the Nile. Their advance was slow and methodical, while fortified camps were built along the way, and two separate Narrow gauge railways were hastily constructed from a station at Wadi Halfa: the first rebuilt Isma'il Pasha's abortive and ruined former line south along the east bank of the Nile to supply the 1896 Dongola Expedition and a second, carried out in 1897, was extended along a new line directly across the desert to Abu Hamad—which they captured in the Battle of Abu Hamed on 7 August 1897—to supply the main force moving on Khartoum.Gleichen, Edward ed.

Herbert Kitchener, the new ''Sirdar (Egypt), Sirdar'' (commander) of the Anglo-Egyptian Army, received his marching orders on 12 March, and his forces entered Sudan on the 18th. Numbering at first 11,000 men, Kitchener's force was armed with the most modern military equipment of the time, including Maxim gun, Maxim machine-guns and modern artillery, and was supported by a flotilla of River gunboat, gunboats on the Nile. Their advance was slow and methodical, while fortified camps were built along the way, and two separate Narrow gauge railways were hastily constructed from a station at Wadi Halfa: the first rebuilt Isma'il Pasha's abortive and ruined former line south along the east bank of the Nile to supply the 1896 Dongola Expedition and a second, carried out in 1897, was extended along a new line directly across the desert to Abu Hamad—which they captured in the Battle of Abu Hamed on 7 August 1897—to supply the main force moving on Khartoum.Gleichen, Edward ed. The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: A Compendium Prepared by Officers of the Sudan Government

', Vol. 1, p. 99. Harrison & Sons (London), 1905. Accessed 13 February 2014.Sudan Railway Corporation.

". 2008. Accessed 13 February 2014. It was not until 7 June 1896 that the first serious engagement of the campaign occurred, when Kitchener led a 9,000 strong force that wiped out the Mahdist garrison at Battle of Ferkeh, Ferkeh.

In 1898, in the context of the scramble for Africa, the British decided to reassert Egypt's claim on Sudan. An expedition commanded by Kitchener was organised in Egypt. It was composed of 8,200 British soldiers and 17,600 Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers commanded by British officers. The Mahdist forces (sometimes called the Dervishes) were more numerous, numbering more than 60,000 warriors, but lacked modern weapons.

After defeating a Mahdist force in the Battle of Atbara in April 1898, the Anglo-Egyptians reached Omdurman, the Mahdist capital, in September. The bulk of the Mahdist army Battle of Omdurman, attacked, but was cut down by British machine-guns and rifle fire.

The remnant, with the Khalifa Abdullah, fled to southern Sudan. During the pursuit, Kitchener's forces met a French force under Major Jean-Baptiste Marchand at

In 1898, in the context of the scramble for Africa, the British decided to reassert Egypt's claim on Sudan. An expedition commanded by Kitchener was organised in Egypt. It was composed of 8,200 British soldiers and 17,600 Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers commanded by British officers. The Mahdist forces (sometimes called the Dervishes) were more numerous, numbering more than 60,000 warriors, but lacked modern weapons.

After defeating a Mahdist force in the Battle of Atbara in April 1898, the Anglo-Egyptians reached Omdurman, the Mahdist capital, in September. The bulk of the Mahdist army Battle of Omdurman, attacked, but was cut down by British machine-guns and rifle fire.

The remnant, with the Khalifa Abdullah, fled to southern Sudan. During the pursuit, Kitchener's forces met a French force under Major Jean-Baptiste Marchand at Fashoda

Kodok or Kothok ( ar, كودوك), formerly known as Fashoda, is a town in the north-eastern South Sudanese state of Upper Nile State. Kodok is the capital of Shilluk country, formally known as the Shilluk Kingdom. Shilluk had been an independ ...

, resulting in the Fashoda Incident. They finally caught up with Abdullah at Battle of Umm Diwaykarat, Umm Diwaykarat, where he was killed, effectively ending the Mahdist regime.

The casualties for this campaign were:

:Sudan: 30,000 dead, wounded, or captured

:Britain: 700+ British, Egyptian and Sudanese dead, wounded, or captured.

Aftermath

The British set up a new colonial system, the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Anglo-Egyptian administration, which effectively established British domination over Sudan. This ended with the independence of Sudan in 1956.Military textiles of the Mahdiyya

Textiles played an important role in the organisation of the Mahdist forces. The flags, banners, and patched tunics (''jibba'') worn and used in battle by the Ansar (Sudan), anṣār had both military and religious significance. As a result, textile items like these make up a large portion of the booty which was taken back to Britain after the British victory over the Mahdist forces at the Battle of Omdurman in 1899. Mahdist flags and ''jibbas'' were adapted from traditional styles of textiles used by adherents of Sufi orders in Sudan. As the Mahdist war progressed, these textiles became more standardised and specifically colour coded to denote military rank and regiment.Mahdist flags

The Mahdist ''jibba''

The patched ''muraqqa'a'', and later, the ''jibba'', was a garment traditionally worn by followers of Sufi religious orders. The ragged, patched garment symbolised a rejection of material wealth by its wearer and a commitment to a religious way of life. Muhammad Ahmad, Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi decreed that this garment should be worn by all his soldiers in battle. The decision to adopt the religious garment as military dress, enforced unity and cohesion among his forces, and eliminated traditional visual markers differentiating potentially fractious tribes. During the years of conflict between Mahdist and Anglo-Egyptian forces at the end of the 19th century, the Mahdist military ''jibba'' became increasingly stylised and patches became colour-coded to denote the rank and military division of the wearer.''Making African Connections''. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

See also

* History of Sudan (1884-1898) * Northern Africa Railroad Development * List of journalists killed during the Sudan campaign * :People of the Mahdist War * Millennarianism in colonial societiesReferences and notes

Footnotes

Citations

Further reading

Churchill, The River War

Too late for Gordon and Khartoum, 1887

Ten years captivity in the Mahdist camp

Suakin 1885

The Downfall of the Dervishes, 1898

Sudan Campaign 1896–1899

External links

The British Expedition to Rescue Emin Pasha

{{Authority control Mahdist War, African resistance to colonialism Wars involving the United Kingdom Wars involving Sudan Wars involving the states and peoples of Africa 19th-century military history of the United Kingdom Wars involving Egypt Rebellions in Africa Rebellions against the British Empire Wars involving British India 19th century in Egypt 19th century in Africa Proxy wars