Mackenzie Bowell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Mackenzie Bowell (; December 27, 1823 – December 10, 1917) was a Canadian newspaper publisher and politician, who served as the fifth

Bowell was born in

Bowell was born in

A keen supporter of the

A keen supporter of the

Bowell stayed in the Senate, serving as his party's leader there until 1906, and afterward as a regular Senator until his death in 1917, having served continuously for more than 50 years as a federal parliamentarian.

He died of

Bowell stayed in the Senate, serving as his party's leader there until 1906, and afterward as a regular Senator until his death in 1917, having served continuously for more than 50 years as a federal parliamentarian.

He died of

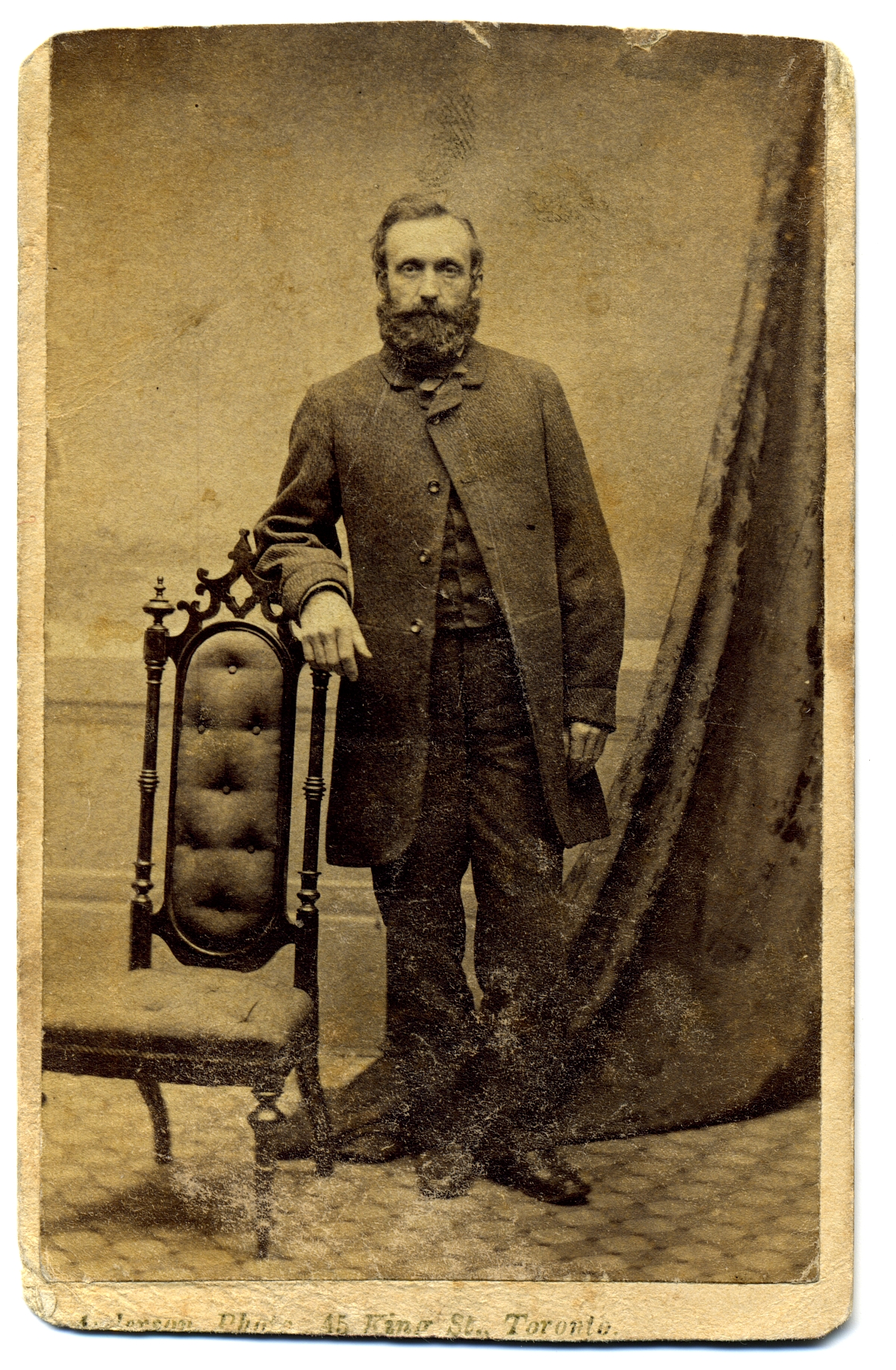

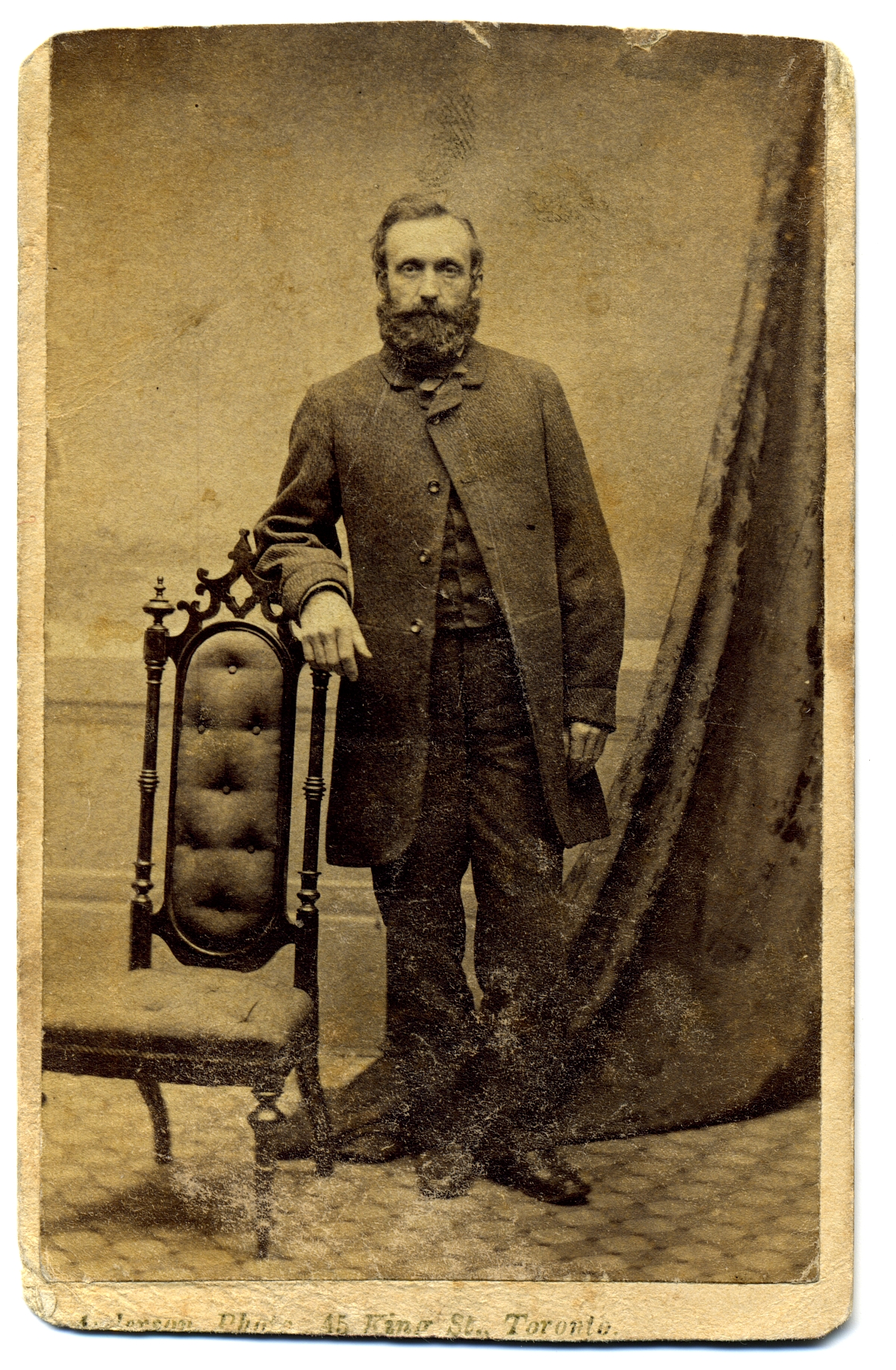

Photograph:Hon. Mackenzie Bowell, 1881

- McCord Museum {{DEFAULTSORT:Bowell, Mackenzie 1823 births 1917 deaths Canadian Ministers of Finance Canadian Ministers of Railways and Canals 19th-century Canadian newspaper publishers (people) Canadian Presbyterians Canadian senators from Ontario Deaths from pneumonia in Ontario English emigrants to pre-Confederation Ontario Conservative Party of Canada (1867–1942) senators Canadian Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Leaders of the Conservative Party of Canada (1867–1942) Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada People from Mid Suffolk District Politicians from Belleville, Ontario Prime Ministers of Canada Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Immigrants to Upper Canada Canadian Freemasons Argyll Light Infantry Canadian Militia officers Canadian Army officers Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment

prime minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority the elected Hou ...

, in office from 1894 to 1896.

Bowell was born in Rickinghall

Rickinghall is a village in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk, England. The village is split between two parishes, Rickinghall Inferior and Rickinghall Superior, which join with Botesdale to make a single built-up area.

There used to be many ...

, Suffolk, England. He and his family moved to Belleville, Ontario

Belleville is a city in Ontario, Canada situated on the eastern end of Lake Ontario, located at the mouth of the Moira River and on the Bay of Quinte. Belleville is between Ottawa and Toronto, along the Quebec City-Windsor Corridor. Its population ...

, in 1832. When in his early teens, Bowell was apprenticed to the printing shop of the local newspaper, the ''Belleville Intelligencer

''The Intelligencer'' (locally nicknamed the ''Intell'') is the daily (except on Sundays and certain holidays) newspaper of Belleville, Ontario, Canada. The paper is regarded mainly as a local paper, stressing local issues over issues of more na ...

'', and some 15 years later, became its owner and proprietor.

In 1867, following Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

, he was elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

for the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

. Bowell entered cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

in 1878, and would serve under three prime ministers: John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (January 10 or 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, he had a political career that sp ...

, John Abbott

Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott (March 12, 1821 – October 30, 1893) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the third prime minister of Canada from 1891 to 1892. He held office as the leader of the Conservative Party.

Abbot ...

, and John Thompson. He served variously as Minister of Customs The Minister of Customs was a position in the Cabinet of the Government of Canada responsible for the administration of customs revenue collection in Canada. This position was originally created by Statute 31 Vict., c. 43, and assented to on 22 M ...

(1878–1892), Minister of Militia and Defence

The Minister of Militia and Defence was the federal government minister in charge of the volunteer army units in Canada, the Canadian Militia.

From 1855 to 1906, the minister was responsible for Canadian militia units only, as the British Army wa ...

(1892), and Minister of Trade and Commerce (1892–1894). Bowell kept his Commons seat continuously for 25 years, through a period of Liberal Party rule in the 1870s. In 1892, Bowell was appointed to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. He became Leader of the Government in the Senate the following year.

In December 1894, Prime Minister Thompson unexpectedly died in office. The Earl of Aberdeen

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

, Canada's governor general

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

, appointed Bowell to replace Thompson as prime minister, due to his status as the most senior cabinet member. The main problem of Bowell's tenure as prime minister was the Manitoba Schools Question

The Manitoba Schools Question () was a political crisis in the Canadian province of Manitoba that occurred late in the 19th century, attacking publicly-funded separate schools for Roman Catholics and Protestants. The crisis was precipitated by a se ...

. His attempts at compromise alienated members of his own party, and following a Cabinet revolt in early 1896 he was forced to resign in favour of Charles Tupper

Sir Charles Tupper, 1st Baronet, (July 2, 1821 – October 30, 1915) was a Canadian Father of Confederation who served as the sixth prime minister of Canada from May 1 to July 8, 1896. As the premier of Nova Scotia from 1864 to 1867, he led ...

. Bowell stayed on as a senator until his death at the age of 93, but never again held ministerial office; he served continuously as a Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

parliamentarian for 50 years.

Early life, career, and family

Bowell was born in

Bowell was born in Rickinghall

Rickinghall is a village in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk, England. The village is split between two parishes, Rickinghall Inferior and Rickinghall Superior, which join with Botesdale to make a single built-up area.

There used to be many ...

, England, to John Bowell and Elizabeth Marshall. In 1832 his family emigrated to Belleville, Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

, where he apprenticed with the printer at the town newspaper, ''The Belleville Intelligencer

''The Intelligencer'' (locally nicknamed the ''Intell'') is the daily (except on Sundays and certain holidays) newspaper of Belleville, Ontario, Canada. The paper is regarded mainly as a local paper, stressing local issues over issues of more na ...

''. He became a successful printer and editor with that newspaper, and later its owner. He was a Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and an Orangeman, serving as grandmaster of the Orange Order of British North America, 1870–1878.

In 1847 he married Harriet Moore, with whom he had five sons and four daughters.

Military service

A keen supporter of the

A keen supporter of the militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

in Hastings County, he was appointed an Ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

in the 1st Belleville Militia on July 24, 1856. He helped organize the Belleville Volunteer Militia Rifle Company in 1857 with whom he served on active duty at Amherstburg

Amherstburg is a town near the mouth of the Detroit River in Essex County, Ontario, Canada. In 1796, Fort Malden was established here, stimulating growth in the settlement. The fort has been designated as a National Historic Site.

The town is ...

, Upper Canada, during the Trent Affair

The ''Trent'' Affair was a diplomatic incident in 1861 during the American Civil War that threatened a war between the United States and Great Britain. The U.S. Navy captured two Confederate envoys from a British Royal Mail steamer; the Brit ...

. He joined the 15th Belleville Battalion ( The Argyll Light Infantry) in 1863, being promoted to captain and fought in the Fenian Raids of 1866, serving at Prescott and being awarded the Canada General Service Medal

The Canada General Service Medal was a campaign medal awarded by the Canadian Government to both Imperial and Canadian forces for duties related to the Fenian raids between 1866 and 1871. The medal was initially issued in 1899 and had to be ap ...

. He was promoted to Major in the 49th (Hastings) Battalion of Rifles on February 22, 1867, and qualified for the First Class Certificate at the Military School of Instruction on March 1. He was promoted to Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel on February 22, 1872, and retired from the militia on March 24, 1874, with the rank of lieutenant-colonel in that regiment.

Elected to Parliament

Bowell was first elected to theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

in 1867 as a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

for the riding of Hastings North, Ontario. He held his seat for the Conservatives when they lost the election of January 1874, in the wake of the Pacific Scandal The Pacific Scandal was a political scandal in Canada involving bribes being accepted by 150 members of the Conservative government in the attempts of private interests to influence the bidding for a national rail contract. As part of British Colu ...

. Later that year he was instrumental in having Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of Canada and its first ...

expelled from the House.

Appointed to Cabinet, Senator

In 1878, with the Conservatives again governing, he joined the Cabinet as minister of customs. In 1892 he became minister of militia and defence, having held his Commons seat continuously for 25 years. A competent, hardworking administrator, Bowell remained in Cabinet as minister of trade and commerce, a newly created portfolio, after he became a senator that same year. His visit toAustralia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

in 1893 led to the first leaders' conference of British colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

and territories, held in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

in 1894. He became leader of the government in the Senate on October 31, 1893.

Prime minister (1894–1896)

In December 1894, Prime MinisterJohn Sparrow David Thompson

Sir John Sparrow David Thompson (November 10, 1845 – December 12, 1894) was a Canadian lawyer, judge and politician who served as the fourth prime minister of Canada from 1892 until his death. He had previously been fifth premier of Nova Sco ...

died suddenly, and Bowell, as the most senior Cabinet minister, was appointed in Thompson's stead by the Governor General. Bowell thus became the second of just two Canadian prime ministers (after John Abbott

Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott (March 12, 1821 – October 30, 1893) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the third prime minister of Canada from 1891 to 1892. He held office as the leader of the Conservative Party.

Abbot ...

) to hold that office while serving in the Senate rather than the House of Commons.

Manitoba Schools Question

As Prime Minister, Bowell faced theManitoba Schools Question

The Manitoba Schools Question () was a political crisis in the Canadian province of Manitoba that occurred late in the 19th century, attacking publicly-funded separate schools for Roman Catholics and Protestants. The crisis was precipitated by a se ...

. In 1890, Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

had abolished public funding for denominational schools, both Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, which many thought was contrary to the provisions made for denominational schools in the ''Manitoba Act

The ''Manitoba Act, 1870'' (french: link=no, Loi de 1870 sur le Manitoba)Originally entitled (until renamed in 1982) ''An Act to amend and continue the Act 32 and 33 Victoria, chapter 3; and to establish and provide for the Government of the Pro ...

'' of 1870. However, in a court challenge, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 Augus ...

held that Manitoba's abolition of public funding for denominational schools was consistent with the ''Manitoba Act'' provision. In a second court case, the Judicial Committee held that the federal Parliament had the authority to enact remedial legislation to force Manitoba to re-establish the funding.

Leadership crisis

Bowell and his predecessors struggled to solve this problem, which divided the country and even Bowell's own Cabinet. He was further hampered in his handling of the issue by his own indecisiveness on it and by his inability, as a senator, to take part in debates in the House of Commons. Bowell backed legislation, already drafted, that would have forced Manitoba to restore its Catholic schools, but then postponed it due to opposition within his Cabinet. With the ordinary business of government at a standstill, several members of Cabinet decided that Bowell was incompetent to lead. To force him to step down, seven ministers resigned and then foiled the appointment of successors. Bowell denounced them as "a nest of traitors".Resigns as prime minister

Bowell was forced to resign. After ten days, following an intervention on Bowell's behalf by the Governor General, the government crisis was resolved and matters seemingly returned to normal when six of the ministers were reinstated, but leadership was then effectively held byCharles Tupper

Sir Charles Tupper, 1st Baronet, (July 2, 1821 – October 30, 1915) was a Canadian Father of Confederation who served as the sixth prime minister of Canada from May 1 to July 8, 1896. As the premier of Nova Scotia from 1864 to 1867, he led ...

, who had joined Cabinet at the same time, filling the seventh place. Tupper, who had been Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, had been recalled by the plotters to replace Bowell. Bowell formally resigned in favour of Tupper at the end of the parliamentary session.

Later life, and death

Bowell stayed in the Senate, serving as his party's leader there until 1906, and afterward as a regular Senator until his death in 1917, having served continuously for more than 50 years as a federal parliamentarian.

He died of

Bowell stayed in the Senate, serving as his party's leader there until 1906, and afterward as a regular Senator until his death in 1917, having served continuously for more than 50 years as a federal parliamentarian.

He died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

in Belleville, seventeen days short of his 94th birthday. He was buried in the Belleville cemetery. His funeral was attended by a full complement of the Orange Order, but not by any currently or formerly elected member of the government.

Legacy

Bowell was designated a National Historic Person in 1945, on the advice of the national Historic Sites and Monuments Board. ThePost Office Department

The United States Post Office Department (USPOD; also known as the Post Office or U.S. Mail) was the predecessor of the United States Postal Service, in the form of a Cabinet department, officially from 1872 to 1971. It was headed by the postmas ...

honored Bowell with a commemorative stamp in 1954, part of a series on prime ministers.

In their 1998 study of the Canadian prime ministers up through Jean Chrétien

Joseph Jacques Jean Chrétien (; born January 11, 1934) is a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 20th prime minister of Canada from 1993 to 2003.

Born and raised in Shawinigan Falls, Quebec, Chrétien is a law graduate from Uni ...

, J. L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer found that a survey of Canadian historians ranked Bowell #19 out of the 20 Prime Ministers up until then.

Until 2017, Bowell remained the only Canadian prime minister without a full-length biography of his life and career. This shortfall was solved when the Belleville historian Betsy Dewar Boyce's book ''The Accidental Prime Minister'' was published by Bancroft, Ontario

Bancroft () is a town located on the York River in Hastings County in the Canadian province of Ontario. It was first settled in the 1850s by United Empire Loyalists and Irish immigrants. From the mid-1950s to about 1982, mining was the primary ...

publisher Kirby Books. The book was published on the centennial of Bowell's death. Boyce had died in 2007, having unsuccessfully sought a publisher for her work for a decade.

Supreme Court appointments

The following jurist was appointed to theSupreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC; french: Cour suprême du Canada, CSC) is the Supreme court, highest court in the Court system of Canada, judicial system of Canada. It comprises List of Justices of the Supreme Court of Canada, nine justices, wh ...

by the Governor General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

during Bowell's tenure:

* Désiré Girouard (September 28, 1895 – March 22, 1911)

See also

* List of prime ministers of CanadaArchives

There is a Sir Mackenzie Bowellfonds

In archival science, a fonds is a group of documents that share the same origin and that have occurred naturally as an outgrowth of the daily workings of an agency, individual, or organization. An example of a fonds could be the writings of a poe ...

at Library and Archives Canada

Library and Archives Canada (LAC; french: Bibliothèque et Archives Canada) is the federal institution, tasked with acquiring, preserving, and providing accessibility to the documentary heritage of Canada. The national archive and library is th ...

. It includes 6.1 m of textual records.

Further reading

''The Accidental Prime Minister'', by Betsy Dewar Boyce, 2017, Kirby Publishing,Bancroft, Ontario

Bancroft () is a town located on the York River in Hastings County in the Canadian province of Ontario. It was first settled in the 1850s by United Empire Loyalists and Irish immigrants. From the mid-1950s to about 1982, mining was the primary ...

, .

Notes

External links

* * *J. L. Granatstein

Jack Lawrence Granatstein (May 21, 1939) is a Canadian historian who specializes in Canadian political and military history.SeJack Granatsteinfrom The Canadian Encyclopedia

Education

Born on May 21, 1939, in Toronto, Ontario, into a Jewish fam ...

and Norman Hillmer, ''Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders'', Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., a Phyllis Bruce Book, 1999. pp. 42–44. .

* Photograph:Hon. Mackenzie Bowell, 1881

- McCord Museum {{DEFAULTSORT:Bowell, Mackenzie 1823 births 1917 deaths Canadian Ministers of Finance Canadian Ministers of Railways and Canals 19th-century Canadian newspaper publishers (people) Canadian Presbyterians Canadian senators from Ontario Deaths from pneumonia in Ontario English emigrants to pre-Confederation Ontario Conservative Party of Canada (1867–1942) senators Canadian Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Leaders of the Conservative Party of Canada (1867–1942) Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada People from Mid Suffolk District Politicians from Belleville, Ontario Prime Ministers of Canada Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Immigrants to Upper Canada Canadian Freemasons Argyll Light Infantry Canadian Militia officers Canadian Army officers Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment