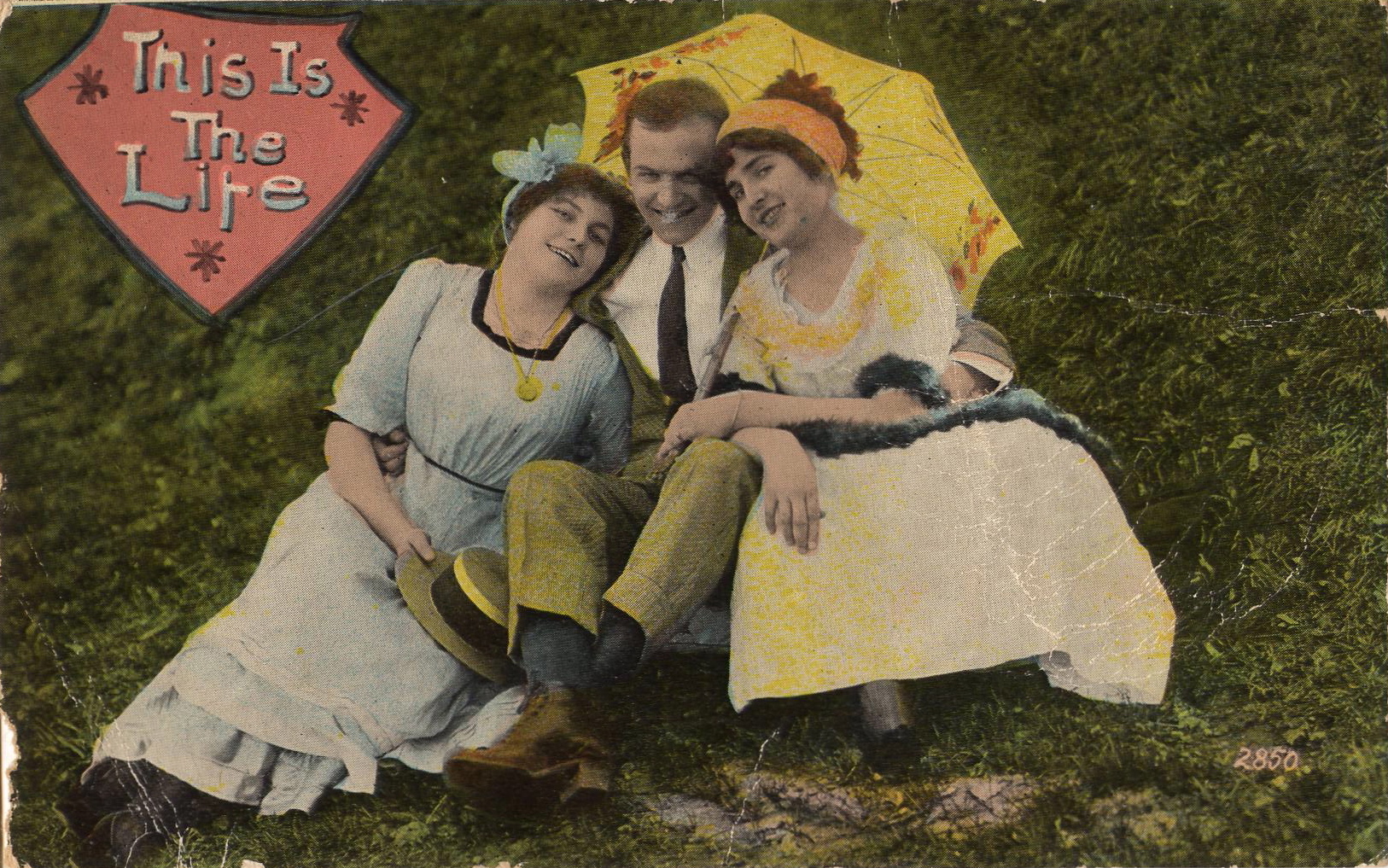

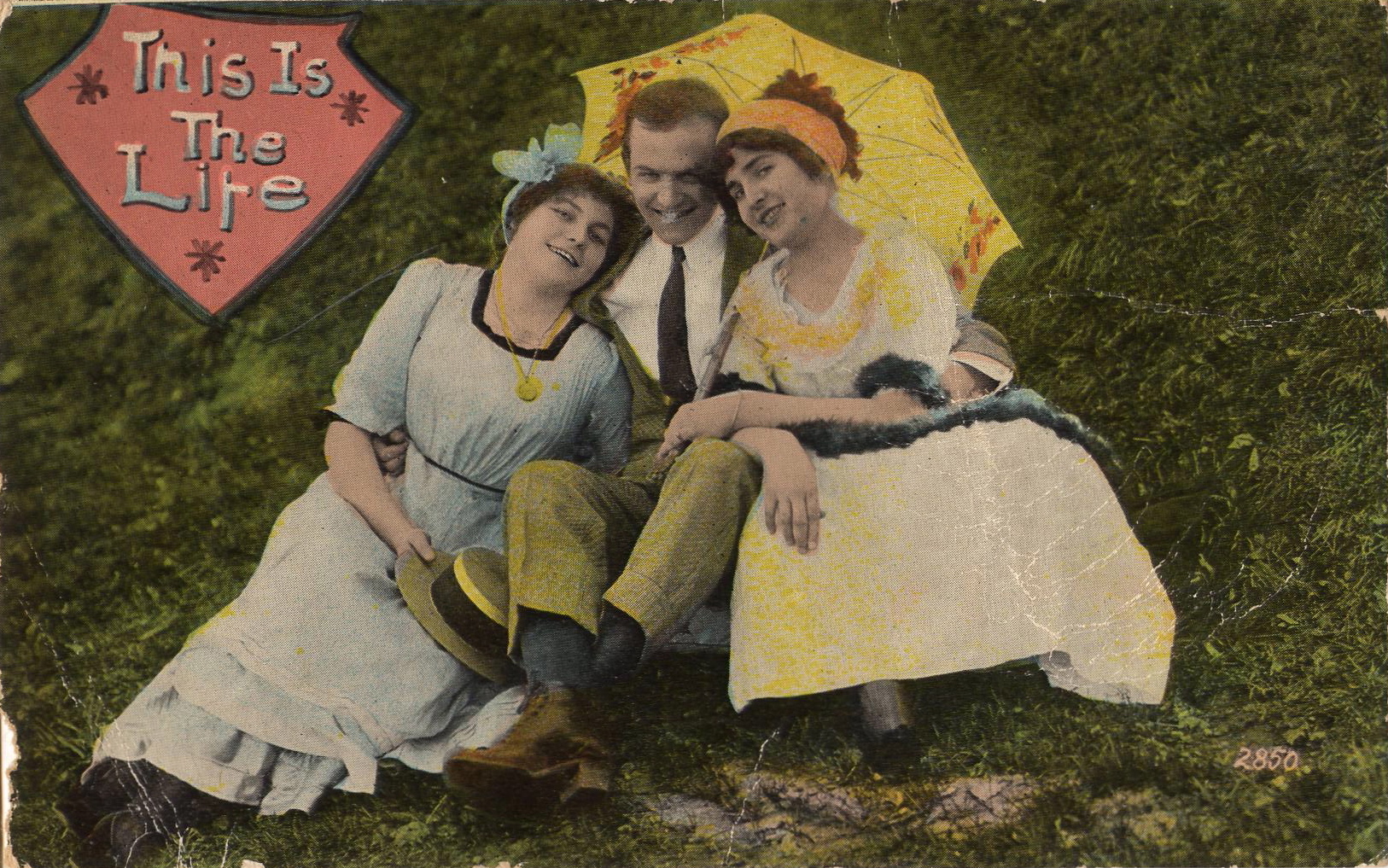

Ménage à Trois on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A () is a domestic arrangement and

A () is a domestic arrangement and

A () is a domestic arrangement and

A () is a domestic arrangement and committed relationship

A committed relationship is an interpersonal relationship based upon agreed-upon commitment to one another involving love, trust, honesty, openness, or some other behavior. Forms of committed relationships include close friendship, long-term rel ...

with three people in polyamorous romantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

or sexual relations with each other, and often dwelling together; typically a traditional marriage between a man and woman along with another individual. The phrase is a loan

In finance, a loan is the lending of money by one or more individuals, organizations, or other entities to other individuals, organizations, etc. The recipient (i.e., the borrower) incurs a debt and is usually liable to pay interest on that ...

from French meaning "household

A household consists of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling. It may be of a single family or another type of person group. The household is the basic unit of analysis in many social, microeconomic and government models, and is im ...

of three". Contemporary arrangements are sometimes identified as a throuple, thruple, or triad.Terminology

This relationship type has elements ofbisexual

Bisexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction or behavior toward both males and females, or to more than one gender. It may also be defined to include romantic or sexual attraction to people regardless of their sex or gender identity, wh ...

ity involved, but usually at least one of the participants is heterosexual

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" t ...

. Because this term is sometimes interchangeably used for a threesome

In human sexuality, a threesome is commonly understood as "a sexual interaction between three people whereby at least one engages in physical sexual behaviour with both the other individuals". Though ''threesome'' most commonly refers to sexua ...

, which solely refers to a sexual experience involving three people, it can sometimes be misrepresented as some type of perversion or casual encounter. However, the ''ménage à trois'' is a specific type of committed relationship, in which vows are often made. It doesn't apply to all polyamorous relationships with three individuals, since polyamory can have many different forms.

The topic sometimes overlaps seemingly opposing concepts such as Christian feminism

Christian feminism is a school of Christian theology which seeks to advance and understand the equality of men and women morally, socially, spiritually, and in leadership from a Christian perspective. Christian feminists argue that contribut ...

and Lesbian feminism

Lesbian feminism is a cultural movement and critical perspective that encourages women to focus their efforts, attentions, relationships, and activities towards their fellow women rather than men, and often advocates lesbianism as the log ...

. These ideas were explored by film maker Angel Robinson in her film ''Professor Marston and the Wonder Women

''Professor Marston and the Wonder Women'' is a 2017 American biographical drama film about American psychologist William Moulton Marston, who created the fictional character Wonder Woman. The film, directed and written by Angela Robinson, star ...

'' through the love story of historical couple William Moulton Marston

William Moulton Marston (May 9, 1893 – May 2, 1947), also known by the pen name Charles Moulton (), was an American psychologist who, with his wife Elizabeth Holloway, invented an early prototype of the lie detector. He was also known as a se ...

and Elizabeth Holloway Marston

Sarah Elizabeth Marston ( Holloway; February 20, 1893 – March 27, 1993) was an American attorney and psychologist. She is credited, with her husband William Moulton Marston, with the development of the systolic blood pressure measurement us ...

with their research assistant Olive Byrne

Mary Olive Byrne (), known professionally as Olive Richard (February 19, 1904 – May 19, 1990), was the domestic partner of William Moulton Marston and Elizabeth Holloway Marston. She has been credited as an inspiration for the comic book cha ...

.

Both the term and way of life have become a topic of discussion in areas associated with Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

and Romance languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language f ...

.

Examples

Ancient history

Biblical

This relationship type is very much rooted in the traditional marriage ideas of theAbrahamic

The Abrahamic religions are a group of religions centered around worship of the God of Abraham. Abraham, a Hebrew patriarch, is extensively mentioned throughout Abrahamic religious scriptures such as the Bible and the Quran.

Jewish tradition ...

faiths, Christian views on marriage

From the earliest days of the Christian faith, Christians have honored ''holy matrimony'' (as Christian marriages are referred to) as a divinely blessed, lifelong, monogamous union between a man and a woman. According to the Episcopal Book of C ...

are prevalent in literature and media discussing this topic.

The patriarchs Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrews, Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the Covenant (biblical), special ...

and Sarah

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch and prophetess, a major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a pio ...

had an arrangement similar to a ménage à trois with Sarah's handmaiden

A handmaiden, handmaid or maidservant is a personal maid or female servant. Depending on culture or historical period, a handmaiden may be of slave status or may be simply an employee. However, the term ''handmaiden'' generally implies lowly ...

Hagar

Hagar, of uncertain origin; ar, هَاجَر, Hājar; grc, Ἁγάρ, Hagár; la, Agar is a biblical woman. According to the Book of Genesis, she was an Egyptian slave, a handmaiden of Sarah (then known as ''Sarai''), whom Sarah gave to he ...

. Interpretations of this vary, for example Judaism and Islam treat it much more like a polygamous

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

situation, whereas Christian sources sometimes discuss the love triangle

A love triangle or eternal triangle is a scenario or circumstance, usually depicted as a rivalry, in which two people are pursuing or involved in a romantic relationship with one person, or in which one person in a romantic relationship with ...

aspect of it, which are not directly analogous with a ménage à trois. Similarly when Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam ...

married Leah

Leah ''La'ya;'' from (; ) appears in the Hebrew Bible as one of the two wives of the Biblical patriarch Jacob. Leah was Jacob's first wife, and the older sister of his second (and favored) wife Rachel. She is the mother of Jacob's first son ...

and Rachel

Rachel () was a Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban. Her older sister was Leah, Jacob's first wife. Her a ...

, the polygamy and love triangle angles are far more well researched than as a ménage à trois.

Christianity

Sappho

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an Archaic Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied ...

's writings influenced the early Christian church, and the topic of lesbianism within the ménage à trois framework of Christian couples began to be explored in post-Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

literature within Christian media

Christian media, sometimes referred to as inspirational, faith and family, or simply Christian, is a cross-media genre that features a Christian message or moral. Several creative studios and mass media formats are considered to be aspects of Ch ...

.

Post-Renaissance history

History has a number of examples of ''ménages à trois'' relationships. Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna, regent of Russia from 1740 to 1741, was involved simultaneously in affairs with the Saxon ambassador Count Moritz zu Lynar and herlady-in-waiting

A lady-in-waiting or court lady is a female personal assistant at a court, attending on a royal woman or a high-ranking noblewoman. Historically, in Europe, a lady-in-waiting was often a noblewoman but of lower rank than the woman to whom ...

Mengden. The regent's relationship with Mengden caused much disgust in Russia, and many believed her preoccupation with her relationships with Lynar and Mengden at the expense of governing made her a danger to the state. She was later overthrown in a coup.

In his youth, thirteen years her junior, the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revol ...

was a protégé

Mentorship is the influence, guidance, or direction given by a mentor. A mentor is someone who teaches or gives help and advice to a less experienced and often younger person. In an organizational setting, a mentor influences the personal and p ...

of the French noblewoman Françoise-Louise de Warens, who would become his first lover. He lived with her at her estate on and off since his teenage years, and in 1732, after he reached the age of 20, she initiated a sexual relationship with him while also being open about her sexual involvement with the steward of her house.

The German intellectual Dorothea von Rodde-Schlözer

Dorothea von Rodde-Schlözer (née Schlözer; 18 August 1770 – 12 July 1825) was a German scholar and the first woman to receive a doctor of philosophy degree in Germany. She was one of the so-called '' Universitätsmamsellen'', a group o ...

, her husband Mattheus Rodde and the French philosopher Charles de Villers also had a ''ménage à trois'' from 1794 until her husband's death in 1810.

Sir William Hamilton (British ambassador to Naples), his wife Emma Hamilton

Dame Emma Hamilton (born Amy Lyon; 26 April 176515 January 1815), generally known as Lady Hamilton, was an English maid, model, dancer and actress. She began her career in London's demi-monde, becoming the mistress of a series of wealthy m ...

, and her lover, the naval hero Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought ab ...

, were in a ''ménage à trois'' from 1799 until Nelson's death in 1805.

At the age of 16, in 1813, the future author of ''Frankenstein

''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' is an 1818 novel written by English author Mary Shelley. ''Frankenstein'' tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a sapient creature in an unorthodox scientific exp ...

'', Mary Godwin, eloped with her to-be husband Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his ach ...

and engaged in a ''ménage'' with Claire Clairmont

Clara Mary Jane Clairmont (27 April 1798 – 19 March 1879), or Claire Clairmont as she was commonly known, was the stepsister of the writer Mary Shelley and the mother of Lord Byron's daughter Allegra. She is thought to be the subject of a poe ...

, future lover of Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

, with whom the Shelleys would later have an extensive relationship.

The political philosopher Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Mary Burns and her sister

Who Was Wonder Woman? Long-Ago LAW Alumna Elizabeth Marston Was the Muse Who Gave Us a Superheroine

, ''Boston University Alumni Magazine'', Fall 2001.

/ref>Malcolm, Andrew H

''The New York Times'', 18 February 1992.

How this Brit wooed two gorgeous women into his ‘throuple’

''New York Daily News'' April 2015

David meets: the cutest throuple

''Bear World Magazine'' July 2016 {{DEFAULTSORT:Menage A Trois Intimate relationships Group sex 3 (number) Polyamory

'' Mary Burns and her sister

Lizzie

Lizzie or Lizzy is a nickname for Elizabeth or Elisabet, often given as an independent name in the United States, especially in the late 19th century.

Lizzie can also be the shortened version of Lizeth, Lissette or Lizette.

People

* Elizabeth ...

.

The Italian surrealist artist Leonor Fini

Leonor Fini (30 August 1907 – 18 January 1996) was an Argentinian born Italian surrealist painter, designer, illustrator, and author, known for her depictions of powerful and erotic women.

Early life

Fini was born in Buenos Aires, Argentin ...

(1907-1996) sustained a ''ménage à trois'' until her death with an Italian Count Stanislao Lepri and Polish writer Konstanty Jelenski in Paris. The relationship is believed to have impacted Fini's work as she depicts gender neutral individuals or figures where traditional gender roles are reversed with a passive male and dominant female, such as 'Woman Seated on Naked Man (1942)'.

The Belgian artist/illustrator Félicien Rops

Félicien Victor Joseph Rops (7 July 1833 – 23 August 1898) was a Belgian artist associated with Symbolism and the Parisian Fin-de Siecle. He was a painter, illustrator, caricaturist and a prolific and innovative print maker, particularly in ...

(1833–1898) maintained a remarkable ménage à trois with two sisters, Aurélie and Léontine Dulac, who ran a successful fashion house in Paris "Maison Dulac" They each bore a child with him (one died at an early age) and they lived together for over 25 years, until his death.

The author E. Nesbit lived with her husband Hubert Bland and his mistress Alice Hoatson, and raised their children as her own.

In 1913, psychoanalyst

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: + . is a set of Theory, theories and Therapy, therapeutic techniques"What is psychoanalysis? Of course, one is supposed to answer that it is many things — a theory, a research method, a therapy, a bo ...

Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung's work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, phil ...

began a relationship with a young patient, Toni Wolff, which lasted for some decades. Deirdre Bair, in her biography of Carl Jung, describes his wife Emma Jung as bearing up nobly as her husband insisted that Toni Wolff become part of their household, saying that Wolff was "his other wife".

The Russian and Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (, ; rus, Влади́мир Влади́мирович Маяко́вский, , vlɐˈdʲimʲɪr vlɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ məjɪˈkofskʲɪj, Ru-Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky.ogg, links=y; – 14 Apr ...

lived with Lilya Brik

Lilya Yuryevna Brik (alternatively spelled ''Lili'' or ''Lily''; russian: link=no, Ли́ля Ю́рьевна Брик; née Kagan; – August 4, 1978) was a Russian author and socialite, connected to many leading figures in the Russian avant ...

, who was considered his muse, and her husband Osip Brik

Osip Maksimovich Brik (russian: link=no, Óсип Макси́мович Брик) (16 January 1888 – 22 February 1945), was a Russian avant garde writer and literary critic, who was one of the most important members of the Russian formali ...

, an ''avant garde'' writer and critic.

Robert Graves and his wife Nancy Nicholson for some years attempted a triadic relationship called "The Trinity" with Laura Riding, a woman that Graves met and fell in love with in 1926. This triangle became the "Holy Circle" with the addition of Irish poet Geoffrey Phibbs

Jeoffrey "Geoffrey" Basil Phibbs (1900–1956) was an English-born Irish poet; he took his mother's name and called himself Geoffrey Taylor, after about 1930.

Phibbs was born in Smallburgh, Norfolk. He was brought up in Sligo, and educated i ...

, who himself was still married to Irish artist Norah McGuinness

Norah Allison McGuinness (7 November 1901 – 22 November 1980) was an Irish painter and illustrator.

Early life

Norah McGuinness was born in County Londonderry. She attended life classes at Derry Technical School and from 1921 studied at ...

.

As recounted by Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler, (, ; ; hu, Kösztler Artúr; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was a Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria. In 1931, Koestler join ...

in '' The Invisible Writing'', a conspicuous fixture of the intellectual life of 1930s Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

was a threesome—a husband, his wife and the wife's lover—who were writers and literary critics and had the habit of every day spending many hours, the three of them together, at one of the Hungarian capital's well known cafes. As noted by Koestler, their relationship was so open and had lasted so many years that it was no longer the subject of gossip.

The writer Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxle ...

and his first wife Maria engaged in a ''ménage'' with Mary Hutchinson, a friend of Clive Bell

Arthur Clive Heward Bell (16 September 1881 – 17 September 1964) was an English art critic, associated with formalism and the Bloomsbury Group. He developed the art theory known as significant form.

Biography Origins

Bell was born in East ...

.

From 1939, Erwin Schrödinger

Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander Schrödinger (, ; ; 12 August 1887 – 4 January 1961), sometimes written as or , was a Nobel Prize-winning Austrian physicist with Irish citizenship who developed a number of fundamental results in quantum theo ...

, his wife, Annemarie Bertel, and his mistress, Hilde March, had a ''ménage à trois''.

In 1963 the actress Hattie Jacques

Hattie Jacques (; born Josephine Edwina Jaques; 7 February 1922 – 6 October 1980) was an English comedy actress of stage, radio and screen. She is best known as a regular of the ''Carry On'' films, where she typically played strict, no-non ...

lived with her husband John Le Mesurier

John Le Mesurier (, born John Elton Le Mesurier Halliley; 5 April 191215 November 1983) was an English actor. He is perhaps best remembered for his comedic role as Sergeant Arthur Wilson in the BBC television situation ...

and her lover John Schofield.

Cultural instances

Folie à Deux

Folie à deux ('folly of two', or 'madness haredby two'), also known as shared psychosis or shared delusional disorder (SDD), is a collection of rare psychiatric syndromes in which symptoms of a delusional belief, and sometimes hallucinations, ...

winery has a popular set of wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from fermented grapes. Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are ...

s labeled as Ménage à Trois.

Wonder Woman

Wonder Woman is a superhero created by the American psychologist and writer William Moulton Marston (pen name: Charles Moulton), and artist Harry G. Peter. Marston's wife, Elizabeth, and their life partner, Olive Byrne, are credited as being ...

is based on two women that were in a real life ménage à trois, as featured in ''Professor Marston and the Wonder Women

''Professor Marston and the Wonder Women'' is a 2017 American biographical drama film about American psychologist William Moulton Marston, who created the fictional character Wonder Woman. The film, directed and written by Angela Robinson, star ...

'', the creator of the comic William Moulton Marston

William Moulton Marston (May 9, 1893 – May 2, 1947), also known by the pen name Charles Moulton (), was an American psychologist who, with his wife Elizabeth Holloway, invented an early prototype of the lie detector. He was also known as a se ...

and his legal wife Elizabeth Holloway Marston

Sarah Elizabeth Marston ( Holloway; February 20, 1893 – March 27, 1993) was an American attorney and psychologist. She is credited, with her husband William Moulton Marston, with the development of the systolic blood pressure measurement us ...

had a polyamorous life partner, Olive Byrne

Mary Olive Byrne (), known professionally as Olive Richard (February 19, 1904 – May 19, 1990), was the domestic partner of William Moulton Marston and Elizabeth Holloway Marston. She has been credited as an inspiration for the comic book cha ...

.Lamb, Marguerite.Who Was Wonder Woman? Long-Ago LAW Alumna Elizabeth Marston Was the Muse Who Gave Us a Superheroine

, ''Boston University Alumni Magazine'', Fall 2001.

/ref>Malcolm, Andrew H

''The New York Times'', 18 February 1992.

See also

*Bigamy

In cultures where monogamy is mandated, bigamy is the act of entering into a marriage with one person while still legally married to another. A legal or de facto separation of the couple does not alter their marital status as married persons. I ...

*Committed relationship

A committed relationship is an interpersonal relationship based upon agreed-upon commitment to one another involving love, trust, honesty, openness, or some other behavior. Forms of committed relationships include close friendship, long-term rel ...

* Gang bang

*Group sex

Group sex is sexual behavior involving more than two participants. Participants in group sex can be of any sexual orientation or gender. Any form of sexual activity can be adopted to involve more than two participants, but some forms have t ...

*Polyamory

Polyamory () is the practice of, or desire for, romantic relationships with more than one partner at the same time, with the informed consent of all partners involved. People who identify as polyamorous may believe in open relationships wi ...

*Polyandry

Polyandry (; ) is a form of polygamy in which a woman takes two or more husbands at the same time. Polyandry is contrasted with polygyny, involving one male and two or more females. If a marriage involves a plural number of "husbands and wives" ...

*Polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marri ...

*Polygyny

Polygyny (; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); ) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy around the world, entailing the marriage of a man with several women.

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any o ...

* Swinging

*Troilism

Paraphilias are sexual interests in objects, situations, or individuals that are atypical. The American Psychiatric Association

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the main professional organization of psychiatrists and trainee ...

References

Further reading

*Birbara Finocster, Michael Foster, Letha Friehakd. ''Three in Love: Ménages à trois from Ancient to Modern Times''. . *Vicki Vantoch. ''The Threesome Handbook: A Practical Guide to sleeping with three''. .External links

*How this Brit wooed two gorgeous women into his ‘throuple’

''New York Daily News'' April 2015

David meets: the cutest throuple

''Bear World Magazine'' July 2016 {{DEFAULTSORT:Menage A Trois Intimate relationships Group sex 3 (number) Polyamory