Myra Page on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dorothy Markey (born Dorothy Page Gary, 1897–1993), known by the pen name Myra Page, was a 20th-century American

Later in 1918, she taught school in

Later in 1918, she taught school in

Upon completing her master's degree in 1920, Page became a YWCA "industrial secretary" at a silk factory in

Upon completing her master's degree in 1920, Page became a YWCA "industrial secretary" at a silk factory in

During the 1930s, Page also taught school at the Writer's School, underwritten by the

During the 1930s, Page also taught school at the Writer's School, underwritten by the

In her memoir ''In a Generous Spirit'', Page states that both she and her husband were members of the nascent

In her memoir ''In a Generous Spirit'', Page states that both she and her husband were members of the nascent

In the same memoir, she states that they both worked in the Soviet underground, starting from their days in Russia (1932). She states that husband John Markey worked in agriculture and so came to meet and know

In the same memoir, she states that they both worked in the Soviet underground, starting from their days in Russia (1932). She states that husband John Markey worked in agriculture and so came to meet and know

Wisconsin Historical Society: undated photo of Myra Page

(includes photo)

Those Good Gertrudes

A Social History of Women Teachers in America - Author's Annotated Introduction to Manuscript Collections

Myra Page Papers, 1910-1990

at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill {{DEFAULTSORT:Page, Myra 20th-century American women writers 1897 births Columbia University alumni American feminist writers American communists Marxist feminists American socialist feminists 1993 deaths 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American short story writers American women novelists American women short story writers American women journalists Novelists from Virginia Journalists from Virginia University of Richmond alumni American people of Welsh descent People from Newport News, Virginia 20th-century American journalists

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

writer, journalist, union activist

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (su ...

, and teacher.

Background

Page was born Dorothy Page Gary on October 1, 1897, inNewport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the Uni ...

. Her father's ancestors, the Garys, came from Wales to the Tidewater region

Tidewater refers to the north Atlantic coastal plain region of the United States of America.

Definition

Culturally, the Tidewater region usually includes the low-lying plains of southeast Virginia, northeastern North Carolina, southern Mary ...

in the 1720. Her mother's ancestors, the Barhams, came to Jamestown, Virginia

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James (Powhatan) River about southwest of the center of modern Williamsburg. It was ...

. Her father Benjamin Roscoe Gary was a doctor, her mother Willie Alberta Barham an artist, and her home "affluent," "middle-class and progressive." Colgate Darden

Colgate Whitehead Darden Jr. (February 11, 1897 – June 9, 1981) was an American lawyer and Democratic politician aligned with the Byrd Organization who served as U.S. Representative from Virginia (1933–37, 1939–41), the 54th Governor of ...

was a friend of her brother Barham Gary: in her memoir, Page refers to him as "Clukey Darden."

In 1918, she received a bachelor's degree in English and history from Westhampton College (now the University of Richmond

The University of Richmond (UR or U of R) is a private liberal arts college in Richmond, Virginia. It is a primarily undergraduate, residential institution with approximately 4,350 undergraduate and graduate students in five schools: the School ...

).

Career

Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. In 1919, she started graduate studies at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. She studied anthropology under Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

, Melvin Herskovitz

Melvin is a masculine given name and surname, likely a variant of Melville and a descendant of the French surname de Maleuin and the later Melwin. It may alternatively be spelled as Melvyn or, in Welsh, Melfyn and the name Melivinia or Melva may b ...

, and Franklin Giddings (the last Marxian but not a communist). Both Boas and Herskovitz "challenged the prevailing theories about racial hierarchies." She also took a class under John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

at Columbia's Teacher's College

Teachers College, Columbia University (TC), is the graduate school of education, health, and psychology of Columbia University, a private research university in New York City. Founded in 1887, it has served as one of the official faculties ...

and attended courses given by theologians Harry Emerson Fosdick

Harry Emerson Fosdick (May 24, 1878 – October 5, 1969) was an American pastor. Fosdick became a central figure in the Fundamentalist–Modernist controversy within American Protestantism in the 1920s and 1930s and was one of the most prominen ...

and Henry F. Ward

Harry Frederick Ward Jr. (15 October 1873 – 9 December 1966) was an English-born American Methodist minister and political activist who identified himself with the movement for Christian socialism, best remembered as first national chairman of t ...

at Union Theological Seminary. In 1920, she obtained a masters with a thesis that analyzed the effect of New York newspaper coverage on the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. She also studied writing under Helen Hunter

Helen may refer to:

People

* Helen of Troy, in Greek mythology, the most beautiful woman in the world

* Helen (actress) (born 1938), Indian actress

* Helen (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Helen, ...

in the English department.

1920s

While a graduate student, she became active in theYoung Women's Christian Association

The Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) is a nonprofit organization with a focus on empowerment, leadership, and rights of women, young women, and girls in more than 100 countries.

The World office is currently based in Geneva, Swi ...

(YWCA), which at that time championed reform in race relations. Influenced by Social Gospel

The Social Gospel is a social movement within Protestantism that aims to apply Christian ethics to social problems, especially issues of social justice such as economic inequality, poverty, alcoholism, crime, racial tensions, slums, unclean envir ...

, she "developed an antiracist consciousness and chafed against the restrictions imposed upon her as a southern white woman."

Upon completing her master's degree in 1920, Page became a YWCA "industrial secretary" at a silk factory in

Upon completing her master's degree in 1920, Page became a YWCA "industrial secretary" at a silk factory in Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

, near her home town of Newport News and organized education for women workers.

Giddings had introduced Page to the Rand School of Social Science

The Rand School of Social Science was formed in 1906 in New York City by adherents of the Socialist Party of America. The school aimed to provide a broad education to workers, imparting a politicizing class-consciousness, and additionally served a ...

, where she had met Anna Louise Strong

Anna Louise Strong (November 24, 1885 – March 29, 1970) was an American journalist and activist, best known for her reporting on and support for communist movements in the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China.Archives West,Anna Loui ...

, Mary Heaton Vorse

Mary Heaton Vorse (October 11, 1874 – June 14, 1966) was an American journalist and novelist. She established her reputation as a journalist reporting the labor protests of a largely female and immigrant workforce in the east-coast textile indus ...

, and Scott Nearing

Scott Nearing (August 6, 1883 – August 24, 1983) was an American radical economist, educator, writer, political activist, pacifist, vegetarian and advocate of simple living.

Biography

Early years

Nearing was born in Morris Run, Tioga Coun ...

. In 1921, she returned to New York from Norfolk and studied further under Nearing at Rand; at that time, she first read the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party

''The Communist Manifesto'', originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (german: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is a political pamphlet written by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Comm ...

'' by Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' union organizer A union organizer (or union organiser in Commonwealth spelling) is a specific type of trade union member (often elected) or an appointed union official. A majority of unions appoint rather than elect their organizers. In some unions, the orga ...

for the (then pro-'' union organizer A union organizer (or union organiser in Commonwealth spelling) is a specific type of trade union member (often elected) or an appointed union official. A majority of unions appoint rather than elect their organizers. In some unions, the orga ...

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

) Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) was a United States labor union known for its support for "social unionism" and progressive political causes. Led by Sidney Hillman for its first thirty years, it helped found the Congress of Ind ...

(ACW). She chose amalgamated for its emphasis on Progressivism

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, tec ...

and education. Her first job was at a Wanamaker's

John Wanamaker Department Store was one of the first department stores in the United States. Founded by John Wanamaker in Philadelphia, it was influential in the development of the retail industry including as the first store to use price tags. ...

department store. Then the ACW helped her get work in a clothing sweatshop

A sweatshop or sweat factory is a crowded workplace with very poor, socially unacceptable or illegal working conditions. Some illegal working conditions include poor ventilation, little to no breaks, inadequate work space, insufficient lighting, o ...

; she attended an ACW-led strike. Page became a pants seamstress–good enough that the ACW sent her to New York City for training in making button holes. The ACW sent her with others to St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

, to help to unionize its biggest garment sweatshop, Curlee's. During a slump in 1923, she took a secretarial job and then returned home to Newport News for a few months. In the Spring of 1924, she returned to the New York area and got a job as a schoolteacher of American History in Teaneck, New Jersey

Teaneck () is a Township (New Jersey), township in Bergen County, New Jersey, Bergen County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is a bedroom community in the New York metropolitan area. As of the 2010 United States census, 2010 U.S. census, th ...

. There, "I joined the New York City Local of the American Federation of Teachers

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) is the second largest teacher's labor union in America (the largest being the National Education Association). The union was founded in Chicago. John Dewey and Margaret Haley were founders.

About 60 perc ...

and quickly became one of its leaders. (By "Local," Page is clearly referring to Local 5 AFT, AKA the New York City Teachers Union

The New York City Teachers Union or "TU" (1916–1964) was the first New York labor union for teachers, formed as "AFT Local 5" of the American Federation of Teachers, which found itself hounded throughout its history due largely to co-membership ...

.)

In fall 1924, she got a teaching fellowship in the History Department of the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Tw ...

, chaired by F. Stuart Chapin. Pitirim Sorokin

Pitirim Alexandrovich Sorokin (; russian: Питири́м Алекса́ндрович Соро́кин; – 10 February 1968) was a Russian American sociologist and political activist, who contributed to the social cycle theory.

Background

...

, former secretary to Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; Reforms of Russian orthography, original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months ...

and Menshevik

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

leader, was a professor there. She married fellow teacher and fellow John Markey

David John Markey (October 7, 1882 – July 20, 1963) was an American politician, Army officer, businessman, and college football coach. He ran a controversial unsuccessful campaign for a United States Senate seat against former Maryland governor ...

, and together they joined the American Federation of Teachers

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) is the second largest teacher's labor union in America (the largest being the National Education Association). The union was founded in Chicago. John Dewey and Margaret Haley were founders.

About 60 perc ...

union there. They both encouraged garment workers to unionize in the Twin Cities

Twin cities are a special case of two neighboring cities or urban centres that grow into a single conurbation – or narrowly separated urban areas – over time. There are no formal criteria, but twin cities are generally comparable in statu ...

area (Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins ...

and St. Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

).

In June 1926, as a member of the American Federal of Teachers union, she attended a convention of the Trade Union Education League. Participants included William Z. Foster and John Jonstone. Also in June 1926, she took a class (Page and Nearing called it the Labor Research Study Group) under Nearing that sought a "law of social revolution" (though, according to Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938), ...

, "an infiltration of Communists... really ran the class, steered the discussions," and tried to "make the law of social revolution a Marxian law.") Nearing focused on the Soviet Union; Page wrote about India and the English Revolution of 1642. According to Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938), ...

(but not Page), their classmates included: Page, Chambers, Sam Krieger

Samuel Krieger (1902-1981) was an American union organizer, IWW member, Teamsters member, and communist.

Life

Background

Samuel Krieger was born in Russia on August 20, 1902. He came with his family to the United States at age two. He grew u ...

, Eve Dorf and her husband Ben Davidson

Benjamin Earl Davidson (June 14, 1940 – July 2, 2012) was an American football player, a defensive end best known for his play with the Oakland Raiders in the American Football League (AFL). Earlier in his career, he was with the Green Bay ...

,

as well as Alfred J. Brooks, Dale Zysman

Jack Hardy (sometimes Richard Enmale), born Dale Zysman (November 18, 1901 - July 2, 1993?), was a 20th-Century Communist author labor leader as "Jack Hardy" and a teacher and board member of the New York City Teachers Union under his birth name " ...

, Benjamin Mandel, and Rachel Ragozin. In July–September, 1926, she attended first an International Teachers' Union conference in Vienna, Austria, several related teachers' union conferences in Paris, France, and then, with Nearing, a British trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

Conference in the UK. After passing through New York City, in part to publish her book with Nearing, ''The Law of Social Revolution'', via the Federated Press

''This is not to be confused with the independent, research-based organization of Toronto, Canada, also called that targets executives, lawyers, professionals.''

The Federated Press was a left wing news service, established in 1920, that provided ...

, she returned to Minneapolis by late September to reunite with her husband. They immediately set about a "central trade union committee" of the Minnesota AFL

AFL may refer to:

Sports

* American Football League (AFL), a name shared by several separate and unrelated professional American football leagues:

** American Football League (1926) (a.k.a. "AFL I"), first rival of the National Football Leagu ...

and commenced "workers' education" in Duluth

, settlement_type = City

, nicknames = Twin Ports (with Superior), Zenith City

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top: urban Duluth skyline; Minnesota ...

.

In June 1928, Page earned her PhD in Sociology with double minor in Economics and Psychology from the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Tw ...

. In the fall of 1928, she accepted a teaching position at Wheaton College (Massachusetts)

Wheaton College is a private liberal arts college in Norton, Massachusetts. Wheaton was founded in 1834 as a female seminary. The trustees officially changed the name of the Wheaton Female Seminary to Wheaton College in 1912 after receiving ...

, while her husband had started another a year earlier at Connecticut College

Connecticut College (Conn College or Conn) is a private liberal arts college in New London, Connecticut. It is a residential, four-year undergraduate institution with nearly all of its approximately 1,815 students living on campus. The college w ...

. In 1926, the YWCA had helped fund her research on working conditions among garment workers in Greenville and Gastonia, North Carolina, and in 1929 again funded her to rewrite her doctoral thesis as ''Southern Cotton Mills and Labor'' (1929): "Many lines and quotes... appear later in my Gastonia novel, ''Gathering Storm''.

On March 30, 1929, the Loray Mill strike

The Loray Mill strike of 1929 in Gastonia, North Carolina, was a notable strike action in the labor history of the United States. Though largely unsuccessful in attaining its goals of better working conditions and wages, the strike was considered ...

(also known as the "Gastonia Strike") broke out and lasted into August; Sophie Melvin (future wife of Simon Gerson) traveled there to join Fred Beal

Fred Erwin Beal (1896–1954) was an American labor-union organizer whose critical reflections on his work and travel in the Soviet Union divided left-wing and liberal opinion. In 1929 he had been a ''cause célèbre'' when, in Gastonia, North Car ...

in organizing strikers on behalf of the Communist Party controlled National Textile Workers Union. In fall 1929, her husband joined Wheaton College as head of her Sociology Department. In October 1929, Page was one of scores of founding members of the John Reed Clubs

The John Reed Clubs (1929–1935), often referred to as John Reed Club (JRC), were an American federation of local organizations targeted towards Marxist writers, artists, and intellectuals, named after the American journalist and activist John ...

. Her "group" included: Grace Lumpkin

Grace Lumpkin (March 3, 1891 – March 23, 1980) was an American writer of proletarian literature, focusing most of her works on the Depression era and the rise and fall of favor surrounding communism in the United States. Most important of fou ...

, Katharine DuPre Lumpkin, Dorothy Douglas, Ben Appel, Sophie Appel (and probably Agnes Smedley

Agnes Smedley (February 23, 1892 – May 6, 1950) was an American journalist, writer, and activist who supported the Indian Independence Movement and the Chinese Communist Revolution. Raised in a poverty-stricken miner's family in Missouri and Co ...

who also knew most of these people). During the Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

that started October 28–29, 1929, Page had just started working as a journalist for ''Labor Age

''Labor Age'' was a monthly political magazine published from 1922 to 1933. The publisher was by the Labor Publication Society.

History

Establishment

''Labor Age'' succeeded the ''Socialist Review'', journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist So ...

'', the ILD

ILD may refer to:

Organizations

* Independent Lutheran Diocese a small Confessional Lutheran Association in the United States.

* International Liaison Department of the Chinese Communist Party, a minister-level department of the Chinese gover ...

's ''Labor Defender'', and ''Southern Woman'' magazines. Some time in 1929, Page (along with Grace Lumpkin

Grace Lumpkin (March 3, 1891 – March 23, 1980) was an American writer of proletarian literature, focusing most of her works on the Depression era and the rise and fall of favor surrounding communism in the United States. Most important of fou ...

and Olive Dargin and three others) began novels about the Gastonia Strike: Page's novel was ''Gathering Storm: A Story of the Black Belt'', published in 1932.

1930s

At the end of the 1929–1930 academic year, Page and her husband left Wheaton College. During the 1930s, Page was a political journalist and writer. She wrote for ''Southern Workman'', ''Working Woman'', and the CPUSA newspaper ''TheDaily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were m ...

''. In 1931, she became editor for the ''New Pioneer'' monthly magazine for Communist children (1931–1938), published by Young Communist League USA

The Young Communist League USA (YCLUSA) is a communist youth organization in the United States. The stated aim of the League is the development of its members into Communists, through studying Marxism–Leninism and through active participation ...

. She recruited her brother Barham and sister Bert to contribute stories. In May 1931, she traveled with William Z. Foster to hear him advocate that the United Mine Workers

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unit ...

union split off from the AFL

AFL may refer to:

Sports

* American Football League (AFL), a name shared by several separate and unrelated professional American football leagues:

** American Football League (1926) (a.k.a. "AFL I"), first rival of the National Football Leagu ...

. Page quarreled with Foster over his position but did cover the strike in the July 1931 issue.

Page's husband John Markey joined the Labor Research Association (LRA), for which he contributed writings under the pseudonym "John Barnett" for "several years." LRA's directors included: Anna Rochester

Anna Rochester (March 30, 1880 — May 11, 1966) was an American labor reformer, journalist, political activist, and Communist. Although for several years an editor of the liberal monthly '' The World Tomorrow,'' Rochester is best remembered as a ...

, Bill Dunne, Grace Hutchins

Grace Hutchins (August 19, 1885 – July 15, 1969) was an American labor reformer and researcher, journalist, political activist and communist. She spent many years of her life writing about labor and economics, in addition to being a lifelong ded ...

, Carl Haessler Carl Haessler (1888–1972) was an American political activist, conscription resister, newspaper editor, and trade union organizer. He is best remembered as an imprisoned conscientious objector during World War I and as the longtime head of the Fede ...

, and Charlotte Todes Stern. Edward Dahlberg

Edward Dahlberg (July 22, 1900 – February 27, 1977) was an American novelist, essayist, and autobiographer.

Background

Edward Dahlberg was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to Elizabeth Dahlberg. Together, mother and son led a vagabond existence ...

was another contributor. Markey also helped "organize automotive and transportation workers. It was good experience... but organizing was not his forté. He was already best at academic teaching and research.") As "John Barnett," John Markey also contributed articles to ''The Communist'', 1933–1935.

Page spent two years in Moscow, whence she wrote for American socialist journals as well as the Soviet communist publication ''Moscow News

''The Moscow News'', which began publication in 1930, was Russia's oldest English-language newspaper. Many of its feature articles used to be translated from the Russian language ''Moskovskiye Novosti.''

History Soviet Union

In 1930 ''The Mo ...

''. She also wrote her novel ''Moscow Yankee'' (1935) there.

Upon their return to the States around November 1933, when the US recognized the USSR diplomatically, Page and her husband lived in Brooklyn, NY. Page joined the editorial board of ''Soviet Russia Today'', a Soviet-backed magazine edited by Jessica Smith, wife of Harold Ware

Harold or "Hal" Ware (August 19, 1889 – August 14, 1935) was an American Marxist, regarded as one of the Communist Party's top experts on agriculture.

He was employed by a federal New Deal agency in the 1930s. He is alleged to have been a S ...

.

On May 1, 1935, Page joined the League of American Writers

The League of American Writers was an association of American novelists, playwrights, poets, journalists, and literary critics launched by the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) in 1935. The group included Communist Party members, and so-called " fell ...

(1935–1943), whose members included Alexander Trachtenberg

Alexander "Alex" Trachtenberg (23 November 1884 – 26 December 1966) was an American publisher of radical political books and pamphlets, founder and manager of International Publishers of New York. He was a longtime activist in the Socialist Part ...

of International Publishers

International Publishers is a book publishing company based in New York City, specializing in Marxism, Marxist works of economics, political science, and history.

Company history

Establishment

International Publishers Company, Inc., was founded ...

, Frank Folsom, Louis Untermeyer

Louis Untermeyer (October 1, 1885 – December 18, 1977) was an American poet, anthologist, critic, and editor. He was appointed the fourteenth Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1961.

Life and career

Untermeyer was born in New Y ...

, Bromfelds, I. F. Stone, Millen Brand

Millen Brand (January 19, 1906 – March 19, 1980) was an American writer and poet. His novels, ''The Outward Room'' (1938) and ''Savage Sleep'' (1968), addressed mental health institutions and were bestsellers in their day.

Personal life

B ...

, Arthur Miller

Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist and screenwriter in the 20th-century American theater. Among his most popular plays are '' All My Sons'' (1947), ''Death of a Salesman'' ( ...

, Lillian Hellman

Lillian Florence Hellman (June 20, 1905 – June 30, 1984) was an American playwright, prose writer, memoirist and screenwriter known for her success on Broadway, as well as her communist sympathies and political activism. She was blacklisted aft ...

, and Dashiell Hammett

Samuel Dashiell Hammett (; May 27, 1894 – January 10, 1961) was an American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. He was also a screenwriter and political activist. Among the enduring characters he created are Sam Spade ('' ...

. Members were largely either Communist Party members or fellow travelers

The term ''fellow traveller'' (also ''fellow traveler'') identifies a person who is intellectually sympathetic to the ideology of a political organization, and who co-operates in the organization's politics, without being a formal member of that o ...

. Aline Bernstein

Aline Bernstein (December 22, 1880 – September 7, 1955) was an American set designer and costume designer. She and Irene Lewisohn founded the Museum of Costume Art. Bernstein was the lover, patron, and muse of novelist Thomas Wolfe.

Early life

...

(mistress of Thomas Wolfe

Thomas Clayton Wolfe (October 3, 1900 – September 15, 1938) was an American novelist of the early 20th century.

Wolfe wrote four lengthy novels as well as many short stories, dramatic works, and novellas. He is known for mixing highly origin ...

) often hosted them at her home.

Starting in August 1935, Page's husband spent a year (again as "John Barnett") as dean of Commonwealth College, a workers' school in Mena, Arkansas

Mena ( ) is a city in Polk County, Arkansas, United States. It is also the county seat of Polk County. The population was 5,558 as of the 2020 census. Mena is included in the Ark-La-Tex socio-economic region. Surrounded by the Ouachita National F ...

, while Page taught English writing and literature. Page met FLOTUS Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

when she came to visit the college.

In March 1937, she interviewed Andre Malraux for his views on the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

and Hallie Flanagan

Hallie Flanagan Davis (August 27, 1889 in Redfield, South Dakota – June 23, 1969 in Old Tappan, New Jersey) was an American theatrical producer and director, playwright, and author, best known as director of the Federal Theatre Project, a pa ...

about the Federal Theatre Project

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP; 1935–1939) was a theatre program established during the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depression as part of the New Deal to fund live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United ...

.

League of American Writers

The League of American Writers was an association of American novelists, playwrights, poets, journalists, and literary critics launched by the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) in 1935. The group included Communist Party members, and so-called " fell ...

(itself established by the Party) and based in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

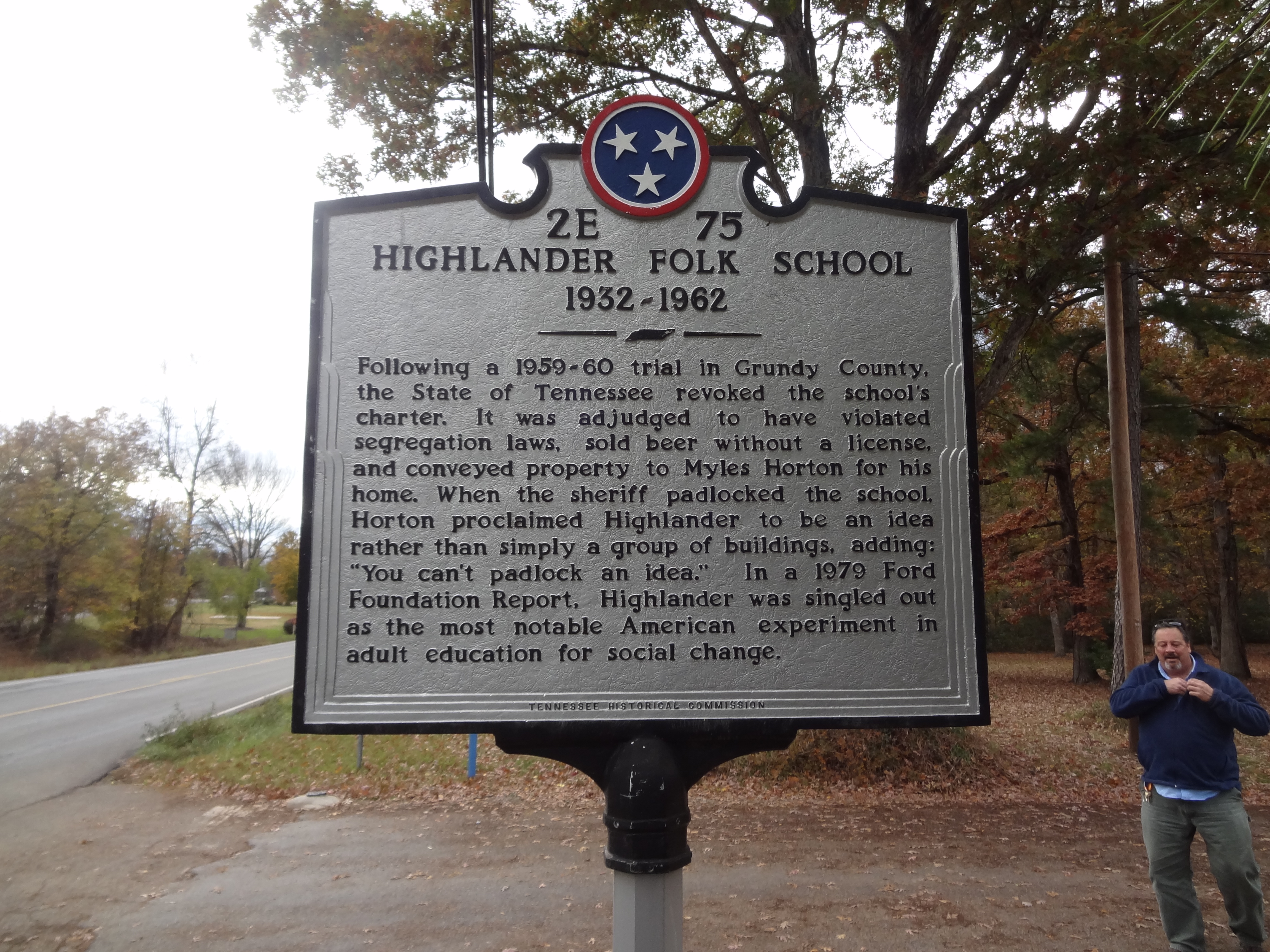

. In 1937, husband John Markey got a job as educational director of the Transportation Workers Union (TWU), a CIO member headed by Mike Quill. In the summers of 1938 and 1939, Page taught at the Highlander Folk School

The Highlander Research and Education Center, formerly known as the Highlander Folk School, is a social justice leadership training school and cultural center in New Market, Tennessee. Founded in 1932 by activist Myles Horton, educator Don West (e ...

in Grundy County, Tennessee

Grundy County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is located in Middle Tennessee, bordering East Tennessee. As of 2021, the population was 13,622. Its county seat is Altamont. The county is named in honor of Felix Grundy.

...

.

Later life

In the 1940s, she continued to teach at the Writer's School. In the 1950s and 1960s, she wrote biographies for juveniles under her married name "Dorothy Markey."Communism

Party membership

Communist Party of the USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

. She does not state when, but from her description it seems they joined in 1928 during the height of factionalism within the Party between followers of Jay Lovestone

Jay Lovestone (15 December 1897 – 7 March 1990) was an American activist. He was at various times a member of the Socialist Party of America, a leader of the Communist Party USA, leader of a small oppositionist party, an anti-Communist and Centr ...

, James P. Cannon, and William Z. Foster (described at some length in the memoir of Whittaker Chambers). Page states that she and her husband supported Foster because "he was a union man."

By the Fall of 1930, after they had let their contracts to teach expire at Wheaton College, her husband "John and I began to work full-time for the movement," i.e., for the Party. In 1931, she became editor for the ''New Pioneer'' monthly magazine for Communist children (1931–1938), published by Young Communist League USA

The Young Communist League USA (YCLUSA) is a communist youth organization in the United States. The stated aim of the League is the development of its members into Communists, through studying Marxism–Leninism and through active participation ...

.

Moscow

Page and her husband first traveled to Moscow in the summer of 1928 (crossing Europe on foot), where they joined a group of visitors led byJohn Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

. They went again in September 1931 by ship in the company of Gastonia strike leader Fred Beal

Fred Erwin Beal (1896–1954) was an American labor-union organizer whose critical reflections on his work and travel in the Soviet Union divided left-wing and liberal opinion. In 1929 he had been a ''cause célèbre'' when, in Gastonia, North Car ...

of the National Textile Workers Union returning to Soviet exile after an undercover visit to the United States where, in 1929, he had been convicted in Gastonia for conspiracy in the strike related death of a policeman. Beal was later to write disaparagingly of those westerners who, like Page, were made comfortable in Moscow by the party-state bureaucracy he identified as a "new exploiting class".

Page stayed through mid-year 1933, by which time Beal in Kharkov, but not she in Moscow, witnessed the famine produced by Stalin's collectivisation policies.

Soviet espionage

In the same memoir, she states that they both worked in the Soviet underground, starting from their days in Russia (1932). She states that husband John Markey worked in agriculture and so came to meet and know

In the same memoir, she states that they both worked in the Soviet underground, starting from their days in Russia (1932). She states that husband John Markey worked in agriculture and so came to meet and know Harold Ware

Harold or "Hal" Ware (August 19, 1889 – August 14, 1935) was an American Marxist, regarded as one of the Communist Party's top experts on agriculture.

He was employed by a federal New Deal agency in the 1930s. He is alleged to have been a S ...

(founder of the Ware Group

The Ware Group was a covert organization of Communist Party USA operatives within the United States government in the 1930s, run first by Harold Ware (1889–1935) and then by Whittaker Chambers (1901–1961) after Ware's accidental death on Augus ...

which Whittaker Chambers took over upon Ware's death in 1935). Page is clear about joining the Soviet underground: While we were in the Soviet Union, John and I worked with the worldwide underground movement against the fascists. We worked for whoever made contact with us that we trusted, in Moscow or outside the Soviet Union. Contacts in Moscow usually asked me to do a job, and if I wanted to do it I did it.Page emphasized this last point by stating further, "I was never forced to do anything." She recounts a request while in Moscow for her to take money to China when traveling home, but she declined. The Soviets also asked her to stay in Moscow to help make a movie about America, but "the idea seemed crazy and I refused." During the summer of 1933, the Soviets also had her husband deliver money to Hamburg "for the underground" on his way home to America. (Apparently, the Soviets intended to have them make separate journeys home.) "When I said goodbye to John, I didn't know whether I would ever see him again... We did what we felt we had to do, and that included risking our lives." (The immediate risk Page is referring to was probably the 1933 Nazi takeover of Germany and immediate liquidation of the German Communist Party and its members, specifically the

Reichstag Fire

The Reichstag fire (german: Reichstagsbrand, ) was an arson attack on the Reichstag building, home of the German parliament in Berlin, on Monday 27 February 1933, precisely four weeks after Nazi leader Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of ...

and resulting Reichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree (german: Reichstagsbrandverordnung) is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State (german: Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutz von Volk und Staat) issued by Germ ...

of February 28, 1933.)

Most foreigners joined the Soviet underground via the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

's " International Liaison Department" or "OMS" (Russian-language acronym).

"Disillusionment"

During their second visit 1931–1933, Page claims to have not realized how privileged a life they led, living at the Lux Hotel and buying scarce good easily with ''valudas'' ("American-style paper money") instead ofSoviet rouble

The ruble or rouble (russian: рубль) was the currency of the Soviet Union, introduced in 1922, replacing the Imperial Russian ruble. One ruble was divided into 100 kopecks ( – ''kopeyka'', ''kopeyki''). Soviet banknotes and coins were pr ...

s. Louis Fischer

Louis Fischer (29 February 1896 – 15 January 1970) was an American journalist. Among his works were a contribution to the ex-communist treatise '' The God that Failed'' (1949), '' The Life of Mahatma Gandhi'' (1950), basis for the Academy A ...

discussed the current famine in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, but they dismissed him as a salaried newspaperman. "We didn't know about the horrors of collectivization because we chose not to know. Fischer was right, but we didn't believe him." She had not known about "the matter of the purges because the Soviets were covering up the facts.

During the early 1950s McCarthy Era, she notes "my work as a writer was interrupted." Viking Press

Viking Press (formally Viking Penguin, also listed as Viking Books) is an American publishing company owned by Penguin Random House. It was founded in New York City on March 1, 1925, by Harold K. Guinzburg and George S. Oppenheim and then acquire ...

canceled publication of her novel ''Daughter of Man'', despite the support of editor Pascal Covici

Pascal Avram "Pat" Covici (November 4, 1885–October 14, 1964) was a Romanian Jewish-American book publisher and editor, best known for his close associations with authors such as John Steinbeck, Saul Bellow, and many more noted American literary ...

and book agents Mavis Macintosh and Elizabeth Otis (who also represented John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer and the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature winner "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social ...

among others). Eventually, Citadel Press

Kensington Publishing Corp. is an American, New York-based publishing house founded in 1974 by Walter Zacharius (1923–2011)Grimes, William"Walter Zacharius, Romance Publisher, Dies at 87,"''New York Times'' (MARCH 7, 2011). and Roberta Bender ...

published it under a new title, ''With Sun in Our Blood''.

Page documents her departure from the Party: I left the Party in 1953, having lost faith that it could do the job it was supposed to do. My disillusionment was gradual... Gradually, we just plain lost confidence in the party. Ever since the Amalgamated convention in Chicago in the early twenties... the Party seemed too quarrelsome and sectarian for me.She also added nuance to her decision:

I'm resentful that people think we listened only to Moscow and that when Stalin was exposed by Khruschev we lost our idol and therefore quit the Path. Stalin was not the reason we left. He was part of our disillusionment, but he wan't the reason we got out. Party members were not so attached to the Soviet Union that the Khruschev revelations made them change their whole lives. That wasn't the way we saw the world; we saw the world mainly from the U.S. point of view because that was our experience.(Note that Page dates her departure not to the 1956 "

Secret Speech

"On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" (russian: «О культе личности и его последствиях», «''O kul'te lichnosti i yego posledstviyakh''»), popularly known as the "Secret Speech" (russian: секре ...

" by Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

but to 1953, the height of the McCarthy Era

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origina ...

.)

Naming names

Page never testified before any congressional or other committees during theMcCarthy Era

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origina ...

, though the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

did interview her; they failed to connect "John Barnett" with John Markey, however. Friends of theirs who were subpoenaed to testify include: }. Friends who refused to testify include W. E. B. DuBois (who "died a member of the Communist party")

In her 1996 memoir (by which time most of her generation had died), she names scores of people she had known.

Page recounts only mild bitterness over fallings-out with some friends and does little scandal-mongering (e.g., the affairs of Party leader Earl Browder

Earl Russell Browder (May 20, 1891 – June 27, 1973) was an American politician, communist activist and leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Browder was the General Secretary of the CPUSA during the 1930s and first half of the 1940s.

Duri ...

with Kitty Harris

Kitty Harris (Unknown – 1966) was a Soviet Union, Soviet secret agent and "long-time special courier of the OGPU-NKVD foreign intelligence during the 1930s and 1940s."

Harris was identified only in 2001 when her code name "Ada" or "Aida" was ...

and eventual wife Raissa.)

Personal life and death

In 1924 she met and later married fellow teacher/fellow John Fordyce Markey (July 27, 1898 – May 14, 1991) fromWest Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

coal country. She had two children, daughter Dorothy May Markey Kanfer ("May," born April 21, 1935, wife of Stefan Kanfer) and adopted son John Ross Markey.

By the "late 1920s," she chose the pen name "Myra Page" (after a cousin with the same name) because: I could be freer in what I wrote without a name that would be immediately identified with my parents... Another reason for the pen name was that I couldn't very well teach sociology in a university and write radical journalism and fiction at the same time... I could teach as Dorothy Gary and write as Myra Page. Only later during the McCarthy period did I begin to write again under my real name."Myra Page" may first appear in print in 1926. The transformation continued in the first issue of ''Gathering Storm'', where her name appears as "Dorothy Myra Page." (By the 1930, husband John Markey also adopted a pen name as "John Barnett": "the Party advised him to use a pseudonym so he could resume a regular teaching career.") Page died in 1993.

Legacy

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has archived Page's papers.University of Maine

The University of Maine (UMaine or UMO) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Orono, Maine. It was established in 1865 as the land-grant college of Maine and is the Flagship universities, flagshi ...

English professor Christina Looper Baker (August 18, 1939 – January 13, 2013) wrote a 210-page memoir from interviews and papers called ''In a Generous Spirit: A First-Person Biography of Myra Page'' (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996).

Works

In her posthumously-published 1996 memoir, Page describes her anger at racial discrimination in her childhood, manifested by the treatment she witnessed of her Black friends and expressed in her first published piece, "Colorblind" in ''The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Mi ...

'' magazine, published while she was studying at Columbia (circa 1920) by W. E. B. DuBois, who became her friend.

By the late 1920s, as a radical, pro-worker, communist writer, Page became one of scores of American writers who embraced "Proletkult

Proletkult ( rus, Пролетку́льт, p=prəlʲɪtˈkulʲt), a portmanteau of the Russian words "proletarskaya kultura" (proletarian culture), was an experimental Soviet artistic institution that arose in conjunction with the Russian Revolu ...

" (which, after Stalin came to full power, emerged as "Socialist Realism

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is ch ...

"), advocated in the US by ''New Masses

''New Masses'' (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party USA. It succeeded both ''The Masses'' (1912–1917) and ''The Liberator''. ''New Masses'' was later merged into '' Masses & Mainstream'' (19 ...

'' editor-in-chief Mike Gold

Michael Gold (April 12, 1894 – May 14, 1967) was the pen-name of Jewish American writer Itzok Isaac Granich. A lifelong communist, Gold was a novelist and literary critic. His semi-autobiographical novel '' Jews Without Money'' (1930) was a bes ...

.

Of her works, ''Gathering Storm'' (1932) is significant as both proletariat novel and focal point on the "black-belt thesis," while ''Moscow Yankee'' chronicles an unemployed American autoworker who emigrates to the Soviet Union for work. "I did not see the novel as propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

," she said of it. Instead, she included it among a group of works on Gastonia, particularly by women. She calls Mary Heaton Vorse

Mary Heaton Vorse (October 11, 1874 – June 14, 1966) was an American journalist and novelist. She established her reputation as a journalist reporting the labor protests of a largely female and immigrant workforce in the east-coast textile indus ...

's account ''Gastonia'' (1929) as more reportage than novel. She considers the account of Olive Tilford Dargan (writing under pen name "Fielding Burke"), ''Call Home the Heart'' well written though romanticized. She considers Grace Lumpkin

Grace Lumpkin (March 3, 1891 – March 23, 1980) was an American writer of proletarian literature, focusing most of her works on the Depression era and the rise and fall of favor surrounding communism in the United States. Most important of fou ...

's book '' To Make My Bread'' equal to her own because they both "wrote from the same orientation" as Southern women who had seen poverty.

During the 1940s, Page published no more fiction books; her last novel, ''With the Sun in Our Blood'' (1950) was in fact drafted during the 1930s after transcribing an oral history by Dolly Hawkins, whom Page had known while they both were organizers in Arkansas.

Novels:

* ''Southern Cotton Mills and Labor'', introduced by Bill Dunne (1929)

* ''Gathering Storm: A Story of the Black Belt'' (as "Dorothy Myra Page") (1932)

* ''Soviet Main Street'' with photography by Abram Pogovsky (Soyuzphoto) (1933)

* ''Moscow Yankee'' (1935, 1995)

* ''With Sun in Our Blood'' (1950)

** Reissue: ''Daughter of the Hills: A Woman's Part in the Coal Miners' Struggle'', introduced by Alice Kessler-Harris

Alice Kessler-Harris (June 2, 1941, Leicester) is R. Gordon Hoxie Professor Emerita of American History at Columbia University, and former president of the Organization of American Historians, and specialist in the American labor and comparative ...

and Paul Lauter, afterword by Deborah S. Rosenfelt (1950, 1986)

Short stories, chapters, articles:

* "American Working Women," ''Workers' News'' (Fall 1934)

* "Leave Them Meters Be," ''Workers' News'' (Fall 1934)

* "Water," ''Workers' News'' (Fall 1934)

* "The Girl Who Was Afraid," ''Southern Worker'' (1934)

* "Men in Chains," ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'' (as "Myra Page") (1935)

* "Pickets and Slippery Sticks", chapter in '' New Pioneer Story Book'' (1935)

Juvenile Biographies:

* ''The Little Giant of Schenectady: Charles Steinmetz

Charles Proteus Steinmetz (born Karl August Rudolph Steinmetz, April 9, 1865 – October 26, 1923) was a German-born American mathematician and electrical engineer and professor at Union College. He fostered the development of alternating ...

'' (1956) (as Dorothy Markey)

* ''Explorer of Sound: Michael Pupin'' (1964) (as Dorothy Markey)

Articles, Chapters:

* "Colorblind", ''The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Mi ...

'' magazine (ca. 1920) (as "Dorothy Gary")

* "The Developing Study of Culture" (as "Dorothy P. Gary"), ''Trends in American Sociology'' (1929)

* "Bourgeois Apologists and the South" (reviews), ''The Communist'' (September 1930)

* "Grey-Wash" (review), ''The Communist'' (May 1931)

* "The Cropper Prepares", ''The New Masses'' (February 11, 1936)

* "Malraux on Spain", ''Daily Worker'' (March 7, 1937)

* "Hallie Flanagan," (publication unknown) (circa 1937)

* "Cardenas Speaks for Mexico", ''The New Masses

''New Masses'' (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party USA. It succeeded both ''The Masses'' (1912–1917) and ''The Liberator''. ''New Masses'' was later merged into '' Masses & Mainstream'' (19 ...

'' (August 30, 1938)

* "Cornish Miners (review), ''The New Masses'' (November 18, 1941)

* "Farm Saga" (review) Myra Page, ''The New Masses'' (March 3, 1942)

Autobiography:

* ''In a Generous Spirit: A First-Person Biography of Myra Page'' with Christina Looper Baker (1996)

See also

* Stefan Kanfer *Grace Lumpkin

Grace Lumpkin (March 3, 1891 – March 23, 1980) was an American writer of proletarian literature, focusing most of her works on the Depression era and the rise and fall of favor surrounding communism in the United States. Most important of fou ...

* Esther Shemitz

Esther Shemitz (June 25, 1900August 16, 1986), also known as "Esther Chambers" and "Mrs. Whittaker Chambers," was an American painter and illustrator who, as wife of ex-Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers, provided testimony that "helped substantiate" h ...

* Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938), ...

* Wanda Gag

Wanda is a female given name of Polish origin. It probably derives from the tribal name of the Wends.Campbell, Mike"Meaning, Origin, and History of the Name Wanda."''Behind the Name.'' Accessed on August 12, 2010. The name has long been popular in ...

* Marguerite Young (journalist)

Marguerite Young (1905 – 1995) was an American journalist of the early 20th-century, best known for her Communist Party affiliation, specifically as the Washington bureau chief of the ''Daily Worker'' who facilitated the introduction between S ...

* Proletkult

Proletkult ( rus, Пролетку́льт, p=prəlʲɪtˈkulʲt), a portmanteau of the Russian words "proletarskaya kultura" (proletarian culture), was an experimental Soviet artistic institution that arose in conjunction with the Russian Revolu ...

References

External sources

Wisconsin Historical Society: undated photo of Myra Page

(includes photo)

Those Good Gertrudes

A Social History of Women Teachers in America - Author's Annotated Introduction to Manuscript Collections

Myra Page Papers, 1910-1990

at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill {{DEFAULTSORT:Page, Myra 20th-century American women writers 1897 births Columbia University alumni American feminist writers American communists Marxist feminists American socialist feminists 1993 deaths 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American short story writers American women novelists American women short story writers American women journalists Novelists from Virginia Journalists from Virginia University of Richmond alumni American people of Welsh descent People from Newport News, Virginia 20th-century American journalists