Musurgia Universalis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

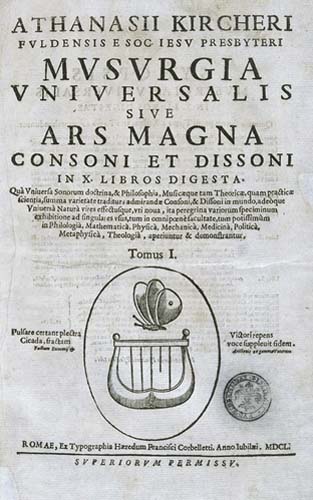

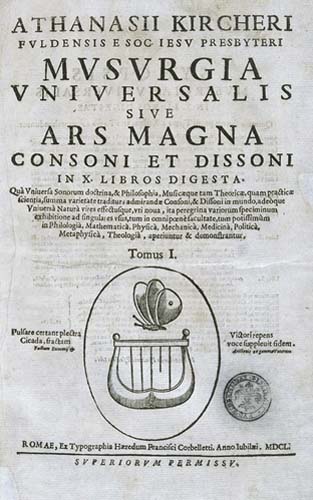

''Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni'' ("The Universal Musical Art, of the Great Art of Consonance and Dissonance") is a 1650 work by the

''Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni'' ("The Universal Musical Art, of the Great Art of Consonance and Dissonance") is a 1650 work by the

Kircher compiled all the musical knowledge available in his day, making this the first encyclopedia of music. Since its publication it has been a valuable source of information to musicologists about baroque concepts of style and composition. It provides the earliest account of the

Kircher compiled all the musical knowledge available in his day, making this the first encyclopedia of music. Since its publication it has been a valuable source of information to musicologists about baroque concepts of style and composition. It provides the earliest account of the

*Book one: on physiology, dealing with the structure of the ear, anatomy of the vocal organs, and the sounds made by animals, birds and insects, including the death-song of the swan

*Book two: on philology, the origin of sound, the music of the Hebrews, and the ancient Greeks

*Book three: on arithmetic, with the theory of

*Book one: on physiology, dealing with the structure of the ear, anatomy of the vocal organs, and the sounds made by animals, birds and insects, including the death-song of the swan

*Book two: on philology, the origin of sound, the music of the Hebrews, and the ancient Greeks

*Book three: on arithmetic, with the theory of

digital copy of volume 2 of ''Musurgia Universalis''

German translation of ''Musurgia Universalis''translation of the section on musical instruments

{{Authority control Musicology 1650 in science 1650 works Obsolete scientific theories Athanasius Kircher

''Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni'' ("The Universal Musical Art, of the Great Art of Consonance and Dissonance") is a 1650 work by the

''Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni'' ("The Universal Musical Art, of the Great Art of Consonance and Dissonance") is a 1650 work by the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

scholar Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans ...

. It was printed in Rome by Ludovico Grignani and dedicated to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria

Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria (5 January 1614 – 20 November 1662), younger brother of Emperor Ferdinand III, was an Austrian soldier, administrator and patron of the arts.

He held a number of military commands, with limited success, an ...

. It was a compendium of ancient and contemporary thinking about music, its production and its effects. It explored, in particular, the relationship between the mathematical properties of music (e.g. harmony and dissonance) with health and rhetoric.

The work complements two of Kircher's other books: '' Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica'' had set out the secret underlying coherence of the universe and ''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae

''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae'' ("The Great Art of Light and Shadow") is a 1646 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Ferdinand IV, King of the Romans and published in Rome by Lodovico Grignani. A second edition was pub ...

'' had explored the ways of knowledge and enlightenment. What ''Musurgia Universalis'' contained, through its exploration of dissonance within harmony, was an explanation of the presence of evil in the world.

Composition and publication

Kircher compiled all the musical knowledge available in his day, making this the first encyclopedia of music. Since its publication it has been a valuable source of information to musicologists about baroque concepts of style and composition. It provides the earliest account of the

Kircher compiled all the musical knowledge available in his day, making this the first encyclopedia of music. Since its publication it has been a valuable source of information to musicologists about baroque concepts of style and composition. It provides the earliest account of the doctrine of the affections

The doctrine of the affections, also known as the ''doctrine of affects'', ''doctrine of the passions'', ''theory of the affects'', or by the German term Affektenlehre (after the German ''Affekt''; plural ''Affekte'') was a theory in the aesthe ...

in music. As well as including a three-part fantasy of his own and a composition by Emperor Ferdinand III

Ferdinand III (Ferdinand Ernest; 13 July 1608, in Graz – 2 April 1657, in Vienna) was from 1621 Archduke of Austria, King of Hungary from 1625, King of Croatia and Bohemia from 1627 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1637 until his death in 1657.

Fe ...

, Kircher reproduced many musical pieces to illustrate the styles he described, thereby preserving pieces by Frescobaldi

The Frescobaldi are a prominent Florentine noble family that have been involved in the political, social, and economic history of Tuscany since the Middle Ages. Originating in the Val di Pesa in the Chianti, they appear holding important posts ...

, Froberger, and others. Kircher had a number of collaborators who assisted his research with their expertise, and by providing him with examples of different types of music. These included Antonio Maria Abbatini

Antonio Maria Abbatini ( or 1610 – or 1679) was an Italian composer, active mainly in Rome.

Abbatini was born in Città di Castello. He served as maestro di cappella at the Basilica of St. John Lateran from 1626 to 1628; at the cathedral in O ...

, Giovanni Girolamo Kapsperger and Giacomo Carissimi

(Gian) Giacomo Carissimi (; baptized 18 April 160512 January 1674) was an Italian composer and music teacher. He is one of the most celebrated masters of the early Baroque or, more accurately, the Roman School of music. Carissimi established the ...

.

''Musurgia Universalis'' was one of Kircher's largest books. The work was published in two volumes with a total of 1,112 pages and many illustrations. It was one of the most influential books on music theory in the seventeenth century, and of the 1,500 copies known to have been published, 266 are still recorded in various collections. Three hundred copies of the first edition were distributed to Jesuit missionaries who gathered in Rome in 1650 for the election of the new Superior General

A superior general or general superior is the leader or head of a religious institute in the Catholic Church and some other Christian denominations. The superior general usually holds supreme executive authority in the religious community, while t ...

and carried back to many different lands. In 1656 a Jesuit mission to China took two dozen copies with it when it departed. A second edition was published in Amsterdam in 1662.

Concepts

The concepts presented in ''Musurgia Universalis'' overlap with Kircher's other works - they include musical cryptography ('' Polygraphia Nova'') andtarantism

Tarantism is a form of hysteric behaviour originating in Southern Italy, popularly believed to result from the bite of the wolf spider '' Lycosa tarantula'' (distinct from the broad class of spiders also called tarantulas).

A better candidate c ...

('' Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica''). There was a detailed discussion of the phenomenon of the echo and its similarity to the reflection of light (''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae

''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae'' ("The Great Art of Light and Shadow") is a 1646 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Ferdinand IV, King of the Romans and published in Rome by Lodovico Grignani. A second edition was pub ...

''). His account of speaking tubes and amplification was developed in his later work ''Historia Eustachio Mariana

''Historia Eustachio Mariana'' is a 1665 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It describes his chance discovery of a ruined shrine of the Virgin Mary at :it:Santuario della Mentorella, Mentorella, the site where tradition held that the ...

'', concerning his installation of trumpets that broadcast a call to prayer at the shrine of Mentorella.

Book eight explained a method for composition and writing harmony that Kircher maintained any person could use, whether they knew anything about music or not. Hew had invented this system while teaching mathematics at Würzburg University

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the ''Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzburg is ...

many years previously. This method had great appeal for Jesuits working as missionaries, who sought to use the power of music to draw converts to the Catholic faith by composing hymns in the languages of the people where they were working. Accompanying this method was a description of the arca musurgia, a kind of calculating machine that allowed users to apply Kircher's rules on composition and actually create music. A number of these machines were built and distributed to distinguished patrons together with the book.

After providing the reader with many explanations of physical phenomena and their explanation, as in many of his other works Kircher used the final book to expound the spiritual dimension of everything he has revealed. In ''Musurgia Universalis'' he likens the creation of the world to the building of a great organ with six registers corresponding to the six days of creation on which God plays, creating harmony. The illustration shows the elaborately-decorated organ with small circular panels illustrating each of the days of creation.

Structure

*Book one: on physiology, dealing with the structure of the ear, anatomy of the vocal organs, and the sounds made by animals, birds and insects, including the death-song of the swan

*Book two: on philology, the origin of sound, the music of the Hebrews, and the ancient Greeks

*Book three: on arithmetic, with the theory of

*Book one: on physiology, dealing with the structure of the ear, anatomy of the vocal organs, and the sounds made by animals, birds and insects, including the death-song of the swan

*Book two: on philology, the origin of sound, the music of the Hebrews, and the ancient Greeks

*Book three: on arithmetic, with the theory of harmonic

A harmonic is a wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the ''fundamental frequency'', the frequency of the original periodic signal, such as a sinusoidal wave. The original signal is also called the ''1st harmonic'', the ...

s, proportion, the ratios of intervals

Interval may refer to:

Mathematics and physics

* Interval (mathematics), a range of numbers

** Partially ordered set#Intervals, its generalization from numbers to arbitrary partially ordered sets

* A statistical level of measurement

* Interval e ...

, the Greek scales, the Scale of Guido d'Arezzo

Guido of Arezzo ( it, Guido d'Arezzo; – after 1033) was an Italian music theorist and pedagogue of High medieval music. A Benedictine monk, he is regarded as the inventor—or by some, developer—of the modern staff notation that had a ma ...

, the system of Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

, and the ancient Greek modes

*Book four: on geometry, discussion of the monochord

A monochord, also known as sonometer (see below), is an ancient musical and scientific laboratory instrument, involving one (mono-) string ( chord). The term ''monochord'' is sometimes used as the class-name for any musical stringed instrument h ...

, and its divisions

*Book five: on organology, based book xii of the Harmonicorum by Marin Mersenne

Marin Mersenne, OM (also known as Marinus Mersennus or ''le Père'' Mersenne; ; 8 September 1588 – 1 September 1648) was a French polymath whose works touched a wide variety of fields. He is perhaps best known today among mathematicians for ...

, containing a dissertation on instrumental music

*Book six: on composition, musical notation

Music notation or musical notation is any system used to visually represent aurally perceived music played with instruments or sung by the human voice through the use of written, printed, or otherwise-produced symbols, including notation fo ...

, counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

, and other branches of composition, containing a canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western ca ...

that can be sung by twelve million two hundred thousand voices

*Book seven: on discernment, covering the difference between ancient and modern music

*Books eight: on wonders, including a mathematical method (‘musarithmica’) that allows the most inexperienced to compose with perfection

*Book nine: on the magic of consonance and dissonance and their effects on the mind and body including tarantism

Tarantism is a form of hysteric behaviour originating in Southern Italy, popularly believed to result from the bite of the wolf spider '' Lycosa tarantula'' (distinct from the broad class of spiders also called tarantulas).

A better candidate c ...

*Book ten: on analogy, discusses the harmony of the spheres

The ''musica universalis'' (literally universal music), also called music of the spheres or harmony of the spheres, is a philosophical concept that regards proportions in the movements of celestial bodies – the Sun, Moon, and planets – as a f ...

, and of the four elements

Classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Tibet, and India had simi ...

, the principles of harmony exemplified in the proportions of the human body and the affections of the mind, together with practical description of the aeolian harp

An Aeolian harp (also wind harp) is a musical instrument that is played by the wind. Named for Aeolus, the ancient Greek god of the wind, the traditional Aeolian harp is essentially a wooden box including a sounding board, with strings stretched ...

, which Kircher claimed to have invented.

Illustrations

An engraved portrait of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm faces the frontispiece of volume one, was designed byJohann Paul Schor

Johann Paul Schor (1615–1674), known in Rome as Giovanni Paolo Tedesco ( ''Tedesco'' literally means ''German'' in Italian), was an Austrian artist. He was the preeminent designer of decorative arts in Baroque Rome, providing drawings for state b ...

and engraved by Paulus Pontius

Paulus Pontius (May 1603 in Antwerp – 16 January 1658 in Antwerp) was a Flemish engraver and painter. He was one of the leading engravers connected with the workshop of Peter Paul Rubens. After Rubens' death, Pontus worked with other leadin ...

, a student of Rubens. It is dated 'Antwerp 1649'.

Each of the work's two volumes had its own frontispiece. For volume one this followed the design common to many of Kircher's works, depicting a threefold universe with the divine at the top, the celestial in the middle and the earthly below. At the top the eye of God overlooks all from within a triangle which bathes choirs of angels in divine light. Two angels hold aloft a banner proclaiming the sanctus

The Sanctus ( la, Sanctus, "Holy") is a hymn in Christian liturgy. It may also be called the ''epinikios hymnos'' ( el, ἐπινίκιος ὕμνος, "Hymn of Victory") when referring to the Greek rendition.

In Western Christianity, the ...

as a 'Canon angelicus 36 vocum... in 9 choros distributus' ('a 36-voice canon of angels, divided into nine choirs'). Beneath this sits Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

on the celestial sphere, holding the lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

that symbolises harmony and pushing away the panpipes

A pan flute (also known as panpipes or syrinx) is a musical instrument based on the principle of the closed tube, consisting of multiple pipes of gradually increasing length (and occasionally girth). Multiple varieties of pan flutes have been ...

associated with his rival Marsyas

In Greek mythology, the satyr Marsyas (; grc-gre, Μαρσύας) is a central figure in two stories involving music: in one, he picked up the double oboe ('' aulos'') that had been abandoned by Athena and played it; in the other, he challenged ...

. Together with the signs of the zodiac, the sphere carries a quotation from the Book of Job

The Book of Job (; hbo, אִיּוֹב, ʾIyyōḇ), or simply Job, is a book found in the Ketuvim ("Writings") section of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh), and is the first of the Poetic Books in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. Scholars ar ...

(38:37): 'Quis concentum coeli dormire faciet?' ('Who shall make the concert of heaven to sleep?'). At the bottom left of the image Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samos, Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionians, Ionian Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher and the eponymou ...

sits, with one arm resting on this theorem

In mathematics, a theorem is a statement that has been proved, or can be proved. The ''proof'' of a theorem is a logical argument that uses the inference rules of a deductive system to establish that the theorem is a logical consequence of th ...

and the other pointing towards a group of smiths, the sound of whose Pythagorean hammers

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

striking metal is said to have first given him the notion of the mathematical basis of harmony. In the centre are a ring of dancers on land, and to their right, a triton

Triton commonly refers to:

* Triton (mythology), a Greek god

* Triton (moon), a satellite of Neptune

Triton may also refer to:

Biology

* Triton cockatoo, a parrot

* Triton (gastropod), a group of sea snails

* ''Triton'', a synonym of ''Triturus' ...

dancing in the water with mermaid

In folklore, a mermaid is an aquatic creature with the head and upper body of a female human and the tail of a fish. Mermaids appear in the folklore of many cultures worldwide, including Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Mermaids are sometimes asso ...

s. On the right there is an illustration of an echo, a topic discussed in the work, with a shepherd reciting a line from Virgil and a listener mishearing only the last part of the final word. The echo rebounds from the side of Mount Helicon

Mount Helicon ( grc, Ἑλικών; ell, Ελικώνας) is a mountain in the region of Thespiai in Boeotia, Greece, celebrated in Greek mythology. With an altitude of , it is located approximately from the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth. ...

, where Pegasus

Pegasus ( grc-gre, Πήγασος, Pḗgasos; la, Pegasus, Pegasos) is one of the best known creatures in Greek mythology. He is a winged divine stallion usually depicted as pure white in color. He was sired by Poseidon, in his role as hor ...

strikes the rock with his hoof, bringing forth the stream of Hippocrene

In Greek mythology, Hippocrene ( grc-gre, Ἵππου κρήνη or Ἱπποκρήνη or Ἱππουκρήνη) was a spring on Mt. Helicon. It was sacred to the Muses and formed when Pegasus struck his hoof into the ground, whence its na ...

that flows down to the figure of Muse surrounded by musical instruments.

The frontispiece for volume two was designed by Pierre Miotte. It depicts Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with Jaso ...

with his lyre and the three-headed guardian of the underworld, Cerberus

In Greek mythology, Cerberus (; grc-gre, Κέρβερος ''Kérberos'' ), often referred to as the hound of Hades, is a multi-headed dog that guards the gates of the Underworld to prevent the dead from leaving. He was the offspring of the mo ...

. The motto around his pedestal reads 'Apollo's right hand holds the lyre of the world, his left fits high to low; thus good things are mingled with ill.'

References

External links

*digital copy of volume 2 of ''Musurgia Universalis''

German translation of ''Musurgia Universalis''

{{Authority control Musicology 1650 in science 1650 works Obsolete scientific theories Athanasius Kircher