Munir Ahmed Khan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Munir Ahmad Khan ( ur, ; 20 May 1926 – 22 April 1999), , was a Pakistani nuclear reactor physicist who is credited, among others, with being the "father of the atomic bomb program" of Pakistan for their leading role in developing their nation's

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s during the successive years after the war with India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

in 1971.

From 1972 to 1991, Khan served as the chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission

Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) (Urdu: ) is a federally funded independent governmental agency, concerned with research and development of nuclear power, promotion of nuclear science, energy conservation and the peaceful usage of nuclea ...

(PAEC) who directed and oversaw the completion of the clandestine bomb program from its earliest efforts to develop the atomic weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

to their ultimate nuclear testings in May 1998. His early career was mostly spent in the International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 195 ...

and he used his position to help establish the International Centre for Theoretical Physics

The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) is an international research institute for physical and mathematical sciences that operates under a tripartite agreement between the Italian Government, United Nations Educatio ...

in Italy and an annual conference on physics in Pakistan. As chair of PAEC, Khan was a proponent of the nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

with India whose efforts were directed towards concentrated production of reactor-grade to weapon-grade

Weapons-grade nuclear material is any fissionable nuclear material that is pure enough to make a nuclear weapon or has properties that make it particularly suitable for nuclear weapons use. Plutonium and uranium in grades normally used in nucle ...

plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exh ...

while remained associated with nation's key national security programs.

After retiring from the Atomic Energy Commission in 1991, Khan provided the public advocacy for nuclear power generation

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced b ...

as a substitute for hydroelectricity consumption in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and briefly tenured as the visiting professor

In academia, a visiting scholar, visiting researcher, visiting fellow, visiting lecturer, or visiting professor is a scholar from an institution who visits a host university to teach, lecture, or perform research on a topic for which the visitor ...

of physics at the Institute of Applied Sciences in Islamabad

Islamabad (; ur, , ) is the capital city of Pakistan. It is the country's ninth-most populous city, with a population of over 1.2 million people, and is federally administered by the Pakistani government as part of the Islamabad Capital ...

. Throughout his life, Khan was subjected to political ''ostracization'' due to his advocacy for averting nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

and was rehabilitated when he was honored with the ''Nishan-i-Imtiaz

The Nishan-e-Imtiaz (; ) is one of the state organized civil decorations of Pakistan.

It is awarded for achievements towards world recognition for Pakistan or outstanding service for the country. However, the award is not limited to citizens o ...

'' (Order of Excellence) by the President of Pakistan

The president of Pakistan ( ur, , translit=s̤adr-i Pākiṣṭān), officially the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is the ceremonial head of state of Pakistan and the commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Armed Forces.

While studying at the Government College University in Lahore in the 1940s, Khan had acquainted with

While studying at the Government College University in Lahore in the 1940s, Khan had acquainted with

In 1972, the earlier efforts were directed to a plutonium boosted fission implosion-type device whose design was codenamed: ''

In 1972, the earlier efforts were directed to a plutonium boosted fission implosion-type device whose design was codenamed: ''

/ref> At that meeting, the word " ''bomb''" was never used but it was understood the need for the development of

In 1975, Khan, in discussion with the Corps of Engineers, had selected the

In 1975, Khan, in discussion with the Corps of Engineers, had selected the

Starting in 1972, Khan bought an estate in Islamabad and passed away following complications from heart surgery, aged 72, on 22 April 1999. He is survived by his wife, Thera, three children and four grandchildren.

When Abdus Salam was ejected from his position in 1974, Khan symbolized of many scientists thinking they could control how other peers would use their research. During the timeline of atomic bomb program, Khan was seen as a symbol of both

Starting in 1972, Khan bought an estate in Islamabad and passed away following complications from heart surgery, aged 72, on 22 April 1999. He is survived by his wife, Thera, three children and four grandchildren.

When Abdus Salam was ejected from his position in 1974, Khan symbolized of many scientists thinking they could control how other peers would use their research. During the timeline of atomic bomb program, Khan was seen as a symbol of both

Biographical sketch

Scientist dr. Munir Ahmad

Who's the father of the atomic bomb- IISS

IN Memoriam: Munir Ahmad Khan, IAEA

The Nuclear Supremo Munir Khan

Mineral Research Laboratories

PAEC official page

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Khan, Munir Ahmad 1926 births 1999 deaths Punjabi people Pashtun people People from Kasur District People from Lahore Government College University, Lahore alumni University of the Punjab alumni 20th-century Pakistani engineers Pakistani electrical engineers University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore faculty Pakistani expatriates in the United States North Carolina State University alumni Pakistani physicists Illinois Institute of Technology alumni Pakistani nuclear engineers International Atomic Energy Agency officials Pakistani expatriates in Austria Chairpersons of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission Pakistani nuclear physicists Weapons scientists and engineers Quantum physicists Theoretical physicists People from Islamabad Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences faculty Founders of Pakistani schools and colleges Fellows of Pakistan Academy of Sciences Recipients of Hilal-i-Imtiaz Recipients of Nishan-e-Imtiaz Members of the Pakistan Philosophical Congress Nuclear weapons scientists and engineers

Youth and early life

Munir Ahmad Khan was born inKasur

Kasur (Urdu and pa, ; also romanized as Qasūr; from pluralized Arabic word ''Qasr'' meaning "palaces" or "forts") is a city to south of Lahore, in the Pakistani province of Punjab. The city serves as the headquarters of Kasur District. Kasu ...

, Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi Language, Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also Romanization, romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the I ...

in the British Indian Empire

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himse ...

on 20 May 1926 into a Pashtun

Pashtuns (, , ; ps, پښتانه, ), also known as Pakhtuns or Pathans, are an Iranian ethnic group who are native to the geographic region of Pashtunistan in the present-day countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan. They were historically r ...

Kakazai

The Kakazai ( ps, کاکازي / ککےزي / ککازي, Urdu, fa, ), also known as Loi, Loe, or Loye Mamund ( ps, لوی ماموند; ur, لو ئے / لوئی مَاموند ), a division of the Mamund clan, are part of the larger Tar ...

family that had long been settled in Punjab. After completing his matriculation

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now ...

in 1942 in Kasur, Khan enrolled at the Government College University in Lahore

Lahore ( ; pnb, ; ur, ) is the second List of cities in Pakistan by population, most populous city in Pakistan after Karachi and 26th List of largest cities, most populous city in the world, with a population of over 13 million. It is th ...

and was a contemporary of Abdus Salam

Mohammad Abdus Salam Salam adopted the forename "Mohammad" in 1974 in response to the anti-Ahmadiyya decrees in Pakistan, similarly he grew his beard. (; ; 29 January 192621 November 1996) was a Punjabis, Punjabi Pakistani theoretical physici ...

— the Nobel Laureate in Physics in 1978

Events January

* January 1 – Air India Flight 855, a Boeing 747 passenger jet, crashes off the coast of Bombay, killing 213.

* January 5 – Bülent Ecevit, of CHP, forms the new government of Turkey (42nd government).

* January 6 ...

. In 1946, Khan graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

(BA) in mathematics and enrolled at the Punjab University to study engineering in 1949.

In 1951, Khan graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Engineering

A Bachelor of Engineering (BEng) or a Bachelor of Science in Engineering (BSE) is an academic undergraduate degree awarded to a student after three to five years of studying engineering at an accredited college or university.

In the UK, a Bach ...

(BSE) in electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

and was noted for his academic standing when he was named to the Roll of Honor for his class of 1951. After graduation, Khan served on an engineering faculty of the University of Engineering and Technology (UET) in Lahore, and earned a Fulbright Scholarship

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people ...

to study engineering in the United States.Haris N. Khan, "Pakistan's Nuclear Development: Setting the Record Straight," Defence Journal, August 2010"Munir Khan Passes Away," Business Recorder, 23 April 1999.

Under the Fulbright Scholarship program, Khan attended North Carolina State University

North Carolina State University (NC State) is a public land-grant research university in Raleigh, North Carolina. Founded in 1887 and part of the University of North Carolina system, it is the largest university in the Carolinas. The univers ...

to resume his graduate studies in electrical engineering and graduated with a Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast t ...

(MS) in electrical engineering in 1953. His master's thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

, titled: ''Investigation on Model Surge Generator'' contained fundamental work on applications of the impulse generator

An impulse generator is an electrical apparatus which produces very short high-voltage or high- current surges. Such devices can be classified into two types: impulse voltage generators and impulse current generators. High impulse voltages are u ...

.

In the United States, Khan gradually lost interest in electrical engineering and took an interest in physics when he started taking graduate courses on topics involving the thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed by the four laws ...

and kinetic theory of gases

Kinetic (Ancient Greek: κίνησις “kinesis”, movement or to move) may refer to:

* Kinetic theory, describing a gas as particles in random motion

* Kinetic energy, the energy of an object that it possesses due to its motion

Art and ent ...

at the Illinois Institute of Technology

Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the merger of the Armour Institute and Lewis Institute in 1940. The university has prog ...

. In 1953, Khan left his graduate studies in physics at the Illinois Institute of Technology when he accepted to be a participant in the Atoms for Peace

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment ...

policy of the United States and started his training program in nuclear engineering

Nuclear engineering is the branch of engineering concerned with the application of breaking down atomic nuclei ( fission) or of combining atomic nuclei ( fusion), or with the application of other sub-atomic processes based on the principles of n ...

offered by the North Carolina State University

North Carolina State University (NC State) is a public land-grant research university in Raleigh, North Carolina. Founded in 1887 and part of the University of North Carolina system, it is the largest university in the Carolinas. The univers ...

in cooperation with the Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a science and engineering research national laboratory operated by UChicago Argonne LLC for the United States Department of Energy. The facility is located in Lemont, Illinois, outside of Chicago, and is the l ...

in Illinois in 1953.20 Years VIC (1979–1999), ECHO, Journal of the IAEA Staff- No. 202, pp. 24–25

In 1957, Khan completed his training at the Argonne National Laboratory, and college classes in nuclear engineering, that allowed him to graduate with an MS degree in nuclear engineering, with strong emphasis on nuclear reactor physics

Nuclear reactor physics is the field of physics that studies and deals with the applied study and engineering applications of chain reaction to induce a controlled rate of fission in a nuclear reactor for the production of energy.van Dam, H., ...

, from North Carolina State University.

Early professional work

After graduating from North Carolina State University (NCSU) in 1953, Khan found employment withAllis-Chalmers

Allis-Chalmers was a U.S. manufacturer of machinery for various industries. Its business lines included agricultural equipment, construction equipment, power generation and power transmission equipment, and machinery for use in industrial s ...

in Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

before joining the Commonwealth Edison

Commonwealth Edison, commonly known by syllabic abbreviation as ComEd, is the largest electric utility in Illinois, and the in Chicago and much of Northern Illinois. Its service territory stretches roughly from Iroquois County on the south ...

company in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

. At both engineering firms, Khan worked on power generation equipment such as generators and mechanical pumps and participated in a federal contract awarded to Commonwealth Edison to design and construct the Experimental Breeder Reactor I

Experimental Breeder Reactor I (EBR-I) is a decommissioned research reactor and U.S. National Historic Landmark located in the desert about southeast of Arco, Idaho. It was the world's first breeder reactor. At 1:50 p.m. on December 20, ...

(EBR-I) which built up his interests in practical applications of physics that led him to attend the Illinois Institute of Technology, and to attend the training program in nuclear engineering offered by NCSU.

In 1957, Khan served as a Resident Research Associate in the Nuclear Engineering Division at the Argonne National Laboratory where he was trained as a nuclear reactor physicist and worked on design modifications of the Chicago Pile-5

Chicago Pile-5 (CP-5) was the last of the line of Chicago Pile research reactors which started with CP-1 in 1942. The first reactor built on the Argonne National Laboratory campus in DuPage county, it operated from 1954-1979.American Machine and Foundry

American Machine and Foundry (known after 1970 as AMF, Inc.) was one of the United States' largest recreational equipment companies, with diversified products as disparate as garden equipment, atomic reactors, and yachts.

The company was founde ...

as a consultant until 1958.

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

In 1958, Khan left the United States after accepting employment with theInternational Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 195 ...

(IAEA) in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, joining the nuclear power division at a senior technical position, and was noted as the first Asian person from any developing country

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreeme ...

to be appointed to a senior position there. During this time, Khan was taken as an advisor on energy issues by the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission

Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) (Urdu: ) is a federally funded independent governmental agency, concerned with research and development of nuclear power, promotion of nuclear science, energy conservation and the peaceful usage of nuclea ...

(PAEC) and represented his country at various energy-based conferences and seminars for nuclear power generation. At IAEA, Khan's work was mostly based on reactor technology and he worked on the application of nuclear reactor physics to the utilization factor

The utilization factor or use factor is the ratio of the time that a piece of equipment is in use to the total time that it could be in use. It is often averaged over time in the definition such that the ratio becomes the amount of energy used d ...

of nuclear reactors, overseeing technical aspects of the nuclear reactors as well as conducting a geological survey for the construction of commercial nuclear power plants.

His work on nuclear reactor physics, specifically determining neutron transport

Neutron transport (also known as neutronics) is the study of the motions and interactions of neutrons with materials. Nuclear scientists and engineers often need to know where neutrons are in an apparatus, what direction they are going, and how qu ...

and the interaction of neutrons

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons behave ...

within the reactor, was widely recognized and he was often known as "''Reactor Khan''" among his peers at the nuclear power division of the IAEA. Khan was also known to have gained expertise in producing isotopic reactor-grade plutonium Reactor-grade plutonium (RGPu) is the isotopic grade of plutonium that is found in spent nuclear fuel after the uranium-235 primary fuel that a nuclear power reactor uses has burnt up. The uranium-238 from which most of the plutonium isotopes der ...

, deriving it from neutron capture

Neutron capture is a nuclear reaction in which an atomic nucleus and one or more neutrons collide and merge to form a heavier nucleus. Since neutrons have no electric charge, they can enter a nucleus more easily than positively charged protons ...

, that is frequently found alongside the uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

(U235) civilian reactors, in the form of low enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (2 ...

.

At IAEA, Khan organized more than 20 international technical and scientific conferences and seminars on the topics of constructing deuterium-based ( heavy water) reactors, gas-cooled reactor

A gas-cooled reactor (GCR) is a nuclear reactor that uses graphite as a neutron moderator and a gas (carbon dioxide or helium in extant designs) as coolant. Although there are many other types of reactor cooled by gas, the terms ''GCR'' and to a ...

systems, efficiency and performance of nuclear power plants, the fuel extraction of uranium, and production of plutonium. In 1961, he prepared a technical feasibility report on behalf of the IAEA on small nuclear power reactor projects of the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President ...

.

In 1964 and 1971, Khan served as scientific secretary to the third and fourth United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

International Geneva Conferences on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. Between 1986 and 1987, Khan also served as Chairman of the IAEA Board of Governors and headed Pakistan's delegations to IAEA General Conferences from 1972 to 1990. He served as a Member of the IAEA Board of Governors for 12 years.

International Centre for Theoretical Physics

While studying at the Government College University in Lahore in the 1940s, Khan had acquainted with

While studying at the Government College University in Lahore in the 1940s, Khan had acquainted with Abdus Salam

Mohammad Abdus Salam Salam adopted the forename "Mohammad" in 1974 in response to the anti-Ahmadiyya decrees in Pakistan, similarly he grew his beard. (; ; 29 January 192621 November 1996) was a Punjabis, Punjabi Pakistani theoretical physici ...

and was supportive of Salam's efforts for his vision to put his country engaged towards scientific education and literacy as an adviser in the Ayub administration in the 1960s. While working at IAEA, Khan recognized the importance of Theoretical physics

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experim ...

but was more interested in studying its "real world" applications that related to the field of physics of nuclear reaction in a confined nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

.

In September 1960, Salam confided Khan about establishing a research institute dedicated towards advancement of mathematical sciences

The mathematical sciences are a group of areas of study that includes, in addition to mathematics, those academic disciplines that are primarily mathematical in nature but may not be universally considered subfields of mathematics proper.

Statist ...

under IAEA which Khan immediately supported the idea by lobbying at IAEA for financial funding and sponsorship– thus founding of the International Center for Theoretical Physics

The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) is an international research institute for physical and mathematical sciences that operates under a tripartite agreement between the Italian Government, United Nations Education ...

(ICTP). The idea mostly met with favorable views from the member countries of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

's scientific committee

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

though one of its influential member— Isidor Rabi from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

— opposed the idea of establishment of ICTP. It was Khan who convinced Sigvard Eklund, Director of the International Atomic Energy Agency, to intervene in this matter that ultimately led to the establishment of the International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into pr ...

in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. The IAEA eventually entrusted Khan to oversee the construction of the ICTP in 1967, and played an instrumental role in establishing the annual summer conference on science in 1976 on Salam's advice.

Even after his retirement from the PAEC, Khan remained concern with the physics education

Physics education refers to the methods currently used to teach physics. Physics Education Research refers to an area of pedagogical research that seeks to improve those methods. Historically, physics has been taught at the high school and colle ...

in his country, joining the faculty of the Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences to instruct courses on physics in 1997— the university that he oversaw its academic programs in 1976 as Center for Nuclear Studies. In 1999, Khan was invited as a guest speaker at the opening ceremony of the National Center for Physics

The Abdus Salam Centre for Physics , () Previously known as Riazuddin Centre for Physics. is a federally-funded research institute and national laboratory site managed by the Quaid-i-Azam University for the Ministry of Energy (MoE) of the Gover ...

— the national laboratory site— that works in close proximity with the ICTP in Italy. In 1967, Khan and Salam had prepared a proposal for setting up a fuel cycle facility and plutonium reprocessing plant to address the energy consumption demand— the proposal was deferred by Ayub administration on economic grounds.

Zulifikar Ali Bhutto's trusted aide

After his visit to theBhabha Atomic Research Centre

The Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) is India's premier nuclear research facility, headquartered in Trombay, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. It was founded by Homi Jehangir Bhabha as the Atomic Energy Establishment, Trombay (AEET) in January 1 ...

in Trombay

Trombay is an eastern suburb in Bombay (Mumbai), India.

History

Trombay was called Neat's Tongue because of its shape. Once, it was an island nearly 5 km East of Mumbai and was about 8 km in length and 8 km in width. The island ...

as part of the IAEA inspection in 1964 and the second war with India in 1965, Khan became increasingly concerned about politics and international affairs. Eventually, Khan voiced his concerns to the Government of Pakistan

The Government of Pakistan ( ur, , translit=hakúmat-e pákistán) abbreviated as GoP, is a federal government established by the Constitution of Pakistan as a constituted governing authority of the four provinces, two autonomous territorie ...

when he met with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Zulfikar (or Zulfiqar) Ali Bhutto ( ur, , sd, ذوالفقار علي ڀٽو; 5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979), also known as Quaid-e-Awam ("the People's Leader"), was a Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the fourt ...

(Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

in Ayub administration at that time) in Vienna about the possible acquisition of nuclear deterrent to address the nuclear threat from India.

On 11 December 1965, Bhutto arranged a meeting between Khan and President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Ayub Khan

Ayub Khan is a compound masculine name; Ayub is the Arabic version of the name of the Biblical figure Job, while Khan or Khaan is taken from the title used first by the Mongol rulers and then, in particular, their Islamic and Persian-influenced s ...

at the Dorchester Hotel

The Dorchester is a five-star luxury hotel on Park Lane and Deanery Street in London, to the east of Hyde Park. It is one of the world's most prestigious and expensive hotels. The Dorchester opened on 18 April 1931, and it still retains its ...

in London where Khan made unsuccessful attempt in try convincing the President to pursue nuclear deterrent despite pointing out cheap cost estimates for the acquiring the nuclear capability. At the meeting, President Ayub Khan downplayed the warnings and swiftly dismissed the offer while believing that Pakistan "was too poor to spend" so much money and ended the meeting saying that, if needed, Pakistan would "somehow buy it off the shelf". After the meeting, Khan met with Bhutto and informed him about meeting with Bhutto later quoting: "''Don't worry. Our turn will come''".

Throughout the 1970s and onwards, Khan was very sympathetic to Pakistan Peoples Party's political cause and President Bhutto had spoken highly of his services while promising to ensure federal funding of the national programs of nuclear weapons at the inauguration ceremony of Karachi Nuclear Power Plant

The Karachi Nuclear Power Plant (or KANUPP) is a large commercial nuclear power plant located at the Paradise Point in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan.

Officially known as Karachi Nuclear Power Complex, the power generation site is composed of three ...

– the first milestone towards the goal of making Pakistan a nuclear power on 28 November 1972.In 1978, Khan told them that the design process of the bomb was completed and Bhutto expected the nuclear test in August 1978. Khan then told Murtaza and Benazir that the tests were moved to December 1978, but delayed indefinitely due to political and diplomatic considerations of the country. Benazir Bhutto, however, continued her ties with Khan and awarded him the Hilal-i-Imtiaz in 1989 for his services to Pakistan's nuclear program in developing nuclear fuel cycle technology.S.K. Pasha, "Solar Energy and the Guests at KANUPP Opening", Morning News (Karachi), 29 November 1972. His left-wing association with the Peoples Party continue even after turnover of federal government by the Pakistani military

The Pakistan Armed Forces (; ) are the military forces of Pakistan. It is the world's sixth-largest military measured by active military personnel and consist of three formally uniformed services—the Army, Navy, and the Air Force, which are ...

in 1977 as Khan visited Bhutto various times in Adiala State Prison to inform him about the status of the program.

Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC)

In 1972, Khan officially resigned from his directorship of the IAEA's reactor division when he was appointed as chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission, replacingI. H. Usmani

Ishrat Hussain Usmani () (15 April 1917 – 17 June 1992) , best known as I. H. Usmani, was a Pakistani atomic physicist, and later a public official who chaired the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) from 1960 to 1971 as well as ...

who was appointed secretary at the Ministry of Science A Science Ministry or Department of Science is a ministry or other government agency charged with science. The ministry is often headed by a Minister for Science.

List of Ministries of Science

Many countries have a Ministry of Science or Ministry ...

in the Bhutto administration. By March 1972, Khan submitted a detailed roadmap to the Ministry of Energy A Ministry of Energy or Department of Energy is a government department in some countries that typically oversees the production of fuel and electricity; in the United States, however, it manages nuclear weapons development and conducts energy-relat ...

(MoE) that envisioned linking the country's entire energy infrastructure

Energy development is the field of activities focused on obtaining sources of energy from natural resources. These activities include production of renewable, nuclear, and fossil fuel derived sources of energy, and for the recovery and reuse ...

to nuclear power sources as a substitute for energy consumption dependent on hydroelectricity. Mahmood, S. Bashiruddin, ''Speeches delivered on Munir Ahmad Khan Memorial Reference'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology in Islamabad, 28 April 2007.

On 28 November 1972, Khan, together with Salam, accompanied President Bhutto to the inauguration ceremony for the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant

The Karachi Nuclear Power Plant (or KANUPP) is a large commercial nuclear power plant located at the Paradise Point in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan.

Officially known as Karachi Nuclear Power Complex, the power generation site is composed of three ...

(KANUPP)–the first milestone towards the goal of making Pakistan a nuclear power. Khan played a crucial role in keeping grid operations running for the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant after its chief scientist, Wazed Miah, had his security clearance

A security clearance is a status granted to individuals allowing them access to classified information (state or organizational secrets) or to restricted areas, after completion of a thorough background check. The term "security clearance" is ...

revoked, and was forced to migrate to Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mo ...

. Khan then established a training facility in cooperation with the Karachi University

The University of Karachi ( sd, ; informally Karachi University, KU, or UoK) is a public research university located in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan. Established in June 1951 by an act of Parliament and as a successor to the University of Sindh ...

to fill the void created by Bengali

Bengali or Bengalee, or Bengalese may refer to:

*something of, from, or related to Bengal, a large region in South Asia

* Bengalis, an ethnic and linguistic group of the region

* Bengali language, the language they speak

** Bengali alphabet, the w ...

engineers. When Canadian General Electric

GE Canada (or General Electric Canada) is the wholly-owned Canadian unit of General Electric, manufacturing various consumer and industrial electrical products all over Canada.

GE Canada was preceded by the company Canadian General Electric (CG ...

stopped the supply of uranium and machine components for the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant in 1976, Khan worked on developing the nuclear fuel cycle

The nuclear fuel cycle, also called nuclear fuel chain, is the progression of nuclear fuel through a series of differing stages. It consists of steps in the ''front end'', which are the preparation of the fuel, steps in the ''service period'' in w ...

without foreign assistance to make sure that the plant kept generating power for the nation's electricity grid by establishing the fuel cycle facility near the power plant in cooperation with the Karachi University.

In 1975–76, Khan entered into diplomacy with France's Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) for acquiring a reprocessing plant for production of reactor-grade plutonium, and a commercial nuclear power plant in Chashma, advising the federal government on key matters regarding the operations of these plants. Negotiations with France over the reprocessing plant was extremely controversial at home with the United States later intervening in the matter between Pakistan and France over fears of nuclear proliferation. Khan's relations with the Bhutto administration often soured because Khan wanted to engage the CEA long enough until PAEC was able to learn to design and construct the plants itself, while Bhutto administration officials wanted the plants based solely on imports from France. In 1973–77, Khan entered in negotiation with CEA for Chashma Nuclear Power Plant

The Chashma Nuclear Power Plant (or CHASNUPP), is a large commercial nuclear power plant located in the vicinities of Chashma colony and Kundian in Punjab in Pakistan.

Officially known as Chashma Nuclear Power Complex, the nuclear power plan ...

, having advised the MoE to sign the IAEA safeguard agreement with France to ensure the foreign funding of the plant, which the PAEC was designing but the CEA left the project with PAEC taking control of the entire project despite Khan's urging to French CEA to fulfill its contractual obligations. With France's offing, Khan eventually negotiated with China over this project's foreign funding in 1985–86.

In 1977, Khan fiercely opposed the French CEA's proposal to alter the design of the reprocessing plant so that it would produce a mixed reactor-grade plutonium with natural uranium

Natural uranium (NU or Unat) refers to uranium with the same isotopic ratio as found in nature. It contains 0.711% uranium-235, 99.284% uranium-238, and a trace of uranium-234 by weight (0.0055%). Approximately 2.2% of its radioactivity comes ...

, which would stop the production of military-grade plutonium. Khan advised the federal government to refuse the modification plan as the PAEC had already build the plant itself and manufactured components from local industry— this plant was built by PAEC and is now known as Khushab Nuclear Complex

Khushab Nuclear Complex is a plutonium production nuclear reactor and heavy water complex situated 30 km south of the town of Jauharabad in Khushab District, Punjab, Pakistan.

The heavy water and natural uranium reactors at Khushab are a ...

.

In 1982, Khan expanded the scope of nuclear technology for harnessing the agriculture and food irradiation process by establishing the Nuclear Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIAB) in Peshawar while moving PAEC's scope towards medical physics

Medical physics deals with the application of the concepts and methods of physics to the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of human diseases with a specific goal of improving human health and well-being. Since 2008, medical physics has been incl ...

research by securing federal funding for various cancer research hospitals in Pakistan in 1983–91.

1971 war and atomic bomb project

On 16 December 1971, Pakistan ultimately called for a unilateral ceasefire to end their third war with India when the Yahya Khan administration acceded to theunconditional surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

In modern times, unconditional surrenders most ofte ...

of the Pakistani military on the eastern front of the war, resulting in the secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

of East Pakistan as the independent country Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mo ...

, from the Federation of Pakistan.

Upon learning the news, Khan returned to Pakistan from Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, landing in Quetta

Quetta (; ur, ; ; ps, کوټه) is the tenth most populous city in Pakistan with a population of over 1.1 million. It is situated in south-west of the country close to the International border with Afghanistan. It is the capital of th ...

to initially attend the winter session to meet with PAEC's scientists before being flown to Multan

Multan (; ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan, on the bank of the Chenab River. Multan is Pakistan's seventh largest city as per the 2017 census, and the major cultural, religious and economic centre of southern Punjab.

Multan is one of the ol ...

. This winter session, known as the ''"Multan meeting"'', was arranged by Abdus Salam for scientists to meet with President Bhutto who, on 20 January 1972, authorized the crash program to develop an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

for the sake of "national survival". President Bhutto invited Khan to take over the weapons program work—a task that Khan threw himself into with full vigor. In spite of having been unknown to many senior scientists, Khan busied himself on development of the program, initially assisting in complicated fast neutron calculations. Although Khan was not a doctorate holder, his extensive experience as a nuclear engineer at the reactor physics division at IAEA enabled him to direct senior scientists working under him on classified projects. Mehmud, Salim, ''Remembering Unsung Heroes: Munir Ahmed Khan'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, 28 April 2007 In a short time, Khan impressed the conservatively-aligned Pakistani military

The Pakistan Armed Forces (; ) are the military forces of Pakistan. It is the world's sixth-largest military measured by active military personnel and consist of three formally uniformed services—the Army, Navy, and the Air Force, which are ...

with the breadth of his knowledge, and grasp of engineering, ordnance

Ordnance may refer to:

Military and defense

* Materiel in military logistics, including weapons, ammunition, vehicles, and maintenance tools and equipment.

**The military branch responsible for supplying and developing these items, e.g., the Uni ...

, metallurgy, chemistry, and interdisciplinary projects that would distinguish from the field of physics.

In December 1972, Abdus Salam directed two theoretical physicists

The following is a partial list of notable theoretical physicists. Arranged by century of birth, then century of death, then year of birth, then year of death, then alphabetically by surname. For explanation of symbols, see Notes at end of this ar ...

, Riazuddin and Masud Ahmad, at the International Center for Theoretical Physics to report to Khan on their return to Pakistan where they formed the "Theoretical Physics Group" (TPG) in PAEC— this division eventually went to commit itself to perform tedious mathematical calculations on fast neutron temperatures. Salam, who saw this program as an opportunity to ensure federal government's interest and funding to promote scientific activities in his country, took over the TPG's directorship with Khan assisting in the solutions

Solution may refer to:

* Solution (chemistry), a mixture where one substance is dissolved in another

* Solution (equation), in mathematics

** Numerical solution, in numerical analysis, approximate solutions within specified error bounds

* Soluti ...

for fast neutron calculations and binding energy measurements of the atomic bomb.

The research operational scope of the Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology

The Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science & Technology (PINSTECH) ( ur, ) is a federally funded multiprogram science and technology research institute managed for the Ministry of Energy by the Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sci ...

, the national laboratory site, was well expanded from a school building to several buildings, which were erected in great haste, in Nilore.Rehman, Inam-ur, ''Remembering Unsung Heroes: Munir Ahmed Khan'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, 28 April 2007 At this laboratory site, Khan assembled a large group of the top physicists of the time from the Quaid-e-Azam University

Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad ( ur, ; commonly referred to as QAU), founded as University of Islamabad, is a ranked 1 public research university in Islamabad, Pakistan.

Founded as the University of Islamabad in 1967, it was initially dedi ...

, where he invited them to conduct classified research with federal funding rather than teaching the fields of physics in the university classrooms.

Kirana-I

The Kirana Hills is a small and extensive rocky mountain range located in Rabwah and Sargodha, Pakistan. It is also a place of tourist attraction in Sargodha City. Locally known as "Black Mountains" due to its brownish landscape, its highest pe ...

''. In March 1974, Khan, together with Salam, held a meeting at the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology with Hafeez Qureshi, a mechanical engineer with an expertise in radiation heat transfer, and Dr. Zaman Shaikh, a chemical engineer from the Defense Science and Technology Organization (DESTO).Alt URL/ref> At that meeting, the word " ''bomb''" was never used but it was understood the need for the development of

explosive lens

An explosive lens—as used, for example, in nuclear weapons—is a highly specialized shaped charge. In general, it is a device composed of several explosive charges. These charges are arranged and formed with the intent to control the shape ...

es, a sub-critical sphere of fissile material could be squeezed into a smaller and denser form, and the reflective tamper, the metal needed to scatter

Scatter may refer to:

* Scattering, in physics, the study of collisions

* Statistical dispersion or scatter

* Scatter (modeling), a substance used in the building of dioramas and model railways

* Scatter, in computer programming, a parameter in ...

only very short distances, so the critical mass would be assembled in much less time. This project required manufacturing and machining of key parts that necessitated another laboratory site, leading Khan, assisted by Salam, to meet with Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Qamar Ali Mirza, Engineer-in-Chief of the Corps of Engineers. Ensuring the Corps would handle its part in the atomic bomb project, Khan requested the construction of the Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

near the Pakistan Ordnance Factories

, type = State-owned company

, industry = Firearms, Defense, Machinery

, fate =

, successor =

, founded =

, founder =

, defunct =

, hq_location_city = Wah Cantonment, Punjab

, hq_location_country = Pakistan

, area_served = world ...

in Wah

Wah Cantonment ( pa, ; ur, ) (often abbreviated to Wah Cantt) is a military cantonment located in Wah in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It is a part of Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District. It is the 24th largest city of Pakistan by popu ...

. Eventually, the project was relocated to the Metallurgical Laboratory with Qureshi and Zaman moving their staff and machine shops from the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology with assistance from the military.

In March 1974, Khan took over the work of TPG from Salam when Salam left the country in protest over a constitutional amendment

A constitutional amendment is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly altering the text. Conversely, ...

, with Riazuddin leading the studies. During this time, Khan launched a uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

program which was seen as a backup for fissile material production, delegating this project to Bashiruddin Mahmood who focused on gaseous diffusion and Shaukat Hameed Khan, who pioneered the laser isotope separation method. The uranium enrichment project accelerated when India announced "Smiling Buddha

Operation Smiling BuddhaThis test has many code names. Civilian scientists called it "Operation Smiling Buddha" and the Indian Army referred to it as ''Operation Happy Krishna''. According to United States Military Intelligence, ''Operation H ...

", a surprise weapons test, with Khan confirming the test's radiation emission through data provided by I. H. Qureshi on 18 May 1974. Sensing the importance of this test, Khan called a meeting between Hameed Khan and Mahmood who analyzed different methods but finally agreed on gaseous diffusion over laser isotope separation, that continued at its own pace under Hameed Khan in October 1974. In 1975, Khalil Qureshi, a physical chemist

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mech ...

, was asked to joined the uranium project under Mehmood who did most of the calculations on military-grade uranium. In 1976, Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan

Abdul Qadeer Khan, (; ur, ; 1 April 1936 – 10 October 2021), known as A. Q. Khan, was a Pakistani nuclear physicist and metallurgical engineer. He was a key figure in Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program and is colloquially known as the ...

, a metallurgist, joined the program but was ejected due to technical difficulties, and peer problems, that led to the program being moved to the Khan Research Laboratories

The Dr. A. Q. Khan Research Laboratories, ( ur, ) or KRL for short, is a federally funded, multi-program national research institute and national laboratory site primarily dedicated to uranium enrichment, supercomputing and fluid mechanics. It ...

in Kahuta

Kahuta (Punjabi, Urdu: کہوٹہ) is a census-designated city and tehsil in the Rawalpindi District of Punjab Province, Pakistan. The population of the Kahuta Tehsil is approximately 220,576 at the 2017 census. Kahuta is the home to the Kahuta ...

with A. Q. Khan being its chief scientist under the Corps of Engineers.

By 1976–77, the entire atomic bomb program was quickly transferred from the civilian Ministry of Science A Science Ministry or Department of Science is a ministry or other government agency charged with science. The ministry is often headed by a Minister for Science.

List of Ministries of Science

Many countries have a Ministry of Science or Ministry ...

, to military control with Khan, as chief scientist, remaining the technical director of the overall bomb program.

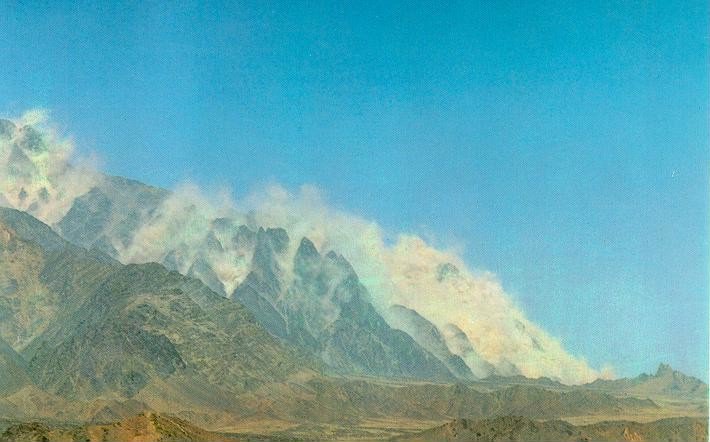

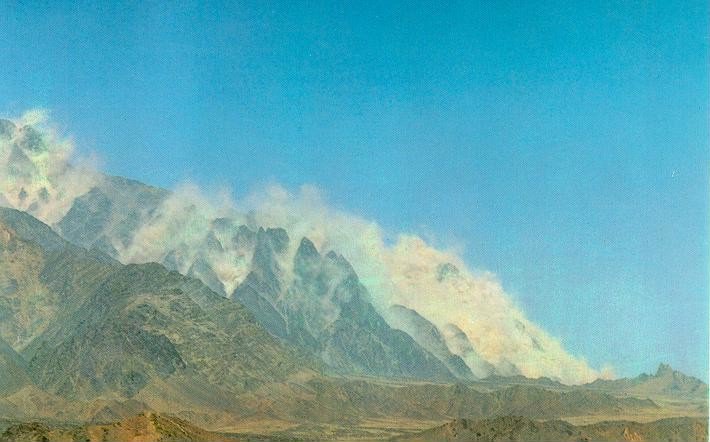

Nuclear tests: Chagai-II

In 1975, Khan, in discussion with the Corps of Engineers, had selected the

In 1975, Khan, in discussion with the Corps of Engineers, had selected the mountain ranges

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have arise ...

in Balochistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. ...

for the isolation needed to maintain security and secrecy. He tasked Ishfaq Ahmad

Ishfaq Ahmad Khan (3 November 1930 – 18 January 2018) , was a Pakistani nuclear physicist, emeritus professor of high-energy physics at the National Centre for Physics, and former science advisor to the Government of Pakistan.

A versatile ...

and Ahsan Mubarak, a seismologist

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

, to conduct a geological survey

A geological survey is the systematic investigation of the geology beneath a given piece of ground for the purpose of creating a geological map or model. Geological surveying employs techniques from the traditional walk-over survey, studying o ...

of mountain ranges with help from the Corps of Engineers and Geological Survey of Pakistan

Geological Survey of Pakistan (GSP) is an independent executive scientific agency to explore the natural resources of Pakistan. Main tasks GSP perform are Geological, Geophysical and Geo-chemical Mapping of Pakistan. Target of these mapping are r ...

. Scouting for a test site in 1976, the team searched for a high altitude and rocky granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

mountain that would be suitable to take more than ~40 kn of nuclear blast yield, ultimately candidating the remote, isolated, and unpopulated ranges at Chagai, Kala-Chitta

Kala Chitta Range (in Punjabi and ur, ''Kālā Chiṭṭā'') is a mountain range in the Attock District of Punjab, Pakistan. Kala- Chitta are Punjabi words meaning Kala the Black and Chitta means the white. The range thrusts eastward acro ...

, Kharan, and Kirana in 1977–78.

The joint work of the various groups at the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology led to the first cold-test of their atomic bomb design on 11 March 1983, codenamed: ''Kirana-I

The Kirana Hills is a small and extensive rocky mountain range located in Rabwah and Sargodha, Pakistan. It is also a place of tourist attraction in Sargodha City. Locally known as "Black Mountains" due to its brownish landscape, its highest pe ...

''. A "''cold test''" is a subcritical test of a nuclear weapon design without the fissile material

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be t ...

inserted to prevent any nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

."Pakistan Became a Nuclear State in 1983-Dr. Samar", The Nation,(Islamabad) 2 May 2003 Retrieved 6 August 2009. Preparations for the tests and engineering calculations were validated by Khan with Ahmad leading the team of scientists; other invitees to witness the test included Ghulam Ishaq Khan

Ghulam Ishaq Khan ( ur, غلام اسحاق خان; 20 January 1915 – 27 October 2006), was a Pakistani bureaucrat who served as the seventh president of Pakistan, elected in 1988 following Zia's death until his resignation in 1993. He wa ...

, Major-General Michael O'Brian

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name "Michael"

* Michael (archangel), ''first'' of God's archangels in the Jewish, Christian an ...

from the Pakistan Air Force

, "Be it deserts or seas; all lie under our wings" (traditional)

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = ...

(PAF), General K. M. Arif, Chief of Army Staff at that time, and other senior military officers.

Khan recalled to his biographer, decades later, that while witnessing the test:

Despite many difficulties and political opposition, Khan lobbied and emphasized the importance of plutonium and countered scientific opposition led by fellow scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan

Abdul Qadeer Khan, (; ur, ; 1 April 1936 – 10 October 2021), known as A. Q. Khan, was a Pakistani nuclear physicist and metallurgical engineer. He was a key figure in Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program and is colloquially known as the ...

, who opposed the plutonium route, favoring the uranium atomic bomb. From the start, studies were concentrated towards feasibility of the plutonium " implosion-type" design, a device known as the Chagai-II

Chagai-II is the codename assigned to the second atomic test conducted by Pakistan, carried out on 30 May 1998 in the Kharan Desert in Balochistan Province of Pakistan. ''Chagai-II'' took place two days after Pakistan's first successful test, ...

in 1998. Khan, together with Abdul Qadeer, worked on his proposal for viability of " gun-type" designs— a simpler mechanism that only had to work with U235, but there was a possibility for that weapon's chain reaction to be a " nuclear fizzle", therefore they abandoned gun-type studies in favor of the implosion-type. Khan's advocacy for the plutonium implosion-type design was validated with the test of a plutonium device that was called ''Chagai-II

Chagai-II is the codename assigned to the second atomic test conducted by Pakistan, carried out on 30 May 1998 in the Kharan Desert in Balochistan Province of Pakistan. ''Chagai-II'' took place two days after Pakistan's first successful test, ...

'' to artificially produce nuclear fission— this nuclear device had the largest yield of all the boosted fission uranium devices.

President Zia, despite Khan's political orientation, widely respected Khan for his knowledge and understanding of national security issues when he spoke highly of him during a visit to the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology in November 1986:

Arms race and diplomacy with India

Despite the issuance of public statements by Pakistani politicians, the atomic bomb program was, nonetheless, kepttop secret

Classified information is material that a government body deems to be sensitive information that must be protected. Access is restricted by law or regulation to particular groups of people with the necessary security clearance and need to kn ...

from their public and Khan became a national spokesman for science in the federal government with a new type of technocratic role. He lobbied for independence of the Space Research Commission from the PAEC and provided narrative for launching the nation's first satellite to meet and compete with India in the space race in Asia. Unlike his predecessor, Khan advocated for an arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

with India to ensure the balance of power by securing funding for military "black" projects and national security programs. By 1979, Khan removed PAEC's role in defense production moving the Wah Group, that designed the tactical nuclear weapons

A tactical nuclear weapon (TNW) or non-strategic nuclear weapon (NSNW) is a nuclear weapon that is designed to be used on a battlefield in military situations, mostly with friendly forces in proximity and perhaps even on contested friendly territo ...

in 1986, from Metallurgical Laboratories to DESTO Desto Records was an American record label. It was founded in 1951 by Horace Grenell who had a mail order business of selling children's records and was looking to expand genres.

The first issue was a three disc edition of '' The Beggars Opera''. I ...

(the independent agency that works with the military), and founded the National Defence Complex

National Defence Complex (NDC), ( ur, ) also known as National Development Complex, National Development Centre, is a Pakistani state-owned defence and aerospace contractor which is a division under the National Engineering and Scientific Co ...

(NDC) in 1991, a rocket propulsion contractor.

At various international conferences, Khan was very critical of the Indian nuclear program as he perceived that it had military purposes, and viewed it as a threat to the region's stability, while he defended Pakistan's non-nuclear weapon policy as well as their nuclear tests when he summed up his thoughts:

When Israel's Operation Opera

Operation Opera ( he, מבצע אופרה), also known as Operation Babylon, was a surprise airstrike conducted by the Israeli Air Force on 7 June 1981, which destroyed an unfinished Iraqi nuclear reactor located southeast of Baghdad, Iraq ...

surprise airstrike destroyed the Osirak Nuclear Plant in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

in 1981, the Pakistani intelligence community learned of the Indian plans to attack Pakistan's national laboratory sites. Khan was confided in by diplomat Abdul Sattar over this intelligence report in 1983. Sattar, A., ''Munir Ahmad Khan Memorial Reference'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, 28 April 2007 While attending a conference on nuclear safety in Austria, Khan became acquainted with Indian physicist Raja Ramanna

Raja Ramanna (28 January 1925 – 24 September 2004) was an Indian physicist who is best known for his role in India's nuclear program during its early stages.

Having joined the nuclear program in 1964, Ramanna worked under Homi Jeha ...

when discussing topics in nuclear physics, briefly inviting the latter for a dinner at the Imperial Hotel Imperial Hotel or Hotel Imperial may refer to:

Hotels Australia

* Imperial Hotel, Ravenswood, Queensland

* Imperial Hotel, York, Western Australia

Austria

* Hotel Imperial, Vienna

India

* The Imperial, New Delhi

Ireland

* Imperial Hotel, D ...

where Ramanna confirmed the veracity of the information.

At this dinner, Khan reportedly warned Ramanna about a possible retaliatory nuclear strike at Trombay

Trombay is an eastern suburb in Bombay (Mumbai), India.

History

Trombay was called Neat's Tongue because of its shape. Once, it was an island nearly 5 km East of Mumbai and was about 8 km in length and 8 km in width. The island ...

if the Indian plans were to go ahead and urged Ramanna to relay this message to Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 and was al ...

, the Indian Prime Minister at that time. The message was delivered to the Indian Prime Minister's Office, and the Non-Nuclear Aggression Agreement treaty was signed to prevent nuclear accidents and accidental detonations between India and Pakistan in 1987.

Government work, academia and advocacy

In the 1980s, Khan emblemed in the federal government with a new type of technocratic role, a science adviser, becoming the spokesman of national science policy and advised the federal government to sign an agreement to ensure federal funding from China to commission the Chashma Nuclear Power Plant in 1987. In 1990, Khan advised the Benazir's administration to entered in negotiation with France over construction of nuclear power plant in Chashma. As chairing the PAEC in 1972, Khan played a crucial role in expanding the "''Reactor School''" which was housed in a lecture room located at the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology in Nilore and had only one faculty member, Dr. Inam-ur-Rehman, who often traveled to the United States to teach engineering at theMississippi State University

Mississippi State University for Agriculture and Applied Science, commonly known as Mississippi State University (MSU), is a public land-grant research university adjacent to Starkville, Mississippi. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Univ ...

. In 1976, Khan moved the ''Reactor School'' in Islamabad, renaming it as " Centre for Nuclear Studies (CNS)" and took the professorship in physics, as an unpaid part-time employment

A part-time job is a form of employment that carries fewer hours per week than a full-time job. They work in shifts. The shifts are often rotational. Workers are considered to be part-time if they commonly work fewer than 30 hours per week. Accor ...

, alongside Dr. Inam-ur-Rehman.

After his retirement from PAEC in 1991, Khan went to academia when he joined the faculty at the center for nuclear studies as a full-time professor to teach courses on physics while continuing to push for the CNS to be granted as university by the Higher Education Commission. In 1997, his dream was fulfilled when the federal government accepted his recommendation by granting the status of center for nuclear studies as a public university

A public university or public college is a university or college that is in owned by the state or receives significant public funds through a national or subnational government, as opposed to a private university. Whether a national universit ...

and renaming it as the Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences (PIEAS).

Final years

Death and legacy

Starting in 1972, Khan bought an estate in Islamabad and passed away following complications from heart surgery, aged 72, on 22 April 1999. He is survived by his wife, Thera, three children and four grandchildren.

When Abdus Salam was ejected from his position in 1974, Khan symbolized of many scientists thinking they could control how other peers would use their research. During the timeline of atomic bomb program, Khan was seen as a symbol of both

Starting in 1972, Khan bought an estate in Islamabad and passed away following complications from heart surgery, aged 72, on 22 April 1999. He is survived by his wife, Thera, three children and four grandchildren.

When Abdus Salam was ejected from his position in 1974, Khan symbolized of many scientists thinking they could control how other peers would use their research. During the timeline of atomic bomb program, Khan was seen as a symbol of both moral responsibility

In philosophy, moral responsibility is the status of morally deserving praise, blame, reward, or punishment for an act or omission in accordance with one's moral obligations.

Deciding what (if anything) counts as "morally obligatory" is a ...

of scientists, and to the contribution to the rise of Pakistan's science while preventing the politicization of the project. Popular depiction of Khan's views on nuclear proliferation as a confrontation between right-wing militarists who viewed that security interests with Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

incompatible (symbolized by Abdul Qadeer Khan) and left-wing intellectuals who viewed maintaining alliances with Western world (symbolized by Munir Khan) over the moral question of weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natu ...

.

In the 1990s, Khan was increasingly concerned about the potential danger that scientific inventions in nuclear applications could pose to humanity and stressed the difficulty of managing the power of scientific knowledge between scientists and lawmakers in an atmosphere in which the exchange of scientific ideas was hobbled by political concerns. During his time working in atomic bomb program, Khan was obsessed with secrecy and refused to meet with many journalists while he encouraged several scientists working on the classified projects to stay away from televised press and public to due to the sensitivity of their job.

As a scientist, Khan is remembered by his peers as brilliant researcher and engaging teacher, the founder of applied physics

Applied physics is the application of physics to solve scientific or engineering problems. It is usually considered to be a bridge or a connection between physics and engineering.

"Applied" is distinguished from "pure" by a subtle combination ...

in Pakistan. In 2007, Farhatullah Babar

Farhatullah Babar (Urdu/Pashto: ) is a Pakistani leftist politician, engineer and former senator. He is a prominent member of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), having served as a spokesperson for the party. He is a supporter of the Pashtun Tahaf ...

portrayed Khan as "tragic fate but consciously genius". Babar, F., ''Remembering Unsung Heroes: Munir Ahmed Khan'', Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, 28 April 2007 After years of urging of many of Khan's colleagues in PAEC and his powerful political friends who had ascended to power in the government, President Asif Ali Zardari

Asif Ali Zardari ( ur, ; sd, ; born 26 July 1955) is a Pakistani politician who is the president of Pakistan Peoples Party Parliamentarians and was the co-chairperson of Pakistan People's Party. He served as the 11th president of Pakistan ...

bestowed and honored Khan with the prestigious and highest civilian state award, Nishan-e-Imtiaz in 2012 as a gesture of political rehabilitation.

One of Khan's achievements is his technical leadership of the atomic bomb program, roughly modelled on the ''Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

'' that prevented the exploitation and politicization of the program in the hands of politicians, lawmakers, and military officials. The national project under Khan's technical directorship focused on developing his nation's atomic weapons and a diversified the nuclear technology for medical usage while he regarded this clandestine atomic bomb project as "building science and technology for Pakistan".

As military and public policy maker, Khan was a technocrat leader in a shift between science and military, and the emergence of the concept of the big science in Pakistan. During the Cold war, scientists became involved in military research on unprecedented degree, because of the threat communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

from Afghanistan and Indian integration posed to Pakistan, scientists volunteered in great numbers both for technological and organizational assistance to Pakistan's efforts that resulted in powerful tools such as laser science, the proximity fuse and operations research. As a cultured and intellectual physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

who became a disciplined military organizer, Khan represented the shift away from the idea that scientists had their "head in the clouds" and that knowledge on such previously esoteric subjects as the composition of the atomic nucleus had no "real-world" applications .

Throughout his life, Khan was honored with his nation's awards and honors:

* Nishan-e-Imtiaz (2012; Posthumous)

* Hilal-e-Imtiaz (1989)

* Gold medal

A gold medal is a medal awarded for highest achievement in a non-military field. Its name derives from the use of at least a fraction of gold in form of plating or alloying in its manufacture.

Since the eighteenth century, gold medals have bee ...

, PAS (1992)

* Fulbright Award

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people of ...

(1951)