Muir S. Fairchild on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1940, Fairchild went to the Plans Division in Washington and in 1941 was named secretary of the newly formed Air Staff. Two months later he was advanced two grades to brigadier general and named assistant chief of Air Corps. In 1942 he became director of military requirements and was promoted to major general in August. In November he became a member of the

In 1940, Fairchild went to the Plans Division in Washington and in 1941 was named secretary of the newly formed Air Staff. Two months later he was advanced two grades to brigadier general and named assistant chief of Air Corps. In 1942 he became director of military requirements and was promoted to major general in August. In November he became a member of the

Burial Detail: Fairchild, Muir S (Section 34, Grave 48-A)

– ANC Explorer

Air Force Historical Research Agency:

– Papers of Muri S. Fairchild, (1918–1950)

at ArlingtonCemetery.net, an unofficial website {{DEFAULTSORT:Fairchild, Muir S. United States Air Force generals United States Army Air Service pilots of World War I Muir S. Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) People from Bellingham, Washington 1894 births 1950 deaths Air Corps Tactical School alumni United States Army War College alumni Mackay Trophy winners Vice Chiefs of Staff of the United States Air Force Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

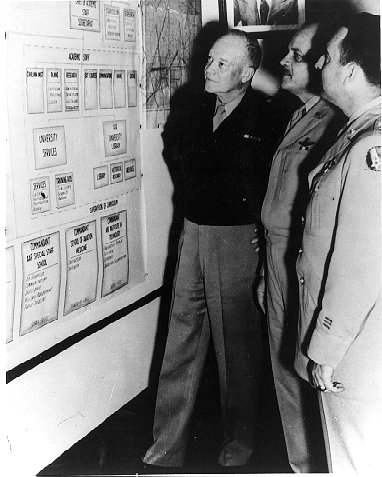

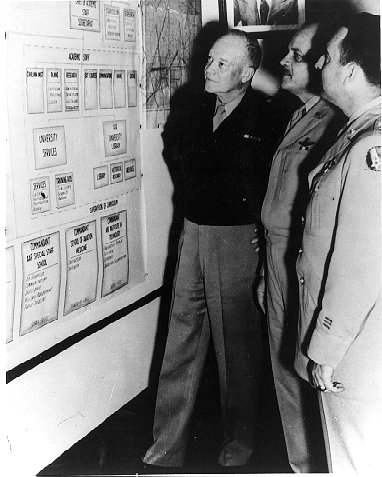

Muir Stephen Fairchild (September 2, 1894 – March 17, 1950) was a United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

officer and the service's second Vice Chief of Staff

A vice is a practice, behaviour, or Habit (psychology), habit generally considered immorality, immoral, sinful, crime, criminal, rude, taboo, depraved, degrading, deviant or perverted in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refe ...

.

Early service

Born inBellingham, Washington

Bellingham ( ) is the most populous city in, and county seat of Whatcom County in the U.S. state of Washington. It lies south of the U.S.–Canada border in between two major cities of the Pacific Northwest: Vancouver, British Columbia (locat ...

, Fairchild moved to Olympia in 1905 when his father was appointed by Governor Meade as chairman of Washington's first Railroad Commission. Muir graduated from Olympia High School (officially William Winlock Miller High School) in 1913, then entered the U.S. Army's

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

Signal Corps in 1913 in an Army Signal Corps reserve unit in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

, while he was a student at the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seattle a ...

. In 1916, he was deployed in the Washington National Guard

The Washington National Guard is one of the four elements of the State of Washington's Washington Military Department and a component of the National Guard of the United States. It is headquartered at Camp Murray, Washington and is defined by its ...

with the rank of sergeant, and his unit joined in the search for Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (,"Villa"

''Collins English Dictionary''. ; ;

along the Mexican border, where he spent much time in a horse saddle in the desert heat. Watching observation planes flying overhead in the United States' first armed conflict using airplanes, Fairchild was an easy recruit when flyboys were being sought to fight with the French and Italians in the developing war in Europe, before the U.S. entered ''Collins English Dictionary''. ; ;

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. A year later Fairchild became a flying cadet at Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, getting his wings and commission in the U.S. Army's Aviation Section in January 1918. Fairchild fought the Germans from the air over the Rhine, including night bombing missions, in an era when bombs were still being released from the hand grasp of the bombardier.

Between the wars

In December 1918 Fairchild returned home and served atMcCook Field

McCook Field was an airfield and aviation experimentation station in Dayton, Ohio, United States. It was operated by the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps and its successor the United States Army Air Service from 1917 to 1927. It was named fo ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

; Mitchel Field

Mitchell may refer to:

People

*Mitchell (surname)

*Mitchell (given name)

Places Australia

* Mitchell, Australian Capital Territory, a light-industrial estate

* Mitchell, New South Wales, a suburb of Bathurst

* Mitchell, Northern Territory ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, and Langley Field Langley may refer to:

People

* Langley (surname), a common English surname, including a list of notable people with the name

* Dawn Langley Simmons (1922–2000), English author and biographer

* Elizabeth Langley (born 1933), Canadian perform ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. On October 20, 1922 he was practicing dog fighting with Lt. Harold Ross Harris

Harold Ross Harris (December 20, 1895 – July 28, 1988) was a notable American test pilot and U.S. Army Air Force officer who held 26 flying records. He made the first flight by American pilots over the Alps from Italy to France, successfully ...

; when Harris lost control of his aircraft and was forced to parachute his way to safety; ironically nearly a year later August 22, 1923 both Harris and Fairchild piloted the US Military first heavy bomber the Witteman-Lewis XNBL-1

The Wittemann-Lewis NBL-1 "Barling Bomber"''Report on Official Performance Test of Barling Bomber, NLB-1, P-303, Light Load Configuration'', 14 April 1926. was an experimental long-range, heavy bomber built for the United States Army Air Service i ...

.

In 1926 and 1927, he flew to South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

as part of the Pan American Good Will Flight a pioneering flight that sought to promote air postal service, U.S. commercial aviation and take messages of friendship to the governments and people of Central and South America, while forging aerial navigation routes through the Americas. The flight originated with five aircraft and crews taking off from Kelly Field

Kelly Field (formerly Kelly Air Force Base) is a Joint-Use facility located in San Antonio, Texas. It was originally named after George E. M. Kelly, the first member of the U.S. military killed in the crash of an airplane he was piloting.

In ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

on December 21, 1926, seeking to land in 23 Central and South American countries.

The aircraft used for the journey were new observation planes, the Loening OA-1A that could be used as both landplanes and seaplanes, with Liberty engines and a wood interior structure with an aluminum-covered fuselage and fabric-covered wings. Each plane was named for a U.S. city and crewed by two pilots, one of whom was an engineering officer, since there were very few airfields or repair facilities along the route, with the crew choosing the motto "No Work, No Ride."

Crew of the New York: Maj. Herbert Dargue

Herbert Arthur "Bert" Dargue (November 17, 1886 – December 12, 1941) was a career officer in the United States Army, reaching the rank of major general in the Army Air Forces. He was a pioneer military aviator and one of the first ten recipi ...

, Lt. Ennis Whitehead

Ennis Clement Whitehead (September 3, 1895 – October 12, 1964) was an early United States Army aviator and a United States Army Air Forces general during World War II. Whitehead joined the U. S. Army after the United States entered World War I ...

;

Crew of the San Antonio: Capt. Arthur McDaniel, Lt. Charles Robinson;

Crew of the San Francisco: Capt. Ira Eaker

General (Honorary) Ira Clarence Eaker (April 13, 1896 – August 6, 1987) was a general of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. Eaker, as second-in-command of the prospective Eighth Air Force, was sent to England to form and ...

, Lt. Muir Fairchild;

Crew of the Detroit: Capt. Clinton F. Woolsey, Lt. John Benton;

Crew of the St. Louis: Lt. Bernard Thompson, Lt. Leonard Weddington

The flight was marred by tragedy when the Detroit and New York accidentally collided mid-air and got locked together. The crew of the New York were able to parachute to safety but Capt. Woolsley and Lt. Benton were killed when the Detroit hit the ground.

The Pan American Flyers were greeted by a cheering crowd including President Calvin Coolidge, Cabinet members, and diplomats from Central and Latin America when they returned to Bolling Field, Washington, D.C., on May 2, 1927.

Fairchild and the rest of the surviving Pan American Flight crew, and Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

, were among the first nine aviators to receive the newly created award Distinguished Flying Cross. The Pan Am Good Will Tour aviators were the first to be named to receive the Distinguished Flying Cross, Lindbergh's being named came after the Pan Am Good Will Tour members, though Lindbergh actually received his medal first.

Fairchild went on to complete the course in the Air Corps Engineer School at Wright Field

Wilbur Wright Field was a military installation and an airfield used as a World War I pilot, mechanic, and armorer training facility and, under different designations, conducted United States Army Air Corps and Air Forces flight testing. Loca ...

in June 1929 and went to Santa Monica, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, as Air Corps representative to Douglas Aircraft

The Douglas Aircraft Company was an American aerospace manufacturer based in Southern California. It was founded in 1921 by Donald Wills Douglas Sr. and later merged with McDonnell Aircraft in 1967 to form McDonnell Douglas; it then operated as ...

Corporation. In June 1935 he graduated from the Air Corps Tactical School

The Air Corps Tactical School, also known as ACTS and "the Tactical School", was a military professional development school for officers of the United States Army Air Service and United States Army Air Corps, the first such school in the world. C ...

, along with strategic bombing advocates Haywood S. Hansell

Haywood Shepherd Hansell Jr. (September 28, 1903 – November 14, 1988) was a general officer in the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) during World War II, and later the United States Air Force. He became an advocate of the doctrine o ...

, Barney Giles, Vernon M. Guymon

Vernon Melvin Guymon (November 1, 1898 – April 5, 1965) was a highly decorated mustang officer and naval aviator of the United States Marine Corps with the rank of brigadier general. A veteran of many conflicts, Guymon served as gunnery serge ...

, Laurence S. Kuter

General Laurence Sherman Kuter (May 28, 1905 – November 30, 1979) was a Cold War-era U.S. Air Force general and former commander of the North American Air Defense Command ( NORAD). Kuter (pronounced COO-ter) was born in Rockford, Illinois i ...

, Lawson H. M. Sanderson

Lawson Harry McPhearson Sanderson (July 22, 1895 – June 11, 1973) was an aviation pioneer of the United States Marine Corps with the rank of major general. He is most noted for his effort in development of the dive bombing technique. As comman ...

and Hoyt S. Vandenberg

Hoyt Sanford Vandenberg (January 24, 1899 – April 2, 1954) was a United States Air Force general. He served as the second Chief of Staff of the Air Force, and the second Director of Central Intelligence.

During World War II, Vandenberg was ...

, then became an Air Corps Tactical School

The Air Corps Tactical School, also known as ACTS and "the Tactical School", was a military professional development school for officers of the United States Army Air Service and United States Army Air Corps, the first such school in the world. C ...

instructor. He later attended the Army Industrial College

The Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy (Eisenhower School), formerly known as the Industrial College of the Armed Forces (ICAF), is a part of the National Defense University. It was renamed on September 6, 20 ...

, and the Army War College. He rose to director of air tactics and strategy in 1939.

Second World War

In 1940, Fairchild went to the Plans Division in Washington and in 1941 was named secretary of the newly formed Air Staff. Two months later he was advanced two grades to brigadier general and named assistant chief of Air Corps. In 1942 he became director of military requirements and was promoted to major general in August. In November he became a member of the

In 1940, Fairchild went to the Plans Division in Washington and in 1941 was named secretary of the newly formed Air Staff. Two months later he was advanced two grades to brigadier general and named assistant chief of Air Corps. In 1942 he became director of military requirements and was promoted to major general in August. In November he became a member of the Joint Strategic Survey Committee

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Post war

In January 1946, he was named commandant of Air University atMaxwell Field

Maxwell Air Force Base , officially known as Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base, is a United States Air Force (USAF) installation under the Air Education and Training Command (AETC). The installation is located in Montgomery, Alabama, United States. O ...

in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, with promotion to lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

. On May 27, 1948, he became the second vice chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force, with the rank of general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

. General Fairchild died of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may tr ...

at his quarters at Fort Myer

Fort Myer is the previous name used for a U.S. Army post next to Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, and across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. Founded during the American Civil War as Fort Cass and Fort Whipple, t ...

on March 17, 1950, while still on active duty as vice chief of staff at the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

. He was survived by his wife, Florence Alice Fairchild, and his daughter, Betsy Anne Calvert.

Legacy

Fairchild Hall, the main academic building at theUnited States Air Force Academy

The United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) is a United States service academy in El Paso County, Colorado, immediately north of Colorado Springs. It educates cadets for service in the officer corps of the United States Air Force and Uni ...

in Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

, and the library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

at the Air University in Alabama, Fairchild Memorial Hall

Fairchild Memorial Hall houses the Air University (AU) library at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama.

The premier library in the United States Department of Defense, the AU Library holds especially strong collections in the fields of warfare, aeron ...

, were named for him. In his home state of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

, Fairchild Air Force Base

Fairchild Air Force Base (AFB) is a United States Air Force base, located in the northwest United States in eastern Washington, approximately southwest of Spokane.

The host unit at Fairchild is the 92nd Air Refueling Wing (92 ARW) assigned t ...

near Spokane

Spokane ( ) is the largest city and county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It is in eastern Washington, along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south of the Ca ...

was named for him shortly after his death. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

.– ANC Explorer

References

External links

*Air Force Historical Research Agency:

– Papers of Muri S. Fairchild, (1918–1950)

at ArlingtonCemetery.net, an unofficial website {{DEFAULTSORT:Fairchild, Muir S. United States Air Force generals United States Army Air Service pilots of World War I Muir S. Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) People from Bellingham, Washington 1894 births 1950 deaths Air Corps Tactical School alumni United States Army War College alumni Mackay Trophy winners Vice Chiefs of Staff of the United States Air Force Burials at Arlington National Cemetery