Mountain Meadows Massacre And Mormon Theology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mormon theology has long been thought to be one of the causes of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. The victims of the massacre, known as the Baker–Fancher party, were passing through the Utah Territory to

Mormon historian

Mormon historian

At the time of the massacre, Mormons had an acute memory of recent persecutions against them, particularly the death of their prophets, and had been taught that God would soon exact vengeance. The persecutions began in the 1830s, when the state of

At the time of the massacre, Mormons had an acute memory of recent persecutions against them, particularly the death of their prophets, and had been taught that God would soon exact vengeance. The persecutions began in the 1830s, when the state of

Internet Archive versions

. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. * *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *

scanned versions

. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. * *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *.

by John G. Turner, ''

"Election Theology and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows"

by Seth Payne

"The Mountain Meadows Massacre"

by

"The Mountain Meadows Massacre"

an

from

"Refutation of falsehoods appearing in the ''Illustrated American,'' January 9, 1891"

by Wilford Woodruff

"A Great Tragedy: Emigrant trains in Utah"

from ''The Restored Church,'' by William E. Berrett {{Mountain Meadows massacre series, state=expanded Mountain Meadows Massacre Latter Day Saint belief and doctrine

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

in 1857. For the decade prior the emigrants' arrival, Utah Territory had existed as a theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy origina ...

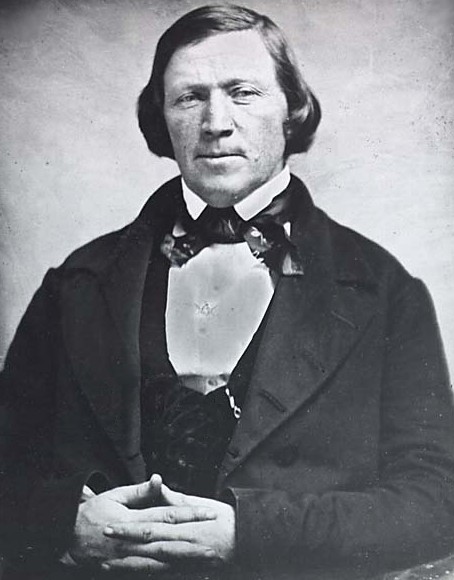

led by Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

. As part of Young's vision of a pre-millennial

Millennials, also known as Generation Y or Gen Y, are the Western demographic cohort following Generation X and preceding Generation Z. Researchers and popular media use the early 1980s as starting birth years and the mid-1990s to early 2000 ...

"Kingdom of God", Young established colonies along the California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

and Old Spanish Trails, where Mormon officials governed as leaders of church, state, and military. Two of the southernmost establishments were Parowan

Parowan ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Iron County, Utah, United States. The population was 2,790 at the 2010 census, and in 2018 the estimated population was 3,100.

Parowan became the first incorporated city in Iron County in 1851. A ...

and Cedar City, led respectively by Stake Presidents William H. Dame and Isaac C. Haight. Haight and Dame were, in addition, the senior regional military leaders of the Mormon militia

The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized militia of the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, United States. With growing antagonism from surrounding settlements it came to have as its main function the defense of Nauvoo, and surrounding Latter Day Saint ...

. During the period just before the massacre, known as the Mormon Reformation

The Mormon Reformation was a period of renewed emphasis on spirituality within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and a centrally-directed movement, which called for a spiritual reawakening among church members. It took p ...

, Mormon teachings were dramatic and strident. The religion had undergone a period of intense persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

in the American mid-west.

Utah Territory's political structure during the massacre

A decade prior the Baker–Fancher party's arrival,Mormons

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

had established in the Utah Territory a theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fro ...

community (''see'' theodemocracy

Theodemocracy is a theocratic political system proposed by Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. According to Smith, a theodemocracy is a fusion of traditional republican democratic principles—under the Unit ...

). There Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

presided over the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Christianity, Christian church that considers itself to be the Restorationism, restoration of the ...

as LDS Church president and Prophet of God, until Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, names and titles), was ...

's assumption of world kingship at his Second Coming. U.S. President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

appointed Young governor of the Territory of Utah and its Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Yet there was minimal effective separation between church and state until 1858.

Brigham Young envisioned a Mormon domain, called the '' State of Deseret'', spanning from the Salt Lake Valley

Salt Lake Valley is a valley in Salt Lake County in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Utah. It contains Salt Lake City and many of its suburbs, notably Murray, Sandy, South Jordan, West Jordan, and West Valley City; its total po ...

to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, and so he sent church leaders to establish colonies far and wide. These colonies were governed by Mormon officials under Brigham Young's mandate to enforce "God's law" by "lay ngthe ax at the root of the tree of sin and iniquity", while preserving individual rights. Despite the distance to these outlying colonies, local Mormon leaders received frequent visits from church headquarters, and were under Young's direct doctrinal and political control. Mormons were taught to obey the orders of their priesthood leaders, as long as they coincided with LDS gospel principles. Young's view of theocratic enforcement included a death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

for such sins as theft. However, there are no documented cases showing that such threats were ever enforced as actual policy, and there were no accusations of thievery against the Baker–Fancher party. Mormon leaders taught the doctrine of blood atonement, in which Mormon "covenant breakers" could in theory gain their exaltation

Exalt or exaltation may refer to:

* Exaltation (astrology), a characteristic of a planet in astrology

* Exaltation (Mormonism), a belief in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

* Exaltation of Christ or "Session of Christ", a Christian ...

in heaven by having "their blood spilt upon the ground, that the smoke thereof might ascend to heaven as an offering for their sins". More clearly stated, this doctrine holds that capital punishment is requisite for offenses of murder. Mormon leaders stated that this practice was not yet "in full force", but the time was "not far distant" when Mormons would be sacrificed out of love to ensure their eternal reward.

Mormon historian

Mormon historian Thomas G. Alexander

Thomas Glen Alexander (born August 8, 1935) is an American historian and academic who is a professor emeritus at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Provo, Utah, where he was also Lemuel Hardison Redd, Jr. Professor of Western History and director of ...

argues that most violent speech by LDS leaders was rhetorical in nature. He further states that statistical studies are needed in order to determine whether frontier Utah was in reality any more violent than surrounding regions. But he argues that the limited statistical evidence which does exist (although dating from the 1880s) shows Utah to be far less violent than other contemporaneous western states and territories. Referring to the frequent Mormon declarations that there were fewer deeds of violence in Utah than in other pioneer settlements of equal population, the Salt Lake Tribune reported on January 25, 1876: "It is estimated that no less than 600 murders have been committed by the Mormons, in nearly every case at the instigation of their priestly leaders, during the occupation of the territory. Giving a mean average of 50,000 persons professing that faith in Utah, we have a murder committed every year to every 2500 of population. The same ratio of crime extended to the population of the United States would give 16,000 murders every year." Brigham Young's typical response to such charges was undisguised sarcasm. Speaking on July 26, 1857, he stated "what is now the news circulated through the United States?...That Brigham Young has adkilled all the men who have died between the Missouri River and California." He had previously retorted to similar charges, "just one word from Brigham, and they are ready to slay all before them...It is all a pack of nonsense, the whole of it." Whatever the case, there is consensus that William H. Dame and Isaac C. Haight, the two most senior local church leaders in southern Utah complicit in the massacre, took the rhetoric of such doctrines seriously as they contemplated sanctionable applications of violence.

According to rumors and accusations, Brigham Young sometimes enforced "God's law" through a secret cadre of avenging Danite

The Danites were a fraternal organization founded by Latter Day Saint members in June 1838, in the town of Far West, Caldwell County, Missouri. During their period of organization in Missouri, the Danites operated as a vigilante group and took a ...

s. The truth of these rumors is debated by historians. While there existed active vigilante

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without Right, legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a pers ...

organizations in Utah who referred to themselves as "Danites", they may have been acting independently.

Historian Leonard Arrington

Leonard James Arrington (July 2, 1917 – February 11, 1999) was an American author, academic and the founder of the Mormon History Association. He is known as the "Dean of Mormon History" and "the Father of Mormon History" because of his man ...

attributes these rumors to the actions of "Minute Men," a law enforcement organization created by Young to pursue hostile Indians and criminals. However, these became associated with the Danite vigilantes which had operated briefly in Missouri in 1838. Haight and Dame were never Danites; however, Young's records indicate that in 1857 he authorized Haight and Dame to secretly execute two recently released convicts traveling through southern Utah along the California trail if they were caught stealing cattle or other livestock.. Dame replied to Young in a letter that "we try to live so when your finger crooks, we move". Haight and/or Dame might have been involved in the subsequent ambush of part of the convicts' party just south of Mountain Meadows.

Prior Mid-West persecution against Mormons and their calls for vengeance

At the time of the massacre, Mormons had an acute memory of recent persecutions against them, particularly the death of their prophets, and had been taught that God would soon exact vengeance. The persecutions began in the 1830s, when the state of

At the time of the massacre, Mormons had an acute memory of recent persecutions against them, particularly the death of their prophets, and had been taught that God would soon exact vengeance. The persecutions began in the 1830s, when the state of Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

officially opposed their presence in the state, engaged with them in the Mormon War, and expelled them in 1838 with an Extermination Order. During the Mormon War, prominent Mormon apostle David W. Patten

David Wyman Patten (November 14, 1799 – October 25, 1838) was an early leader in the Latter Day Saint movement and an original member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. He was killed at the Battle of Crooked River and is regarded as a martyr ...

died of wounds suffered after leading Mormon insurgents in an attack against the Missouri Militia at Crooked Creek, and a group of Mormons were massacred at Haun's Mill. After the Mormons established a new home in Nauvoo, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, in 1839, they were again forced to leave behind homes and land in Illinois after conflicts with locals culminated in the 1844 death of Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith, the founder and leader of the Latter Day Saint movement, and his brother, Hyrum Smith, were killed by a mob in Carthage, Illinois, United States, on June 27, 1844, while awaiting trial in the town jail.

As mayor of the city of N ...

and his brother, Patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and in certai ...

Hyrum Smith by a mob of Illinois militia. Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

led the majority of Mormons westward in 1846 to avoid civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

.

In Utah, just months before the Mountain Meadows Massacre, Mormons received word that yet another "prophet" had been killed: in April 1857, apostle Parley P. Pratt was shot in Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

by Hector McLean, the estranged husband of one of Pratt's plural wives, Eleanor McLean Pratt. Mormon leaders immediately proclaimed Pratt as another martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

, and compared his death with that of Joseph Smith. Many Mormons held the people of Arkansas responsible.

In 1857, Mormon leaders taught that the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

was imminent, and that God would soon exact punishment against the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

for persecuting Mormons and martyring "the prophets" Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

, Hyrum Smith, David W. Patten

David Wyman Patten (November 14, 1799 – October 25, 1838) was an early leader in the Latter Day Saint movement and an original member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. He was killed at the Battle of Crooked River and is regarded as a martyr ...

, and Parley P. Pratt. In their Endowment ceremony, faithful early Latter-day Saints took an Oath of vengeance against the murderers of the prophets. As a result of this oath, several Mormon apostles and other leaders considered it their religious duty to kill the prophets' murderers if they ever came across them.

The sermons, blessings, and private counsel by Mormon leaders just prior to the Mountain Meadows Massacre can be understood as encouraging private individuals to execute God's judgment against the wicked. In Cedar City, Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, church leaders taught that members should ignore dead bodies and go about their business. Col. William H. Dame, the ranking officer in southern Utah who ordered the Mountain Meadows Massacre, received a patriarchal blessing

In the Latter Day Saint movement, a patriarchal blessing (also called an evangelist's blessing) is an ordinance administered by the laying on of hands, with accompanying words of promise, counsel, and lifelong guidance intended solely for the rec ...

in 1854 that he would "be called to act at the head of a portion of thy Brethren and of the Lamanites

The Lamanites () are one of the four ancient peoples (along with the Jaredites, the Mulekites, and the Nephites) described as having settled in the ancient Americas in the Book of Mormon, a sacred text of the Latter Day Saint movement. The Lamani ...

(Native Americans) in the redemption of Zion and the avenging of the blood of the prophets upon them that dwell on the earth". In June 1857, Philip Klingensmith, another participant, was similarly blessed that he would participate in "avenging the blood of Brother Joseph". The train led by Alexander Fancher waited outside Salt Lake City for more than a week as other groups caught up with them. The other, led by Captain John Twitty Baker was the last to arrive. Here the groups decided which route to take across the Great Basin

The Great Basin is the largest area of contiguous endorheic basin, endorheic watersheds, those with no outlets, in North America. It spans nearly all of Nevada, much of Utah, and portions of California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, and Baja California ...

to California. The Northern route to the California Trail

The California Trail was an emigrant trail of about across the western half of the North American continent from Missouri River towns to what is now the state of California. After it was established, the first half of the California Trail f ...

, involved travelling along the Humboldt River

The Humboldt River is an extensive river drainage system located in north-central Nevada. It extends in a general east-to-west direction from its headwaters in the Jarbidge, Independence, and Ruby Mountains in Elko County, to its terminus in the ...

in Northern Nevada, west across the Nevada desert to California and across the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

mountains into Sacramento. This route put emigrants at risk of becoming snowbound in the Sierra Nevada mountains in California as the Donner party had done ten years before. The Southern route went to the Old Spanish Trail, which would take them through the settlements in Southern Utah, through Southern Nevada (now Las Vegas) and then West through the arid dry Mojave Desert

The Mojave Desert ( ; mov, Hayikwiir Mat'aar; es, Desierto de Mojave) is a desert in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the Southwestern United States. It is named for the indigenous Mojave people. It is located primarily in ...

of San Bernardino County and eventually into Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

basin. At least one couple, Henry D. and Malinda Cameron Scott, chose to take the Northern route while others from the woman's family went south with the united parties under Captain Fancher.

It was reported to Brigham Young that the party was from Arkansas. It was also rumored - as presented in the "Argus" letters later published in the ''Corinne Daily Reporter'' - that Eleanor McLean Pratt, one of the apostle Pratt's plural wives, recognized one of the party as being present at her husband's murder. (citing "Argus", an anonymous contributor to the ''Corinne Daily Reporter'' whom Stenhouse met and vouched for) Other sources, however, state that Eleanor Pratt herself was not present at the murder.: "At about half past noon a lady came to the hotel in Van Buren where Eleanor was staying and told her that Parley had been shot. ... After Eleanor received definite word that Parley was dead, she asked Marshal Hays if she and George Higginson might go prepare the body for burial."

Footnotes

Bibliography

*. *Internet Archive versions

. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. * *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *

scanned versions

. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. * *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *.

External links

by John G. Turner, ''

Christianity Today

''Christianity Today'' is an evangelical Christian media magazine founded in 1956 by Billy Graham. It is published by Christianity Today International based in Carol Stream, Illinois. ''The Washington Post'' calls ''Christianity Today'' "evange ...

''"Election Theology and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows"

by Seth Payne

"The Mountain Meadows Massacre"

by

Richard E. Turley Jr.

Richard Eyring "Rick" Turley Jr. (born February 18, 1956) is an American historian and genealogist. He previously served as both an Assistant Church Historian of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and as managing direct ...

, ''Ensign'', September 2000"The Mountain Meadows Massacre"

an

from

Comprehensive History of the Church

''A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Century I'' is a six-volume history published in 1930 and written by B.H. Roberts, a general authority and Assistant Church Historian of the The Church of Jesus Christ o ...

by B.H. Roberts

Brigham Henry Roberts (March 13, 1857 – September 27, 1933) was a historian, politician, and leader in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). He edited the seven-volume ''History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day ...

"Refutation of falsehoods appearing in the ''Illustrated American,'' January 9, 1891"

by Wilford Woodruff

"A Great Tragedy: Emigrant trains in Utah"

from ''The Restored Church,'' by William E. Berrett {{Mountain Meadows massacre series, state=expanded Mountain Meadows Massacre Latter Day Saint belief and doctrine