Mount Vesuvius on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

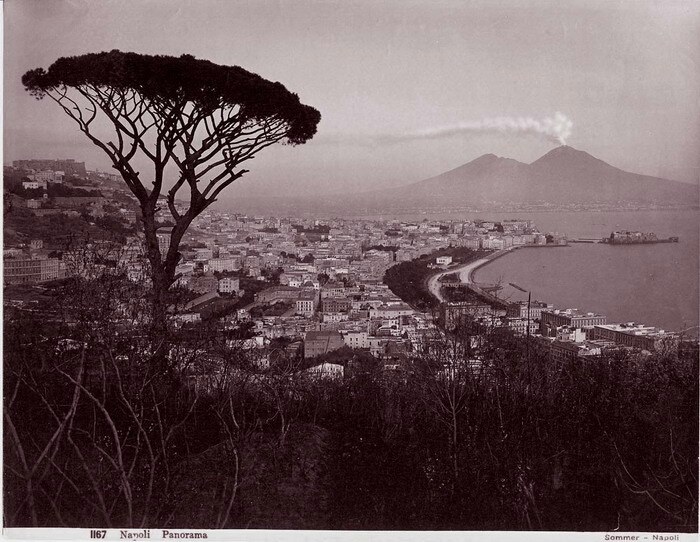

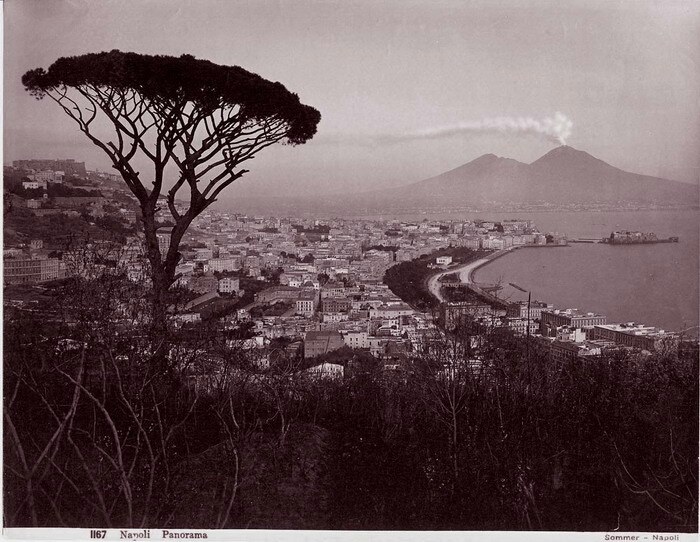

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma- stratovolcano located on the

Vesuvius is a "humpbacked" peak, consisting of a large cone (''Gran Cono'') partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera caused by the collapse of an earlier (and originally much higher) structure called Mount Somma. The Gran Cono was produced during the A.D. 79 eruption. For this reason, the volcano is also called Somma-Vesuvius or Somma-Vesuvio.

The caldera started forming during an eruption around 17,000–18,000 years ago and was enlarged by later paroxysmal eruptions, ending in the one of AD 79. This structure has given its name to the term " somma volcano", which describes any volcano with a summit caldera surrounding a newer cone.

The cliffs forming the northern ridge of Monte Somma's caldera rim reach a maximum height of at Punta Nasone. The summit of the main cone of Vesuvius is above sea level and more than above the long valley of Atrio di Cavallo (the northern floor of Monte Somma's caldera).

The volcano's slopes are scarred by lava flows, while the rest are heavily vegetated, with scrub and forests at higher altitudes and vineyards lower down.

Vesuvius is a "humpbacked" peak, consisting of a large cone (''Gran Cono'') partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera caused by the collapse of an earlier (and originally much higher) structure called Mount Somma. The Gran Cono was produced during the A.D. 79 eruption. For this reason, the volcano is also called Somma-Vesuvius or Somma-Vesuvio.

The caldera started forming during an eruption around 17,000–18,000 years ago and was enlarged by later paroxysmal eruptions, ending in the one of AD 79. This structure has given its name to the term " somma volcano", which describes any volcano with a summit caldera surrounding a newer cone.

The cliffs forming the northern ridge of Monte Somma's caldera rim reach a maximum height of at Punta Nasone. The summit of the main cone of Vesuvius is above sea level and more than above the long valley of Atrio di Cavallo (the northern floor of Monte Somma's caldera).

The volcano's slopes are scarred by lava flows, while the rest are heavily vegetated, with scrub and forests at higher altitudes and vineyards lower down.

Vesuvius is a stratovolcano and was formed as a result of the collision of two tectonic plates, the African and the Eurasian. The former was

Vesuvius is a stratovolcano and was formed as a result of the collision of two tectonic plates, the African and the Eurasian. The former was

Mount Vesuvius has erupted many times. Numerous others preceded the eruption in AD 79 in prehistory, including at least three significantly larger; an example is the

Mount Vesuvius has erupted many times. Numerous others preceded the eruption in AD 79 in prehistory, including at least three significantly larger; an example is the

Scientific knowledge of the geologic history of Vesuvius comes from core samples taken from a plus borehole on the flanks of the volcano, extending into

Scientific knowledge of the geologic history of Vesuvius comes from core samples taken from a plus borehole on the flanks of the volcano, extending into  * The volcano was then quiet (for 295 years, if the 217 BC date for the last previous eruption is true) and was described by Roman writers as having been covered with gardens and vineyards, except at the top, which was craggy. The volcano may have had only one summit at that time, judging by a wall painting, "Bacchus and Vesuvius", found in a Pompeian house, the House of the Centenary (''Casa del Centenario'').

Several surviving works written over the 200 years preceding the AD 79 eruption describe the mountain as having had a volcanic nature, although Pliny the Elder did not depict the mountain in this way in his '' Naturalis Historia'':

* The Greek historian Strabo (ca. 63 BC – 24 AD) described the mountain in Book V, Chapter 4 of his '' Geographica'' as having a predominantly flat, barren summit covered with sooty, ash-coloured rocks, and suggested that it might once have had "craters of fire". He also perceptively suggested that the fertility of the surrounding slopes may be due to volcanic activity, as at Mount Etna.

* In Book II of '' De architectura'', the architect

* The volcano was then quiet (for 295 years, if the 217 BC date for the last previous eruption is true) and was described by Roman writers as having been covered with gardens and vineyards, except at the top, which was craggy. The volcano may have had only one summit at that time, judging by a wall painting, "Bacchus and Vesuvius", found in a Pompeian house, the House of the Centenary (''Casa del Centenario'').

Several surviving works written over the 200 years preceding the AD 79 eruption describe the mountain as having had a volcanic nature, although Pliny the Elder did not depict the mountain in this way in his '' Naturalis Historia'':

* The Greek historian Strabo (ca. 63 BC – 24 AD) described the mountain in Book V, Chapter 4 of his '' Geographica'' as having a predominantly flat, barren summit covered with sooty, ash-coloured rocks, and suggested that it might once have had "craters of fire". He also perceptively suggested that the fertility of the surrounding slopes may be due to volcanic activity, as at Mount Etna.

* In Book II of '' De architectura'', the architect

Reconstructions of the eruption and its effects vary considerably in the details but have the same overall features. The eruption lasted two days. The morning of the first day was perceived as normal by the only eyewitness to leave a surviving document, Pliny the Younger. In the middle of the day, an explosion threw up a high-altitude column from which ash and pumice began to fall, blanketing the area. Rescues and escapes occurred during this time. At some time in the night or early the next day, pyroclastic surges in the close vicinity of the volcano began. Lights were seen on the peak, interpreted as fires. People as far away as Misenum fled for their lives. The flows were rapid-moving, dense and very hot, knocking down, wholly or partly, all structures in their path, incinerating or suffocating all population remaining there and altering the landscape, including the coastline. Additional light tremors accompanied these and a mild

Reconstructions of the eruption and its effects vary considerably in the details but have the same overall features. The eruption lasted two days. The morning of the first day was perceived as normal by the only eyewitness to leave a surviving document, Pliny the Younger. In the middle of the day, an explosion threw up a high-altitude column from which ash and pumice began to fall, blanketing the area. Rescues and escapes occurred during this time. At some time in the night or early the next day, pyroclastic surges in the close vicinity of the volcano began. Lights were seen on the peak, interpreted as fires. People as far away as Misenum fled for their lives. The flows were rapid-moving, dense and very hot, knocking down, wholly or partly, all structures in their path, incinerating or suffocating all population remaining there and altering the landscape, including the coastline. Additional light tremors accompanied these and a mild

Along with Pliny, the Elder, the only other noble casualties of the eruption to be known by name were Agrippa (a son of the Herodian Jewish princess Drusilla and the procurator Antonius Felix) and his wife.

By 2003, around 1,044 casts made from impressions of bodies in the ash deposits had been recovered in and around Pompeii, with the scattered bones of another 100. The remains of about 332 bodies have been found at Herculaneum (300 in arched vaults discovered in 1980). What percentage these numbers are of the total dead or the percentage of the dead to the total number at risk remain unknown.

Thirty-eight percent of the 1,044 were found in the ash fall deposits, the majority inside buildings. These are thought to have been killed mainly by roof collapses, with the smaller number of victims found outside of buildings probably being killed by falling roof slates or by larger rocks thrown out by the volcano. The remaining 62% of remains found at Pompeii were in the pyroclastic surge deposits, and thus were probably killed by them – probably from a combination of suffocation from inhaling ashes and blast and debris thrown around. Examination of cloth, frescoes and skeletons shows that, in contrast to the victims found at Herculaneum, it is unlikely that high temperatures were a significant cause of the destruction at Pompeii. Herculaneum, much closer to the crater, was saved from tephra falls by the wind direction but was buried under of material deposited by pyroclastic surges. Likely, most of the known victims in this town were killed by the surges.

People caught on the former seashore by the first surge died of thermal shock. The rest were concentrated in arched chambers at a density of as high as three persons per square metre. As only of the coast have been excavated, further casualties may be discovered.

Along with Pliny, the Elder, the only other noble casualties of the eruption to be known by name were Agrippa (a son of the Herodian Jewish princess Drusilla and the procurator Antonius Felix) and his wife.

By 2003, around 1,044 casts made from impressions of bodies in the ash deposits had been recovered in and around Pompeii, with the scattered bones of another 100. The remains of about 332 bodies have been found at Herculaneum (300 in arched vaults discovered in 1980). What percentage these numbers are of the total dead or the percentage of the dead to the total number at risk remain unknown.

Thirty-eight percent of the 1,044 were found in the ash fall deposits, the majority inside buildings. These are thought to have been killed mainly by roof collapses, with the smaller number of victims found outside of buildings probably being killed by falling roof slates or by larger rocks thrown out by the volcano. The remaining 62% of remains found at Pompeii were in the pyroclastic surge deposits, and thus were probably killed by them – probably from a combination of suffocation from inhaling ashes and blast and debris thrown around. Examination of cloth, frescoes and skeletons shows that, in contrast to the victims found at Herculaneum, it is unlikely that high temperatures were a significant cause of the destruction at Pompeii. Herculaneum, much closer to the crater, was saved from tephra falls by the wind direction but was buried under of material deposited by pyroclastic surges. Likely, most of the known victims in this town were killed by the surges.

People caught on the former seashore by the first surge died of thermal shock. The rest were concentrated in arched chambers at a density of as high as three persons per square metre. As only of the coast have been excavated, further casualties may be discovered.

The New York Times, 6 April 1906Vesuvius Threatens Destruction Of Towns; Bosco Trecase Abandoned

The New York Times, 7 April 1906 killed more than 100 people and ejected the most lava ever recorded from a Vesuvian eruption. Italian authorities were preparing to hold the 1908 Summer Olympics when Mount Vesuvius violently erupted, devastating the city of The eruption could be seen from Naples. Different perspectives and the damage caused to the local villages were recorded by USAAF photographers and other personnel based nearer to the volcano.

The eruption could be seen from Naples. Different perspectives and the damage caused to the local villages were recorded by USAAF photographers and other personnel based nearer to the volcano.

The government emergency plan for an eruption therefore assumes that the worst case will be an eruption of similar size and type to the 1631 VEI 4 eruption. In this scenario, the volcano's slopes, extending out to about from the vent, may be exposed to pyroclastic surges sweeping down them, whilst much of the surrounding area could suffer from tephra falls. Because of prevailing winds, towns and cities south and east of the volcano are most at risk from this. It is assumed that tephra accumulation exceeding —at which point people are at risk from collapsing roofs—may extend out as far as Avellino to the east or

The government emergency plan for an eruption therefore assumes that the worst case will be an eruption of similar size and type to the 1631 VEI 4 eruption. In this scenario, the volcano's slopes, extending out to about from the vent, may be exposed to pyroclastic surges sweeping down them, whilst much of the surrounding area could suffer from tephra falls. Because of prevailing winds, towns and cities south and east of the volcano are most at risk from this. It is assumed that tephra accumulation exceeding —at which point people are at risk from collapsing roofs—may extend out as far as Avellino to the east or  Ongoing efforts are being made by the government at various levels (especially of

Ongoing efforts are being made by the government at various levels (especially of

Gulf of Naples

The Gulf of Naples (), also called the Bay of Naples, is a roughly 15-kilometer-wide (9.3 mi) gulf located along the south-western coast of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is ...

in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuvius consists of a large cone partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera, resulting from the collapse of an earlier, much higher structure.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 destroyed the Roman cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the ...

, Oplontis, Stabiae, and several other settlements. The eruption ejected a cloud of stones, ashes

Ashes may refer to:

*Ash, the solid remnants of fires.

Media and entertainment Art

* ''Ashes'' (Munch), an 1894 painting by Edvard Munch

Film

* ''The Ashes'' (film), a 1965 Polish film by director Andrzej Wajda

* ''Ashes'' (1922 film), a ...

and volcanic gases to a height of , erupting molten rock and pulverized pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular v ...

at the rate of per second. More than 1,000 people are thought to have died in the eruption, though the exact toll is unknown. The only surviving eyewitness account of the event consists of two letters by Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

.

Vesuvius has erupted many times since. It is the only volcano on Europe's mainland to have erupted in the last hundred years. It is regarded as one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world because 3,000,000 people live near enough to be affected by an eruption, with 600,000 in the danger zone. This is the most densely populated volcanic region in the world. Eruptions tend to be violent and explosive; these are known as Plinian eruptions.

Mythology

Vesuvius has a long historic and literary tradition. It was considered a divinity of the Genius type at the time of the eruption of AD 79: it appears under the inscribed name Vesuvius as a serpent in the decorative frescos of many ', or household shrines, surviving from Pompeii. An inscription fromCapua

Capua ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, situated north of Naples, on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History

Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etrusc ...

to indicates that he was worshipped as a power of Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandt ...

; that is, ''Jupiter Vesuvius''.

The Romans regarded Mount Vesuvius to be devoted to Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted th ...

. The historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

relates a tradition that Hercules, in the performance of his labors, passed through the country of nearby Cumae on his way to Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and found there a place called "the Phlegraean Plain" ( ''Φλεγραῖον πεδίον'', "plain of fire"), "from a hill which anciently vomited out fire ... now called Vesuvius." It was inhabited by giant bandits, "the sons of the Earth. With the gods' assistance, he pacified the region and continued. The facts behind the tradition, if any, remain unknown, as does whether was named after it. An epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two mille ...

by the poet Martial in 88 AD suggests that both Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

, patroness of Pompeii, and Hercules were worshipped in the region devastated by the eruption of 79.

Etymology

' was a name of the volcano in frequent use by the authors of the lateRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingd ...

and the early Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

. Its collateral forms were ', ', ' and '. Writers in ancient Greek used or . Many scholars since then have offered an etymology

Etymology () The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the form of words ...

. As peoples of varying ethnicity and language occupied Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

in the Roman Iron Age, the etymology depends to a large degree on the presumption of what language was spoken there at the time. Naples was settled by Greeks, as the name ', "New City", testifies. The Oscans, an Italic people, lived in the countryside. The Latins

The Latins were originally an Italic tribe in ancient central Italy from Latium. As Roman power and colonization spread Latin culture during the Roman Republic.

Latins culturally "Romanized" or "Latinized" the rest of Italy, and the word Latin ...

also competed for the occupation of Campania. Etruscan settlements were in the vicinity. Other peoples of unknown provenance are said to have been there at some time by various ancient authors.

Some theories about its origin are:

* From Greek = "not" prefixed to a root from or related to the Greek word = "I quench", in the sense of "unquenchable".

* From Greek = "I hurl" and "violence", "hurling violence", *vesbia, taking advantage of the collateral form.

* From an Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, ...

root, *eus- < *ewes- < *h₁ews-, "shine", "burn", sense "the one who lightens", through Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

or

* From an Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, ...

root *wes = " hearth" (compare e.g. Vesta

Vesta may refer to:

Fiction and mythology

* Vesta (mythology), Roman goddess of the hearth and home

* Vesta (Marvel Comics), a Marvel Comics character

* Sailor Vesta, a character in ''Sailor Moon''

Brands and products

* Lada Vesta, a car from ...

)

Topography

Vesuvius is a "humpbacked" peak, consisting of a large cone (''Gran Cono'') partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera caused by the collapse of an earlier (and originally much higher) structure called Mount Somma. The Gran Cono was produced during the A.D. 79 eruption. For this reason, the volcano is also called Somma-Vesuvius or Somma-Vesuvio.

The caldera started forming during an eruption around 17,000–18,000 years ago and was enlarged by later paroxysmal eruptions, ending in the one of AD 79. This structure has given its name to the term " somma volcano", which describes any volcano with a summit caldera surrounding a newer cone.

The cliffs forming the northern ridge of Monte Somma's caldera rim reach a maximum height of at Punta Nasone. The summit of the main cone of Vesuvius is above sea level and more than above the long valley of Atrio di Cavallo (the northern floor of Monte Somma's caldera).

The volcano's slopes are scarred by lava flows, while the rest are heavily vegetated, with scrub and forests at higher altitudes and vineyards lower down.

Vesuvius is a "humpbacked" peak, consisting of a large cone (''Gran Cono'') partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera caused by the collapse of an earlier (and originally much higher) structure called Mount Somma. The Gran Cono was produced during the A.D. 79 eruption. For this reason, the volcano is also called Somma-Vesuvius or Somma-Vesuvio.

The caldera started forming during an eruption around 17,000–18,000 years ago and was enlarged by later paroxysmal eruptions, ending in the one of AD 79. This structure has given its name to the term " somma volcano", which describes any volcano with a summit caldera surrounding a newer cone.

The cliffs forming the northern ridge of Monte Somma's caldera rim reach a maximum height of at Punta Nasone. The summit of the main cone of Vesuvius is above sea level and more than above the long valley of Atrio di Cavallo (the northern floor of Monte Somma's caldera).

The volcano's slopes are scarred by lava flows, while the rest are heavily vegetated, with scrub and forests at higher altitudes and vineyards lower down.

Formation

Vesuvius is a stratovolcano and was formed as a result of the collision of two tectonic plates, the African and the Eurasian. The former was

Vesuvius is a stratovolcano and was formed as a result of the collision of two tectonic plates, the African and the Eurasian. The former was subducted

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

at a convergent boundary beneath the latter, deeper into the earth. As the water-saturated sediments of the African oceanic plate were pushed to hotter depths inside the planet, the water boiled off and lowered the melting point of the upper mantle enough to partially melt the rocks. Because magma is less dense than the solid rock around it, it was pushed upward. Finding a weak spot at the Earth's surface, it broke through, thus forming the volcano.

The volcano is one of several forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Others include Campi Flegrei, a large caldera a few kilometers to the north-west, Mount Epomeo, to the west on the island of Ischia, and several undersea volcanoes to the south. The arc forms the southern end of a larger chain of volcanoes produced by the subduction process described above, which extends northwest along the length of Italy as far as Monte Amiata in Southern Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

. Vesuvius is the only one to have erupted in recent history, although some of the others have erupted within the last few hundred years. Many are either extinct or have not erupted for tens of thousands of years.

Eruptions

Mount Vesuvius has erupted many times. Numerous others preceded the eruption in AD 79 in prehistory, including at least three significantly larger; an example is the

Mount Vesuvius has erupted many times. Numerous others preceded the eruption in AD 79 in prehistory, including at least three significantly larger; an example is the Avellino eruption

The Avellino eruption of Mount Vesuvius refers to a Vesuvian eruption in 1995 BC. It is estimated to have had a VEI of 6, making it larger and more catastrophic than Vesuvius's more famous and well-documented 79 AD eruption. It is the sour ...

around 1800 BC, which engulfed several Bronze Age settlements. Since AD 79, the volcano has also erupted repeatedly, in 172, 203, 222, possibly in 303, 379, 472, 512, 536, 685, 787, around 860, around 900, 968, 991, 999, 1006, 1037, 1049, around 1073, 1139, 1150, and there may have been eruptions in 1270, 1347, and 1500.

The volcano erupted again in 1631, six times in the 18th century (including 1779 and 1794), eight times in the 19th century (notably in 1872), and in 1906, 1929 and 1944. There have been no eruptions since 1944, and none of the eruptions after AD 79 were as large or destructive as the Pompeian one.

The eruptions vary greatly in severity but are characterized by explosive outbursts of the kind dubbed Plinian after Pliny the Younger, a Roman writer who published a detailed description of the AD 79 eruption, including his uncle's death. On occasion, eruptions from Vesuvius have been so large that the whole of southern Europe has been blanketed by ash; in 472 and 1631, Vesuvian ash fell on Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

(Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

), over away. A few times since 1944, landslides in the crater have raised clouds of ash dust, raising false alarms of an eruption.

Since 1750, seven of the eruptions of Vesuvius have had durations of more than five years; only Mount Etna has had as many long-duration eruptions in the last 270 years. The two most recent eruptions of Vesuvius (1875–1906 and 1913–1944) each lasted more than 30 years.

Vesuvius is still regarded as an active volcano, although its current activity produces little more than sulfur-rich steam from vents at the bottom and walls of the crater.

Layers of lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock ( magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or ...

, ash, scoria and pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular v ...

make up the volcanic peak. Their mineralogy is variable, but generally silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is o ...

-undersaturated and rich in potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin '' kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmosp ...

, with phonolite produced in the more explosive eruptions (e.g. the eruption in 1631 displaying a complete stratigraphic and petrographic description: phonolite was firstly erupted, followed by a tephritic phonolite Tephriphonolite or tephri-phonolite is a mafic to intermediate extrusive igneous rock in composition between phonotephrite and phonolite. It contains 9 to 14% alkali content and 48 to 57% silica content (see TAS diagram). Tephriphonolite is ro ...

and finally a phonolitic tephrite).

Volcanic explosivity index

According to theSmithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

's Global Volcanism Program, Vesuvius has had 54 confirmed eruptions during the Holocene Epoch (the last 11,700 years). A volcanic explosivity index (VEI) has been assigned to all but one of these eruptions.

Before AD 79

Scientific knowledge of the geologic history of Vesuvius comes from core samples taken from a plus borehole on the flanks of the volcano, extending into

Scientific knowledge of the geologic history of Vesuvius comes from core samples taken from a plus borehole on the flanks of the volcano, extending into Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Creta ...

rock. Cores were dated by potassium–argon and argon–argon dating. The area has been subject to volcanic activity for at least 400,000 years; the lowest layer of eruption material from the Somma caldera lies on top of the 40,000-year‑old Campanian ignimbrite produced by the Campi Flegrei complex. The volcanic complex stands on a large, sedimentary plain.

*25,000 years ago: Vesuvius started forming in the Codola Plinian eruption.

*Vesuvius was then built up by a series of lava flows, with some smaller explosive eruptions interspersed between them. By this time, the volcano was 2,000 meters (6,560 feet) tall, with the summit being 500 meters (1,640 feet) east of the current summit.

*About 19,000 years ago: the style of eruption changed to a sequence of large explosive and caldera-forming Plinian eruptions, of which the AD 79 one was the most recent. The calderas are aligned in a roughly east-west direction, and all contributed to forming present-day's Somma caldera. The eruptions are named after the tephra deposits produced by them, which in turn are named after the place where the deposits were first identified:

* 18,300 years ago: the Basal Pumice (Pomici di Base) eruption, VEI 6, the original formation of the Somma caldera. The caldera's formation was asymmetric towards the west. The eruption was followed by a period of much less violent, lava-producing eruptions.

* 16,000 years ago: the Green Pumice (Pomici Verdoline) eruption, VEI 5.

* Around 11,000 years ago: the Lagno Amendolare eruption, smaller than the Mercato eruption.

* 8,000 years ago: the Mercato eruption

The Mercato eruption (Pomici di Mercato) of Mount Vesuvius was a Plinian eruption that occurred around 8,010 ± 40 14C yr BP (8,890 ± 90 cal yr BP).

The Global Volcanism Program claims that the eruption had a Volcanic Explosivity I ...

(Pomici di Mercato) – also known as Pomici Gemelle or Pomici Ottaviano, VEI 6.

* Around 5,000 years ago: two explosive eruptions smaller than the Avellino eruption.

* 3,800 years ago (19th century BC): the Avellino eruption

The Avellino eruption of Mount Vesuvius refers to a Vesuvian eruption in 1995 BC. It is estimated to have had a VEI of 6, making it larger and more catastrophic than Vesuvius's more famous and well-documented 79 AD eruption. It is the sour ...

(Pomici di Avellino), VEI 6; its vent was apparently west of the current crater and the eruption destroyed several Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

settlements of the Apennine culture, including ancient Afragola. Several carbon dates on wood and bones offer a range of possible dates of about 500 years in the mid-2nd millennium BC. In May 2001, near Nola, Italian archaeologists using the technique of filling every cavity with plaster or substitute compound, recovered some remarkably well-preserved forms of perishable objects, such as fence rails, a bucket and especially in the vicinity, thousands of human footprints pointing into the Apennines to the north. The settlement had huts, pots and goats. The residents had hastily abandoned the village, leaving it to be buried under pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular v ...

and ash in much the same way that Pompeii and Herculaneum were later preserved. Pyroclastic surge deposits were distributed to the northwest of the vent, travelling as far as from it, and lie up to deep in the area now occupied by Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

.

* The volcano then entered a stage of more frequent, but less violent eruptions, until the most recent Plinian eruption, which destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the ...

. Evidence of these eruptions comes from badly preserved ashfall deposits that have been dubitatively assigned to Either the Somma-Vesuvius complex, or the Phlegrean fields.

* The last of these may have been in 217 BC. There were earthquakes in Italy during that year and the sun was reported as being dimmed by gray haze or dry fog. Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

wrote of the sky being on fire near Naples, and Silius Italicus mentioned in his epic poem '' Punica'' that Vesuvius had thundered and produced flames worthy of Mount Etna in that year. However, both authors were writing around 250 years later. Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is ...

ice core samples of around that period show relatively high acidity, which is assumed to have been caused by atmospheric hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The und ...

.

* The volcano was then quiet (for 295 years, if the 217 BC date for the last previous eruption is true) and was described by Roman writers as having been covered with gardens and vineyards, except at the top, which was craggy. The volcano may have had only one summit at that time, judging by a wall painting, "Bacchus and Vesuvius", found in a Pompeian house, the House of the Centenary (''Casa del Centenario'').

Several surviving works written over the 200 years preceding the AD 79 eruption describe the mountain as having had a volcanic nature, although Pliny the Elder did not depict the mountain in this way in his '' Naturalis Historia'':

* The Greek historian Strabo (ca. 63 BC – 24 AD) described the mountain in Book V, Chapter 4 of his '' Geographica'' as having a predominantly flat, barren summit covered with sooty, ash-coloured rocks, and suggested that it might once have had "craters of fire". He also perceptively suggested that the fertility of the surrounding slopes may be due to volcanic activity, as at Mount Etna.

* In Book II of '' De architectura'', the architect

* The volcano was then quiet (for 295 years, if the 217 BC date for the last previous eruption is true) and was described by Roman writers as having been covered with gardens and vineyards, except at the top, which was craggy. The volcano may have had only one summit at that time, judging by a wall painting, "Bacchus and Vesuvius", found in a Pompeian house, the House of the Centenary (''Casa del Centenario'').

Several surviving works written over the 200 years preceding the AD 79 eruption describe the mountain as having had a volcanic nature, although Pliny the Elder did not depict the mountain in this way in his '' Naturalis Historia'':

* The Greek historian Strabo (ca. 63 BC – 24 AD) described the mountain in Book V, Chapter 4 of his '' Geographica'' as having a predominantly flat, barren summit covered with sooty, ash-coloured rocks, and suggested that it might once have had "craters of fire". He also perceptively suggested that the fertility of the surrounding slopes may be due to volcanic activity, as at Mount Etna.

* In Book II of '' De architectura'', the architect Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

(c. 80–70 BC –?) reported that fires had once existed abundantly below the peak and that it had spouted fire onto the surrounding fields. He described Pompeiian pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular v ...

as having been burnt from another species of stone.

* Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

(c. 90 BC – c. 30 BC), another Greek writer, wrote in Book IV of his ''Bibliotheca Historica'' that the Campanian plain was called fiery (''Phlegrean'') because of the peak, Vesuvius, which had spouted flames like Etna and showed signs of the fire that had burnt in ancient history.

Eruption of AD 79

In AD 79, Vesuvius erupted in one of the most catastrophic eruptions of all time. Historians have learned about the eruption from theeyewitness

Eyewitness or eye witness may refer to:

Witness

* Witness, someone who has knowledge acquired through first-hand experience

** Eyewitness memory

** Eyewitness testimony

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Eyewitness'' (1956 film), a Britis ...

account of Pliny the Younger, a Roman administrator and poet. Several dates are given in the surviving copies of the letters. The latest evidence supports earlier findings and indicates that the eruption occurred after 17 October.

The volcano ejected a cloud of stones, ashes

Ashes may refer to:

*Ash, the solid remnants of fires.

Media and entertainment Art

* ''Ashes'' (Munch), an 1894 painting by Edvard Munch

Film

* ''The Ashes'' (film), a 1965 Polish film by director Andrzej Wajda

* ''Ashes'' (1922 film), a ...

and volcanic gases to a height of , spewing molten rock and pulverized pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular v ...

at the rate of per second, ultimately releasing 100,000 times the thermal energy

The term "thermal energy" is used loosely in various contexts in physics and engineering. It can refer to several different well-defined physical concepts. These include the internal energy or enthalpy of a body of matter and radiation; heat, ...

released by the Hiroshima-Nagasaki bombings. The cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the ...

were destroyed by pyroclastic surges and the ruins buried under tens of metres of tephra.

Precursors and foreshocks

The AD 79 eruption was preceded by a powerful earthquake in 62, which caused widespread destruction around the Bay of Naples, and particularly to Pompeii. Some of the damage had still not been repaired when the volcano erupted. The deaths of 600 sheep from "tainted air" in the vicinity of Pompeii indicates that the earthquake of AD 62 may have been related to new activity by Vesuvius. The Romans grew accustomed to minor earth tremors in the region; the writer Pliny the Younger even wrote that they "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania". Small earthquakes started taking place four days before the eruption becoming more frequent over the next four days, but the warnings were not recognized.Scientific analysis

tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater exp ...

in the Bay of Naples. By late afternoon of the second day, the eruption was over, leaving only haze in the atmosphere through which the sun shone weakly.

The latest scientific studies of the ash produced by Vesuvius reveal a multi-phase eruption. The initial major explosion produced a column of ash and pumice ranging between high, which rained on Pompeii to the southeast but not on Herculaneum upwind. The chief energy supporting the column came from the escape of steam superheated by the magma, created from seawater seeping over time into the deep faults of the region, which interacted with magma.

Subsequently, the cloud collapsed as the gases expanded and lost their capability to support their solid contents, releasing it as a pyroclastic surge, which first reached Herculaneum but not Pompeii. Additional blasts reinstituted the column. The eruption alternated between Plinian and Peléan six times. Surges 3 and 4 are believed by the authors to have buried Pompeii. Surges are identified in the deposits by dune and cross-bedding formations, which are not produced by fallout.

Another study used the magnetic characteristics of over 200 samples of roof-tile and plaster fragments collected around Pompeii to estimate the equilibrium temperature of the pyroclastic flow. The magnetic study revealed that on the first day of the eruption a fall of white pumice containing clastic fragments of up to fell for several hours. It heated the roof tiles up to . This period would have been the last opportunity to escape.

The collapse of the Plinian columns on the second day caused pyroclastic density currents (PDCs) that devastated Herculaneum and Pompeii. The depositional temperature of these pyroclastic surges ranged up to . Any population remaining in structural refuges could not have escaped, as gases of incinerating temperatures surrounded the city. The lowest temperatures were in rooms under collapsed roofs. These were as low as .

The two Plinys

The only surviving eyewitness account of the event consists of two letters by Pliny the Younger to the historianTacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

. Pliny the Younger describes, amongst other things, the last days in the life of his uncle, Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

. Observing the first volcanic activity from Misenum across the Bay of Naples from the volcano, approximately , the elder Pliny launched a rescue fleet and went himself to the rescue of a personal friend. His nephew declined to join the party. One of the nephew's letters relates what he could discover from witnesses of his uncle's experiences. In a second letter, the younger Pliny details his own observations after the departure of his uncle.

The two men saw an extraordinarily dense cloud rising rapidly above the peak. This cloud and a request by a messenger for an evacuation by sea prompted the elder Pliny to order rescue operations in which he sailed away to participate. His nephew attempted to resume a normal life, but that night a tremor awoke him and his mother, prompting them to abandon the house for the courtyard. Further tremors near dawn caused the population to abandon the village and caused disastrous wave action

In fluid dynamics, a wind wave, water wave, or wind-generated water wave, is a surface wave that occurs on the free surface of bodies of water as a result from the wind blowing over the water surface. The contact distance in the direction ...

in the Bay of Naples.

A massive black cloud glistering with lighting obscured the early-morning light, a scene Pliny describes as sheet lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an avera ...

. The cloud obscured Point Misenum near at hand and the island of Capraia ( Capri) across the bay. Fearing for their lives, the population began to flee the shore along the road. An ash rain fell, causing Pliny to shake it off periodically to avoid being buried. Later that same day, the pumice and ash stopped falling, and the sun shone weakly through the cloud, encouraging Pliny and his mother to return to their home and wait for news of Pliny the Elder.

Pliny's uncle, Pliny, the Elder, was in command of the Roman fleet at Misenum and had meanwhile decided to investigate the phenomenon at close hand in a light vessel. As the ship was preparing to leave the area, a messenger came from his friend Rectina (wife of Tascius) living on the coast near the foot of the volcano, explaining that her party could only get away by sea and asking for rescue. Pliny ordered the immediate launching of the fleet galleys to the evacuation of the coast. He continued in his light ship to the rescue of Rectina's party.

He set off across the bay but, in the shallows on the other side, encountered thick showers of hot cinders, lumps of pumice and pieces of rock. Advised by the helmsman to turn back, he stated, "Fortune favors the brave" and ordered him to continue to Stabiae (about 4.5 km from Pompeii).

Pliny the Elder and his party saw what they believed to be flames coming from several parts of the crater. After staying overnight, the party was driven from the building by an accumulation of material, presumably tephra, which threatened to block all egress. They woke Pliny, who had been napping and emitting loud snoring. They elected to take to the fields with pillows tied to their heads to protect them from the raining debris. They approached the beach again, but the wind prevented the ships from leaving. Pliny sat down on a sail that had been spread for him and could not rise even with assistance when his friends departed. Though Pliny the Elder died, his friends ultimately escaped by land.

In the first letter to Tacitus, Pliny the Younger suggested that his uncle's death was due to the reaction of his weak lungs to a cloud of poisonous, sulphurous gas that wafted over the group. However, Stabiae was 16 km from the vent (roughly where the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia is situated), and his companions were unaffected by the volcanic gases. It is more likely that the corpulent Pliny died from another cause, such as a stroke or heart attack. His body was found with no apparent injuries on the next day, after dispersal of the plume.

Casualties

Later eruptions from the 3rd to the 19th centuries

Since the eruption of AD 79, Vesuvius has erupted around three dozen times. * It erupted again in 203, during the lifetime of the historianCassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

.

* In 472, it ejected such a volume of ash that ashfalls were reported as far away as Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

(760 mi.; 1,220 km).

* The eruptions of 512 were so severe that those inhabiting the slopes of Vesuvius were granted exemption from taxes by Theodoric the Great

Theodoric (or Theoderic) the Great (454 – 30 August 526), also called Theodoric the Amal ( got, , *Þiudareiks; Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ), was king of the Ostrogoths (471–526), and ruler of the independent Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy ...

, the Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

king of Italy.

* Further eruptions were recorded in 787, 968, 991, 999, 1007 and 1036 with the first recorded lava flows

Lava is molten or partially molten rock ( magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land o ...

.

The volcano became quiescent at the end of the 13th century, and in the following years, it again became covered with gardens and vineyards as old. Even the inside of the crater was moderately filled with shrubbery.

* Vesuvius entered a new phase in December 1631, when a major eruption buried many villages under lava flows, killing around 3,000 people. Torrents of lahar were also created, adding to the devastation. Activity thereafter became almost continuous, with relatively severe eruptions occurring in 1660, 1682, 1694, 1698, 1707, 1737, 1760, 1767, 1779, 1794, 1822, 1834, 1839, 1850, 1855, 1861, 1868, 1872, 1906, 1926, 1929, and 1944.

Eruptions in the 20th century

* The eruption of 5 April 1906Vesuvius Causes Terror; Loud Detonations and Frequent EarthquakesThe New York Times, 6 April 1906Vesuvius Threatens Destruction Of Towns; Bosco Trecase Abandoned

The New York Times, 7 April 1906 killed more than 100 people and ejected the most lava ever recorded from a Vesuvian eruption. Italian authorities were preparing to hold the 1908 Summer Olympics when Mount Vesuvius violently erupted, devastating the city of

Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and surrounding comunes. Funds were diverted to reconstructing Naples, and a new site for the Olympics had to be found.

* Vesuvius was active from 1913 through 1944, with lava filling the crater and occasional outflows of small amounts of lava.

* That eruptive period ended in the major eruption of March 1944, which destroyed the villages of San Sebastiano al Vesuvio, Massa di Somma, and Ottaviano, and part of San Giorgio a Cremano. From 13 to 18 March 1944, activity was confined within the rim. Finally, on 18 March 1944, lava overflowed the rim. Lava flows destroyed nearby villages from 19 March through 22 March. On 24 March, an explosive eruption created an ash plume and a small pyroclastic flow.

In March 1944, the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

(USAAF) 340th Bombardment Group

34 may refer to:

* 34 (number), the natural number following 33 and preceding 35

* one of the years 34 BC, AD 34, 1934, 2034

* ''34'' (album), a 2015 album by Dre Murray

* "#34" (song), a 1994 song by Dave Matthews Band

* "34", a 2006 song by S ...

was based at Pompeii Airfield near Terzigno, Italy, just a few kilometres from the eastern base of the volcano. The tephra and hot ash from multiple days of the eruption damaged the fabric control surfaces, the engines, the Plexiglas

Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) belongs to a group of materials called engineering plastics. It is a transparent thermoplastic. PMMA is also known as acrylic, acrylic glass, as well as by the trade names and brands Crylux, Plexiglas, Acryli ...

windscreens and the gun turrets of the 340th's B-25 Mitchell

The North American B-25 Mitchell is an American medium bomber that was introduced in 1941 and named in honor of Major General William "Billy" Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation. Used by many Allied air forces, the B-25 served in ...

medium bombers. Estimates ranged from 78 to 88 aircraft destroyed.

The eruption could be seen from Naples. Different perspectives and the damage caused to the local villages were recorded by USAAF photographers and other personnel based nearer to the volcano.

The eruption could be seen from Naples. Different perspectives and the damage caused to the local villages were recorded by USAAF photographers and other personnel based nearer to the volcano.

Future

Large Vesuvian eruptions which emit volcanic material in quantities of about , the most recent of which overwhelmed Pompeii and Herculaneum, have happened after periods of inactivity of a few thousand years. Sub-Plinian eruptions producing about , such as those of 472 and 1631, have been more frequent with a few hundred years between them. From the 1631 eruption until 1944, there was a comparatively small eruption every few years, emitting 0.001–0.01 km³ of magma. For Vesuvius, the amount of magma expelled in an eruption increases roughly linearly with the interval since the previous one, and at a rate of around for each year. This gives an approximate figure of for an eruption after 75 years of inactivity. Magma sitting in an underground chamber for many years will start to see higher melting point constituents such asolivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers qui ...

crystallizing out. The effect is to increase the concentration of dissolved gases (mostly sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide ( IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a toxic gas responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic ...

and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

) in the remaining liquid magma, making the subsequent eruption more violent. As gas-rich magma approaches the surface during an eruption, the huge drop in internal pressure caused by the reduction in weight of the overlying rock (which drops to zero at the surface) causes the gases to come out of solution, the volume of gas increasing explosively from nothing to perhaps many times that of the accompanying magma. Additionally, the removal of the higher melting point material will raise the concentration of felsic components such as silicates, potentially making the magma more viscous, adding to the explosive nature of the eruption.

The government emergency plan for an eruption therefore assumes that the worst case will be an eruption of similar size and type to the 1631 VEI 4 eruption. In this scenario, the volcano's slopes, extending out to about from the vent, may be exposed to pyroclastic surges sweeping down them, whilst much of the surrounding area could suffer from tephra falls. Because of prevailing winds, towns and cities south and east of the volcano are most at risk from this. It is assumed that tephra accumulation exceeding —at which point people are at risk from collapsing roofs—may extend out as far as Avellino to the east or

The government emergency plan for an eruption therefore assumes that the worst case will be an eruption of similar size and type to the 1631 VEI 4 eruption. In this scenario, the volcano's slopes, extending out to about from the vent, may be exposed to pyroclastic surges sweeping down them, whilst much of the surrounding area could suffer from tephra falls. Because of prevailing winds, towns and cities south and east of the volcano are most at risk from this. It is assumed that tephra accumulation exceeding —at which point people are at risk from collapsing roofs—may extend out as far as Avellino to the east or Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

to the south-east. Near Naples, this tephra fall hazard is assumed to extend barely past the volcano's slopes to the northwest. The specific areas affected by the ash cloud depend upon the circumstances surrounding the eruption.

The plan assumes between two weeks and 20 days notice of an eruption and foresees the emergency evacuation of 600,000 people, almost entirely comprising all those living in the '' zona rossa'' ("red zone"), i.e. at greatest risk from pyroclastic flows. The evacuation, by train, ferry, car, and bus, is planned to take about seven days, and the evacuees would mostly be sent to other parts of the country, rather than to safe areas in the local Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

region, and may have to stay away for several months. However, the dilemma that would face those implementing the plan is when to start this massive evacuation: If it starts too late, thousands could be killed, whereas if it is started too early, the indicators of an eruption may turn out to be a false alarm. In 1984, 40,000 people were evacuated from the Campi Flegrei area, another volcanic complex near Naples, but no eruption occurred.

Ongoing efforts are being made by the government at various levels (especially of

Ongoing efforts are being made by the government at various levels (especially of Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

) to reduce the population living in the red zone, by demolishing illegally constructed buildings, establishing a national park around the whole volcano to prevent the future construction of buildings and by offering sufficient financial incentives to people for moving away. One of the underlying goals is to reduce the time needed to evacuate the area, over the next twenty to thirty years, to two or three days.

The volcano is closely monitored by the Osservatorio Vesuvio in Naples with extensive networks of seismic and gravimetric stations, a combination of a GPS-based geodetic array and satellite

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioiso ...

-based synthetic aperture radar to measure ground movement and by local surveys and chemical analyses of gases emitted from fumaroles. All of this is intended to track magma rising underneath the volcano. , no magma has been detected within 10 km of the surface, so the volcano is classified by the Observatory as at a Basic or Green Level of hazard.

National park

The area around Vesuvius was officially declared a national park on 5 June 1995. The summit of Vesuvius is open to visitors, and there is a small network of paths around the volcano that are maintained by the park authorities on weekends. There is access by road to within of the summit (measured vertically), but after that, access is on foot only. There is a spiral walkway around the volcano from the road to the crater.Funicular

Mount Vesuvius' firstfunicular

A funicular (, , ) is a type of cable railway system that connects points along a railway track laid on a steep slope. The system is characterized by two counterbalanced carriages (also called cars or trains) permanently attached to opposite e ...

— a type of vertical transport that uses two opposing, interconnected, rail-guided passenger cars always moving in concert — opened in 1880, subsequently destroyed by the March 1944 eruption.

"Funiculì, Funiculà

"Funiculì, Funiculà" (, en, "Funicular Up, Funicular Down") is a Neapolitan song composed in 1880 by Luigi Denza to lyrics by Peppino Turco. It was written to commemorate the opening of the first funicular railway on Mount Vesuvius. It was pr ...

", a Neapolitan language song, was written to commemorate the opening of the first funicular on Mount Vesuvius.

See also

* Battle of Mount Vesuvius * List of volcanic eruptions by death toll *List of volcanoes in Italy

This is a list of active and extinct volcanoes in Italy.

See also

*Volcanology of Italy

*List of mountains of Italy

Notes

References

Global Volcanism Program

{{DEFAULTSORT:List Of Volcanoes In Italy

Italy

Volcanoes

A volcano is a ...

* List of stratovolcanoes

A list of stratovolcanoes follows below.

Africa

Cameroon

* Mount Cameroon

Democratic Republic of Congo

* Mount Nyiragongo, Goma; designated as a Decade Volcano

** It contains an active lava lake inside its crater which overflowed due to ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * *External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Vesuvius, Mount Active volcanoes Campanian volcanic arc Complex volcanoes Decade Volcanoes Geography of Naples Sacred mountains Stratovolcanoes of Italy Subduction volcanoes VEI-6 volcanoes Parks in Campania 20th-century volcanic events 19th-century volcanic events 18th-century volcanic events 17th-century volcanic events 16th-century volcanic events Medieval volcanic events Pompeii (ancient city) Geological type localities Tourist attractions in Campania Articles containing video clips