Mount St Helens on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mount St. Helens (known as Lawetlat'la to the indigenous

Mount St. Helens is west of Mount Adams, in the western part of the Cascade Range. Considered "brother and sister" mountains, the two volcanoes are approximately from

Mount St. Helens is west of Mount Adams, in the western part of the Cascade Range. Considered "brother and sister" mountains, the two volcanoes are approximately from

Mount St. Helens is part of the Cascades Volcanic Province, an arc-shaped band extending from southwestern

Mount St. Helens is part of the Cascades Volcanic Province, an arc-shaped band extending from southwestern

Roughly 700 years of dormancy were broken in about 1480, when large amounts of pale gray dacite pumice and ash started to erupt, beginning the Kalama period. The 1480 eruption was several times larger than that of May 18, 1980. In 1482, another large eruption rivaling the 1980 eruption in volume is known to have occurred. Ash and pumice piled northeast of the volcano to a thickness of ; away, the ash was deep. Large pyroclastic flows and mudflows subsequently rushed down St. Helens' west flanks and into the Kalama River drainage system.

This 150-year period next saw the eruption of less

Roughly 700 years of dormancy were broken in about 1480, when large amounts of pale gray dacite pumice and ash started to erupt, beginning the Kalama period. The 1480 eruption was several times larger than that of May 18, 1980. In 1482, another large eruption rivaling the 1980 eruption in volume is known to have occurred. Ash and pumice piled northeast of the volcano to a thickness of ; away, the ash was deep. Large pyroclastic flows and mudflows subsequently rushed down St. Helens' west flanks and into the Kalama River drainage system.

This 150-year period next saw the eruption of less

In its undisturbed state, the slopes of Mount St. Helens lie in the Western Cascades Montane Highlands ecoregion. This ecoregion has abundant precipitation; an average of of precipitation falls each year at Spirit Lake. This precipitation supported dense forest up to , with

In its undisturbed state, the slopes of Mount St. Helens lie in the Western Cascades Montane Highlands ecoregion. This ecoregion has abundant precipitation; an average of of precipitation falls each year at Spirit Lake. This precipitation supported dense forest up to , with

The first authenticated non-Indigenous eyewitness report of a volcanic eruption was made in March 1835 by

The first authenticated non-Indigenous eyewitness report of a volcanic eruption was made in March 1835 by

Fifty-seven people were killed during the eruption. Had the eruption occurred one day later, when loggers would have been at work, rather than on a Sunday, the death toll could have been much higher.

Eighty-three-year-old

Fifty-seven people were killed during the eruption. Had the eruption occurred one day later, when loggers would have been at work, rather than on a Sunday, the death toll could have been much higher.

Eighty-three-year-old

In 1982, President

In 1982, President

Cowlitz people

The term Cowlitz people covers two culturally and linguistically distinct indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest; the Lower Cowlitz or Cowlitz proper, and the Upper Cowlitz / Cowlitz Klickitat or Taitnapam. Lower Cowlitz refers to a southwe ...

, and Loowit or Louwala-Clough to the Klickitat) is an active stratovolcano

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a conical volcano built up by many layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile with a summit crater and per ...

located in Skamania County, Washington

Skamania County () is a county located in the U.S. state of Washington. As of the 2020 census, the population was 12,036. The county seat and largest incorporated city is Stevenson, although the Carson River Valley CDP is more populous. The ...

, in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

region of the United States. It lies northeast of Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous co ...

, and south of Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

. Mount St. Helens takes its English name from that of the British diplomat Lord St Helens, a friend of explorer George Vancouver

Captain George Vancouver (22 June 1757 – 10 May 1798) was a British Royal Navy officer best known for his 1791–1795 expedition, which explored and charted North America's northwestern Pacific Coast regions, including the coasts of what a ...

who surveyed the area in the late 18th century. The volcano is part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc

The Cascade Volcanoes (also known as the Cascade Volcanic Arc or the Cascade Arc) are a number of volcanoes in a volcanic arc in western North America, extending from southwestern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern Califo ...

, a segment of the Pacific Ring of Fire

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt) is a region around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean where many Types of volcanic eruptions, volcanic eruptions and ...

.

The Mount St. Helens major eruption of May 18, 1980 remains the deadliest and most economically destructive volcanic event in U.S. history. Fifty-seven people were killed; 200 homes, 47 bridges, of railways, and of highway were destroyed. A massive debris avalanche

Debris flows are geological phenomena in which water-laden masses of soil and fragmented rock rush down mountainsides, funnel into stream channels, entrain objects in their paths, and form thick, muddy deposits on valley floors. They generally ...

, triggered by a magnitude

Magnitude may refer to:

Mathematics

*Euclidean vector, a quantity defined by both its magnitude and its direction

*Magnitude (mathematics), the relative size of an object

*Norm (mathematics), a term for the size or length of a vector

*Order of ...

5.1 earthquake, caused a lateral eruption

A lateral eruption or lateral blast is a volcanic eruption which is directed laterally from a volcano rather than upwards from the summit. Lateral eruptions are caused by the outward expansion of flanks due to rising magma. Breaking occurs at the ...

that reduced the elevation of the mountain's summit from to , leaving a wide horseshoe-shaped crater. The debris avalanche was in volume. The 1980 eruption disrupted terrestrial ecosystems near the volcano. By contrast, aquatic ecosystems in the area greatly benefited from the amounts of ash, allowing life to multiply rapidly. Six years after the eruption, most lakes in the area had returned to their normal state.

After its 1980 eruption, the volcano experienced continuous volcanic activity until 2008. Geologists predict that future eruptions will be more destructive, as the configuration of the lava domes require more pressure to erupt. However, Mount St. Helens is a popular hiking spot and it is climbed year-round. In 1982, the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument

Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument is a U.S. National Monument that includes the area around Mount St. Helens in Washington. It was established on August 27, 1982, by U.S. President Ronald Reagan, following the 1980 eruption. The 110,0 ...

was established by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

and the U.S. Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

.

Geographic setting and description

General

Mount St. Helens is west of Mount Adams, in the western part of the Cascade Range. Considered "brother and sister" mountains, the two volcanoes are approximately from

Mount St. Helens is west of Mount Adams, in the western part of the Cascade Range. Considered "brother and sister" mountains, the two volcanoes are approximately from Mount Rainier

Mount Rainier (), indigenously known as Tahoma, Tacoma, Tacobet, or təqʷubəʔ, is a large active stratovolcano in the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest, located in Mount Rainier National Park about south-southeast of Seattle. With a s ...

, the highest of the Cascade volcanoes. Mount Hood

Mount Hood is a potentially active stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc. It was formed by a subduction zone on the Pacific coast and rests in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located about east-southeast of Portlan ...

, the nearest major volcanic peak in Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, is southeast of Mount St. Helens.

Mount St. Helens is geologically young compared with the other major Cascade volcanoes. It formed only within the past 40,000 years, and the summit cone present before its 1980 eruption began rising about 2,200 years ago. The volcano is considered the most active in the Cascades within the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togethe ...

epoch, which encompasses roughly the last 10,000 years.

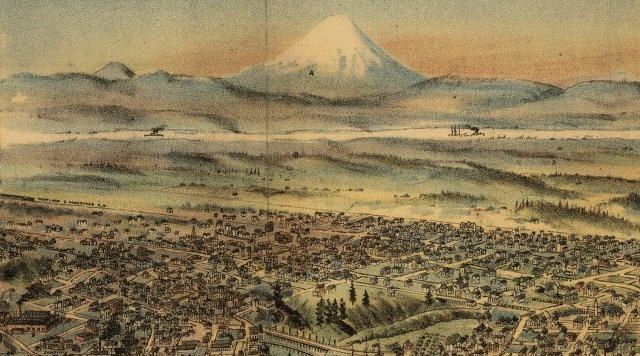

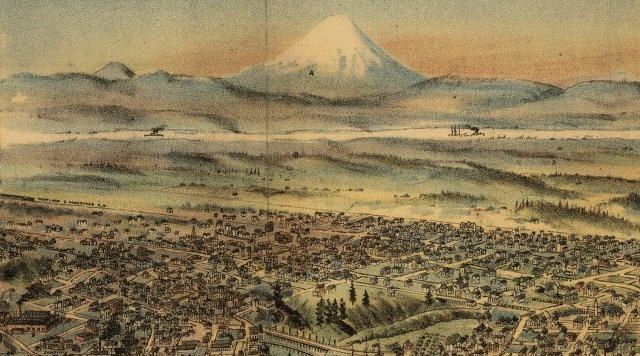

Prior to the 1980 eruption, Mount St. Helens was the fifth-highest peak in Washington. It stood out prominently from surrounding hills because of the symmetry and extensive snow and ice cover of the pre-1980 summit cone, earning it the nickname, by some, " Fuji-san of America". The peak rose more than above its base, where the lower flanks merge with adjacent ridges. The mountain is across at its base, which is at an elevation of on the northeastern side and elsewhere. At the pre-eruption tree line

The tree line is the edge of the habitat at which trees are capable of growing. It is found at high elevations and high latitudes. Beyond the tree line, trees cannot tolerate the environmental conditions (usually cold temperatures, extreme snowp ...

, the width of the cone was .

Stream

A stream is a continuous body of water, body of surface water Current (stream), flowing within the stream bed, bed and bank (geography), banks of a channel (geography), channel. Depending on its location or certain characteristics, a stream ...

s that originate on the volcano enter three main river systems: The Toutle River

The Toutle River is a tributary of the Cowlitz River in the U.S. state of Washington. It rises in two forks merging near Toutle below Mount St. Helens and joins the Cowlitz near Castle Rock, upstream of the larger river's confluence with the Co ...

on the north and northwest, the Kalama River

The Kalama River is a tributary of the Columbia River, in the U.S. state of Washington. It flows entirely within Cowlitz County, Washington. Calama River is an old variant name.

Gabriel Franchere in 1811 wrote of the Indian village at the mouth ...

on the west, and the Lewis River on the south and east. The streams are fed by abundant rain and snow. The average annual rainfall is , and the snowpack on the mountain's upper slopes can reach . The Lewis River is impounded by three dam

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use ...

s for hydroelectric power

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and ...

generation. The southern and eastern sides of the volcano drain into an upstream impoundment, the Swift Reservoir

Swift Reservoir is a reservoir on the Lewis River in the U.S. state of Washington. It is located in Skamania County. It was created in 1958 with the construction of Swift Dam.

See also

*List of lakes in Washington (state)

*List of dams in the C ...

, which is directly south of the volcano's peak.

Although Mount St. Helens is in Skamania County, Washington, access routes to the mountain run through Cowlitz County to the west, and Lewis County to the north. State Route 504, locally known as the Spirit Lake Memorial Highway

Spirit or spirits may refer to:

Liquor and other volatile liquids

* Spirits, a.k.a. liquor, distilled alcoholic drinks

* Spirit or tincture, an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol

* Volatile (especially flammable) liquids ...

, connects with Interstate 5 at Exit 49, to the west of the mountain. That north–south highway skirts the low-lying cities of Castle Rock, Longview and Kelso along the Cowlitz River

The Cowlitz River is a river in the state of Washington in the United States, a tributary of the Columbia River. Its tributaries drain a large region including the slopes of Mount Rainier, Mount Adams, and Mount St. Helens.

The Cowlitz has a ...

, and passes through the Vancouver, Washington

Vancouver is a city on the north bank of the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Washington, located in Clark County. Incorporated in 1857, Vancouver has a population of 190,915 as of the 2020 census, making it the fourth-largest city in Was ...

–Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous co ...

metropolitan area

A metropolitan area or metro is a region that consists of a densely populated urban agglomeration and its surrounding territories sharing industries, commercial areas, transport network, infrastructures and housing. A metro area usually com ...

less than to the southwest. The community nearest the volcano is Cougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') is a large Felidae, cat native to the Americas. Its Species distribution, range spans from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes in South America and is the most widespread of any large wild terrestrial mamm ...

, Washington, in the Lewis River valley south-southwest of the peak. Gifford Pinchot National Forest

Gifford Pinchot National Forest is a National Forest located in southern Washington, managed by the United States Forest Service. With an area of 1.32 million acres (5300 km2), it extends 116 km along the western slopes of Cascade Ran ...

surrounds Mount St. Helens.

Crater Glacier and other new rock glaciers

During the winter of 1980–1981, a newglacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

appeared. Now officially named Crater Glacier

The Crater Glacier (also known as Tulutson Glacier) is a geologically young glacier that is located on Mount St. Helens, in the U.S. state of Washington. The glacier formed after the 1980 Eruption and due to its location, the body of ice grew ra ...

, it was formerly known as the Tulutson Glacier. Shadowed by the crater walls and fed by heavy snowfall and repeated snow avalanches, it grew rapidly ( per year in thickness). By 2004, it covered about , and was divided by the dome into a western and eastern lobe. Typically, by late summer, the glacier looks dark from rockfall from the crater walls and ash from eruptions. As of 2006, the ice had an average thickness of and a maximum of , nearly as deep as the much older and larger Carbon Glacier

Carbon Glacier is located on the north slope of Mount Rainier in the U.S. state of Washington and is the source of the Carbon River. The snout at the glacier terminal moraine is at about above sea level, making it the lowest-elevation glacier in ...

of Mount Rainier. The ice is all post-1980, making the glacier very young geologically. However, the volume of the new glacier is about the same as all the pre-1980 glaciers combined.

From 2004, volcanic activity pushed aside the glacier lobes and upward by the growth of new volcanic domes. The surface of the glacier, once mostly without crevasses, turned into a chaotic jumble of icefall

An icefall is a portion of certain glaciers characterized by relatively rapid flow and chaotic crevassed surface, caused in part by gravity. The term ''icefall'' is formed by analogy with the word ''waterfall'', which is a similar phenomenon of t ...

s heavily criss-crossed with crevasse

A crevasse is a deep crack, that forms in a glacier or ice sheet that can be a few inches across to over 40 feet. Crevasses form as a result of the movement and resulting stress associated with the shear stress generated when two semi-rigid pie ...

s and serac

A serac (from Swiss French ''sérac'') is a block or column of glacial ice, often formed by intersecting crevasses on a glacier. Commonly house-sized or larger, they are dangerous to mountaineers, since they may topple with little warning. Even ...

s caused by movement of the crater floor. The new domes have almost separated the Crater Glacier into an eastern and western lobe. Despite the volcanic activity, the termini of the glacier have still advanced, with a slight advance on the western lobe and a more considerable advance on the more shaded eastern lobe. Due to the advance, two lobes of the glacier joined in late May 2008 and thus the glacier completely surrounds the lava domes. – Glacier is still connected south of the lava dome. – Glacier arms touch on North end of glacier. In addition, since 2004, new glaciers have formed on the crater wall above Crater Glacier feeding rock and ice onto its surface below; there are two rock glaciers to the north of the eastern lobe of Crater Glacier.

Climate

Geology

British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

to Northern California

Northern California (colloquially known as NorCal) is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the northern portion of the U.S. state of California. Spanning the state's northernmost 48 counties, its main population centers incl ...

, roughly parallel to the Pacific coastline. Beneath the Cascade Volcanic Province, a dense oceanic plate sinks beneath the North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Pacific ...

; a process known as subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

in geology. As the oceanic slab sinks deeper into the Earth's interior beneath the continental plate, high temperatures and pressures allow water molecules locked in the minerals of solid rock to escape. The water vapor rises into the pliable mantle above the subducting plate, causing some of the mantle to melt. This newly formed magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

ascends upward through the crust along a path of least resistance, both by way of fractures and faults as well as by melting wall rocks. The addition of melted crust changes the geochemical

Geochemistry is the science that uses the tools and principles of chemistry to explain the mechanisms behind major geological systems such as the Earth's crust and its oceans. The realm of geochemistry extends beyond the Earth, encompassing the e ...

composition. Some of the melt rises toward the Earth's surface to erupt, forming the Cascade Volcanic Arc

The Cascade Volcanoes (also known as the Cascade Volcanic Arc or the Cascade Arc) are a number of volcanoes in a volcanic arc in western North America, extending from southwestern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern Califo ...

above the subduction zone.

The magma from the mantle has accumulated in two chambers below the volcano: one approximately below the surface, the other about . The lower chamber may be shared with Mount Adams and the Indian Heaven

Indian Heaven is a volcanic field in Skamania County in the state of Washington, in the United States. Midway between Mount St. Helens and Mount Adams, the field dates from the Pleistocene to the early Holocene epoch. It trends north to south ...

volcanic field.

Ancestral stages of eruptive activity

The early eruptive stages of Mount St. Helens are known as the "Ape Canyon Stage" (around 40,000–35,000 years ago), the "Cougar Stage" (ca. 20,000–18,000 years ago), and the "Swift Creek Stage" (roughly 13,000–8,000 years ago). The modern period, since about 2500 BC, is called the "Spirit Lake Stage". Collectively, the pre–Spirit Lake stages are known as the "ancestral stages". The ancestral and modern stages differ primarily in the composition of the erupted lavas; ancestral lavas consisted of a characteristic mixture ofdacite

Dacite () is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyolite. ...

and andesite

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predomi ...

, while modern lava is very diverse (ranging from olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers quickl ...

basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

to andesite and dacite).

St. Helens started its growth in the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

37,600 years ago, during the Ape Canyon stage, with dacite and andesite eruptions of hot pumice and ash. Thirty-six thousand years ago a large mudflow

A mudflow or mud flow is a form of mass wasting involving fast-moving flow of debris that has become liquified by the addition of water. Such flows can move at speeds ranging from 3 meters/minute to 5 meters/second. Mudflows contain a significa ...

cascaded down the volcano; mudflows were significant forces in all of St. Helens' eruptive cycles. The Ape Canyon eruptive period ended around 35,000 years ago and was followed by 17,000 years of relative quiet. Parts of this ancestral cone were fragmented and transported by glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s 14,000–18,000 years ago during the last glacial period of the current ice age

The Late Cenozoic Ice Age,National Academy of Sciences - The National Academies Press - Continental Glaciation through Geologic Times https://www.nap.edu/read/11798/chapter/8#80 or Antarctic Glaciation began 33.9 million years ago at the Eocen ...

.

The second eruptive period, the Cougar Stage, started 20,000 years ago and lasted for 2,000 years. Pyroclastic flow

A pyroclastic flow (also known as a pyroclastic density current or a pyroclastic cloud) is a fast-moving current of hot gas and volcanic matter (collectively known as tephra) that flows along the ground away from a volcano at average speeds of bu ...

s of hot pumice and ash along with dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

growth occurred during this period. Another 5,000 years of dormancy followed, only to be upset by the beginning of the Swift Creek eruptive period, typified by pyroclastic flows, dome growth and blanketing of the countryside with tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, they rem ...

. Swift Creek ended 8,000 years ago.

Smith Creek and Pine Creek eruptive periods

A dormancy of about 4,000 years was broken around 2500 BC with the start of the Smith Creek eruptive period, when eruptions of large amounts of ash and yellowish-brown pumice covered thousands of square miles. An eruption in 1900 BC was the largest known eruption from St. Helens during theHolocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togethe ...

epoch, depositing the Yn tephra. This eruptive period lasted until about 1600 BC and left deep deposits of material distant in what is now Mount Rainier National Park

Mount Rainier National Park is an American national park located in southeast Pierce County and northeast Lewis County in Washington state. The park was established on March 2, 1899, as the fourth national park in the United States, preservi ...

. Trace deposits have been found as far northeast as Banff National Park

Banff National Park is Canada's oldest National Parks of Canada, national park, established in 1885 as Rocky Mountains Park. Located in Alberta's Rockies, Alberta's Rocky Mountains, west of Calgary, Banff encompasses of mountainous terrain, wi ...

in Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

, and as far southeast as eastern Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

. All told there may have been up to of material ejected in this cycle. Some 400 years of dormancy followed.

St. Helens came alive again around 1200 BC — the Pine Creek eruptive period. This lasted until about 800 BC and was characterized by smaller-volume eruptions. Numerous dense, nearly red hot pyroclastic flows sped down St. Helens' flanks and came to rest in nearby valleys. A large mudflow partly filled of the Lewis River valley sometime between 1000 BC and 500 BC.

Castle Creek and Sugar Bowl eruptive periods

The next eruptive period, the Castle Creek period, began about 400 BC, and is characterized by a change in the composition of St. Helens' lava, with the addition ofolivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers quickl ...

and basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

. The pre-1980 summit cone started to form during the Castle Creek period. Significant lava flows in addition to the previously much more common fragmented and pulverized lavas and rocks (tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, they rem ...

) distinguished this period. Large lava flows of andesite and basalt covered parts of the mountain, including one around the year 100 BC that traveled all the way into the Lewis and Kalama river valleys. Others, such as Cave Basalt (known for its system of lava tube

A lava tube, or pyroduct, is a natural conduit formed by flowing lava from a volcanic vent that moves beneath the hardened surface of a lava flow. If lava in the tube empties, it will leave a cave.

Formation

A lava tube is a type of lava ca ...

s), flowed up to from their vents. During the first century, mudflows moved down the Toutle and Kalama river valleys and may have reached the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

. Another 400 years of dormancy

Dormancy is a period in an organism's life cycle when growth, development, and (in animals) physical activity are temporarily stopped. This minimizes metabolic activity and therefore helps an organism to conserve energy. Dormancy tends to be clo ...

ensued.

The Sugar Bowl eruptive period was short and markedly different from other periods in Mount St. Helens history. It produced the only unequivocal laterally directed blast known from Mount St. Helens before the 1980 eruptions. During Sugar Bowl time, the volcano first erupted quietly to produce a dome, then erupted violently at least twice producing a small volume of tephra, directed-blast deposits, pyroclastic flows, and lahars.

Kalama and Goat Rocks eruptive periods

Roughly 700 years of dormancy were broken in about 1480, when large amounts of pale gray dacite pumice and ash started to erupt, beginning the Kalama period. The 1480 eruption was several times larger than that of May 18, 1980. In 1482, another large eruption rivaling the 1980 eruption in volume is known to have occurred. Ash and pumice piled northeast of the volcano to a thickness of ; away, the ash was deep. Large pyroclastic flows and mudflows subsequently rushed down St. Helens' west flanks and into the Kalama River drainage system.

This 150-year period next saw the eruption of less

Roughly 700 years of dormancy were broken in about 1480, when large amounts of pale gray dacite pumice and ash started to erupt, beginning the Kalama period. The 1480 eruption was several times larger than that of May 18, 1980. In 1482, another large eruption rivaling the 1980 eruption in volume is known to have occurred. Ash and pumice piled northeast of the volcano to a thickness of ; away, the ash was deep. Large pyroclastic flows and mudflows subsequently rushed down St. Helens' west flanks and into the Kalama River drainage system.

This 150-year period next saw the eruption of less silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

-rich lava in the form of andesitic

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predomina ...

ash that formed at least eight alternating light- and dark-colored layers. Blocky andesite lava then flowed from St. Helens' summit crater down the volcano's southeast flank. Later, pyroclastic flows raced down over the andesite lava and into the Kalama River valley. It ended with the emplacement of a dacite dome several hundred feet (~200 m) high at the volcano's summit, which filled and overtopped an explosion crater already at the summit. Large parts of the dome's sides broke away and mantled parts of the volcano's cone with talus. Lateral explosions excavated a notch in the southeast crater wall. St. Helens reached its greatest height and achieved its highly symmetrical form by the time the Kalama eruptive cycle ended, in about 1647. The volcano remained quiet for the next 150 years.

The 57-year eruptive period that started in 1800 was named after the Goat Rocks dome and is the first period for which both oral and written records exist. As with the Kalama period, the Goat Rocks period started with an explosion of dacite

Dacite () is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyolite. ...

tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, they rem ...

, followed by an andesite lava flow, and culminated with the emplacement of a dacite dome. The 1800 eruption probably rivaled the 1980 eruption in size, although it did not result in massive destruction of the cone. The ash drifted northeast over central and eastern Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, northern Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

, and western Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

. There were at least a dozen reported small eruptions of ash from 1831 to 1857, including a fairly large one in 1842. (The 1831 eruption is likely what tinted the sun bluish-green in Southampton County, Virginia

Southampton County is a county located on the southern border of the Commonwealth of Virginia. North Carolina is to the south. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,996. Its county seat is Courtland.

History

In the early 17th century ...

on the afternoon of August 13 — which Nat Turner

Nat Turner's Rebellion, historically known as the Southampton Insurrection, was a rebellion of enslaved Virginians that took place in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831.Schwarz, Frederic D.1831 Nat Turner's Rebellion" ''American Heri ...

interpreted as a final signal to launch the United States' largest slave rebellion.) The vent was apparently at or near Goat Rocks on the northeast flank. Goat Rocks dome was the site of the bulge in the 1980 eruption, and it was obliterated in the major eruption event on May 18, 1980, that destroyed the entire north face and top of the mountain.

Modern eruptive period

1980 to 2001 activity

On March 20, 1980, Mount St. Helens experienced amagnitude

Magnitude may refer to:

Mathematics

*Euclidean vector, a quantity defined by both its magnitude and its direction

*Magnitude (mathematics), the relative size of an object

*Norm (mathematics), a term for the size or length of a vector

*Order of ...

4.2 earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

, and on March 27, steam venting started. By the end of April, the north side of the mountain had started to bulge.

On May 18, a second earthquake, of magnitude 5.1, triggered a massive collapse of the north face of the mountain. It was the largest known debris avalanche

Debris flows are geological phenomena in which water-laden masses of soil and fragmented rock rush down mountainsides, funnel into stream channels, entrain objects in their paths, and form thick, muddy deposits on valley floors. They generally ...

in recorded history. The magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

in St. Helens burst forth into a large-scale pyroclastic flow

A pyroclastic flow (also known as a pyroclastic density current or a pyroclastic cloud) is a fast-moving current of hot gas and volcanic matter (collectively known as tephra) that flows along the ground away from a volcano at average speeds of bu ...

that flattened vegetation and buildings over an area of . More than 1.5 million metric tons of sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a toxic gas responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic activ ...

were released into the atmosphere. On the Volcanic Explosivity Index scale, the eruption was rated a 5, and categorized as a Plinian eruption.

The collapse of the northern flank of St. Helens mixed with ice, snow, and water to create lahar

A lahar (, from jv, ꦮ꧀ꦭꦲꦂ) is a violent type of mudflow or debris flow composed of a slurry of pyroclastic material, rocky debris and water. The material flows down from a volcano, typically along a river valley.

Lahars are extreme ...

s (volcanic mudflows). The lahars flowed many miles down the Toutle and Cowlitz River

The Cowlitz River is a river in the state of Washington in the United States, a tributary of the Columbia River. Its tributaries drain a large region including the slopes of Mount Rainier, Mount Adams, and Mount St. Helens.

The Cowlitz has a ...

s, destroying bridges and lumber camp

A logging camp (or lumber camp) is a transitory work site used in the logging industry. Before the second half of the 20th century, these camps were the primary place where lumberjacks would live and work to fell trees in a particular area. Many ...

s. A total of of material was transported south into the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

by the mudflows.

For more than nine hours, a vigorous plume of ash erupted, eventually reaching 12 to 16 miles (20 to 27 km) above sea level. The plume moved eastward at an average speed of with ash reaching Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

by noon. Ashes from the eruption were found on top of cars and roofs the next morning as far away as Edmonton

Edmonton ( ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Alberta. Edmonton is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Alberta's central region. The city ancho ...

, Alberta, Canada.

By about 5:30 p.m. on May 18, the vertical ash column declined in stature, and less-severe outbursts continued through the night and for the next several days. The St. Helens May 18 eruption released 24 megatons of thermal energy and ejected more than of material. The removal of the north side of the mountain reduced St. Helens' height by about and left a crater to wide and deep, with its north end open in a huge breach. The eruption killed 57 people, nearly 7,000 big-game animals (deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the reindeer ...

, elk

The elk (''Cervus canadensis''), also known as the wapiti, is one of the largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. The common ...

, and bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family Ursidae. They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats throughout the Nor ...

), and an estimated 12 million fish from a hatchery. It destroyed or extensively damaged more than 200 homes, of highway

A highway is any public or private road or other public way on land. It is used for major roads, but also includes other public roads and public tracks. In some areas of the United States, it is used as an equivalent term to controlled-access ...

, and of railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

s.

Between 1980 and 1986, activity continued at Mount St. Helens, with a new lava dome

In volcanology, a lava dome is a circular mound-shaped protrusion resulting from the slow extrusion of viscous lava from a volcano. Dome-building eruptions are common, particularly in convergent plate boundary settings. Around 6% of eruptions on ...

forming in the crater. Numerous small explosions and dome-building eruptions occurred. From December 7, 1989, to January 6, 1990, and from November 5, 1990, to February 14, 1991, the mountain erupted, sometimes huge clouds of ash.

2004 to 2008 activity

Magma reached the surface of the volcano about October 11, 2004, resulting in the building of a new lava dome on the existing dome's south side. This new dome continued to grow throughout 2005 and into 2006. Several transient features were observed, such as a lava spine nicknamed the "whaleback", which comprised long shafts of solidified magma being extruded by the pressure of magma beneath. These features were fragile and broke down soon after they were formed. On July 2, 2005, the tip of the whaleback broke off, causing a rockfall that sent ash and dust several hundred meters into the air. Mount St. Helens showed significant activity on March 8, 2005, when a plume of steam and ash emerged — visible fromSeattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

. This relatively minor eruption was a release of pressure consistent with ongoing dome building. The release was accompanied by a magnitude 2.5 earthquake.

Another feature to emerge from the dome was called the "fin" or "slab". Approximately half the size of a football field, the large, cooled volcanic rock was being forced upward as quickly as per day. In mid-June 2006, the slab was crumbling in frequent rockfalls, although it was still being extruded. The height of the dome was , still below the height reached in July 2005 when the whaleback collapsed.

On October 22, 2006, at 3:13 p.m. PST, a magnitude 3.5 earthquake broke loose Spine 7. The collapse and avalanche of the lava dome sent an ash plume over the western rim of the crater; the ash plume then rapidly dissipated.

On December 19, 2006, a large white plume of condensing steam was observed, leading some media people to assume there had been a small eruption. However, the Cascades Volcano Observatory

The David A. Johnston Cascades Volcano Observatory (CVO) is a volcano observatory in the US that monitors volcanoes in the northern Cascade Range. It was established in the summer of 1980, after the eruption of Mount St. Helens.lahar

A lahar (, from jv, ꦮ꧀ꦭꦲꦂ) is a violent type of mudflow or debris flow composed of a slurry of pyroclastic material, rocky debris and water. The material flows down from a volcano, typically along a river valley.

Lahars are extreme ...

flow is likely on branches of the Toutle River

The Toutle River is a tributary of the Cowlitz River in the U.S. state of Washington. It rises in two forks merging near Toutle below Mount St. Helens and joins the Cowlitz near Castle Rock, upstream of the larger river's confluence with the Co ...

, possibly causing destruction in inhabited areas along the I-5

Interstate 5 (I-5) is the main north–south Interstate Highway on the West Coast of the United States, running largely parallel to the Pacific coast of the contiguous U.S. from Mexico to Canada. It travels through the states of Californi ...

corridor.

Ecology

In its undisturbed state, the slopes of Mount St. Helens lie in the Western Cascades Montane Highlands ecoregion. This ecoregion has abundant precipitation; an average of of precipitation falls each year at Spirit Lake. This precipitation supported dense forest up to , with

In its undisturbed state, the slopes of Mount St. Helens lie in the Western Cascades Montane Highlands ecoregion. This ecoregion has abundant precipitation; an average of of precipitation falls each year at Spirit Lake. This precipitation supported dense forest up to , with western hemlock

''Tsuga heterophylla'', the western hemlock or western hemlock-spruce, is a species of hemlock native to the west coast of North America, with its northwestern limit on the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska, and its southeastern limit in northern Sonoma ...

, Douglas fir

The Douglas fir (''Pseudotsuga menziesii'') is an evergreen conifer species in the pine family, Pinaceae. It is native to western North America and is also known as Douglas-fir, Douglas spruce, Oregon pine, and Columbian pine. There are three va ...

, and western redcedar

''Thuja plicata'' is an evergreen coniferous tree in the cypress family Cupressaceae, native to western North America. Its common name is western redcedar (western red cedar in the UK), and it is also called Pacific redcedar, giant arborvitae, w ...

. Above this, this forest was dominated by Pacific silver fir

''Abies amabilis'', commonly known as the Pacific silver fir, is a fir native to the Pacific Northwest of North America, occurring in the Pacific Coast Ranges and the Cascade Range. It is also commonly referred to as the white fir, red fir, lov ...

up to . Finally, below treeline

The tree line is the edge of the habitat at which trees are capable of growing. It is found at high elevations and high latitudes. Beyond the tree line, trees cannot tolerate the environmental conditions (usually cold temperatures, extreme snowp ...

, the forest consisted of mountain hemlock

''Tsuga mertensiana'', known as mountain hemlock, is a species of hemlock native to the west coast of North America, found between Southcentral Alaska and south-central California.

Description

''Tsuga mertensiana'' is a large evergreen conifer ...

, Pacific silver fir

''Abies amabilis'', commonly known as the Pacific silver fir, is a fir native to the Pacific Northwest of North America, occurring in the Pacific Coast Ranges and the Cascade Range. It is also commonly referred to as the white fir, red fir, lov ...

and Alaska yellow cedar. Large mammals included Roosevelt elk

The Roosevelt elk (''Cervus canadensis roosevelti)'', also known commonly as the Olympic elk and Roosevelt's wapiti, is the largest of the four surviving subspecies of elk (''Cervus canadensis'') in North America by body mass (although by antle ...

, black-tailed deer

Two forms of black-tailed deer or blacktail deer that occupy coastal woodlands in the Pacific Northwest of North America are subspecies of the mule deer (''Odocoileus hemionus''). They have sometimes been treated as a species, but virtually all r ...

, American black bear

The American black bear (''Ursus americanus''), also called simply a black bear or sometimes a baribal, is a medium-sized bear endemic to North America. It is the continent's smallest and most widely distributed bear species. American black bear ...

, and mountain lion

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') is a large cat native to the Americas. Its range spans from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes in South America and is the most widespread of any large wild terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere. I ...

.

The Treeline

The tree line is the edge of the habitat at which trees are capable of growing. It is found at high elevations and high latitudes. Beyond the tree line, trees cannot tolerate the environmental conditions (usually cold temperatures, extreme snowp ...

at Mount St. Helens was unusually low, at about , the result of prior volcanic disturbance of the forest, as the treeline was thought to be moving up the slopes before the eruption. Alpine meadows were uncommon at Mount St. Helens. Mountain goats inhabited higher elevations of the peak, although their population was eliminated by the 1980 eruption.

Ecological disturbance caused by eruption

The eruption of Mount St. Helens has been subject to more ecological study than has any other eruption, because research intodisturbance

Disturbance and its variants may refer to:

Math and science

* Disturbance (ecology), a temporary change in average environmental conditions that causes a pronounced change in an ecosystem

* Disturbance (geology), linear zone of faults and folds ...

commenced immediately after the eruption and because the eruption did not sterilize the immediate area. More than half of the papers on ecological response to volcanic eruption originated from studies of Mount St. Helens.

Perhaps the most important ecological concept originating from the study of Mount St. Helens is the biological legacy. Biological legacies are the survivors of catastrophic disturbance; they can either be alive (e.g., plants that survive ashfall or pyroclastic flow), organic debris, or biotic patterns remaining from before the disturbance. These biological legacies highly influence the reestablishment of the post-disturbance ecology.

Human history

Importance to indigenous tribes

Native American lore contains numerous stories to explain the eruptions of Mount St. Helens and other Cascade volcanoes. The best known of these is the Bridge of the Gods story told by theKlickitat people

The Klickitat (also spelled Klikitat) are a Native American tribe of the Pacific Northwest. Today most Klickitat are enrolled in the federally recognized Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, some are also part of the Confederated ...

.

In the story, the chief of all the gods and his two sons, Pahto (also called Klickitat) and Wy'east, traveled down theThe mountain is also of sacred importance to theColumbia River The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...from the Far North in search for a suitable area to settle. They came upon an area that is now calledThe Dalles The Dalles is the largest city of Wasco County, Oregon, United States. The population was 16,010 at the 2020 census, and it is the largest city on the Oregon side of the Columbia River between the Portland Metropolitan Area, and Hermiston ...and thought they had never seen a land so beautiful. The sons quarreled over the land, so to solve the dispute their father shot two arrows from his mighty bow – one to the north and the other to the south. Pahto followed the arrow to the north and settled there while Wy'east did the same for the arrow to the south. The chief of the gods then built the Bridge of the Gods, so his family could meet periodically. When the two sons of the chief of the gods fell in love with a beautiful maiden named Loowit, she could not choose between them. The two young chiefs fought over her, burying villages and forests in the process. The area was devastated and the earth shook so violently that the huge bridge fell into the river, creating the cascades of theColumbia River Gorge The Columbia River Gorge is a canyon of the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Up to deep, the canyon stretches for over as the river winds westward through the Cascade Range, forming the boundary between the sta .... For punishment, the chief of the gods struck down each of the lovers and transformed them into great mountains where they fell. Wy'east, with his head lifted in pride, became the volcano known today asMount Hood Mount Hood is a potentially active stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc. It was formed by a subduction zone on the Pacific coast and rests in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located about east-southeast of Portlan .... Pahto, with his head bent toward his fallen love, was turned into Mount Adams. The beautiful Loowit became Mount St. Helens, known to the Klickitats as Louwala-Clough, which means "smoking or fire mountain" in their language (theSahaptin The Sahaptin are a number of Native American tribes who speak dialects of the Sahaptin language. The Sahaptin tribes inhabited territory along the Columbia River and its tributaries in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Sahaptin-s ...call the mountain Loowit).

Cowlitz Cowlitz may refer to:

People

* Cowlitz people, an indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest

** Cowlitz language, member of the Tsamosan branch of the Coast Salish family of Salishan languages

* Cowlitz Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe of ...

and Yakama

The Yakama are a Native American tribe with nearly 10,851 members, based primarily in eastern Washington state.

Yakama people today are enrolled in the federally recognized tribe, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Their Yak ...

tribes that also live in the area. They find the area above its tree line to be of exceptional spiritual significance, and the mountain (which they call "Lawetlat'la", roughly translated as "the smoker") features prominently in their creation story, and in some of their songs and rituals. In recognition of its cultural significance, over of the mountain (roughly bounded by the Loowit Trail) have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

.

Other area tribal names for the mountain include "nšh´ák´" ("water coming out") from the Upper Chehalis

Upper Chehalis (''Q̉ʷay̓áyiłq̉'') is a member of the Tsamosan (Olympic) branch of the Coast Salish family of Salishan languages

The Salishan (also Salish) languages are a family of languages of the Pacific Northwest in North America ( ...

, and "aka akn" ("snow mountain"), a Kiksht

Upper Chinook, endonym Kiksht, also known as Columbia Chinook, and Wasco-Wishram after its last surviving dialect, is a recently extinct language of the US Pacific Northwest. It had 69 speakers in 1990, of whom 7 were monolingual: five Wasco and ...

term.

Exploration by Europeans

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

Commander George Vancouver

Captain George Vancouver (22 June 1757 – 10 May 1798) was a British Royal Navy officer best known for his 1791–1795 expedition, which explored and charted North America's northwestern Pacific Coast regions, including the coasts of what a ...

and the officers of HMS ''Discovery'' made the Europeans' first recorded sighting of Mount St. Helens on 19 May 1792, while surveying the northern Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

coast. Vancouver named the mountain for British diplomat Alleyne Fitzherbert, 1st Baron St Helens on 20 October 1792, as it came into view when the ''Discovery'' passed into the mouth of the Columbia River.

Years later, explorers, traders, and missionaries heard reports of an erupting volcano in the area. Geologists and historians determined much later that the eruption took place in 1800, marking the beginning of the 57 year-long Goat Rocks Eruptive Period (see geology section). Alarmed by the "dry snow," the Nespelem tribe of northeastern Washington supposedly danced and prayed rather than collecting food and suffered during that winter from starvation.

In late 1805 and early 1806, members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

spotted Mount St. Helens from the Columbia River but did not report either an ongoing eruption or recent evidence of one. They did however report the presence of quicksand

Quicksand is a colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a ...

and clogged channel conditions at the mouth of the Sandy River near Portland, suggesting an eruption by Mount Hood

Mount Hood is a potentially active stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc. It was formed by a subduction zone on the Pacific coast and rests in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located about east-southeast of Portlan ...

sometime in the previous decades.

In 1829, Hall J. Kelley

Hall Jackson Kelley (February 24, 1790 – January 20, 1874) was an American settler and writer from New England known for his strong advocacy for settlement by the United States of the Oregon Country in the 1820s and 1830s. A native of New Hamps ...

led a campaign to rename the Cascade Range as the President's Range and also to rename each major Cascade mountain after a former President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

. In his scheme Mount St. Helens was to be renamed Mount Washington.

European colonization and use of the area

The first authenticated non-Indigenous eyewitness report of a volcanic eruption was made in March 1835 by

The first authenticated non-Indigenous eyewitness report of a volcanic eruption was made in March 1835 by Meredith Gairdner Meredith is a Welsh language, Welsh Brittonic languages, Brittonic family name, and is also sometimes used as a girl's or boy's forename. The Welsh form is "Maredudd".

People

* Meredith (given name)

* Meredith (surname)

Places Australia

* Meredith ...

, while working for the Hudson's Bay Company stationed at Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of the ...

. He sent an account to the ''Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal'', which published his letter in January 1836. James Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (February 12, 1813 – April 14, 1895) was an American geologist, mineralogist, volcanologist, and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcano, volcanic activity, and the ...

of Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, while sailing with the United States Exploring Expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby ...

, saw the quiescent peak from off the mouth of the Columbia River in 1841. Another member of the expedition later described "cellular basaltic lavas" at the mountain's base.

In the late fall or early winter of 1842, nearby European settlers and missionaries witnessed the so-called Great Eruption. This small-volume outburst created large ash clouds, and mild explosions followed for 15 years. The eruptions of this period were likely phreatic

''Phreatic'' is a term used in hydrology to refer to aquifers, in speleology to refer to cave passages, and in volcanology to refer to a type of volcanic eruption.

Hydrology

The term phreatic (the word originates from the Greek , meaning "well" ...

(steam explosions). Josiah Parrish in Champoeg, Oregon

Champoeg ( , historically Horner, John B. (1919). ''Oregon: Her History, Her Great Men, Her Literature''. The J.K. Gill Co.: Portland. p. 398.) is a former town in the U.S. state of Oregon. Now a ghost town, it was an important settlement in the W ...

witnessed Mount St. Helens in eruption on 22 November 1842. Ash from this eruption may have reached The Dalles, Oregon

The Dalles is the largest city of Wasco County, Oregon, United States. The population was 16,010 at the 2020 census, and it is the largest city on the Oregon side of the Columbia River between the Portland Metropolitan Area, and Hermiston ...

, 48 miles (80 km) southeast of the volcano.

In October 1843, future California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

governor Peter H. Burnett

Peter Hardeman Burnett (November 15, 1807May 17, 1895) was an American politician who served as the first elected California interim government, 1846–1850#Interim governors, Governor of California from December 20, 1849, to January 9, 1851. Bur ...

recounted a very likely apocryphal story of an Indigenous man who badly burned his foot and leg in lava or hot ash while hunting for deer. The story went that the injured man sought treatment at Fort Vancouver, but the contemporary fort commissary steward, Napoleon McGilvery, disclaimed knowledge of the incident. British lieutenant Henry J. Warre sketched the eruption in 1845, and two years later Canadian painter Paul Kane

Paul Kane (September 3, 1810 – February 20, 1871) was an Irish-born Canadian painter, famous for his paintings of First Nations peoples in the Canadian West and other Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans in the Columbia Dis ...

created watercolors of the gently smoking mountain. Warre's work showed erupting material from a vent about a third of the way down from the summit on the mountain's west or northwest side (possibly at Goat Rocks), and one of Kane's field sketches shows smoke emanating from about the same location.

On April 17, 1857, the ''Republican'', a Steilacoom, Washington

Steilacoom () is a town in Pierce County, Washington, United States. The population was 6,727 at the 2020 census. Steilacoom incorporated in 1854 and became the first incorporated town in what is now the state of Washington. It has also become a ...

, newspaper, reported that "Mount St. Helens, or some other mount to the southward, is seen ... to be in a state of eruption". The lack of a significant ash layer associated with this event indicates that it was a small eruption. This was the first reported volcanic activity since 1854.

Before the 1980 eruption, Spirit Lake offered year-round recreational activities. In the summer there was boating

Boating is the leisurely activity of travelling by boat, or the recreational use of a boat whether Motorboat, powerboats, Sailing, sailboats, or man-powered vessels (such as rowing and paddle boats), focused on the travel itself, as well as sp ...

, swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, or other liquid, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Locomotion is achieved through coordinated movement of the limbs and the body to achieve hydrodynamic thrust that r ...

, and camping

Camping is an outdoor activity involving overnight stays away from home, either without shelter or using basic shelter such as a tent, or a recreational vehicle. Typically, participants leave developed areas to spend time outdoors in more nat ...

, while in the winter there was skiing

Skiing is the use of skis to glide on snow. Variations of purpose include basic transport, a recreational activity, or a competitive winter sport. Many types of competitive skiing events are recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IO ...

.

Human impact from the 1980 eruption

Fifty-seven people were killed during the eruption. Had the eruption occurred one day later, when loggers would have been at work, rather than on a Sunday, the death toll could have been much higher.

Eighty-three-year-old

Fifty-seven people were killed during the eruption. Had the eruption occurred one day later, when loggers would have been at work, rather than on a Sunday, the death toll could have been much higher.

Eighty-three-year-old Harry R. Truman

Harry R. Truman (October 30, 1896 – May 18, 1980) was an American businessman, bootlegger, and prospector. He

lived near Mount St. Helens, an active volcano in the state of Washington, and was the owner and caretaker of Mount St. Helens Lodge ...

, who had lived near the mountain for 54 years, gained media attention when he decided not to evacuate before the impending eruption, despite repeated pleas by local authorities. His body was never found after the eruption.

Another victim of the eruption was 30-year-old volcanologist

A volcanologist, or volcano scientist, is a geologist who focuses on understanding the formation and eruptive activity of volcanoes. Volcanologists frequently visit volcanoes, sometimes active ones, to observe and monitor volcanic eruptions, col ...

David A. Johnston

David Alexander Johnston (December 18, 1949 – May 18, 1980) was an American United States Geological Survey (USGS) volcanologist who was killed by the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in the U.S. state of Washington. A principal scientist on ...

, who was stationed on the nearby Coldwater Ridge. Moments before his position was hit by the pyroclastic flow, Johnston radioed his last words

Last words are the final utterances before death. The meaning is sometimes expanded to somewhat earlier utterances.

Last words of famous or infamous people are sometimes recorded (although not always accurately) which became a historical and liter ...

: "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" Johnston's body was never found.

U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

surveyed the damage and said, "Someone said this area looked like a moonscape. But the moon looks more like a golf course compared to what's up there." A film crew, led by Seattle filmmaker Otto Seiber, was dropped by helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

on St. Helens on May 23 to document the destruction. Their compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

es, however, spun in circles and they quickly became lost. A second eruption occurred on May 25, but the crew survived and was rescued two days later by National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

helicopter pilots. Their film, ''The Eruption of Mount St. Helens'', later became a popular documentary.

The eruption had negative effects beyond the immediate area of the volcano. Ashfall caused approximately $100 million of damage to agriculture downwind in Eastern Washington.

The eruption also had positive impacts on society. Apple and wheat production were higher in the 1980 growing season, possibly due to ash helping to retain moisture in the soil. The ash was also a source of income: it was the raw material for the artificial gemstone helenite, or for ceramic glazes, or sold as a tourist curio.

Protection and later history

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

and the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

established the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument

Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument is a U.S. National Monument that includes the area around Mount St. Helens in Washington. It was established on August 27, 1982, by U.S. President Ronald Reagan, following the 1980 eruption. The 110,0 ...

, a area around the mountain and within the Gifford Pinchot National Forest

Gifford Pinchot National Forest is a National Forest located in southern Washington, managed by the United States Forest Service. With an area of 1.32 million acres (5300 km2), it extends 116 km along the western slopes of Cascade Ran ...

.

Following the 1980 eruption, the area was left to gradually return to its natural state. In 1987, the U.S. Forest Service

The United States Forest Service (USFS) is an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 154 national forests and 20 national grasslands. The Forest Service manages of land. Major divisions of the agency in ...

reopened the mountain to climbing. It remained open until 2004 when renewed activity caused the closure of the area around the mountain (see ''Geological history'' section above for more details). The Monitor Ridge trail, which previously let up to 100 permitted hikers per day climb to the summit, ceased operation. On July 21, 2006, the mountain was again opened to climbers. In February 2010, a climber died after falling from the rim into the crater.

Climbing and recreation

Mount St. Helens is a common climbing destination for both beginning and experiencedmountaineers

Mountaineering or alpinism, is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending tall mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas. Indoor climbing, sport climbing, an ...

. The peak is climbed year-round, although it is more often climbed from late spring through early fall. All routes include sections of steep, rugged terrain. A permit system has been in place for climbers since 1987. A climbing permit is required year-round for anyone who will be above on the slopes of Mount St. Helens.

The standard hiking

Hiking is a long, vigorous walk, usually on trails or footpaths in the countryside. Walking for pleasure developed in Europe during the eighteenth century.AMATO, JOSEPH A. "Mind over Foot: Romantic Walking and Rambling." In ''On Foot: A Histor ...

/mountaineering

Mountaineering or alpinism, is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending tall mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas. Indoor climbing, sport climbing, a ...

route in the warmer months is the Monitor Ridge Route, which starts at the Climbers Bivouac. This is the most crowded route to the summit in the summer and gains about in approximately to reach the crater rim. Although strenuous, it is considered a non-technical climb that involves some scrambling

Scrambling is a mountaineering term for ascending steep terrain using one's hands to assist in holds and balance.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. It is also used to describe terrain that falls between hiking and rock climbing (as a “scramb ...

. Most climbers complete the round trip in 7 to 12 hours.

The Worm Flows Route is considered the standard winter route on Mount St. Helens, as it is the most direct route to the summit. The route gains about in elevation over about from trailhead to summit but does not demand the technical climbing that some other Cascade peaks like Mount Rainier

Mount Rainier (), indigenously known as Tahoma, Tacoma, Tacobet, or təqʷubəʔ, is a large active stratovolcano in the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest, located in Mount Rainier National Park about south-southeast of Seattle. With a s ...

do. The route name refers to the rocky lava flows that surround the route. This route can be accessed via the Marble Mountain Sno-Park and the Swift Ski Trail.

The mountain is now circled by the Loowit Trail at elevations of . The northern segment of the trail from the South Fork Toutle River on the west to Windy Pass on the east is a restricted zone where camping, biking, pets, fires, and off-trail excursions are all prohibited.

On April 14, 2008, John Slemp, a snowmobiler from Damascus, Oregon

Damascus is a census-designated place and once-disincorporated city in Clackamas County, Oregon, United States. Established in 1867, it was incorporated in 2004 in an effort to enable local land use decision-making control by the community. It ...

, fell 1,500 feet into the crater after a snow cornice