Mound-builders on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A number of

A number of

The namesake cultural trait of the Mound Builders was the building of mounds and other earthworks. These burial and ceremonial structures were typically flat-topped pyramids or

The namesake cultural trait of the Mound Builders was the building of mounds and other earthworks. These burial and ceremonial structures were typically flat-topped pyramids or  Some

Some

Between 1540 and 1542,

Between 1540 and 1542,  The artist

The artist

The most complete reference for these earthworks is ''

The most complete reference for these earthworks is ''

Radiocarbon dating has established the age of the earliest Archaic mound complex in southeastern Louisiana. One of the two Monte Sano Site mounds, excavated in 1967 before being destroyed for new construction at Baton Rouge, was dated at 6220 BP (plus or minus 140 years). Researchers at the time thought that such societies were not organizationally capable of this type of construction.Rebecca Saunders,

Radiocarbon dating has established the age of the earliest Archaic mound complex in southeastern Louisiana. One of the two Monte Sano Site mounds, excavated in 1967 before being destroyed for new construction at Baton Rouge, was dated at 6220 BP (plus or minus 140 years). Researchers at the time thought that such societies were not organizationally capable of this type of construction.Rebecca Saunders,

The Case for Archaic Period Mounds in Southeastern Louisiana

, ''Southeastern Archaeology'', Vol. 13, No. 2, Winter 1994. Retrieved November 4, 2011 It has since been dated as about 6500 BP, or 4500 BCE, although not all agree.Joe W. Saunders,

Middle Archaic and Watson Brake

, in ''Archaeology of Louisiana'', edited by Mark A. Rees, Ian W. (FRW) Brown, LSU Press, 2010, p. 67 Watson Brake is located in the floodplain of the

The oldest mound associated with the Woodland period was the mortuary mound and pond complex at the

The oldest mound associated with the Woodland period was the mortuary mound and pond complex at the

The Coles Creek culture is a Late Woodland culture (700–1200 CE) in the

The Coles Creek culture is a Late Woodland culture (700–1200 CE) in the

Around 900–1450 CE, the

Around 900–1450 CE, the

Fort Ancient is the name for a Native American culture that flourished from 1000 to 1650 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited land along the

Fort Ancient is the name for a Native American culture that flourished from 1000 to 1650 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited land along the

A continuation of the Coles Creek culture in the lower

A continuation of the Coles Creek culture in the lower

File:Hopewellsphere2 map HRoe 2008.jpg,

File:Mississippian cultures HRoe 2010.jpg,

On April 23, 1843, nine men unearthed human bones and six small, bell-shaped plates in Kinderhook, Illinois. Both sides of the plates apparently contained some sort of ancient writings. The plates, later known as the

On April 23, 1843, nine men unearthed human bones and six small, bell-shaped plates in Kinderhook, Illinois. Both sides of the plates apparently contained some sort of ancient writings. The plates, later known as the

On June 29, 1860, David Wyrick, the surveyor of Licking County near Newark, discovered the so called Keystone in a shallow excavation at the monumental Newark Earthworks, which is an extraordinary set of ancient geometric enclosures created by Indigenous people. There he dug up a four-sided, plumb-bob-shaped stone with

On June 29, 1860, David Wyrick, the surveyor of Licking County near Newark, discovered the so called Keystone in a shallow excavation at the monumental Newark Earthworks, which is an extraordinary set of ancient geometric enclosures created by Indigenous people. There he dug up a four-sided, plumb-bob-shaped stone with

Lost Race Myth

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20070205072711/http://www.artisthideout.com/art-of-the-ancients-2/ Artist Hideout, Art of the Ancients

Ancient Monuments Placemarks

*

With Climate Swing, a Culture Bloomed in Americas

(mound builders in Peru)

Science 19 September 1997

(a mound complex in Louisiana at 5400u–5000 years ago)

Bruce Smith video

on the 1880s Smithsonian explorations to determine who built the ancient earthen mounds in eastern North America can be viewed as part of the serie

{{Authority control Pre-Columbian architecture Archaic period in North America Formative period in the Americas Archaeological cultures of North America Pre-Columbian cultures Woodland period Native American history Mounds 4th-millennium BC establishments 16th-century disestablishments in North America Pyramids in North America

pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, th ...

cultures are collectively termed "Mound Builders". The term does not refer to a specific people or archaeological culture, but refers to the characteristic mound

A mound is a heaped pile of earth, gravel, sand, rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded area of topographically higher el ...

earthworks erected for an extended period of more than 5,000 years. The "Mound Builder" cultures span the period of roughly 3500 BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

(the construction of Watson Brake) to the 16th century CE, including the Archaic period, Woodland period

In the classification of :category:Archaeological cultures of North America, archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 Common Era, BCE to European con ...

(Calusa

The Calusa ( ) were a Native American people of Florida's southwest coast. Calusa society developed from that of archaic peoples of the Everglades region. Previous indigenous cultures had lived in the area for thousands of years.

At the time of ...

culture, Adena Adena may refer to:

Artists

*ADENA, Romanian singer-songwriter

*Adeena Karasick (born 1965), Canadian poet, performance artist, and essayist

*Adena Halpern (born 1968), American author

*Adena Jacobs (born 1982), Australian theatre director

Places

...

and Hopewell culture

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from ...

s), and Mississippian period

The Mississippian ( , also known as Lower Carboniferous or Early Carboniferous) is a subperiod in the geologic timescale or a subsystem of the geologic record. It is the earlier of two subperiods of the Carboniferous period lasting from roughly ...

. Geographically, the cultures were present in the region of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

, the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

Valley, and the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

valley and its tributary waters.

The first mound building was an early marker of political and social complexity among the cultures in the Eastern United States. Watson Brake in Louisiana, constructed about 3500 BCE during the Middle Archaic period, is currently the oldest known and dated mound complex in North America. It is one of 11 mound complexes from this period found in the Lower Mississippi Valley.

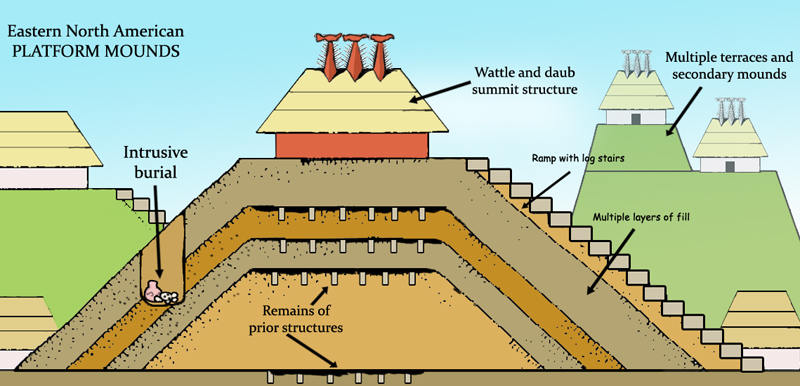

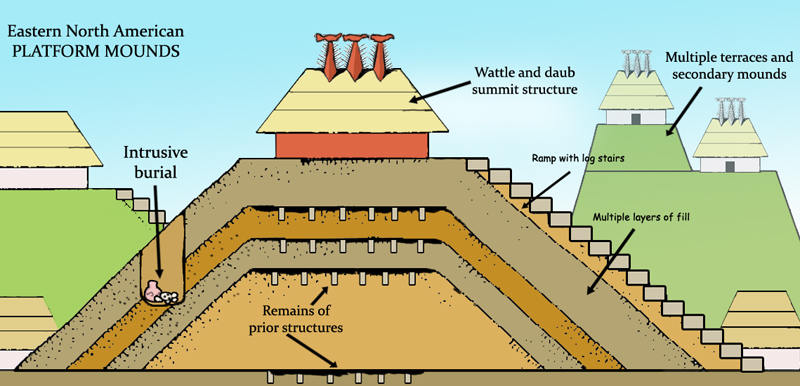

These cultures generally had developed hierarchical societies that had an elite. These commanded hundreds or even thousands of workers to dig up tons of earth with the hand tools available, move the soil long distances, and finally, workers to create the shape with layers of soil as directed by the builders.

From about 800 CE, the mound building cultures were dominated by the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

, a large archaeological horizon, whose youngest descendants, the Plaquemine culture

The Plaquemine culture was an archaeological culture (circa 1200 to 1700 CE) centered on the Lower Mississippi River valley. It had a deep history in the area stretching back through the earlier Coles Creek (700-1200 CE) and Troyville culture ...

and the Fort Ancient culture

Fort Ancient is a name for a Native American culture that flourished from Ca. 1000-1750 CE and predominantly inhabited land near the Ohio River valley in the areas of modern-day southern Ohio, northern Kentucky, southeastern Indiana and western ...

, were still active at the time of European contact in the 16th century. One tribe of the Fort Ancient culture has been identified as the Mosopelea

The Mosopelea, or Ofo, were a Siouan-speaking Native American people who historically inhabited the upper Ohio River. In reaction to Iroquois Confederacy invasions to take control of hunting grounds in the late 17th century, they moved south to t ...

, presumably of southeast Ohio, who were speakers of an Ohio Valley Siouan language. The bearers of the Plaquemine culture were presumably speakers of the Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

language isolate.

The first description of these cultures is due to Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

, written between 1540 and 1542.

Mounds

The namesake cultural trait of the Mound Builders was the building of mounds and other earthworks. These burial and ceremonial structures were typically flat-topped pyramids or

The namesake cultural trait of the Mound Builders was the building of mounds and other earthworks. These burial and ceremonial structures were typically flat-topped pyramids or platform mound

Platform may refer to:

Technology

* Computing platform, a framework on which applications may be run

* Platform game, a genre of video games

* Car platform, a set of components shared by several vehicle models

* Weapons platform, a system or ...

s, flat-topped or rounded cones, elongated ridges, and sometimes a variety of other forms. They were generally built as part of complex villages. The early earthworks built in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

around 3500 BCE are the only ones known to have been built by a hunter-gatherer culture, rather than a more settled culture based on agricultural surpluses.

The best-known flat-topped pyramidal structure is Monks Mound

Monks Mound is the largest Pre-Columbian earthwork in the Americas and the largest pyramid north of Mesoamerica. The beginning of its construction dates from 900–955 CE. Located at the Cahokia Mounds UNESCO World Heritage Site near Collinsvil ...

at Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south-w ...

, near present-day Collinsville, Illinois

Collinsville is a city located mainly in Madison County, and partially in St. Clair County, Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 25,579, an increase from 24,707 in 2000. Collinsville is approximately from St. Louis, Mis ...

. This mound appears to have been the main ceremonial and residential mound for the religious and political leaders; it is more than tall and is the largest pre-Columbian earthwork north of Mexico. This site had numerous mounds, some with conical or ridge tops, as well as palisaded stockades protecting the large settlement and elite quarter. At its maximum about 1150 CE, Cahokia was an urban settlement with 20,000–30,000 people; this population was not exceeded by North American European settlements until after 1800.

Some

Some effigy mound

An effigy mound is a raised pile of earth built in the shape of a stylized animal, symbol, religious figure, human, or other figure. The Effigy Moundbuilder culture is primarily associated with the years 550-1200 CE during the Late Woodland Peri ...

s were constructed in the shapes or outlines of culturally significant animals. The most famous effigy mound, Serpent Mound

The Great Serpent Mound is a 1,348-foot-long (411 m), three-foot-high prehistoric effigy mound located in Peebles, Ohio. The mound itself resides on the Serpent Mound crater plateau, running along the Ohio Brush Creek in Adams County, Ohio. ...

in southern Ohio, ranges from to just over tall, wide, more than long, and shaped as an undulating serpent

Serpent or The Serpent may refer to:

* Snake, a carnivorous reptile of the suborder Serpentes

Mythology and religion

* Sea serpent, a monstrous ocean creature

* Serpent (symbolism), the snake in religious rites and mythological contexts

* Serp ...

.

Early descriptions

Between 1540 and 1542,

Between 1540 and 1542, Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

, the Spanish conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

, traversed what became the southeastern United States. There he encountered many different mound-builder peoples who were perhaps descendants of the great Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

. De Soto observed people living in fortified towns with lofty mounds

A mound is an artificial heap or pile, especially of earth, rocks, or sand.

Mound and Mounds may also refer to:

Places

* Mound, Louisiana, United States

* Mound, Minnesota, United States

* Mound, Texas, United States

* Mound, West Virginia

* Moun ...

and plazas, and surmised that many of the mounds served as foundations for priestly temples. Near present-day Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navig ...

, de Soto encountered a group ruled by a queen, Cofitachequi

Cofitachequi was a paramount chiefdom founded about 1300 AD and encountered by the Hernando de Soto expedition in South Carolina in April 1540. Cofitachequi was later visited by Juan Pardo during his two expeditions (1566–1568) and by Henry W ...

. She told him that the mounds within her territory served as burial places for nobles.

The artist

The artist Jacques le Moyne

Jacques le Moyne de Morgues ( 1533–1588) was a French artist and member of Jean Ribault's expedition to the New World. His depictions of Native American life and culture, colonial life, and plants are of extraordinary historical importa ...

, who had accompanied French settlers to northeastern Florida during the 1560s, likewise noted Native American groups using existing mounds and constructing others. He produced a series of watercolor paintings depicting scenes of native life. Although most of his paintings have been lost, some engravings were copied from the originals and published in 1591 by a Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

company. Among these is a depiction of the burial of an aboriginal Floridian tribal chief, an occasion of great mourning and ceremony. The original caption reads:

Maturin Le Petit Maturin Le Petit (1693–1739) was a Jesuit priest sent among the Choctaws in 1726 and to observe the Natchez in 1730 in an area of what became part of Mississippi. He was also in New Orleans. He wrote of the Natchez that, "The sun is the principa ...

, a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

priest, met the Natchez people

The Natchez (; Natchez pronunciation ) are a Native American people who originally lived in the Natchez Bluffs area in the Lower Mississippi Valley, near the present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi in the United States. They spoke a language ...

, as did Le Page du Pratz

Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz (1695?–1775)

(1758), a French explorer. Both observed them in the area that today is known as Mississippi. The Natchez were devout worshippers of the sun. Having a population of some 4,000, they occupied at least nine villages and were presided over by a paramount chief

A paramount chief is the English-language designation for the highest-level political leader in a regional or local polity or country administered politically with a chief-based system. This term is used occasionally in anthropological and arch ...

, known as the Great Sun, who wielded absolute power. Both observers noted the high temple mounds which the Natchez had built so that the Great Sun could commune with God, the sun. His large residence was built atop the highest mound, from "which, every morning, he greeted the rising sun, invoking thanks and blowing tobacco smoke to the four cardinal directions".

Archaeological surveys

The most complete reference for these earthworks is ''

The most complete reference for these earthworks is ''Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley

''Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley'' (full title ''Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley: Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations'') (1848) by the Americans Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton ...

'', written by Ephraim G. Squier

Ephraim George Squier (June 17, 1821 – April 17, 1888), usually cited as E. G. Squier, was an American archaeologist, history writer, painter and newspaper editor.

Biography

Squier was born in Bethlehem, New York, the son of a minister, Joel S ...

and Edwin H. Davis. It was published in 1848 by the Smithsonian Institution. Since many of the features which the authors documented have since been destroyed or diminished by farming and development, their surveys, sketches, and descriptions are still used by modern archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

. All of the sites which they identified as located in Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

came from the manuscripts of C. S. Rafinesque

Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz (; October 22, 1783September 18, 1840) was a French 19th-century polymath born near Constantinople in the Ottoman Empire and self-educated in France. He traveled as a young man in the United States, ultimat ...

.

Chronology

Archaic era

Radiocarbon dating has established the age of the earliest Archaic mound complex in southeastern Louisiana. One of the two Monte Sano Site mounds, excavated in 1967 before being destroyed for new construction at Baton Rouge, was dated at 6220 BP (plus or minus 140 years). Researchers at the time thought that such societies were not organizationally capable of this type of construction.Rebecca Saunders,

Radiocarbon dating has established the age of the earliest Archaic mound complex in southeastern Louisiana. One of the two Monte Sano Site mounds, excavated in 1967 before being destroyed for new construction at Baton Rouge, was dated at 6220 BP (plus or minus 140 years). Researchers at the time thought that such societies were not organizationally capable of this type of construction.Rebecca Saunders,The Case for Archaic Period Mounds in Southeastern Louisiana

, ''Southeastern Archaeology'', Vol. 13, No. 2, Winter 1994. Retrieved November 4, 2011 It has since been dated as about 6500 BP, or 4500 BCE, although not all agree.Joe W. Saunders,

Middle Archaic and Watson Brake

, in ''Archaeology of Louisiana'', edited by Mark A. Rees, Ian W. (FRW) Brown, LSU Press, 2010, p. 67 Watson Brake is located in the floodplain of the

Ouachita River

The Ouachita River ( ) is a river that runs south and east through the U.S. states of Arkansas and Louisiana, joining the Tensas River to form the Black River near Jonesville, Louisiana. It is the 25th-longest river in the United States ( ...

near Monroe in northern Louisiana. Securely dated to about 5,400 years ago (around 3500 BCE), in the Middle Archaic period, it consists of a formation of 11 mounds from to tall, connected by ridges to form an oval nearly across.Saunders, in Rees and Brown (2010), ''Archaeology of Louisiana'', pp. 69–76 In the Americas, building of complex earthwork mounds started at an early date, well before the pyramids

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilate ...

of Egypt were constructed. Watson Brake was being constructed nearly 2,000 years before the better-known Poverty Point

Poverty Point State Historic Site/Poverty Point National Monument (french: Pointe de Pauvreté; 16 WC 5) is a prehistoric earthwork constructed by the Poverty Point culture, located in present-day northeastern Louisiana, though evidence of t ...

, and building continued for 500 years. Middle Archaic mound construction seems to have ceased about 2800 BCE, and scholars have not ascertained the reason, but it may have been because of changes in river patterns or other environmental factors.

With the 1990s dating of Watson Brake and similar complexes, scholars established that pre-agricultural, pre-ceramic American societies could organize to accomplish complex construction during extended periods of time, invalidating scholars' traditional ideas of Archaic society. Watson Brake was built by a hunter-gatherer society, the people of which occupied the area on only a seasonal basis, but where successive generations organized to build the complex mounds over a 500-year period. Their food consisted mostly of fish and deer, as well as available plants.

Poverty Point, built about 1500 BCE in what is now Louisiana, is a prominent example of Late Archaic mound-builder construction (around 2500 BCE – 1000 BCE). It is a striking complex of more than , where six earthwork crescent ridges were built in concentric arrangement, interrupted by radial aisles. Three mounds are also part of the main complex, and evidence of residences extends for about along the bank of Bayou Macon

Bayou Macon is a bayou in Arkansas and Louisiana. It begins in Desha County, Arkansas, and flows south, between the Boeuf River to its west and the Mississippi River to its east, before joining Joe's Bayou south of Delhi in Richland Parish, Loui ...

. It is the major site among 100 associated with the Poverty Point culture

The Poverty Point culture is the archaeological culture of a prehistoric indigenous peoples who inhabited a portion of North America's lower Mississippi Valley and surrounding Gulf coast from about 1730 – 1350 BC.

Archeologists have identified ...

and is one of the best-known early examples of earthwork monumental architecture. Unlike the localized societies during the Middle Archaic, this culture showed evidence of a wide trading network outside its area, which is one of its distinguishing characteristics.

Horr's Island

Horr's Island is a significant Archaic period archaeological site located on an island in Southwest Florida formerly known as ''Horr's Island''. Horr's Island (now called ''Key Marco'', not to be confused with the archaeological site Key Marco) i ...

, Florida, now a gated community next to Marco Island

Marco may refer to:

People

* Marco (given name), people with the given name Marco

* Marco (actor) (born 1977), South Korean model and actor

* Georg Marco (1863–1923), Romanian chess player of German origin

* Tomás Marco (born 1942), Spanish co ...

, when excavated by Michael Russo in 1980 found an Archaic Indian village site. Mound A was a burial mound that dated to 3400 BCE, making it the oldest known burial mound in North America.

Woodland period

The oldest mound associated with the Woodland period was the mortuary mound and pond complex at the

The oldest mound associated with the Woodland period was the mortuary mound and pond complex at the Fort Center

Fort Center is an archaeological site in Glades County, Florida, United States, a few miles northwest of Lake Okeechobee. It was occupied for more than 2,000 years, from 450 BCE until about 1700 CE. The inhabitants of Fort Center may have been cul ...

site in Glade County, Florida. 2012 excavations and dating by Thompson and Pluckhahn show that work began around 2600 BCE, seven centuries before the mound-builders in Ohio.

The Archaic period was followed by the Woodland period (''circa'' 1000 BCE). Some well-understood examples are the Adena culture

The Adena culture was a Pre-Columbian Native American culture that existed from 500 BCE to 100 CE, in a time known as the Early Woodland period. The Adena culture refers to what were probably a number of related Native American societies sharing ...

of Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, and parts of nearby states. The subsequent Hopewell culture

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from ...

built monuments from present-day Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

to Ohio; it is renowned for its geometric earthworks. The Adena and Hopewell were not the only mound-building peoples during this time period. Contemporaneous mound-building cultures existed throughout what is now the Eastern United States, stretching as far south as Crystal River in western Florida. During this time, in parts of present-day Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana, the Hopewellian Marksville culture

The Marksville culture was an archaeological culture in the lower Lower Mississippi valley, Yazoo valley, and Tensas valley areas of present-day Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and extended eastward along the Gulf Coast to the Mobile Bay are ...

degenerated and was succeeded by the Baytown culture

The Baytown culture was a Pre-Columbian Native American culture that existed from 300 to 700 CE in the lower Mississippi River Valley, consisting of sites in eastern Arkansas, western Tennessee, Louisiana, and western Mississippi. The Baytown Sit ...

. Reasons for degeneration include attacks from other tribes or the impact of severe climatic changes undermining agriculture.

Coles Creek culture

The Coles Creek culture is a Late Woodland culture (700–1200 CE) in the

The Coles Creek culture is a Late Woodland culture (700–1200 CE) in the Lower Mississippi Valley

The Mississippi River Alluvial Plain is an alluvial plain created by the Mississippi River on which lie parts of seven U.S. states, from southern Louisiana to southern Illinois (Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, Lou ...

in the Southern United States that marks a significant change in the cultural history of the area. Population and cultural and political complexity increased, especially by the end of the Coles Creek period. Although many of the classic traits of chiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

societies were not yet made, by 1000 CE, the formation of simple elite polities had begun. Coles Creek sites are found in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Mississippi, and Texas. The Coles Creek culture is considered ancestral to the Plaquemine culture.

Mississippian cultures

Around 900–1450 CE, the

Around 900–1450 CE, the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

developed and spread through the Eastern United States, primarily along the river valleys. The largest regional center where the Mississippian culture is first definitely developed is located in Illinois near the Mississippi, and is referred to presently as Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south-w ...

. It had several regional variants including the Middle Mississippian culture of Cahokia, the South Appalachian Mississippian variant at Moundville and Etowah, the Plaquemine Mississippian variant in south Louisiana and Mississippi, and the Caddoan Mississippian culture

The Caddoan Mississippian culture was a prehistoric Native American culture considered by archaeologists as a variant of the Mississippian culture. The Caddoan Mississippians covered a large territory, including what is now Eastern Oklahoma, Wes ...

of northwestern Louisiana, eastern Texas, and southwestern Arkansas. Like the mound builders of the Ohio, these people built gigantic mounds as burial and ceremonial places.

Fort Ancient culture

Fort Ancient is the name for a Native American culture that flourished from 1000 to 1650 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited land along the

Fort Ancient is the name for a Native American culture that flourished from 1000 to 1650 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited land along the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

in areas of modern-day southern Ohio, northern Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, and western West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

.

Plaquemine culture

A continuation of the Coles Creek culture in the lower

A continuation of the Coles Creek culture in the lower Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

Valley in western Mississippi and eastern Louisiana. Examples include the Medora site

The Medora site ( 16WBR1) is an archaeological site that is a type site for the prehistoric Plaquemine culture period. The name for the culture is taken from the proximity of Medora to the town of Plaquemine, Louisiana. The site is in West Baton ...

in West Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana; and the Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 1221)

...

and Emerald Mound

The Emerald Mound site ( 22 AD 504), also known as the '' Selsertown site'', is a Plaquemine culture Mississippian period archaeological site located on the Natchez Trace Parkway near Stanton, Mississippi, United States. The site dates from the ...

sites in Mississippi. Sites inhabited by Plaquemine peoples continued to be used as vacant ceremonial centers without large village areas much as their Coles Creek ancestors had done, although their layout began to show influences from Middle Mississippian peoples to the north. The Winterville and Holly Bluff (Lake George) sites in western Mississippi are good examples that exemplify this change of layout, but continuation of site usage. During the Terminal Coles Creek period (1150 to 1250 CE), contact increased with Mississippian cultures centered upriver near St. Louis, Missouri. This resulted in the adaption of new pottery techniques, as well as new ceremonial objects and possibly new social patterns during the Plaquemine period. As more Mississippian culture influences were absorbed, the Plaquemine area as a distinct culture began to shrink after CE 1350. Eventually, the last enclave of purely Plaquemine culture was the Natchez Bluffs area, while the Yazoo Basin and adjacent areas of Louisiana became a hybrid Plaquemine-Mississippian culture. This division was recorded by Europeans when they first arrived in the area. In the Natchez Bluffs area, the Taensa

The Taensa (also Taënsas, Tensas, Tensaw, and ''Grands Taensas'' in French) were a Native American people whose settlements at the time of European contact in the late 17th century were located in present-day Tensas Parish, Louisiana. The mean ...

and Natchez people

The Natchez (; Natchez pronunciation ) are a Native American people who originally lived in the Natchez Bluffs area in the Lower Mississippi Valley, near the present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi in the United States. They spoke a language ...

had held out against Mississippian influence and continued to use the same sites as their ancestors, and the Plaquemine culture is considered directly ancestral to these historic period groups encountered by Europeans. Groups who appear to have absorbed more Mississippian influence were identified as those tribes speaking the Tunican, Chitimachan, and Muskogean languages

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

.

Disappearance

Following the description byJacques le Moyne

Jacques le Moyne de Morgues ( 1533–1588) was a French artist and member of Jean Ribault's expedition to the New World. His depictions of Native American life and culture, colonial life, and plants are of extraordinary historical importa ...

in 1560, the mound building cultures seem to have disappeared within the next century. However, there were also other European accounts, earlier than 1560, that gives a first-hand description of the enormous earth-built mounds being constructed by the Native Americans. One of them was Garcilaso de la Vega (c.1539–1616), a Spanish chronicler also known as "''El Inca''" because of his Incan mother, who was also the record-keeper of the infamous ''De Soto'' expedition that landed in present-day Florida on May 31, 1538. Garcilaso gave a first-hand description through his ''Historia de la Florida'' (published in 1605, Lisbon, as ''La Florida del Inca'') describing how the Indians had built mounds and how the Native American Mound Cultures practiced their traditional way of life. De la Vega's accounts also include vital details about the Native American tribes' systems of government present in the South-East, tribal territories, and construction of mounds and temples. A few French expeditions in 1560s reported staying with Indian societies who had built mounds also.

Diseases

Later explorers to the same regions, only a few decades after mound-building settlements had been reported, found the regions largely depopulated with its residents vanished and the mounds untended. Conflicts with Europeans were dismissed by historians as the major cause of population reduction, since only few clashes had occurred between the natives and the Europeans in the area during the same period. The most-widely accepted explanation behind the disappearances were the infectious diseases from the Old World, such assmallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

, which had decimated most of the Native Americans from the last mound-builder civilization.

The Fort Ancient culture

Fort Ancient is a name for a Native American culture that flourished from Ca. 1000-1750 CE and predominantly inhabited land near the Ohio River valley in the areas of modern-day southern Ohio, northern Kentucky, southeastern Indiana and western ...

of the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

valley is considered a "sister culture" of the Mississippian horizon, or one of the "Mississippianised" cultures adjacent to the main areal of the mound building cultures. This culture was also mostly extinct in the 17th century, but remnants may have survived into the first half of the 18th century.

While this culture shows strong Mississippian influences, its bearers were most likely ethno-linguistically distinct from the Mississippians, possibly belonging to the Siouan

Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.

Name

Authors who call the entire ...

phylum. The only tribal name associated with the Fort Ancient culture in the historical record are the Mosopelea

The Mosopelea, or Ofo, were a Siouan-speaking Native American people who historically inhabited the upper Ohio River. In reaction to Iroquois Confederacy invasions to take control of hunting grounds in the late 17th century, they moved south to t ...

, recorded by Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin

Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin (1650-c.1712) was a French trader who was appointed in the early 1670s as the first cartographer in '' Nouvelle France'' (Canada) by the colony's governor. He was appointed in 1688 as royal hydrographer by Louis XIV. ...

in 1684 as inhabiting eight villages north of the Ohio River.

The Mosopelea are most likely identical to the Ofo (''Oufé'', ''Offogoula'') recorded in the same area in the 18th century.

The Ofo language

The Ofo language was a language spoken by the Mosopelea tribe until c. 1673 in what is now Ohio, along the Ohio River. The tribe moved down the Mississippi River to Mississippi, near the Natchez people, and then to Louisiana, settling near the ...

was formerly classified as Muskogean

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

but is now recognized as an eccentric member of the Western Siouan phylum. The late survival of the Fort Ancient culture is suggested by the remarkable amount of European made goods in the archaeological record which would have been acquired by trade even before direct European contact. These artifacts include brass and steel items, glassware, and melted down or broken goods reforged into new items.

The Fort Ancient peoples are known to have been severely affected by disease in the 17th century (Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

period), and

Carbon dating seems to indicate that they were wiped out by successive waves of disease.

Massacre and revolt

Because of the disappearance of the cultures by the end of the 17th century, the identification of the bearers of these cultures was an open question in 19th-century ethnography. Modern stratigraphic dating has established that the "Mound builders" have spanned the extended period of more than five millennia, so that any ethno-linguistic continuity is unlikely. The spread of theMississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

from the late 1st millennium CE most likely involved cultural assimilation, in archaeological terminology called "Mississippianised" cultures.

19th-century ethnography assumed that the Mound-builders were an ancient prehistoric race with no direct connection to the Southeastern Woodland peoples of the historical period.

A reference to this idea appears in the poem "The Prairies" (1832) by William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant (November 3, 1794 – June 12, 1878) was an American romantic poet, journalist, and long-time editor of the ''New York Evening Post''. Born in Massachusetts, he started his career as a lawyer but showed an interest in poetry ...

.

The cultural stage of the Southeastern Woodland natives encountered in the 18th and 19th centuries by British colonists was deemed incompatible with the comparatively advanced stone, metal, and clay artifacts of the archaeological record.

The age of the earthworks was also partly over-estimated.

Caleb Atwater

Caleb Atwater (December 1778 – March 13, 1867) was an American politician, historian, and early archaeologist in the state of Ohio. He served several terms as a state politician and was appointed as United States postmaster of Circleville, Ohio ...

's misunderstanding of stratigraphy caused him to significantly overestimate the age of the earthworks.

In his book, ''Antiquities Discovered in the Western States'' (1820), Atwater claimed that "Indian remains" were always found right beneath the surface of the earth, while artifacts associated with the Mound Builders were found fairly deep in the ground.

Atwater argued that they must be from a different group of people. The discovery of metal artifacts further convinced people that the Mound Builders were not identical to the Southeast Woodland Native Americans of the 18th century.

It is now thought that the most likely bearers of the Plaquemine culture

The Plaquemine culture was an archaeological culture (circa 1200 to 1700 CE) centered on the Lower Mississippi River valley. It had a deep history in the area stretching back through the earlier Coles Creek (700-1200 CE) and Troyville culture ...

, a late variant of the Mississippian culture,

were ancestral to the related Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

and Taensa

The Taensa (also Taënsas, Tensas, Tensaw, and ''Grands Taensas'' in French) were a Native American people whose settlements at the time of European contact in the late 17th century were located in present-day Tensas Parish, Louisiana. The mean ...

peoples.

The Natchez language

The Natchez language is the ancestral language of the Natchez people who historically inhabited Mississippi and Louisiana, and who now mostly live among the Muscogee and Cherokee peoples in Oklahoma. The language is considered to be either unrelat ...

is a language isolate, supporting the scenario that after the collapse of the Mound builder cultures in the 17th century, there was an influx of unrelated peoples into the area.

The Natchez are known to have historically occupied the Lower Mississippi Valley

The Mississippi River Alluvial Plain is an alluvial plain created by the Mississippi River on which lie parts of seven U.S. states, from southern Louisiana to southern Illinois (Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, Lou ...

.

They are first mentioned in French sources of around 1700, when they were centuered around the Grand Village close to present day Natchez, Mississippi

Natchez ( ) is the county seat of and only city in Adams County, Mississippi, United States. Natchez has a total population of 14,520 (as of the 2020 census). Located on the Mississippi River across from Vidalia in Concordia Parish, Louisiana, N ...

. In 1729 the Natchez revolt

The Natchez revolt, or the Natchez massacre, was an attack by the Natchez Native American people on French colonists near present-day Natchez, Mississippi, on November 29, 1729. The Natchez and French had lived alongside each other in the ...

ed, and massacred the French colony of Fort Rosalie, and the French retaliated by destroying all the Natchez villages. The remaining Natchez fled in scattered bands to live among the Chickasaw, Creek and Cherokee, whom they followed on the trail of tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

when Indian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

policies of the mid 19th century forced them to relocate to Oklahoma. The Natchez language was extinct in the 20th century, with the death of the last known native speaker, Nancy Raven

Nancy Raven (also Nancy Taylor) (December 25, 1872 – March 25, 1957) was a Natchez storyteller from Braggs, Oklahoma and one of the last two native speakers of the Natchez language.

Her father was Cherokee and her mother Natchez, and she learne ...

, in 1957.

Maps

Hopewell tradition

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from 1 ...

s

File:Ohio Arch Cultures map HRoe 2008.jpg, Adena culture

The Adena culture was a Pre-Columbian Native American culture that existed from 500 BCE to 100 CE, in a time known as the Early Woodland period. The Adena culture refers to what were probably a number of related Native American societies sharing ...

File:Troyville and Baytown cultures map HRoe 2011.jpg, Troyville culture

The Troyville culture is an archaeological culture in areas of Louisiana and Arkansas in the Lower Mississippi valley in the Southeastern Woodlands. It was a Baytown Period culture and lasted from 400 to 700 CE during the Late Woodland period. It ...

and Baytown culture

The Baytown culture was a Pre-Columbian Native American culture that existed from 300 to 700 CE in the lower Mississippi River Valley, consisting of sites in eastern Arkansas, western Tennessee, Louisiana, and western Mississippi. The Baytown Sit ...

File:Coles Creek culture map HRoe 2010.jpg, Coles Creek culture

Coles Creek culture is a Late Woodland archaeological culture in the Lower Mississippi valley in the Southeastern Woodlands. It followed the Troyville culture. The period marks a significant change in the cultural history of the area. Population i ...

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

File:Caddoan Mississippian culture map HRoe 2010.jpg, Caddoan Mississippian culture

The Caddoan Mississippian culture was a prehistoric Native American culture considered by archaeologists as a variant of the Mississippian culture. The Caddoan Mississippians covered a large territory, including what is now Eastern Oklahoma, Wes ...

File:Fort Ancient Monongahela cultures HRoe 2010.jpg, Fort Ancient culture

Fort Ancient is a name for a Native American culture that flourished from Ca. 1000-1750 CE and predominantly inhabited land near the Ohio River valley in the areas of modern-day southern Ohio, northern Kentucky, southeastern Indiana and western ...

File:Plaquemine culture map HRoe 2010.jpg, Plaquemine culture

The Plaquemine culture was an archaeological culture (circa 1200 to 1700 CE) centered on the Lower Mississippi River valley. It had a deep history in the area stretching back through the earlier Coles Creek (700-1200 CE) and Troyville culture ...

Popular mythology

Alternative scenarios and hoaxes

Based on the idea that the origins of the mound builders lay with a mysterious ancient people, there were various other suggestions belonging to the more general genre ofPre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact theories

Pre-Columbian transoceanic contact theories are speculative theories which propose that possible visits to the Americas, possible interactions with the indigenous peoples of the Americas, or both, were made by people from Africa, Asia, Europe, ...

, specifically involving Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

, Atlantis

Atlantis ( grc, Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, , island of Atlas (mythology), Atlas) is a fictional island mentioned in an allegory on the hubris of nations in Plato's works ''Timaeus (dialogue), Timaeus'' and ''Critias (dialogue), Critias'' ...

, and the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel

The ten lost tribes were the ten of the Twelve Tribes of Israel that were said to have been exiled from the Kingdom of Israel after its conquest by the Neo-Assyrian Empire BCE. These are the tribes of Reuben, Simeon, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Ash ...

, summarised by Feder (2006) under the heading of "The Myth of a Vanished Race".

Benjamin Smith Barton

Benjamin Smith Barton (February 10, 1766 – December 19, 1815) was an American botanist, naturalist, and physician. He was one of the first professors of natural history in the United States and built the largest collection of botanical specime ...

in his ''Observations on Some Parts of Natural History'' (1787) proposed the theory that the Mound Builders were associated with "Danes", i.e. with the Norse colonization of North America

The Norse exploration of North America began in the late 10th century, when Norsemen explored areas of the North Atlantic colonizing Greenland and creating a short term settlement near the northern tip of Newfoundland. This is known now as L'Ans ...

. In 1797, Barton reconsidered his position and correctly identified the mounds as part of indigenous prehistory.

Notable for the association with the Ten Lost Tribes is the Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon is a religious text of the Latter Day Saint movement, which, according to Latter Day Saint theology, contains writings of ancient prophets who lived on the American continent from 600 BC to AD 421 and during an interlude date ...

(1830).

In this narrative, the Jaredite

The Jaredites () are one of four peoples (along with the Nephites, Lamanites, and Mulekites) that the Latter-day Saints believe settled in ancient America.

The Book of Mormon (mainly its Book of Ether) describes the Jaredites as the descendant ...

s (3000–2000 BCE) and an Israelite group in 590 BCE (termed Nephites

According to the Book of Mormon, the Nephites () are one of four groups (along with the Lamanites, Jaredites, and Mulekites) to have settled in the ancient Americas. The term is used throughout the Book of Mormon to describe the religious, po ...

, Lamanites

The Lamanites () are one of the four ancient peoples (along with the Jaredites, the Mulekites, and the Nephites) described as having settled in the ancient Americas in the Book of Mormon, a sacred text of the Latter Day Saint movement. The Lamani ...

, and Mulekites). While the Nephites, Lamanites, and Mulekites were all of Jewish origin coming from Israel around 590 BCE, the Jaradites were a non-Abrahamic people separate in all aspects, except in a belief in Jehovah, from the Nephites. ''The Book of Mormon'' depicts these settlers building magnificent cities, which were destroyed by warfare about CE 385.

The Book of Mormon can be placed in the tradition of the "Mound-Builder literature" of the period. Dahl (1961) states that it is "the most famous and certainly the most influential of all Mound-Builder literature".

Later authors placing the Book of Mormon in this context include Silverberg (1969),

Brodie (1971),

Kennedy (1994) and Garlinghouse (2001).

Some nineteenth-century archaeological finds (e.g., earth and timber fortifications and towns, the use of a plaster-like cement, ancient roads, metal points and implements, copper breastplates, head-plates, textiles, pearls, native North American inscriptions, North American elephant remains etc.) were well-publicized at the time of the publication of the Book of Mormon and there is incorporation of some of these ideas into the narrative. References are made in the Book of Mormon to then-current understanding of pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, th ...

civilizations, including the formative Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. W ...

n civilizations such as the (Pre-Classic) Olmec

The Olmecs () were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization. Following a progressive development in Soconusco, they occupied the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that t ...

, Maya

Maya may refer to:

Civilizations

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Maya language, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (Ethiopia), a populat ...

, and Zapotec.

Lafcadio Hearn

, born Patrick Lafcadio Hearn (; el, Πατρίκιος Λευκάδιος Χέρν, Patríkios Lefkádios Chérn, Irish language, Irish: Pádraig Lafcadio O'hEarain), was an Irish people, Irish-Greeks, Greek-Japanese people, Japanese writer, t ...

in 1876 wrote about a theory that the mounds were built by people from the lost continent of Atlantis.

The Reverend Landon West Landon is a personal name of English origin that means "long hill". It is a variant of Langdon (surname), Langdon. Landon became popular in the United States in the 1990s, and by 2010 had become the 32nd most popular name for boys.Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden ( he, גַּן־עֵדֶן, ) or Garden of God (, and גַן־אֱלֹהִים ''gan-Elohim''), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the Bible, biblical paradise described in Book of Genesis, Genes ...

.

More recently, Black nationalist

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race (human categorization), race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black natio ...

websites claiming association with the Moorish Science Temple of America

The Moorish Science Temple of America is an American national and religious organization founded by Noble Drew Ali (born as Timothy Drew) in the early twentieth century. He based it on the premise that African Americans are descendants of the Moa ...

,

have taken up the Atlantean (" Mu") association of the Mound Builders.

Similarly, the "Washitaw Nation

The Washitaw Nation (''Washitaw de Dugdahmoundyah'') is an African-American group associated with the Moorish Science Temple of America who claim to be a sovereign state of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans within the bounda ...

", a group associated with the Moorish Science Temple of America established in the 1990s, has been associated with mound-building in Black nationalist online articles of the early 2000s.

Kinderhook plates

On April 23, 1843, nine men unearthed human bones and six small, bell-shaped plates in Kinderhook, Illinois. Both sides of the plates apparently contained some sort of ancient writings. The plates, later known as the

On April 23, 1843, nine men unearthed human bones and six small, bell-shaped plates in Kinderhook, Illinois. Both sides of the plates apparently contained some sort of ancient writings. The plates, later known as the Kinderhook plates

The Kinderhook plates are a set of six small, bell-shaped pieces of brass with unusual engravings, created as a hoax in 1843, surreptitiously buried and then dug up at an Native American mound near Kinderhook, Illinois, Kinderhook, Illinois, Unit ...

, were presented to Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

, who was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism

Mormonism is the religious tradition and theology of the Latter Day Saint movement of Restorationist Christianity started by Joseph Smith in Western New York in the 1820s and 1830s. As a label, Mormonism has been applied to various aspects of t ...

. He was reported to have said, "I have translated a portion of them, and find they contain the history of the person with whom they were found. He was a descendant of Ham, through the loins of Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: ''pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the an ...

, king of Egypt, and that he received his kingdom from the Ruler of heaven and earth."

In later letters, two eyewitnesses among the nine people who were present at the excavation of the plates, W. P. Harris and Wilbur Fugate, confessed that the whole thing was a hoax. With a group of other conspirators, they had manufactured the plates to give them the appearance of antiquity, buried them in a mound, and later pretended to excavate them, all for the purpose of trapping Joseph Smith into pretending to translate. However, it was not until 1980, when the only remaining plate was forensically examined, that the plates were conclusively determined to be, in fact, a nineteenth-century production.Up to 1980 most Latter-day Saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

s rejected the confessions and believed the plates were authentic. Not only did skeptics accept the confessors’ statements, but some continue to this day to argue that Joseph Smith pretended to translate a portion of the faked plates, claiming that he could not have been a true prophet.

The purpose for faking the Kinderhook plates is mainly to prove that the book of Mormon is true according to the witness Fulgate, "We learn there was a Mormon present when the plates were found, who it is said, leaped for joy at the discovery, and remarked that it would go to prove the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. The Mormons wanted to take the plates to Joe Smith, but we refused to let them go. Some time afterward a man assuming the name of Savage, of Quincy, borrowed the plates of Wiley to show to his literary friends there, and took them to Joe Smith."

Newark Holy Stone

On June 29, 1860, David Wyrick, the surveyor of Licking County near Newark, discovered the so called Keystone in a shallow excavation at the monumental Newark Earthworks, which is an extraordinary set of ancient geometric enclosures created by Indigenous people. There he dug up a four-sided, plumb-bob-shaped stone with

On June 29, 1860, David Wyrick, the surveyor of Licking County near Newark, discovered the so called Keystone in a shallow excavation at the monumental Newark Earthworks, which is an extraordinary set of ancient geometric enclosures created by Indigenous people. There he dug up a four-sided, plumb-bob-shaped stone with Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

letters engraved on each of its faces. The local Episcopal minister John W. McCarty translated the four inscriptions as "Law of the Lord," “Word of the Lord," “Holy of Holies," and "King of the Earth." Charles Whittlesey, who was one of the foremost archaeologists at that time, pronounced the stone to be authentic. The Newark Holy Stones, if genuine, would provide support for monogenesis, since they would establish that American Indians could be encompassed within Biblical history.

After his first expedition, Wyrick uncovered a small stone box that was found to contain an intricately carved slab of black limestone covered with archaic-looking Hebrew letters along with a representation of a man in flowing robes. When translated, once again by McCarty, the inscription was found to include the entire Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ� ...

, and the robed figure was identified as Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

. Naturally enough, it became known as the Decalogue Stone.

Rather than being found beneath only a foot or two of soil, the Decalogue Stone was claimed to have been buried beneath a forty-foot-tall stone mound. Instead of modern Hebrew typography, the characters on the stone were blocky and appeared to be an ancient form of the Hebrew alphabet. Finally, the stone bore no resemblance to any modern Masonic

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to Fraternity, fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of Stonemasonry, stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their inte ...

artifact. In 1870, Whittlesey declared finally that the Holy Stones and other similar artifacts were "Archaeological Frauds."

Giants

In 19th-century America, a number of popular mythologies surrounding the origin of the mounds were in circulation, typically involving the mounds being built by a race ofgiant

In folklore, giants (from Ancient Greek: '' gigas'', cognate giga-) are beings of human-like appearance, but are at times prodigious in size and strength or bear an otherwise notable appearance. The word ''giant'' is first attested in 1297 fr ...

s.

A ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''article from 1897 described a mound in Wisconsin in which a giant human skeleton measuring over in length was found.

From 1886, another ''New York Times'' article described water receding from a mound in Cartersville, Georgia

Cartersville is a city in Bartow County, Georgia, United States; it is located within the northwest edge of the Atlanta metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 23,187. Cartersville is the county seat of Bartow Coun ...

, which uncovered acres of skulls and bones, some of which were said to be gigantic. Two thigh bones were measured with the height of their owners estimated at .

President Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

made reference to the giants whose bones fill the mounds of America.

The antiquarian author William Pidgeon

William Edwin Pidgeon, aka Bill Pidgeon and Wep, (1909–1981) was an Australian painter who won the Archibald Prize three times. After his death, cartoonist and journalist Les Tanner described him: "He was everything from serious draftsman, b ...

in 1858 created fraudulent surveys of mound groups that did not exist.Pidgeon, William (1858) ''Traditions of Dee-Coo-Dah and Antiquarian Researches''. Horace Thayer, New York.

Beginning in the 1880s, the supposed origin of the earthworks with a race of giants was increasingly recognized as spurious.

Pidgeon's fraudulent claims about the archaeological record was shown to be a hoax by Theodore Lewis in 1886.Lewis, Theodore H. (1886) "The 'Monumental Tortoise' Mounds of 'Dee-Coo-Dah'" ''The American Journal of Archaeology'' 2(1):65–69.

A major factor contributing to public acceptance of the earthworks as a regular part of North American prehistory was the 1894 report by Cyrus Thomas

Cyrus Thomas (July 27, 1825 – June 26, 1910) was an American ethnologist and entomologist prominent in the late 19th century and noted for his studies of the natural history of the American West.

Biography

Thomas was born in Kingsport, ...

of the Bureau of American Ethnology

The Bureau of American Ethnology (or BAE, originally, Bureau of Ethnology) was established in 1879 by an act of Congress for the purpose of transferring archives, records and materials relating to the Indians of North America from the Interior D ...

.

Earlier authors making a similar case include Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, who excavated a mound and from the artifacts and burial practices, noted similarities between mound-builder funeral practices and those of Native Americans in his time.

= Walam Olum

= The Walam Olum hoax had considerable influence on perceptions of the Mound Builders. In 1836,Constantine Samuel Rafinesque

Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz (; October 22, 1783September 18, 1840) was a French 19th-century polymath born near Constantinople in the Ottoman Empire and self-educated in France. He traveled as a young man in the United States, ultimat ...

published his translation of a text he claimed had been written in pictographs on wooden tablets. This text explained that the Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

Indians originated in Asia, told of their passage over the Bering Strait, and narrated their subsequent migration across the North American continent. This "Walam Olum" tells of battles with native peoples already in America before the Lenape arrived. People hearing of the account believed that the "original people" were the Mound Builders, and that the Lenape overthrew them and destroyed their culture. David Oestreicher

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

later asserted that Rafinesque's account was a hoax. He argued that the Walam Olum glyphs derived from Chinese, Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

, and Mayan

Mayan most commonly refers to:

* Maya peoples, various indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Maya civilization, pre-Columbian culture of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Mayan languages, language family spoken ...

alphabets. Meanwhile, the belief that the Native Americans destroyed the mound-builder culture had gained widespread acceptance.

See also

*List of burial mounds in the United States

This is a list of notable burial mounds in the United States built by Native Americans. Burial mounds were built by many different cultural groups over a span of many thousands of years, beginning in the Late Archaic period and continuing through ...

* Petroform

Petroforms, also known as boulder outlines or boulder mosaics, are human-made shapes and patterns made by lining up large rocks on the open ground, often on quite level areas. Petroforms in North America were originally made by various Native A ...

* Prehistory of Ohio

Prehistory of Ohio provides an overview of the activities that occurred prior to Ohio's recorded history. The ancient hunters, Paleo-Indians (13000 B.C. to 7000 B.C.), descended from humans that crossed the Bering Strait. There is evidence of Pa ...

* Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (formerly the Southern Cult), aka S.E.C.C., is the name given to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, iconography, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture. It coincided with their ado ...

* Southwestern Moundbuilders

The Southwestern Moundbuilders are the athletic teams that represent Southwestern College (Kansas), Southwestern College, located in Winfield, Kansas, in intercollegiate sports as a member of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics ...

, athletic teams of Southwestern College in Winfield, Kansas

* Tumulus

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones buil ...

, mounds (or barrows) of Europe and Asia

* Tumulus culture

__NOTOC__

The Tumulus culture (German: ''Hügelgräberkultur'') dominated Central Europe during the Middle Bronze Age ( 1600 to 1300 BC).

It was the descendant of the Unetice culture. Its heartland was the area previously occupied by the U ...

References

Further reading

* * Thomas, Cyrus. ''Report on the mound explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology''. pp. 3–730. Twelfth annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1890–91, by J. W. Powell, Director. XLVIII+742 pp., 42 pls., 344 figs. 1894. *Mark Jarzombek

Mark Jarzombek (born 1954) is a United States-born architectural historian, author and critic. Since 1995 he has taught and served within the History Theory Criticism Section of the Department of Architecture at MIT School of Architecture and Pl ...

, Architecture of First Societies: A Global Perspective, (New York: Wiley & Sons, August 2013)

* Feder, Kenneth L. ''Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology''. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2006.

*

*

External links

Lost Race Myth

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20070205072711/http://www.artisthideout.com/art-of-the-ancients-2/ Artist Hideout, Art of the Ancients

Ancient Monuments Placemarks

*

With Climate Swing, a Culture Bloomed in Americas

(mound builders in Peru)

Science 19 September 1997

(a mound complex in Louisiana at 5400u–5000 years ago)

Bruce Smith video

on the 1880s Smithsonian explorations to determine who built the ancient earthen mounds in eastern North America can be viewed as part of the serie

{{Authority control Pre-Columbian architecture Archaic period in North America Formative period in the Americas Archaeological cultures of North America Pre-Columbian cultures Woodland period Native American history Mounds 4th-millennium BC establishments 16th-century disestablishments in North America Pyramids in North America