Monticello Christian Academy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Monticello ( ) was the primary

Monticello ( ) was the primary

"The Long Shadow of the Plantation."

''Backstory'', #0294, Virginia Humanities, 2019. At Jefferson's direction, he was buried on the grounds, in an area now designated as the Monticello Cemetery. The cemetery is owned by the

, Retrieved December 28, 2010. After Jefferson's death, his daughter

Jefferson added a center hallway and a parallel set of rooms to the structure, more than doubling its area. He removed the second full-height story from the original house and replaced it with a

Jefferson added a center hallway and a parallel set of rooms to the structure, more than doubling its area. He removed the second full-height story from the original house and replaced it with a

After Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, his only official surviving daughter,

After Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, his only official surviving daughter,  In 1923, a private non-profit organization, the

In 1923, a private non-profit organization, the

The original main entrance is through the

The original main entrance is through the

, NBC News, 3 July 2017; accessed 4 February 2018f222-11e6-8d72-263470bf0401_story

''Washington Post'', 18 February 2017; accessed 4 February 2018 The west front (''illustration'') gives the impression of a villa of modest proportions, with a lower floor disguised in the hillside. The north wing includes two guest bedrooms and the dining room. It has a

The main house was augmented by small outlying pavilions to the north and south. A row of outbuildings (dairy, a washhouse, store houses, a small nail factory, a joinery, etc.) and quarters for enslaved laborers (

The main house was augmented by small outlying pavilions to the north and south. A row of outbuildings (dairy, a washhouse, store houses, a small nail factory, a joinery, etc.) and quarters for enslaved laborers (

In 1784,

In 1784,  The house is similar in appearance to

The house is similar in appearance to

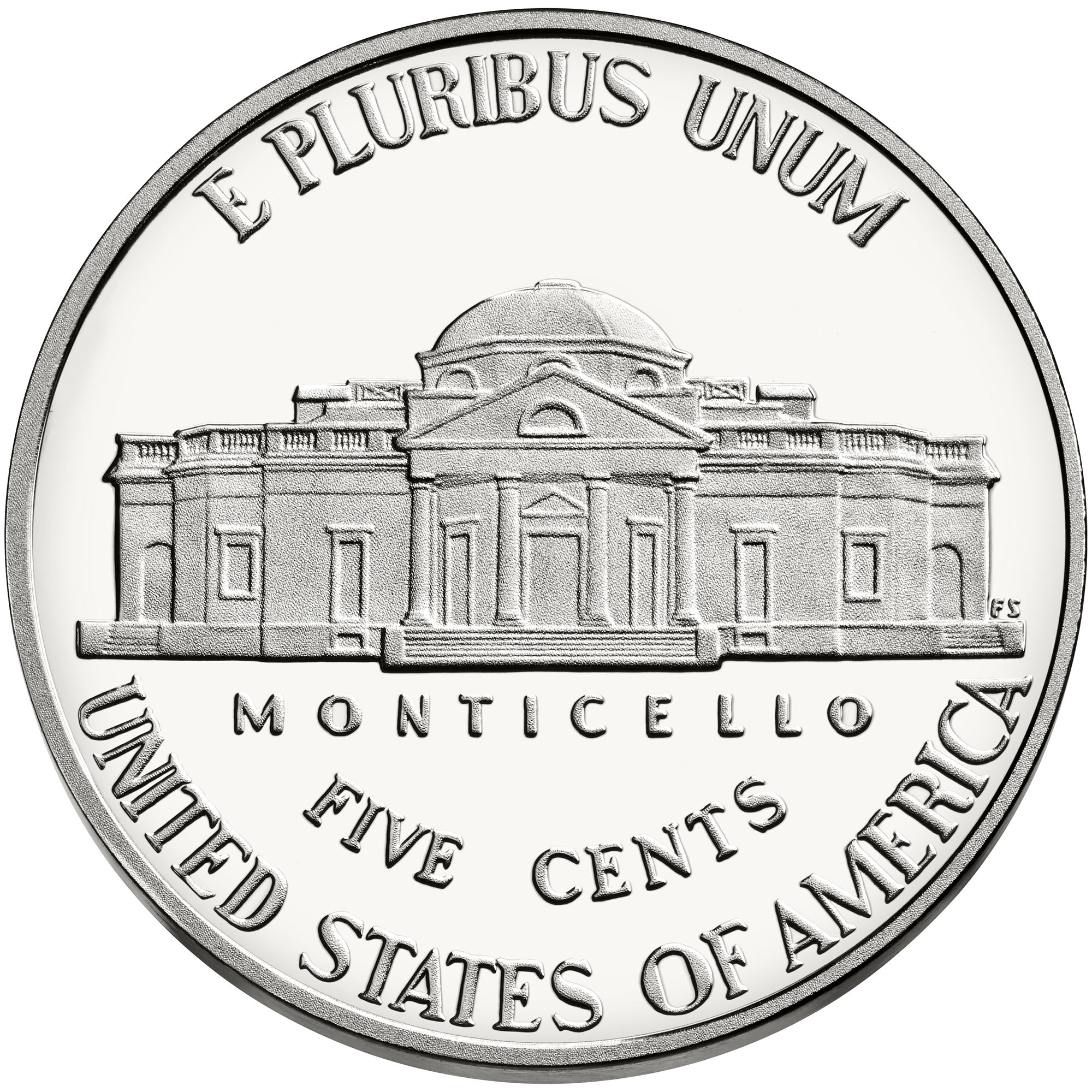

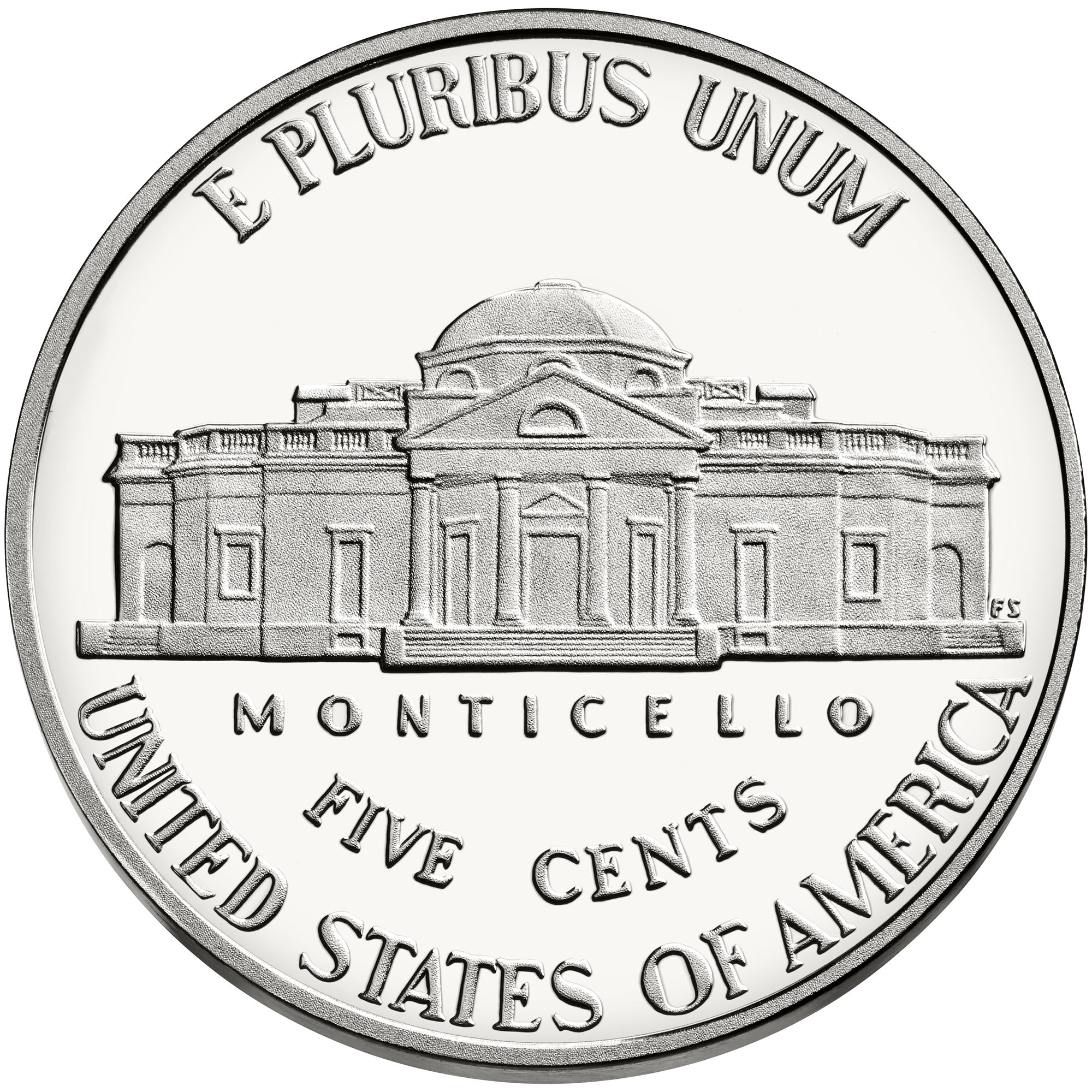

Monticello's image has appeared on U.S. currency and postage stamps. An image of the west front of Monticello by

Monticello's image has appeared on U.S. currency and postage stamps. An image of the west front of Monticello by

File:Monitcello 47MP.jpg, West Front of Monticello

File:Monticello garden.jpg, Vegetable Garden - 180 degrees

File:Monticello visitros center.JPG, The Visitors' Center

File:Monticello real nickel.jpg, Monticello facade and its reproduction on a nickel

File:Nickel Monticello 2003.webmsd.webm, A Nickel by Monticello

File:Monticello_after_Snow_Storm_DSC00074.JPG, Monticello, the day after a snowstorm

File:Montecello-Dome2.jpg, In the dome room, wall detail

File:Montecello-Pavillion2.jpg, Inside the Pavilion at the Vegetable Garden

The Monticello Explorer, an interactive multimedia look at the houseMonticello Association

private lineage society of Jefferson descendants

"Thomas Jefferson Lived Here."

''Popular Mechanics'', August 1954, pp. 97–103/212.

"Life Portrait of Thomas Jefferson"

from

Monticello, State Route 53 vicinity, Charlottesville vicinity, Albemarle, VA

at the

Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello in Google Cultural InstituteGuide to the Monticello Architectural Records 1923-1976

{{authority control Thomas Jefferson Slave cabins and quarters in the United States Museums in Albemarle County, Virginia Jefferson family residences National Historic Landmarks in Virginia Presidential homes in the United States World Heritage Sites in the United States Historic house museums in Virginia Neoclassical architecture in Virginia Plantations in Virginia Plantation houses in Virginia Presidential museums in Virginia Palladian Revival architecture in Virginia Houses in Albemarle County, Virginia Thomas Jefferson buildings Journey Through Hallowed Ground National Heritage Area Historic American Buildings Survey in Virginia National Register of Historic Places in Albemarle County, Virginia Houses on the National Register of Historic Places in Virginia 1772 establishments in Virginia Residential buildings completed in 1772 Rotundas in the United States Tombs of presidents of the United States Articles containing video clips Domes Homes of United States Founding Fathers

plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

of Founding Father

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, the third president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, who began designing Monticello after inheriting land from his father at age 26. Located just outside Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen Cha ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, in the Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

region, the plantation was originally , with Jefferson using the labor of enslaved Africans

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

for extensive cultivation of tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

and mixed crops, later shifting from tobacco cultivation to wheat in response to changing markets. Due to its architectural and historic significance, the property has been designated a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

. In 1987, Monticello and the nearby University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

, also designed by Jefferson, were together designated a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

. The current nickel, a United States coin, features a depiction of Monticello on its reverse side.

Jefferson designed the main house using neoclassical design principles described by Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be one of th ...

and reworking the design through much of his presidency to include design elements popular in late 18th century Europe and integrating numerous ideas of his own. Situated on the summit of an -high peak in the Southwest Mountains

The Southwest Mountains of Virginia are a mountain range centered on Charlottesville, parallel to and geologically associated with the Blue Ridge Mountains, which lie about 30 miles (50 km) to the west. Some of the more prominent peaks inc ...

south of the Rivanna Gap, the name Monticello derives from Italian meaning "little mountain". Along a prominent lane adjacent to the house, Mulberry Row, the plantation came to include numerous outbuildings for specialized functions, e.g., a nailery; quarters for enslaved Africans who worked in the home; gardens for flowers, produce, and Jefferson's experiments in plant breeding—along with tobacco fields and mixed crops. Cabins for enslaved Africans who worked in the fields were farther from the mansion.Freeman, et al, hosts."The Long Shadow of the Plantation."

''Backstory'', #0294, Virginia Humanities, 2019. At Jefferson's direction, he was buried on the grounds, in an area now designated as the Monticello Cemetery. The cemetery is owned by the

Monticello Association

The Monticello Association is a non-profit organization founded in 1913 to care for, preserve, and continue the use of the family graveyard at Monticello, the primary plantation of Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States. The o ...

, a society of his descendants through Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson

Martha Skelton Jefferson (Maiden and married names, ''née'' Wayles; October 30, 1748 – September 6, 1782) was the wife of Thomas Jefferson. She served as First Lady of Virginia during Jefferson's term as Governor of Virginia, governor from 1 ...

.The Monticello Cemetery, Retrieved December 28, 2010. After Jefferson's death, his daughter

Martha Jefferson Randolph

Martha "Patsy" Randolph ( ''née'' Jefferson; September 27, 1772 – October 10, 1836) was the eldest daughter of Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, and his wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson. She was born at Monticel ...

, apart from the small cemetery, sold Monticello. In 1834, it was bought by Uriah P. Levy, a commodore in the U.S. Navy, who admired Jefferson and spent his own money to preserve the property. His nephew Jefferson Monroe Levy

Jefferson Monroe Levy (April 16, 1852 – March 6, 1924) was a three-term U.S. Congressman from New York, a leader of the New York Democratic Party, and a renowned real estate and stock speculator.

In 1879 at the age of 27, he took control o ...

took over the property in 1879; he also invested considerable money to restore and preserve it. In 1923, Monroe Levy sold it to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, originally known as the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, is a private, nonprofit 501(c)(3) corporation founded in 1923 to purchase and maintain Monticello, the primary plantation of Thomas Jefferson, the third ...

(TJF), which operates it as a house museum and educational institution.

Design and building

Jefferson's home was built to serve as aplantation house

A plantation house is the main house of a plantation, often a substantial farmhouse, which often serves as a symbol for the plantation as a whole. Plantation houses in the Southern United States and in other areas are known as quite grand and e ...

, which ultimately took on the architectural form of a villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became s ...

. It has many architectural antecedents, but Jefferson went beyond them to create something very much his own. He consciously sought to create a new architecture for a new nation.''SAH Archipedia'', eds. Gabrielle Esperdy and Karen Kingsley, Charlottesville: UVaP, 2012. Online. http://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/VA-01-CH48 . Accessed 2013-03-16.

Work began on what historians would subsequently refer to as "the first Monticello" in 1768, on a plantation of . Jefferson moved into the South Pavilion (an outbuilding) in 1770, where his new wife Martha Wayles Skelton joined him in 1772. Jefferson continued work on his original design, but how much was completed is of some dispute. In constructing and later reconstructing his home, Jefferson used a combination of free workers, indentured servants and enslaved laborers.

After his wife's death in 1782, Jefferson left Monticello in 1784 to serve as Minister of the United States to France. During his several years in Europe, he had an opportunity to see some of the classical buildings with which he had become acquainted from his reading, as well as to discover the "modern" trends in French architecture that were then fashionable in Paris. His decision to remodel his own home may date from this period. In 1794, following his tenure as the first U.S. Secretary of State (1790–1793), Jefferson began rebuilding his house based on the ideas he had acquired in Europe. The remodeling continued throughout most of his presidency (1801–1809). Although generally completed by 1809, Jefferson continued work on the present structure until his death in 1826.

Jefferson added a center hallway and a parallel set of rooms to the structure, more than doubling its area. He removed the second full-height story from the original house and replaced it with a

Jefferson added a center hallway and a parallel set of rooms to the structure, more than doubling its area. He removed the second full-height story from the original house and replaced it with a mezzanine

A mezzanine (; or in Italian language, Italian, a ''mezzanino'') is an intermediate floor in a building which is partly open to the double-height ceilinged floor below, or which does not extend over the whole floorspace of the building, a loft ...

bedroom floor. The interior is centered on two large rooms, which served as an entrance-hall-museum, where Jefferson displayed his scientific interests, and a music-sitting room. The most dramatic element of the new design was an octagonal dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

, which he placed above the west front of the building in place of a second-story portico. The room inside the dome was described by a visitor as "a noble and beautiful apartment," but it was rarely used—perhaps because it was hot in summer and cold in winter, or because it could be reached only by climbing a steep and very narrow flight of stairs. The dome room has now been restored to its appearance during Jefferson's lifetime, with "Mars yellow

Yellow is the color between green and orange on the spectrum of light. It is evoked by light with a dominant wavelength of roughly 575585 nm. It is a primary color in subtractive color systems, used in painting or color printing. In the R ...

" walls and a painted green and black checkered floor.

Summertime temperatures are high in the region, with indoor temperatures of around . Jefferson himself is known to have been interested in Roman and Renaissance texts about ancient temperature-control techniques such as ground-cooled air and heated floors. Monticello's large central hall and aligned windows were designed to allow a cooling air-current to pass through the house, and the octagonal cupola draws hot air up and out. In the late twentieth century, moderate air conditioning, designed to avoid the harm to the house and its contents that would be caused by major modifications and large temperature differentials, was installed in the house, a tourist attraction.

Before Jefferson's death, Monticello had begun to show signs of disrepair. The attention Jefferson's university project in Charlottesville demanded, and family problems, diverted his focus. The most important reason for the mansion's deterioration was his accumulating debts. In the last few years of Jefferson's life, much went without repair in Monticello. A witness, Samuel Whitcomb Jr.

Samuel Whitcomb Jr. (September 14, 1792 – March 5, 1879) was a colporteur, journalist and a champion of the working class, State Schools, public schools and Democracy, democratic political values. Whitcomb was born in Hanover, Massachusetts, Ha ...

, who visited Jefferson in 1824, thought it run down. He said, "His house is rather old and going to decay; appearances about his yard and hill are rather slovenly. It commands an extensive prospect but it being a misty cloudy day, I could see but little of the surrounding scenery."

Preservation

After Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, his only official surviving daughter,

After Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, his only official surviving daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph

Martha "Patsy" Randolph ( ''née'' Jefferson; September 27, 1772 – October 10, 1836) was the eldest daughter of Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, and his wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson. She was born at Monticel ...

, inherited Monticello. The estate was encumbered with debt and Martha Randolph had financial problems in her own family because of her husband's mental illness

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

. In 1831, she sold Monticello to James Turner Barclay

James Turner Barclay (born May 22, 1807 in King William County, Virginia, † October 20, 1874 in Wheeler, Alabama) was an American missionary and explorer of Palestine.

Life

James Turner Barclay was one of four children of Robert Barclay and Sar ...

, a local apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is a mostly archaic term for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses '' materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons, and patients. The modern chemist (British English) or pharmacist (British and North Ameri ...

. Barclay sold it in 1834 to Uriah P. Levy, the first Jewish commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

(equivalent to today's rear admiral) in the United States Navy. A fifth-generation American whose family first settled in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

, Levy greatly admired Jefferson and used private funds to repair, restore and preserve the house. The Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

government seized the house as enemy property at the outset of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, and sold it to Confederate officer Benjamin Franklin Ficklin. Levy's estate recovered the property after the war.

Levy's heirs argued over his estate, but their lawsuits were settled in 1879, when Uriah Levy's nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy

Jefferson Monroe Levy (April 16, 1852 – March 6, 1924) was a three-term U.S. Congressman from New York, a leader of the New York Democratic Party, and a renowned real estate and stock speculator.

In 1879 at the age of 27, he took control o ...

, a prominent New York lawyer, Real estate speculator

Real estate investing involves the purchase, management and sale or rental of real estate for profit. Someone who actively or passively invests in real estate is called a real estate entrepreneur or a real estate investor. Some investors actively ...

, and stock speculator (and later member of Congress), bought out the other heirs for $10,050, and took control of Monticello. Like his uncle, Jefferson Levy commissioned repairs, restoration and preservation of the grounds and house, which had been deteriorating seriously while the lawsuits wound their way through the courts in New York and Virginia. Together, the Levys preserved Monticello for nearly 100 years.

In 1923, a private non-profit organization, the

In 1923, a private non-profit organization, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, originally known as the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, is a private, nonprofit 501(c)(3) corporation founded in 1923 to purchase and maintain Monticello, the primary plantation of Thomas Jefferson, the third ...

, purchased the house from Jefferson Levy with funds raised by Theodore Fred Kuper and others. They managed additional restoration under architects including Fiske Kimball

Sidney Fiske Kimball (1888 – 1955) was an American architect, architectural historian and museum director. A pioneer in the field of historic preservation, architectural preservation in the United States, he played a leading part in the re ...

and Milton L. Grigg. Since that time, other restoration has been performed at Monticello.

The Jefferson Foundation operates Monticello and its grounds as a house museum

A historic house museum is a house of historic significance that has been transformed into a museum. Historic furnishings may be displayed in a way that reflects their original placement and usage in a home. Historic house museums are held to a v ...

and educational institution. Visitors can wander the grounds, as well as tour rooms in the cellar and ground floor. More expensive tour pass options include sunset hours, as well as tours of the second floor and the third floor, including the iconic dome.

Monticello is a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

. It is the only private home in the United States to be designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

. Included in that designation are the original grounds and buildings of Jefferson's University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

. From 1989 to 1992, a team of architects from the Historic American Buildings Survey

Heritage Documentation Programs (HDP) is a division of the U.S. National Park Service (NPS) responsible for administering the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), and Historic American Landscapes ...

(HABS) created a collection of measured drawings of Monticello. These drawings are held by the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

.

Among Jefferson's other designs are Poplar Forest

Poplar Forest is a plantation and plantation house in Forest, Bedford County, Virginia. Founding Father and third U.S. president Thomas Jefferson designed the plantation, and used the property as both a private retreat and a revenue-generating pl ...

, his private retreat near Lynchburg (which he intended for his daughter Maria, who died at age 25), the "academic village" of the University of Virginia, and the Virginia State Capitol

The Virginia State Capitol is the seat of state government of the Commonwealth of Virginia, located in Richmond, the third capital city of the U.S. state of Virginia. (The first two were Jamestown and Williamsburg.) It houses the oldest elected ...

in Richmond.

Decoration and furnishings

Much of Monticello's interior decoration reflects the personal ideas and ideals of Jefferson. The original main entrance is through the

The original main entrance is through the portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cult ...

on the east front. The ceiling of this portico incorporates a wind plate connected to a weather vane

A wind vane, weather vane, or weathercock is an instrument used for showing the direction of the wind. It is typically used as an architectural ornament to the highest point of a building. The word ''vane'' comes from the Old English word , m ...

, showing the direction of the wind. A large clock

A clock or a timepiece is a device used to measure and indicate time. The clock is one of the oldest human inventions, meeting the need to measure intervals of time shorter than the natural units such as the day, the lunar month and the ...

face on the external east-facing wall has only an hour hand since Jefferson thought this was accurate enough for those he enslaved. The clock reflects the time shown on the "Great Clock", designed by Jefferson, in the entrance hall. The entrance hall contains recreations of items collected by Lewis and Clark

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

on the cross-country expedition commissioned by Jefferson to explore the Louisiana Purchase. Jefferson had the floorcloth painted a "true grass green" upon the recommendation of artist Gilbert Stuart

Gilbert Charles Stuart ( Stewart; December 3, 1755 – July 9, 1828) was an American painter from Rhode Island Colony who is widely considered one of America's foremost portraitists. His best-known work is an unfinished portrait of George Washi ...

, so that Jefferson's "essay in architecture" could invite the spirit of the outdoors into the house.

The south wing includes Jefferson's private suite of rooms. The library holds many books from his third library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

collection. His first library was burned in an accidental plantation fire, and he 'ceded' (or sold) his second library in 1815 to the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

to replace the books lost when the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

burned Washington in 1814. This second library formed the nucleus of the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

.

As "larger than life" as Monticello seems, the house has approximately of living space. Jefferson considered much furniture to be a waste of space, so the dining room

A dining room is a room (architecture), room for eating, consuming food. In modern times it is usually adjacent to the kitchen for convenience in serving, although in medieval times it was often on an entirely different floor level. Historically ...

table was erected only at mealtimes, and beds were built into alcoves cut into thick walls that contain storage space. Jefferson's bed opens to two sides: to his cabinet (study) and to his bedroom (dressing room).

In 2017, a room identified as Sally Hemings

Sarah "Sally" Hemings ( 1773 – 1835) was an enslaved woman with one-quarter African ancestry owned by president of the United States Thomas Jefferson, one of many he inherited from his father-in-law, John Wayles.

Hemings's mother Elizabet ...

' quarters at Monticello, adjacent to Jefferson's bedroom, was discovered in an archeological excavation. It will be restored and refurbished. This is part of the Mountaintop Project, which includes restorations in order to give a fuller account of the lives of both enslaved laborers and free families at Monticello.Michael Cottman, "Historians Uncover Slave Quarters of Sally Hemings at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello", NBC News, 3 July 2017; accessed 4 February 2018f222-11e6-8d72-263470bf0401_story

''Washington Post'', 18 February 2017; accessed 4 February 2018 The west front (''illustration'') gives the impression of a villa of modest proportions, with a lower floor disguised in the hillside. The north wing includes two guest bedrooms and the dining room. It has a

dumbwaiter

A dumbwaiter is a small freight elevator or lift intended to carry food. Dumbwaiters found within modern structures, including both commercial, public and private buildings, are often connected between multiple floors. When installed in restaur ...

incorporated into the fireplace, as well as dumbwaiters (shelved tables on casters) and a pivoting serving door with shelves.

Food and cuisine

Monticello is known as the birthplace of macaroni and cheese in the United States. While it is a myth that Monticello is its American birthplace, it is true that it was made popular there. Jefferson's slave and cookJames Hemings

James Hemings (17651801) was the first American to train as a chef in France. He was African American and born in Virginia in 1765. At 8 years old, he was enslaved by Thomas Jefferson .

He was an older brother of Sally Hemings and a half-sibl ...

brother of Sally Hemings

Sarah "Sally" Hemings ( 1773 – 1835) was an enslaved woman with one-quarter African ancestry owned by president of the United States Thomas Jefferson, one of many he inherited from his father-in-law, John Wayles.

Hemings's mother Elizabet ...

, Jefferson’s mistress, perfected the dish and made it similar to the way it served today.

Quarters for enslaved laborers on Mulberry Row

Jefferson located one set of his quarters for enslaved people on Mulberry Row, a road of slave, service, and industrial structures. Mulberry Row was situated south of Monticello, with the quarters facing the Jefferson mansion. These cabins were occupied by the enslaved Africans who worked in the mansion or in Jefferson's manufacturing ventures, and not by those who labored in the fields. At one point, "Jefferson sketched out plans for a row of substantial, dignified neoclassical houses" for Mulberry Row, for enslaved blacks and white workers, "having in mind an integrated row of residences." Henry Wiencek argues: "It was no small thing to use architecture to make a visible equality of the races."Archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

of the site shows that the rooms of the cabins were much larger in the 1770s than in the 1790s. Researchers disagree as to whether this indicates that more enslaved laborers were crowded into a smaller spaces, or that fewer people lived in the smaller spaces. Earlier houses for enslaved laborers had a two-room plan, one family per room, with a single, shared doorway to the outside. But from the 1790s on, all rooms/families had independent doorways. Most of the cabins are free-standing, single-room structures.

By the time of Jefferson's death, some enslaved families had labored and lived for four generations at Monticello. Thomas Jefferson recorded his strategy for child labor in his Farm Book. Until the age of 10, children served as nurses. When the plantation grew tobacco, children were at a good height to remove and kill tobacco worms from the crops. Once he began growing wheat, fewer people were needed to maintain the crops, so Jefferson established manual trades. He stated that children "go into the ground or learn trades". When girls were 16, they began spinning and weaving textiles. Boys made nails from age 10 to 16. In 1794, Jefferson had a dozen boys working at the nailery. While working at the nailery, boys received more food and may have received new clothes if they did a good job. After the nailery, boys became blacksmiths, coopers, carpenters, or house servants.

Six families and their descendants were featured in the exhibit, ''Slavery at Jefferson's Monticello: Paradox of Liberty'' (January to October 2012) at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History

The National Museum of American History: Kenneth E. Behring Center collects, preserves, and displays the heritage of the United States in the areas of social, political, cultural, scientific, and military history. Among the items on display is t ...

, which also examines Jefferson as an enslaver. Developed as a collaboration between the National Museum of African American History and Culture

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) is a Smithsonian Institution museum located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was established in December 2003 and opened its permanent home in ...

and Monticello, it is the first exhibit on the national mall to address these issues.

In February 2012, Monticello opened a new outdoor exhibit on its grounds: ''Landscape of Slavery: Mulberry Row at Monticello,'' to convey more about the lives of the hundreds of enslaved laborers who lived and worked at the plantation.

Outbuildings and plantation

log cabins

Log most often refers to:

* Trunk (botany), the stem and main wooden axis of a tree, called logs when cut

** Logging, cutting down trees for logs

** Firewood, logs used for fuel

** Lumber or timber, converted from wood logs

* Logarithm, in mathem ...

), known as Mulberry Row, lay nearby to the south. A stone weaver's cottage survives, as does the tall chimney of the joinery, and the foundations of other buildings. A cabin on Mulberry Row was, for a time, the home of Sally Hemings

Sarah "Sally" Hemings ( 1773 – 1835) was an enslaved woman with one-quarter African ancestry owned by president of the United States Thomas Jefferson, one of many he inherited from his father-in-law, John Wayles.

Hemings's mother Elizabet ...

, an enslaved woman who worked in the household who is widely believed to have had a 38-year relationship with the widower Jefferson and to have borne six children by him, four of whom survived to adulthood. The genealogist Helen F.M. Leary concluded that "the chain of evidence securely fastens Sally Hemings's children to their father, Thomas Jefferson." Later Hemings lived in a room in the "south dependency" below the main house.

On the slope below Mulberry Row, African slaves maintained an extensive vegetable garden for Jefferson and the main house. In addition to growing flowers for display and producing crops for eating, Jefferson used the gardens of Monticello

The Gardens of Monticello were gardens first designed by Thomas Jefferson for his plantation Monticello near Charlottesville, Virginia. Jefferson's detailed historical accounts of his 5,000 acres provide much information about the ever-changing c ...

for experimenting with different species. The house was the center of a plantation of tended by some 150 slaves. There are also two houses included in the whole.

Programming

In recent decades, the TJF has created programs to more fully interpret the lives of enslaved people at Monticello. Beginning in 1993, researchers interviewed descendants of Monticello enslaved people for the ''Getting Word Project'', a collection of oral history that provided much new insight into the lives of enslaved people at Monticello and their descendants. (Among findings were that no slaves adopted Jefferson as a surname, but many had their own surnames as early as the 18th century.) New research, publications and training for guides has been added since 2000, when the Foundation's Research Committee concluded it was highly likely that Jefferson had fathered Sally Hemings's children. Some of Mulberry Row has been designated asarcheological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape ...

sites, where excavations and analysis are revealing much about life of enslaved people at the plantation. In the winter of 2000–2001, the enslaved African burial ground at Monticello was discovered. In the fall of 2001, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation held a commemoration of the burial ground, in which the names of known enslaved people of Monticello were read aloud. Additional archeological work is providing information about African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

burial practices.

In 2003 Monticello welcomed a reunion of descendants of Jefferson from both the Wayles's and Hemings's sides of the family. It was organized by the descendants, who have created a new group called the Monticello Community. Additional and larger reunions have been held.

Land purchase

In 2004, the trustees acquired Mountaintop Farm (also known locally as Patterson's or Brown's Mountain), the only property that overlooks Monticello. Jefferson had called the taller mountain Montalto. To prevent development of new homes on the site, the trustees spent $15 million to purchase the property. Jefferson had owned it as part of his plantation, but it was sold off after his death. In the 20th century, its farmhouses were divided into apartments for manyUniversity of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

students. The officials at Monticello had long considered the property an eyesore, and planned to acquire it when it became available.

Architecture

In 1784,

In 1784, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

left America to travel and explore the streets of France, which influenced his taste in architecture. He was mainly influenced by the neoclassical style commonly seen in French architecture, which is the reason the Monticello is designed in a classical revival style.

Jefferson had also been interested in the Pantheon

Pantheon may refer to:

* Pantheon (religion), a set of gods belonging to a particular religion or tradition, and a temple or sacred building

Arts and entertainment Comics

*Pantheon (Marvel Comics), a fictional organization

* ''Pantheon'' (Lone S ...

, even though he was never able to make the trip to Rome to see it in person. Not only did the temple's facade influence the Monticello, but also the Rotunda, which is a library found at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

. Both buildings have a temple like front replicating the Pantheon facade with large structural columns. This building front is also similar to the Palladian. The back side of the buildings also pays tribute to the Roman temple. Jefferson did this by including a dome shape behind the temple front. After Jefferson resigned from Washington's cabinet, he chose to remodel portions of the Monticello. This time he was greatly influenced by the Hôtel de Salm

Salm may refer to

People

* Constance de Salm (1767–1845), poet and miscellaneous writer; through her second marriage, she became Princess of Salm-Dyck

* Salm ibn Ziyad, an Umayyad governor of Khurasan and Sijistan

* House of Salm, a European ...

in Paris.

The house is similar in appearance to

The house is similar in appearance to Chiswick House

Chiswick House is a Neo-Palladian style villa in the Chiswick district of London, England. A "glorious" example of Neo-Palladian architecture in west London, the house was designed and built by Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington (1694–1753 ...

, a Neoclassical house inspired by the architect Andrea Palladio built in 1726–1729 in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

.

Representation in other media

Monticello was featured in Bob Vila'sA&E Network

A&E is an American basic cable network, the flagship television property of A&E Networks. The network was originally founded in 1984 as the Arts & Entertainment Network, initially focusing on fine arts, documentaries, television drama, dramas, and ...

production, ''Guide to Historic Homes of America,'' in a tour which included Honeymoon Cottage and the Dome Room, which is open to the public during a limited number of tours each year.

Replicas

In 2014, Prestley Blake constructed a replica of Monticello inSomers, Connecticut

Somers is a town in Tolland County, Connecticut. The population was 10,255 at the 2020 census. The town center is listed by the U.S. Census Bureau as a census-designated place (CDP). In 2007, ''Money Magazine'' listed Somers 53rd on its "100 Bes ...

. It can be seen on Rte 186 also known as Hall Hill Rd.

The entrance pavilion of the Naval Academy Jewish Chapel

Commodore Uriah P. Levy Center and Jewish Chapel is the Jewish chapel at the United States Naval Academy, in Annapolis, Maryland.

The center is named in honor of Commodore Uriah P. Levy (1792–-1862), the first Jewish commodore in the United ...

at Annapolis is modeled on Monticello.

Chamberlin Hall at Wilbraham & Monson Academy

Wilbraham & Monson Academy (WMA) is a college-preparatory school located in Wilbraham, Massachusetts. Founded in 1804, it is a four-year boarding and day high school for students in Grades 9-12 and postgraduate. A middle school, with Grades 6–8 ...

in Wilbraham, Massachusetts

Wilbraham is a town in Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States. It is a suburb of the City of Springfield, and part of the Springfield Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 14,613 at the 2020 census.

Part of the town comprises ...

, built in 1962 and modeled on Monticello, serves as the location of the Academy's Middle School.

Completed in August 2015, Dallas Baptist University

Dallas Baptist University (DBU) is a Christian liberal arts university in Dallas, Texas. Founded in 1898 as Decatur Baptist College, Dallas Baptist University currently operates campuses in Dallas, Plano, and Hurst.

History

Dallas Baptist Uni ...

built one of the largest replicas of Monticello, including its entry halls and a dome room. Approximately , it is the home of the Gary Cook School of Leadership, as well as the University Chancellor's offices.

Saint Paul's Baptist Church located at the corner of E Belt Boulevard and Hull Street Road in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

is modeled after Monticello. Originally built by Weatherford Memorial Baptist Church, the building was donated to St Paul's when Weatherford Memorial ran out of money and disbanded in the early 2000s.

Pi Kappa Alpha

Pi Kappa Alpha (), commonly known as PIKE, is a college fraternity founded at the University of Virginia in 1868. The fraternity has over 225 chapters and colonies across the United States and abroad with over 15,500 undergraduate members over 30 ...

's Memorial Headquarters, opened in 1988 is located in the TPC Southwind

TPC Southwind is a private golf club in Shelby County, Tennessee, southern United States, located within the gated community of Southwind in Southeast Memphis.

East-southeast of central Memphis, the 18-hole championship golf course was designed ...

development in Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mos ...

and was inspired by the architecture of Monticello.

Legacy

Monticello's image has appeared on U.S. currency and postage stamps. An image of the west front of Monticello by

Monticello's image has appeared on U.S. currency and postage stamps. An image of the west front of Monticello by Felix Schlag

Felix Oscar Schlag (September 4, 1891 – March 9, 1974) was a German born American sculptor who was the designer of the United States five cent coin in use from 1938 to 2004.

He was born to Karl and Teresa Schlag in Frankfurt, Germany wher ...

has been featured on the reverse

Reverse or reversing may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Reverse'' (Eldritch album), 2001

* ''Reverse'' (2009 film), a Polish comedy-drama film

* ''Reverse'' (2019 film), an Iranian crime-drama film

* ''Reverse'' (Morandi album), 2005

* ''Reverse'' ...

of the nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow to ...

minted

Minted is an online marketplace of premium design goods created by independent artists and designers. The company sources art and design from a community of more than 16,000 independent artists from around the world. Minted offers artists two bus ...

since 1938 (with a brief interruption in 2004 and 2005, when designs of the Westward Journey series appeared instead). It was also used as the title for the 2015 play ''Jefferson's Garden

''Jefferson's Garden'' is a 2015 play by Timberlake Wertenbaker. It premiered at the Watford Palace Theatre from 5 to 21 February 2015, with Jefferson played by William Hope. It begins in the 1750s, but is centred on the period from 1776 to the ea ...

'', which centred on his life.

Monticello also appeared on the reverse of the two-dollar bill from 1928 to 1966, when the bill was discontinued. The current bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Plac ...

was introduced in 1976 and retains Jefferson's portrait on the obverse but replaced Monticello on the reverse with an engraved modified reproduction of John Trumbull

John Trumbull (June 6, 1756November 10, 1843) was an American artist of the early independence period, notable for his historical paintings of the American Revolutionary War, of which he was a veteran. He has been called the "Painter of the Rev ...

's 1818 painting ''Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

''. The gift shop at Monticello hands out two-dollar bills as change.

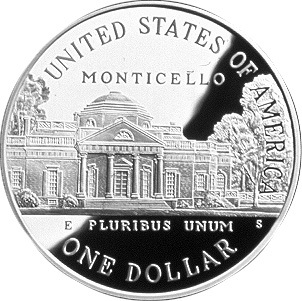

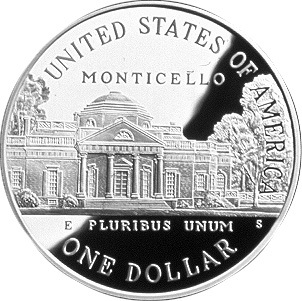

The 1994 commemorative Thomas Jefferson 250th Anniversary silver dollar

The Thomas Jefferson 250th Anniversary silver dollar is a commemorative silver dollar issued by the United States Mint in 1994.

See also

* List of United States commemorative coins and medals (1990s)

* United States commemorative coins

The Unit ...

features Monticello on the reverse.

Gallery

See also

*Bibliography of Thomas Jefferson

This bibliography of works on Thomas Jefferson is a comprehensive list of published works about Thomas Jefferson, the primary author of the Declaration of Independence and the third president of the United States. Biographical and political accou ...

*Jeffersonian architecture

Jeffersonian architecture is an American form of Neo-Classicism and/or Neo-Palladianism embodied in the architectural designs of U.S. President and polymath Thomas Jefferson, after whom it is named. These include his home (Monticello), his retrea ...

*List of residences of presidents of the United States

Listed below are the private residences of the various presidents of the United States. For a list of official residences, see President of the United States § Residence.

Private homes of the presidents

This is a list of homes where p ...

*History of early modern period domes

Domes built in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries relied primarily on empirical techniques and oral traditions rather than the architectural treatises of the time, but the study of dome structures changed radically due to developments in mathemati ...

*People from Monticello

A person ( : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of propert ...

References

Further reading

*Adams, William Howard, ''Jefferson's Monticello'' (Abbeville Press, 1983) *Burstein, Andrew, ''Jefferson's Secrets: Death and Desire in Monticello'' (Basic Books, 2005) *Hatch, Peter J., ''A Rich Spot of Earth: Thomas Jefferson's Revolutionary Garden at Monticello'' (Yale University Press, 2012) *Hayes, Kevin J., ''The Road to Monticello: The Life and Mind of Thomas Jefferson'' (Oxford University Press, 2008) *Jackson, Donald, ''Thomas Jefferson and the Stony Mountains: Exploring the West from Monticello'' (University of Illinois Press, 1981) *Kranish, Michael, ''Flight from Monticello: Thomas Jefferson at War'' (Oxford University Press, 2010) *McCullough, David

David Gaub McCullough (; July 7, 1933 – August 7, 2022) was an American popular historian. He was a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. In 2006, he was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United State ...

(intro.), ''Thomas Jefferson's Monticello: An Intimate Portrait'' (The Monacelli Press, 1997) - photos by Robert C. Lautman Robert Clayton Lautman (November 8, 1923 - October 20, 2009) was an American architectural photographer.

Born in Butte, Montana, his first photographs were made with a box camera for his junior high school yearbook. After attending Montana State ...

*McLaughlin, Jack, ''Jefferson and Monticello: The Biography of a Builder'' (Henry Holt & Co., 1988)

*Stein, Susan R., ''The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello'' (Harry N. Abrams, 1993)

External links

*The Monticello Explorer, an interactive multimedia look at the house

private lineage society of Jefferson descendants

"Thomas Jefferson Lived Here."

''Popular Mechanics'', August 1954, pp. 97–103/212.

"Life Portrait of Thomas Jefferson"

from

C-SPAN

Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN ) is an American cable and satellite television network that was created in 1979 by the cable television industry as a nonprofit public service. It televises many proceedings of the United States ...

's '' American Presidents: Life Portraits'', broadcast from Monticello, April 2, 1999Monticello, State Route 53 vicinity, Charlottesville vicinity, Albemarle, VA

at the

Historic American Buildings Survey

Heritage Documentation Programs (HDP) is a division of the U.S. National Park Service (NPS) responsible for administering the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), and Historic American Landscapes ...

(HABS)Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello in Google Cultural Institute

{{authority control Thomas Jefferson Slave cabins and quarters in the United States Museums in Albemarle County, Virginia Jefferson family residences National Historic Landmarks in Virginia Presidential homes in the United States World Heritage Sites in the United States Historic house museums in Virginia Neoclassical architecture in Virginia Plantations in Virginia Plantation houses in Virginia Presidential museums in Virginia Palladian Revival architecture in Virginia Houses in Albemarle County, Virginia Thomas Jefferson buildings Journey Through Hallowed Ground National Heritage Area Historic American Buildings Survey in Virginia National Register of Historic Places in Albemarle County, Virginia Houses on the National Register of Historic Places in Virginia 1772 establishments in Virginia Residential buildings completed in 1772 Rotundas in the United States Tombs of presidents of the United States Articles containing video clips Domes Homes of United States Founding Fathers