Mohenjo-daro on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Mohenjo-Daro (archaeological site, Pakistan) on Encyclopedia Britannica website

Retrieved 25 November 2019 ur, ) is an archaeological site in the province of

Mohenjo-daro is located off the right (west) bank of the lower

Mohenjo-daro is located off the right (west) bank of the lower

Retrieved 2 May 2012. It was one of the largest cities of the ancient

The ruins of the city remained undocumented for around 3,700 years until

The ruins of the city remained undocumented for around 3,700 years until

Mohenjo-daro has a planned layout with rectilinear buildings arranged on a

Mohenjo-daro has a planned layout with rectilinear buildings arranged on a

In 1950, Sir Mortimer Wheeler identified one large building in Mohenjo-daro as a "Great Granary". Certain wall-divisions in its massive wooden superstructure appeared to be grain storage-bays, complete with air-ducts to dry the grain. According to Wheeler, carts would have brought grain from the countryside and unloaded them directly into the bays. However,

In 1950, Sir Mortimer Wheeler identified one large building in Mohenjo-daro as a "Great Granary". Certain wall-divisions in its massive wooden superstructure appeared to be grain storage-bays, complete with air-ducts to dry the grain. According to Wheeler, carts would have brought grain from the countryside and unloaded them directly into the bays. However,

Mohenjo-daro had no series of city walls, but was fortified with guard towers to the west of the main settlement, and defensive fortifications to the south. Considering these fortifications and the structure of other major

Mohenjo-daro had no series of city walls, but was fortified with guard towers to the west of the main settlement, and defensive fortifications to the south. Considering these fortifications and the structure of other major

Civilization and Floods in the Indus Valley

, ''Expedition Magazine'', July 1965. For some archaeologists, it was believed that a final flood that helped engulf the city in a sea of mud brought about the abandonment of the site.

A

A

In 1927, a seated male

In 1927, a seated male

Preservation work for Mohenjo-daro was suspended in December 1996 after funding from the Pakistani government and international organizations stopped. Site conservation work resumed in April 1997, using funds made available by the UNESCO. The 20-year funding plan provided $10 million to protect the site and standing structures from

Preservation work for Mohenjo-daro was suspended in December 1996 after funding from the Pakistani government and international organizations stopped. Site conservation work resumed in April 1997, using funds made available by the UNESCO. The 20-year funding plan provided $10 million to protect the site and standing structures from

BBC. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

Mohenjo-Daro and the Civilization of Ancient India with References to Agriculture

'. Calcutta: W. Newman & Co, 1937. * Mackay, E. J. H., ed. (1937). ''Further Excavations At Mohenjo-daro: Being an official account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro carried out by the Government of India between the years 1927 and 1931''. *

Volume I

*

Volume II

* Marshall, John Hubert, ed. (1931). ''Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an official account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro carried out by the Government of India between the years 1922 and 1927''. Arthur Probsthain *

Volume I

*

Volume II

*

Volume III

* McIntosh, Jane (2008). ''The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives''. ABC-CLIO, 2008. *Singh, Kavita, "The Museum Is National", Chapter 4 in: Mathur, Saloni and Singh, Kavita (eds), ''No Touching, No Spitting, No Praying: The Museum in South Asia'', 2015, Routledge

PDF on academia.edu

(nb this is different to the article by the same author with the same title in ''India International Centre Quarterly'', vol. 29, no. 3/4, 2002, pp. 176–196

JSTOR

which does not mention this work)

Official website of Mohenjodaro

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

103 Slide Tour and Essay on Mohenjo-daro by Dr. J.M. Kenoyer

{{Authority control History of Sindh Populated places established in the 3rd millennium BC Indus Valley civilisation sites World Heritage Sites in Pakistan Archaeological sites in Pakistan Bronze Age Asia Ancient history of Pakistan Larkana District Ruins in Pakistan Former populated places in Pakistan 1922 archaeological discoveries Tourist attractions in Sindh World Heritage Sites in Sindh 26th-century BC establishments 2nd-millennium BC disestablishments Lost cities and towns

Retrieved 25 November 2019 ur, ) is an archaeological site in the province of

Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

. Built around 2500 BCE, it was the largest settlement of the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

, and one of the world's earliest major cities

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

, contemporaneous with the civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, Minoan Crete

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450B ...

, and Norte Chico. With an estimated population of at least 40,000 people, Mohenjo-daro prospered until around 1700 BCE.

Mohenjo-daro was abandoned in the 19th century BCE as the Indus Valley Civilization declined, and the site was not rediscovered until the 1920s. Significant excavation has since been conducted at the site of the city, which was designated a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

in 1980, the first site in South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

to be so designated. The site is currently threatened by erosion and improper restoration.

Etymology

The city's original name is unknown. Based on his analysis of a Mohenjo-daro seal,Iravatham Mahadevan

Iravatham Mahadevan (2 October 1930 – 26 November 2018) was an Indian epigraphist and civil servant, known for his decipherment of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions and for his expertise on the epigraphy of the Indus Valley civilisation.

Early life

...

speculates that the city's ancient name could have been ''Kukkutarma'' ("the city '-rma''of the cockerel

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domestication, domesticated junglefowl species, with attributes of wild species such as the grey junglefowl, grey and the Ceylon junglefowl that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster ...

'kukkuta''). Cock-fighting

A cockfight is a blood sport, held in a ring called a cockpit. The history of raising fowl for fighting goes back 6,000 years. The first documented use of the ''word'' gamecock, denoting use of the cock as to a "game", a sport, pastime or ente ...

may have had ritual and religious significance for the city. Mohenjo-daro may also have been a point of diffusion for the clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

of the domesticated chicken found in Africa, Western Asia, Europe and the Americas.

Mohenjo-daro, the modern name for the site, has been interpreted as "Mound of the Dead Men" in Sindhi.

Location

Mohenjo-daro is located off the right (west) bank of the lower

Mohenjo-daro is located off the right (west) bank of the lower Indus river

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

in Larkana District

Larkana District (Sindhi language, Sindhi: ضلعو لاڙڪاڻو; ur, ) is a district of Sindh province of Pakistan. Its main city is Larkana on the banks of the Indus River. It is home district the of influential Bhutto family. The Larkana B ...

, Sindh, Pakistan. It lies on a Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

ridge in the flood plain of the Indus, around from the town of Larkana

Larkana ( ur, , translit=lāṛkāna; sd, لاڙڪاڻو, translit=lāṛkāṇo) is a city located in the Sindh province of Pakistan. It is the 15th largest city of Pakistan by population. It is home to the Indus Valley civilization site Moh ...

.

Historical context

Mohenjo-daro was built in the 26th century BCE.Ancientindia.co.uk.Retrieved 2 May 2012. It was one of the largest cities of the ancient

Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

, also known as the Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

n Civilization, which developed around 3,000 BCE from the prehistoric Indus culture. At its height, the Indus Civilization spanned much of what is now Pakistan and North India, extending westwards to the Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

ian border, south to Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the ninth ...

in India and northwards to an outpost in Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

, with major urban centers at Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Lothal

Lothal () was one of the southernmost sites of the ancient Indus Valley civilisation, located in the Bhāl region of the modern state of Gujarāt. Construction of the city is believed to have begun around 2200 BCE.

Archaeological Survey of ...

, Kalibangan

Kalibangān is a town located at on the left or southern banks of the Ghaggar (Ghaggar-Hakra River) in Tehsil Pilibangān, between Suratgarh and Hanumangarh in Hanumangarh District, Rajasthan, India 205 km. from Bikaner. It is also identifi ...

, Dholavira

Dholavira ( gu, ધોળાવીરા) is an archaeological site at Khadirbet in Bhachau Taluka of Kutch District, in the state of Gujarat in western India, which has taken its name from a modern-day village south of it. This village is f ...

and Rakhigarhi

Rakhigarhi or Rakhi Garhi is a village and an archaeological site belonging to the Indus Valley civilisation in Hisar District of the northern Indian state of Haryana, situated about 150 km northwest of Delhi. It was part of the mature pha ...

. Mohenjo-daro was the most advanced city of its time, with remarkably sophisticated civil engineering and urban planning. When the Indus civilization went into sudden decline around 1900 BCE, Mohenjo-daro was abandoned.

Rediscovery and excavation

The ruins of the city remained undocumented for around 3,700 years until

The ruins of the city remained undocumented for around 3,700 years until R. D. Banerji

Rakhal Das Banerji, also Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay (12 April 1885 – 23 May 1930), was an Indian archaeologist and an officer of the Archeological Survey of India (ASI). In 1919, he became the second ASI officer deputed to survey the site of ...

, an officer of the Archaeological Survey of India

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an Indian government agency that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural historical monuments in the country. It was founded in 1861 by Alexande ...

, visited the site in 1919–20 identifying what he thought to be a Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circumamb ...

(150–500 CE) known to be there and finding a flint scraper which convinced him of the site's antiquity. This led to large-scale excavations of Mohenjo-daro led by K. N. Dikshit

Rao Bahadur Kashinath Narayan Dikshit (21 October 1889 – 12 August 1946) was an Indian archaeologist who served as Director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) from 1937 to 1944.

Early life and education

Dikshit was born ...

in 1924–25, and John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

in 1925–26. In the 1930s major excavations were conducted at the site under the leadership of Marshall, D. K. Dikshitar and Ernest Mackay

Ernest is a given name derived from Germanic word ''ernst'', meaning "serious". Notable people and fictional characters with the name include:

People

* Archduke Ernest of Austria (1553–1595), son of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor

* Ernest, ...

. Further excavations were carried out in 1945 by Mortimer Wheeler

Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler CH CIE MC TD (10 September 1890 – 22 July 1976) was a British archaeologist and officer in the British Army. Over the course of his career, he served as Director of both the National Museum of Wales an ...

and his trainee, Ahmad Hasan Dani

Ahmad Hassan Dani (Urdu: احمد حسن دانی) FRAS, SI, HI (20 June 1920 – 26 January 2009) was a Pakistani archaeologist, historian, and linguist. He was among the foremost authorities on Central Asian and South Asian archaeology ...

. The last major series of excavations were conducted in 1964 and 1965 by George F. Dales George Franklin Dales Jr. (August 13, 1927 – April 25, 1992), was an archaeology professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and later the University of California, Berkeley, where he chaired the South and Southeast Asian Studies department. ...

. After 1965 excavations were banned due to weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs ''in situ'' (on site, with little or no movement), ...

damage to the exposed structures, and the only projects allowed at the site since have been salvage excavations, surface surveys, and conservation projects. In the 1980s, German and Italian survey groups led by Michael Jansen and Maurizio Tosi used less invasive archeological techniques, such as architectural documentation, surface surveys, and localized probing, to gather further information about Mohenjo-daro. A dry core drilling conducted in 2015 by Pakistan's National Fund for Mohenjo-daro revealed that the site is larger than the unearthed area.

Architecture and urban infrastructure

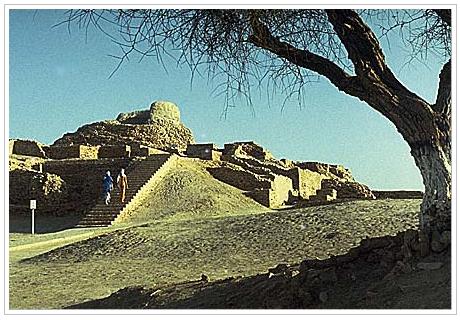

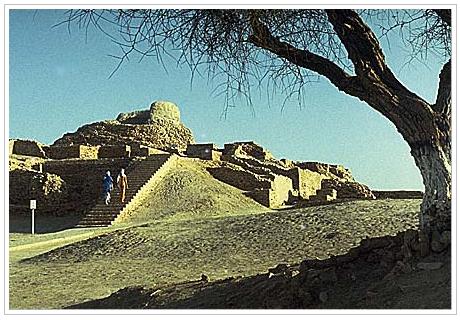

Mohenjo-daro has a planned layout with rectilinear buildings arranged on a

Mohenjo-daro has a planned layout with rectilinear buildings arranged on a grid plan

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogona ...

. Most were built of fired and mortared brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

; some incorporated sun-dried mud-brick

A mudbrick or mud-brick is an air-dried brick, made of a mixture of loam, mud, sand and water mixed with a binding material such as rice husks or straw. Mudbricks are known from 9000 BCE, though since 4000 BCE, bricks have also been fi ...

and wooden superstructures. The covered area of Mohenjo-daro is estimated at 300 hectare

The hectare (; SI symbol: ha) is a non-SI metric unit of area equal to a square with 100-metre sides (1 hm2), or 10,000 m2, and is primarily used in the measurement of land. There are 100 hectares in one square kilometre. An acre is a ...

s. The ''Oxford Handbook of Cities in World History'' offers a "weak" estimate of a peak population of around 40,000.

The sheer size of the city, and its provision of public buildings and facilities, suggests a high level of social organization. The city is divided into two parts, the so-called Citadel and the Lower City. The Citadel – a mud-brick mound around high – is known to have supported public baths, a large residential structure designed to house about 5,000 citizens, and two large assembly halls. The city had a central marketplace, with a large central well. Individual households or groups of households obtained their water from smaller wells. Waste water was channeled to covered drains that lined the major streets. Some houses, presumably those of more prestigious inhabitants, include rooms that appear to have been set aside for bathing, and one building had an underground furnace (known as a hypocaust

A hypocaust ( la, hypocaustum) is a system of central heating in a building that produces and circulates hot air below the floor of a room, and may also warm the walls with a series of pipes through which the hot air passes. This air can warm th ...

), possibly for heated bathing. Most houses had inner courtyards, with doors that opened onto side-lanes. Some buildings had two stories.

Major buildings

Jonathan Mark Kenoyer

Jonathan Mark Kenoyer (born 28 May 1952, in Shillong, India) is an American archaeologist and ''George F. Dales Jr. & Barbara A. Dales'' Professor of Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He earned his Bachelor of Arts, Master' ...

noted the complete lack of evidence for grain at the "granary", which, he argued, might therefore be better termed a "Great Hall" of uncertain function.Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1998). “Indus Cities, Towns and Villages”, ''Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization''. Islamabad

Islamabad (; ur, , ) is the capital city of Pakistan. It is the country's ninth-most populous city, with a population of over 1.2 million people, and is federally administered by the Pakistani government as part of the Islamabad Capital T ...

: American Institute of Pakistan Studies. p. 65. Close to the "Great Granary" is a large and elaborate public bath, sometimes called the Great Bath

The Great Bath is one of the best-known structures among the ruins of the Harappan Civilization excavated at Mohenjo-daro in Sindh, Pakistan.

. From a colonnaded courtyard, steps lead down to the brick-built pool, which was waterproofed by a lining of bitumen

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term a ...

. The pool measures long, wide and deep. It may have been used for religious purification. Other large buildings include a "Pillared Hall", thought to be an assembly hall of some kind, and the so-called "College Hall", a complex of buildings comprising 78 rooms, thought to have been a priestly residence.

Fortifications

Mohenjo-daro had no series of city walls, but was fortified with guard towers to the west of the main settlement, and defensive fortifications to the south. Considering these fortifications and the structure of other major

Mohenjo-daro had no series of city walls, but was fortified with guard towers to the west of the main settlement, and defensive fortifications to the south. Considering these fortifications and the structure of other major Indus valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

cities like Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

, it is postulated that Mohenjo-daro was an administrative center. Both Harappa and Mohenjo-daro share relatively the same architectural layout, and were generally not heavily fortified like other Indus Valley sites. It is obvious from the identical city layouts of all Indus sites that there was some kind of political or administrative centrality, but the extent and functioning of an administrative center remains unclear.

Water supply and wells

The location of Mohenjo-daro was built in a relatively short period of time, with the water supply system and wells being some of the first planned constructions. With the excavations done so far, over 700 wells are present at Mohenjo-daro, alongside drainage and bathing systems. This number is unheard of when compared to other civilizations at the time, such as Egypt or Mesopotamia, and the quantity of wells transcribes as one well for every three houses. Because of the large number of wells, it is believed that the inhabitants relied solely on annual rainfall, as well as the Indus River's course remaining close to the site, alongside the wells providing water for long periods of time in the case of the city coming under siege. Due to the period in which these wells were built and used, it is likely that the circular brick well design used at this and many other Harappan sites are an invention that should be credited to the Indus civilization, as there is no existing evidence of this design from Mesopotamia or Egypt at this time, and even later. Sewage and waste water for buildings at the site were disposed of via a centralized drainage system that ran alongside the site's streets. These drains that ran alongside the road were effective at allowing most human waste and sewage to be disposed of as the drains most likely took the waste toward the Indus River.Flooding and rebuilding

The city also had large platforms perhaps intended as defense against flooding.McIntosh (2008), p. 389. "The enormous amount of labor involved in the creation of Mohenjo-daro's flood defense platforms (calculated at around 4 million man-days) indicates the existence of an authority able to plan the construction and to mobilize and feed the requisite labor force." According to a theory first advanced by Wheeler, the city could have been flooded and silted over, perhaps six times, and later rebuilt in the same location.George F. Dales George Franklin Dales Jr. (August 13, 1927 – April 25, 1992), was an archaeology professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and later the University of California, Berkeley, where he chaired the South and Southeast Asian Studies department. ...

,Civilization and Floods in the Indus Valley

, ''Expedition Magazine'', July 1965. For some archaeologists, it was believed that a final flood that helped engulf the city in a sea of mud brought about the abandonment of the site.

Gregory Possehl Gregory Louis Possehl (July 21, 1941 – October 8, 2011) was a professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania and curator of the Asian Collections at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. H ...

was the first to theorize that the floods were caused by overuse and expansion upon the land, and that the mud flood was not the reason the site was abandoned. Instead of a mud flood wiping part of the city out in one fell swoop, Possehl coined the possibility of constant mini-floods throughout the year, paired with the land being worn out by crops, pastures, and resources for bricks and pottery spelled the downfall of the site.

Notable artefacts

Numerous objects found in excavation include seated and standing figures, copper and stone tools, carvedseals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

, balance-scales and weights, gold and jasper

Jasper, an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases,Kostov, R. I. 2010. Review on the mineralogical systematics of jasper and related rocks. – Archaeometry Workshop, 7, 3, 209-213PDF/ref> ...

jewellery, and children's toys. Many bronze and copper pieces, such as figurines and bowls, have been recovered from the site, showing that the inhabitants of Mohenjo-daro understood how to utilize the lost wax technique

Lost-wax casting (also called "investment casting", "precision casting", or ''cire perdue'' which has been adopted into English from the French, ) is the process by which a duplicate metal sculpture (often silver, gold, brass, or bronze) i ...

. The furnaces found at the site are believed to have been used for copperworks and melting the metals as opposed to smelting. There even seems to be an entire section of the city dedicated to shell-working, located in the northeastern part of the site. Some of the most prominent copperworks recovered from the site are the copper tablets which have examples of the untranslated Indus script

The Indus script, also known as the Harappan script, is a corpus of symbols produced by the Indus Valley Civilisation. Most inscriptions containing these symbols are extremely short, making it difficult to judge whether or not they constituted ...

and iconography. While the script has not been deciphered yet, many of the images on the tablets match another tablet and both hold the same caption in the Indus language, with the example given showing three tablets with the image of a mountain goat and the inscription on the back reading the same letters for the three tablets.

Pottery and terracotta sherd

In archaeology, a sherd, or more precisely, potsherd, is commonly a historic or prehistoric fragment of pottery, although the term is occasionally used to refer to fragments of stone and glass vessels, as well.

Occasionally, a piece of broken p ...

s have been recovered from the site, with many of the pots having deposits of ash in them, leading archeologists to believe they were either used to hold the ashes of a person or as a way to warm up a home located in the site. These heaters, or braziers, were ways to heat the house while also being able to be utilized in a manner of cooking or straining, while others solely believe they were used for heating.

The finds from Mohenjo-daro were initially deposited in the Lahore Museum

The Lahore Museum ( pa, ; ur, ; ''"Lahore Wonder House"'') is a museum located in Lahore, Pakistan. Founded in 1865 at a smaller location and opened in 1894 at its current location on The Mall, Lahore, The Mall in Lahore during the British Ra ...

, but later moved to the ASI headquarters at New Delhi, where a new "Central Imperial Museum" was being planned for the new capital of the British Raj, in which at least a selection would be displayed. It became apparent that Indian independence was approaching, but the Partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the Partition (politics), change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: ...

was not anticipated until late in the process. The new Pakistani authorities requested the return of the Harappan pieces excavated on their territory, but the Indian authorities refused. Eventually an agreement was reached, whereby the finds, totalling some 12,000 objects (most sherd

In archaeology, a sherd, or more precisely, potsherd, is commonly a historic or prehistoric fragment of pottery, although the term is occasionally used to refer to fragments of stone and glass vessels, as well.

Occasionally, a piece of broken p ...

s of pottery), were split equally between the countries; in some cases this was taken very literally, with some necklaces and girdles having their beads separated into two piles. In the case of the "two most celebrated sculpted figures", Pakistan asked for and received the ''Priest-king'', while India retained the much smaller ''Dancing Girl'', and also the '' Pashupati seal''.

Most of the objects from Mohenjo-daro retained by India are in the National Museum of India

The National Museum in New Delhi, also known as the National Museum of India, is one of the largest museums in India. Established in 1949, it holds a variety of articles ranging from pre-historic era to modern works of art. It functions under t ...

in New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament House ...

and those returned to Pakistan in the National Museum of Pakistan

The National Museum of Pakistan ( ur, ) is located in Karachi, Pakistan.

History

The National Museum of Pakistan was established in Frere Hall on 17 April 1950, replacing the defunct Victoria Museum. Frere Hall itself was built in 1865 as a t ...

in Karachi

Karachi (; ur, ; ; ) is the most populous city in Pakistan and 12th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 20 million. It is situated at the southern tip of the country along the Arabian Sea coast. It is the former cap ...

, with many also in the museum now established at Mohenjo-daro itself. In 1939, a small representative group of artefacts excavated at the site was transferred to the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

by the Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an Indian government agency that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural historical monuments in the country. It was founded in 1861 by Alexande ...

.

Mother Goddess Idol

Discovered byJohn Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

in 1931, the idol appears to mimic certain characteristics that match the Mother Goddess

A mother goddess is a goddess who represents a personified deification of motherhood, fertility goddess, fertility, creation, destruction, or the earth goddess who embodies the bounty of the earth or nature. When equated with the earth or th ...

belief common in many early Near East civilizations. Sculptures and figurines depicting women have been observed as part of Harappan culture and religion, as multiple female pieces were recovered from Marshall's archaeological digs. These figures were not categorized correctly, according to Marshall, meaning that where they were recovered from the site is not actually clear. One of said figures, pictured below, is 18.7 cm tall and is currently on display at the National Museum of Pakistan

The National Museum of Pakistan ( ur, ) is located in Karachi, Pakistan.

History

The National Museum of Pakistan was established in Frere Hall on 17 April 1950, replacing the defunct Victoria Museum. Frere Hall itself was built in 1865 as a t ...

, in Karachi. The fertility and motherhood aspects on display on the idols is represented by the female genitalia that is presented in an almost exaggerated style as stated by Marshall, with him inferring that such figurines are offerings to the goddess, as opposed to the typical understanding of them being idols representing the goddess's likeness. Because of the figurines being unique in terms of hairstyles, body proportions, as well as headdresses and jewelry, there are theories as to who these figurines actually represent. Shereen Ratnagar

Shereen F. Ratnagar is an Indian archaeologist whose work has focused on the Indus Valley civilization. She is the author of several books and academic textbooks.

Career

Ratnagar was educated at Deccan College, University of Pune. She studied ...

theorizes that because of their uniqueness and dispersed discovery throughout the site that they could be figurines of ordinary household women, who commissioned these pieces to be used in rituals or healing ceremonies to help aforementioned individual women.

Dancing Girl

A

A bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

statuette dubbed the "Dancing Girl", high and about 4,500 years old, was found in 'HR area' of Mohenjo-daro in 1926; it is now in the National Museum, New Delhi

The National Museum in New Delhi, also known as the National Museum of India, is one of the largest museums in India. Established in 1949, it holds a variety of articles ranging from pre-historic era to modern works of art. It functions under t ...

. In 1973, British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler

Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler CH CIE MC TD (10 September 1890 – 22 July 1976) was a British archaeologist and officer in the British Army. Over the course of his career, he served as Director of both the National Museum of Wales an ...

described the item as his favorite statuette:She's about fifteen years old I should think, not more, but she stands there with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on. A girl perfectly, for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There's nothing like her, I think, in the world.

John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

, another archeologist at Mohenjo-daro, described the figure as "a young girl, her hand on her hip in a half-impudent posture, and legs slightly forward as she beats time to the music with her legs and feet." The archaeologist Gregory Possehl Gregory Louis Possehl (July 21, 1941 – October 8, 2011) was a professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania and curator of the Asian Collections at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. H ...

said of the statuette, "We may not be certain that she was a dancer, but she was good at what she did and she knew it". The statue led to two important discoveries about the civilization: first, that they knew metal blending, casting and other sophisticated methods of working with ore, and secondly that entertainment, especially dance, was part of the culture.

Priest-King

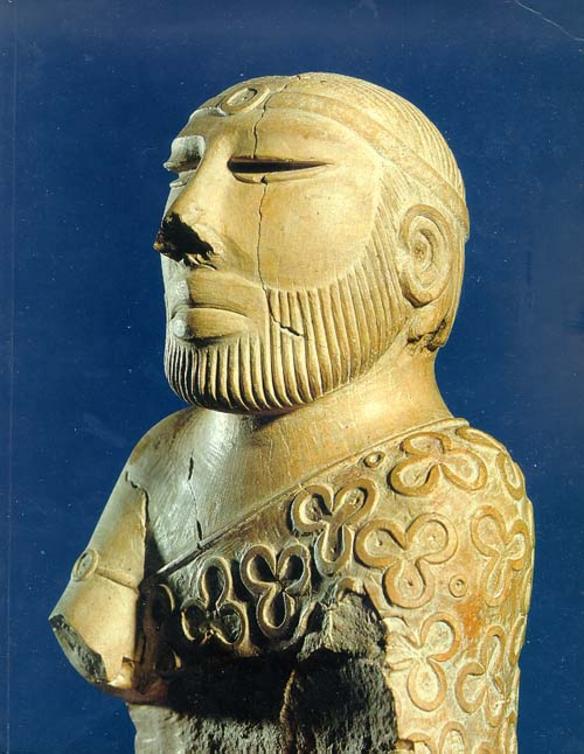

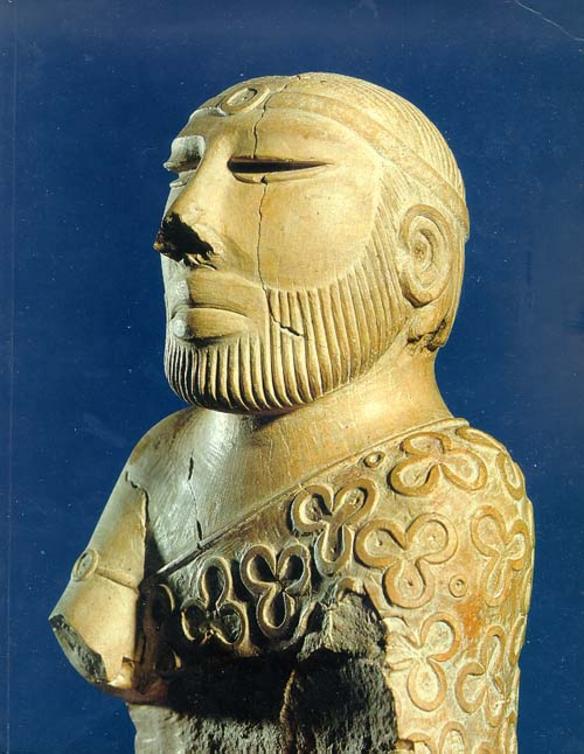

In 1927, a seated male

In 1927, a seated male soapstone

Soapstone (also known as steatite or soaprock) is a talc-schist, which is a type of metamorphic rock. It is composed largely of the magnesium rich mineral talc. It is produced by dynamothermal metamorphism and metasomatism, which occur in the zo ...

figure was found in a building with unusually ornamental brickwork and a wall-niche. Though there is no evidence that priests

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in p ...

or monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

s ruled Mohenjo-daro, archaeologists dubbed this dignified figure a "Priest-King". The sculpture is tall, and shows a neatly bearded man with pierced earlobes and a fillet

Fillet may refer to:

*Annulet (architecture), part of a column capital, also called a fillet

*Fillet (aircraft), a fairing smoothing the airflow at a joint between two components

*Fillet (clothing), a headband

*Fillet (cut), a piece of meat

*Fille ...

around his head, possibly all that is left of a once-elaborate hairstyle or head-dress; his hair is combed back. He wears an armband, and a cloak with drilled trefoil

A trefoil () is a graphic form composed of the outline of three overlapping rings, used in architecture and Christian symbolism, among other areas. The term is also applied to other symbols with a threefold shape. A similar shape with four rin ...

, single circle and double circle motifs, which show traces of red. His eyes might have originally been inlaid.

Pashupati seal

A seal discovered at the site bears the image of a seated, cross-legged and possiblyithyphallic

A phallus is a penis (especially when Erection, erect), an object that resembles a penis, or a mimesis, mimetic image of an erect penis. In art history a figure with an erect penis is described as ithyphallic.

Any object that symbolically— ...

figure surrounded by animals. The figure has been interpreted by some scholars as a yogi

A yogi is a practitioner of Yoga, including a sannyasin or practitioner of meditation in Indian religions.A. K. Banerjea (2014), ''Philosophy of Gorakhnath with Goraksha-Vacana-Sangraha'', Motilal Banarsidass, , pp. xxiii, 297-299, 331 Th ...

, and by others as a three-headed "proto-Shiva

Shiva (; sa, शिव, lit=The Auspicious One, Śiva ), also known as Mahadeva (; ɐɦaːd̪eːʋɐ, or Hara, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the Supreme Being in Shaivism, one of the major traditions within Hindu ...

" as "Lord of Animals".

Seven-stranded necklace

Sir Mortimer Wheeler was especially fascinated with this artifact, which he believed to be at least 4,500 years old. The necklace has an S-shaped clasp with seven strands, each over 4 ft long, of bronze-metal bead-like nuggets which connect each arm of the "S" infiligree

Filigree (also less commonly spelled ''filagree'', and formerly written ''filigrann'' or ''filigrene'') is a form of intricate metalwork used in jewellery and other small forms of metalwork.

In jewellery, it is usually of gold and silver, ma ...

. Each strand has between 220 and 230 of the many-faceted nuggets, and there are about 1,600 nuggets in total. The necklace weighs about 250 grams in total, and is presently held in a private collection in India.

Conservation and current state

An initial agreement to fund restoration was agreed through theUnited Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

(UNESCO) in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

on 27 May 1980. Contributions were made by a number of other countries to the project:

Preservation work for Mohenjo-daro was suspended in December 1996 after funding from the Pakistani government and international organizations stopped. Site conservation work resumed in April 1997, using funds made available by the UNESCO. The 20-year funding plan provided $10 million to protect the site and standing structures from

Preservation work for Mohenjo-daro was suspended in December 1996 after funding from the Pakistani government and international organizations stopped. Site conservation work resumed in April 1997, using funds made available by the UNESCO. The 20-year funding plan provided $10 million to protect the site and standing structures from flooding

A flood is an overflow of water ( or rarely other fluids) that submerges land that is usually dry. In the sense of "flowing water", the word may also be applied to the inflow of the tide. Floods are an area of study of the discipline hydrolog ...

. In 2011, responsibility for the preservation of the site was transferred to the government of Sindh.

Currently the site is threatened by groundwater salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal ...

and improper restoration. Many walls have already collapsed, while others are crumbling from the ground up. In 2012, Pakistani archaeologists warned that, without improved conservation measures, the site could disappear by 2030."Mohenjo Daro: Could this ancient city be lost forever?"BBC. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

2014 Sindh Festival

The Mohenjo-daro site was further threatened in January 2014, whenBilawal Bhutto Zardari

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari ( ur, بلاول بھٹو زرداری; born 21 September 1988) is a Pakistani politician who is serving as the 37th Minister of Foreign Affairs, in office since 27 April 2022. He became the chairman of Pakistan Peopl ...

of the Pakistan People's Party

The Pakistan People's Party ( ur, , ; PPP) is a centre-left, social-democratic political party in Pakistan. It is currently the third largest party in the National Assembly and second largest in the Senate of Pakistan. The party was founded i ...

chose the site for Sindh Festival's inauguration ceremony. This would have exposed the site to mechanical operations, including excavation and drilling. Farzand Masih, head of the Department of Archaeology at Punjab University warned that such activity was banned under the Antiquity Act

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

, saying "You cannot even hammer a nail at an archaeological site." On 31 January 2014, a case was filed in the Sindh High Court

The High Court of Sindh ( ur, ) is the highest judicial institution of the Pakistani province of Sindh. Established in 1906, the Court situated in the provincial capital at Karachi. Apart from being the highest Court of Appeal for Sindh in ...

to bar the Sindh government from continuing with the event. The festival was held by PPP at the historic site, despite all the protest by both national and international historians and educators.

Climate

Mohenjo-daro has ahot desert climate

The desert climate or arid climate (in the Köppen climate classification ''BWh'' and ''BWk''), is a dry climate sub-type in which there is a severe excess of evaporation over precipitation. The typically bald, rocky, or sandy surfaces in desert ...

(Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

''BWh'') with extremely hot summers and mild winters. The highest recorded temperature is , and the lowest recorded temperature is . Rainfall is low, and mainly occurs in the monsoon season (July–September). The average annual rainfall of Mohenjo-daro is 100.1 mm and mainly occurs in the monsoon season. The highest annual rainfall ever is 413.1 mm, recorded in 1994, and the lowest annual rainfall ever is 10 mm, recorded in 1987.

See also

*List of forts in Pakistan

The following is a partial list of forts and castles in Pakistan:

See also

* Tourism in Pakistan

* List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Pakistan

* List of museums in Pakistan

* Lahore Fort

* Rohtas Fort

* Noor Mahal

* Derawar Fort

Referen ...

* List of Indus Valley Civilization sites

Over 1400 Indus Valley civilisation sites have been discovered, of which 925 sites are in India and 475 sites in Pakistan, while some sites in Afghanistan are believed to be trading colonies. Only 40 sites on the Indus valley were discovere ...

* List of museums in Pakistan

This is a list of museums, galleries, and related building structures in Pakistan.

Museums and galleries

Archaeological and historical museums

* Harappa Museum, Harappa

* Baha ...

* List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Pakistan

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites are places of importance to cultural or natural heritage as described in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, established in 1972. Cultural heritag ...

* Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh (; ur, ) is a Neolithic archaeological site (dated ) situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan in Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, Ka ...

References

Bibliography

* Chaudhury, N. C.Mohenjo-Daro and the Civilization of Ancient India with References to Agriculture

'. Calcutta: W. Newman & Co, 1937. * Mackay, E. J. H., ed. (1937). ''Further Excavations At Mohenjo-daro: Being an official account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro carried out by the Government of India between the years 1927 and 1931''. *

Volume I

*

Volume II

* Marshall, John Hubert, ed. (1931). ''Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an official account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro carried out by the Government of India between the years 1922 and 1927''. Arthur Probsthain *

Volume I

*

Volume II

*

Volume III

* McIntosh, Jane (2008). ''The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives''. ABC-CLIO, 2008. *Singh, Kavita, "The Museum Is National", Chapter 4 in: Mathur, Saloni and Singh, Kavita (eds), ''No Touching, No Spitting, No Praying: The Museum in South Asia'', 2015, Routledge

PDF on academia.edu

(nb this is different to the article by the same author with the same title in ''India International Centre Quarterly'', vol. 29, no. 3/4, 2002, pp. 176–196

JSTOR

which does not mention this work)

External links

Official website of Mohenjodaro

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

103 Slide Tour and Essay on Mohenjo-daro by Dr. J.M. Kenoyer

{{Authority control History of Sindh Populated places established in the 3rd millennium BC Indus Valley civilisation sites World Heritage Sites in Pakistan Archaeological sites in Pakistan Bronze Age Asia Ancient history of Pakistan Larkana District Ruins in Pakistan Former populated places in Pakistan 1922 archaeological discoveries Tourist attractions in Sindh World Heritage Sites in Sindh 26th-century BC establishments 2nd-millennium BC disestablishments Lost cities and towns