Modern Greek dialects on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The linguistic varieties of Modern Greek can be classified along two principal dimensions. First, there is a long tradition of sociolectal variation between the natural, popular spoken language on the one hand and archaizing, learned written forms on the other. Second, there is regional variation between dialects. The competition between the popular and the learned registers (see Diglossia) culminated in the struggle between '' Dimotiki'' and '' Katharevousa'' during the 19th and 20th centuries. As for regional dialects, variation within the bulk of dialects of present-day Greece is not particularly strong, except for a number of outlying, highly divergent dialects spoken by isolated communities.

Tsakonian is a highly divergent variety, sometimes classified as a separate language because of not being intelligible to speakers of standard Greek. It is spoken in a small mountainous area slightly inland from the east coast of the

Tsakonian is a highly divergent variety, sometimes classified as a separate language because of not being intelligible to speakers of standard Greek. It is spoken in a small mountainous area slightly inland from the east coast of the

Pontic Greek varieties are those originally spoken along the eastern Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, the historical region of Pontus in Turkey. From there, speakers of Pontic migrated to other areas along the Black Sea coast, in Ukraine (see Mariupol), Russia and Georgia. Through the forced population exchange after the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) and the

Pontic Greek varieties are those originally spoken along the eastern Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, the historical region of Pontus in Turkey. From there, speakers of Pontic migrated to other areas along the Black Sea coast, in Ukraine (see Mariupol), Russia and Georgia. Through the forced population exchange after the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) and the

Griko or Italiot Greek refers to the Greek varieties spoken in some areas of southern Italy, a historical remnant of the ancient colonisation of

Griko or Italiot Greek refers to the Greek varieties spoken in some areas of southern Italy, a historical remnant of the ancient colonisation of

Diglossia

Roots and history: Demotic and Katharevousa

Ever since the times of Koiné Greek in Hellenistic and Roman antiquity, there was a competition between the naturally evolving spoken forms of Greek on the one hand, and the use of artificially archaic, learned registers on the other. The learned registers employed grammatical and lexical forms in imitation of classicalAttic Greek

Attic Greek is the Greek language, Greek dialect of the regions of ancient Greece, ancient region of Attica, including the ''polis'' of classical Athens, Athens. Often called classical Greek, it was the prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige diale ...

(Atticism

Atticism (meaning "favouring Attica", the region of Athens in Greece) was a rhetorical movement that began in the first quarter of the 1st century BC; it may also refer to the wordings and phrasings typical of this movement, in contrast with variou ...

).Horrocks, Geoffrey (1997): ''Greek: a history of the language and its speakers''. London: Longman. Ch. 5.5 This situation is known in modern linguistics as diglossia.

During the Middle Ages, Greek writing varied along a continuum between extreme forms of the high register very close to Attic, and moderate forms much closer to the spoken Demotic. According to Manolis Triantafyllides, the modern Greek language of the beginning of the 19th century, as used in the demotic poetry of the time, has very few grammatical differences from the vernacular language of the 15th century. During the early Modern Era, a middle-ground variety of moderately archaic written standard Greek emerged in the usage of educated Greeks (such as the Phanariots) and the Greek church; its syntax was essentially Modern Greek. After the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

and the formation of the modern Greek state (1830), a political effort was made to "purify" this form of Greek by bringing it back to resemble classical Attic Greek more closely. The result was Katharevousa (καθαρεύουσα, lit. 'the purifying one'), still a compromise form with basically Modern Greek syntax, but re-lexified with a much larger amount of Ancient Greek words and morphology. Katharevousa was used as an official language in administration, education, the church, journalism, and (until the late 19th century) in literature.

At the same time, spoken Demotic, while not recognised as an official language, nevertheless developed a supra-regional, de facto standard variety. From the late 19th century onwards, written Demotic rather than Katharevousa became the primary medium of literature. During much of the 20th century, there were heated political conflicts over the use of either of the two varieties, especially over the issue of their use in education. Schools were forced to switch from one form to the other and back several times during the 20th century. The conflict was resolved only after the overthrow of the Greek military junta of 1967-1974, whose strong ideological pro-Katharevousa stance had ultimately contributed to bringing that language form into disrepute. In 1976, shortly after the restoration of democracy, Demotic was finally adopted for use everywhere in education and became the language of the state for all official purposes. By that time, however, the form of Demotic used in practice was no longer the pure popular dialect, but had begun to assimilate elements from the Katharevousa tradition again. In 1982 diacritics were replaced by the ''monotonic orthography''.

Standard Modern Greek

Modern linguistics has come to call the resulting variety "Standard Modern Greek" to distinguish it from the pure original Demotic of earlier literature and traditional vernacular speech. Greek authors sometimes use the term "Modern Greek Koiné" ( el, Νεοελληνική Κοινή, Neoellinikí Koiní, lit=Common Modern Greek, link=no), reviving the term '' koiné'' that otherwise refers to the "common" form of post-classical Ancient Greek; according to these scholars, Modern Greek Koiné is the "supra-dialect

Supradialect (from Latin , "above", and Ancient Greek , "discourse") is a linguistic term designating a dialectological category between the levels of language and dialect. It is used in two distinctive contexts, describing structural or functiona ...

product of the composition of both the Demotic and Katharevousa." Indeed, Standard Modern Greek has incorporated a large amount of vocabulary from the learned tradition, especially through the registers of academic discourse, politics, technology and religion; together with these, it has incorporated a number of morphological features associated with their inflectional paradigms, as well as some phonological features not originally found in pure Demotic.

History of modern Greek dialects

The first systematic scholarly treatment of the modern Greek dialects took place after the middle of the 19th century, mainly thanks to the work of the prominent Greek linguist Georgios Hadjidakis. The absence of descriptive accounts of the speech of individual regions made the efforts of the researchers of the 19th century more difficult. Therefore, the dialects' forms are known to us only during their last phase (from the middle of the 19th century, and until the panhellenic dominance of the Standard Modern Greek).Initial dialect differentiation

Modern linguistics is not in accord with the tendency of the 19th century scholars to regard modern Greek dialects as the direct descendants of the dialects of ancient Greek. According to the latest findings of scholarship, modern Greek dialects are products of the dialect differentiation of Koiné Greek, and, with the exception of Tsakonian and possiblyItaliot Greek

The Italiotes ( grc-gre, Ἰταλιῶται, ') were the pre-Roman Greek-speaking inhabitants of the Italian Peninsula, between Naples and Sicily.

Greek colonization of the coastal areas of southern Italy and Sicily started in the 8th cent ...

, they have no correlation with the ancient dialects.

It is difficult to monitor the evolution of Koiné Greek and its splitting into the modern Greek dialects; certain researchers make the hypothesis that the various local varieties were formed between the 10th and the 12th century (as part of an evolution starting a few centuries before), but it is difficult to draw some safer conclusions because of the absence of texts written in the vernacular language, when this initial dialect differentiation occurred. Very few paradigms of these local varieties are found in certain texts, which however used mainly learned registers. The first texts written in modern Greek dialects appear during the Early Renaissance in the islands of Cyprus and Crete.

Historical literary dialects

Before the establishment of a common written standard of Demotic Greek, there were various approaches to using regional variants of Demotic as a written language. Dialect is recorded in areas outside Byzantine control, first in legal and administrative documents, and then in poetry. The earliest evidence for literary dialects comes from areas under Latin control, notably from Cyprus, Crete, and the Aegean islands. From Cyprus under the Lusignan dynasty (the 14th to 16th centuries), legal documents, prose chronicles, and a group of anonymous love poems have survived. Dialect archives also survive from 15th century Naxos. It is above all from the island of Crete, during the period of Venetian rule from 1204 until its capture by theOttomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

in 1669, that dialect can be illustrated more fully. Documents showing dialectal features exist from the end of the 12th century, rapidly increasing in number from the 13th century onward. During the Cretan Renaissance in the 16th and early 17th centuries there existed a flourishing vernacular literature in the Cretan dialect, based on Italian literary influences. Its best-known specimen today is the verse romance '' Erotokritos'', by Vitsentzos Kornaros (1553–1614).

Later, during the 18th and early 19th centuries, the Ionian Islands, then also under Italian rule, became a centre of literary production in Demotic Greek. The best-known writer from that period was the poet Dionysios Solomos (1789–1857), who wrote the Greek national anthem ''(Hymn to Liberty

The "Hymn to Liberty", or "Hymn to Freedom" ( el, Ὕμνος εἰς τὴν Ἐλευθερίαν, also ), is a poem written by Dionysios Solomos in 1823 that consists of 158 stanzas and is used as the national anthem of Greece and Cyprus. It ...

)'' and other works celebrating the Greek Revolution of 1821–1830. His language became influential on the further course of standardisation that led to the emergence of the modern standard form of Demotic, based on the south-western dialects.

Modern varieties

Spoken modern vernacular Greek can be divided into various geographical varieties. There are a small number of highly divergent, outlying varieties spoken by relatively isolated communities, and a broader range of mainstream dialects less divergent from each other and from Standard Modern Greek, which cover most of the linguistic area of present-day Greece and Cyprus. Native Greek scholarship traditionally distinguishes between " dialects" proper (διάλεκτος), i.e. strongly marked, distinctive varieties, and mere "idioms" (ιδίωμα), less markedly distinguished sub-varieties of a language. In this sense, the term "dialect" is often reserved to only the main outlying forms listed in the next section ( Tsakonian,Pontic

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from n ...

, Cappadocian and Italiot

The Italiotes ( grc-gre, Ἰταλιῶται, ') were the pre-Roman Greek-speaking inhabitants of the Italian Peninsula, between Naples and Sicily.

Greek colonization of the coastal areas of southern Italy and Sicily started in the 8th cent ...

), whereas the bulk of the mainstream spoken varieties of present-day Greece are classified as "idioms". However, most English-speaking linguists tend to refer to them as "dialects", emphasising degrees of variation only when necessary. The geographical varieties of Greek are divided into three main groups, Northern, Semi-Northern and Southern, based on whether they make synizesis and vowel elision

In linguistics, an elision or deletion is the omission of one or more sounds (such as a vowel, a consonant, or a whole syllable) in a word or phrase. However, these terms are also used to refer more narrowly to cases where two words are run toget ...

:

:Examples of Northern dialects are Rumelia

Rumelia ( ota, روم ايلى, Rum İli; tr, Rumeli; el, Ρωμυλία), etymologically "Land of the Names of the Greeks#Romans (Ῥωμαῖοι), Romans", at the time meaning Eastern Orthodox Christians and more specifically Christians f ...

n, Epirote

Epirus (; el, Ήπειρος, translit=Ípiros, ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region in northwestern Greece.Π.Δ. 51/87 “Καθορισμός των Περιφερειών της Χώρας για το σχεδι ...

(except Thesprotia prefecture), Thessalian, Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

n,Studies in Greek Syntax (1999), Pg 98–99 Thracian.

:The Southern category is divided into groups that include variety groups from:

:#Megara

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis Island, Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, befo ...

, Aegina, Athens, Kymi (Old Athenian) and Mani Peninsula

The Mani Peninsula ( el, Μάνη, Mánē), also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna (Μαΐνη), is a geographical and cultural region in Southern Greece that is home to the Maniots (Mανιάτες, ''Maniátes'' in Greek), who cla ...

(Maniot)

:#Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

(except Mani), Cyclades, Crete and Ionian Islands

:#Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

and Cyprus.

:#Part of Southern Albania (known as Northern Epirus among Greeks).

:#Asia Minor (Modern Turkey)

Outlying varieties

Tsakonian

Tsakonian is a highly divergent variety, sometimes classified as a separate language because of not being intelligible to speakers of standard Greek. It is spoken in a small mountainous area slightly inland from the east coast of the

Tsakonian is a highly divergent variety, sometimes classified as a separate language because of not being intelligible to speakers of standard Greek. It is spoken in a small mountainous area slightly inland from the east coast of the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

peninsula. It is unique among all other modern varieties in that it is thought to derive not from the ancient Attic

An attic (sometimes referred to as a '' loft'') is a space found directly below the pitched roof of a house or other building; an attic may also be called a ''sky parlor'' or a garret. Because attics fill the space between the ceiling of the ...

–Ionian

Ionic or Ionian may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Ionic meter, a poetic metre in ancient Greek and Latin poetry

* Ionian mode, a musical mode or a diatonic scale

Places and peoples

* Ionian, of or from Ionia, an ancient region in western ...

Koiné, but from Doric or from a mixed form of a late, ancient Laconian variety of the Koiné influenced by Doric. It used to be spoken earlier in a wider area of the Peloponnese, including Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia ( el, Λακωνία, , ) is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word ''laconic''—to speak in a blunt, c ...

, the historical home of the Doric Spartans.

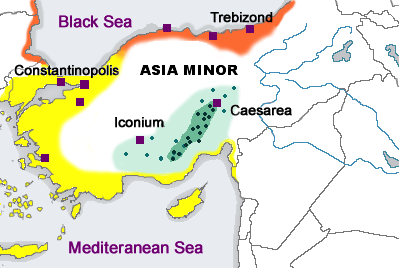

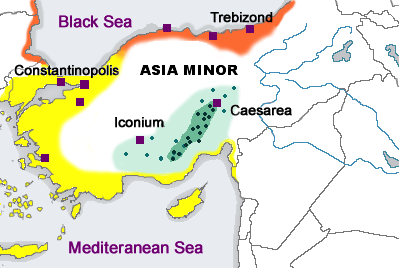

Pontic Greek

Pontic Greek varieties are those originally spoken along the eastern Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, the historical region of Pontus in Turkey. From there, speakers of Pontic migrated to other areas along the Black Sea coast, in Ukraine (see Mariupol), Russia and Georgia. Through the forced population exchange after the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) and the

Pontic Greek varieties are those originally spoken along the eastern Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, the historical region of Pontus in Turkey. From there, speakers of Pontic migrated to other areas along the Black Sea coast, in Ukraine (see Mariupol), Russia and Georgia. Through the forced population exchange after the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) and the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

of 1923, the Pontic speakers of Turkey were expelled and moved to Greece. Of the Pontic speakers in the ex-Soviet Union, many have immigrated to Greece more recently. The number of Pontic Greeks currently maintaining the dialect is unclear. A small group of Muslim Pontic speakers remain in Turkey, although their varieties show heavy structural convergence towards Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

.

Cappadocian Greek

Other varieties of Anatolian Greek that were influenced by the Turkish language, besides Pontic, are now almost extinct, but were widely spoken until 1923 in central Turkey, and especially in Cappadocia. In 1923, all Orthodox Christian inhabitants of Asia Minor were forced to emigrate to Greece after the Greek genocide (1919–1921) during the Population exchange between Greece and Turkey. In 2005, professors Mark Janse and Dimitris Papazachariou discovered that there are still native speakers of the Mistiot dialect of Cappadocian in Central and Northern Greece. Cappadocian Greek diverged from the other Byzantine Greek varieties earlier, beginning with the Turkish conquests of central Anatolia in the 11th and 12th centuries, and so developed several radical features, such as the loss of the gender for nouns. Having been isolated from the crusader conquests (Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

) and the later Venetian influence of the Greek coast, it retained the Ancient Greek terms for many words that were replaced with Romance ones in Demotic Greek. The poet Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

, whose name means "Roman", referring to his residence amongst the "Roman" Greek speakers of Cappadocia, wrote a few poems in Cappadocian Greek, leaving one of the earliest attestations of the dialect.

Pharasiot Greek

The Greek dialect spoken in Pharasa (Faraşa, now Çamlıca village inYahyalı

Yahyalı is a town and the southernmost district of Kayseri province in Turkey. The Aladağlar Mountains, a part of the rocky Taurus Mountains, pass through this region as does the River Zamantı.

Mostly covered in forest, the Aladağlar Nation ...

, Kayseri

Kayseri (; el, Καισάρεια) is a large Industrialisation, industrialised List of cities in Turkey, city in Central Anatolia, Turkey, and the capital of Kayseri Province, Kayseri province. The Kayseri Metropolitan Municipality area is comp ...

) and other nearby villages (Afshar-Köy, Çukuri), to the east of Cappadocia, is not particularly close to Cappadocian. It may be closer to Pontic, or equally distant from both. The Pharasiot priest Theodoridis published some folk texts. In 2018, Metin Bağrıaçık published a thesis on Pharasiot Greek, based on speakers remaining in Greece.

Silliot Greek

The Greek dialect of Sille (nearIconium

Konya () is a major city in central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of Konya Province. During antiquity and into Seljuk times it was known as Iconium (), although the Seljuks also called it D ...

/Konya) was the most divergent of the varieties of Asia Minor Greek.

Italiot Greek

Griko or Italiot Greek refers to the Greek varieties spoken in some areas of southern Italy, a historical remnant of the ancient colonisation of

Griko or Italiot Greek refers to the Greek varieties spoken in some areas of southern Italy, a historical remnant of the ancient colonisation of Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia (, ; , , grc, Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς, ', it, Magna Grecia) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily; these re ...

. There are two small Griko-speaking communities known as the Griko people who live in the Italian regions of Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, the southern tip of the Italian peninsula, and in Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

, its south-easternmost corner. These varieties too are believed to have developed on the basis of an originally Doric ancient dialect, and have preserved some elements of it, though to a lesser extent than Tsakonian. They subsequently adopted influences from ancient Koiné, but became isolated from the rest of the Greek-speaking world after the decline of Byzantine rule in Italy during the Middle Ages. Among their linguistic peculiarities, besides influences from Italian, is the preservation of the infinitive, which was lost in the modern Greek of the Balkans.

Mariupolitan

Rumeíka (Ρωμαίικα) or Mariupolitan Greek is a dialect spoken in about 17 villages around the northern coast of theSea of Azov

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

in southern Ukraine. Mariupolitan Greek is closely related to Pontic Greek and evolved from the dialect of Greek spoken in the Crimea, which was a part of the Pontic Empire of Trebizond

The Empire of Trebizond, or Trapezuntine Empire, was a monarchy and one of three successor rump states of the Byzantine Empire, along with the Despotate of the Morea and the Principality of Theodoro, that flourished during the 13th through to t ...

until that state fell to the Ottomans in 1461. Thereafter the Crimean region remained independent and continued to exist as the Greek Principality of Theodoro. The Greek speaking residents of the Crimea were invited by Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

to resettle in, and found, the new city of Mariupol after the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) to escape the then Muslim dominated Crimea. Its main features present certain similarities with both the Pontic (e.g. the lack of synizesis of ''-ía, éa''), and the northern varieties of the core dialects (e.g. the northern vocalism).

Istanbul Greek

Istanbul Greek is a dialect of Greek spoken in Istanbul, as well as by the Istanbul Greek emigre community in Athens. It is characterized by a high frequency of loanwords and grammatical structures imported from other languages, the main influences being Turkish, French, Italian and Armenian, while also preserving some archaic characteristics lost in other dialects. Speakers are noted for their production of dark L andpostalveolar affricate Postalveolar affricates are a type of consonant sound. The most common postalveolar affricates are:

*Voiced postalveolar affricate ()

*Voiceless postalveolar affricate

The voiceless palato-alveolar sibilant affricate or voiceless domed postalveol ...

s.

Other outlying varieties

In Asia Minor, Greek varieties existed not only in the broader area of Cappadocia, but also in the western coast. The most characteristic is the dialect of Smyrna which had a number of distinguishing features, such as certain differences in the accusative andgenitive

In grammar, the genitive case (abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can al ...

cases of the definite article; the Greek speakers of the area had also incorporated into their dialect many French words. Constantinopolitan Greek, on the other side, has very few dialectal features, and it is very close to what scholars call "Modern Greek Koiné."

Another Greek outlying dialect was spoken, until the mid-20th century, in Cargèse on Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, by descendants of 17th-century settlers from the Mani peninsula

The Mani Peninsula ( el, Μάνη, Mánē), also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna (Μαΐνη), is a geographical and cultural region in Southern Greece that is home to the Maniots (Mανιάτες, ''Maniátes'' in Greek), who cla ...

. The dialect, which is now regarded as extinct, had preserved the main characteristics of the Mani dialect, and had been also influenced by both the Corsican and the French language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Nor ...

(official language of the island after its union with France).

Core dialects

Unlike the above, the varieties described below form a contiguous Greek-speaking area, which covers most of the territory of Greece. They represent the vast majority of Greek speakers today. As they are less divergent from each other and from the standard, they are typically classified as mere "idioms" rather than "dialects" by Greek authors, in the native Greek terminology. The most prominent contrasts between the present-day dialects are found between northern and southern varieties. Northern varieties cover most of continental Greece down to theGulf of Corinth

The Gulf of Corinth or the Corinthian Gulf ( el, Κορινθιακός Kόλπος, ''Korinthiakόs Kόlpos'', ) is a deep inlet of the Ionian Sea, separating the Peloponnese from western mainland Greece. It is bounded in the east by the Isth ...

, while the southern varieties are spoken in the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

peninsula and the larger part of the Aegean and Ionian islands, including the large southern islands of Crete and Cyprus. The most salient defining marker of the northern varieties is their treatment of unstressed vowels (so-called ''northern vocalism''), while many southern varieties are characterised, among other things, by their palatalisation of velar consonants. Between these areas, in a contiguous area around the capital Athens (i.e. the regions of Attica and neighbouring parts of Boeotia, Euboia, the Peloponnese and nearby islands), there is a "dialectal void" where no distinctly marked traditional Greek dialects are found. This is due to the fact that these areas were once predominantly inhabited by speakers of Arvanitika Albanian. The Greek spoken in this area today is the product of convergence between varieties of migrants who moved to the capital and its surroundings from various other parts of the country, and it is close to the standard. On the whole, Standard Modern Greek is based predominantly on the southern dialects, especially those of the Peloponnese.

At the fringes of this former Arvanitika-speaking area, there were once some enclaves of highly distinct traditional Greek dialects, believed to have been remnants of a formerly contiguous Greek dialect area from the time before the Arvanitic settlement. These include the old local dialect of Athens itself ("Old Athenian"), that of Megara

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis Island, Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, befo ...

(to the west of Attica), of Kymi in Euboia and of the island of Aegina. These dialects are now extinct.

The following linguistic markers have been used to distinguish and classify the dialects of Greece. Many of these features are today characteristic only of the traditional rural vernaculars and may be socially stigmatised. Younger, urban speakers throughout the country tend to converge towards accents closer to the standard language, with Cyprus being an exception to this.

Phonological features

*Northern vocalism (high vowel loss). In the north, unstressedhigh vowel

A close vowel, also known as a high vowel (in U.S. terminology), is any in a class of vowel sounds used in many spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a close vowel is that the tongue is positioned as close as possible to the roof of th ...

s ( and ) are typically deleted (e.g. vs. standard ) 'dust'). Unstressed mid vowel

A mid vowel (or a true-mid vowel) is any in a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a mid vowel is that the tongue is positioned midway between an open vowel and a close vowel.

Other names for a mid ...

s ( and ) are raised to and instead (e.g. vs. standard 'child'). Subtypes of this phenomenon can be distinguished as follows: in "Extreme Northern" dialects these two processes apply throughout. In mid "Northern" dialects the deletion of and applies only to word-final vowels. "Semi-Northern" dialects only have the deletion of word-final and , but not the raising of and . The latter include Mykonos, Skiros, Lefkada and the urban dialect of the Greeks of Constantinople.

*Palatalisation. Standard Greek has an allophonic alternation between velar consonants (, , , ) and palatalised counterparts ((, , , ) before front vowel

A front vowel is a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages, its defining characteristic being that the highest point of the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would otherw ...

s (, ). In southern dialects, the palatalisation goes further towards affricate

An affricate is a consonant that begins as a stop and releases as a fricative, generally with the same place of articulation (most often coronal). It is often difficult to decide if a stop and fricative form a single phoneme or a consonant pair. ...

s (e.g. vs. standard 'and'). Subtypes can be distinguished that have either palato-alveolar (, , , ) or alveolo-palatal sounds (, , , ). The former are reported for Cyprus, the latter for Crete, among others.Trudgill 2003: 54.

*Tsitakism. In a core area in which the palatalisation process has gone even further, covering mainly the Cycladic Islands, palatalised is further fronted to alveolar Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* ...

and thus merges with the original phoneme . This phenomenon is known in Greek as ''tsitakism'' (τσιτακισμός). It was also shared by Old Athenian.

*Ypsilon. A highly archaic feature shared by Tsakonian, the Maniot dialect, and the Old Athenian enclave dialects, is the divergent treatment of historical (<υ>). While this sound merged to everywhere else, these dialects have instead (e.g. vs. standard 'wood').

*Geminate consonants. Most Modern Greek varieties have lost the distinctively long ( geminate) consonants found in Ancient Greek. However, the dialects of the south-eastern islands, including Cyprus, have preserved them, and even extended them to new environments such as word-initial positions. Thus, the word <ναι> 'yes' is pronounced with a distinctively long initial in Cypriot, and there are minimal pairs such as <φύλλο> 'leaf' vs. <φύλο> 'gender', which are pronounced exactly the same in other dialects but distinguished by consonant length in Cypriot.Trudgill 2003: 57.

*Dark . A distinctive marker of modern northern vernaculars, especially of Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

, is the use of a " dark" (velarised

Velarization is a secondary articulation of consonants by which the back of the tongue is raised toward the velum during the articulation of the consonant.

In the International Phonetic Alphabet, velarization is transcribed by one of four diac ...

) sound.

*Medial fricative deletion. Some dialects of the Aegean Islands, especially in the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

, have a tendency of deleting intervocalic voiced fricatives , , (e.g. vs. standard 'big').

*Nasals and voiced plosives. Dialects differ in their phonetic treatment of the result of the assimilation of voiceless plosive

In phonetics, a plosive, also known as an occlusive or simply a stop, is a pulmonic consonant in which the vocal tract is blocked so that all airflow ceases.

The occlusion may be made with the tongue tip or blade (, ), tongue body (, ), lips ...

s with preceding nasal

Nasal is an adjective referring to the nose, part of human or animal anatomy. It may also be shorthand for the following uses in combination:

* With reference to the human nose:

** Nasal administration, a method of pharmaceutical drug delivery

** ...

s. All dialects have a voicing of the plosive in this position, but while some dialects also have an audible segment of prenasalisation, others do not; thus <πομπός> (pompós) 'transmitter' may be realised as either or . Furthermore, prenasalisation tends to be preserved in more formal registers regardless of geography. In informal speech, it tends to be more common in northern varieties.

*Lack of synizesis of ''-ía, éa'' > . Standard Greek and most dialects have a pattern whereby Ancient Greek or immediately before an accented (later stressed) vowel have turned into a non-syllabic glide , for instance in <παιδιά> 'children', from Ancient Greek <παιδία> . In some dialects this process has not taken place or has done so only partially. These dialects display either full preservation of , or a schwa

In linguistics, specifically phonetics and phonology, schwa (, rarely or ; sometimes spelled shwa) is a vowel sound denoted by the IPA symbol , placed in the central position of the vowel chart. In English and some other languages, it rep ...

sound , leading to forms such as <φωλέα> 'nest' and <παιδία> 'children'. The phenomenon is common in Griko and Pontic. It is also reported in Mani and Kythira. On the other hand, in some dialects that have , the glide gets further reduced and deleted after a preceding sibilant

Sibilants are fricative consonants of higher amplitude and pitch, made by directing a stream of air with the tongue towards the teeth. Examples of sibilants are the consonants at the beginning of the English words ''sip'', ''zip'', ''ship'', and ...

(), leading to forms like <νησά> 'islands' instead of standard <νησιά> (de-palatalisation of sibilants).

Grammatical features

*Final . Most Modern Greek varieties have lost word-final ''-n'', once a part of many inflectionalsuffix

In linguistics, a suffix is an affix which is placed after the stem of a word. Common examples are case endings, which indicate the grammatical case of nouns, adjectives, and verb endings, which form the conjugation of verbs. Suffixes can carry ...

es of Ancient Greek, in all but very few grammatical words. The south-eastern islands have preserved it in many words (e.g. vs. standard ''he said''; vs. standard 'cheese').

*'inda?'' versus ''ti?' In Standard Greek, the interrogative pronoun ''what?'' is ''ti''. In most of the Aegean Islands (except at its geographical fringe: Rhodes in the south-east, Lemnos, Thasos and the Sporades in the north; and Andros in the west) as well as on Cyprus, it is ''inda''.Kontosopoulos 1999.

*Indirect objects. All Modern Greek dialects have lost the dative

In grammar, the dative case (abbreviated , or sometimes when it is a core argument) is a grammatical case used in some languages to indicate the recipient or beneficiary of an action, as in "Maria Jacobo potum dedit", Latin for "Maria gave Jacob a ...

case. In some dialects, this has resulted in a merger between the dative and the genitive, whereas in others there has been a merger between the dative and the accusative. In the standard and in the southern dialects, the personal pronoun forms used to express indirect objects are those of the genitive case, as in example 1 below. In northern dialects, like Macedonian; mainly in Thessaloniki, Constantinople, Rhodes, and in Mesa Mani, the accusative forms are used instead, as in example 2. In plural, only the accusative forms are used both in southern and northern dialects.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Varieties Of Modern Greek Greek language